Sioshansi F.P. Smart Grid: Integrating Renewable, Distributed & Efficient Energy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Moreover, the increasing capabilities of building energy

systems will make continuous commissioning more feasible

for residential consumers as well as large commercial and

industrial ones. Smart homes and buildings will be able to

monitor equipment performance, optimize comfort and

efficiency, and convey environmental performance [21]. They

will be able to target opportunities for efficiency with

stunning accuracy [22]. In the smart grid, energy efficiency

will become intrinsic to how we operate our buildings and

live our lives.

Operational Efficiency

Modernizing equipment and automating operations can

significantly improve performance, reduce losses, and reduce

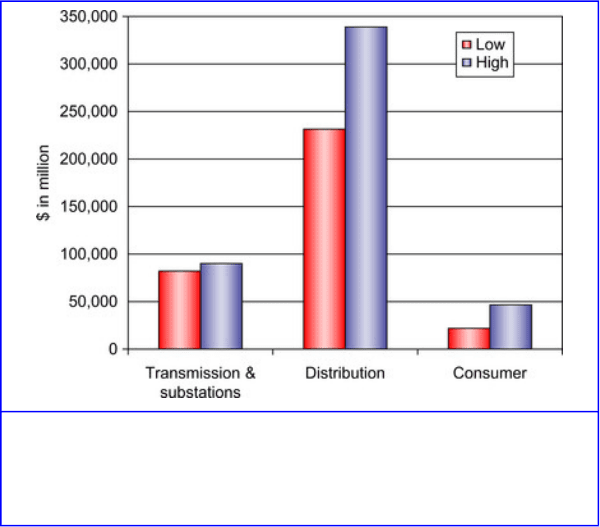

the cost of operating the grid. A recent EPRI report [23]

indicates that most of the cost and benefits of the smart grid

will occur in the distribution network (Figure 1.5). While

most utilities have automated their business processes, many

have not automated their field operations. The oft-repeated

anecdote is that utilities know when the power is out at some

locations—especially at the end of radial lines—when

consumers call and tell them. They then often diagnose the

problem by dispatching crews to drive the distribution lines

with paper maps in hand until they spot the problem. At the

transmission level, of course, operators may have

sophisticated sensors, software, and controls at their disposal.

Nevertheless, there are significant opportunities for

improvement throughout the grid.

121

Figure 1.5

Total smart grid costs.

Source: EPRI, 2011

New technologies and systems are needed to implement

proactive maintenance and repairs, reducing failures and

increasing the life of aging equipment. Significant energy

savings are possible through techniques such as voltage

optimization [24] and dynamic line rating. Many utilities have

begun to address this issue by installing sensors,

communications, and controls at critical points in their

system. Simply knowing the status of various devices in the

field in near-real time can enhance the ability of operators to

optimize power flow and quality. Digital meters equipped

with the ability to communicate at each account location can

reduce the cost of reading the meters, automatically report

local outages, allow operators to remotely connect and

disconnect accounts, reduce theft, monitor voltage levels, and

122

provide many other benefits. More progressive utilities have

installed automated systems with dynamic digital maps and

sophisticated management tools. These features not only

improve the efficiency of utility operations, but also open up

new levels of service and can make working conditions safer

for field workers.

Given their different starting points and driving motivations,

the full benefit of automating operations will vary

substantially from utility to utility, with highly customized

applications for each. Some, for example, may emphasize

automatic fault detection because of the high cost of repairing

complex underground systems. Others may emphasize

automatic switching to reduce the duration of an outage to

remotely located consumers. Eventually, the smart grid may

provide ancillary services like frequency regulation by

automatically adjusting demand with storage devices or by

varying certain loads. In this vein, the Pacific Northwest

National Laboratory, through its parent laboratory manager,

recently licensed a frequency sensor/controller chip that can

be installed inexpensively in various appliances and used to

adjust loads in real time, thereby moderating frequency

exertions on the grid automatically with little or no central

control [25].

While full and complete grid automation is a noble goal, in

isolation it is neither mission critical nor will it likely be cost

effective. In designing and building the smart grid, it will be

important not only to optimize performance but also to

optimize the cost of operating the grid.

123

Demand Management

When consumers decide to buy more computers, heaters, air

conditioners, or more and larger televisions, they expect their

electric utility to make sure that electricity is available to

power the devices. This is true whether it's the hottest day of

summer or in the middle of a winter storm. Consumers do not

perceive the grid-related consequences or costs of their

decisions. As further described in Chapter 2 by Healy and

MacGill, the industry essentially disengaged the consumers

from the activities up-stream of the meter.

The easiest way to please the most consumers in the past has

been to build the system big enough and robust enough to

meet all of their needs, especially at times of peak

consumption. According to the Edison Electric Institute, in

2008 U.S. consumers used 4,110,259,000,000 kWh [26], just

over 4 trillion kWh, of electricity [27] (Figure 1.6). That's

nearly 14 MWh per person per annum, much above the global

average. For more than 100 years, we've built an

infrastructure to serve essentially any amount of electricity

that consumers request. We ask utilities to estimate the future

consumer demand for electricity and build the production and

delivery infrastructure—power plants, regional transmission

systems, and local distribution systems—to accommodate this

growth. And since we cannot store electricity—at least not

much—production has to match consumer demand at any

instant. Moreover, we ask utilities to build the system

10–20% larger than the anticipated demand to make sure we

can accommodate unexpected growth or loss of critical

generation or transmission lines [28].

124

Figure 1.6

U.S. Electricity Flow, 2009 (Quads).

EIA Website

In North America, the Federal Energy Regulatory

Commission (FERC) and the North American Electric

Reliability Corporation (NERC) and its affiliated regional

reliability groups oversee system plans and operations to

ensure that the lights stay on. Among many other things, they

track trends in electricity use and ensure that the industry is

properly planning for and building the power production and

transmission capacity that are needed to meet demand. In

2009, NERC predicted that production capacity for electricity

in the United States will grow from just over 1,000,000 MW,

or 1 Billion kW, in 2009 to just over 1,400,000 MW in 2018,

a 40% increase in nine years [29].

NERC also projects the corresponding consumed energy to

grow from just over 4 TWh at present to just over 4.5 TWh in

2018—a total increase of about 15%. There are at least two

reasons why production capacity is expected to grow more

than twice as fast as electricity demand.

• The first is that more than 50% of the expected capacity

increase is attributed to wind power, the availability of

which is rarely coincident with peak demand (typically less

than 25% of the time), whereas baseload plants—generally

coal-fired or nuclear—are typically available during peak

demand.

125

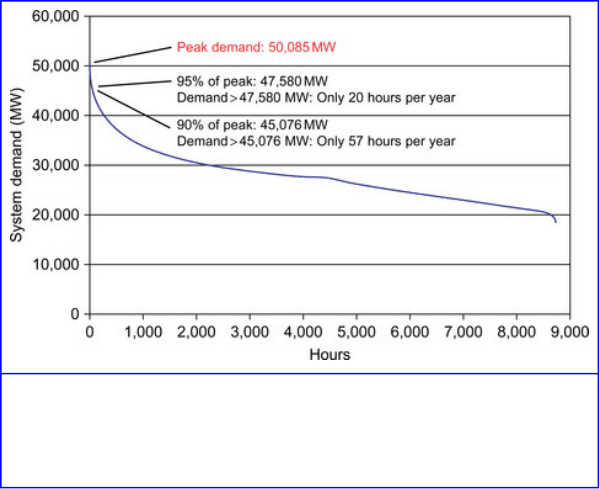

• The second reason is that, since the 1960s, our electricity

use has been increasingly weather-dependent and peaky.

Businesses tend to use more electricity in the mid-to-late

afternoon, while residences use more electricity in

mornings and evenings [30]. More than 10% of our total

national production capacity is required less than 100 hours

each year (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7

Typical demand response potential in CA.

Source: Data derived from California ISO (CAISO)

The net result is that in many regions, peak demand is

growing much faster than average demand, a trend that is

unhelpful if costs are to be kept low and plant factors high.

Similar trends are experienced globally. This explains why

reducing consumer electricity use during peak

times—commonly referred to as demand response—has

become a high priority.

126

There are varied technologies and programs that can make

demand response relatively easy and cost effective for

consumers. In 2009, FERC assessed current demand response

programs state-by-state to project the improvements that are

possible nationally [31]. The report identified a range of

possible options that could reduce overall peak demand 4%,

or roughly 38 GW, to as much as 20%, or roughly 188 GW,

over time, as further described in the book's Introduction. The

latter figure would require that utilities be much more

aggressive in seeking improvement in load factor and that

consumers be induced to participate more widely in various

demand response programs. In 2010, FERC issued a

companion report that lays out a national plan for making

demand response a priority [32]. Most recently, in March

2011 FERC released Order 745, which establishes rules by

which demand response resources should be paid for

participating in organized wholesale markets. While industry

reaction to FERC's initiative is mixed at best, the ensuing

debate will no doubt clarify many remaining questions about

the true benefits of demand response [33].

In the smart grid, the exact amount of demand response is less

important than the concept of creating a grid that allows the

electricity system to reduce loads readily, when necessary,

diverting electricity from noncritical to more critical and

essential loads. This must be done both automatically—such

as lights dimming in warehouses during peaks or refrigerator

temperatures or thermostats shifting a few degrees—and with

substantially enhanced consumer participation. Such elegant

energy management systems might involve consumers setting

their preferences and varying them when prices or conditions

change.

2

New technologies and systems might provide ways

to induce demand to follow changes in production—and

127

production costs—instead of production responding to

changes in load.

3

This approach should logically incorporate

dynamic rates so that consumer behavior is linked to the cost

of delivering energy at any particular time.

4

One of the

important benefits of this change to the grid would be the

potential to sharply reduce the reserve margin requirements

for utilities and grid operators. This requirement, absolutely

critical in our current grid system, could eventually become

obsolete, with huge savings in capital investments that are

reduced or rendered unnecessary.

2

Harper-Slaboszewica et al. in Chapter 15 titled “Set and Forget” describe

relatively convenient ways for consumers to become active participants

in balancing supply and demand.

3

Chapter 10 by Hanser et al. describes the role of load as a means of

balancing supply and demand as opposed to the traditional method of

relying entirely on adjustments on the supply side.

4

Chapter 3 by Faruqui describes the role of dynamic pricing in the future

smart grid.

We Would Want the Smart Grid to Be Clean

In spite of the growing political and societal concern about

climate change, renewable energy in the United States until

now has been a small contributor to power production,

approaching just 4% of the total generation in 2008,

excluding hydropower. There are many reasons for this:

historically high costs for renewable energy, inconsistent

federal and state incentives, and a lack of consumer

acceptance. For various reasons, this is now changing. Even

without clear federal mandates, dozens of states and cities

128

have made carbon-reduction commitments that continue to

drive markets and more will likely follow suit. Renewable

energy and clean tech companies are at last able to forecast

both stability and growth in long-term markets for their

products and services. New technologies, new companies, and

new business models are emerging.

While the expectations for national or global commitments to

carbon reduction targets are not currently encouraging, other

factors, such as the prospect for more stringent regulations,

such as those proposed by the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA), will continue to put pressure on the industry

to switch to a cleaner generation mix. Figure 1.8 shows the

forecasted growth in renewable energy from the EIA (Energy

Outlook 2011). On January 29, 2010, President Obama issued

an executive order mandating certain reductions in carbon

emissions by federal facilities—a 28% reduction over 2005

levels by 2020 [34]. Even without clear federal mandates,

dozens of jurisdictions have made commitments that continue

to drive markets [35]. Almost no matter what the final

specific targets are and what form national and international

policy takes, it is clear that the smart grid must accommodate

the integration of massive amounts of carbon-free production

technologies.

5

5

The chapter by Lilley et al. (Chapter 7), for example, examines the

implications of a global push towards a cleaner energy mix in the electric

power sector and its projected benefits.

129

Figure 1.8

Projections of renewable energy generation capacity in the United States,

2009–2035 (GW).

Source: Annual Energy Outlook 2011, EIA, Reference Case

Renewable Resources

While the amount of solar generation in the United States

more than tripled between 2000 and 2008 [36], it still

represents only a fraction of 1% of the total U.S. generation.

Specific utilities have recently launched projects to explore

the impact of high-penetration renewable scenarios by

installing 30% or more solar PV in a particular neighborhood

and assessing the grid impacts. These projects are an attempt

to anticipate the market impact of very inexpensive solar

equipment: while predictions on the future cost of PV systems

are difficult, there is general agreement that costs will

130