Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 105

■

Allowing for future dividend growth

Dividends fluctuate over time, largely because of variations in the company’s fortunes,

although most firms attempt to grow dividends more or less in line with the company’s

longer-term earnings growth rate. For reasons explained in Chapter 17, financial man-

agers attempt to ‘smooth’ the stream of dividends. For companies operating in mature

industries, the growth rate will roughly correspond to the underlying growth rate of the

whole economy. For companies operating in activities with attractive growth opportu-

nities, dividends are likely to grow at a faster rate, at least over the medium term.

■ Allowing for dividend growth: the DGM

The constant dividend valuation model can be extended to cover constant growth thus

becoming the Dividend Growth Model (DGM). This states that the value of a share is

the sum of all discounted dividends, growing at the annual rate g:

If D

o

is this year’s recently paid dividend,* D

o

(1g) is the dividend to be paid in one

year’s time (D

1

), and so on.

Such a series growing to infinity has a present value of:

The growth version of the model is often used in practice by security analysts (it is

popularly known as ‘the dividend discount model’), at least as a reference point, but

it makes some key assumptions. Dividend growth is assumed to result from earnings

growth, generated solely by new investment financed by retained earnings. Such

investment is, of course, worthwhile only if the anticipated rate of return, R, is in

excess of the cost of equity, k

e

. Furthermore, it is assumed that the company will retain

a constant fraction of earnings and invest these in a continuous stream of projects all

offering a return of R. It also breaks down if g exceeds k

e

. (Problems with the DGM are

discussed in Section 4.10.)

■ Navenby again

To illustrate the growth model, we return to the Navenby example but assume an infi-

nite project life. This requires removal of the asset sale at the end of year 5. Suppose fur-

ther that, at the end of the first year, it will retain 50 per cent of its earnings and reinvest

these at an expected annual return of 20 per cent, comfortably above the required 12 per

cent. In the next year, earnings would grow at 10 per cent to reach a new level of:

‘original’ cash flow return on reinvested earnings =

new earnings level of £0.1 m 20% (50% £0.1 m) (£0.1 m £0.01 m) £0.11 m

If further retentions of 50 per cent are made at the end of the second year and also

reinvested in further projects offering annual returns of 20 per cent, earnings after

three years will be:

£0.11 m 20% of (50% £0.11 m) (£0.11 m £0.011 m) £0.121 m

and so on. The policy of retention and reinvestment has launched Navenby on an

P

o

D

o

11 g2

1k

e

g2

D

1

1k

e

g2

P

o

D

o

11 g2

11 k

e

2

D

o

11 g2

2

11 k

e

2

2

D

o

11 g2

3

11 k

e

2

3

p

D

o

11 g2

n

11 k

e

2

n

*If the dividend has recently been paid, i.e. the next dividend will be paid in, say, a year’s time, the shares

are said to be ‘ex-dividend’. They trade without entitlement to a dividend for some considerable time.

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 105

.

106 Part I A framework for financial decisions

exponential growth path. The dividend growth rate of 10 per cent is a compound of

the retention ratio, denoted by b, and the return on reinvested earnings, R:

g = (b R) = (50% 20%) = 10%

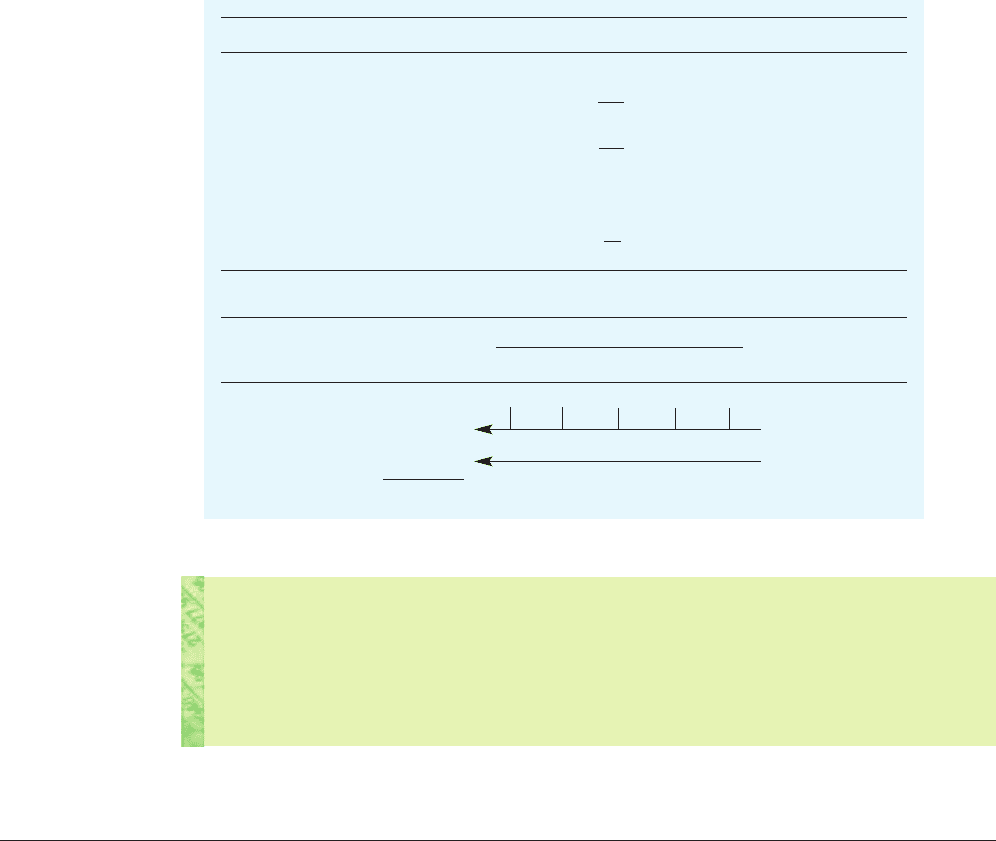

Table 4.3 shows the future behaviour of both earnings and dividends assuming b

and R are constant. Clearly, both magnitudes grow in tandem, so long as the compa-

ny maintains the same retention ratio (50 per cent).

In Chapter 17, we examine more fully the issues of whether and how a change in

dividend policy can be expected to alter share value. For the moment, we are mainly

concerned with the mechanics of the DGM and rely simply on the assumption that any

retained earnings are used for worthwhile investment. If this applies, the value of the

equity will be higher with retentions-plus-reinvestment than if the investment oppor-

tunities were neglected, i.e. the decision to retain earnings benefits shareholders

because of company access to projects that offer returns higher than the owners could

otherwise obtain.

Table 4.3

How earnings and divi-

dends grow in tandem

(figures in £m)

Year

1 2 3 4 etc.

Earnings 0.10 0.11 0.121 0.1331 etc.

Dividends (50%) 0.05 0.055 0.0605 0.06655 etc.

Self-assessment activity 4.6

XYZ plc currently earns 16p per share. It retains 75 per cent of its profits to reinvest at an

average return of 18 per cent. Its shareholders require a return of 15 per cent. What is the

ex-dividend value of XYZ’s shares? What happens to this value if investors suddenly

become more risk-averse by seeking a return of 20 per cent?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

4.10 PROBLEMS WITH THE DIVIDEND GROWTH MODEL

The Dividend Growth Model, while possessing some convenient properties, has some

major limitations.

■ What if the company pays no dividend?

The company may be faced with highly attractive investment opportunities that cannot

be financed in other ways. According to the model, such a company would have no

value at all! Total retention is fairly common, either because the company has suffered

an actual or expected earnings collapse, or because, as in some European economies

(e.g. Switzerland), the expressed policy of some firms is to pay no dividends at all. The

American computer software firm Microsoft paid its first dividend only in 2003, while

two other computer firms, Dell and Apple, have yet to pay dividends at all. Yet we

observe that shares in such companies do not have zero values. Indeed, nothing could

be further from the truth.

In the case of Dell, $100 invested in its initial public offering in June 1988, would

have been worth about $38,000 by January 2005 following 100 per cent profits reten-

tion. After seven stock splits, 100 shares of Dell was equivalent to 9,600 shares. Apple’s

history is more chequered. It managed to survive the major strategic blunder of omitting

to license out the Macintosh operating system to other manufacturers. Having gone

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 106

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 107

public in 1980 at an issue price of $22, its share price plummeted to $7 in 1998, soaring

to nearly $70 in the dotcom bubble before receding to $15 in 2003. However, this firm

is enjoying a ‘second bite at the cherry’ with the spectacular success of the iPod digi-

tal music player. Its product, iTunes, registered its 200 millionth download in

December 2004, just ten months after launch, making Apple the world leader in legal-

ly downloaded music. During 2004, its shares rose from $20 to $65, including a 20 per-

cent jump in November on the announcement of its first quarter 2004 results.

A distressed company like Apple, in its ‘dog days’, would have a positive value so

long as its management were thought capable of staging a corporate recovery, i.e. the

market is valuing more distant dividends on hopes of a turn-around in earnings. If

recovery is thought unlikely, the company is valued at its break-up value.

For inveterate non-dividend payers, the market is implicitly valuing the liquidating

dividend when the company is ultimately wound up. Until this happens, the compa-

ny is adding to its reserves as it reinvests, and continually enhancing its assets, its

earning power and its value. In effect, the market is valuing the stream of future earn-

ings that are legally the property of the shareholders.

■ Will there always be enough worthwhile projects in the future?

The DGM implies an ongoing supply of attractive projects to match the earnings avail-

able for retention. It is most unlikely that there will always be sufficient attractive proj-

ects available, each offering a constant rate of return, R, sufficient to absorb a given

fraction, b, of earnings in each future year. While a handful of firms do have very

lengthy lifespans, corporate history typically parallels the marketing concept of the

product life cycle – introduction, (rapid) growth, maturity, decline and death – with

paucity of investment opportunities a very common reason for corporate demise. It is

thus rather hopeful to value a firm over a perpetual lifespan. However, remember that

the discounting process compresses most of the value into a relatively short lifespan.

■ What if the growth rate exceeds the discount rate?

The arithmetic of the model shows that if g k

e

, the denominator becomes negative

and value is infinite. Again, this appears nonsensical, but, in reality, many companies

do experience periods of very rapid growth. Usually, however, company growth settles

down to a less dramatic pace after the most attractive projects are exploited, once the

firm’s markets mature and competition emerges. There are two ways of redeeming the

model in these cases. First, we may regard g as a long-term average or ‘normal’ growth

rate. This is not totally satisfactory, as rapid growth often occurs early in the life cycle

and the value computed would thus understate the worth of near-in-time dividends.

Alternatively, we could segment the company’s lifespan into periods of varying growth

and value these separately. For example, if we expect fast growth in the first five years

and slower growth thereafter, the expression for value is:

Note that the second term is a perpetuity beginning in year 6, but we have to find its

present value. Hence it is discounted down to year zero as in the following expression:

where g

f

is the rate of fast growth during years 1–5 and g

s

is the rate of slow growth

beginning in year 6 (i.e. from the end of year 5).

a

5

t 1

D

o

11 g

f

2

11 k

e

2

t

a

q

t 6

D

5

11 g

s

2

11 k

e

2

t

P

o

D

o

11 g

f

2

11 k

e

2

D

o

11 g

f

2

2

11 k

e

2

2

p

D

o

11 g

f

2

5

11 k

e

2

5

¢

D

5

11 g

s

2

1k

e

g

s

2

1

11 k

e

2

5

≤

3Present value of all further dividends4

P

o

3Present value of dividends during year 1–54

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 107

.

108 Part I A framework for financial decisions

However, we may note here that valuation of the dividend stream implies a known

dividend policy. Because dividends are not controlled by shareholders, but by the

firm’s directors, the DGM is more applicable to the valuation of small investment

stakes in companies than to the valuation of whole companies, as in takeover situa-

tions. When company control changes hands, control of dividend policy is also trans-

ferred. It seems particularly unrealistic, therefore, to assume an unchanged dividend

policy when valuing a company for takeover.

■ The P:E ratio and the Constant Dividend Valuation Model

If we examine the P:E ratio more closely, we find it has a close affinity with the growth

version of the DVM. The P:E ratio is defined as price per share (PPS) divided by earnings

per share (EPS). In its reciprocal form, it measures the earnings yield of the firm’s shares:

This equals the dividend yield plus retained earnings (bE) per share. As in the

DGM, the growth version of the DVM, we define the fraction of earnings retained as

b. We can then write:

E

V

D

V

bE

V

1

P:E

EPS

PPS

Earnings

Company value

E

V

The DGM may be used to examine the impact of changes in dividend policy, i.e.

changes in b. Detailed analysis of this issue is deferred to Chapter 17.

Example: the case of unequal growth rates

Consider the case of dividend growth of 25 per cent for years 1–5 and 7 per cent thereafter.

Assuming shareholders require a return of 10 per cent, and that dividend in year zero is 10p,

the value of the share is calculated as follows:

For years 1–5

Year Dividend (p) Discount factor at 10% PV (p)

1 10(1.25) 12.5 0.909 11.4

2 12.50(1.25)

2

15.6 0.826 12.9

3 etc. 19.5 0.751 14.6

4 24.4 0.683 16.7

5 30.5 0.621 18.9

Total 74.5

For later years, we anticipate a perpetual stream growing from the year 5 value at 7 per cent

p.a. The present value of this stream as at the end of year 5 is:

This figure, representing the PV of all dividends following year 5, is now converted into a

year zero present value:

PV £10.88 (PVIF

10.5

) (£10.88 0.621) £6.76

Adding in the PV of the dividends for the first five years, the PV of the share right now is:

PV (£0.745 £6.76) £7.51

D

6

k

e

g

s

D

5

11 7%2

110% 7% 2

30.5p11.072

0.03

32.64p

0.03

£10.88

earnings yield

The earnings per share (EPS)

divided by market share price

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 108

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 109

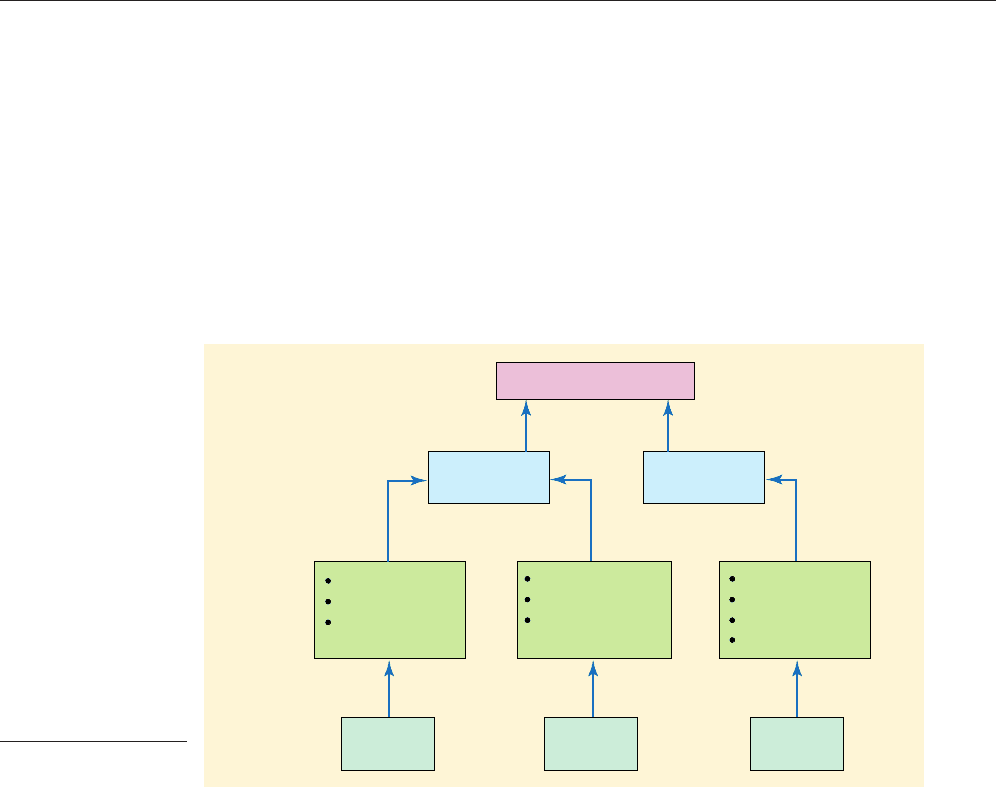

SHAREHOLDER VALUE

Cash flow from

operations

Cost of

capital

Business

strategy

Investment

strategy

Financing

strategy

Sales growth

Margin

Planning horizon

Capital investment

Working capital

Acquisitions

Credit rating

Tax rate

Capital structure

Dividend policy

Corporate

objective

Value

drivers

Strategic

focus

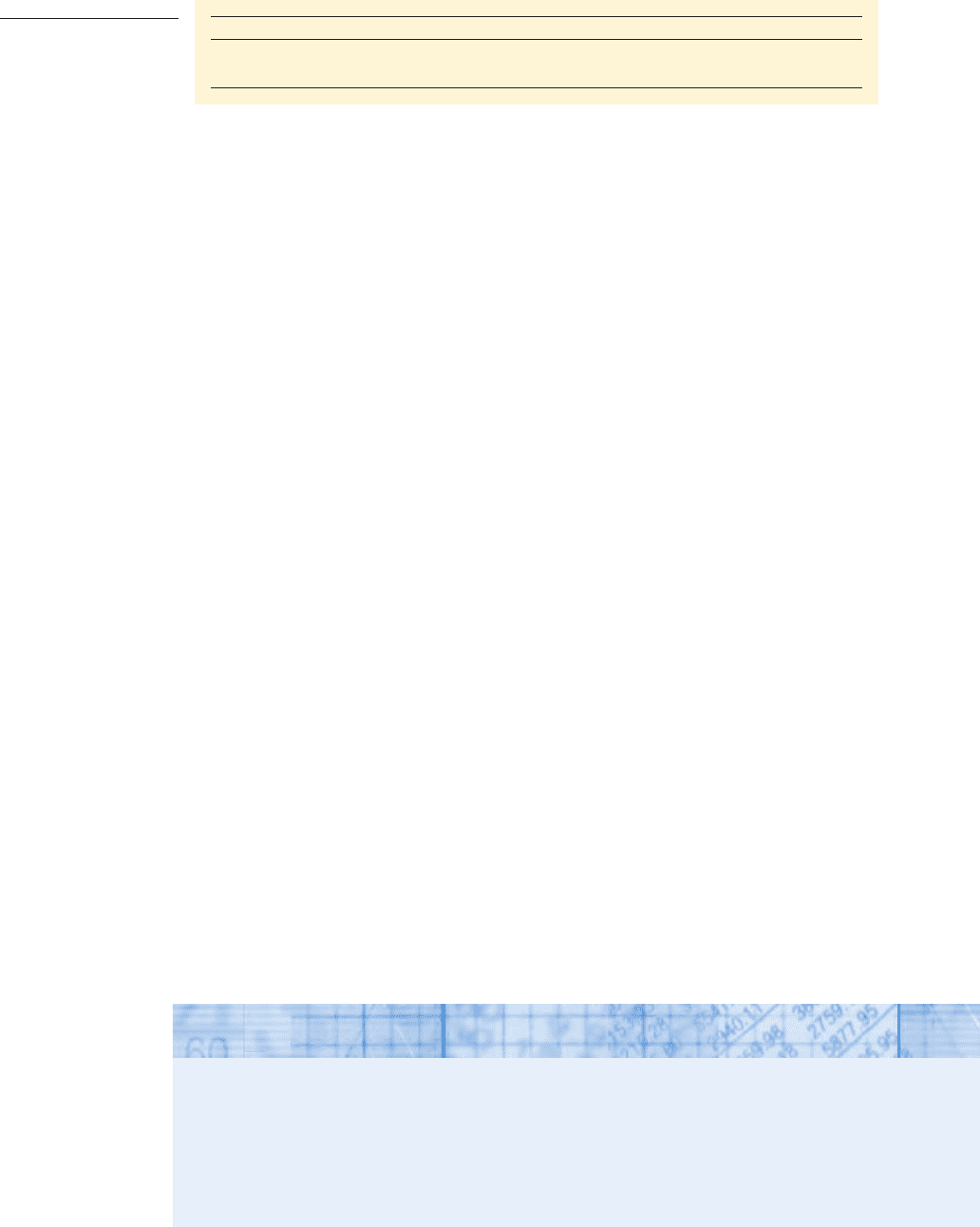

Figure 4.2

Shareholder value

analysis framework

The ratio E/V is the overall rate of return currently achieved. If this equals R, the rate

of return on reinvested funds, then bE/V is equivalent to the growth rate g in the DGM.

In other words, the earnings yield, E/V, comprises the dividend yield plus the growth

rate or ‘capital gains yield’ for a company retaining a constant fraction of earnings and

investing at the rate R. The two approaches thus look very similar. However, this

apparent similarity should not be over-emphasised for three important reasons:

1 The earnings yield is expressed in terms of the current earnings, whereas the DGM

deals with the prospective dividend yield and growth rate, i.e. the former is historic

in its focus, while the latter is forward-looking.

2 The DGM relies on discounting cash returns, while the earnings figure is based on

accounting concepts. It does not follow that cash flows will coincide with account-

ing profit, not least due to depreciation adjustments.

3 For the equivalence to hold, the current rate of return, E/V, would have to equal the

rate of return expected on future investments.

Despite these qualifications, it is still common to find the earnings yield presented

as the rate of return required by shareholders, and hence the cut-off rate for new

investment projects. Unfortunately, this confuses a historical accounting measure with

a forward-looking concept.

4.11 SHAREHOLDER VALUE ANALYSIS

During the 1980s, based on the work of Rappaport (1986), an allegedly new approach

to valuation emerged, called shareholder value analysis (SVA). In fact, it is not really

novel, but a rather different way of looking at value, based on the NPV approach.

The key assumption of SVA is that a business is worth the net present value of its

future cash flows, discounted at the appropriate cost of capital. Many leading US cor-

porations (e.g. Westinghouse, Pepsi and Disney) and a growing number of European

companies (e.g. Philips, Siemens) have embraced SVA because it provides a frame-

work for linking management decisions and strategies to value creation. The focus is

on how a business can plan and manage its activities to increase value for sharehold-

ers and, at the same time, benefit other stakeholders.

How is this achieved? Figure 4.2 shows the relationship between decision-making

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 109

.

110 Part I A framework for financial decisions

and shareholder value. Key decisions – whether strategic, operational, investment or

financial – with important cash flow and risk implications are specified. Managers

should focus on decisions influencing the value drivers, the factors that have greatest

impact on shareholder value. Typically, these include the following:

1 Sales growth and margin. Sales growth and margins are influenced by competitive

forces (e.g. threat of new entrants, power of buyers and suppliers, threat of substi-

tutes and competition in the industry). The balance between sales, growth and prof-

its should be based not only on profit impact, but also on value impact.

2 Working capital and fixed capital investment. Over-emphasis on profit, particularly at

the operating level, may result in neglect of working capital and fixed asset man-

agement. In Section 4.7, the free cash flow approach advocated using cash flows

after meeting fixed and working capital requirements.

3 The cost of capital. A firm should seek to make financial decisions that minimise the

cost of capital, given the nature of the business and its strategies. As will be seen

later, this does not simply mean taking the source of finance that is nominally the

cheapest.

4 Taxation is a fact of business life, especially as it affects cash flows and the discount

rate. Managers need to be aware of the main tax impact on both investment and

financial decisions.

SVA requires specification of a planning horizon, say, five or ten years, and fore-

casting the cash flows and discount rates based on the underlying plans and strategies.

Various strategies can then be considered to assess the implications for shareholder

value.

A particular problem with SVA is specifying the terminal value at the end of the

planning horizon. One approach is to try to predict the value of all cash flows

beyond the planning horizon, based on that of the final year. Another is to simply

take the value of the net assets predicted at the end of the horizon. None of the

methods suggested is wholly satisfactory. It could be argued, however, that SVA

does not have to be used to obtain the value of the business – rather, it can estimate

the additional value created from implementing certain strategies. Assuming these

strategies deliver competitive advantage, and therefore returns in excess of the cost

of capital over the planning horizon, there is no need to wrestle with the terminal

value problem.

The real benefit of SVA is that it helps managers focus on value-creating activities.

Acquisition and divestment strategies, capital structure and dividend policies, per-

formance measures, transfer pricing and executive compensation are seen in a new

light. Short-term profit-related activities may actually be counter-productive in value-

creation terms.

Balti plc: a simple example of SVA

Balti plc is a food manufacturer with a stock market listing. Its shareholders require a return

of 12 per cent. It has just determined its free cash flow for the year at £100,000, as shown in

the first table below.

Depreciation is £75,000 p.a., rather less than capital expenditure of £125,000 p.a. Extra

investment in working capital to support growth plans is £50,000 p.a.

The free cash flows for years 2–5 of its five-year planning horizon are predicted similar-

ly at £150,000, £170,000, £230,000 and £250,000 respectively. Its net asset value after five

years is predicted to be £2.5 million.

The calculation of the value of the firm to its shareholders (i.e. SV) is shown in the sec-

ond table. The SV is the NPV of all future free cash flows, calculated at £2,036,500.

value drivers

Factors that have a powerful

influence on the value of a

business, and the investors’

equity stake

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 110

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 111

Self-assessment activity 4.7

Determine the impact on Balti’s SV if it is able to invest £0.3 million now in order to

extend its competitive advantage period to ten years. Assume free cash flow for years

6–10 stabilises at £250,000 p.a. and that the terminal value in year 10 is £4 million.

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

4.12 ECONOMIC VALUE ADDED (EVA)

Along with SVA comes another piece of ‘alphabet spaghetti’, EVA, a concept trade-

marked by the US consultancy house Stern Stewart (www.sternstewart.com).

Whereas SVA is a forward-looking technique devised for assessing the inherent

value of the equity invested in a firm, EVA is backward-looking, i.e. a measure of

performance. Like SVA, EVA relies heavily on the concept of the cost of capital. It is

used as a device for assessing how much value or wealth a firm actually has creat-

ed. Its roots lie in the accounting concept of Residual Income (e.g. see Horngren et

al. 1998), which is simply the accounting profit adjusted for the cost of using the

capital tied up in an activity.

However, the Stern Stewart version is rather more sophisticated as it attempts to

adjust the recorded profit in various ways. The logic of these adjustments is, broadly,

to avoid recording as a cost the items that are value-creating and that should perhaps

be treated as capital rather than current expenditure. For example, spending on R & D

and on product advertising and promotion contributes to wealth-creation in impor-

tant ways. In addition, any goodwill that has been written off in relation to previous

acquisitions is added back. The general impact of these adjustments – over 150 of these

might be required in a full EVA calculation – is to raise the profit measure and also the

capital employed.

Forecast data for Year 1 £000 Value drivers

Sales 900 Sales growth

less Operating costs (600)

Pre-tax profit 300 Margin

less Tax paid (100) Tax rate

Net operating profit after tax 200

add Depreciation 75

less Fixed capital investment (125) Capital expenditure

less Additional working capital (50) Working capital investment

Free cash flow 100

Calculation of shareholder value:

Forecast cash flows £000

Yr1 Yr2 Yr3 Yr4 Yr5 Terminal Value

100 150 170 230 250

NPV@12% £617,900

PV terminal value £1,418,600

2,500,000

Total NPV £2,036,500 Shareholder Value

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 111

.

112 Part I A framework for financial decisions

Relating this to an all-equity-financed firm, EVA is calculated after making a further

adjustment for the opportunity cost incurred by shareholders when entrusting their

capital to the firm’s directors. The EVA formula can be written as:

EVA NOPAT (k

e

invested capital)

where:

NOPAT the Net Operating Profit After Tax, and after adjustment for the items

mentioned above

k

e

the rate of return required by shareholders

Invested capital Net Assets, or Shareholders’ Funds

To illustrate the concept, consider the data in Table 4.4.

Both firms have the same equity capital employed of £100 m, and both make posi-

tive accounting profits. However, after adjusting for the cost of the equity capital

employed, Firm B has effectively made a loss for investors, i.e. the negative EVA indi-

cates that it has destroyed value.

On the face of it, EVA is a simple and powerful tool for assessing performance,

explaining why it has been adopted by many firms as an internal performance meas-

urement device, e.g. for determining the performance of different operating units.

However, it is by no means problem-free:

1 Few firms have the resources required to compute EVA, division by division, with

the same degree of rigour as the full Stern Stewart model with its myriad required

adjustments.

2 It is based on book value, rather than market values (necessarily so for business

segments).

3 It relies on a fair and reliable way allocating shared overheads across business units,

the Holy Grail of management accountants.

4 It is difficult to identify the cost of capital for individual operating units.

5 It may be dysfunctional if managers are paid according to EVA, especially short-term

EVA. It is quite possible to encounter investment projects that flatter EVA in the short

term by virtue of high initial cash flows but to have a negative NPV. Such projects

might be favoured by managers who are paid by EVA. Similarly, some long-term

projects that take time and money to develop may lower EVA in the early years but

have a positive NPV. These, of course, could be rejected under an EVA regime.

The verdict is yet to be delivered on EVA, but like many other management tools, it

is probably inadequate when used alone – it is one way of looking at the picture that

should be supplemented by other perspectives.

We have discussed the reasons why financial managers may wish to value their own

and other enterprises, the problems likely to be encountered and the main valuation

techniques available.

Given the uncertainties involved in valuation, it seems sensible to compare the

implications of a number of valuation models and to obtain valuations from a number

of sources. A pooled valuation is unlikely to be correct, but armed with a range of

SUMMARY

Table 4.4

Calculation of EVA

NOPAT Equity EVA

Firm A £20 m £100 m 15% £20 m £15 m £5 m

Firm B £10 m £100 m 15% £10 m £15 m (£5 m)

k

e

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 112

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 113

valuations, managers should be able to develop a likely consensus valuation. This con-

sensus is, after all, what a market value represents, based upon the views of many

times more market participants. There should be no stigma attached to obtaining more

than one opinion–doctors do not hesitate to call for second opinions when unsure

about medical diagnoses.

Key points

■ An understanding of valuation is required to appreciate the likely effect of invest-

ment and financial decisions, to value other firms for acquisition, and to organise

defences against takeover.

■ Valuation is easier if the company’s shares are quoted. The market value is ‘correct’

if the EMH applies, but managers may have withheld important information.

■ Using published accounts is fraught with dangers, e.g. under-valuation of fixed

assets.

■ Some companies attempt to value the brands they control. An efficient capital mar-

ket will already have valued these, but not necessarily in a fully informed manner.

■ The economic theory of value tells us that the value of any asset is the sum of the

discounted benefits expected to accrue from owning it.

■ A company’s earnings stream can be valued by applying a P:E multiple, based upon

a comparable, quoted surrogate company.

■ Some observers like to compare the EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax

Depreciation and Amortisation) with share price for different companies as a

cross-check on valuation. Market-based EBITDA multiples can be used as valua-

tion tools.

■ Valuing a company on a DCF basis requires us to forecast all future investment cap-

ital needs, tax payments and working capital movements.

■ Valuation of unquoted companies is highly subjective. It requires examination of

similar quoted companies and applying discounts for lack of marketability.

■ The value of a share can be found by discounting all future expected dividend

payments.

■ The retention of earnings for worthwhile investment enhances future earnings, div-

idends and, therefore, the current share price.

■ The Dividend Valuation Model must be treated with caution. It embodies many

critical assumptions.

■ Economic Value Added (EVA) is the residual profit after allowing for the charge for

the firm’s use of investors’ capital.

■ The two main lessons of valuation are: use a variety of methods (or consult a vari-

ety of experts) and don’t expect to get it exactly right.

Further reading

Comprehensive treatments of share and company valuation are quite rare: Koller et al. (2004) is

probably the best available. A good overview can be found in Chapter 15 (the contribution by

Davies) of Firth and Keane (1986).

The brand valuation issue is addressed by Murphy (1989) and Barwise et al. (1989).

Young (1997) provides a practical application of the EVA concept.

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 113

.

Questions with a coloured number

have solutions in Appendix B on page 693.

1 Amos Ltd has operated as a private limited company for 80 years. The company is facing increased competi-

tion and it has been decided to sell the business as a going concern.

The financial situation is as shown on the balance sheet:

QUESTIONS

114 Part I A framework for financial decisions

Balance Sheet as at 30 June 1999

£££

Fixed assets

Premises 500,000

Equipment 125,000

Investments 50,000

675,000

Current assets

Stock 85,000

Debtors 120,000

Bank 25,000

230,000

Creditors: amounts due within one year

Trade creditors (65,000)

Dividends (85,000

)

(150,000

)

Net current assets 80,000

Total assets less current liabilities 755,000

Creditors: amounts due after one year

Secured loan stock (85,000)

Net assets 670,000

Financed by

Ordinary shares (50p par value) 500,000

Reserves 55,000

Profit and loss account 1

15,000

Shareholders’ funds 670,000

The current market values of the fixed assets are estimated as:

Premises 780,000

Equipment 50,000

Investments 90,000

Only 90 per cent of the debtors are thought likely to pay.

Required

Prepare valuations per share of Amos Ltd using:

(i) Book value basis

(ii) Adjusted book value

2 The Board of Directors of Rundum plc are contemplating a takeover bid for Carbo Ltd, an unquoted compa-

ny which operates in both the packaging and building materials industries. If the offer is successful, there are

no plans for a radical restructuring or divestment of Carbo’s assets.

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 114