Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 95

2 Methods based on market observation

Here, the value of the brand is determined by looking at the prices obtained in trans-

actions involving comparable assets, for example, in mergers and acquisitions. This

may be based on a direct price comparison, or by separating the market value of the

company from its net tangible assets or by looking at the P:E multiple at which the deal

took place, compared to similar unbranded businesses. Although the logic is more

acceptable, the approach suffers from the infrequency of transactions involving similar

brands, given that individual brands are supposedly unique.

3 Methods based on economic valuation

In general, the value of any asset is its capitalised net cash flows. If these can be readi-

ly identified, this approach is viable, but it requires separation of the cash flows associ-

ated with the brand from other company cash inflows. The ‘brand contribution

method’ looks at the earnings contributed by the brand over and above those generat-

ed by the underlying or ‘basic’ business. The identification, separation and quantifica-

tion of these earnings can be done by looking at the financial ratios (e.g. profit margin,

ROI), of comparable non-branded goods and attributing any differential enjoyed by the

brand itself as stemming from the value of the brand, i.e. the incremental value over a

standard or ‘generic’ product.

For example, if a brand of chocolates enjoys a price premium of £1 per box over a

comparable generic product, and the producer sells ten million boxes per year, the

value of the brand is imputed as (£1 10 m) £10 m p.a., which can then be dis-

counted accordingly to derive its capital value. Alternatively, looking at comparative

ROIs as between the branded manufacturer and the generic, we may find a 5 per cent

differential. If capital employed by the former is £100 million, this implies a profit dif-

ferential of £5 million, which is then capitalised accordingly.

Such approaches beg many questions about the comparability of the manufacturers

of branded and non-branded goods, the life span assumed, and the appropriate dis-

count rate. Adjustments should also be made for brand maintenance costs, such as

advertising, that result in cash outflows.

4 Brand strength methods

Other, more intuitive, methods have been devised which purport to capture the

‘strength’ of the brand. This involves assessing factors like market leadership, longevi-

ty, consumer esteem, recall and recognition, and then applying a subjectively deter-

mined multiplier to brand earnings in order to derive a value. Although appealing, the

subjectivity of these approaches divorces them from commercial reality.

No broad measure of agreement has yet been reached about the best method to use

in brand valuation, or whether the whole exercise is meaningful. Indeed, a report com-

missioned by the ICAEW (1989), which rejected brand valuation for Balance Sheet

purposes, was said to have been welcomed by its sponsors. The report claimed that

brand valuation ‘is potentially corrosive to the whole basis of financial reporting’,

arguing that Balance Sheets do not purport to be statements of value!

Capturing the indefinable value of a brand

FT

European companies find them-

selves having to value their

intangibles

Two-thirds of Coca-Cola’s market

value is attributable to one asset: the

soft drink maker’s brand. So said

Interbrand, the consulting firm, last

year when it ranked the Coca-Cola

name as the world’s most expensive

at $67bn.

Its contribution to the company’s

worth is far from unusual. Brands,

together with other intangibles such

Continued

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 95

.

96 Part I A framework for financial decisions

as customer relationships and tech-

nology, account for an ever-growing

proportion of corporate value: 48 per

cent, according to PwC research on

the American M&A market in 2003.

European Union companies have

not had cause to put detailed num-

bers on what makes them what they

are. But that is now changing,

because international accounting

standards force acquirers to spell out,

item by item, the value of the busi-

nesses they are buying.

That has created a new market for

expertise from the US, where intan-

gibles have been shown separately

on balance sheets for several years.

Two specialist groups are in expan-

sion mode in Europe – American

Appraisal and Standard & Poor’s

Corporate Value Consulting – while

the big four accounting firms are

plugging their services more heavily.

But as Sarpel Ustunel, senior

manager at American Appraisal in

London explains, there is no simple

way to put a price on something ‘that

is difficult to put your arms around’.

Mr Ustunel, one of 200 staff in

Europe, says there are several options

with brands.

One method is to calculate what

proportion of a company’s future

earnings can be attributed to its

property, machinery and other assets.

The rest should represent the value

of the brand. But this assumes there

are already neat values for the other

intangibles.

Another way is to estimate how

much it would cost to buy the brand if

the company did not own it already.

Alternatively, and if possible, val-

uers look for the equivalent of two

tins of soup made to exactly the same

specifications, and sold on the same

supermarket shelf – but one under a

specialist mark and one under the

supermarket’s own label. ‘Whatever

the difference in price is attributable

to the brand,’ says Mr Ustunel.

Valuing intellectual property, too,

is vexatious. If a patent for a similar

technology has been sold before that

price can be a starting point, he says,

but such data is difficult to come by.

The solution is to talk to as many

people as possible about the technolo-

gy’s importance. ‘Engineers,’ he cau-

tions, ‘can be overenthusiastic in

explaining what their technology is

about. Once you talk to the acquirer

you may find they were unaware it

existed.’

Valuing intangibles takes account-

ing, and the auditors who have to

check financial statements, into a

murky area. Given the need to make

assumptions and estimates, Richard

Winter, partner in valuation and

strategy at PwC, concedes: ‘There is

a degree of rattle room.’

People may think there is a defin-

itive answer, but inevitably there is

scope for judgment.’

Critics say the whole exercise is

misleading because it implies a pre-

cision that is not really there.

‘The huge danger with going into

inordinate detail is that readers of

accounts cannot understand how the

numbers arise,’ says Ian Robertson,

president of the Institute of Chartered

Accountants of Scotland.

Mr Ustunel accepts there are no

black and white answers, but says

putting more numbers on the bal-

ance sheet is a useful step forward.

‘Would you rather I tell you there

are three cupboards, a table and a

few chairs in this room,’ he asks, ‘or

would you prefer just to know there

is some furniture?’

Source: Barney Jopson, Financial Times,

9 February 2005.

■ The role of the NAV

Generally speaking, the NAV, even when based on reliable accounting data, only really

offers a guide to the lower limit of the value of owners’ equity, but even so, some form

of adjustment is often required. Assets are often revalued as a takeover defence tactic.

The motive is to raise the market value of the firm and thus make the bid more expen-

sive and difficult to finance. However, the impact on share price will be minimal

unless the revaluation provides new information, which largely depends on the per-

ceived quality and objectivity of the ‘expert valuation’.

We conclude that while the NAV may provide a useful reference point, it is unlikely

to be a reliable guide to valuation. This is largely because it neglects the capacity of the

assets to generate earnings. We now consider the commonest of the earning-based

methods of valuation, the use of price-to-earnings multiples.

4.4 VALUING THE EARNINGS STREAM: P:E RATIOS

It is well known that accounting-based measures of earnings are suspect for several rea-

sons, including the arbitrariness of the depreciation provisions (usually based on the

historic cost of the assets) and the propensity of firms to designate unusually high items

of cost or revenue as ‘exceptional’ (i.e. unlikely to be repeated in magnitude in future

years). Yet we find that one of the commonest methods of valuation in practice is based

on accounting profit. This method uses the price-to-earnings multiple or P:E ratio.

price-to-earning multiplier/

P:E ratio

Another way of expressing

the PER

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 96

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 97

■

The meaning of the P:E ratio

As we saw in Chapter 2, the P:E ratio is simply the market price of a share divided by

the last reported earnings per share (EPS). P:E ratios are cited daily in the financial

press and vary with market prices. A P:E ratio measures the price that the market

attaches to each £1 of company earnings, and thus superficially (at least) is a sort of

payback period. For example, for its financial year 2004–5, Severn Trent Water plc

reported EPS of 56p. Its share price in late August 2005 was 958p producing a P:E

ratio of 18.7. Allowing for daily variations, the market seemed to indicate that it was

prepared to wait 18–19 years to recover the share price, on the basis of the latest earn-

ings. So would a higher P:E ratio signify a willingness to wait longer? Not necessari-

ly, because companies that sell at relatively high P:E ratios do so because the market

values their perceived ability to grow their earnings from the present level. Contrary

to some popular belief, a high P:E ratio does not signify that a company has done

well, but that it is expected to do better in the future. (Not that they always do – wit-

ness the very high P:E ratios among ‘dotcom’ companies in 1999–2000.)

The P:E ratio varies directly with share price, but it also derives from the share price,

i.e. from market valuation, so how does this help with valuation? Investment analysts

typically have in mind what an ‘appropriate’ P:E ratio should be for particular share

categories and individual companies, and look for disparities between sectors and

companies. If, for example, BP is selling at a P:E ratio of say 17 with EPS of 30p, and

Shell has EPS of 25p with a P:E ratio of 14, then their share values may look out of line.

Assuming Shell’s shares are correctly valued at (14 25p) 350p, then BP’s shares,

priced at (17 30p) 510p, might appear overvalued.

Of course, there is a circularity here – this conclusion relies on the assumption that

Shell rather than BP is correctly valued. Moreover, despite the apparent similarity of

these two oil majors, there may be very good reasons why they should be valued dif-

ferently. BP operates further ‘upstream’ (away from the final consumer) than Shell,

and hence the sustained upward pressure on oil prices during 2005 would work to its

advantage. Meanwhile, Shell was experiencing major problems concerning the accu-

racy of its accounting and its corporate governance, both depressing share price.

Using P:E ratios to detect under- or over-valuation implies that markets are slow or

inefficient processors of information, but there are reliable rough benchmarks that

can be utilised. The industry benchmark is established by one or more transactions,

against which other deals in the same industry can be judged, and exceptions identi-

fied. In some industries, analysts use benchmarks other than the earnings figure

implicit in the P:E ratio. Some examples are multiples of billings in advertising, sale

price per room in hotels, price per subscriber in mail order businesses, price per bed

in nursing homes, and the more grisly ‘stiff ratio’ (value per funeral) in the undertak-

ing business. At the height of the ‘dotcom boom’, some analysts attempted to explain

the stratospheric valuations of internet companies in terms of number of ‘hits’ or vis-

its to the site in question. More analysts are now utilising multiples based on cash flow.

This development hints at the major problem with using P:E ratios – it relies on

accounting profits rather than the expected cash flows which confer value on any item.

We now consider cash-flow-oriented approaches to valuation.

Self-assessment activity 4.3

XYZ plc, which is unquoted, earns profit before tax of £80 million. It has issued 100 mil-

lion shares. The rate of Corporation Tax is 30 per cent.

A similar listed firm sells at a P:E ratio of 15:1.What value would you place on XYZ’s shares?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 97

.

98 Part I A framework for financial decisions

4.5 EBITDA – A HALFWAY HOUSE

Cash flows and profits differ due to application of accruals accounting principles, but

value depends upon cash generating ability rather than ‘profitability’. An intermediate

concept currently in vogue is that of EBITDA, an unattractive acronym standing for

Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation. EBITDA is equiva-

lent to operating profit with depreciation and amortisation (the writing-down of intan-

gible assets) added back. As such, it is a measure of the basic operating cash flow before

deducting tax, but ignoring working capital movements.

Many companies use EBITDA as a measure of performance, especially when

related to capital employed. For example, E.On Ag www.eon.com the German utili-

ty and chemicals group, defines EBITDA as ‘earnings before interest, taxes, depre-

ciation and goodwill amortisation’, and relates it to capital employed to calculate a

key indicator for monitoring the performance of business units. This is essentially

a cash-based measure of return on capital employed, which is not influenced by the

capital structure. In other words, being expressed before interest and tax, it is inde-

pendent of financing policy, and thus the ‘share-out’ of the operating profit as

between interest payments, taxation and profits for shareholders. (It should be

noted that E.On adjusts the EBITDA to allow for exceptional items such as gains

and losses on disposals.)

However, EBITDA is essentially a performance measure. It can only be used in valua-

tion if we look at the way in which the market values other companies’ EBITDAs. As

with P:E ratios, comparison with other companies is needed as a reference point. For

example, in late 2000, when Coca-Cola was evaluating Quaker as an acquisition candi-

date, observers noted that Coke was prepared to pay some 16 times Quaker’s EBITDA,

which appeared expensive, being well above recent deals in the US food sector.

Attempting to explain this, the Financial Times suggested that if the Quaker food divi-

sion were valued at the then prevailing industry average of ten times EBITDA, then the

bid price implied an EBITDA multiple of 25 times for the real jewel in Quaker’s crown,

the fast-growing Gatorade sports drink.

In July 2001, the US oil firm Amerada Hess acquired Triton Energy in order to acquire

its upstream capability and exploration skills. The price paid per share was $45 cash, a pre-

mium of 50 per cent to Triton’s previous share price. The comment was made that it was

paying ‘top dollar’. Including some $500 million of debt, Amerada was laying out nine

times 2001 EBITDA, in line with similar deals involving acquisition of proven reserves but

ahead of valuations for oil companies oriented more towards downstream activities.

Like a P:E multiple, an EBITDA multiple used in valuation stems from the value

which the market attaches to other companies’ EBITDAs, which invites the question

of how it values those other companies, i.e. the EBITDA multiple is led by the valua-

tion. Moreover, even when used crudely as a rough-and-ready comparison of value,

one should appreciate that it is still based on accounting earnings. Although gross of

depreciation and special items, it is still subject to different accounting practices

between firms at the operating level, e.g. stock valuation.

Continuing to focus on income-generating methods, we now examine the genuine

article, Discounted Cash Flow.

4.6 VALUING CASH FLOWS

The value of any asset depends upon the stream of benefits that the owner expects to

enjoy from his or her ownership. Sometimes these benefits are intangible, as in the case

of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, which simply gives aesthetic pleasure to people looking at it.

In the case of financial assets, the benefits are less subjective. Ownership of ordinary

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 98

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 99

Self-assessment activity 4.4

Navenby has a value of £1.325 million, but a major part of this reflects the eventual resale

value of the assets.What final asset value would enable investors to just break even?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

shares, for example, entitles the holder to receive a stream of future cash flows in the

form of dividends plus a lump sum when the shares are sold on to the next purchaser,

or if held until the demise of the company, a liquidating dividend when it is finally

wound up. In the case of an all-equity financed company, the earnings over time should

be compared on an equivalent basis by discounting them at the minimum rate of return

required by shareholders or the cost of equity capital (henceforth denoted as k

e

).

■ Valuing a newly created company: Navenby plc

Navenby plc is to be formed by public issue of one million £1 shares. It proposes to pur-

chase and let out residential property in a prime location. It has been agreed that, after

five years, the company will be liquidated and the proceeds returned to shareholders.

The fully-subscribed book value of the company is £1 million, the amount of cash

offered for the shares. However, this takes no account of the investment returns likely

to be generated by Navenby. In the prospectus inviting investors to subscribe, the com-

pany announced details of its £1 million investment programme. It has concluded a

deal with a builder to purchase a block of properties on very attractive terms, as well

as instructing a letting agency to rent out the properties at a guaranteed income of

£130,000 p.a. Based upon past property price movements, Navenby’s management esti-

mate 70 per cent capital appreciation over the five-year period. All net income flows

(after management fees of £30,000 p.a.) will be paid out as dividends.

In the absence of risk and taxation, Navenby is easy to value. Its value is the sum of

discounted future expected cash flows (including the residual asset value) from the

project i.e. (£130,000 – £30,000) p.a., plus the eventual sale proceeds:

Year

12345

Net rentals p.a. (£m) 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1

Sale proceeds (£m) 1.7

If shareholders require, say, a 12 per cent return for an activity of this degree of risk,

the present value (PV) of the project is found using the relevant annuity (PVIFA) and

single payment (PVIF) discount factors, introduced in Chapter 3, as follows:

PV (£0.1 m PVIFA

(12,5)

) (£1.7 m PVIF

(12,5)

)

(£0.1 m 3.6048) (£1.7 m 0.5674)

(£0.361 m £0.964 m) £1.325 m

The value of the company is £1.325 million and shareholders are better off by £0.325

million. In effect, the managers of Navenby are offering to convert subscriptions of

£1 million into cash flows worth £1.325 million. If there is general consensus that these

figures are reasonable estimates, and if the market efficiently processes new informa-

tion, then Navenby’s share price should be £1.325 m/1 m £1.325 when information

about the project is released. If so, Navenby will have created wealth of £0.325 million

for its shareholders.

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 99

.

100 Part I A framework for financial decisions

■ The general valuation model (GVM)

In analysing Navenby, we applied the general valuation model, which states that the value

of any asset is the sum of all future discounted net benefits expected to flow from the asset:

where X

t

is the net cash inflow or outflow in year t, k

e

is the rate of return required by

shareholders and n is the time period over which the asset is expected to generate

benefits.

It should be noted that for a newly-formed company, such as Navenby, the valua-

tion expression can be written in two ways:

value cash subscription NPV of proposed activities

or

value present value of all future cash inflows less outflows

These are equivalent expressions. The value of Navenby is £1.325 million, and the

net present value of the investment is £0.325 million, i.e. it would be rational to pay up

to £0.325 million to be allowed to undertake the investment opportunity. Valuation of

Navenby is relatively straightforward partly because the company has only one activ-

ity, but primarily because most key factors are known with a high degree of precision

(although not the residual value). In practice, future company cash flows and divi-

dends are far less certain.

■ The oxygen of publicity

Many corporate managers are somewhat parsimonious in their release of information to

the market. Their motives are often understandable, such as reluctance to divulge com-

mercially sensitive information. As a result, many valuations are largely based on inspired

guesswork. The value of a company quoted on a semi-strong efficient share market can

only be the product of what information has been released, supplemented by intuition.

Yet company chairpeople are often heard to complain that the market persistently

undervalues ‘their’ companies. Some, for example Richard Branson (Virgin) and

Andrew Lloyd-Webber (Really Useful Group), in exasperation, even mounted buy-

back operations to repurchase publicly held shares. The ‘problem’, however, is often

of their own making. The market can only absorb and process that information which

is offered to it. Indeed, information-hoarding may even be interpreted adversely. If

information about company performance and future prospects is jealously guarded,

we should not be surprised when the valuation appears somewhat enigmatic.

V

o

a

n

t 0

X

t

11 k

e

2

t

4.7 THE DCF APPROACH

The previous section implies that we should rely on a discounted cash flow approach.

After all, it is rational to attach value to future cash proceeds rather than to accounting

earnings, which are based on numerous accounting conventions, including the deduction

of a non-cash charge for depreciation. Given that depreciation is not a cash item, surely

all we need do is to take the reported profit after tax (PAT) figure and add back depreci-

ation to arrive at cash flow and then discount accordingly?

As a first approximation, we could thus value a company by valuing the stream of

annual cash flows as measured by:

Cash flow (operating profit depreciation)

(cash revenues cash operating costs)

general valuation model

A family of valuation models

that rely on discounting future

cash flows to establish the

value of the equity or the

whole enterprise

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 100

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 101

The depreciation charge is added back because it is merely an accounting adjust-

ment to reflect the fall in value of assets. If firms did replace capacity as it expired, in

principle, this investment should equate to depreciation. In practice, however, only

by coincidence does the annual depreciation charge accurately measure the annual

capital expenditure required to maintain production, and thus earnings capacity.

Moreover, most companies need investment funds for growth purposes as well as for

replacement. The value of growing companies depends not simply on the earning

power of their existing assets, but also on their growth potential; in other words, the

NPV of the cash flows from all future non-replacement investment opportunities.

This suggests a revised concept of cash flow. To obtain an accurate assessment of

value, we should assess total ongoing investment needs and set these against antici-

pated revenue and operating cost flows; otherwise we might over-value the company.

■ Valuation and free cash flow (FCF)

The inflow remaining net of investment outlays is referred to as free cash flow (i.e.

‘free’ of investment expenditure).

Free cash flow [revenuesoperating costs] [interest payments] [taxes]

[depreciation][investment expenditure]

Using this measure, the value of the owners’ stake in a company is the sum of future

discounted free cash flows:

This approach removes the problem of confining investment financing to reten-

tions, as in the Dividend Growth Model (see below). However, we encounter signifi-

cant forecasting problems in having to assess the growth opportunities and their

financing needs in all future years.

Unfortunately, the accounting data for revenues and operating costs upon which this

approach is based may fail to reflect cash flows due to movements in the various items

of working capital. For example, a sales increase may raise reported profits, but if made

on lengthy credit terms, the effect on cash flow is delayed. Indeed, the net effect may be

negative if suppliers of additional raw materials insist on payment before debtors settle.

It is important to mention another distortion. Stock-building, either in advance of

an expected sales increase or simply through poor inventory control, can seriously

impair cash flow, although the initial impact on profit reflects only the increased stock-

holding costs.

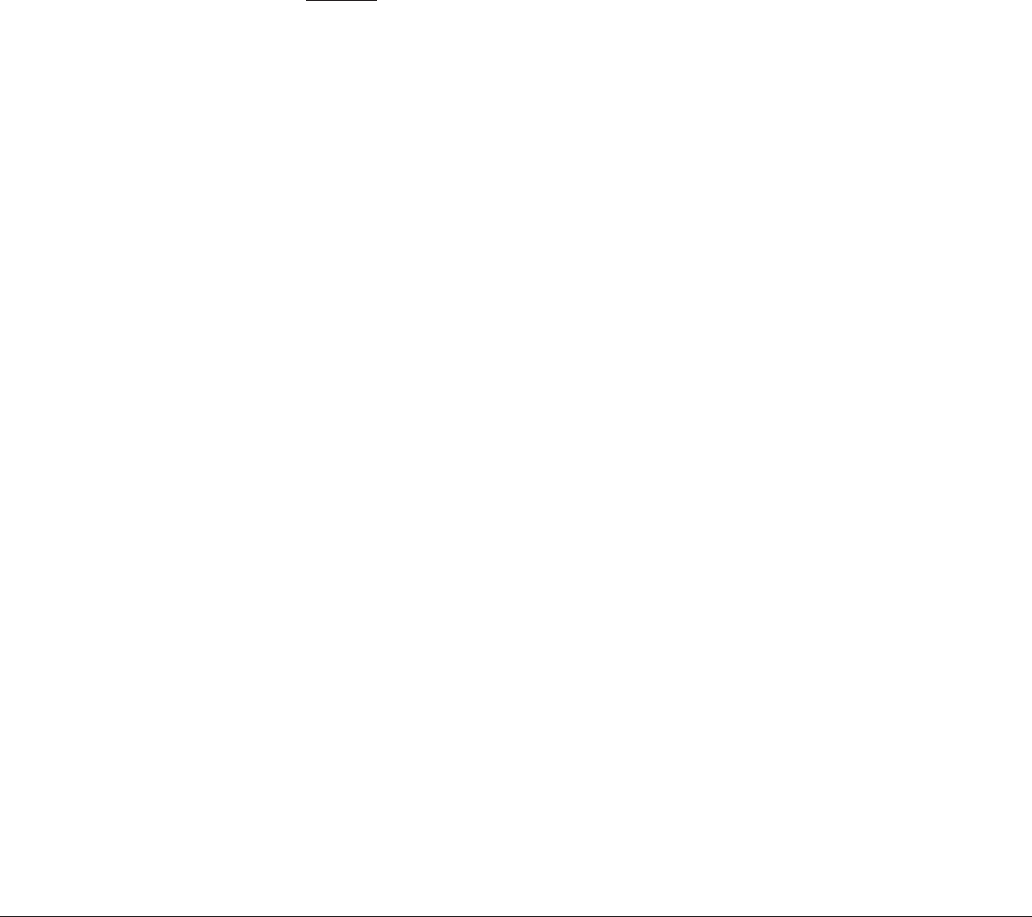

For these and similar reasons, accurate estimation of cash flow involves forecasting not

merely all future years’ sales, relevant costs and profits, but also all movements in work-

ing capital. Alternatively, one may assume that these factors will have a net cancelling

effect, which may be reasonable for longer-term valuations but much less appropriate for

short time-horizon valuations, as in the case of high-risk activities. Figure 4.1 provides a

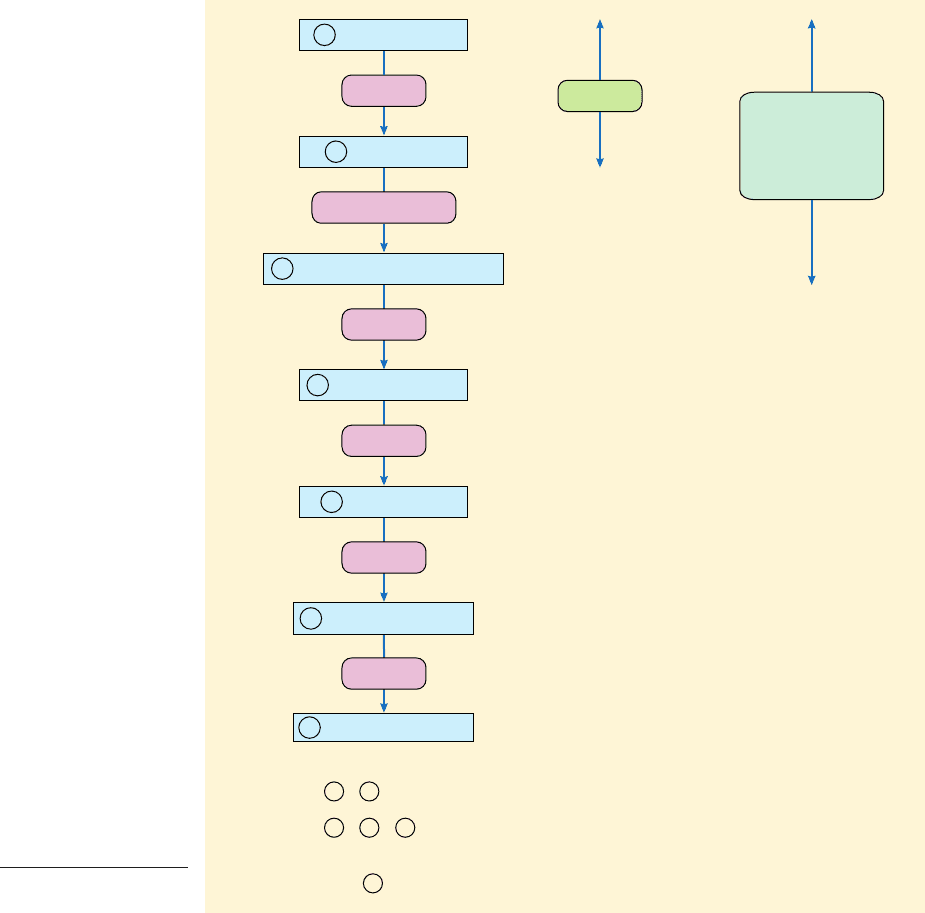

schema to show the calculation of FCF, and how it relates to other cash flow concepts.

V

o

a

n

t 1

FCF

11 k

e

2

t

Self-assessment activity 4.5

What is the free cash flow for the following firm?

Operating Profit (after depreciation of £2 m) £25 m

Interest paid £1 m

Tax rate 30%

Investment expenditure £3 m

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 101

.

102 Part I A framework for financial decisions

■ A warning!

The term ‘free cash flow’ is used in a wide variety of ways in practice. Here, we use it

to signify cash left in the company after meeting all operating expenditures, all

mandatory expenditures such as tax payments, and investment expenditure. It focus-

es on what remains for the directors to spend either as dividend payments, repayment

of debts, acquisition of other companies or simply to build up cash balances. This

broad definition is necessary because the cash inflow figure is defined to include rev-

enues from both existing and future operations. Consequently, the investment expen-

diture required to generate enhancements in revenue must be allowed for. By the same

token, a growth factor should be incorporated in the operating profit figures to reflect

the returns on this investment.

A narrower definition could be used to confine cash inflows to those relating to

existing operations and investment, and expenditures to those required simply to

PLUS

PLUS/MINUS

LESS

LESS

LESS

NET CASH

FLOW FROM

OPERATING

ACTIVITIES

EBITDA

1 Operating Profit

2 Depreciation

7 FREE CASH FLOW

3 Changes in Working Capital

4 Interest Payments

5 Tax Payments

:

Notes

1 + 2 is roughly equivalent to EBITDA.

1 + 2 + 3 corresponds to ‘Net Cash Flow from Operating Activities’

found on a UK firm’s Cash Flow Statement.

Item 6 is sometimes confined to Replacement Capital Expenditure.

6 Capital Expenditure

EQUALS

Figure 4.1

Calculating free cash

flow (FCF)

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 102

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 103

make good wear and tear, i.e. replacement outlays. This has the merit of expressing the

cash flow before strategic investment, over which directors have full discretion. It also

avoids financing complications, e.g. where a company wishes to invest more than its

free cash flows, thus requiring additional external finance, which may distort the actu-

al cash flow figure, as reflected in the cash flow statement.

However, this yields a very restricted, static vision of the business, neglecting the

strategic opportunities and their costs and benefits, which are truly responsible for

imparting a major portion of value in practice. Failure to capture these longer-term

strategic opportunities could yield a valuation well short of the market’s assessment.

The problem of defining free cash flows is compounded by examination of UK

company reports. Listed UK companies are obliged to present cash flow statements

which report the net change in cash and near cash holdings over the year. This is a

backward-looking statement which says more about past liquidity changes than

future cash flows. Some firms do report a figure for ‘free cash flow’, but often with-

out defining it. Jupe and Rutherford (1997) analysed the reports of 222 of the 250

largest listed UK companies. They found that just 21 disclosed a free cash flow fig-

ure, although only 14 used the term itself, and few of these supplied either a defini-

tion or a breakdown. Analysis of the comments of 13 companies appeared to reveal

the use of 13 different definitions. Clearly, this is an area where care is required in

definition and usage.

4.8 VALUATION OF UNQUOTED COMPANIES

The inexact science of valuing a company or its shares is made considerably simpler if

the firm’s shares are traded on a stock market. If trading is regular and frequent, and if

the market has a high degree of information efficiency, we may feel able to trust mar-

ket values. If so, the models of valuation merely provide a check, or enable us to assess

the likely impact of altering key parameters such as dividend policy or introducing

more efficient management.

With unquoted companies, the various models have a leading rather than a sup-

porting role, but give by no means definitive answers. Attempts to use the models

inevitably suffer from information deficiencies, which may be only partially over-

come. For example, in using a P:E multiple, a question arises concerning the appro-

priate P:E ratio to apply. Many experts advocate using the P:E ratio of a ‘surrogate’

quoted company, one that is similar in all or most respects to the unquoted subject.

One possible approach is to take a sample of ‘similar’ quoted companies, and find a

weighted average P:E ratio using market capitalisations as weights.

However, the shares of a quoted company are, by definition, more marketable

than those of unquoted firms, and marketability usually attracts a premium, sug-

gesting a lower P:E ratio for the unquoted company. Any adjustment for this factor

is bound to be arbitrary, and different valuation experts might well apply quite dif-

ferent adjustment factors.

Furthermore, a major problem in valuing and acquiring unquoted companies is the

need to tie in the key managers for a sufficient number of years to ensure the recovery

of the investment. The cost of such ‘earn-outs’, or ‘golden handcuffs’, could be a major

component of the purchase consideration.

In principle, all the valuation approaches explained in this chapter are applicable to

valuing unquoted companies, so long as suitable surrogates can be found, or if reliable

industry averages are available. If surrogate data cannot be used, valuation becomes

even more subjective. In these circumstances, it is not unusual to find valuers con-

vincing themselves that company accounts are objective and reliable indicators of

value. While accounts may offer a veneer of objectivity, we need hardly repeat the pit-

falls in their interpretation.

golden handcuffs

An exceptionally good remuner-

ation package paid to execu-

tives to prevent them from

leaving

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 103

.

104 Part I A framework for financial decisions

4.9 VALUING SHARES: THE DIVIDEND VALUATION MODEL

The Navenby example (discussed in Section 4.6) demonstrates why investors pur-

chase and hold ordinary shares. Shareholders attach value to shares because they

expect to receive a stream of dividends and hope to make an eventual capital gain.

However, Navenby was a special case because it proposed to pay out all its earnings

as dividend – few companies do this in reality. Although shareholders are legally

entitled to the earnings of a company, in the case of a company with a dispersed own-

ership body, their influence on the dividend payout is limited by their ability to exert

their voting power on the directors. Other things being equal, shareholders prefer

higher to lower dividends, but issues such as capital investment strategy and taxation

may cloud the relationship between dividend policy and share value. With this reser-

vation in mind, we now develop the Dividend Valuation Model (DVM). This is

appropriate for valuing part shares of companies rather than whole enterprises. This

is because minority shareholders have little or no control over dividend policy and

thus it is reasonable to project past dividend policy, especially as companies and their

owners are known to prefer a steadily rising dividend pattern rather than more errat-

ic payouts. Conversely, if control changes hands, the new owner can appropriate the

earnings as it chooses.

■ Valuing the dividend stream

The DVM states that the value of a share now, P

o

, is the sum of the stream of future dis-

counted dividends plus the value of the share as and when sold, in some future year, n:

However, since the new purchaser will, in turn, value the stream of dividends after

year n, we can infer that the value of the share at any time may be found by valuing

all future expected dividend payments over the lifetime of the firm. If the lifespan is

assumed infinite and the annual dividend is constant, we have:

This is an application of valuing a perpetuity, the mathematics of which were

explained in Appendix III to Chapter 3.

For example, the shares of a company whose owners require a return of 15 per cent,

and which is expected to pay a constant annual dividend of 30p per share through

time would be valued thus:

£2.00 per share

In reality, the assumptions underlying this basic model are suspect. The annual div-

idend is unlikely to remain unchanged indefinitely, and it is difficult to forecast a vary-

ing stream of future dividend flows. To a degree, the forecasting problem is moderated

by the effect of applying a risk-adjusted discount rate because more distant dividends

are more heavily discounted. For example, discounting at 20 per cent, the present

value of a dividend of £1 in 15 years’ time is only 6p, while £1 received in 20 years adds

only 3p to the value of a share. In other words, for a plausible cost of equity, we lose

little by assuming a time-horizon of, say, 15 years. Even so, reliable valuations still

require estimates of dividends over the intervening years, and by the same token, any

errors will have a magnified effect during this period.

P

o

30p

0.15

P

o

a

q

t 1

D

t

11 k

e

2

t

D

1

k

e

,

where

D

1

D

2

D

3

etc.

P

o

D

1

11 k

e

2

D

2

11 k

e

2

2

D

3

11 k

e

2

3

p

D

n

11 k

e

2

n

P

n

11 k

e

2

n

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 104