Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

Chapter 3 Present values and financial arithmetic 85

■

Formula for the present value of a growing perpetuity

In 1 above, we obtained:

Redefining and keeping

Multiplying both sides by and rearranging, we have:

■ The present value of annuities

The above perpetuities were special cases of the annuity formula. To find the present

value of an annuity, we can first use the perpetuity formula and deduct from it the

years outside the annuity period. For example, if an annuity of £100 is issued for 20

years at 10 per cent, we would find the present value of a perpetuity of £100 using the

formula:

Next, find the present value of a perpetuity for the same amount, starting at year 20,

using the formula:

The difference will be:

The present value of an annuity of £100 for 20 years discounted at 10 per cent is

£851.36.

The formula may be simplified to:

PV of annuity X¢

1

i

1

i11 i2

t

≤

£1,000 £148.64 £851.36

PV of annuity

X

i

X

i11 i2

t

PV

X

i11 i2

t

£100

0.1011 0.102

20

£148.64

PV

X

i

100

0.10

£1,000

PV

X

i g

11 i2

PV¢1

1 g

1 i

≤

X

1 i

a X>11 i2:b 11 g2> 11 i2

PV 11 b2 a

CFAI_C03.QXD 10/26/05 11:11 AM Page 85

.

QUESTIONS

86 Part I A framework for financial decisions

QUESTIONS

Question with a

coloured number have solution in Appendix B on page 692.

1 Explain the difference between accounting profit and cash flow.

2 Calculate the present value of a ten-year annuity of £100, assuming an interest rate of 20 per cent.

3 A firm is considering the purchase of a machine which will cost £20,000. It is estimated that annual savings of

£5,000 will result from the machine’s installation, that the life of the machine will be five years, and that its

residual value will be £1,000. Assuming the required rate of return to be 10 per cent, what action would you

recommend?

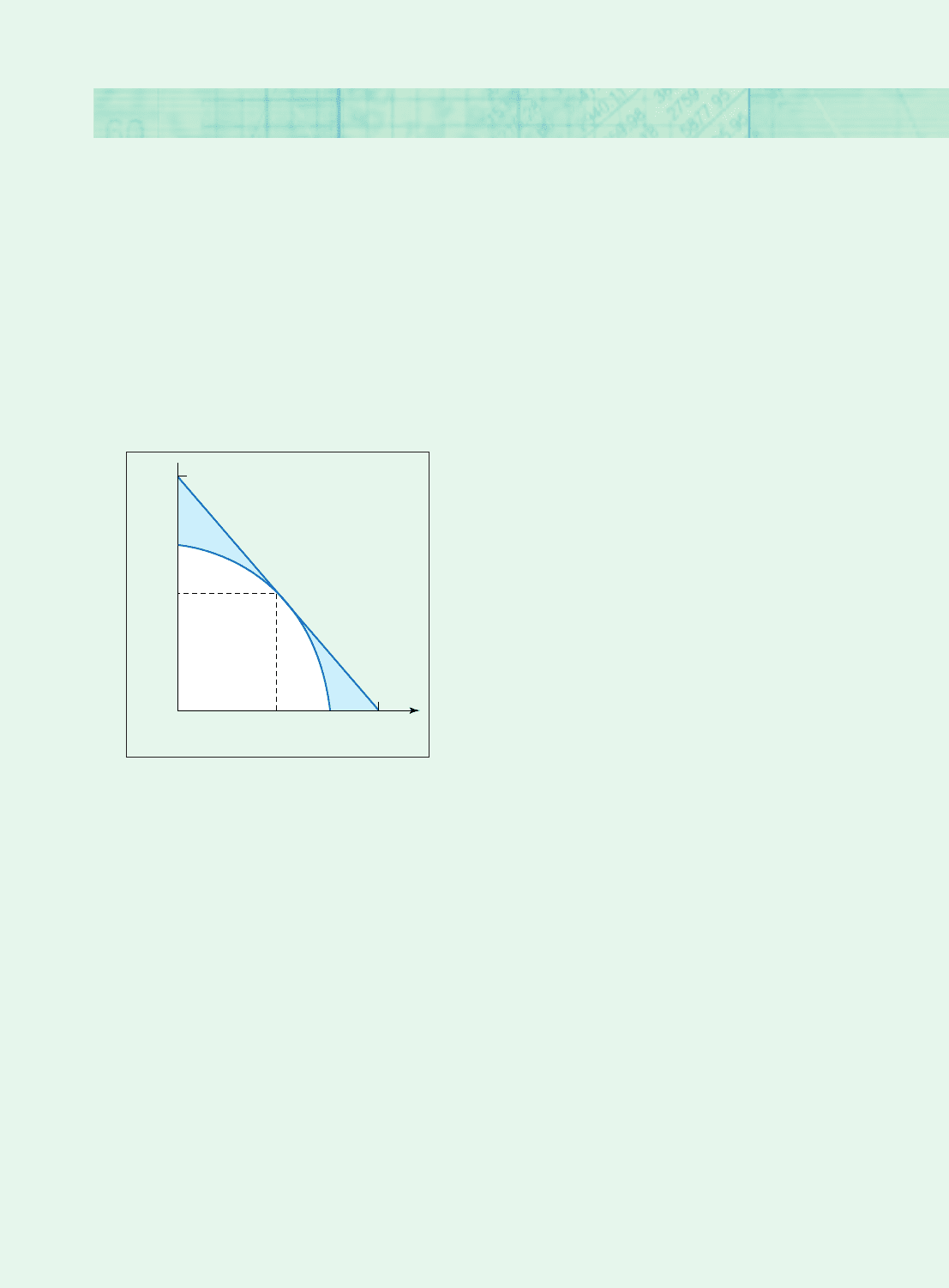

4 (Based on Appendix I to this chapter.) Ron Bratt decides to commence trading as a sportswear retailer, with

initial capital of £6,000 in cash. The capital market and investment opportunities available are shown below:

0468

Now (£000)

Year 1 (£000)

7

10

5

You are required to calculate:

(a) How much the firm should invest in real assets.

(b) The market rate of interest for the business.

(c) The average rate of return on investment.

(d) The net present value of the investment.

(e) The value of the firm after this level of investment.

(f) Next year’s dividend if Bratt only requires a current dividend of £3,000.

5 The gross yield to redemption on government stocks (gilts) are as follows:

Treasury 8.5% 2000 7.00%

Exchequer 10.5% 2005 6.70%

Treasury 8% 2015 6.53%

(a) Examine the shape of the yield curve for gilts, based upon the information above, which you should use

to construct the curve.

(b) Explain the meaning of the term ‘gilts’ and the relevance of yield curves to the private investor.

CFAI_C03.QXD 10/26/05 11:11 AM Page 86

.

6 Calculate the net present value of projects A and B, assuming discount rates of 0 per cent, 10 per cent and 20

per cent.

A (£) B (£)

Initial outlay 1,200 1,200

Cash receipts:

Year 1 1,000 100

Year 2 500 600

Year 3 100 1,100

Which is the superior project at each level of discount rate? Why do they not all produce the same answer?

7 The directors of Yorkshire Autopoints are considering the acquisition of an automatic car-washing installa-

tion. The initial cost and setting-up expenses will amount to about £140,000. Its estimated life is about seven

years, and estimated annual accounting profit is as follows:

Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Operations cash flow (£) 30,000 50,000 60,000 60,000 30,000 20,000 20,000

Depreciation (£) 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000

Accounting profit (£) 10,000 30,000 40,000 40,000 10,000 – –

At the end of its seven-year life, the installation will yield only a few pounds in scrap value. The company

classifies its projects as follows:

Required rate of return

Low risk 20 per cent

Average risk 30 per cent

High risk 40 per cent

Car-washing projects are estimated to be of average risk.

(a) Should the car-wash be installed?

(b) List some of the popular errors made in assessing capital projects.

Chapter 3 Present values and financial arithmetic 87

List three decisions in a business with which you are familiar where cash flows arise over a lengthy time period

and where discounted cash flow (DCF) may be beneficial. To what extent is DCF applied (formally or intuitively)?

What are the dangers of ignoring the time-value of money in these particular cases?

Practical assignment

CFAI_C03.QXD 10/26/05 11:11 AM Page 87

.

88 Part I A framework for financial decisions

Valuation of assets, shares and companies

4

Learning objectives

The ultimate effectiveness of financial management is judged by its contribution to the value of the

enterprise. This chapter aims:

■ To provide an understanding of the main ways of valuing companies and shares, and of the limi-

tations of these methods.

■ To stress that valuation is an imprecise art, requiring a blend of theoretical analysis and practical

skills.

■ To introduce the dividend valuation model, an important underpinning of the analysis of dividend

policy in Chapter 17.

A sound grasp of the principles of valuation is essential for many other areas of financial management.

Must do better …

Provision of training courses and learning materials

for students preparing for professional accounting

exams is now big business, with a number of listed

companies involved. In June 1998, the first quoted

operator, Nord Anglia plc, acquired EW Fact, a leading

accountancy training firm, for £19 million. After the

acquisition, Nord Anglia was dismayed to find that

restructuring costs were much higher than expected.

In May 1999, Nord Anglia announced a profits warn-

ing and also that it was considering legal action against

EW Fact for ‘materially overstating’ profits for the year

before acquisition. Nord Anglia’s chairman alleged that

pre-tax profits in 1997, posted at £1.4 million, should

have been just £80,000. This knowledge would presum-

ably have affected the sum that Nord Anglia would

have paid to acquire EW Fact. Shares in Nord Anglia fell

from 230p to 187p on the announcement.

The Daily Telegraph quipped: ‘The sort of mistake

any student can make, of course. But not what should

be expected from auditors – if properly trained’.

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 88

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 89

4.1 INTRODUCTION

The concept of value is at the heart of financial management, yet the introductory case

demonstrates that valuation of companies is by no means an exact science. Inability to

make precisely accurate valuations complicates the task of financial managers.

The financial manager controls capital flows into, within and out of the enterprise

attempting to achieve maximum value for shareholders. The test of his/her effective-

ness is the extent to which these operations enhance shareholder wealth. He/she

needs a thorough understanding of the determinants of value to anticipate the conse-

quences of alternative financial decisions. If there is an active and efficient market in

the company’s shares, it should provide a reliable indication of value. However, man-

agers may feel that the market is unreliable, and may wish to undertake their own val-

uation exercises. Indeed, some managers behave as though they doubt the Efficient

Markets Hypothesis (EMH), outlined in Chapter 2.

In addition, there are specific situations where financial managers must undertake

valuations, for example, when valuing a proposed acquisition, or assessing the value

of their own company when faced with a takeover bid. Directors of unquoted compa-

nies may also need to apply valuation principles if they intend to invite a takeover

approach from a larger firm or if they decide to obtain a market quotation.

Valuation skills thus have an important strategic dimension. In order to advise on

the desirability of alternative financial strategies, the financial manager needs to assess

the value to the firm of pursuing each option. This chapter examines the major diffi-

culties in valuation and explains the main methods available.

4.2 THE VALUATION PROBLEM

Anyone who has ever attempted to buy or sell a second-hand car or house will appre-

ciate that value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Value is whatever the highest

bidder is prepared to pay. With a well-established market in the asset concerned, and if

the asset is fairly homogeneous, valuation is relatively simple. So long as the market is

reasonably efficient, the market price can be trusted as a fair assessment of value.

Problems arise in valuing unique assets, or assets that have no recognisable market,

such as the shares of most unquoted companies. Even with a ready market, valuation

may be complicated by a change of use or ownership. For example, the value of an

incompetently-managed company may be less than the same enterprise after a shake-

up by replacement managers. But by how much would value increase? Valuing the

firm under new management would require access to key financial data not readily

available to outsiders. Similarly, a conglomerate that has grown haphazardly may be

worth more when broken up and sold to the highest bidders. But who are the prospec-

tive bidders, and how much might they offer? Undoubtedly, valuation in practice

involves considerable informed guesswork. (Inside information often helps as well!)

Regarding the introductory case, we do not know how the valuation was arrived at,

but we can see that even the ‘experts’ can get it wrong. This illustrates an important

lesson – the only certain thing about a valuation is that it will be ‘wrong’! However,

this is no excuse for hand-wringing. A key question is whether the valuations were

reasonable in the light of the information then available.

The three basic valuation methods are net asset value, price–earnings multiples

and discounted cash flow. None of these is foolproof, and they often give different

answers. Moreover, different approaches may be required when valuing whole com-

panies from those appropriate to valuing part shares of companies. In addition, the

value of a whole company (i.e. the value of its entire stock of assets) may differ from

the value of the shareholders’ stake. This applies when the firm is partly financed by

debt capital.

price-earnings multiples

The price-earnings multiple, or

ratio (PER), is the ratio of earn-

ings (i.e. profit after tax) per

share (EPS) to market share

price

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 89

.

90 Part I A framework for financial decisions

■ Enterprise value vs. equity value: Innogy plc

To persuade the present owners to sell, a bidder has to offer an acceptable price for

their equity and expect to take on responsibility for the company’s debt. Consider the

purchase in 2002, by RWE Ag, the German multi-utility group of the British electrici-

ty supplier, Innogy, itself a spin-off from the privatised company, International Power.

RWE’s logic was to complement its previous acquisition of Thames Water in 2000 in

order to gain access to 10 million customer accounts to which it could offer gas, elec-

tricity and water. The overall deal was valued at around £5 billion, comprising some

£3 billion of equity and £2 billion of debt.

Innogy’s stock of assets was financed partly by equity and partly by debt. To obtain

ownership of all the assets, i.e. the whole company, RWE was obliged to offer £3 bil-

lion to the shareholders to induce them to sell, and either pay off the debt or assume

responsibility for it. Although RWE chose the latter route, either course of action made

the cost of the acquisition £5 billion.

Obviously, to make the acquisition worthwhile to RWE its own (undisclosed) valu-

ation would presumably have exceeded £5 billion. We thus encounter several differ-

ent concepts of value:

Value of company to the buyer: probably more than £5 billion

Cost to acquire company: £5 billion

Value of equity stake required to clinch sale: £3 billion

Value of equity stake perceived by owners: possibly below £3 billion

The distinction between company value and the value of the owners’ stake is clari-

fied by considering the first method of valuation, the net asset value approach, which

is based on scrutiny of company accounts.

Self-assessment activity 4.1

Using the Innogy example, distinguish between the value of a whole company and the

value of the equity stake. When would these two measures coincide?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

The Balance Sheet for DS Smith plc, the paper and packaging group, is shown in Table 4.1.

The Balance Sheet in its modern vertical form pinpoints the NAV, the net assets figure, £562.0

million, which, by definition, must coincide with shareholders’ funds, i.e. the value of the

shareholders’ stake net of all liabilities (and, in this case, net of a small minority item, i.e.

residual ownership in an acquired firm). (The book value of the whole company, i.e. its total

assets, is fixed assets plus current assets (£785.1 m £578.0 m) £1,363.1 m.) However,

4.3 VALUATION USING PUBLISHED ACCOUNTS

Using the asset value stated in the accounts has obvious appeal for those impressed by

the apparent objectivity of published accounting data. The Balance Sheet shows the

recorded value for the total of fixed assets (sometimes, but not invariably, including intan-

gible assets) and current assets, namely stocks and work-in-progress, debtors, and other

holdings of liquid assets such as cash and marketable securities. After deducting the debts

of the company, both long- and short-term, from the total asset value (i.e. the value of the

whole company) the residual figure is the net asset value (NAV), i.e. the value of net

assets or the book value of the owners’ stake in the company or, simply, ‘owners’ equity’.

net asset value approach

Calculation of the equity value

in a firm by netting the liabili-

ties against the assets

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 90

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 91

Table 4.1 Balance Sheet for DS Smith plc as at 30 April 2004

Assets employed £m £m

Fixed assets (net) 785.1

Current assets:

Stocks 154.9

Debtors 361.5

Cash and investments 61.6

Creditors falling due within one year (401.2

)

Net current assets 176.8

Total assets less current liabilities 961.9

Creditors falling due after one year (inc. provisions) (394.1)

Minority interests (5.8)

Net assets (NAV) 562.0

Financed by:

Called-up share capital 38.7

Share premium account 254.6

Profit and loss account 260.2

Revaluation reserve 8.5

Shareholders’ funds (NAV) 562.0

Source: DS Smith plc, Annual Report 2004 (www.dssmith.uk.com)

the NAV is a very unreliable indicator of value in most circumstances. Most crucially, it

derives from a valuation of the separate assets of the enterprise, although the accountant will

assert that the valuation has been made on a ‘going concern basis’, i.e. as if the bundle of

assets will continue to operate in their current use. Such a valuation often, but not invariably,

understates the earning power of the assets, particularly for profitable companies.

In July 2004, the market value of DS Smith’s equity was £596 million (share price of 154p

times number of 10p shares, i.e. 387 million). Hence, the net assets were apparently worth

rather less than the firm as a going concern with its existing and expected strategies, man-

agement and skills, all of which determine its ability to generate profits and cash flows. If

the profit potential of a company is suspect, however, then break-up value assumes greater

importance. The value of the assets in their best alternative use (e.g. selling them off) might

then exceed the market value of the business, providing a signal to the owners to disband

the enterprise and shift the resources into those alternative uses. Sometimes, then we may

be able to adjust the NAV to take into account more up-to-date, or more relevant informa-

tion, thus obtaining the Adjusted NAV.

Self-assessment activity 4.2

For DS Smith plc, identify:

(i) the value of the whole firm, i.e. enterprise value

(ii) the value of its total liabilities

(iii) the value of the owners’ equity.

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 91

.

92 Part I A framework for financial decisions

■ Problems with the NAV

The NAV, even as a measure of break-up value, may be defective for several reasons.

1 Fixed asset values are based on historical cost

Book values of fixed assets, e.g. £785.1 million for DS Smith, are expressed net of

depreciation, the result of writing down asset values over their assumed useful lives.

Depreciating an asset, however, is not an attempt to arrive at a market-oriented assess-

ment of value but an attempt to spread out the historical cost of an asset over its

expected lifetime so as to reflect the annual cost of using it. It would be an amazing

coincidence if the historical cost less accumulated depreciation were an accurate meas-

ure of the value of an asset to the owners, especially at times of generally rising prices.

Some companies try to overcome this problem by periodic valuations of assets, espe-

cially freehold property. However, few companies do this annually, and even when

they do, the resulting estimate is valid only at the stated dates. Whichever way we

look at it, fixed asset values are always out of date!

A more sophisticated approach (but thus far stoutly resisted by the accounting pro-

fession) is to adopt current cost accounting (CCA). Under CCA, assets are valued at

their replacement cost, i.e. what it would cost the firm now to obtain assets of similar

vintage. For example, if a machine cost £1 million five years ago, and asset prices

have inflated at 10 per cent p.a., the cost of a new asset would be about £1.6 million,

i.e. £1 m (1.10)

5

. The historical cost less five years’ depreciation on a straight-line

basis, and assuming a ten-year life, would be £0.5 million. However, the cost of

acquiring an asset of similar vintage would be around £0.8 million.

There are obvious problems in applying CCA. For example, estimating current cost

requires knowledge of the rate of inflation of identical assets, and of the impact of

changing technology on replacement values. Nevertheless, the replacement cost meas-

ure is often far closer to a market value than historical cost less depreciation. Ideally,

companies should revalue assets annually, but the time and costs involved are gener-

ally considered prohibitive.

Asset values may also fall. Directors are legally required to state in the annual

report if the market value of assets is materially different from book value. It is better

to ‘bite the bullet’ and actually reduce the value of poorly-performing assets in the

accounts. This was done by BT in September 2001 when it announced a charge of £500

million in its first-half results to reflect the reduced value of its disastrous 9 per cent

holding in AT&T Canada and its 20 per cent holding in Impsat of Argentina.

The highest write-off to date was the $50 billion write-down in 2003 by Worldcom

(later renamed MCI) of assets acquired during an acquisition spree, following which

several executives saw the inside of jails after convictions for false accounting. Write-offs

are, in effect, an admission that profits have been overstated in the past, (i.e.) deprecia-

tion has been too low. Firms tend to increase write-offs during difficult trading times on

the principle of unloading all the bad news in one go. In the USA, Goldman Sachs, the

merchant bank, reckoned that write-offs in 2002 rose to 140% of corporate earnings.

replacement cost

The cost of replacing the exist-

ing assets of a firm with assets

of similar vintage capable of

performing similar functions

Under the new International Reporting Standards (IFRSs), UK firms will no longer have to

depreciate goodwill (the difference between the price paid for an acquisition and the book

value of the assets acquired), but to carry out an annual ‘impairment review’, which is already

the US practice. The results of the switch to IFRSs can be remarkable. In January 2005,

Vodafone, which has grown rapidly by acquisition, revealed that its loss of £1.88 billion for

the six months ending September 2004 would have been shown as a profit of £4.5 billion

under IFRSs.

2 Stock values are often unreliable

Under Generally Accepted Accounting Practice (GAAP), stocks are valued at the lower

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 92

.

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets, shares and companies 93

of cost or net realisable value. Such a conservative figure may hide appreciation in the

value of stocks, e.g. when raw material and fuel prices are rising. Conversely, in some

activities, fashions and tastes change rapidly, and although the recorded stock value

might have been reasonably accurate at the Balance Sheet date, it may look inflated some

time later.

3 The debtors figure may be suspect

Similar comments may apply to the recorded figure for debtors. Not all debtors can be

easily converted into cash, since debtors may include an element of dubious or bad

debts, although some degree of provision is normally made for these.

The debtor collection period, supplemented by an ageing profile of outstanding

debts, should provide clues to the reliability of the debtors position.

4 A further problem: valuation of intangible assets

Even if these problems can be overcome, the resulting asset valuation is often less than

the market value of the firm. ‘People businesses’ typically have few fixed assets and

low stock levels. Based on the accounts, several leading quoted advertising agencies

and consultancies have tiny or even negative NAVs.

However, they often have substantial market values because the people they employ

are ‘assets’ whose interactions confer earning power – the quality that ultimately deter-

mines value. This may be seen most clearly in the case of professional football clubs,

few of which place a value for players on their Balance Sheets. Manchester United led

the way in this respect when it valued its players prior to flotation on the market in

1991. There are 17 quoted football companies in the Financial Times listings, fifteen

English and two Scottish. Is your club shown in Table 4.2?

Vanishing stock values (USA: stock=inventory)

In March 2000, shares in New Economy powerhouse Cisco Systems Inc. peaked at $80. Cisco,

whose remarkable growth was founded on making gear to power the internet, was now planning

to re-focus on selling equipment to new-world telecoms companies planning to supplant

‘dinosaurs’ like AT&T.

Yet its customers were beginning to complain about long lead times for products. So Cisco

entered into long-term supply contracts with suppliers and manufacturers to ensure the avail-

ability of customised components. But, already, the US economy was slowing down, reducing

demand for Cisco’s products. In April 2001, Cisco announced that sales for the current quarter

were set to drop by 30 per cent, driving the share price down to a 52-week low of $13.63.

In May 2001, Cisco announced a third quarter loss of $2.7 billion, a loss struck after a write-

down of excess stock by $2.2 billion, 70 per cent of this involving telecom gear and parts. The

amount and the timing of the write-down surprised many. Cisco’s inventory, valued at $4.1 bil-

lion for the quarter ending April 2001, was 65 per cent higher than the previous quarter’s $2.5

billion, itself up from $1.3 billion a year earlier. Over the whole year, Cisco was clearly adding

inventory that it knew it could not sell, given weak demand and rapid technological change. This

raised the issue of why it had not disclosed any similar write-downs in previous quarters. The

Cisco case clearly illustrates the folly of rapid stock-building of high-tech products based on sus-

pect demand forecasts.

Valuation of brands

However, some other companies have attempted to close the gap between economic

value and NAV by valuing certain intangible assets under their control, such as brand

names.

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 93

.

94 Part I A framework for financial decisions

The brand valuation issue came to the fore in 1988 when the Swiss confectionery and

food giant Nestlé offered to buy Rowntree, the UK chocolate manufacturer, for more than

double its then market value. This generated considerable discussion about whether and

why the market had undervalued Rowntree and perhaps other companies that had

invested heavily in brands, either via internal product development or by acquisition.

Later that year, Grand Metropolitan Hotels (now Diageo) decided to capitalise acquired

brands in their accounts, and were followed by several other owners of ‘household name’

brands, such as Rank-Hovis-McDougall, which capitalised ‘home-grown’ brands.

Decisions to enter the value of brands in Balance Sheets were partly a consequence of

the prevailing official accounting guidelines, relating to the treatment of assets acquired

at prices above book value, often termed ‘goodwill’. These guidelines enabled firms to

write off goodwill directly to reserves, thus reducing capital, rather than carrying it as

an asset to be depreciated against income in the Profit and Loss Account, as in the USA

and most European economies. UK regulations allowed companies to report higher

earnings per share, but with reduced shareholder funds, thus raising the reported return

on capital, especially for merger-active companies. Such write-offs were stopped by a

new accounting standard, FRS10, which also prevented capitalisation of ‘home-grown’

brands. (FRS 10 obliged UK firms to follow US practice by depreciating goodwill. Under

IFRSs, to be adopted by listed UK firms from 2005, acquired goodwill need only be

depreciated if there is judged to be a ‘substantial impairment’ in the value of the asset.)

Brand valuation raises the value of the intangible assets in the Balance Sheet and thus

the NAV. Some chairpeople have presented the policy as an effort to make the market

more aware of the ‘true value’ of the company. Under strong-form capital market efficien-

cy, the effect on share price would be negligible, since the market would already be aware

of the economic value of brands. However, under weaker forms of market efficiency, if

placing a Balance Sheet value on brands provides genuinely new information, it may

become an important vehicle for improving the stock market’s ability to set ‘fair’ prices.

■ Methods of brand valuation

Many methods are available for establishing the value of a brand, all of which purport

to assess the value to the firm of being able to exploit the profit potential of the brand.

1 Cost-based methods

At its simplest, the value of a brand is the historical cost incurred in creating the intan-

gible asset. However, there is no obvious correlation between expenditure on the brand

and its economic value, which derives from its future economic benefits. For example,

do failed brands on which much money has been spent have high values? Replacement

cost could be used, but it is difficult to estimate the costs of re-creating an asset without

measuring its value initially. Alternatively, one may look at the cost of maintaining the

value of the brand, including the cost of advertising and quality control. However, it is

difficult to differentiate between expenditure incurred in maintaining the value of an

asset and investment expenditure which enhances its value.

Table 4.2

Football clubs quoted on

the London Stock

Exchange

■ Aston Villa ■ Heart of Midlothian ■ Shelfield United

■ Birmingham City ■ Leeds United ■ Southampton Leisure Holdings

■ Burndene ■ Manchester United ■ Sunderland

Investments (Bolton)

■ Millwall ■ Tottenham Hotspur

■ Celtic ■ Newcastle United ■ Watford Leisure

■

Charlton Athletic

■

Preston North End

■

West Bromwich Albion

CFAI_C04.QXD 10/28/05 2:29 PM Page 94