Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

COSELLENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

609

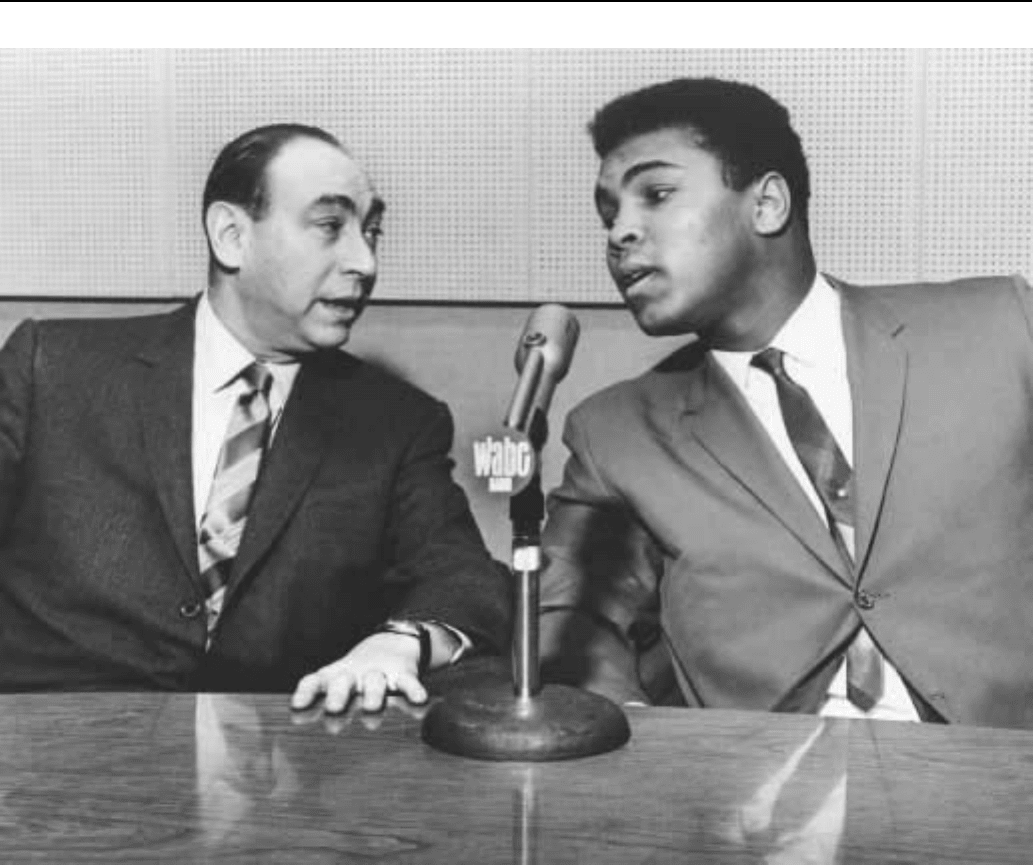

Howard Cosell (left) with Muhammad Ali

League of New York, a connection that soon landed him his first

broadcasting job. In 1953, Cosell began hosting a Saturday morn-

ing program for ABC in which kids asked sports questions of

professional athletes.

Cosell cut his teeth as a boxing commentator for ABC in the

1960s. Cosell critiqued everything in sight that would provide him

with fan appeal and approval, yet his career was most clearly tied to

the emergence of Muhammad Ali. For many viewers, Cosell’s voice

provided the soundtrack as The Greatest ‘‘floated like a butterfly and

stung like a bee.’’ The sportscaster served as one of Ali’s chief

defenders when he was stripped of his title after refusing to join the

military due to religious beliefs. Cosell’s public support was direct:

‘‘What the government did to this man was inhuman and illegal under

the Fifth and Fourteenth amendments. Nobody says a damned word

about the professional football players who dodged the draft. But

Muhammad was different; he was black and he was boastful.’’ Cosell

covered the sport of boxing until 1982. After a particularly brutal

heavyweight bout, Cosell walked away from the sport, saying:

‘‘Boxing is the only sport in the world where the clear intention is for

one person to inflict bodily harm upon the other person. . . .’’ Evi-

dently, the smooth moves of Ali had prohibited Cosell from realizing

this basic reality earlier.

In the late 1960s, ABC President Roone Arledge, who was well

known for his innovative ideas in sports broadcasting, approached

Cosell with what many observers considered a ridiculous idea: would

he like to host an evening sporting event that competed for prime-time

viewers? Cosell teamed with Don Meridith and Frank Gifford to

introduce Monday Night Football in 1970. Led by Cosell, the

program became a kind of traveling road show as fans flocked around

the broadcast booth, either to praise Cosell or damn him. Cosell’s

witty and sometimes caustic exchanges with his fellow broadcasters

often drew more attention than the games themselves. Monday Night

Football became—improbably—one of the most talked about pro-

grams of the 1970s.

Though he had a long record of support for civil rights and had

offered prominent support to the protests of black runners Tommie

Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Summer Olympics, Cosell drew

the wrath of viewers when, while watching Washington Redskin’s

COSMOPOLITAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

610

receiver Alvin Garrett carry the ball during one Monday Night

Football broadcast, he said ‘‘Look at that little monkey run.’’ Hound-

ed by critics, Cosell eventually left the broadcast booth in 1984,

claiming that pro football had become a ‘‘stagnant bore.’’ Cosell

briefly hosted a program called Sportsbeat (1985), but the publication

of his autobiography I Never Played the Game—which contained

scathing criticisms of many ABC personnel—soon led to the pro-

gram’s cancellation. Cosell broadcast intermittently on radio thereaf-

ter and retired in 1992, reportedly bitter about his exclusion from a

profession he helped to create. He died on April 23, 1995.

No matter the sport he covered, Cosell’s trademark was a steady

flow of language unmatched in the trade. He refused to simplify his

terminology, often using his nasal voice to introduce polysyllabic

words into the foreign area of the boxing ring. He left the game

description for his ex-jock colleagues, and he blazed the trail of the

commentator role that has become standard in modern broadcasting.

Arledge discussed Cosell in 1995: ‘‘He became a giant by the simple

act of telling the truth in an industry that was not used to hearing it and

considered it revolutionary.’’ This knack grew directly from what

others called an ‘‘over-blown ego.’’ When Cosell misspoke about the

game, his colleagues would call him to task. The irrepressible

Cosell would typically respond with his well-known ‘‘heh, heh,

heh’’ admission.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Barber, Red. The Broadcasters. New York, DaCapo Press, 1986.

Cosell, Howard, with Peter Bonventre. I Never Played the Game.

New York, Morrow, 1985.

Sinks, Charles. Up Close. Tarpon Springs, Artist Resource Group, 1993.

Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan magazine holds a spot as one of the most success-

ful women’s magazines of all time. In the late 1990s it boasted a

circulation of 2.4 million readers in the United States, and an

impressive 29 editions in other languages. Its distinctive, come-hither

covers seem designed more to catch a man’s eye than any potential

female newsstand browser, and inside its pages features give women

very specific advice on how to lure—and keep—a man. Yet the

Cosmopolitan ideology—revolutionary in the 1960s, fitting in per-

fectly with the liberated-women zeitgeist of the 1970s, and setting the

big-haired tone of the 1980s—was the creation of one very female

mind: Helen Gurley Brown. The author of the bestselling Sex and the

Single Girl (1962), as Cosmopolitan editor, Brown deployed her array

of self-improvement strategies into a monthly format that made her

name synonymous with the magazine and enshrined Cosmo, as it

came to be called, in popular print journalism’s hall of fame.

By tying the consciousness of the sexual revolution of the

1960s—brought about in part by the launch of the oral contraceptive

pill on the United States market in 1960—with an accessible, afford-

able magazine format, Cosmopolitan succeeded beyond anyone’s

vision. The periodical had actually been in existence since 1886 as a

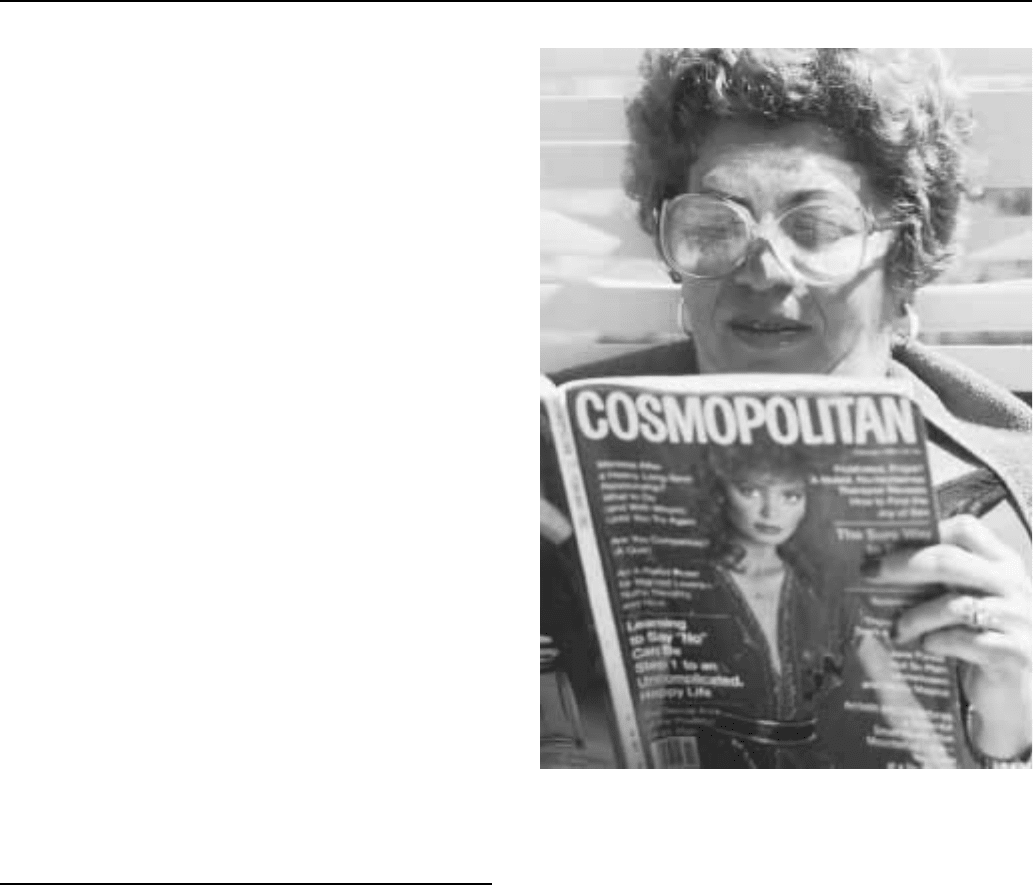

An American tourist reads Cosmopolitan while sunbathing.

general-interest literary magazine; it was a Hearst Corporation hold-

ing after 1905, and for years found success with a high-caliber output

of fiction. The ‘‘Cosmopolitan Girl’’ originally referred to the illus-

trated covers of the pre-World War II era; the term would take on an

entirely different meaning a few decades later. In the 1950s Cosmo-

politan began to focus more on attracting female readers with less

fiction and more editorial features on women’s problems. Circulation,

however, continued to plummet.

Helen Gurley Brown had already attained a certain level of

notoriety in the United States with her 1962 book Sex and the Single

Girl. The onetime advertising copywriter had penned a chatty but

frank little how-to guide for young single women aspiring to be

glamorous urban sophisticates; Sex and the Single Girl dovetailed

perfectly with the trend of a greater number of female college

graduates in the postwar boom years, a lessening of stigmas attached

to unmarried women living on their own, and a delay in the average

age of marriage. Brown posited that it was not only okay to be single,

but a happy and emotionally healthy way to live—a revolutionary

idea at the time, to say the least. The book’s tacit acknowledgment

that sex occurred regularly between single, consenting adults outside

of the bonds of matrimony was even more radical. Brown tried to find

a backer for a magazine of her own after the runaway success of Sex;

she planned to name it Femme and aim it at new young working

COSMOPOLITANENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

611

women. Instead Hearst hired her to revamp the moribund Cosmopoli-

tan, which was near death at the time. With almost no journalism

experience Brown became its first female editor.

The first revamped Cosmo in July of 1965 launched a new era in

women’s magazines. It addressed sex in frank terms and gave readers

a barrage of upbeat self-improvement tips for sex, work, and the

physical self. Naomi Wolf, author of The Beauty Myth, termed

Cosmopolitan the first of ‘‘the new wave of post-women’s movement

magazines’’ that depicted women as sexual beings. Compared to its

predecessors among women’s service magazines, Cosmopolitan,

wrote Wolf, set forth ‘‘an aspiration, individualist, can-do tone that

says that you should be your best and nothing should get in your

way.... But the formula must also include an element that contra-

dicts and then undermines the overall prowoman fare’’ with anxiety-

proving articles about cellulite, breast size, and wrinkles.

Brown always focused her magazine’s editorial slant on the

reader she termed ‘‘the mouseburger.’’ Clearly a self-referential term,

Brown defined it for Glenn Collins of the New York Times in 1982:

‘‘A mouseburger is a young woman who is not very prepossessing,’’

Brown said. ‘‘She is not beautiful. She is poor, has no family

connections, and she is not a razzle-dazzle ball of charm and fire. She

is a kind of waif.’’ With a heavy editorial emphasis on sex and dating

features, tell-all stories, and beauty and diet tips, Cosmopolitan had

become an American institution by the 1970s, and the term ‘‘Cosmo

Girl’’ seemed synonymous with the ultra-liberated woman in her

twenties who had several ‘‘beaus,’’ a well-paying job, and a hedonis-

tic lifestyle. The magazine also introduced the male centerfold with a

much-publicized spread of actor Burt Reynolds in its April 1972 issue.

Yet the reality was somewhat different: Cosmopolitan’s

demographics were rooted in the lower income brackets, attracting

readers with little college education who held low-paying, usually

clerical jobs. The ‘‘Cosmo Girl’’ on the cover and the few vampy

fashion pages inside reflected this—the Cosmo style was far different

from the more restrained, elegant, or avant-garde look of its journalis-

tic sisters like Vogue or even Mademoiselle, which focused on a more

middle class readership. Though often a top model or celebrity, the

women on Cosmo’s covers were usually shown in half-or three-

quarter-length body shots, often by Francesco Scavullo for several

years, to show off the low-cut evening wear. The hair was far more

overdone—read ‘‘big’’—than usual for women’s magazines, and

skimpy beaded gowns alternated with lamé and halter tops, a distinct-

ly downmarket style. The requisite ‘‘bedroom eyes’’ and pouty

mouth completed the ‘‘Cosmo Girl’’ cover shot.

Framing the cover model were teasing blurbs written by Brown’s

husband, a film producer, such as ‘‘You’ve Cheated. Do You Ever

Tell?’’ Blurbs also trumpeted the pull-out ‘‘Bedside Astrology Guide,’’

an annual feature, and articles like ‘‘How to Close the Deal’’—how to

get your boyfriend to agree to marriage. ‘‘Irma Kurtz’s Agony

Column’’ placated readers with true-life write-in questions and

answers from readers with often outrageous personal problems borne

of their own bad decisions. ‘‘The magazine allows women the

impression of a pseudo-sexual liberation and a vicarious participation

in the life of an imaginary ‘swinging single’ woman,’’ wrote Ellen

McCracken in her book Decoding Women’s Magazines. ‘‘Although

most readers will never dress or behave as the magazine urges,

Cosmopolitan offers them momentary opportunity to transgress the

predominant sexual mores in the privacy of their homes.’’

By 1981 Cosmopolitan’s circulation had quadruped its 1965

figures. Brown never seemed surprised that her magazine had suc-

ceeded so well. As she told Roxanne Roberts in the Washington Post,

‘‘Cosmo really is this basic message: Just do what’s there every day,

and one thing will finally lead to another and you’ll get to be

somebody.... I believe most 20-year-old women think they’re not

pretty enough, smart enough, they don’t have enough sex appeal, they

don’t have the job they want, they’ve still got some problems with

their family,’’ Brown told Roberts. ‘‘All that raw material is there to

be turned into something wonderful. I just think of my life. If I can do

it, anybody can.’’

For 16 years the magazine, under Brown’s editorship, was one of

the Hearst chain’s top performers. At one point in the 1980s it had the

highest number of advertising pages of all women’s magazines in the

United States. Most of the copies—about 2.5 million—were pur-

chased at the newsstand, an impulse buy and thus more profitable for

Hearst than the discounted subscription price, and its ‘‘pass-around’’

rate was also much higher than its competition.

Not surprisingly, Cosmopolitan has always been a particular

target of feminist ire. As early as 1970 it appeared in the Appendix of

the classic tome Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings

from the Women’s Liberation Movement on the ‘‘Drop Dead List.’’

But Brown defended her magazine in the 1982 interview with Collins

of the New York Times. ‘‘Cosmo predated the women’s movement,

and I have always said my message is for the woman who loves men

but who doesn’t want to live through them.... I sometimes think

feminists don’t read what I write. I am for total equality. My relevance

is that I deal with reality.’’ The reality was that sometimes women did

sleep with their bosses, or date married men, or use psychological

ruses to maintain a relationship or force a marriage, and Cosmopoli-

tan was one of the few women’s magazines to write about such issues

in non-judgmental terms. It was criticized, however, for failing to

address safe-sex issues after the advent of AIDS (Acquired Immune

Deficiency Syndrome) in the 1980s.

Helen Gurley Brown retired in 1997 after an interim joint-

editorship with the launch editor of Marie Claire, Bonnie Fuller. A

Cosmopolitan-ized version of the French original, Marie Claire is the

closest American offering on the newsstands to Cosmopolitan, but

features a more sophisticated, Elle-type fashion slant. ‘‘The Hearst

move was about acknowledging change,’’ noted Mediaweek’s Barba-

ra Lippert, describing Brown as almost a relic from a quainter, more

innocent age. ‘‘These days, however, everybody’s negotiating a new,

much more complicated set of questions than how to land a man . . .

the whole Little Miss Secretary Achiever thing is anathema to some

twentysomethings, who are more interested in cybersex and the single

girl,’’ Lippert wrote. Both the age and the income level of Cosmopoli-

tan’s average American reader had climbed somewhat, and a higher

percentage of married women now read it. By the time of Brown’s

retirement, Cosmopolitan was an international phenomenon, with 29

editions in several different languages. The 1960s-era themes of

sexual liberation seemed to catch on most successfully in the newly

‘‘de-Communized’’ countries of the Eastern Bloc, where equal rights

for women had once been a hallmark of their legal, social, and

economic systems. ‘‘Think of it,’’ wrote the Washington Post’s

Roberts. ‘‘Cosmo girls everywhere. Like McDonald’s with cleavage.’’

—Carol Brennan

F

URTHER READING:

Collins, Glenn. ‘‘At 60, Helen Gurley Brown Talks about Life and

Love.’’ New York Times. September 19, 1982, 68.

COSTAS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

612

‘‘Cosmopolitan.’’ In American Mass-Market Magazines, edited by

Alan Nourie and Barbara Nourie. Westport, Connecticut, Green-

wood Press, 1990.

‘‘Cosmopolitan.’’ In Women’s Periodicals in the United States:

Consumer Magazines, edited by Kathleen T. Endress and Therese

L. Lueck. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 311-317.

Ferguson, Marjorie. ‘‘Cosmopolitan: The Cross-Cultural Cult Mes-

sage.’’ Forever Feminine. London, Heinemann, 1982.

Lippert, Barbara. ‘‘Gurley Show.’’ Mediaweek. March 4, 1996, MR40.

McCracken, Ellen. ‘‘Cosmopolitan: Pseudo-liberation, Vicarious

Eroticism, and Traditional Moral Values.’’ In Decoding Women’s

Magazines: From Mademoiselle to Ms. New York, St. Martin’s

Press, 1993.

Roberts, Roxanne. ‘‘The Oldest Living Cosmo Girl.’’ Washington

Post. January 31, 1996, D1.

Costas, Bob (1952—)

Preeminent broadcast journalist and sportscaster Bob Costas

began announcing basketball games for a St. Louis radio station at the

age of twenty-two. He joined NBC in 1980, quickly becoming one of

the network’s most valuable assets through his work covering major

league baseball, football, basketball, and college events, and hosting

various shows including NBA Showtime, NFL Live, and Costas Coast

to Coast. In 1992, a high-profile stint as the network’s prime-time

anchor at the XXV Olympics in Barcelona, Spain, earned him

nationwide name recognition. A three-time Emmy winner for his

sports announcing and hosting, his colleagues have also named him

outstanding sportscaster of the year four times. Moving beyond sports

in 1988, he launched a late-night interview television program, Later

with Bob Costas, that won him another Emmy. When the series ended

in 1994, Costas expanded his duties at NBC, contributing to Dateline,

Today, NBC News, and anchoring MSNBC’s Internight.

—Courtney Bennett

F

URTHER READING:

Costas, Bob. Bob Costas: Costas on Sports. New York, Bantam

Doubleday Dell, 1997.

Smith, Curt. The Story Tellers: From Mel Allen to Bob Costas, Sixty

Years of Baseball Tales from the Broadcast Booth. New York,

Macmillan, 1995.

Costello, Elvis (1955—)

Born Declan Patrick Aloysius McManus, British singer, guitar-

ist, and composer Elvis Costello has been a mainstay of the popular

music scene since his 1977 debut disc, My Aim Is True. The son of a

jazz bandleader, Costello rode to prominence on the initial wave of

British punk—and thanks in part to a stage persona that made obvious

reference to Buddy Holly. A gifted lyricist with a flair for wordplay,

he did his best work in collaboration with the Attractions, a virtuoso

backing band anchored by Bruce Thomas (bass), Pete Thomas

(drums), and Steve Nieve (keyboards). The band’s early records,

polished to a metallic sheen by producer Nick Lowe, combined

Beatlesque pop smarts with an appreciation for American soul. The

best of these are This Year’s Model, Armed Forces, and Trust.

Costello escaped from Lowe’s clutches to record what is considered

his masterwork, 1982’s lyrically bruising, intricately textured

Imperial Bedroom.

—Robert E. Schnakenberg

F

URTHER READING:

Hinton, Brian. Elvis Costello: Let Them All Talk. London, Sanctuary

Publishing, 1998.

Thomas, Bruce. The Big Wheel. New York, Faber & Faber, 1991.

Costner, Kevin (1955—)

Kevin Costner has as many fans as detractors; he is a steadfast

box-office attraction but must strive for artistic respectability with

each new film. Seen as the sexy embodiment of a healthy, positive

image of American masculinity at the peak of his career in the early

1990s, Costner’s public persona has suffered since then from his

failure to live up to the standards set by his predecessors, the male

stars of Hollywood’s glamorous past. Because of his role as the

dreamer who, guided by a mysterious voice, builds a baseball field in

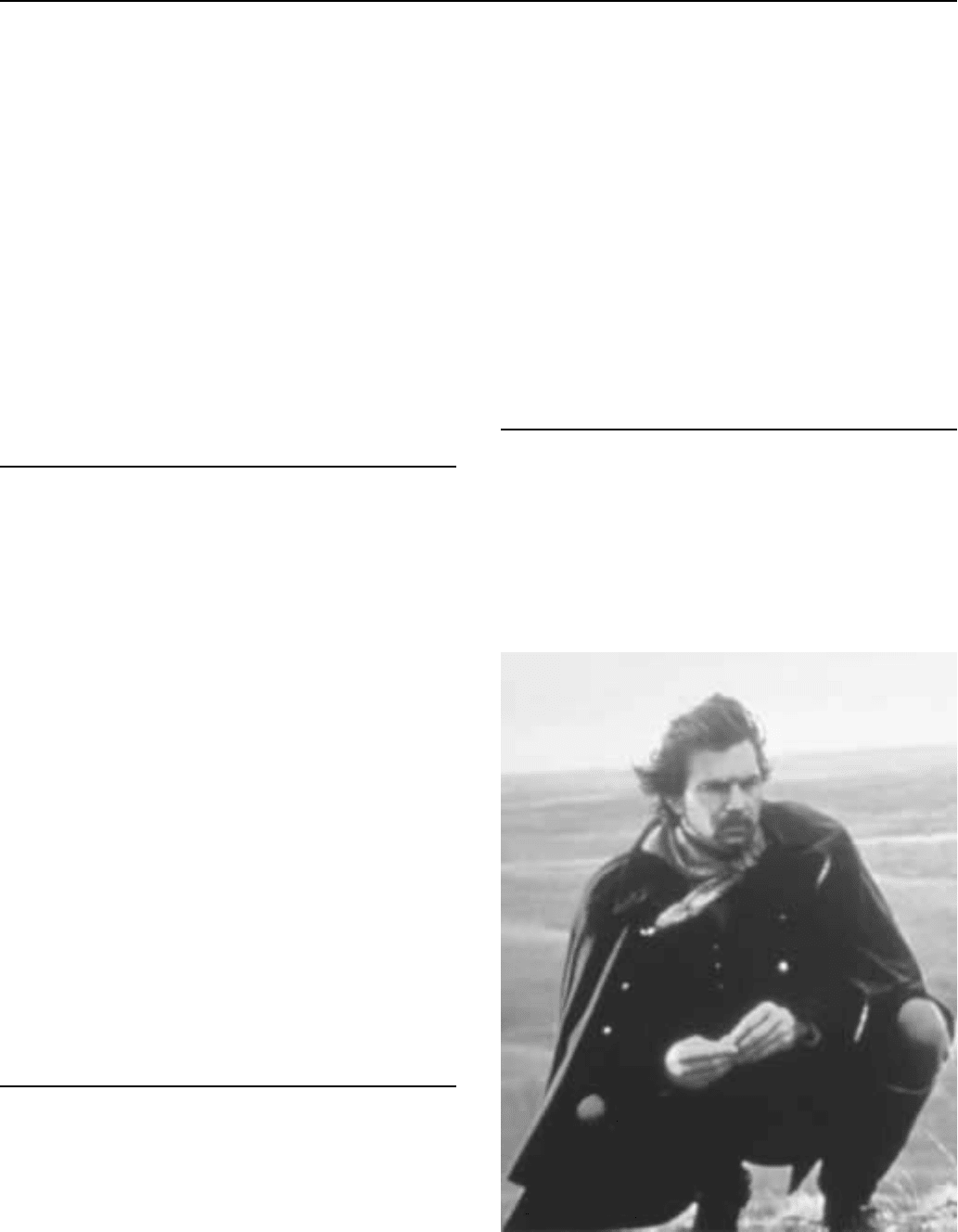

Kevin Costner in a scene from the film Dances with Wolves.

COTTENENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

613

the middle of his cornfield in Field of Dreams (1989), Costner was

compared, above all, to the Jimmy Stewart of Frank Capra’s films.

This and other allusions to Gary Cooper, prompted by Costner’s

similar handsome looks, possibly traced a path for him in the

audience’s and the critics’ imagination very unlike the one Costner

actually would follow. This divergence may explain why he is not

unanimously greeted as one of the greatest Hollywood stars of

the 1990s.

Three main aspects contribute to shaping Costner’s uneven

career. First, his rather unwise choice of roles, alternating between

less popular high quality products like JFK (1991) or A Perfect World

(1993)—in which he plays demanding roles—with impossible block-

busters like The Bodyguard (1992). Second, his irregular work as

director, which includes a hit like Dances with Wolves (1990) and a

flop like The Postman (1997). And third, the loss of his reputation as

the long-married perfect husband in favor of a less popular reputation

as a womanizer developed shortly after reaching stardom, which

clearly affected his star image. The man destined to represent Ameri-

ca’s most cherished virtues on the screen has turned out to be a star

with little sense of his own limitations as an actor, director, or public

figure and with, arguably, an excessive sense of his own value as

an artist.

Costner became a rising star with Silverado (1985) and The

Untouchables (1987). Stardom definitively came thanks to two

baseball films, Bull Durham (1988) and Field of Dreams. Games are

indeed a leit-motif in Costner’s career, which includes two more

sports-related films, Tin Cup (1996) and For the Love of the Game

(1999). The success of his excellent performance in Field of Dreams

prompted Costner to fulfill a long-cherished ambition: directing a

film, the low-budget Western epic Dances with Wolves based on the

novel by Michael Blake. Despite the misgivings of many who thought

(even wished) that Costner’s film would be an utter failure, this long

film well deserves the awards (Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director

and Best Adapted Screenplay) and the popular esteem it reaped, for it

is a courageous attempt to instill new life into the dying western

genre. Unlike typical westerns, Costner’s film deals with the confron-

tation between the white man and the native American from a

distinctly antiracist perspective, allowing the language of the native

tribes to be heard as was never heard before in cinema. Nonetheless,

the film still fails to shift the focus away from the white man—

Costner himself plays the main role—and onto the native American.

The paradox is that instead of consolidating Costner’s career, the

Oscar seems rather to have disrupted it. His role in his friend Kevin

Reynold’s Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves (1991) earned him little

sympathy, while his decision to play the pathetic killer in Clint

Eastwood’s A Perfect World—possibly his best performance to

date—was ill-timed, following hot on the heels of his very popular but

insubstantial role as Whitney Houston’s bodyguard. The Bodyguard

has, though, the redeeming merit of depicting an interracial romantic

relationship under a positive light, which might explain its popularity.

But the two films that have clearly become a sign of Costner’s

rising megalomania and self-indulgence—at least for his detractors—

are Waterworld (1995) and The Postman. The former, which he co-

directed with Kevin Reynolds, was in its time the most expensive film

ever made but it failed to generate enough box-office receipts to

recoup the impressive investment. Those who ridiculed Costner’s

wish to film Dances with Wolves but were silenced by the Oscars the

film won seemingly came back with a vengeance to prey on Waterworld.

The film broke records eliciting the highest number of negative

comment even before actual shooting began. Although it did not

become the success Costner expected, Waterworld nonetheless at-

tracted a much larger audience than the critics foretold. Yet, far from

learning a lesson from this expensive experiment, Costner plunged

next into depths he had not known for years. The Postman, Costner’s

second film as director, simply flopped, despite the good reputation of

the novel by David Brin from which it was adapted.

Costner’s case is, arguably, paradigmatic of the advantages and

the disadvantages that the current system of Hollywood film produc-

tion offers to today’s stars. In the past, Costner’s good looks and

acting talent would have guaranteed for him a stable place in the sun

of any of the main studios. He would have had to sacrifice personal

choice to stardom, with all the loss of artistic freedom that this entails.

But, in his case, the freedom of choice enjoyed by today’s stars seems

to be working against him. Other male stars like Arnold Schwarzenegger

or Mel Gibson, clearly (and paradoxically) enjoy a steady popularity

despite their occasional mistakes. Costner does not. The key to the

different treatment Costner meets might well have to do with his

reluctance to distance himself from his own star image—in short, to

his inability to laugh at his mistakes. The integrity that he exuded in

Field of Dreams or The Untouchables has been subtly transformed

into self-centeredness and this is a fault on which his detractors thrive.

Fortunately for him, his achievement in Dances with Wolves shows

that this perceived shortcoming could be forgiven in an artist.

—Sara Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Brown, C. ‘‘‘Water’ Torture.’’ Premiere. August 1995, 66-71.

Caddies, Kelvin. Kevin Costner: Prince of Hollywood. London,

Plexus, 1995.

Costner, Kevin, et al. Dances with Wolves: The Illustrated Screenplay

and Story Behind the Film. New York, Newmarket Press, 1991.

Davis, S. O. ‘‘Kevin Costner: Myth or Man?’’ Ladies’ Home Journal.

April 1991, 138-139.

Klein, E. ‘‘Costner in Control.’’ Vanity Fair. January 1992, 72-77.

Vollers, M. ‘‘Costner’s Last Stand.’’ Squire. June 1996, 100-107.

Cotten, Joseph (1905-1994)

One of Hollywood’s most versatile actors, Joseph Cotten is

chiefly associated with the films of Orson Welles. Cotten was a

latecomer to Hollywood, arriving at age thirty-six after acting on

Broadway in Welles’s Mercury Theatre. In 1940, Cotten made his

first film—Welles’s Citizen Kane—a film that would come to be

regarded as the greatest film ever made. For the remainder of the

decade, it seemed as if the talented actor could not turn in a bad

performance. Although Cotten continued to work with Welles—

starring in Journey into Fear and The Magnificent Ambersons—many

A-list directors clamored to work with the versatile star. Cotten

appeared in such classics as George Cukor’s Gaslight, Carol Reed’s

The Third Man, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt. With his

offbeat good looks and exceptional acting ability, Cotten soon evolved

into one of Hollywood’s most sought-after leading men, appearing

opposite such top stars as Ingrid Bergman, Jennifer Jones, Loretta

Young, and Joan Fontaine. Although his career continued well into

the 1980s, the good parts were fewer and farther between. Through

COTTON CLUB ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

614

his association with Welles, however, his movie immortality

remains assured.

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Callow, Simon. Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu. New York,

Viking, 1995.

Cotten, Joseph. Joseph Cotten: An Autobiography. New York, Avon

Books, 1987.

Leaming, Barbara. Orson Welles: A Biography. New York, Viking

Press, 1985.

The Cotton Club

Founded by the British-born gangster Owney Madden, the

Cotton Club nightclub opened its doors on December 4, 1923, at a

time when the black cultural revival known as the Harlem Renais-

sance was going into full swing. The club provided entertainment for

white New Yorkers who wanted to go to Harlem but were afraid of its

more dangerous aspects. The Cotton Club has never been surpassed

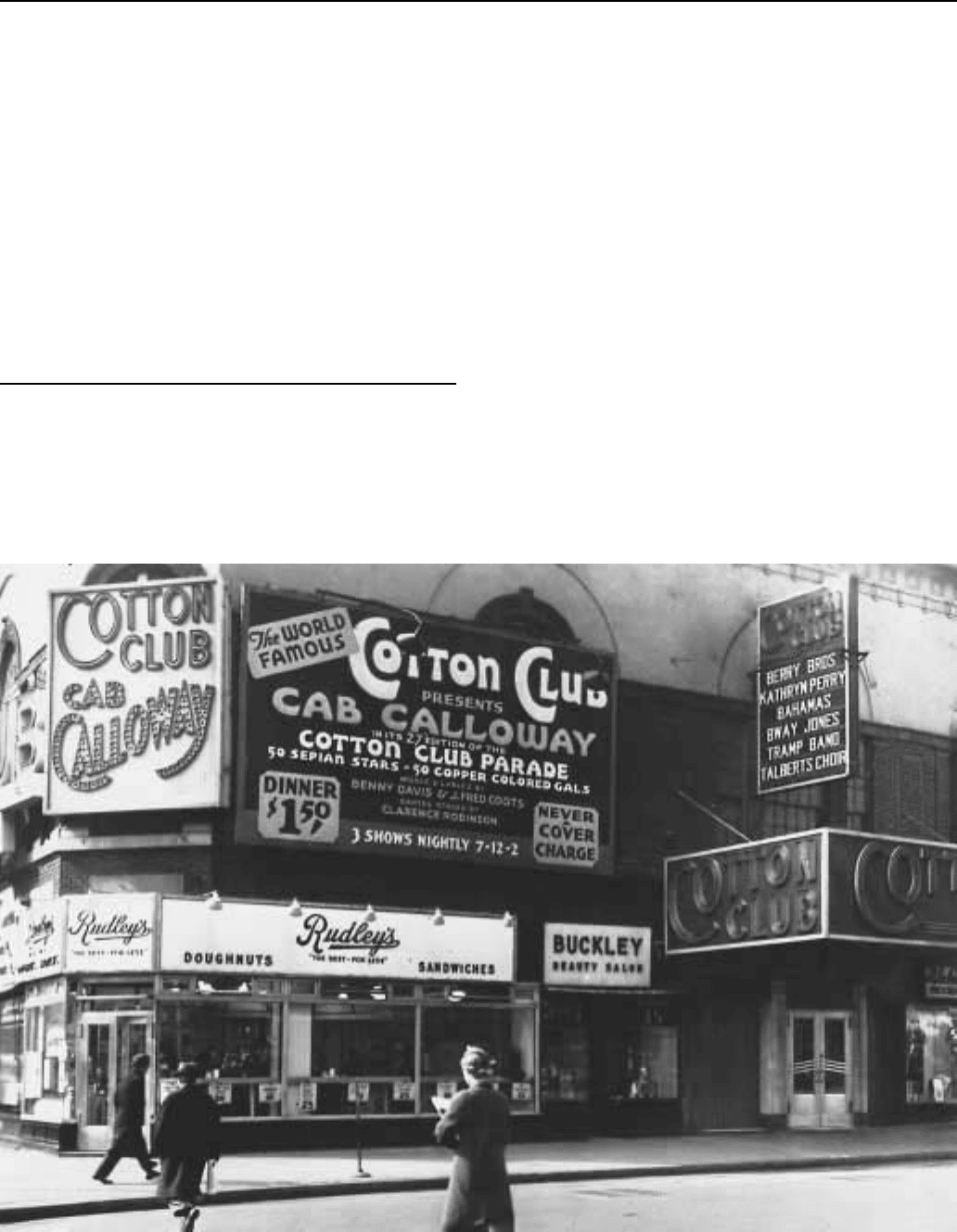

The Cotton Club

as Harlem’s most outrageous club and its lavish entertainment is still a

matter of awe even in this day of Las Vegas excess. The Cotton Club

presented the best in black entertainment to an exclusively white

audience and became famous for its use of light skinned, or ‘‘cotton

colored,’’ black women in its chorus line.

Madden opened the club to provide an outlet for his bootleg beer.

The club floor was in a horseshoe shape, designed by Joseph Urban. It

was decorated with palm trees and other jungle elements. There were

two tiers of tables and a ring of banquettes. The menu offered not only

Southern food but also elaborate European specialties. Prices were

the highest in Harlem but the food was not particularly memorable.

The entertainment, however, was spectacular. Black waiters provided

an elegant setting with their sophisticated demeanor, a contrast to the

whirling servers in neighboring clubs. These waiters also informed

patrons that it was not fashionable to put their bottles of beer on the

floor. Rather they were instructed to place them in their pockets.

Failure to comply led to ejection.

Cotton Club entertainment, or floor shows, lasted as long as two

hours. There was a featured act and the gorgeous Cotton Club chorus

line. The girls were beautiful and uniformly light skinned; they were

also young—under 21—and tall—five-foot six inches or more. Cab

Calloway’s songs ‘‘She’s Tall, She’s Tan and She’s Terrific’’ and

‘‘Cotton Colored Gal of Mine’’ are apt reflections of the girls in the

COUÉENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

615

line. The shows were fast-paced and featured the greatest black

entertainment possible. Ethel Waters, Adelaide Hall, Duke Ellington,

Cab Calloway, and others performed there.

The Cotton Club was part of the area of Harlem known as

‘‘Jungle Alley.’’ This strip, located on 133rd Street between Lenox

and Seventh Avenues, was densely packed with clubs. The Cotton

Club was one of eleven clubs in the area, most of which served a white

trade. The Cotton Club, Connie’s Inn, and Small’s Paradise were the

most renowned.

The color line was strictly enforced at the Cotton Club, and

performers and audience were kept separate. White mobsters owned

the club, its shows were written by whites (Dorothy Fields was a

major contributor), and the audience was all white. Black performers

often went next door to drink or smoke marijuana. The only African

Americans officially allowed in the Cotton Club were its outstanding

performers. On December 4, 1927, Duke Ellington began his run at

the Cotton Club, one of the more important engagements in jazz

history. The run lasted into 1932, with breaks for movies and tours

allowed. In addition to playing his music regularly, writing for the

shows, and providing a basic income to keep his men together, the gig

provided Ellington with a large radio audience who came to know his

music. At this time, Ellington developed what he termed his ‘‘jungle

sound,’’ a use of various tonal colors that he associated with Africa, a

constant theme in his ever-evolving music. He debuted ‘‘It Don’t

Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)’’ and ‘‘Mood Indigo’’ to

Cotton Club audiences.

The Cotton Club of the late 1920s and 1930s helped to define the

emergence of African-American culture in the period, coinciding as it

did with the Marcus Garvey movement, W. E. B. DuBois’s Pan

African Movement, and the flowering of African American literature

known as the Harlem Renaissance. The Cotton Club of this era has

since been memorialized in E. L. Doctorow’s historical novel Billy

Bathgate (1989) and in the Francis Ford Coppola movie The Cotton

Club (1984).

—Frank A. Salamone

F

URTHER READING:

Haskins, Jim. The Cotton Club. New York, New American Li-

brary, 1977.

Kennedy, William, and Francis Ford Coppola. The Cotton Club

(screenplay). New York, St. Martins’s Press, 1986.

Mayer, Clarence. The Cotton Club: New Poems. Detroit, Broadside

Press, 1972.

Coué, Emile (1857-1926)

A French provincial pharmacist, Emile Coué was responsible for

a therapeutic mind-over-matter system of ‘‘autosuggestion’’ known

as Couéism that influenced the popular culture of the United States

when, as in England, it became something of a national craze during

the early 1920s. By daily repetition of its still familiar mantra, ‘‘Day

by day, in every way, I am getting better and better,’’ Couéism’s

adherents hoped to achieve health and success by positive thinking

and the expectation of beneficial results. The most succinct definition

of Couéism was perhaps Coué’s own: ‘‘Couéism is an especial

Emile Coué

technique . . . for the teaching and application of auto- and other

methodical suggestion. It is more: it is an attitude of mind directed

toward progressive improvement.’’

Coué was born of old noble Breton stock in Troyes, France, and

attended pharmacy school in Paris before establishing an apothecary

in his home town. Observing that he could effect positive results in his

clients by encouragement as well as medication, he developed an

informal counseling service that became the foundation of his later

work. Moving to Nancy in 1896, he came across an advertisement

touting hypnotism as a tool for business success. His investigations in

this field led him to develop his own system, though he always

insisted that positive thinking—not hypnotic trance—was the basis of

Couéism, and that he was merely harnessing imagination in the

service of will. In 1913 he founded the Lorraine Society of Applied

Psychology and, in 1922, the Coué Institute for Psychical Education

at Paris. During World War I, he lectured in Paris and Switzerland,

with proceeds used for the relief of war victims.

His book Self-Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion caused

a sensation when it was published in England and the United States, in

1920 and 1922, respectively. A steady stream of British pilgrims to

Nancy turned Coué’s facilities into a kind of secular Lourdes,

especially after such luminaries as Julian Huxley and Sir Alfred

Downing Fripp, the King’s physician, endorsed the method. Emile

Coué: The Man and His Work, a 1935 book by J. Louis Orton, a

disaffected ex-associate, quotes Huxley: ‘‘He [Coué] goes further

than any of the orthodox medical men in his claims for the power of

mind over body; he effects remarkable cures, and finally he sums up

his ideas in one or two simple generalizations.’’

COUGHLIN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

616

Coué was invited to lecture in England regularly after 1921,

where his reputed cure of Lord Curzon’s insomnia only added to his

reputation. On January 4, 1923 he arrived in the United States for a

tumultuous lecture tour that was given substantial coverage in the

popular press, especially by the New York World. Over the next

several weeks, he gave 81 ‘‘séances’’ in major eastern cities, where

his treatment of prominent socialites such as Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt

further served to advance his cause. His appeal to American optimism

and efficiency was undoubtedly the source of much of his popularity;

industrialist Henry Ford was reported to have said, ‘‘I have read

Coué’s philosophy: he has the right idea.’’ And Coué himself was

described as the ‘‘Henry Ford of psychology’’ by Gertrude Mayo in

her 1923 book, Coué for Children. She wrote, ‘‘Just as M. Coué had

first started the engine of the subconscious mind with hypnotic

hetero-suggestion and later had substituted the self-starter of con-

scious auto-suggestion . . . thanks to him people . . . who had never

known before they possessed unconscious minds, were finding not

only that they had but that they could command them to their great

personal advantage and convenience.’’

A National Coué Institute was founded in New York to train

instructors to teach the method, and the American Library Service

began publishing his books from New York. Despite Coué’s decided-

ly secular point of view, his lectures evoked comparisons with the

faith-healing revivals that were popular at the time, attracting, in the

words of J. Louis Orton, ‘‘paralytics, asthmatics, and stammerers’’

seeking respite from their ills. Couéism came under fire from ortho-

dox religious leaders and even Christian Science—which it somewhat

resembled—for its secular viewpoint and its purported Freudianism,

which it resembled not at all. Coué returned to the United States in

1924 for an extensive lecture tour of the western states, but took ill in

England the following year after complaining his nose had been

improperly cauterized to cure his recurring nosebleeds during a

British lecture tour. He died in his homeland on July 2, 1926, and a

huge crowd attended his funeral at a Roman Catholic church. Al-

though his Institutes continued his work in Europe and the United

States, the movement quickly declined and was soon all but forgotten.

Thus the Coué craze, especially in America, ended almost as

soon as it had begun, leaving the Freudians and fundamentalists to

battle it out for the ownership of the ‘‘mind-over-matter’’ question.

The popularity of Couéism can be seen as representing a response by

mass consumer culture to the spiritual devastation of World War I,

which had spawned nihilism, Dada, socialism, and fascism in other

contexts. Its pseudoscientific, quasi-religious trappings appealed to a

disillusioned public hungry for non-material fulfillment during the

1920s, a decade that embodied the triumph of a modernistic, mecha-

nistic culture. And as an early example of how publicity, hype, and

celebrity endorsement were enlisted on behalf of non-material fulfill-

ment, Couéism presaged the work of other self-help gurus and

systems during the twentieth century, with voices as diverse as

Norman Vincent Peale, L. Ron Hubbard, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi,

and Werner Erhard perpetuating their own versions of Coué’s self-

help message.

—Edward Moran

F

URTHER READING:

Coué, Emile. My Method: Including American Impressions. Garden

City, New York, Doubleday, 1923.

———. Self-Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion. New

York, American Library Service, 1922.

Mayo, Gertrude. Coué for Children. New York, 1923.

Orton, J. Louis. Emile Coué: The Man and His Work. London, Francis

Mott, 1935.

Coughlin, Father Charles E. (1891-1979)

Long before the emergence of present-day radio ‘‘shock-jocks,’’

Father Charles E. Coughlin, the ‘‘radio priest’’ of the 1930s, realized

the power of using the airwaves as a political pulpit and means to

achieve celebrity status. Along with Huey Long, the controversial

senator from Louisiana who advocated a massive wealth-redistribution

program, Coughlin reflected the frustrations of Americans mired in a

seemingly endless Great Depression. Beginning his career as a

talented parish priest who used radio broadcasts as a means to raise

funds for his church, he became perhaps the most popular voice of

protest of his day, reaching millions of listeners each week with a

populist message that pitted the common man against the forces of the

‘‘establishment.’’ Over time his message developed from one of

protest to demagoguery; his career perhaps illustrates both the poten-

tialities and dangers of political uses of mass media.

Born in 1891 in Hamilton, Ontario, Coughlin grew up in a

devout Catholic family. There was never doubt that he would enter

the priesthood, and at the age of twelve Charles enrolled at St.

Father Charles E. Coughlin

COUNTRY MUSICENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

617

Michael’s College in Toronto. He matriculated to a seminary in 1911.

After taking the vows of priesthood, he was assigned as parish priest

in Royal Oak, Michigan, a suburban community just north of Detroit.

Although the parish was tiny and operated on a shoestring budget,

Coughlin had grandiose plans for the church—which seemed futile

considering the modest number of Catholics in Royal Oak. Two

weeks after a new church was built, local members of the Ku Klux

Klan burned a cross on the church lawn. Coughlin, known for having

a streak of militancy, vowed to overcome local resistance and

transform the struggling church into a vibrant, flourishing parish.

His plans for bolstering the church were innovative and wildly

successful. He renamed the church the Shrine of the Little Flower and

became an indefatigable fund-raiser. He invited members of the

Detroit Tigers baseball team to the church as a way to attract

attention—Babe Ruth even attended the church once while playing

the Tigers and held a basket for donations at the church door. Yet

Coughlin’s most lucrative idea was to turn to the airwaves. He

contacted the manager at local radio station WJR about broadcasting a

weekly radio sermon that would confront local issues and raise

awareness of the church. The medium was perfect for Coughlin,

whose warm, mellow voice attracted listeners throughout Detroit. His

sermons offered a variety of religious themes, such as discussions of

Christ’s teachings and Biblical parables. Soon mail was pouring into

the station, hundreds and sometimes thousands of letters each week,

most with financial contributions from listeners. Coughlin’s plans for

the Shrine of the Little Flower were soon realized: a new church was

built, with a seating capacity of more than twenty-six hundred,

complemented by a tall, granite tower. Attendance boomed as people

throughout the region came to catch a glimpse of the ‘‘radio priest.’’

Coughlin’s radio talents soon were noticed by executives outside

of Detroit. Columbia Broadcasting Service, based in New York,

offered Coughlin a deal in 1930 that gave him a national audience,

and soon he was reaching as many as forty million listeners each

week. Yet as his popularity increased, the tone and content of his

broadcasts began to change. Sermons on religious themes gave way to

discourses on politics and economics. The Great Depression, he

declared, demanded a fundamental restructuring of society in order to

overcome the evils of greed and corruption, much of which was

intrinsic to ‘‘predatory capitalism.’’ Boldly confronting his critics on

the air, Coughlin’s political speeches generated controversy, so much

so that CBS decided to cancel his show despite his growing listener base.

Undaunted, Father Coughlin signed contracts with independent

radio stations and continued to reach millions of listeners weekly. His

political messages, although impassioned, were rather vague. He

supported Franklin Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election, hailing

the New Deal as ‘‘Christ’s Deal.’’ His greatest complaint was with

wealthy financiers and bankers, most of them on the East Coast, who

were bilking the ‘‘common man.’’ With time, however, he moved

away from Roosevelt, believing that New Deal reforms were too mild

for a society that required radical change. In 1934, Coughlin founded

the National Union for Social Justice, an organization designed to

promote his political ideas, which included nationalization of Ameri-

can banks and currency inflation through the coinage of silver. Over

the next two years, the organization developed into a third party, the

Union Party, and offered William Lemke, a congressman from North

Dakota, as a presidential candidate to oppose the reelection of Roosevelt.

After the failure of the Union Party to either capture or signifi-

cantly influence the 1936 presidential election, Coughlin’s popularity

began to wane. His weekly radio broadcasts continued to attract a

national audience, but he never recaptured his earlier fame. By the late

1930s, his speeches were increasingly shrill. Listeners detected anti-

Semitism and demagoguery in his broadcasts—elements that had

appeared occasionally before, yet now were becoming more vocal

and more frequent. What had in the past, for example, been occasional

references to ‘‘Shylocks’’ and international financial conspirators

undermining the country became an outright assault against ‘‘Com-

munist Jews’’; Coughlin also borrowed from the speeches of German

Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels. He opposed American entry into

World War II vehemently, arguing that Jews had been responsible for

bringing the nation into the conflict. Such extreme positions lost for

Coughlin any significant audience that had remained with him, and he

retired from public life during the war and returned to the Shrine of the

Little Flower. He died in 1979, at the age of eighty-eight.

—Jeffrey W. Coker

F

URTHER READING:

Brinkley, Alan. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin and

the Great Depression. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1982.

Marcus, Sheldon. Father Coughlin: The Tumultuous Life of the Priest

of the Little Flower. New York, Little Brown, 1973.

Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. The Politics of Upheaval. New York,

Houghton Mifflin, 1960.

Tull, Charles J. Father Coughlin and the New Deal. Syracuse,

University of Syracuse Press, 1965.

Country Gentlemen

Founded in 1957, the Country Gentlemen were the first blue-

grass act to bridge the gap between the music’s country origins and an

urban audience. Combining singer Charlie Waller’s Louisiana roots

and mandolinist John Duffey’s urbane tastes with inspired musician-

ship, the Gentlemen rode the 1960s folk revival to prominence with a

repertoire ranging from ancient ballads to Bob Dylan songs, culmi-

nating in the 1971 release of ‘‘Fox On The Run.’’ Their version of the

number—originally a failed rock ’n’ roll single—became one of the

few bluegrass songs to achieve popular culture immortality.

—Jon Weisberger

Country Music

Country music has a history that is deeply rooted in traditional

white Southern working-class values, patriotism, conservative poli-

tics, and lyrics that tell the unblinking truth about life. An old joke

asks, ‘‘What do you get when you play a country record backwards?’’

The answer: ‘‘You get your wife back, your truck back, and your dog

back.’’ However, country music is much more than songs of hard luck

in love and life. Those lyrics that face ‘‘the cold hard facts of life,’’ in

the words of a Porter Wagoner song of the 1970s, are more than a

series of laments. They look at both success and failure, joy and

despair with sentiment and realism. And though most country music

and country music fans might advocate a straight and narrow conser-

vative path, the lyrics of country songs deal with the dilemmas of life

with a complexity not found in any other popular music.

COUNTRY MUSIC ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

618

Ricky Skaggs (middle) on stage with members of Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys at the Chicago Country Music Festival.

Country music’s earliest roots are found in the ballads of the

Appalachian Mountains, songs that stemmed from a tradition brought

to America by the English, Scots, and Irish who settled that territory.

Their religion was a strict Calvinism, and many of their songs were

dark cautionary tales of sexuality and retribution. Playwright Tennes-

see Williams, who came from that Southern Gothic tradition, put

these words in the mouth of Blanche Dubois, his most famous

heroine: ‘‘They told me to take a streetcar named Desire, then transfer

to one called Cemeteries.’’ Williams had learned the message of those

old songs: ‘‘A false-hearted lover will lead you to your grave’’ (‘‘On

Top of Old Smoky’’). One song after another told the story of

seduction followed by murder. Pretty Polly’s false lover tells her, ‘‘I

dug on your grave the best part of last night.’’ The false lover on the

banks of the Ohio admits that ‘‘I held my knife against her breast/As

into my arms she pressed.’’ In perhaps the most famous of these

songs, Tom Dooley meets his lover on the mountain and stabs her

with his knife. These dark songs were not the only part of the Southern

mountain tradition, however. There were children’s play-party songs,

danceable tunes, and upbeat, optimistic songs. But the murder songs

were so striking, coming as they did out of a tradition of sexual repres-

sion combined with stark realism, that they are the most memorable.

The music of the Southern mountains became something more

in 1927, when Ralph Peer, a recording engineer for the Victor Talking

Machine Co. (later RCA Victor), went to Bristol, Tennessee, to make

some regional recordings of what was then called ‘‘hillbilly music.’’

He sent out word that he would pay $50 for every song he recorded,

and came away with the first recorded country music.

Peer recorded two memorable acts. The first was the Carter

Family (A. P., Sara, and Maybelle Carter), whose songs included

both the anthems of optimism (‘‘Keep on the Sunny Side’’) and the

ballads of sex and death (‘‘Bury Me beneath the Willow’’). In those

recordings, still in print and still considered classics of American

music, the Carter Family created an archetype of country music. From

their harmonies to their guitar styles to their plain-spoken emotional

directness, they created a template for the music that followed them.

Second, and even more important, was Jimmie Rodgers, a one-

time railroad man (on his records he was known as ‘‘the Singing

Brakeman’’) who had taken to playing music after ill health had

forced him off the railroad. When Rodgers showed up for his first

session with Peer, he sang popular songs of the day, which earned him

no more than a rebuke. Peer was interested in recording folk singers,

singing their indigenous music, and he told Rodgers to come back

with some traditional folk songs. Rodgers did not know any tradition-

al music, but he needed the few dollars that Peer was offering for the

session. With the help of his sister, Elsie McWilliams, Rogers wrote

his own ‘‘traditional’’ tunes, hoping that Peer wouldn’t notice the

difference. The songs they created made music history.

Rodgers’ songs struck a chord with rural America. He glorified

and romanticized the day-to-day issues of small-town working peo-

ple—family, sweetheart, the struggles of the hoboes and the working

class—and he placed these issues forever in the lexicon of country

music. More importantly, Rodgers introduced the blues to country

music. His first big hit, ‘‘T For Texas (The Blue Yodel),’’ created the

Jimmie Rodgers sound—a traditional twelve bar blues, ending in a

yodel. Rodgers was so steeped in the blues that Louis Armstrong

played on one of his blue yodels, and his blues-based style was one of

the first important melds of black and white styles in American

popular music.

The blues had taken the country by storm in the 1920s, first in the

urban, jazz-inflected recordings of artists like Bessie Smith, and then

in the rural, country blues recordings of Charley Patton, Blind Lemon

Jefferson, and others. The surprise commercial success of phono-

graph records aimed at a rural black audience encouraged companies

like Victor to make a similar pitch to rural whites. The same success