Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CREDIT CARDSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

629

economic growth of the post-World War II era, which saw the United

States realize the potential for becoming a true consumption-based

society. Credit card companies competed with each other to get their

cards in the hands of consumers. With direct mail solicitations,

televisions advertisements, and the ubiquitious placement of credit

applications, these companies reached out to every segment of the

consumer market. Affluent Americans were flooded with credit card

offers at low interest rates, but poorer Americans were also offered

credit, albeit with high interest rates, low credit lines, and annual fees.

As the cards filled the wallets and purses of more and more consum-

ers, the credit card became the essential tool of the consumer society.

At the same time the competition for the consumer heated up at the

retail end. First to differentiate themselves from and then to keep up

with competitors, more and more retailers, businesses, and services

began accepting the cards.

By the 1990s, just 50 years after the birth of the modern credit

card, there were more than 450 million credit cards in the United

States—about 1.7 cards for each woman, man, and child. Moreover,

more than 3 billion offers of credit cards are made annually. VISA

administered about 50 percent of the credit cards in circulation.

MasterCard had 35 percent, the Discover Card 10 percent, and

American Express 5 percent.

The amount of money channeled through credit cards is stagger-

ing. By the late 1990s, about 820 billion dollars were charged

annually—approximately $11,000 per family—and credit cards ac-

counted for $444 billion of debt. About 17 percent of disposable

income was spent making installment payments on credit card bal-

ances; the average cardholder owed approximately $150 per month.

Eight billion transactions per year involve credit cards. Simply put,

credit cards have a profound effect on the economy. To put the force

of credit cards into some perspective, in 1998 the Federal Reserve put

20 billion dollars of new money into the economy, while U.S. banks

unleashed the equivalent of 20-30 billion dollars of new money into

the same economy via new credit cards and increased spending limits.

Given the strong tie between credit card spending and the

economy, the fact that consumers have freely used credit cards to fuel

their lifestyles has been good for the country, for the stock market, and

for retirement plans. But spending is more than simply an economic

issue. Spending reflects deeper and broader social and psychological

processes. These processes may underlie the true meaning of credit

cards in American culture.

Spending money to reflect or announce one’s success is certain-

ly not a new phenomenon. Anthropologists have long reflected upon

tribal uses of possessions as symbols of prestige. In the past the

winners were the elites of the social groups from which they came.

But credit cards have leveled the playing field, affording the ‘‘com-

mon folk’’ entry into the game of conspicuous consumption. Indeed,

the use of credit cards allows people with limited incomes to convince

others that they are in the group of winners. Credit cards have thus

broken the link that once existed between the possession of goods

and success.

Money does buy wonderful things, and many derive satisfaction

from knowing that they can buy many things. Credit cards allow

consumption to happen more easily, more frequently, and more

quickly. The satisfactions achieved through consumption are not

illusory. Goods can be authentic sources of meaning for consumers.

Indeed, goods are democratic. The Mercedes the rich person drives is

the same Mercedes that the middle class person drives. Acquiring

possessions brings enjoyment, symbolizes achievement, and creates

identity. Because credit cards make all this possible, they have

become a symbolic representation of that achievement. Having a

Gold card is prestigious and means you have achieved more in life

than those with a regular card. (A Platinum card is, of course, even

better.) Credit cards are more than modes of transaction—they are

designer labels of life, and thus impart to their user a sense of status

and power. People know what these symbols mean and desire them.

The ways that people pay for their goods differ in important

social, economic, and psychological ways. Unlike cash, credit cards

promote feelings of membership and belongingness. Having and

using a credit card is a rite of passage, creating the illusion that the

credit card holder has made it as an adult and a success. Unique

designs, newsletters, rewards for use, and special deals for holders

make owners of cards feel that they are part of a unique group.

Prestige cards such as the American Express Gold Card attempt to

impress others with how much the user seems to be worth. Finally,

credit cards are promoted as being essential for self-actualization.

You have made it, card promoters announce, you deserve it, and you

shouldn’t leave home without it; luckily, it’s everywhere you want to

be, according to VISA’s advertising slogan. Self-actualized individu-

als with credit cards have the ability to express their individuality as

fully as possible.

There are, however, costly, dangerous, and frightening problems

associated with credit card use and abuse. First, credit cards act to

elevate the price of goods. Merchants who accept credit cards must

pay anywhere from 0.3 to 3 percent of the value of the transaction to

the credit card company or bank. Such costs are not absorbed by

merchants but are passed on to all other consumers (who may not own

or use credit cards) in the price of products and services. Second,

credit cards create trails of information in credit reports that reveal

much about the lives of users, from the doctors they visit to their

choice of underwear. Not only do such reports reveal to anyone

reading them information that the credit card user might not want

made available, but confusion between users can result in embarassing

and costly mistakes. Third, credit card fraud creates billions of dollars

in costs which are paid for in high fees and interest rates and,

eventually, in the price of goods. VISA estimated that these costs

amount to between 43 and 100 dollars per thousand dollars charged.

In 1997 credit card companies charged off 22 billion dollars in unpaid

bills, 60 million a day. Finally, consumers pay in direct and indirect

ways for the personal bankruptcies that credit card abuse contributes

too. In 1997 the 1.6 million families who sought counseling with debt

counselors claimed 35 billion in debt they could not pay, much of it

credit card debt. The result of these problems is the same: consumers

pay more for goods.

One of the untold stories in the history of credit cards is the

manner in which the poorer credit card holders subsidize the richer.

Payments on credit card balances (with interest rates that normally

range from 8 to 21 percent) subsidize those who use the credit card as

a convenience and pay no interest by paying their charges within the

grace period. The 50 to 60 percent of consumers who pay their

balances within the grace period have free use of this money, but they

could not do so unless others were paying the credit card companies

for their use of the money. The people who pay the highest interest

rates are, of course, the people with the lowest incomes.

In an obvious way, the convenience of using credit cards

increases the probability that consumers will spend more than they

might have otherwise. But using credit cards is also a bit like the arms

race: the more the neighbors spend, the more consumers spend to

CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

630

stay even. Such competitive spending, while a source of sport for

the wealthy, can be potentially devastating to those on more

limited incomes.

Interestingly, credit card spending may facilitate spending in a

more insidious manner. Research has shown that the facilitation

effect of credit cards is both a conscious/rational and unconscious

process. At the rational end credit cards allow easy access to money

that may only exist in the future. People spend with credit cards as a

convenience and as a means to purchase something that they do not

have the money for now but will in the near future. However, as an

unconscious determinant of spending, credit cards can irrationally

and unconsciously urge consumers to spend more, to spend more

frequently, and make spending more likely.

Credit card spending has become an essential contributor—

some would argue a causal determinant—of a good economy. Spend-

ing encourages the manufacture of more goods and the commitment

of capital, and creates tax revenues. By facilitating spending, credit

cards are thus good for the economy. Credit cards are tools of

economic expansion, even if they do bring associated costs.

In 50 years, credit cards have gone from being a mere conven-

ience to being crucial facilitators of economic transacations. Some

would have them do even more. Credit card backers promote a vision

of a cashless economy in which a single credit card consolidates all of

a person’s financial and personal information needs. And every day

consumers vote for the evolution to a cashless electronic economic

and information system by using their credit cards. Americans are

willing prisoners of and purveyors of credit cards, spending with

credit cards because of what they get them, what they symbolize, and

what they allow them to achieve, experience, and feel. In many ways

credit cards are the fulfillment of the ultimate dream of this country’s

founders—they offer life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

—Richard A. Feinberg and Cindy Evans

F

URTHER READING:

Buchan, James. Frozen Desire: The Meaning of Money. New York,

Farrar Straus Giroux, 1997.

Dietz, Robert. Expressing America: A Critique of the Global Credit

Card Society. Thousand Oaks, California, The Pine Forge Press

Social Science Library, 1995.

Evans, David S., and Richard Schmalensee. Paying with Plastic: The

Digital Revolution in Buying and Borrowing. Cambridge, Massa-

chusetts, MIT Press, 1999.

Galanoy, Terry. Charge It: Inside the Credit Card Conspiracy. New

York, G.T. Putnam and Sons, 1981.

Hendrickson, Robert A. The Cashless Society. New York, Dodd

Mead, 1972.

Klein, Lloyd. It’s in the Cards: Consumer Credit and the American

Experience. Westport, Connecticut, Praeger, 1997.

Mandell, Lewis. Credit Card Use in the United States. Ann Arbor,

Michigan, The University of Michigan, 1972.

Ritzer, George. Expressing America: A Critique of the Global Credit

Card Economy. Thousand Oaks, California, Pine Forge Press, 1995.

Simmons, Matty. The Credit Card Catastrophe: The 20th Century

Phenomenon That Changed the World. New York, Barricade

Books, 1995.

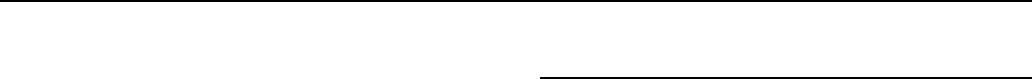

Creedence Clearwater Revival

By the late 1960s, when Creedence Clearwater Revival (CCR)

released its first album, rock ‘n’ roll was transforming into rock, the

more ‘‘advanced’’ and ‘‘sophisticated’’ cousin of the teenaged riot

whipped up by Elvis Presley and Little Richard. While their contem-

poraries (Moody Blues, Pink Floyd, King Crimson, etc.) were ex-

panding the sonic and lyrical boundaries of Rock ‘n’ Roll, CCR

bucked the trend by returning to the music’s roots. On their first

album and their six subsequent releases, this Bay Area group led by

John Fogerty fused primal rockabilly, swamp-boogie, country, r&b

and great pop songwriting, and—in doing so—became one of the

biggest selling rock bands of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Most of the members of CCR played in what were essentially bar

bands around San Francisco and its suburbs. Along with El Cerrito

junior high school friends Stu Cook and Doug ‘‘Cosmo’’ Clifford,

Tom and John Fogerty formed the Blue Velvets in the late 1950s. The

group eventually transformed into the Golliwogs, recording a number

of singles for the Berkeley-based label, Fantasy, and then changed its

name to Creedence Clearwater Revival in 1967. If the Blue Velvets

and the Golliwogs were dominated by Tom Fogerty, then Creedence

Clearwater Revival was John Fogerty’s vehicle, with John writing

and singing the vast majority of CCR’s songs. It was clear that John

Fogerty’s influence was what made the group popular, because under

Tom’s control, the Golliwogs essentially went nowhere. Further,

when John let other members gain artistic control on CCR’s Pendu-

lum, that album became the first CCR album not to go platinum.

Like Bruce Springsteen, John Fogerty’s songs tackle subjects

that cut deep into America’s core; and like any great artist, Fogerty

was able to transcend his own experience and write realistic and

believable songs (for instance, the man who wrote ‘‘Born on the

Bayou’’ had never even been to Louisiana’s bayous until decades

later). Despite Fogerty’s talents as a songwriter, CCR’s first hits from

its debut album were covers—Dale Hawkins’ ‘‘Suzie Q’’ and Screamin’

Jay Hawkins’ ‘‘I Put a Spell on You.’’ But with the release of ‘‘Proud

Mary’’ backed with ‘‘Born on the Bayou’’ from CCR’s second

album, the group released a series of original compositions that

dominated the U.S. Billboard charts for three years.

Despite its great Top Forty success and its legacy as the

preeminent American singles band of the late 1960s, CCR was able to

cultivate a counter-cultural and even anti-commercial audience with

its protest songs and no-frills rock ‘n’ roll. Despite the fact that they

were products of their time, ‘‘Run Through the Jungle,’’ ‘‘Fortunate

Son,’’ ‘‘Who’ll Stop the Rain,’’ and CCR’s other protest songs

remain timeless classics because of John’s penchant for evoking

nearly-universal icons (for North American’s, at least) rather than

specific cultural references.

John’s dominance proved to be the key to the band’s success and

the seeds of its dissolution, with Tom leaving the group in 1971 and

John handing over the reigns to be split equally with Stu Cook and

Doug Clifford, who equally contributed to the group’s last album,

Mardi Gras, which flopped. Tom released a few solo albums, and so

did John, who refused to perform his CCR songs well until the early

1990s as the result of a bitter legal dispute that left control of the CCR

catalog in the hands of Fantasy Records. One of the most bizarre

copyright infringement lawsuits took place when Fantasy sued Fogerty

for writing a song from his 1984 Centerfield album that sounded too

much like an old CCR song. After spending $300,000 in legal fees and

CRICHTONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

631

Creedence Clearwater Revival

having to testify on the stand with his guitar to demonstrate how he

wrote songs, Fogerty won the case.

—Kembrew McLeod

F

URTHER READING:

Bordowitz, Hank. Bad Moon Rising: The Unauthorized History of

Creedence Clearwater Revival. New York, Schirmer Books, 1998.

Hallowell, John. Inside Creedence. New York, London, 1971.

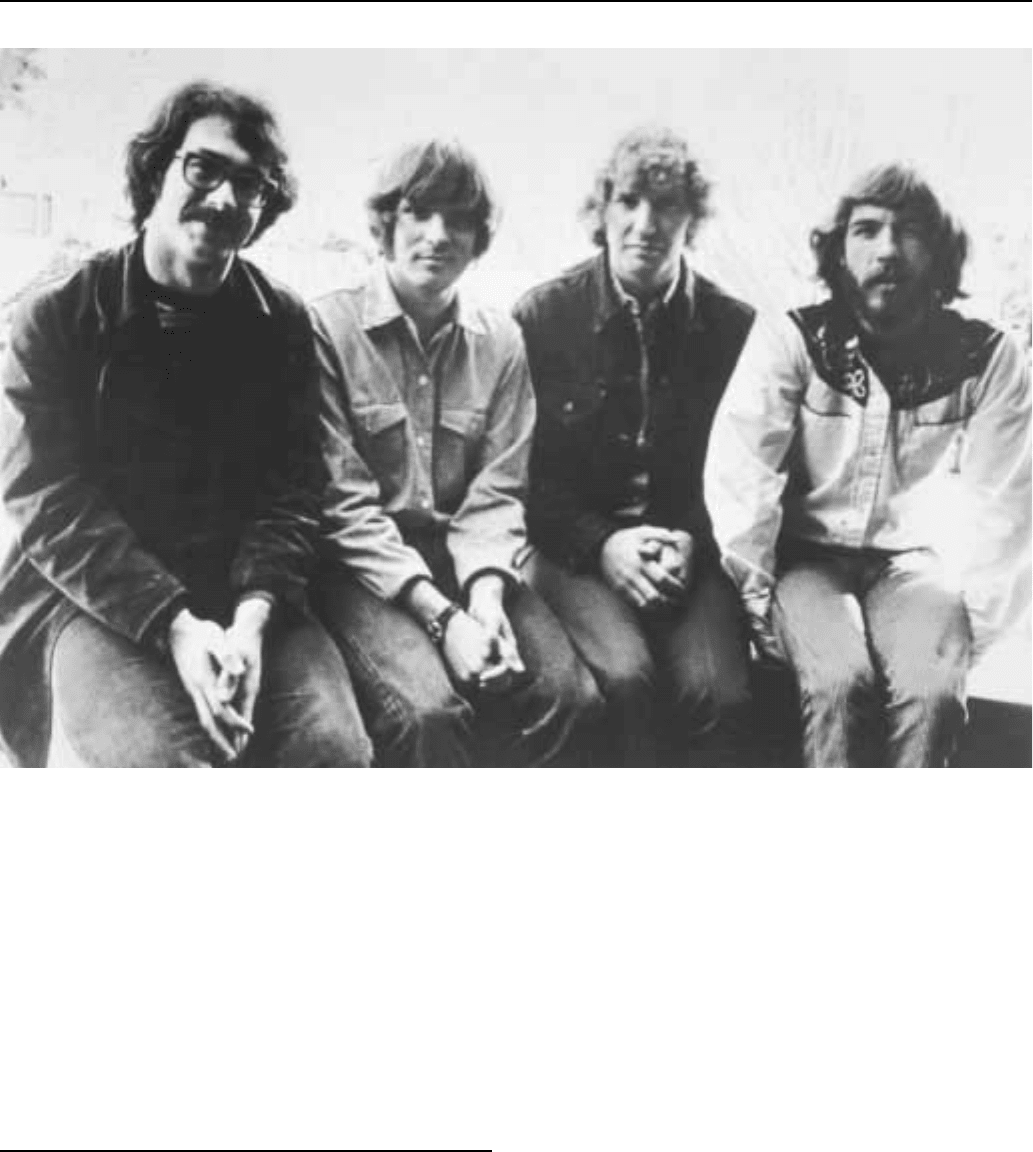

Crichton, Michael (1942—)

Published in 1969, The Andromeda Strain established Michael

Crichton as a major best-selling novelist whose popularity was due as

much to the timing and significance of his subject matter as to the

quality of his writing and the accuracy of his research. As Crichton

had correctly judged, America was ready for a tale that treated both

the rationalism and the paranoia of the Cold War scientists’ response

to a biological threat. From that first success onwards, Crichton

continued to embrace disagreeable or disturbing topical trends as a

basis for exciting, thriller-related fiction. That several have been

made into highly commercial movies, and that he himself expanded

his career into film and television, has made him a cultural fixture in

late twentieth-century America. If this was in doubt, his position was

cemented by ER, the monumentally successful television series,

which he devised.

Born on October 23, 1942 in Chicago, Illinois, by the time The

Andromeda Strain appeared, Crichton had received his A.B. degree

summa cum laude from Harvard, completed his M.D. at Harvard

Medical School, and begun working as a post-doctoral fellow at the

Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Most impressively, he had

already published six novels (under various pseudonyms), written

largely during weekends and vacations, while still at medical school.

As an undergraduate, he had intended to major in English, but poor

grades convinced him that no amount of creative talent would deter

Harvard’s faculty from altering its absurdly high expectations. Incipi-

ent scientist that he was, Crichton tested this theory by submitting an

essay by George Orwell under his own name, and received a B-minus.

This tale, recounted in Crichton’s spiritual autobiography, Trav-

els, perhaps explains his own lack of interest in producing anything

other than commercial fiction. As a result, his journey through

medical school seems, in retrospect, more of a detour than a career

path, for, by the end of his schooling, he had decided once and for all

to become a writer. During his final rotation Crichton concentrated

CRIME DOES NOT PAY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

632

Michael Crichton

more on the emotional than the physical condition of his patients,

research that formed the basis of his non-fiction work, Five Patients:

A Hospital Explained.

But it was The Andromeda Strain that permanently changed the

trajectory of his future. His previous novels have all fallen out of print,

with the exception of A Case of Need, published under the pseudonym

Jeffrey Hudson and winner of the 1968 Edgar Award from the

Mystery Writers of America. While the success of The Andromeda

Strain lifted Crichton’s career to new heights, it did not prevent him

from completing other less successful works already in progress. In

1970 and 1971, using the name John Lange, he finished three more

novels (Drug of Choice, Grave Descend, and Binary), and with his

brother Douglas, co-wrote Dealing, under the prescient name Mi-

chael Douglas. (The actor would star in the film versions of several of

Crichton novels). With three of his novels already filmed—The

Andromeda Strain (1970), Dealing (1972), and A Case of Need

(retitled The Carey Treatment, 1972)—Crichton, who had directed

the made-for-TV film Pursuit (1972) made his feature film directing

debut in 1973 with Westworld. Starring Yul Brynner, the film was

adapted from his futuristic thriller Binary (1971). Crichton now

pursued a dual career as moviemaker and writer, having published the

second novel to appear under his own name, The Terminal Man, in

1972. Dealing with a Frankenstein-type experiment gone haywire, it

confirmed its author’s storytelling powers, sold in the millions, and

was filmed in 1974.

Through the rest of the 1970s and into the 1980s Crichton the

author continued to turn out such bestsellers as The Great Train

Robbery (1975), Congo (1980), and Sphere (1987), but Crichton the

director fared less well. His successes with Coma (1977), a terrific

nailbiter based on Robin Cook’s hospital novel and starring the real

Michael Douglas, and The Great Train Robbery (1978), were offset

by such mediocrities as Looker (1981), Runaway (1984), and Physi-

cal Evidence (1989). A major turnaround came when he stopped

directing and concentrated on fiction once again. The fruits of his

labors produced Jurassic Park (1990), Rising Sun (1992), Disclosure

(1994), and Lost World (1995). All were bestsellers, with Rising Sun

and Disclosure leaving a fair share of controversy in their wake—the

last particularly so after the film, starring Michael Douglas and Demi

Moore, was released. In the meantime, Crichton shifted from director

to producer, convincing NBC to launch ER, which he created and

which had been his dream for 20 years. By the end of the 1990s, he

was an established and important presence in Hollywood as well as in

publishing, enjoying a professional longevity given only to a handful

of popular novelists and screenwriters.

Not unlike Tom Clancy, whose success came in the 1980s,

Crichton is a masterful storyteller who has been credited with the

invention of the modern ‘‘techno-thriller.’’ His prose is clear and

concise; his plotting strong; his research accurate and, at times, eerily

prescient. On the other hand, in common with many fiction writers

who depend heavily on premises drawn largely from the science

fiction genre, his character development is weak. Despite his protests

to the contrary, his penchant for using speculative science as the basis

for much of his fiction has landed him willy-nilly within the gothic

and science fiction traditions. In Michael Crichton: A Critical Com-

panion, Elizabeth Trembley details the extent to which Crichton’s

work revisits earlier gothic or science fiction classics, from H. Rider

Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, for example, to Jurassic Park, a

modern retelling of H. G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau.

Michael Crichton’s popularity is perhaps best explained by his

intuition for presenting through the medium of fiction our own

anxieties in consumable form. Often fiction relieves anxieties by

reconfiguring them as fantasy. Crichton senses that we worry about

biological weapons (The Andromeda Strain), mind control technolo-

gy (The Terminal Man), human aggression (Sphere), genetic engi-

neering (Jurassic Park), and competitive corporate greed (Rising Sun

and Disclosure). His gift is the ability to turn these fears into a form

that lets us deal with them from the safety of the reading experience.

—Bennett Lovett-Graff

F

URTHER READING:

Crichton, Michael. Travels. New York, Ballantine Books, 1988.

Heller, Zoe. ‘‘The Admirable Crichton.’’ Vanity Fair, January,

1994, 32-49.

Trembley, Elizabeth. Michael Crichton: A Critical Companion.

Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood, 1996.

Crime Does Not Pay

Crime Does Not Pay was a comic book published from 1942-

1955 by the Lev Gleason company. Inspired by the MGM documen-

tary series of the same name, Crime featured material based loosely

on true criminal cases. The stories indulged in graphic violence,

sadism, and brutality of a sort that was previously unheard of in

children’s entertainment. Bullet-ridden corpses, burning bodies, and

CRISISENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

633

horrific gangland tortures were among the more predictable themes

found in these comic books.

An unusual comic book when it first appeared amidst the

superheroes of the World War II era, Crime found a huge audience

after the war. Arguably the first ‘‘adult’’ comic book, Crime also

became one of the most popular titles ever, selling in excess of one

million copies monthly. When Crime’s formula became widely

imitated throughout the industry, it attracted the wrath of critics who

charged that crime comic books caused juvenile delinquency.

—Bradford Wright

F

URTHER READING:

Benton, Mike. Crime Comics. Dallas, Taylor Publishing, 1993.

Goulart, Ron. Over Fifty Years of American Comic Books.

Lincolnwood, Illinois, Mallard Press, 1991.

Crinolines

In 1859, French writer Baudelaire wrote that ‘‘the principal

mark of civilization . . . for a woman, is invariably the crinoline.’’ The

crinoline, or horsehair (‘‘crin’’) hoop, allowed women of the 1850s

and 1860s to emulate Empress Eugénie in ballooning skirts support-

ed by these Crystal Palaces of lingerie. From Paris to Scarlett

O’Hara, women moved rhythmically and monumentally during

‘‘crinolineomania’’ (1856-68), assuming some power if only by

taking up vast space. A culture of boulevards and specatorship prized

the volume of crinolines. In the 1950s, crinolineomania recurred:

prompted by Christian Dior’s New Look, any poodle skirt or prom

dress could be inflated by nylon crinolines as if to become the female

version of mammoth 1950s cars and automobile fins. A culture of big

cars valued the crinoline as well.

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Calzaretta, Bridget. Crinolineomania: Modern Women in Art, 1856-

68 (exhibition catalogue). Purchase, New York, Neuberger Muse-

um, 1991.

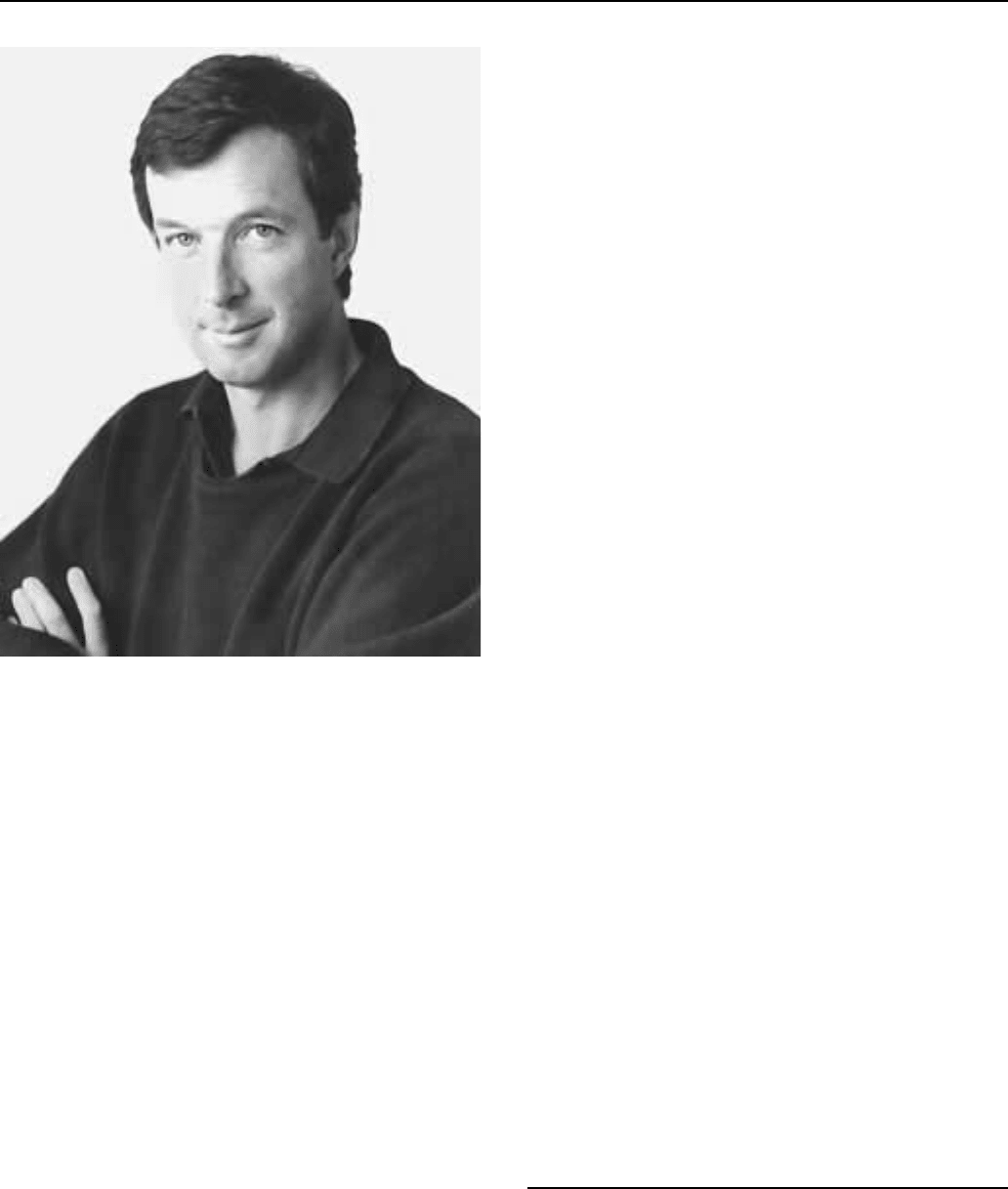

The Crisis

Founded as the monthly magazine of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People in 1910, the Crisis has played

an important role in the formation and development of African-

American public opinion since its inception. As the official voice of

America’s leading civil rights organization, the Crisis gained entry

into a variety of African-American and progressive white homes,

from the working class and rural poor to the black middle class.

Through the mid-1930s, the Crisis was dominated by the character,

personality, and opinions of its first editor and NAACP board

member, W. E. B. Du Bois. Because of his broad stature within black

communities, Du Bois and the NAACP were synonymous for many

African Americans. One of his editorials or essays could literally

sway the opinions of thousands of black Americans.

The Crisis

The teens were a time of dynamic change within black commu-

nities as the Great Migration began to speed demographic shifts and

African-American institutions grew and expanded. As black newspa-

pers and periodicals gained prominence within these rapidly develop-

ing communities, the New York-based magazine the Crisis emerged

as one of the most eloquent defenders of black civil rights and racial

justice in the United States. During this era, the magazine led the

pursuit of a federal anti-lynching law, equality at the ballot box, and

an end to legal segregation. As war approached, the Crisis ran

vigorous denunciations of racial violence in its columns. Following a

bloody riot in east St. Louis in 1917, Du Bois editorialized with

melancholy, ‘‘No land that loves to lynch ‘niggers’ can lead the hosts

of the Almighty.’’ In the same year, after black servicemen rampaged

through the streets of Houston, killing seventeen whites and resulting

in the execution of thirteen African Americans, the Crisis bitterly

lamented, ‘‘Here at last, white folks died. Innocent, adventitious

strangers, perhaps, as innocent as the thousands of Negroes done to

death in the last two centuries. Our hands tremble to rise and exult, our

lips strive to cry. And yet our hands are not raised in exultation; and

yet our lips are silent, as we face another great human wrong.’’

After the initial success of black troops stationed in France

during the summer of 1918, Du Bois penned the controversial

editorial ‘‘Close Ranks.’’ In it, he wrote, ‘‘Let us, while this war lasts,

CROCE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

634

forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder

with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are

fighting for democracy. We make no ordinary sacrifice, but we make

it gladly and willingly with our eyes lifted to the hills.’’ Appealing to

the ideals of patriotism, citizenship, and sacrifice connected to

military service, the Crisis editors believed that by fighting a war ‘‘to

make the world safe for democracy,’’ African Americans would be in

a better position to expect a new era of opportunity and equality after

the war’s end. As the war drew to a close and black soldiers returned

home, the Crisis continued its determined efforts to secure a larger

share of democracy for African Americans. In ‘‘Returning Soldier,’’

the magazine captured the fighting spirit of the moment: ‘‘We

return. / We return from fighting. / We return fighting. Make way for

democracy! We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will

save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.’’

The next two decades, though, did not bear out the optimism of

Crisis editors. During the 1920s, as racial conservatism set in nation-

wide and the hopes of returning black soldiers dimmed, the Crisis

shifted its focus to the development of the cultural politics of the

‘‘New Negro’’ movement in Harlem. With the addition of celebrated

author Jessie Fauset to the editorial board, the Crisis printed essays

from Harlem Renaissance architect Alain Locke, as well as early

works of fiction and poetry by Fauset, Langston Hughes, and Zora

Neale Hurston, among others. The 1930s proved contentious years for

the Crisis as it went to battle with the Communist Party over the fate

of nine African Americans in the Scottsboro case. In addition, the

Depression put the magazine in financial peril. As Du Bois struggled

to find solutions to the dire circumstances facing most black Ameri-

cans, he published a series of essays advocating the creation of

‘‘urban black self-determination’’ through the creation of race-based

economic cooperatives. This stance irked many NAACP leaders who

saw the remarks as a repudiation of the organization’s integrationist

goals. The clash precipitated a split within the group which resulted in

the resignation of Du Bois from both the magazine and the NAACP

board in 1934.

What the Crisis lost in the departure of Du Bois, it regained with

the rapidly increasing membership of the NAACP during the Second

World War and the rising tide of civil rights protest throughout the

nation. While the magazine no longer had the stature, intellectual

respect, or skillful writing associated with Du Bois, it remained an

important public African-American voice. In particular, as the NAACP

legal attack on segregation crescendoed in 1954 with the Brown v.

Board of Education decision, the Crisis ran a special issue dedicated

solely to the NAACP victory, featuring the full text of the decision,

historical overviews, and analysis. One editorial gloated, ‘‘The ’sepa-

rate but equal’ fiction as legal doctrine now joins the horsecar, the

bustle, and the five-cent cigar.’’ While the Crisis trumpeted the

victory, it also kept a pragmatic eye on the unfinished business of

racial justice in America, stating, ‘‘We are at that point in our fight

against segregation where unintelligent optimism and childish faith in

a court decision can blind us to the fact that legal abolition of

segregation is not the final solution for the social cancer of racism.’’

Over the next decade, as the NAACP struggled to find its place

in the post-Brown movement, the Crisis maintained its support of

nonviolent civil rights activity, although it no longer set the agenda.

Thurgood Marshall, in an article on the student sit-in wave sweeping

the South in 1960, compared Mississippi and Alabama to South

Africa and argued, ‘‘Young people, in the true tradition of our

democratic principles, are fighting the matter for all of us and they are

doing it in the most effective way. Protest—the right to protest—is

basic to a democratic form of government.’’ Of the 1963 ‘‘Jobs and

Freedom’’ march on Washington, D.C., the Crisis beamed, ‘‘Never

had such a cross section of the American people been united in such a

vast outpouring of humanity.’’ Similarly, in 1964, with the passage of

the historic Civil Rights Act, the Crisis editorialized, ‘‘[the Act] is

both an end and a beginning: an end to the Federal Government’s

hands-off policy; a beginning of an era of Federally-protected rights

for all citizens.’’

As the movement spun off after 1965 toward Black Power,

increasing radicalization and, in some cases, violence, the NAACP

and the Crisis began to lose their prominent position in shaping

African-American attitudes and opinions. Against these new politics,

the Crisis appeared more and more conservative. Continuing to

oppose violent self-defense and separatism, the Crisis also came out

against radical economic redistribution as well as the Black Studies

movement of the late sixties and early seventies. Over the next two

decades, the Crisis evolved into a more mainstream popular maga-

zine, upgrading its pages to a glossy stock and including more

advertisements, society articles, and human interest stories. Unable to

recapture the clear programmatic focus that had driven its contents

during the previous fifty years, the Crisis articles tended to be more

retrospective and self-congratulatory than progressive. In the late

1980s, the Crisis took a brief hiatus but reappeared in the 1990s in a

revised form, focusing primarily on national politics, cultural issues,

and African-American history.

—Patrick D. Jones

F

URTHER READING:

Ellis, Mark. ‘‘‘Closing Ranks’ and ‘Seeking Honors’: W. E. B. Du

Bois in WWI.’’ Journal of American History. Vol. 79, No. 1, 1992.

Hughes, Langston. Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP. New

York, Berkeley Publishing, 1962.

Lewis, David Levering. W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race. New

York, Holt Publishing Company, 1994.

———. The Writings of W. E. B. Du Bois.

Waldon, Daniel, ed. W. E. B. Du Bois: The Crisis Writings. Green-

wich, Connecticut, Fawcett Publishing, 1997.

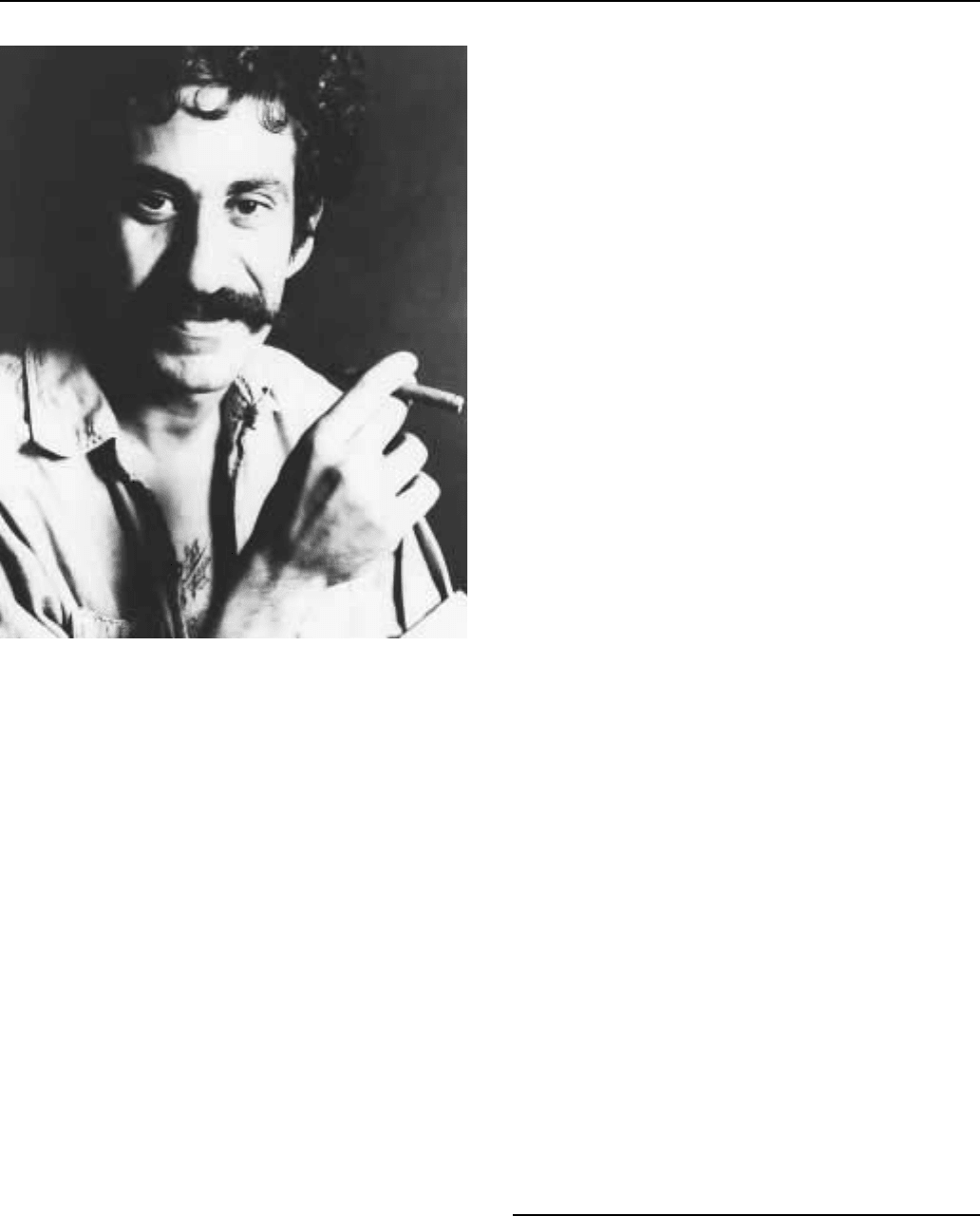

Croce, Jim (1943-1973)

Singer and songwriter Jim Croce is remembered for beautiful

guitar ballads like ‘‘Time In a Bottle’’ and, in contrast, his upbeat

character-driven narratives like ‘‘Bad, Bad Leroy Brown’’ that deftly

combined folk, blues, and pop influences. Croce’s brief but brilliant

musical career was tragically cut short by his death in a plane

accident in 1973.

Born to James Alford and Flora Croce in Philadelphia, Pennsyl-

vania, Croce’s interest in music got off to a slow start. He learned to

play ‘‘Lady of Spain’’ on the accordion at the age of five, but didn’t

really take music seriously until his college years. He attended

Villanova College in the early 1960s, where he formed various bands

and played parties. One such band had the opportunity to do an

Embassy tour of the Middle East and Africa on a foreign exchange

CRONKITEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

635

Jim Croce

program, which encouraged Croce to focus on his music. He earned a

degree in psychology from Villanova in 1965.

The music career came slowly, though, interrupted by the other

odd jobs he took to make a living. Croce worked in construction,

welded, and even joined the army. He spun records as a university

disc jockey on a folk and blues show in Philadelphia and wrote ads for

a local R&B station. He married Ingrid in 1966, and the two spent the

summer teaching at a children’s camp in Pine Grove, Pennsylvania.

He taught guitar, and she taught ceramics and leather crafts. The

following autumn he served as a teacher for problem students at a

Philadelphia High School.

Finally becoming truly serious about a career in music, Croce

moved to New York in 1967 where he and his wife Ingrid played folk

clubs and coffee houses. By 1969, the pair were signed to Capital

Records where they released an album called Approaching Day. The

album’s lack of success led the couple to give up New York and return

to Pennsylvania. Jim started selling off guitars, took another job in

construction, and later worked as a truck driver. Ingrid learned how to

can foods and bake bread to help stretch the budget. On September 28,

1971, they had a son, Adrian James Croce.

But Croce never lost his love of music, and he played and sang

on some commercials for a studio in New York. His break came when

Croce sent a demo tape to Tommy West, a Villanova college pal who

had found success as a New York record producer. West and his

friend Terry Cashman helped Croce land a contract with ABC

records. He also had a fortuitous meeting with guitarist Maury

Muehleisen while working as a studio freelancer. Croce had played

backup guitar on Muehleisen’s record, Gingerbread. The album

flopped, but Croce remembered the young guitarist and called him in

to work with him. The two worked closely in the studio, trading

rhythm and lead parts. The first album, You Don’t Mess Around with

Jim, was a huge success, giving Croce two top ten hits with the title

track and ‘‘Operator (That’s Not The Way It Feels).’’ Before long

Croce was a top-billing concert performer, known as much for his

friendly and charming personality as for his songs.

His second album, Life and Times, had a hit with the July, 1973,

chart topper ‘‘Bad, Bad Leroy Brown.’’ This first blush of success

turned bittersweet for his family and friends, however. Leaving a

concert venue at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches,

Louisiana on September 20, 1973, Croce’s plane snagged the top of a

pecan tree just past the runway, and he and Maury Muehleisen, as well

as four others, were killed. Croce is buried at Haym Salomon

Memorial Park in Frazer, Pennsylvania. The third album, I’ve Got a

Name, was released posthumously, and the hits kept coming. The next

chart hit was the title track, and ‘‘Time In a Bottle’’ was the number

one hit of the year in 1973. The following year, ‘‘I’ll Have to Say I

Love You in a Song’’ and ‘‘Workin’ at the Car Wash Blues’’ hit the

charts. The ongoing string of hits only highlighted the tragic loss of a

performer who was just coming into his own.

Jim’s widow Ingrid opened Croce’s Restaurant and Jazz Bar

1985 in San Diego’s Gaslamp Quarter in Jim’s memory. The restau-

rant features musical acts nightly and is decorated with Jim Croce

memorabilia. Ingrid Croce also wrote a book of recipes and memories

called Thyme in A Bottle. Son A. J. Croce started his own musical

career in the 1990s. He released his eponymous first album in 1993, a

1995 follow-up, That’s Me in the Bar, and 1997’s Fit to Serve. He said

of his father, ‘‘I think the most powerful lesson I learned from him

was the fact there is no reason to write a song unless there is a good

story there. He was a great storyteller and, for me, if there is any way

that we are similar, it’s that we both tell stories.’’

—Emily Pettigrew

F

URTHER READING:

Crockett, Jim. ‘‘Talking Guitar.’’ Guitar Player. April, 1973, 18.

Dougherty, S. ‘‘Don’t Mess Around with A.J.’’ People. August 17,

1992, 105-06.

‘‘Epitaph for Jim.’’ Time. February 11, 1974, 56.

‘‘Jim Croce.’’ http://www.hotshotdigital.com/WellAlwaysRemem-

ber.3/JimCroceBio.html. February 1999.

‘‘Jim Croce: The Tribute Page.’’ http://www.timeinabottle.com. Feb-

ruary, 1999.

Makarushka, Mary. ‘‘At Last, He Got a Name.’’ Entertainment

Weekly. September 15, 1995, 124.

Nelton, S. ‘‘A Legend in Her Own Right.’’ Nation’s Business.

December, 1992, 14.

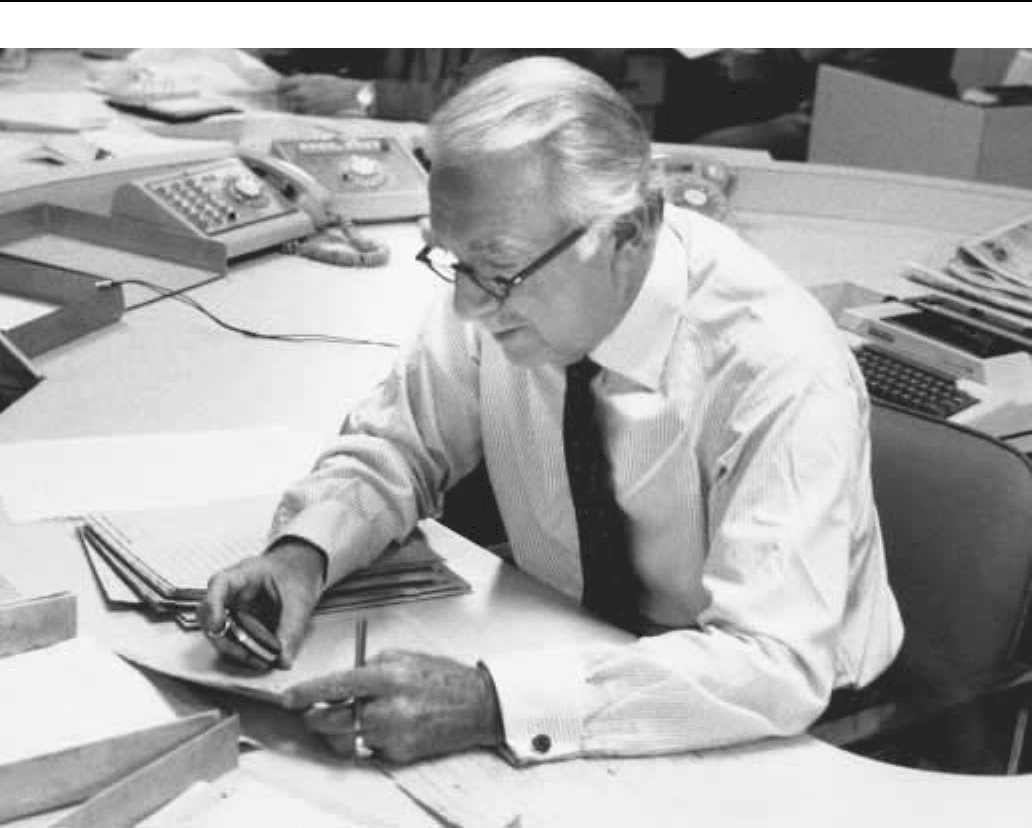

Cronkite, Walter (1916—)

Walter Cronkite’s 19-year tenure as anchorman of the CBS

Evening News was an uncanny match of man and era. Two genera-

tions of Americans came to rely upon his presence in the CBS

CRONKITE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

636

Walter Cronkite

television anchor chair in times of war and crisis, scandal and

celebration. His was a forthright, solemn presence in a time when

each new dawn brought with it the prospect of nuclear annihilation or

a second American civil war. Yet the master journalist was also a

master performer—Cronkite was able and quite willing to display a

flash of emotion or anger on the air when it suited him; this

combination of stoic professionalism and emotional instinct earned

the broadcaster two enduring nicknames: the man known familiarly

as ‘‘Uncle Walter’’ was also called ‘‘The Most Trusted Man in

America.’’ When Cronkite closed the Evening News each night with

his famous sign-off ‘‘And that’s the way it is,’’ few doubted he was

telling them the truth.

Cronkite’s broadcasting career had a unique prologue; the young

war correspondent did what few others dared: he turned down a job

offer from Edward R. Murrow. The CBS European chief was already

a legend; the radio correspondents known as ‘‘Murrow’s Boys’’ were

the darlings of the American press, even as they defined the traditions

and standards of broadcast journalism. Cronkite, however, preferred

covering the Second World War for the United Press. It was an early

display of his preference for the wire-service style and attitude; the

preference would mark Cronkite’s reporting for the rest of his career.

When Cronkite accepted a second CBS offer several years later, the

budding broadcaster found himself assigned—perhaps relegated—to

airtime in the new medium that seemed little more than a journalistic

backwater: television.

He anchored the local news at Columbia’s Washington, D.C.,

affiliate starting soon after the Korean War began in 1950, his

broadcast a combination of journalism and experimental theater.

There were no rules for television news, and Cronkite had come in on

the ground floor. He had little competition; few of the old guard

showed much interest in the new medium. Cronkite was pressed into

service to anchor the 1952 political conventions and election for CBS

television, his presence soon taken for granted in the network anchor

chair. Walter Cronkite had established himself firmly as the net-

work’s ‘‘face’’ in the medium which was, by now, quite obviously the

wave of the future.

He continued to anchor much of CBS’s special events coverage,

including the 1956 and 1960 political conventions. In 1962, he

succeeded Doug Edwards as anchor of the CBS Evening News, in

those days a fifteen-minute nightly roundup that found itself regularly

beaten in the ratings by the runaway success of NBC’s anchor team of

Chet Huntley and David Brinkley.

CRONKITEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

637

Ratings aside, however, television news was finally coming of

age; CBS news was expanding staff, adding bureaus and airtime. That

TV news veered away from the staged, hackneyed style of its most

obvious model, the movie newsreels—and instead became a straight-

forward, serious purveyor of hard news—is thanks in no small part to

the efforts and sensibilities of Cronkite and his colleagues. His

Evening News expanded to thirty minutes in September, 1963,

premiering with an exclusive interview of President John F. Kennedy.

Yet Cronkite, like Doug Edwards before him, regularly spoke to

an audience much smaller than that of Huntley and Brinkley. And

while it is Cronkite’s shirtsleeves pronouncement of the Kennedy

assassination that is usually excerpted on retrospective programs and

documentaries (‘‘From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently offi-

cial. . . President Kennedy. . . died. . . this afternoon. . . ’’), the simple

fact is that NBC was the clear audience choice for much of the early

and mid-1960s.

Cronkite’s ratings dropped so low during the 1964 Republican

convention, the behind-the-scenes turmoil growing so intense, that he

was removed from his anchor chair, replaced for the Democratic

convention by Robert Trout and Roger Mudd, two fine veteran

broadcasters whose selection nonetheless was a thinly veiled effort to

capture some of the Huntley-Brinkley magic. It didn’t work; a viewer

uprising and a well-timed prank (a walk through a crowded hotel

lobby with a high NBC executive) quickly led to Cronkite’s

re-instatement.

Meanwhile, Cronkite threw himself into coverage of the Ameri-

can space program. He displayed obvious passion and an infectious,

even boyish enthusiasm. His cries of ‘‘Go, baby, go!’’ became

familiar accompaniment to the roar of rockets lifting off from Cape

Canaveral. Cronkite anchored CBS’s coverage of every blast-off and

splashdown; arguably the single most memorable quote of his career

came as astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin touched down on

the moon the afternoon of July 20, 1969. ‘‘The Eagle has landed,’’

Armstrong radioed, and Cronkite added his benediction: ‘‘Gosh! Oh,

boy!’’ He later recalled it as the only time he’d come up speechless on

the air. That afternoon, Cronkite’s audience was more than that of

NBC and ABC combined. Huntley-Brinkley fever had cooled. Walter

Cronkite had become ‘‘the most trusted man in America,’’ and

his stature in American living rooms resounded throughout the

television industry.

This was the age in which local television news departments

strove to emulate the networks—not the other way around—and the

success of Cronkite’s dead-earnest Evening News led many local TV

newscasts soon to adapt a distinctly Cronkite-ish feel. Likewise,

there’s no official count of how many anchormen around the world,

subconsciously or not, had adapted that distinctive Cronkite cadence

and style. Politicians and partisans on all sides complained bitterly

that Cronkite and CBS were biased against them; this was perhaps the

ultimate tribute to the anchorman’s perceived influence on American

life in the late 1960s.

In truth, Cronkite had grown decidedly unenthusiastic about the

Vietnam War. A trip to Vietnam in the midst of the Tet offensive led

to arguably the most courageous broadcast of the anchorman’s career

. . . Cronkite returned home, deeply troubled, and soon used the last

few moments of a CBS documentary to call for an end to the war. It

was a shocking departure from objectivity, easily the most brazen

editorial stand since Ed Murrow criticized Senator Joe McCarthy

nearly a decade-and-a-half earlier. At the White House, President

Lyndon Johnson is said to have remarked ‘‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve

lost middle America.’’ Whether the anecdote is apocryphal is irrele-

vant; that it is widely accepted as fact is the real testament to

Cronkite’s influence as the 1960s drew to a close.

Cronkite rode his Evening News to ratings victory after victory

through the 1970s, the whole of CBS news now at the pinnacle of its

ability and influence. Cronkite cut short his summer vacation to

preside over the August 8, 1974 resignation of President Nixon; he

anchored an all-day-and-all-night television bicentennial party on

July 4, 1976; later he stubbornly closed every nightly newscast by

counting the number of days the American hostages had been held

captive in Iran. The Carter administration likely was not amused.

When the hostages’ release on January 20, 1981 coincided with the

inauguration of President Ronald Reagan, Cronkite held forth over

his last great news spectacular, calling the historic convergence of

events ‘‘one of the great dramatic days in our history.’’

By then, Cronkite was on his way out, giving up the anchor chair

to Dan Rather, narrowly forestalling Rather’s defection to ABC.

Cynics have long speculated Cronkite was, in fact, pushed aside to

make way for Rather, but everyone involved—including Cronkite—

has clung to the story that the veteran anchorman was genuinely tired

of the grind and had repeatedly asked to be replaced. His final

Evening News came March 6, 1981, his final utterance of ‘‘And that’s

the way it is’’ preceded by a brief goodbye speech . . . ‘‘Old

anchormen don’t go away, they keep coming back for more.’’ He

couldn’t have been more wrong.

Cronkite had not intended to retire completely upon stepping

down from the anchor chair, but to his utter astonishment, he found

the new CBS news management literally would not let him on the air.

An exclusive report from strife-torn Poland was given short shrift;

later, his already limited participation in the network’s 1982 Election

Night coverage was reportedly reduced even further when anchorman

Rather simply refused to cede the air to Cronkite. The new brass

feared reminding either viewers or a jittery, ratings-challenged Rather

of Cronkite’s towering presence; Rather himself was apparently

enjoying a little revenge. ‘‘Uncle Walter’’ had for years been known

behind-the-scenes as a notorious air-hog, filling airtime with his own

face and voice even as waiting correspondents cooled their heels.

Now, suddenly, the original ‘‘800-pound gorilla’’ was getting a taste

of his own medicine.

It only got worse. Cronkite’s fellow CBS board members

roundly ignored the elder statesman’s heated protests of mid-1980s

news budget cuts, even as it appeared the staid, substance-over-style

approach of Cronkite’s broadcasts was falling by the CBS wayside.

His legacy was fading before his very eyes. That he never pulled up

stakes and left the network (as a disgruntled David Brinkley had

recently bolted from NBC) is a testament either to true professional

loyalty . . . or an iron-clad contract.

In the 1990s, however, Cronkite made a broadcasting comeback.

He produced and narrated a series of cable documentaries, including a

multi-part retrospective of his own career; his 1996 autobiography

was a major bestseller. In late 1998, Cronkite accepted CNN’s offer to

co-anchor the network’s coverage of astronaut John Glenn’s return to

space. On that October day, Cronkite returned to the subject of one of

his great career triumphs: enthusiastic, knowledgeable coverage of a

manned spaceflight. It was thrilling for both audience and anchor; yet

it was also clear Cronkite’s day had come and gone. He was frankly a

bit deaf; and he thoroughly lacked the preening, all-smiles, shallow

aura of hype that seems to be a primary qualification for today’s news

anchors. His presence that day was, however, undoubtedly a glorious

reminder of what Cronkite had been to the nation for so long: the very

CROSBY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

638

manifestation of serious, hard news in the most powerful communica-

tions medium of the twentieth century. He was a rock, truly an anchor

in some of the stormiest seas our nation has ever navigated.

—Chris Chandler

F

URTHER READING:

Boyer, Peter. Who Killed CBS? New York, Random House, 1988.

Cronkite, Walter. A Reporter’s Life. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Joyce, Ed. Prime Times, Bad Times. New York, Doubleday, 1988.

Leonard, Bill. In the Storm of the Eye. New York, G.P. Putnam’s

Sons, 1987.

Slater, Robert. This... Is CBS. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey,

Prentice Hall, 1988.

Crosby, Bing (1903-1977)

Bing Crosby is widely recognized as one of the most influential

entertainers of all time. He first came to popularity as America’s most

popular crooner during the 1930s, with his much-copied low-key

manner, and during his long career he recorded more than sixteen

hundred songs. He also starred in a long string of highly successful

movies, including the classic Going My Way (1944), and, having

amassed a huge fortune, eventually became a major presence behind

the scenes in Hollywood.

Bing Crosby

Born Harry Lillis Crosby into a large family in Tacoma, Wash-

ington, Crosby grew up to study law at Gonzaga University in

Spokane but soon became more interested in playing drums and

singing with a local band. It was then that he adopted his professional

name, reportedly borrowing the ‘‘Bing’’ from his favorite comic

strip, The Bingville Bugle. In the early 1930s Crosby’s brother Everett

sent a record of Bing singing ‘‘I Surrender, Dear’’ to the president of

CBS. Crosby’s live performances from New York ended up being

carried over the national radio network for twenty consecutive weeks

in 1932. Crosby recorded more than sixteen hundred songs for

commercial release beginning in 1926 and ending in 1977. With his

relaxed, low-key manner and spontaneous delivery, Crosby set a

crooning style that was widely imitated for decades. At the time of his

death, he was considered the world’s best-selling singer. Crosby’s

records have sold in the hundreds of millions worldwide, perhaps

more than a billion, and some of his recordings have not been out of

print in more than sixty years. He received twenty-two gold records,

signifying sales of at least a million copies per record, and was

awarded platinum discs for his two biggest selling singles, ‘‘White

Christmas’’ (1960) and ‘‘Silent Night’’ (1970).

Crosby’s radio success led Paramount Pictures to contract him

as an actor. He starred in more than fifty full-length motion pictures,

beginning with The Big Broadcast of 1932 (1932) and ending with the

television movie Dr. Cook’s Garden (1971). His large ears were

pinned back during his early films, until partway through She Loves

Me Not (1934). His career as a movie star reached its zenith during his

association with Bob Hope. Crosby and Hope met for the first time in

the summer of 1932 on the streets of New York and in December

performed together at the Capitol Theater, doing an old vaudeville

routine that included two farmers meeting on the street. They did not

work together again until the late 1930s, when Crosby invited Hope to

appear with him at the opening of the Del Mar race track north of San

Diego. The boys reprised some old vaudeville routines that delighted

the celebrity audience. One of the attendees was the production chief

of Paramount Pictures, who then began searching for a movie vehicle

for Crosby and Hope and ended up finding an old script intended

originally for Burns and Allen, then later Jack Oakie and Fred

MacMurray. The tentative title was The Road to Mandalay, but the

destination was eventually changed to Singapore. To add a love

interest to the movie, the exotically beautiful Dorothy Lamour was

added to the main cast. Although The Road to Singapore was not

considered as funny as the subsequent ‘‘Road’’ pictures, the chemis-

try among the three actors came through easily and the film was a

hit nevertheless.

At least twenty-three of Crosby’s movies were among the top ten

box office hits during the year of their release. He was among the top

ten box office stars in at least fifteen years (1934, 1937, 1940, 1943-

54), and for five consecutive years (1944-48) he was the top box

office draw in America. But real recognition of his talent as an actor

came with Going My Way: his performance as an easygoing priest

guaranteed him the best actor Oscar. His work in The Country Girl

(1954)—in which Crosby played an alcoholic down on his luck

opposite Grace Kelly—also received excellent critiques.

Crosby married singer Dixie Lee in 1930, and the couple had

four sons—Garry, Dennis and Phillip (twins), and Lindsay—all of

whom unsuccessfully attempted careers as actors. Widowed in 1952,

Crosby married movie star Kathryn Grant (thirty years his junior) in

1957. She bore him two more sons—Harry and Nathaniel—and a girl,

Mary , a TV and film actress famed for her role as the girl who shot J.

R. Ewing in the television series Dallas.