Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DRIVE-IN THEATERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

769

controversial. Dreiser simply ignored genteel aspirations and probity,

as he drew characters, logically and objectively, whose aspirations

were powerful enough for a poor girl to become a kept woman, for a

boy to kill a pregnant lover. Such desires destroy everything in their

paths and do not bring happiness, certainly not the familial stability

and financial security of the middle classes.

Dreiser was not the first novelist of his generation to write of the

squalor, poverty, and violence of the city; both Stephen Crane and

Frank Norris had done that before him, but he was singular in his

personal experience of poverty. This is undoubtedly a major reason he

was able to capture in such detail the desire to escape poverty and the

desire to possess wealth in a society that was in a period of transfor-

mation. The tide of migration from country to city; the impersonal

nature of the urban setting of factories, tenements, and department

stores; the contrast of poverty and wealth; the new culture of con-

spicuous consumption were all at the center of Dreiser’s work. Where

many of the new journalistic, realist writers around him attempted to

represent want, its nature and effects, Dreiser investigated wanting,

one of the central mechanisms of the twentieth century. His attempts

to delineate desire are what made him interesting and influential to

many writers from F. Scott Fitzgerald to Saul Bellow. It is in showing

a less intellectualized, aspirational, amorality deep within the Ameri-

can way of life that makes Dreiser the most radical, the most realistic,

writer of his generation.

—Kyle Smith

F

URTHER READING:

Moers, Ellen. Two Dreisers. New York, Viking, 1969.

Pizer, Donald. The Novels of Theodore Dreiser: A Critical Study.

Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1976.

Salzman, Jack. Theodore Dreiser: The Critical Reception. New York,

David Lewis, 1972.

The Drifters

When Clyde McPhatter formed The Drifters in 1953, a new

musical voice emerged. Combining doo-wop with gospel stylings,

rhythm and blues changed. Songs like ‘‘Money Honey’’ (1953) and

‘‘White Christmas’’ (1954), second only to Bing Crosby’s version,

increased their popularity. McPhatter left the group in 1954, and a

series of lead singers fronted the group until the arrival of Ben E. King

in 1959, who changed the Drifters’ image and sound. The baion, a

Latino rhythm, and the addition of strings made songs like ‘‘There

Goes My Baby’’ (1959) a success. From 1953 to 1966, The Drifters

proved a driving force for Atlantic Records from which many rising

musicians gained inspiration. The Drifters, who were inducted into

the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 1990, provided the music for a

southeastern coastal dance, ‘‘the shag.’’

—Linda Ann Martindale

F

URTHER READING:

Barnard, Stephen. Rock: An Illustrated History. New York, Schirmer

Books, 1986.

Hirshey, Gerri. Nowhere to Run: The Story of Soul Music. New York,

Da Capo Press, 1994.

Drive-In Theater

As early as 1928, Richard Hollingshead, Jr., owner of an auto

products business, was experimenting with screening films outdoors.

In the driveway of his New Jersey home he mounted a Kodak

projector atop his car and played the image on a nearby screen. In

time, Hollingshead refined and expanded his idea, registering his

patent for a drive-in theater in 1933. In doing so, he not only re-

created an American pastime, but he also contributed to American

popular culture for some time to come.

Drive-in theaters, also known as ‘‘ozoners,’’ ‘‘open-air opera-

tors,’’ ‘‘fresh-air exhibitors,’’ ‘‘outdoorers,’’ ‘‘ramp houses,’’ ‘‘un-

der-the-stars emporiums,’’ ‘‘rampitoriums,’’ and ‘‘auto havens,’’

were just that... places where people drove their cars to watch

movies on a huge outdoor screen. This was a seemingly preposterous

idea—one would drive to a gate, pay an admission fee, park their car

on a ramp to face the movie screen, and watch the movie from the car,

along with hundreds of other people. But the drive-in caught on

because it tapped into America’s love for both automobiles and

movies; going to the drive-in became a wildly popular pastime from

its inauguration in the 1930s through the 1950s.

The first drive-in opened on June 6, 1933, just outside of

Camden, New Jersey. The feature film was Wife Beware, a 1932

release starring Adolph Menjou. This movie was indicative of those

commonly shown at drive-ins: the films were always second rate (B

movies like The Blob or Beach Blanket Bingo) or second run. People,

however, did not object. Throughout the drive-in’s history its films

were always incidental to the other forms of attractions it offered

its patrons.

Around 1935, Richard Hollingshead sold most of his interest in

the drive-in, believing that the poor sound and visuals, the great

expense of construction, the limited choice of films, and other factors

(like reliance on good weather) were enough to keep investors and

customers alike from embracing this new form of entertainment. But

people did not mind that viewing movies outdoors was not qualita-

tively as ‘‘good’’ as their experiences watching movies at indoor

theaters. Just a few years after the first New Jersey drive-in opened,

there were others in Galveston, Texas, Los Angeles, Cape Cod,

Miami, Boston, Cleveland, and Detroit. By 1942 there were 95 drive-

ins in over 27 states; Ohio had the most at 11, and the average lot held

400 cars.

Drive-ins peaked in 1958, numbering 4,063. They proved to be

popular attractions for many reasons. After World War II, industries

turned back to the manufacture of domestic products and America

enjoyed a burgeoning ‘‘car culture.’’ In addition, the post-War ‘‘baby

boom’’ meant that there were more families with more children who

needed cheap forms of entertainment. Packing the family into a car

and taking them to the drive-in was one way to avoid paying a baby-

sitter, and was also a way that a family could enjoy a collective

activity ‘‘outdoors.’’ Indeed, in the 1940s and 1950s many owners

capitalized on this idea of the drive-in being a place of family

entertainment and offered features to attract more customers. Drive-

ins had playgrounds, baby bottle warmers, fireworks, laundry servic-

es, and concession stands that sold hamburgers, sodas, popcorn,

candy, hotdogs, and other refreshments.

DRIVE-IN THEATER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

770

A typical drive-in theater.

Although owners emphasized family activities, by the 1940s and

1950s teenagers had taken over rows at the drive-in to engage in more

private endeavors. Known as ‘‘passion pits,’’ drive-ins became places

where kids went to have sex, since they could not go to their parents’

houses but did have access to automobiles. Therefore, families parked

their cars in the front rows, dating teens sat in the middle rows, and

teens having sex occupied the dark back rows. Sneaking into drive-ins

was another popular teenage activity, with kids hiding in the trunk

until the car was parked well away from the entrance booth. Teenag-

ers from the 1960s on also used drive-ins as places to drink alcohol

and smoke marijuana.

In the late 1940s, drive-ins became more popular than indoor

theaters. One improvement that led to this was the development of a

viable in-car speaker through which to hear a movie’s sound. Before

the implementation of individualized speakers, drive-in owners used

‘‘directional sound,’’ three central speakers that projected the mov-

ie’s soundtrack over the entire drive-in. The sound was not only

distorted, but also was nearly impossible for the cars in the back rows

to hear. In addition, it was so loud that owners received complaints

from neighbors who were usually unhappy about a drive-in’s pres-

ence to begin with. The first in-car speakers were put into production

by RCA in 1946. In the 1950s people began experimenting with

transmitting movie sound over radio waves; this was not feasible until

1982, when 20-30 percent of drive-ins asked viewers to tune in their

radios. By 1985, 70 percent of drive-ins were using this sound

transmission technique.

The drive-in business started to stagnate in the 1960s and began

its decline in the 1970s. Land prices were increasing and drive-ins

took up a lot of space that could be made more profitable with other

ventures. By this time the original drive-ins were also in need of

capital improvements in which many owners chose not to invest. In

addition, theaters continued to get only B movies or second or third

run pictures, and the industry charged higher rental fees and required

longer runs, making it extremely difficult to compete with the

multiplex indoor cinemas.

In the 1980s, the drive-ins lost most of their key audiences—by

1983 there were only 2,935 screens. Families could stay home and

watch movies on cable television or on their video cassette recorders.

When teenagers found other places to have sex, the drive-in was no

longer a necessary locale for this activity. Due to gasoline shortages,

many people opted for compact cars, which were not comfortable to

sit in during double or triple movie features. By the 1990s there were

few drive-ins left; those that remained were reminders of an American

era that revered cars and freedom, with a little low-budget entertain-

ment thrown in.

—Wendy Woloson

DU BOISENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

771

FURTHER READING:

Jonas, Susan, and Marilyn Nissenson. Going, Going, Gone: Vanish-

ing Americana. San Francisco, Chronicle Books, 1994.

Sanders, Don. The American Drive-In Movie Theater. Osceola,

Wisconsin, Motorbooks International, 1997.

Segrave, Kerry. Drive-In Theaters: A History from Their Inception in

1933. Jefferson, North Carolina/London, McFarland & Co., 1992.

Drug War

The Drug War has attempted to diminish the flow of drugs into

the country, the manufacture of drugs within American borders and

the desire to use drugs with supply and demand tactics. On the supply

side, legislators have created severe penalties for possession and sale,

and toughened border patrols. To reduce the demand for drugs,

community programs, television campaigns and crime-watch pro-

grams educate citizens on the dangers of drug use and abuse. The

Drug War helped create drug-free school zones and increased penal-

ties for drug crimes that involved weapons.

Although the intensity of the drug war escalated in the mid-

1980s, legislators first enacted drug laws in 1914 with the Harrison

Narcotics Act which taxed narcotics and required licensure for those

who dispensed drugs. The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 categorized

marijuana as a narcotic for taxation and legislation purposes. Manda-

tory prison terms for drug use and sale were first introduced in the

1956 Narcotics Control Act.

Prior to the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act, highly addictive

opiates were the primary ingredient in the widely used elixirs. The

users were mostly middle-class women and their addictions were not

seen as a societal problem. The Civil War, however, brought the

subject of addictions to the forefront. When physicians treated

soldiers with morphine, they developed an addiction referred to as

‘‘soldier’s disease.’’

When drug abuse was confined to non-threatening social class-

es, public knowledge and debate were minimal. In 1900, society

pitied drug addicts. They were considered unfortunate citizens with

medical problems. By 1920, the drug user became known as a drug

fiend, an immoral outcast who spread his addictive disease to every-

one he touched. Anti-drug campaigns blamed Chinese immigrant

laborers who were railroad workers in California for bringing opiates

into the country and encouraging Americans to smoke opium. In the

South, anti-drug campaigns said blacks developed super-human

strength after sniffing cocaine. The Mexicans were blamed for

marijuana’s popularity.

Legislation and anti-drug campaigns helped contain drug use

until it became mainstream in the 1960s. In 1971, President Richard

Nixon declare the first a ‘‘war on drugs’’ when he coordinated drug

policies and legislation, and provided federal funds for education

and prevention. He consolidated federal agencies into the Drug

Enforcement Agency.

Cocaine use rose in the 1970s and 1980s. With the media

sensationalism of such events as the death of Boston Celtic Len Bias

and the arrest and conviction of Manuel Noriega, the drug war grew

rapidly. Despite the lack of proof that a national drug use epidemic

existed, Americans bought the media portrayal of the ‘‘crack baby’’

and inner city drug busts. In reality, the ‘‘crack baby’’ was the result

of poverty and malnutrition and crack the result of prohibition. The

television reports of inner-city warfare and drug busts pinpointed

young black men as the primary perpetrators.

By the mid-1980s, Congress and most state legislators enacted

mandatory prison sentences based on the weight or quantity of a drug.

The majority of federal and state drug offenders incarcerated in the

1990s were low-level sellers and dealers. High level traffickers and

other dealers with information to share would trade information for

lenient sentences. The prison industry grew faster than any other

American industry in the 1990s and Americans incarcerated more of

its own citizens than any other nation in the world.

The Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and 1988 set draconian penalties

for drug possession and sale, including life in prison to property

forfeiture. Other measures designed to curtail drug use and sale

include denying convicted ex-drug offenders social programs such as

government-backed college loans and grants, and welfare assistance.

The Omnibus Crime Act of 1984 allowed police to confiscate

property without due process. Authorities only needed an accusation

or suspicion to enter such private domains as homes and cars, and

conduct warrantless searches and seizures. Many critics argue that

this practice violates basic personal liberties.

In the 1990, critics of the Drug War stated that American drug

policies failed to put a dent in the drug trade. The U.S. government

spent billions of dollars each year to improve border interdiction,

increase the number of drug arrests and convictions, and build more

prisons to house drug offenders.

The Drug War is also known for such issues as medical marijua-

na availability, legalization and decriminalization. Critics of the drug

war argue that prohibition increases crime, deepens social and class

conflict and defies basic democratic ideals. It increases health prob-

lems by denying treatment to and incarcerating addicts. It tears

families apart by incarcerating small-time users and sellers for long

prison sentences. It promotes poverty by denying welfare and educa-

tional assistance to ex-offenders and their dependents, and increases

recidivism. Critics relate issues such as AIDS, IV drug use, street-

level dealers, and gang-warfare to drug prohibition, not drug use.

—Debra Lucas Muscoreil

F

URTHER READING:

Gray, Mike. Drug Crazy: How We Got Into This Mess and How We

Can Get Out. New York, Random House, 1998.

Lindesmith, Alfred R. The Addict and the Law. Bloomington, Indiana

University Press, 1965.

Musto, David F. The American Disease: Origins of Narcotics Con-

trol. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1973.

Wisotsky, Steven. Beyond the War on Drugs: Overcoming a Failed

Public Policy. Buffalo, Prometheus Books, 1990.

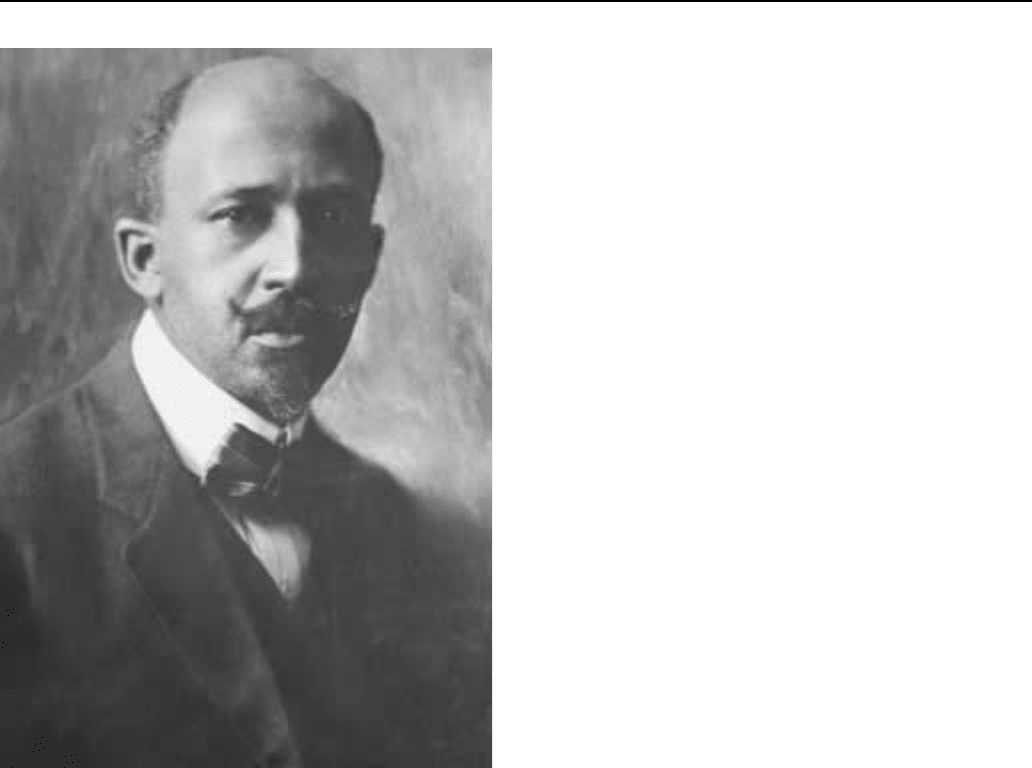

Du Bois, W. E. B (1868-1963)

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois is remembered as one of

twentieth-century America’s foremost black leaders, intellectuals,

and spokesmen. Multi-talented, in a long life he wrote as a sociolo-

gist, historian, poet, short story writer, novelist, autobiographer, and

editor—and in all of these roles he was a crusading champion of racial

justice. Though his ideological outlook changed many times during

DU BOIS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

772

W. E. B. Du Bois

his life, through phases of Darwinism, elitism, socialism, Pan-

Africanism, voluntary self-segregation, and ultimately official com-

munism, Du Bois consistently reiterated the view that the major

problem of the twentieth century was ‘‘the problem of the color-

line.’’ As historian Eric Sundquist has noted, Du Bois was born in

Great Barrington, Massachusetts, 1868, the same year as the Four-

teenth Amendment to the Constitution was adopted, and spent his life

attempting to make the principles, promises, and protections of this

landmark political article a reality for black Americans.

Despite the complex mixture of a racial background he summa-

rized as ‘‘a flood of Negro blood, a strain of French, a bit of Dutch, but

thank God! no ’Anglo-Saxon,’’’ the young Du Bois soon learned that

his black ancestry assumed the greatest significance in the minds of

his white school companions, the fact of his darker skin placing a

‘‘vast veil’’ between their social worlds. An exceptional student, Du

Bois won a scholarship to enter Fisk University in 1885. The

Nashville black college gave him the experience of extreme Southern

racism and a new racial identity fostered by exposure to the region’s

strong sense of African American culture and community. Moved by

the religious faith and ‘‘sorrow songs’’ he came across during his stay

in Tennessee, Du Bois later used these distinctive cultural expressions

to recover, highlight, and discuss the meaning of the black historical

experience in The Souls of Black Folk—which in turn inspired an

increased popular interest in black vernacular art forms. Graduating

from Fisk in 1888, Du Bois took a second undergraduate degree at

Harvard in 1890. In 1895 he became the first African American to

gain a doctoral degree from Harvard, and publishing his thesis in

1896, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United

States, 1638-1870, Du Bois launched successful academic and

publishing careers.

Accepting an invitation from the University of Pennsylvania to

conduct a study examining the condition of the black population in

Philadelphia, Du Bois published The Philadelphia Negro: A Social

Study in 1899—this seminal critical survey cemented his academic

reputation, and was cited as an influential model by sociologist

Gunnar Myrdal some 45 years later. Between 1897 and 1910, Du Bois

taught history and economics at Atlanta University. Here he had one

of his most productive spells as a writer, and began to advance a

political program that insisted on higher education as the foundation

for black racial progress. This emphasis upon the ideals of the

academy, together with his political activity in first, the Niagara

Movement, then later as one of the founders of the National Associa-

tion for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), placed Du

Bois in opposition to the more vocationally oriented and seemingly

accommodationist approach of Booker T. Washington. Editing and

directing the publication of a multi-volume study of African Ameri-

cans under segregation known as the Atlanta University Studies

series, and a journal The Horizon from 1907-1910, Du Bois was

gaining prominence as the self-appointed spokesman of what he

called the black community’s ‘‘Talented Tenth’’—‘‘developing the

Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the

contamination and death of the Worst, in their own and other races.’’

Du Bois enhanced this position as race leader in his role as the editor

of The Crisis from 1910 to 1934, the official organ of the NAACP that

grew to have over 100,000 subscribers by the end of World War I. In

this magazine, Du Bois featured the indignities and atrocities of

racism in the United States, including regular reports and investiga-

tions into lynching, yet his appeal remained for the most part limited

to the privileged literate Northern black middle classes and their

white supporters.

As a scholar, propagandist, and organizer of the Pan-Africanist

movement, Du Bois sought the means of uniting and making sense of

the apparent disparate experiences of diaspora blacks. Unlike another

of his African American political rivals of the 1920s, Marcus Garvey,

Du Bois did not advocate a return to Africa as the route to black

American political liberation. Instead, for Du Bois, Africa was more a

source of common identity for blacks, and in the continent’s battle

against European colonial domination, he found parallels with Afri-

can Americans struggling for civil rights. Following his decision to

leave the NAACP and resign his post at The Crisis, Du Bois no longer

commanded a popular audience. In this period, however, he returned

to Atlanta as Professor of Sociology and produced some of his most

significant work, writing a history of Black Reconstruction (1935),

Dusk of Dawn (1940), an autobiography, and founding Phylon: The

Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture (1940). Although he

briefly returned for a second period with the NAACP during World

War II, Du Bois’ politics of self-segregation and a Marxist interpreta-

tion of history soon put him at odds again with the organization’s

leadership and he was dismissed at the age of 80 in 1948. Du Bois’ life

ended in intellectual exile from the United States, joining the Com-

munist Party in 1961 and moving to Ghana where he died in 1963, the

day before Martin Luther King Jr. led the long planned Civil Rights

March on Washington.

DUNCANENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

773

Perhaps The Souls of Black Folk is Du Bois’ most valuable

literary legacy. Its recovery of the neglected black voices from the

days of slavery, potent idea of ‘‘double-consciousness,’’ and critique

of modernity, continues to influence generations of black novelists

(including Jean Toomer, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and Alice

Walker), historians, and scholars of culture and civilization in

equal numbers.

—Stephen C. Kenny

F

URTHER READING:

Du Bois, W.E.B. The Autobiography of W.E.B. DuBois. New York,

International Publishers, 1968.

———. The Souls of Black Folk. New York, Bantam, 1989.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Conscious-

ness. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1993.

Marable, Manning. W.E.B. DuBois: Black Radical Democrat. Bos-

ton, G.K. Hall, 1986.

Sundquist, Eric J., editor. The Oxford W.E.B. DuBois Reader. New

York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996.

Duck Soup

Though it failed at the box office upon its release, The Marx

Brothers’ 1933 feature Duck Soup is widely regarded as the comedy

team’s masterwork. By turns madcap, scathingly satirical, and genial-

ly surreal, the film chronicles the war fever that engulfs the mythical

nation of Freedonia when Groucho becomes its dictator. Harpo and

Chico play bumbling spies, with Zeppo relegated to the romantic

subplot. Some critics found an anti-war subtext in the proceedings,

but the brothers always denied any political agenda. Classic scenes

abound, including the famous ‘‘mirror routine’’ and a rousing musi-

cal finale. Woody Allen paid homage to Duck Soup’s enduring

comedic power by including scenes from it in the climax of his own

classic Hannah and Her Sisters in 1986.

—Robert E. Schnakenberg

F

URTHER READING:

Adamson, Joe. Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Sometimes Zeppo. New

York, Simon & Schuster, 1973.

Seaton, George. The Marx Brothers: Monkey Business, Duck Soup,

and a Day at the Races (Classic Screenplay). New York, Faber &

Faber, 1993.

The Dukes of Hazzard

The Dukes of Hazzard television show, airing on CBS from 1979

to 1985, blended down-home charm, handsome men, beautiful wom-

en, rip-roaring car chases, and the simple message of good triumphing

over evil; this successful combination made the program a ratings

success and a longstanding campy cult favorite. The Dukes were

country cousins Bo, Luke, and Daisy Duke, who lived in backwoods

Hazzard County on their Uncle Jesse’s farm. The formula storyline

usually involved the Dukes versus the town’s gluttonous bigwig,

Boss Hogg, and his lackey, Sheriff Rosco P. Coltrane. Episodes were

liberally punctuated with raucous car chases in their orange 1969

Dodge Charger, the ‘‘General Lee,’’ and Daisy’s trademark short

shorts inspired a 1993 hit rap song, ‘‘Dazzey Dukes,’’ which led to the

term’s use as a synonym for such apparel. The cast reunited for a

television movie on CBS in 1997.

—Geri Speace

F

URTHER READING:

Baldwin, Kristen. ‘‘Bringing Up Daisy: Bach Puts Up Her ‘Dukes.’’’

Entertainment Weekly. April 25, 1997, p. 54.

Bark, Ed. ‘‘‘Seinfeld,’ ‘Dukes,’ Yada, Yada, Yada.’’ The Dallas

Morning News, April 24, 1997, p. 1C.

Graham, Jefferson. ‘‘The ‘Dukes’ Ride High Again in Nashville

Network Reruns.’’ USA Today. August 14, 1996, p. 3D.

Werts, Diane. ‘‘Hazzard-ous Material.’’ Newsday. April 20,

1997, p. C24.

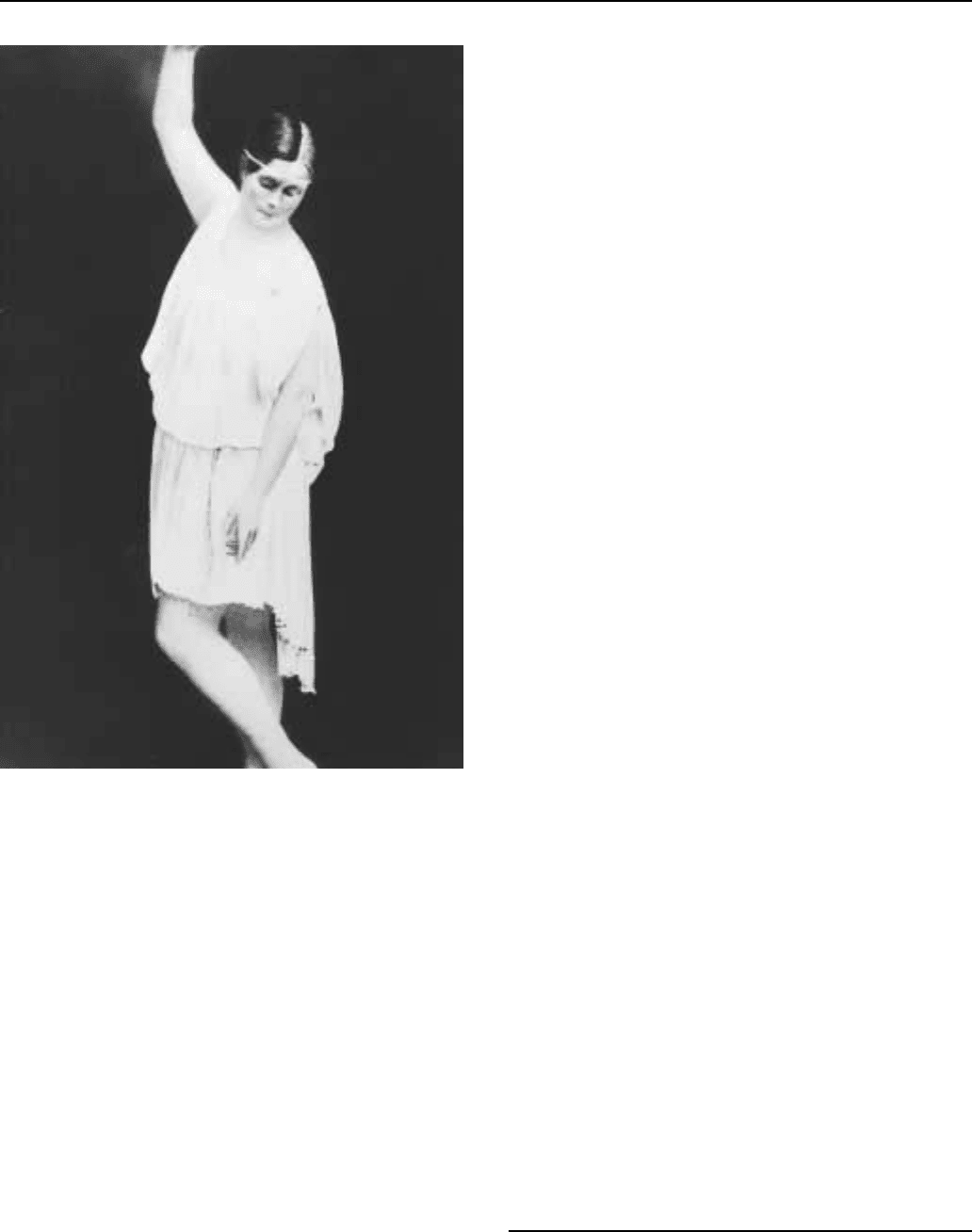

Duncan, Isadora (1877-1927)

The great American icon of dance, Isadora Duncan, who rose to

prominence early in the twentieth century and met a tragic death at

age 50, was ahead of her time in both her artistic ideals, her modes of

physical expression, and her controversial private life. Greatly ad-

mired by many, she also became an object of scorn and derision,

mocked for her uninhibited approach to her work and pilloried for her

scandalous love affairs and ‘‘bohemian’’ associations and lifestyle.

Ironically, Isadora Duncan’s art has always been more highly valued

abroad than in her native land, but her cultural influence in America

was considerable. The development of the modern dance form as

exemplified by Martha Graham and her contemporaries and succes-

sors owed much to Duncan’s unshakable belief in the power and force

of female self-expression.

Angela Isadora Duncan was born in San Francisco, the daughter

of poor but liberal, art-loving parents, who gave relatively free rein to

their children. Isadora and her siblings became involved with move-

ment and dance early on, and taught the waltz and the mazurka to their

friends. Meanwhile, Isadora attended sessions in gymnastics, a vigor-

ous and increasingly fashionable form of exercise, free of the constraints

of corsets or heavy clothing. The contrast with the rigidly formal

balletic style that she and her family saw on the stages of local theaters

was marked, and held more appeal for her. Isadora was still in her

teens when she and her sister Elisabeth were listed in the San

Francisco directory as teachers of dance, an occupation in which their

brothers soon joined them. The Duncans loved to perform, and soon

Isadora was part of a small family variety show touring California.

It did not take Duncan long to combine her love of expressive

movement with the relative freedom offered to the female body by

gymnastics. Delsarte’s movement vocabulary, which sought exact

expressions of emotions and inner states through physical actions,

was much in fashion during the 1880s, and Duncan’s later dances

showed this influence in her use of a trained body, able to single out

and intensify a whole-body expression. Another influence from her

early years could be traced to the 1893 World Exhibition in Chicago.

There, the Art Nouveau displays made a strong impression on her

DUNGEONS AND DRAGONS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

774

Isadora Duncan

imagination, and her dances later reflected the organic lines and

swirls that characterized Art Nouveau design.

After two years with a touring company and many excursions

into acting, singing, and dancing, Isadora Duncan became bored with

a theatrical environment which did not allow for the expression of her

individuality. She began to develop her own style and work on a

dance repertoire, and on March 14, 1899 she gave a solo performance

in New York in which she danced to poetry. Her bare arms and legs

caused some ladies to leave the auditorium, but those that remained

were entranced by the classical purity of her art. Duncan had found

her way out of the ‘‘low art’’ of club and theater dance to a new, high

form of dancing, whose form was influenced by Greek statues,

classical music, and poetry, and whose physical disciplines had their

roots in calisthenics. Her favorite poet, Walt Whitman, inspired her to

use her body as the instrument of a new poetry.

Later the same year, declaring the dedication of her life to Art

and Beauty, Isadora Duncan embarked on travelling the world, taking

her art to the sophisticated centers of 1920s bohemia: London, Paris,

Berlin, and Moscow. She caused a sensation wherever she went and

became an inspiration to poets, musicians, and painters, taking a

succession of lovers from among their ranks. Among her most famous

liaisons was that with the famed English stage designer of the time,

Gordon Craig, and she married the Russian poet Essenin.

In performance, Duncan was a euphoric dancer of sensual

dreams. A free-thinking woman and an artistic visionary, she focused

on the concerns of her time and translated them into movement,

deserting the relatively static displays of the period for generous,

sensitive dances in which she brought the accompanying music to

three-dimensional life. To music that ranged from Schubert through

Wagner to Chopin, she would fill the stage, her voluptuous body

dressed in a Greek-style tunic, or veils, expressing her feelings and

emotions through movement, able to communicate her presence to

the audience. The influence of this style, while considerable, was

concealed within the images of free, gracious, sensuous, and powerful

dancing that mesmerized her audience through its simplicity—the

Duncan approach could not be studied through preserved step pat-

terns, finished dances, or her writings.

Parallel with her position as an exponent of a new form of dance,

Duncan became an early symbol of personal women’s liberation, and

of general political freedom. In her writings she attacked the constraints

imposed on women, and exercised none in the conduct of her

permissive sexual life. She even danced while pregnant. Although

Duncan advocated the equality of both men and women in a new

morality, she did not perceive her own work as erotic: her freedom

was the freedom of the naked Greeks. Her audiences appreciated her

in different ways, some for her purity of expression, others undoubt-

edly with prurient interest as they waited (successfully) for her breasts

to fall out of her loose costume. It was not only gender politics that

excited her: she saw Communism as a way forward, and offered her

services to the Russian republic.

After a wandering life filled with ideas, achievements, personal

tragedies such as the death of her children, many men, and few places

to call home, Duncan died in a horrible yet appropriately flamboyant

way. Her trademark flowing silk scarf became entangled in the

wheels of a Bugatti sports car, causing a fatal broken spine.

The schools Duncan founded did not do very well, and few of her

adopted daughters took on the mantle of teaching the next generation.

Ballet masters dismissed her dances of free expression for their lack

of technique, and saw Duncan herself as a mere amateur. Her writings

were revived in the back-to-nature days of the 1970s, but had very

little sustained influence on the further development of modern

dance, but her powerful, free, and beautiful image has stayed with

dancers all over the world. Isadora is cemented as one of the

great feminine myths of the twentieth century, and was played by

Vanessa Redgrave in Karel Reisz’s 1969 film, The Loves of Isadora

(aka Isadora).

—Petra Kuppers

F

URTHER READING:

Daly, Ann. Done into Dance. Isadora Duncan in America. Blooming-

ton, Indiana, Indiana University Press, 1995.

Duncan, Isadora. The Art of Dance, edited by Sheldon Cheney. New

York, Theatre Arts Books, 1977.

Dungeons and Dragons

Dungeons and Dragons, more commonly and affectionately

known by its players as D&D, is the first and most famous of the

DUNKIN’ DONUTSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

775

fantasy role playing games (RPGs). Dungeons and Dragons is based

on traditional fantasy literature such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the

Rings trilogy. In the game, players cast themselves as imaginary

characters and go on imaginary adventures in a fantasy world of their

own design. Gaining popularity in the 1980s, D&D perhaps symbol-

ized the existential angst of a youth worried about inheriting a world

that was not their own.

In D&D, the Dungeon Master (DM) creates an imaginary world

full of monsters, dangers, and magic. Character-players then journey

through the DM’s world fighting battles, stealing treasures, or outwit-

ting monsters. The game is played verbally with conflicts settled by a

role of dice.

The players create characters for themselves based on a variety

of traits; strength, intelligence, and endurance are three key qualities.

The level of each trait that a character acquires is determined by the

roll of a dice before the game starts. Players can choose a variety of

roles for their characters such as thief, assassin, fighter, and cleric,

among others. Players can also choose the race for each character;

choices include humans, elves, and dwarfs. The game can be played

with varying degrees of complexity, depending on the experience of

the players and the Dungeon Master.

D&D was originally created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson.

They simplified the game, moving from the action of regiments to the

actions of individual fighters to create D&D. The first two print runs

of the game sold out. TSR, Inc. produced the Dungeons and Dragons

series starting in 1974. When D&D became very popular, especially

among the college crowd, a whole industry arose. TSR published

supplementary guides, including books of monsters and demigods

based on world myths and legends. Dragon Magazine and other

magazines devoted to gaming campaigns hit the newsstands. TSR

also published book lines like Forgotten Realms and Dragonlance

that had their origins in the games. Other fantasy authors incorporated

D&D motifs into novels as well.

In addition to being popular, D&D was also very controversial.

Campaigns can take hours, days, and sometimes even weeks to finish.

Tales arose of promising college students flunking out of school

because they spent all their time playing D&D. Other accusations

against the game were even harsher. Many people accused it of

instilling violence in the minds of the players; others said it produced

suicidal tendencies, especially when a player over-identified with a

character that had been killed during a game. Organizations and

religious groups accused the game of being Satanic since it sometimes

dealt with demons and conjuring devils. The campaign against

Dungeons and Dragons eventually spawned a group known as BADD,

(Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons). The group was founded by

a woman who claimed that her child killed himself because of the

game. The game took another publicity hit when the television movie

Mazes and Monsters came out. The movie was based on an account of

how D&D players took their role playing too seriously and started

acting out the campaigns in the tunnels and sewers of their college.

Proponents of the games fought back, arguing that a game alone

could not be the main cause of any psychological problems certain

players were exhibiting. Advocates emphasized the notion that the

game helped stimulate imagination and problem solving skills. Oth-

ers claimed it helped vent violent feelings through imaginary play

instead of acting such feelings out.

The debates about D&D generated negative publicity for the

games and many concerned parents did not want their children

playing. TSR continued its own positive publicity, and they began to

tone down some of their manuals and game-based fiction, especially

the parts that dealt with demons and conjuring. Eventually, new

technologies helped D&D and other role playing games recover some

popularity. One player made an interactive on-line computer version

of the game called a M.U.D., a Multi-User Dungeon. MUDs became

the place where computer aficionados went to play.

The greatest blow against TSR and Dungeons and Dragons came

in the 1990s, not from concerned parents but from bad business. TSR

had its book contracts through Random House, which distributed the

books through chain book stores. When the chain book stores stopped

carrying the books, they tore off the covers and dumped them. Instead

of a check from Random House, TSR received a huge bill they were

not prepared to pay. In 1997, Wizards of the Coast, the producers of

Magic: The Gathering Cards, another type of game playing, bought

them out. Wizards of the Coast revived many TSR projects, including

Dragon Magazine and D&D, in an attempt to keep the game alive. In

the year following the buyout, the gaming industry started to swing

back to RPGs and away from card games. Indeed, the future of RPGs

continues to look promising.

—P. Andrew Miller

F

URTHER READING:

Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Players Handbook. 2nd Edition.

Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, TSR, Inc. 1989.

Gygax, Gary. Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Players Handbook.

Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, TSR, Inc. 1978.

Martin, Daniel, and Gary Alan Fine. ‘‘Satanic Cults, Satanic Play: Is

’Dungeons and Dragons’ a Breeding Ground for the Devil?’’ In

The Satanism Scare, edited by James T. Richardson, Joel Best, and

David G. Bromley. New York, Aldine De Gruyter, 1991.

Dunkin’ Donuts

Associated with the working man’s coffee break, Dunkin’

Donuts catered to Americans’ desire for a strong cup of coffee and a

sweet treat long before Starbucks’ coffee shops first started selling

fancy pastries and gourmet coffee. Started in 1950, Dunkin’ Donuts

was ranked by Entrepreneur and Franchise Times magazines as one

of the top franchises of 1998, when it was operating over 3,700 stores

in 21 countries worldwide. In addition to coffee and doughnuts, the

retail chain, with its ubiquitous pink and orange signs, sells muffins,

bagels, and other bakery products. The world’s largest chain of coffee

and doughnut shops in the 1990s, founder William Rosenberg devel-

oped the chain from a string of canteen trucks after World War II. He

bequeathed the business to his son Robert, who had managed dough-

nut shops during summer breaks from Harvard Business School. In

1989, Allied Domecq PLC, a British-based food and beverage con-

glomerate, whose portfolio of American quick service restaurants

also includes Baskin-Robbins ice cream stores and Togo’s sandwich

shops, acquired Dunkin’ Donuts. Dunkin’ Donuts is Allied Domecq’s

flagship American operation, accounting for 70 percent of its total

United States sales of $2.5 billion in 1998.

—Courtney Bennett

DUNNE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

776

FURTHER READING:

Allen, Robin Lee. ‘‘It’s Time to Leave the Donuts: Dunkin’s Rosenberg

Retires.’’ Nation’s Restaurant News. June 2, 1998.

Carrol, F. Food Business Reference on Donut Shops and Other Pastry

Shops. N.p., Prosperity and Profit Unlimited, 1984.

Dunne, Finley Peter

See Mr. Dooley

Dunne, Irene (1898-1990)

Dubbed ‘‘The First Lady of Hollywood’’ in her day, her persona

always charming, sweet, resourceful, and dignified, Irene Dunne

evokes nostalgia for an era of romantic escape from harsh reality.

Kentucky-born Dunne carved a successful career in musical comedy

before entering films in 1930 (she starred as Magnolia in Show Boat,

1936), and was in the first rank of sympathetic screen heroines

throughout the 1930s. She suffered gracefully through several senti-

mental, sometimes tragic, love stories, famously including Back

Street (1932), Magnificent Obsession (1935), and Love Affair (1939),

but also revealed an exceptional aptitude for comedy in such films as

Theodora Goes Wild (1936) and The Awful Truth (1937). She

received her fifth Oscar nomination for I Remember Mama (1947)

which, together with Life with Father (1948), marked her last big

successes. Dunne retired from the screen to devote herself to civic,

philanthropic, and Republican political causes. Also a prolific radio

and television performer, in 1985 she was honored at the Kennedy

Center for her achievement in the performing arts.

—Robyn Karney

F

URTHER READING:

Schultz, Margie. Irene Dunne: A Bio-Bibliography. Connecticut,

Greenwood Press, 1991.

Thomson, David. A Biographical Dictionary of Film. New York,

Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Dural, Stanley, Jr.

See Buckwheat Zydeco

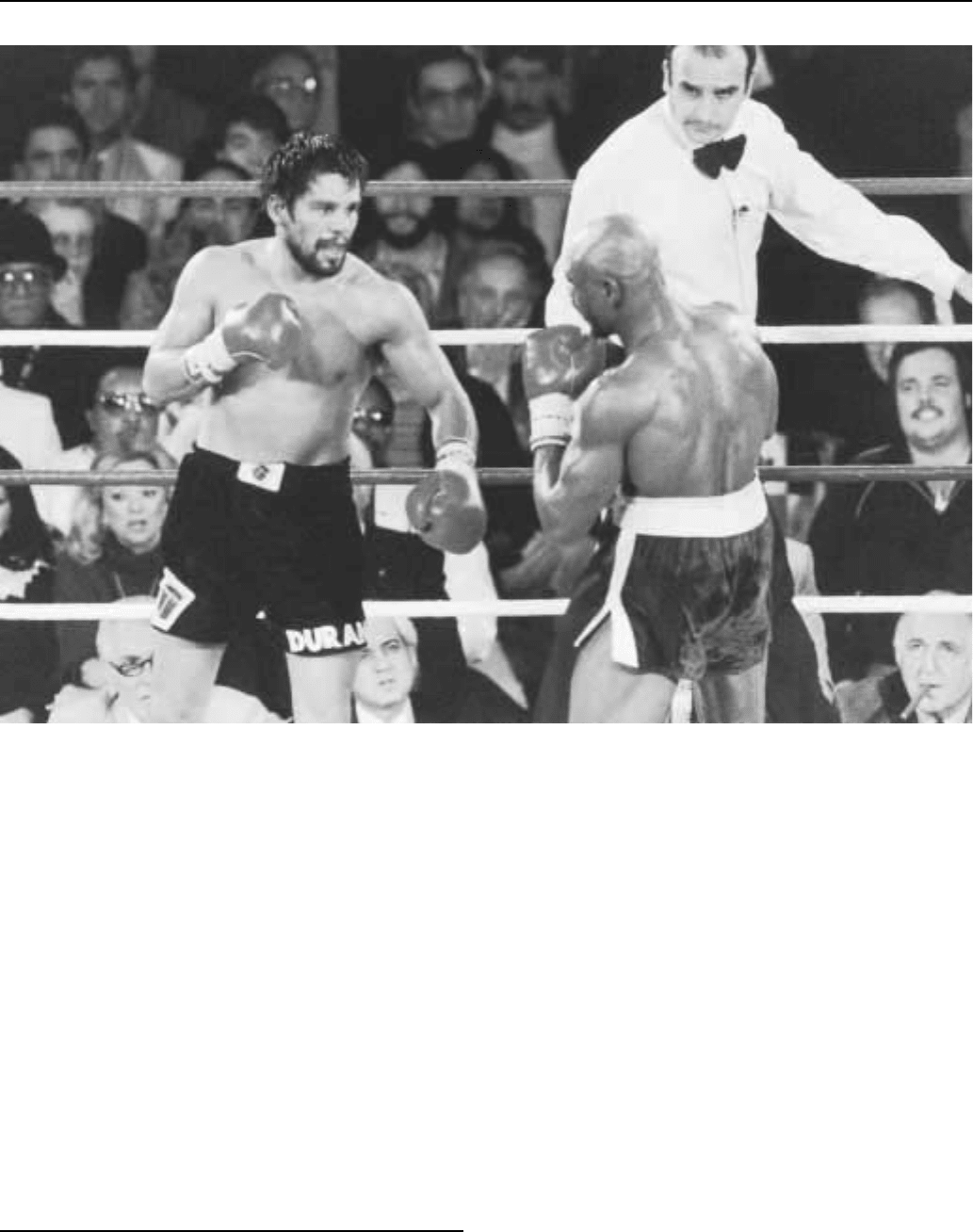

Durán, Roberto (1951—)

Roberto ‘‘Manos de Piedra’’ (Stone Hands) Durán is one of the

few boxers in history to win world boxing titles in four different

weight divisions—lightweight, welterweight, junior middleweight,

and middleweight. Born in the poverty-stricken barrio of Chorillo,

Panama, on June 16, 1951, Durán only received a third-grade educa-

tion, after which he became a ‘‘street kid,’’ making his living selling

newspapers, shining shoes, committing petty theft, and doing whatev-

er else he could to earn some money for his mother and eight siblings.

Clearly one of the most talented boxers to enter the ring, Durán is also

well known for his contributions to the poor and his loyalty to family

and friends.

Durán eventually followed an older brother into boxing and

turned professional at the age of 16. A wealthy ex-athlete, Carlos

Eleta, befriended Durán and arranged for his training with one of the

best tacticians in American boxing, Ray Arcel, who taught Durán to

become ambidextrous in the ring. Arcel also hired Freddie Brown, a

trainer for 12 world champions, to work with Durán.

All of the attention paid off in 1972, when Durán won his first

title as a lightweight against Ken Buchanan. Durán defended his title

11 times and won 70 of his first 71 fights. He reigned as a national

hero in Panama, where he fed the poor, gave to numerous charitable

causes, and was more than generous to his family. He made sure, in

addition, to employ residents from his old barrio on his estate and in

his various enterprises. In 1975, the most famous (or infamous)

promoter in the fight game took on Durán—Don King. Durán’s

appetite for food forced him to move up in the weight divisions, as did

the larger prizes that were offered through the assistance of King. One

of the highlights of his career was his victory over one of the greatest

boxers of all time, Sugar Ray Leonard in 1980 for the WBC (World

Boxing Confederation) welterweight championship.

After this pinnacle of success, Durán gorged himself and could

not control his weight before the Leonard rematch; he trained in a

rubber corset and took diuretics before the weigh in, but soon stuffed

himself with steaks and, by the time of the match, was too bloated and

exhausted from the desperate training to put up a credible fight. Durán

walked out of the ring in the eighth round, exclaiming a now infamous

phrase: ‘‘No más . . . no peleo más’’ (No more . . . I won’t fight

anymore). Durán explained to the press that he had stomach cramps,

but his reputation was sullied in the world sports press and among

late-night television hosts, who satirized his surrender mercilessly.

Durán, nevertheless, had earned $3 million for the fight, but had lost

Brown and Arcel from his team. In Panama, he was shunned and all of

his acts of charity and goodwill were quickly forgotten.

In 1983, Durán made a comeback by winning the junior middle-

weight title from Davey Moore at Madison Square Garden, but soon

lost a round of bouts. He came back once again to win the WBC

middleweight title in 1989, after 22 years in the ring. Durán continued

to fight into his forties, and became known as ‘‘the old man of boxing.’’

—Nicolás Kanellos

F

URTHER READING:

Tardiff, Joseph T., and L. Mpho Mabunda, editors. Dictionary of

Hispanic Biography. Detroit, Gale, 1996.

Durbin, Deanna (1921—)

Deanna Durbin’s overnight rise to fame as an adolescent movie

star began with Three Smart Girls (1936) and One Hundred Men and

a Girl (1937). Her box office success was widely credited with saving

Universal Studios from bankruptcy. Fans and critics alike were taken

by her mature soprano voice and her wholesome, yet feisty, charac-

ters. Born Edna Mae Durbin in Winnipeg, Canada, she was dubbed

‘‘America’s Kid Sister’’ and in 1939 was awarded a miniature Oscar.

Although praised for her successful transition to adult roles in the

1940s, her popularity declined. In 1948, she permanently traded her

DUROCHERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

777

Roberto Durán (left) in a match against Marvelous Marvin Hagler, 1983.

13-year, 21-film career for a private life in France with her third

husband, French filmmaker Charles David, and their family.

—Kelly Schrum

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Deanna Durbin.’’ Current Biography. New York, H. W. Wilson

Co., 1941, 246-248.

Scheiner, Georganne. ‘‘The Deanna Durbin Devotees: Fan Clubs and

Spectatorship.’’ Generations of Youth: Youth Cultures and Histo-

ry in Twentieth-Century America, edited by Joe Austin and

Michael Nevin Willard. New York, New York University Press,

1998, 81-94.

Shipman, David. ‘‘Nostalgia: Deanna Durbin.’’ Film and Filming.

December 1983, 24-27.

Zierold, Norman J. The Child Stars. London, MacDonald, 1965, 190.

Durocher, Leo (1905-1991)

Leo Durocher, states one baseball publication, “was squarely at

the center of some of the most exciting and controversial events in the

history of the game.” Durocher’s colorful and eventful baseball career

spanned nearly 50 years as a major league player, manager, coach,

and television commentator. But it was his tenure as a manager in

New York City from 1941 to 1955 that made him a national sports

celebrity and placed him at the heart of so many significant baseball

events. Baseball writer Roger Kahn fondly remembered that era

“when the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers ruled the world.” On the

field, Durocher managed both the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New

York Giants; was directly involved in the controversy surrounding the

game’s first black player, Jackie Robinson; and was a participant in

what many sports writers consider the greatest game in baseball

history—the 1951 final playoff between the Giants and the Dodgers.

Born in the industrial slums of West Springfield, Massachusetts,

the young Durocher worked in factories and hustled pool to make

money. He was suspended from high school for slapping a teacher

and never returned. He began playing baseball on a railroad company

team and made it to the major leagues in 1925. His playing career was

mediocre at best, and his hitting was weak, but his flashy and

acrobatic fielding was enough to make him an All-Star in 1936, 1938,

and 1940. Durocher played for two of the most celebrated teams of the

early twentieth century: in 1928 he spent his first full season in the

major leagues with the legendary New York Yankees, led by Babe

Ruth; and in 1934, he captained the St. Louis Cardinals, a team better

DUVALL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

778

Former Giants manager Leo Durocher with his son.

known as the “Gas House Gang.” Those boisterous Cardinals were a

hell-raising group that played hard on and off the field. Durocher and

the Cardinals won the 1934 World Series.

In 1939, Durocher became player-manager for the Brooklyn

Dodgers. He helped the Dodgers to a National League pennant in

1941 and, in what was perhaps his finest moment in baseball, stymied

a 1947 rebellion by some Dodgers players protesting the presence of

Jackie Robinson on the team. During spring training, Durocher

discovered that several Dodgers were circulating a petition vowing

they would never play on the same team as Robinson. Durocher called

the team together and told them that Robinson was a great player and

would help them to victory. He declared that, “He’s only the first,

boys, only the first! There are many more colored ballplayers coming

right behind him and they’re hungry, boys. They’re scratching and

diving. Unless you wake up, these colored ballplayers are going to run

you right out of the park. I don’t want to see your petition, I don’t want

to hear anything else. This meeting is over.”

But he never had the opportunity to manage Jackie Robinson. A

controversial figure, Durocher was suspended by the baseball com-

missioner for the entire 1947 season on the vague charge of moral

turpitude. He had been under suspicion for being too friendly with

New York gamblers and other shady characters, such as mobster

Bugsy Siegel; and he had married movie actress Laraine Day in

Mexico before her California divorce was final. Already a twice-

divorced Catholic, Durocher had made enemies of powerful Roman

Catholic Church officials and politicians in Brooklyn. Thus, public

pressure, and the threat of keeping Catholic youth organizations from

the ballpark, forced Durocher’s year-long sabbatical.

When he returned in 1948, the Dodgers faltered and he was fired

early in the season. To the amazement of New York fans, however, he

was immediately hired as manager of the cross-town rival, the New

York Giants. He was also managing the Giants at the time of the

legendary 1951 playoff game with the Brooklyn Dodgers on 12

August 1951. The Giants, trailing the first-place Dodgers by 13½

games, tied their rivals by season’s end and forced a three-game

playoff. In game three, the Dodgers were leading 4-1 in the final

inning when Bobby Thomson hit a dramatic home run to win the

pennant for the Durocher-led Giants. Durocher took the team to two

World Series, winning the 1954 contest, but despite these successes,

the Giants finished a weak third in 1955 and Durcoher was fired at the

end of the season.

After working as a television commentator and coaching for

several years with the Los Angeles Dodgers, Durocher returned to

manage the Chicago Cubs in 1966. The Cubs had been one of the

worst teams in baseball for nearly three decades, but Durocher helped

turn them into winners. In 1969, his Cubs held a 9 ½-game lead in

early August, but they folded in the last two months of the season and

lost the National League pennant to the New York Mets. Durocher

was criticized for not resting his players during the humid days of

summer. He left the Cubs in 1972 and managed one more season with

the Houston Astros before retiring.

Leo Durocher remains among the all-time leaders in games

managed (3,740) and games won (2,010). In addition, he is the only

baseball player cited in Bartlett’s Quotations. His quote, “Nice Guys

Finish Last,” is also the title of his autobiography, which he wrote

after leaving baseball. That renowned quotation was attributed to

Durocher in 1947 and referred to his opinion of then Giants manager

Mel Ott, whose team had been underachieving during the season.

“Leo the Lip,” as the irascible Durocher was called, maintained that

Ott and most of the Giants players were nice guys, but they would

never be winners because nice guys finish last.

—David E. Woodard

F

URTHER READING:

Durocher, Leo and Ed Linn. Nice Guys Finish Last. New York, Simon

& Schuster, 1975.

Hynd, Noel. The Giants of Polo Grounds: The Glorious Times of

Baseball’s New York Giants. New York, Doubleday, 1988.

Kahn, Roger. The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants,

And the Dodgers Ruled the World. New York, Ticknor &

Fields, 1993.

Neft, David and Richard Cohen, eds. The Sports Encyclopedia:

Baseball. 16

th

edition. New York, St. Martin’s Griffin, 1996.

Shatzkin, Mike, ed. The Ballplayers: Baseball’s Ultimate Biographi-

cal Reference. New York, Arbor House, William Morrow &

Company, 1990.

Thorn, John and Pete Palmer, eds. Total Baseball. 2

nd

edition. New

York, Warner Books, 1991.

Duvall, Robert (1931—)

Veteran American actor Robert Duvall has been an integral part

of a large portion of Hollywood cinema throughout his lengthy career,

thanks to his ability to metamorphose fully into each character he

plays. He is also a skilled director, producer, screenwriter, singer, and

songwriter. One of his most memorable roles is as Colonel Kilgore in

the 1979 Francis Ford Coppola film Apocalypse Now, in which he

uttered the classic line, ‘‘I love the smell of napalm in the morning.’’