Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DYERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

779

Duvall also won an Academy Award for best actor for his part as a

country singer in 1983’s Tender Mercies, for which he wrote and

performed some of the songs. In 1997 Duvall won critical plaudits

for The Apostle, a pet project that was a long time coming. He

wrote, directed, starred in, and funded the picture about a flawed

southern minister.

—Geri Speace

F

URTHER READING:

Duvall, Robert. ‘‘The ‘Apostle’ Speaks.’’ Newsweek. April 13,

1998, 60.

Moritz, Charles, editor. Current Biography Yearbook 1977. New

York, H.W. Wilson Co., 1977.

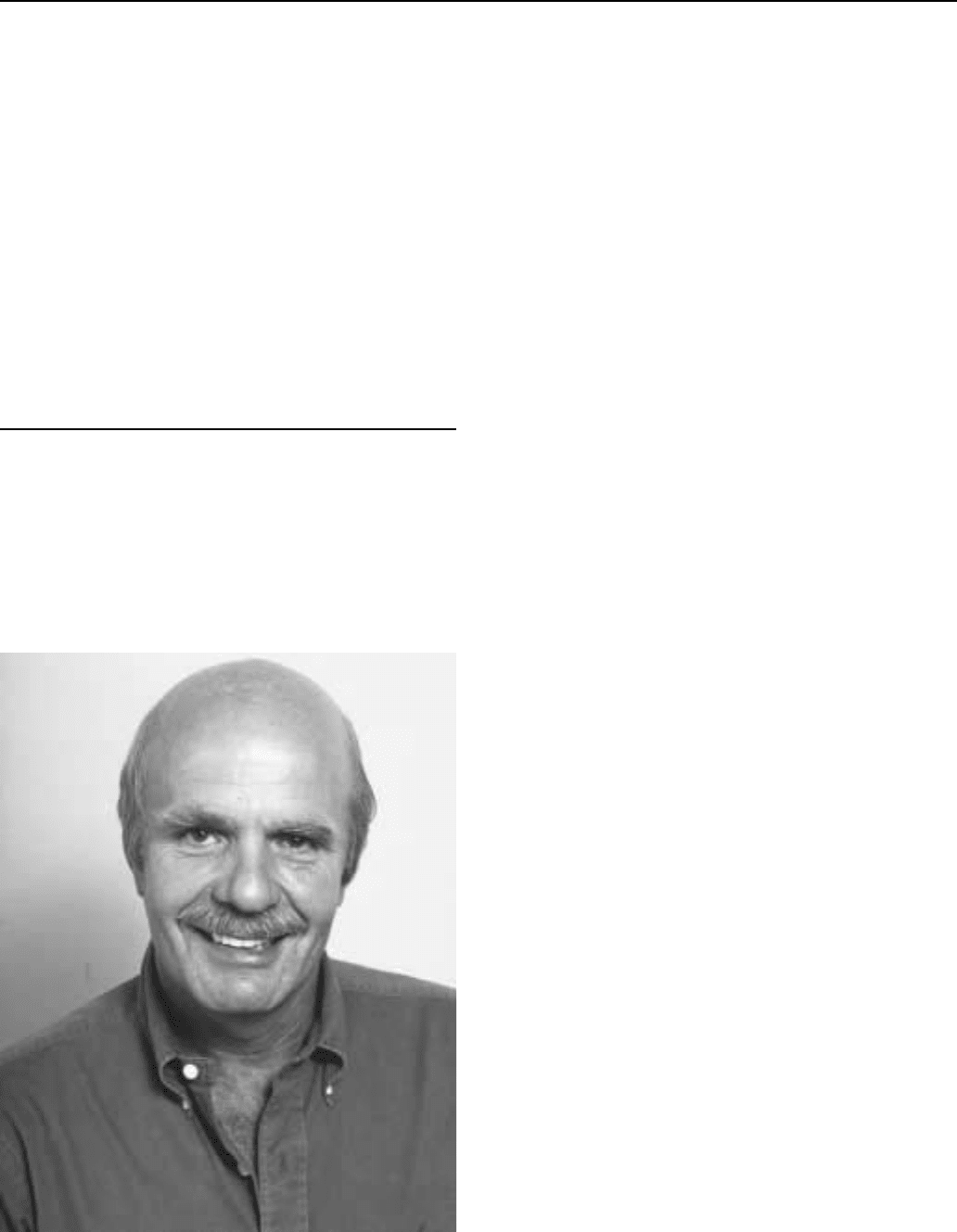

Dyer, Wayne (1940—)

Charismatic and camera-friendly, Wayne Dyer became well-

known after the phenomenally successful publication of his first best-

selling book, Your Erroneous Zones in 1976. From that time, he

became a constant proponent of such typically “New Age” concepts

as “living in the moment” and making “choices that bring us to a

higher awareness,” as he told a reporter for the St. Petersburg Times in

1994. Since Your Erroneous Zones, Dyer has used books, tapes, and

the broadcast media to his advantage, securing his position as a

Wayne Dyer

late-twentieth-century cultural icon, and a leading light in the areas of

motivation and self-awareness.

Wayne W. Dyer was born in Detroit, Michigan, and began his

professional career in Detroit as a high-school guidance counselor in

1965. In 1971, after earning a doctorate of education, he was

appointed a professor of counselor education at St. John’s University

in Jamaica, New York, and began contributing articles to professional

journals and co-authoring books on counseling with his colleague

John Vriend. These established his credentials in academia, while, at

the same time, he ran a lucrative private clinical psychology practice.

His lectures at St. John’s taught exercises in motivational speaking,

and his upbeat, positive message was very well-received; students

began bringing their friends to Dyer’s lectures, and he amassed a

small following.

News of these lectures intrigued a literary agent, who approach-

ed Dyer about the possibility of writing a book based on their ideas.

He agreed, and wrote Your Erroneous Zones, sales of which were

initially abysmal. Undaunted, its author bought up all the copies and,

quitting both his teaching position and his practice, set out on the road

with the books to make publishing and self-marketing history. In four

months, Dyer covered all of the contiguous United States, making

personal appearances at bookstores and giving radio and television

interviews. By the end of his journey, he had been a guest on

nationally televised talk shows and was interviewed by the likes of

Phil Donahue, Johnny Carson, and Merv Griffin.

Wayne Dyer’s status as a celebrity allowed him to publish more

books on the same theme, and to generate an audience for his informal

lecture tours. These tours cemented his following, and became the

basis for the many acclaimed, high-selling audiotape sets that he

recorded. His message offered something for everyone, since it was

not specific to either any religion, or any particular portion of society.

This was in contrast to self-help heroes such as Dale Carnegie and

Stephen Covey, whose philosophies were somewhat hemmed in by

their affiliations and concerns with the business and corporate worlds.

Dyer even resisted the New Age tag, warning his audience in one of

his tapes that the New Age phenomenon and its proponents were often

superficial and could be dangerously misleading.

While his books all offered variations on the same theme, that

theme became steadily more convoluted and esoteric as his career

continued, accruing a certain degree of mysticism to accompany his

pop psychology. In Real Magic (1993), for example, he discusses the

potential for spiritual experience, while Your Sacred Self (1996)

further expounds on the benefits of attaining a higher consciousness.

Having remarried in 1979, he and his wife were raising a family of

eight children throughout the 1980s, and his books largely recounted

experiences and anecdotes culled from his family life. In 1998 he

published Wisdom of the Ages, a collection of essays that reflected on

the essence of certain literary quotations.

Dyer often said that his own life was his own best example, and

much of his appeal can be attributed to his life experience, which he

used consistently as an entry point into his discussions and writings.

Many of his pre-teen years were spent in an orphanage, and although

he grew up to be successful, he was also profoundly unhappy until he

decided to take responsibility for his own life in the mid-1970s. The

fact that his ideas were based on the psychological mechanisms that

worked so well for him gave him his credibility among the consumers

of self-development media.

Although the book sales and attendance numbers at Dyer’s

lectures were a testament to his following, and his continued appear-

ance on talk shows throughout the 1980s kept him in the wider public

DYKES TO WATCH OUT FOR ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

780

eye, he had his share of critics. Interviewing him in a 1983 issue of

Life magazine, Campbell Geeslin suggests that Dyer’s message is “a

gospel in praise of the superficial” and that “Dyer is selling simplistic

solutions to life’s inevitable difficulties.” Wayne Dyer, who was his

own best advertisement in the late 1970s, turned out to be his own

saboteur in the early 1990s. While remaining a hugely successful

author, his increasingly mystical approach to his subject matter made

him less desirable as a guest on the talk-show circuit and, while still

visible, his voice and message no longer saturate the airwaves.

—Dan Coffey

F

URTHER READING:

Alim, Fahizah. “Breaking Free.” The Sacramento Bee. May 16, 1993.

Dyer, Wayne W. Real Magic. New York, HarperCollins, 1993.

———. Your Erroneous Zones. New York, HarperPerennial, 1991.

———. Your Sacred Self. New York, HarperCollins, 1996.

Geeslin, Campbell. “Dr. Wayne Dyer; Pulling Those Same Old

Strings With a New Book.” Life. April, 1983, 19-22.

Reynolds, Cynthia Furlong. “You Can Choose to Become a New

Person.” St. Petersburg Times. October 26, 1994.

Dykes to Watch Out For

In the mid-1980s lesbian cartoonist Alison Bechdel began to

create the family of lesbians who comprise her popular comic strip,

Dykes to Watch Out For. By the mid-1990s, the strip—the first

continuing lesbian cartoon—had been syndicated in over 50 lesbian,

gay, and alternative periodicals and had been published in more than

seven collections. Dykes to Watch Out For had become an institution.

The strip is a little like a soap opera, with a developing storyline,

and a lot like a peek behind the scenes of any lesbian community. The

cast of characters is a group of lesbian friends in a nameless mid-size

city in the United States. Just as in any real group of friends, pairings

change and priorities evolve, influenced by events both internal and

external. Much of the action takes place at Madwimmin Books, a

feminist bookstore owned by Jezanna, a no-nonsense lesbian entre-

preneur. Among the staff at Madwimmin are Mo, a lovable curmudg-

eon filled with leftist angst, and Lois, a butch rake with a girl in every

port. Their friends include Toni and Clarice, an accountant and lawyer

with a baby boy—however uncomfortably, they are upwardly mobile

and nuclear-family-bound. Lois lives in a group house with Ginger,

an academic, and Sparrow is a pagan spiritualist who works at a

battered women’s shelter.

These women, and the friends who ebb and flow around them,

form a diverse community. Through them, Bechdel pokes gentle fun

at the foibles of lesbians, be they politically earnest, promiscuous, or

pretentious. She also allows them to change as they experience the

events of the real world, mirroring the real changes that occur both

among lesbians and in the larger community. Just as traditional media

reflects the effects of phenomena on the larger culture, Dykes to

Watch Out For reflects lesbian culture. Presidential elections, the O.J.

Simpson trial, prozac, sado-masochism, transsexuality—all appear in

the panels of the comic strip, analyzed and digested by Bechdel’s

family of lesbians.

Bechdel calls her strip ‘‘half op-ed column and half endless

Victorian novel.’’ While her primary alter-ego is clearly Mo, the

anguished leftist, Bechdel does not take herself or her characters too

seriously. She occasionally has her characters break the ‘‘fourth

wall’’ and address her readers directly, or interact with each other as if

they are quite different characters performing in the strip. One of the

strip’s calendars shows a large panel of the ‘‘green room’’ where

characters display heretofore unseen personality traits as they wait for

their ‘‘entrance’’ onto the strip. In another strip, characters of color, a

Jewish character, and a disabled character bewail their token status in

the storyline.

It is a tribute to Bechdel’s skill as an artist and a writer that she

can bring her characters enough life to argue with her from the page.

Her drawings are clean yet complex, filled with subtle references and

in-jokes for her audience, and the dialogue is lively and incisive. In

fact, Bechdel’s work and the success of Dykes To Watch Out For

drew the attention of the mainstream press when Universal Press

Syndicate approached her with an offer that could have placed her in

the daily ‘‘funny papers.’’ Though their interest was exciting to

Bechdel, it only took a moment’s thought to realize that whittling

down her work to fit the narrow niche of the mainstream would have

changed her work beyond recognition. The title would have to go,

‘‘dykes’’ being far too controversial, and out of six main characters

only two would have been allowed to be lesbians. Unwilling to give

up her vision of a strip that reflected the realities of lesbian life,

Bechdel refused the offer and remained in the alternative press, where

her uncensored style was welcome.

Her strips, collections, and calendars have always been eagerly

awaited by her fans. In fact, the main dilemma for Bechdel’s readers

seems to be expressed by an urgent letter she received from a fan.

‘‘DO YOU HAVE ANY IDEA,’’ the reader wrote, ‘‘WHAT IT’S

LIKE TO HAVE A CRUSH ON A CARTOON CHARACTER?!!?’’

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Bechdel, Alison. The Indelible Alison Bechdel: Confessions, Comix,

and Miscellaneous Dykes to Watch Out For. Ithaca, New York,

Firebrand Books, 1998.

Rhoades, Heather. ‘‘Cartoonist to Watch Out For.’’ The Progressive.

Vol. 56, No. 4, April 1992, 13.

Dylan, Bob (1941—)

The most influential musician to emerge out of the social unrest

of the early 1960s, Bob Dylan dramatically expanded the aesthetic

and political boundaries of popular song. Recognized almost immedi-

ately as the voice of his generation, Dylan began his brilliant career by

performing blues, folk ballads, and his own topical compositions,

many of which addressed issues of racial injustice and protested

against the threat of nuclear war. By 1965 he transformed himself into

a rock star, the first of many metamorphoses he would undergo over

the next three decades. Mercurial, iconoclastic, and enigmatic, Dylan

variously presented himself as a poet, gospel singer, bluesman,

country musician, and minstrel, recording more than thirty albums

that would make him one of the major popular artists of the

twentieth century.

‘‘Dylan has invented himself. He’s made himself up from

scratch,’’ wrote playwright Sam Shepard. The point, Shepard sug-

gested, ‘‘isn’t to figure [Dylan] out but to take him in,’’ to use him ‘‘as

DYLANENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

781

Bob Dylan

a means to adventure.’’ Dylan began his extraordinary odyssey as

Robert Zimmerman, the son of Jewish merchants from Hibbing,

Minnesota, where he enjoyed a comfortable middle-class life. Al-

though he was bar mitzvahed, Dylan listened to prophets who were

unfamiliar to his parents. Little Richard, Elvis Presley, and Hank

Williams inspired the young guitar player, while the rebels James

Dean and Marlon Brando shaped the attitude he carried to the

University of Minnesota in 1959.

His days as a student were numbered. Having received an

assortment of Huddie ‘‘Leadbelly’’ Leadbetter’s recordings for gradua-

tion gifts, Dylan was more interested in music than his studies and

promptly matriculated to Dinkytown, a hip section of Minneapolis

renowned for its folk scene. It was here that he obtained a copy of

Woody Guthrie’s autobiography, Bound for Glory (1943), a book that

inspired him to learn the Dust Bowl balladeer’s compositions and to

perform them in local coffeehouses. By 1960, this nineteen-year-old

changed his name and adopted Guthrie’s nomadic ways, embarking

on a cross-country trip that ended in New York City early in 1961.

Dylan immersed himself in the bohemian culture of Greenwich

Village, where leftists old and new were participating in the folk

music revival. Pete Seeger, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Ralph Rinzler, and

scores of other young people enamored with folk music attended jam

sessions in Washington Square Park and gathered regularly to pay

homage to Guthrie, the movement’s patron saint. Hospitalized with

Huntington’s chorea, Guthrie made weekend visits to the East Or-

ange, New Jersey, home of Bob and Sidsell Gleason, where Dylan

temporarily resided. The two men established a warm relationship.

Disease had nearly destroyed Guthrie’s creative and communicative

abilities, but he managed to express his enthusiasm for his admirer.

When Dylan debuted at Gerde’s Folk City in April, 1961, he donned

one of his mentor’s old suits for the occasion.

A self-described ‘‘Woody Guthrie juke box,’’ Dylan recalled

that he was ‘‘completely taken over by his spirit,’’ a claim to which

his self-titled album (1962), attests. Released soon after he was signed

to Columbia Records by John Hammond, this collection of folk

standards and two originals established Dylan’s credentials as an

authentic traditional artist, and as a nasal-voiced, road-weary traveler

who had hoboed for most of his young life. The album included the

poignant ‘‘Song to Woody,’’ a ballad written to the tune of Guthrie’s

‘‘1913 Massacre’’ that musically, stylistically, and lyrically declared

Dylan’s intent to carry his hero’s mantle. Cover versions of songs by

bluesmen Blind Lemon Jefferson and Bukka White placed Dylan

firmly in the folk tradition as did a 1961 press interview, during which

he claimed to have played with Jefferson and the Texas songster

Mance Lipscomb.

Bored with the predictability and sheltered nature of his middle-

class life, Dylan fabricated a past full of hard traveling and hard

living. If, like his fellow baby boomers, his life was smothered by

relative affluence and haunted by the specter of nuclear war, his ersatz

travels were filled with adventure and possibility. But if Dylan

responded to his generation’s ennui and malaise, he also began to

absorb and shape its politics. ‘‘Whether he liked it or not, Dylan sang

for us,’’ wrote the former president of Students for a Democratic

Society, Todd Gitlin. ‘‘We followed his career as if he were singing

our song; we got in the habit of asking where he was taking us next.’’

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) was born out of his emerg-

ing political consciousness. Perhaps the most stinging indictment of

the United States government ever released by the commercial

recording industry, ‘‘Masters of War’’ condemned the men who

produce weapons of mass destruction and warned them that even the

most benevolent God would not absolve their transgressions. The

politics of Freewheelin’ did not stop here. ‘‘Oxford Town’’ mocked

segregation at the University of Mississippi; ‘‘A Hard Rain’s A-

Gonna Fall’’ imagined a stark and terrifying post-nuclear landscape;

and ‘‘Blowin’ in the Wind,’’ which became a hit for Peter, Paul and

Mary, was a simple, though poetic, call for racial harmony. After

becoming the star of the 1963 Newport Folk Festival, Dylan actively

supported a number of political causes, performing at a voter registra-

tion rally in Mississippi and at the March on Washington that

summer. Meanwhile, the title track for his third album, The Times

They Are A-Changin’ (1964), furnished the anthem for a generation

dedicated to transforming the social order.

Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964) suggested, however, that the

artist was moving in new directions. Bitter love songs such as ‘‘It

Ain’t Me Babe’’ replaced the moralism of Freewheelin’ and Times,

while ‘‘Chimes of Freedom’’ cloaked its social concerns beneath a

virtuosic lyricism. Both the album and Dylan’s promotion of it at the

1964 Newport Festival were poorly received by members of the folk

press, many of whom opined that their hero’s preoccupation with

aesthetics forsook his political commitment. Their accusations were

not unfounded. Unwilling to be shackled with the duties of generational

spokesman, Dylan publicly renounced his involvement with the New

DYLAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

782

Left and, after shedding his denim shirt for black leather and sunglass-

es, repackaged himself as a poet and rock star.

By the end of 1965, perhaps the most important year in Dylan’s

career, the transformation was complete. Following the release of

Bringing It All Back Home that March, Dylan embarked on a tour of

England where he was met by transfixed crowds, screaming girls, and

adoring musicians. D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary film Don’t Look

Back (1967) chronicles the tour, presenting an increasingly arrogant

artist who sounded more like an existentialist than a proponent of civil

rights. In his interactions with the press, an irreverent Dylan attacked

those who tried to categorize and explain his art. In fact, his most

recent material seemed to question the ability of language to convey a

sense of reality. Rather than writing topical songs, he assailed the

social order by intimating that it was unreal, absurd, a mere construc-

tion of language. Home’s ‘‘Mr. Tambourine Man’’ (which the Byrds

successfully covered in 1965) suggested that drugs may have been

helping Dylan alter his own private reality, but the apocalyptic images

encountered by the bizarre characters who traveled Highway 61

Revisited (1965)—Napoleon in rags, Einstein disguised as Robin

Hood, and Mr. Jones—insinuated that an unjust present could only be

transcended by the act of artistic creation itself.

To be sure, Dylan’s complex, poetic lyrics altered the face of pop

music and legitimated the genre as an art form. When Bruce Springsteen

inducted Dylan into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, he

recalled that when he first heard ‘‘Like a Rolling Stone,’’ it ‘‘sounded

like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind.’’ The six-minute

single redefined the limits of popular song, declaring, Springsteen

later recalled, that ‘‘everything’’—aesthetics, politics, power, and

perhaps reality itself—‘‘was up for grabs.’’

Those who followed Dylan’s career closely should not have

been surprised when he turned his back on the folk revival at Newport

in 1965. The breaking off of his romantic relationship with Joan Baez,

his work on a collection of poems entitled Tarantula (eventually

published in 1971), his arcane lyrics, and his interest in the musical

arrangements of the Beatles, whom he had met on his British tour, all

pointed to his intention to leave the movement. Nevertheless, his

followers were shocked when Dylan appeared with an electric guitar.

Among the stalwarts who suggested that rock-and-roll musicians had

sold out to commercial interests, Seeger was rumored to have been so

outraged that he tried to cut the power supply. The audience nearly

booed Dylan from the stage. Although shaken, Dylan remained

resolute about his artistic decision. After meeting The Band (then the

Hawks) in the summer of 1965, he took his electric show on a tour of

England, during which he continued to incur the wrath of folk purists.

This reaction—as well as the stunning music that Dylan and The Band

produced—is documented on Live 1966 (released in 1998). Recorded

at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, this concert included a riveting

acoustic set which ultimately yielded to a full-blown rock show,

where Dylan’s voice and the masterful playing of his musicians

soared above the audience’s cries of betrayal.

Exhausted from the tour, Dylan returned to the United States,

where, after sustaining serious injury in a motorcycle accident, he

repaired to his home in Woodstock, New York. The silence of his

convalescence ended in the summer of 1967, when he and the Band

initiated a five-month jam session, most of which was released as the

critically acclaimed Basement Tapes (1975). The search for personal

redemption (‘‘I Shall Be Released’’), a sense of disillusionment and

abandonment (‘‘Tears of Rage’’), and a persistent existential angst

(‘‘Too Much of Nothing’’), remained prominent themes, but if the

Dylan of 1966 was trying to inter the musical past, the Basement

Dylan exhumed it. Dock Boggs, Clarence Ashley, and Jefferson,

traditional musicians whom Dylan encountered on the Folkways

Anthology of American Folk Music, seemed to have a palpable

presence on these recordings.

The Basement Tapes provide a segue between the modernism of

Blonde on Blonde (1966) and John Wesley Harding (1968), the first

album to appear after the accident. Replete with Biblical allusions,

Harding was a largely acoustic collection of parables and allegories,

one of which, ‘‘All Along the Watchtower,’’ became a standard in

Jimi Hendrix’s repertoire. But if the children of Woodstock continued

to embrace one of upstate New York’s most famous residents, the

artist himself seemed to be far removed from the Summer of Love. In

the same year that flower children frolicked in the rain and mud,

Dylan traveled south to record Nashville Skyline (1969), a collection

of country-tinged love songs that included a duet with Johnny Cash.

The man who began his career with protest songs ended the turbulent

1960s by embracing the form that such artists as Merle Haggard used

to condemn the anti-war movement.

The albums that carried Dylan into the 1970s showed little of the

genius that characterized his earlier work. The soundtrack to Pat

Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), a film in which Dylan played a bit

part, was notable for the inclusion of ‘‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,’’

a song later covered by Eric Clapton and Guns ‘n’ Roses. Before the

Flood (1974), a live album recorded with The Band, suggested that

Dylan was perhaps undergoing a creative renaissance, an assessment

that Blood on the Tracks (1975) confirmed. Here again were songs of

love, but crisp acoustic guitar, wailing harmonica, and a voice filled

with doubt and disappointment convey the pain, anguish, and longing

of ‘‘Tangled Up in Blue’’ and ‘‘Shelter from the Storm’’ with

remarkable weight and precision.

Desire (1976) indicated a renewed interest in politics. ‘‘Hurri-

cane,’’ the lengthy centerpiece, was the angriest song Dylan had

recorded since ‘‘Masters of War.’’ Co-written with Jacques Levy, this

fierce narrative impugned the American justice system by consider-

ing the murder trial of former professional boxer Rubin ‘‘Hurricane’’

Carter. Contending that Carter’s trial had been conducted unfairly,

Dylan publicized the jailed athlete’s case by marshaling the forces of

his Rolling Thunder Revue, a melange of some seventy artists—Baez,

Shepard, Elliot, and Allen Ginsberg among them—that toured the

States under Dylan’s direction. Dylan, who performed most of the

shows with his face covered in white pancake make up, designated

appearances in Madison Square Garden and the Astrodome as bene-

fits for Carter. Although the Revue’s efforts may have played a part in

convincing a New Jersey court to throw out Carter’s first conviction,

the boxer was found guilty a second time. Hard Rain (1976) provides

a sampling of the dramatic ways that Dylan rearranged his music

during the tour.

After the unremarkable Street-Legal (1978), Dylan chose a path

previously untrodden: the artist who spent much of the early 1970s

exploring his Jewish roots suddenly became a born again Christian.

Fans and critics had little tolerance for the musician’s choice, particu-

larly when he proselytized at concerts and refused to play his better-

known songs. The dogmatic lyrics may have made audiences uneasy,

but the music on Slow Train Coming (1979), Saved (1980), and Shot

of Love (1981) was triumphant and exhilarating. Backed by powerful

gospel arrangements, Dylan sings with a passion that convinces the

congregation that he had finally found his direction home. ‘‘Gotta

Serve Somebody,’’ the single from Train, earned Dylan his first

Grammy Award.

DYNASTYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

783

Infidels (1983) explored both political and spiritual issues, but

perhaps because it eschewed the religious fanaticism of his previous

efforts, it received warm praise from critics. Indeed, when such songs

as ‘‘Jokerman,’’ ‘‘License to Kill,’’ and ‘‘I and I,’’ are heard

alongside ‘‘Blind Willie McTell’’ and ‘‘Foot of Pride,’’ both of

which were released on The Bootleg Series, Volumes 1-3 (1991),

these sessions rate among the most innovative of Dylan’s career.

If Dylan’s commitment to Christianity had not faded on Infidels,

it was clear he had change a of heart when, on Empire Burlesque

(1985), he proclaimed that he ‘‘never could learn to drink that blood

and call it wine.’’ That same year he released Biograph, a retrospec-

tive of his career that included much previously unreleased material

and initiated the ‘‘boxed-set’’ format to the recording industry. With

his popularity again peaking, he participated in efforts to alleviate

famine in Ethiopia, joining the chorus of U.S.A. for Africa to record

‘‘We Are the World’’ and issuing a ragged performance at the Live

Aid Concert in Philadelphia. Political commentary extended into the

1990s. When he accepted a Grammy for lifetime achievement during

1991 Gulf War, he performed ‘‘Masters of War.’’

Although Dylan released lackluster studio albums in the mid-

1980s, he launched separate but noteworthy tours with Tom Petty and

the Heartbreakers and the Grateful Dead. Perhaps his most interesting

work from this period came as a member of the Traveling Wilburys, a

group comprised of Petty, George Harrison, Roy Orbison, and Jeff

Lynne. Released in 1988, the first of the Wilburys two albums

included the foot-tapping singles ‘‘Handle Me with Care’’ and ‘‘End

of the Line.’’ Dylan capped the 1980s with the critically acclaimed

Oh Mercy (1989), which included the socially conscious ‘‘Political

World’’ as well as ‘‘What Was It You Wanted,’’ a song that recalled

the bitterness of such earlier compositions as ‘‘Don’t Think Twice,

It’s All Right.’’

His fourth decade of recording brought accolades and continued

success. In October 1992, a panoply of artists including Harrison,

Cash, Petty, Lou Reed, and Neil Young assembled at Madison Square

Garden to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Dylan’s first album.

When the honoree opened his own set with ‘‘Song for Woody,’’ he

indicated that his career had come full circle. To be sure, his next two

albums returned to his roots: Good As I Been to You (1992) and World

Gone Wrong (1993) were both collections of traditional folk songs.

Because these releases contained no new material, critics opined that

Dylan’s creative powers were again on the wane. Their diagnosis was

premature. In 1997, this man who once issued a resonant challenge to

the American political system was recognized as one of the nation’s

most important artists when he was feted at the Kennedy Center

Honors. Soon thereafter he experienced a life-threatening illness and

responded with the Grammy-winning Time Out of Mind (1997). Here

the aging Dylan tried to come to terms with the emptiness of love and

the limits of his own humanity. ‘‘The shadows are falling and I’ve

been here all day,’’ he sings in ‘‘Not Dark Yet.’’ ‘‘It’s too hot to sleep

and time is running away.’’ The hobo’s travels had not yet ended, but

he was now worried about ‘‘Tryin’ to get to heaven before they closed

the door.’’

Dylan’s career had not yet ended, but the photograph that

appeared on the inside cover of the Time Out of Mind compact disc

box proclaimed a sense of closure. Shot from the shoulders up, a

corpse-like Dylan stares into the camera, the soft focus connoting an

elusiveness, his pale, worn face suggesting a weariness, his eyes

glistening with the sadness of experience yet not devoid of hope, his

riverboat minstrel costume, complete with string tie, underscoring the

timelessness so powerfully communicated by the soulful and battered

vocal performance rendered on the album. As a new generation

embraced him, as his son, Jacob, began his own recording career with

the Wallflowers, Dylan had, like the hard-traveling minstrel he

emulated, become the progenitor of the cultural and musical tradi-

tions he so carefully studied. His remarkable body of work and

enigmatic persona had, in effect, delivered him out of time, had

elevated him to the status of national myth. Nearly forty years after his

first record, Dylan continued to provide audiences with a ‘‘means

to adventure.’’

—Bryan Garman

F

URTHER READING:

Cantwell, Robert. When We Were Good: The Folk Revival. Cam-

bridge, Harvard University Press, 1996.

Garman, Bryan. A Race of Singers: Making an American Working

Class Hero. Forthcoming.

Gitlin, Todd. The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. New York,

Bantam, 1987.

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades: A Biography. New

York, Summit Books, 1991.

Marcus, Greil. Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes.

New York, Henry Holt, 1997.

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob

Dylan. New York, Beech Tree Books, 1986.

Shepard, Sam. Rolling Thunder Logbook. New York, Limelight

Editions, 1987.

Thomson, Elizabeth, and David Gutman, editors. The Dylan Com-

panion. New York, Delta, 1990.

Dynasty

Produced by Aaron Spelling for the ABC television network,

Dynasty was introduced to American television as a three-hour

movie, and lasted nine seasons in the form of a weekly one-hour

drama serial, from 1981-89. Perfect for the decade, which, despite the

conservatism and family values of the Reagan years, was character-

ized by increasing mass consumption, materialism, and the ‘‘me

generation,’’ Dynasty celebrated glamour, wealth, and capitalism.

Inspired by the monumentally popular CBS program Dallas, Dynas-

ty, along with Dallas and Falcon Crest (also on CBS) helped to define

a new genre—the prime-time soap opera—while reaching unprece-

dented heights of melodramatic, over-the-top, escapist absurdity.

Like their daytime counterparts such as General Hospital, the prime-

time soaps presented serialized narratives, with each episode ending

on a ‘‘cliffhanger,’’ or storyline left unresolved at the highest point of

tension, to be taken up in the next installment. The technique ensured

a captive audience, and Dynasty came to be one of the most popular

shows of the decade, dominating television screens not only in the

United States, but also in more than 70 other countries.

The show centered on the lives of the dynastic Carrington

family, headed by the patriarch Blake Carrington (John Forsythe), a

Denver oil tycoon. To the traditional story formula of the daytime

soaps was added a potent brew of adultery, murder, and deceit, as well

as complicated plotlines centered in corporate greed, rivalries, takeo-

vers, and mergers consonant with the patina of outrageous wealth that

DYNASTY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

784

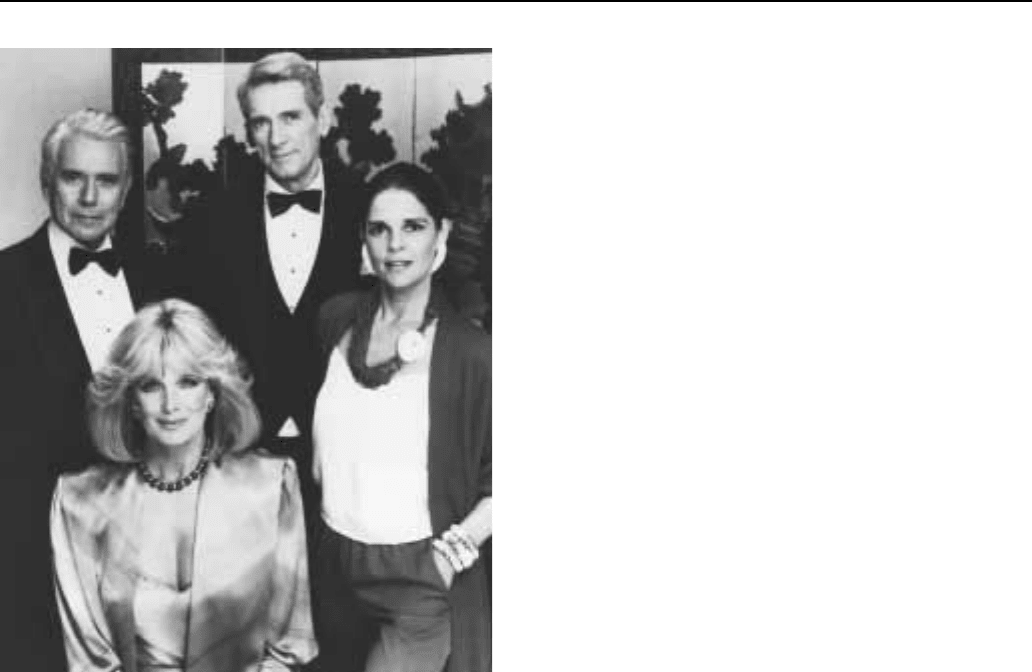

Members of the cast of Dynasty: (from left) John Forsythe, Linda Evans,

Rock Hudson, and Ali MacGraw.

was evident everywhere. Women were integral to Dynasty, no more

so than the character of Alexis, who became a byword for female

power and high-octane glamour. Ruthless, vengeful and cunning, she

was played by Joan Collins and the role made her a major star and a

household name in America and many other countries.

Much of Dynasty’s action involved the rivalry between Alexis,

as Blake’s ex-wife, and Krystle (Linda Evans), his current spouse, as

they battled for dominance, both figuratively and literally, in numer-

ous ‘‘cat fights.’’ One of the most interesting aspects of their

characters lay in presenting them as glamorous and sexy, albeit that

they were over 40—a rare departure for American television which,

like the movies, has tended to regard such attributes as belonging to

the younger generation (of whom Dynasty had its fair share of both

sexes). Audiences found the character of Alexis so deliciously

conniving that she became the center of the weekly spectacle.

Because of their highly stylized representations of domesticity

and personal problems, often characterized by excess, soap operas

have been much denigrated by the high-minded. However, Dynasty

was enjoyed by huge numbers of educated and intellectual viewers

and, as many scholars have pointed out, it is the soap opera that has

brought to American television those inflammatory issues so often

ignored by more seriously intentioned programs. Towards the end of

its run, it featured the first significant African American character in a

prime-time soap, Dominique Deveraux, played by Diahann Carroll.

Though the program did not directly confront issues of racism,

Deveraux’s presence raised the subject of interracial relationships,

while in Steven Carrington (played by Al Corley and later, Jack

Coleman), it introduced one of popular television’s first regular

homosexual characters.

—Frances Gateward

F

URTHER READING:

Dynasty: The Authorized Biography of the Carringtons. Garden City,

New York, Doubleday, 1984.

Geraghty, Christine. Women and Soap Opera: A Study of Prime Time

Soaps. Cambridge, England, Polity, 1991.

Gripsrud, Jostein. The Dynasty Years: Hollywood Television and

Critical Media Studies. London and New York, Routledge, 1995.