Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CROSBY, STILLS, AND NASHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

639

During his four decades as an entertainer, Crosby gathered a

fortune from radio, records, films, and TV and invested wisely in a

broad array of business ventures. Second in wealth only to Bob Hope

among showbiz people, Crosby’s fortune was at one time estimated at

anywhere between 200 and 400 million dollars, including holdings in

real estate, banking, oil and gas wells, broadcasting, and holdings in

the Coca-Cola Company. From the 1940s to the 1960s, Crosby owned

15 percent of the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team, but playing golf

was what he liked the most. He died playing at a course outside

Madrid—after completing a tour of England that had included a sold-

out engagement at the London Palladium.

After his death, Crosby’s Hollywood persona—established largely

by his role as the warm-hearted, easygoing priest in Going My Way—

underwent much reassessment. Donald Shepherd and W. H. Allen

composed an unflattering portrait of Crosby as an egotistic and

heartless manipulator in their biography, Bing Crosby—The Hollow

Man (1981). In Going My Own Way (1983), Garry Crosby, his eldest

son, told of his experiences as a physically and mentally abused child.

When Bing’s youngest son by Dixie Lee, Lindsay Crosby, committed

suicide in 1989 after finding himself unable to provide for his family,

it was revealed that Crosby had stipulated in his will that none of his

sons could access a trust fund he had left them before reaching age

sixty-five.

—Bianca Freire-Medeiros

F

URTHER READING:

Crosby, Bing. Call Me Lucky. New York, Da Capo Press, 1993.

MacFarlane, Malcolm. Bing Crosby: A Diary of a Lifetime. Leeds,

International Crosby Circle, 1997.

Mielke, Randall G. Road to Box Office: The Seven Film Comedies of

Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, and Dorothy Lamour, 1940-1962. Jeffer-

son, N.C., McFarland & Co., 1997.

Osterholm, J. Roger. Bing Crosby: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport,

Conn., Greenwood Press, 1994.

Shepherd, Donald, and Robert Slatzer. Road to Hollywood (The Bing

Crosby Film Book). England, 1986.

Shepherd, Donald, and W. H. Allen. Bing Crosby: The Hollow Man.

London, 1981.

Crosby, Stills, and Nash

David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash came together

in the late 1960s as idiosyncratic individual talents in flight from

famous groups. Their 1969 debut album arguably initiated the domi-

nance of singer-songwriters in popular music until the mid-1970s.

After appearing at the Woodstock festival, augmented by Neil Young,

they achieved a wider public role as the artistic apotheosis of the

hippie ideals of ‘‘music, peace, and love.’’ As the 1970s progressed,

however, CSN(&Y) became infamous for an inability to show

enough peace and love to one another to continue playing and

recording music together.

David Crosby had been an integral member of folk-rock pio-

neers The Byrds until he left the group amidst acrimony in 1967.

Crosby had first encountered Stephen Stills when the latter’s band,

Buffalo Springfield, supported The Byrds in concert in early 1966. In

May 1968, just after the demise of Buffalo Springfield, Crosby and

Stills met disillusioned Hollies frontman Graham Nash. As suggested

by the unassuming name, Crosby, Stills, and Nash was conceived as a

loose collective in order to foster creative freedom and forestall the

internal strife which each individual had experienced in his previous

band. Yet, with the release of Crosby, Stills and Nash, CSN was

hailed as a ‘‘supergroup,’’ and not just because of their prestigious

genealogy. Lyrics which concurred with the ideals of the ‘‘counter-

culture’’ were immersed in acoustic guitars and immaculate vocal

harmonies. Crosby and Stills’ ‘‘Wooden Ships’’ envisioned a new

Eden in the aftermath of nuclear apocalypse, while Nash’s ‘‘Marrakesh

Express’’ less grandly located utopia on the Moroccan hippie trail.

Stills’ Buffalo Springfield colleague and rival Neil Young was

recruited in June 1969 in order to bolster their imminent live shows.

Ominously, there were squabbles over whether Young should get

equal billing. With only one recently released record to their name,

and in only their second ever concert performance, CSN&Y wowed

the Woodstock festival in July 1969. There was a certain amount of

manipulation involved in the rapid mythologization of CSN&Y as the

epitome of the ‘‘Woodstock nation.’’ Their manager, David Geffen,

who also represented many of the other acts which appeared, threat-

ened to withdraw his cooperation from the film of the festival unless

CSN&Y’s cover of Joni Mitchell’s Woodstock was used over the

opening credits. Their record label, Atlantic, disproportionately fea-

tured CSN&Y on two very successful soundtrack album sets. In

contrast, CSN&Y’s appearance at The Rolling Stones’ disastrous free

festival at Altamont in December 1969 was, as Johnny Rogan has

observed, ‘‘effectively written out of rock history’’ by journalists

sympathetic to the CSN&Y-Woodstock cause.

There were unprecedented pre-release orders worth over $2

million for Deja Vu, released in March 1970. Though it was some-

what more abrasive than the debut album, due to the arrival of Young

and his electric guitar, Deja Vu was suffused with hippie vibes. These

were amusingly conveyed on Crosby’s ‘‘Almost Cut My Hair,’’ but

Nash’s ‘‘Teach Your Children’’ sounded self-righteous. In May

1970, CSN&Y rush-released the single ‘‘Ohio,’’ Young’s stinging

indictment of President Nixon’s culpability for the killing of four

student protesters by the National Guard at Kent State University.

After completing a highly successful tour in 1970 (documented on the

double-album Four-Way Street), CSN&Y were lauded by the media

as the latest American answer to the Beatles, a dubious honor first

bestowed on The Byrds in 1965, but which CSN&Y seemed capable

of justifying.

Instead, the foursome diverged into various solo ventures. While

this was informed by their insistence that, in Crosby’s words, ‘‘We’re

not a group, just one aggregate of friends,’’ individual rivalries and

the tantalizing example of Young’s flourishing solo career were also

determining factors. The flurry of excellent solo albums in the early

1970s, invariably featuring the ‘‘friends’’ as guests, only increased

interest in the enigma of the ‘‘aggregate.’’ When CSN&Y finally

regrouped in 1974, popular demand was met by a mammoth world-

wide tour of sport stadia which redefined the presentation, scale, and

economics of the rock’n’roll spectacle. But CSN&Y failed to com-

plete an album after this tour, and they never again attained such

artistic or cultural importance. After further attempts at a recorded

reunion failed, Crosby, Stills, and Nash eventually reconvened with-

out Young for CSN (1977). The album was another huge seller and

spawned CSN’s first top 10 single, Nash’s ‘‘Just a Song Before I

CROSBY, STILLS, AND NASH ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

640

(From left) David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and Neil Young, 1988.

Go.’’ Nevertheless, each member was past his peak in songwriting

terms, and their musical style and political views were being vocifer-

ously challenged by punk rock and its maxim, ‘‘Never trust a hippie.’’

Crosby was becoming ever more mired in cocaine and heroin

addiction. A farcical series of drug-related arrests culminated in his

incarceration in 1986. In that year’s ‘‘Hippie Dream,’’ Neil Young

transformed Crosby’s personal fate into a fable of the descent of

countercultural idealism into rock ’n’ roll hedonism (‘‘the wooden

ships / were just a hippie dream / capsized in excess’’). Crosby’s

physical recovery resulted in a much-publicized first CSN&Y album

in 18 years, American Dream (1988). The artistic irrelevance of

Crosby, Stills, and Nash, however, was highlighted not only by

comparisons between the new CSN&Y record and Deja Vu, but also

by Freedom (1989), the opening salvo of Neil Young’s renaissance as

a solo artist. In the early 1990s, while Young was being lauded as the

‘‘Godfather of Grunge,’’ Crosby, Stills, and Nash operated, as Johnny

Rogan observed, ‘‘largely on the level of nostalgia. This was typified

by their appearance at ‘‘Woodstock II’’ in August 1994. Young

refused to appear with CSN, and instead designed a range of hats

depicting a vulture perched on a guitar, a parody of the famous

Woodstock logo featuring a dove of peace. It was Young’s pithy

comment on the commodification of a (counter) cultural memory

with which his erstwhile colleagues were, even 25 years later,

inextricably associated.

—Martyn Bone

F

URTHER READING:

Crosby, David. Long Time Gone. London, Heinemann, 1989.

Rogan, Johnny. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young: The Visual Docu-

mentary. London, Omnibus Press, 1996.

———. Neil Young: The Definitive Story of His Musical Career.

London, Proteus, 1982.

Cross-Dressing

See Drag

CRUMBENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

641

Crossword Puzzles

Once a peripheral form of entertainment, crossword puzzles

have become a popular national institution. They appear in al-

most every newspaper, have become the focus of people’s daily

and weekend rituals, are published in their own books and maga-

zines, appear in foreign languages—including Chinese—and have

inspired other gridded word games like acrostic, cryptic, and

diagramless puzzles.

Arthur Wynne constructed the first crossword, which appeared

in 1913 in the New York World. His word puzzle consisted of an

empty grid dotted with black squares. Solvers entered letters of

intersecting words into this diagram; when correctly filled in, the

answers to the ‘‘across’’ and ‘‘down’’ numbered definitions would

complete, and hence solve, the puzzle. The layout and concept of the

crossword has not changed since its inception.

Although crossword puzzles appeared in newspapers after

Wynne’s debut, the New York Times legitimized and popularized the

pastime. The Times’s first Sunday puzzle appeared in the New York

Times Magazine in 1942, and daily puzzles began in 1950.

—Wendy Woloson

F

URTHER READING:

Shepard, Richard F. ‘‘Bambi Is a Stag and Tubas Don’t Go Pah-Pah.’’

New York Times Magazine. February 18, 1992, 31-9.

Cruise, Tom (1962—)

Tom Cruise is perhaps the most charismatic actor of the 1980s

and 1990s. Although initially dismissed as little more than a pretty

face with a million dollar smile when he made his screen debut as a

member of Hollywood’s ‘‘Brat Pack’’ generation of youthful leading

men in the early 1980s, he has demonstrated considerable staying

power and fan appeal. At one point between 1987 and 1989, four of

his films combined to post more than one billion dollars in box office

receipts. Yet, at the same time, he has proven to be a very serious actor

earning Academy Award nominations for ‘‘Best Actor’’ in 1989 in

Born on the Fourth of July, in which he portrayed disabled Vietnam

Vet Ron Kovic, and again in 1996 for a high energy performance in

Jerry Maguire. The latter film, in fact, served as an extremely

insightful commentary on many of the cocky, swaggering characters

he had portrayed in such exuberant films as Top Gun (1986), The

Color of Money (1986), Cocktail (1988), and Days of Thunder (1990).

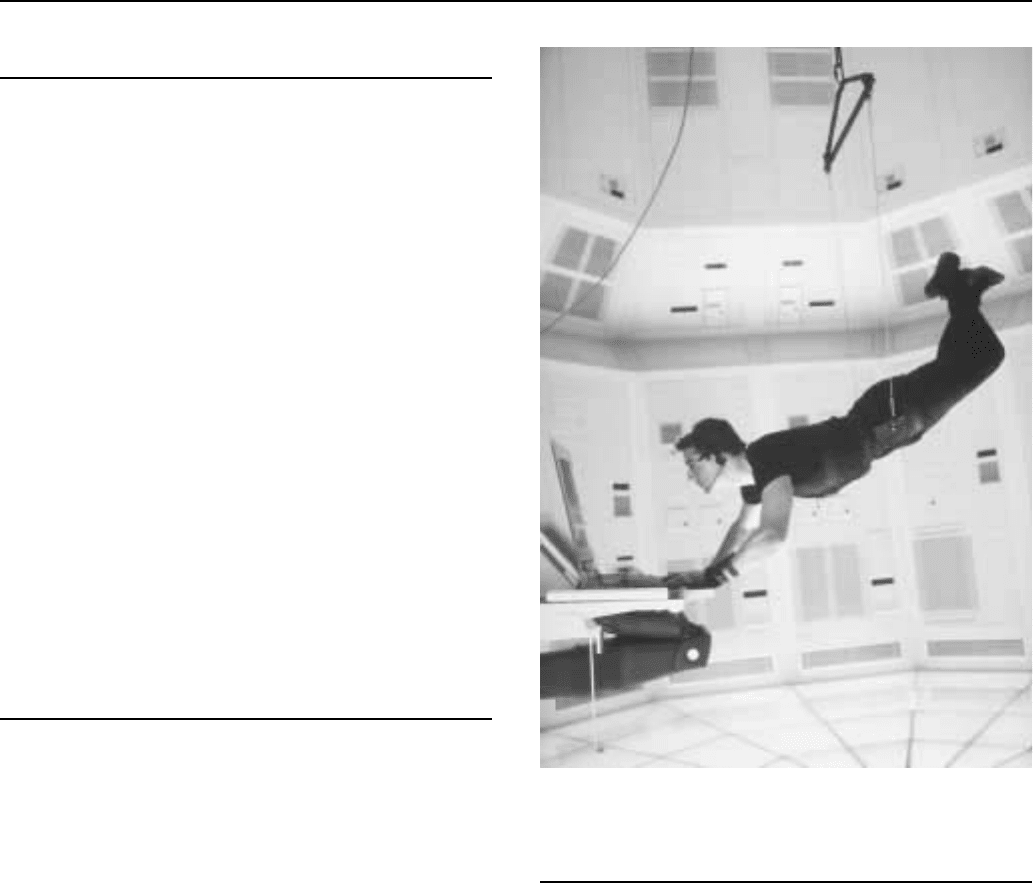

Cruise made the jump to producer in 1996 with the blockbuster

Mission Impossible, a big screen remake of the popular 1960s

television series. In 1999, he took on his most challenging leading role

in Stanley Kubrick’s sexual thriller Eyes Wide Shut, teaming with his

wife, Nicole Kidman.

—Sandra Garcia-Myers

F

URTHER READING:

Broeske, Pat H. ‘‘Cruising in the Media Stratosphere.’’ Los Angeles

Times Calendar. May 25, 1986, 19-20.

Corliss, Richard. ‘‘Tom Terrific.’’ Time. December 25, 1989, 74-9.

Greene, Ray. ‘‘Man with a Mission.’’ Boxoffice. April, 1996, 12-16.

Tom Cruise in a scene from the film Mission: Impossible.

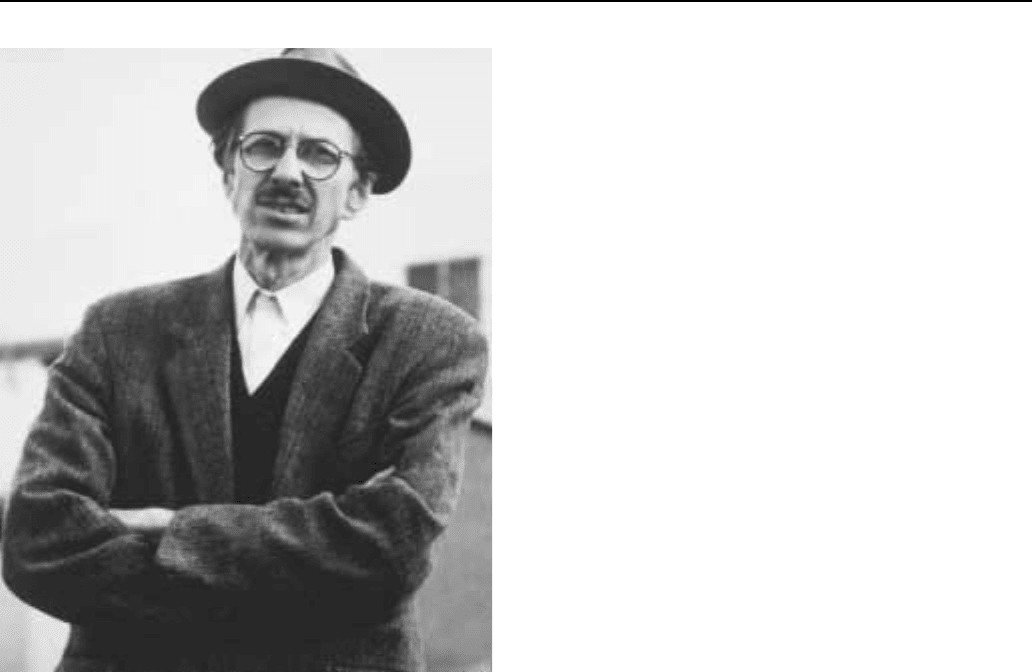

Crumb, Robert (1943—)

Robert Crumb is the most famous and well respected of all

underground comic artists, and the first underground artist to be

accepted into the mainstream of popular American culture. His

comics are notable for explicit, detailed, and unflattering self-confes-

sions, in which strange sexual fantasies abound. When not writing

about himself, he has targeted the American consumer-culture estab-

lishment, but also anti-establishment hippies and dropouts as subjects

for his satire. Crumb’s art veers from gritty, grubby realism to

extremes of Expressionism and psychedelia. As both an artist and a

writer, Crumb is a true original. Relentlessly unrestrained and impul-

sive, his work reflects few influences other than the funny animal

comics of Carl Barks and Walt Kelley, and the twisted, deformed

monster-people of Mad artist Basil Wolverton.

The Philadelphia-born Crumb lived his childhood in many

different places, including Iowa and California. Seeking refuge from

an alienated childhood and adolescence, he began drawing comics

with his brothers Charles and Max. As a young adult he lived in

Cleveland, Chicago, and New York before moving to San Francisco

in 1967, the year he began his rise to prominence. He had worked for a

greeting card company until he was able to produce comic books full

time, and his first strips appeared in underground newspapers such as

CRUMB ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

642

Robert Crumb

New York’s East Village Other before the first issues of his Zap

comic book were published in 1967. Zap introduced many of Crumb’s

most popular characters, as well as the unforgettable ‘‘Keep On

Truckin’’’ logo, and made a tremendous impact on the underground

comics scene. In 1970, particularly dazzling examples of his bizarre

and imaginative art appeared—with little in the way of story—in the

excellent XYZ Comics (1970).

Among Crumb’s most notable characters are Mr. Natural, a sort

of sham guru who lives like a hedonist and prefers to tease, and

occasionally exploit, his devotees rather than enlighten them, and his

occasional disciple, Flakey Foont, emblematic of the suburban neb-

bish fraught with doubts and hang-ups. Others include Angelfood

McSpade, a simple African girl exploited by greedy and lecherous

white Americans, diminutive sex-fiend Mister Snoid, and Whiteman

(a big-city businessman, proudly patriotic and moralistic yet inwardly

repressed and obsessed with sex). But Crumb’s most famous charac-

ter is Fritz the Cat, who first appeared in R. Crumb’s Comics and

Stories (1969). Fritz, a disillusioned college student looking for

freedom, knowledge, and counterculture kicks, became popular enough

to star in the 1972 animated movie Fritz The Cat, directed by Ralph

Bakshi, which became the first cartoon ever to require an X-rating.

While the movie proved a huge success with the youth audience,

Crumb hated the film and retaliated in his next comic book by killing

Fritz with an ice pick through the forehead.

By the late 1990s, Crumb’s comic-book work had been seen in a

host of publications over the course of three decades. In the early days

he was featured in, among other publications, Yellow Dog, Home

Grown Funnies, Mr. Natural, Uneeda Comix, and Big Ass. In the

1980s, he was published in Weirdo and Hup. In addition to his comic-

book work, he became well known for his bright, intense cover for the

Cheap Thrills album issued by Janis Joplin’s Big Brother and the

Holding Company in 1968. Though much of Robert Crumb’s best-

loved work was produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he

reached a peak of widespread fame in the mid-1990s with the

successful release of filmmaker Terry Zwigoff’s mesmerizing docu-

mentary, Crumb (1995), which interspersed shots of Crumb’s works

between frank interviews with the artist and his family, and comments

from media and culture critics. Crumb won the Grand Jury prize at the

Sundance Film Festival and was widely praised by critics. The film’s

impact is twofold: viewers are stunned by Crumb’s genius, while

being both moved and disturbed by the images of an unfortunate and

dysfunctional family. The film is honest in acknowledging controver-

sial aspects of the artist’s work, with critics on-camera pointing out

the racist caricatures, perverse lust, and, above all, the overt misogyny

that runs through much of Crumb’s oeuvre. Some of those images

have depicted scantily clad buxom women with bird heads, animal

heads, or no heads at all.

Despite the controversy, however, the 1980s and 1990s brought

a multitude of high quality Crumb compilations and reprints, includ-

ing coffee-table books, sketchbooks, and complete comics and stories

from the 1960s to the present. Meanwhile, his continuing output has

included the illustration of short stories by Kafka and a book on early

blues music. Profiles of Crumb have appeared in Newsweek and

People magazines, and on BBC-TV, while his art has been featured at

New York’s Whitney Museum and Museum of Modern Art, as well

as in numerous gallery shows in the United States, Europe, and Japan.

His comic characters have appeared on mugs, T-shirts, patches,

stickers, and home paraphernalia.

A fan of 1920s blues and string band music, Crumb started the

Cheap Suit Serenaders band in the 1970s, with himself playing banjo,

and recorded three albums. Remarkable in his personality as well as

his work, the shy Crumb prefers to dress, not like a bearded longhair

in the style of most male underground artists, but like a man-on-the-

street from the 1950s, complete with suit, necktie, and short-brimmed

hat. In 1993, he left California to settle in southern France with his

wife and daughter.

—Dave Goldweber

F

URTHER READING:

Beauchamp, Monte. The Life and Times of R. Crumb: Comments from

Contemporaries. New York, St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998.

Crumb, Robert. Carload O’ Comics. New York, Belier, 1976.

———, compiled by Carl Richter. Crumb-ology: The Works of

R. Crumb, 1981-1994. Sudbury, Massachusetts, Water Row

Press, 1995.

———. The Complete Crumb. Westlake, Fantagraphics, 1987-98.

Estren, Mark James. A History of Underground Comics. Berkeley,

Ronin, 1974; reissued, 1993.

Fiene, Donald M. R. Crumb Checklist of Work and Criticism: With a

Biographical Supplement and a Full Set of Indexes. Cambridge,

Massachusetts, Boatner Norton Press, 1981.

CULT FILMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

643

Crystal, Billy (1947—)

Billy Crystal went from stand-up comedy to playing Jodie

Dallas, American TV’s first major gay character, on the sitcom Soap

(1977-81). As a cast member on Saturday Night Live (1984-85),

Crystal was known for the catch-phrases ‘‘you look mahvelous’’ and

‘‘I hate it when that happens.’’ After he moved from the small screen

to films, Crystal’s endearing sensitivity and gentle wit brought him

success in movies such as Throw Momma from the Train (1987),

When Harry Met Sally (1989), and City Slickers (1991). He made his

directorial debut with Mr. Saturday Night (1992), the life story of

Buddy Young, Jr., a fictional Catskills comedian Crystal created on

Saturday Night Live.

—Christian L. Pyle

F

URTHER READING:

Crystal, Billy, with Dick Schaap. Absolutely Mahvelous. New York,

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1986.

Cukor, George (1899-1983)

An American film director whose career spanned over fifty

years, Cukor was particularly adept at female-centered melodrama

(Little Women, 1933; The Women, 1939), romantic comedy (The

Philadelphia Story, 1940; Adam’s Rib, 1949), and musicals (A Star Is

Born, 1954; My Fair Lady, 1964, for which he received a Best

Director Oscar). Often derided as a workman-like technician, revela-

tions about Cukor’s homosexuality led to reappraisals of his work by,

in particular, queer academics, who focused on his predilection for

more ‘feminine’ genres and gender-bending narratives, as seen in

Sylvia Scarlett (1935), for example. Cukor has thus, like fellow

director Dorothy Arzner, come to be perceived as an auteur, whose

sexual identity influenced the final form taken by the Hollywood

material he handled.

—Glyn Davis

F

URTHER READING:

McGilligan, Patrick. George Cukor: A Double Life. London, Faber

and Faber, 1991.

Cullen, Countee (1903-1946)

Among the most conservative of the Harlem Renaissance poets,

Harvard educated Countee Cullen exploded onto the New York

literary scene with the publication of Color (1925) and solidified his

reputation with Copper Sun (1927) and The Black Christ and Other

Poems (1929). His verse defied the expectations of white audiences.

Where earlier black poets like Paul Laurence Dunbar had written in

dialect, Cullen’s tributes to black life echoed the classical forms of

Keats and Shelley. The young poet was the leading light of the

African-American literary community during the 1920s. Although

his reputation waned after 1930 as he was increasingly attacked for

ignoring the rhythms and idioms of Black culture, Cullen’s ability to

present black themes in traditional European forms made him one of

the seminal figures in modern African-American poetry.

—Jacob M. Appel

F

URTHER READING:

Baker, Houston A. Afro-American Poetics: Revisions of Harlem and

the Black Aesthetic. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1988.

Ferguson, Blanche E. Countee Cullen and the Negro Renaissance.

New York, Dodd Mead, 1966.

Harris, Trudier, editor. Afro-American Writers from the Harlem

Renaissance to 1940. Detroit, Gale Research Co., 1987.

Turner, Darwin T. In a Minor Chord: Three Afro-American Writers

and Their Search for Identity. Carbondale, Southern Illinois

University Press, 1971.

Cult Films

Cult films are motion pictures that are favored by individual

groups of self-appointed connoisseurs who establish special mean-

ings for the films of a particular director or star or those which deal

with a particular theme. In practical terms, however, cult status can be

conferred on almost any film. In fact, such an occurrence is particular-

ly sought after by filmmakers to maintain interest in the film once its

initial theatrical run has been completed. Thus cult films might be

more accurately defined as those special films which, for one reason

or another, ‘‘connect’’ with a hard-core group of fans who never tire

of viewing them or discussing them.

Cult films, by their very nature, deal with extremes, eschewing,

for the most part, middle of the road storylines and character stereo-

types commonly seen in Hollywood studio products. These normally

small movies present unusual if not totally outrageous protagonists

involved in bizarre storylines that resolve themselves in totally

unpredictable ways. According to Daniel Lopez’s Films by Genre,

cult films may be divided into three basic categories: popular cult,

clique movies, and subculture films.

A prime example of the first type is George Lucas’s 1977 Star

Wars, which began as an evocation of the Saturday matinee serials of

the 1940s and 1950s. Using a basic cowboys vs. Indians theme

borrowed from the westerns of his childhood, Lucas updated the

frontier theme by adding technology and relocating the drama to outer

space. His effort, while failing to do much for the Western, created a

resurgence of interest in the science fiction and ‘‘cliffhanger’’ serial

genres. In the years that followed, Hollywood was inundated with sci-

fi thrillers, of which the most popular were the Star Trek sagas. At the

same time, another Lucas creation, the Indiana Jones films, showed

that there was still some interest in action adventure serials, a fact that

was further illustrated by Warner Bros. resurrection of the Batman

character, who had first come to the screen in the multi-episode

adventure short subjects of the 1940s. Star Wars elevation to cult

status was re-affirmed when it was re-released in theaters in 1997 and

broke all existing box-office records as its fans rushed to view it over

and over.

Yet widespread popularity and big box office receipts are

usually the antithesis of what most cult films are about, a fact

CULT FILMS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

644

illustrated by the so called ‘‘clique’’ films that appeal to a select few.

These are films that tend to be favored by special interest groups such

as film societies, cinefiles, and certain academics. Generally speaking

the films that appeal to cliques are either foreign, experimental, or

representative of a neglected genre. In the latter case, in particular,

proponents of a specific film usually believe that it has either been

overlooked or misinterpreted by filmgoers at large. They rediscover

the works of ‘‘B’’ movie directors such as Douglas Sirk or Sam Fuller

and, through retrospective screenings and articles in film journals,

attempt to make the case for their status as auteurs whose body of

works yield a special message heard only by them. In many cases, the

cult status awarded these directors has led to a re-evaluation of their

contributions to film by historians and scholars and to the distribution

of new prints of their works.

This process also works with individual films made by estab-

lished directors that somehow made only a slight impact during their

initial theatrical runs. The major example is Frank Capra’s It’s a

Wonderful Life (1946). Originally dismissed as a sentimental bit of

fluff, the film was seen primarily at Christmas Eve midnight screen-

ings for its faithful band of adherents until the 1980s, when it was

rediscovered by television and designated a classic. Similar transfor-

mations have occurred for John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) and,

surprisingly, Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz, which was first

released in 1939 to a lackluster reception and did not make money

until its second and third re-releases in the late 1940s.

The third type of cult film and, perhaps, the first one that comes

to mind for the average person is the ‘‘subculture cult film.’’ These

are small films created in a cauldron of controversy, experimentation,

and contention in every aspect of their production ranging from story

themes to casting. They are often cheaply made and usually don’t last

long at the box-office. Yet, to their fans, these films contain special

messages sent by the filmmakers and by the stars. Through word-of-

mouth contacts and, increasingly, by a variety of new media including

video and the Internet, cultists recruit new fans for the film, thus

serving to keep it alive well beyond its maker’s original intentions.

What is particularly fascinating, however, is the fact that all over the

world, a certain segment of filmgoers will react to these exact films in

the same way without word-of-mouth or advance indoctrination as to

its special status. This is the true measure of a film’s cult potential.

The fanatical appeal of these subculture favorites has also altered

the traditional patterns of movie going and the unique role of the

audience. In traditional viewing, the audiences are essentially pas-

sive, reacting to onscreen cues about when to laugh or cry and whom

to root for. The subculture film audience, however, takes on an

auteurial role on a performance-by-performance basis. This is due to

the fact that the viewers have seen the film so many times that they

know all of the lines and the characters by heart. Thus, they attend the

screening in the attire of their favorite characters and, once that

character appears on the screen, begin to shout out new dialogue that

they have constructed in their minds. The new script, more often than

not, alludes to the actor’s physical characteristics or foreshadows

future dialogue or warnings about plot twists. In many cases, audience

members will yell out stage directions to the actor, telling him that he

should come back and turn out a light or close a door.

Perhaps the most notable example of this auteuristic phenome-

non is the undisputed queen of cult films, the British production The

Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), which treats the plight of two

newlyweds, Brad (Barry Bostwick) and his virgin bride Janet (Susan

Sarandon), who become trapped in a spooky house on a rainy night in

Ohio. They are met by a group of fun loving aliens from the planet

Transylvania who are being entertained by Dr. Frankenfurter (Tim

Curry), who struts around in sexy female underwear and fishnet

stockings belting out gender bending tunes such as ‘‘I’m a Sweet

Transvestite From Transsexual Transylvania.’’ He is in the process of

creating a Frankenstein type monster, Rocky Horror (Peter Hinwood), to

be employed strictly for sexual purposes. During the course of the

evening, however, he manages to seduce both of the newlyweds and

also causes a suddenly liberated Janet to pursue a fling with Rocky

Horror, as well.

The film proved to be a box-office disaster when it was released

in 1975 but it did develop an underground ‘‘word-of-mouth’’ reputa-

tion, causing its American producer, Lou Adler, to convince Twenti-

eth-Century Fox to search for alternative ways to publicize it in order

to prevent a total disaster. The film was re-released at the Waverly

Theater in Greenwich Village and soon after at theaters throughout

the country for midnight performances. Its first audiences consisted

primarily of those groups represented in the film—transvestites, gays,

science fiction fans, punk rockers, and college psychology majors

(who presumably attended to study the rest of the audience).

For its avid viewers, attendance at a midnight screening began to

take on the form of a ritual. In addition to wearing costumes, members

of the audience would talk to the screen, create new dialogue, dance in

the aisles, and shower their fellow viewers with rice during the

wedding scene and water during the rainy ones. Experienced fans, of

course, attended with umbrellas but virgins (those new to the film)

generally went home bathed in rice and water. In the years since its

first screenings, the film has become a staple at midnight screenings

around the country and has achieved its status as the most significant

cult film of all time.

Performers in subculture films have acquired cult followings as

well. Many hard-core fans, in fact, view their favorite performers as

only revealing their real personalities in their ‘‘special’’ film. In

attempting to interpret the actor’s performance in this context, the

fans will also bring into play all of the performer’s previous charac-

terizations in the belief that they have some bearing on this particular

role. To such fans, the actor’s whole career has built toward this

performance. Although this perception has had little effect on the

careers of major stars, at least during their lifetimes, it has enhanced

the careers of such ‘‘B’’ movie icons as Divine and horror film actor

Bruce Campbell, making them the darlings of the midnight theatrical

circuit and major draws at fan conventions. Even deceased perform-

ers have been claimed by cult film devotees. The screen biography of

Joan Crawford, Mommie Dearest (1981), elevated—or lowered—her

from stardom to cult status, and Bela Lugosi attracted posthumous

fame with fans who revisited his old horror films with an eye to the

campy elements of his performances.

While not everyone agrees on which films are destined to

achieve special status with subcultures, a great many of them fall into

the horror and science fiction genres. The horror films that appeal to

this audience share most of the characteristics of cult films in general.

They are only rarely major studio productions but they frequently

‘‘rip off’’ such larger budgeted mainstream productions as The

Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), or the various manifestations of

Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Cult horror films inhabit the margins of the

cinema in pursuit of off-beat themes, controversial subject matter, and

shocking scenes of mayhem. They are either so startlingly original as

to be too ‘‘far out’’ for most viewers or they are such blatant

derivations of existing films that they are passed over by general

audiences and critics alike.

CULT FILMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

645

Horror films take on a special status with cultists for a number of

reasons. First and foremost is the authorial role certain films allow the

audience to play. Most horror film directors do not intend to send out a

specific message with their work. They simply want to make some

money. For this reason, most plots involve a demonic disruption in the

normal order of things which must be righted by each film’s protago-

nist before the status quo can be restored. This fundamentally safe

view of the world allows the audience to write its own text with any

number of subjective meanings regardless of what happens in the

story as a whole. The conservative stance of the filmmakers leaves

plenty of room for re-readings of the text to allow issues incorporating

a questioning of authority, a rejection of government and the military-

industrial complex, sexism, and a host of environmental concerns that

inevitably arise when horror films deal with the impact of man upon

nature. Perhaps the first cult horror film to raise such issues was Tod

Browning’s Freaks (1932), which was banned for 30 years following

its initial release. The film basically dealt with the simple message

that beauty is more than skin deep. When the protagonist, a circus

trapeze star, attempts to toy with the affections of a side show midget,

she is set upon by the side show ‘‘freaks,’’ who transform her physical

beauty into a misshapen form to reflect the ugliness within her. While

Browning was clearly attempting an entertaining horror film which

stretched the boundaries of the genre, there is no evidence that he

intended the many metaphysical meanings regarding the relationship

of good and evil and body and soul that audiences have brought to the

film in the 60 years since its initial release.

Another film, 1956’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, has been

celebrated by scholars as a tract against the McCarthyism of the

1950s, though it is probably more rightly read as a more general

statement against conformity and repression of individual thought

that transcends its period. Similarly, George Romero’s legendary

Night of the Living Dead (1968) was not only the goriest movie of its

time but it also worked on our basic fears. Like its inspiration, Alfred

Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), it deals with a group of people

confined to a certain geographic area while nature runs amok because

man has transgressed against the natural law. The film is particularly

effective because it deals with gradations of insanity, beginning with

stark fear and escalating to show that man is totally powerless to deal

with the things that he fears most. Audiences sat riveted to their seats,

convinced that there was no way out except death. The film began as

the second feature on drive-in movie double bills and, through strong

word-of-mouth and gradual acceptance from critics, took on a second

life in college retrospectives and museum screenings (where it

was declared a masterpiece) before winding up on the midnight

movie circuit.

Another reason for the cult appeal of low budget horror films is

the fact that they often push the limits of what is traditionally thought

to be acceptable. For example, the legendary Blood Feast (1976)

became the first film to go beyond mere blood to the actual showing of

human entrails, a technique that was later picked up by Hollywood for

much larger special effects laden films. Another low budget film, Evil

Dead II (1987), directed by Sam Raimi, surpassed its bloody prede-

cessor presenting extreme violence at such a fast pace that the human

eye could barely register the images flashing by.

A final appeal of low budget horror films is the fact that a

number of major actors and directors—including Jack Nicholson,

Tom Hanks, Francis Ford Coppola, and Roger Corman—got their

start in them. Corman once referred to these pictures as a film school

where he learned everything he would ever need to become successful

in motion pictures. But it worked the other way as well. Many stars on

the downslope of their careers appeared in grade ‘‘B’’ horror films to

keep their fading careers alive, hoping that they might accidentally

appear in a breakthrough film. Former box-office stars—including

Boris Karloff (The Terror), Bela Lugosi (Plan Nine From Outer

Space), Yvonne DeCarlo (Satan’s Cheerleaders), and Richard Basehart

(Mansion of the Doomed)—who had been forgotten by Hollywood

received a new type of stardom in these grade ‘‘B’’ films, and often

spent the last years of their careers appearing at comic book and

horror film conventions for adoring fans.

Science fiction films are very similar to horror movies in that

they push the cinematic envelope by their very identification with

their genre. They are futuristic, technologically-driven films that

employ astonishing special effects to create a world that does not yet

exist but might in the future. Sci-fi movies can also be horror films as

well. It took technology to create the Frankenstein monster and it took

technology to encounter and destroy the creature in Alien (1979). But,

like horror films, they also question the impact of man and his

technology on the world that he lives in. They make political

statements through their futuristic storylines, saying, in effect, that 20

or more years in the future, this will be mankind’s fate if we do not

stop doing certain things.

Science fiction films that achieve cult status do so because, even

within this already fantastic genre, they are so innovative and experi-

mental that they take on a life of their own. With the exceptions of the

Star Wars, Star Trek, and Planet of the Apes series and a number of

individual efforts such as 2001 (1968), the films that attract the long

term adulation of fans are generally not large studio products. They

are normally small films such as the Japanese Godzilla pictures;

minor films from the 1950s with their dual themes of McCarthyism

and nuclear monsters; and low budget favorites from the 1970s

and 1980s.

Again, as in horror, the pictures seem to fall into three categories

of fan fascination. These include films such as Brain Eaters (1958),

Lifeforce (1985), and The Incredible Two-Headed Transplant (1971)

that feature major stars such as Leonard Nimoy, Patrick Stewart, and

Bruce Dern on the way up. Conversely, a number of major stars

ranging from Richard Burton and Henry Fonda appeared in some

otherwise forgettable science fiction films during the twilight of their

careers which have made their performances memorable to aficionados

of embarrassing moments on film. Still other stars, however, are able

to turn almost any film that they are in into a sci-fi cult film. The list is

headed by Zsa Zsa Gabor, Vincent Price, Bela Lugosi, and John Agar.

In the final analysis, cult films say more about the people who

love them than about themselves. To maintain a passion for a film that

would compel one to drive to the very worst parts of town dressed in

outlandish costumes to take part in a communal viewing experience

sets the viewer apart as a special person. He or she is one of a select

few that has the ability to interpret a powerful message from a work of

art that has somehow escaped the population at large. In pursuing the

films that they love, cultists are making a statement that they are not

afraid to set themselves apart and to take on the role of tastemakers for

the moviegoers of the future. In many cases, the films that they

celebrate influence filmmakers to employ new subjects, performers,

or technology in more mainstream films. In other instances, their

special films will never be discovered by the mainstream world. But

that is part of the appeal: to be different, to be ‘‘out there,’’ is to be like

the cult films themselves.

—Steve Hanson

CULTS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

646

FURTHER READING:

Everman, Welch. Cult Horror Films: From ‘‘Attack of the 50-Foot

Woman’’ to ‘‘Zombies of Mora Tau.’’ Secaucus, New Jersey,

Carol Publishing Group, 1993.

———. Cult Science Fiction Films. New York, Carol Publishing

Group, 1995.

Henttzi, Gary. ‘‘Little Cinema of Horrors.’’ Film Quarterly. Spring

1993, 22-27.

Lopez, Daniel. Films by Genre. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland

& Co., 1993.

Margules, Edward, and Stephen Rebello. Bad Movies We Love. New

York, Plume, 1993.

Peary, Danny. Cult Movies: The Classics, the Sleepers, the Weird,

and the Wonderful. New York, Gramercy Books, 1998.

———. Cult Movie Stars. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1991.

Cults

The 1978 Jonestown Massacre, where 913 of the Reverend Jim

Jones’ followers were forced to commit suicide, marked the high

point in America’s condemnation of cults. Spread across newspaper

front pages and national magazines from coast to coast, the slaughter

gave focus to an alarm that had grown throughout the decade. Were

cults spreading like wildfire? Were Rasputin-like religious leaders

luring the nation’s youth into oblivion like modern-day Pied Pipers?

The Jonestown coverage reinforced the common perception that, in

cults, America harbored some alien menace. The perception could not

be further from the truth. In a sense, America was founded by cults,

and throughout the nation’s history, cults and splinter groups from

established religions have found in America a fertile cultural terrain.

That modern-day Americans find cults alarming is yet another

example of America’s paradoxical culture.

Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines a cult as ‘‘a religion

regarded as unorthodox and spurious; also: its body of adherents.’’

Cults as they are understood in the popular imagination have some

additional characteristics, and can include: any religious organization

that spends an inordinate amount of time raising money; any religion

that relies on a virulent us-vs.-them dogmatism, thereby alienating its

members further from mainstream society; and any religion where the

temporal leader holds such sway as to be regarded as a deity, a deity

capable of treating cult members as financial, sexual, or missionary

chattel to be exploited to the limits of their endurance. In this

expanded definition, a Pentecostal such as Aimee Semple McPherson,

the Los Angeles preacher, and not technically a cult leader, fits

adequately into the definition, as does Jim Jones, Charles Manson, or

Sun Myung Moon.

Originally, America was a land of pilgrims, and the Plymouth

colonists were not the last to view the New World as a holy land. And

as in all times and all religions, religious charlatans were a constant.

By the close of the nineteenth century, Americans had founded some

peculiar interpretations of Christianity. The Mormons, Seventh Day

Adventists, Christian Scientists, and Jehovah’s Witnesses all had

their origins in the nineteenth century, and by dint of accretion, they

had developed from dubious, persecuted faiths into respectable

institutions. In the history of Mormonism one can discover much that

is pertinent to understanding modern-day cults; elements of this tale

are reminiscent of the histories of Scientology, The Unification

Church, and People’s Temple, among others. A charismatic leader,

claiming divine inspiration and not above resorting to trickery,

amasses a following, who are viewed with derision by the general

populace. The faith aggressively recruits new members and later

attempts to gloss over its dubious origins, building enormous and

impressive edifices and going out of its way to convey an image

of solidity.

From time to time, waves of religious fervor have swept across

America—the Shakers and Pentecostals early in the nineteenth centu-

ry, for instance, or the Spiritualist and Theosophy movements at

century’s end. In western New York state, where the Church of Latter

Day Saints originated, so many evangelical movements caught fire in

the 1820s that it was nick-named the ‘‘Burned-over District.’’ The

church’s founder, Joseph Smith, claimed to have received revelation

directly from an angel who left Smith with several golden tablets on

which were inscribed the story of Hebraic settlers to the New World.

Smith and his band of youthful comrades ‘‘was regarded as wilder,

crazier, more obscene, more of a threat’’ writes Tom Wolfe, ‘‘than the

entire lot of hippie communes put together.’’ Smith’s contemporaries

called him ‘‘a notorious liar,’’ and, ‘‘utterly destitute of conscience’’

and cited his 1826 arrest for fortune-telling as evidence of his

dishonesty. But by the time Smith fled New York in 1839, he was

accompanied by 10,000 loyal converts who followed him to Nauvoo,

Illinois, with an additional 5,000 converts from England swelling

their numbers. After Smith began a systematic power-grab, using the

Mormon voting block in gaining several elected positions, he was

lynched by the locals, and (shades of Jim Jones’ flight to Guyana) the

Mormons continued westward to Utah, where the only threat was the

Native Americans.

An earnest desire to bring people into the fold has often devolved

into hucksterism in the hands of some religious leaders. Throughout

the twentieth century, Elmer Gantry-esque religious leaders, from the

lowly revivalist preacher to the television ministries of a Jimmy

Swaggart or Oral Roberts, have shown as much concern with fleecing

their followers as with saving their souls. When the founder of the

Church of Christ, Scientist, Mary Baker Eddy, died in 1910, she left a

fortune of three million dollars. George Orwell once mused that the

best way to make a lot of money is to start one’s own religion, and L.

Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology, took Orwell’s maxim to heart.

A pulp fiction writer by trade, Hubbard originally published his

‘‘new science of Dianetics,’’ a treatise on the workings of the mind, in

the April, 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. Dianetics was a

technique for self-actualization and understanding, and Hubbard

couched his theories in scientific rhetoric and obscure phraseology to

appeal to a well-educated, affluent constituency. Published in book

form, Dianetics became an overnight success, and Hubbard quickly

set up a ‘‘research institute’’ and began attracting adherents. Dianetics,

as practiced by Hubbard, straddled the gap between the self-actualiza-

tion movements typical of later religious cults, and religion (though

Scientology’s mythos was not set down until shortly before Hubbard’s

death). In Dianetics, an auditor ran a potential follower through a list

of questions and their emotional response was measured with an e-

meter, a simple galvanic register held in both hands. This meter

revealed the negative experiences imprinted in one’s unconscious in

an almost pictorial form called an engram, and Dianetics promised to

sever the unconscious connection to negative experiences and allow

the follower to attain a state of ‘‘clear,’’ an exalted state similar to

enlightenment. Hubbard’s idea appeared scientific, and like psycho-

therapy, it was an inherently expensive, time-consuming process.

CULTSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

647

From the beginning, Hubbard ran into all manner of legal

troubles. He squabbled with the I.R.S. over the church’s tax-exempt

status, and the F.D.A. over the use of the e-meter. Scientology met

stiff government opposition in every country in which it operated. An

Australian Board of Inquiry, convened in 1965, called Scientology

‘‘evil, its techniques evil, its practice a serious threat to the communi-

ty, medically, morally, and socially.... Scientology is a delusional

belief system, based on fictions and fallacies and propagated by

falsehoods and deception’’; it was banned from Australia until 1983.

The British government banned foreign Scientologists in 1968, and

Hubbard was convicted on fraud charges, in absentia, by a Paris court

in 1978. The Church lost its tax-exempt status in France and Denmark

in the mid-1980s, and has had to seriously curtail its operations in

Germany. More than most cults, Scientology’s travails appeared to be

symptomatic of its founder’s mental instability. As an institution,

Scientology was marked by an extreme fractiousness and a pro-

nounced penchant for litigation. Ruling in a 1984 lawsuit brought by

the church, a Los Angeles judge stated, ‘‘The organization clearly is

schizophrenic and paranoid, and this bizarre combination seems to be

a reflection if its founder.’’

In many ways Scientology anticipated the tactics of the wave of

cult groups that would sweep America in the 1960s and 1970s. There

numbers are almost innumerable, therefore, a look at two of the most

infamous—the Unification Church and the Hare Krishnas—must

suffice to explain this religious revival, what Tom Wolfe termed ‘‘the

Third Wave.’’ Better known by the pejorative term, Moonies, in

1959, the Unification Church, a radical offshoot of Presbyterianism,

founded its first American church in Berkeley. Its founder, the

Reverend Sun Myung Moon, converted from his native Confucian-

ism as a child, receiving a messianic revelation while in his teens.

Moon was expelled from his church for this claim, as well as his

unorthodox interpretation of Christianity, but by the late-1950s he

had established a large congregation and the finances necessary to

begin missionary work abroad. Like many cults, the church’s teach-

ings were culturally conservative and spiritually radical. Initially, it

appealed to those confused by the rapid changes in social mores then

prevalent, offering a simple theology and rigid moral teachings.

The Unification Church was aggressive in its proselytizing.

Critics decried its recruitment methods as being callous, manipula-

tive, and deceitful; the charge of brainwashing was frequently leveled

against the church. Adherents preyed on college students, targeting

the most vulnerable among them—the lonely, the disenfranchised,

and the confused. The unsuspecting recruit was typically invited over

to a group house for dinner. Upon arrival, he or she was showered

with attention (called ‘‘love-bombing’’ in church parlance), and told

only in the most general terms the nature of the church. The potential

member was then invited to visit a church-owned ranch or farm for the

weekend, where they were continually supervised from early morn-

ing until late at night.

Once absorbed, the new member was destined to take his/her

place in the church’s vast fund-raising machine, selling trinkets,

candy, flowers, or other cheap goods, and ‘‘witnessing’’ on behalf of

the church. Often groups of adherents traveled cross country, sleeping

in their vehicles, renting a motel room once a week to maintain

personal hygiene, in short, living lives of privation while funneling

profits to the church. Moonie proselytizers were known for their

stridency and their evasions, typically failing to identify their church

affiliation should they be asked. On an institutional level, the church

resorted to this same type of subterfuge, setting up dozens of front

groups, and buying newspapers and magazines—usually with a right-

wing bias (Moon was an avowed anti-Communist, a result of his

spending time in a North Korean POW camp). The Unification

Church also developed an elaborate lobbying engine; it was among

the few groups that actually supported Richard Nixon, organizing

pro-Nixon demonstrations up until the last days of his administration.

Allusive, shadowy connections to Korean intelligence agencies were

also alleged. The church, with its curious theology coupled with a

rabid right-wing agenda, was and is a curious institution. Like

Hubbard, many Christian evangelists, and other cult leaders, Moon

taught his followers to be selfless while he himself enjoyed a life of

luxury. But the depth and scope of his political influence is profound,

and among cults, his has achieved an unprecedented level of

political power.

Like the Unification Church, the International Society for Krish-

na Consciousness (ISKCON), better known as the Hare Krishna

movement, has drawn widespread criticism. Unlike the Unification

Church, the Hare Krishnas evince little concern for political exigen-

cies, but their appearance—clean-shaven heads and pink sari—make

the Hare Krishnas a very visible target for anti-cult sentiments, and

for many years, the stridency of their beliefs exacerbated matters. A

devout Hindu devotee of Krishna, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

Prabhupada, was charged by his guru with bringing Hinduism to the

west. Arriving in America in 1965, Prabhupada’s teachings became

popular with members of the emerging hippie populace, who adopted

the movement’s distinctive uniform, forswearing sex and drugs for

non-chemical bliss. Hare Krishnas lived in communes, practicing a

life of extreme asceticism and forsaking ties with family and friends.

Complete immersion in the group was de rigueur. The movement

spread rapidly, becoming infamous for its incessant street proselytiz-

ing, in which lines of devotees would play percussion instruments

while chanting for hours. The sect’s frequenting of airports and train

stations, importuning travelers with flowers or Prabhupada’s transla-

tion of the classic Indian text, the Bhagavad-Gita, also drew public

scorn. Like the Moonies, the Hare Krishna’s fundraising efforts

helped turn public opinion against the cult.

In the 1970s, as more and more American joined such groups as

the Unification Church, the Hare Krishnas, or the ‘‘Jesus People’’ (an

eclectic group of hippies who turned to primitive charismatic Christi-

anity while retaining their dissolute fashions and lifestyle), parental

concern intensified. An unsubstantiated but widely disseminated

statistic held that a quarter of all cult recruits were Jewish, pro-

voking alarm among Jewish congregations. To combat the threat,

self-proclaimed cult experts offered to abduct and ‘‘deprogram’’

cult members for a fee, and in the best of American traditions,

deprogramming itself became a lucrative trade full of self-aggrandiz-

ing pseudo-psychologists. The deprogrammers did have some valid

points. Many cults used sleep deprivation, low-protein diets, and

constant supervision to mold members into firmly committed zealots.

By stressing an us-vs.-them view of society, cults worked on their

young charges’ feelings of alienation from society, creating virtual

slaves who would happily sign over their worldly possessions, or, as

was the case with a group called the Children of God, literally give

their bodies to Christ as prostitutes.

For those who had lost a child to a cult, the necessity of

deprogramming was readily apparent. But in time, the logic of the

many cult-watch dog groups grew a bit slim. If anything, the

proliferation of anti-cult groups spoke to the unsettling aftershocks of

the 1960s counterculture as much as any threat presented by new

religions. Were all religious groups outside the provenance of an

CUNNINGHAM ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

648

established church to be equally condemned? Were all religious

beliefs that weren’t intrinsically exoteric to be rejected out of hand?

By stressing conformity, many watch-dog groups diluted their

moral authority.

Ironically, while cult watchdog groups focused public outrage

on the large, readily identifiable cults—Scientology, ISKCON, the

Unification Church—it was usually the smaller, homegrown varieties

that proved the most unstable. Religions are concerned with self-

perpetuation. When a charismatic leader dies, stable religious groups

often grow more stable and moderate and perpetuate themselves (as

has the now respectable Church of Latter Day Saints). But smaller

cults, if they do not dissolve and scatter, have often exploded in self-

destruction. The People’s Temple, the Branch Davidians (actually a

sect of Presbyterianism), and the Manson Family were such groups.

In 1997, Heaven’s Gate, a cult with pronounced science fiction beliefs

based in California, committed mass suicide in accordance with the

passing of the Hale-Bopp comet.

The Jonestown massacre in the Guyanese jungle in 1978 marks

the period when cult awareness was at its height, although incidents

like the Heaven’s Gate mass suicide have kept cults in the headlines.

Such is the degree of public suspicion of cults that, when necessary,

government agencies could tap into this distrust and steer blame away

from their own wrongdoing, as was the case when the Bureau of

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms and the F.B.I. burned the Branch

Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, to the ground in 1993 after

followers of cult leader David Koresh refused to surrender themselves

to authorities. At the time of the massacre, media reportage was

uniform in its condemnation of Koresh, and vociferous in its approval

of the F.B.I.; it was only with the release of Waco: The Rules of

Engagement, a 1997 documentary on the FBI’s mishandling of the

situation, that a dissenting note was finally heard.

America is not unique in its war between the ‘‘positive,’’

socializing aspects of religion, and the esoteric, ecstatic spiritualism

running in counterpoint beside it. ‘‘As Max Weber and Joachim

Wach have illustrated in detail,’’ writes Tom Wolfe, ‘‘every major

modern religion, as well as countless long-gone minor ones, has

originated not with a theology or set of values or a social goal or even

a vague hope of a life hereafter. They have all originated, instead, with

a small circle of people who have shared some overwhelming ecstasy

or seizure, a ‘vision,’ a ‘trance,’ an hallucination; in short, an actual

neurological event.’’ This often-overlooked fact explains the suspi-

cion with which mainstream religions view the plethora of cults that

rolled over America since its founding, as well as the aversion cult

members show to society at large once they have bonded with their

fellows in spiritual ecstasy. It is precisely these feelings of unique-

ness, of privileged insight, that fraudulent cult leaders work on in their

efforts to mold cult members into spiritual slaves. The problem is this:

not all cults are the creation of charlatans, but the opprobrium of

society towards cults is by now so ingrained that on the matter of

cults, there is no longer any question of reconciling the historical

precedent with the contemporary manifestation.

But one salient fact can still be gleaned from the history of cults

in modern America: to quote H.L. Mencken, ‘‘nobody ever went

broke underestimating the intelligence of the American people.’’

Americans are and will continue to be endlessly susceptible to simple,

all-encompassing explanations, and what most cults share is a rigid

dogmatism that brooks no argument, a hermetically sealed belief-

system, eternally vulnerable to exposure from the world-at-large. The

rage of a Jim Jones or Charles Manson springs from not only their

personal manias, but in their impotence in controlling the world to suit

their teachings. When cults turn ugly and self-destructive, it is often in

reaction to this paradox. Like a light wind blowing on a house of

cards, cults are fragile structures—it does not take much to set them

tumbling down. Still, given mankind’s pressing spiritual needs, and

despite society’s abhorrence, it seems likely that cult groups will

continue to emerge in disturbing and occasionally frightening ways.

—Michael Baers

F

URTHER READING:

Barrett, David V. Sects, ‘‘Cults,’’ and Alternative Religions: A World

Survey and Sourcebook. London, Blandford, 1996.

Christie-Murray, David. A History of Heresy. London, Oxford Uni-

versity Press, 1976.

Collins, John J. The Cult Experience: An Overview of Cults, their

Traditions, and Why People Join Them. Springfield, Illinois, C. C.

Thomas, 1991.

Jenkins, Philip. Stoning the Prophets: Cults and Cult Scares in

Modern America. Oxford and New York, Oxford University

Press, 2000.

Lane, Brian. Killer Cults: Murderous Messiahs and their Fanatical

Followers. London, Headline, 1996.

Robbins, Thomas. Cults, Converts & Charisma. London, Sage Publi-

cations, 1988.

Stoner, Carroll, and Jo Anne Parke. All God’s Children. Radnor,

Pennsylvania, Chilton, 1977.

Wolfe, Tom. Mauve Gloves and Madmen, Clutter and Vine: The Me

Decade and the Third Great Awakening. Toronto, Collins Pub-

lishers, 1976.

Yanoff, Morris. Where Is Joey?: Lost Among the Hare Krishnas.

Athens, Ohio University Press, 1981.

Zellner, William W., and Marc Petrowsky, editors. Sects, Cults, and

Spiritual Communities: A Sociological Analysis. Westport, Con-

necticut, Praeger, 1998.

Cunningham, Merce (1919—)

The dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham influenced

20th century art with his postmodern dance and his collaborations

with other important figures of the American art scene such as John

Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. With his own dance

company, founded in 1953, Cunningham challenged traditional ideas

of dance and the expectations of audiences. Cunningham declared all

elements of a performance—music, dancing bodies, set, and cos-

tumes—to be of equal importance, and dispensed with conventional

plots. His pioneering video work further questioned the use of the

stage. Cunningham and his collaborators incorporated chance into the

elaborate systems of their performances, creating abstract and

haunting dances.

—Petra Kuppers

F

URTHER READING:

Harris, Melissa, editor. Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years. New York,

Aperture, 1997.