Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

COUNTRY MUSICENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

619

followed. Jimmie Rodgers sold between 6 and 20 million records (by

various estimates) before his death in 1933. The blues were hit hard as

a commercial medium by the depression, but country music did well

in the 1930s. Radio, a more viable medium for white music, kept

country music in the public ear with various local ‘‘barn dance’’

programs, including the phenomenally successful Grand Ole Opry,

which started in 1925.

One singer who emerged from regional radio in the 1930s to

reshape country music was Gene Autry. Autry, who had scored a hit

record in 1931 with ‘‘That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine,’’ a senti-

mental song in the Jimmie Rodgers mode, was summoned to Holly-

wood in 1934, as the answer to a Republic Studios mogul’s brain-

storm: The hottest new trend in movies was the musical talkie, like

The Jazz Singer, and perennial cinema moneymaker was the Western.

With Autry’s enormous success as a singing cowboy in films,

‘‘country’’ became ‘‘country and western.’’ Gene Autry became the

first country star to gain an audience beyond the rural South and West,

even drawing a million fans at a 1939 performance in Dublin, Ireland.

Rather than authentic western songs, Autry sang music composed by

Hollywood songwriters, calculated to appeal to audiences that lis-

tened to Cole Porter and Irving Berlin as well as Jimmie Rodgers and

the Carter Family. The new songs succeeded so well that Berlin

would ultimately write his own cowboy song, ‘‘Don’t Fence Me In.’’

This was country’s first flirtation with the mainstream of Ameri-

can music. Roy Rogers followed Autry’s path to success, and soon

they were imitated by a multitude of lesser singing cowboys. There

was no country music industry as such in the 1930s, but this outsider/

mainstream dichotomy would remain an issue throughout country’s

history. The other significant innovation in the country music of the

1930s also came from the West, and was another unlikely fusion. In

Texas, Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys blended jazz and country to

create a new and infectious dance music.

In the 1940s, country music had its own hit parade, as Billboard

magazine created its first country chart in 1944. First called the ‘‘folk

music’’ chart, it became the ‘‘country and western’’ chart in 1949,

and its first number one hit was Al Dexter’s ‘‘Pistol Packin’ Mama.’’

‘‘Folk music’’ being loosely defined, the early charts included artists

like Louis Jordan, Nat ‘‘King’’ Cole, and Bing Crosby. But country

was starting to amass its first generation of major stars—singers like

Ernest Tubb, Hank Snow, Red Foley—and the new sound of blue-

grass music, which had been popularized by Bill Monroe in the 1930s,

but gained its full maturity when Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs joined

Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys in the mid-1940s.

In an important sense, country’s key figure in the 1940s was Roy

Acuff. Acuff joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1938, and not long after

became the Opry’s host, presiding over its period of greatest populari-

ty. In 1942, Acuff and songwriter Fred Rose started a music publish-

ing company, Acuff-Rose, which signed country songwriters, and

created a new standard of professionalism in the field. The Opry and

Acuff-Rose were, together, the most significant factors in solidifying

the place of Nashville as the country music capital of America. World

War II brought a lot of young GIs from the north down to army bases

in the South, where they heard Acuff’s music and broadened coun-

try’s listening base even further.

In 1946, Acuff-Rose signed Hank Williams to a writing contract,

and in 1947 Williams had his first chart hit, ‘‘Move It on Over.’’ He

joined the Louisiana Hayride, the second most influential of the

country radio shows (Elvis Presley also began his career on the

Hayride), in 1948, and came to the Opry in 1949. With Hank

Williams, country had a star who outshone all who came before, and

who set the standard for all who came after. His songs (like Rodgers’

were deeply blues-influenced) were as simple as conversation, but

unforgettable. ‘‘Your Cheatin’ Heart,’’ ‘‘Hey, Good Lookin’,’’ ‘‘Cold,

Cold Heart,’’ and ‘‘I Can’t Help It if I’m Still in Love with You’’ are

just a few Williams’ tunes that are still classics. Williams, like his

contemporaries, jazzman Charlie Parker and poet Dylan Thomas,

lived out the myth of the self-destructive, tormented artist and died

too young in the back seat of his limosine on the way to a concert on

New Year’s Day in 1953; he was 29 years old.

As the 1950s began, mainstream American popular music was

becoming moribund. The creative energy of the ‘‘Tin Pan Alley’’

songwriters, the New York-centered, Broadway-oriented popular

song crafters, seemed to be flagging. Singers like Tony Martin, Perry

Como, Teresa Brewer, and the Ames brothers were only marginally

connected to the pulse of the new generation. Country music and

rhythm and blues both began to make inroads into that mainstream,

but at first it was only the songs, not the singers, that gained

popularity. Red Foley had a number one pop hit with ‘‘Chattanoogie

Shoe Shine Boy’’ in 1950, but for the most part it was pop singers like

Tony Bennett and Jo Stafford, the McGuire Sisters and Pat Boone

who took their versions of country and R&B songs up the pop charts.

At the same time, country and R&B music were making an

alliance of their own. Nashville was now entrenched as the capital of

the country music establishment, but the new music came from Sun

Records in Memphis, where Sam Phillips recorded Elvis Presley, Carl

Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash. It was called rock ’n’ roll,

and the country music establishment did not like it. Elvis began his

career as ‘‘The Hillbilly Cat,’’ and was featured on Louisiana

Hayride, but he never sang on the Opry, and rock ’n’ roll, denounced

by Roy Acuff, never made an impact there. Racism certainly played a

part in the country establishment’s rejection of rock ’n’ roll. The new

music was widely denounced throughout the South by organizations

like the White Citizen’s Council. At the same time, however, country

music was beginning to outgrow its raffish, working-class roots.

Eddie Arnold, the biggest star of the late 1940s and early 1950s, called

himself ‘‘The Tennessee Plowboy,’’ a nickname he had acquired

early in his career, but he was no plowboy. He wore a tuxedo on stage,

and had only the barest trace of hillbilly nasality in his voice.

Perhaps the city of Nashville exerted an influence, too. Although

Acuff-Rose and other music companies had made Music Row the

symbol of Nashville everywhere else in the country, it was an

embarrassment to Nashville society. When a Tennessee governor in

the mid-1940s was quoted as saying, ‘‘hillbilly music is disgraceful,’’

Roy Acuff responded by announcing his candidacy for governor (he

never followed through), but there was a growing feeling that

country’s image should not be too raw or ‘‘low-class.’’ So while

rhythm and blues performers responded to rock ’n’ roll by joining it,

the country establishment rejected it. This was the first of a series of

decisions that had the effect of marginalizing what might have

become America’s dominant musical style. The country establish-

ment has always sought status and recognition, but until the 1990s, it

consistently made the wrong choices in following that ambition. As

rock ’n’ roll’s hard edge took over not only the United States but the

world, country music became softer and smoother. Brilliant musi-

cians and producers, such as guitar virtuoso Chet Atkins, pooled their

considerable talents and came up with The Nashville Sound, a string-

sweetened Muzak that was suited to the stylings of Arnold, Jim

Reeves, and Patsy Cline, but not to the grittiness of Presley, Perkins,

Lewis, and Cash.

COUNTRY MUSIC ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

620

Contrary to the popular stereotype, country music has not always

been associated with political conservatism. One of the Opry’s first

stars, Uncle Dave Macon, was a fiery radical leftist. Even Gene Autry,

early in his career, recorded ‘‘The Death of Mother Jones,’’ a tribute

to the legendary left-wing labor organizer. But New Deal populism

was replaced, over the years, by entrenched racism, Cold War

patriotism, and the growing generation gap. By the 1960s, youth,

rebellion, and rock ’n’ roll were on one side of a great divide, and

country music was on the other.

The anthems of 1960s country conservatism were Merle Hag-

gard’s anti-hippie ‘‘Okie From Muskogee’’ and chip-on-the-shoulder

patriotic ‘‘Fightin’ Side of Me.’’ But Haggard, an ex-convict who had

been in the audience when Johnny Cash recorded his historic live

album at Folsom Prison, represented his own kind of rebellion. Along

with Buck Owens, Haggard had turned his back on not only the

Nashville Sound but Nashville itself, setting up their own production

center in the dusty working-class town of Bakersfield, California, and

making music that recaptured the grittier sound of an earlier era.

Haggard and Owens, for all their right-wing posturing, were adopted

by the rockers. The Grateful Dead recorded Haggard’s ‘‘Mama

Tried,’’ and Creedence Clearwater Revival sang about ‘‘listenin’ to

Buck Owens.’’

The conservative cause stood in staunch opposition to the

women’s movement, but in the 1960s women gained their first major

foothold in country music. There had been girl singers before, even

great ones like Patsy Cline, but now Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette,

and especially Dolly Parton established themselves as important

figures. Lynn and Parton wrote their own songs, often with incisive

lyrics about the female experience, and Parton handled much of her

own production. Country music has been described as ‘‘the voice of

the inarticulate,’’ and these singers gave a powerful voice to a

segment of the population that had never had their dreams and

struggles articulated in this way.

The Nashville establishment was still hitching its wagon to a star

that shone most brightly over Las Vegas. Still distrustful of rebellion

and rough edges, they looked to Vegas pop stars for their salvation. In

1974 and 1975, John Denver and Olivia Newton-John swept the

Country Music Association Awards (Denver was Entertainer of the

Year in 1975). Country’s creative edge moved away from Nashville

to Bakersfield and elsewhere. Singer-songwriters Willie Nelson and

Waylon Jennings grew their hair long and hung out with hippies and

rockers at the Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin, Texas. They

made the country establishment nervous, but it did eventually accept

the so-called Outlaw Movement, and by 1979, Nelson was Entertain-

er of the Year. The real working-class music of the new generation of

Southern whites never got that acceptance. Although the 1950s

rockabilly rebels like Cash, Lewis, and the Everly Brothers now

played country venues, the young rockers still scared Nashville.

There was too much Jimi Hendrix in their music, too much hippie

attitude in their clothes and their hair. The Allman Brothers, Lynyrd

Skynyrd, and others played something called Southern Rock that

could have been called country, but wasn’t. Nevertheless, the kid at

the gas station in North Carolina was listening to them, not to John

Denver or Barbara Mandrell. By cutting them out (along with white

Midwestern working-class rockers like Bob Seger), country music

lost a large portion of its new generation of potential listeners.

The country establishment still sought the Vegas crossover

secret, and they seemed to find it in 1980, when the movie Urban

Cowboy created a craze for yoked shirts and fringed cowboy boots.

Records by artists like Mickey Gilley, Johnny Lee, and Alabama shot

up the pop charts for a short time, but the ‘‘urban cowboy’’ sound was

passing fad, and country music seemed to disintegrate with it. In

1985, The New York Times solemnly declared that country music was

finished as a genre, and would never be revived.

However, it was already being revived, by going back to its

roots. Inspired by the example of George Jones, a country legend

since the late 1950s, who is widely considered to possess the greatest

voice in the history of country music, country’s new generation came

to be known as the New Traditionalists. Some of its most important

figures were Ricky Skaggs, a brilliant instrumentalist who brought

the bluegrass tradition back into the mainstream, Randy Travis, a

balladeer in the style of Jones, the Judds, who revived country

harmony and the family group, and Reba McEntire, who modernized

the tradition of Parton, Wynette, and Lynn, while keeping a pure

country sound. The late 1980s brought a new generation of outlaws,

too, singer-songwriters who respected tradition, but had a younger,

quirkier approach. They included Lyle Lovett, Nanci Griffith, and

Steve Earle. These musicians gained a following (Earle, who self-

destructed on drugs, but gradually rebuilt a career in the 1990s,

remains the most influential songwriter of the era). However, country

radio, the center of the country establishment, gave them little air

time, and they moved on to careers in other genres.

There had always been country performers on television, Ten-

nessee Ernie Ford in the 1950s, Glen Campbell and Johnny Cash in

the 1960s, and Barbara Mandrell in the ‘‘urban cowboy’’ days of the

early 1980s. The 1980s also brought cable television, and in 1983,

The Nashville Network went on the air with an all-country format of

videos, live music, and interview shows. In 1985, TNN broadcast

country music’s Woodstock—Farm Aid, a massive benefit organized

by Willie Nelson for America’s farm families. TNN broadcast the

entire 12 hours of Farm Aid live, and audiences who tuned in to see

the rock stars like Neil Young and John Mellencamp who headlined

the bill, also saw new country stars like Dwight Yoakam.

The creative energy that drove country music in the 1980s, had

settled into a formula by the 1990s, and it was the most successful

formula the genre had ever seen. In 1989, Clint Black, became the

first performer to combine the traditionalism of Travis and George

Strait, the innovation of Lovett and Earle, and MTV/TNN-era good

looks and video presence. Close behind Black came Garth Brooks.

With Brooks, the resistance to rock which had limited country’s

potential for growth for four decades finally crumbled completely.

Brooks modeled himself after 1970s arena rockers like Journey

and Kiss, and after his idol, Billy Joel. Rock itself was floundering in

divisiveness, and audiences were excited by the new face of country.

In a 1991 interview, Rodney Crowell said, ‘‘I play country music

because I love rock ’n’ roll, and country is the only genre where you

can still play it.’’ Brooks’ second album, Ropin’ The Wind, debuted at

number one on the pop charts, swamping a heavily hyped album by

Guns ’n Roses, rock’s biggest name at that time. Pop music observers

compared the new country popularity to the ‘‘urban cowboy’’ craze,

and many predicted it would fizzle again. However, with country

finally catching up to rock ’n’ roll, 40 years late. Country music had

taken on a lot of the trappings that had been associated with rock—

sexy young singing idols, arena tours, and major promotions. Country

music’s audience had also broadened; the kid at the gas station joined

the country traditionalists and country’s new suburban audience.

Country music has as many faces as American society itself, and no

doubt will keep re-inventing itself with each generation.

—Tad Richards

COVEYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

621

FURTHER READING:

The Country Music Foundation, editors. Country—The Music and

the Musicians. New York, Abbeville Press, 1994.

Hemphill, Paul. The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country

Music. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1970.

Horstman, Dorothy. Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy. Nashville,

Country Music Foundation Press, 1985.

Leamer, Laurence. Three Chords and the Truth. New York,

HarperCollins, 1997.

Malone, Bill C. Country Music USA, Revised Edition. Austin, Uni-

versity of Texas Press, 1985.

Mansfield, Brian, and Gary Graff, editors. Music Hound Country:

The Essential Album Guide. Detroit, Visible Ink, 1997.

Nash, Alana. Behind Closed Doors: Talking With the Legends of

Country Music. New York, Knopf, 1988.

Richards, Tad, and Melvin B. Shestack. The New Country Music

Encyclopedia. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1993.

Cousteau, Jacques (1910-1997)

Jacques Cousteau is the world’s most acclaimed producer of

underwater film documentaries. His adventurous spirit and undersea

explorations, documented in over forty books, four feature films, and

more than one hundred television programs, popularized the study of

marine environments, and made him a household name in many parts

of the world. As principal developer of the world’s first aqualung

diving apparatus and underwater film cameras, he opened up the

world’s waters to millions of scuba divers, film makers, and tele-

vision viewers. A pioneering environmentalist, Cousteau brought

home to the public mind the importance of the world’s oceans and

inspired generations of young scientists to become ecologists

and oceanographers.

Jacques-Yves Cousteau was born on June 11, 1910, in the

market town of St.-Andre-de-Cubzac, France. Following service in

the French Navy, he became commander of the research vessel

Calypso in 1950. The Calypso, where most of his subsequent films

were produced, served as his base of operations. His first book, The

Silent World, sold more than five million copies in 22 languages. A

film of the same name won both the Palme d’Or at the 1956 Cannes

International Film Festival and an Academy Award for best docu-

mentary in 1957. Television programs bearing the Cousteau name

earned 10 Emmys and numerous other awards. In the 1950s and

1960s, Cousteau established a series of corporations and nonprofit

organizations through which he financed his explorations, promoted

his environmental opinions, and championed his reputation as the

world’s foremost underwater researcher and adventurer. He died in

Paris on June 25, 1997.

—Ken Kempcke

F

URTHER READING:

Madsen, Axel. Cousteau: An Unauthorized Biography. New York,

Beaufort, 1986.

Munson, Richard. Cousteau: The Captain and His World. New York,

Morrow, 1989.

Covey, Stephen (1932—)

Stephen Covey, one of America’s most prominent self-help

gurus, owes much to Dale Carnegie, whose best-selling book, How To

Win Friends and Influence People, and its corresponding public

speaking course are models upon which Covey built his success. The

first of numerous books written by Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly

Effective People, was published in 1989 and helped his rise to the

position of unofficial consultant to the leaders of corporate America,

and guru to those in the lower levels of corporate management. His

company, the Covey Leadership Center, founded in 1983, subse-

quently capitalized on the success of 7 Habits, which became a catch

phrase for any number of simplistic and appealing ideas dealing with

personal happiness and efficiency in the workplace.

Covey was born into a Mormon family in Provo, Utah. During

the 1950s he completed a bachelor’s degree in business administra-

tion at the University of Utah and an M.B.A. at Cambridge. In

between his academic studies, he served as a missionary in Nottingham,

England, training the leaders of recently formed Mormon congrega-

tions, and thus became aware of what it meant to train and motivate

leaders. As a result of the particular nature of his training experience,

a combination of religious and family values formed the core of his

programs and writings. Covey taught at Brigham Young University

where, in 1976, he earned a Ph.D. in business and education, but left

that institution in 1983 to start the Covey Leadership Center.

The Center had an immediate, and almost exclusive appeal to the

corporate culture, partly due to its marketing strategies, but also

because of the timbre of the times. Corporate America was in a state

of unease and flux, and workers and managers were ripe for guidance

in their search for a sense of stability in their jobs and careers. The

Covey Leadership Center promised solutions to their problems, and

both managers and employees were as eager to attend Covey’s

programs as the corporate leaders—hoping for improved efficiency

and morale of their personnel—were to send them. When The 7

Habits of Highly Effective People was published, six years after the

inception of the Center, it became hugely popular, appearing on the

New York Times bestseller list for well over five years. The book

stood out from the vast quantity of positive-thinking books available

in the late 1980s, partially because of Covey’s already established

credibility, and partly because, as with the courses and programs,

there was a real need for his particular take on self-help literature. The

sales of the book increased the already sizable interest and enrollment

in his leadership programs. Throughout the 1990s, according to

Current Biography, ‘‘hundreds of corporations, government agen-

cies, and universities invited Covey to conduct seminars with, or

present talks to, their employees.’’

While many people attended these seminars and workshops, it is

the 7 Habits book that defines Stephen Covey’s identity as a self-help

guru. Initially an integral part of corporate management literature, the

appeal of Covey’s message, as transmitted in his book, spread to

people in all walks of life. Its popularity was such that magazine and

newspaper editors, in their bids to increase circulation, would play on

the ‘‘Seven Habits’’ theme in headlines and articles in much the same

way that the title of Robert Pirsig’s novel Zen and the Art of

Motorcycle Maintenance spawned countless sophomoric imitations

in the print media.

Stephen Covey was the first to admit that there is nothing new in

his writing; indeed the very simplicity of his philosophy has account-

ed both for its popular acclaim, and for the not insubstantial negative

COWBOY LOOK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

622

criticism it has attracted in certain quarters. Each ‘‘habit’’ presented

in the book (‘‘Be proactive,’’ ‘‘Begin with the end in mind,’’ ‘‘Put

first things first’’) draws on time-tested truisms and age-old common-

sense principles. Covey’s fans applauded him for putting these adages

into print, in a useful modern context; detractors blasted him for

repackaging well-worn and well-known information. Covey himself

claimed that his book is based on common sense ideas, but that they

needed to be restated, because, as he said in an interview in the

Orange County Register, ‘‘. . . [W]hat is common sense isn’t

common practice.’’ Another criticism frequently leveled at Covey is

that, in his effort to show that each person is responsible for his or her

own success, he trivializes the effects that flaws in the larger corpo-

rate system may have on performance. Thus, any failure is blamed

only on the individual.

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People has transcended the

corporate world and entered into the American collective psyche. The

Covey Leadership Center, which merged with the Franklin Quest

Company in 1997 to form the Franklin Covey Co., has turned itself

into a cottage industry, supplying customers with all manner of

related merchandise: magazines, audiotapes, videos, and, perhaps

most pervasively, ‘‘day-planners’’. Once the chief product of the

Franklin Quest company, these trendy signs-of-the-times began, after

the merger, to include quotes from Covey’s books. In addition to the 7

Habits book, Covey wrote a number of other books on related topics,

including First Things First, and Principle-Centered Leadership. In

1997, he published a ‘‘follow-up’’ to his popular book, entitled The 7

Habits of Highly Effective Families, which promptly landed on the

New York Times best-seller list. Redirecting the thrust of his wisdom

towards problems between family members, Covey seemed to antici-

pate the changing mood and tone of America, which, in the wake of

contradictory political messages, had become, by the late 1990s, more

concerned with ‘‘family values.’’

Stephen Covey is, perhaps, not quite a household name, but the

‘‘7 Habits’’ phrase, and the concept and book from which it origi-

nates, has become an emblem of the American people’s desire for

stability and self-improvement, in their careers and in their personal

lives. It represents the people’s search for an antidote to the confusing,

contradictory and often disturbing events in the corporate and politi-

cal worlds during the 1990s. The extent to which ‘‘7 Habits’’ has

permeated the culture shows a desire, in the face of growing and

changing technology, for simple truths, and for courses of action that

can be easily understood and executed.

—Dan Coffey

F

URTHER READING:

Covey, Stephen R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Families:

Building a Beautiful Family Culture in a Turbulent World. New

York, Golden Books, 1997.

———. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York, Simon

& Schuster, 1992.

Current Biography. New York, H.W. Wilson. January, 1998, 19-21.

Smith, Timothy K. “What’s So Effective About Stephen Covey?”

Fortune. December 12, 1994, 116-22.

Walker, Theresa. “Stephen Covey.” The Orange County Register.

March 3, 1998.

Wolfe, Alan. “Capitalism, Mormonism, and the Doctrine of Stephen

Covey.” The New Republic. February 23, 1998, 26-35.

The Cowboy Look

The cowboy look is a fanciful construction of an ideal cowboy

image. Originally, cowboy clothing provided primarily function over

fashion, but through America’s century-long fascination with this

romantic Great Plains laborer, image has surpassed reality in what a

cowboy ought to look like. With the supposed closing of the frontier

at the end of the nineteenth century, the ascendancy of the Cowboy

President, Theodore Roosevelt, and the growing popularity of artists

such as Frederick Remington and Charley Russell, who reveled in a

nostalgia for cowboy life, wearing cowboy clothes became akin to a

‘‘wearing of history’’ as twentieth-century Americans tried to hold

onto ideals of individualism, opportunity, and adventure supposedly

tied to the clothes’ frontier heritage.

Of primary importance in the construction of cowboy fashion

are the highly stylized cowboy boots. A mass-produced and mail-

order footwear near the turn of the century, these boots protected

against rough vegetation with their durable cowhide uppers and

provided ease of movement in and out of stirrups with their flat soles

and high wooden heels. As cowboys became heroes through the

massive popularity of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show during the late

nineteenth and early twentieth century and later through Hollywood

films, cowboy clothing came into vogue in popular culture. Boots in

particular started to assume a sense of personalized fashion as

specialized bootmakers cropped up in the West, especially in Texas.

These bootmakers produced boots from hides as far-ranging as

ostrich, elephant, eel, or stingray. The fancy stitching, colored leather,

and occasional inlaid precious stone lent these custom boots an air of

fashionable individuality. Custom cowboy boots, among those wealthy

enough to afford them, became a distinctive mark of an individual’s

flair combined with a sense of Western spirit.

But cowboy boots were only a single part of Western fashion

popular throughout most of the twentieth century. Necessary fashion

accouterments included denim jeans, a Western shirt (usually with

designs on the shoulders), large belt buckles, and a broad-brimmed

cowboy hat. This fashion remained essentially the same, barring

various preferences for shirt designs and boot styles, throughout the

twentieth century. Early Western film stars like William S. Hart and

Tom Mix popularized the cowboy look, perpetuating the myth of the

cowboy hero (always clad in a white hat) over the image of the ranch

hand laborer. From the 1930s to the mid-1950s, the cowboy look

found immense popularity among children. This trend coincided with

the popularity of cowboy movie stars and singers Gene Autry and Roy

Rogers who, according to Lonn Taylor and Ingrid Maar in The

American Cowboy, acted as surrogate fathers for children whose

fathers were away fighting in World War II. As television Westerns

became more popular in America in the 1950s, the image of a noble

and righteous cowboy fighting for justice and ideological harmony on

the American frontier found a resurgence once again as America

turned its attention to the Cold War.

Along with the popularity of the cowboy look from 1950s

television, country music’s presence in popular culture became

notable; though most country music from this era sprang from the

South, the fashion of the time was essentially Western and demanded

cowboy boots and hats. But with the popularity of rock ’n’ roll during

the late 1950s and 1960s, cowboy fashion faded from the mainstream

of popular culture. By the early 1970s, however, the boots, hats, tight

jeans, and plaid work shirts of cowboy fashion started to appear in

more urban settings. Growing from the seemingly timeless myth of

COWBOY LOOKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

623

John Travolta and Madolyn Smith in a scene from the film Urban Cowboy that illustrates the cowboy look.

the cowboy loner—epitomized in 1902 by Owen Wister’s The

Virginian—, the cowboy look now hit city streets less as a costume

and more as a fashion statement. This look culminated with the 1980

release of Urban Cowboy, starring John Travolta as an unlikely

cowboy figure who finds romance and country dancing in late 1970s

Texas honky tonks.

The cowboy look also benefitted from the resurgence in the

popularity of country music music between the mid-1980s and the

mid-1990s. Without any major changes in the foundations, the

cowboy look became the Western look, incorporating into the basic

clothes some Hollywood glitz and rhinestones, Southwestern Hispan-

ic and Native American styles such as silver and turquoise, and a new

kind of homegrown, rural sensibility. The jeans became tighter, the

shirts louder, and hats took on the personalized importance of boots.

As country music became more popular, huge Western clothing

super-stores opened throughout America dedicated solely to supply-

ing the fashion needs of country music’s (and country dancing’s)

new devotees.

The icon of Western fashion could no longer be found in movies.

Instead, country music stars such as George Strait or Reba McEntire

presented the measure for the new cowboy look. The new cowboy

look did not focus on the Western hero, the knight in the white hat so

popular in the early part of the century, but rather was aimed at the

American worker who gets duded-up to play on the weekend. This

new cowboy look was used to sell fishing equipment and especially

pick-up trucks to people aspiring toward country or Western life-

styles. Though this country look still appeared as a ‘‘wearing of

history,’’ its devotees found in this new fashion a distillation of the

American work ethic (that allowed for outlets on Friday and Saturday

nights) that had supposedly grown from a country ranching and

farming lifestyle. The cowboy look no longer represented the hero,

but the American rural laborer, albeit in an overly sanitized fashion.

Like the popular country music that spurred this fashion trend, the

cowboy look now affected rural authenticity over urban pretensions,

valued family and the honor of wage labor, and, like its earlier

permutations, elevated American history and culture over any

other traditions.

—Dan Moos

F

URTHER READING:

Beard, Tyler. The Cowboy Boot Book. Layton, Utah, Gibbs Smith, 1992.

Savage, William W., Jr., The Cowboy Hero: His Image in American

History and Culture. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1979.

Taylor, Lonn, and Ingrid Maar. The American Cowboy. New York,

Harper and Row, 1983.

COX ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

624

Cox, Ida (1896-1967)

Billed as the ‘‘Uncrowned Queen of the Blues,’’ Ida Cox (born

Ida Prather) never achieved the fame of her contemporaries Bessie

Smith and Gertrude ‘‘Ma’’ Rainey. Though she spent most of the

1920s and 1930s touring the United States with various minstrel

troupes, including her own ‘‘Raisin’ Cain Revue,’’ she also found

time to record seventy-eight sides for Paramount Records between

1923 and 1929. Among these was her best known song, ‘‘Wild

Women Don’t Have the Blues,’’ which was identified by Angela

Y. Davis as ‘‘the most famous portrait of the nonconforming,

independent woman.’’

Noted record producer John Hammond revitalized Cox’s career

by highlighting her in the legendary ‘‘Spirituals to Swing’’ concert at

Carnegie Hall in 1939. Cox continued her recording career until she

suffered a stroke in 1944. Six years after a 1961 comeback attempt

that produced the album Blues for Rampart Street, Ida Cox died

of cancer.

—Marc R. Sykes

F

URTHER READING:

Davis, Angela Y. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude

‘‘Ma’’ Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York,

Pantheon, 1998.

Harrison, Daphne Duval. Black Pearls: Blues Queens of the 1920s.

New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1988.

Cranston, Lamont

See Shadow, The

Crawford, Cindy (1966—)

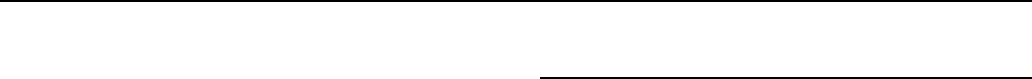

Beginning in the 1980s and continuing through the 1990s, Cindy

Crawford was America’s most celebrated fashion model and one of

the most famous in the world, embodying the rise of the ‘‘super

model’’ as a late twentieth century cultural phenomenon. Although

there had been star models in previous decades—Twiggy in the

1960s, for example, or Lauren Hutton and Cheryl Tiegs in the

1970s—they did not sustain prolonged mainstream recognition. Cin-

dy Crawford and her contemporaries (Kate Moss and Naomi Camp-

bell among them) no longer merely posed as nameless faces on

magazine covers, calendars, and fashion runways but, rather, became

celebrities whose fame rivaled that of movie stars and rock musicians.

Cindy Crawford stood at the forefront of this insurgence.

Although she found fame through her physical appearance, the

brown-haired, brown-eyed Crawford first distinguished herself through

her intellectual attributes. A native of DeKalb, Illinois, who was born

Cynthia Ann Crawford on February 20, 1966, she was a fine student

and class valedictorian at her high school graduation. She enrolled in

Chicago’s Northwestern University to take a degree in chemical

engineering, but her academic career proved short-lived when, during

her freshman year, she left college to pursue a modeling career. Her

entrance into the tough, competitive world of high fashion was eased

by her winning the ‘‘Look of the Year’’ contest held by the Elite

Cindy Crawford

Modeling Agency in 1982. Within months the statuesque (five-foot-

nine-and-a-half inches), 130-lb model was featured on the cover

of Vogue.

The widespread appeal of Cindy Crawford lay in looks that

appealed to both men and women. Her superb body, with its classic

34B-24-35 measurements, attracted men, while her all-American

looks and trademark facial mole stopped her short of seeming an

unattainable ideal of perfect beauty, and thus she was not threatening

to women. Furthermore, her athletic physique was in distinct contrast

to many of the overly thin and waif-like models, such as Kate Moss,

who were prevalent during the 1990s.

Cindy Crawford stepped off the remote pedestal of a celebrity

mannequin or a glamorous cover girl when she began to assert her

personality before the public. She gave interviews in which she

discussed her middle-class childhood, her parents’ divorce, and the

trauma of her brother’s death from leukemia. These confessions

humanized her image and made her approachable, and she went on to

host MTV’s House of Style, a talk show that stressed fashion and

allowed her to conduct interviews that connected with a younger

market. The Cindy Crawford phenomenon continued with her in-

volvement in fitness videos, TV specials, commercial endorsements,

and film (Fair Game, 1995, was dismissed both by audiences and

critics, but did little to diminish her popularity.) Meanwhile, her

already high profile increased with her brief 1991 marriage to actor

Richard Gere. The couple was hounded by rumors of homosexuality,

fuelled after Crawford appeared on a controversial Vanity Fair cover

with the openly lesbian singer k.d. lang. She later wed entrepreneur

Rande Gerber.

CRAWFORDENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

625

After the arrival of Cindy Crawford, it was not uncommon to see

models promoting a vast array of products beyond fashion and

cosmetics. Crawford herself signed a multi-million dollar deal to

promote Pepsi, as well as her more conventional role with Revlon.

Her status was so high that ABC invited her to host a special on teen

sex issues with the provocative title of Sex with Cindy Crawford. The

opening of the Fashion Café theme restaurant in the mid-1990s

marked the height of the super model sensation sparked by Crawford.

The café’s association with Crawford and other high profile models

revealed the extent to which the ‘‘super model’’ had become a major

figure in American culture. By the end of the twentieth century, Cindy

Crawford was still the best known of these celebrities due to the

combination of her wholesomely erotic image and her professional

diversification through the many available media outlets.

—Charles Coletta

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Cindy.com.’’ http://www.cindy.com. April 1999.

Crawford, Cindy. Cindy Crawford’s Basic Face. New York, Broad-

way Books, 1996.

Italia, Bob. Cindy Crawford. Edina, Minnesota, Abdo and Daugh-

ters, 1992.

Crawford, Joan (1904?-1977)

From her 1930s heyday as a leading MGM box-office draw, to

her 1962 performance in the horror classic and cult favorite Whatever

Happened to Baby Jane?, Joan Crawford incarnated, in the words of

Henry Fonda, ‘‘a star in every sense of the word.’’ The MGM style of

star packaging emphasized glamour, and Crawford achieved her

luminous appearance through an extensive wardrobe and fastidious

presentations of her gleaming, trademark lips, arched eyebrows,

sculpted cheek and jaw bones, and perfectly coiffured hair. Crawford

herself famously said, ‘‘I never go out unless I look like Joan

Crawford the movie star. If you want to see the girl next door, go

next door.’’

Born Lucille LeSueur in San Antonio, Texas, on March 23,

1904, Crawford embarked on a dancing career when only a teenager.

She worked cabarets and travelling musical shows until her discovery

in the Broadway revue The Passing Show of 1924. It would not be

long before an MGM executive noted her exuberant energy and

athletic skill. Exported to Hollywood on a $75.00/week contract,

Lucille changed her name as part of a movie magazine promotion that

urged fans to ‘‘Name Her and Win $1,000.’’ This early link between

her professional life and fan magazines presaged a union that would

repeatedly shape her long movie star tenure. Throughout five dec-

ades, she appeared in magazine advertisements endorsing cosmetics,

food products, and cigarettes. She dutifully answered fan letters and

once fired a publicity manager who turned away admirers at her

dressing room door. Her first marriage to Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.,

turned into a publicity spectacle. It was a reported feud between

Crawford and co-star Bette Davis that was used to generate interest in

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? A conflation of Crawford’s roles

and fan magazine publicity with her personal life formed both the

public view of her and her own sense of identity.

Joan Crawford

Crawford garnered her first film role in 1925 and made over 20

silent pictures before 1929, the year of her first hit Untamed. Her early

career coincided with Hollywood’s investment in the production and

cultivation of stars as bankable assets. One of the industry’s earliest

successes, Crawford mutated her star persona over the decades to

retain currency. Her first image was as a ‘‘flapper,’’ a 1920s free-

spirited woman who danced all night in speakeasies and jazz clubs. In

the 1928 movie Our Dancing Daughters, Crawford’s quintessential

flapper whips off her party dress and dances the Charleston in her slip.

Her date asks, ‘‘You want to take all of life, don’t you?’’ Crawford’s

character replies, ‘‘Yes—all! I want to hold out my hands and catch at

it.’’ Crawford’s own dance-till-dawn escapades frequently provided

fodder for the gossip columns.

In the wake of the Depression Crawford transformed into a

1930s ‘‘shopgirl’’—a willful, hard-working woman determined to

overcome adversity, usually on the arm of a wealthy, handsome man

played by the likes of Clark Gable or second husband, Franchot Tone.

With this new character type, song-and-dance movies gave way to

melodramatic fare, in which she uttered lines like this one from the

1930s movie Paid: ‘‘You’re going to pay for everything I’m losing in

life.’’ To encourage fan identification with Crawford’s ‘‘shopgirl’’

image, MGM promoted Crawford’s own hard-luck background,

highlighting her travails as a clerk at a department store in Kansas

City, Missouri. In 1930, she was voted most popular at the box office.

Inherent to this genre was a literal rags-to-riches metamorphosis.

Possessed, produced in 1931, begins with Crawford working a

factory floor in worn clothing and charts her rise in status through

increasingly extravagant costume changes. This particular formula

CRAY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

626

teamed her with haute couture designer Adrian, and together they

sparked fashion trends. In Paid, Crawford dons a huge, black fur-

collared coat that, by virtue of her appearance in it, turned into a best-

selling item in clothing stores along fifth Avenue in New York. The

most famous instance occurred in 1932 with the Letty Lynton dress,

reportedly the most frequently copied film-gown in American mov-

ies. Featuring enormous, ruffled sleeves and layers of white organdy,

the Letty Lynton dress-craze confirmed Hollywood’s place as show-

case for fashion. The Letty Lynton phenomenon also marked the

debut of Crawford’s clothes-horse image. The importance of how

Crawford looked in a movie soon eclipsed the significance of how

she acted.

Crawford’s popularity diminished in the 1940s as younger

actresses claimed the best MGM parts. She responded by retooling

herself into a matriarchal, self-sacrificing businesswoman, her strength

symbolized by shoulder pads and dramatically tailored suits. To

brook this transition, Crawford departed glamour-factory MGM in

1943 and signed with the crime picture studio, Warner Brothers. The

role of the driven self-made restaurateur in the 1945 film noir,

Mildred Pierce, earned her an Academy Award for Best Actress. At

the end of this period, she began portraying desperate, emotionally

disturbed women like the lover-turned-stalker Possessed (1947), and

the neat-freak homemaker whose obsession turns to madness in the

title role of Harriet Craig (1950). Movie culture in the 1950s

expressed anxiety over dominant, self-sufficient female roles, popu-

lar in World War II and immediate post-War America, by straight-

jacketing Crawford—literally—in Straight Jacket, produced by ‘‘B’’

horror film king William Castle in 1964. The 1960s limited her to

cheap horror films—I Saw What You Did, Beserk, Trog—and traded

on her now severe, lined face and its striking contrast with her trim,

dancer’s figure. Crawford’s late career also ushered in the Hollywood

use of product placement. As an official representative of Pepsi-

Cola—her fourth and last husband, Howard Steele, was a Pepsi

executive—Crawford featured displays of Pepsi-Cola signs and mer-

chandise in several of her last films. For example, while probing a

series of ghoulish murders at a circus owned by Crawford in a scene

from Beserk (1968), investigators pause under a ‘‘Come Alive! With

Pepsi’’ banner.

In Mommie Dearest, a movie based on an expose written by

Crawford’s adopted daughter and featuring Faye Dunaway, Crawford

is depicted as a bizarrely cruel disciplinarian. The movie not only

made a horrific joke of Crawford, but it also maligned Dunaway’s

acting ability. Portions of the movie became staple skits on late-night

television shows like the satiric Saturday Night Live. The 1980s and

1990s, however, turned her into a favorite icon of gays and lesbians

with Internet websites celebrating her masculine performances in, for

example, Johnny Guitar (1954). In this movie she plays a gun-belted,

top-booted saloon keep whose show-down is against another man-

nish-looking woman.

—Elizabeth Haas

F

URTHER READING:

Considine, Shaun. Bette & Joan: The Divine Feud. New York, E.P.

Dutton, 1989.

Gledhill, Christine, editor. Stardom: Industry of Desire. New York,

Routledge, 1991.

Thomas, Bob. Joan Crawford: A Biography. New York, Simon &

Schuster, 1978.

Walker, Alexander. Joan Crawford: The Ultimate Star. London,

Weidenfeld & Nicholson Ltd., 1983.

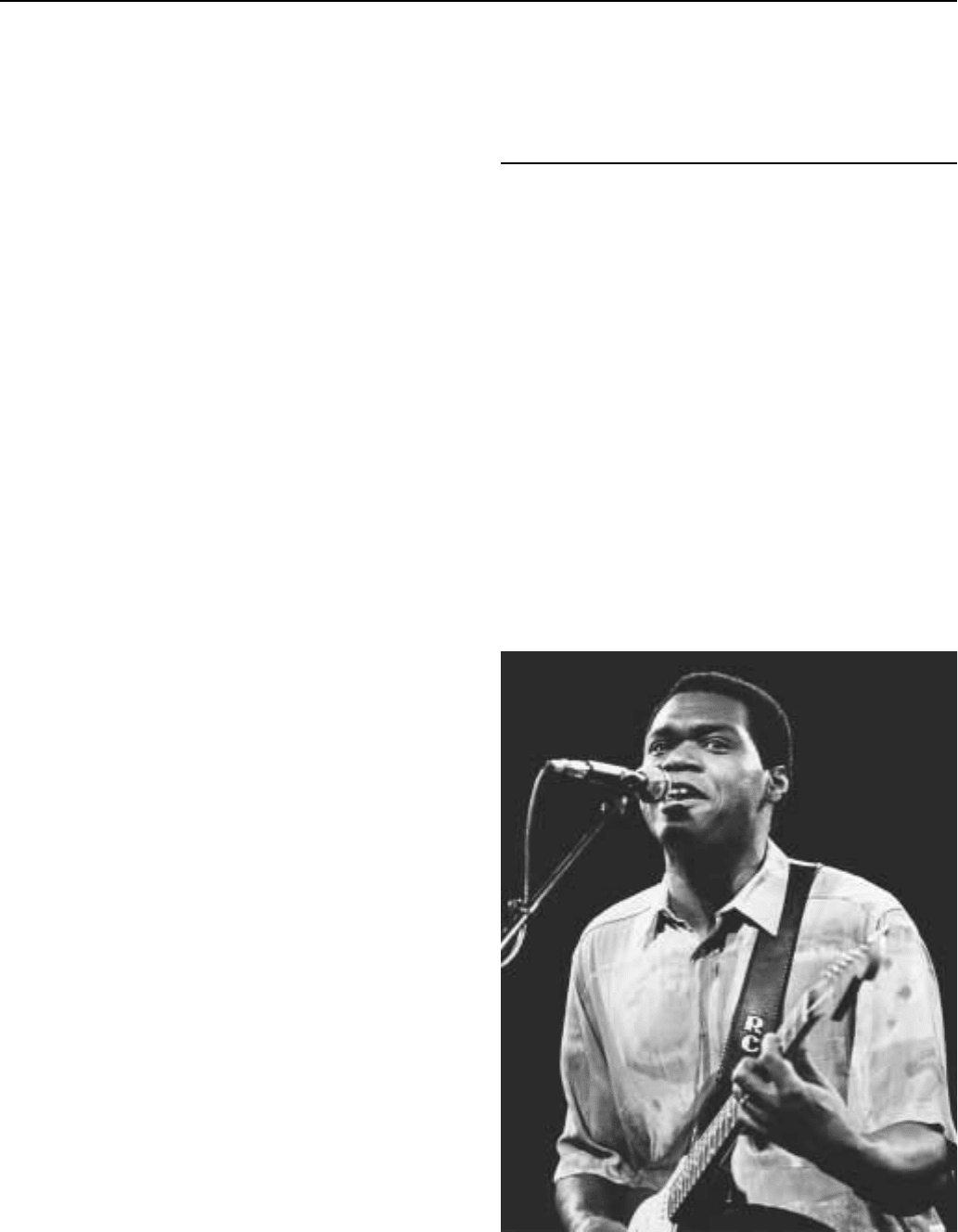

Cray, Robert (1953—)

Robert Cray’s fusion of blues, R & B, jazz, pop, and soul music

earned him critical acclaim and widespread recognition as a critical

figure in the ‘‘blues boom’’ of the 1980s and 1990s. Indeed, his

original approach to the genre brought an entirely new audience to

what had been considered a dying art form. Though blues purists

dismissed him as a ‘‘tin-eared yuppie blues wannabe,’’ Cray nonethe-

less enjoyed success unmatched by any other blues artist.

Born into an army family in 1953, Cray had the opportunity to

live in many different regions of the United States before his family

settled in Tacoma, Washington, when Cray was fifteen years old.

Already a devotee of soul and rock music, Cray became interested in

blues after legendary Texas guitarist Albert Collins played at his high

school graduation dance. Cray formed his first band in 1974, and this

group eventually became Collins’s backing band, touring the country

with him before striking out on its own.

After a series of moves—to Portland, Seattle, and finally to San

Francisco—the Robert Cray Band signed a record deal with Tomato

Records and released its first album, Who’s Been Talking? (later re-

released as Too Many Cooks), in 1980. Though the album featured

convincing performances of classic blues songs, it generated little

excitement. Cray and his band subsequently toured with Chicago

Robert Cray

CREATIONISMENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

627

legend Muddy Waters and were featured on the Kings of the Boogie

world tour with John Lee Hooker and Willie Dixon.

In 1983, Cray tried a different approach with the funky, original

Bad Influence, released on the HighTone label. His follow-up effort,

False Accusations, proved to be the breakthrough. The album made

Newsweek’s list of top ten LPs and shot up to number one on the

Billboard pop music charts. That same year, Alligator Records

released the Grammy Award-winning Showdown!, which featured

Cray collaborating with now-deceased blues guitarists Collins and

Johnny Copeland.

Success earned Cray the support of a major label, Mercury, and

his debut effort for the company is widely believed to be the best work

of his career. Released in 1986, Strong Persuader was certified

platinum (sales of more than one million copies) and put Cray’s

picture on the cover of Rolling Stone. The success of the album also

ensured more high-profile collaborations, such as an appearance in

the concert and film tribute to Chuck Berry, ‘‘Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’

Roll!’’ produced by Keith Richards. After covering Cray’s ‘‘Bad

Influence’’ on his August album, Eric Clapton invited Cray to appear

on his Journeyman and 24 Nights albums. Cray also appeared in the

Tina Turner video ‘‘Break Every Rule,’’ becoming a familiar face on

the MTV network.

Cray continued to experiment with soul music on 1990’s Mid-

night Stroll, which featured the legendary Memphis Horns, and

showed a jazzier side on I Was Warned, released two years later.

Albert Collins joined Cray and his band on the 1993 album Shame + a

Sin, the most traditional of Cray’s later works. Cray continued to be in

demand as a guest performer, appearing on three John Lee Hooker

albums including the Grammy-winning The Healer, as well as B. B.

King’s Blues Summit. Cray’s 1997 release Sweet Potato Pie featured

a return to the Memphis soul that had characterized his sound from the

early 1980s. Despite being panned by the ‘‘bluenatics,’’ as Cray

labelled the blues purists, the album achieved significant sales,

confirming Cray’s continuing commercial viability.

—Marc R. Sykes

F

URTHER READING:

Davis, Francis. The History of the Blues. New York, Hyperion, 1995.

Russell, Tony, ed. The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray.

New York, Schirmer, 1997.

Creationism

Creationism is a Christian doctrine holding that the world and

the living things in it—human beings in particular—were created by

God. There have been a variety of creationist viewpoints, and some of

these viewpoints are in conflict with mainstream scientific theories,

especially the theory of evolution.

After Charles Darwin published his Origin of Species (1859),

which not only defended the pre-existing theory of evolution but also

maintained that evolution took place through natural selection, many

fundamentalist Christians reacted with horror. Then as now, anti-

evolutionists maintained that evolution was contrary to the Bible, that

it was atheistic pseudo-science, and that, by proposing that man

descended from lower animals, it denied man’s spiritual nature.

Evolutionists denounced creationists for allegedly misinterpreting

both the Bible and the scientific evidence.

In the 1920s, William Jennings Bryan, a former Nebraska

Senator, Presidential candidate, and U.S. Secretary of State, joined

the movement to prevent the teaching of evolution. In response to

lobbyists like Bryan, the state of Tennessee passed a law making it a

crime for a public-school teacher or state college professor to teach

the allegedly un-Scriptural doctrine that man evolved from a lower

order of animals. However, under the Butler Act (and similar laws in

other states), it remained permissible to teach the theory of evolution

as applied to species other than humans.

A test case of the Tennessee law was arranged in Dayton,

Tennessee, in 1925. A teacher named John Thomas Scopes was

charged with violating the law. Bryan was brought in to help the

prosecution, and an all-star legal defense team, including famed

attorney Clarence Darrow, was brought in to defend the young

teacher. Scopes was convicted after a highly-publicized trial, but his

conviction was overturned on a technicality by the Tennessee Su-

preme Court. A play based on the Scopes Monkey trial, Inherit the

Wind, was turned into a movie in 1960. Spencer Tracy, Gene Kelly,

and Frederic March were among the cast of this popular and anti-

creationist rendering of the trial. The movie altered some of the

historical details, but the movie version of the trial was probably

better-known than the actual trial.

Arkansas had also passed a ‘‘monkey law’’ similar to Tennes-

see’s Butler Act. In 1968, the United States Supreme Court ruled that

the Arkansas law was designed to promote religious doctrine, and that

therefore it was an unconstitutional establishment of religion which

violated the First Amendment. The Epperson decision had no effect

on the Tennessee Butler law, since that law had been repealed in 1967.

Since the Scopes trial, the views of some creationists have been

getting closer to secular scientific position. Scientists who were

evangelical Christians formed an organization called the American

Scientific Affiliation (ASA) during World War II. ASA members

pledged support for Biblical inerrancy and declared that the Christian

scriptures were in harmony with the evidence of nature. Within this

framework, however, the ASA began to lean toward the ‘‘progressive

creation’’ viewpoint—the idea that God’s creation of life was accom-

plished over several geological epochs, that the six ‘‘days’’ of

creation mentioned in Genesis were epochs rather than literal days,

and that much or all of mainstream science’s interpretation of the

origins of life could be reconciled with the Bible. These ‘‘progressive

creation’’ tendencies were articulated in Evolution and Christian

Thought Today, published in 1959. Some of the contributors to this

volume seemed to be flirting with evolution, with two such scientists

indicating that Christian doctrine could be reconciled with something

resembling evolution.

Other creationists moved in another direction entirely—towards

‘‘flood geology.’’ This is the idea that God had created the world in

six 24-hour days, that all species, including man, had been specially

created, and that the fossil record was a result, not of evolution over

time but of a single catastrophic flood in the days of Noah. George

McCready Price, a Canadian-born creationist, had outlined these

ideas in a 1923 book called The New Geology. At the time, Price’s

ideas had not been widely accepted by creationists outside his own

Seventh Day Adventist denomination, but in 1961 Price’s ideas got a

boost. Teacher John C. Whitcomb, Jr. and engineer Henry M. Morris

issued The Genesis Flood, which, like The New Geology, tried to

reconcile the geological evidence with a strong creationist viewpoint.

In 1963, the Creation Research Society (CRS) was formed. The

founders were creationist scientists (many of them from the funda-

mentalist Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod), and voting membership

CREDIT CARDS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

628

was limited to scientists. The CRS was committed to Biblical inerrancy

and a creationist interpretation of the Bible, an interpretation which in

practice coincided with the doctrine of flood geology.

The CRS and others began lobbying for the inclusion of creationist

ideas in school curricula. This was a delicate task, on account of the

Epperson decision of the Supreme Court, which prohibited the

introduction of religious doctrines into the curriculum of the public

schools. Creationists campaign all over the country, trying to get

creationism (now often dubbed ‘‘creation science’’) into textbooks on

an equal basis with evolution. Some states allowed the use of

creationist texts like Henry M. Morris’ Scientific Creationism. The

Texas Board of Education required that textbooks used by the state

must emphasize that evolution was merely a theory, and that other

explanations of the origins of life existed. On the other hand,

California—which together with Texas exerted a great influence over

educational publishers due to its mass purchasing of textbooks—

rejected attempts to include creationism in school texts.

Laws were passed in Arkansas and Louisiana requiring that

creation science get discussed whenever evolution was discussed.

However, the federal courts struck down these laws. The U.S.

Supreme Court struck down the Louisiana law in 1987, on the

grounds that creation science was a religious doctrine that could not

constitutionally be taught in public schools.

In Tennessee, home of the Scopes trial, the legislature passed a

law in 1973 which required that various ideas of life’s origin—

including creationism—be included in textbooks. A federal cir-

cuit court struck down this law. An 1996 bill in the Tennessee

legislature, authorizing school authorities to fire any teacher who

taught evolution as fact rather than as theory, was also unsuccessful.

But in Tennessee and other states, the campaign for teaching

creationism continues.

—Eric Longley

F

URTHER READING:

de Camp, L. Sprague. The Great Monkey Trial. Garden City, New

York, Doubleday, 1968.

Edwards v. Aguilland, 482 U.S. 578 (1987).

Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968).

Harrold, Francis B., and Raymond A. Eve, editors. Cult Archeology &

Creationism. Iowa City, University of Iowa Press, 1995.

Irons, Peter. The Courage of Their Convictions. New York, Free

Press, 1988.

Johnson, Robert C. ‘‘70 Years After Scopes, Evolution Hot Topic

Again.’’ Education Week. March 13, 1996.

———. ‘‘Tenn. Senate to Get New Chance to Vote on Evolution

Measure.’’ Education Week. March 27, 1996.

Kramer, Stanley, producer and director. Inherit the Wind, motion

picture (original, 1960). Culver City, California, MGM/UA Home

Video, 1991.

Lawrence, Jerome, and Robert E. Lee. Inherit the Wind. New York,

Random House, 1955.

Mitchell, Colin. The Case for Creationism. Grantham, United King-

dom, Autumn House, 1995.

Numbers, Ronald L. The Creationists. New York, Borzoi, 1992.

Sommerfeld, Meg. ‘‘Lawmakers Put Theory of Evolution on Trial.’’

Education Week. June 5, 1996.

Webb, George E. The Evolution Controversy in America. Lexington,

University Press of Kentucky, 1994.

Credit Cards

The small molded piece of polyvinyl chloride known as the

credit card has transformed the American and the world economy and

promises to be at the heart of the future economic system of the world.

Social scientists have long recognized that the things people buy

profoundly affect the way they live. Microwave ovens, refrigerators,

air conditioners, televisions, computers, the birth control pill, antibi-

otics—all have affected peoples’ lives in profound ways. The credit

card has changed peoples’ lives as well, for it allows unprecedented

access to a world of goods. The emergence of credit cards as a

dominant mode of economic transaction has changed the way people

live, the way they do things, the way they think, their sense of well

being, and their values. When credit cards entered American life,

ordinary people could only dream of an affluent life style. Credit

cards changed all that.

Credit cards were born in the embarrassment of Francis X.

McNamara in 1950. Entertaining clients in a New York City restau-

rant, Mr. McNamara reached for his wallet only to find he had not

brought money. Though his wife drove into town with the money,

McNamara went home vowing never to experience such disgrace

again. To guarantee it, he created the Diners Club Card, a simple

plastic card that would serve in place of cash at any establishment that

agreed to accept it. It was a revolutionary concept.

Of course, credit had long been extended to American consum-

ers. Neighborhood merchants offered credit to neighborhood custom-

ers long before McNamara’s embarrassing moment. In the 1930s oil

companies promoted ‘‘courtesy cards’’ to induce travelers to buy gas

at their stations across the country; department stores extended

revolving credit to their prime customers. McNamara’s innovation

was to create a multipurpose (shopping, travel, and entertainment)

and multi-location card that was issued by a third party independent of

the merchant. He took to the road and signed up merchants across the

country to save others from his fate.

McNamara’s success led to a host of imitators. Alfred

Bloomingdale of Bloomingdale’s department store fame introduced

Dine and Sign in California. Duncan Hines created the Signet Club.

Gourmet and Esquire magazines began credit card programs for their

readers. But all of McNamara’s early imitators failed. Bankers,

however, saw an opportunity. Savvy as they are about giving out

money for profit, bankers were more successful in offering their own

versions of national cards. Success came to Bank of America and

Master Charge, who came to dominate the credit card business in the

1960s. In the late 1970s Bank Americard became VISA and Master

Charge became MasterCard. In 1958, American Express introduced

its card. Their success the first year was so great—more than 500,000

people signed up—that American Express turned to computer giant

IBM for help. Advanced technology was the only way for companies

to manage the vast numbers of merchants and consumers who linked

themselves via their credit cards, and in the process created a

mountain of debt. Technology made managing the credit card

business profitable.

To make their system work, credit card companies needed to get

as many merchants to accept their cards and as many consumers to use

them as they possibly could. They were aided by the sustained