Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CONSUMERISMENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

589

Gelston, Steven W. A Guide to Documents of the Consumer Move-

ment: A National Catalog of Source Material. Mount Vernon,

New York, Consumers’ Union Foundation, 1980.

Silber, Norman Isaac. Test and Protest: The Influence of Consumers

Union. New York, Holmes and Meier, 1983.

Warne, Colston E. The Consumer Movement: Lectures. Manhattan,

Kansas, Family Economics Trust Press, 1993.

Consumerism

Consumerism is central to any study of the twentieth century. In

its simplest form, it characterizes the process of purchasing goods

such as food, clothing, shelter, electricity, gas, water, or anything else,

and then consuming or using those goods. The meaning of consumer-

ism, however, goes well beyond that definition, and has undergone a

striking shift from the way it was first used in the 1930s to describe a

new consumer movement founded in opposition to the increased

prevalence of advertising. It is with much irony that by the end of the

twentieth century, consumerism came to mean a cultural ethos

marked by a dependence on commerce and incessant shopping and

buying. This shift in meaning reflects the shift in how commercial

values transformed American culture over the century.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, social life became

increasingly commercialized. According to the famous Middletown

studies, automobiles conferred mobility on millions, and amusement

parks, movie theaters, and department stores had become serious

competitors to leisure pursuits that traditionally had been provided by

church, home, and family centered activities. By 1924, commercial

values had significantly changed home and leisure life as compared to

1890; even school curriculums were being altered in order to accom-

modate an increasingly commercialized world.

As a response to these changes, a consumer movement emerged,

and in the 1920s was focused on sanitary food production and

workers’ conditions. But by the 1930s, the rapid commercialization

taking place shifted the consumer movement’s attention to advertis-

ing. This reform movement was predicated on the idea that the

modern consumer often has insufficient information to choose effec-

tively among competing products, and that in this new era of

increased commercialization, advertisements should provide poten-

tial consumers with more information about the various products.

They also objected to advertising which was misleading, such as the

image-based advertising which often played on people’s fears and

insecurities (such as suggesting that bad breath or old-fashioned

furnishings prevented professional and social success).

Accordingly, the consumer movement sought policies and laws

which regulated methods and standards of manufacturers, sellers, and

advertisers. Although the preexisting 1906 Food and Drug Act had

made the misbranding of food and drugs illegal, the law only applied

to labeling and not to general advertising. With the support of a New

York senator and assistant Secretary of Agriculture Rexford G.

Tugwell, a bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate in 1933 which

would prohibit ‘‘false advertising’’ of any food, drug, or cosmetic,

defining any advertisement false if it created a misleading impression

by ‘‘ambiguity or inference.’’ Ultimately, a significantly less strict

form of the bill was passed, called the Wheeler-Lea Amendment,

which is still the primary law governing advertising today.

In the 1930s, the consumer movement—which was first to use

the term consumerism—sought assurances about the quality of goods

sold to the public. For most people, shopping in the early part of the

century was still a novelty, and certainly wasn’t central to daily life.

This was due, in part, to the (relatively) modest amount of goods

available, and to the nature of the shopping environment, which was

typically an unembellished storefront. Often, the shopkeeper was an

acquaintance of the buyer, and frequently the act of buying was

dependent upon an active exchange of bargaining. This changed,

however, with the expansion of fixed-priced and display-laden de-

partment stores which flourished after World War II (though they had

been in existence since just after the Civil War).

The end of World War II marked a significant point in the

development of consumer culture in its second meaning, which

strongly contrasts with the perspective of the consumer movement. At

the end of World War II, the return of soldiers, a burgeoning

economy, and a boom in marriage rates and child-birth created a new

and unique set of circumstances for the American economy. Unprece-

dented prosperity in the 1950s led people to leave the cities and move

to the suburbs; the increased manufacturing capabilities meant a rapid

rise in the quantity and variety of available goods; and the rise and

popularity of television and television advertising profoundly altered

the significance of consumerism in daily life.

The heretofore unprecedented growth in inventions and gadgets

inspired an article which appeared in The New Yorker on May 15,

1948 claiming ‘‘Every day, there arrive new household devices,

cunningly contrived to do things you don’t particularly want done.’’

The author described Snap-a-cross curtains, the Mouli grater, and the

Tater-Baker as examples of the inventive mood of the era. Prepared

cake mixes were introduced in 1949; Minute Rice in 1950; and

Pampers disposable diapers in 1956. The variety of goods was

staggering: Panty Hose debuted in 1959, along with Barbie (the most

successful doll in history); and in 1960, beverages began to be stored

in aluminum cans. Due to their increased prevalence and an increase

in advertising, these items went from novelties to an everyday part of

American life. By the end of the century, many of these items were no

longer viewed as luxuries but as necessities.

During this time, the government responded by encouraging

behavior which favored economic growth. For example, the Ameri-

can government supported ads which addressed everything from

hygiene to the ‘‘proper’’ American meal and, ultimately, the media

campaign was a crucial element in the development of consumerism,

or what had become a consumer culture. In Mad Scientist, media critic

Mark Crispin Miller argues that American corporate advertising was

the most successful propaganda campaign of the twentieth century.

Because most of the consumption was geared towards the

household, many television advertisements were geared towards the

housewife, the primary consumer in American households. In addi-

tion to advertisements, other factors specifically attracted women to

shopping, such as the development of commodities which (supposed-

ly) reduced household chores, an activity for which women were

primarily responsible. Ironically (but quite intentionally), ‘‘new’’

products often created chores which were previously unknown, such

as replacing vacuum bag filters or using baking soda to ‘‘keep

the refrigerator smelling fresh.’’ In 1963, Betty Friedan published

The Feminine Mystique which derided suburbia as ‘‘a bedroom

and kitchen sexual ghetto,’’ a critique partially based on what

many experienced as the cultural entrapment of women into the

role of homemaker, an identity that was endlessly repeated in

advertising images.

The mass migration to the suburbs also resulted in the construc-

tion of new places to shop. The absence of traditional downtown areas

CONSUMERISM ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

590

along with the popularity of automobiles gave rise to the suburban

shopping mall, where typically, one or two large department stores

anchor a variety of other stores, all under one roof. The by-now

prevalent television advertising was another significant factor con-

tributing to the spread of shopping malls, by further creating demand

for material goods. Unlike older downtown centers, the new mall was

a physical environment devoted solely to the act of shopping.

The abundance of goods and ease with which to buy them led to

a change in the American attitude towards shopping. Visits to

shopping locations became more frequent, and were no longer viewed

as entirely a chore. Although it remained ‘‘work’’ for some, shopping

also became a form of entertainment and a leisure-time activity.

Like the world’s fairs before them, suburban shopping malls

displayed the wonders of modern manufacturing and reflected a

transition from store as merchant to store as showroom. In what was

now a crowded marketplace, imagery became increasingly critical as

a way of facilitating acts of consumption. According to Margaret

Crawford in her essay ‘‘The World in a Shopping Mall’’: ‘‘The

spread of malls around the world has accustomed large numbers of

people to behavior patterns that inextricably link shopping with

diversion and pleasure.’’ Although this phenomenon originated out-

side the United States and predated the twentieth century, American

developers—with their ‘‘bigger is better’’ attitude—perfected shop-

ping as a recreational event.

As a result, malls eventually became a central fixture of Ameri-

can social life, especially in the 1980s. Increasingly bigger malls were

built to accommodate the rapid proliferation of chain stores and in

order to provide the ‘‘consummate’’ shopping experience (and,

conveniently, to eliminate the need to leave the mall), additional

attractions and services were added. By the 1980s, food courts, movie

theaters, and entertainment venues enticed shoppers. These centers

became such popular gathering places that they functioned as a

substitute for other community centers such as parks or the YMCA.

Teenagers embraced malls as a place to ‘‘hang-out’’ and in response,

many shops catered specifically to them, which aided advertising in

cultivating consumer habits at an early age. Some chain stores, such

as Barnes and Noble, offer lectures and book readings for the public.

Some shopping malls offered other community activities, such as

permitting their walkways to be used by walkers or joggers before

business hours. The largest mall in the United States was the gigantic

Mall of America, located in Bloomington, Minnesota, which covered

4.2 million square feet (390,000 square meters) or 78 acres. (The

largest mall in North America is actually a million square feet

larger—the West Edmonton Mall, located in Canada).

Increasingly, many elements of American social life were

intermixed with commercial activity, creating what has become

known as a consumer culture. Its growth was engineered in part by

‘‘Madison Avenue,’’ the New York City street where many advertis-

ing agencies are headquartered. As advertising critics note, early

advertising at beginning of the century was information based, and

described the value and appeal of the product through text. Advertis-

ers quickly learned, however, that images were infinitely more

powerful than words, and they soon altered their methods to fit. The

image-based approach works by linking the product with a desirable

image, often through directly juxtaposing an image with the product

(women and cars, clean floors and beautiful homes, slim physiques

and brand-names). Although such efforts to promote ‘‘image identi-

ty’’ were already sophisticated in the 1920s and 1930s, the prolifera-

tion of television significantly elevated its influence.

The marriage of image advertising and television allowed adver-

tising to achieve some of its greatest influences. First, ads of the 1950s

and early 1960s were successful in cultivating the ideal of the

American housewife as shopper. Advertisements depicted well-

scrubbed, shiny nuclear families who were usually pictured adjacent

to a ‘‘new’’ appliance in an industrialized home. Second, advertising

promoted the idea of obsolescence, which means that styles eventual-

ly fall out of fashion, requiring anyone who wishes to be stylish to

discard the old version and make additional purchases. Planned

obsolescence was essential to the success of the automotive and

fashion industries, two of the heaviest advertisers.

A third accomplishment of image-based advertising was creat-

ing the belief, both unconscious and conscious, that non-tangible

values, such as popularity and attractiveness, could be acquired by

consumption. This produced an environment in which commodification

and materialism was normalized, meaning that people view their

natural role in the environment as related to the act of consumption.

Accordingly, consumerism or ‘‘excess materialism,’’ (another defini-

tion of the term) proliferated.

Advertising, and therefore television, was essential to the growth

of consumerism, and paved the way for the rampant commercialism

of the 1980s and 1990s. Concurrently, there was a tremendous

increase in the number of American shopping malls: to around 28,500

by the mid-1980s. The explosion of such commercialism was most

evident in the sheer variety of goods created for purely entertainment

purposes, such as Cabbage Patch Kids, VCR tapes, Rubik’s cubes,

and pet rocks. So much ‘‘stuff’’ was available from so many different

stores that new stores were even introduced which sold products to

contain all of the stuff. By the mid-1980s, several 24-hour shopping

channels were available on cable television and, according to some

sources, more than three-fourths of the population visited a mall at

least once a month, evidence of the extent to which shopping was part

of daily life.

It is important to note that with the development of consumer

culture, consumerism in its earlier sense was still being practiced.

Ralph Nader (1934—) is credited with much of the movement’s

momentum in the late 1960s. In 1965, Nader, a Harvard lawyer,

published a book about auto-safety called Unsafe at Any Speed: The

Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile. This and the

revelation that General Motors Corporation had been spying on him

and otherwise harassing him led to passage of the National Traffic and

Motor Vehicle Safety Act in 1966. Nader went on to author other

books on consumer issues, and established several nonprofit research

agencies, including Public Citizen, Inc. and the Center for Study of

Responsive Law. Other organizations also arose to protect consumer

interests such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Food and

Drug Administration (FDA), and the Better Business Bureau (BBB).

The Consumers Union, which was founded in 1936, continues to be

the most well-known consumer organization because of its monthly

magazine Consumer Reports, which evaluates competing products

and services.

Aside from the efforts of such consumerist groups, the forces of

consumer culture were unstoppable. By the late 1980s and 1990s, the

proliferation of commercial space reached every imaginable venue,

from the exponential creation of shopping malls and ‘‘outlet stores’’;

to the availability of shopping in every location (QVC; Internet; mid-

flight shopping); to the use of practically all public space for advertis-

ing, (including airborne banners, subway walls, labels adhered to

fruit, and restroom doors). This omnipresent visual environment

CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSICENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

591

reinforced what was by now an indoctrinated part of American

life: consumerism.

The ubiquitousness of consumer culture was so prevalent that a

number of artists throughout the century made it their subject matter.

Andy Warhol, along with Roy Lichtenstein and others, won world-

wide celebrity with endlessly repeated portraits of commodities

(Coke bottles, Campbell’s soup cans) and of celebrities, which

seemed to be wrapped and packaged along with all of the other

products. Holidays were created based on buying gifts (Secretary’s

Day, Halloween), and malls and stores which are sometimes viewed

as community space replaced other venues which used to be popular

public spaces (bowling alleys, YMCAs, community centers, town halls).

Consumerism became so critical to Americans that millions of

people went significantly into debt to acquire goods. Credit, which

permits the purchase of goods and services with little or no cash, was

essential for average people to be able to buy more and more. Credit

cards functioned like cash and, in 1990, the credit card debt of

Americans reached a staggering $243 billion. By 1997, that number

more than doubled, reaching $560 billion, according to the Bureau of

the Census. This dramatic increase in credit card spending was

undertaken, in part, because of the seemingly constant need to acquire

newer or better goods. Oprah Winfrey even held segments on her talk

show about how people were dealing with debt, and how to cut up

your credit cards.

The relentless consumption over the century has had the inevita-

ble result of producing tons—actually millions of tons—of consumer

waste. According to a report produced by Franklin Associates, Ltd.

for the Environmental Protection Agency, approximately 88 million

tons of municipal solid waste was generated in 1960. By 1995, the

figure had almost tripled, to approximately 208 million tons. This

means each person generated an average of 4.3 pounds of solid waste

per day. For example, Americans throw away 570 diapers per

second—or 49 million diapers a year. This astonishing level of waste

production has had the effect of rendering the United States a world

leader in the generation of waste and pollutants. In 1998, it was

projected that annual generation of municipal solid waste will in-

crease to 222 million tons by the year 2000 and 253 million tons in

2010. A full one-third of all garbage discarded by Americans is

packaging—an awesome amount of mostly non-decomposable mate-

rial for the planet to reckon with.

Further, as a variety of social critics such as Sut Jhally have

pointed out, consumerism is popular because advertisements sell

more than products: they sell human hopes and dreams, such as the

need for love, the desire to be attractive, etc. It is inevitable that the

hopes and dreams can never be reached through the acquisition of a

product, which, in turn, has lead to a profound sense of disillusion-

ment and alienation, a problem noted by public thinkers throughout

the century, from John Kenneth Galbraith to Noam Chomsky.

Sports Utility Vehicles promise security through domination,

Oil of Olay promises beauty in aging, and DeBeers promises eternal

love with diamonds. Since these empty solutions run counter to the

inevitability of the human condition, no product can ever meet its

promise. But in the meantime, people keep on consuming....

—Julie Scelfo

F

URTHER READING:

Barber, Benjamin. Jihad vs. McWorld: How Globalism and Tribalism

are Reshaping the World. New York, Ballantine Books, 1995.

Bentley, Amy. Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of

Domesticity. Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Brobeck, Stephen, editor. Encyclopedia of the Consumer Movement.

Santa Barbara, California, ABC-CLIO, 1997.

Cox, Reavis. Consumers’ Credit and Wealth: A Study in Consumer

Credit. Washington, National Foundation for Consumer Cred-

it, 1965.

Crawford, Margaret. ‘‘The World in a Shopping Mall.’’ In Variations

on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public

Space, edited by Michael Sorkin. New York, Noonday Press, 1992.

Ewen, Stuart. All Consuming Images: The Politics of Style in Contem-

porary Culture. New York, Basic Books, 1988.

Fox, Richard Wightman, and T. J. Jackson Lears, editors. The Culture

of Consumption: Critical Essays in American History, 1880-1990.

New York, Pantheon, 1983.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London,

Methuen, 1979.

Jhally, Sut. Codes of Advertising. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Kallen, Horace. The Decline and Rise of the Consumer. New York, D.

Appleton-Century Company, 1936.

Leach, William. The Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise

of a New American Culture. New York, Pantheon, 1993.

Lears, Jackson. Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertis-

ing in America. New York, Basic Books, 1994.

Lynd, Robert, and Helen Lynd. Middletown. New York, Harcourt

Brace, 1929.

Marchand, Roland. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way

for Modernity 1920-1940. Berkeley, University of California

Press, 1985.

Miller, Mark Crispin. Mad Scientist. Forthcoming.

Miller, Michael. The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the De-

partment Store, 1869-1920. Princeton, Princeton University Press,

1981.

Veblen, Thorstein. The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York,

Macmillan, 1899.

Consumers Union

See Consumer Reports

Contemporary Christian Music

In the late 1990s a genre of music, unknown to most of America,

began push its way onto the popular American music scene. Contem-

porary Christian Music or CCM traced its roots to Southern Gospel

and Gospel music, but only began to be noticed by a larger audience

when the music industry changed the way it tracked record sales in the

mid-1990s.

In the late 1960s, Capitol Records hassled a blond hippie named

Larry Norman for wanting to call his record We Need a Whole Lot

CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

592

More of Jesus and a Lot Less Rock and Roll. In response, Norman

decided to make and distribute his own records. Norman’s records

shocked the religious and irreligious alike. He mixed his strict

adherence to orthodox Christianity with honest cultural observations

in songs like ‘‘Why Don’t You Look into Jesus,’’ which included the

lines ‘‘Gonorrhea on Valentines Day, You’re still looking for the

perfect lay, you think rock and roll will set you free but honey you’ll

be dead before you’re 33.’’

Before long Norman’s dreams of artistic freedom had become a

nightmare when executives took over and created CCM the genre

which, unlike the artists who dreamed of singing songs about Jesus

for non-Christians, quickly focused on marketing the records to true

believers. CCM had become a large industry, signing and promoting

artists who were encouraged to make strictly religious records that

were heavy on theology but lacking in real world relevance. CCM

also began to cater to best-selling ‘‘secular’’ artists who experienced

Christian conversions, helping them to craft religious records which

both alienated longtime fans and couldn’t be distributed through

ordinary music channels. Among these were once popular performers

like Mark Farner of Grand Funk Railroad, Dan Peek of America, B.J.

Thomas, Richie Furay of Poco and Buffalo Springfield, Al Green,

Dion, Joe English of Wings, Rick Cua of the Outlaws, and many others.

By the 1980s, other studios became receptive to Christian music,

and allowed artists more flexibility with song lyrics. In 1983 a heavy

metal band named Stryper comprised of born again Christians emerged

from the L.A. metal scene and signed a record deal with a ‘‘secular’’

label Enigma which had produced many of the early metal artists. In

1985 Amy Grant signed her own direct deal with A&M that got her a

top 40 single ‘‘Find A Way,’’ and led to two number one singles ‘‘The

Next Time I Fall,’’ in 1987 and ‘‘Baby, Baby,’’ in 1991. Leslie

Phillips dropped out of CCM in 1987, changed her name to Sam, and

signed with Virgin, a company with whom she recorded several

critically lauded albums. Michael W. Smith signed with Geffen in

1990 and produced a number six hit ‘‘Place In This World.’’

With the commercial success of Grant and others, many CCM

artists no longer wanted to be identified as such, preferring to be

known simply as artists. In their view, being identified by their

spiritual and religious beliefs limited the music industry’s willingness

to widely disseminate their music and alienated some consumers.

Many of these artists left their CCM labels and signed with ‘‘secular’’

record labels or arranged for their records to be distributed in both the

‘‘Christian’’ and ‘‘secular’’ music markets. By the mid-1990s artists

like dc Talk, Jars of Clay, Bob Carlisle, Kirk Franklin, Fleming and

John, Julie Miller, BeBe and CeCe Winans, punk band MxPx, Jon

Gibson, and others once mainstays of CCM, had signed with

‘‘secular’’ labels.

Christian artists’ attractiveness to ‘‘secular’’ record labels in-

creased with the introduction of a new mode of calculating record

sales. The introduction of SoundScan, a new tracking system, brought

attention to CCM in the mid-1990s. SoundScan replaced historically

unreliable telephone reports from record store employees with elec-

tronic point-of-purchase sales tracking. SoundScan also began to

tabulate sales in Christian bookstores. The result suddenly gave CCM

increased visibility in popular culture as many artists who had

heretofore been unknown outside the Christian community began to

find themselves with hit records.

Jars of Clay, a rookie band which formed at college in Green-

ville, Illinois, was among the first of these success stories. Signed

with a tiny CCM label called Essential Records, their debut record

was selling briskly in the Christian world when one single, ‘‘Flood’’

came to the attention of radio programmers who liked it, and unaware

that it was a song from a ‘‘Christian’’ band, began to give it

significant airplay in several different formats. Before long ‘‘Flood’’

was a smash hit played in heavy rotation on VH-1 and numerous other

music video outlets. Mainstream label Zomba, which had recently

purchased Jars’ label, re-released the record into the mainstream

market and the Jars Boys—as they were affectionately known—

began to tour with artists like Sting, Jewel, and the Cowboy Junkies.

Their second release ‘‘Much Afraid,’’ benefitted from the SoundScan

arrangement by debuting at number eight on the Billboard Album chart.

Another band which benefitted from the increased attention that

the SoundScan arrangement brought to CCM was a band which

formed at Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University in the late 1980s and

consisted of three young men, one black and two white, who hailed

from the Washington D.C. area. dc Talk, as they were known, began

as a rap band but evolved over the years into a grunge-pop sound

which culminated in their 1995 release ‘‘Jesus Freak.’’ Soundscan

recorded the strong debut of ‘‘Jesus Freak’’ on the Billboard charts

and had many industry executives inquiring about dc Talk. Kaz

Utsunomiya, an executive at Virgin Records dispatched one of his

assistants to Tower Records to fetch a copy of the album and liked

what he heard. Virgin soon signed dc Talk to a unique deal that made

them Virgin artists but allowed dc Talk’s CCM market label Forefront

to continue to distribute to the world of Bible bookstores. Virgin also

released a single ‘‘Just Between You And Me,’’ which cracked the

top 40 list. And dc Talk’s follow up album, Supernatural, showed the

band’s power, debuting at number four. Sandwiched between Mari-

lyn Manson and Kiss on the music charts, the debut was rife with

symbolism, for Manson was an unabashed Satanist and Kiss, had

been labeled—probably unfairly—as Satanists for years by Chris-

tians who were convinced that its initials stood for something sinister

like ‘‘Kings In Satan’s Service.’’

But the greatest triumph belonged to a most unlikely artist

named Bob Carlisle who would see his record Butterfly Kisses,

displace the Spice Girls at the top of the charts. Carlisle was unlikely

because he was a veteran of the CCM market who had recently been

dropped by the major CCM label Sparrow and picked up by the small

independent label Diadem. Carlisle had long played in CCM bands

beginning in the 1970s and in the early 1990s had gone solo. Trained

to write cheerful, upbeat numbers which the CCM world preferred,

Carlisle prepared songs for his record with Diadem, and strongly

considered not including ‘‘Butterfly Kisses,’’ a song he had written

with longtime writing partner Randy Thomas, because it was a

melancholy song that was personal to Carlisle and his daughter and

one which he wasn’t sure the religious marketplace would appreciate.

Carlisle’s wife’s opinion prevailed and he included it. When a radio

programmer’s daughter in Florida heard the track at church, she told

her father who played it on the radio and received an overwhelmingly

positive response. Soon word of the song reached Clive Calder, the

president of Zomba Music which had recently engineered the pur-

chase of Carlisle’s label, Diadem.

In a brilliant series of moves, Calder repackaged and re-released

Carlisle’s album, replacing Carlisle’s too sincere cover pose with an

artists rendering of a butterfly and changing the serious title of the

record Shades Of Grace to Butterfly Kisses. Fueled as well by a tear-

inspiring performance on Oprah Winfrey’s daytime talk show, a

feature in the Wall Street Journal and airplay on Rush Limbaugh’s

radio show, ‘‘Butterfly Kisses’’ headed for the top of the album charts

and became both a country and pop radio smash hit. Though success

CONVERTIBLEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

593

proved elusive for Carlisle—his next record quickly dropped off of

the charts—the larger point had been made that large audiences could

be interested in CCM if the music was packaged in ways that would

appeal to people who didn’t necessarily share the artists’ deep

Christian convictions.

Tens of other artists who considered themselves serious Chris-

tians wanted to avoid the restrictive CCM market. But just as they had

once been told to stay out of politics by their more conservative

brethren, Christians had long been told to stay out of rock music.

Christians feared the world associated with rock ’n’ roll and many

described it as a dirty place, but others couldn’t deny the impact that

rock music had on American culture. Some Christians wanted the

impact of rock ’n’ roll to carry their messages, and wanted to avoid the

stigma attached to religious music. Some of these artists included

King’s X, The Tories, Hanson, Gary Cherone of Extreme, and Van

Halen, Lenny Kravitz, Moby, Full On The Mouth, Judson Spence,

Collective Soul, and Burlap To Cashmere.

Even with so many crossover artists, some artists continued to

struggle with labels that kept their music from the general record

buying public. Artists like dc Talk and Jars of Clay asked to be treated

‘‘normally’’ and not as religious artists, but they continued to receive

Grammy awards in the ‘‘Gospel’’ category and record stores contin-

ued to stock their music in the ‘‘Inspirational’’ or ‘‘Christian’’ bins.

Nevertheless, by the end of the twentieth century, CCM had evolved

to the extent that Christian music could be found not only in the

traditional religious categories, but also throughout the many genres

of popular music.

—Mark Joseph

F

URTHER READING:

Baker, Paul. Why Should The Devil Have All The Good Music? Waco,

Word Books, 1979.

Fischer, John. What On Earth Are We Doing? Michigan, Servant

Publications, 1997.

Peacock, Charlie. At The Crossroads. Nashville, Broadman &

Holman, 1999.

Rabey, Steve. The Heart Of Rock And Roll. New Jersey, Revell, 1985.

Turner, Steve. Hungry For Heaven. Illinois, Intervarsity Press, 1996.

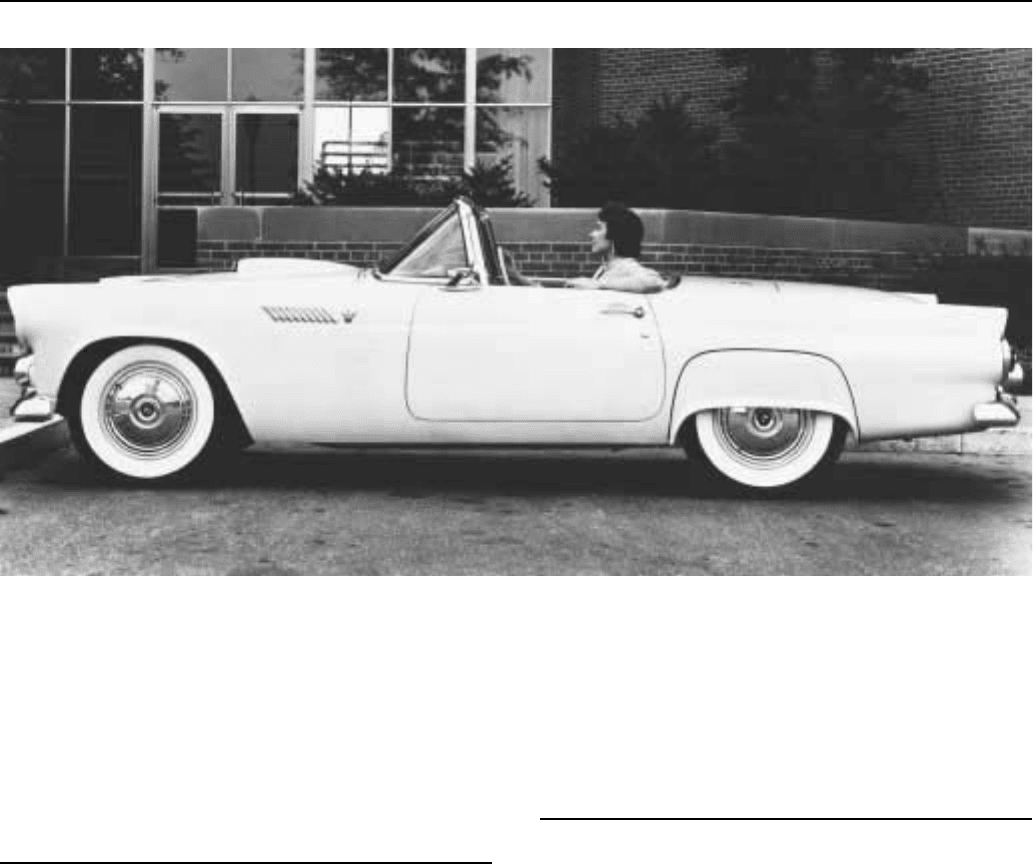

Convertible

Glamorous automobiles with enormous emotional appeal—

conjuring up romantic images of youthful couples speeding across

wide-open spaces, sun shining on their tanned faces, wind rushing

through their hair as rock music blasts from the radio—convertibles

have survived to the end of the century as a symbol of the good life

in America.

The term ‘‘convertible’’ refers to a standard automobile body-

style designation adopted by the Society of Automotive Engineers in

1928. Short for ‘‘convertible coupe,’’ a convertible typically de-

scribes a two-door car with four seats, a folding fabric roof (hence the

convertible synonym ‘‘ragtop’’) that is permanently attached to the

frame and may be lifted and lowered at the driver’s discretion, a fixed-

position windshield, and roll-up side windows. In the early days,

when automobiles were still built in backyards and small blacksmith

shops, they resembled the familiar horse-drawn carriages of the day.

Open body vehicles, some came with optional folding tops similar to

those on wagons. By the teen years, manufacturers had begun to

design automobiles that no longer resembled carriages and to offer

various body styles to the driving public. By the late 1920s, practicali-

ty pushed closed cars to the forefront, and, ever since, convertibles

have been manufactured in smaller numbers than closed cars.

The first true convertibles, an improvement on the earlier

roadsters and touring sedans, appeared in 1927 from eight manufac-

turers. During the 1930s, the convertible acquired its image as a

sporty, limited-market auto, surviving the Depression because of its

sales appeal—it was the best, most luxurious, and most costly of a

manufacturer’s lineup, a sign that better days were ahead. 1957-67

was the golden age of convertibles, with the sixties the best years:

convertibles held 6 percent of the market share from 1962-66. By the

1970s, however, market share had dropped to less than 1 percent.

Their decline came about because of their relative impracticality

(deteriorating fabric tops, lack of luggage space and headroom, and

poor fuel economy because of heavier curb weight); the introduction

of air-conditioning as an option on most automobiles, which made

closed cars quieter and more comfortable; the introduction of the

more convenient sunroofs and moonroofs; decline in wide-open

spaces; availability of cheaper, reliable imports; the impact of the

Vietnam War on a generation of car buyers; and changes in safety

standards—due to the efforts of Ralph Nader and insurance compa-

nies alarmed by the enormous power of many cars during the 1960s,

Washington mandated higher standards of automotive safety and

required manufacturers to include lap and shoulder belts, collapsible

steering columns, side impact reinforcement, chassis reinforcement,

energy-absorbing front ends, and five mph crash bumpers; the threat

to pass Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 216 (roof crush

standard) caused manufacturers to lose their enthusiasm for convertibles.

Furthermore, the adage in the automotive industry, ‘‘When the

market goes down, the top goes up,’’ may have been proven true again

as the recession of the 1970s drove a stake through the convertible’s

heart during that decade. In fact, according to Lesley Hazelton in

‘‘Return of the Convertible,’’ no mass-market convertibles were

available from the early seventies through the early eighties, though a

driver could purchase a convertible ‘‘for a price: the Rolls-Royce

Corniche; the Alfa Romeo Spider; the Mercedes-Benz 450SL, 380SL,

or 560SL.’’

In 1982, Lee Iacocca, chairman of Chrysler, brought back the

convertible after a six-year absence. Buick introduced a new convert-

ible that year, and Chevrolet, Ford, Pontiac, and Cadillac soon

followed. With only seven American convertibles and a handful of

European and Japanese convertibles being manufactured in the mid-

1990s, some question whether the convertible will remain after the

turn of the century. Others believe that convertibles will remain an

automotive option so long as there are romantic drivers who wish to

feel the wind in their hair.

—Carol A. Senf

F

URTHER READING:

Gunnell, John ‘‘Gunner.’’ Convertibles: The Complete Story. Blue

Ridge Summit, Penn., Tab Books, 1984.

Hazleton, Lesley. ‘‘Return of the Convertible.’’ The Connoisseuer.

Vol. 22, May 1991, 82-87.

CONWAY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

594

A 1950s Ford T-Bird Convertible.

Langworth, Richard M., and the auto editors of Consumer Guide. The

Great American Convertible. New York, Beekman House, 1988.

Newbery, J. G. Classic Convertibles. New York, Brompton

Books, 1994.

Wright, Nicky. Classic Convertibles. New York, Metro Books, 1997.

Conway, Tim (1933—)

As the perennial comedy sidekick, Tim Conway was a television

comedy mainstay for four decades. He debuted as a repertory player

on Steve Allen’s 1950s variety show, and co-starred as the nebbishy

Ensign Parker on the popular McHale’s Navy situation comedy

during the 1960s. He then became a reliable second banana on The

Carol Burnett Show, which ran from 1967 until 1978, where he was

often paired with the lanky Harvey Korman. Conway’s characters

included the laconic boss to Burnett’s dimwitted secretary, Mrs.

Wiggins. He was also a regular performer in children’s movies for

Walt Disney during the 1970s. In the late 1980s, Conway created his

best-known comedy persona by standing on his knees and becoming

Dorf, a klutzy sportsman. As Dorf, Conway produced and starred in

several popular TV specials and videos. Conway starred in a succes-

sion of short-lived TV series in his attempts to be a leading man; he

good-naturedly acquired a vanity license plate reading ‘‘13 WKS,’’

the usual duration of his starring vehicles.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Allen, Steve. More Funny People. New York, Stein and Day,

1982.

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946-Present. 6th ed. New

York, Ballantine, 1995.

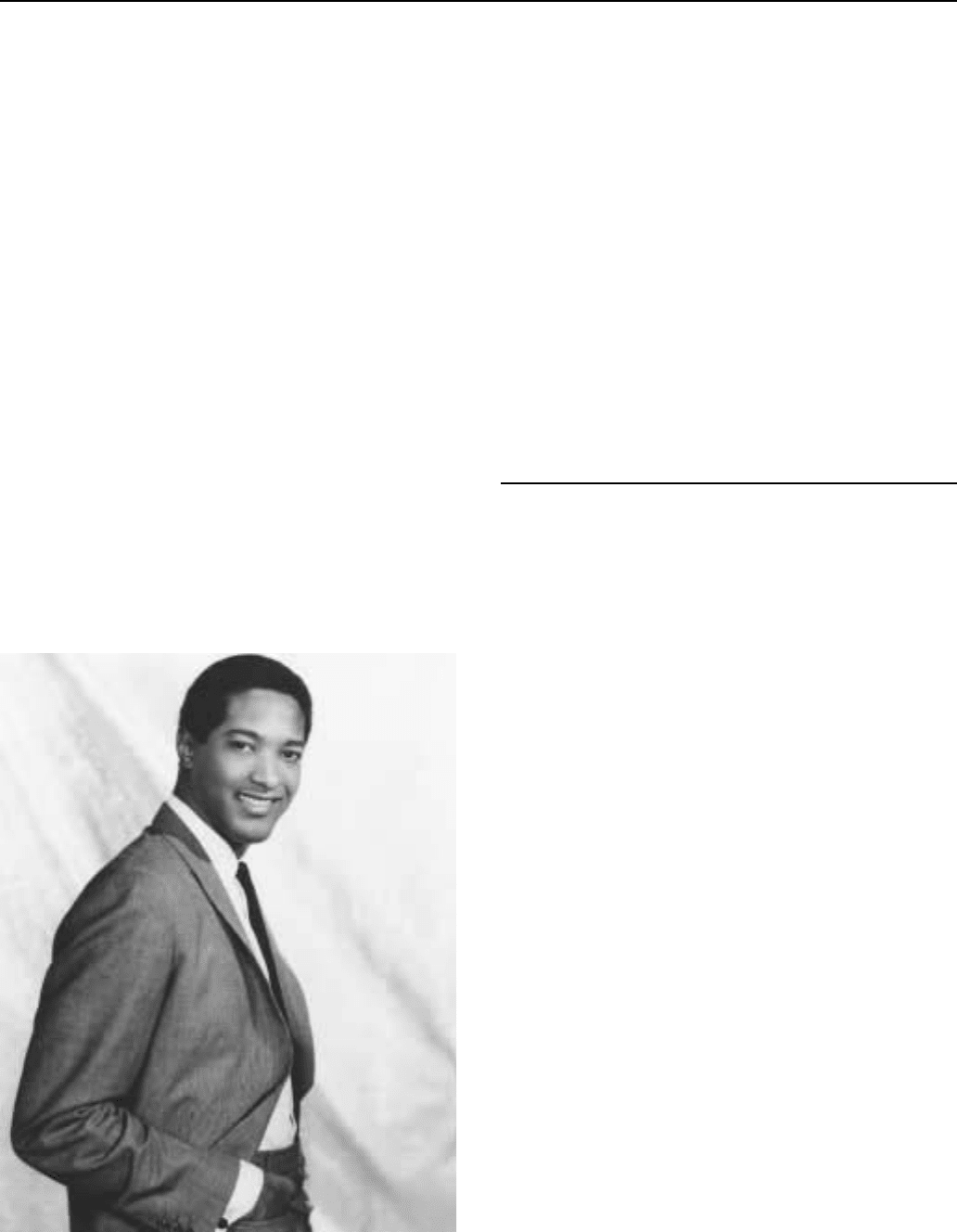

Cooke, Sam (1935-1964)

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Soul music star Sam

Cooke laid the blueprint for many of the Soul and R&B artists who

followed him. One of the first major Gospel stars to cross over into

secular music, Cooke was also among the first Soul or R&B artists to

found his own music publishing company. During a time when many

black artists lost financial and artistic control of their music to greedy

independent and major record labels, Cooke started his own record

company, leading the way for other artists such as Curtis Mayfield to

do the same. But it was Cooke’s vocal delivery, which mixed a sweet

smoothness and the passion of Gospel music, that proved the greatest

influence on a number of major Soul stars, most significantly Curtis

Mayfield, Bobby Womack, Al Green, and Marvin Gaye. Because

Sam Cooke was one of Gaye’s musical idols, the man born Marvin

Pentz Gay, Jr. went so far as to add an ‘‘e’’ to the end of his name

when he began singing professionally, just as Sam Cooke did.

Sam Cooke was born into a family of eight sons in Clarkesdale,

Mississippi, and began singing at an early age in church, where his

father was a Baptist minister. He and his family later moved to

Chicago, Illinois, where Cooke began singing in a Gospel trio called

the Soul Children, which consisted of Cooke and two of his brothers.

As a teenager, Cooke joined the Highway QCs, and by the time he was

in his early twenties, Cooke became a member of one of the most

important longstanding Gospel groups, the Soul Stirrers. While he

COOPERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

595

was with the Soul Stirrers, Cooke recorded a number of Gospel

classics for Specialty Records, such as the Cooke-penned ‘‘Touch the

Hem of His Garment,’’ ‘‘Just Another Day,’’ and ‘‘Nearer to Thee.’’

In a controversial move, Cooke crossed over into the secular

market with the single ‘‘Lovable’’ while he was still singing with the

Soul Stirrers. So contentious was this move that the single was

released under the pseudonym ‘‘Dale Cook.’’ More importantly,

Specialty Records owner Art Rupe distanced the label from Cooke by

releasing him from his contract for fear of losing Specialty’s Gospel

fan base. Cooke’s breakthrough Pop hit was 1957’s ‘‘You Send Me,’’

essentially a rewrite of a well-known Gospel tune of the time, but with

lyrics about the love of another person rather than God. With its

Gospel influenced vocal delivery, ‘‘You Send Me’’ provided the

foundation for Soul music for forty years to come—a foundation that

never strayed very far away from Gospel, no matter how profane the

subject matter became.

‘‘You Send Me’’ went to number one on the Billboard charts,

beginning a string of thirty-one Pop hits for Cooke from 1957 to 1965

that included ‘‘I’ll Come Running Back To You,’’ ‘‘Chain Gang,’’

‘‘You Were Made for Me,’’ ‘‘Shake,’’ and ‘‘Wonderful World.’’

While some of his Pop material was frivolous (‘‘Everybody Likes to

Cha Cha Cha,’’ ‘‘Twistin’ the Night Away,’’ and ‘‘Another Saturday

Night’’), Cooke’s ardent support of the 1960s Civil Rights struggle

was evident during interviews at the time. His music also reflected his

commitment to the struggle in songs such as ‘‘A Change is Gonna

Come,’’ a response to Bob Dylan’s ‘‘Blowin’ in the Wind.’’ Then, at

the height of his career, Sam Cooke was killed on December 11,

Sam Cooke

1964—shot three times in the Los Angeles Hacienda Motel by a

manager who claimed to be acting in self-defense after she asserted

Cooke raped a 22-year-old woman and then turned on her. Although

the shooting was ruled justifiable homicide, there were a number of

details about that night that remained hazy and unanswered, and there

has never been a sufficient investigation of his death. For years after

his death Cooke has remained a significant presence within Soul

music, and in 1986 he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

—Kembrew McLeod

F

URTHER READING:

McEwen, Joe. Sam Cooke: A Biography in Words and Pictures. New

York, Sire Books, 1977.

Wolff, Daniel. You Send Me: The Life and Times of Sam Cooke.

London, Virgin, 1996.

Cooper, Alice (1948—)

Rock stars come and go, but Alice Cooper’s contributions to the

canon of rock ’n’ roll showmanship have been remarkably lasting. In

a career spanning three decades, Cooper has elevated the live presen-

tation of rock music with bizarre theatrics, taboo subjects, and an

uncompromising hard-rock sound.

Alice Cooper was born Vincent Furnier in Detroit, Michigan, on

February 4, 1948, the son of Ether (an ordained minister) and Ella

Furnier. The family moved quite frequently. Living in Phoenix,

Arizona, Vincent was a high-school jock who was on the track team,

and reported for the school newspaper. During his time in school, he

met Glen Buxton, a tough kid with an unsavory reputation as a

juvenile delinquent who was a photographer for the newspaper.

Buxton played guitar; the young Furnier wrote poetry. It wasn’t too

long after school that the duo moved to Los Angeles in search of rock

’n’ roll dreams.

While in L.A., Furnier and Buxton enlisted Michael Bruce, Neal

Smith, and Dennis Dunnway and began calling themselves the

Earwigs. In 1968, the band changed their name to Alice Cooper,

noting that it sounded like a country and western singer’s stage name.

(Another legend about the name’s origin included a drunken session

with an Ouija Board in tow.) In 1974, Furnier legally changed his

name to Alice Cooper. Iconoclastic musician Frank Zappa went to

one of the group’s Los Angeles club shows. Impressed with their

ability to clear a room, Zappa offered the band a recording contract

with his label Straight, a subsidiary of Warner Bros. The band

recorded two records for Straight, Pretties For You and Easy Action,

before signing with Warner Bros. in 1970.

The band’s first album for Warner Bros., 1971’s Love It To

Death, featured the underground FM radio hit, ‘‘I’m Eighteen,’’ a

paean to youth apathy that predated the nihilistic misanthropy of the

punk scene by five years. Later that year, the band recorded Killer,

which featured some of their most celebrated songs such as ‘‘Under

My Wheels,’’ ‘‘Be My Lover,’’ and ‘‘Dead Babies.’’

The tour in support of Killer elevated the band’s reputation in the

rock world. Cooper—with his eyes circled in dark black make-up—

pulled theatrical stunts such as wielding a sword with an impaled baby

COOPER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

596

Alice Cooper

doll on the end or singing with his pet boa constrictor coiled around

him. For the grand finale, Alice was sentenced to ‘‘die’’ by hanging

on a gallows set up on stage. The crowds adored him, the critics took

note of the band’s energy, and soon Alice Cooper and his band were

poised to bid farewell to underground obscurity.

The band followed Killer with their breakthrough album, 1972’s

School’s Out. The title song was an anti-authority rant that became a

hit single. The subsequent tour that followed was no less controver-

sial, for the singer was placed in an onstage guillotine (operated by

master illusionist James Randi) and decapitated. Later Cooper re-

turned in top hat and tails singing ‘‘Elected.’’ With each year, the

presentations became increasingly absurd—with Alice fighting off

oversized dancing teeth with an enormous toothbrush during the tour

supporting their 1973 album, Billion Dollar Babies—and both fans

and critics thought the music was beginning to suffer.

The final album by the original Alice Cooper band, 1974’s

Muscle Of Love, was a financial and artistic failure. The band split up,

and Alice pursued a solo career. His 1975 album, Welcome to My

Nightmare, spawned a hit single (the controversial ballad ‘‘Only

Women Bleed’’), a theatrically-released film of the same name, and

widespread mainstream fame. Cooper became one of the first rockers

to perform at Lake Tahoe, play Pro-Am golf tourneys, and appear in

films and mainstream shows like Hollywood Squares and The To-

night Show with Johnny Carson.

Cooper’s post-band work was informed by then-current trends in

music and his personal life. He went public with his battle with

alcoholism, an experience chronicled on his 1978 album, From the

Inside. He used synthesizers and rhythm machines on such new-wave

tinged records as Flush the Fashion (1980) and DaDa (1983), and

enlisted the services of the late Waitresses singer Patty Donahue for

his 1982 Zipper Catches Skin album. None of these records catapulted

his name back up the charts, and Warner Bros. chose not to pick up an

option on his contract.

Cooper returned to the rock marketplace in 1986 with a new

album Constrictor, on a new label, MCA. He was aping the

overproduced metal scene, and the record was a flop. Critics blasted

Cooper for staying in the rock game well past his shelf life. But it

wasn’t until 1990, when Cooper signed with Epic Records, and made

several rock hard albums, Trash (1989) and Hey Stoopid (1991), that

exposed the singer to a new generation of metalheads. In May 1994,

COOPERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

597

Cooper released The Last Temptation, a concept album based on the

characters created by respected graphic novelist Neil Gaiman.

Alice Cooper’s career is marked by dizzying highs of grandeur

and influence, and miserable lows of bargain-bin indifference. The

shock-rockers of the 1990s such as Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch

Nails are merely driving down the same roads that were originally

paved by Alice Cooper’s wild imagination.

—Emily Pettigrew

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Alice Cooper Presents.’’ http://www.alicecoopershow.com.

March 1999.

Cooper, Alice, with Steven Gaines. Me, Alice: The Autobiography of

Alice Cooper. New York, Putnam, 1976.

Henssler, Barry. ‘‘Alice Cooper.’’ Contemporary Musicians. Vol. 8.

Detroit, Gale Research, 1992.

Koen, D. ‘‘Alice Cooper: Healthy, Wealthy and Dry.’’ Rolling Stone.

July 13-27, 1989, 49.

‘‘Mr. America.’’ Newsweek. May 28, 1973, 65.

‘‘Schlock Rock’s Godzilla.’’ Time. May 28, 1978, 80-83.

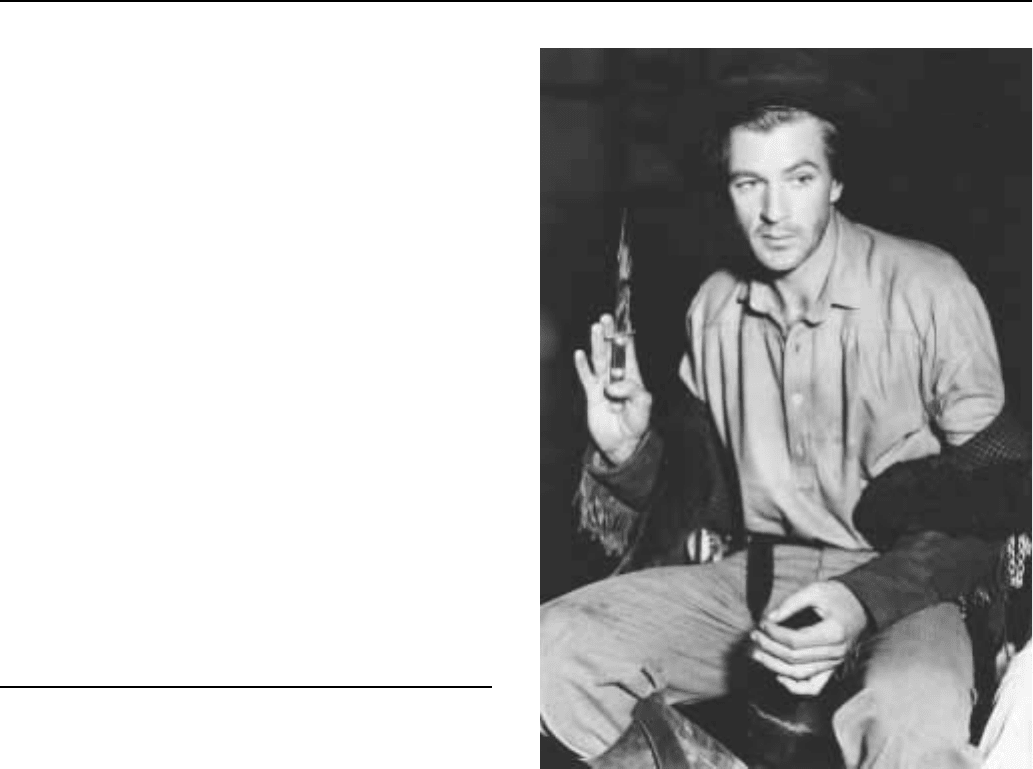

Cooper, Gary (1901-1961)

In American cinema history, Gary Cooper reigned almost un-

challenged as the embodiment of male beauty—‘‘swooningly beauti-

ful’’ as Robin Cross defined it in his essay in The Movie Stars Story—

and an enduring emblem of innocent ideals and heroic virtues. Lanky

and laconic, his screen persona often shy and hesitant, there was about

him the aura of a solitary man, his clear compelling eyes seemingly

focused on a distant and private horizon. Cooper contributed compre-

hensively to every genre of Hollywood film, working with an

unparalleled range of directors and leading ladies. His career spanned

35 years, shorter than that of several of his contemporaries, yet he

made an astonishing number of films by any standard—92 in all—

which carried him through as a leading man from the silent era to the

commencement of the 1960s.

Irrespective of the material, Cooper’s casual, laconic delivery

remained unmodified by any change of pace or nuance, yet his very

simplicity lent truth to his performances. In the public mind, Cooper

remains an archetypal Man of the West, most movingly defined by his

Sheriff Will Kane in High Noon (1952). What he never played,

however, was a man of villainy or deceit.

Christened Frank Cooper, he was born on May 7, 1901 to British

immigrant parents in Helena, Montana, where his father was a justice

of the Supreme Court. He was educated in England from 1910-17,

returning to attend agricultural college in Montana, work on a ranch,

and study at Grinnell College in Iowa. There, he began drawing

political cartoons. He was determined to become an illustrator and

eventually went to Los Angeles in 1924 to pursue this goal. Unable to

find a job, he fell into work as a film extra and occasional bit player,

mainly in silent Westerns, and made some 30 appearances before

Gary Cooper

being picked up by director Henry King as a last-minute substitute for

the second lead in The Winning of Barbara Worth (1926).

The camera loved Cooper as it did Garbo, and his instant screen

charisma attracted attention and a long tenure at Paramount, who built

him into a star. He made a brief appearance in It (1927) with Clara

Bow and became the superstar’s leading man in Children of Divorce

the same year, a film whose box-office was helped considerably by

their famous off-screen affair. It was the first of many such liaisons

between Cooper and his leading ladies who, almost without excep-

tion, found his virile magnetism and legendary sexual prowess

irresistible. He finally settled into marriage with socialite Veronica

Balfe, a relationship that survived a much-publicized affair with

Patricia Neal, Cooper’s co-star in the screen version of Ayn Rand’s

The Fountainhead (1949). These exploits did nothing to dent his

image as a gentle ‘‘Mr. Nice Guy’’ replete with quiet manly strength

or his growing popularity with men and women alike, and by the mid-

1930s his star status was fully established and remained largely

unshakable for the rest of his life.

Cooper made his all-talkie debut in The Virginian (1929), the

first of his many Westerns, uttering the immortal line, ‘‘When you

call me that, smile!’’ In 1930, for Von Sternberg, he was the Foreign

Legionnaire in Morocco with Dietrich and emerged a fully estab-

lished star. He was reunited with her in Frank Borzage’s Desire in

COOPERSTOWN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

598

1936, by which time he had successfully entered the arenas of

romantic comedy and melodrama, played the soldier hero of A

Farewell to Arms (1932), and survived a few near-misses to embark

on his best period of work.

From 1936-57 Cooper featured on the Exhibitors’ Top Ten List

in every year but three, and ranked first in 1953. His run of hits in the

1930s, which began with The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935),

brought one of his most famous roles in 1936, that of Longfellow

Deeds, the simple country boy who inherits a fortune and wishes to

give it away to the Depression-hit farmers of America. The film, Mr.

Deeds Goes to Town, directed by Frank Capra, earned Cooper the first

of his five Oscar nominations, while another country boy-turned-

patriotic hero, Howard Hawks’ Sergeant York (1941) marked his first

Oscar win.

The 1940s brought two films with Barbara Stanwyck, the

quintessentially Capra-esque drama, Meet John Doe (1941), then

Hawks’ comedy Ball of Fire (1942), in which he was a memorable

absent-minded professor. His sober portrayal of baseball hero Lou

Gehrig in The Pride of the Yankees (1942) won another Academy

nomination, as did For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943) with Ingrid

Bergman. The 1950s brought mixed fortunes. In 1957 Billy Wilder

cast the 56 year-old Cooper opposite 28 year-old gamin Audrey

Hepburn in the sophisticated comedy romance Love in the Afternoon.

Cooper, suffering from hernias and a duodenal ulcer, precursors of the

cancer that would kill him, looked drawn and older than his years, and

the May-December partnership was ill received.

The decade did, however, cast him in some notable Westerns. He

was a striking foil to Burt Lancaster’s wild man in Vera Cruz (1954)

and was impressive as a reformed outlaw forced into eliminating his

former partners in Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958), his last

masterpiece in which the ravages of age and illness were now

unmistakably apparent. But it was his awesomely contained, deter-

mined, and troubled sheriff, going out to face the forces of evil alone

in High Noon that won him another Oscar and cemented the Cooper

image for future generations.

At the 1960 Academy Awards ceremony in April 1961, Gary

Cooper was the recipient of a special award for his many memorable

performances and the distinction that he had conferred on the motion

picture industry. He was too ill to attend and his close friend James

Stewart accepted on his behalf. A month later, on May 13, 1961, Gary

Cooper died, leaving one last film—the British-made and sadly

undistinguished The Naked Edge (1961)—to be released posthu-

mously. Idolized by the public, he was loved and respected by his

peers who, as historian David Thomson has written, ‘‘marveled at the

astonishingly uncluttered submission of himself to the camera.’’

—Robyn Karney

F

URTHER READING:

Cross, Robin. ‘‘Gary Cooper.’’ The Movie Stars Story. New York,

Crescent Books, 1986.

Meyers, Jeff. Gary Cooper: American Hero. New York, Morrow, 1998.

Shipman, David. The Great Movie Stars: The Golden Years. London,

Angus & Robertson, 1979.

Thomson, David. A Biographical Dictionary of Film. New York,

Knopf, 1994.

Cooperstown, New York

Home to the National Baseball Museum and Hall of Fame,

Cooperstown, a restored nineteenth-century frontier town and coun-

try village of about 2,300 inhabitants at the close of the twentieth

century, is visited annually by up to 400,000 tourists. Baseball has

been described as America’s national pastime, and it is fair to say that

Cooperstown, in central New York State, draws to its village thou-

sands of American tourists in search of their country’s national identity.

When the National Baseball Hall of Fame opened in 1939,

Americans from coast to coast read about it and heard radio broad-

casts of the opening induction ceremonies. Cy Young, Babe Ruth, Ty

Cobb, Grover Alexander, and Walter Johnson were among those

inducted as the hall’s first members. Every year on the day after the

annual inductions, a Major League game is played at nearby Doubleday

Field, seating approximately ten thousand, on the spot where many

believe baseball to have originated. A legend of the origin of baseball

claims that the game was developed in Cooperstown in 1839. Accord-

ing to a three-year investigation of the Mills Commission in the early

1900s, Abner Doubleday and his young friends played a game of

‘‘Town Ball’’ with a hand-stitched ball and a four-inch flat bat.

Doubleday is said to have introduced bases, created the positions of

pitcher and catcher, and established the rules that defined the game of

baseball. Though this legend is disputed by some, even those who

disagree accept the village as a symbolic home for the game’s creation.

Philanthropist and Cooperstown native Stephen C. Clark found-

ed the Baseball Hall of Fame. Clark inherited his fortune from his

grandfather, Edward Clark, who earned his wealth as a partner to

Isaac Merrit Singer, inventor of the Singer sewing machine. Through

the generosity of the Clark family toward their birthplace, Cooperstown

gained not only the baseball museum, but also a variety of other

attractions. In the nineteenth century, when Cooperstown was becom-

ing a summer retreat, Edward Clark built Kingfisher Tower, a sixty-

foot-high tower that overlooks the natural beauty of Otsego Lake,

which spans nine miles north from its shore at Cooperstown. Stephen

Clark and his brother, Edward S. Clark, built the Bassett Hospital to

honor Dr. Mary Imogene Bassett, a general practitioner of Cooperstown

and one of the first female physicians in America. Stephen Clark also

brought the New York State Historical Association to Cooperstown in

1939; the village has since been the annual summer site of the

association’s seminars on American culture and folk art. In 1942,

Stephen Clark established the Farmer’s Museum, a cultural attraction

that displays the customs of pre-industrial America. The museum

continued to grow with the 1995 addition of an American Indian

Wing containing more than six hundred artifacts that reflect the

cultural diversity and creativity of Native Americans.

The exhibits of Native American culture are well suited to

Cooperstown since it was a traditional fishing area of the

Susquehannock and the Iroquois Indians until Dutch fur traders

occupied it in the seventeenth century. It was also the birthplace of

James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), the early nineteenth-century

writer whose novels romantically depict Native Americans and the

frontier life of early America. The Pioneers (1823), the first of

Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, is a novel set in the blossoming

village of Cooperstown, and one of its main characters is based on

James Fenimore Cooper’s father, Judge William Cooper, the founder