Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

COMMUNISMENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

569

over the societal effects of the growth of ‘‘sex, drugs, and rock ’n’

roll. Commune members were predominantly young, white, middle-

class males; and the communes tended to be smaller, unstructured,

anarchistic, and more democratically governed than their predeces-

sors. Most twentieth-century communes were not political in nature

even though they were generally sympathetic to the left and political-

ly oriented groups such as Students for a Democratic Society and the

militant poor.

Famous twentieth-century communes ranged in location from

the Farm in Tennessee to Drop City in Colorado and ranged in

ideology from the secular Morning Star Ranch to the religious Hare

Krishna communal farm. There were also a number of short-lived

communal arrangements at the many rock festivals of the period,

including the famous Hog Farm at Woodstock. Communes required a

strong commitment to the group and a willingness to sacrifice some

individual freedom for the group’s welfare. Twentieth-century com-

munes proved to be very fragile, and most existed for only a year or

two before internal disputes attributed to male chauvinism, lack of

direction, and weak structure broke them apart. The communal

movement has continued in relative obscurity since the 1960s and

1970s, and will thus continue to be associated with that time period

and the countercultural movement.

Communes have had both positive and negative images in

United States society and in popular culture. On the positive side, the

nation has always professed to value the new and different, and in the

late twentieth century has placed increasing emphasis on the tolera-

tion of dissent and diversity exemplified by the multicultural move-

ment. The twentieth-century mass media favored communes as they

sought the new and eccentric, good drama, and escapist entertain-

ment. The popular media thus focused on the colorful and controver-

sial aspects of the communal movement including its association with

widespread drug use, free love, wild clothing and hair styles, and rock

’n’ roll music. Communes have also met with the strong negative

attitudes of many members of mainstream society who favor the

status quo and disagree with the communalists’ values or lifestyles.

These people comprise the so-called ‘‘Establishment’’ from which

the hippies wished to break away. Communal members have been

harassed with zoning suits, refused admittance to businesses, spat at,

threatened with violence, and attacked. The communal movement

also experienced a backlash in the late twentieth century as many

people lamented the disrespect and defiance of youth to their elders.

The reactionary right wing of American politics used hippies and

communalists as conveniently visible scapegoats for all the evils of

modern American society. There are also communal links to certain

late twentieth-century cults that have generated extremely negative

publicity. These included Jim Jones’s followers, who committed

mass suicide at Jonestown in the 1970s; Charles Manson’s murderous

followers of the 1960s; the Branch Davidians led by David Koresh,

who battled the FBI at Waco in the 1990s; and the Heaven’s Gate cult,

whose mass suicide also received widespread coverage in the 1990s.

Negative associations portray commune members as social deviants

who threaten established society.

While communes face the problems of decreasing population

and visibility in the late twentieth-century United States, they have

not disappeared from the American scene. Communes remain preva-

lent in the smaller cities and college towns where a hip subculture

flourishes. The value system of the hippie communes that slowly

faded away in the late 1970s has had a large impact on twentieth-

century society. Their legacy is evident in such American cultural

phenomena as an increasing awareness of environmental issues, an

emphasis on the importance of health and nutrition, a rise in New Age

spiritualism, and a rise in socially conscious businesses such as Ben

and Jerry’s Ice Cream.

—Marcella Bush Treviño

F

URTHER READING:

Hedgepeth, William. The Alternative: Communal Life in New Ameri-

ca. New York, Macmillan, 1970.

Melville, Keith. Communes in the Counter Culture: Origins, Theo-

ries, Styles of Life. New York, Morrow, 1972.

Miller, Timothy. The Hippies and American Values. Knoxville,

University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

Robert, Ron E. The New Communes: Coming Together in America.

Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall, 1971.

Veysey, Laurence. The Communal Experience: Anarchist and Mysti-

cal Counter-Culture in America. New York, Harper and Row, 1973.

Zablocki, Benjamin. Alienation and Charisma: A Study of Contempo-

rary American Communes. New York, Free Press, 1980.

Zicklin, Gilbert. Countercultural Communes: A Sociological Per-

spective. Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press, 1983.

Communism

Originally outlined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in The

Communist Manifesto (1848), Communism is a social and political

system in which all property is owned communally and all wealth

distributed among citizens according to need. Although it was a

product of large-scale industrialization in the nineteenth century,

Communism has had a profound influence on the global politics and

economics of the twentieth century. In the United States, Commu-

nism became popular among American industrial workers during the

Depression, and played a more public role in politics during the

1930s. In the 1940s and during the Cold War, the treatment of

Communist groups and individuals within the United States some-

times raised questions about the fairness not only of the American

justice system, but of the Constitution itself.

Communism is most often associated with the revolution which

took place in Russia in November 1917, and the establishment of the

federalist Soviet Union (USSR) in 1922. Its first leader was Vladimir

Ilich Lenin, whose version of Marxism, known as Marxism-Leninism,

became the dominant political and economic theory for communist

groups the world over. Under Joseph Stalin after World War II, the

USSR succeeded in gaining military and political control over much

of Eastern Europe, placing it in direct opposition to the capitalist

economies of the United States and Western Europe. When Stalin

died in 1953, many of his more brutal policies were renounced by the

new regime; but Communism had become a byword for threats to

personal freedom and for imperialist aggression. A climate of distrust

between the USSR and Western governments, backed by the threat of

global nuclear war, prevailed until the late 1980s.

The history of Communism in the United States begins long

before the Cold War, however. Left-wing activists and socialist

parties had been at work from before the beginning of the century, but

communist parties first appeared in the United States in 1919, partly

in response to the political developments in Russia. Communism has

COMMUNITY MEDIA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

570

unsettled American governments from the beginning, and after a

series of raids sanctioned by the Attorney General in 1919, left-wing

organizations were forced to become more secretive. It was another

ten years before the parties merged to form the Communist Party of

the United States of America (CPUSA). The CPUSA’s goal of

regaining support from union members was certainly helped by the

onset of the Depression, and Communism was popular among those

who suffered most, such as African American workers and Eastern

European immigrants.

Despite dire warnings from the political right, and although large

crowds turned out for rallies against unemployment, communists

remained a small faction within the trade union movement, and thus

were isolated in politics. Only in the 1930s, bravely fielding a black

vice-presidential candidate in 1932, opposing fascism in Europe, and

openly supporting Roosevelt in some of his New Deal policies, did

the CPUSA gain credibility with significant numbers of American

voters. Besides industrial workers and the unemployed, communist or

socialist principles also proved attractive to America’s intelligentsia.

Writers such as Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, and John Dos

Passos all declared themselves as Communist Party voters in 1932,

while the radical playwrights Clifford Odets and Lillian Hellman

were among many left-wing intellectuals to emerge from 1920s

literary New York to work in Hollywood.

In 1940, the Smith Act made membership in revolutionary

parties and organizations whose aim was to overthrow the U.S.

government illegal, and in 1950, under the McCarran Act, commu-

nists had to register with the U.S. Department of Justice. In the same

period, Senator Joseph McCarthy began Senate investigations into

communists in government, and the House Un-American Activities

Committee (HUAC) challenged the political views of individuals in

other areas. Many prominent people in government, the arts, and

science were denounced to HUAC as dangerous revolutionaries.

Because of the moral tone of the investigations and the presentation of

Communism as ‘‘Un-American,’’ many promising careers ended

through mere association with individuals called to explain them-

selves to the committee. One widely held myth was that the CPUSA

was spying for the Soviet government, a fear that, among other things,

resulted in the execution of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg in 1953. In

most cases there was no evidence for McCarthy’s accusations of ‘‘un-

American activity,’’ and his own career was to end abruptly when he

was censured by the Senate in 1954.

Perhaps because of the USSR’s imperialist ambitions after

World War II, Communism has frequently been presented to the

American people since then as a moral threat to ‘‘American’’ values

such as individualism and enterprise. U.S. involvement in wars in

Korea (1950-53) and Vietnam (1964-72), and military and political

actions elsewhere, such as South America and Cuba, have been

justified as attempts to prevent the spread of Communism, with anti-

war protesters often being branded as ‘‘Reds.’’ The Cold War

continued until the late 1980s, when Ronald Reagan, who had

previously referred to the Soviet Union as the ‘‘Evil Empire,’’ began

talks with Mikhail Gorbachev over arms reduction and greater

political cooperation. In the late 1990s, following the collapse of the

USSR in 1991, few communist regimes remained in place, and

although Communism remains popular in Eastern Europe, commu-

nists in the West form a tiny minority of voters. Their continuing

optimism is fuelled by Lenin’s claim that true Communism will only

become possible after the collapse of a global form of Capitalism.

—Chris Routledge

F

URTHER READING:

Fried, Richard M. Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspec-

tive. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990.

Klehr, Harvey. The Heyday of American Communism: The Depres-

sion Decade. New York, Basic Books, 1984.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. 1848.

New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Ottanelli, Fraser M. The Communist Party of the United States from

the Depression to World War II. New Brunswick, Rutgers Univer-

sity Press, 1991.

Shindler, Colin. Hollywood in Crisis: Cinema and American Society,

1929-1939. New York, Routledge, 1996.

Community Media

Between 1906 and 1922 radio amateurs—who referred to them-

selves as ‘‘distance fiends’’—ruled the airwaves. In their enthusiasm

to share common concerns, forge friendships with distant strangers,

and explore the expressive potential of the new medium, the radio

enthusiasts championed democratic communication through elec-

tronic media. By the mid-1920s, however, commercial sponsorship of

radio programming and corporate control of the newly developed

broadcasting industry stifled the participatory potential of the ‘‘wire-

less.’’ At the end of the twentieth century, the rapid commercializa-

tion of the internet poses yet another threat to the democratic

possibilities of a new communication medium. Although the dis-

tance fiends are largely forgotten, their passionate embrace of the

communitarian potential of electronic communication lives on through

the work of community media organizations around the world.

Community media play a significant, but largely unacknowl-

edged, role in popular culture. Unlike their commercial and public

service counterparts, community media give ‘‘everyday people’’

access to the instruments of radio, television, and computer-mediated

communication. Through outreach, training, and production support

services, community media enhance the democratic potential of

electronic communication. Community media also encourage and

promote the expression of different social, political, and cultural

beliefs and practices. In this way, community media celebrate diversi-

ty amid the homogeneity of commercial media and the elitism of

public service broadcasting. Most important, perhaps, worldwide

interest in community media suggests an implicit, cross-cultural, and

timeless understanding of the profound relationship between commu-

nity cohesion, social integration, and the forms and practices of

communication. Despite their growing numbers, however, communi-

ty media organizations remain relatively unknown in most societies.

This obscurity is less a measure of community media’s cultural

significance, than an indication of its marginalized status in the

communications landscape.

In the United States, the origins of the community radio move-

ment can be traced to efforts of Lew Hill, founder of KPFA: the

flagship station of the Pacifica radio network. A journalist and

conscientious objector during World War II, Hill was disillusioned

with the state of American broadcasting. At the heart of Hill’s disdain

for commercial radio was an astute recognition of the economic

realities of radio broadcasting. Hill understood the pressures associat-

ed with commercial broadcasting and the constraints commercial

COMMUNITY MEDIAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

571

sponsorship places on a station’s resources, and, ultimately, its

programming. Hill and his colleagues reasoned that noncommercial,

listener supported radio could provide a level of insulation from

commercial interests that would ensure challenging, innovative, and

engaging radio. Overcoming a number of legal, technical, and eco-

nomic obstacles, KPFA-Berkeley signed on the air in 1949. At a time

of anti-Communist hysteria and other threats to the democratic ideal

of freedom of speech, KPFA and the Pacifica stations represented an

indispensable alternative to mainstream news, public affairs, and

cultural programming.

Although listener-supported radio went a long way toward

securing local enthusiasm and financial support for creative and

provocative programming, this model presented some problems.

During the early 1970s demands for popular participation in and

access to the Pacifica network created enormous rifts between local

community members, Pacifica staff, and station management. Con-

flicts over Pacifica’s direction and struggles over the network’s

resources continue to contribute to the divisiveness that remains

somewhat synonymous with Pacifica at the end of the twentieth

century. Still, KPFA and its sister stations consistently broadcast

programs dealing with issues considered taboo by commercial and

public service broadcasters alike.

Equally important, the Pacifica experience generated remark-

able enthusiasm for alternative radio across the country. For instance,

in 1962 one of Lew Hill’s protégés, Lorenzo Milam, founded KRAB,

a listener-supported community radio station in Seattle, Washington.

Throughout the 1960s, Milam traveled the country, providing techni-

cal and logistical support to a number of community radio outlets: a

loose consortium of community stations that came to be known as the

KRAB Nebula. By 1975, the National Alternative Radio Konference

(NARK) brought together artists, musicians, journalists, and political

activists with an interest in participatory, locally-oriented radio.

Within a few months the National Federation of Community Broad-

casters (NFCB) was established to represent the interests of the

nascent community radio movement. Committed to providing

‘‘nonprofessional’’ individuals and marginalized groups with access

to the airwaves, the NFCB played a pivotal role in the rise of

community radio in the United States. Still active, the NFCB contin-

ues to promote noncommercial, community-based radio. Organiza-

tions such as the World Association for Community Broadcasters

(AMARC) provide similar support services for the community radio

movement worldwide.

While Americans were exploring the possibilities of participa-

tory radio, Canadians turned their attention to television. In 1967, the

Canadian National Film Board undertook one of the earliest and best

known attempts to democratize television production. As part of the

experimental broadcast television series Challenge for Change, The

Fogo Island project brought the subjects of a television documentary

into a new, collaborative relationship with filmmakers. Embracing

and elaborating upon the tradition of the social documentary

championed by Robert Flaherty and John Grierson, Challenge for

Change undertook the ambitious and iconoclastic task of systemati-

cally involving the subjects of their films in the production process.

Senior producer Colin Low and his crew invited island residents to

contribute story ideas, screen and comment on rushes, and collaborate

on editorial decisions. By involving island residents throughout the

filmmaking process, producers sought to ‘‘open up’’ television

production to groups and individuals with no formal training in

program production. Initially conceived as a traditional, broadcast

documentary, the Fogo Island project evolved into the production of

28 short films that focused on discrete events, specific issues, and

particular members of the Fogo Island community. The Fogo Island

experience stands as a precursor to the community television move-

ment. Not only did the project influence a generation of independent

filmmakers and community television producers, the use of participa-

tory media practices to enhance community communication, to spur

and support local economic initiatives, and to promote a sense of

common purpose and identity has become the hallmark of community

media organizations around the world.

The dominance of commercial media in the United States made

democratizing television production in this country far more chal-

lenging. In response to criticisms that American television was a

‘‘vast wasteland’’ the US Congress passed the Public Broadcasting

Act of 1967 which sought to bring the high quality entertainment and

educational programming associated with public service broadcast-

ing in Canada and the United Kingdom to American audiences.

Throughout its troubled history—marked by incessant political pres-

sure and chronic funding problems—the Public Broadcasting Service

(PBS) has provided American television audiences with engaging,

informative, and provocative programming unlike anything found on

commercial television. However, rather than decentralize television

production and make television public in any substantive fashion,

PBS quickly evolved into a fourth national television network.

Although PBS remains an important outlet for independent film and

video producers, the level of local community access and participa-

tion in public television production is minimal at best.

Significantly, the early days of public television in the United

States provided the early community television movement with some

important precedents and helped set the stage for public access

television as we know it today. Throughout the mid-1960s, the

development of portable video equipment coupled with an urgent

need for programming prompted a unique, if sporadic, community-

based use of public television. Media historian Ralph Engelman

notes, ‘‘Early experimentation in the use of new equipment and in

outreach to citizens took place on the margins of public television in

the TV laboratories housed at WGBH-TV in Boston, KQED-TV in

San Francisco, and WNET-TV in New York.’’ These innovations,

most notably, WGBH’s Catch 44 gave local individuals and groups

an opportunity to reach a sizable, prime time, broadcast audience with

whatever message they desired. These unprecedented efforts were

short-lived, however, as public television quickly adopted program-

ming strategies and practices associated with the commercial networks.

Recognizing public television’s deficiencies, an assortment of

media activists turned their attention away from broadcasting to the

new technology of cable television. These media access advocates

hoped to leverage the democratizing potential of portable video

recording equipment with cable’s ‘‘channels of abundance’’ to make

television production available to the general public. In the late 1960s,

New York City was the site of intense, often contentious, efforts to

ensure local participation in cable television production and distribu-

tion. George Stoney—often described as the father of public access

television in the United States—was a leading spokesperson for

participatory, community oriented television in Manhattan.

Stoney began his career in the mid-1930s working in the rural

South as part of the New Deal. Through his training as a journalist and

educational filmmaker, Stoney understood the value of letting people

speak for themselves through the media. The use of media to address

local issues and concerns and to promote the exchange of perspectives

COMMUNITY MEDIA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

572

and ideas pervades Stoney’s work as filmmaker and access television

advocate. Following a successful term as executive producer for

Challenge for Change, Stoney returned to the United States in 1970

and, with the his colleague, Canadian documentary filmmaker Red

Burns, established the Alternative Media Center (AMC).

The AMC’s legacy rests on its successful adaptation of the

Challenge for Change model of participatory media production. Like

the Canadian project, the AMC gave people the equipment and the

skills to produce their own videotapes. Through the AMC, individual

citizens and local nonprofit groups became active participants in the

production of television programming by, for, and about their local

communities. In addition, the Center provided the technical resources

and logistical support for producing and distributing community

oriented programming on local, regional, and national levels. One of

the AMC’s primary strategies was to train facilitators who would then

fan out across the country and help organize community access

centers. Over the next five years, the Alternative Media Center played

a crucial role in shaping a new means of public communication:

community television. Organizations such as the U.S.-based Alliance

for Community Media and international groups like Open Channel,

were created to promote community television through local outreach

programs, regulatory reform measures, and media literacy efforts.

Like previous technological developments, computers and relat-

ed technologies have been hailed as a great democratizing force.

Much has been made of computer-mediated communication’s (CMC)

ability to enhance social interaction, bolster economic redevelop-

ment, and improve civic participation in local communities. Howev-

er, for those without access to computers—or the skills to make

efficient and productive use of these tools—the Information Age may

intensify social and political inequities. Community networking, like

community radio and television, provides disenfranchised individu-

als and groups with access to communication technologies.

Early experiments in community networking date back to the

mid-1970s. In Berkeley, California, the Community Memory project

was established specifically to promote community cohesion and

encourage community-wide dialogue on important issues of the day.

Project administrators installed and maintained terminals in public

spaces, such as libraries and laundromats, to encourage widespread

use of these new technologies. Somewhat akin to public telephones,

these computer terminals were coin operated. Although users could

read messages free of charge, if users wanted to post a message, they

were charged a nominal fee.

By the mid-1980s computer bulletin boards of this sort were

becoming more common place. In 1984, Tom Grundner of Case

Western University in Cleveland, Ohio created St. Silicon’s Hospital:

a bulletin board devoted to medical issues. Using the system, patients

could ask for and receive advice from doctors and other health

professionals. The bulletin board was an unprecedented success and

quickly evolved into a city-wide information resource. After securing

financial and technical support from AT&T, Grundner and his

associates provided public access terminals throughout the city of

Cleveland and dial up access for users with personal computers. The

first of its kind, the Cleveland Free-Net uses a city metaphor to

represent various types of information. For example, government

information is available at the Courthouse & Government Center,

cultural information is found in the Arts Building, and area economic

resources are located in the Business and Industrial Park section. In

addition to database access, the Cleveland Free-Net supports elec-

tronic mail and newsgroups. By the mid-1990s, most community

networks typically offered a variety of services including computer

training, free or inexpensive e-mail accounts, and internet access.

Through the work of the now-defunct National Public

Telecomputing Network (NPTN) Grundner’s Free-Net model has

been adopted by big cities and rural communities throughout the

world. In countries with a strong public service broadcasting tradition

like Australia and Canada, federal, state, and local governments have

played a significant role in promoting community networking initiatives.

In other instances, community networks develop through public-

private partnerships. For instance, the Blacksburg Electronic Village

(BEV) was established through the efforts of Virginia Tech, the city

of Blacksburg, Virginia, and Bell Atlantic. A number of organizations

such as the U.S.-based Association for Community Networking

(AFCN), Telecommunities Canada, the European Alliance for Com-

munity Networking (EACN), and the Australian Public Access

Network Association (APANA) promote community networking

initiatives on local, regional, and national levels.

Like other forms of community media, community networks

develop through strategic alliances between individuals, non-profit

groups, businesses, government, social service agencies, and educa-

tional institutions; it is the spirit of collaboration between these parties

that is central to efficacy of these systems. The relationships forged

through these community-wide efforts and the social interaction these

systems facilitate help create what community networking advocate

Steve Cisler refers to as ‘‘electronic greenbelts’’: localities and

regions whose economic, civic, social, and cultural environment is

enhanced by communication and information technologies (CIT).

Due in part to their adversarial relationship, mainstream media

tend to overshadow, and more often than not denigrate, the efforts of

community media initiatives. The majority of popular press accounts

depict community media organizations as repositories for depraved,

alienated, racist, or anarchist slackers with too much time on their

hands, and precious little on their minds. Writing in Time Out New

York, a weekly entertainment guide in New York City, one critic

likens community access television to Theater of the Absurd and

feigns praise for access’s ability to bring ‘‘Nose whistlers, dancing

monkeys and hairy biker-chefs—right in your own living room!’’

Likewise, entertainment programs routinely dismiss community tele-

vision out of hand. For example in their enormously popular Saturday

Night Live skit—and subsequent blockbuster feature films—Wayne’s

World’s Dana Carvey and Mike Meyers ridicule the crass con-

tent, technical inferiority, and self-indulgent style of community

access television.

Although few community media advocates would deny the

validity of such criticisms, the truly engaging, enlightening, and

provocative output of community media organizations goes largely

ignored. Yet, the sheer volume of community radio, television, and

computer-generated material attests to the efficacy of grassroots

efforts in promoting public access and participation in media produc-

tion and distribution. Furthermore, this considerable output highlights

the unwillingness, if not the inability, of commercial and public

service media to serve the distinct and diverse needs of local popula-

tions. Most important, however, the wealth of innovative, locally-

produced programming indicates that ‘‘non-professionals’’ can make

creative, substantive, and productive use of electronic media.

Community media serve and reflect the interests of local com-

munities in a number of unique and important ways. First, community

media play a vital role in sustaining and preserving indigenous

cultures. For instance, in Porcupine, South Dakota community radio

COMMUNITY THEATREENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

573

KILI produces programming for local Native Americans in the

Lakota language. Similarly, in the Australian outback, Aboriginal

peoples use community television to preserve their ancient cultural

traditions and maintain their linguistic autonomy. Second, communi-

ty media reflect the rich cultural diversity of local communities. For

example, some of the most interesting sites on Victoria Australia’s

community network (VICNET) are the pages celebrating Victoria’s

multicultural heritage (www.vicnet.net.au). These sites contain infor-

mation of interest to Victorian’s Irish, Polish, Hungarian, Vietnam-

ese, and Filipino populations. Likewise, Manhattan Neighborhood

Network (MNN) features a variety of programs that showcase Man-

hattan’s eclecticism. On any given day, audiences can tune in to a

serial titled Glennda and Friends about ‘‘two socially-conscious drag

queens,’’ unpublished poetry and fiction by an expatriate Russian

writer, a municipal affairs report, or Each One Teach One a program

dedicated to African-American culture. Finally, community media

play a decisive role in diversifying local cultures. Aside from cele-

brating the region’s rich musical heritage, WFHB, community radio

in Bloomington, Indiana, exposes local audiences to world music

with programs like Hora Latina (Latin music), The Old Changing

Way (Celtic music), and Scenes from the Northern Lights (music from

Finland, Norway, and Sweden). What’s more, WFHB brings local

radio from America’s heartland to the world via the internet

(www.wfhb.org). As corporate controlled media consolidate their

domination of the communication industries and public service

broadcasters succumb to mounting economic and political pressures,

the prospects for more democratic forms of communication diminish.

Community media give local populations a modest, but vitally

important, degree of social, cultural, and political autonomy in an

increasingly privatized, global communication environment.

—Kevin Howley

F

URTHER READING:

Barlow, William. ‘‘Community Radio in the U.S.: The Struggle for a

Democratic Medium.’’ Media, Culture and Society. Vol. 10,

1988, 81.

Cisler, Steve. Community Computer Networks: Building Electron-

ic Greenbelts. http://cpsr.org/dox/program/community-nets/

building

e

lectronic

g

reenbelts.html, November 11, 1998.

Engelman, Ralph. Public Radio and Television in America: A Politi-

cal History. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage, 1996.

Lewis, Peter. Media for People in Cities: A Study of Community

Media in the Urban Context. Paris, UNESCO, 1984.

Milam, Lorenzo. Sex and Broadcasting: A Handbook on Starting a

Radio Station for the Community. San Diego, MHO & MHO, 1988.

Schuler, Doug. New Community Networks: Wired for Change. New

York, ACM, 1996.

Community Theatre

Community theatre represents the majority of theatres in the

United States, including community playhouses and university and

college programs. Although the term ‘‘community theatre’’ has

disparate meanings the term can be applied generally to theatres—

whether professional or not—that draw from their communities. The

history of community theatre offers a unique perspective on the

struggles between artistic endeavors and commercial profit in theatri-

cal productions. While once a product of a movement to improve the

artistic quality of theatrical productions, by the end of the twentieth

century community theatre had become a venue more for communi-

ty participation in the arts than a fertile source of avant-garde

theatrical productions.

The roots of community theatre can be traced to the ‘‘Little

Theatre’’ movement that started in the 1910s. The movement came as

a reaction to the monopolistic ‘‘Syndicate’’ theatre system as well as

an attempt to join the growing discourse about non-commercial

theatre. According to Mary C. Henderson in her book, Theater in

America, ‘‘The ‘little-theater’ movement, launched so spectacularly

in Europe in the 1880s, finally reached America and stimulated

the formation of groups whose posture was anti-Broadway and

noisily experimental.’’

By 1895, touring companies became the primary source for

theatrical entertainment in the United States. Theatrical producers

Sam Nixon, Fred Zimmerman, Charles Frohman, Al Hayman, Marc

Klaw, and Abraham Erlanger saw the opportunity to gain control of

the American theatre and formed what came to be called ‘‘The

Syndicate.’’ The Syndicate purchased theatres across the country and

blacklisted ones that refused to cooperate with its business practices.

By 1900, the Syndicate monopolized the American theatre scene, and

between 1900 and 1915, theatre became a mainly conservative and

commercial venture. Due to public dissatisfaction, Frohman’s death,

and an anti-trust suit, the Syndicate system became largely ineffec-

tive by 1916.

During this period many of Europe’s finest independent theatres

began touring the United States; these included the Abbey Theatre

(1911), the Ballets Russes (1916), and Théâtre du Vieux Colombier

(1917-1919). Robert E. Gard and Gertrude S. Burley noted in

Community Theatre that ‘‘Their tour aroused the antagonism of

American citizens against the feeble productions of the commercial

theatre, and seemed to be the catalyst that caused countless dramatic

groups to germinate all over America, as a protest against commercial

drama.’’ In addition, the end of World War I led to a greater

awareness of the European theatrical practices of France’s Andre

Antoine, Switzerland’s Adolphe Appia, England’s Gordon Craig, and

Russia’s Vsevelod Meyerhold and Konstantine Stanislavsky.

The publication of Sheldon Cheney’s Theatre Arts Magazine

(1916) helped to broaden audiences for non-commercial theatre and

influenced its readers’ thoughts surrounding commercial theatre. In

1917 Louise Burleigh wrote The Community Theatre in Theory and

Practice in which she coined the phrase ‘‘Community Theatre’’ and

defined it as ‘‘any organization not primarily educational in its

purpose, which regularly produces drama on a noncommercial basis

and in which participation is open to the community at large.’’

Other publications such as Percy MacKaye’s The Playhouse and the

Play (1909) extolled the merits of ‘‘a theatre wholly divorced

from commercialism.’’

During this time several little theatres established themselves.

These included the Toy Theatre in Boston (1912); the Chicago Little

Theatre (1912); the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York (1915);

the Provincetown Players in Massachusetts (1915); the Detroit Arts

and Crafts Theatre (1916); and the Washington Square Players

(1918). By 1917 there were 50 little theatres, most of which had less

COMO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

574

than 100 seats and depended upon volunteers for labor and subscrib-

ers for financial support. By 1925 almost 2,000 community or little

theatres were registered with the Drama League of America. In her

essay ‘‘Theatre Arts Monthly’’ and the Construction of the Modern

American Theatre Audience, Dorothy Chansky observed that ‘‘The

common goals of all these projects were to get Americans to see

American theatre as art and not as mere frivolity.’’

Eventually, drama programs were introduced into colleges and

universities. In 1903 George Pierce Baker taught the first course for

playwrights at Radcliffe College and by 1925 he had established the

Yale School of Drama, which provided professional theatre training.

Graduates of Baker’s program included such noted theatre artists as

playwright Eugene O’Neill and designer Robert Edmund Jones. In

1914, Thomas Wood Stevens instituted the country’s first degree-

granting program in theatre at the Carnegie Institute of Technology.

And by 1940, theatre education was widely accepted at many univer-

sities in the United States.

Community theatre was also aided by government support. As

part of F. D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), The

Federal Theatre Project was established in 1935. Headed by Hallie

Flanagan Davis, the project employed 10,000 persons in 40 states.

During this time 1,000 productions were staged and more than half

were free to the public. Despite its mandate to provide ‘‘free, adult,

uncensored theatre,’’ the political tone of some productions eventual-

ly alienated members of Congress and funding was discontinued in

1939. In 1965, however, the federal government established the

National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and also facilitated states in

establishing individual arts councils. This, coupled with the inclusion

of theatres as non-profit institutions, helped many community thea-

tres remain operational. By 1990, the NEA’s budget was cut drastical-

ly, but community theatres continued to thrive at the end of the

twentieth century despite economic hardships.

Although the artistic ideals of the ‘‘Little Theatre’’ movement

have been assumed by larger, professional regional theaters, the drive

to produce theatre as a voluntary community activity remains solely

in the realm of the community theatre. Though most community

theatres no longer feature daring experimental works—offering in-

stead local productions of popular plays and musicals—community

theatres remain the most common source for community involvement

in the theatrical arts.

—Michael Najjar

F

URTHER READING:

Brockett, Oscar G. History of the Theatre. 7th ed. New York, Allyn

and Bacon, 1995.

Burleigh, Louise. The Community Theatre. Boston, Little Brown, 1917.

Chansky, Dorothy. ‘‘Theatre Arts Monthly and the Construction of

the Modern American Audience.’’ Journal of American Drama

and Theatre. Vol. 10, Winter 1998, 51-75.

Gard, Robert E., and Gertrude S. Burley. Community Theatre: Idea

and Achievement. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1975.

Henderson, Mary C. Theater in America: 250 Years of Plays, Players,

and Productions. New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Macgowan, Kenneth. Footlights Across America: Towards a Nation-

al Theater. New York, Harcourt, Brace, 1929.

MacKaye, Percy. The Playhouse and the Play: Essays. New York,

Mitchell Kennerley, 1909.

Young, John Wray. Community Theatre: A Manual for Success. New

York, Samuel French, 1971.

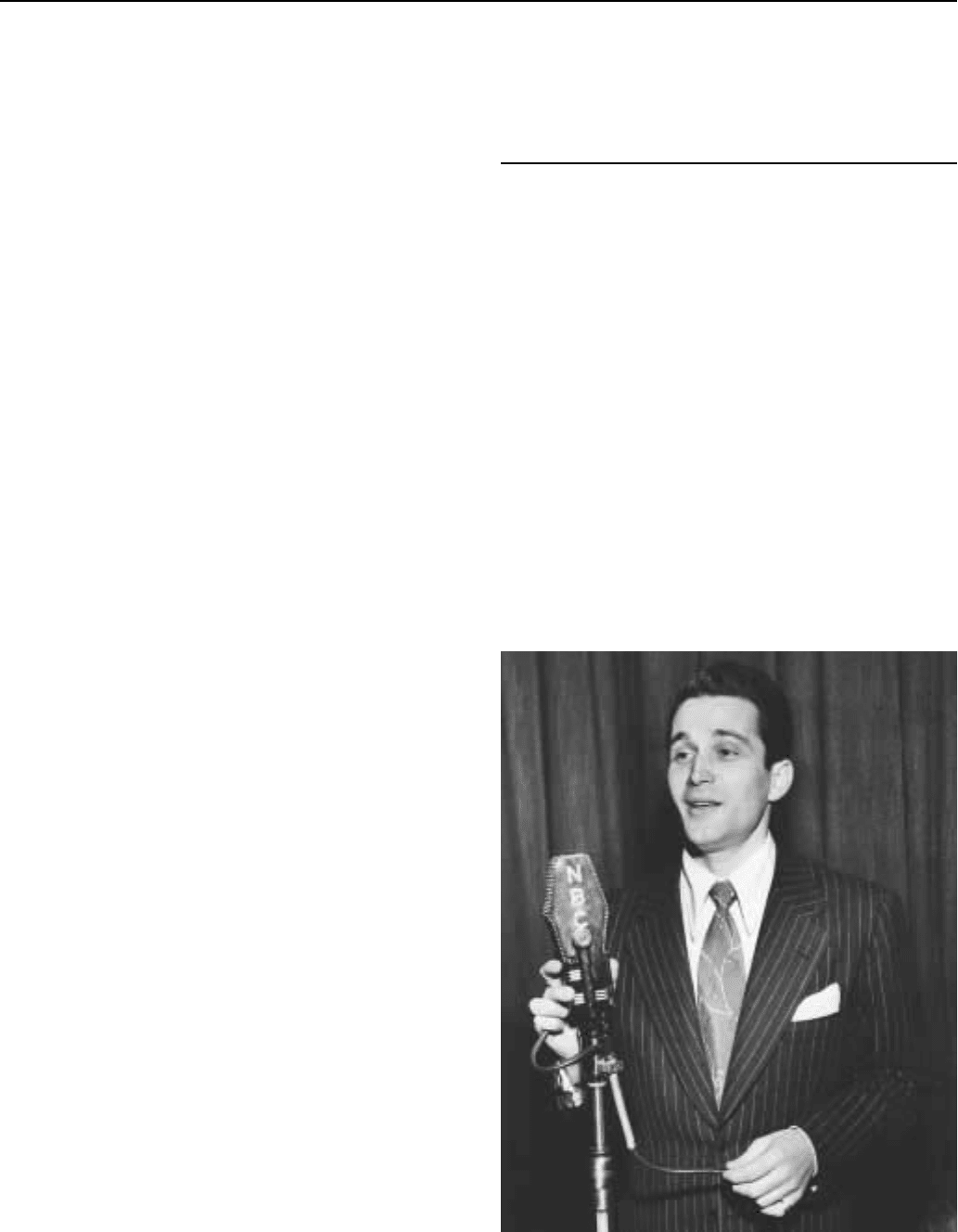

Como, Perry (1912—)

Crooner Perry Como rose to become one of the dominant

American male vocalists of the 1940s and 1950s, and retained a rare

degree of popularity over the decades that followed. He achieved his

particular fame for the uniquely relaxed quality of his delivery that

few have managed to emulate—indeed, so relaxed was he that his

detractors considered the effect of his smooth, creamy baritone

soporific rather than soothing, and a television comedian once paro-

died him as singing from his bed.

Born Pierino Como in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, the seventh of

13 children of Italian immigrants, Como began learning the barber

trade as a child, with the intention of buying his own shop as early as

his teens. Forced by his mill-worker father to finish high school, he

finally set up his own barber shop in 1929. In 1934 he auditioned as a

vocalist with a minor orchestra, and sang throughout the Midwest for

the next three years, before joining the Ted Weems Orchestra. The

orchestra thrived until Weems disbanded it in 1943 when he joined

the army, but by then Como had developed quite a following through

the years of touring and performing on radio, and his effortless

baritone was a popular feature of Ted Weems’s 78 rpm records.

CBSrecruited Como to radio, thus starting him on what proved to be

one of the most successful and long-running solo vocal careers of the

Perry Como

COMPACT DISCSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

575

century. He also became a highly popular nightclub performer, and

signed a recording contract with RCA Victor. Several of his singles

sold over two million copies, one over three million, and he had many

Top Ten and several number one hits over the years.

By late 1944 Perry Como had his own thrice-weekly radio show,

Supper Club, on CBS, which from 1948 on was renamed The Perry

Como Show and broadcast simultaneously on radio and television. He

became one of the most popular of TV stars, keeping that show until

1963, and then hosting The Kraft Music Hall every few weeks until

1967. One of his noteworthy contributions to music as a radio

showman was to invite Nat ‘‘King’’ Cole, R&B group The Ravens,

and other black entertainers to guest on his program when most shows

were still segregated, or featured blacks only in subservient roles.

In 1943 Como was signed to a motion picture contract by

Twentieth Century-Fox. He appeared in Something For The Boys

(1944), Doll Face (1945), If I’m Lucky (1946), and, at MGM, one of a

huge all-star musical line-up in the Rodgers and Hart biopic, Words

and Music (1948), but did not pursue a film career further, preferring

to remain entirely himself, singing and playing host to musical shows.

Como’s best-selling singles included ‘‘If I Loved You,’’ ‘‘Till the

End of Time,’’ ‘‘Don’t Let the Stars Get In Your Eyes,’’ ‘‘If,’’ ‘‘No

Other Love,’’ ‘‘Wanted,’’ ‘‘Papa Loves Mambo,’’ Hot Diggity,’’

‘‘Round and Round,’’ and ‘‘Catch a Falling Star’’—for which he won

a Grammy Award in 1958 for best male vocal performance. As well

as his numerous chart-topping successes, he earned many gold discs,

and recorded dozens of albums over the years, which continued to sell

very well when the market for his singles tailed off towards the end of

the 1950s. In 1968, however, he was approached to sing the theme

song from Here Come the Brides, a popular ABC program. The

resulting ‘‘Seattle’’ was only a minor hit, but it got Perry Como back

on the pop charts after a four-year absence, and his singles career

further revived in 1970 with ‘‘It’s Impossible,’’ which reached

number ten on the general charts and number one on the Adult

Contemporary charts.

After the 1960s, Como chose to ease himself away from televi-

sion to spend his later years in his Florida home. Nevertheless, he

continued to tour the United States twice a year well into the 1990s,

enjoying popularity with an older audience. In 1987 he was a

Kennedy Center honoree, and was among the inductees into the

Television Academy Hall of Fame a few years later. Few performers

have enjoyed such lasting success.

—David Lonergan

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network TV Shows. 5th Ed. New York, Ballantine Books, 1992.

Nite, Norm N. Rock On Almanac. 2nd Ed. New York, Harper

Collins, 1992.

Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. 6th Ed. New

York, Billboard Books, 1996.

Compact Discs

With the 1983 mass market introduction of CDs (compact discs),

the face of the music recording and retail industry changed dramati-

cally. As the price of compact disc players tumbled from $1,500 to

$500 and below, CDs were quickly adopted by music consumers and

pushed the long-playing vinyl record virtually off the market.

CDs offered extremely high sound quality, free from the scratch-

es or needle dust ‘‘noise’’ found on vinyl records. Compact discs

were the first introduction of digital technology to the general public.

Records and tapes had been recorded using analog technology.

Digital recording samples sounds and represents them as a series of

numbers encoded in binary form and stored on the disc’s data surface.

The CD player’s laser light reads this data and when it is converted

back into an electric signal, it is then amplified and played through

headphones or loudspeakers. On a CD nothing except light touches

the disc with no wear to the recording. In addition to the superior

sound of CDs, the new technology also allowed any song, or any part

of a song, to be accessed quickly. Most CD players could be

programmed to play specific songs, omit songs, or reorder them,

providing a ‘‘customization’’ previously unavailable with cassette

tapes or records.

While the portability of cassette tapes—with hand-held cassette

players like the Sony Walkman and the ubiquity of cassette players in

automobiles—slowed the domination of CDs in the market, manufac-

turers quickly produced products to offer the superior sound quality,

flexibility, and longevity of CDs in automobiles and for personal use.

By the end of the century, CD players that could hold several CDs at a

time were installed in automobiles and people could carry personal

CD players to listen to their favorite music with headphones while

exercising. Although manufacturers and record companies had for the

most part stopped manufacturing both cassette players and prerecorded

tapes, cassette tapes continued to be used in home recording and in

automobiles. By the late 1990s, cassettes were no longer a viable

format for prerecorded popular music in the United States although

they remained the most used format for sound recording worldwide.

The physical size of CDs altered the nature of liner notes and

album covers. The large size of LP covers had long offered a setting

for contemporary graphic design and artwork, but the smaller size of

the CD package, or ‘‘jewel box,’’ made CD ‘‘cover art’’ an oxymo-

ron. Liner notes and song lyrics became minuscule as producers tried

to fit their material into 5-by-5 inch booklets. The ‘‘boxed set,’’ a

collection of two or more CDs in a longer cardboard box, became

popular as retrospectives for musicians and groups, collecting all of a

musician or groups’ output including rare and unreleased material

with a booklet of extensive notes and photographs. Ironically, the

average playing time of a CD was more than 70 minutes but most

albums continued to hold about 40 minutes of music, the amount

available on LPs.

Though the long-playing records were technologically obsolete

and no longer stocked on the shelves of major music retailers, they

were still found in stores specializing in older recordings and used by

rap and hip-hop performers who scratched and mixed records to make

their music. LPs also experienced a minor resurgence in 1998 from

sales to young people interested in the ‘‘original’’ sound of vinyl.

Nevertheless, the CD had become the dominant medium for new

music by the end of the century.

—Jeff Ritter

F

URTHER READING:

Millard, Andre. America on Record: A History of Recorded Sound.

Cambridge University Press, 1995.

CONCEPT ALBUM ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

576

Concept Album

The concept album, initially defined as an LP (long-playing

record) recording wherein the songs were unified by a dramatic idea

instead of being disparate entities with no common theme, became a

form of expression in popular music in the mid-1960s, thanks to The

Beatles. Their 1967 release of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club

Band is generally recognized as the first concept album, although ex-

Beatle Paul McCartney has cited Freak Out!, an album released in

1966 by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, as a major

influence on the conceptual nature of Sergeant Pepper. During the

rest of the decade, the concept album remained the province of British

artists. The Rolling Stones made an attempt—half-hearted, according

to many critics—at aping the Beatles’ artistic achievement with Their

Satanic Majesties Request (1967). Other British rock bands, notably

The Kinks and The Who, were able to bring new insights into the

possible roles of the concept album in popular music, and it is at this

point that the hard and fast definition of the concept album came to be

slightly more subjective.

The Kinks, in a series of albums released in the late 1960s,

mythologized the perceived decline of British working class values.

The songs on these albums told the stories of representative characters

and gave the albums on which they appeared conceptual continuity. If

the lyrics were conceptually driven, the music was still straightfor-

ward rock ’n’ roll. The Who, however, experimented with the form of

the music as well as the lyrics, creating a conceptual structure unlike

anything that had come before in rock music. Songwriter Pete

Townshend was largely responsible for the band’s best known work,

Tommy (1969), also popularly known as the first ‘‘rock opera.’’ This

allegorical story of the title character, a ‘‘deaf, dumb and blind kid’’

who finds spiritual salvation in rock music and leads others towards

the same end, was communicated as much through the lyrics as by the

complex and classically-derived musical themes and motifs that

appeared throughout the album’s four sides.

Tommy was The Who’s most ambitious and successful concep-

tual effort, but it was not the last. Quadrophenia, recorded in 1973,

used the same style of recurring themes and motifs, but the characteri-

zation and storytelling in the lyrics was considerably more opaque

than its predecessor. Both these works were adapted into films, and

Tommy became a musical stage production in the early 1990s.

Largely due to Tommy’s popularity, the concept album became

synonymous with rock operas and rock and roll musical productions.

The recordings of late 1960s and early 1970s works such as Hair,

Godspell, and Jesus Christ Superstar are commonly referred to as

concept albums, further broadening the scope of their definition.

The burgeoning faction of popular music known as progressive

rock, which gained momentum in the late 1960s and early 1970s,

embraced the form of the concept album and used it as a means to

explore ever more high-flown and ambitious topics. Although the

classical portion of the album did not necessarily tie into the concept,

The Moody Blues nevertheless used the London Symphony Orches-

tra to aid in the recording of Days of Future Passed (1967), an album

consisting entirely of songs that dealt with the philosophical nature of

time. This work marked the concept album’s transition from simply

telling a story to actually being able to examine topics that were

heretofore considered too lofty to be approached through the medium

of rock music. The excesses to which critics accused progressive rock

groups of going also tainted the image of the concept album, making it

synonymous with pretentiousness in the minds of most contemporary

music fans. With such records as Jethro Tull’s send-up of organized

religion in Aqualung (1971) and A Passion Play (1973), Genesis’ The

Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974), an allegory of existential

alienation, and Yes’ Tales from Topographic Oceans (1974), a

sprawling, overblown musical rendering of Autobiography of a Yogi,

the concept album reached an absurd level of pomposity. When

progressive rock became déclassé in the punk era of the late 1970s,

the concept album was recognized as the symbol of its cultural and

artistic excesses.

The concept album did not die out completely with the demise of

progressive rock, just as it never was solely the province of that genre

despite common misconceptions. Ambitious and brave, singer-

songwriters periodically returned to this form throughout the late

1970s and the following decades. Notable among post-progressive

rock concept albums were Dan Fogelberg’s The Innocent Age (1981),

Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love (1985), Elvis Costello’s The Juliet

Letters (1993), and Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville (1993), a song-by-

song response to the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street. A curious

attribute of these latter day concept albums were their ability to

produce popular songs that could be enjoyed on their own terms, apart

from the overall conceptual nature of the albums to which they belonged.

Concept albums can be seen to embody two similar but separate

camps: the epic, grandiose albums conceived by progressive rock

groups, and the more subtle conceptually-based albums created by

singer-songwriters who tended to veer away from what was consid-

ered to be the mainstream. These singer-songwriters took the baton

proffered by The Beatles and The Who in a slightly different

direction. Albums like Laura Nyro’s Christmas and the Beads of

Sweat (1970), Van Dyke Parks’ Song Cycle (1968), and Lou Reed’s

Berlin (1973) directly influenced most of the post-progressive rock

albums that were produced from the mid-1970s on.

Other genres of popular music were also infiltrated by the

concept album phenomenon. Soul music in the 1970s was one

example, evidenced by works such as Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going

On (1971) and Here, My Dear (1978), Sly and the Family Stone’s

There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971), and the outrageous science fiction

storylines of several Funkadelic albums. Curtis Mayfield’s soundtrack to

the movie Superfly (1972) also deserves mention, having achieved an

artistic success far beyond that of the film. Country and Western was

another genre of popular music with its share of concept albums. It

could be argued, according to author Robert W. Butts, that some

Country and Western artists were attempting to make concept albums

long before The Beatles came along; these artists displayed a desire to

make their albums more meaningful than ‘‘a simple collection of

tunes which would hopefully provide a hit or two.’’ It was in the

1970s, however, with ‘‘the conscious and successful exploitation of

the concept of a concept,’’ according to Butts, that artists like Willie

Nelson, Emmylou Harris, and Johnny Cash fully realized the poten-

tial of the concept album within the Country and Western genre.

While the concept album in all these genres may have served to

raise the level of the respective art forms, the concept album in the

cultural consciousness of the late twentieth century exists mainly as a

symbol of excess and pseudo-intellectualism in popular music, forev-

er branded by its association with progressive rock. The concept

album did not cease to exist as a form of musical expression, but never

again did it enjoy the hold it had on the imagination of record buyers,

who viewed the phenomenon in the late 1960s and 1970s with

CONDÉ NASTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

577

excitement, and who eventually became disenchanted with its

further developments.

—Dan Coffey

F

URTHER READING:

Butts, Robert W. ‘‘More than a Collection of Songs: The Concept

Album in Country Music.’’ Mid-America Folklore. Vol. 16, No. 2,

1988, 90-99.

Covach, John, and Graeme M. Boone, editors. Understanding Rock:

Essays in Musical Analysis. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1997.

Schafer, William J. Rock Music: Where it’s Been, What it Means,

Where it’s Going. Minneapolis, Augsburg Publishing House, 1972.

Stump, Paul. The Music’s All That Matters: A History of Progressive

Rock. London, Quartet Books, 1997.

Whiteley, Sheila. The Space Between the Notes. New York,

Routledge, 1992.

Conceptual Art

Conceptual art transformed the art world beginning in the 1960s

by shifting the focus of the work from the art object itself to the ideas

and concepts that went into its creation. Such works rose to promi-

nence as a reaction to Western formalist art and to the art writings of

Clement Greenberg, Roger Fry, and Clive Bell, theorists who

championed the significance of form and modernism. Not far re-

moved from the ideas of the Dadist movement of the early twentieth

century and artist Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades, conceptualism

insists that ideas, and the implementations of them, become the art

itself; often there is an absence of an actual object. Conceptual art

worked in the spirit of postmodernism that pervaded post-1960s

American culture.

Joseph Kosuth, one of the primary participants and founders of

the conceptual art movement, first formulated the ideas of the

movement in his writings of 1969, ‘‘Art After Philosophy, I and II’’.

Along with Sol Lewitt’s 1967 treatise ‘‘Paragraphs on Conceptual

Art’’ (which coined the term ‘‘conceptual art’’), this article defined

the basic ideas of the movement. In general, conceptual art has a basis

in political, social, and cultural issues; conceptual art reacts to the

moment. Many conceptual art pieces have addressed the commer-

cialization of the art world; rebelling against the commodification of

art, artists employed temporary installations or ephemeral ideas that

were not saleable. As a result, all art, not just conceptual pieces, has

since moved outside of traditional exhibition spaces such as galleries

and museums and into the public sphere, broadening the audience.

The expansion of viable art venues allowed for a widening scope of

consideration of worthy artworks. With the prompting of conceptual

artists, photography, bookworks, performance, and installation art all

were validated as important art endeavors.

Conceptual artists such as Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, John

Baldassari, and the British group Art and Language created works

that were self-referential; the work became less about the artist and

the creative process and more about the concepts behind the work.

Contemporary artists like Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer adapted

such tenets from earlier works, and used them in a more pointed way

in the 1980s and 1990s. Their work, along with many other contempo-

rary artists’ work, addresses specific political and social issues such

as race, gender, and class. Such works attempt to reach beyond an

educated art audience to a general population, challenging all who

encounter it to reevaluate commonly held stereotypes.

—Jennifer Jankauskas

F

URTHER READING:

Colpitt, France, and Phyllis Plous. Knowledge: Aspects of Conceptual

Art. Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1992.

Kosuth, Joseph. ‘‘Art After Philosophy, I and II.’’ Studio Internation-

al. October 1969.

LeWitt, Sol. ‘‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,’’ Artforum. Sum-

mer 1967.

Meyer, Ursula. Conceptual Art. New York, E.P. Dutton, 1972.

Morgan, Robert C. Conceptual Art: An American Perspective. Jeffer-

son, North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 1994.

Condé Nast

Condé Nast is the name for both a worldwide publishing

company and the man who founded it. Condé Nast (1873-1942), the

man, was noted for his innovative publishing theories and flair for

nurturing readers and advertisers. With the purchase and upgrading of

Vogue in 1909, he established the concept of specialized or class

publications, magazines that direct their circulation to a particular

group or class of people with common interests. By 1998, Condé Nast

Publications, Inc. (CNP) held 17 such titles, many of which are the

largest in their respective markets. Like its founder, the magazine

empire is one of the most powerful purveyors of popular culture, with

an average circulation of over 13 million readers a month and an

actual readership of more than five times that. The company, now

owned by illustrious billionaire S.I. Newhouse, continues to be the

authority for many aspects of popular culture.

After purchasing Vogue in 1909, Condé Nast transformed its

original format as a weekly society journal for New York City elites

(established in 1892) to a monthly magazine devoted to fashion and

beauty. Over the century, and with a series of renowned editors,

Vogue became a preeminent fashion authority in the United States and

abroad. Its dominance and innovation spanned the course of the

century, from its transition to a preeminent fashion authority (under

the first appointed editor, Edna Woolman Chase); to the middle of the

century when Vogue published innovative art and experimented with

modernistic formats; and during the end of the century, when editor

Anna Wintour (appointed in 1988) redirected the focus of the

magazine to attract a younger audience.

Condé Nast bought an interest in House & Garden in 1911, and

four years later took it over completely. Nast transformed the maga-

zine from an architectural journal into an authority on interior design,

thereby establishing another example of a specialized publication.

Around this time, Condé Nast refined his ideas about this approach to

magazine publishing. In 1913 Nast told a group of merchants: ‘‘Time

and again the question of putting up fiction in Vogue has been brought

up; those who advocated it urging with a good show of reason that the

addition of stories and verse would make it easy to maintain a much

CONDOMS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

578

larger circulation. That it would increase the quantity of our circula-

tion we granted, but we were fearful of its effect on the ‘class’ value.’’

In 1914, Nast introduced Vanity Fair, a magazine that became an

entertaining chronicle of arts, politics, sports, and society. Over a

period of 22 years, Vanity Fair was a Jazz Age compendium of wit

and style but attracted fewer than 100,000 readers a month. Perhaps

because it was too eclectic for its time, the original Vanity Fair

eventually failed altogether (and merged with Vogue in 1936). After a

46-year absence, however, CNP revived the magazine in 1983, with a

thick, glossy, and ‘‘self-consciously literate’’ format. After nearly a

year of stumbling through an identity crisis, Newhouse brought in the

30-year-old British editor Tina Brown (who later served as editor of

The New Yorker), who remade Vanity Fair into a successful guide to

high-rent popular culture, featuring celebrity worship, careerism, and

a glossy peek inside the upper class.

In general, Condé Nast magazines were innovative not only for

their content but also for their format. In order to have the preeminent

printing available at the time, Condé Nast decided to be his own

printer in 1921, through the purchase of a small interest in the now

defunct Greenwich, Connecticut, Arbor Press. Despite the hard times

that followed the 1929 stock market crash, Condé Nast kept his

magazines going in the style to which his readers were accustomed.

Innovative typography and designs were introduced, and within the

pages of Vogue, Vanity Fair, and House & Garden, color photographs

appeared. In 1932, the first color photograph appeared on the cover

of Vogue.

Glamour was the last magazine Condé Nast personally intro-

duced to his publishing empire (1939), but the growth did not end

there. In 1959, a controlling interest in what was now Condé Nast

Publications Inc. was purchased by S.I. Newhouse. Later that same

year, Brides became wholly owned by CNP, and CNP acquired Street

& Smith Publications, Inc., which included titles such as Mademoi-

selle and the Street & Smith’s sports annuals (College Football, Pro

Football, Baseball, and Basketball). Twenty years later, Gentleman’s

Quarterly (popularly known as GQ) was purchased from Esquire,

Inc., and Self was introduced. Gourmet was acquired in 1983, the

same year that saw the revival of Vanity Fair. Rounding out the

collection, CNP added Condé Nast Traveler in 1987, Details in 1988,

Allure in 1991, Architectural Digest and Bon Appetit in 1993,

Womens’ Sports and Fitness (originally Condé Nast Sports for

Women) in 1997, and Wired magazine in 1998. Advance Publications

(the holding company that owns CNP) acquired sole ownership of

The New Yorker in 1985, but it did not become a member of the CNP

clan until 1999. In 1999, CNP moved into its international headquar-

ters in the Condé Nast Building, located in the heart of Manhattan’s

Times Square. Additionally, there are number of branch offices

throughout the United States for the more than 2,400 employed in

CNP domestic operations.

Condé Nast’s influence on American magazine publishing has

been considerable, for he introduced the specialized publications that

have since come to dominate the American magazine market. And

CNP, with its family of popular publications claiming a total readership

of over 66 million, and exposure even beyond that, has exerted a

lasting influence of American culture. With such a large reach, CNP

publications are a favorite of advertisers, who use the magazines

pages to reach vast numbers of consumers. As a source of culture,

CNP covers a variety of subjects, although none more heavily than the

beauty and lifestyle industries.

—Julie Scelfo

F

URTHER READING:

Fraser, Kennedy. ‘‘Introduction.’’ In On the Edge: Images from 100

Years of Vogue. New York, Random House, 1992.

Nast, Condé. The Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Journal of Balti-

more. June, 1913.

Nourie, Alan and Barbara Nourie. American Mass-Market Maga-

zines. New York, Greenwood Press, 1990.

Peterson, Theodore. Magazines in the Twentieth Century. Urbana,

University of Illinois Press, 1964.

Seebohm, Caroline. The Man Who Was Vogue: The Life and Times of

Condé Nast. New York, Viking, 1982.

Tebbel, John. The American Magazine: A Compact History. New

York, Hawthorn Books, 1969.

Tebbel, John and Mary Ellen Zuckerman. The Magazine in America,

1741-1990. New York, Oxford University Press, 1991.

Condoms

Once kept in the back of pharmacies, condoms have become

common and familiar items in the 1980s and 1990s because of the

AIDS crisis. Apart from sexual abstinence, condoms represent the

safest method of preventing the transmission of the HIV virus through

sexual intercourse, and, consequently, condoms figure prominently in

safer-sex campaigns. The increase in demand has led to a diversified

production to suit all tastes, so that condoms have been marketed not

only as protective items but also as toys that can improve sex.

Condoms are so ubiquitous that conservative writer Richard Panzer

has despaired that we all live in a Condom Nation and a world of latex.

Condoms are as old as history: a type of modern-day condom

may have been used by the Egyptians as far back as 1000 B.C. History

blends with myth, and several legends record the use of primitive

condoms: Minos, the king of Crete who defeated the Minotaur, is said

to have had snakes and scorpions in his seed which killed all his

lovers. He was told to put a sheep’s bladder in their vaginas, but he

opted instead to wear small bandages soaked with alum on his

penis. Condoms have been discussed by writers as diverse as, to

name but a few, William Shakespeare (who called it ‘‘the Venus

glove’’), Madame de Sévigné, Flaubert, and the legendary lover

Giacomo Casanova.

If it is difficult to come up with a date of birth for condoms, it is

even more complicated, perhaps quite appropriately, to establish who

fathered (or mothered) them. Popular belief attributes the invention of

condoms and their name to a certain Dr. Condom, who served at the

court of the British King Charles II. According to a more scientific

etymology, the name derives from the Latin ‘‘condere’’ (to hide) or

‘‘condus’’ (receptacle).

Early condoms were expensive and made of natural elements

such as lengths of sheep intestine sewn closed at one end and tied with

a ribbon around the testicles. Modern rubber condoms were created

immediately after the creation of vulcanized rubber by Charles

Goodyear in the 1840s and have been manufactured with latex since

the 1930s. Also called ‘‘sheath,’’ ‘‘comebag,’’ ‘‘scumbag,’’ ‘‘cap,’’

‘‘capote,’’ ‘‘French letter,’’ or ‘‘Port Said garter,’’ a condom is a tube

of thin latex rubber with one end closed or extended into a reservoir

tip. In the 1980s and 1990s condoms have appeared on the market in