Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

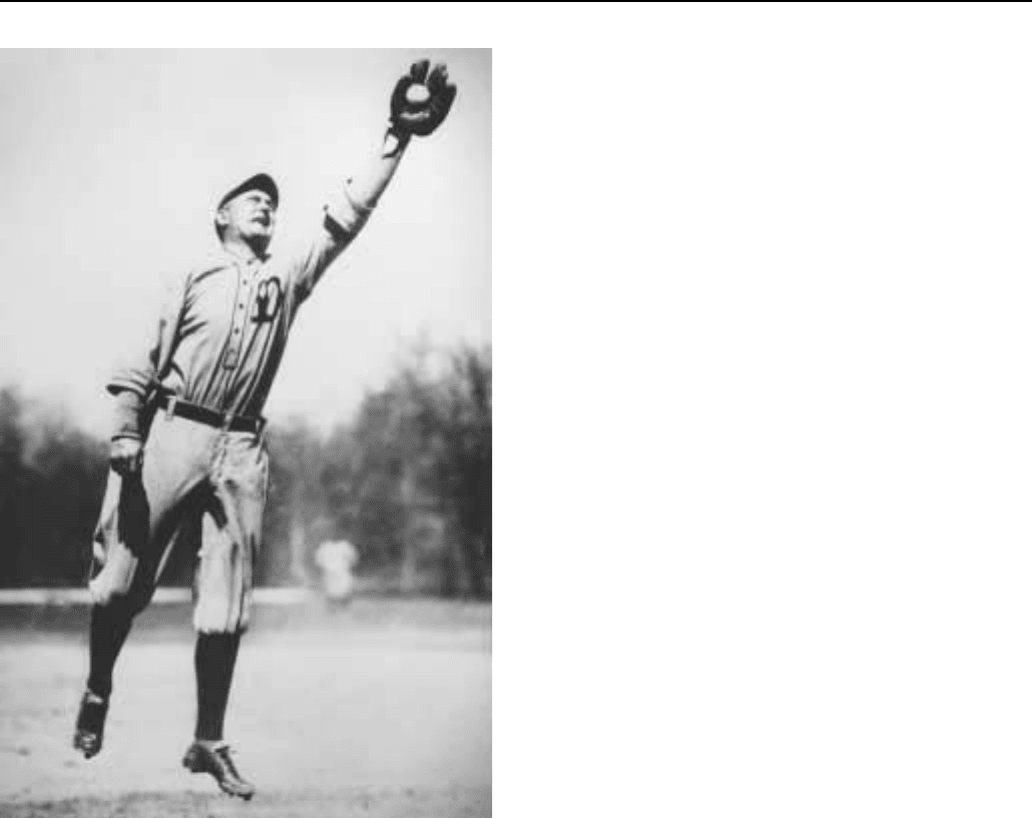

COBBENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

539

Ty Cobb

Cobb, who served as Georgia’s Governor in 1851, was captured by

the Federals at Macon in 1865.

Cobb’s father impressed upon him the need to uphold the family

tradition by either entering a profession, such as medicine or the law,

or by attending West Point. Cobb, however, showed little interest in

these potential futures. In 1901, at the age of 15, Cobb became aware

of major league baseball. He learned, to his astonishment, that in the

game he and his friends played with a flat board and a homemade

twine ball major league celebrities could earn up to $8,000 per season.

In 1902, against his father’s wishes, Cobb joined the Royston

Reds, a semi-pro team that toured Northeastern Georgia. Semi-pro

‘‘town-ball’’ was tough stuff. At this time one of the rules held over

from the game’s pioneer forms was ‘‘soaking,’’ in which base runners

could be put out not only by throws to a bag and by hand, but by

throwing to hit them anywhere on the body. Hitting the runner in the

skull was preferable, because it might take a star opponent out of the

lineup. On more than one occasion Cobb was put out by a ‘‘soaker’’ to

the ear, which did little to endear baseball to his father.

In 1904 Cobb succeeded in making the roster of the class ‘‘C’’

Augusta Tourists, a league that drew scouts from the major leagues.

At Augusta Cobb began to develop his distinctive playing style.

Rather than pull pitches to his natural direction of right field, the left-

handed Cobb stood deep in the batter’s box, choked up on his 38

ounce bat with a split hands grip, and opened his stance as the pitcher

fired the ball. His trademark was to chop grounders and slice line-

drives through third-base gaps and into an often unguarded left-field.

The Cobb-style bunt, destined to become one of the most deadly

weapons since Willie Keeler’s ‘‘Baltimore Chop,’’ took shape when

Cobb retracted his bat and punched the ball to a selected spot between

the third baseman and the pitcher, just out of reach. He also began to

pull bunts for base hits and once on base he ran with wild abandon,

stealing when he wished and running through the stop signs of base

coaches, always using his great speed to wreak havoc with opposing

defenses. Included in his techniques was a kick slide, in which he

would kick his lead leg at the last minute in an effort to dislodge the

ball, the glove, and perhaps even the hand of a middle infielder

waiting to tag him out. This would, at the major league level, develop

into the dreaded ‘‘Cobb Kiss,’’ in which Cobb would slide, or often

leap, feet first into infielders and catchers with sharpened spikes

slashing and cutting. Unique among players of his era, Cobb kept

notebooks filled with intelligence on opposing pitchers and defenses.

He studied the geometry and angles of the baseball field, and through

his hitting and base running strategies engaged in what he called

‘‘scientific baseball,’’ a style that would revolutionize the game in the

so-called ‘‘dead-ball’’ era before Babe Ruth.

But although he could outrun everybody, had a rifle arm in

center field, and hit sizzling singles and doubles to all fields, already

at Augusta Cobb was hated by his teammates. He was a loner who

early in his career did not drink or chase women, and preferred to read

histories and biographies in his room. He constantly fought with his

manager, whose signs he regularly ignored. Eventually, none of his

teammates would room with him, especially after he severely beat

pitcher George Napoleon ‘‘Nap’’ Rucker, a roommate of Cobb’s for a

short time. Rucker’s ‘‘crime’’ had been taking the first hot bath in

their room after a game. Cobb’s explanation to a bloodied Rucker was

‘‘I’ve got to be first at everything—all the time!’’ Rucker and the

other Tourists considered Cobb mentally unbalanced and dangerous

if provoked.

On August 8, 1905 William Cobb was killed by a shotgun blast,

fired by his young wife Amanda. Although eventually cleared of

charges of voluntary manslaughter, rumors of marital infidelity and

premeditated murder continued to swirl around Cobb’s mother. The

violent death of his father, who had never seen Cobb play but who had

softened toward his son’s career choice shortly before his death, made

Cobb’s volatile nature even worse. As Cobb later observed of himself

during this period, ‘‘I was like a steel spring with a growing and

dangerous flaw in it. If it is wound too tight or has the slightest weak

point, the spring will fly apart and then is done for.’’

Late in the 1905 season, a Detroit Tiger team weakened by

injuries needed cheap replacements and purchased Cobb’s contract.

Cobb joined major league baseball during a period in which the game

was reshaping itself. In 1901 the foul-strike rule had been adopted,

whereby the first and second foul balls off the bat counted as strikes.

But of greater importance were the actions of Byron ‘‘Ban’’ Johnson,

who changed the name of his minor Western League to the American

League and began signing major league players in direct competition

with the National League. By 1903 bifurcated baseball and the

modern World Series were born, leading to a boom in baseball’s

popularity as Cobb joined the Tigers.

Cobb impressed from his first at bat, when he clubbed a double

off of ‘‘Happy’’ Jack Chesbro, a 41 game winner in 1904. His

COCA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

540

aggressive style won over the fans immediately, but from the begin-

ning his Tiger teammates despised Cobb. Most of the Tigers were

northerners and mid-westerners, and Cobb, with his pronounced

southern drawl and stiff, formal way of addressing people stood out.

But more importantly, his sometimes spectacular play as a rookie

indicated that he might be a threat to the established outfield corps,

and in the hardscrabble game of the turn of the twentieth century such

rookies faced intense hazing. Cobb fought back against the veterans

and took to carrying a snub-nosed Frontier Colt pistol on his person

for protection. The tension led to a mental breakdown for Cobb in

mid-summer 1906, leading to a 44 day stay in a sanatorium. Upon his

release, Cobb returned to the Tigers with an even greater determina-

tion to succeed. ‘‘When I got back I was going to show them some

ballplaying like the fans hadn’t seen in some time,’’ Cobb later recalled.

Cobb fulfilled his promise. He lead Detroit to the World Series in

1907, 1908, and 1909, hitting a combined .361 in those seasons with a

remarkable 164 stolen bases. Although Detroit faded as a contender

after that, Cobb’s star status continued to rise. In 1911 he hit .420 with

83 stolen bases and 144 RBIs (runs batted in). In 1912 he hit .410 with

61 steals and 90 RBIs. He batted over .300, the traditional benchmark

for batting excellence, in 23 consecutive seasons, including a .323

mark in 1928, his final season, at the age of 42. But while Cobb

remained remarkably consistent, the game of baseball changed around

him. In 1919 the Boston Red Sox sold their star player, Babe Ruth, to

the New York Yankees. In 1920 Ruth hit 54 Home Runs, and in 1921

he hit 59. The ‘‘dead-ball’’ era and scientific baseball was replaced by

the ‘‘rabbit-ball’’ era and big bang baseball. Cobb felt that Ruth was

‘‘unfinished’’ and that major league pitchers would soon adjust to his

style; they did not. Cobb never adjusted or changed his style. ‘‘The

home run could wreck baseball,’’ he warned. ‘‘It throws out a lot of

strategy and makes it fence-ball.’’ As player-manager late in his

career, Cobb tried to match the Yankee’s ‘‘fence-ball’’ with his own

‘‘scientific ball’’—and he failed miserably.

Along the way, Cobb initiated a move toward player emancipa-

tion by agitating in Congress for an investigation of baseball’s reserve

clause that tied a player to one team for life. He took the lead in

forming the Ball Players Fraternity, a nascent player’s union. In

retirement he spent some of his estimated $12 million fortune,

compiled mainly through shrewd stock market investments, in sup-

porting destitute ex-ballplayers and their families. But he also burned

all fan mail that reached him and ended long-term relationships with

friends such as Ted Williams over minor disputes. When he died in

1961, just three men from major league baseball attended his funeral,

one of which was old ‘‘Nap’’ Rucker from his Augusta days. Not a

single official representative of major league baseball attended the

funeral of the most inventive, detested, and talented player in

baseball history.

—Todd Anthony Rosa

F

URTHER READING:

Alexander, Charles. Ty Cobb. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1984.

Astor, Gerald, and Joe Falls. The Detroit Tigers. New York, Walker

& Company, 1989.

Cobb, Ty, with Al Stump. My Life in Baseball: The True Record.

Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1961.

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Early Years. New York, Oxford

University Press, 1960.

———. Baseball: The Golden Age. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1971.

Stump, Al. Cobb: A Biography. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Algonquin

Books, 1994.

Ward, Geoffrey C. Baseball: An Illustrated History. New York, A.A.

Knopf, 1994.

Coca, Imogene (1908—)

Imogene Coca is best remembered as one of the driving forces

behind the popular variety show Your Show of Shows (1950-54), in

which she starred with Sid Caesar. Her physical, non-verbal comedy

perfectly offset Caesar’s bizarre characterizations and antics. Coca

won an Emmy for Best Actress in 1951 for her work on the series.

After Your Show of Shows was canceled, however, neither Coca nor

Caesar were ever able to attain a similar level of popularity and all of

Coca’s sitcom attempts were soon canceled. Even a series that

reunited the two in 1958 was unsuccessful, proving that television

popularity is more a function of viewer mood than an actor’s talent.

—Denise Lowe

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946-Present. New York,

Ballentine Books, 1995.

Martin, Jean. Who’s Who of Women in the Twentieth Century. New

York, Crescent Books, 1995.

Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, also known as Coke, began in the chaos of the post-

Reconstruction South. In May 1886, Georgia pharmacist John Styth

Pemberton succeeded in creating what he intended, a temperance

drink. With cries against alcohol reaching a fever pitch in the region

Pemberton worked to create a drink that could satisfy the anti-alcohol

crowd as well as his need to turn a profit. In the ensuing mixing and re-

mixing he came up with the syrup base for Coca-Cola. The reddish

brown color and ‘‘spicy’’ flavor of the drink helped mask the illegal

alcohol that some of his early customers added to the beverage. Little

did he know that this new drink, made largely of sugar and water,

would quickly become the most popular soft drink in the United

States and, eventually, the entire world.

Although John Pemberton created the formula for Coca-Cola it

fell to others to turn the product into a profitable enterprise. Fellow

pharmacist Asa Candler bought the rights to Coke in 1888, and he

would begin to push the drink to successful heights. Through a variety

of marketing tools Candler put Coca-Cola onto the long road to

prosperity. Calendars, pens, metal trays, posters, and a variety of

other items were emblazoned with the Coke image and helped breed

familiarity with the drink. Additionally, although the beverage in-

cluded negligible amounts of cocaine, Candler gave in to the senti-

ment of the Progressive Era and removed all traces of cocaine from

Coca-Cola in 1903. Candler followed the slight formula switch with

an advertising campaign emphasizing the purity of the drink. The ad

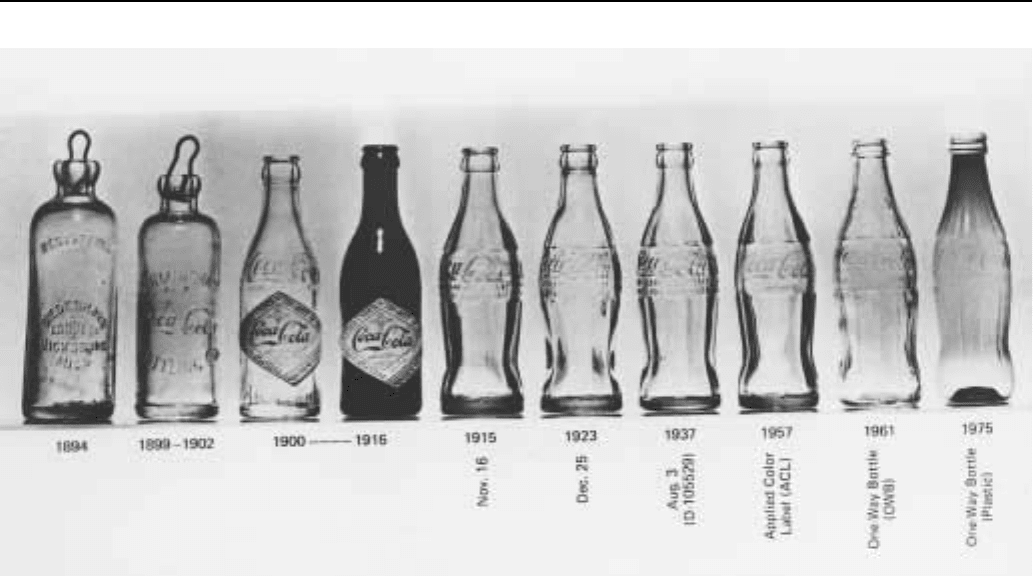

COCA-COLAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

541

Assorted bottle styles of Coke.

campaign was enhanced by the development of the unique Coca-Cola

bottle in 1913. The new Coke bottle, with its wide middle and ribbed

sides, made the Coca-Cola bottle, and by relation its contents,

instantly identifiable.

For all of the success that he had engineered at Coca-Cola, Asa

Candler lost interest in the soft drink business. Candler turned the

company over to his sons who would in turn eventually sell it to

Ernest Woodruff. It was Woodruff, and eventually his son, Robert,

who guided the company to its position of leadership in the soda-pop

industry. As one company employee remarked ‘‘Asa Candler gave us

feet, but Woodruff gave us wings.’’ The Woodruffs expanded compa-

ny operations, initiated the vending-machine process, changed foun-

tain distribution to ensure product uniformity and quality, and presid-

ed over the emergence of the six-pack. It was also the Woodruffs who

recognized that Coke’s greatest asset was not what it did, but what it

could potentially represent; accordingly, they expanded upon compa-

ny advertising in order to have Coke identified as the pre-eminent soft

drink and, ultimately, a part of Americana.

Coca-Cola advertising was some of the most memorable in the

history of American business. Through the work of artists such as

Norman Rockwell and Haddon Sundblom, images of Coca-Cola were

united with other aspects of American life. In fact, it was not until

Sundblom, through a Coke advertisement, provided the nation with a

depiction of the red-suited, rotund Santa Claus, that such an image

(and by relation Coca-Cola) was identified with the American version

of Christmas. Coke’s strategic marketing efforts, through magazines,

billboards, calendars, and various other product giveaways embla-

zoned with the name Coca-Cola, made the product a part of American

culture. The success of Coke advertising gave the product an appeal

that stretched far beyond its simple function as a beverage to quench

the thirst. Coke became identified with things that were American, as

much an icon as the Statue of Liberty or Mount Rushmore. This shift

to icon status was catalyzed by the company’s actions during

World War II.

At the outset of the war Coke found its business potentially

limited by wartime production statutes. Sugar, a major ingredient in

the drink, was to be rationed in order to ensure its availability to the

nation’s military forces. The company, though not necessarily facing

a loss of market share, faced the serious possibility of zero growth

during the conflict. Therefore, Robert Woodruff announced that the

company would work to ensure that Coke was available to every

American serviceman overseas. Through this bold maneuver Coca-

Cola was eventually placed on the list of military necessities and

allowed to circumvent limits on its sugar supply. Also, thanks in part

to Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, the company was able to avoid

the massive expense of ensuring Coke’s delivery. Marshall believed

that troop morale would be improved by the availability of Coca-

Cola, and that it was a good alternative to alcohol. Therefore, he

allowed for entire bottling plants to be transported overseas at

government expense. Thanks to Marshall and others Coca-Cola was

able to expand its presence overseas at a faster rate and at less expense

than other beverages.

Thousands of American servicemen, from Dwight Eisenhower

to the common soldier, preferred Coke to any other soft drink. The

availability of the beverage in every theater of the war helped Coke to

be elevated in the minds of GI’s as a slice of America. In many of their

letters home, soldiers identified the drink as one of the things they

were fighting for, in addition to families and sweethearts. Bottles of

Coke were auctioned off when supplies became limited, were flown

along with bombing sorties, and found their way onto submarines.

One GI went so far as to call the liquid ‘‘nectar of the Gods.’’ Thanks

to its presence in the war effort, the affinity which GI’s held for the

beverage, and the establishment of a presence overseas, Coke became

identified by Americans and citizens of foreign countries with the

COCAINE/CRACK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

542

American Way. After World War II, Coca-Cola was on its way to

becoming one of a handful of brands recognized around the world.

However, the presence of Coca-Cola was not always welcomed

overseas. During the political and ideological battles of the Cold War,

Coke was targeted by European communists as a symbol of the

creeping hegemony of the United States. The drink found itself under

attack in many European countries and in some quarters its existence

was denounced as ‘‘Coca-Colonialism.’’ In addition, the drink often

found its presence opposed by local soft drink and beverage manufac-

turers. A variety of beverage manufacturers in Germany, Italy, and

France actively opposed the spread of Coca-Cola in their countries.

Despite the opposition, however, the spread of Coca-Cola continued

throughout the Cold War. In some cases the sale of the soft drink

preceded or immediately followed the establishment of relations

between the United States and another country. By the 1970s, the

worldwide presence of Coke was such that company officials could

(and did) claim that, ‘‘When you don’t see a Coca-Cola sign, you have

passed the borders of civilization.’’

Beginning in the 1970s, Coca-Cola found its greatest challenges

in the domestic rather than international arena. Facing the growth of

its rival, Pepsi-Cola, Coke found itself increasingly losing its market

share. Coke executives were even more worried when the Pepsi

Challenge convincingly argued that even among Coke loyalists the

taste of Pepsi was preferred to that of Coke. The results of the

challenge led Coke officials to conclude that the taste of the drink was

inferior to that of Pepsi and that a change in the formula was

necessary. The result of this line of thinking was the marketing

debacle surrounding New Coke.

In the history of corporate marketing blunders the 1983 intro-

duction of New Coke quickly took its place alongside the Edsel. After

New Coke was introduced company telephone operators found

themselves besieged by irate consumers disgusted with the product

change. Coke’s error was that blind taste tests like the Pepsi Chal-

lenge prevented the consumer from associating the thoughts and

traditions with a particular soda. Caught up in ideas of product

inferiority the company seemingly forgot its greatest asset—the

association that it had with the life experiences of millions of

consumers. Many Americans associated memories of first dates,

battlefield success, sporting events, and other occasions with the

consumption of Coca-Cola. Those associations were something that

could not be ignored or rejected simply because when blindfolded

customers preferred the taste of one beverage over another. In many

cases the choice of a particular soft drink was something passed down

from parents to children. Consequently, the taste tests would not make

lifelong Coke drinkers switch to a new beverage; the tradition and

association with Coca-Cola were too powerful for such a thing

to occur.

After introducing New Coke the company found itself assaulted

not for changing the formula of a simple soft drink, but for tampering

with a piece of Americana. Columnists editorialized that the next step

would be changing the flag or tearing down the Statue of Liberty.

Many Americans rejected New Coke not for its taste but for its mere

existence. Tradition, as the Coca-Cola company was forced to admit,

took precedence over taste. Four months after it was taken off of the

shelves, the traditionally formulated Coke was returned to the market-

place under the name Coca-Cola Classic. Company president Don

Keough summed up the episode by saying ‘‘Some critics will say

Coca-Cola made a marketing mistake. Some critics will say that we

planned the whole thing. The truth is we are not that dumb and not that

smart.’’ What the company was smart enough to do was to recognize

that they were more than a soft drink to those who consumed the

beverage as well as to those who did not. What they were to seemingly

the entire nation, regardless of individual beverage preference, was a

piece of America as genuine and identifiable with the country as the

game of baseball.

As a beverage the consumption of Coca-Cola has a rather limited

physical impact. The drink was able to quench the thirst and to

provide a small lift due to its caffeine and sugar content. Beyond its

use, however, Coca-Cola was, as Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper

editor William Allen White once remarked, the ‘‘sublimated essence

of all that America stands for. . . .’’ Though the formula underwent

changes and the company developed diet, caffeine free, and cherry-

flavored versions, what Coca-Cola represents has not changed. Coca-

Cola, a beverage consumed by presidents, monarchs, and consumers

the world over has remained above all else a symbol of America and

its way of life.

—Jason Chambers

F

URTHER READING:

Allen, Frederick. Secret Formula: How Brilliant Marketing and

Relentless Salesmanship Made Coca-Cola the Best-Know Prod-

uct in the World. New York, HarperCollins, 1994.

Dietz, Lawrence. Soda Pop: The History, Advertising, Art, and

Memorabilia of Soft Drinks in America. New York, Simon and

Schuster, 1973.

Hoy, Anne. Coca-Cola: The First Hundred Years. Atlanta, The Coca-

Cola Company, 1986

Kahn, Jr. E.J. The Big Drink: The Story of Coca-Cola. New York,

Random House, 1960.

Louis, J.C., and Yazijian, Harvey Z. The Cola Wars. New York,

Everest House, Publishers, 1980.

Thomas, Oliver. The Real Coke, The Real Story. New York, Penguin

Books, 1986

Watters, Pat. Coca-Cola: An Illustrated History. Garden City,

Doubleday, 1978.

Cocaine/Crack

Erythroxlon coca, a shrub indigenous to the upper jungles of the

Andes mountains in South America, has been consumed for mil-

lennia by the various Indian tribes that have inhabited the re-

gion. The primary alkaloid of this plant, cocaine (first called

erythroxyline), earned a reputation throughout the twentieth century

as the quintessential American drug. Psychologist Ronald Siegel

noted that ‘‘its stimulating and pleasure-causing properties reinforce

the American character with its initiative, its energy, its restless

activity and its boundless optimism.’’ Cocaine—which one scholar

called ‘‘probably the least understood and most consistently misrep-

resented drug in the pharmacopoeia’’—symbolizes more than any

other illicit drug the twin extremes of decadent indulgence and dire

poverty that characterize the excesses of American capitalism. The

drug has provoked both wondrous praise and intense moral condem-

nation for centuries.

COCAINE/CRACKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

543

For the Yunga and Aymara Indians of South America, the

practice of chewing coca was most likely a matter of survival. The

coca leaf, rich in vitamins and proteins as well as in its popular mood-

altering alkaloid, was an essential source of nourishment and strength

in the Andes, where food and oxygen were scarce. The word ‘‘coca’’

probably simply meant ‘‘plant,’’ suggesting the pervasiveness of the

shrub in ancient life. The leaf also had both medical and religious

applications throughout the pre-Inca period, and the Inca empire

made coca central to religious cosmology.

Almost immediately upon its entrance into the Western frame of

reference, the coca leaf was inextricable from the drama and violence

of imperial expansion. In the sixteenth century the Spaniards first

discounted Indian claims that coca made them more energetic, and

outlawed the leaf, believing it to be the work of the Devil. After seeing

that the Indians were indeed more productive laborers under the leaf’s

influence, they legalized and taxed the custom. These taxes became

the chief support for the Catholic church in the region. An awareness

of the political significance of coca quickly developed among the

Indians of the Andean region, and for centuries the leaf has been a

powerful symbol of the strength and resilience of Andean culture in

the face of genocidal European domination.

In the mid-nineteenth century, when the cocaine alkaloid was

isolated and extracted, cocaine began its rise to popularity in Europe

and North America. The drug is widely praised during this period for

its stimulating effects on the central nervous system, with many

physicians and scientists, including Sigmund Freud, extolling its

virtues as a cure for alcohol and morphine addiction. Others praised

its appetite-reduction properties, while still others hailed it as an

aphrodisiac. In 1859 Dr. Paolo Mantegazza, a prominent Italian

neurologist, wrote, ‘‘I prefer a life of ten years with coca to one of a

hundred thousand without it.’’ Americans beamed with pride at the

wonder drug that had been discovered on their continent; one Ameri-

can company advertised at least 15 different cocaine products and

promised that the drug would ‘‘supply the place of food, make the

coward brave, the silent eloquent and render the sufferer indifferent

to pain.’’

Angelo Mariana manufactured coca-based wine products, boast-

ing having collected 13 volumes of praise from satisfied customers,

who included well-known political leaders, artists, and an alarming

number of doctors, ‘‘including physicians to all the royal households

of Europe.’’ Ulysses S. Grant, according to Mariana, took the coca-

wine elixir daily while composing his memoirs. In 1885 John S.

Pemberton, an Atlanta pharmacist, also started selling cocaine-based

wine, but removed the alcohol in response to prohibitionist sentiment

and began marketing a soft drink with cocaine and gotu kola as an

‘‘intellectual beverage and temperance drink’’ which he called

Coca-Cola.

It was not until the late 1880s and 1890s that cocaine’s addictive

properties begin to capture public attention in the United States.

While cocaine has no physically addictive properties, the psychologi-

cal dependence associated with its frequent use can be just as

debilitating as any physical addiction. By the turn of the twentieth

century the potential dangers of such dependence had become clear to

many, and reports of abuse began to spread.

By 1900 the drug was at the center of a full-scale moral panic.

Scholars have noted the race and class overtones of this early cocaine

panic. In spite of little actual evidence to substantiate such claims, the

American Journal of Pharmacy reported in 1903 that most cocaine

users were ‘‘bohemians, gamblers, high- and low-class prostitutes,

night porters, bell boys, burglars, racketeers, pimps, and casual

laborers.’’ The moral panic directly targeted blacks, and the fear of

cocaine fit perfectly into the dominant racial discourses of the day. In

1914 Dr. Christopher Koch of Pennsylvania’s State Pharmacy Board

declared that ‘‘Most of the attacks upon the white women of the South

are the direct result of a cocaine-crazed Negro brain.’’ David Musto

characterized the period in this way: ‘‘So far, evidence does not

suggest that cocaine caused a crime wave but rather that anticipation

of black rebellion inspired white alarm. Anecdotes often told of

superhuman strength, cunning, and efficiency resulting from cocaine.

These fantasies characterized white fear, not the reality of cocaine’s

effects, and gave one more reason for the repression of blacks.’’

Cocaine was heavily restricted by the Harrison Narcotics Act in

1914 and was officially identified as a ‘‘narcotic’’ and outlawed by

the United States government in 1922, after which time its use went

largely underground until the late 1960s and early 1970s, when it

spread first in the rock ’n’ roll subculture and then through the more

affluent sectors of American society. It became identified again with

American wealth and power, and its dangers were downplayed or

ignored. As late as 1980 the use of powder cocaine was recognized

even by some medical authorities as ‘‘very safe.’’

During the early 1970s, however, a coca epidemic began quietly

spreading throughout South America. While the centuries-old prac-

tice of chewing fresh coca leaves by coqueros had never been

observed to cause abuse or mania, in the 1970s a new practice

developed of smoking a paste, called basuco or basé, that was a

byproduct of the cocaine manufacturing process. Peruvian physicians

began publicly warning of a paste-smoking epidemic. The reports,

largely ignored at the time in the United States, told of basuco-

smoking pastaleros being driven crazy by the drug, smoking enor-

mous quantities chronically, in many cases until death.

In early 1974, a misinterpretation of the term basé led some San

Francisco chemists to reverse engineer cocaine ‘‘base’’ from pure

powder cocaine, creating a smokable mixture of cocaine alkaloid. The

first ‘‘freebasers’’ thought they were smoking basuco like the pastaleros,

but in reality they were smoking ‘‘something that nobody else on the

planet had ever smoked before.’’ The costly and inefficient procedure

of manufacturing freebase from powder cocaine ensured that the drug

remained a celebrity thrill. This was dramatized in comedian Richard

Pryor’s near-death experience with freebase in 1980.

Crack cocaine was most likely developed in the Bahamas in the

late 1970s or early 1980s when it was recognized that the expensive

and dangerous procedures required to manufacture freebase were

unnecessary. A smokable cocaine paste, it was discovered, could be

cheaply and easily manufactured by mixing even low quality cocaine

with common substances such as baking soda. This moment coincid-

ed with a massive glut of cheap Colombian cocaine in the internation-

al market. The supply of cocaine coming into the United States more

than doubled between 1976 and 1980. The price of cocaine again

dropped after 1980, thanks at least partly to a CIA (Central Intelli-

gence Agency)-supported coup in Bolivia.

Throughout the 1980s, cocaine again became the subject of an

intense moral panic in the United States. In October of 1982, only

seven months after retracting his endorsement for stronger warnings

on cigarette packs, President Reagan declared his ‘‘unshakable’’

commitment ‘‘to do whatever is necessary to end the drug menace.’’

The Department of Defense and the CIA were officially enlisted in

support of the drug war, and military activity was aimed both at Latin

American smugglers and at American citizens. While the United

COCKTAIL PARTIES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

544

States Administration frequently raised the specter of ‘‘narcoterrorism’’

associated with Latin American rebels, most analysts agree that

United States economic and military policy has consistently benefitted

the powerful aristocracies who manage the cocaine trade.

In the mid-1980s, in the heat of the Iran-Contra scandal, evi-

dence that members of the CIA’s contra army in Nicaragua were

heavily involved in the cocaine trade began to surface in the American

press. This evidence was downplayed and denied by government

officials, and generally ignored by the public until 1996, when an

explosive newspaper series by Gary Webb brought the issue to public

attention. While Webb’s award-winning series was widely discredit-

ed by the major media, most of his claims have been confirmed by

other researchers, and in some cases even admitted by the CIA in its

self-review. The Webb series contributed to perceptions in African-

American communities that cocaine was part of a government plot to

destroy them.

As was the case at the turn of the twentieth century, the moral

outrage at cocaine turned on race and class themes. Cocaine was

suddenly seen as threatening when it became widely and inexpensive-

ly available to the nation’s black and inner-city poor; its widespread

use by the urban upper class was never viewed as an epidemic. The

unequal racial lines drawn in the drug war were recognized by the

United States Sentencing Commission, which in 1995 recommended

a reduction in the sentencing disparities between crack and powder

cocaine. Powder cocaine, the preferred drug of white upper class

users, carries about 1/100th the legal penalties of equivalent amounts

of crack.

The vilified figure of the inner-city crack dealer, however, may

represent the ironic underbelly to the American character and spirit

that has been associated with cocaine’s stimulant effects. Phillippe

Bourgois noted that ‘‘ambitious, energetic, inner-city youths are

attracted to the underground economy precisely because they believe

in Horatio Alger’s version of the American dream. They are the

ultimate rugged individualists.’’

—Bernardo Alexander Attias

F

URTHER READING:

Ashley, Richard. Cocaine: Its History, Uses, and Effects. New York,

Warner Books, 1975.

Belenko, Steven R. Crack and the Evolution of Anti-Drug Policy.

Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Bernfeld, Siegfried. ‘‘Freud’s Studies on Cocaine, 1884-1887.’’

Yearbook of Psychoanalysis. Vol. 10, 1954-1955, 9-38.

Eddy, Paul, Hugo Sabogal, and Sara Walden. The Cocaine Wars.

New York, W. W. Norton, 1988.

Grinspoon, Lester, and James B. Bakalar. Cocaine: A Drug and its

Social Evolution. New York, Basic Books, 1976.

Morales, Edmundo. Cocaine: White Gold Rush in Peru. Tuscon,

University of Arizona Press, 1989.

Mortimer, W. G. Peru History of Coca, ‘‘The Divine Plant’’ of the

Incas. New York, J. H. Vail and Company, 1901.

Musto, David F. ‘‘America’s First Cocaine Epidemic.’’ Washington

Quarterly. Summer 1989, 59-64.

———. The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control. New

Haven, Connecticut, Yale, 1973.

Reeves, Jimmie L., and Richard Campbell. Cracked Coverage:

Television News, the Anti-Cocaine Crusade, and the Reagan

Legacy. Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press, 1994.

Webb, Gary. Dark Alliance: The CIA, the Contras, and the Crack

Cocaine Explosion. New York, Seven Stories Press, 1998.

Cocktail Parties

Noted essayist and tippler H. L. Mencken once wrote that the

cocktail was ‘‘the greatest of all the contributions of the American

way of life to the salvation of humanity.’’ While Mencken’s effusive

evaluation of the cocktail might be challenged today, the cocktail and

the cocktail party remain a distinctively American contribution to the

social landscape of the twentieth century.

Although the cocktail party is most closely associated with the

Cold War era, Americans were toasting with mixed drinks well before

the 1950s. The origin of the word cocktail remains the subject of some

debate, with a few bold scholars giving the honors to the troops of

George Washington, who raised a toast to the ‘‘cock tail’’ that

adorned the General’s hat. Whatever its origins, by the 1880s the

cocktail had become an American institution, and by the turn of the

century women’s magazines included recipes for cocktails to be made

by hostesses, to insure the success of their parties.

The enactment of the 18th Amendment in 1920 made Prohibi-

tion a reality, and cocktails went underground to speakeasies. These

illegal night clubs caused a small social revolution in the United

States, as they allowed men and women to drink together in public for

the first time. But it was not until after World War II that the cocktail-

party culture became completely mainstream. As young people

flocked to the new suburbs in the 1950s, they bought homes that were

far removed from the bars and lounges of the city. Cocktail parties

became a key form of socializing, and the market for lounge music

records, cocktail glasses, and shakers exploded. By 1955 even the

U.S. government had realized the importance of these alcohol-

oriented gatherings, as the National Institute of Mental Health of the

U.S. Public Health Service launched a four-year sociological study of

cocktail parties, with six lucky agents pressed into duty attending and

reporting back on high-ball-induced behavior. The testing of atomic

bombs during the early 1950s in the deserts of Nevada sparked a

short-lived fad for atomic-themed cocktails.

The most emblematic drink of cocktail culture remains the

martini. The outline of the distinctively shaped glass has become a

universal symbol for bars and lounges. As with many aspects of

cocktail culture, the origins of the martini remain hazy. One history

suggests that the first martini was mixed by noted bartender ‘‘Profes-

sor’’ Jerry Thomas at the bar of the Occidental Hotel in San Francisco

in the early 1860s for a miner on his way to the town of Martinez. The

martini was insured lasting fame by being the favored libation of the

popular movie spy James Bond, whose strict allegiance to a martini

that was ‘‘shaken, not stirred’’ so that the gin not be ‘‘bruised,’’

encouraged a generation of movie-goers to abandon their swizzle

sticks in favor of a cocktail shaker.

In the mid-1990s, cocktail culture experienced a revival through

the efforts of a few well-publicized bands interested in reviving the

cocktail party lounge sound. The press dubbed the movement, sparked

by the 1994 release of Combustible Edison’s album I, Swinger,

‘‘Cocktail Nation,’’ and young people appropriated the sleek suits,

CODYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

545

snazzy shakers and swinging sounds made popular by their parents’

generation. Cocktail nostalgia reached its peak with the 1996 release

of Jon Favreau’s Swingers, a movie about cocktail culture in contem-

porary Los Angeles.

—Deborah Broderson

F

URTHER READING:

Edmunds, Lowell. Martini Straight Up: The Classic American Cock-

tail. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Lanza, Joseph. The Cocktail: The Influence of Spirits on the American

Psyche. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

Murdock, Catherine. Domesticating Drink: Women, Men and Alco-

hol in America 1870-1940. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1998.

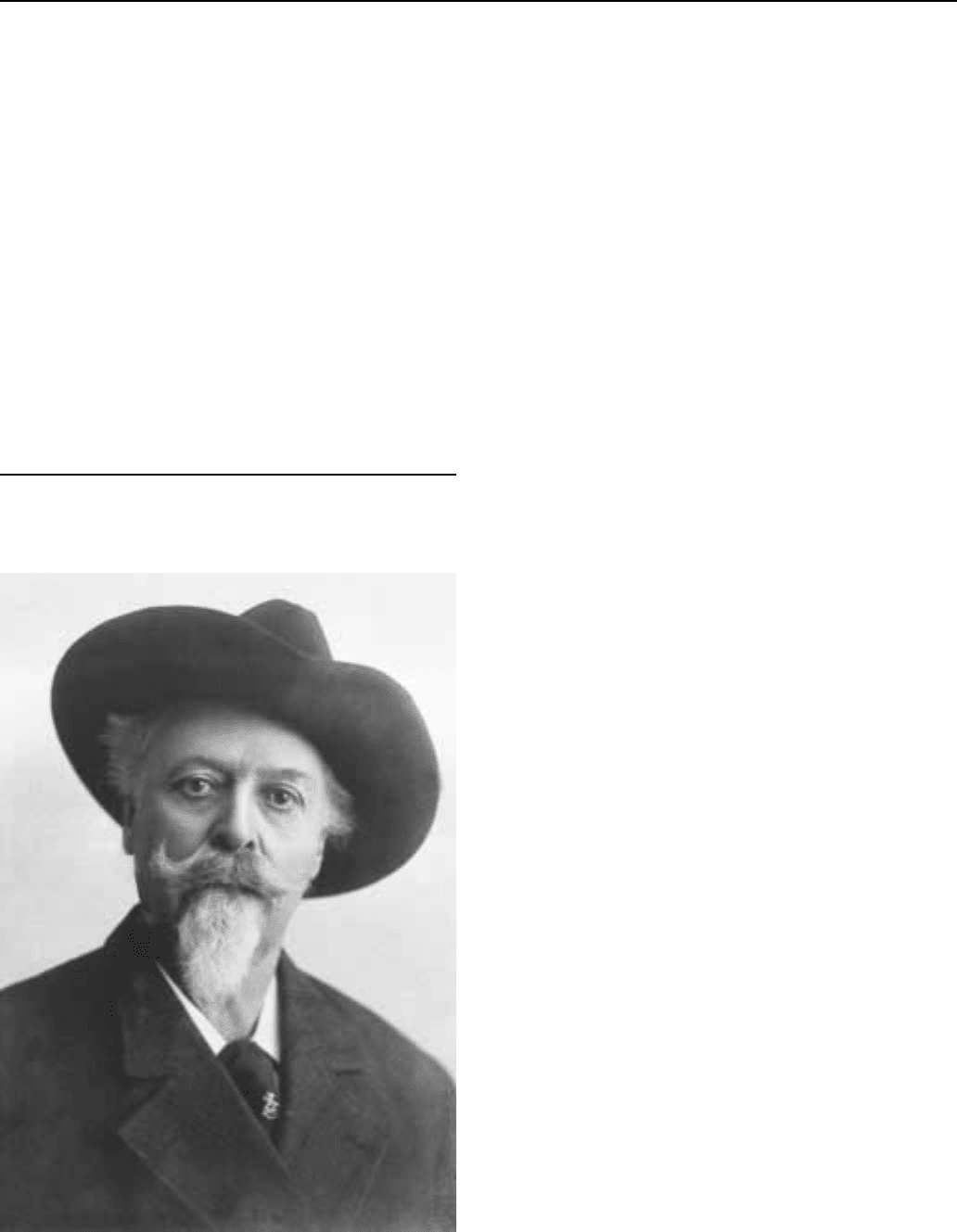

Cody, Buffalo Bill, and his

Wild West Show

Buffalo Bill was not the originator of the Wild West Show or,

indeed, the only person to stage one. Frontier extravaganzas had

William Cody

existed in one form or another from as early as 1843. Yet Buffalo Bill

Cody is largely responsible for creating our romantic view of the Old

West that continues largely unabated to this day. This is due to a

combination of factors, not the least of which was Cody’s own flair

for dramatizing his own real life experiences as a scout, buffalo

hunter, and Indian fighter.

The legend of William F. Cody began in 1867 when, as a

21-year-old young man who had already lived a full life as a Pony

Express rider, gold miner, and ox team driver, he contracted to supply

buffalo meat for construction workers on the Union Pacific railroad.

Although he did not kill the number of huge beasts attributed to him

(that was accomplished by the ‘‘hide hunters’’ who followed and

nearly decimated the breed), he was dubbed Buffalo Bill. He followed

this experience with a four-year stint as Chief of Scouts for the Fifth

United States Cavalry under the leadership of former Civil War hero

Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan. During this service, Cody par-

ticipated in 16 Indian skirmishes including the defeat of the Cheyenne

at Summit Springs in 1869. After this, Cody earned a living as a

hunting guide for parties of celebrities, who included politicians and

European royalty. On one of these, he encountered the author Ned

Buntline who made him the hero of a best-selling series of stories in

The New York Weekly, flamboyantly titled ‘‘The Greatest Romance

of the Age.’’ These stories spread the buffalo hunter’s fame around

the world.

After witnessing a Nebraska Independence Day celebration in

1883, Cody seized upon the idea of a celebration of the West, and

played upon his newfound fame to create Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,

an outdoor extravaganza that depicted life on the frontier from his

unique perspective. The show (although he steadfastly avoided the

use of the word) was composed of a demonstration of Pony Express

riding, an attack on the Deadwood Stage (which was the actual

Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage line coach used on the Deadwood

run), and a number of rodeo events including riding wild steers,

bucking broncos, calf roping, horse races, and shooting. Whenever he

could, Cody also employed authentic Western personages such as

scout John Nelson; Chief Gall, who participated in the defeat of

Custer at Little Big Horn; and later Sitting Bull, to make personal

appearances in the show. The grand finale usually consisted of a

spectacle incorporating buffalo, elk, deer, wild horses, and steers

stampeding with cowboys and Indians.

In 1884, the show played the Cotton Exposition in New Orleans,

where Cody acquired his greatest drawing card—sharpshooter Annie

Oakley, who was billed as ‘‘Little Sure Shot.’’ The following year,

Sitting Bull, the most famous chief of the Indian Wars, joined the

show. Ironically, Cody’s use of Sitting Bull and other Indians as

entertainers remains controversial to this day. To his critics, the

depictions of Indians attacking stagecoaches and settlers in a vast

arena served to perpetuate the image of the Indian as a dangerous

savage. On the other hand, he was one of the few whites willing to

employ Native Americans at the time, and he did play a role in taking

many of them off the reservation and providing them with a view of

the wider world beyond the American frontier.

Yet even as many Indians were touring the country with Buffalo

Bill’s Wild West Show, the Indian Wars were still continuing on the

frontier. Some of Cody’s Indians returned to help in the Army’s

peacemaking efforts, and Cody himself volunteered his services in

the last major Sioux uprising of 1890-91 as an ambassador to Sitting

Bull, who had returned from Canada to lend his presence as a spiritual

leader to his countrymen. This effort was personally called off by

President Benjamin Harrison, and Sitting Bull was shot by Indian

COFFEE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

546

police the next day while astride a show horse given to him by Cody.

According to historian Kevin Brownlow, the horse, trained to kneel at

the sound of gunfire while appearing in the Wild West Show,

proceeded to bow down while its famous rider was being shot. When

the Indians were ultimately defeated, Cody was able to free a number

of the prisoners to appear in his show the following season—a

dubious achievement, perhaps, but one that allowed them a measure

of freedom in comparison to confinement on a reservation.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show reached the peak of its populari-

ty in 1887 when Cody took his extravaganza to London to celebrate

Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. According to sources, one perform-

ance featured an attack on a Deadwood Stage driven by Buffalo Bill

himself with the Prince of Wales and other royal personages on board.

This performance was followed in 1889 with a full European tour,

beginning with a gala opening in Paris. It is perhaps this tour, along

with Ned Buntline’s Wild West novels, that have formed the basis for

European idealization of the romance of the Old West.

Returning to the United States in 1893, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

Show logged the most successful season in the history of outdoor

stadium shows. After that high water mark, however, the show began

to decline. Other competitors had entered the field as early as 1887

and Wild West shows began to proliferate by the 1890s. In 1902,

Cody’s partner, Ante Salisbury, died and the management of the show

was temporarily turned over to James Bailey of the Barnum and

Bailey Circus, who booked it for a European tour that lasted from

1902 to 1906. After Bailey’s death, the show was merged with rival

Pawnee Bill’s Far East and went on the road from 1909 to 1913,

before failing due to financial difficulties. Buffalo Bill kept the show

going with several other partners until his death in 1917, and the show

ended a year later.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show remains important today be-

cause it was perhaps the single most significant historical factor in the

creation of the romantic notion of the West that has formed the basis

for the countless books, dramatizations, and motion pictures that have

become part of the American fabric. Though the authenticity of

Cody’s depictions was somewhat debatable, they were nonetheless

based on his personal experiences on the frontier and were staged in

dramatic enough fashion to create an impact upon his audiences. The

show was additionally responsible for bringing Native Americans,

frontier animals, and Western cultural traditions to a world that had

never seen them close-up. Whether his show was truly responsible for

creating an awareness of the endangered frontier among its spectators

cannot be measured with accuracy, but it undoubtedly had some

impact. And certainly the romantic West that we still glorify today

remains the West of Buffalo Bill.

—Steve Hanson

F

URTHER READING:

Brownlow, Kevin. The War, The West, and the Wilderness. New

York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1979.

Cody, William F. An Autobiography of Buffalo Bill (Colonel W.F.

Cody). New York, Cosmopolitan Book Corporation, 1923.

———. The Business of Being Buffalo Bill: Selected Letters of

William F. Cody, 1879-1917. New York, Praeger, 1988.

Lamar, Howard R., editor. The Readers Encyclopedia of the Ameri-

can West. New York, Harper & Row, 1977.

Leonard, Elizabeth Jane. Buffalo Bill, King of the Old West. New

York, Library Publishers, 1955.

Cody, William F.

See Cody, Buffalo Bill, and his

Wild West Show

Coffee

A strong, stimulating beverage with a distinctive aroma and

complex flavor, coffee has been a popular drink for centuries. Brewed

by the infusion of hot water and ground, roast coffee beans, coffee is

enjoyed at any time of the day and night, though it is most associated

with a morning pick-me-up. Coffee’s primary active ingredient, the

stimulant caffeine, is mildly addictive but to date no serious medical

complications have been associated with its use. Local establishments

such as cafés, coffee houses, coffee bars, and diners attract millions of

customers worldwide. Specialty coffee shops serve dozens of varie-

ties, each identified by the geographic growing region and degree of

roast. Methods of preparation also vary widely, but in general coffee

is served hot, with or without the addition of milk or cream, and sugar

or other sweetener. Though coffee has always been popular, it wasn’t

until the 1980s that a number of specialty coffee retailers enhanced

the cachet of coffee by raising its price, differentiating varieties, and

associating the drink with a connoisseur’s lifestyle.

Coffee houses have been regarded as cultural meeting places

since the 17th century in western civilization, when artists, writers,

and political activists first started to meet and discuss topics of social

interest over a cup of this stimulating drink. The poet Baudelaire, in

A coffee shop sign in Seattle, Washington.

COFFEEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

547

Paris in the 1840s, described coffee as best served ‘‘black as night, hot

as hell, and sweet as love.’’ Coffee seems always to have been part of

the American landscape, as it was a common feature on the

chuckwagons of the prairie pioneers and cattle ranchers, and in the

break-rooms of companies and board rooms. Coffee is so popular in

diners and roadside eateries that it is served almost as often as water.

But for most of its history, coffee was just coffee, a commodity that

was not associated with brand name or image. All that changed

beginning in the 1980s, as the result of a convergence of two trends.

Americans looking for a socially-acceptable alternative to drug and

alcohol intake were well-served by a proliferation of retailers eager to

provide high-priced ‘‘gourmet’’ coffee to discriminating drinkers.

Specialty shops such as Starbucks in Seattle and Peet’s Coffee in

Berkeley have expanded to national chains whose popularity has

eclipsed that of national brands such as Maxwell House and Folgers,

which spread across America in the fifties. In addition, hundreds of

independent cafés and coffee houses were founded in every major

American city throughout the 1990s. In the Pacific Northwest—the

capital of coffee consumption in America—drive-up espresso shacks

line the roadsides, providing a variety of coffee drinks to commuters

willing to pay $3.50 for a 20-ounce Café Mocha with a double shot of

espresso. Even a small town like Snohomish, Washington, with a

population of only 8,000, boasts a dozen espresso shacks.

Percolated coffee, made by a process where coffee is boiled and

spilled over coffee grounds repeatedly, was very popular in the 1950s

but made coffee which tasted sour, bitter, and washed-out. It has

virtually been replaced by filtered or automatic drip coffee and the

more exotic ‘‘cafe espresso,’’ an Italian invention whereby hot water

is forced through densely packed coffee grounds resulting in very

dark, highly-concentrated coffee. Espresso is a popular favorite in

specialty coffee shops and in European cafes. These coffee houses

offer a more healthful daytime solution to social interaction than the

local bar, which centered around the drinking of alcoholic beverages.

The stimulating effects of coffee quite naturally encourage conversa-

tion and social discourse. Many coffee houses show artwork and host

local musicians; some feature newsstands or shelves of books encour-

aging patrons to browse at their leisure. Coffee shops are also found

around most college and university campuses.

The earliest recorded instances of coffee drinking and cultiva-

tion date back at least to the sixth century in Yemen, and coffee

houses were popular establishments throughout Arabia for centuries

before Europeans caught on, since it was forbidden to transport the

fertile seed of the coffee plant. There is botanical evidence that the

coffee plant actually originated in Africa, most likely in Kenya.

Centuries later, coffee plants were imported by French colonists to the

Caribbean and eventually to Latin America, and by the Dutch to Java

in Indonesia. Today coffee production is centered in tropical regions

throughout the world, with each region boasting distinctive kinds

of coffee.

There are two distinct varieties of the coffee plant: caffea

arabica, which comprises the majority of global production and grows

best at high elevations in equatorial regions; and caffea robusta,

discovered comparatively recently in Africa, which grows at some-

what lower elevations. The robusta bean is grown and harvested more

cheaply than arabica. It is used as a base for many commercial blends

even though the taste is reported to be poorer by connoisseurs. The

coffee bean, which is the seed of the coffee plant, varies widely in

flavor dependent on the region, soil and climactic conditions in which

it is grown. These flavors are locked inside, for the most part, and

must be developed by a roasting process during which the woody

structure of the bean is broken down and the aromatic oils are

released. The degree of roasting produces a large degree of variation

in how the final coffee beverage looks and tastes.

The principal active ingredient in coffee is caffeine, an alkaloid

compound which produces mildly addictive stimulation to the central

nervous system, and stimulation to a lesser degree of the digestive

system. The medical effects of drinking coffee vary depending on the

amount of caffeine in each serving, the tolerance which has been built

up from repeated use, and the form in which it is being ingested.

Coffee is often served in restaurants as a digestive stimulant, either

enhancing the appetite when served before a meal, such as at

breakfast, or as an aid to digestion when served, for example, as a

‘‘demi-tasse’’ (French for ‘‘half-a-cup’’) in restaurants after a fine

meal. Although American medical literature reports that up to three

cups of coffee may be drunk daily without any serious medical

effects, individual limits of consumption vary widely. Many people

drink five or six cups or more per day, while coffee consumption has

been restricted in cases where gastrointestinal complications and

other diagnoses may be aggravated by overstimulation. Though not

medically significant, many coffee users experience rapid heartbeat,

jumpiness, and irritation of the stomach due to excessive coffee

consumption. All of these side effects may seem worth it to a coffee

drinker who relies on the certain stimulating effects of multiple cups

of coffee. Withdrawal symptoms such as headaches occur when

coffee is taken out of the diet due to caffeine deprivation, but these

effects usually subside after a few days.

With all the concern about caffeine in coffee, it was a matter of

time before scientists found ways to remove caffeine while maintain-

ing coffee’s other more pleasurable characteristics such as taste and

aroma. The first successful attempt to remove the kick out of coffee

came at the end of the nineteenth century. Distillation and dehydra-

tion/reconstitution resulted in a coffee beverage with less than two

percent caffeine content. The caffeine-free powder was marketed

successfully as Sanka (from the French ‘‘sans caffeine’’ meaning

‘‘without caffeine’’). Since then, other processes of refinement have

succeeded in removing caffeine from coffee while preserving greater

and greater integrity of the coffee flavor complex. Most of these

decaffeination processes involve rinsing and treating coffee while

still in the bean stage. One process, which uses the chemical solvent

methylene chloride, has been judged by coffee experts to produce the

best tasting decaffeinated coffee since the chemical specifically

adheres to and dissolves the caffeine molecule while reacting with

little else. Popular outcry arose concerning the use of methylene

chloride in the late 1980s when a report was released indicating that it

could cause cancer in laboratory animals, but the claim was soundly

refuted when it was explained that virtually no trace of the element

ever remained in coffee after having been roasted and brewed. Use of

methlyne chloride was curtailed in the mid-1990s nonetheless, due to

a discovery that its production could have an adverse impact on the

earth’s ozone layer. Several other methods of decaffeination are

currently used, such as the Swiss water method and the supercritical

carbon dioxide process, to meet the growing consumer demand. The

vast majority of coffee drinkers, however, still prefer their coffee to

deliver a caffeine kick.

—Ethan Hay

F

URTHER READING:

Braun, Stephen. Buzz: The Science and Lore of Alcohol and Caffeine.

New York, Oxford University Press, 1996.

COHAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

548

Castle, Timothy James. The Perfect Cup: A Coffee Lover’s Guide to

Buying, Brewing, and Tasting. Reading, Massachusetts, Anis

Books, 1991.

Cherniske, Stephen. Caffeine Blues: Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers

of America’s #1 Drug. New York, Warner Books, 1998.

‘‘Coffee Madness.’’ Utne Reader. #66, November/December, 1994.

Davids, Kenneth. Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing, and Enjoying.

Santa Rosa, California, Cole Group, 1991.

Kummer, Corby. The Joy of Coffee: The Essential Guide to Buying,

Brewing, and Enjoying. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

Nile, Bo, and Veronica McNiff. The Big Cup: A Guide to New York’s

Coffee Culture. New York, City & Co., 1997.

Sewell, Ernestine P. How the Cimarron River Got Its Name and Other

Stories about Coffee. Plano, Texas, Republic of Texas Press, 1995.

Shapiro, Joel. The Book of Coffee and Tea: A Guide to the Apprecia-

tion of Fine Coffees, Teas, and Herbal Beverages. New York, St.

Martin’s Press, 1975.

Cohan, George M. (1878-1942)

The musical comedy stage of New York was home to George M.

Cohan, vaudeville song-and-dance man, playwright, manager, direc-

tor, producer, comic actor, and popular songwriter. During the first

two decades of the twentieth century, Cohan’s style of light comedic

drama dominated American theatre, and the lyrics he composed are

still remembered at the end of the twentieth century for their flag-

waving patriotism and exuberance. His hit song ‘‘Over There’’

embodied the wartime spirit of World War I, and ‘‘I’m a Yankee Doo-

dle Dandy’’ and ‘‘Grand Old Flag,’’ have been passed from genera-

tion to generation as popular tunes celebrating the American spirit.

Born on July 3 in Providence, Rhode Island, Cohan spent his

childhood as part of a vaudevillian family. Living the typical vaude-

ville life, Cohan and his sister traveled a circuit of stages, slept in

boarding houses and backstage while their parents performed, and

only occasionally attended school. At nine years old, Cohan became a

member of his parents’ act, reciting sentimental verse and performing

a ‘‘buck and wing dance.’’ By the age of eleven, he was writing

comedy material, and by thirteen he was writing songs and lyrics for

the act, which was now billed as The Four Cohans. In 1894, at the age

of sixteen, Cohan sold his first song, ‘‘Why Did Nellie Leave

Home?’’ to a sheet music publisher for twenty-five dollars.

In his late teens, Cohan began directing The Four Cohans, which

became a major attraction, earning up to a thousand dollars for a

week’s booking. Cohan wrote the songs and sketches that his family

performed, and had the starring roles. At twenty years of age,

managing the family’s business affairs, he was becoming a brazen,

young man, proud of his achievements. When he was twenty-one, he

married his first wife, Ethel Levey, a popular singing comedienne,

who then became the fifth Cohan in the act.

Within two years, seeking the fame, high salaries, and excite-

ment that life in New York theatre offered, Cohan centered his career

on the Broadway stage. His first Broadway production, The Gover-

nor’s Son, was a musical comedy that he wrote and in which he

performed in 1901. It was not the hit he hoped for, but after two more

attempts, Cohan enjoyed his first Broadway success with Little

Johnny Jones in 1904. In this musical, Cohan played the role of a

jockey and sang the lyrics that would live through the century: ‘‘I’m a

Yankee Doodle Dandy, / A Yankee Doodle, do or die; / A real live

nephew of my Uncle Sam’s / Born on the Fourth of July.’’ Among the

other hit songs from the play was ‘‘Give My Regards to Broadway.’’

In Cohan’s 1906 hit George Washington, Jr., he acted in a scene with

which he would be identified for life: he marched up and down the

stage carrying the American flag and singing ‘‘You’re a Grand Old

Flag,’’ the song that would become one of the most popular American

marching-band pieces of all time. Other of Cohan’s most famous

plays are Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway (1906), The Talk of New

York (1907), The Little Millionaire (1911), The Song and Dance Man

(1923), and Little Nelly Kelly (1923).

In 1917, when America entered World War I, Cohan was

inspired to compose ‘‘Over There,’’ the song that would become his

greatest hit. Americans coast to coast listened to the recording made

by popular singer Nora Bayes. Twenty-five years later, President

Franklin Delano Roosevelt awarded Cohan the Congressional Medal

of Honor for the patriotic spirit expressed in this war song.

Cohan achieved immortality through his songs and perform-

ances, and the 1942 film Yankee Doodle Dandy perpetuated his

image. In it, James Cagney portrayed Cohan with all of Cohan’s own

enthusiasm and brilliance. The film told the story of Cohan’s life and

included the hit songs that made him an American legend. The film

was playing in American theatres when Cohan died in 1942. President

Roosevelt wired his family that ‘‘a beloved figure is lost to our

national life.’’

—Sharon Brown

F

URTHER READING:

Buckner, Robert, and Patrick McGilligan. Yankee Doodle Dandy.

Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

Cohan, George Michael. Twenty Years on Broadway, and the Years It

Took to Get There: The True Story of a Trouper’s Life from the

Cradle to the ‘‘Closed Shop.’’ Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood

Press, 1971.

McCabe, John. George M. Cohan: The Man Who Owned Broadway.

Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1973.

Morehouse, Ward. George M. Cohan, Prince of the American Thea-

ter. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1972.

Colbert, Claudette (1903-1996)

The vivacious, Parisian-born Claudette Colbert was one of

America’s highest-paid and most popular actresses during her sixty-

year career on stage, films, and television. Her popular ‘‘screwball

comedies’’ enchanted movie audiences, and her classic performance

as the fleeing heiress in It Happened One Night (1934) earned her an

Academy Award. Although she continued to star in comedies, she

was also an Oscar-nominee for the dramatic film Since You Went

Away (1944). Her most talked-about scene was the milk bath in The

Sign of the Cross. In the 1950s she returned to Broadway, and, still

active in her eighties, starred in a television miniseries in 1987. She