Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

COLUMBOENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

559

many, notably Johnny Hodges, had used it over the years since Sidney

Bechet had mastered it, no other major jazz exponent had really

turned it into a popular jazz instrument on a regular basis. Trane

openly acknowledged Bechet’s influence on his soprano work. The

instrument, he said, allowed him to play in the higher registers in

which he heard music in his head. It also made his modal playing

accessible to a larger audience. My Favorite Things made the top 40

charts and began Coltrane’s career as a show business figure, com-

manding healthy fees and continuing to release soprano hits such

as ‘‘Greensleeves.’’

Meanwhile he grew interested in Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz

movement and released ‘‘The Invisible’’ with Don Cherry and Billy

Higgins and ‘‘India’’ in 1961. This movement into free jazz, predict-

ably, did not entail an abandonment of earlier styles. A Love Supreme

(1964) is a modal album and sold 250,000 copies. Such sales resulted

from the popular upsurge of interest in Eastern religions and mysti-

cism during the 1960s, and the album was bought by many who had

no idea of jazz but were attracted by the music’s connections with

mysticism. Even in the midst of his freest experiments, ‘‘Ascension’’

and ‘‘Expressions,’’ when he recorded with Freddie Hubbard, Archie

Shepp, Eric Dolphy, Pharoah Sanders, and Rashid Ali, Coltrane never

totally abandoned his love of harmony and melody. He once per-

formed with Thelonious Monk near the end of his life. When it was

over, Monk asked Trane when he was going to come back to playing

real music such as he had performed that day. Reputedly, Trane

responded that he had gone about as far as he could with experimental

music and missed harmonic jazz. He promised Monk that he would

return to the mainstream.

Whether he was comforting an old friend or speaking his heart,

nobody knows, but Expressions (1967) was his last recording and

included elements from all his periods. Coltrane died at the top of his

form when he passed away in 1967 at the age of 40. Though doctors

said he died of liver cancer, his friends claimed that he had simply

worn himself out. His creative flow had not dried up and it is

reasonable to assume that, had he lived, he would have continued to

explore new styles and techniques. As it was, he left a body of music

that defined and shaped the shifting jazz styles of the period, as well as

a reputation for difficult music and a dissipated lifestyle that con-

firmed the non-jazz lover’s worst—and inaccurate—fears about the

music and its decadent influence on American culture.

—Frank A. Salamone

F

URTHER READING:

Cole, Bill. John Coltrane. New York, Da Capo, 1993.

Kofsky, Frank. John Coltrane and the Jazz Revolution of the 1960s.

New York, Pathfinder Press, 1998.

Nisenson, Eric. Ascension: John Coltrane and His Quest. New York,

St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

Porter, Lewis. John Coltrane: His Life and Music. Ann Arbor,

University of Michigan Press, 1998.

Simpkins, Cuthbert Ormond. Coltrane: A Biography. New York,

Black Classic Press, 1988.

Strickland, Edward. ‘‘What Coltrane Wanted.’’ Atlantic Monthly.

December 1987, 100-102.

Thomas, J. C. Chasin’ the Train: The Music and Mystique of John

Coltrane. New York, Da Capo Press, 1988.

Woodleck, Carl, editor. The John Coltrane Companion: Four Dec-

ades of Commentary. New York, Schrimmer Books, 1998.

Columbo

Lieutenant Columbo, played by Peter Falk, remains the most

original, best-written detective in television history. Other shows

featuring private detectives (The Rockford Files) or policemen (Hill

Street Blues) may contain more tongue-in-cheek humor or exciting

action sequences, but when it comes to pure detection, brilliant

plotting, and intricate clues, Columbo remains unsurpassed. Its unique-

ness stems from the fact that it is one of the few ‘‘inverted’’ mysteries

in television history. While other mysteries like Murder, She Wrote

were whodunits, Columbo was a ‘‘how’s-he-gonna-get-caught?’’

Whodunit was obvious because the audience witnessed the murder

firsthand at the start of each episode—also making the show unique in

that the star, Falk, was completely missing for the first quarter hour of

most episodes. This inversion produced a more morally balanced

universe; while the murderer in another show might spend 90 percent

of its running time enjoying his freedom, only to be nabbed in the last

few scenes, in Columbo the murderer’s carefree lifestyle was short-

lived, being replaced by a sick, sweaty angst as the rumpled detective

moved closer and closer to the truth. The climatic twist at the end was

merely the final nail in the coffin. The show was consistently riveting

with no gunplay, no chase sequences, and virtually all dialogue. The

inverted mystery is not new, having been devised by R. Austin

Freeman for such books as The Singing Bone, but never has the form

been better utilized.

Columbo sprang from the fertile minds of Richard Levinson and

William Link, who met in junior high school and began writing

mysteries together. They finally sold some to magazines, then to

television, adapting one story they’d sold to Alfred Hitchcock’s

Mystery Magazine for television’s The Chevy Mystery Show. When

Bert Freed was selected to play the part of the detective in this

mystery, called ‘‘Enough Rope,’’ he became the first actor to play

Lieutenant Columbo. Levinson later said the detective’s fawning

manner came from Petrovich in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punish-

ment, and his humbleness came from G. K. Chesterton’s Father

Brown. Deciding to dabble in theater, Levinson and Link adapted this

story into the play Prescription: Murder, which opened in San

Francisco starring Joseph Cotton, Agnes Moorehead, and Thomas

Mitchell as Columbo. When made-for-TV movies became a popular

form, the writers opened up their stagebound story to make it more

cinematic, but they needed to cast a new actor as the detective because

Mitchell had died since the play’s closing. The authors wanted an

older actor, suggesting Lee J. Cobb and Bing Crosby, but they were

happy with Falk as the final choice once they saw his performance.

The film aired in 1968 with Gene Barry as the murderer, and the show

received excellent ratings and reviews. Three years later, when NBC

was developing the NBC Mystery Movie, which was designed to have

such series as McCloud and McMillan and Wife in rotation, the

network asked Levinson and Link for a Columbo pilot. The writers

thought that Prescription: Murder made a fine pilot, but the network

wanted another—perhaps to make sure this ‘‘inverted’’ form was

repeatable and sustainable—so ‘‘Ransom for a Dead Man’’ with Lee

Grant as the murderer became the official pilot for the series. These

two made-for-TV movies do not appear in syndication with the

COLUMBO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

560

series’ other forty-three episodes, though they frequently appear on

local stations.

NBC Mystery Movie premiered in September 1971, and the

talent the show attracted was phenomenal. That very first episode,

‘‘Murder by the Book,’’ was written by Steven Bochco (Hill Street

Blues, NYPD Blue) and was directed by Steven Spielberg. The series

also employed the directorial talents of Jonathan Demme, Ben

Gazzara, Norman Lloyd, Hy Averback, Boris Sagal, and Falk him-

self, among others. Acting talents such as Ray Milland, Patrick

McGoohan, John Cassavetes, Roddy McDowell, Laurence Harvey,

Martin Landau, Ida Lupino, Martin Sheen, and Janet Leigh contribut-

ed greatly to the series, though what made it a true classic was Falk’s

Emmy-winning portrayal of the rumpled detective. The raincoat, the

unseen wife, the dog named Dog, the ragtop Peugeot, the forgetful-

ness—much of this was in the writing, but Falk added a great deal and

made it all distinctly his own. Levinson said, ‘‘We put in a servile

quality, but Peter added the enormous politeness. He stuck in sirs and

ma’ams all over the place.’’ He said another of the lieutenant’s quirks

evolved from laziness on the writers’ part. When writing the play

Prescription: Murder, there was a scene that was too short, and

Columbo had already made his exit. ‘‘We were too lazy to retype the

scene, so we had him come back and say, ‘‘Oh, just one more thing.’’

On the show, the disheveled, disorganized quality invariably put the

murderers off their guard, and once their defenses were lowered,

Columbo moved in for the kill. Much of the fun came from the show’s

subtle subversive attack on the American class system, with a

working-class hero, totally out of his element, triumphing over the

conceited, effete, wealthy murderer finally done in by his or her

own hubris.

The final NBC episode aired in May 1978, when Falk tired of the

series. Ten years later, Falk returned to the role when ABC revived

Columbo, first in rotation and then as a series of specials, with at least

twenty new episodes airing throughout the 1990s. Levinson and Link

wrote other projects, and Falk played other roles, but as Levinson

once said, referring to himself and Link, ‘‘If we’re remembered for

anything, it may say Columbo on our gravestones.’’

—Bob Sullivan

F

URTHER READING:

Conquest, John. Trouble Is Their Business: Private Eyes in Fiction,

Film, and Television, 1927-1988. New York, Garland Publish-

ing, 1990.

Dawidziak, Mark. The Columbo Phile: A Casebook. New York, The

Mysterious Press, 1989.

De Andrea, William L. Encyclopedia Mysteriosa. New York, Pren-

tice Hall General Reference, 1994.

Levinson, Richard, and William Link. Stay Tuned: An Inside Look at

the Making of Prime-Time Television. New York, St. Martin’s

Press, 1981.

Columbo, Russ (1908-1934)

Russ Columbo was a popular romantic crooner of the 1920s and

early 1930s. Often referred to as ‘‘Radio’s Valentino,’’ Columbo was

so popular he was immortalized in a song of the day, ‘‘Crosby,

Columbo, and Vallee.’’ Born Ruggerio de Rudolpho Columbo, he

became a concert violinist, vocalist, songwriter, and bandleader. He

wrote many popular songs, mainly with partner Con Conrad. One of

his biggest hits also became his theme song, ‘‘You Call It Madness

(But I Call it Love).’’

Columbo appeared in a few films and had just signed with

Universal Pictures for a series of musicals when he was tragically

killed. While looking at the gun collection of friend Lansing Brown,

one of the guns discharged, hitting Columbo in the eye. He died a

short time later.

—Jill Gregg

F

URTHER READING:

Hemming, Roy, and David Hajdu. Discovering Great Singers of

Classic Pop. New York, Newmarket Press, 1991.

Parish, James Robert, and Michael R. Pitts. Hollywood Songsters: A

Biographical Dictionary. New York, Garland Publishing, 1991.

Comic Books

Comic books are an essential representation of twentieth-centu-

ry American popular culture. They have entertained readers since the

time of the Great Depression, indulging their audience in imaginary

worlds born of childhood fantasies. Their function within American

culture has been therapeutic, explanatory, and commercial. By ap-

pealing to the tastes of adolescents and incorporating real-world

concerns into fantasy narratives, comic books have offered their

impressionable readers a means for developing self-identification

within the context of American popular culture. In the process, they

have worked ultimately to integrate young people into an expanding

consumer society, wherein fantasy and reality seem increasingly linked.

With their consistent presence on the fringes of the immense

American entertainment industry, comic books have historically been

a filter and repository for values communicated to and from below.

Fashioned for a mostly adolescent audience by individuals often little

older than their readers, comic books have not been obliged to meet

the critical and aesthetic criteria of respectability reserved for works

aimed at older consumers (including newspaper comic strips). Nei-

ther have comic books generally been subject to the sort of intrinsic

censorship affecting the production of expensive advertising and

investment-driven entertainment projects. Consequently, comic books

have often indulged in outrageous situations and images more fantas-

tic, grotesque, and absurd than those found elsewhere in American

mass culture. These delightfully twisted qualities have always been

central to the comic book’s appeal.

Comic books first emerged as a discrete entertainment medium

in 1933, when two sales employees at the Eastern Color Printing

Company, Max C. Gaines and Harry I. Wildenberg, launched an

entrepreneurial venture whereby they packaged, reduced and reprint-

ed newspaper comic strips into tabloid-sized magazines to be sold to

manufacturers who could use them as advertising premiums and

giveaways. These proved so successful that Gaines decided to put a

ten-cent price tag on the comic magazines and distribute them directly

to newsstands. The first of these was Famous Funnies, printed by

Eastern Color and distributed by Dell Publications. Other publishers

soon entered the emerging comic-book field with similar products. In

1935 a pulp-magazine writer named Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson

began publishing the first comic books to feature original material. A

COMIC BOOKSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

561

few years later, his company was bought out by executives of the

Independent News Company who expanded the operation’s line and

circulation. In 1937 they launched Detective Comics, the first comic

book to feature adventure stories derived more from pulp magazines

and ‘‘B’’ movies than from newspaper ‘‘funnies.’’ The company later

became known by the logo DC—the initials of its flagship title.

By 1938 an embryonic comic-book industry existed, comprising

a half-dozen or so publishers supplied by several comic-art studios all

based in the New York City area. That same year, the industry found

its first original comic-book ‘‘star’’ in Superman. The creation of two

teenagers named Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Superman’s adven-

tures pointed to the fantastic potential of comic books. Because their

content was limited only by the imagination and skill of the writers

and artists who crafted them, comic books could deal in flights of

fantasy unworkable in other visual entertainment media. As an instant

commercial success, Superman prompted a succession of costumed

superhero competitors who vied for the nickels and dimes of not-too-

discerning young consumers. Comic-book characters like DC’s Batman,

Wonder Woman, and Green Lantern; Marvel Comics’ Captain America,

and Fawcett Publications’ Captain Marvel all defined what comic-

book historians and collectors term the ‘‘Golden Age’’ of comic

books. Although comic books would later embrace a variety of

genres, including war, western, romance, crime, horror, and humor,

they have always been most closely identified with the costumed

superheroes who made the medium a viable entertainment industry.

Creating most of these early comic books was a coterie that was

overwhelmingly urban, under-thirty, lower middle class, and male.

They initially conceived Depression-era stories that aligned superheroes

on the side of the poor and the powerless against a conspiracy of

corrupt political bosses, greedy stockbrokers, and foreign tyrants. As

the nation drifted towards World War II, comic books became

increasingly preoccupied with the threat posed by the Axis powers.

Some pointed to the danger as early as 1939—well ahead of the rest of

the nation. Throughout the war, comic books generally urged a united

national front and endorsed patriotic slogans derived from official

U.S. war objectives. Many eviscerated the enemy in malicious and

often, in the case of the Japanese, racist stereotypes that played to the

emotions and fears of their wartime audience, which included serv-

icemen as well as children. At least a few publishers, most notably DC

Comics, also used the occasion of the war against fascism to call for

racial and ethnic tolerance on the American home front.

The war years were a boom time for the comic-book industry. It

was not uncommon for a single monthly issue to sell in excess of

500,000 copies. The most popular comic books featuring Superman,

Batman, Captain Marvel, and the Walt Disney cartoon characters

often sold over one million copies per issue. When the war ended,

however, sales of most superhero comic books plummeted and the

industry lost its unity of purpose. Some publishers, like Archie

Comics, carved out a niche for themselves with innocuous humor

titles that enjoyed a certain timeless appeal for young children. But as

other publishers scrambled for new ways to recapture the interest of

adolescent and adult readers, some turned to formulas of an increas-

ingly controversial nature. Many began to indulge their audience in a

seedy underworld of sex, crime, and violence of a sort rarely seen in

other visual entertainment. These comic books earned the industry

legions of new readers and critics alike. Young consumers seemed to

have a disturbing taste for comic books like Crime Does Not Pay that

dramatized—or, as many would charge, glorified—in graphic detail

the violent lives of criminals and the degradation of the American

dream. Parents, educators, professionals, and politicians reacted to

these comic books with remarkable outrage. Police organizations,

civic groups, and women’s clubs launched a grassroots campaign at

the local and state levels to curb or ban the sale and distribution of

objectionable comic books. Only a few years after the end of its

participation in a world war, the comic-book industry found itself

engaged in a new conflict—a cultural war for the hearts and minds of

the postwar generation.

As the Cold War intensified, comic-book makers responded by

addressing national concerns at home and abroad, while hoping to

improve their public image in the process. Romance comic books

instructed young females on the vital qualities of domesticity and

became, for a time in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the industry’s

top-selling genre. War comic books produced during the Korean War

underscored the domestic and global threat of Communism. But, as

part of the industry’s trend toward more realistic stories, many of

these also illustrated the ambivalence and frustration of confronting

an elusive enemy in a war waged for lofty ideals with limited means.

Neither the subject matter of romance nor war could, in any case,

deflect the mounting public criticism directed at comic books. Through-

out the postwar decade comic-book makers found themselves con-

fronted by a curious alliance of liberals and conservatives who feared

that forms of mass culture were undermining—even replacing—

parents, teachers, and religious leaders as the source of moral authori-

ty in children’s lives. As young people acquired an unprecedented

degree of purchasing power in the booming economy, they had more

money to spend on comic books. This in turn led to more comic book

publishers trying to attract young consumers with increasingly sensa-

tional material. Thus, in an irony of postwar culture, the national

affluence so celebrated by the defenders of American ideals became

perhaps the most important factor accounting for the existence and

character of the most controversial comic books.

The most outrageous consequence of the keen competition

among publishers was the proliferation of horror comic books.

Popular and widely imitated titles like EC Comics’ Tales From the

Crypt celebrated murder, gore, and the disintegration of the American

family with a willful abandon that raised serious questions about the

increasing freedom and power of mass culture. At the vanguard of the

rejuvenated forces aligned against comic books was a psychiatrist and

self-proclaimed expert on child behavior named Dr. Fredric Wertham.

His 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent set forth a litany of charges

against comic books, the most shocking and controversial being that

they contributed to juvenile delinquency. Such allegations led to a

1954 U.S. Senate investigation into the comic-book industry. Comic-

book publishers surrendered to the criticism by publicly adopting an

extremely restrictive self-censoring code of standards enforced by an

office called the Comics Code Authority. By forbidding much of what

had made comic books appealing to adolescents and young adults, the

Comics Code effectively placed comic books on a childlike level. At a

time when publishers faced stiff competition from television, and

rock’n’roll emerged as the new preeminent expression of rebellious

youth culture, the Code-approved comic books lost readers by the score.

By the start of the 1960s the industry showed signs of recovery.

DC Comics led the resurgence by reviving and revamping some of its

popular superheroes from the 1940s including the Flash, the Green

Lantern, and the Justice League of America. These characters marked

the industry’s return to the superhero characters that had made it so

successful in the beginning. But the pristine, controlled, and rather

stiff DC superheroes proved vulnerable to the challenge posed by

Marvel Comics. Under the editorial direction of Stan Lee, in collabo-

ration with artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Marvel launched a

COMICS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

562

series of new titles featuring superheroes ‘‘flawed’’ with undesirable

but endearing human foibles like confusion, insecurity, and aliena-

tion. Marvel superheroes like the Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk,

Spider-Man, the Silver Surfer, and the X-Men found a large and loyal

audience among children, adolescents, and even adults drawn to the

anti-establishment and clever mythical qualities of the Marvel

comic books.

During the late 1960s a new wave of ‘‘underground’’ comic

books, sometimes called ‘‘comix,’’ emerged as an alternative to the

mainstream epitomized by DC and Marvel. These underground

comics flourished despite severely limited exposure, and were usual-

ly confined to counterculture audiences. With unrestrained subject

matter that celebrated drugs, violence, and especially sex, these

publications shared more in common with the avant-garde movement

and adult magazines than they did with most people’s conception of

comic books. Artists like Robert Crumb, Rick Griffin, and Art

Spiegelman later found some mainstream success and fame (with

Fritz the Cat, Zippy the Pinhead, and Maus, respectively) after getting

their start in underground comix. And independent comic books

inspired by the underground comix movement continue to enjoy some

popularity and sales through comic-book stores throughout the 1980s

and 1990s.

Since the 1960s, however, the comic-book industry has been

dominated by the superheroes of publishing giants Marvel and DC.

Successive generations of comic-book creators have come to the

industry as fans, evincing a genuine affection and respect for comic

books that was uncommon among their predecessors, most of whom

aspired to write or illustrate for other media. During the late 1960s and

early 1970s these creators used comic books to comment upon the

most pressing concerns of their generation. Consequently, a number

of comic books like The Amazing Spider-Man, The Green Lantern,

and Captain America posed a moderate challenge to the ‘‘Establish-

ment’’ and took up such liberal political causes as the civil rights

movement, feminism, and opposition to the Vietnam War.

Aware of the country’s changing political mood, publishers in

1971 liberalized the Comics Code, making it easier for comic books

to reflect contemporary society. Comic-book makers initially took

advantage of this new creative latitude to launch a number of

ambitious and often self-indulgent efforts to advance mainstream

comic books as a literary art form. While many of these new 1970s

comic books were quite innovative, nearly all of them failed commer-

cially. Nevertheless, they indicated the increasing willingness of the

major publishers to encourage writers and artists to experiment with

new ideas and concepts.

As the 1970s drew to a close, the comic-book industry faced

some serious distribution problems. Traditional retail outlets like

newsstands and ‘‘mom-and-pop’’ stores either disappeared or refused

to stock comic books because of their low profit potential. Since the

early 1980s, however, comic books have been distributed and sold

increasingly through specialty comic-book stores. Publishers earned

greater profits than ever before by raising the cost of their comic

books, distributing them to these outlets on a non-returnable basis,

and targeting the loyal fan audience over casual mainstream readers.

The most popular comic books of the past few decades indicate

the extent to which alienation has become the preeminent theme in

this medium of youth culture. In the early 1980s, a young writer-artist

named Frank Miller brought his highly individualistic style to Mar-

vel’s Daredevil, the Man without Fear and converted it from a

second-tier title to one of the most innovative and popular in the field.

Miller’s explorations of the darker qualities that make a superhero

inspired others to delve into the disturbing psychological motivations

of the costumed vigilantes who had populated comic books since the

beginning. Miller’s most celebrated revisionism in this vein came in

the 1986 ‘‘graphic novel’’ Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Such

revisionism in fact became the most common formula of recent comic

books. Besides such stalwarts as Spider-Man and Batman, the best-

selling superheroes of the 1980s and 1990s included the X-Men, the

Punisher, the Ghost Rider, and Spawn. All featured brooding, obses-

sive, alienated antiheroes prone to outbursts of terrifying violence.

This blurring of the lines between what makes a hero and a villain in

comic books testifies to the cynicism about heroes generally in

contemporary popular culture and to the eagerness of comic-book

publishers to tap into the adolescent disorientation and anxieties that

have, to some degree, always determined the appeal of comic-

book fantasies.

Although comic books remained popular and profitable throughout

the 1990s, the major publishers faced some formidable crises. The

most obvious of these was the shrinking audience for their product.

Comic-book sales peaked in the early 1990s before falling sharply in

the middle years of the decade. Declining fan interest was, in part, a

backlash against the major publishers’ increasing tendency to issue

drawn-out ‘‘cross-over’’ series that compelled readers to buy multi-

ple issues of different titles in order to make sense of convoluted plots.

Many other jaded buyers were undoubtedly priced out of the comic-

book market by cover prices commonly over $2.50. Special ‘‘collec-

tor’s editions’’ and graphic novels frequently sold at prices over

$5.00. Most troubling for comic-book makers, however, is the threat

that their product may become irrelevant in an increasingly crowded

entertainment industry encompassing cable TV, video games, and

internet pastimes aimed directly at the youth market. Retaining and

building their audience in this context is a serious challenge that will

preoccupy creators and publishers as the comic-book industry enters

the twenty-first century.

—Bradford W. Wright

F

URTHER READING:

Benton, Mike. The Comic Book in America: An Illustrated History.

Dallas, Taylor Publishing, 1993.

Daniels, Les. DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic

Book Heroes. Boston, Little, Brown, 1995.

———. Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest

Comics. New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1991.

Goulart, Ron. Over Fifty Years of American Comic Books.

Lincolnwood, Illinois, Mallard Press, 1991.

Harvey, Robert C. The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History.

Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

Jacobs, Will, and Gerard Jones. The Comic Book Heroes. Rocklin,

California, Prima Publishing, 1998.

Savage, William W., Jr. Comic Books and America, 1945-1954.

Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1990.

Comics

Comic strips and comic books have been two mainstays of

American culture during the entire twentieth century. Comic strips

COMICSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

563

rapidly became a defining feature of modern American culture after

their introduction to newspapers across the nation in the first ten years

of the twentieth century. Likewise comic books captured the imagina-

tion of many Americans in the late 1930s and early 1940s, particularly

after the appearance of costumed heroes such as Superman, Batman,

and Captain Marvel. From the beginning, comics produced distinct,

easily recognized characters whose images could be licensed for other

uses. Comic characters united entertainment and commerce in ways

that became ubiquitous in American culture.

Although the origin of comic strips is generally traced to the first

appearance of the Yellow Kid—so named because the printers chose

his nightshirt to experiment with yellow ink—in the New York World

in 1895, the antecedents of comics are somewhat more complex.

When the World began a Sunday humor supplement in 1889, it did so

to attract the audience of American illustrated humor magazines such

as Puck, Judge, and Life. These magazines had drawn on European

traditions of broadsheets, satirical prints, comic albums, and journals

such as Fliegende Blätter, Charivari, and Punch to create a sharp-

edged American style of satirical visual humor. The appearance of the

Yellow Kid—in the Hogan’s Alley series—was not a particularly

startling moment but rather grew out of an international and local

tradition of illustrated humor. What set the Yellow Kid apart from

previous versions of the city urchin genre of illustrated humor were

his distinct features and regular appearance in large-scale comic panels.

In October 1896 William Randolph Hearst launched a humor

supplement to the Sunday edition of his New York Journal and

contracted the services of Richard Outcault, the Yellow Kid’s creator.

In addition, the Journal employed Rudolph Dirks and Frederick

Opper. Although the Yellow Kid established the importance in comic

art of a regularly appearing, distinctive character, Outcault did not use

with any regularity two other important features of modern comics—

sequential panels and word balloons, both of which had been used for

centuries in European and American graphic art. Dirks and Opper

introduced and developed these features in the pages of the Journal.

Between December 1897 and March 1901 Dirks’s Katzenjammer

Kids and Opper’s Happy Hooligan brought together the essential

features of modern comics: a regular, distinctive character or cast of

characters appearing in a mass medium, the use of sequential panels

to establish narrative, and the use of word balloons to convey

dialogue. More often than not Dirks’s and Opper’s strips used twelve

panels on a broadsheet page to deliver a gag.

Between 1900-03 newspaper owners and syndicates licensed

comic strips and supplements to newspapers across the country. This

expansion was tied to broader developments in American culture

including the establishment of national markets and ongoing develop-

ments in communication and transportation. Comic supplements

were circulation builders for newspapers, and by 1908 some 75

percent of newspapers with Sunday editions had a comics supple-

ment. For most newspapers the introduction of a comic supplement

saw a rise in sales. The development of daily comic strips, which

started with Bud Fischer’s Mutt and Jeff, first published in November

1907 in the San Francisco Chronicle, added another dimension to the

medium. In 1908 only five papers ran daily comic strips; five years

later at least ninety-four papers across the country ran daily strips. By

1913 newspapers had also begun to group their daily strips on a single

page. In a relatively short space of time comic strips moved from

being something new to being a cultural artifact. Comic Strips and

Consumer Culture, 1890-1945 quotes surveys showing that by 1924

at least 55 percent and as high as 82 percent of all children regularly

read comic strips. Likewise it showed that surveys by George Gallup

and others in the 1930s revealed that the mean average adult readership

of comic strips was 75 percent.

The daily comic strip’s four or five panels and black-and-white

format as opposed to the Sunday comics’ twelve color panels was the

first of many thematic and aesthetic innovations that fed the populari-

ty of strips. An important development in this process was the

blossoming of the continuity strip. Comics historian Robert Harvey

has argued that Joseph Patterson, the proprietor of the Chicago

Tribune and the New York Daily News, was instrumental in establish-

ing continuing story lines in comic strips through his development

and promotion of Sidney Smith’s The Gumps, a comic strip equiva-

lent of a soap opera with more than a hint of satire. The continuity

strip gave rise to adventure strips such as Wash Tubbs and Little

Orphan Annie, which in turn led to the emergence of science fiction

strips like Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. Even gag strips such as the

working girl strip Winnie Winkle adopted continuous story lines for

extended periods. The continuity strips led to comic art styles less

caricatured in appearance, which for want of a better expression

might be dubbed realistic strips, although the story content remained

fanciful. No one style of strip ever came to dominate the comics

pages, where gags strips, adventure strips, and realistic strips still

appear side by side.

From the start, the existence of distinctive characters in comics

had offered commercial possibilities beyond the pages of newspa-

pers. The image of the Yellow Kid was used to sell cigars, crackers,

and ladies’ fans, to name but a few of his appearances. Theater

producer Gus Hill staged a musical around the Kid in 1898 and

continued to produce comic-strip-themed musicals into the 1920s.

Doll manufacturers likewise produced comic strip character dolls.

Buster Brown gave his name to shoes, clothing, and a host of other

products including pianos and bread. The Yellow Kid’s adventures

had been reprinted in book form as early as 1897, and throughout the

first two decades of the twentieth century publishers such as Cupples

and Leon, and F. A. Stokes issued book compilations of popular

comic strips. In the early 1930s the commercial dimensions of comic

strips were expanded further when advertising executives realized

that the mass readership of strips meant that the art form could be used

in advertising to draw consumers to a product through entertainment.

In 1933, following this strategy, the Eastern Color Printing Company

sold a number of companies on the idea of reprinting comic strips in

‘‘books’’ and giving them away as advertising premiums.

After producing several of these advertising premium comic

books, Eastern published Famous Funnies in 1934, a sixty-four-page

comic book of reprinted strips priced at ten cents. Although the

company lost money on the first issue, it soon showed a profit by

selling advertising space in the comic book. Pulp writer Major

Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson saw an opportunity and joined the

fledgling industry with his all-original New Fun comic book in

February 1935. Wheeler-Nicholson’s limited financial resources ne-

cessitated a partnership with his distributor, the Independent News

Company, run by Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz, and the three

formed a partnership to launch Detective Comics in 1937. By 1938

Donenfeld and Liebowitz had eased Wheeler-Nicholson out of the

company. Shortly thereafter the two decided to publish a new title,

Action Comics, and obtained a strip for the first issue that M. C.

Gaines at the McClure Syndicate had rejected. Superman by Jerry

Siegel and Joe Shuster appeared on the cover of the first issue dated

June 1938. The initial print run was two hundred thousand copies. By

1941, Action Comics sold on average nine hundred thousand copies.

COMICS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

564

The company followed this success with the first appearance of

Batman in Detective Comics in May 1939.

The success of Superman and DC Comics, as the company was

now known, led other comic book companies to introduce costumed

heroes in the late 1930s and early 1940s including All American’s

(DC’s sister company) Wonder Woman and The Flash; Timely’s

(later Marvel) Captain America, the Human Torch, and the Submari-

ner; and Fawcett’s Captain Marvel. Comic book sales increased

dramatically and, according to Coulton Waugh, by 1942 12.5 million

were sold monthly. Historians such as Ron Goulart have attributed the

boom in superhero comic books to Depression-era searches for strong

leadership and quick solutions, and the cultural and social disruption

brought on by World War II. Moreover, comic books often served as a

symbol of America for servicemen overseas who read and amassed

them in large numbers.

America’s entry into the war also derailed a campaign against

comics begun by Sterling North, the literary editor of the Chicago

Daily News. In 1947 the sales of comic books reached sixty million a

month, and they seemed beyond attempts at censorship and curtailing

their spread. But in 1948 a New York psychiatrist, Fredric Wertham,

began a campaign that led eventually to a Senate investigation on the

nature of comic books and the industry’s establishing a Comics Code

in a successful attempt to avoid formal regulation through self-

censorship. Wertham’s 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent was the

culmination of his attempts to mobilize public sentiment against the

danger that he believed comic books posed to children’s mental

health. Wertham’s ideas were picked up by the Senate Subcommittee

on Juvenile Delinquency and its prime mover Senator Estes Kefauver. A

prime target of the subcommittee’s hearings was William M. Gaines,

the publisher of EC Comics, which had begun a line of horror comics

in 1950. Wertham’s attack and the introduction of the Comics Code

are often blamed for the demise of a ‘‘Golden Age’’ of comics, but

historian Amy Nyberg argues that only EC suffered directly, and

other factors such as changes in distribution and the impact of

television account for the downturn in comic book publishing.

Whatever the impact of Wertham, the comic book industry

shrugged it off relatively quickly. In 1956 DC relaunched its character

The Flash, which began a resurrection of superhero comic books. In

1960 DC published the Justice League of America, featuring a team of

superheroes. According to Les Daniels, the good sales of this book

prompted DC’s competitor to develop its own team of heroes, and in

1961 Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four appeared under the

Marvel imprint. The resulting boom in superhero comics, which saw

the debut of Spiderman and the Uncanny X-Men, is referred to by fans

as the Silver Age of comics. In the late 1950s and 1960s these fans

were particularly important in shaping the direction of comic books

and comics history. These fans were interested in comic art and story

construction rather than simply the entertainment value of the comic

books. That many of these fans were young adults had important

ramifications for the future direction of comic books. Likewise, their

focus on superheroes meant that these comic books have been

accorded the most attention, and books from publishers such as

Harvey, Dell, and Archie Comics figure little in many discussions of

comic book history because their content is held to be insignificant, at

least to young adults.

Perhaps the first publisher to recognize that comic books direct-

ed specifically at an older audience would sell was William M.

Gaines. When Wertham’s campaign put an end to his horror line of

comics, Gaines focused his attention on converting the satirical comic

book Mad into a magazine. Mad’s parodies of American culture

influenced many young would-be artists. In the late 1960s a number

of these artists, including Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, and Gilbert

Shelton, began publishing underground comics, or comix, which, as

the x designated, transgressed every notion of social normality.

Nonetheless, the artists demonstrated a close familiarity with the

graphic and narrative conventions of comic art. Discussing these

comix, Joseph Witek has suggested that they should be seen as part of

the mainstream of American comic history not least of all because

comix helped transform comic book content and the structure of

the industry.

A major shift in the industry occurred in the late 1970s and early

1980s when entrepreneurs following the example of the undergrounds

set up specialist comic shops, comic book distribution companies,

and their own comic book publishing companies in which artists

retained ownership of their characters. These changes led to more

adult-oriented comics at the smaller companies and at the two

industry giants, DC and Marvel, which between them accounted for

about 75 percent of the market in 1993. DC and Marvel also

responded to changes in the industry by giving their artists more

leeway on certain projects and a share in profits from characters they

created. These changes took place during a boom time for the industry

with the trade paper Comic Buyer’s Guide estimating increases in

comic book sales from approximately $125 million in 1986 to $400

million in 1992.

This comic book boom was related to the synergies created by

the media corporations that owned the major comic book companies.

DC had been acquired by Warner in the 1960s for its licensing

potential. In 1989 Warner’s Batman movie heated up the market for

comic books and comic-book-related merchandise. DC, Marvel, the

comic book stores, and distributors promoted comics as collectibles,

and many people bought comics as an investment. When the

collectibility bubble burst in the mid 1990s the industry encountered a

downturn in which Marvel wound up bankrupt. Marvel’s difficulties

point to the necessity of large comic book companies diversifying

their characters appearances along the lines of the DC-Warner en-

deavor. On August 29, 1998, the Los Angeles Times reported in some

detail the frustrations Marvel had experienced over thirteen years in

trying to bring Spiderman to the screen.

As the century draws to a close the art form remains strong in

both its comic strip and comic book incarnations. The development of

the Internet-based World Wide Web has seen the art delivered in a

new fashion where strips can be read and related merchandise ordered

on-line. At the close of the twentieth century, then, the essential

feature of comics remains its distinctive characters who unite enter-

tainment and commerce.

—Ian Gordon

F

URTHER READING:

Barrier, Michael, and Martin Williams. A Smithsonian Book of

Comic-Book Comics. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution

Press, 1981.

Blackbeard, Bill, and Martin Williams. The Smithsonian Collection

of Newspaper Comics. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution

Press, 1977.

Daniels, Les. Comix: A History of Comic Books in America. New

York, Outerbridge & Dienstfrey, 1971.

———. DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic

Book Heroes. Boston, Bulfinch Press, 1995.

COMICS CODE AUTHORITYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

565

———. Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest

Comics. New York, Abrams, 1991.

Gordon, Ian. Comic Strips and Consumer Culture, 1890-1945. Wash-

ington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Goulart, Ron. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books. Chicago,

Publications International Limited, 1991.

Harvey, Robert. The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History.

Jackson, Mississippi, University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Krause Publications. Comic Buyer’s Guide 1993 Annual. Iola, Wis-

consin, Krause Publications, 1993.

Marschall, Richard. America’s Great Comic Strip Artists. New York,

Abbeville Press, 1989.

McAllister, Matthew Paul. ‘‘Cultural Argument and Organizational

Constraint in the Comic Book Industry.’’ Journal of Communica-

tion. Vol. 40, 1990, 55-71.

Nyberg, Amy Kiste. Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics

Code. Jackson, Mississippi, University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

Sabin, Roger. Adult Comics: An Introduction. New York,

Routledge, 1993.

Waugh, Coulton. The Comics. Jackson, Mississippi, University Press

of Mississippi, 1990, [1947].

Wertham, Fredric. Seduction of the Innocent. New York, Holt,

Rinehart and Winston, 1954.

Witek, Joseph. Comic Books as History: The Narrative Art of Jack

Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar. Jackson, Mississip-

pi, University Press of Mississippi, 1989.

Comics Code Authority

When the Comics Code was drafted in 1954, it was touted by its

creators as ‘‘the most stringent code in existence for any communica-

tions media.’’ It certainly created a fervor, and sparked heated debate

about the role of comic books and what they could and should do. The

Comics Code Authority, however, was quick to diminish as a

censoring body, challenge after challenge reducing it to relative

powerlessness. Still, the Code, along with the events leading up to it,

had made its impact, not only changing the direction and aesthetics of

American comic books, but also affecting this artistic form interna-

tionally. Conventions were shaped, as artists endeavored to tell their

stories within the Code’s restrictions. Meanwhile, working outside of

the Code, some artists took special care to flout such circumscription.

Although many factors may be considered in the establishment

of the Code, the most widely discussed has been psychiatrist Frederic

Wertham’s book, Seduction of the Innocent, which, in a scathing

attack on comic books, claimed that reading comics could lead to

juvenile delinquency. The book reproduced isolated panels from

several comics and argued that such scenes had a negative impact on

the psychology of children. Although some psychologists argued

against Wertham’s claims, the book was generally well received,

becoming a best-seller and creating a furor over the supposed

insidiousness of the comic book industry. The release of the book was

followed by hearings—commonly referred to as the Kefauver Hear-

ings after presiding senator Estes Kefauver—before the Senate sub-

committee on delinquency. Called to testify, Wertham continued his

attack on comic books, concluding ‘‘I think Hitler was a beginner

compared to the comic book industry.’’ William Gaines, publisher of

the much-maligned EC line of comics, argued that these comics were

not intended for young children and should not be subjected to

protective censorship. Still he found himself forced into a defense not

of comics as an expressive art form, but of what constituted ‘‘good

taste’’ in a horror comic.

After all was said and done, however, it was not from the outside

that the code was imposed, but rather from within the industry itself.

The Comic Magazine Association of America(CMAA) was formed

on October 26, 1954 by a majority of publishers, in an effort to head

off more controversy and to resuscitate declining sales figures. The

CMAA served as a self-censoring body, creating a restrictive code

forbidding much violence and sexual content as well as anti-authori-

tarian sentiment, and even limiting the use of specific words like

‘‘crime,’’ ‘‘terror,’’ or ‘‘horror’’ on comic book covers. Publishers

were now obliged to submit their comics for review by the Comics

Code Authority (CCA). Approved magazines were granted the cover

seal stating, ‘‘Approved by the Comics Code Authority.’’ Publishers

that failed to meet Code restrictions or that declined to have their

books reviewed by the CCA found their distribution cut off as

retailers declined to carry unapproved books. Such publishers eventu-

ally either submitted to the Code or went out of business. Notably,

Wertham had been in favor of restrictions that would keep certain

comics out of the hands of children, but he was troubled by what he

saw in Code-approved books, which he often found no less harmful

than the pre-Code comics.

Two companies, Dell and Gilberton, already regarded as pub-

lishers of wholesome comics such as the Disney and Classics Illus-

trated titles, remained exempt from the Code. Other publishers

worked around the Code. Some resorted to publishing comics in

magazine format to avoid restrictions. Given the virtual elimination

of crime and horror comics, several publishers began to place more

emphasis on their superhero books, in which the violence was bigger

than life and far from the graphically realistic portrayals in crime and

horror comics. It was during these ensuing years that superheroes

came to dominate the form and that DC and Marvel Comics came to

command the marketplace.

In the 1960s a very different response to the Code manifested

itself in the form of underground comics. These independently-

produced comic books included graphic depictions of sex, violence,

drug use—in short, anything that the code prohibited. Moreover,

these comics often paid tribute to pre-Code books and raged against

the very censoring agents that had led to their demise.

The first overt challenge to the Code came from Marvel Comics

in 1971. Although the Code explicitly prohibited mention of drugs,

writer/editor-in-chief Stan Lee, at the request of the Department of

Health Education and Welfare, produced a three-issue anti-drug story

line in Amazing Spider-Man. Despite being released without the

code, these comics were distributed and sold wonderfully, aided by

national press. It was with this publication that the Code finally

changed, loosening up slightly on its restrictions regarding drugs and

clothing to reflect a change in times. Still, most of the restrictions

remained largely intact.

The power of the CCA was still further reduced with the rise of

direct distribution. Shops devoted to selling only comic books, which

received their comics directly from publishers or, later, comic dis-

tributors, rather than general news distributors began to spring up

during the 1970s. With this new system, the vigilance against non-

Code books was bypassed. The new marketplace allowed major

publishers to experiment with comics geared towards an adult

COMING OUT ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

566

readership, and allowed more adventurous small publishers to distrib-

ute their wares. The way was paved for major ‘‘independent’’

publishers, like Image and Dark Horse, who refused to submit to the

CCA’s restrictions.

Although the CCA has but a shadow of its former power over the

industry, and although the Code itself has been criticized—even from

within the CMAA—as an ineffectual dinosaur, there can be no

question of its impact. The comics industry, both economically and

aesthetically, owes a great deal to the Comics Code Authority, having

been shaped variously by accommodation and antagonism.

—Marc Oxoby

F

URTHER READING:

Daniels, Les. Comix: A History of Comic Books in America. New

York, Bonanza, 1971.

Nyberg, Amy Kiste. Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics

Code. Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

Sabin, Roger. Adult Comics: An Introduction. London, Routledge, 1993.

Coming Out

Since the 1960s, the expression ‘‘coming out’’—once reserved

for young debutantes making their entrée into society—has been

subverted to mean ‘‘coming out of the closet,’’ announcing publicly

that one is gay or lesbian. The phrase is ordinarily used in proclaiming

one’s identity to a broader public, though it can also mean acknowl-

edging one’s sexual orientation to oneself, or even refer to the first

time one acts on that knowledge.

Coming out as a subverted assertion originated in the early

twentieth century among the drag ‘‘debutante’’ balls, which were

popular social events in the American Southeast, especially among

African Americans. Drag queens were presented at these balls, just as

young heterosexual women came out at their own events. It was only

later, in the 1950s ambiance that placed a premium on hiding the

abnormal and atypical, that the connotation of coming out of a dark

closet was added, perhaps because of the expression ‘‘skeleton in the

closet,’’ i.e., a guilty secret.

In the post-Stonewall days of gay liberation, many younger gay

men and lesbians believed that repressing their sexual identities was

unhealthy, a stance supported by a growing body of psychological

evidence and that reflected the loosening of strict gender demarca-

tions in American society. From the 1970s, aspects of gay culture that

had once been secret became widely known for the first time: Straight

culture picked up the term ‘‘coming out’’ and began to broaden its

meaning. In the tell-all society that emerged in the U.S. after the

1970s, people came out on talk shows and in tabloid confessions as

manic-depressives, as neatniks, as witches, and other unexpected

forms of identification, some lighthearted, some deeply serious. Even

within the gay and lesbian community, the usage has expanded as

people came out as everything from bisexuals and transgendered folk

to sado-masochists and born-again Christians.

Another related term, ‘‘outing,’’ emerged in the late 1980s as the

opposite of the voluntary confession that had by then achieved

generally favorable connotations. Some gay activists, angered when

some public and successful gay person insisted on remaining in the

closet, deemed it a political necessity to reveal that closeted figure’s

identity, especially when his or her public pronouncements were at

odds with private behavior. The practice divided the gay and lesbian

community, with more radical voices arguing that outing was mere

justice, while others holding it to be the ultimate violation of privacy.

Outing has also been practiced by vindictive or well-meaning straight

people, or by the media, as was the case with lesbian activist

Chastity Bono.

Activists have long insisted that much of the oppression gays

experience would be diffused if all homosexual people came out

publicly. The first National Coming Out Day was declared on

October 11, 1988, the first anniversary of the second gay and lesbian

March on Washington, D.C. Hoping to maintain some of the spirit of

hope and power engendered by the march, organizers encouraged

gays to come out of the closet to at least one person on that day. Some

organizations have even distributed printed cards for gays to give to

bank tellers and store clerks announcing that they have just served a

gay client.

Perhaps it is because American society has grown so fond of

intimate revelation that the term ‘‘coming out’’ has gained such

popularity. Once it was an ‘‘in-crowd’’ phrase among lesbians and

gays, who chortled knowingly when the good witch in The Wizard of

Oz sang, ‘‘Come out, come out, wherever you are.’’ With book titles

like Lynn Robinson’s Coming Out of the Psychic Closet, and Martin

Liberman’s Coming Out Conservative, coming out has gone beyond

sexual identity to include any form of self-revelation.

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Bono, Chastity, and Billie Fitzpatrick. Family Outing. New York,

Little, Brown and Company, 1998.

Bosanquet, Camilla. Growing Up and Coming Out. New York, State

Mutual Book & Periodical Service, 1985.

Vargo, Marc E. Acts of Disclosure: The Coming-Out Process of

Contemporary Gay Men. Binghamton, New York, Haworth

Press, 1998.

The Commodores

The Lionel Richie-led soul band the Commodores, whose career

peaked in the late 1970s before Richie left for solo fame, is a prime

example of an R & B crossover success. Beginning as an opening act

during the early 1970s for The Jackson Five, the southern-based

Commodores released a handful of gritty funk albums before slowly

phasing into ballad-oriented material, which gained them the most

commercial success. As their audience transformed from being

largely black to largely white, the Commodores’ sound changed as

well, moving toward the smooth lightness of songs like ‘‘Still,’’

‘‘Three Times a Lady,’’ and ‘‘Easy.’’

Formed in 1968 in Tuskegee, Alabama, the group—Lionel

Richie on vocals and piano, Walter ‘‘Clyde’’ Orange on drums, Milan

Williams on keyboards and guitar, Ronald LaPread on bass and

trumpet, Thomas McClary on guitar, and William King Jr. playing a

variety of brass instruments—was signed to Motown in the early

1970s. Avoiding Motown’s assembly-line mode of music produc-

tion—which included in-house songwriters, musicians, and produc-

ers to help create ‘‘the Motown sound’’—this self-contained group of

COMMODORESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

567

The Commodores

talented musicians and songwriters remained relatively autonomous.

They maintained their gritty southern-fried funk sound over the

course of three albums: their 1974 debut, Machine Gun; 1975’s

Caught in the Act; and 1975’s Movin’ On. These three albums built

the group a strong base of R & B fans with their consistently good up-

tempo funk jams such as ‘‘Machine Gun’’ and ‘‘The Zoo (Human

Zoo),’’ but they had not yet made the crossover move. Hot on the

Tracks (1976) showed signs of this move with its slower cuts (‘‘Just to

Be Close to You’’ and ‘‘Sweet Love’’ are notable examples). Their

big crossover move came with 1977’s self-titled breakthrough album,

which contained such party favorites as ‘‘Brick House’’ and ‘‘Slip-

pery When Wet,’’ as well as the adult- and urban-contemporary radio

staple ‘‘Easy.’’

It was the massive success of ‘‘Easy’’ that signaled a new

direction for the group and prompted a solo attempt by Richie (who,

nonetheless, remained in the band for another four years). Next came

the Top 40 hit ‘‘Three Times a Lady’’ from the 1978 album Natural

High and the Billboard number one single, ‘‘Still,’’ from 1979’s

Midnight Magic album—both of which continued the Commodores’

transformation from a chitlin’ circuit southern funk party band to

background music for board meetings, housecleaning, and candle-lit

dinners. In the Pocket, from 1981, was Richie’s last album with the

Commodores, and within a year he left to pursue a solo career.

Without Richie’s songwriting (his songs would always be the

Commodores’ strength) and charisma, the group floundered through

most of the 1980s, with the sole exception of their 1985 Top 40 hit

single ‘‘Nightshift,’’ for which album J. D. Nicholas assumed lead

singing duties. The Commodores suffered another blow when pro-

ducer/arranger James Anthony Carmichael, the man responsible for

shaping the majority of the group’s hits, followed Richie’s departure

in the early 1980s.

Richie went on to have a hugely successful solo career before

virtually disappearing from the commercial landscape in the 1990s.

Between 1981-87, he had thirteen Top Ten hits, which included a

staggering five number one singles—‘‘Endless Love,’’ ‘‘Truly,’’

‘‘All Night Long,’’ ‘‘Hello,’’ and ‘‘Say You, Say Me.’’

—Kembrew McLeod

F

URTHER READING:

Koenig, Teresa. Lionel Richie. Mankato, Crestwood House,

1986.

Nathan, David. Lionel Richie: An Illustrated Biography. New York,

McGraw-Hill, 1985.

Plutzik, Roberta. Lionel Richie. New York, Dell, 1985.

COMMUNES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

568

Communes

Close, interdependent communities not based on family rela-

tionships, communes have a long history in the United States and

continue to represent a strand of American culture and ideology that

sanctions the search for a utopia of peace, love, and equality.

Researcher Benjamin Zablocki defines a commune as a group of

unrelated people who voluntarily elect to live together for an indefi-

nite time period in order to achieve a sense of community that they

feel is missing from mainstream American society. Most commonly

associated with the hippie and flower child members of the 1960s and

1970s counterculture, communes have professed a variety of reasons

for existence and can be politically, religiously, or socially based and

exist in both rural and urban environments. Keith Melville has

observed that commune members are linked by ‘‘a refusal to share the

dominant assumptions that are the ideological underpinnings of

Western society.’’ They are extremely critical of the status quo of the

American consumer society in which they live, and they promote a

new value system centered on peace and love, personal and sexual

freedom, tolerance, and honesty. Members wish to begin living their

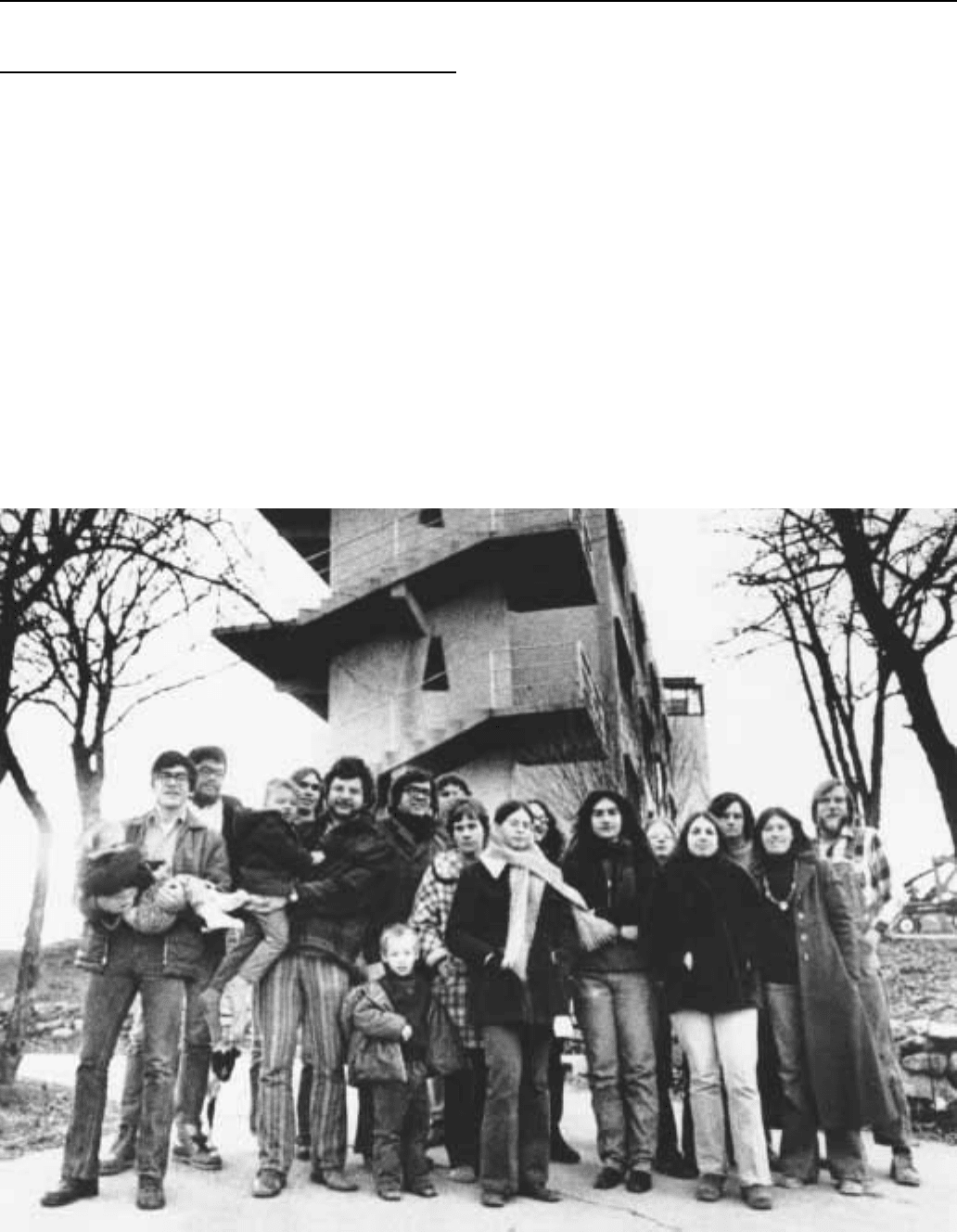

A commune in Lawrence, Kansas in 1972.

vision of a better society away from mainstream society and enjoy the

support of their fellow believers.

Communes have existed throughout world history and in the

United States since its founding in the seventeenth century. Famous

nineteenth-century communes such as the Oneida and Shaker settle-

ments consisted of mostly older, middle-class idealists who strongly

believed in the possibility of creating their vision of the ideal society.

They shared strong religious or political convictions and were more

structured than their twentieth-century counterparts. Many of the later

communes would carry on their utopian mission.

The immediate predecessors of the twentieth-century communal

movement were the beatniks and African-American activists who

fought for social changes that the communalists would later adopt in

their created society in a desire to create a new ethics for a new age.

While communes promoted rural, community, and natural values in

an urban, individualistic, and artificial society, popular cultural

images of communes depict isolated, run-down rural farms where

barely clothed hippies enjoyed economic sharing and free love while

spending most of their days in a drug-induced haze. The high

visibility of the countercultural movement with which communes

were associated made them a large component in the national debate