Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CONDOMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

579

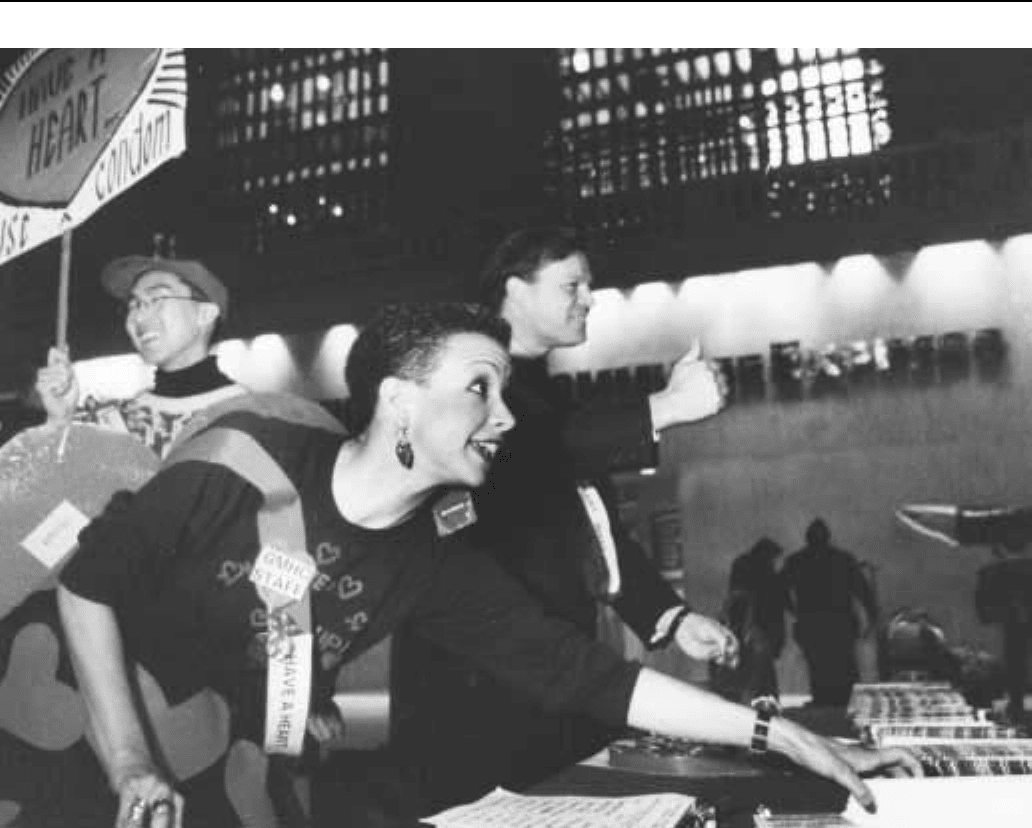

Workers of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis hand out free Valentine’s condoms and AIDS information.

different shapes, colors, flavors, lubrications, and sizes. Some are

equipped with ribs, bumps, dots, or raised spirals to enhance stimula-

tion. The safe-sex message originally associated with condoms is now

being complemented by the marketing strategy claiming that using

condoms is fun, and some are even intended to be used for entertain-

ment only (and not for protection from disease or pregnancy).

Once seen as a great turn off, the condom has appeared with

increasing frequency in (mainly) gay porno movies, especially,

although not exclusively, in the educational safer-sex shorts produced

by AIDS charities and groups of activists. As Jean Carlomusto and

Gregg Bordowitz have summarized, the aim of these safer-sex shorts

is to make people understand that ‘‘you can have hot sex without

placing yourself at risk for AIDS.’’ This has raised important ques-

tions about the possibility of using pornography as pedagogy. This

new use of pornography as a vehicle for safer-sex involves, as safer-

sex short director Richard Fung has pointed out, a ‘‘dialogue with the

commercial porn industry, about the representation of both safer-sex,

and racial and ethnic difference.’’

Looking at the dissemination of ‘‘condom discourse’’ one might

be tempted to conclude that society has finally become more liberat-

ed. There are condom shops, condom ads, condom jokes, condom

gadgets such as key-rings, condom shirts, condom pouches, condom

web-sites with international condom clubs from where chocolate

lovers can top off their evening with the perfect no-calorie dessert: the

hot fudge condom. Yet how effective really is this ‘‘commodification

of prophylaxis’’ (to use Gregory Woods’s words) in terms of preven-

tion and saving of human lives? Is it, in the end, just another stratagem

to speak about everything else but health care and human rights?

—Luca Prono

F

URTHER READING:

Carlomusto, Jean, and Bordowitz, Gregg. ‘‘Do It! Safer Sex Porn for

Girls and Boys Comes of Age.’’ A Leap in the Dark. Edited by

Allan Klusacek and Ken Morrison. Montréal, Vehicule Press, 1992.

Chevalier, Eric. The Condom: Three Thousand Years of Safer Sex.

Puffin, 1995.

Fung, Richard. ‘‘Shortcomings: Questions about Pornography as

Pedagogy.’’ Queer Looks—Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay

Film and Video. Edited by Martha Gever, John Greyson, and

Pratibha Parmar. New York, Routledge, 1993.

CONEY ISLAND ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

580

Panzer, Richard A. Condom Nation—Blind Faith, Bad Science.

Westwood, Center for Educational Media, 1997.

Woods, Gregory. ‘‘We’re Here, We’re Queer and We’re Not Going

Catalogue Shopping.’’ A Queer Romance—Lesbians, Gay Men

and Popular Culture. Edited by Paul Burston and Colin Richard-

son. New York, Routledge, 1995.

Coney Island

Coney Island, with its beach, amusement parks, and numerous

other attractions, became emblematic of nineteenth- and early- twen-

tieth-century urban condition while at the same time providing relief

from the enormous risks of living in a huge metropolis. On Coney

Island, both morals and taste could be transgressed. This was the place

where the debate between official and popular culture was first

rehearsed, a debate which would characterize the twentieth century

in America.

Discovered just one day before Manhattan in 1609 by explorer

Henry Hudson, Coney Island is a strip of sand at the mouth of New

York’s natural harbor. The Canarsie Indians, its original inhabitants,

had named it ‘‘Place without Shadows.’’ In 1654 the Indian Guilaouch,

who claimed to be the owner of the peninsula, traded it for guns,

gunpowder, and beads, similar to the more famous sale of Manhattan.

The peninsula was known under many names, but none stuck until

people called it Coney Island because of the presence of an extraordi-

nary number of coneys, or rabbits.

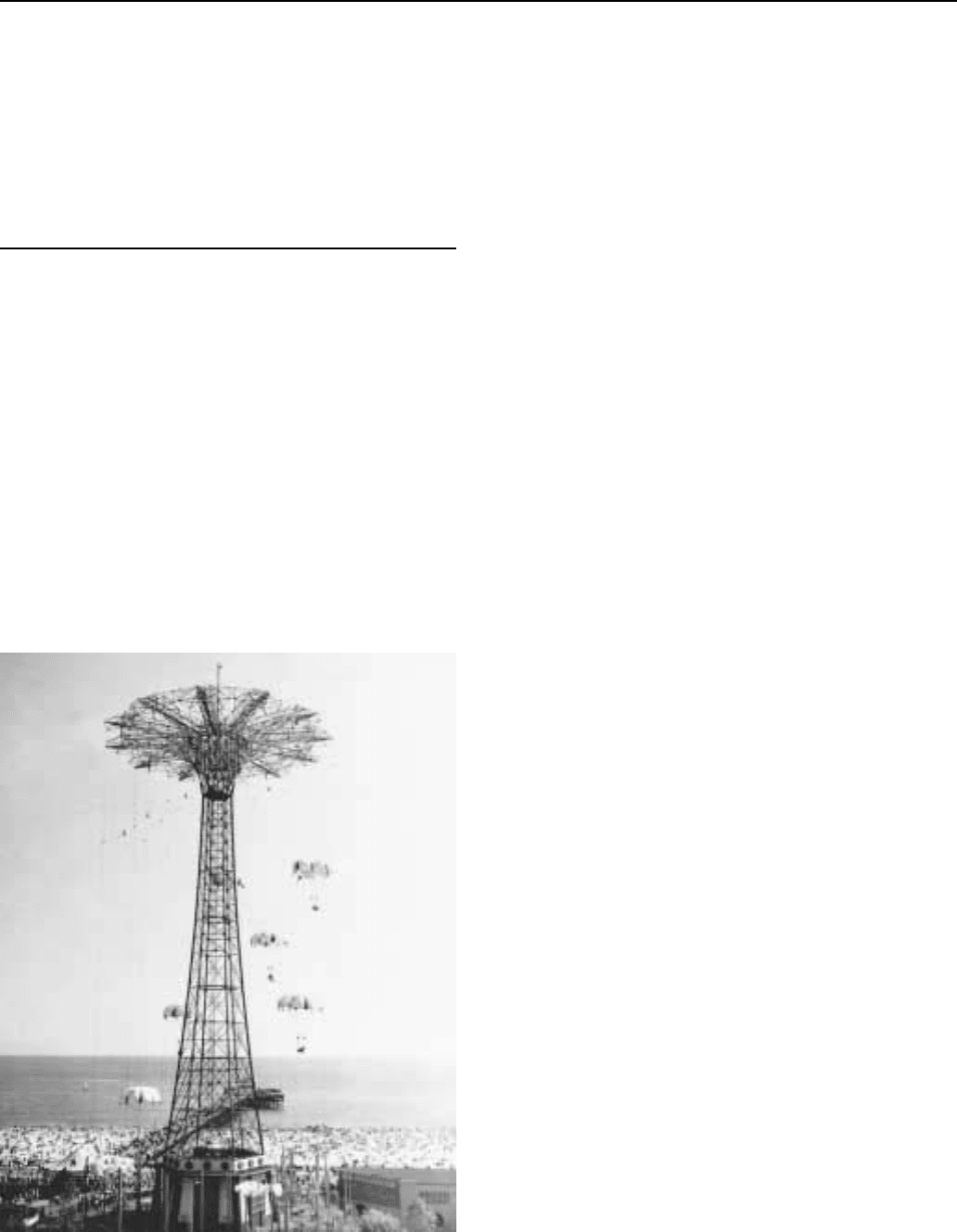

Coney Island, 1952.

In 1823 the first bridge which would connect Manhattan to the

island was built, and Coney Island, with its natural attractions,

immediately became the ideal beach resort for the ever-growing

urban population of Manhattan. By the mid-nineteenth century large

resort hotels had been built. Corrupt political boss John Y. McKane

ruled the island, turning a blind eye to the gangsters, con men,

gamblers, and prostitutes who congregated on the west end of the

island. In 1865 the railroad finally allowed the metropolitan masses

their weekend escape to Coney Island, and the number of visitors

grew enormously, creating a great demand for entertainment and

food. The hot dog was invented on Coney Island in the 1870s. In 1883

the Brooklyn Bridge made the island even more accessible to the

Manhattan masses, who flocked to the island’s beach, making it the

most densely occupied place in the world. The urban masses demand-

ed to be entertained, however, thus the need for pleasure became

paramount in the island’s development. Typical of the time, what

happened on Coney Island was the attempt to conjugate the quest for

pleasure and the obsession with progress.

The result was the first American ‘‘roller coaster,’’ the Switch-

back Railway, built by LaMarcus Adna Thompson in 1884. In 1888,

the short-lived Flip-Flap coaster, predecessor of the 1901 Loop-the-

Loop, used centrifugal force to keep riders in their seats, and an

amazed public paid admission to watch. By 1890 the use of electricity

made it possible to create a false daytime, thus prolonging entertain-

ment to a full twenty-four hours a day.

The nucleus of Coney Island was Captain Billy Boyton’s Sea

Lion Park, opened in 1895, and made popular by the first large Shoot-

the-Chutes ride in America. In competition with Boyton, George C.

Tilyou opened Steeplechase Park in 1897, where science and tech-

nology came together for pleasure and Victorian inhibitions were

lifted. The park was centered around one of the most popular rides on

Coney Island, the Steeplechase Race Course, in which four couples

‘‘raced’’ each other atop wheeled, wooden horses. Steeplechase Park

burned in 1907, but Tilyou rebuilt and reopened it the following year,

and it remained in operation until 1964.

When Boyton went broke, Frederic Thompson and Elmer Dundy

took over Sea Lion Park, remodeled it and opened it as Luna Park in

1903. Luna was a thematic park where visitors could even board a

huge airship and experience an imaginative journey to the moon from

one hundred feet in the air. Coney Island was the testing ground for

revolutionary architectural designs, and Luna Park was an architec-

tural spectacle, a modern yet imaginary city built on thirty-eight acres

and employing seventeen hundred people during the summer season,

with its own telegraph office, cable office, wireless office, and

telephone service. For Thompson, Luna Park was an architectural

training ground before he moved to Manhattan to apply his talent to a

real city. Luna Park eventually fell into neglect and burned in 1944.

The land became a parking lot in 1949.

In the meantime, Senator William H. Reynolds was planning a

third park on Coney Island, ‘‘the park to end all parks.’’ The new park

was aptly called Dreamland. In Reynolds’s words, this was ‘‘the first

time in the History of Coney Island Amusement that an effort has

been made to provide a place of Amusement that appeals to all

classes.’’ Ideology had got hold of entertainment. Opening in 1904,

Dreamland was located by the sea and was noticeable for its lack of

color—everything was snow white. The general metaphor was that

Dreamland represented a sort of underwater Atlantis. There were

detailed reconstructions of various natural disasters—the eruption of

Vesuvius at Pompeii, the San Francisco earthquake, the burning of

CONFESSION MAGAZINESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

581

Rome—as well as a simulated ride in a submarine, two Shoot-the-

Chute rides, and, interestingly, the Incubator Hospital, where prema-

ture babies were nursed. Other Dreamland attractions were the Blue

Dome of Creation, the ‘‘Largest Dome in the World,’’ representing

the universe; the ‘‘End of the World according to the Dream of

Dante’’; three theaters; a simulated flight over Manhattan—before

the first airplane had flown; a huge model of Venice; a complete

replica of Switzerland; and the Japanese Teahouse. One of the most

important structures of Dreamland was the Beacon Tower, 375 feet

high and illuminated by one hundred thousand electric lights, visible

from a distance of more than thirty miles. Dreamland was a success

insofar as it reproduced almost any kind of experience and human

sensation. In May 1911, just before a more efficient fire-fighting

apparatus was due to be installed, a huge fire broke out fanned by a

strong sea wind. In only three hours Dreamland was completely

destroyed. It was Coney’s last spectacle. Manhattan took over as the

place of architectural invention.

In 1919, Coney Island seemed to regain a sparkle of its old glory

when the idea circulated of building a gigantic Palace of Joy—a sort

of American Versailles for the people—which would be a pier

containing five hundred private rooms, two thousand private bath

houses, an enclosed swimming pool, a dance hall, and a skating rink.

Sadly, the Palace of Joy was never built. Soon, the main attraction of

Coney Island became again its beach, an overcrowded strip of land. In

the hand of Commissioner Robert Moses, the island fell under the

jurisdiction of the Parks Department. In 1957, the New York Aquari-

um was established on the island, a modernist building which had

nothing of the revolutionary, dreamlike structure of the buildings of

Reynolds’s era. By now 50 percent of Coney Island’s surface had

become parks again. Nature’s sweet revenge.

—Anna Notaro

F

URTHER READING:

Creedmor, Walter. ‘‘The Real Coney Island.’’ Munsey’s Magazine.

August 1899.

Denison, Lindsay. ‘‘The Biggest Playground in the World.’’ Munsey’s

Magazine. August 1905.

Griffin, Al. ‘‘Step Right Up, Folks!’’ Chicago, Henry Regnery, 1974.

History of Coney Island. New York, Burroughs & Co., 1904.

Huneker, James. The New Cosmopolis. New York, 1915.

Long Island Historical Society Library. Guide to Coney Island. Long

Island Historical Society Library, n.d.

McCullough, Edo. Good Old Coney Island. New York, Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1957.

Pilat, Oliver, and Jo Ransom. Sodom by the Sea. New York,

Doubleday, 1941.

Confession Magazines

During their first 175 years of existence, American magazines

preached long and occasionally in loud tone on personal morality, but

rare was the published foray into the real lives of lower-class

Americans. That oversight ended in 1919 with the introduction of

True Stories, the first of what came to be known as confession

magazines. Founded by health and physical fitness zealot Bernarr

Macfadden, True Stories ‘‘had the conscious ring of public confes-

sion, such as is heard in a Salvation Army gathering, or in an old-

fashioned testimony meeting of Southern camp religionists,’’ accord-

ing to Macfadden’s first biographer Fulton Oursler.

It and other confession magazines were ‘‘a medium for publish-

ing the autobiographies of the unknown,’’ as one editor explained, a

substitute among the poor for lawyers, doctors, and educators. Al-

though True Stories eventually reached a circulation of 2.5 million

during the 1930s, it cost less to produce than most other magazines,

and therefore earned as much as $10,000 a day for its founder. True

Stories and other confession magazines also provided a valuable

outlet for otherwise disconnected people to learn appropriate private

and public social behavior. During times of rapid change, these

magazines helped women to re-establish their identities through the

experiences of other women like themselves. Most importantly, in an

era when sex was rarely mentioned in public, the confession maga-

zines taught both women and men that sex was natural, healthy, and

enjoyable under appropriate circumstances.

The first American magazines were written for upper-class men.

Beginning in the 1820s, sections and eventually titles were aimed at

upper-class women, but they were written in a highly moralistic tone

because women were considered to be the cultural custodians and

moral regulators of society. Belles lettres, popular moralistic fiction,

became the staple of mid-nineteenth century women’s magazines

such as Godey’s Ladies Book and Peterson’s. Writers sentimentalized

about courtship and marriage but offered little practical information

on sex to readers. Another generation of women’s magazines ap-

peared after the Civil War, including McCall’s, Ladies Home Jour-

nal, and Good Housekeeping. These magazines attracted massive

circulations, but were focused on the rapidly changing domestic

duties of women, still carried a highly moralistic tone, and had little to

say about sex. Even into the twentieth century, the advertising and

editorial content of women’s magazines reflected prosperity, social

status, and consumerism; hardly the core problems of everyday

existence for the lower classes.

The first confession magazine publisher was born August 16,

1868, in Mill Springs, Missouri. Before Bernarr Macfadden was ten,

his father had died of an alcohol-related disease and his mother from

tuberculosis. Relatives predicted the sickly, weak boy would die

young as well. Shifted from relative to relative, the young Macfadden

dropped out of school and worked at an assortment of laborer jobs,

learning how to set newspaper type in 1885. But he was drawn into the

world of physical culture as a teen. He studied gymnastics and

physical fitness in St. Louis and developed his body and health as he

coached and taught others. To raise money to promote his ideas on

exercise and diet, he wrestled professionally and promoted touring

wrestling matches. In 1899 he founded Physical Culture, a magazine

that was devoted to ‘‘health, strength, vitality, muscular development,

and the general care of the body.’’ It was the forerunner of contempo-

rary health and fitness publications. Macfadden argued that ‘‘weak-

ness is a crime’’ and offered instruction on physical development.

Macfadden’s diets were opposed by medical authorities and the nude

or nearly nude photographs in his magazine and advertising circulars

came under the scrutiny of obscenity crusader Anthony Comstock

and his followers. Macfadden was fined $2,000 for a Physical Culture

article in 1907 and the magazine is considered to be the start of the

nude magazine industry.

Physical Culture was immensely popular, climbing to a circula-

tion of 340,000 by the early 1930s. Macfadden made large profits

with it and other publishing ventures including books such as What a

CONFESSION MAGAZINES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

582

Young Husband Ought to Know and What a Young Woman Ought to

Know. His wife Mary later claimed that she suggested he expand his

publishing horizons beyond physical fitness around the time of World

War I. She had read the thousands of letters to the editor that poured

into Physical Culture detailing why punching bags, lifting dumbbells,

and doing deep knee bends did not always change an individual’s love

life. Other letters revealed how so-called fallen women who had

discovered physical culture had found new lives for themselves as

wives and mothers. ‘‘The folly of transgression, the terrible effects of

ignorance, the girls who had not been warned by wise parents—a

whole series of tragedies out of the American soil were falling, day

after day, on the desk of [Physical Culture’s] editor,’’ Macfadden’s

biographer Fulton Oursler explained.

In May 1919, the first issue of True Story appeared with the

motto ‘‘Truth is stranger than fiction.’’ For 20 cents a copy, twice the

price of most other magazines, readers received 12 stories with titles

such as ‘‘A Wife Who Awoke in Time’’ and ‘‘My Battle with John

Barleycorn.’’ Most of the protagonists were sympathetic characters,

innocent, lower-class women who appealed to a feminine readership.

Instead of drawings, live models were photographed in a clinch of

love or clad in pajamas while a man brandished a pistol, adding more

realism to the confessions. The first cover featured a man and woman

looking longingly at each other with the caption, ‘‘And their love

turned to hated!’’ The magazine also offered ‘‘$1,000.00 for your life

romance,’’ a cheap price compared to what many magazines paid for

professional contributions. The result was an immediate success,

selling 60,000 issues, and the circulation quickly climbed into

the millions.

Between 1922 and 1926, Macfadden capitalized on True Stories

by producing a host of related titles, including True Romances, True

Love and Romances, and True Experiences. Young Hollywood

hopefuls such as Norma Shearer, Jean Arthur, and Frederic March

were used in True Story photographs. Movie shorts featuring dramati-

zations of the magazine’s stories were shown in theaters simultane-

ously with publication. A weekly ‘‘True Story Hour’’ started on

network radio in 1928, and editions were published in England,

Holland, France, Germany, and the Scandinavian countries. Imitators

quickly appeared, each using some combination of the words true,

story, romance, confessions, and love. The most successful was True

Confessions, founded by Wilford H. Fawcettin 1922, who was a one-

time police reporter for the Minneapolis Journal. Fawcett’s first

publication, Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang, started as a mimeographed

naughty joke and pun sheet in 1919, and went on to become the male

magazine metaphor for the 1920s decline of morality and flaunting of

sexual immodesty. Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang was memorialized in

fellow Minnesotan Meredith Willson’s 1962 Broadway musical

Music Man in a recitation attached to the song ‘‘Trouble.’’ True

Confessions attracted a circulation in the millions and became the

cornerstone of Fawcett Publications, which eventually included titles

such as Mechanix Illustrated and comic books like Captain America.

By its own 1941 account, True Story and its imitators were

magazines for the lower classes, readers too unsophisticated, unedu-

cated, and poor to be of interest to other magazines or advertisers.

They ‘‘made readers of the semi-literate’’ as the wife of one editor

said. Still, a rise in the standard of living during the 1920s meant that

lower-class readers finally had enough income to buy magazines. The

confession magazines gave them a forum to air their concerns and

share solutions in ways not possible in any other publications.

Magazine historian Theodore Peterson maintained that confession

magazines were not a new innovation, just another spin on the old rule

that sex and crime sell. Before confession magazines there was sob

sister journalism, the sentimentalized reporting of crimes of passion

and other moral tales in newspapers. Before newspapers, there were

fictionalized first-person narratives detailing the temptations of young

women such as Moll Flanders. And before novels there were seven-

teenth-century broadsides, written in the first person with a strong

moralizing tone, describing the seductions and murders of scullery

maids and mistresses. Bernarr Macfadden and his wife Mary simply

rediscovered an old formula and applied it the magazine industry.

The mainstream press was predictably critical of confession

magazines. At their best, they were considered mindless entertain-

ment for the masses. At their worst, confession magazines parlayed to

the worst common denominator of the lower classes; sex and repro-

duction. Time maintained that True Story set ‘‘the fashion in sex

yarns.’’ A writer in Harper’s complained that ‘‘to pound into empty

heads month after month the doctrine of comparative immunity

cannot be particularly healthy’’ and that ‘‘it is impossible to believe

that the chronic reader of ’confessions’ has much traffic with good

books.’’ Interestingly, a 1936 survey of True Story readers showed

that a majority believed in birth control, thought wives shouldn’t

work, opposed divorce, and were religious yet tolerant of other faiths.

A study of True Story between 1920 and 1985 revealed that the

magazine reinforced traditional notions of motherhood and feminini-

ty, and challenged rather than supported patriarchal class relations.

Macfadden continued to champion genuine reader confessionals

in his publications during the 1920s and ordered that manuscripts

should be edited for grammatical mistakes only. Subsequent editors

established more control over their productions, beginning with True

Stories’ William Jordan Rapp in 1926. Professionals were hired to

rewrite and create stories, especially after Macfadden was successful-

ly sued for libel in 1927. Still, a survey of 41 True Story contributors

in 1983 revealed that 16 had written of personal experiences, had

never published a story before, and did not consider themselves to be

professional writers. Macfadden lost interest in his confession maga-

zines, becoming involved in the founding of the New York Daily

Graphic newspaper in 1924, ‘‘the True Confessions of the newspaper

world.’’ The newspaper failed in 1932, losing millions of dollars but it

created a sensation among lower- class newspaper readers.

By 1935, the combined circulation of Macfadden’s magazines

was 7.3 million, more than any other magazine publisher, but he was

forced to sell his holdings in 1941 following accusations that he had

used company funds to finance unsuccessful political campaigns,

including a bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1936.

Macfadden died a pauper in 1955, succumbing to jaundice aggravated

by fasting, failing to live 150 years as he had predicted. True Stories

took a more service-oriented path after World War II, offering food,

fashion, beauty, and even children’s features. The major confession

magazines had an aggregate circulation of more than 8.5 million in

1963. The successors of Macfadden Publications acquired the major

contenders to True Stories; True Confessions in 1963 and Modern

Romances in 1978, and continue to publish confessional magazines,

but circulation and advertising revenues have dropped. Soap operas,

made-for-television movies, and cable channels such as Lifetime and

the Romance Channel compete for potential readers along with

supermarket tabloids such as the National Enquirer. As well, lower-

class readers are better educated and have more options for guidance

or help in their personal lives. In the end, the ultimate legacy of the

confession magazines, beyond giving readers information on sex and

CONIFFENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

583

appropriate social behavior, will be that they truly put the word mass

in mass media.

—Richard Digby-Junger

F

URTHER READING:

Cantor, Muriel G., and Elizabeth Jones. ‘‘Creating Fiction for Wom-

en.’’ Communication Research. January 1983, 111-37.

Emery, Michael, and Edwin Emery. The Press and America: An

Interpretive History of the Mass Media. 7th ed. Englewood Cliffs,

N.J., Prentice-Hall, 1992, 283-86.

Fabian, Ann. ‘‘Making a Commodity of Truth: Speculations on the

Career of Bernarr Macfadden.’’ American Literary History. Sum-

mer 1993, 51-76.

History and Magazines. New York, True Story Magazine, 1941, 42.

Hunt, William R. Body Love: The Amazing Career of Bernarr

Macfadden. Bowling Green, Ohio, Bowling Green University

Popular Press, 1989.

Hutto, Dena. ‘‘True Story.’’ In American Mass-Market Magazines,

edited by Alan Nourie and Barbara Nourie. New York, Green-

wood Press, 1990, 510-19.

Macfadden, Mary Williamson, and Emile Gauvreau. Dumbbells and

Carrot Strips: The Story of Bernarr Macfadden. New York, Henry

Holt and Co., 1953.

Oursler, Fulton. The True Story of Bernarr Macfadden. New York,

Lewis Copeland, 1929, 213-14.

Peterson, Theodore. Magazines in the Twentieth Century. Urbana,

University of Illinois Press, 294-303.

Simonds, Wendy. ‘‘Confessions of Loss: Maternal Grief in True

Story, 1920-1985.’’ Gender and Society. Spring 1988, 149-71.

Sonenschein, David. ‘‘Love and Sex in Romance Magazines.’’

Journal of Popular Culture. Spring 1970, 398-409.

Taft, William H. ‘‘Bernarr Macfadden: One of a Kind.’’ Journalism

Quarterly. Winter 1968, 627-33.

Wilkinson, Joseph F. ‘‘Look at Me.’’ Smithsonian Magazine. Decem-

ber, 1997, 136-44.

Yagoda, Ben. ‘‘The True Story of Bernarr Macfadden.’’ American

Heritage. December, 1981, 22-9.

Coniff, Ray (1916—)

Through a unique combination of genuine musical talent fused

with a keen sense of both commercial trends and evolving recording

technologies of the 1950s, arranger/conductor/instrumentalist Ray

Coniff emerged as one of the most popular and commercially success-

ful musicians during the dawn of the stereo age in the late 1950s.

Coniff carried on the big band sound long beyond the music’s original

heyday in the 1940s, and charted 53 albums between 1957 and 1974,

including two million-sellers, and 13 other LPs that reached the Top

Ten and/or went gold.

Coniff was born into a musical family in Attleboro, Massachu-

setts, on November 6, 1916, and followed in his father’s musical

footsteps when he became the lead trombonist of the Attleboro High

School dance band (in which he also gained his first arranging

experience). After graduating in 1934 he pursued a musical career in

Boston, and in 1936 moved to New York where he became involved

with the emerging swing movement of the late 1930s and early 1940s,

playing, arranging, and recording for such top names as Bunny

Berigan, Bob Crosby, Glen Gray, and Artie Shaw. With the advent of

World War II, Coniff spent two years in the army arranging for the

Armed Forces Radio Service, and upon his discharge in 1946 contin-

ued arranging for Shaw, Harry James, and Frank DeVol.

But by the late 1940s the Big Band swing era in which Coniff

had made his first mark was coming to an end, and, as one source put

it, ‘‘Unable to accept the innovations of bop, he left music briefly

around 1950.’’ While freelancing at various nonmusical jobs to

support his wife and three children, Coniff also made a personal study

of the most popular and commercially successful recordings of the

day in an effort to develop what he hoped might prove a new and

viable pop sound. His efforts paid off in 1955 when Coniff was hired

by Columbia Records. At Columbia he was soon providing instru-

mental backup for chart-toppers by the label’s best artists, among

them Don Cherry’s ‘‘Band of Gold,’’ which hit the Top Ten in

January 1956, Guy Mitchell’s ‘‘Singing the Blues,’’ Marty Robbins’s

‘‘A White Sport Coat,’’ and two million-sellers by Johnny Mathis.

His singles arrangements led to Coniff’s first album under his

own name: S’Wonderful! (1956) sold half a million copies, stayed in

the Top 20 for nine months, and garnered Coniff the Cash Box vote

for ‘‘Most promising up-and-coming band leader of 1957.’’ Coniff’s

unique yet highly commercial sound proved irresistible to both

listeners and dancers (and stereophiles) and S’Wonderful! launched a

long series of LPs, the appeal of which has endured into the digital age.

The classic sound of the Ray Coniff Orchestra and Singers was a

simple, but unique, and instantly recognizable blend of instrumentals

and choral voices doubling the various orchestral choirs with ‘‘oooos,’’

‘‘ahs,’’ and Coniff’s patented ‘‘da-da-das.’’ His imaginative arrange-

ments were grounded in the solid 1940s big band sound of his early

years, while now placing a greater emphasis on recognizable melody

lines only slightly embellished by improvisation. Touches of exotic

instrumentation such as harp and clavinet sometimes also found their

way into the orchestrations. This jazz-tinged but accessibly commer-

cial sound was backed up by danceable, sometimes electrified mod-

ern beats derived in equal parts from the classic shuffle rhythms

which Coniff made his own, and more contemporary Latin and rock-

derived rhythms. Coniff’s initially wordless backup chorus soon

graduated to actual song lyrics and, as the Ray Coniff Singers,

recorded many successful albums on their own.

The emergence of commercial stereo in the late 1950s emphati-

cally influenced the new Coniff sound, and his Columbia albums

brilliantly utilized the new stereophonic, multitrack techniques. Even

today they remain showcases of precise, highly defined, and proc-

essed stereo sound. Coniff’s popularity on records during this period

led to live performances, and with his popular ‘‘Concert in Stereo’’

tours the maestro was among the first artists to accurately duplicate

the electronically enhanced studio sound of his recordings in a live

concert hall setting.

Coniff’s best and most enduringly listenable albums date from

the period of his initial popularity on Columbia Records in the late

1950s and early 1960s: among them, Say It with Music (1960),

probably his best and glossiest instrumental album, and It’s the Talk

of the Town (1959) and So Much in Love (1961), both with the Ray

Coniff Singers. These albums and much of Coniff’s original Colum-

bia repertory were drawn mostly from the popular, Broadway, and

movie song standards that also had been favored in the big band era.

CONNORS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

584

Coniff also recorded two Concert in Rhythm albums showcasing

rhythmic pop adaptations of melodies by Tchaikovsky, Chopin,

Puccini, and other classical composers. But as his popularity and

repertory grew, an increasing emphasis was placed on the contempo-

rary Hit Parade. ‘‘Memories Are Made of This’’ (1963), with its

calculated awareness of ‘‘Top 40’’ teen hits, was a prophetic album in

this respect. By the late 1960s Coniff exclusively recorded contempo-

rary songs, and two vocal albums, It Must Be Him, and Honey, both

went gold.

Coniff’s sales fell off after 1962 but were revived in 1966 by the

release of Somewhere My Love. The album’s title tune was a vocal

adaptation of French composer Maurice Jarre’s orchestral ‘‘Lara’s

Theme’’ from the popular 1965 film version of the Boris Pasternak

novel Doctor Zhivago, and the LP won Coniff a Grammy, hitting No.

1 on both the pop and easy listening charts. While Somewhere put

Coniff back on the charts, it also ensconced his sound in the ‘‘easy

listening’’ mode which would more or less persist throughout the rest

of his prolific recording career. (It also might be noted that in 1966

Coniff shared the million-seller charts with the Beatles, the Monkees,

and the Mindbenders.)

Coniff continued recording and performing his popular interna-

tional tours and Sahara Hotel engagements at Lake Tahoe and Las

Vegas through the 1980s and 1990s. In March of 1997, at age 80 and

after a 40-year collaboration with Columbia/CBS Records/Sony

Music that resulted in more than 90 albums selling over 65 million

copies, Coniff signed a new recording contract with Polygram Rec-

ords which released his one hundredth album, I Love Movies. My

Way, an album of songs associated with Frank Sinatra, was re-

leased in 1998.

—Ross Care

F

URTHER READING:

Kernfeld, Barry, editor. New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. London,

Macmillan Press Limited, New York, Grove’s Dictionaries of

Music Inc., 1988.

Murrells, Joseph, editor. Million Selling Records from the 1900s to

the 1980s: An Illustrated History. New York, Arco Publishing,

Inc., 1985.

Connors, Jimmy (1952—)

Born September 2, 1952 in East St. Louis, Illinois, James Scott

(Jimmy) Connors started playing tennis at the age of two, and grew up

to become one of the most recognizable and successful pros in the

history of the sport. His rise to the top of the game helped spark the

tennis boom that took place in America in the mid-1970s, bringing

unprecedented numbers of spectators out to the stands. Like his

equally competitive (and even more temperamental) compatriot John

McEnroe, tennis fans either loved Connors or hated him. His determi-

nation, intensity, and will to win could be denied by no one, and his

penchant for becoming embroiled in controversial disputes over tour

policy was legendary.

As was the case with his one-time fiance, American tennis

legend Chris Evert, Connors was raised to play the game by a

determined parent who also happened to be a teaching pro. Gloria

Thompson Connors had her son swinging at tennis balls even before

he could lift his racket off the ground; this early training, combined

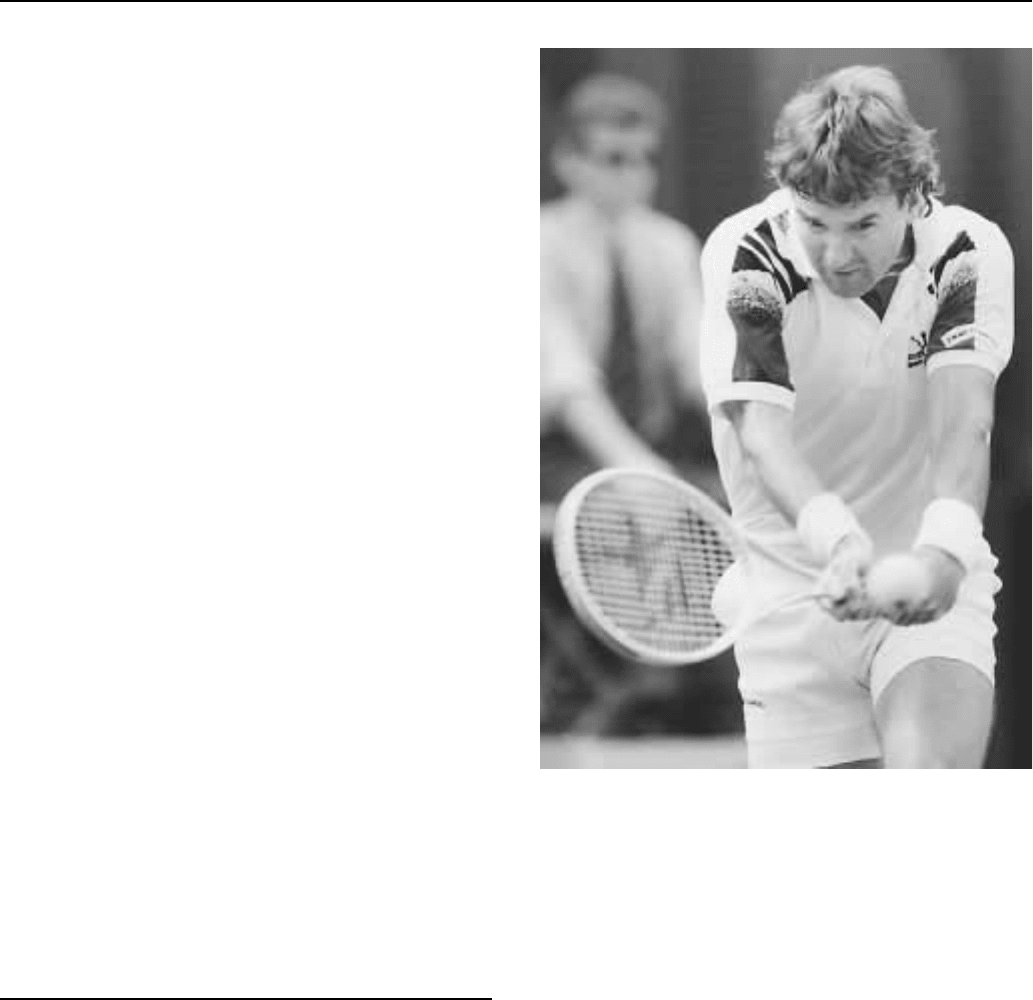

Jimmy Connors

with Connors’ natural ability and never-say-die attitude, paved the

way for his later success. At the 1970 United States Open in Forest

Hills, an 18-year-old and still unknown Connors teamed with his

much older mentor Pancho Gonzalez to reach the quarterfinals in

doubles. A year later, while attending the University of California at

Los Angeles, Connors would become the first freshman ever to win

the National Intercollegiate Singles title. But neither that honor, nor

his All-American status, was enough to prevent him from dropping

out of school in 1972 to become a full-time participant on the men’s

pro circuit.

Connors finished 1973 sharing the number one ranking in the

United States with Stan Smith. The next year he reigned supreme, not

just in the States but around the world. Winner of an unbelievable 99

out of 103 matches, and 14 of the 20 tournaments he entered

(including the Australian Open, Wimbledon, the United States Open,

and the United States Clay Court Championships), Connors totally

dominated the competition in a sport that was exhibiting spectacular

growth. Two surveys taken in 1974 showed an eye-popping 68

percent hike in the number of Americans claiming to play tennis

recreationally, and a 26 percent jump in the number of those saying

they were fans of the pro circuit. As a result, tournament prize money

increased dramatically. In 1978, Connors became the first player to

exceed $2 million in career earnings.

CONSCIOUSNESS RAISING GROUPSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

585

Although many potential fans refused to jump on the Connors

bandwagon—his behavior towards umpires, linesmen, and opposing

players was often reprehensible, and he repeatedly refused to partici-

pate in the international Davis Cup team tournament—few tennis

lovers could resist watching him perform. Bill Riordan, Connors’

shrewd manager, capitalized on his client’s charismatic persona by

arranging a pair of made-for-television exhibition singles matches

dubbed the ‘‘Heavyweight Championship of Tennis.’’ Connors,

never one to shy away from the spotlight, won them both (years later,

he would defeat Martina Navratilova in a gimmicky ‘‘Battle of the

Sexes’’ handicap match). The unprecedented media coverage of these

much-hyped events landed Connors a Time magazine cover photo in

1975. Riordan was also behind the highly publicized $40 million

antitrust suit Connors brought against the Association of Tennis

Professionals and Commercial Union Assurance (sponsor of the ILTF

Grand Prix) a year earlier. It was alleged that these organizations were

conspiring to monopolize professional tennis by barring any player

who had signed up to play in the newly formed World Tennis League

from competing in the 1974 French Open. Thus, Connors was denied

his shot at the elusive Grand Slam that year. By the end of 1975,

Connors split with Riordan and dropped the hotly contested lawsuit;

only then did his relations with fellow tour players begin to improve.

None of Connors’ off-court battles had an adverse effect on his

game in the 1970s. Though he lacked overpowering strokes, Connors

was a dynamic shotmaker with the mentality of a prizefighter. His

trademark two-fisted backhand, along with an outstanding return of

serve, surprising touch, and the ability to work a point, all contributed

to his success. Number one in the world five times (1974-78),

Connors won a total of eight Grand Slam singles championships,

including five United States Opens. He is also the only player to have

won that title on three different surfaces (grass, clay, and hard courts).

In 1979, Connors disclosed that he and former Playboy Play-

mate-of-the-Year Patti McGuire had gotten married in Japan the

previous year. Around this time his game suffered something of a

decline. He failed to reach the final round of the United States Open

for the first time in six years, and his once-fierce rivalry with Bjorn

Borg lost its drama as he got crushed by the Swede four times. But

predictably for someone of his competitive spirit, Connors recommit-

ted himself, and won two more United States Open titles in the 1980s.

For a long time, it seemed certain that Connors’ biggest contri-

bution to American culture would be the sense of mischief and

passion he brought to the once aristocratic game of tennis. But his

determination to postpone retirement and continue fighting on court

in the latter stages of a storied 23-year career gave him a new claim to

fame, as he endeared himself to older spectators and even non-tennis

fans. At age 39, Connors rose from number 936 in the world at the

close of the previous year to make it all the way to the semifinals of the

United States Open in 1991. En route, he came from way behind to

defeat a much younger Aaron Krickstein in dramatic fashion. Ironi-

cally, it is likely that the match people will remember most is the one

that came in a tournament he did not win. Considering that Connors

holds 109 singles titles—tops in the Open era—along with 21 doubles

titles, this is nothing for him to lose any sleep over. In 1998, Connors

was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

—Steven Schneider

F

URTHER READING:

Burchard, Marshall. Jimmy Connors. New York, G.P. Putnams,

1976.

Collins, Bud, and Zander Hollander, editors. Bud Collins’ Modern

Encyclopedia of Tennis. New York, Doubleday, 1980.

Consciousness Raising Groups

A tactic usually associated with the U.S. Women’s Liberation

Movement (WLM) and other feminist-activist groupings born in the

late 1960s, consciousness raising involved a range of practices that

stressed the primacy of gender discrimination over issues of race and

class. Grounded in practical action rather than theory, consciousness

raising aimed to promote awareness of the repressed and marginal

status of women. As proclaimed in one of the more enduring activist

slogans of the 1960s—‘‘The personal is political’’—consciousness

raising took several forms, including the formation of devolved and

non-hierarchical discussion groups, in which women shared their

personal (and otherwise unheard) experiences of everyday lives lived

within a patriarchal society. Accordingly, the agenda of conscious-

ness raising in the early days very often focused on issues such as

abortion, housework, the family, or discrimination in the workplace,

issues whose political dimension had been taken for granted or

ignored by the dominant New Left groupings of the 1960s.

As a political tactic in its own right, consciousness raising

received an early definition in Kathie Sarachild’s ‘‘Program for

Feminist Consciousness Raising,’’ a paper given at the First National

Convention of the Women’s Liberation Movement in Chicago, in

November 1968. Many of those involved in the early days of WLM

had been politicized in the Civil Rights struggle and the protests

against the Vietnam War. But they had become disenchanted with the

tendency of nominally egalitarian New Left organizations, such as the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Students

for a Democratic Society (SDS), to downplay or omit altogether the

concerns of women, and had struck out on their own. When chal-

lenged on the position of women within his organization in 1964,

SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael had replied that ‘‘The only position

for women in SNCC is prone.’’ As late as 1969 SDS produced a

pamphlet that observed that ‘‘the system is like a woman; you’ve got

to fuck it to make it change.’’ The frustration of feminist activists in

the 1960s produced a new women’s movement, which stressed the

patriarchal content of New Left dissent, almost as much as it raised

awareness about gender and power in the everyday arenas of home

and work.

As a political strategy, consciousness raising placed a high value

on direct, practical action, and like much political activism of the

1960s and early 1970s, it produced inventive outlets for conducting

and publicizing political activity. In 1968 the WLM took conscious-

ness raising to the very heart of New Left concerns by conducting a

symbolic ‘‘burial’’ of traditional femininity at Arlington Cemetery—

the site of many protests at the ongoing conflict in Vietnam. As an

exercise in consciousness raising, the mock funeral aimed to publi-

cize the patriarchal tendency to define grieving mothers and bereaved

widows in terms of their relationships with men. Similar guerilla style

demonstrations marked the high point of consciousness raising as a

form of direct action during the late 1960s. The New York Radical

Women (NYRW) disrupted the Miss America pageant at Atlantic

City in September 1968; the WITCH group protested the New York

Bridal Fair at Madison Square Garden on St. Valentines Day 1969.

CONSPIRACY THEORIES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

586

Other groups who employed similar tactics during this period includ-

ed the Manhattan-based Redstockings, the Feminists, and the New

York Radical Feminists.

The emphasis which early WLM consciousness raising placed

upon small groups of unaffiliated women shows its roots in the anti-

organizational politics of the New Left against which it reacted. The

WLM may have reacted sharply against what it saw to be the

patriarchal politics of SDS, but it shared with the New Left an

emphasis on localized political activity exercised through small

devolved ‘‘cells,’’ which valorized the resistance of the individual to

institutional oppression. In common with certain tendencies of the

New Left, the premium placed upon an overtly personal politics has at

times served to obscure the original commitment of consciousness

raising to a more collective revolution in social definitions of gender

and gender roles. One of the more visible legacies of consciousness

raising can be seen in the proliferation of Women’s Studies courses

and departments at universities and colleges during the closing

decades of the twentieth century.

—David Holloway

F

URTHER READING:

Buechler, Steven M. Women’s Movements in the United States:

Woman Suffrage, Equal Rights, and Beyond. New Brunswick,

Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Castro, Ginette. American Feminism: A Contemporary History. New

York, New York University Press, 1990.

Whelehan, Imelda. Modern Feminist Thought: From the Second

Wave to Post-Feminism. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University

Press, 1995.

Conspiracy Theories

Once the province of the far right, conspiracy theories have

gained a wider cultural currency in the last quarter of the twentieth

century, and have become widely disseminated in our popular culture

through diverse sources. Spanning every topic from UFOs to ancient

secret societies to scientific and medical research, conspiracy theories

are frequently disparaged as the hobby of ‘‘kooks’’ and ‘‘nuts’’ by the

mainstream. In fact, many theories are well substantiated, but the

belief in a ‘‘smoke-filled room’’ is a patently uncomfortable thought

for most. Although the populace has generally shown a preference for

dismissing conspiracy theories en masse, nevertheless it is now a

common belief that a disconnect exists between the official line and

reality. Crisis and scandal have left their mark on the American

psyche, and popular culture—especially film and television—have

readily capitalized on public suspicions, becoming an armature of the

culture of paranoia.

What exactly is a conspiracy theory? Under its broadest defini-

tion, a conspiracy theory is a belief in the planned execution of an

event—or events—in order to achieve a desired end. ‘‘At the center

[of a conspiracy] there is always a tiny group in complete control,

with one man as the undisputed leader,’’ writes G. Edward Griffin,

author of The Creature from Jekyll Island, a work on the Federal

Reserve Board which, in passing, touches on many conspiracy

theories of this century. ‘‘Next is a circle of secondary leadership that,

for the most part, is unaware of an inner core. They are led to believe

that they are the inner-most ring. In time, as these conspiracies are

built from the center out, they form additional rings of organization.

Those in the outer echelons usually are idealists with an honest desire

to improve the world. They never suspect an inner control for other

purposes.’’ This serves as an able definition of conspiracy, but for a

conspiracy to be properly considered as conspiracy theory, there must

be a level of supposition in the author’s analysis beyond the estab-

lished facts. Case in point: the ne plus ultra of conspiracy theories, the

assassination of John F. Kennedy. Regardless of who was responsible

for his murder, what is germane is the vast labyrinthian web of

suspects that writers and researchers have uncovered. It is these

shadowy allegations that comprise a conspiracy theory. The validity

of different arguments aside, in the case of JFK, it is the speculative

nature of these allegations which has left the greatest impression on

popular culture.

Conspiracy theories tend, in the words of James Ridgeway,

author of Blood in the Face, ‘‘to provide what seems to be a simple,

surefire interpretation of events by which often chaotic and perplex-

ing change can be explained.’’ While it would be comforting to be so

blandly dismissive, in the end, a conspiracy theory can only be as

sophisticated as its proponent. Naturally, in the hands of a racist

ideologue, a theory such as a belief in the omnipotence of Jewish

bankers is a justification for hatred. Furthermore, as conspiracy

theorists are wont to chase their quarry across the aeons in a quest for

first causes, their assertions are often lost in the muddle, further

exacerbated by the fact that more often than not, conspiracy theorists

are far from able wordsmiths. Yet, as the saying goes, where there’s

smoke there’s fire, and it would be injudicious to lump all conspiracy

theories together as equally without merit.

A brief exegesis of one of the most pervasive conspiracy theories

might well illustrate how conspiracy theories circulate and, like the

game of telephone—in which a sentence is passed from one listener to

the other until it becomes totally garbled—are embellished and

elaborated upon. At the close of the eighteenth century, the pervasive

unrest was adjudged to be the work of Freemasons and the Illuminati,

two semi-secret orders whose eighteenth-century Enlightenment theo-

ries of individual liberty made them most unpopular to the aristocra-

cy. These groups were widely persecuted and then driven into hiding.

But waiting in the wings, was that most convenient of scapegoats,

the Jews.

The Jews had long been viewed with distrust by their Christian

neighbors. Already viewed as deicides, in the Middle Ages it was also

commonly believed that Jews used the blood of Christian children in

their Sabbath rituals. Communities of Jews were often wiped out as a

result. Association, as it had so often been for the Jews, was sufficient

to establish guilt. Early in the nineteenth century, a theory developed

propounding an international Jewish conspiracy, a cabal of Jewish

financiers intent on ensnaring the world under the dominion of a

world government. The Jews were soon facing accusations of being

the eminence grise behind the Illuminati, the Freemasons, and with

complete disdain for the facts, the French Revolution.

Stories of an international Jewish cabal percolated until, in 1881,

Biarritz, a novel by an official in the Prussian postal service, gave

dramatic form to them. In a chapter entitled ‘‘In the Jewish Cemetery

in Prague,’’ a centennial congregation of Jewish leaders was depicted

as they gathered to review their nefarious efforts to enslave the

Gentile masses. The chapter was widely circulated in pamphlet form

and later expanded into a book, The Protocols of Zion, used as

inflammatory propaganda and distributed by supporters of the Czar.

Distributed widely throughout Europe and America, Hitler would

CONSUMER REPORTSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

587

later cite The Protocols as a cardinal influence in his mature

political beliefs.

The Jewish conspiracy made its way to America in the 1920s,

where the idea was taken up by a rural, white, nativist populace

already convinced the pope was an anti-Christ, Jews had horns, and

all non-Anglo foreigners were agents of Communism. The industrial-

ist Henry Ford fanned the flames by demonizing Jews in his newspa-

per, the Dearborn Independent, in which he published sections of The

Protocols. Whether directly associated with Jews or not, the theory

that American sovereignty was being slowly undermined became an

enduring feature of the nativist right wing. It would be used to explain

everything from the two world wars to the Bolshevik Revolution to

the establishment of the IRS. Unfortunately, alongside the most rabid

anti-Semitic screed there sits many an assertion, both accurate and

well documented, and it is this indiscriminate combination of fact and

fantasy that makes the allegations so disturbing.

For mainstream America, one could properly say that the age of

the conspiracy theory began in the 1950s. More than any obscurantist’s

diatribe, movies gave life and breath to the conviction that civilization

was governed from behind the scenes. Movies were a release valve in

which the fears of that era—fears of Communist invasion, nuclear

annihilation, UFOs—found release, sublimated into science fiction or

crime dramas. The 1950s gave us films with a newfound predilection

for ambiguity and hidden agendas—film noir. Films like Kiss Me

Deadly, The Shack out on 101, North by Northwest, and The

Manchurian Candidate explicate a worldview that is patently con-

spiratorial. They are a far cry from anything produced in the previous

decades. The angst and nuances of film noir carried over to the

science fiction genre. No longer content with fantasy, the frivo-

lousness of early science fiction was replaced by a dread-laden

weltanschauung, a world of purposeful or malevolent visitors from

another planet: visitors with an agenda. The Day the Earth Stood Still,

Invasion of the Body-Snatchers, and Them are standouts of the era, but

for each film that became a classic, a legion of knockoffs stood

arrayed behind.

By the time of Kennedy’s assassination, Americans were look-

ing at world events with a more jaundiced eye. The movement from

Kennedy to Watergate, from suspicion to outright guilt, was accom-

panied by a corollary shift in media perception. The United States

government was directly portrayed as the enemy—no longer intuited

as it had been in the oblique, coded films of the 1950s. Robert Redford

and Warren Beatty made films—All the President’s Men, Three Days

of the Condor, and The Parallax View—that capitalized on the

suspicion of government that Watergate fostered in the public.

It wasn’t until the release of Oliver Stone’s JFK that conspiracy

theories made a reentry into the mainstream. Shortly thereafter, the

phenomenally popular TV series The X-Files, a compendium of all

things conspiratorial—properly sanitized for middle-class sensibili-

ties—made its auspicious debut in 1992. For a generation to whom

the likelihood of UFOs outweighed their belief in the continuance of

social security into their dotage; for whom the McCarthy Era was

history, Watergate but a distant, childhood memory, and JFK’s

murder the watershed in their parents’ history, conspiracy theories

received a fresh airing, albeit heavy on the exotic and entirely free of

racism, xenophobia, and government malfeasance. The show’s suc-

cess triggered a national obsession for all things conspiratorial, and a

slew of books, films, and real-life TV programming made the rounds.

There was even a film titled Conspiracy Theory starring the popular

actor Mel Gibson as a paranoid cabby whose suspicions turn out to be

utterly justified.

By their very nature conspiracy theories are difficult to prove,

and this fact in and of itself largely explains their popularity. They

inhabit a netherworld where truth and fiction mingle together in an

endless dance of fact and supposition. They tantalize, for within this

symbiosis explanations are set forth. After all, it is easier to acknowl-

edge a villain than to accept a meaningless absurdity. Therefore, as

the world grows increasingly complex, it is likely that conspiracy

theories will continue, like the game of telephone mentioned earlier,

to mutate and multiply—serving a variety of agendas. Their presence

in the cultural zeitgeist, however, is no longer assailable: paranoia is

the mainstream.

—Michael J. Baers

F

URTHER READING:

Allen, Gary. None Dare Call It Conspiracy. Seal Beach, Concord

Press, 1971.

Bramley, William. Gods of Eden. New York, Avon Books, 1989.

Epperson, A. Ralph. The Unseen Hand: An Introduction to the

Conspiratorial View of History. Tucson, Publius Press, 1985.

Griffin, G. Edward. The Creature from Jekyll Island. Appleton,

American Opinion, 1994.

Moench, Doug. The Big Book of Conspiracies. New York, Paradox

Press, 1995.

Mullins, Eustace. The World Order: A Study in the Hegemony of

Parasitism. Staunton, Ezra Pound Institute of Civilization, 1985.

Quigley, Carrol. Tragedy and Hope. New York, MacMillan, 1966.

Ravenscraft, Trevor. The Spear of Destiny. New York, G. P. Putnam’s

Sons, 1973.

Ridgeway, James. Blood in the Face. New York, Thunder’s Mouth

Press, 1990.

Still, William. New World Order: The Ancient Plan of Secret Socie-

ties. Lafayette, Huntington House Publishers, 1990.

Consumer Reports

Published since 1936, Consumer Reports has established a

reputation as a leading source of unbiased reporting about products

and services likely to be used by the typical American. It counts itself

among the ten most widely disseminated periodicals in the United

States, with a circulation in 1998 of 4.6 million. In all of its more than

sixty years of production, the journal has never accepted free samples,

advertisements, or grants from any industry, business, or agency.

Maintaining this strict independence from interest groups has helped

make Consumer Reports a trusted source of information.

Consumer Reports is published by Consumers Union, a not-for-

profit organization based in Yonkers, New York. Along with the print

monthly, Consumers Union also creates and distributes many guide

books for consumers, such as the Supermarket Buying Guide and the

Auto Insurance Handbook, as well as newsletters about travel and

health issues, and a children’s magazine called Zillions. There are

Consumer Reports syndicated radio and television shows, and a

popular and successful web page with millions of subscribers. Stating

its mission as to ‘‘test products, inform the public and protect

CONSUMER REPORTS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

588

consumers,’’ Consumers Union has more than 450 persons on its staff

and operates fifty test labs in nine departments: appliances, automo-

biles, chemicals, electronics, foods, home environment, public serv-

ice, recreation and home improvement. The Union operates three

advocacy offices, in Washington, D.C., Austin, Texas, and San

Francisco, that help citizens with questions, complaints, and legal

action about products and services. Consumers Union was also

instrumental in the formation of the Consumer Policy Institute in

Yonkers, which does research in such areas as biotechnology and

pollution; and Consumer International, founded in 1960, which seeks

to unite worldwide consumer interests. All together, the organizations

that comprise Consumers Union have been pivotal in the creation of a

consumer movement and have been responsible for many defective

product recalls, fines on offending industries, and much consumer-

protection legislation.

The history of the founding of Consumer Reports gives a

condensed picture of the consumer movement in the United States. In

1926, Frederick Schlink, an engineer in White Plains, New York,

founded a ‘‘consumer club,’’ with the goal of better informing

citizens about the choices of products and services facing them. With

the industrial revolution not far behind them, consumers in the 1920s

were faced with both the luxury and the dilemma of being able to

purchase many manufactured items that had formerly had to be

custom made. Schlink’s club distributed mimeographed lists of

warnings and recommendations about products. By 1928, the little

club had expanded into a staffed organization called Consumers’

Research, whose journal, Consumers’ Research Bulletin, accepted no

advertising. That same year Schlink and another Consumers’ Re-

search director, engineer Arthur Kallet, published a book about

consumer concerns called 100,000,000 Guinea Pigs: Dangers in

Everyday Foods, Drugs, and Cosmetics.

In 1933, when Schlink moved his organization to the small town

of Washington, New Jersey, he was confronted with his own ethical

dilemmas. When some of his own employees formed a union, Schlink

fired them, prompting a strike by forty other workers demanding a

minimum-wage guarantee and reinstatement of their fired colleagues.

Schlink responded by accusing the strikers of being communists and

by hiring scabs. In 1936, the Consumers’ Research strikers formed

their own organization with Arthur Kallet at its head. They called it

Consumers Union. Their original charter promised to ‘‘test and give

information to the public on products and services’’ in the hopes of

‘‘maintaining decent living standards for ultimate consumers.’’

Early Consumers Union product research was limited because of

lack of funds to buy expensive products to test, but they did research

on items of everyday concern to Depression-era consumers, such as

soaps and credit unions. Within three months of its formation,

Consumers Union published the first issue of Consumers Union

Reports, continuing the tradition of refusing commercial support.

Along with information on product safety and reliability, the new

journal maintained a leftist slant by reporting on social issues such as

business labor practices. Its first editorial stated, ‘‘All the technical

information in the world will not give enough food or enough clothes

to the textile worker’s family living on $11 a week.’’ Threatened by

this new progressive consumer movement, business began to fight

back. Red-baiting articles appeared in such mainstream journals as

Reader’s Digest and Good Housekeeping. Between 1940 and 1950,

the union appeared on government lists of subversive organizations.

By 1942, Consumers Union Reports had become simply Con-

sumer Reports to broaden its public appeal. Both consumption and the

purchase of consumer research had been slowed by the Depression

and World War II, but with the return of consumer spending after

1945, the demand for Consumer Reports subscriptions shot up. In the

postwar economic boom, businesses had very consciously and suc-

cessfully urged citizens to become consumers. Having learned to

want more than food and shelter, people also learned to want more in

less material arenas. They wanted something called ‘‘quality of life.’’

They wanted clean air and water, they wanted to be able to trust the

goods and services they purchased, and they wanted their government

to protect their safety in these areas.

In the boom economy of the 1950s and 1960s, business felt it had

little to fear from organized consumers and did little to fight back.

This, combined with the rise of socially conscious progressive

movements, gave a boost of power and visibility to the consumer

movement. In 1962, liberal president John F. Kennedy introduced the

‘‘consumer bill of rights,’’ delineating for the first time that citizens

had a right to quality goods. The same year, Congress overcame the

protests of the garment industry to pass laws requiring that children’s

clothing be made from flame-resistant fabric. In 1964, the Depart-

ment of Labor hired lawyer Ralph Nader to investigate automobile

safety, resulting in landmark vehicle-safety legislation. A committed

consumer activist, Nader joined the Consumers Union board of

directors from 1967 through 1975.

In 1962, Rachael Carson sparked a new view of the environment

with her ecological manifesto, Silent Spring, a work so clearly

connected to the consumer movement that Consumers Union pub-

lished a special edition. The new environmentalists did research that

resulted in the passage in 1963 of the first Clean Air Act and in 1965

of the Clean Water Act.

The consumer movement and the movement to clean up the

environment attracted much popular support. By 1967, the Consumer

Federation of America had been formed, a coalition of 140 smaller

local groups. The long-established Consumers Union opened its

office in Washington, D.C. to better focus on its lobbying work.

Working together, these groups and other activists were responsible

for the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency, the

Consumer Product Safety Commission, and countless laws insti-

tuting safety standards, setting up fair business practices, and

regulating pollution.

The thriving consumer movement is one of the most significant

legacies of the turbulent period of social change that spanned the

period from the 1950s through the 1970s. As more and more products

and services have been introduced, activists have continued to insti-

gate legislation and create organizations and networks to help con-

sumers cope with the flood of options. From its roots as a club for

consumer advice, Consumers Union has grown into a notable force

for consumer and environmental protection, offering research and

advice on every imaginable topic of interest to consumers from

automobiles and appliances to classical music recordings, legal

services, and funerals. It has retained a high standard of ethics and

value pertaining to the rights of the common citizen. For most of

them, thoughts of a large purchase almost inevitably lead to the

question, ‘‘Have you checked Consumer Reports?’’ The organization

has clung to its progressive politics while weathering the distrust of

big business about its motivations and effectiveness.

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Consumer Reports.’’ http://www.consumerreports.org. May

1999.