Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

OCEANIC

SEDIMENTS

485

<0.1 km

Pac.

Equat. "bulge'

-0.4 km

>1.0km

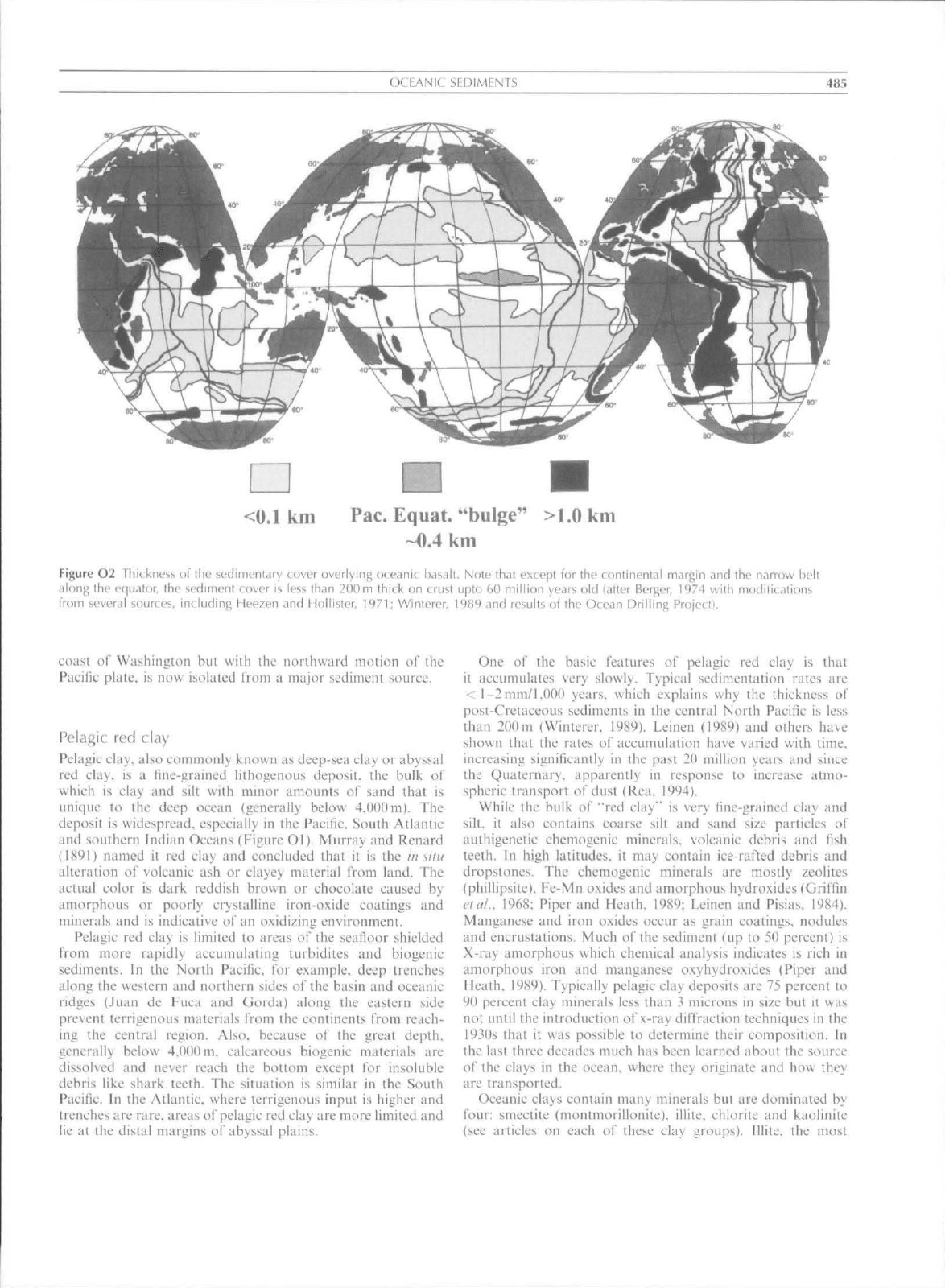

Figure O2 Thickness of (lie sedirnenlary cover overlyin;^ ocednit has.ill. Note th<it except tor the conlinenlal margin jnd thu narrow i>el

.ilnnfi thf e(]uator, ihe sediment cover is less than 2()0m thick on crust upto 60 million years uld latter Berj^er, 1974 with moditii ations

trom several sources, including Heezen and Hollisler,

1971;

Winterer, 1489 and results of the Ocean Drilling Project).

coast of Washington but wilh

IIIL'

northward motion of the

PacKic plalc. is now isolated from a major sediment source.

Pelagic red clay

Pelagic clay, also commonly known as deep-sea clay or abyssal

red clay, is a fine-grained lithogcnous deposit, the bulk of

which is clay and sill with minor amounts of sand ihai is

unique to the deep oceiiii (generally below 4,0t)0m). The

deposit is widespread, especially in ihe Pacitie. South Atlantic

and southern Indian Oceans (Figure 01). Murray and Renard

(IS9I) named it red clay and concluded that it is the in

.silti

alteration of volcanic ash or clayey tnaterial Irom

land.

The

actual color is dark reddish brov\n or choctilate caused by

amorphous or poorly crystalline iron-oxide coatings and

minerals and is indicative of an o.\idizing environment.

Pelagic red elay is limited to areas of the seafloor shielded

from more rapidly accumulating turbidites and biogenie

sediments. In Ihe North Pacific, for example, deep trenches

along the western and northern sides of the basin and oceanic

ridges (Juan de Fuea and Gorda) along the eastern side

prevent terrigenous materials from the eoniinents from reach-

ing the central region. Also, because of fhe great depth.

generally below 4.0()()m, calcareous biogenic materials are

dissoKed and never reach fhe bottom excepf for insoluble

debris like shark teeth. The situation is similar in the South

Pacific. In ihe Atlantic, where terrigenous input is higher and

trenches are rare, areas of pelagic reci clay are more limited and

lie at the distal margins o! abyssal plains.

One of the basie features of pelagic red elay is that

it accumulates very slowly. Typical sedimentation rates are

< l-2mm/l,000 years, whieh explains why the thiekness of

post-Cretaceous sediments in the central North Pacific is less

than 200m (Winterer. 1989). Leinen (1989) and others have

shown thai ihe rates of accumulation have varied with time.

increasing significantly in the past 20 million years and sinee

the Quaternary, apparently in response to increase atmo-

spherie transport of dust (Rea, 1994).

While the bulk of "'red clay"* is very fine-grained clay and

silt, it also contains coarse silt and sand size particles of

authigenetic ehemogenic minerals, volcanic debris and lish

teeth.

In high latitudes, it may contain iee-rafted debris and

dropstones. The chemogenic minerals are mostly zeolites

(phillipsite). he-Mn o.xides and amorphoLis hydroxides (Gril'fin

aul.. 1968: Piper and Heath. 1989: Leinen and Pisias, 1984).

Manganese and iron o.xides occur as grain coatings, nodules

and encrustations. Much of the sediment (up to 50 percenf) is

X-ray amorphous whieh chemical analysis indicates is rich in

amorphous iron and manganese oxyhydroxides (Piper and

Heath.

1989). Typically pelagic eiay deposits are 75 percent to

90 pereent clay minerals less than 3 microns in size but it was

not until the introduction of x-ray diffraction techniques in the

1930s thai if was possible to determine their composition. In

the last three decades much has been learned about the source

of fhe clays in the ocean, where they originate and how they

are transported.

Oeeanie elays eontain many minerals but are dominated by

four: smectite (montniorillonite), illite. chlorite and kaolinite

(see artieles on each of these elay groups). Illite. the most

486

OCFANIC SFDIMFNTS

pervasive clay in fhe ocean, is a general ferm for elays

belonging to the mica group. It is largely land derived and

transported as suspended particulates by rivers and glaciers

and as dust (Kennett. 1982). Smectite is also widespread,

especially in the Pacific and mostly originates in the ocean

from the low temperature alteration ol" volcanic ash and

hydrothermal activity although it is also formed by weathering

on land and transported to the oceans. Kaolinite. a product of

intense weathering in humid, tropical climates, and chlorite, a

mineral from low-grade metamorphie rocks eommon in the

glaciated shield areas of North Ameriea, also are land-derived.

The distribution and relative abundanee of fhe elay minerals

in pelagic clay deposifs indicate fhaf exeept for fhe Soufh

Pacific and parts of fhe Indian Ocean, the primary source of

the clays in the deep ocean is fhe continents. Illite dominates in

the eentral North Paeifie, the North Atlantic and is abundant

off major rivers in the South Atlantie. Koalinite is eoneen-

trated near the eontinents in tropieal areas in the Altantic and

Indian ocean and abundant chlorite is limited fo the margin

near Antarctica and in the Alaskan Bight (Windom, 1976;

Berger. 1974: Lisifzin. 1996). Only the smectite clays of the

Soufh Pacific and Indian Ocean thaf reflecf voleanism and

hydrotherma! aetivity are mainly of oceanic origin. Murray's

conclusions of a century ago regarding the origin of abyssal

red elay are basically correct.

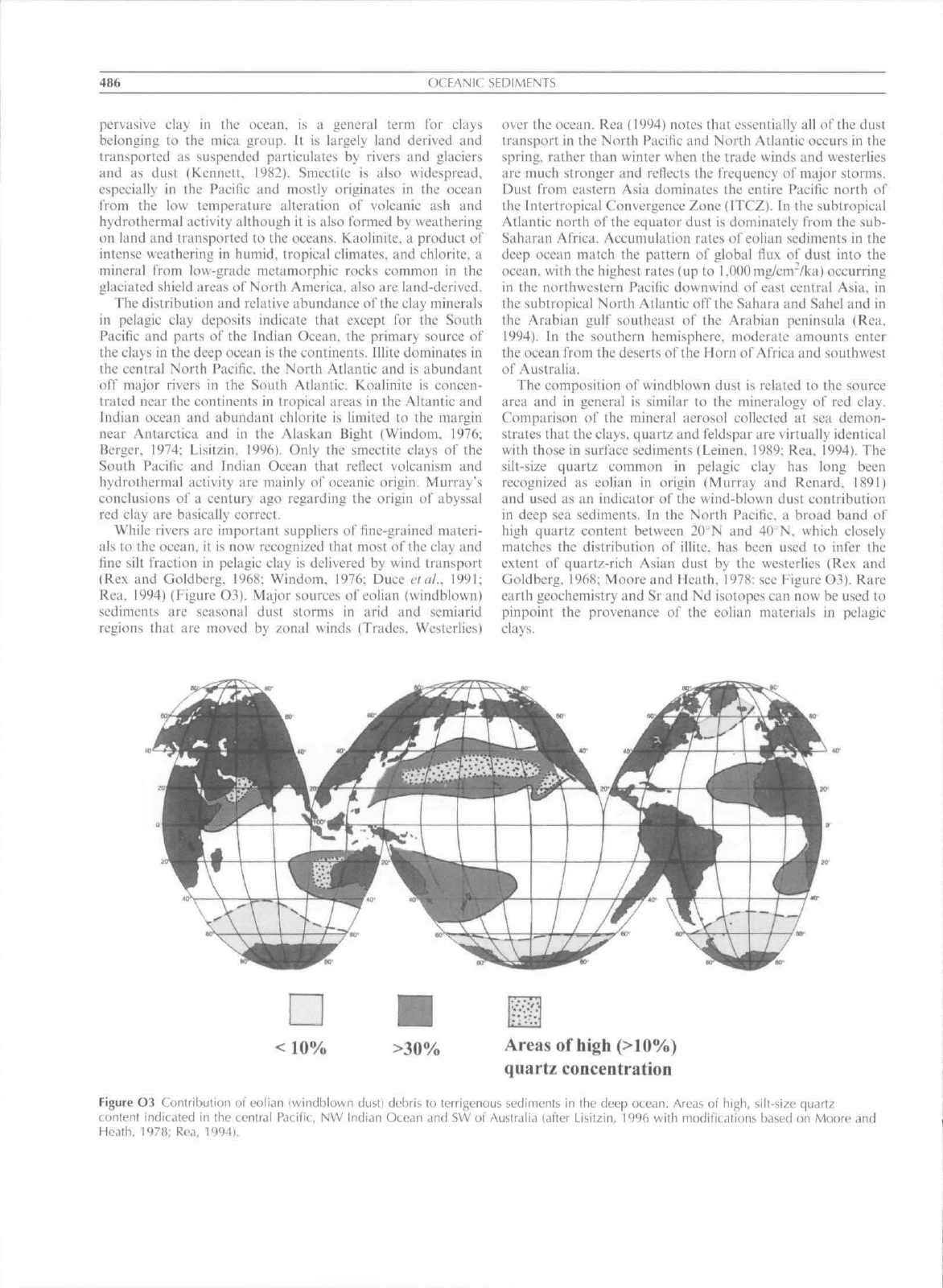

While rivers are importanf suppliers of fine-grained maferi-

als to the oeean, it is now recognii^ed that most of the clay and

fine silt fraction in pelagic clay is delivered by wind transport

(Rex and Goldberg, 1968; Windom. 1976; Duce a iiL, 1991;

Rea. 1994) (Figure 03). Major sources of eolian (windblown)

sediments are seasonal dust sfonns in arid and semiarid

regions thaf are moved by zonal winds (Trades. Westerlies)

over the ocean. Rea (1994) notes that essentially all of fhe dust

transport in the North Pacific and North Atlantic occurs in the

spring, rather than winter when the trade winds and westerlies

are much stronger and refiects fhe frequency of major storms.

Dust from eastern Asia dominates the entire Paeifie north of

the Interfropieal Convergenee Zone (ITCZ). In the subtropical

Aflanf ic norf h of the equator dust is dominately from the sub-

Saharan Africa. Accumulation rates of eolian sediments in the

deep ocean mafeh the paftern of global fiux of dust into the

ocean, with the highest rates (up to l.()OOmg/cm"/ka) occurring

in fhe northwestern Pacific downwind of east central Asia, in

the subtropical North Atlantic off the Sahara and Sahel and in

the Arabian guif soufheasf of the Arabian peninsula (Rea.

1994).

In the southern hemisphere, moderafe amounfs enfer

the ocean fVom fhe deserts of the Horti of Africa and southwest

of Australia.

The composition of windblown dust is related to the source

area and in general is similar to the mineralogy of red elay.

Comparison of the mineral aerosol collected af sea demon-

strates thai the clays, quartz and feldspar are virtually identical

with those in surface sediments (Leinen. 1989; Rea. 1994). The

silt-size quartz common in pelagic clay has long been

recognized as eolian in origin (Murray and Renard. 1891)

and used as an indicator of the wind-blown dusl contribution

in deep sea sediments. In the North Pacific, a broad band of

high quartz content between 20 N and 40 N. which closely

matches the distribution of illite. has been used to infer the

extent of quartz-rieh Asian dusl by the westerlies (Rex and

Goldberg. 1968; Moore and Heath, 1978; see Figure O3). Rare

earth geochemisf ry and Sr and Nd isotopes can now be used fo

pinpoint the provenance of fhe eolian materials in pelagic

clays.

< 10%

>30%

Areas of high (>IO%)

quartz concentration

Figure O3 Contribution of eolian (windblown dust) debris to terrigenous sedimcnls in the deep ocean. Areas of

high,

silt-size quartz

tonlent indicated Jn ihe central Pacific, NW Indian Ocean and SW of Australia (after Lisitzin, 1996 with modifications based on Moore and

Heath,

1978; Re,3,

l')441.

OCEANIC SEDIMENTS

487

Table O,1 (Ommon Minerals in Deep Ocean Sediments

Terrigenous Chemogeiious Other

Aritgotiite Quarts Ferromanganese cosmic spherules

Calcite F"t;klsp;ir Minerals

Opal Clay minerals Baritc

Apatite Mica Phillipsite

Org;inic inattLT Volcanic glass Clinoptiolite

Smectite

Pitlygorskile

Sepioliie

(miidilicd Lilcr Gokiberg. I963>.

As noted by Rea (1994) the eolian eomponent

ot"

pelagic clay

ean be confused with hemipelagie sediments because both are

similar in eomposilion and grain si/e and it is unclear how far

offshore the infliirencc of hemipelagic processes extend. He

restricts studies ol' the eolian compoiienl of pelagic sediments

to deposits more than

1.0(10

km olTshore.

Chemogenic sediments

In addition to the materials introdueed into the oeean. a

number of minerals are precipitated from seawater. either as

primary authigenie minerals or during burial and diagenesis. as

diagenetic alterations of precursor minerals. They are referred

to as ehemogenic. authigenic or hydrogenous sediments.

Common minerals Ibrmed m the pelagic realm include

metal-rich deposits. o\ides and oxyhydroxides of iron and

manganese, silicates, mostly zeolites and clay minerals and

barite (Table O3). Normally ehemogenie minerals are a minor

fraction of the total sediment and masked by the terrigenic or

biogenic eomponent. The exceptions are the metat-rieh

sediments tbrmed by hydrothermal activity on the flanks and

at the crest of oeeanie ridges and in the slowly accumulating

pelagic clays of (he abyssal seafloor. An excellenl review of

sealloor mineralization associated with mid-ocean ridges is

given in Hiimphris aal. (1995).

Within pelagic clays, the chemogenic eomponent ean

represent a signilicant or even major fraetion of the bulk

sediment. Zeolites, hydrous aluminosilieate minerals, espe-

eially the minera! Phillipsite. can account for up to 50 percent

of the bulk sediment in pelagic clay. It is believed to be an

alteration produet of basaltic glass or possibly from the

reaction of biogenic silica and altiminum dissolved in seawater

(Piper and Heath. 1989). Its decreasing abundance below the

surfaee suggests that the mineral is metastabie. Smectite, which

is widespread in ihe oeean, eommonly oeeurs with zeolites in

surface sediments and the co-occurence suggest it is also an

alteration product of volcanic glass.

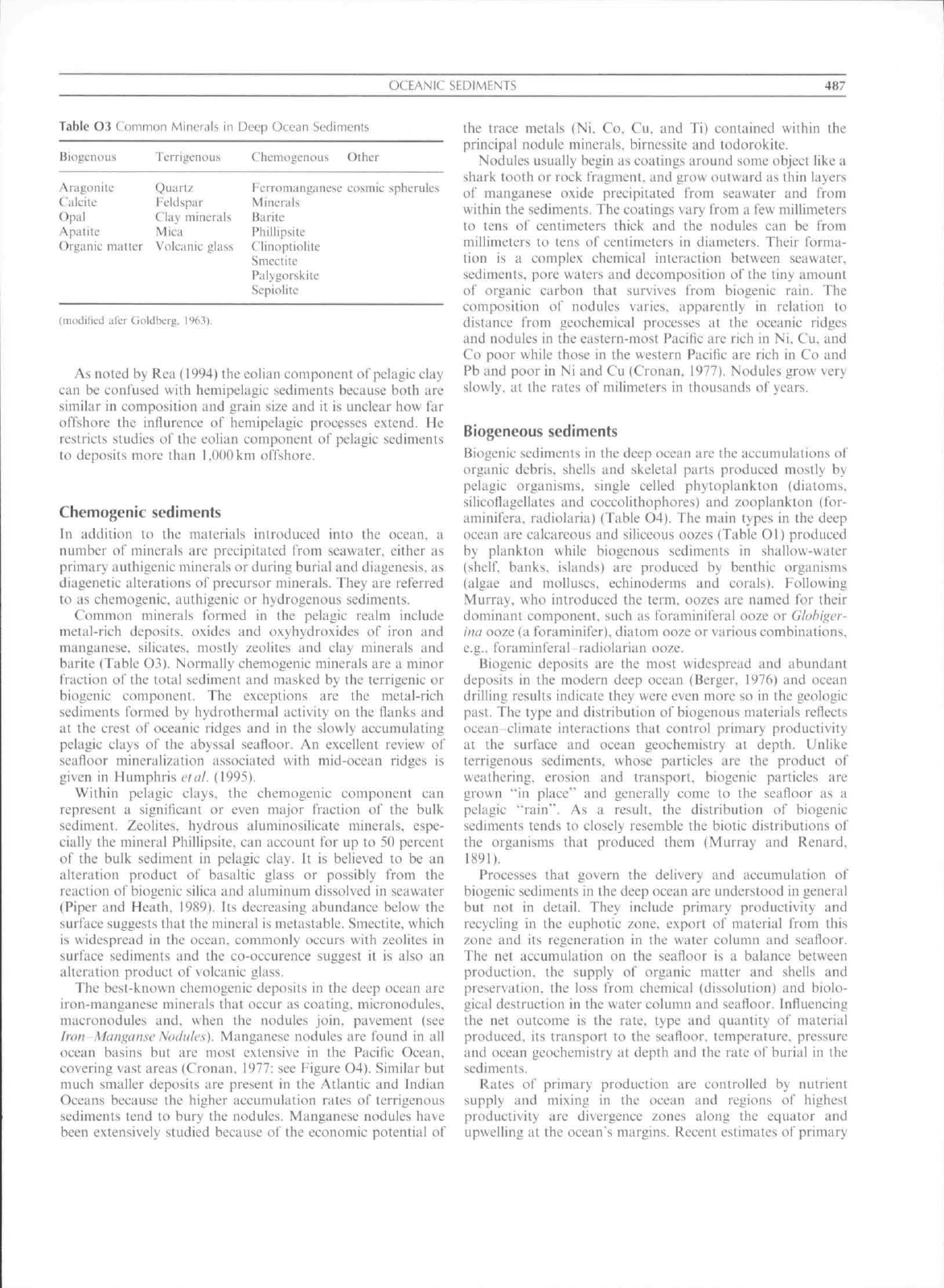

The best-known chemogenic deposits in the deep ocean are

iron-manganese minerals thai oeeur as eoating, micronodules,

macronodules and, when the nodules join, pavement (see

ifDii Miui^ansc Nodules). Manganese nodules are found in all

ocean basins but are most extensive in the Paeilic Ocean.

covering vast areas (Cronan, 1977: see Figure O4). Similar but

much smaller deposits are present in the Atlantic and Indian

Oceans because the higher aeeumulation rates of terrigenous

sediments tend to bury the nodules. Manganese nodules have

been extensively studied beeause of the eeonomic potential of

the trace metals (Ni, Co. Cu. and Ti) contained within the

principal nodule minerals, birnessite and todorokite.

Nodules usually begin as eoatings around some object like a

shark tooth or rock fragment, and grow outward as thin layers

of manganese oxide precipitated from seawater and tVom

within the sediments. The coatings vary Irom a lew millimeters

to tens of centimeters thick and the nodules can be from

millimeters to tens of centimeters in diameters. Their forma-

tion is a complex chemical interaction between seawater,

sediments, pore waters and decomposition of the tiny amount

of organie earbon that survives from biogenie rain. The

composition of nodules varies, apparently in relation to

distance from geochemical processes al the oceanic ridges

and nodules in the eastern-most Paeilic are rich in Ni, Cu, and

Co poor while those in the western Paeifie are rieh in Co and

Pb and poor in Ni and Cu (Cronan, 1977). Nodules grow very

slowly, at the rates of milimeters in thousands of years.

Biogeneous sediments

Biogenie sediments in the deep oeean are the accumulations of

organie debris, shells and skeletal parts produced mostly by

pelagic organisms, single celled phytoplankton (diatoms,

silicoflagellates and coccolilhophores) and zooplankton (for-

aminifera. radiolaria) (Table 04). The main types in the deep

ocean are calcareous and siliceous oozes (Table 01) produced

by plankton while biogenous sediments in shallow-water

(shelf,

banks, islands) are produced by benthic organisms

(algae and molluscs, echinoderms and corals). Following

Murray, who introduced the term, oozes are named for their

dominant component, such as foraminiferal oo7c or Olohiger-

inti ooze (a loraminiler), diatom ooze or various combinations,

e.g., foraminleral radiolarian ooze.

Biogenic deposits are the most widespread and abundant

deposits in the modern deep ocean (Berger, 1976) and oeean

drilling results indicate they were even more so in the geologic

past. The type and distribution of biogenous materials relieets

oeean climate interactions that control primary produetivity

at the surface and oeean geochemistry at depth. Linlike

terrigenous sediments, whose particles are the product of

weathering, erosion and transport, biogenie partieies are

grown "in place'" and generally come to the seafloor as a

pelagic "rain"". As a result, the distribution of biogenie

sediments tends to elosely resemble the biotie distributions of

the organisms that produced them (Murray and Renard.

1891).

Proeesses that govern the delivery and accumulation of

biogenic sediments in the deep oeean are understood in general

but not in detail. They inelude primary productivity and

recycling in the euphotie zone, export of material from this

zone and its regeneration in the water eolumn and seafloor.

The net accumulation on the seafloor is a balance between

production, the supply of organic matter and shells and

preservation, the loss from chemical (dissolution) and biolo-

gical destruction in the water column and seafloor. Influeneing

the nei outcome is the rate, type and quantity of material

produced, its transport to the seafloor, temperature, pressure

and ocean geochemistry at depth ;ind the rate of burial in ihe

sediments.

Rates of primary production are eontrolled by nutrient

supply and mixing in the ocean and regions of highest

productivity are divergence zones along the equator and

upwelling at the ocean's margins. Reeent estimates of primary

488

OCtANIC SEDIMFNTS

Common nodules,

0-30% coverage

V>ry abundant nodules,

locally > 90% coverage

Figure O4 Dislrihulion ot M,ing,inest' nodules (after Berger, l')7fi, hased on data trom Cronan, l')77, with modilicalions from Piper and

Hc.ith, l')H9, Lisitzin,

1'}')()

and olhers.).

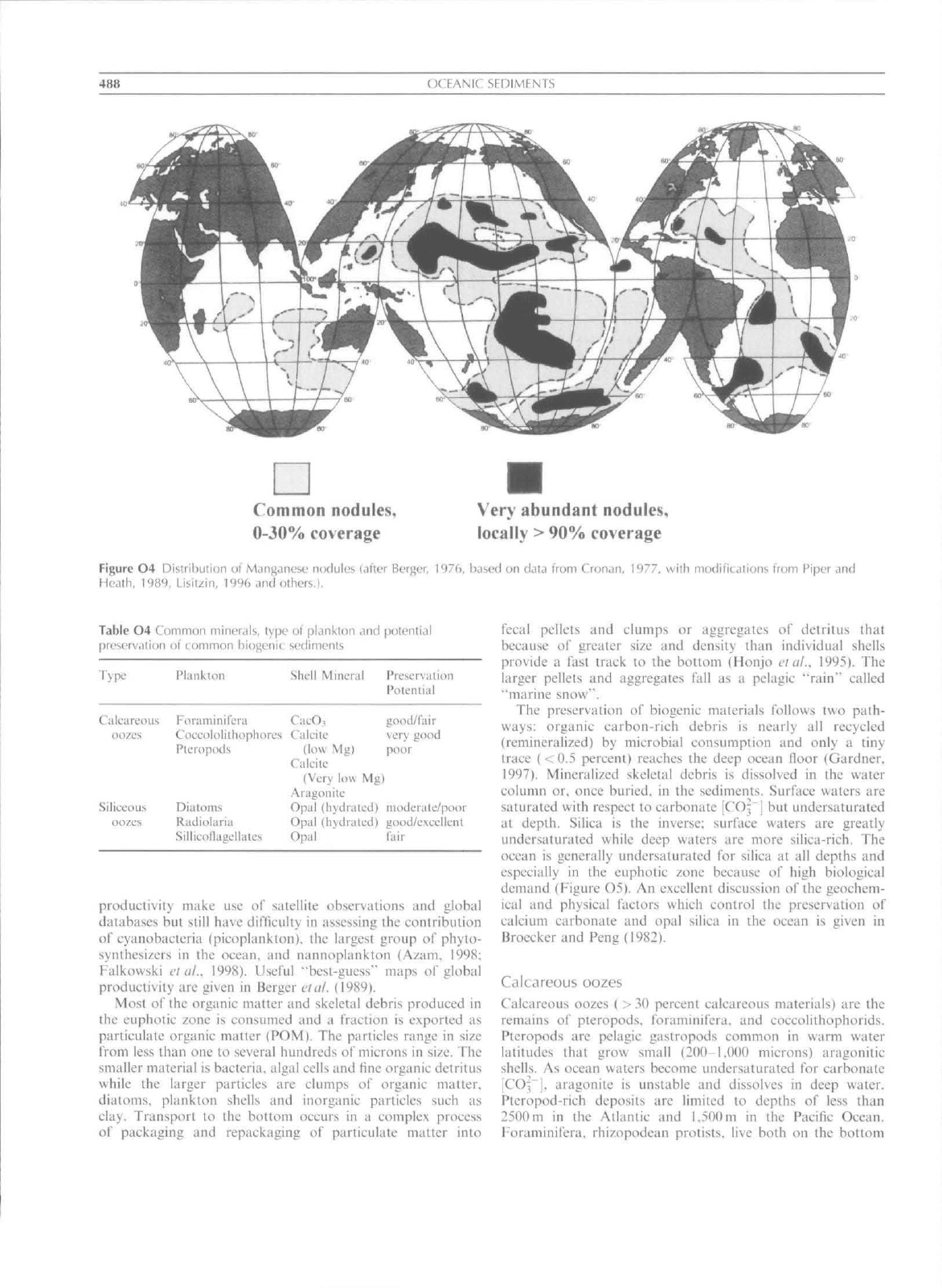

Table O4 Common minerals, type of plankton and potential

preservation of common biogcnit sedimenls

Type

Plankton

Slicll Mineral

Proscrvaiion

Potential

Calcareous Foraminifera CacOi good/fair

oozes Cotcololithophorcs Cak'ile very good

Pteropods (low Mg) poor

Ciilciic

(Very low Mg)

Aragonilo

Siliceous Diatoms Opal (hydrated) moderate/poor

oozes Radiolaria Opal (hydraled) good/cxcellcnl

SillicotJagellates Opal fair

productivity make use o!" satellite observations and global

databases but still have difliculty in assessing the contribution

of cyanobaclcria (picoplankton), the largest group oi" phyto-

synthcsizers in the ocean, and nannoplankton (Azam, 1998;

Falkowski ei a!.. 1998). Useful "best-guess" maps of global

productivity arc given in Berger

(•/(//.

(1989).

Most of the organic nialter and skeletal debris produced in

the euphotie 7onc is consumed and a fraction is exported as

partieulate organie matter (POM). The particles range in size

from less than one to several hundreds of mierons in size. The

smaiier material is bacteria, algal cells and tine orgaiiie detritus

while the larger particles are elumps of organie matter.

diatoms, plankton shells and inorganic particles such as

clay. Transport to the bottom oeeurs in a complex process

of packaging and repackaging of particulate matter into

fecal pellets and clumps or aggregates of detritus that

because of greater size and density than individual shells

provide a fasl track to the bottom (Honjo a a/.. 1995). The

larger pellets and aggregates fall as a pelagie "rain" ealled

"marine snow".

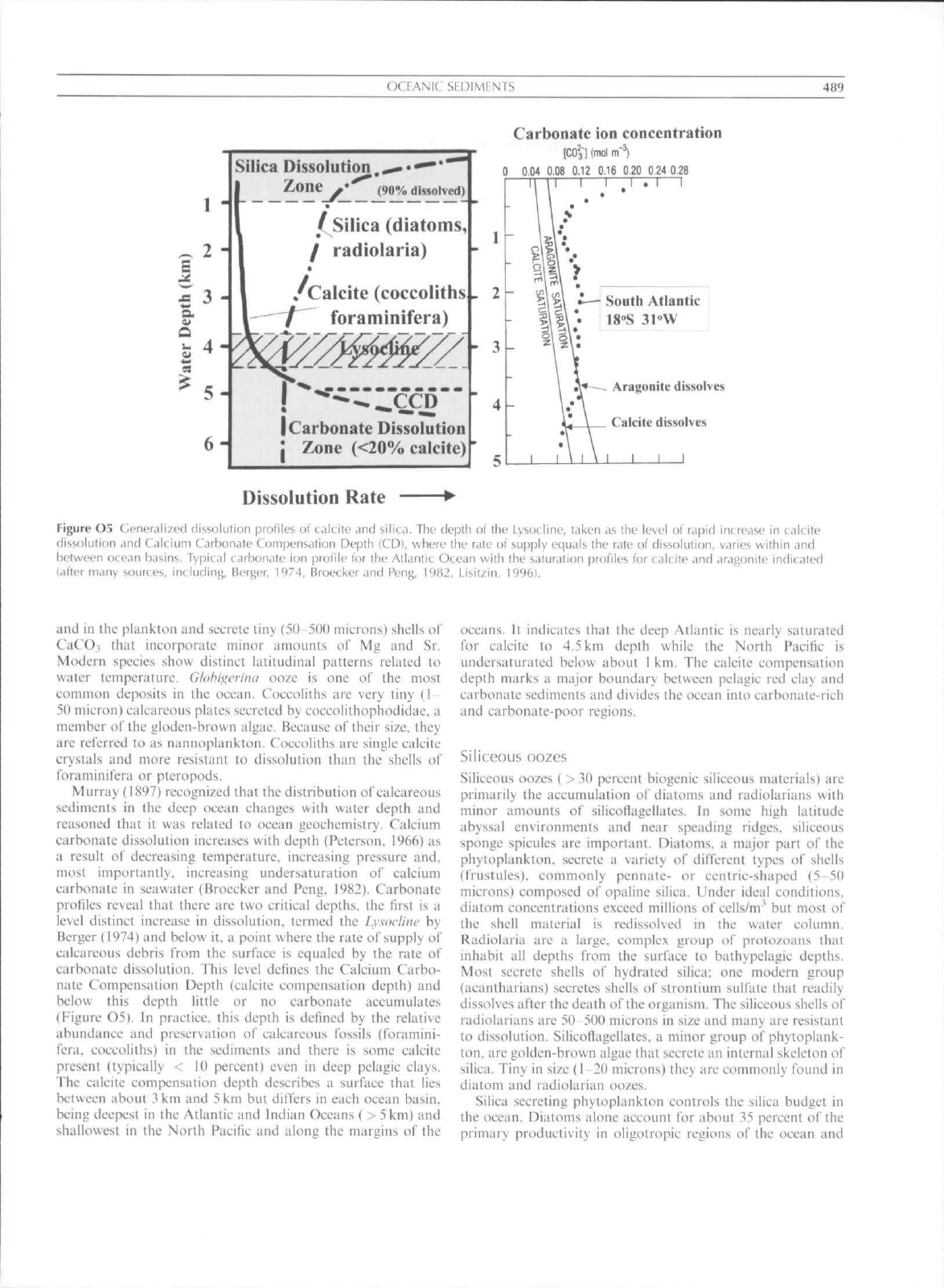

The preservation of biogenie materials follows two path-

ways:

organic earbon-rieh debris is nearly all recycled

(remineralized) by microbia! eonsinnption and only a tiny

trace ( <().5 percent) reaches the deep ocean floor (Gardner,

1997).

Mineralized skeletal debris is dissolved in the water

eolumn or. once buried, in the sediments. Surface waters are

saturated with respeet to carbonate [CO3~] but undersaturated

at depth. Silica is the inverse; surface waters are greatly

undersaturated while deep waters are more silica-rich. The

ocean is generally undersaturated for silica at all depths and

espeeially in the euphotie zone because of high biological

demand (Figure 05). An e.\cellent discussion of the geochem-

ical and physical factors which control the preservation of

calcium carbonate and opal silica in the oeean is given in

Broecker and Peng (1982).

Calcareous oozes

Calcareous oozes ( > 30 percent calcareous materials) are the

remains oi' pteropods, foraminifera, and coccolithophorids.

Pteropods are pelagic gastropods common in warm water

latitudes that grow small (200-1,000 microns) aragonitic

shells.

As ocean waters become undersaturated for carbonate

[CO^"].

aragonite is unstable and dissolves in deep water.

Pteropod-rich deposits are limited to depths of less than

2500 m in the Atlantic and 1,500 m in the Paeifie Ocean.

Foraminiicra. rhizopodean protists, live both on the bottom

OCFANIC SEDIMbNTS

489

Silica Dissolution

*»-•***

^* (90% dissolved)

« ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^

/^Silica (diatoms,

/ radiolaria)

/Calcite (coccoliths

foraminifera)

ICarbonate Dissolution

j Zone (<20% calcite)

Carbonate ion concentration

[CO'sl (moi m"^

0 0.04 0.08 0.12 0.16 0.20 0.24 0.28

. 2

|\^\ ^— South Atlantic

Aragonite dissolves

Calcile dissolves

I I I

Dissolution Rate •

Figure O5 Oneralized dissolution prolilcs of Ldkite cind silit.). The depth of the Lysocline, taken as the level of rapid increase in calcite

(iissolulion and Calcium Carbonate Compensatiun Depth

ICDl,

where the rate of supply equals the rate of dissolution, varies within .inrl

lielween oce.in basins. Typical carbonale ion profile for ihe Atlantic Ocean with the saturation profiles for calcite and aragonile inr!ii:ated

laftor nidny sources, including, Berger, 1974, Broecker and Peng, 1<J(t2, Lisitzin,

19961.

and in ihe plankton and secrete tiny (50 500 microns) shells of

CaC'Oi that incorporate minor iiiiiounts of Mg and Sr.

Modern species show distinct latitudinal patterns related to

water temperature. Glohigcrina ooze is one of the most

common deposits in the ocean. Coccoliths are very tiny (1-

50 micron) calcareous plates secreted by coccolithophodidac. a

member of the gloden-brown algae. Because of their size, they

are referred to as nannoplankton. Coccoliths are single ealeite

crystals and more resislatit to dissolution than the shells of

foraminiicra or pteropods.

Murray (1897) recognized that the distribution of calcareous

sediments in the deep ocean changes with water depth and

reasoned that it was related to ocean geoehemistry. Calcium

carbonate dissolution increases with depth (Peterson, 1966) as

a result of decreasing temperature, increasing pressure and,

most importantly, increasing undersaturation of ealeium

carbonate in seawater (Broecker and Peng, 1982). Carbonate

profiles reveal that there are two critical depths, the first is a

le\el distinct increase in dissolution, termed the

Ly.uicHni'

by

Berger (1974) and below it, a point where the rate of supply of

calcareous debris from the surfaee is equaled by the rate of

carbonate dissolution. This level defines the Calcium Carbo-

nate Compensation Depth (calcite compensation depth) and

below this depth little or no carbonate accumulates

(Figure 05). In praetiee, this depih is defined by the relati\e

abundance and preservation of calcareous fossils (foramini-

fera. coccoliths) in the sediments and there is some ealeite

present (typically < 10 percent) even In deep pelagic clays.

The eaieite eompensation depth describes a surface that lies

between about

3

km and

5

km bul differs in each ocean basin,

being deepest in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans ( >

5

km) and

shallowest in the North Pacific and along the margins of the

oceans. It indicates that the deep Atlantic is nearly saturated

for calcite to 4.5 km depth while the North Pacific is

undersaturated below aboul I km. The calcite eompensation

depth marks a major boundary between pelagic red elay and

carbonate sediments and divides the ocean into carbonate-rich

and carbonate-poor regions.

Siliceous oozes

Siliceous oozes ( > 30 percent biogenic siliceous materials) are

primarily the accumulation of diatoms and radiolarians with

minor amounts of silicoflageliates. In some high latitude

abyssal environments and near speading ridges, siliceous

sponge spieules are important. Diatoms, a major part of the

phytoplankton. seerete a variety of different types of shells

(frustules). commonly pennate- or centric-shaped (5-50

microns) composed of opaline silica. Under ideal conditions,

diatom concentrations exceed millions of cells/m" but most of

the shell material is redissolved in the water column.

Radiolaria are a large, complex group of protozoans that

inhabit all depths from the surfaee to bathypelagie depths.

Most secrete shells of hydrated silica; one modern group

(aeantharians) secretes shells of strontium suKatc that readily

dissolves after the death of the organism. The siliceous shells of

radiolarians are 50 500 microns in size and many are resistant

to dissolution. Silicoflagellates, a minor group of phytoplank-

ton, are golden-brown algae that secrete an internal skeleton of

silica. Tiny in size (I 20 microns) they are commonly (bund in

diatom and radiolarian oozes.

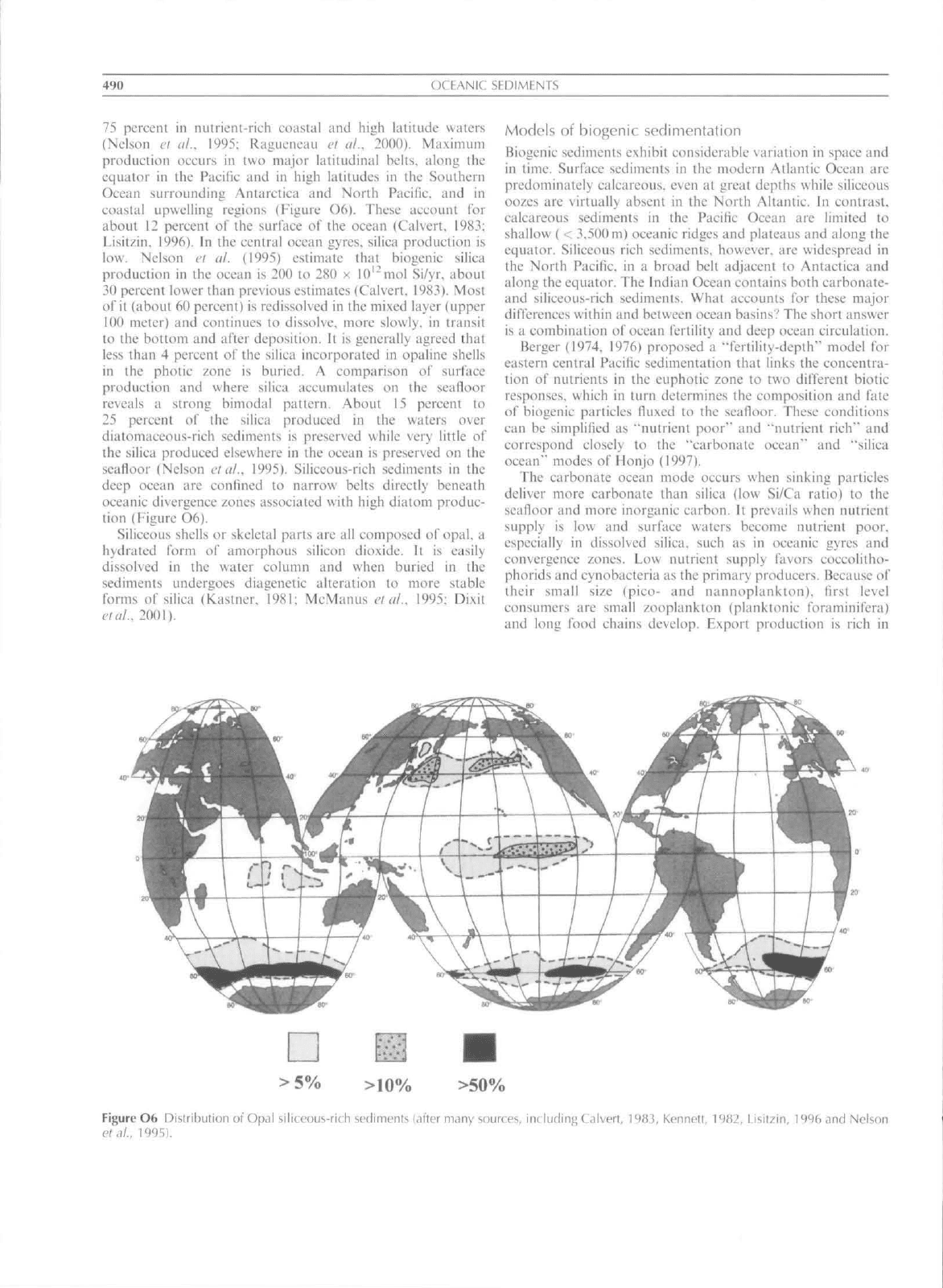

Silica secreting phytoplankton controls the silica budget in

the oeean. Diatoms alone aecount fbr about .15 percent of the

primary productivity in oligotropic regions of the ocean and

490

OCbANlC SEDIMENTS

75 percent in nutrient-rich coastal and high latitude waters

(Nelson ci al.. 1995; Ragueneau ci al.. 2000). Maximum

production occurs in two major latitudinal belts, along the

equator in the Pacific and in high latitudes in the Southern

Ocean surrounding Antarctica and North Pacific, and in

coastal upwelling regions (Figure O6). These account for

about 12 percent ol' the surface of the ocean (Calvert. 1983;

Lisitzin, 1996). In the central ocean gyres, silica production Is

low. Nelson ('/ al. (1995) estimate that biogenic silica

production in the ocean is 200 to 280 x 10'"mol Si/yr, about

30 percent lower than previous estimates (Calvert. 198.1). Most

of it (about 60 percent) is redissolved in the mixed layer {upper

100 meter) and continues to dissolve, more slowly, in transit

to the bottom and after deposition. It is generally agreed that

less than 4 percent of the siliea incorporated in opaline shells

in the photic zone is buried. A comparison of surface

produetion and where silica accumulates on the seafloor

reveals a strong bimodal pattern. About 15 pereent to

25 percent of the silica produced in the waters over

diatomaceoLis-rich sediments is preserved while very little of

the siliea produced elsewhere in the ocean is preserved on the

seafloor (Nelson clal.. 1995). Siliceous-rich sediments in the

deep ocean arc eonflncd to narrow belts directly beneath

oceanic divergence zones associated with high diatom produe-

tion (Figure 06),

Siliceous shells or skeletal parts are all eomposed of opal, a

hydrated form of amorphous silicon dioxide. It is easily

dissolved in the water column and when buried in the

sediments imdergoes diagenetie alteration to more stable

forms of silica (Kastner, 1981; McManus elal.. 1995; Dixit

etal.. 2001).

Models ot biogenic seditnentation

Biogenie sediments exhibit considerable \ariation in space and

in time, Surtace sediments in the modern Atlantic Ocean are

predominately calcareous, even at great depths while silieeous

oozes are virtually absent in the North Altantic. In contrast,

calcareous sediments in the Paciflc Ocean are limited to

shallow ( < 3.500 m) oceanic ridges and plateaus and along ihe

equator, Silieeous rich sediments, however, are widespread in

the North Pacific, in a broad belt adjacent to Antactica and

along the equator. The Indian Ocean contains both carbonate-

and siliceous-rich sediments. What accounts for these major

differences within and between ocean basins? The short answer

is a combination of ocean fertility and deep ocean circulation.

Berger (1974. 1976) proposed a "fertility-depth'" model for

eastern central Pacific sedimentation that links the concentra-

tion of nutrients in the euphotic zone to two different biotic

responses, which in turn determines the composition and t^ate

of biogenic panicles fluxed to the seafloor. These conditions

can be simplilied as "nutrient poor'" and "nutrient rich"" and

correspond elosely to the "carbonate ocean" and "silica

ocean'" modes of Honjo (1997),

The carbonate ocean mode occurs when sinking particles

deliver more carbonate than silica (low Si/Ca ratio) to the

seafloor and more inorganic earbon. It prevails when nutrient

supply is low and surface waters become nutrient poor,

especially in dissolved silica, such as in oceanic gyres and

convergence zones. Low nutrient supply favors coccolitho-

phorids and cynobacteria as the primary producers. Because of

their small size (pico- and nannoplankton), first level

consumers are small zooplankton (planktonic foraminifera)

and long food chains develop. Export production is rich in

>50%

Figure O6 Distribution of Opaf siliceous-rich sedimenls (nfler many sources, ini iiiding Calvert, 1983, Kennett, ^982, Lisitzin, 1996 and Nelson

et3l.. 1995).

OCEANIC .SEDIMFNTS

491

foratiiinifera and eoccoliths and calcareous seditnents accu-

tiiulatc on the seafloor (above the calcite compensation depth).

The silica ocean prevails in oceanic divergence zones and

upwelling areas, where high nutrient concentrations in surface

waters favor diatoms as the primary producers. Diatoms

tnetabolize nutrients faster than other phytoplankton and

reproduce rapidly to create blooms with eell densities of 10^

pcrm\ Short food chains develop beeause large diatoms can

be eaten by higher consutners (large zooplankton and flsh).

Export output is high in organic carbon. Sinking particles are

silica-rich (diatoms, silicoflagellates) and even though a high

proportion of the silica is regeneration in the water column.

the high flux rates lead to siliceous-rich sediments. As Berger

notes,

under these conditions, the bacterial decotnposition of

organic carbon leads to carbon dioxide, carbonic acid and

dissolution of carbonate shells. Despite high production rates,

dissolution rapidly removes carbonate from the sediments.

The second factor is differences in deep ocean circulation

that controls ocean geochemistry, and therefore dissolution

pattcrtis and the general patterti of ocean fertility (nutrient

distribution). Berger (1970. 1974) referred to this as Basin-

Basin ftactionation where deep oeean cireulation leads to the

fractionation of silica and carbonate between ocean basins, ln

ocean basins that exchange deep water outtlow for surface

water inflow (lagoonal-type circulation), like the North

Atlantic, bottom waters are young, nutrient poor, well

oxygenated and tend to be saturated for calcium carbonate.

Such basins accumulate calcareous sediments but dissolve

silica. The contrasting system is an ocean basin that exchange

surface waters for deep water inflow (estuarine-typc circula-

tion),

like the North Paciflc. Here, deep waters pass through

the south Allantie and Indian Oceans before entering the

Pacilic and are old. poorly oxygenated but nutrient rich. In the

long passage, the microbiai breakdown of organic matter uses

dissolved oxygen, produces carbon dioxide and regenerates

nutrients. These waters beeome under saturated for carbonate

but enriched in nutrients and dissolved silica. As these deep

waters arc upwelled to the surface they generate high surface

productivity and diatom-rich debris. Seditnents in this type of

system accumulate siliceous-rich sediments with little calciutn

carbonate.

Today the Pacilic is exporting carbonate and depositing

silica while the North Atlantic is the reverse. However, it

(bllows from the models that a change in climate or the

connections between ocean basins that effeet vertical circula-

tion will bring about changes in ocean fertility and chetnistry.

The result will be changes in biogenie sedimentation like those

observed in the Pleistocene and Tertiary reeord.

Summary

As John Murray observed over a century ago, oozes and clays,

with the accutiiulation of maitfiam'si' nodules and zeolites

where sedimentation rates are very low, cover the deep oeean

floor. At the tnargitis of the basins, close to the continents,

hemipelagic seditnents etieroach on the deep ocean and tnix

with pelagic debris. Because hetnipelagic seditnentation rates

arc 10 1.000 titnes higher than pelagic seditnentation rates,

hemipelagics usually mask the contribution from the overlying

water. Beyond the rcaeh of turbidite and suspension flows, the

terrigenous component of pelagic elays eomes from windblown

dust, traveling thousands of kilometers across the ocean

before finally settling out. This tnatL'rial reaches the seafloor

as part of the pelagic rain as it is ingested by grazers along with

other food particles and transported by fecal pellets and

phytoplankton aggregates. The most widespread deposits in

the deep ocean are biogenie in origin. Foraminiferal ooze

covers nearly 50 percent of the seafloor at depths above the

calcite compensation depth while radiolarian-foraniiniferal-

diatom rich sediments dominate beneath the equator in the

Pacilic and Indian Oceans. In high latitude regions of the

North Pacilic and in a belt surrounding Antarctica, diatotn

oozes cover the seafloor. The abundance and distribution of

these biogenic sediments indicate much about the fertility of

the oceans and the geochemistry of deep waters as it circulates

between the major ocean basins.

Robert G, Douglas

Bibliography

AiTcnhiLis, G.. l')52. Sediment cores from the Easi Pacific. In Swedish

Dccp-Si'ti

ExjU'ilition

Repiirts. no. 5. pp. 1 227.

AziiiTi. I-., 1998. Microbiiil coiilrol of occiinic carbon flux: tlie plot

iliickcns,

Sdi'iKf.

280: 694-696,

Barroii, E.. and Whilman. J.. 1982. Oceanic sediments in time and

space. In Emiliani, C. (cd.). The OceoiiicLithosptu-re.Tlu-Seti. John

Wiley and Sons. pp. 689 731.

Berger. W,. 1970, Biogenoiis deep-sea sediments: tVactionation by

deep-sea circulation. Gi'ohf'iatl Society of Anwriai Bulletin. 81:

1.18? 1402,

Berger. W.. 1974. Deep-sea sedimeiiUttion. In Biirk. C.A.. and Drake.

C.D, (eds,).

Tin-

Gi'dluav of

Coiitinciitiil

.Margins.

Springer-Verlag,

pp,

213 24f

Berger, W.H.. 1976. Biogenoiis deep-sea sediments: production,

preservation and interpretation. In Riley. J.. and Chester, K.

(eds.).

Chcmival (keuiw^raj'hv. Vokmie 5. Aeademic Press.

pp.

265-387.

Berger. W.. 1992. Pacifte carbonate cycles revisted: arguments for and

against productivity control. In Ishizaki. K.. and Saito. T. (eds.).

('t'litciiary .hipuiic.sc Mivropuk-ontoh^y. Tokyo: Terra Scientific

Piiblisliini; company, pp. 15-25.

Berger, W.. Smetacck.'v.. and Wcier, G. (eds.). 1989. Prodmtiritvof

the (h'l-iiii: Present iiiitt Past. Dahlem Konferen/^en LS 44. John

Wiley and Sons.

Boiima. A.H.. Normark. W.R.. and Barnes. N.F.. 1985. Suhnuirine

Eiins

and Related

Turbidite

.Systcni,\.

Springer-Verlag.

Broecker. W.S.. and Peng. T,-H.. 1982. tnucr.s

in

the

Oeean,

Columbia

University Press.

Calvert. S., 1983. Sedimentary geochemistry of silicon. In Aston. S,

(ed.).

Siticiin Geocbemistry and Bimhenii.strw Academic Press,

pp.

143 1X6.

Cronan. D.S.. 1977. Deep-sea nodules: distribution and geoehemistry.

In Glasby. G.P. (ed.). Marine Muiif-anc.se Deposit.^, Elsevier.

pp.

11 25'

Ciirray, J.R.. and Moore, D.G., 1971. Cirowth of tbe Bengal Deep-sea

fan and denudation of the Himalayas, (iealof^ieal Society nf

.America,

Bulletin. 82: 565 572.

Davies. T,. and Gorsliiie. D.. 1976. Oceanic sediments and sedimentary

processes. In Ritey. J.. and Chester. K. (eds.), Clieinieat Oeeario-

^raphy. Volume 5. .Academic Press, pp. I 80.

Dixit, S.. Van Cappcllen. P., and vart Bennekom. A,J,. 2001, Proeesses

controlling solubility of biogenic silica and pore water build-up of

silicic aeid in marine sediments. Marine Clieinistry. Volume 73.

333 352.

Diiec. R.A., Unmi, C.K.. and Riiy. B.J.. 1991. The atmospheric input

of trace species to the world ocean. Global Biinit'oihciuical Cyeles.

5:

193 259.

Ewing. M., Ludwig. W., and Ewing. J.. 1964. Sediment distribution in

the oceans: the Argentine Basin.

.Iriiiriiul

ol Genpliysicid

Re.u-arcli.

71:

1611 1636.

Falkowski. P.. Barber. R,. and Smelacek. V., 1998, Biogeochemical

controls and feedbacks on ocean primary production.

.Science.

28t:

200-205,

492

OFFSHORE SANDS

Gardner. W,. 1997, The llux of particles to the deep-se;t: methods,

measurement and mechanisms.

Oceiina^iaphy.

3:

116-121.

Garrels, R.M.. and Mackcn/ic. F.T.. 1971.

Eyohition

tifsedinientury

roek.s.

New York: W. W. Norton,

Goldberg.

E.D., 1963. Mineralogy ;tnd chemistry of marine sedimen-

tation.

In Shcpard. K.P..

Submarine

Gcnliii^y.

New York: Harper

and Row. pp. 436-466.

Grifftn,

J.J.. Windom. H,. and Goldberg,

M.V)..

1%8. The distribution

of clay minerals in the world ocean. Deep Sea

Re.setirch.

15:

433-459.

Honjo. S., 1997, The rain of ocean particles atid Earth's carbon cycle.

Oceami.s.

40: 4-7.

Honjo. S,. Dymond. R.. Collier. R.. and Mangimini. W.J.. 1995.

Export produetion of particles to tlie interior of the equatorial

Pacific Ocean during the 1992 EqPac experimenl. Deep-Sen

Re.seareh

If. 44: 831-870.

Hiimphris. S., Zicrcnbcrg, R.. Mullineau.v, L., Thotrtson. R, (eds.).

1995.

Seafioor Hydroihermal Systems. Physical. Chemical. Biolo-

gical and Geological Inlenictions.

GenphysieiilMonograph.

Volume

91,

American Cicophysical Union.

Kastner. M.,

I9HI.

Authigenic silicates in deep-sea sediments:

formation and diagcnsis. hi Emiliani. C, (cd.).

The Oceanic

Litho-

sphere,

The

Sea.

John Wiley and Sons, pp.

915-981.

Kennett. J.. 1982.

Maiine.Geolo^y.

Englewood Cliffs: Prciilicc-Hall.

Leinen.

M.. 1989. The pelagic clay province of the North Pacific

Ocean.

In Winterer. E.L., Houssong. E,M.. and Decker. R,W.

(eds.).

The

Ea.stern

Paeific Ocean and Hinmii. The

Geology

of

Nurth Aniericii. vol. ,V, Geological Society of America, pp.

323-335.

Leinin.

M.. and Pisias. N,. I9S4. An objective technique for detenning

end-member composilions and for partitioning sediments accord-

ing lo their sources.

Geachemien

El

Cosmoehimiea

.Ada.

48: 47 -62.

Lisitzin.

A., 1996.

Oceanic

Sedimentation.

Eithology

und

Geochemistry.

The American Geophysical Union,

McManus. J.. Hammond. D., Berelson. W.. Kilgore, DcMaster. T.D.,

Ragtteneau, O.. and Collier. R.. 1995. Early diagensis of biogenic

opal:

dissolution rates, kinelics and paleoceanographic itnpiica-

tions,

Deep-Sea Researeh

II, 42: 871 903

Moore, T,C. Jr.. and Heath. R.G., 1978. Sea-floor sampling

techniques. In Riley. J.. and Chester, K. (eds.).

Chemical

Oceano-

graphy. Volume 7. Academic Press, pp. 75 126.

Murray. J,, 1897. On the distribution of tbe Pelagic Foraminifera at

the surface and on the tloor of Ihe Ocean. NatunilScience.

11:

17

27.

Murray. J.. and Rcnard. A.. 1891.

Report on Deep-Sea Sediments Based

on the Specimens Colleeted during the Voyage

of

H.

M.

S.

Challenger

in

the

iear.'i

/H72-I876. Challenger Reports. London: Government

Printer.

Nelson.

D.M.. Treguer. P.. Brze/^inski. M.. Leytiacrt. A., and

Ouguiner. B.. 1995. Production and dissolution of biogenic silica

in the ocean: revised global estimates, comparison with reginoal

data and relationship to bioiienic sedimentation. Global

Bioaeo-

chemical

Cycle.

9: 359-372.

Normark. W.R.. and Piper. D.J.. 1991, Initiation process and flow

evolution of lurbldity curretits: implication for the depositional

record.

In Osborne, R.H. (ed.).

Emm .Shoreline to

Abys.\.

Society of

Seditnentary Geoloey Special Paper, 46. pp. 207-230.

Pearee, R.B.. Kemp, A.E.S.. Baldauf, J.G,. and King. S.C. 1996.

High-rcsokition seditnentology and micropaleontology of

lami-

nated diatomaceous sediments from the eastern equatorial Paeitie

Ocean (Leg 138). In Kemp. A.E.S. (ed.).

Palaeoelimatology

and

Pa-

laeoeeanography

jrimi

Eaniinated

Sediments.

Geological Society of

London.

Special Publication. I 16. pp. 221 242.

Peterson.

M,. 1966, Calcite: rates of dissolution in a Verical Profile in

the Central Pacific,

Science.

154. I 1542 11544.

Piper. D.Z., and Heath. G.R.. 1989. Hydrogenous seditnent. In

Winterer. E.L.. Houssong, E.M., and Decker, R.W. (eds,). The

Eastern

Pacific Ocean

and Hawaii. The

Geology

of North

.America.

Volume N. Geological Society of America, pp. 337-345.

Ragueneau. O.. Treguer, P.. Leynacrt. A,. Anderson, R.F., Brzezinski,

M.. DeMaster. D.J.. Dugdate, R.. Dymond. J,. Fischer. G..

Francois. R., Hcize, C. Maicr-Rcimcr. E.. Martin-Jczequel. V..

Nelson.

D.. and Qu^JgLtincr, B.. 2000. A review of the Si cycle in the

modern ocean: recent progress and missing gaps in the application

of biogenic opal as a paleoproductivity proxy. Global and Planetary

Change.

26: 317 .365.

Raitl.

R.. 1956. Seismic refraction studies of the Pacific Ocean Basin.

Part

1:

erustal thickness of the Central Equalorial Pacific,

Geologi-

cal .Soeiely

of

America

Bnlletin. 67: 1623 1640.

Rea.

D.K,. 1994. The paleoclimatie record provided by eoiian

deposition in the deep sea: the geologic history of

wind.

Reviews

of Geophysics. 32: 159 195,

Rex. R.W.. and CSoldberg. E,D.. 1968. Quartz content of pelagic

sediments of the Paeifie Oeean.

Telliis.

10: 153-L59.

Seibold.

E.. and Berger, W,H.. !996.

The Sea

Eloor An fnirodiictioii to

Marine

Geology,

Spritiger-Verlag.

SchotI,

W., 1935. Die Foraminiferen in dem Aquatorialen Teil des

Atlantischen Ozcans. Wisschafen. Ergek. Deiitsehen Atlanti.sehen

Expedition.Vernuiss. Eorschungs.schiff

Meteor.

1925 27. Volume III.

pp.

43 1.34.

Windom.

H.. 1975. Eolian contribution to marine sediments. Journal

of

Sedimentary

Petrology.

45: 520- 529.

Wiiidotii.

H.. 1976. Lithogenous material in marine sediments. In

Riley. R,. and Skirrow. G, (eds,).

Chemical

Oceanography.

Volume

5. pp. 103-135.

Winterer. F,.. 1989. Sediment thickness map of Ihe Northeast Pacific.

In Winterer. E.L,. Hussong. D.M.. and Decker. R. (eds.). The

Eastern Pacific Ocean

and Hawaii.

The Geology

of

North

Ameriea.

Volume N, Geological Society of Ameriea, pp. 307-3 iO,

Cross-references

Calcite Compensation Depth

Carbonate Mineralogy and Cieochemistry

Classification of Sediments and Sedimentary Roeks

Clathrates

Eolian Transport and Deposition

Extraterrestrial Material in Sediments

Glacial Sedimenls: Processes, Environments, and Facies

Gravity-Driven Mass Flows

Iron -Manganese Nodules

Mudrocks

Nepheloid Layer. Sediment

Neritie Carbonate Depositional Environments

Seawater: Temporal Changes lo the Major Solutes

Sediment Fluxes and Rates of Sedimentaiion

Seditnent Transport by Unidirectional Water Flows

Seditnentology; History in Japan

Sedimentologi.sts

Siliceous Sediments

Slope Sediments

Submarine Fan and Channels

Turbidites

OFFSHORE SANDS

Many middle atid outer cotitinental shelves aroutid the

world are covered, at depths frorn about

50 m

to trtorc thati

200

m.

with satid deposits, a few decimeters to more thati

50

tn

thick. These sands in'c ofteti remolded by tidal or unidirec-

tional currents and/or storms and fortn longitudinal sand

ridges (or sand banks of sotne authors) or transverse dunes.

They may also appear as large sand sheets (with or without

superimposed bed forms) forming a "sand belt" roughly

parallel to the shelf edge. Understanding these deposits

requires taking into account both present day sediment

dynamics and Late Pleistocene glacio-eustatic and sediment

flux changes.

OFFSH(JRE SANDS

493

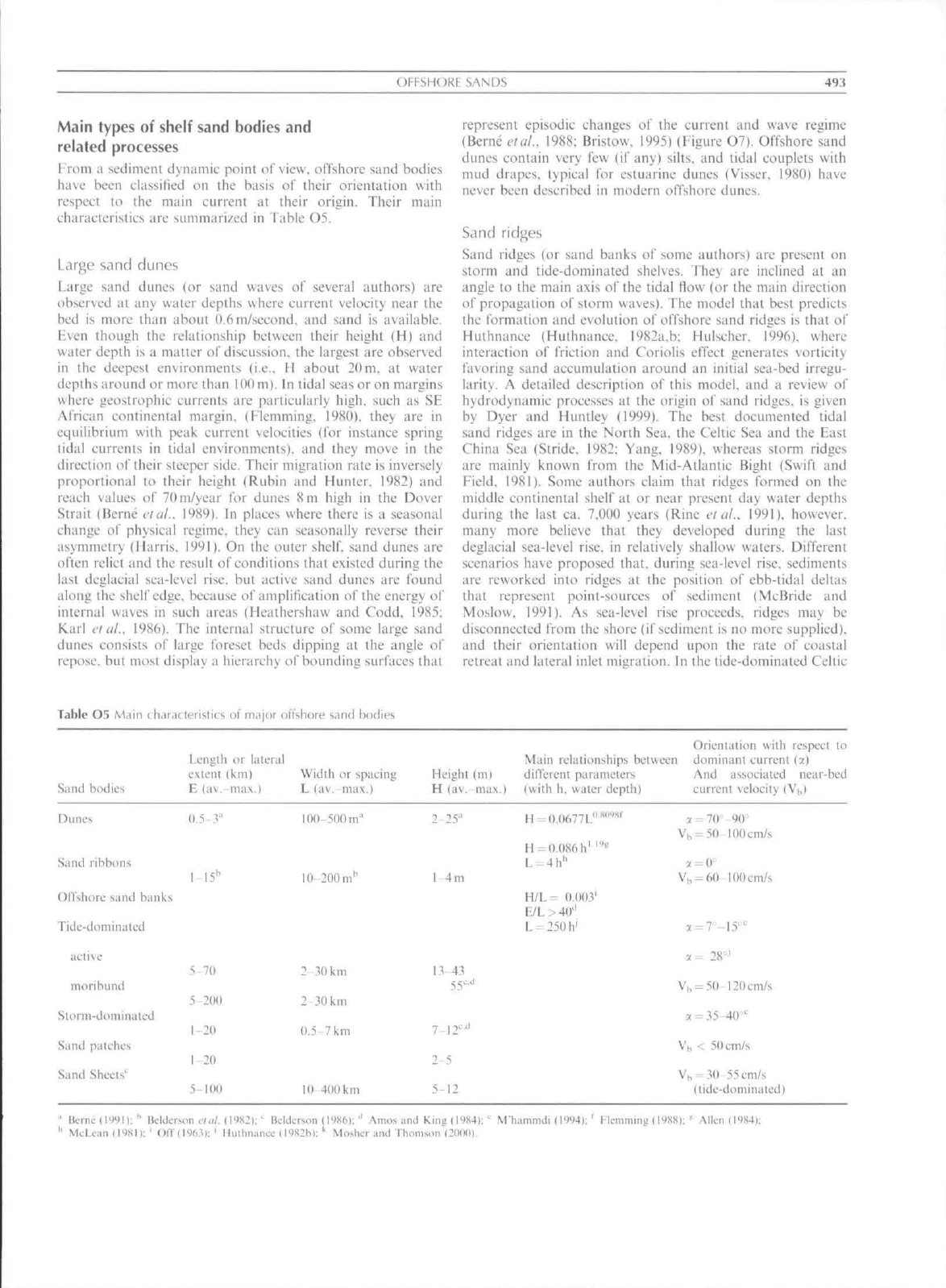

Main types

of

shelf sand bodies

and

related processes

hrom

;i

sediment dyn;iniic point

of

view, offshore sand bodies

liitve been cUissilicd

on the

basis

of

their orientation with

fcspect

to the

main current

at

their origiti. Their main

characteristics

are

summarized

in

Table

05.

Large sand dunes

Large sand dunes

(or

sand waves

of

several authors)

are

observed

at any

water depths where current velocity near

the

bed

is

more than about 0.6 m/second.

and

sand

is

available.

Even though

the

relationship between their height

(H) and

water depth

is a

matter

of

discussion,

the

largest

are

observed

in

the

deepest environtnents (i.e..

H

about 20 m.

at

water

depths aroitnd

or

tnore than lOOm).

In

tidal seas

or on

margins

where geoslrophic citrrents

are

particularly high, such

as SE

African continental margin, (Eiemtning, 1980). they

are in

equilibrium with peak current velocities

(for

instance spring

tidal currents

in

tidal environments),

and

they move

in the

direction

of

their steeper side. Their tnigration rate

is

inversely

proportional

to

their height (Rubin

and

Hunter.

1982) and

reach values

of

7()m/year

for

duties

8

m

high

in the

Dover

Strait (Berne

etaf.

1989).

In

places where there

is a

seasonal

change

of

physical regjtne. they

can

seasonally reverse their

asymtnetry (Harris, 1991).

On the

outer

shelf,

sand dunes

are

often relict

and the

result

of

conditions that existed during

the

last deglacial sea-level rise,

but

aettve sand dunes

are

found

along

the

shelf edge, because

of

atnplification

of the

energy

of

internal waves

in

such areas (Heathershaw

and

Codd.

19S5:

Karl

ft af.

1986).

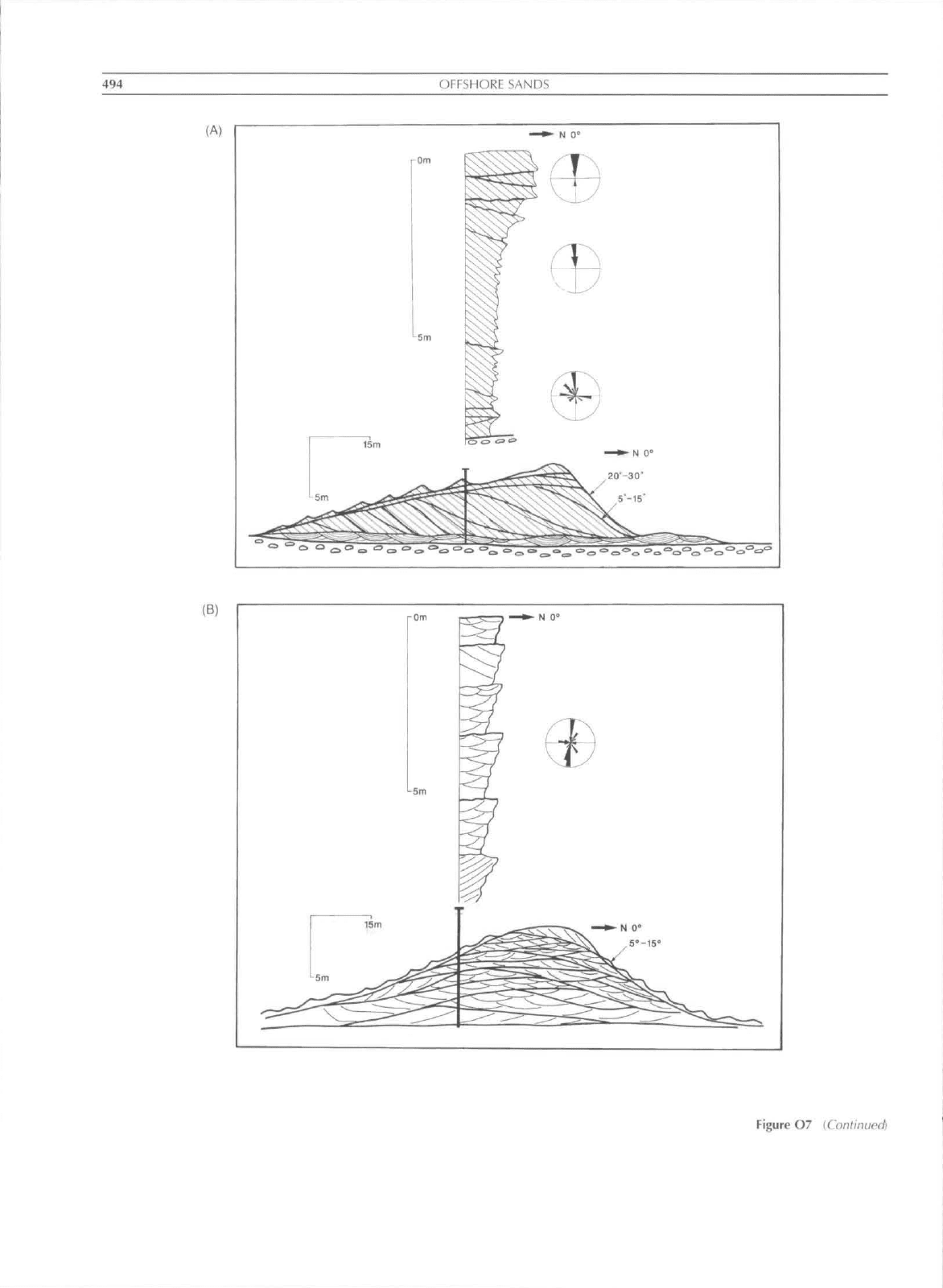

The

intet"nal structure

of

some large sand

dttncs consists

of

large forcset beds dipping

at ihe

angle

of

lepose.

but

tnost display

a

hieratchy

of

bounding surfaces that

represent episodic changes

of the

eurrent

and

wave regitne

(Berne cKiL.

1988;

Bristow,

1995)

(Figure

07),

Offshore satid

dunes contain very

few (if any)

silts,

and

tidal couplets with

mud drapes, typieal

for

estuarine dunes (Visser,

1980)

have

never been described

in

modern offshore dunes.

Sand ridges

Sand ridges

(or

sand banks

of

some authors)

are

present

on

storm

and

tide-domitiated shelves. They

are

inclined

at an

angle

to the

tnain axis

of the

tidal flow

(or the

main direetion

of propagation

of

storm waves).

The

model that best predicts

the formation

and

evolution

of

offshore sand ridges

is

that

of

Huthnance (Huthnance. I982a,b: Hulscher, 1996). where

interaction

ol"

friction

and

Corioiis effect generates vorticity

favoring sand accumulation around

an

initial sea-bed irregu-

larity.

A

detailed description

of

this tnodel.

and a

review

of

hydrodynatnic processes

at the

origin

of

sand ridges,

is

given

by Dyer

and

Huntley (1999).

The

best docutnented tidal

sand ridges

are in the

North

Sea, the

Celtic

Sea and the

East

China

Sea

(Stride,

1982:

Yang, 1989). whereas storm ridges

are mainly known from

the

Mid-Atlantic Bight (Swift

and

Field, 1981), Some authors claim that ridges formed

on the

middle continental shelf

at or

near present

day

water depths

during

the

last

ca.

7,000 years (Rine elal.. 1991), however,

many more believe that they developed during

the

last

deglaeial sea-leve! rise,

in

relatively shallow waters. Different

scenarios have proposed that, during sea-level rise, sediments

are reworked into ridges

at the

position

of

ebb-tidal deltas

that represent point-sources

of

sediment (McBride

and

Moslow. 1991).

As

sea-level rise proceeds, ridges

may be

disconnected frotn

the

shore

(if

sediment

is no

more supplied),

and their orientation will depend upon

the

rate

of

coastal

retreat

and

lateral inlet migration.

In the

tide-dominated Celtic

Table

O5 M.iin

iJi,ir,K Icristics

ni

major otTshore sand bodies

Sand bodies

Length

i)r

lateral

extent

(km)

Widtli

or

spacing

E (av,-iTia\,)

L (av. max.)

with respect

to

Main rclntioiiships between dominani curretu

(5:)

Height

(ml

dilTerent parameters

And

associated near-bed

H

(av. max.)

(with

h.

water depth) etirrent velocity

(V^l

Dunes

Sand rihbons

Olfshore sand banks

Tide-dominated

0.5-.V'

I00-500m'

i 0-200

m"

2 25^'

l-4m

H

-

0.086

h' '"^

H/L= 0.003'

E/L>40''

a

=

70

9()-

Vh-50-lOOcm/s

= 60-l00em/s

Storm-dominated

Siuid palthcb

Sand Sheets'"

5-70

5

2(H}

1-20

1

20

5-100

2-30 km

2 30 km

0.5-7 km

10-400 km

13-43

2-5

5-12

,

= 5(l-l2Ocm/s

,

<

50cm/s

,

=

30

55

ctn/s

(tide-dominated)

•' UernellWl):

^

ikUiersnn el,it.{\9H2):

•-

Bddcrson (19Hf.);'*

Amo^ and

Kinj? (I9S4|;

^'

M'hammdj (1994|:

'

FlemmJng (I9N8);

^

Allen [I9S4|:

''

ML-LLMII (I'IHI);

'

0(1(196.1):

'

Hullmancc ll9R2hl:

*•

Masher

and

Thomson COIIO).

494

OFFSHORE SANDS

(A)

N 0"

(B)

Figure O7 [Continued)