Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

OFFSHORE SANDS

495

(C)

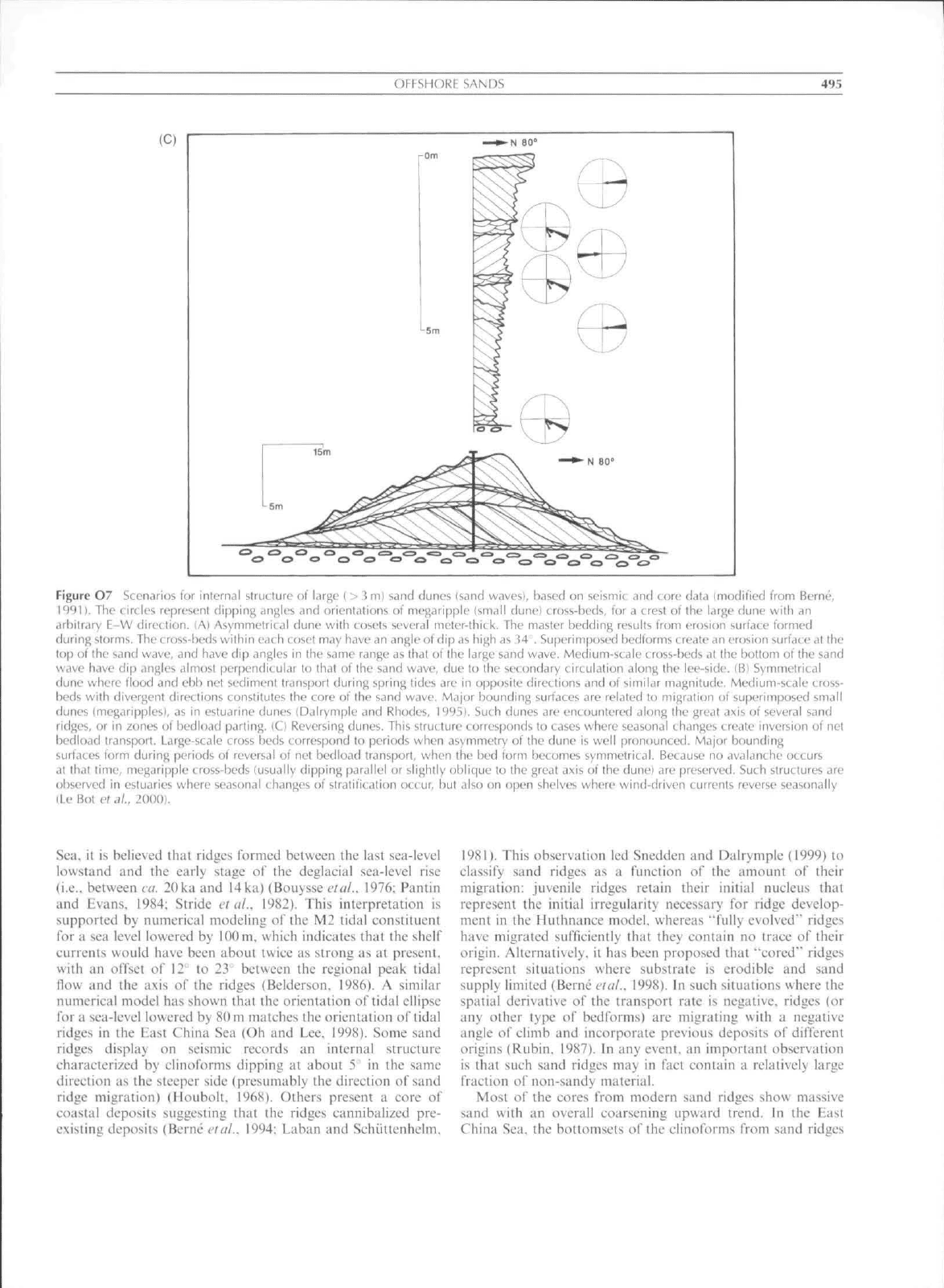

Figure O7 Scenarios lor interriiil structure ot' large ( >

3

ml sand dunes (sand waves), based on seismic anci (.ore data (modified from Berne,

1991). The circles represent Hippinji angles and orientations of mej^aripple (small dunel cross-beds, for a crest of the lar^e dune with an

arbitrary E-W direction. lAl Asymmetrical dune with cosets several meler-thjck. The master beddinj; results from erosion surface formed

during

slorms.

Tbe cross-beds within each coset may have

cin

an^^leof dip as hif"h as 34 . Superimposed bedforms create an erosion surface M the

t()[} of the sand wave, and have dip angles in the same range as that ot the large sand wave. Medium-scale cross-beds at the bottom of the sand

wave have dip angles .ilmost perfiendicular to that of the sand wave, due to the secondary circulation along the lee-side, (B) Symmetrical

dune where llood and ebb net sediment tr<ins[)ort during spring lides are in opposite directions and of simiiar magnitude. Medium-scale cross-

beds with divergent directions constitutes the core of the sand wave. Major bounding surfaces are related to migration of superimposed small

dunes (megaripplesi, as in estuarine dunes iDalrymple and Rbodes,

I

995|. Sucb dunes are enc:ountered along the great axis of several sand

ridges, or in zones of beriload parting. (C) Reversing dunes. This structure corres[)onds lo cases where seasonal changes create inversion of net

bedload transport. Large-scale cross beds correspond to periods when asymmetry of the dune is well pronounced. Major bounding

surtaces form during periods of reversal of net bedload transport, when the bed form becomes symmetrical. Because no avalanche occurs

at that time, megaripple cross-beds (usually dipping parallel or slightly oblique to the great axis of the dune) are preserved. Such structures are

observed in estuaries where seasonal changes of stratilication occur, hut also on open shelves where wincJ-rlriven t urrents reverse seasonally

ae Bot

et.il.,

2001)1.

Sea, il is believed that ridges formed between the last sea-level

lowstatid and the early stage of the deglacial sea-level rise

(i.e.,

between ca. 20ka and 14ka) (Bouysse etui.. 1976; Pantin

atid Evans, 1984; Stride etal.. 1982). This interpretation is

supported by numerical modeling of the M2 tidal constituent

for a sea level lowered by 100 m, which indicates that the shelf

currents would have been about twice as strong as at present,

with an offset of 12" to 23' between the regional peak tidal

flow and the axis of the ridges (Belderson, 1986). A similar

numerical tiiodcl has shown that the orientation of tidal ellipse

for a sea-level lowered by 80 m matciies the orientation of tidal

ridges in the Hast China Sea (Oh and Lee. 1998), SotTie sand

ridges display on seismic records an internal structure

characterized by clinoforms dipping at about 5 in the same

direction as the steeper side (presutnably the direction of siind

i-idgc migratioti) (Houbolt. 1968), Others present a core of

coastal deposits suggesting that the ridges cannibalized pre-

existing deposits (Berne elal.. 1994: Laban and Sehiittenhelni,

1981).

This observation led Snedden and Dalrymple (1999) to

elassify sand ridges as a function of the amount of their

tnigration: juvenile ridges retain their initial nucleus that

represent the initial irregularity necessary for ridge develop-

ment in the Hitthnance model, whereas "fully evolved"" ridges

have tiiigrated sufftciently that they contain no trace of their

origin. Alternatively, il has been proposed that "cored" ridges

represent situations where substrate is erodible and sand

supply litrtited {Bernd etal., 1998). In such situations where the

spatial derivative of the transport rate is negative, ridges (or

any other type of bedforms) are migrating with a negative

angle of elimb and incorporate previous deposits of different

origins (Rubin, 1987). In any event, an important observation

is that such sand ridges may in fact contain a relatively large

fraction of non-sandy tTtaterial.

Most of the eores frotn tnodern satid ridges show massive

sand with an overall coarsening upward trend. In the East

China Sea, the bottomsets of the clinoforms from sand ridges

496 OFFSHORE SANDS

lying

at

about 90 tn display alternating sand

and

silt bedding

with burrowed tidal rhythmites, whereas

the

(opsets consist

of

homogeneous tine

to

medium sand (Bcrnc etal.. 2002). Cores

from

the

Middelkcrke bank

in the

North

Sea

show,

in the

upper part

of the

ridge, ripple

to

medium dune bedding, with

some herringbone cross-beds (Trentesaux

et al..

1999).

The

lower part

of the

bank consists

of

estuarine sediments

incorporated into

the

ridge.

Lowstand

and

transgressive shorefaces

and delta fronts

In areas where erosion

due to

wave

and

tidal ravinement

is

limited, shoreface deposits

and

sandy delta fronts that formed

at period

of

lower sea-level tnay

be

preserved

and

represent

another type

of

offshore sand bodies, where

the

initial

geometry

is

only partly preserved.

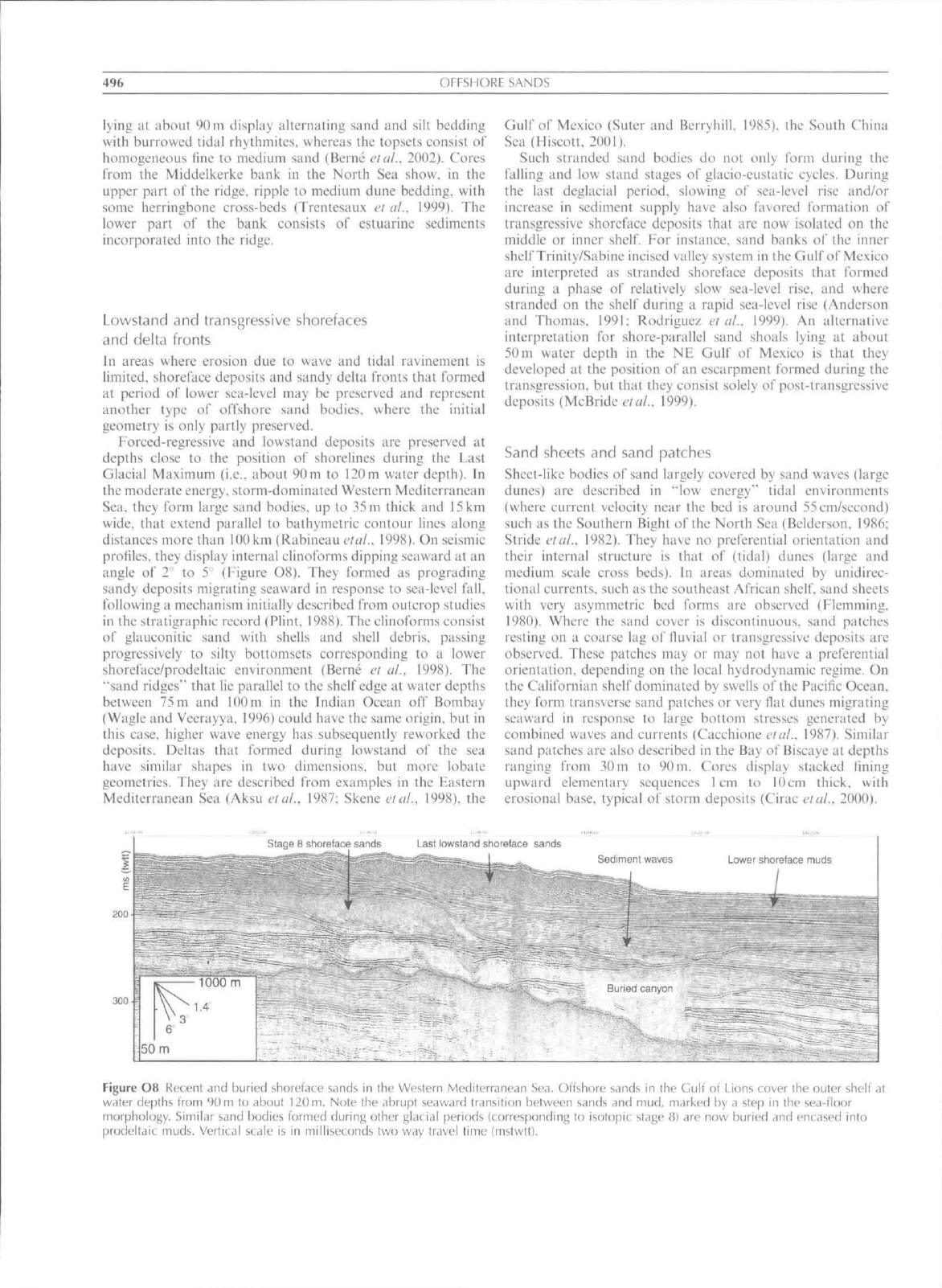

Forced-regressive

and

lowstand deposits

are

preserved

at

depths close

to the

position

of

shorelines during

the

Last

Glacial Maximum (i.e.. about 90tn

to I2()m

water depth).

In

the moderate energy, stortn-dotninated Western Mediterranean

Sea, they form large sand bodies,

up to

35

m

thick

and

15

km

wide, that extend parallel

to

bathymetrie contour lines along

distances more than 100km (Rabineau ctai.. 1998).

On

seistnic

profiles, they display internal clinoforms dipping seaward

at an

angle

of 2 to 5'

(I'igurc

08).

They fortned

as

prograditig

sandy deposits tnigrating seaward

in

response

to

sea-level fall,

following

a

mechanism initially described from outcrop studies

in

the

stratigraphie record (Plint, 1988).

The

clinoforms consist

of glauconitic sand with shells

and

shell debris, passing

progressively

to

silty bottomsets corresponding

to a

lower

shoreface/prodeltaic etivirontiient (Berne

et af.

1998).

The

"sand ridges'" that

lie

parallel

to the

shelf edge

at

water depths

belween

75m and 100m in the

Indian Ocean

off

Bombay

(Wagie

and

Veerayya. 1996) could have

the

same origin,

but in

this ease, higher wave energy

has

subsequently reworked

the

deposits. Deltas that formed during lowstand

of the sea

have simiiar shapes

in two

dimensions,

but

more lobate

geometries. They

are

described from examples

in the

Eastern

Mediterranean

Sea

(Aksu etal..

1987;

Skene

etitf,

1998),

the

Gulf

of

Mexieo (Suter atid Berryhill, 1985),

the

South China

Sea (Hiscoti, 2001).

Such stranded sand bodies

do not

only form during

the

falling

and low

stand stages

of

glacio-eustatic cycles. During

the last deglacial period, slowing

of

sea-level rise and/or

increase

in

seditnent supply have also favored lortnation

of

tratisgressive shoreface deposits that

are now

isolated

on the

tniddle

or

inner

shelf. For

instance, sand banks

of the

inner

shelf Trinity/Sabine incised valley system

in the

Gulf

of

Mexieo

are interpreted

as

stranded shoreface deposits that formed

during

a

phase

of

relatively slow sea-level rise,

and

where

stranded

on the

shelf during

a

rapid sea-level rise {Anderson

and Thotnas,

1991;

Rodriguez

el af.

1999).

An

altertialive

interpretation

for

shore-parallel sand shoals lying

at

about

50m water depth

in the NC

Gulf

of

Mexico

is

that they

developed

at the

position

of an

escarpment formed during

the

transgression,

but

that they consist solely

of

post-transgressivc

deposits (McBride

ciaf,

1999).

Sand sheets

and

sand patches

Sheet-like bodies

of

sand largely covered

by

sand waves (large

dunes)

are

described

in "iow

energy" tidal environments

(where current velocity near

the bed is

around

55

cm/second)

sttch

as the

Southern Bighi

of the

North

Sea

(Belderson.

1986:

Stride

ctaf.

1982). They have

no

preferential orientation

and

their internal structure

is

that

of

(tidal) dunes (large

and

mediutn seale eross beds).

In

areas dominated

by

unidirec-

tional currents, such

as the

southeasl African

shelf,

sand sheets

with very asymmetric

bed

fortns

are

observed (Flemming,

1980).

Where

the

sand cover

is

discontinuous, sand patches

resting

on a

coarse

lag of

fluvial

or

transgressive deposits

are

observed. The.se patches

may or may not

have

a

preferential

orientation, depending

on the

loeal hydrodynamic regitne.

On

the Caiifornian shelf dominated

by

swells

of

the Pacific Ocean.

they form transverse sand patches

or

very flat dunes migrating

seaward

in

response

to

large bottom stresses generated

by

eotnbined waves

and

currents (Cacchione

etaf.

1987). Similar

sand patches

are

also described

in the Bay of

Biscaye

at

depths

ranging from 30 m

to

90 m. Cores display stacked fining

upward elementary sequences I

cm to 10em

thiek, with

erosional base, typical

of

storm deposits (Cirac

elaf.

2000).

Stage

6

shoreface sands

Last lowstand shoreiace sands

Figure O8 Recent and buried shoreface sands in (ho Western Mediterranean Sea. Offshore sands in ihe Ckilf of Lions cover the outer shelf at

water depths from *)()m lo about 12t)m. Note ihe abrupt seaward transition hetween sands and mud, marked hy a step in the sea-floor

morphology. Similar sand bodies formed during other gla< iai periods Icorresijonding lo isotopic stage 8] are now buried and encased into

prodeltaic muds. Vertical scale is in milliseconds two way travel time (mstwtt).

OHFSHORE SANDS

497

(A)

100

150

200

Ui

E

250

1

km

(B)

m.f.S-

5-15m

"foresets"

fine to

medium

well-sorted

X-bedded

sand

2-5m

"bottomsets"

I

coarse lag

bioturbated

tidal

rhythmites

silt and

sand

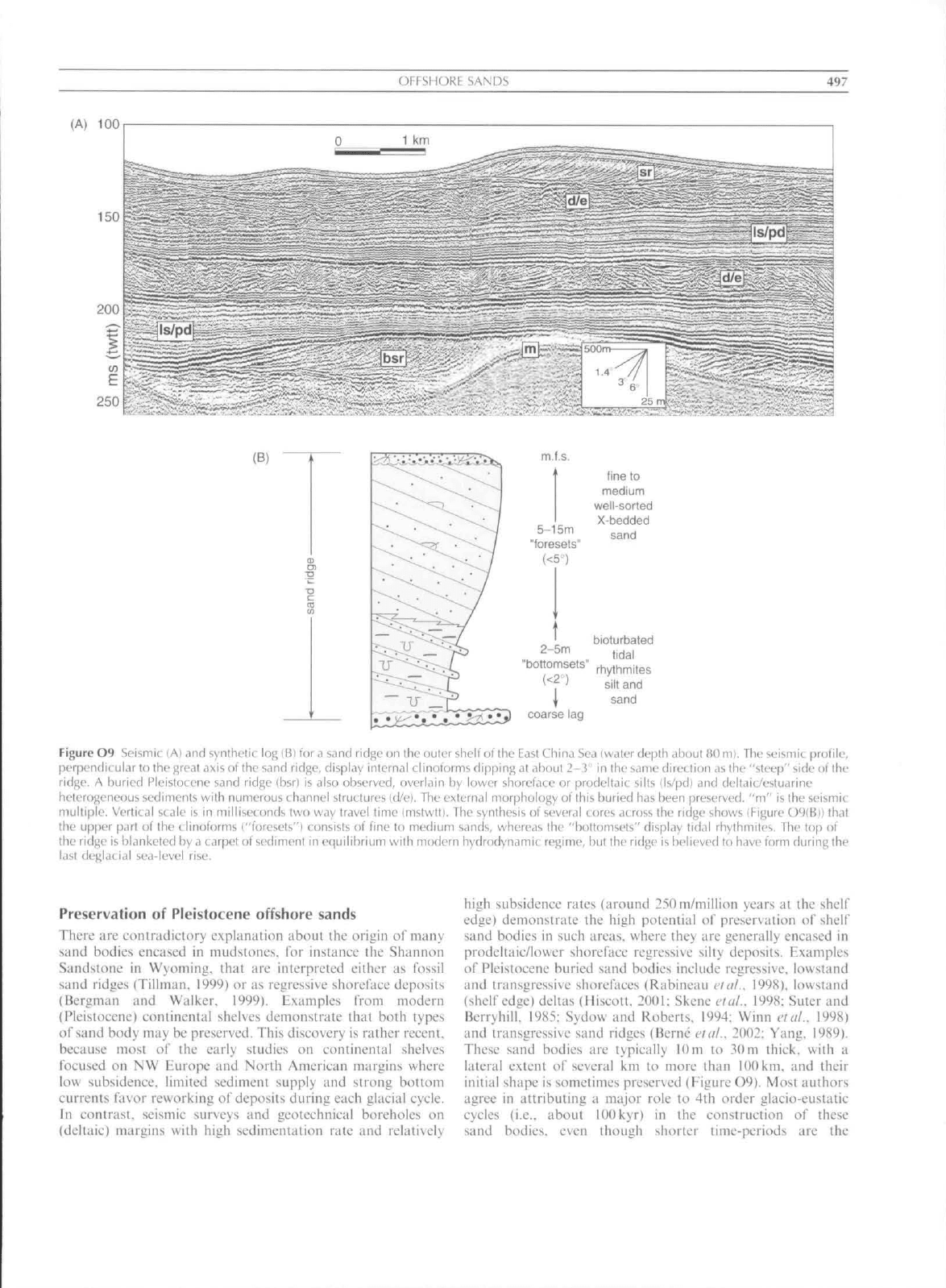

Figure O9 Seismic (Al <incl synthetic log lUl for a sand rid^e un the outer shelf of the EasI China Sea (water depth about JiOmj. The seismic profile,

ptTfjendii ular lo thej^reat axis of the sand ridj^e, display ititernal clinoforms dipping al alwut 2-3 ' in the same direction

as

the "steep" side of the

ridge.

A buried Pleistocene sand ridge Ibsri is also observed, overlain by lower shorefate or prodeltaic silts (ts/pdi and deltaic/estuarine

heterogeneous sedimenls with numerous channel structures (d/e). The exiernal morphology of this buried has been preserved, "m" is the seismic

multiple.

Vertical senile is in milliseconds two way travel time (mstwHi. The synthesis of several tores across the ridge shows (Figure O9(B)I thai

Ihe upper parl of the clinoforms i"foresets") consists of fine to medium sands, whereas Ihe "bottomsets" display tidai rhythmites. The top of

the ridge is blanketed by a carpet t)f sediment in equilibrium with modern hydrodynamic regime, but the ridge is believed lo have form during the

last deglacial sea-level rise.

Preservation

of

Pleistocene offshore sands

There

are

contiacjiclory explanation aboin

the

origin

of

many

SLttid bodies encased

in

mudslones.

for

instance

the

Shatinon

Sandstone

in

Wyoming, that

are

interpreted cither

as

fossil

sand ridges (Tillman.

1999) or as

regressive shoreface deposits

(Bergman

and

Walker. 1999). Examples from tnodern

(Pleistocene) cotitinental shelves demonstrate that both types

of sand body

may be

preserved. This discovery

is

rather recent,

beeause tnost

of the

early stitdies

oti

continental shelves

focused

on NW

Europe

and

North American tnargins where

low subsidence, limited seditnent supply

and

stt"ong bottom

currents favor reworking

of

deposits during each glacial cycle.

Iti contrast, seismic surveys

and

geotechnical boreholes

on

(deltaic) margins with high sedimentation rate

and

relatively

high subsidence rates (around 25ntn/miliion years

at the

shelf

edge) demotistrate

the

high potential

of

preservation

of

shelf

sand bodies

in

such areas, where they

are

generally encased

in

prodeltaic/lowcr shoreface regressive silty deposits. Kxamples

of Fleistoeene buried sand bodies include regressive, lowstand

and transgressive shoref^aces (Rabineau

etaf.

1998). lowstand

(shelf edge) deltas (Hiscott. 2001: Sketie

vtaf.

1998; Suter

and

Berryhill.

19S5;

Sydow atid Roberts,

1994:

Winn

etaf. 1998)

and transgressive sand ridges (Berne

eutf.

2002: Yang, 1989).

These sand bodies

are

typically

lOm (o .'^Om

thick, with

a

lateral extent

of

several

km to

tnore than 100 ktn.

and

their

initial shape

is

sotiietimes preserved (Figure

09).

Most authors

agree

in

attributing

a

major role

to 4th

order glacio-eustatic

cycles

(i.e..

about lOOkyr)

in the

construction

of

these

sand bodies, even though shorter titne-periods

are the

498

OrrSHORE SANDS

domiiiiinl lactors controlling

Iht:

iip-hiiilding

of

tniiisgressive

parnsequcnces.

Serae Berne

Bibliography

Aksu,

A.E.,

Piper. D.J.W..

and

Konuk.

T.. 1987.

Late Quaternary

tectonic

and

sedimentary history

of

outer Izmir

and

Candarli Bays.

Western Turkey. Marim-Cn-otogy.

76:

89-i

1)4.

Allen. J.R.L.. 1984. Printiptesof PhysicatScditneiitolngy. George Allen

& Unwin.

Amos,

CL., and

King,

E.L..

1984. Bedfotms

of

the Canadian eastern

seaboard:

a

comparison with global occurences. Marine Geotos,\\

57:

167 208.

Anderson. J.B..

and

Thomas.

M.A..

1991. Marine ice-sheet decoupling

as

a

mechanism

lor

rapid, episodic sea-level change:

the

record

of

sueh events

and

their influence

on

sedimentation. Scdinieniary

Geology.

70:

87-104.

Bcldcrson.

R.H.. 1986.

OITshorc tidal

and

non-tidal sand ridges

and

sheets: differences

in

morphology

and

hydrodynamic setting.

In Knight,

R.J.. ;md

McLean,

J.R.

(eds.). Slietf Sands

and

Sand-

stones. Canadian Society

of

Petroleum Geologists, Calgary,

pp.

293

.101.

Belderson. R.H.. Johnson. M.A..

and

Kenyon, N.H.. 1982. Bcdfomis.

In Stride, A.H. (ed.). OffshoreTiitalSands. London: Chapman

and

Hall,

pp.

27-57.

Belderson,

R.H.,

Pingree.

R.D.. and

Griffiths;.

D.K.. 1986. Low sea-

level lidal origin

of

Celtic

Sea

sand banks- Evidence from nume-

rical modelling

of M2

lidal streams. Marim.'Geology. 73: 99-108.

Bergman.

K.M., and

Walker.

R.G.. 1999.

Campanian Shannon

sandstone:

an

example

of a

falling stage systems tract deposit.

In

Bergman,

K.M., and

Snedden,

.I.D.

(eds.). Isolated Stiallow

Marine Siind

Bodies:

Sequence Stratigraphie Analysis and Sedinu-nto-

lof^iv Interpretation. SEPM (Society

for

Sedimentary Geoloay).

pp.

85 93.

Berne,

S.,

1991,

Arehiteetiire

F.I

Dynamii/i/e Des Dunesfiiltite.s. Exemptes

De

La

Miirgi'Atlantiqiie

Frtnieai.se.

unpublished

PhD

Thesis, Lille.

295p,

Berne,

S.,

Allen,

G,.

AulTrel.

.I.P.,

Chamley,

H.,

Durand.

J.. and

Weber,

O..

1989. Essai

desyutti'e.'iesnrles

dnues

hydrauliqiiesf'i'aute.s

tidales acliieltcs. Bnttetin

de ttt

Soeii'te Geologiqtie

de

France,

6:

1145-1160.

Berne,

S,,

Auffret.

J.P., and

Walker,

P., 1988.

Internal structure

of

subtidal sand waves revealed

by

high-resolution seismic rellection,

SeJinicntoliigy.

35: ."^ 20.

Berne,

S.,

Lericolais.

G.,

Marsset,

T,,

Bourillet,

,I,F.,

imd de

Baiist,

M.,

1998.

Erosional shelf sand ridges

and

lowstand shorefaces:

examples from tide

and

wave dominated environtnents

o(

France.

Journal of Sedimentary Researeh.

68

(4): 540-555.

Berne,

S..

Trenlesaux.

A.,

Stolk,

A..

Missinen,

T.. and De

Batist,

M..

1994.

Arcliitccturc

and

long-term evolution

of

a

tidal sandbank:

the

Middelkerke Bank. Sotithem North Sea.

Miiritie

Geology.

121: 57-12.

Berne,

S..

Vagner,

P..

Guichaid.

F..

Lericolais,

G.. Liu. Z.,

Trentesaux.

A.. Yin, P., and Yi, H.L.

2002, Pleistocene foreed

regressions iuid tidal sand ridges

in the

East China

Sea.

Marine

Gcotogy. 188(3-4): 293-315.

Bouysse,

P.,

Horn,

R..

Lapierre,

F., and Le

Lann,

F.,

1976. Etude

des

grands banes

de

sable

du

Siid-Est

de la Mer

Ccltique. .Marine

Geology.

20: 251 275.

Bristow,

C.S., 1995.

Internal geometry

of

ancieni tidal bedforms

revealed using ground peneiraling radar.

In

Flemming, B.W, (ed.),

3rdInternutiomd

Researeh

Symposium

on

Modern and

.Ancient

Clastic

Tidid Deposits: Tidal chisties

92.

Wilhetmshaven: International

Association

of

Sedimentologists,

pp, 313 328,

Cacchione,

D.A.,

Field,

M.E..

Drake.

D.E.. and

Tate,

G,B., 1987.

Crcscentic dunes

on the

inner continental shelf

off

northern

California. Geology. 15: 1134-1137.

Cirac,

P.,

Berne.

S..

Castaing,

P., and

Weber.

O..

2000. Processus

de

mise enplace

et

d'evolution

de la

couverture sedimcntaire super-

ticielle

de la

plaie-forme nord-aquitaine. Oceanohiiiea

Ada. 23:

663-686.

Dalrytnplc. R.W..

and

Rhodes,

R.N,,

I99.i. Estuarinc dunes

and

bars.

In Perillo. G.M.F. (ed,), Geomorphology

and

Sedimentology

of

Estuaries. Elsevier,

pp, 359 422.

Dyer.

K.R.. and

Huntley,

D.A..

1999.

The

origin, classification

and

modelling

of

sand banks

and

sand ridges. Couiinvntnl Shelf

Reseanlu\9my.

1285 1330.

Flemming,

B.W.,

1981). Sand transport

and

bedfbrm patleins

on the

continental shelf between Durban

and

Port ElizabL'lh (southeast

African continental margin). Sedimentary Geology.

26:

179-205.

Flemming,

B.W.,

19K8.

Zur

klassilikation siibaquatischer. stromung-

slransversaler Transportkorper. Boetnimer Geotogisclie

Und

Geo-

technischc

.•\rheiten.

29: 44 47.

Harris.

P.T.,

1991. Reversal

of

subtidal dune asymmetries caused

by

seasonally reversing wind-driven currents

in

Torres Strait, norih-

eastern Australia. Continental Shell Research. 11(7):

655 662.

Heathcrshau, A.D..

and

Codd. J.M.. 1985. Sandwaves. internal waves

and sediment mobility

at the

sheif-edsie

in ihe

(\'iiic

Sea.

Oceano-

logicaActa.S: 391

402.

Hiscott, R,N,,

2001.

Deposilional sequences controlled

by

high rates

of

sedimeni supply, sea-level variations,

and

growth faulting:

the

Quaternary Baram Delta

of

northwestern Borneo. Marine Geology.

175(1 4):

67 102.

Houbolt. J.J.H.C., 1968. Recent sediments

in

the Southern Bight

of

the

North

Sea.

Geologie en

Mijnhouw. 47(4): 245-273.

Hulscher, S.J.M.H..

1996,

Tide-induced large-scale regular bedform

patterns

in a

three-dimensional shallow water model, .hnirnal

oj

Geophyiieat Research. 101: 20727 20744.

liuihnance,

J.M.,

1982a.

On one

mechanism forming linear sand

banks.

Estuarine. Coastal ttnd Shell Science.

14: 279 299,

Huthnance,

J.M.,

1982b.

On the

formation

of

sand banks

of

finite

extenl. Estuarine. Coa.stal and Shelf Science. 15:

277 299.

Karl, ll.A., Cacchione,

D.A., and

Carlson.

P.R.,

1986. Ititernal-wave

currents

as

mechanism

to

account

for

large sand waves

in

Navarinsky Canyon head. Bering

Sea.

Journat

ol

Sedimeniarv

Petrology. 56(5): 7116-714,

Laban,

C, and

Schiittenhclm. R.T.F., 1981. Some new evidence

on the

origin

of the

Zealand ridges.

In Nio, E.D.,

Schiiuenhelm, R.T.K,,

and

Van

Veering, T.C.E. (eds.), Hotocene Marine Scilimcntiitinn

in

the

North

Sea

Basin.

Special Publication

5.

International Association

of Sedimenlologisis.

pp, 239 245,

Le

Bot. S.,

Herrnan,

J,P.,

Trentesaux,

A..

Garlan,

T.,

Bernc',

S., and

Chamley,

H.,

2000. influence destempetes

sur la

mobiiitedcs dunes

tidales dans

le

detroit

du

Pas-de-Calais. Oceanologica Acta. 23(2):

129-141.

M'hammdi,

N., 1994,

Architecturedn Bane

.Sahleit.x

Tidal De Serci/ dies

anglo-norniandes).

PhD

Thesis, Universite

dc

Lille

1,

Laboratoire

de Sedimentologie

et

Tectonique. Lille, 2l).'^pp,

McBride.

R.A.,

Anderson,

L.C.,

Tudoran,

.\.. and

Roberts,

11.11..

1999.

Holocene stratigraphic archileclure

of a

sand-rich shelf

and

the origin

of

linear shoals: noriheaslern Gulf

of

Me.xico.

In

Bergman.

K.M., and

Sncddcii.

J.W.

(eds.). Isolated Shatter .Marine

Sand

Bodie."^:

Seqnenee Stratignipliic .Analysis

and

Sedimentotogic

Intcrpreiation. SFPM Special Publication. Tulsa: Society

for

Sedimentary Geoplogy (SEPM).

pp.

95-f26.

McBride.

R.A.. and

Moslow,

T.F.. 1991.

Origin, evolution,

and

distribution

of

shorefaee sand ridges, Atlantic inner

shelf.

USA.

Marine Geology.

97:

57-85,

McLean.

S.R.. 1981. The

role

of non

uniform roughness

in the

fomiation

of

sand ribbons. Marine Geology.

42:

49-74.

Mosher.

D,C,. and

Thotnson,

R.E,,

2000, Massive submarine sand

dunes

in the

eastern Juan

dc

Euca Strail, British Columbia.

In

Tentesaux,

A., and

Garlan,

T.

(eds.). Marine Sandnave Dynamics.

Eraiice: University

of

Lille,

pp, 131 142.

Off.

T,,

1963. Rhythmic linear sand bodies caused

by

tidal currents.

.4merieaii Assoeiation

of

Petroleum

Geologi.sts

Bid let

in.

Al\

324-341.

Oh,

S.L, and Lee, D,E.,

1998. Tides

and

tidal currents

of the

Yeiiow

and East China Seas during

the

last 13,000 years, Joiirnol

oJ

the

Korean .Soiiety of Oceanography. 33 (4): 137-145.

Pantin. 11.M..

and

Evans. CD.R.. 1984. The Quaternary history

ot the

Central

and

Southwestern Celtic

Sea.

Marine Geologv.

57:

259

293.

Plint.

A.G.. 1988.

Sharp-based shoreface seqtienccs

and

"offshore

bars"

in the

Cardium Formation

of

Alberta: iheir relationship

to

relative ehanges

in sea

level.

In

Wilgus,

C.K,

etui, (eds,), Sea-levet

oil SANIXS

499

CliiingL's:

.4n Integrated

.Approach.

SEPM Special Publication,

42,

Ttilsa,

pp. 357 370,

Rabineau.

M.,

Berne.

S., Le

Drezen,

E..

Lericolais,

G.,

Marsset,

T.,

and Rotunno.

M.. 1998. 3D

architecture

of

lowsland

and

transgressive Quaternary sand bodies

on the

outer shelf

of ihe

Gulf

of

Lion. Erance. Marine atid Pelrolenm Geology.

15 (5):

439

452,

Rine,

J.M.,

Tillman, R,\V.. Culver.

S.J.. and

Swift, D.J.P.,

1991.

Generation

of

late Holocene sand ridges

on the

middle continenlal

shelf

of New

Jer.sey. L'SA-evidence

for

formation

in a

mid-shelf

setiine based

on

comparison with

a

nearshore ridiie.

In

Swift,

D,J.P"!. Oertel. G.F.. Tiltman. R.W..

and

Thorne.

J.A"^

(eds.),

.SItetJ

Sand

and

.Sandstone Bodies: Geometry. Faeies

and

Sapienee

Stratigraphy. (Jlackwell.

pp.

395-423.

Rodriguez,

A.B.,

Anderson,

J.B.,

Siringan,

1\P., and

Taviani,

M.,

1999.

Sedimentary Eitcies

and

Genesis

of

Holocene Sand Banks

on

ihc Easi Texas Inner Continental

Shelf:

Isolated Shallow Marine

Sand Bodies.

In

Bergman. K.M..

and

Snedden, J.W. (eds.). Isotated

Shaltow Marine Saml Bodies: Sequenee Siratigraphic

.-tiiiilysis

and

Sedimentiitogie Interpretation. SEPM (Society

for

Sedimenlary

Geology). Special Publication,

pp. 165 178.

Rubin,

\yU..

19S7. Cross-Bedding. Bedforms.andPateocurreim. SEPM

Concepts

in

Sedimentology

and

Paleontology Series

3.

Rubin. D.M.,

and

Hunter. R.E.. 1982. Bedform climbing

in

theory

and

nature. Sedimentohn^y.

29: 121 138,

Skene.

K.L.

Piper, D.J.W., Aksu,

A.E., and

Syvitski, J.P.M..

1998.

E\akiaiion

of the

global oxygen isotope curve

as a

proxy

for

Oualernary

sea

le\el

by

modeling

of

delta progradaiion. JoionaloJ

Sedimenta'rv Researeh.

dS

{f^y.

1077

|()92.

Snedden. J.W.,'

and

Dalrymple,

R.W.,

1999. Modern shelf sand ridges:

irom historical perspective

lo a

unified hydrodynamic

and

evolutionary model.

In

Bergman.

K.M.. and

Snedden.

J.W.

(eds.),

Isolated Shattow

.Marine

Sand Bodies: Sequenee Slratigraphie

Analysis

and

Sedimentologie Inlerpretation. SEPM (Society

for

Sedimenlary Geology), Special Publication,

pp.

13-28,

Siride,

A.H.,

I9K2, Oljshorc Tidat Sands: Processes attd Deposits.

Chapman

and

Hall.

Siridc.

A.H.,

Belderson,

R.H,,

Kenyon,

N.H., and

Johnson,

M.A..

1982.

Offshore lidal deposits: sand sheet

and

sand bank I'acies.

In

Stride.

A.H.

(ed.). Offshore Tidal .Sands:

Prix

esses

and

Deposits.

Chapman

and

Hall,

pp.

95-125.

Siller,

J.R., and

Beriyhill. H.L,J,. 1985. Late Quaternary shelf-maigui

deltas.

Northwest Gulf

of

Mexico, Bulletin of the American.Associa-

tion of PetrotiumGentogists.

69 (\y. 77 91,

Swifl. D.J.P.,

and

Eield,

M.E., 1981.

Evolution

of a

classic sand

ridge lield: Maryland sector. North American inner

shelf.

.Seili-

tncntology.

28:

461

4S2.

Sydow.

J., and

Roberts.

H.H.,

1994. Stratigraphit- framework

of a

late

Pleistocene shelf-edge delta, northeast Gulf

of

Mexico. Ameriean

.4ssoeiation

of

Petroteum Geotogisis

Buttetin.

78:

1276-L312,

Tillman,

R.W.,

1999.

The

Shannon Sandstone:

a

review

of the

Sand-

Ridge

and

Olher Models.

In

Bergman.

K.M.. and

Snedden,

J.D.

(eds.).

Isolated Shallow Marine Sand Bodies: Seqnenee Stratigraphie

.Analysis

and

Sedimentologie Interpretation. SEPM (Society

tor

Sedimenlary Geology),

pp, 29 53.

Treniesaux.

A..

Berne.

S., and

Stolk.

A.. 1999.

Sedimenlology

and

stratigraphy

of a

tidal sand bank

in the

southern North

Sea.

Marine Geology. 159:253

272.

Visser,

M.J..

19S(). Neap-spring cycles reflected

in

Holocene siiblidal

large-scale bedform deposits:

a

preliminary note. Geologv.

8: 543

546.

Wagle,

B.G., and

Veerayya.

M.,

1996. Submerged sand ridges

on ihe

western continental shelf

off

Bombay, India: evidenee

for

Late

Pleistocene-Holocene sea-level changes. Marine Geology. 136:

79-

95,

Winn, R.D., Roberts,

H.H.,

Kohl.

B.,

Eillo. R.H., Crux, J.A.. Bouma,

A.H.,

and

Spero,

H.W., 1998.

Upper Quaternary strata

ol" the

upper continenlal slope, northeast Gulf

of

Mexico: sequence

siratigraphic model

for a

terrigeneous shelf edge. Journal

of

Sedi-

mentary Researeh.

68

(4): 579-595.

Yang, CS,, 1989. Active, moribund

and

buried tidal sand ridges

in the

Easl China

Sea and the

Southern Yellow Sea. Marine

Geologv.

88:

97

116.

Cross-references

Coasial Sedimentary Eacies

Cross-Slratilication

(jiaucony

and

Verdine

Milankovitch C~ycles

Ripple. Ripple Mark, Ripple Structure

Sediment Transport

hy

Tides

Sedimeni Transport

by

Waves

Suiface Forms

Tides

and

Tidal Rhvthmites

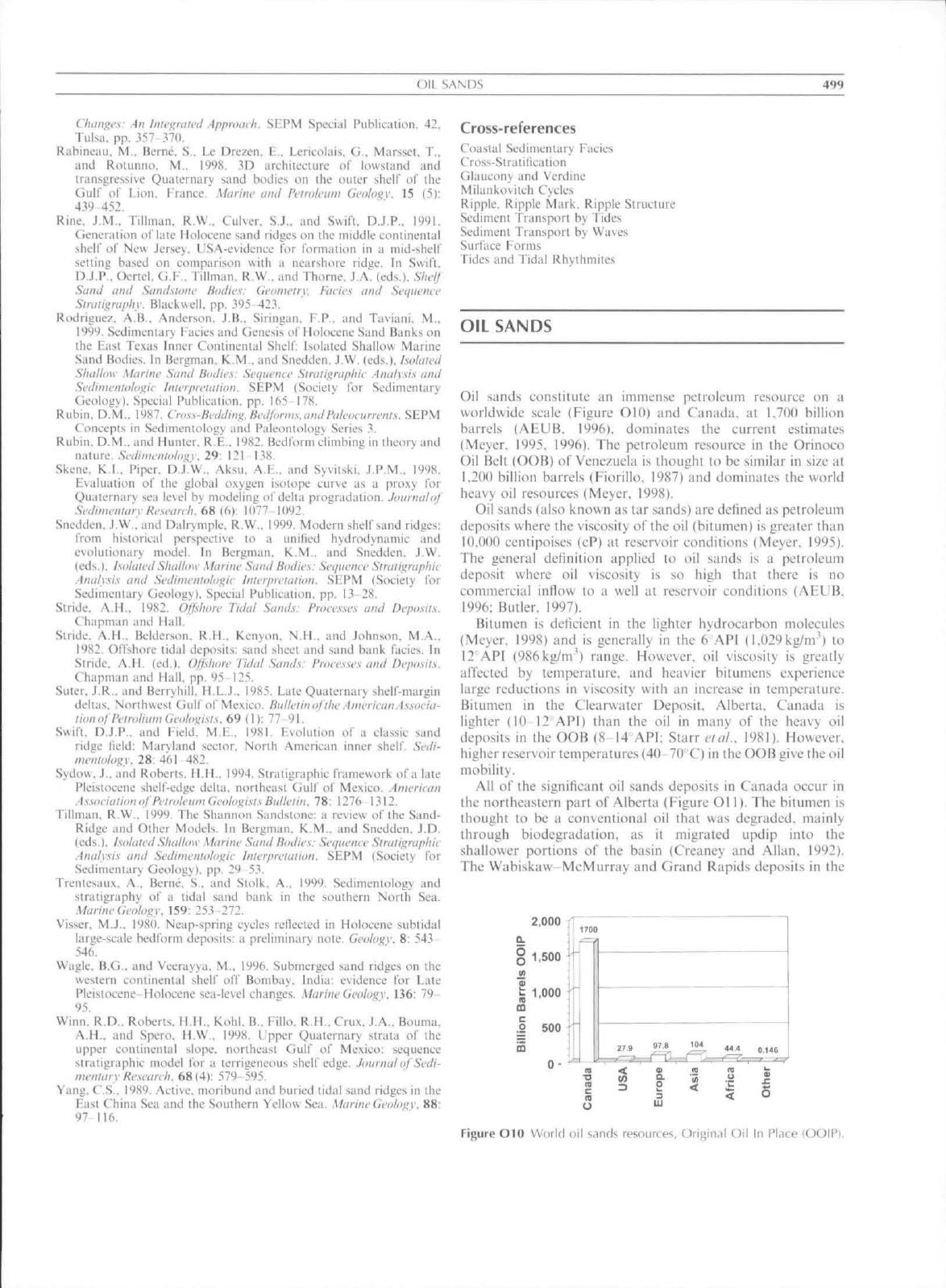

OIL SANDS

Oil sands constitute an immense petroleum resource on a

worldwide scale (Figure OlO) and Canada, at 1.700 billion

barrels (AFUB, 1946), dominates the current estimates

(Me\er. 1995, 1996), The petroleum resource in ihe Orinoco

011 Belt (OOB) of Venezuela is thought lo bo similar in size at

1,200 billion barrels (Fiorillo, 1987) and dominates the world

heavy oil resources (Meyer, 1998),

Oil sands (also known as tar sands) are delined as petroleum

deposits where the viscosity of the oil (bilumcn) is greater than

10,000 centipoises (cP) at reservoir conditions (Meyer, 1995).

The general definition applied to oil sands is a petroleum

deposit where oil viscosity is so high ihat there is no

commercial inflow to a well at reservoir conditions (AEUB,

1996;

Butler, 1997).

Bitumen is deficient in the lighter hydrocarbon molecules

(Meyer. 1998) and is generally in the 6 API (1,029kg/m') to

12 API (986kg/m ) range. However, oil viscosity is greatly

affected by temperature, and heavier bitumens e.\perience

large reductions in viscosity with an increase in temperature.

Bitumen in the CIcarwatcr Deposit. Alberta. Canada Is

lighter (10 12 API) than the oil in many o\' the heavy oil

deposits in the OOB (8-14 API: Starr etal., 1981). However.

higher reservoir temperatures (40 70"^C) in the OOB give the oil

mobility.

Al!

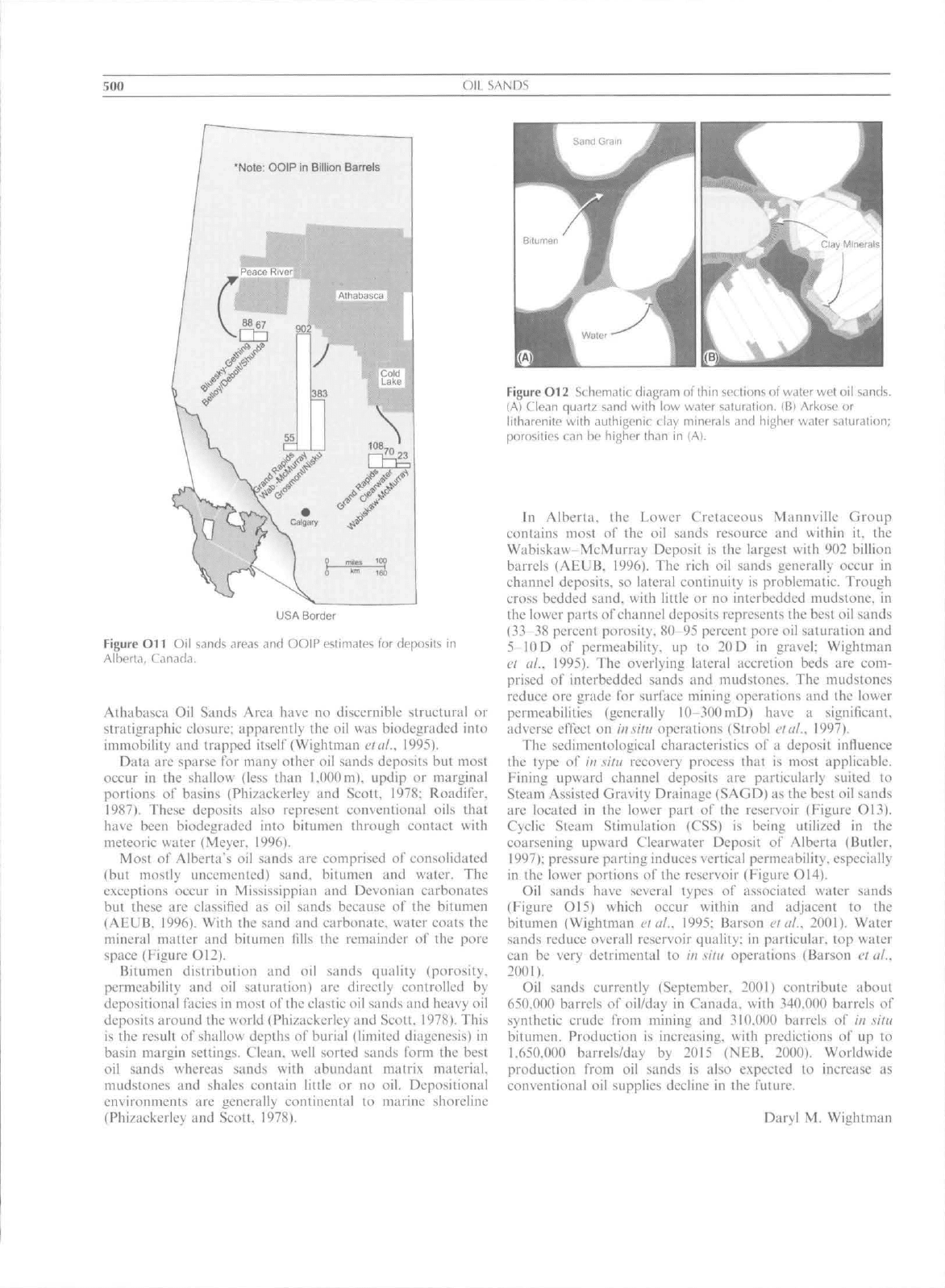

of the significant oil sands deposits in Canada oeeur in

the northeastern part of Alberta (F-igure Oil). The bitumen is

thought to be a eonvcntional oil that was degraded, mainly

through biodegradaiion, as it migrated iipdip into the

shallower portions of the basin (Creaney and Allan, 1992),

The Wabiskaw-McMurray and Grand Rapids deposits in the

Figure

O10

World

oil

sands resources, Origin.il

Oil In

Pl.ite (OOIP).

OIL SANDS

USA Border

Figure Oil Oil sands areds and OOIP estimates for deposits in

Aiberla, Canada,

Athabasca Oil Sands Aren have no discernible structural or

stratigraphic closure; apparently the oil was biodcjzradcd into

immobility and trapped itself (Wightman

ctttf.

1995).

Dala are sparse for many other oil sands deposits but most

occur in the shallow (less than I.OOOm), updip or marginal

portions of basins (Phizackerley and Scott, 1978: Roadifcr.

1987). These deposits also represent conventional oils that

have been biodegraded into bitumen through contact with

meteoric water (Meyer. 1996).

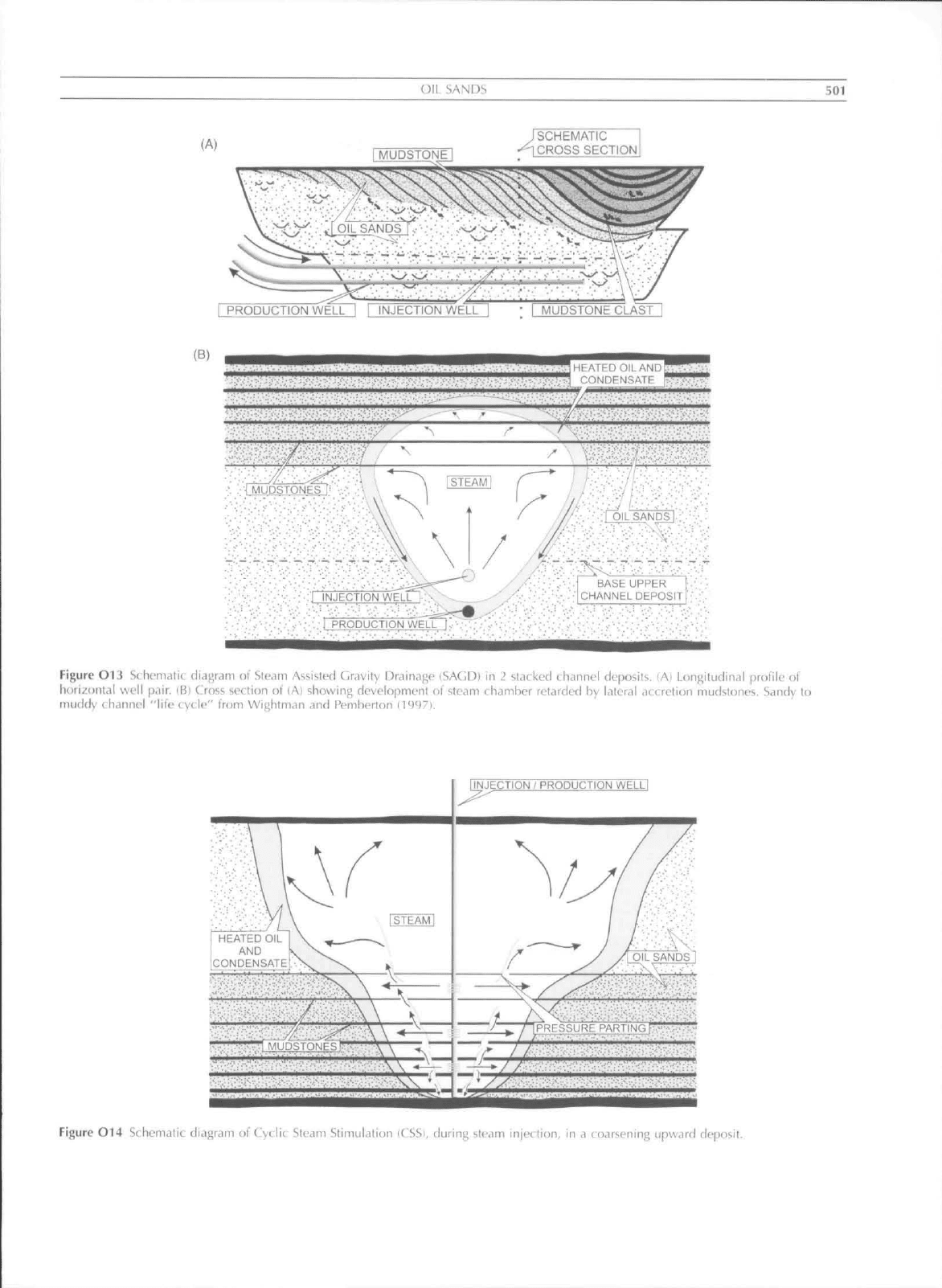

Most of Alberta's oil sands are comprised of consolidated

(but mostly uncementcd) sand, bitumen and water. The

exceptions occur in Mississippian and Devonian carbonates

but these are classified as oil sands because of the bitumen

(AEUB. 1996). With the sand and carbonate, water eoats the

mineral matter and bitumen tills the remainder of the pore

space (Figure OI2).

Bitumen distribution and oil sands quality (porosity,

permeability and oil saturation) are directly controlled by

depositional facies in most of the clastic oil sands and heavy oil

deposits around the world (Phizackerley and Scott. 1978). This

is the result of shallow depths of burial (limited diagenesis) in

basin margin settings. Clean, well sorted sands form the best

oil sands whereas sands with abundant matrix material,

mudstones and shales eontain little or no oil, Depositional

environments are generally continental to marine shoreline

(Pliizackerley and Scott. 1978),

Figure O12 Schematic diagram of

thin

sections of water wet oil sands,

(A) Clean quartz sand with low water saturation. (B) Arkose or

litharenite with authigenic clay minerals and higher water saturation:

porosities (aii be higher than in (A).

In Alberta, the Lower Cretaceous Mannvillc Group

contains most of the oil sands resource and within it. the

Wabiskaw-McMurray Deposit is the largest with 902 billion

barrels (AEUB. 1996), The rich oil sands generally occur in

channel deposits, so lateral continuity is problematic. Trough

cross bedded sand, with little or no interbedded mudstone. in

the lower parts of channel deposits represents the best oil sands

(33 38 pereent porosity. SO 95 percent pore oil saturation and

5 lOD of permeability, up to 20D in gravel; Wightnian

L't al., 1995). Ihe overlying lateral accretion beds are com-

prised of interbedded sands and mudstones. The mudstones

reduce ore grade for surface mining operations and the lower

permeabilities (generally 10-300 niD) have a significant,

adverse effect on i/i.^itti operations (Strobl eial.. 1997).

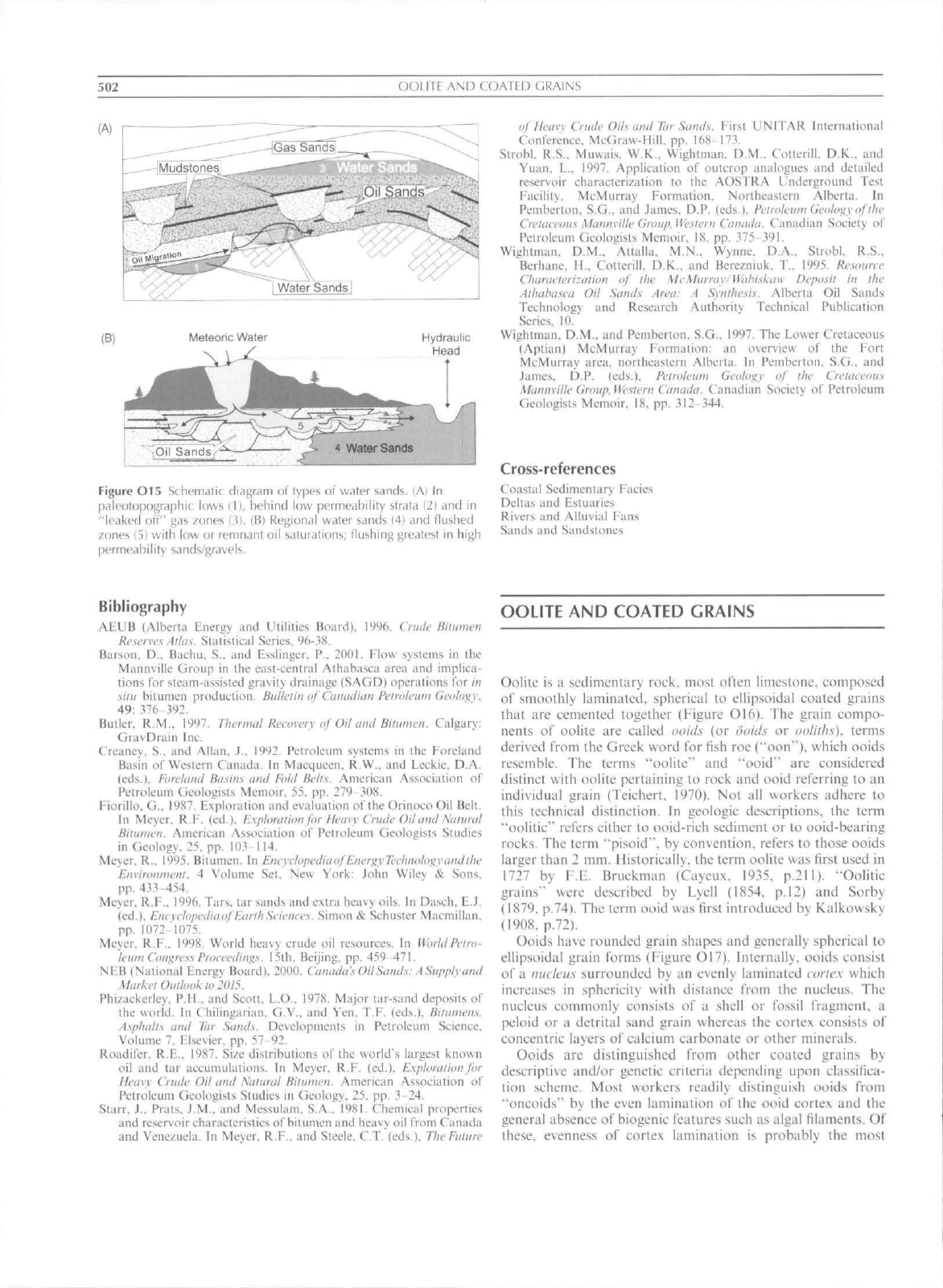

Tlie sedimentological characteristics of a deposit influence

the type of itt sitti recovery process that is most applicable.

Fining upward channel deposits are particularly suited to

Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD) as the best oil sands

are located in the lower part of the reservoir (F'igure 013),

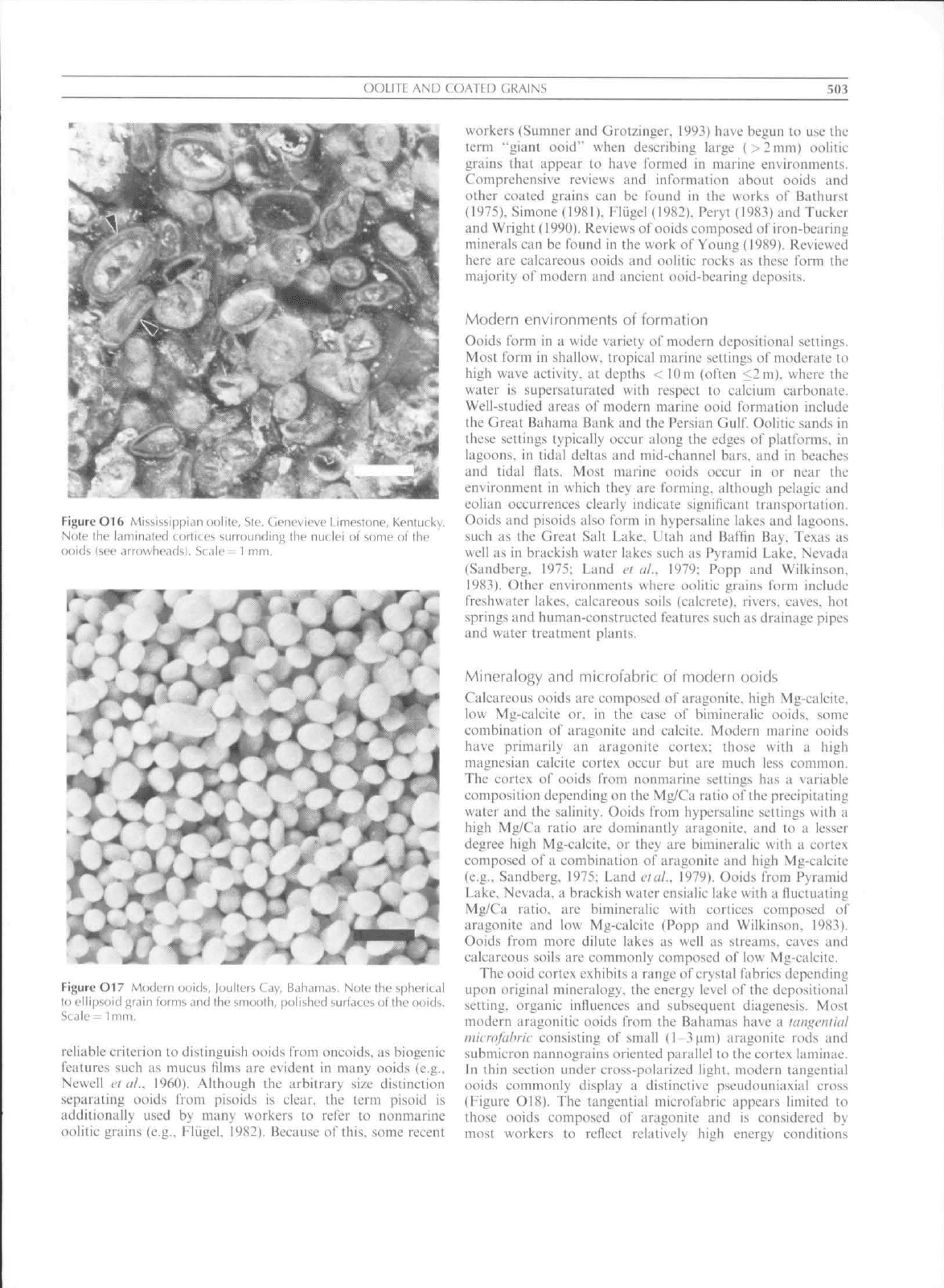

Cyclic Steam Stimulation (CSS) is being utilized in the

coarsening upward Clearwater Deposit of Alberta (Butler.

1997); pressure parting induces vertical permeability, especially

in the lower portions of the reservoir (Kigure 014).

Oil sands have several types of associated water sands

(Figure O15) which occur within and adjacent to the

bitumen (Wightman etal.. 1995; Barson etal.. 2001), Water

sands reduce overall reservoir quality; in particular, top water

can be very detrimental to iti sit ti operations (Barson etal.,

2001).

Oil sands currently (September. 2001) contribute about

650.000 barrels of oil/day in Canada, with 340.000 barrels of

synthetic crude from mining and 310.000 barrels of itt situ

bitumen.

Production is increasing, with predietions of up to

1.650.000 barrels/day by 2015 (NEB. 2000). Worldwide

production from oil sands is also expected to increase as

conventional oil supplies decline in the future.

Darvl M. Wichtman

OIL

(A)

I

MUDSTONT

I SCHEMATIC

-^1 CROSS SECTION

OLSANDS .•••:-:•:

<<^.^.

PRODUCTION WELL INJECTION WELL

(B)

HtAI tU OIL AND

CONDENSATE

Figure O13 Scht'matit diagram of Steam Assisted Graviiy IJraJnagc (SACiDi in 2 slacked i hannel deposits. lA} Longiludin.il profile of

horizontal well pair. |B| Cross secrlion ol (A) showing devolopmeni of steam chamber retarded by laterai accretion niudstones, Sandy to

muddy ch<innel "iile cycle" from Wightman and Pemberton (19')7I.

INJECTION / PRODUCTION WELL

I

Figure O14 Schematic di<)gr<ini ol Cydic Steam SliniuLilion (CSSi, during t^lcom injection, in a coarsening upv\ar(l cleposil.

502 OOl ITF AND COATED (iRAINS

(A)

Meteoric Water

Hydraulic

Head

Figure O15 Schematic diagram

of

types

of

water sands.

(Al In

paleotopographic lows

(I i.

behind

low

permeability strala

(2)

and

in

"leaked

off"

gas zones

(.51.

(B)

Regional water sands

(4)

and flushed

zones (5) with

low or

remnant oil saturations; flushing greatest

in

high

permeability sands/gravels.

of Heavy Crude Oils

and

Ttir

.Sands. First LINITAR Inlernalional

ronference, McGniu-Hill.

pp. 168 173.

Strohl,

R,S,.

Miivviiis.

W.K..

Wightman.

D.M..

Cotterill. D.K...

and

Yuan.

L., 1997.

Application

of

outcrop analogues

and

detailed

reservoir characterization

to the

AOSTRA I'lidergroitnd Test

Fticilily. McMurray Formation. Northeastern Alberta.

In

Pemberton.

S.G., and

James.

D,P,

(eds,). Petroleum

Geology

of the

CretacciHis

Mainnille

Group,

ll'e.stern

Canada. Canadian Society

of

Petroletim Geologists Memoir. 18.

pp. 375 }9\.

Wighlman.

D.M.,

^Attalla.

M,N,.

Wynne,

D.A..

Strobl.

R.S..

Berhane.

H.,

Cotterill.

D.K.. and

Berezniuk.

T.. 1995.

Re.wuree

Characterization

of the

McMio-ray- liuhi.sknw Deposit

in the

Athahiisea

Oil

Sands Area:

A

Synthesis. ,Mberta

Oil

Sands

Technoloiiy

and

Research Authority Teehnieal Publication

Series.

10?

Wiglitman. D.M,.

and

Pemberton.

S.G..

1997.

Tbe

Lower Cretaceous

(Aptian) McMiirniy Formation:

an

overview

of ihe

Kort

MeMurray area, nortlieastern Alberta-

In

Pemberton,

S.G..

iind

James.

D.P.

(eds.). Petroleum Geology

of the

Cretaceous

Mannville

Group.

IVestern

Canada. Canadian Society

of

Petroleum

Geologists Memoir. 18.

pp. 312 344.

Cross-references

Coiistal Sedimentary Facies

Deltas

imd

Estuaries

Rivers

and

Alluvial Fans

Sands

and

Sandstones

Bibliography

AHUB (Alberta Energy

and

Utilities Board).

1996,

Crude Bitumen

Re.serves

Atlas. St;itistieal Series. 96-38.

Barson.

D..

Bachu.

S,. and

Esslinger,

P.,

2001. Flow syslcms

in ihe

Mannville Group

in the

east-central Aihabast-a area

and

implica-

tions

for

steam-assisted graviiy drainage (SAGD) operations

for //;

situ bitumen production. Buttetin

of

Canadian Petroleum Geotogy,

49:

376-392.

Butler.

R.M.. 1997.

Ttiermid Reeovery

of

Oit

and

Bitiaiien. Calgary:

CjravDrain

Inc.

Creaney.

S.. and

Allan.

J., 1992.

Petroleum systems

in ihc

Foreland

Basin

of

Western Canada,

In

Macqueen.

R,W., and

Lcckie,

D.A.

(eds,).

Foretand Basins

and

Fotd Betts. American Association

of

Petroleum Geologists Memoir.

55. pp, 279 308.

Fiorillo,

G..

1987. Explor;ition

and

evaluation

of

the Orinoco Oil Belt,

In Meyer.

R.F.

(ed,). E.\ploration for Heavy Crude Oil

and

Natural

Sitianen. American Association

of

Peiroleum Geoloiiists Studies

in Geology.

25. pp. 103 114,

Meyer.

R,.

1995. Bitumen.

In

Eneyelopedia of Energy Tirhnology and

ihe

Environment.

4

Volume

Set, New

York: John Wiley

&

Sons,

pp.

433-454.

Meyer. R.F.. 1996. Tars.

lar

sands

and

extra heavy oils.

In

Diiseh.

E.J,

(ed.).

Encvctopediaof Earth Sciences. Simon

&

Schuster Maemillan.

pp.

1072-1075.

Meyer.

R,F,,

1998, World heavy crude

oil

resources.

In

World

Petro-

leum

Congress

Proceedings.

15th,

Beijing,

pp.

459-471,

NEB (National Energy Boiu'd). 2000. Canada's Oil Sands: A Supply

and

Market Ontlook to 2015.

Phizackerley. P.H.,

and

Scott,

L.O..

1978. Major tar-sand deposits

of

the world.

In

Chilingariaii.

G.V.. and Yen. T.F,

(eds.). Bitumens.

Asphalts

and Tar

.Sands. Developments

in

Petroleum Science.

Volume

7.

Elsevier.

pp. 57 92.

Roadifer.

R.E.,

1987. Size distributions

of the

world's largest known

oil

and tar

accumulations.

In

Meyer.

R.F.

(ed.). Exploration tor

Heavy Crude Oil

and

Natural Bitumen. American Association

of

Petroleum Geologists Studies

in

(ieoiogy,

25, pp. 3 24.

Starr.

J,,

Prats. J.M..

and

Messulam.

S.A..

1981. Chemical properties

and reservoir characteristics

of

bitumen

and

heavy

oil

from Canada

and Venezuela.

In

Mever, R.F.,

and

Steele.

CT.

(eds.). The Future

OOLITE AND COATED GRAINS

Oolite is a sedimentary rock, most often limestone, composed

of smoothly laminated, spherical to ellipsoidal coated grains

thai arc cemented together (Figure O16). The grain compo-

nents of oolite are called ooids (or ooids or ooliths), terms

derived from the Greek word for fish roe ("oon"), whieh ooids

resemble. The terms "oolite" and "ooid" are considered

distinct with oolite pertaining to rock and ooid referring to an

individual grain (Teichert. 1970). Not all workers adhere lo

this technical distinction. In geologic descriptions, the term

"oolitic"" refers either to ooid-rich sediment or to ooid-bearing

rocks, Tlie term "pisoid"". by convention, refers to ihose ooids

larger than 2 mm. Historically, the term oolite was first nsed in

1727 by F.E. Brticktnan (Cayeux. 1935. p.2ll). -Oolilic

grains"" were described by Lyell (1854, p.l2) and Sorby

(1879,

p.74), The term ooid was first introduced by Kalkowsky

(1908,

p.72).

Ooids have rounded grain shapes and generally spherical to

ellipsoidal grain forms (Figure O17), Internally, ooids consist

of a tutdeit.s surrounded by an evenly laminated cortex which

increases in sphericity with distance from the nucleus. The

nucleus commonly eonsists of a shell or fossil fragment, a

peloid or a detrital sand grain whereas the cortex consists of

concentric layers of caleium earbonate or other minerals,

Ooids are distinguished from other coated grains by

descriptive and/or genetic criteria depending upon classifica-

tion scheme. Most workers readily distinguish ooids from

"oneoids"" by the even lamination of the ooid cortex and the

general absence of biogenic features such as algal filaments. Of

these, evenness ol" cortex lamination is probably the most

OOLITE AND COATED GRAINS

Figure O16 Mis^^issippian oolite, Slo. Genevieve Limestone, Kenlucky.

Nolc the liiminaled cortices surroundinj; the nuclei ol some of the

ooids (scv tirrowheaHs). Sc:ale =

1

mm.

Figure O17 Modern ooids, loultcrs Cay, Bahamas. Note the spherical

lo ellipsoid j^rain forms and the smooth, polished surfaces of the ouids.

Scale =

I

mm.

reliable criterion lo distinguish ooids from oneoids. as biogenie

features such as mucus films are evident in many ooids (e.g..

Newell I't al., 1960). Although the arbitrary size distinction

separating ooids from pisoids is clear, the term pisoid is

additionally used by many workers to refer to nonmarine

oolitic grains (e.g.. F-1iigel. 19S2). Because of this, some recent

workers (Sumner and Grotzinger. 1993) have begun to use the

term "giant ooid" when deseribing large (>2mm) oolitic

grains that appear lo have formed in marine environments.

Comprehensive reviews and information about ooids and

other coated grains can be found in the works of Bathurst

(1975).

Simone (1981). Kliigcl (1982). Peryt (1983) and Tucker

and Wrighl (1990). Reviews of ooids composed of iron-bearing

minerals ean be found in the work of Young (1989). Reviewed

here are ealeareous ooids and oolitic roeks as these form the

majority of modern and aneient ooid-bearing deposits.

Modern environments of formation

Ooids fortn in a wide variety of modern depositional settings.

Most form in shallow, tropical marine settings of moderate to

high wave activity, at depths <

10

m {often <2m). where the

water is supersaturated with respect to calcium carbonate.

Well-studied areas of modern marine ooid formation ineSitde

the Great Bahama Bank and the Persian

Gulf.

Oolitic sands in

these settings typically occur along the edges of plalfortns. in

lagoons, in tidal deltas and mid-ehannel bars, and in beaches

and tidal Hats. Most marine ooids oeciir in or near Ihe

environment in which they are forming, although pelagic and

eolian occurrences clearly indieate significant transportation.

Ooids and pisoids also form in hypersaline lakes and lagoons,

such as the Great Salt Lake. Utah and Baffin Bay. Texas as

well as in brackish waier lakes such as Pyramid Lake, Nevada

(Sandberg. 1975; Land eial.. 1979: Popp and Wilkinson.

1983),

Other environments where oolitic grains form include

freshwater lakes, calcareous soils (calcrete). rivers, caves, hot

springs and human-constructed features such as drainage pipes

and water treatment plants.

Mineralogy and microfabric of modern ooids

Calcareous ooids are composed of aragonite, high Mg-ealcile.

low Mg-ealeile or. in the case of bimineralic ooids. sotne

cotnbination of aragonite and calcite. Modern marine ooids

have pritnarily an aragonite cortex: those with a high

magnesian calcite cortex occur but are tnuch less common.

The eortex of ooids from nonmarine settings has a variable

eotnposition depending on the Mg/Ca ratio of the precipitating

water and the salinity. Ooids from hypersaline settings with a

high Mg/Ca ratio are dotninantly aragonite. and to a lesser

degree high Mg-ealeite. or they are bitninL'ralie with a cortex

composed of a cotnbination of aragonite and high Mg-calcite

(e.g.. Sandberg, 1975; Land etal.. 1979). Ooids from Pyramid

Lake. Nevada, a brackish water ensialic lake with a fluctuating

Mg/Ca ratio, are bimineralie with cortices composed of

aragonite and low Mg-calcite (Popp and Wilkinson. 1983).

Ooids from more dilute lakes as well as streams, caves and

calcareous soils are comtnonly cotnposed of low Mg-calcite.

The ooid cortex exhibits a range of crystal fabrics depending

upon original mineralogy, the energy level of the depositional

setting, organie iniluences and subsequent diagenesis. Most

modern aragonitic ooids from the Bahamas have a tatigetitial

tuiirafabrie consisting of small (1 3i.mi) aragonite rods and

submieron nannograins oriented parallel to the eortex laminae.

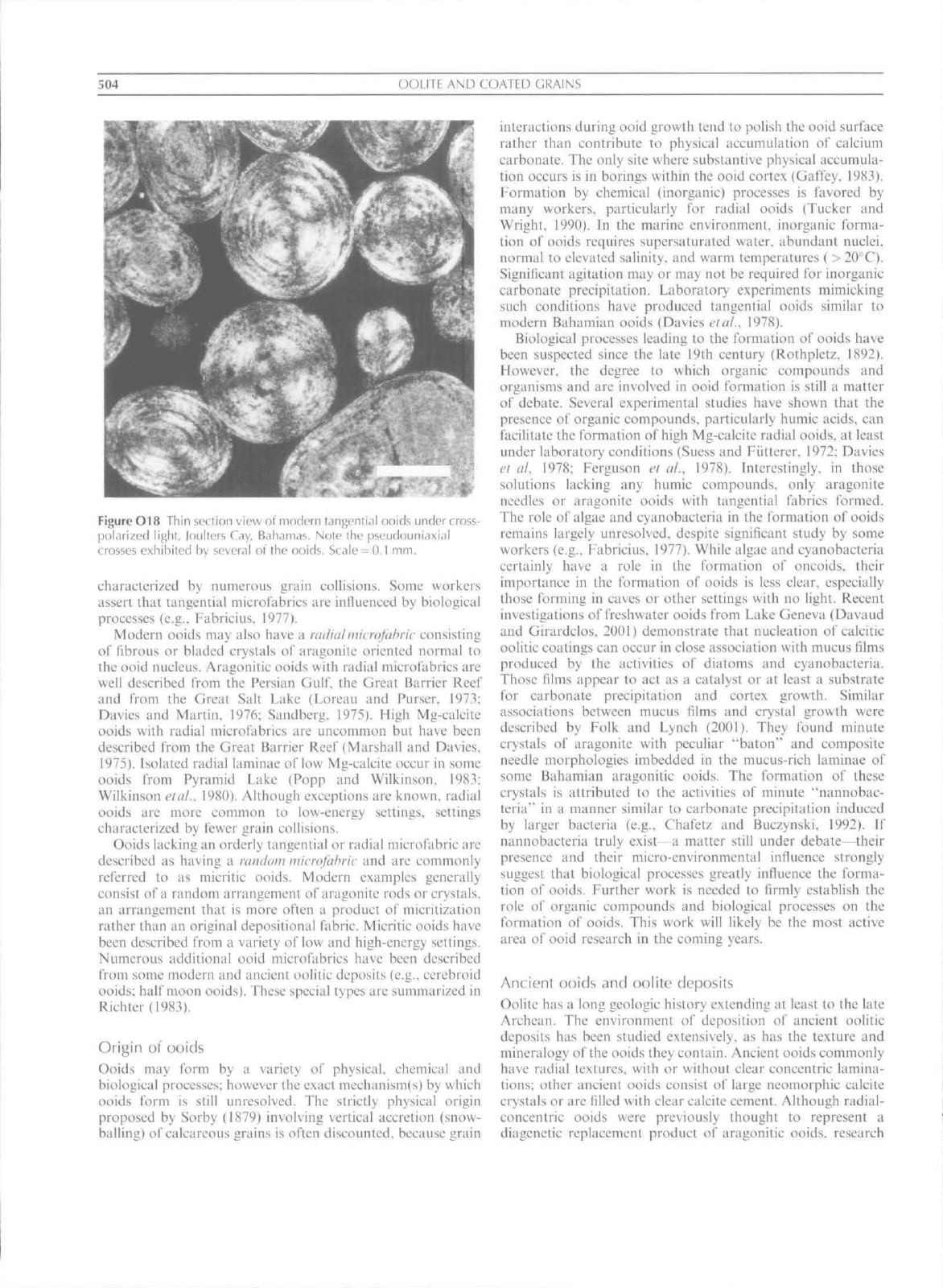

In thin section under cross-polarized light, modern tangential

ooids commonly display a distinctive pseudouniaxial cross

(Figure O18). The tangential microfabric appears limited lo

those ooids composed of aragonite and is considered by

most workers to rellect relatively high energy eonditions

504

OOLITE AND COATED GRAINS

Figure O18 Thin section view of modi'in laiij^enlial ooids under cross-

pol.irized light, Joulters Cay, Bahtimas. Note ihe [jseudouniaxial

crosses exhibited by several ot the ooids. Stale =

0,1

mm.

eharaeterized by numerous grain collisions. Sotne workers

assert that tangential microfabrics are influenced by biological

processes

(e.g.,

Pabricius, 1977).

Modern ooids may also have a

radiul tnicrofabric

consisting

of fibrous or bladed erystals of aragonite oriented normal to

the ooid nucleus. Aragonitic ooids with radial microfabrics are

well described from the Persian Gulf, the CJreat Barrier Reef

and frotn the Great Salt Lake (Loreau and Purser, 1973;

Davies and Martin. 1976; Satidberg, 1975). High Mg-calcite

ooids with radial microfabrics are nncotnmon but have been

described frotn the Great Barrier Reef (Marshall and Davies.

1975). Isolated radial laminae of low Mg-calcite occtir in some

ooids from Pyramid Lake (Popp and Wilkinson. 1983:

Wilkinson

etal..

1980). Although exceptions are known, radial

ooids are more eomtnon to low-energy settings, settings

characterized by fewer grain collisions.

Ooids lacking an orderly tangential or radial microfabric are

described as having a rattihnit

tiucrofahric

and are commonly

referred to as micritic ooids. Modern exatnplcs generally

consist of

a

random arrangetnent of aragonite rods or crystals.

an arrangement that is tnore often a product of micritization

rather than an original depositional fabric. Mieritie ooids have

been deseribed from a variety of low and high-energy settings.

Numerous additional ooid microfabrics have been deseribed

from some tnodern and ancient oolitic deposits

(e.g..

eerebroid

ooids:

half moon ooids). These speeial types are siimtnarized in

Richter (1983).

Origin of ooids

Ooids may fortn by a variety of physical, chemical and

biological processes; however the exael niechanistn(s) by which

ooids form is still unresolved. The strictly physical origin

proposed by Sorby (1879) involving vertical accretion (snow-

balling) of ealeareous grains is often discounted, beeause grain

interactions during ooid growth tend to polish the ooid surfaee

rather than contribute to physical accutnulation of calcium

carbonate. The only site where substantive physical aeeumula-

tion occurs is in borings within the ooid cortex (Gaffcy, 1983).

Formation by chemical (inorganic) processes is favored by

many workers, particularly for radial ooids (Tucker and

Wright, 1990). In the marine environment, inorganic forma-

tion of ooids requires supersaturated water, abundant nuelei.

normal to elevated salinity, and warm temperatures ( >

20^

C).

Signilicant agitation may or may not be required for inorganic

carbonate precipitation. Laboratory experiments mimicking

sueh conditions have produced tangential ooids simitar to

modern Bahamian ooids (Davies

etal..

1978).

Biological processes leading to the formation of ooids have

been suspected since the lale 19th century (Rothpletz, 1892).

However, the degree to which organic compounds and

organisms and are involved in ooid fortnation is still a matter

of debate. Several experimental studies have shown that the

presenee of organic eotnpoimds, partieularly humic acids, can

facilitate the formation of high Mg-calcite radial ooids, at least

under laboratory conditions (Sucss and Fiillerer. 1972: Davies

el ul. 1978: Ferguson ei al., 1978). Interestingly, in those

solutions laeking any humic compounds, only aragonite

needles or aragoniie ooids with tangential fabries formed.

The role of algae and eyanobacteria in ihe formation of ooids

remains largely unresolved, despite stgntfieant study by some

workers

(e.g.,

Fabricius, 1977). While algae and eyanobacteria

certainly have a role in the formation of oneoids. their

importance in the formation of ooids is less clear, especially

those fortning in caves or other settings with no light. Recent

investigations of freshwater ooids frotn Lake Geneva (Davaud

and Girardclos. 2001) demonstrate that nucleation of calcitic

oolitic coatings can occur in close association with mucus filtns

produced by the activities of diatoms and eyanobacteria.

Those films appear to act as a catalyst or at least a substrate

for earbotiate precipitation and cortex growth. Sitnilar

associations between tnucus films and erystal growth were

described by Folk and Lynch (2001). They found tninutc

crystals of aragonite with peculiar "baton" and composite

needle tnorphologies imbedded in the mucus-rich laminae of

sotne Bahatnian aragonitic ooids. The fortnation of these

crystals is attributed to the activities of minute "nannobac-

teria"

in a manner sitnilar to carbonate precipitation indticed

by larger bacteria

(e.g..

Chafetz and Buczynski. 1992). If

nannobacteria truly exist—a matter still under debate—their

presence and their micro-environtnental influence strongly

suggest that biological processes greatly inflttence the fortna-

tion of ooids. Further work is needed to firmly establish the

role of organie cotnpounds and biological processes on the

fortnation of ooids. This work will likely be the most active

area of ooid researeh in the coming years.

Ancient ooids and oolite deposits

Oolite has a long geologic history extending at least to the late

Archean.

The environtnent of deposition of ancient oolitic

deposits has been studied extensively, as has the texture and

mineralogy of

the

ooids they contain. Ancient ooids commonly

have radial textures, with or without elear eoncentric lamina-

tions;

other ancient ooids consist of large neomorphic calcite

crystals or are filled with clear calcite cement. Although radial-

concentric ooids were previously thought to represent a

diagenetic replacement product of aragonitie ooids, researeh