Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

NFRITir CARBONATE DFPOSITIONAL ENVIRONMENTS

465

-lOs-IOOs km

Constant wave

agitation of

saa floor

Lagoon

Mean Sea Lsvel

Basin

Iniwr ramp

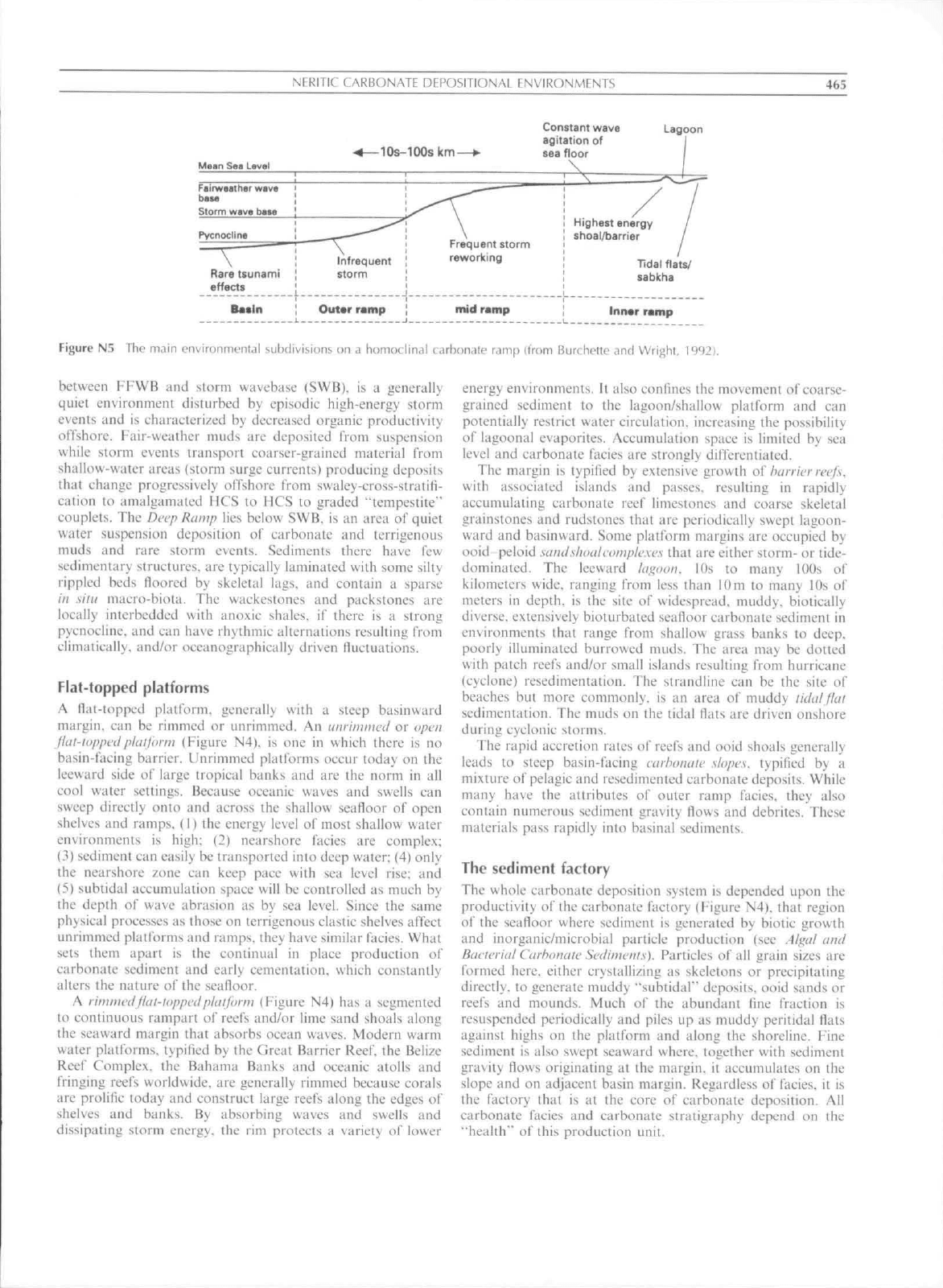

Figure N5 The main environmenttil subdivisions on a homociinal cirbon.ile ramp itrom Burthelte and Wright, 1992),

between FFWB and storm wavebase (SWB), is a generally

quiet environment disturbed by episodic high-energy storm

events and is charaeterized by decreased organie prodtictivity

otTshore, Fair-weather muds are deposited from suspension

while storm events transport coarser-grained material tYom

shallow-water areas (storm surge eurrents) producing deposits

that change progressively offshore frotn swaley-cross-stratifi-

cation to amalgamated HCS to HCS to graded "lempestite"

couplets. The Deep Ramp lies below SWB. is an area of quiet

water suspension deposition of carbonate and terrigenous

muds and rare storm events. Sediments there have few

sedimentary structures, are typically laminated with some silty

rippled beds floored by skeletal lags, and eontain a sparse

iit .situ maero-biota. The wackestones and packstones are

locally interbedded with atioxic shales, if there is a strong

pyenocline. atid can have rhythrnic alternations resulting from

climiitically. and/or oceanographically driven lUictuations.

Flat-topped platforms

A flat-topped platform, generally with a steep basinward

margin, can be rimmed or unrimmed. An titiiimntccl or open

flat-toppedplatfaritt (Figure N4). is one in which there is no

basin-facing barrier, Dnrimmed platforms occur today on the

leeward side of large tropical banks and are the norm in all

cool water settings. Because oceanic waves and swells can

sweep directly onto and across the shallow seafloor of open

shelves and ramps. (I) the energy level of most shallow water

environments is high; (2) nearshore facies are complex;

(3) sediment can easily be transported into deep water; (4) only

the nearshore zone can keep pace with sea level rise; and

(5) subudal accumulation space will be controlled as mueh by

the depth of wave abrasion as by sea level. Since the same

physieal processes as those on terrigenous clastic shelves affect

unrimmed platforms and ramps, they have similar facies. What

sets ihem apart is the continual in place production of

carbonate sediment and early cementation, which constantly

alters the nature of the seafloor.

A rimnu'dflat-toppedplaiform (Figure N4) has a segmented

to continuous rampart ol reefs and/or lime sand shoals along

the seaward margin that absorbs ocean waves. Modern warm

v\ater platlbrtns. typified by the Great Barrier

Reef,

the Belize

Reef Complex, the Bahama Banks and oeeanic atolls and

fringing reefs worldwide, are generally rimmed beeause eorals

are prolific today and construct large reefs along the edges of

shelves and banks. By absorbing waves and swells and

dissipating storm energy, the rim protects a variety of lower

energy environments. It also confines the movement of coarse-

grained sediment to the lagoon/shallow platform and can

potentially restrict water circulation, increasing the possibility

of lagoonal evaporites. Accutnulation space is litiiited by sea

level and carbonate facies are strongly differentiated.

The margin is typified by extensive growth of hairier reefs.

with associated islands and passes, resulting in rapidly

accumulating carbonate reef limestones and coarse skeletal

grainstones and rudstones that are periodically swept lagoon-

ward and basinward. Some platform margins are occupied by

ooid peloid satidshoaleomplexes that are either storm- or tide-

dominated. The leeward lagoon. lOs to many

I OOs

of

kilometers wide, ranging from less than

10

m to many 10s of

tTieters in depth, is the site of widespread, muddy, biotically

diverse, extensively bioturbaied seafloor carbonate sediment in

environments thai range from shallow grass banks to deep.

poorly illutninated burrowed tnuds. The area may be dotted

with patch reefs and/or small islands resulting from hurricane

(cyclone) resedimentation. The strandiine can be the site of

beaches but more commonly, is an area of muddy tidal flat

sedimentation. The muds on the tidal flats arc driven onshore

during cyclonic storms.

The rapid accretion rates of reefs and ooid shoals generally

leads to steep basin-facing carhotiate slopes, typified by a

mixture of pelagic and resedimented carbonate deposits. While

many have the attributes of outer ramp facies, they also

contain numerous sediment gravity flows and debrites. These

materials pass rapidly into basinal sediments.

The sediment factory

The whole earbonate deposition system is depended upon the

productivity of the carbonate factory (Figure N4). that region

of the seafloor where seditnent is generated by biotie growth

and inorganie/mierobial particle production (see Algal and

Bacterial Carbonate Sediments). Particles of all grain sizes are

formed here, either crystallizing as skeletons or precipitating

directly, to generate muddy "subtidal"' deposits, ooid sands or

reefs and mounds. Mueh of the abundant tine fraetion is

resuspended periodically and piles up as muddy peritidal flats

againsi highs on the platform and along the shoreline. Fine

sediment is also swept seaward where, together with sediment

gra\ity flows originating at the margin, it accumulates on the

slope and on adjacent basin margin. Regardless of facies, it is

the factory that is at the eore of carbonate deposition. All

earbonate facies and carbonate stratigraphy depend on the

"health" of this production unit.

466

NERITIC CARBONATE DEPOSITIONAL ENVIRONMENTS

For carbonate production and sediment aceumulation to be

at a maximum, the environment must be just right: not too

deep,

not too shallow; not too warm, nor too cold; not too

fresh, but not too saline either; not too much terrigenous

clastic sediment; not too many nutrients but neither too few

(the Goldilocks Witidow of Goldliammer et al.. 1990). The

warm-water, tropical factory is dominated by the phoiozoan

a.ssetnhktge (James and Clarke. 1997) which comprises calcar-

eous phototrophic/mixotrophic organisms with photosym-

bionts, calcareous algae, ooids and mud-producing algae and

microbes. These thrive in the euphotic zone (generally <

120 m

deep in the modern ocean) and produce most sediment in

waters less than 20 m deep (Schlager. l^Rl). This factory is

highly sensitive to oceanic perturbation and is best developed

in elear oligolrophic, open ocean settings, with elevated

nutrients, terrigenous elays. saline and fresh water al! being

deleterious to optimum accumulation. The slower-growing

Iwlerozoan

us.setnblage

is there in the background of tropical

environments but dominates cool-water settings. It can e,\tend

to depths of --300 m. beyond which it beeotnes insignificant,

but maximum production is generally <150m.

Accumulation rates

The Holocene warm-water carbonate factory (excluding reefs)

produces sediment that accumulates at rates of - lOcm/1.000

years to 60cm/l,000 years. Cenozoic cool-water platform

sediment accumulates at -I cm/1,000 years to lOcm/l.OOO

years.

It is difficult to assess rates of sediment aeeumulation in

aneient platforms beeause of post-depositional diagenesis. that

is.

physical and chemical compaction, but most are in the

range of

2

em/1.000 years to

10

em/1,000 years (Schlager, 1981;

James and Bone. 1991),

Subtidal environments

Shallow inner to mid ramp and lagoonal seafloor settings are

euphemistically called "subtidal environments", as separate

from reefs, sand shoals, strandiine and slope settings, and

constitute the bulk of the earbonate factory. They comprise

thai part of the seafloor that is relatively uniform in

composition and biota. Conditions are normal open marine,

the biota is diverse and sediment is typically [nuddy.

Sediment forms through biogenic or biogcnically mediated

processes and if not buried quickly is altered by early, seafloor

diagenesis (see Diagenesis). Little material is generated by

physical abrasion. Mud is produced by water-eolumn pre-

cipitation, by disintegration of calcareous algae and delicate

invertebrate skeletons or by bioerosion. Sands are biofrag-

mental. oolitic, peloidal and intraclastie. Granule and boulder-

size material is formed by invertebrate skeletons and sediment

lithified in the environment of deposition and eroded by

physical proeesses. Beeause so mueh sediment is biogenie.

grain-size is as much a function of organism skeletal

architecture as it is hydrodynamic energy. The nature of the

sediment is principally controlled by water temperature

although elevated salinity dramatically reduces benihic and

thus particle diversity.

Seditnents. once produced, are typically burrowed and/or

ingested by a host of infaunal organisms. Dwelling burrows

are particularly conspicuous, creating both a labyrinth of

tunnels and reworking vast amounts of sediment. Ingestion

of seditnent in turn passes sediment through the guts of

invertebrates many times before final deposition, and these

organisms produee fecal pellets, which, if lithified early, are

preserved.

Storms are particularly effective in earbonate environments

because they are so shallow. Wanii-water. tropical environ-

ments are espeeially susceptible to hurricanes and eyclones.

Cool-water environtnents are affected by winter storms where.

in open ocean situations, wave-base may reach 200 m or more.

On rimmed platforms storms erode and transport sediment on

the

shelf,

sweep sediment into islands and transport fines onto

tidal flats or across the shelf edge as mud plumes. On open

shelves and ramps there is transport from shallow to deeper

water. Thus, storm beds are a common feature of "subtidal"

environtnents. usually typified by shell lags in Phanerozoic

carbonates and storm lags of rounded intradasts in Preeam-

brian and early Phanerozoic roeks.

Modern, shallow, euphotic environments in all realms are

characterized by prolific growth of plants, especially sea-

grasses. Plant leaves act as renewable substrates for delicate

calcareous encrusters that eventually produce mud-size parti-

cles.

The roots bind sediment together and thus impede

erosion. The leaves also act as a baffle slowing water

movement and as a protective canopy for the growth of a

variety of other algae and invertebrates. Modern grasses are

angiosperms and so this environtneui is Cretaceous and

younger. While microbes doubtless played a similar role in

the older rock record, the nature of this niche is uncertain. In

cold-water, high-energy, neritic environments soft green and

brown algae (kelp) are prolific, and act in the same way as

renewable substrates for carbonate epibionts.

In general, sediment in warm-water, inner ramp or lagoonal

environments is typieally biotically diverse floatstone, wack-

estone and packstone tliat is burrowed and punctuated by

storm deposits in the form of biofragmental tempestites and/or

shell-intraclast lags. On cool-water shelves and ramps, muddy

sediments are rare and the sediment is typically high-energy

biofragmental rudstone and grainstone. Mud only accumu-

lates below storm wave base.

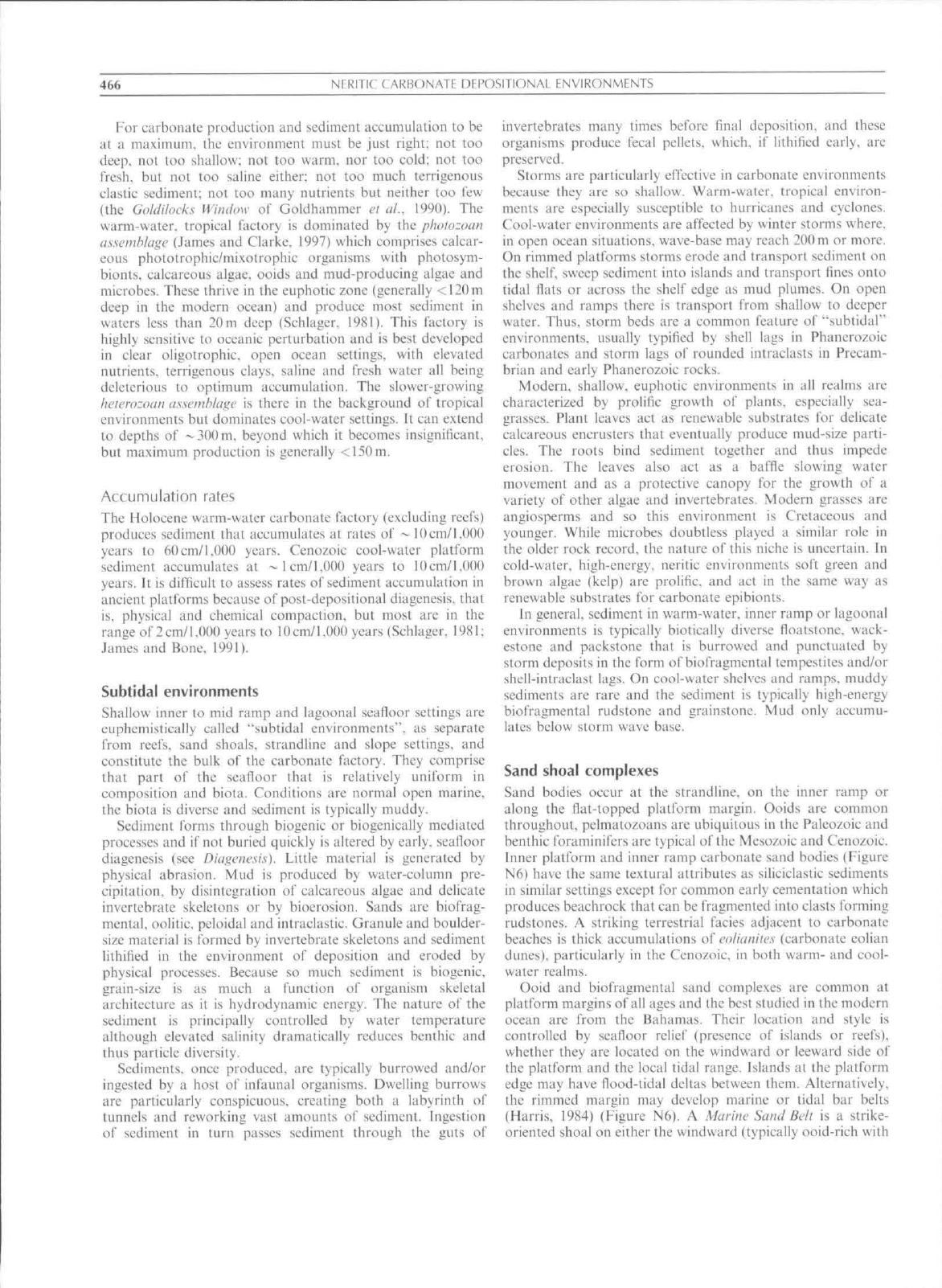

Sand shoal complexes

Sand bodies occur at the strandiine. on the inner ratnp or

along the flat-topped platform margin. Ooids are eommon

throughout, pelmatozoans are ubiquitous in the Paleozoic and

benthie foraminifers are typical of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic.

Inner platform and inner ramp carbonate sand bodies (Figure

N6) have the same textural attributes as siliciciastic sediments

in similar settings except for common early cementation which

produces beachrock that can be fragmented into elasts forming

rudstones. A striking terrestrial facies adjacent to carbonate

beaches is thick accumulations of

eoUanltes

(earbonate eolian

dunes),

particularly in the Cenozoie, in both warm- and cool-

water realms,

Ooid and biofragtnental sand eomplexes are comtnon at

platform margins of all ages and the best studied in the modern

ocean are from the Bahamas. Their location and style is

controlled by seafloor relief (presence of islands or reefs),

whether they are located on the windward or leeward side of

the platform and the local tidal range. Islands at the platform

edge may have flood-tidal deltas between them. Alternatively,

the rimmed margin may develop marine or tidal bar belts

(Harris. 1984) (Figure N6). A Marine Sand Bell is a strike-

oriented shoal on either the windward (typieally ooid-rich with

NERITIC CARBONATE DEPOSITIONAL ENVIRONMENTS 467

RAMP

PLATFORM

Strait

Island

RMl

Shoals

Ftull

RIMMED PLATFORM

Dip-Onwit«d

Figure

N6

Ttu^ style

and lot

.ilion

of

Ctirbonjle sand shoals.

on-shelf directed transport)

or the

leeward (typically ooid-

peloid-biofragmenta!

and

offshelf directed transport) margin.

Such shoals

are a few km

wide

and up to

lOOkm

in

length

and

comprise

a

"shield"

of

subaqueous dunes covered

in

asymme-

trical, m-scale. flood-directed smaller dunes

and

broken

periodically

by

spillover lobes. Sands grade outboard into

more biofragmental deposits

and

inboard

ink)

muddy subtidal

facies.

The

shoals

are

capped locally

by

islands

and

eolianites.

In contrast,

a

Tidal

Bar

Belt comprises dip-oriented bars

of

elongate subaqtieous dunes normal

to the

platform margin.

They develop where strong tidal flow exceeds

1

m/seeond. with

flood

or ebb

flow dominating different sides

of the bar.

Work

on

high-energy cool-water platforms indicates that

much

of the

shelf

is

covered with widespread subaqueous

dunes composed

of

biofragments.

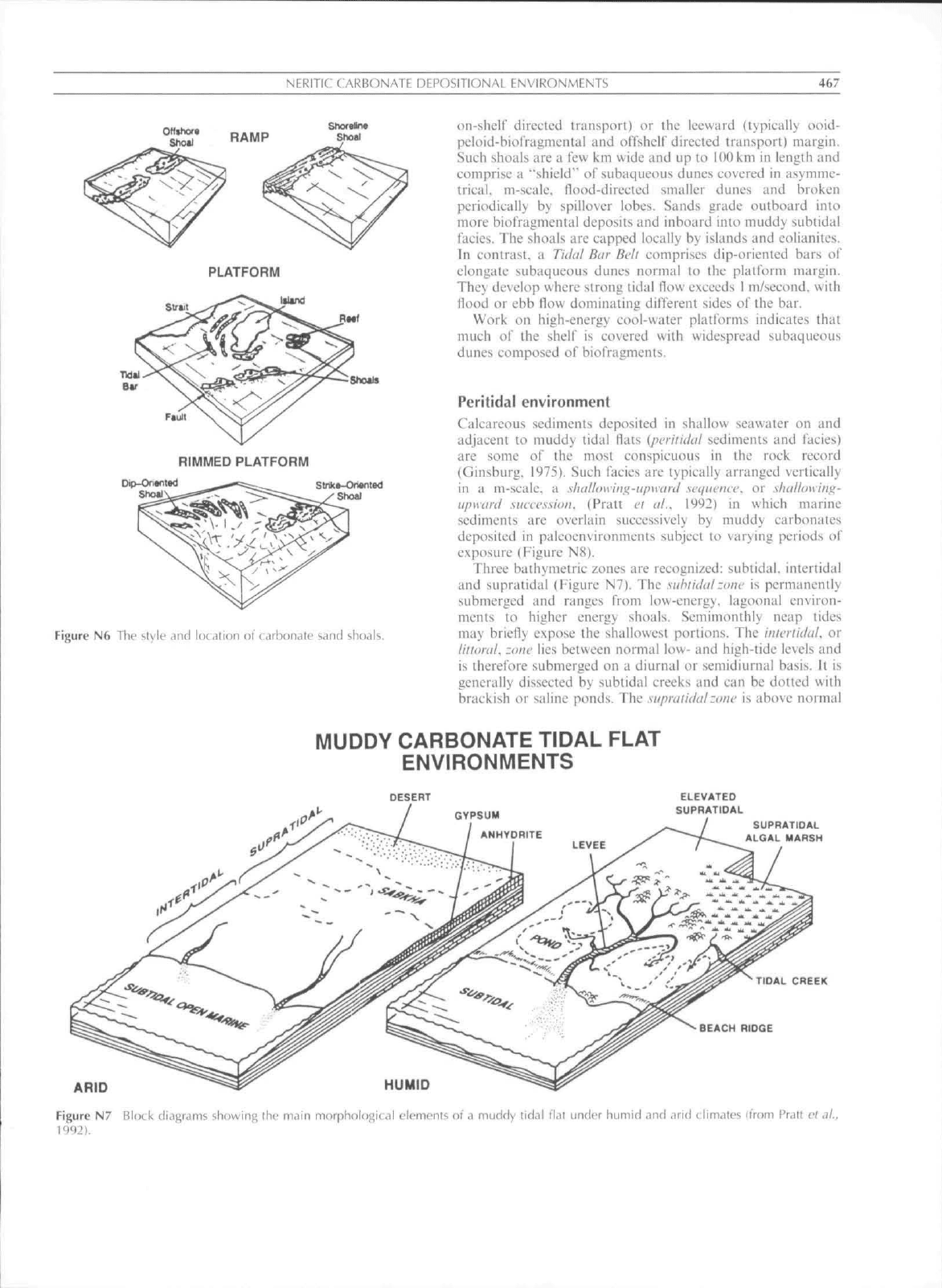

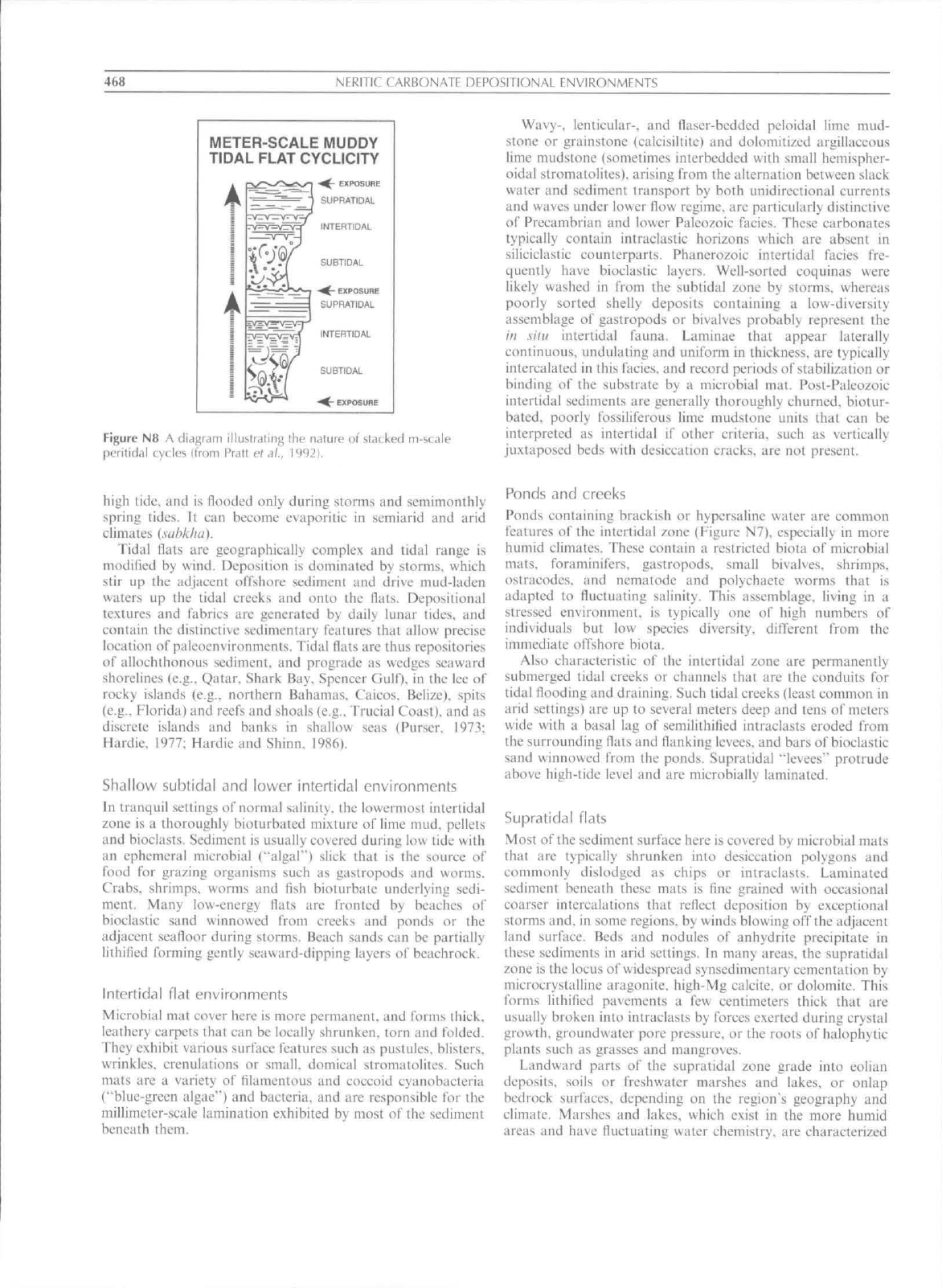

Peritidal environment

Calcareous sediments deposited

in

shallow seawater

on and

adjaeent

to

muddy tidal flats iperitidal sediments

and

facies)

are some

of the

most conspicuous

in the

rock record

(Ginsburg. 1975). Such facies

are

typically arranged vertically

in

a

m-scale.

a

shallowing-upward .sequence,

or

shallowing-

upward succession. (Pratt

ef al.. 1992) in

which marine

sediments

are

overlain successively

by

muddy carbonates

deposited

in

paieoenvironments subject

to

varying periods

of

exposure (Figure

N8).

Three bathytnetric zones

are

recognized: subtidal. intertidal

and supratidal (Figure

N7), The

subtidal zone

is

permanently

submerged

and

ranges from low-energy, lagoonal environ-

ments

to

higher energy shoals. Semimonthly neap tides

may briefly expose

the

shallowest portions.

The

inieriidal.

or

littoral, zotw lies between normal

low- and

high-tide levels

and

is therefore submerged

on a

diurnal

or

semidiurnal basis.

It is

generally dissected

by

subtidal creeks

and can be

dotted with

brackish

or

saline ponds.

The

supratidal zone

is

above normal

MUDDY CARBONATE TIDAL FLAT

ENVIRONMENTS

DESERT ELEVATED

SUPRATIDAL

SUPRATIDAI.

ALGAL MARSH

TIDAL CREEK

BEACH RIDGE

ARID

Figure

N7

HIntk diagrams showing

the

main morphologic.il element:^

ot d

muddy tidal flat under humiri anri <iri(l climates ifrom PratI

ct al.

1992}.

468

NERITIC CARBONATF DFPOSITIONAE ENVIRONMENTS

METER-SCALE MUDDY

TIDAL FLAT CYCLICITY

EXPOSURE

SUPRATIDAL

Figure N8 A diagram illustrating the nature ol stdtked m-scale

peritidal cycles (from Prat! el di. 1992).

Wavy-, lenticular-, and flaser-bedded peloidal lime mud-

stone or grainstone (calcisiltite) and dolomitized argillaceous

lime mudstone (sometimes interbedded with small hemispher-

oidal stromatolites), arising from the alternation between slack

water and sediment transport by both unidirectional currents

and waves under lower flou regime, are particularly distinctive

of Precambrian and lower Paleozoic facies. These carbonates

typically contain intraelastic horizons which are absent in

silicielastie counterparts, Phanerozoic intertidal facies fre-

quently have bioelastic layers. Well-sorted coquinas were

likely washed in from the subtidal zone by storms, whereas

poorly sorted shelly deposits containing a low-diversity

assemblage of gastropods or bivalves probably represent the

in siiu intertidal fauna. Laminae that appear laterally

continuous, undulating and uniform in thickness, are typically

intercalated in this facies. and record periods of stabilization or

binding of the substrate by a microbial mat. Post-Paleozoie

intertidal sediments are generally thoroughly churned, biotur-

bated, poorly fossiliferous lime mudstone units that can be

interpreted as intertidal if other eriteria, such as vertically

juxtaposed beds with desiccation cracks, are not present.

high tide, and is flooded only during storms and semimonthly

spring tides. It can beeome evaporitic in semiarid and arid

climates {sabkha).

Tidal flats are geographically eomplex and tidal range is

modifled by wind, Deposilion is dominated by storms, which

stir up the adjacent offshore sediment and drive mud-laden

waters up the tidal creeks and onto the flats. Depositional

textures and fabrics are generated by daily lunar tides, and

contain the distinctive sedimentary features that allow precise

location of paieoenvironments. Tidal flats are thus repositories

of allochthonous sediment, and prograde as wedges seaward

shorelines (e.g.. Qatar. Shark Bay, Spencer Gulf), in the lee of

rocky islands (e.g.. northern Bahamas, Caicos. Belize), spits

(e.g., Florida) and reefs and shoals (e,g.. Trucial Coast), and as

discrete islands and banks in shallow seas (Purser. 1973;

Hardie. 1977; Hardie and Shinn. 1986),

Shallow subtidal and lower intertidal environments

In tranquil settings of normal salinity, the lowermost intertidal

zone is a thoroughly bioturbated mixture of lime mud. pellets

and bioclasts. Sediment is usually covered during low tide with

an ephemeral microbial ("algal'") slick that is the source of

food for grazing organisms sueh as gastropods and worms.

Crabs,

shrimps, worms and fish bioturbate underlying sedi-

ment. Many low-energy flats are fronted by beaches of

bioelastic sand winnowed from creek,s and ponds or the

adjacent seafloor during storms. Beach sands ean be partially

lithified Ibrming gently seaward-dipping layers of beachrock.

Intertidal flat environments

Microbial mat cover here is more permanent, and forms thick.

lealhery carpets that ean be locally shrunken, torn and folded.

They exhibit various surface features such as pustules, blisters,

wrinkles, crenulations or small, domical stromatolites. Such

mats are a variety of filamentous and coceoid eyanobacteria

("blue-green algae") and bacteria, and are responsible for the

millimeter-scale lamination exhibited by most of the sediment

beneath them.

Ponds and creeks

Ponds containing brackish or hypersaline water are common

features of the intertidal zone (Figure N7), especially in more

humid climates. These contain a restricted biota of microbial

mats,

foraminifers, gastropods, small bivalves, shrimps,

ostracodes. and nematode and polyehaete worms that is

adapted to fluctuating salinity. This assemblage, living in a

stressed environment, is typieally one of high numbers of

individuals but low species diversity, different from the

immediate offshore biota.

Also characteristic of the intertidal zone are permanently

submerged tidal creeks or channels that are the conduits for

tidal flooding and draining. Such tidal creeks (least common in

arid settings) are up to several meters deep and tens of meters

wide with a basal lag of semilithiHed intradasts eroded from

the surrounding flats and flanking levees, and bars of bioelastic

sand uinnowed from the ponds, Supratidal '"levees" protrude

above high-tide level and are microbially laminated.

Supratidal flats

Most of the sediment surfaee here is covered by mierobial mat.s

that are typically shrunken into desiccation polygons and

commonly dislodged as ehips or intradasts. Laminated

sediment beneath these mats is fine grained with occasional

coarser interealations that reflect deposition by e,xceptional

storms and. in some regions, by winds blowing off the adjacent

land surface. Beds and nodules of anhydrite precipitate in

these sediments in arid settings. In many areas, the supratidal

zone is the locus of widespread synsedimenlary cementation by

microerystalline aragonite. high-Mg ealcite. or dolomite. This

forms lithified pavements a few centimeters thiek that are

usually broken into intradasts by forces exerted during crystal

growth, groundwater pore pressure, or the roots of halophytic

plants such as grasses and mangroves.

Landward parts of the supratidal zone grade into eolian

deposits, soils or freshwater marshes and lakes, or onlap

bedrock surfaces, depending on the region's geography and

climate. Marshes and lakes, which exist in the more humid

areas and have fluctuating water chemistry, are characterized

NERITIC ( ARBONATE DEPOSlTIONAf ENVIRONMENTS

469

by mierobial mats and stromatolites; these are partially

lithified by high-Mg calcite eement and calcification of organic

substrates, and are interbedded with thin-bedded, locally

bioturbated lime mud and bioelastic and peloidal earbonate

sand deposited during storms. Much of the microbially

laminated sediment shows iL'nestral f\ibric, millimeter- to

centimeler-sized subhorizontal. sheet-like pores formed as

voids bridged by microbial mats or as molds of degraded

mats.

Decimeter-scale teepee structures, consisting of dis-

rupted and overthrust crusts of lithifled, tufa-like fenestral

sediment giving an inverted V-shaped cross section, form in

areas of groundwater discharge (Kendall and Warren. 1987).

These also contain complex generations of internal sediment

and aragonite and high-Mg calcite cements.

Ancienf supratidal facies

Microbially laminated limestone or dolostone. usually uith

desiccation cracks and eoarser rippled layers, is a eommon

peritidal rock type. Intercalated within many microbially

laminated roeks are intraclastie horizons, which are analogous

to pavements of mierobial mat chips or fragments of cemented

crusts in modern supratidal environments. Fenestral lime

mudstone and peloidal grainstone are common and. by

analogy with tidal flats of Florida and the Bahamas, were

probably deposited in moist supratidal "algal marshes" or

around ponds. This facies somefimes exhibits features, such as

pendent fibrous cement, brecciated crusts and tepees, pisolites

and pores with geopeta! sediment floors, suggestive of flushing

by downward-percolating seawater and rainwater and up-

ward-flushing by groundwatcrs in a subaerial environment.

Reefs

There has for decades been an otigoing debate as to what

constitutes an ancient "reef" (Heckel. 1974; James. 1983;

Geldsetzer

etal..

1988: Wood. 200(1), A useful compromise is

that reefs are biologically constructed reliefs which were, like

modern reefs, constructed by large, usually ctonal elements (on

average >5cm in size), and capable of thriving in energetic

environments; mounds are those structures whieh were built by

smaller, commonly delieate and/or solitary elements in tranquil

settings (see Carbonate Mud Mounds). Two terms, bioherms

and biostromes. are commonly used to designate biogenically

constructed geological structures. A biidiertn is a Icns-shaped

reef or mound; a blo.sitvme is a tabular rock body, usually a

single bed of similar composition. Another commonly used

generic epithet with no compositional, size or shape connota-

tion is

carbonate

buildup.

Depositional facies

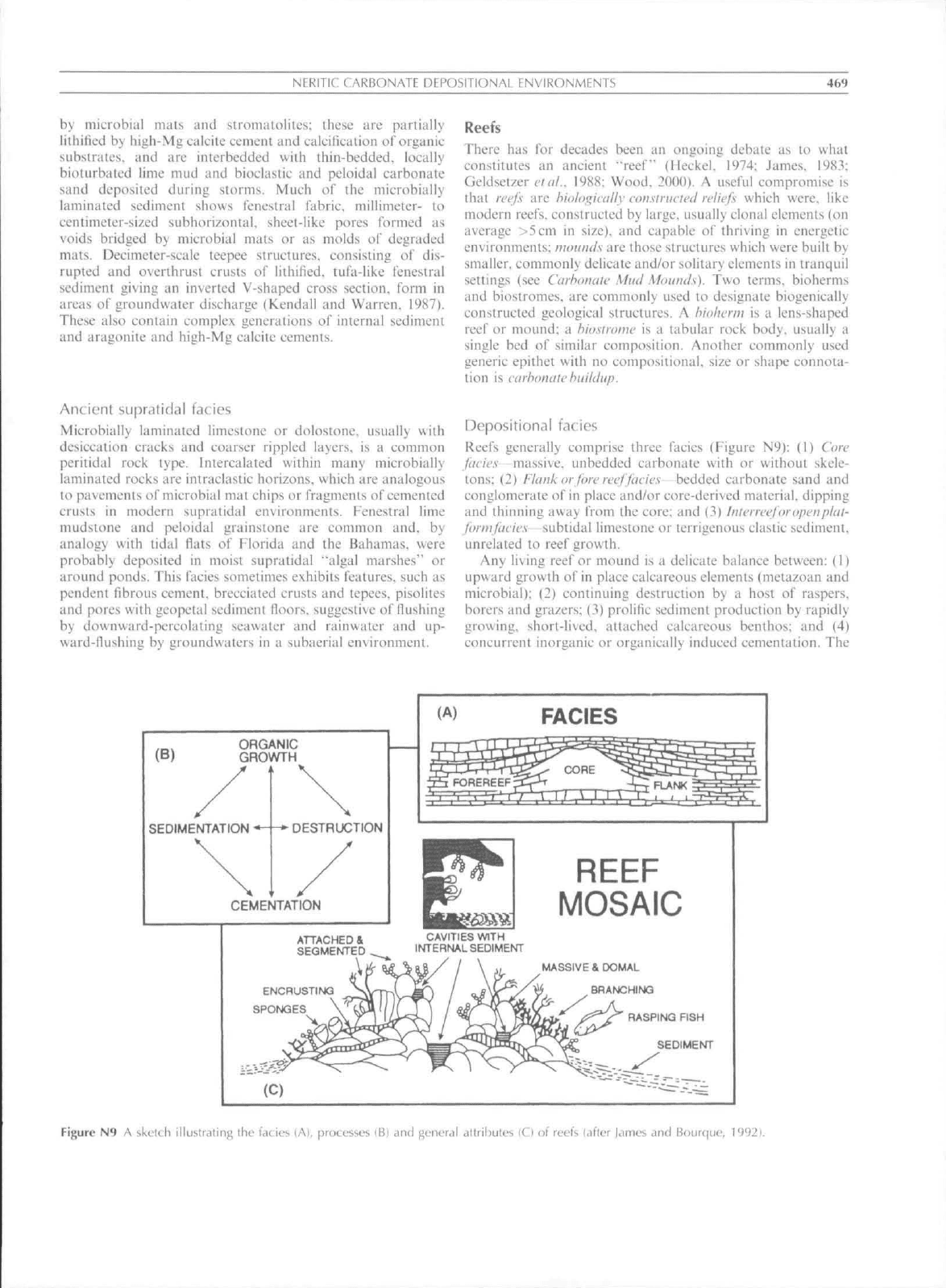

Reefs generally comprise three faeies (Figure N9): (I) Care

facies—massive, unbedded carbonate with or without skele-

tons;

(2) Flank or fore reef facies—bedded carbonate sand and

conglomerate of in place and/or core-derived material, dipping

and thinning away from the core; and (3) Interrcefor

open

plat-

form

facies

subtidal limestone or terrigenous clastic sediment,

unrelated to reef growth.

Any living reef or mound is a delicate balance between; (1)

upward growth of in place calcareous elements (metazoan and

mierobial); (2) continuing destruction by a host of raspers.

borers and grazers; (3) prolifle sediment production by rapidly

growing,

short-lived, attached calcareous benthos; and (4)

concurrent inorganic or organically induced cementation. The

(B)

ORGANIC

GROWTH

SEDIMENTATION

DESTRUCTION

CEMENTATION

(A)

FACIES

ATTACHED &

SEGMENTED

A

CAVITIES WITH

INTERNAL SEDIMEMT

ENCRUSTING

SPONGES

REEF

MOSAIC

MASSIVE

&

DOMAL

BRANCHING

RASPING FISH

SEDIMENT

Figure

N9 A

skekh

illuslr.itirif;

the lat ies lAi,

[jrotesses

(Bi and

f^eiier.il

allributus

tC\ ol

reels (atler lanifs

and

BourciuL'.

J992I

470

NFRITIC CARBONATF DEPOSITIONAl, ENVIRONMENTS

large skeletal metazoans (e.g., corals) generally remain in place

after death, except when so weakened by biocroders that they

are toppled by storms. Their irregular shape and growth habit

rcsLill in roofed-over cavities that can be inhabited by smaller,

attached calcareous benthos. Encrusting organisms growing

over dead surfaces aid in stabilization. Branching reef-builders

can also be preserved in place, but are just as commonly

fragmented by storms into sticks and rods, which form skeletal

conglomerates.

Most sediment is produced by the postmortem disintegra-

tion of segmented (e,g., calcareous green algae) or nonseg-

mented (e,g., bivalves, brachiopods, foraminiiers) organisms.

Additional sediment is generated by biocroders: boring

organisms (worms, sponges, bivalves) produce lime mud;

rasping organisms, generally herbivores (echinoids. fish), graze

the surface creating copious quantities of carbonate sand and

silt. The sedimeni accumulates around the buildups as an

apron, lodges between skeletons as a matrix and filters into

growth cavities as geopetal internal sediment. Rigidity of many

reefs is accomplished by invertebrates and microbes encrusting

or growing on top of one another. Many reefs are also

preferential sites tor synsedimentary cement precipitation (see

Diagetu'si.s). and are hard limestone just below the growing

surface.

Results of these processes can be seen in many Phanerozoic

reefs and mounds, and especially in Mesozoie and Cenozoic

structures, which are decidedly "modern" in composition.

Paleozoic buildups do not appear to have been alTected much

by boring organisms but were typically sites of intense

synsedimentary cement precipitation: some reefs eontain so

much cement that they have been called "cementation reefs".

Precambrian buildups, with their limited biological compo-

nents,

were mainly constructive, clearly fractal in character,

and contained few growth cavities.

The reef growth window

The modern growth window is determined by the combination

offactors that control growth of the major organism, in this case

corals, Hermatypic (reef-building) corals grow in waters

between 18 and 36

"C.

but are best adapted to form reefs in

waters between 25'C and 29°C. Periodic exposure is not

necessarily lethal and some intertidal corals are out of water for

many hours daily. The salinity window ranges from 22%(i to

40%i,

but mosl corals grow best in waters between

25"i'ni

and ?5%o.

Hermalypic, reef-building corals are cnidarians which

contain light-dependent, photosynthetic symbiotic micro-

organisms (zooxantheliae). Light decreases exponentially with

depth and the lower limiis of hermatypic coral and calcareous

green algal growth are 80

m

to 100 m. Beeause they are

mixotrophs corals flourish in nutrienl-impoverished oceanic

regions. Increased nutrient levels, from upwelling on the outer

platform and runolT on the inner platform, lead to dramatic

changes in reef structure; at intermediate levels the animal-

plant symbionts are replaced by more heterotrophic forms and

"fouling organisms" such as filamentous algae, fleshy algae

and small suspension-feeding animals (barnacles and bivalves)

of the heterozoan assemblage. Reefs still grow in such regions

only because herbivores graze back the algae. Fine-grained

suspended sediment limits coral growth because it decreases

light penetration and covers or clogs the polyps. It is difficult to

decouple the effect of fine terrigenous sediment and nutrients

on coral reef growth because they usually occur together.

Scleractinian coral reefs

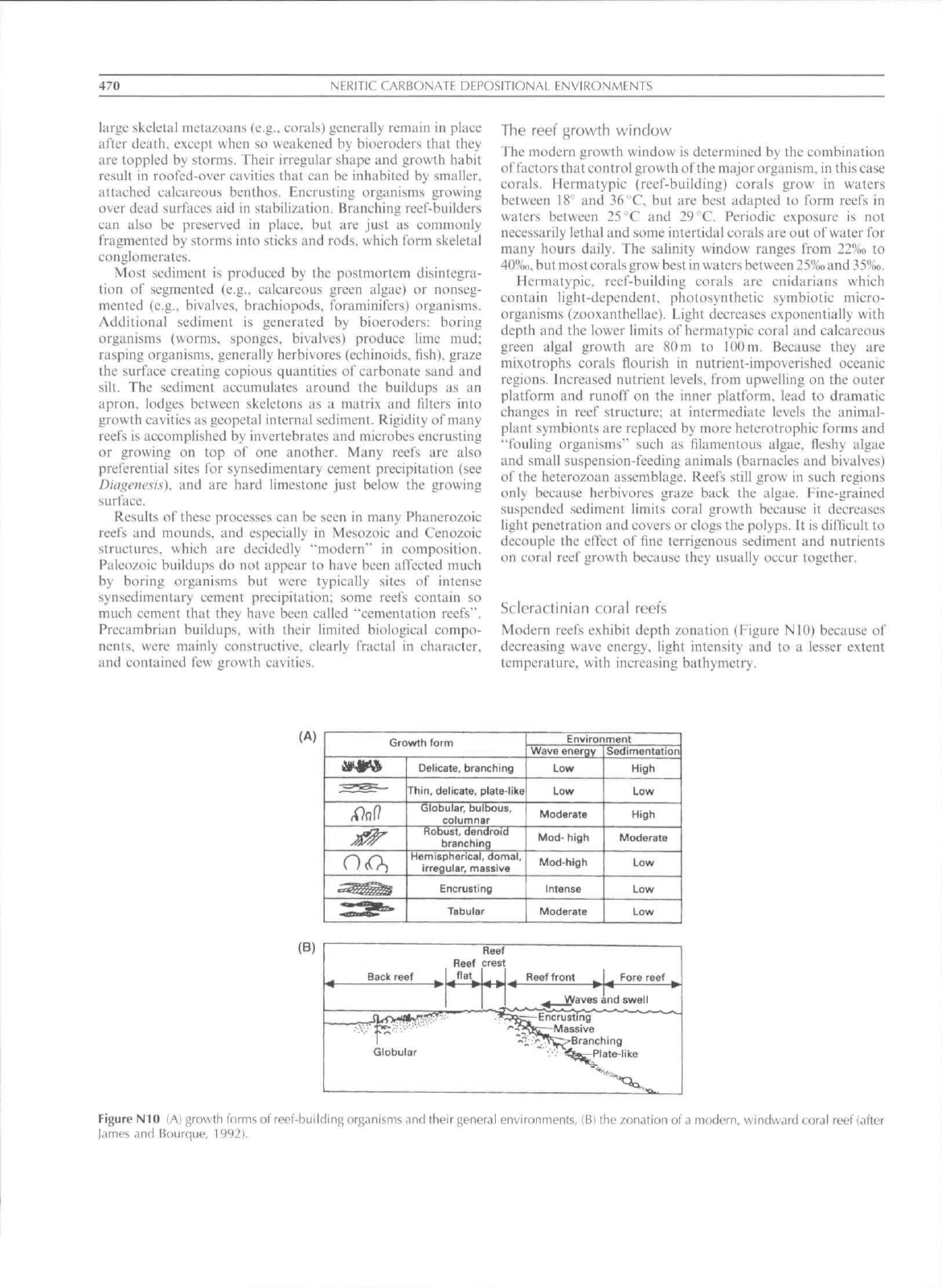

Modern reefs e,\hibit depth zonation (Figure NIC) because of

decreasing wave energy, light intensity and to a lesser extent

temperature, with increasing bathymetry.

(A)

no,

SIP*

wth form

Delicate, branching

Thin,

delicate, plate-like

Globular, bulbogs,

columnar

Robust, dendroid

branching

Hemispherical, domal,

irregular, massive

Encrusting

Tabular

Environment

Wave energy

Low

Low

Moderate

Mod-

high

Mod-high

Intense

Moderate

Sedimentation

High

Low

High

Moderate

Low

Low

Low

(B)

Back reef

Reef

flat

Heet

cres

Globular

^ Reef front

^ Waves

^ Fore reef ^

md swell

:;:^t:--Encrusting

•" ^Jl^K^ M a ss i ve

-•'i^^^^Vt^'Branching

^ -•-• <tar-Plate-like

Figure NIO (A) growlh forms of reef-building organisms and their general environments, IB} the zonation of

a

modern, windward coral reef (after

James and Bourque,

19921.

NFRITIC CARBONATE DEPOSITIONAL ENVIRONMENTS 471

Reefs

on the

leeward side

of

banks

can be

strikingly

different, either because

of

reduced wave activity

or

because

of

"bad water". The

bad

water

is

fortned

on

the

platform

by

fitie-

graincd sediment production, oxygen depletion, heating

or

evaporation.

It is

usually driven

off the

bank downwind,

across

the

leeward margin, inhibiting reef growth

to a

depth

of

several

lOs of

meters. Such shallow leeward margins

ean,

therelbre,

be

bare rock floors covered

by

soft fleshy algae

or

hard coralline algae with active reef growth taking place only

in deeper water, below this interface.

There

is

commonly

a

cross-shelf conation

in

reef composi-

tion that partly reflects

the

outboard decrease

in

fine sediment

and nutrients. Inner shelficcfs

are

chaiacterized

by (I)

quickly

growing corals with

a

high tolerance

for

fine sediment

but

iniable

to

withstand turbulent waters;

(2)

large

and

abundant

heterotrophic sponges:

(3) low

epifaunal diversity;

(4) few

soft

corals:

and

{5)

abundant soft algae

and few

calcareous algae.

Oulciwhelf n'cjs

(in

areas

of

little upwelling)

are

distinguished

by

(I)

slow-growing autotrophic corals whieh cannot with-

stand suspended sediment

but are

adapted

to

high-energy seas:

(2) reduced numbers

o\'

sponges, most

of

which contain

photosynthetic symbionts;

(3)

common tridacnid bivalves

in

the Pacific;

(4)

high epifaunal diversity:

and (5)

prolific

calcareous algae.

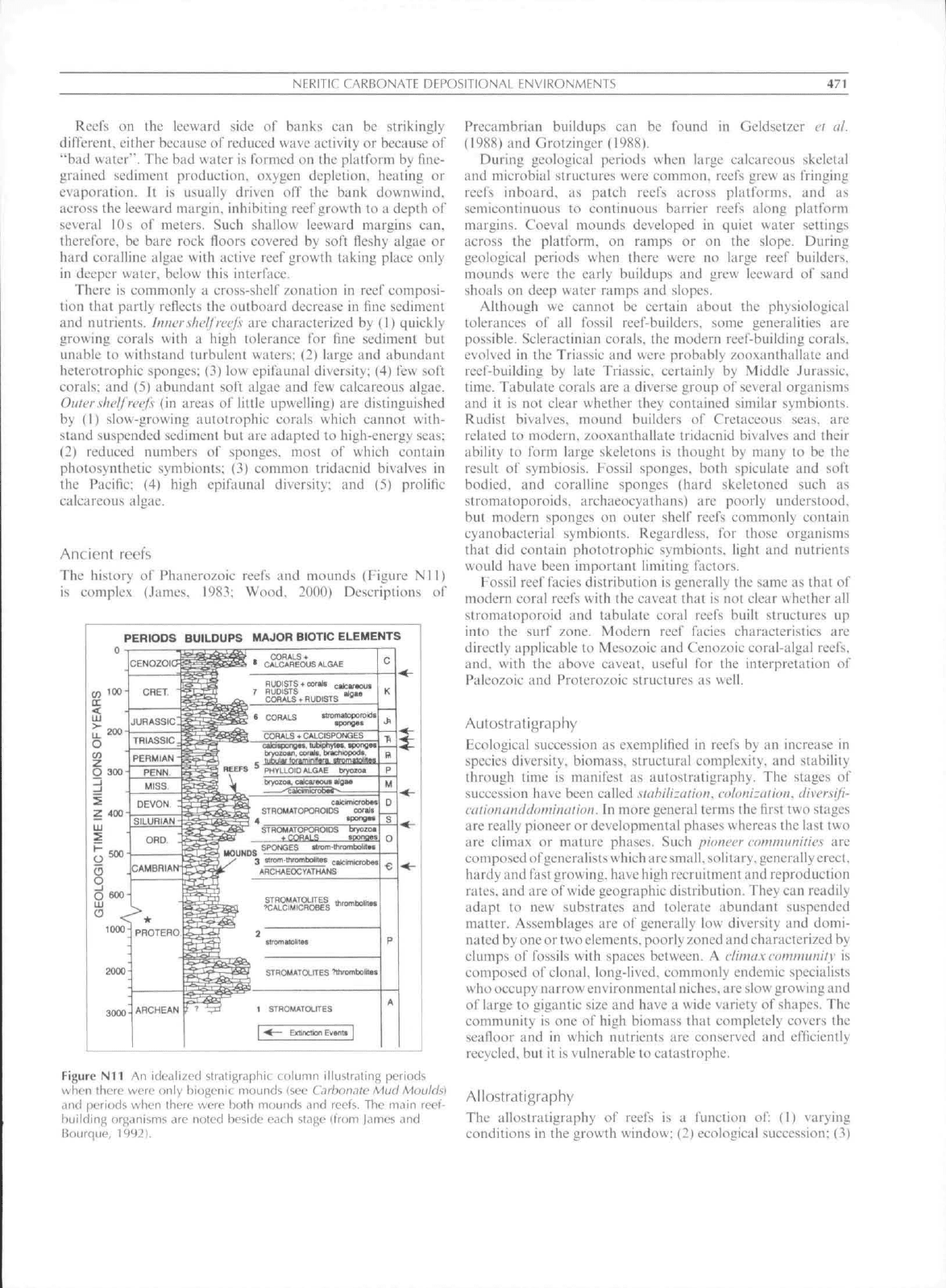

Ancient reefs

The history

of

Phanerozoic reefs

and

mounds (Figure

Nil)

is complex {James,

1983:

Wood, 2000) Descriptions

of

PERIODS

m 100-

UJ

O

O 300-

LL

GEOLOGIC

TIME

2000

300 0

CENOZOKJ-

CHET

-

JURASSIC!

PERMIAN

-

PENN.

MISS.

DEVON.

:

SILURIAN

-

ORD

'.

CAMBBIAN-

*

PROTERO

ARCHEAN

BUILDUPS MAJOR BtOTIC ELEMENTS

g-L.^ REEFS

'

CORALS

.

CALCAREOUS ALGAE

RLIDISTS

JoM^

CORALS-F1UDISTS

"^

CORALS viromatDporoidfi

CORALS

+

CALCISPONGES

bfyoloon,

corals, bractuooods,

PHYU.0 ID ALGAE Ixyoioa

l^^^g

V.

bryoTOSi, calcafoous algav

^^

r?

^33

STROMATOPOROIOS Ctntf

•pong**

STROMATOPOROIDS b(>DI01

SPONGES Blrom-ttvonibolitM

arom.lhiombolnos dcim

AflCHAEOCVATHANS

STROMATOLFTES *mmt_lit«

•ICALCIMICROBES °'™"™'™»

slrom sullies

STROMATOLfTES 'tfvomtiolites

STROMATOLrrES

^— ExttnctiOP Event*

c

K

a

p

M

•

S

0

e

p

A

Figure

Nil

An

idealized stratigraphic column illustrating periods

wW-u there were only f)iogenic mounds (see

Carbonate

Mud

Moulds)

and fjeriuds when there were both mounds and reefs.

The

main reet-

building organisms

are

noted beside each stage (from James

and

Prccambrian buildups

can be

found

in

Geldsctzer

ct al.

(l9S8)and Grotzinger (198X).

During geological periods when large calcareous skeletal

and mierobial strtietures were common, reefs grew

as

fringing

reet^s inboard,

as

patch reefs across platfortns.

and as

semicontinuous

to

continuous barrier reefs along platform

margins. Coeval mounds developed

in

qtiiet water settings

across

the

platform,

on

ramps

or on the

slope. During

geologieal periods when there were

no

large reef builders,

mounds were

the

early buildups

and

grew leeward

of

sand

shoals

on

deep water ramps

and

slopes.

Although

we

cannot

be

certain about

the

physiological

tolerances

of all

fossil reei-builders, some generalities

are

possible. Scleractinian corals,

the

modern reef-building corals,

evolved

in

the

Triassic

and

were probably zooxanthallate

and

reef-building

by

laie Triitssie. certaiitly

by

Middle Jurassic,

time.

Tabulate corals

arc

a

diverse group

of

several organisms

and

it Is not

clear whether they contained similar symbionts.

Rudist bivalves, mound builders

of

Cretaceous seas,

are

related

to

modern, zooxanthallate tridacnid bivalves

and

their

ability

to

form large skeletons

is

thought

by

many

to be the

result

of

symbiosis. Fossil sponges, both spictilate

and

soft

bodied,

and

coralline sponges (hard skeletoned such

as

stromatoporoids. archaeocyathans)

are

poorly understood,

but tnodern sponges

on

outer shelf reefs eommonly contain

cyanobacterial symbionts. Regardless,

for

those organisms

that

did

contain phototrophie symbionts, light

and

nutrients

wotild have been important limiting faetors.

Fossil reef facies distribution

is

generally

the

satne

as

that

of

modern coral reefs with

the

caveat that

is

not

clear whether

all

stromatoporoid

and

tabulate coral reefs built structures

up

into

the

surf zone. Modern reef facies characteristics

are

directly applicable

to

Mesozoic

and

Cenozoic coral-algal reefs,

and. with

the

above eavcat, useful

for the

interpretation

of

Paleozoic

and

Proterozoic structtires

as

well.

Autostratigraphy

Ecological succession

as

exemplified

in

reefs

by an

increase

in

species diversity, biomass. structural complexity,

and

stability

through time

is

manifest

as

autostratigraphy.

The

stages

of

succession have been called slahUizatiou. calonizalion.

cliver.sifi-

cationanddaminalion.

In

more general terms the first two stages

are really pioneer

or

developmental phases whereas the last

two

are etimax

or

mature phases. Stich pionci-r commimities

are

composed ofgeneralists which are small, solitary, generally erect,

hardy and fast growing, have high reeruitment and reproduction

rates,

and are of

wide geographie distribution. They can readily

adapt

to new

substrates

and

tolerate abundant suspended

mutter. Assetnblages

are

of

generally

low

diversity

and

domi-

nated by one

or

two elements, poorly zoned and eharaeterized by

clumps

of

fossils with spaces between.

A

climax comnniniiy

is

composed

of

clonal. long-lived, commonly endemic specialists

who occupy narrow environtnental niehes, are slow growing and

of large

to

gigantic size

and

have

a

wide variety

of

shapes.

The

community

is

one

of

high biomass that completely covers

the

seafloor

and in

which nutrients

are

conserved

and

efficiently

recycled,

but

it

is vulnerable

to

catastrophe.

Allostratigraphy

The allostratigraphy

of

reefs

is a

function

of;

(I)

varying

conditions

in

the growth window; (2) ecological succession; (3)

472

NERITIC CARBONATE DEPOSITIONAL ENVIRONMENTS

antecedent topography: and (4) the rates of sea level rise and

organism growth (Kendall and Schlager, 1981).

Reef Slarl-up can take place: (1) during sea level rise

following exposure: (2) during sea level fall when the seafloor

comes into the growth window: (3) when the seafloor is raised

by mound development into the growth window: (4) when

faetors mimical to reef growth arc turned off.

Keep-up

Reefs

maintained their crests at or near sea level.

tracking sea level rise. Caleh-up

Reefs

began as shallow reefs

which beeame deeper as rise rate exeeeded accretion rate, only

to grow upward and eatch up with sea level. Alternatively, they

started on a deep substrate :tnd then grew up to sea level. Onee

reels ol" either type reached sea level they maintained a near-

surfaee erest or developed a capping facies of subtidal

pavements to storm-ridge deposit.s. At this point growth was

limited to the seaward margin and reefs prograded laterally

over their own reef front and fore reef

sediments.

Give-upReeJs

initially grew as did the others but then sueeumbcd to ehanging

environmental conditions and

died.

All studies note that the

responses of reef growth to sea level rise varied greatly, even

within the same reef.

Reefs can turn otT and die in a variety of situations. The

most obvious reason, that sea level rise was too rapid for the

reefs to keep up. is not the answer. This is beeause reefs ean

have extraordinarily high growth rates that potentially exceed

any rise in sea level cxeept that related to tectonics. Changes in

the growth window are more hkely to be the cause of reefs

giving up. Drounini; (Sehlager. 1981) is submergence ofthe

platform top below the photic zone by a rise in sea level or

shallowing of the photic limit. Alternatively reefs can be killed

by some combination of increased turbidity, nutrient excess or

hot saline waters which swept off the shelves when sea level

flooded the wide shallow platforms (the "bad water"

syndrome).

Basin-facing slopes

Introduction

Carbonate slopes (Cook and Enos. 1977: Macllreath and

James.

1984: Mutlins and Cook. 1986) encompass a suite of

environments whieh pass seaward from shallow water, sunlit,

platform margins and inner ramp environments to the deep.

dark, basin settings. They are variably affeeted with depth by

ehanging seawater chemistry, temperature, pressure and biota.

The best studied carbonate slopes in today's oceans are those

in the northern Bahamas-Florida region, augmented by more

iocal studies in Belize, .lamaica. Grand Cayman, and several

atolls in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

Slope sediment is a variable mixture of autochthonous

benthic biofragments. resedimented, allochthonous material

from upslope and pelagic fallout. The pelagie eomponent is

mostly terrigenous in pre-Jurassie rocks and mostly planktic

carbonate in younger strata. Pcriplalfbrm

ooze

is intermixed

platform-derived and pelagic carbonate muds while hemipela-

gic sfdi

men!

is a mixture of carbonate and terrigenous clastic

material.

Autochthonous sediment

This material includes fecal pellets derived from epifauna

and infauna. seafloor Mg caleite cement, peloidal Mg-catcite

cement precipitated within foraminifer tests, and skeletal

debris associated with biota indigenous to the slope environ-

ment. Silieeous sponge spieules form a loeally important

supply of noncarbonate sediment.

Allochthonous sediment

Sueh sediment is transported to and aeeumulates on the slope

by suspension settling, gravity (resedimented) flow, rock

fall.

and submarine creeping and sliding. Bottom currents, parti-

cularly eontour currents, can winnow and rework these

deposits, or prevent accumulation entirely, resulting sediment

starvation,

submarine dissolution or lithifieation.

Fine-grained

carbonale.s

composed shallow water-derived

particles are transported basinward from shallow water by

tides,

storms, and currents forming concentrated to dilute

sediment-seawater mixtures. These plumes can dissipate, in

which ease material rains down to the seafloor. or progress

downslope as uneonfined and eonfmed dilute turbidity

eurrents.

Such flows ean also move along mid-water density

interfaces

(e.g.,

pycnoclines) from which sediment rains down

on the basin floor.

This sediment is varying proportions of mud-size algal and

inorganically precipitated aragonite needles, blades of Mg

calcite and aragonite. mud- to sand-sized skeletal and

nonskeletal debris, lithoclasts, and bioeroded particles

(e.g..

sponge chips). Jurassic and younger muds are rich in

calcareous plankton while older slope earbonates are mostly

platform-derived sediment. Loeally. eoarser periplatform

sediments eontain gravels and boulder-sized lithoclasts derived

from shallow water facies or carbonate bedrock.

A common lithology in many ancient slope sequences is

interbedded,

finely crystalline, dark grey to black, lime

mudstone and shale, forming evenly and continuously

rhythmic sequences. In places where the carbonate is finely

laminated,

suspension deposition may have occurred within an

oxygen minimum zone that limited bioturbation. Oxygenated

slopes are commonly intensively bioturbated. obliterating

primary sedimentary laminations and possibly encouraging

the formation o\' nodular bedding.

Sediment gravity flow deposits are manifest as carbonate

turbidites. carbonate grain flow deposits and debrites. Most

partieles are polygenetie. from the platform, inner to mid ramp

and the slope.

A hallmark of many earbonate slopes are massive, thick

limestone conglomerates called debriles. debris sheds or ava-

lanehes.

oH.'Hoslromes.

and

mass

hreeeia flows.

A few

decimeters

to several tens of meters in thiekness, sueh deposits are

generally poorly sorted, lack stratification, and have a random

or chaotic clasl arrangement. Some have normal and reverse

grading,

clast alignment near the base, sides or top of the

deposits, local clast imbrication, and swirled domains in whieh

clasts display a gradual change in flat elast orientation. Clasts

are rounded to angular, and sizes vary from gravel- to house-

sized boulders with maximum clast size and bed thickness

commonly being correlated.

Paleomargin proximity is commonly indicated by the most

abundant and thickest conglomerates containing the largest

sizes and varieties of elasts. Polvmiciconghmcrah's result from

the mixing of platform-derived exotic clasts (which may be

variable themselves) with slope-derived clasts and matrix. Oli-

gomiet

conglomerates

are almost always due to erosion and

redeposition of slope limestone in the form of tabular clasts

(limestone chips) and interparticle matrix. Rafts of eoherently

NERITIC CARBONATE ElEPOSITIONAI ENVIRONMENTS

473

bedded,

slope-derived limestone several tens of meters in size

are identical to in situ slope limestones. Sueh rafts beeome

fragmented during progressive downslope transport to yield

matrix and tabular clasts. Sofl-sedimcnt folding, faulting.

fracture cleavage formation and brecciation characterize such

rafts.

Intraformational truncation surfaces, shear zones, and

detached slide masses are all products of slope failure and

form in any of the preeeding facies. The first two provide

evidence for an ancient slope: the

third,

like gravity flows, can

be preserved either downslope or within an adjacent basin.

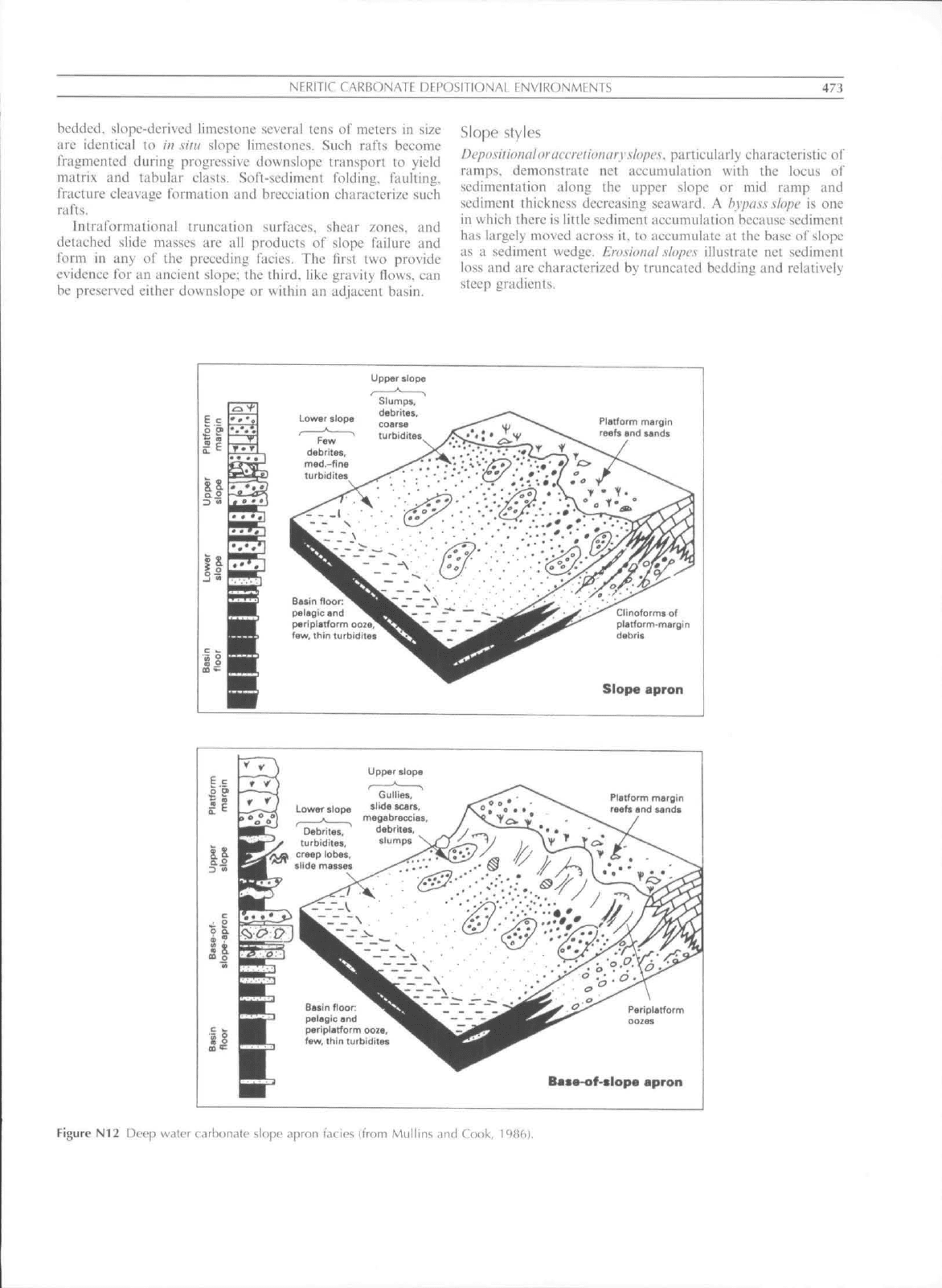

Slope styles

Deposithnaloracereikmary.Khpes. particularly characteristic of

ramps, demonstrate net accumulation with the loeus of

sedimentation along the upper slope or mid ramp and

sediment thickness decreasing seaward. A bypass slope is one

in which there is little sediment aeeumulation beeause sediment

has largely moved across it. to accumulate at the base of slope

as a sediment wedge. Erosional

slopes

illustrate net sediment

loss and are characterized by truneated bedding and relatively

steep gradients.

Upp«c slope

Platform margin

re«ts snd sands

Basin fl

pelagic and

periplatform

few, ihin turbidlisB

Clinoformi of

platform-tnargin

debris

Slope apron

Basin floor

pelagic and

periplatform ooie.

few, Ihin turbidites

Figure N12 Dt't'p wdter f.irbonale slope apron

I'acies

(trom Mullins iind

(~nnk,

474 NERITIC CAKBONATE DEPOSITIONAI. ENVIRONMFNTS

Modern earbonate slopes are generally steeper than their

terrigenous counterparts and tend toward eoncavity with the

angle of the upper slope increasing with slope height.

Steepening of the carbonate slope, results from: (I) reef-

building;

(2) submarine cementation; and (3) shallow subsur-

face lithiiieation. Early lithifieation may act to delay large-seale

failure.

Gradients are steeper (30"-40'") for sediments with

cohesionless. grain-supported fabrics (with or without mud),

than those of paleoslopes dominated by mud-supported,

cohesive fabrics (<15^). Pure muds have slope angles of less

than 5".

Many modern carbonate slopes are typified by numerous

parallel ineised gullies, oriented perpendicular to the margin.

Such gullies form a line

source

of sediment supply from the

plattbrm and upper slope to the lower slope.

Slope sediment aprons

The ultimate sediment accumulations are wedge-shaped to

lenticular bodies that thicken toward the platform margin.

Faeies belts closely parallel the platform margin.

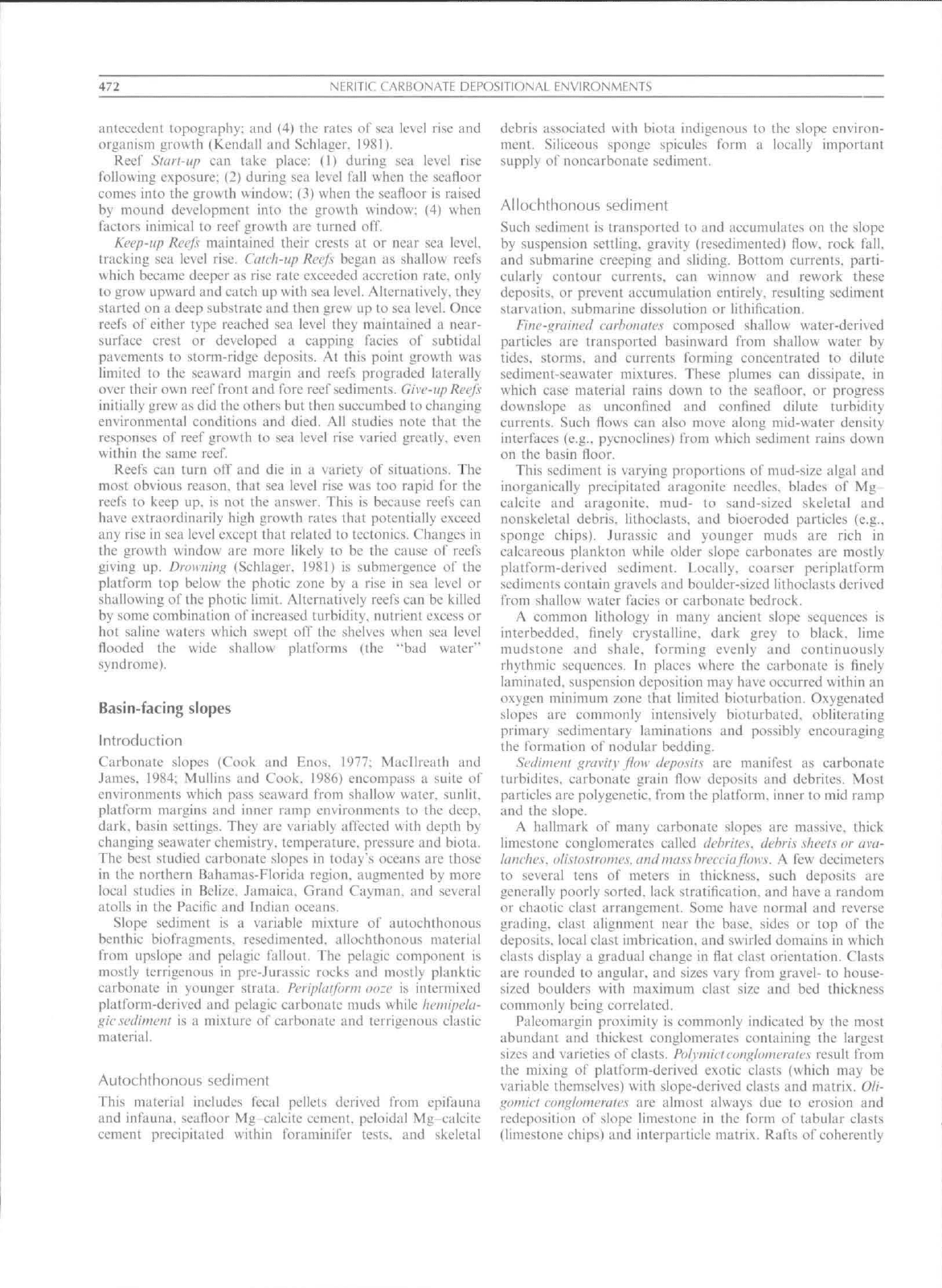

Carbonate slope

apron.\

(depositional slopes) (Figure NI2)

extend without break from the basin along gentle (<4")

gradients up to a shallow water platform margin. A line souree

of platform-derived sediment originates from numerous

ehannels dissecting

shoals,

reefs and islands along the platform

margin.

Downslope sediment transport along such carbonate

aprons is predominantly via unchanneli/ed sheet Hows. These

are like the mid- and outer-ramp facies and the two systems

seem to merge.

Rimmedplalform basi'-of-stope aprons

form downslope from

the platform-slope break along

a

relatively steep (>4 ) margin.

Sediment is supplied from a line source which typically takes

the form of a series of closely spaced gullies transporting

shallow water and slope-derived sediment through some

portion of the upper to middle (bypass) slope. Sediment

emerging from a gullied slope initially follows a dispersal path

outlining a series of small, interleaved fan-shaped deposits

while broadly defining platform margin-parallel facies belts.

As with earbonate slope aprons, systematic vertical sequences

are not expected.

Open (imrimmed)

platform

aprons

occur in both warm and

cool-water realms. In warm-water settings, because the plat-

form margin is below depths at which the carbonate factory

operates, sueh sediment aprons are likely to be dominantly

pelagie in origin. In cool-water settings, however, where the

sediment factory is typically deeper, the slopes are in part

depositional. Mass-wasting deposits inelude pelagic turbidites

and debrites. the latter of which can contain clasts derived

from the platform margin or fragmented beds of early lithified

pelagite. The generally finer-grained nature of the deeper

platform margin sediment implies that submarine eementation

(and therefore production of elasts) may not be as important

as along shallower rimmed platform margins. Pre-Mesozoie

aprons adjacent to open platform margins are argiliaeeous.

Carbiinale

submarine

fans appear to be rare in the rock

record,

but several have been described from the Paleozoic. No

modern-day examples have been documented.

Stratigraphy

Sinee so mueh of the sediment comes from the platform ihe

stratigraphie style of slope deposits closely retlects conditions

on the platform. Abundant allochthonous carbonate generally

signals a healthy, generally prograding platform while starved

carbonate or just shale usually means exposure, rapid

accretion or subsidence of the piatform below the zone of

optimum production.

Noel P. James

Bibliography

Balliiiisl,

R.CJ.C,

1*^75.

Ccirhdiiciif

Scclinieins

iiinl Tiicir

Dicigencsis.

Elsevier.

Btirchette. T.P.. and Wright. V.P.. 1492. Carbonate ramp deposilional

systems. Scilimciitary

Geolo}^y.

79;

.'^-57.

Cook. H.E.. and Enos. P. (eds.). 1977.

Dvep-naivi-

CarbonateEnviioii-

luenis. Soeiely of Hconomie Paleontologists and Mineralogists.

Speeial Publication. 23. 336pp.

Geldsetzer. H.H.J.. James. N.P.. and Tebbtitt. G. (eds.). 1988.

Reefs:

Ctinaihi and Atljoceni Areas. Canadian Society ol" Petroletim

Geologists. Memoir 13, 775pp.

Ginsbiirg.

R.N. (ed.). 1975. Tidal

Deposits:

A

Cusehot>k

of

Recent

Examples and Fossil

Counterpiirls.

Springer-Verlag.

Go Id hammer, R.K.. Dunn. P.A., and Hardfe. L.A., 1990. Deposilional

cycles, composite sea-level changes, cycle stacking patterns, and the

hierarchy of stratigriiphic Ibrcing: examples from alpine Triassic

platform carbonates. Geolnviial Sinietxaf

.Aiiicriva

Biilivtin. 102:

535 562.

Grot;?^ingt.T. J.P., 19S8. Piccambrian reel's. In

Reefs,

Canada ami

Adjacent

Areas.

Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists. Memoir

13.

pp. 9 12.

Hallock, P., and Schlager. W.. 1986. Nutrient e.\cess and the demise of

coral reefs and earbonate platforms.

Ptiiniii.s.

1: 389 398.

Hardie. L.A.. and Shinn, E.A., 19K6. Carbonate depositional environ-

ments, modem and ancient. Part 3: liJal Hals.

Colorado School

of

Mines.

Quarterly. 81: 74pp.

Hardie. L.A. (ed.), 1977.

.ScdinicntaUon on

rlic

Modern CarbontiteTtdal

Flals af Nortlnvcsl .Amlros Islanil, Bahamas. Johns Hopkins

University. Studies in Geology 22. 202pp.

Heckel.

P.H.. 1974. Carbonate buildups in the geologic reeord: a

review. In Laporte. L.H. (ed.).

Reefs

in

Tinw and

Space.

Society of

Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Special Publication.

18.

pp.90 155.

James. N-P.. 1983- Reef

environmeni.

In Seholle. P.A.. Beboiit. D.G..

and Moore. C.H. (eds.). Carbonate Deposilional

Environments.

American Association of Petroleum Geologists. Memoir }•}.

pp.

345-440.

James, N.P.. and Bone. Y.. 1991. Origin of a cool-uater. Oligo-

Mioeene deep shelf limestone. Eucla Platform, southern Australia.

Seclinienlologv.

38: 323 341.

James. N.P.. and Kendall. A.C.. 1992. Introduction to carbonate and

evaporite faeies models. In Walker. R.G.. and James. N.P. (eds.).

Fades Models

-

Respon.se

lo

Sea Level

Change.

Geological Associa-

tion of Canada, pp. 265-276,

James. N.P.. and Bourque.

P.-A..

1992. Reefs and mounds. In Walker,

R.G., and James. N.P. (eds.).

Facies .Models Re.sponselo Sea Level

Change.

Geological Association of Canada, pp. 323-348.

James. N-P., and Clarke. J.D..A. (eds.). 1997.

Coot-Water

Carbonaies.

SRPM.

Special Publication, 56. 440pp.

Kendall.

C.G.St.C. and Warren. J.. 1987. A review ofthe origin and

setting of tepees and their associated fabrics.

Sedimentology.

34:

1007-1028.

Kendall.

C.G.St.C and Sehlager. W.. 1981. Carbonates and relative

ehanges in sea level. Marine

Geology.

44: 181-212.

Laportu,

L.F. (ed.). 1974, Reels in Titne and

Space.

Soeiety of Eeonomic

Paleontologists and Mineralogists. Special Publicaiion, 18. 256pp.

Mcllreath.

I.A.- and James, N.P.. 1984. Carbonate slopes. In Walker.

R.G.

(ed,|.

Fades

Models. Geoscience Canada Reprint Series I.

pp.

245-257.

Mnllins. H.T.. and Cook. H.E.. 1986. Carbonate apron models:

alternatives to the submarine fan model for paleoenvironmenlal

analvsis and hydroearbon exploration.

Sediineniarv

Geology.

48:

37-79,