Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MELANGE; MELANGE

435

presence of blocks of varied lithologies and sizes supported by

a fine-grained matrix."

Interpretations

Proposed melange origins fall into three large categories. In the

first group are interpretations that appeal to gravitationally

driven movement on slopes to disrupt bedding in sedimentary

components and to mix the blocks and matrix. Such processes

include slides, slumps, and debris-flows. The term "olistos-

trome" (Flores, 1955, 1956), literally "slide layer," describes a

melange, with or without fabric, interpreted to be formed by

slope processes. In the second category are processes, such as

fluid overpressuring and diapirism, that occur within a pile of

sedimentary rocks, and result in disruption and mixing without

necessarily penetrating to the Earth's surface. Thirdly, there

are processes related to faults that are rooted at depth in the

lithosphere, including subduction zones and transform faults.

In attempts to distinguish between these potential origins,

investigators have typically appealed to a variety of lines of

evidence, studying both the internal fabric and structure of

melanges, and the external contacts and geometry of mapped

melange bodies.

Features and origin of blocks

Observations of the internal fabric of melanges can provide

information on the rheology of the blocks and matrix and may

therefore help to constrain the mode of formation.

Many melanges preserve evidence for the process of

fragmentation that has produced blocks. In some cases it is

possible to observe partially fragmented beds cut by brittle

surfaces. These surfaces may be either extensional or shear

fractures, that produce irregular shapes and trains of

fragments derived from an original block or bed (e.g.. Cowan,

1982).

If fractures cross-cut grains, cements or veins in the

bloeks, this may indicate a post-lithification origin for the

structures, and that fragmentation occurred at depth. Where

extensional fractures occur, matrix may penetrate into the

blocks producing veins that are partially or completely filled by

shale. This has been interpreted as an indication of the

presence ofa fluid matrix, but in other cases it has been shown

that matrix was already in a compacted state, with strong

fissility, before it penetrated into veins (e.g., Waldron et al.,

1988).

Whatever the state of lithification, it is clear that

elevated fluid pressures can play a role in promoting brittle

fracturing by reducing the effective normal stress on potential

fracture planes.

Not all blocks are produced by fracturing. In some cases,

disruption of bedding in sedimentary protoliths leads to the

dispersion of individual grains or highly attenuated beds into

the melange matrix. Fragments produced in such circum-

stances have less angular outlines, typically appearing as lens

shapes or "phacoids." The presence of phacoids is an

indication of deformation that was ductile at mesoscopic

seale; however, phacoids in unmetamorphosed melanges do

not typically show evidence for intracrystalline plastic defor-

mation at microscopic scale. In some melanges, blocks are

connected by highly thinned "wisps" representing attenuated

beds (e.g., Byrne, 1984); microscopic examination indicates

that such wisps are typically formed by disaggregation, and

not by grain breakage or plastic flow (Brandon, 1989).

Some melanges contain blocks from diverse sources,

including intrusive igneous and metamorphie lithologies (e.g.,

ophiolites and blueschists) that cannot have formed in

proximity to a lower grade or purely sedimentary matrix.

Cloos (1982) suggests that such "exotic" blocks are incorpo-

rated by large-scale fiow within an accretionary wedge.

However, incorporation as large sedimentary clasts derived

from fault scarps or mass flows that incorporate older rocks at

the Earth's surface is a possibility that is difficult to eliminate,

especially in tectonically active environments such as subduc-

tion complexes and collision zones.

Fabric and origin of matrix

Matrix fabrics in melanges are extremely variable. Some

melanges lack matrix fabric; in these cases it is generally clear

that the matrix formed by flow of wet sedimentary material. In

most cases some fabric is present, and typically this takes the

form ofa scaly foliation (Moore etal., 1986), characterized by

anastomosing planes surrounding lenticular bodies of fine-

grained, fissile material. Foliation surfaces are typically

polished and may show sliekenside striations that indicate

sense of shear. Some such surfaces may be traceable into faults

or shear zones that dismember blocks. Larger scale fabrics may

be present: in many melanges the matrix is heterogeneous, and

can be divided into domains of varying color, texture, etc.,

reflecting different protoliths. The domains are typically highly

elongated in map outline, and may contribute an overall

foliation to the map pattern, and an overall stratification to the

melange. Such stratification has been used as an indicator of

sedimentary origin (Steen and Andresen, 1997), but it is

quite possible to envisage the development of large-scale

foliation during accretion and deformation in a subduction

zone,

so such inferences are probably unwarranted. Other

melanges display more continuous fabrics such as slaty cleavage

or metamorphic foliation; in many cases it can be shown that

these fabrics post-date the mixing and fragmentation processes

and may be unrelated to the formation of the melange.

Overall geometry of melange units

Given the difficulty of using arguments based on internal

fabric to distinguish between possible origins, arguments based

on contacts and the overall geometry of melanges often

provide a better basis for distinguishing between possible

modes of origin.

Most helpful are clear stratigraphic contacts either at the

base or top of a melange body. Brandon (1989) emphasizes

evidence from depositional basal stratigraphic contacts in

attributing an olistostromal origin to melanges of the Pacific

Rim Complex of Vancouver Island. Swarbrick and Naylor

(1980) describe interbedded sediments between melange units

in Cyprus, that indicate that the melange is clearly stratified.

Pini (1999) describes tabular bodies with fabric that form part

of a stratigraphic succession and are therefore identified as of

sedimentary origin, despite the presence of scaly fabrics.

Melanges of diapiric origin may also be identified based on

large-scale geometry. Orange (1990) describes the variations in

fabric within the Duck Creek melange of the Olympic

Peninsula, Washington, tracing a transition from margins

with pervasive scaly foliation and inequant phacoidal blocks,

to a core with poorly developed foliation, and equant, angular

blocks. Using fold asymmetries. Orange (1990) is able to

436

MICRITIZATION

demonstrate opposing senses

of

shear

on

opposite sides

of the

melange, further supporting

an

origin

by

diapirism.

Melange formation

by

tectonic processes

in

fault

or

shear zones

is

most easily demonstrated

by

regional seale

cross-cutting relationships along fault zones. Pini (1999)

was

able

to

show such relationships

for

units

in the

Apennines,

tenned tectonosomes. Orange (1990) described

the

Hogsback

melange

of

the Olympic Peninsula, concluding that shear-zone

origin

is

indicated

by a

combination

of:

consistent foliation

in

map-pattern, consistent fold vergence, increase

in

foliation

intensity toward

the

center

of a

melange,

and

tight clustering

of clast long-axis directions throughout

the

unit.

Conclusion

Units described

as

melange undoubtedly have

a

variety

of

origins. Field

and

thin-section evidence

may

provide informa-

tion about

the

lithification state

of the

material

at the

time

of

fragmentation and/or mixing,

but

only

in

cases where there

is

clear evidence

for

prior burial

and

lithifieation

can a

deep-

seated, tectonic origin

be

inferred. Many melanges involve

some process

of

deformation

of wet or

incompletely lithified

material, either within

a

gravity-driven slump

or

debris flow,

within

a

diapir,

or

within

a

teetonic accretionary terrain

in

which effective stresses

are

reduced

by

high fluid pressures.

The

products

of

these processes (boudinage, brittle fracturing, scaly

i"abrics) appear similar

in all

three settings. Under such

circumstances, determining

the

origin

of a

melange depends

on careful recording

of

variations across

the

melange body

and

documentation

of

contact relationships.

John W.F. Waldron

Bibliography

Brandon,

M.T., 1989.

Deformational styles

in a

sequence

of

olistostromal melanges, Pacific

Rim

Complex, western Vancouver

Island, Canada.

Geological

Soeiety of Ameriea Bulletin, 101:

1520-

1542.

Byrne,

T.,

1984. Structural geology

of

melange terranes

in the

Ghost

Rocks Formation, Kodiak Islands, Alaska.

In

Raymond,

L.A.

(ed.),

Melanges. Their Nature, Origin

and

Signifieanee. Geological

Society

of

America, Special Paper, 198,

pp.

21-52.

Cloos,

M., 1982.

Flow melanges: numerical modeling

and

geological

constraints

on

their origin

in the

Franciscan subduction complex,

California.

Geological

Soeiety of Ameriea Bulletin, 93: 330-345.

Cowan, D.S., 1982. Deformation

of

partly dewatered

and

consolidated

Franciscan sediments near Piedras Blancas Point, California.

In

Leggett,

J.K.

(ed.).

Trench

andForeare

Geology.

Geological Society

of London, Special Publication,

10, pp.

439-457.

Flores,

G.,

1955.

Les

resultats

des

etudes pour

la

recherche petrolifere

en Sicilie: discussion.

In

Proceedings, Fourth World Petroleutn

Congress. Section l/A/2. Rome: Casa Editrice Carlo Columbo,

pp.

121-122.

Flores,

G.,

1956.

The

results

of the

studies

on

petroleum exploration

in Sicily: discussion. Bollettino

Del

Servizio Geologieo d'ltalia.

78:

46-47.

Greenly,

E.,

1919. TheGeologyof Anglesey, Geological Survey

of

Great

Britain, Memoir,

I.

Hsu,

K.J.,

1968.

The

principles

of

melanges

and

their bearing

on the

Franciscan-Knoxville paradox. Geologieal Soeiety

of

America

Bulletin.

79:

1063-1074.

Hsu,

K.J.,

1974. Melanges

and

their distinction from olistostromes.

In

Dott,

R.H., and

Shaver,

R.H.

(eds.). Modern and Aneient Geosynet-

inal Sedimentation. Society

of

Economic Paleontologists

and

Mineralogists, Special Publication,

19, pp.

321-333.

Moore,

J.C,

Roeske,

S.,

Lundberg,

N.,

Schoonmaker,

J.,

Cowan,

D.S.,

Gonzales,

E., and

Lucas,

S.E.,

1986. Scaly fabrics from Deep

Sea Drilling Project cores from forearcs.

In

Moore,

J.C.

(ed.).

Structural Fahrie

in

Deep

Sea

Drilling Project Cores frotn Foreares.

Geological Society

of

America, Memoir, 166,

pp.

55-68.

Orange,

D.L., 1990.

Criteria helpful

in

recognizing shear-zone

and

diapiric melanges; examples from

the Hoh

accretionary complex,

Olympic Peninsula, Washington. Geological Society

of

America

Bulletin.

102:

935-951.

Pini,

G.A., 1999.

Tectonosomes

and

Olistostromes

in

the Argite Seagliose

of the Northern Apennines. Geological Society

of

America, Special

Paper,

335.

Raymond,

L.A.,

1984. Classification

of

melanges.

In

Raymond,

L.A.

(ed.).

Melanges: Their Nature, Origin

and

Signifieanee, Geological

Society

of

America, Special Paper,

198, pp. 7-20.

Silver,

E., and

Beutner,

E., 1980.

Melanges—Penrose Conference

Report. Geology,

8:

32-34.

Steen,

0., and

Andresen,

A., 1997.

Deformational structures

associated with gravitational block gliding: examples from

sedimentary olistoliths

in the

Kalvag Melange, western Norway.

Ameriean Journatof Seienee, 297: 56-97.

Swarbrick,

R.E., and

Naylor,

M.A., 1980. The

Kathikas melange,

southwest Cyprus: Late Cretaceous submarine debris fiows. Sedi-

mentology,

27:

63-78.

Waldron, J.W.F., Turner,

D., and

Stevens,

K.M., 1988.

Stratal

disruption

and

development

of

melange. Western Newfoundland:

effect

of

high fluid pressure

in an

accretionary terrain during

ophiolite emplacement. Journalof StrueturalGeology,

10:

861-873.

Cross-references

Debris Flow

Deformation

of

Sediments

Gravity-Driven Mass Flows

Mass Movement

MICRITIZATION

Bathurst (1966) coined

the

term "micritization"

in

reference

to

a process

of

alteration

of

original skeletal grain fabric

to a

cryptocrystalline texture

by

repeated algal microborings

and

subsequent filling

of the

microborings

by

micritic precipitates.

Bathurst

was

simply applying Folk's (1959) term

for

crypto-

crystalline carbonate (<4nm) mierite—a contraction

of the

words microcrystailine calcite—to describe

a

process

of

textural diminution

in

carbonate grains.

In

fact. Wolf (1965)

used

the

term "grain-diminution"

to

describe

the

early

alteration

of

crustose coralline algal cellular skeletons

to

mierite. Bathurst, however,

did not

accept recrystallizated

mierite

in his

definition

of

"micritization", which

he

wanted

to

restrict

to

referring

to the

process

of

microboring

and

subsequent precipitation

of

mierite infill. Bathurst's idea

became very popular (e.g., Lloyd,

1971;

Gunatilaka,

1976;

Kobluk

and

Risk, 1977). Subsequently, Friedman (1985),

pointed

out

that Folk (1959, 1962) introduced

the

term mierite

to describe microcrystailine ooze matrix,

not

textural altera-

tion.

He

felt that Bathurst

and

others were misusing Folk's

terminology.

Despite

the

concerns about

the

original intentions

of

authors when they introduced

the

terms mierite

and

micritiza-

tion, Alexandersson (1972) indicated that there

was a

need

for

the broadest

use of

both terms.

He

proposed that

the

term

mierite should

no

longer have

"any

mineralogical implica-

tions"

(p.206)

and it

should

be

used simply

as a

textural term.

Alexandersson further suggested that micritization should

refer

to an

alteration

"of a

pre-existing fabric

to

mierite" with

"no genetic implications" (p.206).

To him,

micritization

MICKlTIZATiON 437

included all proeesses involving the destruction of an ordered

crystallographic fabric to a disordered mieritie texture, with

either a decrease or increase of crystal size. Most reeent studies

of the alteration of carbonate grains have accepted Ale.\an-

dersson's broad defuiitions (e.g.. Land and Moore. 1980; Reid

elul.. 1992: Reid and Macintyre. 1998).

As mcniioncd earlier. Bathurst (1966) suggested that the

process responsible for micritization of carbonate grains was

algal mieroboring and subsequent precipitation of mierite in

open borings. Earlier studies based on light microscopy had

concluded that the cryptocrystalline textures in many shallow-

water carbonate sediments were the result of reerystallization

(e.g., Illing. 1954; Purdy. 1963, 1968; Pusey, 1964; Winland.

1969).

However, for almost two decades after Bathurst's initial

report, shallow-water marine carbonates were generally

thought to be stable, with micritic textural alterations formed

by boring and infilling.

More recently, porc-watcr chemical studies have indicated

that extensive alteration of carbonate sediments is taking place

in shallow tropical waters (e.g.. Morse eta!,. 1985; Walter and

Burton. 1990; Rude and Aller. 1991: Walter etal.. 1993;

Patterson and Walter, 1994). In addition a series of detailed

petrographie and mineralogical sttidies have illustrated that

micriti/ation by recrystallization is widespread in carbonate

grains fotind on the seafloor of tropical shallow waters (Reid

etal.. 1992; Reid and Macintyre. 1998). Macinytre and Reid

also discovered that the original skeletal needles of the green

alga Hatitm-ilaincrassata (Maeintyre and Reid. 1995) and the

porcelaneous foraminifera Archaiasati^ntlatis (Macintyre and

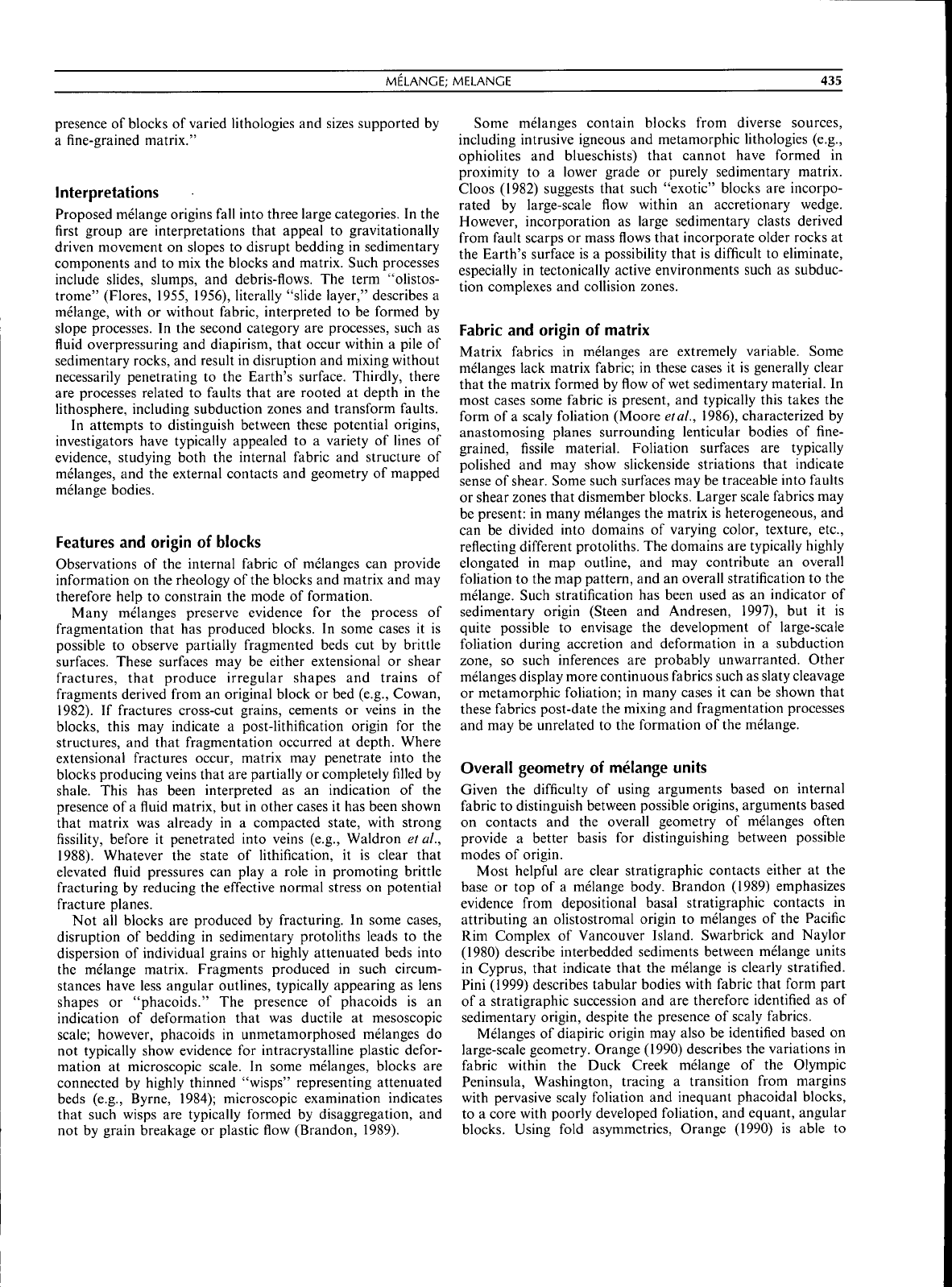

Reid, 1998) are recrystallizing to titiiiiiiiierlte (crystals <1 nm

after Folk, 1974) while these organisms are still alive

(Figure Ml 1(A),(B)). In vivo micritization of carbonate

skeletons is a textural alteration only and does not involve

changes in mineralogy. In both of these studies the micritiza-

tion process uas thought to be related to the breakdown of the

skeletal needles into their original polycrystalline aggregates or

domains, which were deposited in organic envelopes that

controlled the needle shape. Degradation of these organic enve-

lopes and alternating conditions of precipitation and dissolu-

tion caused by reversals on CO2 partial pressures associated

with changes in photosynthesis and respiration in Halitneda

(Macintyre and Reid. 1995) and algal symbionts in the

foraminifera (Macintyre and Reid. I99S). may have resulted

in the micriti/ation of the skeletons of these living organisms.

Further studies of Haliinctla and poreelaneotis foraminifera

grains deposited on the shallow tropical sealioor indicate that

the micritization of skeletal needles continues after death, with

extensive formation of minimicritc (Reid and Maeintyre.

1998).

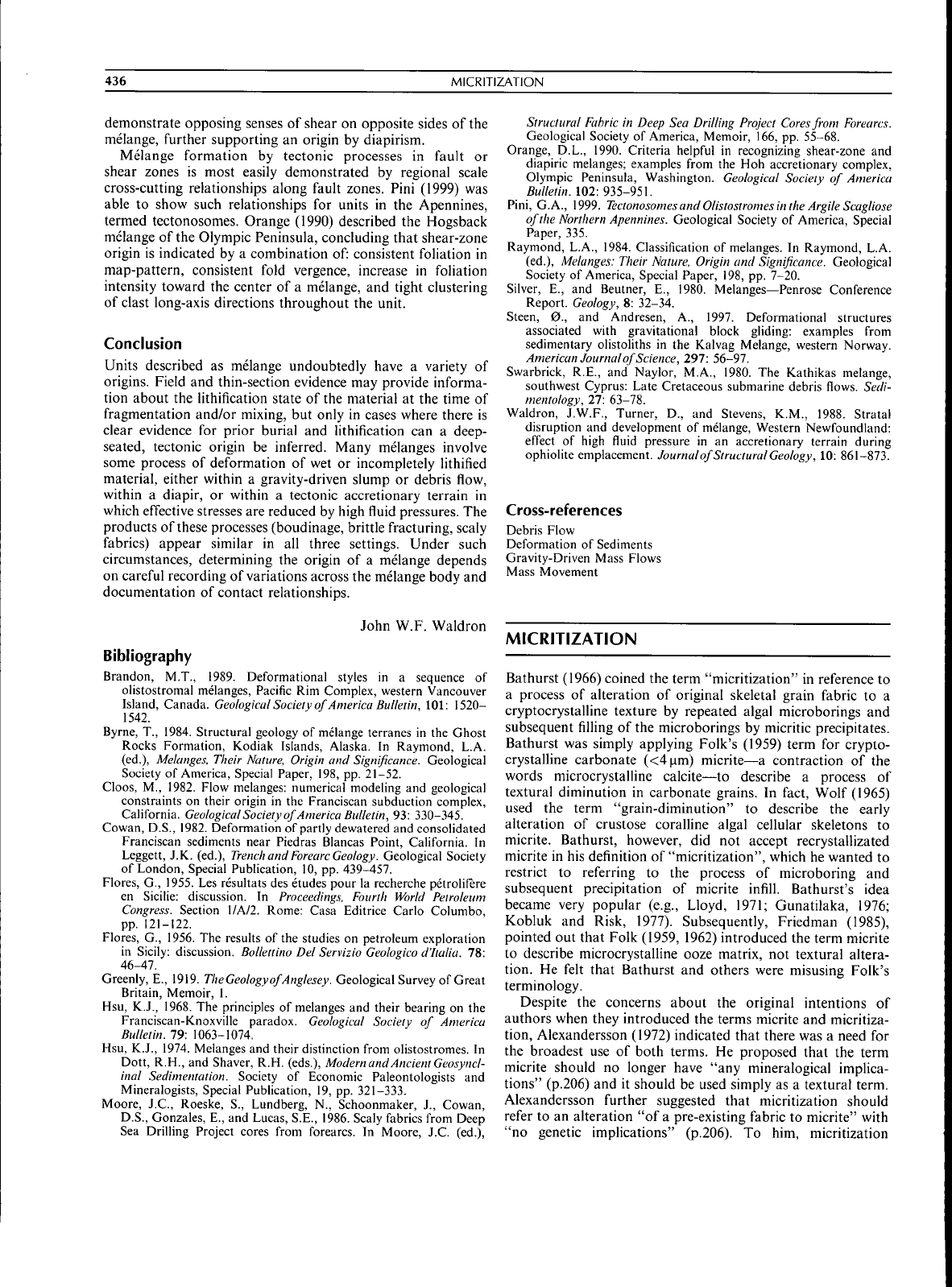

As the micritization process continues, the anhedral

equant minimicrite tends to increase in size to form subhedral

blocky crystals of mierite (Figure MI2). This continuing

micritization of carbonate sediment grains can involve miner-

alogical changes and "(ogether with concomitant cavity filling

results in the gradual obliteration of skeletal elements and the

formation of micritized grains wilh little evidence of original

skeletal structure" (Reid and Macintyre. 1998, p.945). The

processes responsible for this mieritization of carbonate

sediment grains may include organic alteration of pore-water

chemistry., or reduction of high free stirface energies associated

with the increase in crystal size.

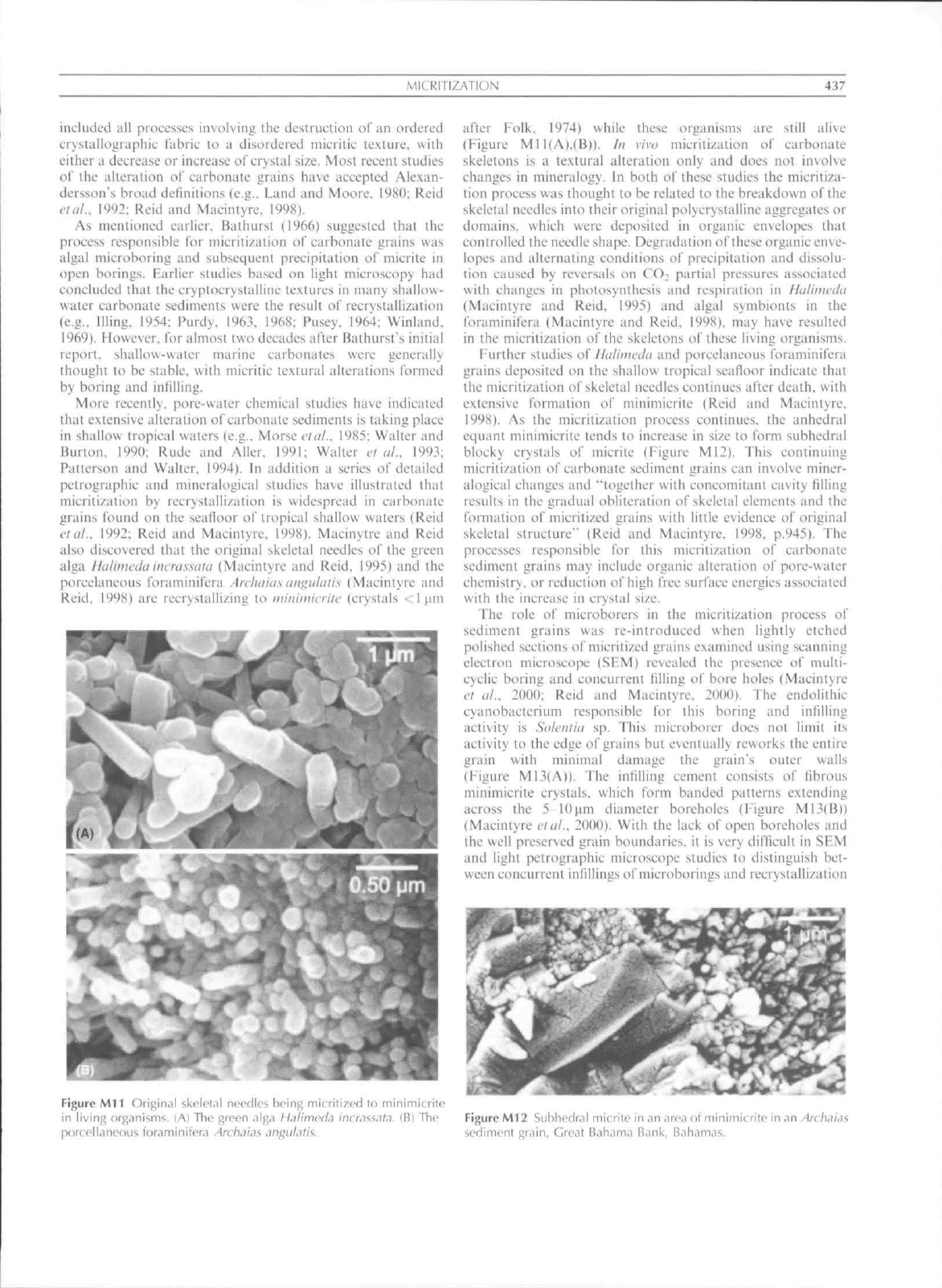

The role of microborers in the micritization process of

sediment grains was re-introduced when lightly etched

polished sections of mieritized grains examined using scanning

electron microscope (SEM) revealed the presence of multi-

cyclic boring and concurrent filling of bore holes (Macintyre

er al., 2000; Reid and Macintyre. 2000). The endolithic

cyanobacterium responsible for this boring and infilling

activity is Solentia sp. This microborer docs not limit its

aetivity to the edge of grains but eventually reuorks the entire

grain with minimal damage the grain's outer walls

(Figure MI3(A)). The infilling cement consists of fibrous

minimicrite crystals, whieh form banded patterns extending

across the 5 lO)jm diameter boreholes (Figure MI3(B))

(Macintyre

('/(//..

2000). With the lack of open boreholes and

the well preserved grain boundaries, it is very diffieult in SEM

and light petrographic microscope studies to distinguish bet-

ween concurrent infillings of mieroboHngs and recrystallization

Figure Mil Original skelefdl needles being micritized to minimfcrile

in

livin^^

organisms. lAl The green jiga Hiilimech incr^is^tn. (Bl The

|)(ir(cll.ine()us foraminiler.i Arch.ii.is n

Figure Ml2 Suhhedral micrilc in an area (if minimi( rite in

<in Arc

h.

sediment grain. Great Bahama Bank, Bahamas.

438

.MICRITIZATION

(A)

Figure

M13

Scanning electron microscopL' photomicrographs

of

etched ihin sections showing grains micritized

by the

cndulrthic

cyanobaclerium Solenlij

sp. (A)

Grain almost completely micritized

by ixiring

and

infilling action

ot

Solentia

sp.

Note that ihcre

is

very

little damaRG

to the

origin,il grain boundaries.

iB)

Detail

of

cyanob.ictcri.il mirrobnrings showing banded minimicrile infillings.

in the formation of micritized carbonate grains (Reid and

Macintyre, 2000).

Summary

(1) Micritization of carbonate sediment grains in shallow-

water tropical seas is widespread forming micriiic grains,

which commonly show no evidence of original structure.

(2) Micritization of carbonate skeletons can be initiated when

the organism is still alive.

(3) The breakdown of original skeletal needles to form

minimicritc in living organisms likely involves both the

destruction of the organic envelopes, in which the needles

are originally formed and changing internal chemical

conditions. No mineralogicai changes of the skeleton

occur during this in vivo micritization.

(4) The micritization of skeletal grains continues after

skeletons are deposited on the seafloor. Postmortem

mieritization involves the formation of anhedral mini-

mierite and subhedral mierite and may include changes in

mineralogy.

(5) Driving forces for the micritization of sediment grains may

include biologieal alteration of pore-water chemistry and

inorganic reduction in free energy of crystal surfaces.

{()} Microboring activity can also be an important factor in the

micritization of carbonate grains. This can involve (a)

formation of open boreholes and later precipitation of

infilling cement, as described by Bathurst. or (b) con-

current infilling with little evidence of open boreholes. In

the latter ease, micritization by microboring is difTicult to

distinguish from mieritization by recrystallization.

Ian G.Macintyre and R. Pamela Reid

Bibliography

Alexancicrssoii.

E.T., 1972.

Miciiti/;Uion

of

carboiiLUc panicles:

process

of

precipitation

and

dissolution

in

modern sliiillow-marinc

sediments. Universitvt Uppsala. Geologi.\ka In.stitut Buiietin.

7:

201

2.^6.

Bathurst. R.G.C.. 1466. Boring algae, mierite envelopes,

and

liiliifica-

tion

of

molkiscan biosparites. Geological.Journal.

5:

15-32,

Folk.

R.L..

f9?9. Practical petrographie ehissifluilion

of

limestones.

American .Associationol Petroleum Geologists Bulletin. 43:

1

-38.

Folk.

R.L..

l'J62. Speetral subdivision

of

limestone types.

In Ham.

W.E. (cd.), Classifieationof Carbonate Rocks. Ameriean Association

of Petroleum Geologists,

pp.

62-84.

Folk, R.L.. 1974. Tlic natural history

of

erystalline caleium carbonate:

cfTect

of

magnesium eontenl

and

salinity.

J<nirnal

of

Sedimeniarv

Petrology. 44:

40 53,

i'ricdman.

G.M..

1985.

The

problem

of

submarine cement

in

classi-

fying reelVoek:

an

experience

in

frii strut ion, Schncidermann.

N. and

Marris. P.M. (eds.), SoeietyofEcontm]iePaleontotogistsandMiticralo-

gisis. pp. f

f7 121.

Gunaiilaka.

A., 1976.

Thallophyte boring

and

micritization within

skeletal sands from Connemara, western Ireland. JournaloJ Sedi-

mentary Petrology.

46: 548 554.

Illing.

L.V., 1954.

Bahamian calcareous saiids. .American .Assoeiation

ol Petroleum

Geologi.Us

Bulletin.

iS: 1 95.

Kobluk,

D.R.. imd

Risk, M..I..

1977.

Micritization

and

earbonate-

Brain binding

by

endolithic algae. .American

A \.soeiation

of

Petro-

leum Geologists Bulletin. 61:

1069 1082.

Land.

L.S., and

Moore.

C.H.. 1980,

l,itbifk-ation, micrilization

and

syndepositiona! diagenesis

of

biolithitcs

on the

Jamaican island

siope.

Journal<ij

Sedimentary Pcirology.

50: 357 370.

Lloyd.

R.M..

1971. Some observations

on

reeent sediment alteration

("micritization")

and the

possible role

of

algae

in

submarine

cementation,

hi

Bricker.

0,P. (ed.)

Carbonate Cements.

The

Johns

Hopkins Press,

pp. 72 79.

Macintyre.

I.G., and

Reid.

R.P..

1995. Crystal alieration

in a

living

ealcarcous aiga {llttlimeday. implications

for

stndies

in

skeletal

diagenesis. Journalof Sedimentary Research. A65:

143 15.3.

Macintyre.

I.G.. and

Reid.

R.P.. 1998.

Reerystalli/ation

in a

living

porcelaneous foraminifera

{.Archaias

angulatis): texturai changes

vviihoul mineraloizie alteration. Journal

oj

Sedimentary Re.seareh.

68:

11

19. ^

Macintyre.

I.G.,

Prufert-Bcbout,

L.. and

Reid, R,P.. 2000.

The

role

of

endolithie cyanobacterium

in the

formation

of

lithitied laminae

in

Bahamian stromatolilcs. Sedimentotogy.

Al:

915-921.

Morse.

J.W..

Ziillig,

J,J.,

Lawrence. D!B.. Millero.

F.J.,

Milne.

P..

Miicei,

A., and

Choppin.

G.R.. 1985.

Chemistry

of

calcium

carbonale-rieh shallow water sedimenls

in the

Bahamas. .Ameriean

.lournai of Science.

285:

147-185.

Patterson.

W.P.. and

Walter,

L.M..

1994. Syndepositional diagenesis

of modern platform carbonates: evidence from isotopic

and

minor

element data. Geology. 22:

127 f30.

Purdy,

E.G., [963.

Reeent calcium carbonate facies

of the

Great

Bahama Bank. Journaloj

Geology.

71:

3.M

355, 472-497.

Purdy,

E.G..

f968. Carbonate diagonesi^:

an

environmental survey.

Geologiea

Romamt.l:

183 228.

Pusey,

W.C. 1964.

Reeent Calcinm Carbonate Sedimentation

in

Northern British Honduras

(Ph.D

Thesis). Houston: Rice

Uni-

versity, 247pp.

Reid.

R.P..

Macintyre,

I.G.. and

Post,

J.E.. 1992.

Micritized skeletal

grains

in

northern Belize lagoon:

a

major source

of

Mg-calcite

mud. Journal of .Sedimentary Petrology. 62: 145-156.

Reid. R.P..

and

Macintyre,

I.G.,

1998. Carbonate reerystallization

in

shallow marine environments:

a

widespread diagenetic proeess

forming micritized grains. Journal

of

Sedinwntarv Research.

68:

928

946.

Reid. R.P..

and

Macintyre.

I.G..

2t)()0. Microboring verses reerystaffi-

zation: further insight into

the

micrili/ation process. Jottrnal

of

.Sedimentary Research.

70: 24 28.

Rude.

P.O.. and

Aller.

R.C..

I99L Fluorine mobility during early

diagenesis

of

earbonate sediment:

an

indieator

of

mineral

transformation. Geochinucaet Cosmoehimiea

.Acta.

55:

249f -251)9.

Walter, L.M..

and

Burton.

E.A.,

1990. Dissolution

of

recent piatform

carbonate sediments

in

marine pore fluids. Ameriean Journal

of

.Science. 290: 601-643.

Walter,

L.M..

Bischof.

S.A.,

Patterson. W.P..

and

Lyons. T.W.,

f993.

Dissolution

and

reerystallization

in

modern shelf carbonates:

evidenee from pore water

and

solid phase chemistry. Philosophical

Transactions

oj

the

Royal Soeiety (Londom.

344:

27-36.

Whinland.

H.D., 1969.

Stability

of

carbonate polymorphs

in

warm,

shallow seawater. Journal

of

Sedimentarv Petroh>i;y.

39:

1579-1587.

Wolf,

K.H., 1965.

"Grain-diminution"

of

algaf colonies

to

mierite.

Journal ol Sedimentary Petrology. 35:

420 427.

MICROBIALLY fNODCED SFDIMFNTARY STRLiCTURFS

MICROBIALLY rNDUCED SEDIMENTARY

STRUCTURES

Coastal sediniLMitary systems ol' moderate climate zones are

governed tiot only by physical dynamics like erosive tidal

flushing or reworking by wave action, but also by biotic factors

like sediment stabilizing or accumulating by epibenthic

bacterial commiinilies. The shallow-tmirinc environments are

coloni/ed by benthic microorganisms, amongst those photo-

iuitotroph cyanobacteria are an abundant gn)up (ecology:

Whitton and Potts. 20()()). With the aid of their adhesive and

slimy "extracellular polymeric substances"" (EPS. see for

introduction Decho. I99U), epibenthic species attach to

mineral grains, and they can even form thick, tissue-like,

organic layers covering extensive areas of the sedimentary

surface. Such bacterial "carpels'" are termed "mierobial mats""

(definition of term see Krumbein. 1983: overview also in

Gerdes and Krumbein. 1987; Cohen and Rosenberg, 1989; Stal

and Caumette, 1994; Stolz. 2(K)0).

Colonizing at the interf^ice between sediment and water,

cyanobacteria are able to react to sediment-affect ing physical

agents in difTerent ways.

Responsive behavior of epibenthic cyanobacteria to

physical sedimentary dynamics

[during periods of no or low rates of sediment deposition, thick

mierobial mat layers develop. By growth, they smoothen out

or level the original tidal surface morphology, and form flat

bedding surfaces (compare Noffke and Krumbein, 1999). In

close up on vertical sections through thick mat layers, the

growing biomass drags upward mineral grains from the

sedimentary substrate. The grains are separated from each

other, atid become oriented with their long-axes perpendicu-

larly to the loadini! pressure (mierobial grain separation:

Noffke £'/«/.. 1997).'

Slow moving, suspension-rich bottom currents induce a

vertical orientation of cyanobacterial filaments that trigger

fall-out of sediment by "baffling, trapping, and binding"*

(Black, 193.1). Over time, the sediment agglutinating mierobial

community grows upward (Gerdes cl al., 1991). In vertical

section, this produces laminated intrasedinientary patterns.

In depositional areas of higher hydrodynamic energies, only

thin mierobial mats ean grow. They cover surface structures,

like ripple marks, without altering the original shape of the

relief.

Buried depositional surfaces are "imprinted"" by the

thin, former mat layers (Gerdes ei al.. 2000. and references

therein).

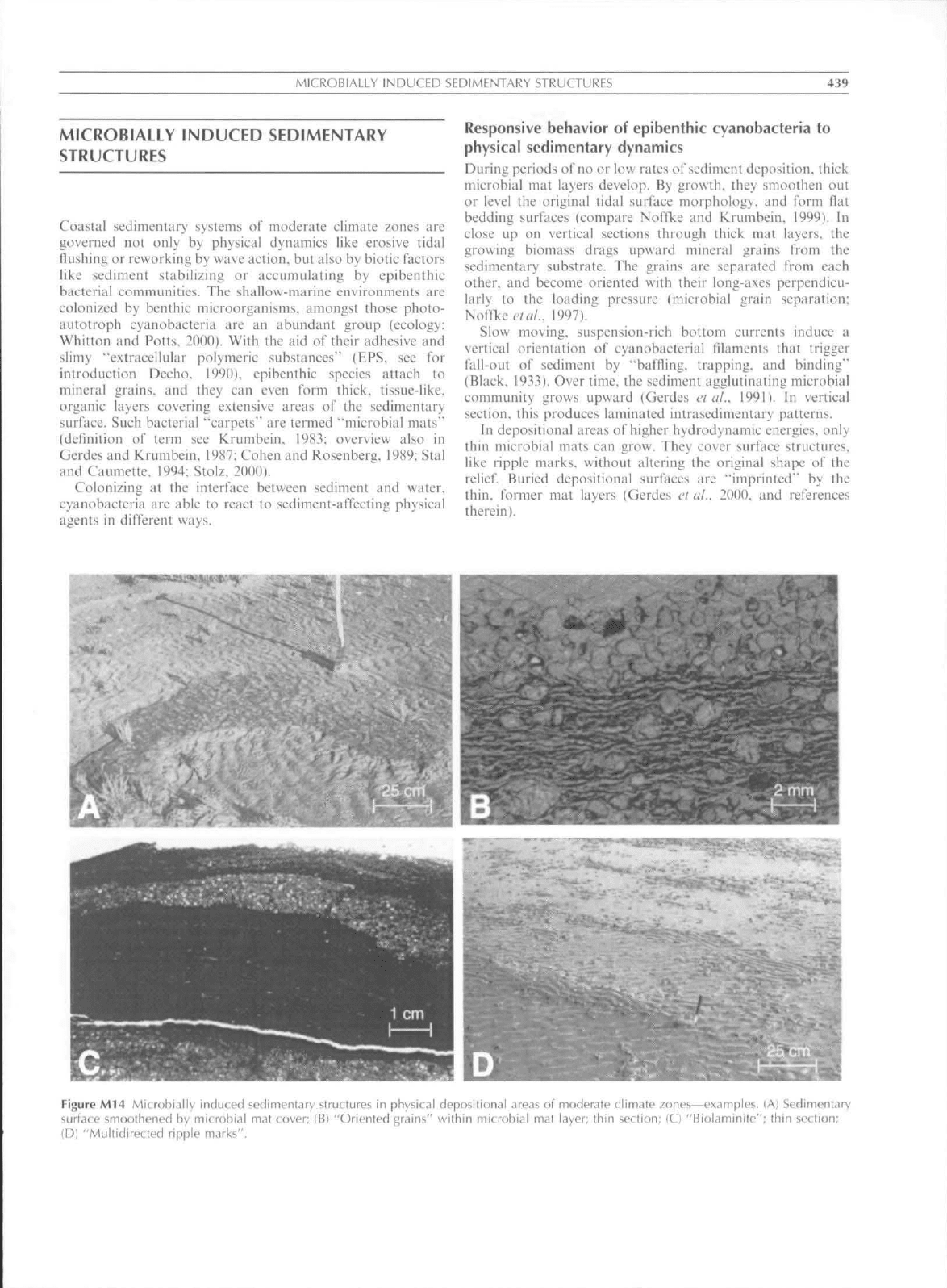

Figure M14 Microbi.illy induced sedimentary slruclures in physical depositional areas of moderate tlimate zones—examples. (Al Sedimentary

smoothened by mierobial mat cover; (B) "Oriented grains" within mierobial mat layer; thin section; (C) "Blol.iminiie"; thin section;

"Miiltidiretted rippie marks".

440 MICROBIALLY INDUCED SEDIMENTARY STRUCTURFS

Only when subjected to strong bottom currents, mat-secured

sedimentary surfaces are eroded, because the dense and

coherent mierobial mats seal efTectivety their sitbstrate and

increase resistance against erosion. Additionally, cyanobacterial

layers prohibit exchange of gas between sediment and water.

These effects are known as "biostabilization"" (Paterson. 1994;

Krumbein eUtl.. 1994; Paterson. 1997; Noffke

ctaf.

2001).

Microbially induced sedimentary structures

The responsive behavior of the mat-constructing micro-

epibenthos generates a great variety of characteristic sedi-

mentary structures. The structures differ significantly IVom

biogene stromatolites we are familiar frotn chetnical litho-

logies, and mineral precipitation plays no role in their

formation.

Flat bedding planes originated by immense mat growth are

termed -'leveled surfaces""^(Nofl"ke. 2000; NoflTce ctai.. 2001).

Figure M I4(A). In the fossil record, they can be recognized as

"wrinkle structures" (Hagadorn and Bottjer, 1997), where they

document pauses in sedimentation (Noffke, in press). Char-

acteristically, thin-sections ihrough leveled surfaces reveal

"tnat layer-bound oriented grains'", that is mineral particles

floating indepetidently from each other in the organic tnatrix

like a chain of pearls. Figure M14(B). They document former

mierobial grain separation, and pressure-related orientation

(Noffke

('/(//..

1997).

Laminated intrasedimentary pattern caused by baffling.

trapping, and binding arc well-known as "biolaminites"". or,

after consolidation, as "planar stromatolites"" (discussion of

tenns by Krumbein. 1983). Figure M14(C).

Typical surface morphologies that are shaped by biostabil-

ization interfering with erosion are "erosional remnants and

pockets"" (NoflTie. 1999; fossil example; MacKeti/ie. 1968). or

"multidirected ripple marks'" (Noffke, 1998; fossil counter-

parts:

Pllueger, 1999). Figure M14(D). Internal features are

"fenestrae fabrics" (Gerdes etal.. 2000). "Sinoidal structures"",

visible in vertical sections through the sediment, itnprint

former ripple mark valleys (Gerdes etal.. 2000; Noffke etat..

2001;

fossil example: Nofi^ke. 2000).

Because the structures are formed syndepositionally by

biotic-physical interference, they were grouped as an own

category "tnicrobtatly induced sedimentary structures"" into

the Classiflcation of Primary Sedimentary Structures (Noffke

etal.. 2001).

Nora Noffke

Bibliography

Black.

M., 193.1 The

afgal scdimcrtts

of

Andros Islands. Bahamas.

Royal Society oj London Phiiosophieal

Transaetion.\.

Scries.

B, 222:

165-192.

Cohen.

Y.. and

Rosenberg,

E.. 1989.

Microbiai Mats. Physiological

Ecology

oj

Benthic Microhial Communities. Wasfiingtoii,

DC:

American Society

ol'

Microbiologists. 494pp.

Decho.

A.W.. 1990.

Microbiai exopolymer secretions

in

ocean

environments: their role(s)

in

food webs atid tnarine processes.

Oceanographic Marine Biology Annual Review.

28:

7."^-1

Sy.

Gerdes.

G..

atid Krumbein,

W.E., 1987.

Biolaminated Deposits,

Springer. 1X3

p.

Gerdes,

G.,

Krumbein,

W.E.. and

Rdncck.

H.F.. 1991.

Biolaniina-

tions eeofogical versus depositional dynamies.

In

Einsele,

G..

Ricken.

W., ;ind

Seilachcr.

A.

(eds.).

Cycles

and

Events

in Stratigr(t-

phy. Springer-Verlag,

pp. 592 607.

Gerdes.

G..

Klenke, Tli.,

and

Noffke. N.. 2000. Microbiai signatures

in

peritidal silicitlastic sediments;

a

eataloguc. Sedimentology.

47:

279-308.

Hagadorn, J.W..

and

Boltjer. D.. 1997. Wrinkle structures: microbially

mediated sedimentary structures common

in

subtidal siliciclastic

settings

at the

Proterozoic Phanerozoic trtinsilion. Geoloi'v.

25:

1047-1050.

Krumbein.

W.E,. 1983.

Stromatolites—The challenge

of a

term

in

space

and

lime. Precambrian Research. 20:

493-531.

Krumbein. W.L., Paicrson. D.M..

and

Sial.

L.J..

1994. Bio.stahilization

of Sediments.

BIS,

University

of

Oldenburg, 526pp.

MacKen^^ic. D.B.. 1968. Sedimentary features

of

.Alameda A\enue

cut.

Denver. Colorado. Mintntain Geologist.

5: 3

-13.

Non"ke.

N., 1998.

Multidirected ripple marks rising from biological

and sedimentological processes

in

modern lower supratidiil

deposits (Mellum Island, southern North

Sea).

Geology.

26:

879

882.

Nol'fke.

N., 1999.

Erosional remnants

and

pockets evolving from

biotic-physieal interaetions

in a

Recent lower supratidal environ-

ment. Sedimentary Geology. 123:

175 181.

Noffke.

N..

2000. Extensive microbiai mats atid their influences

on the

erosional

and

depositionai dynamics

of a

siliciclaslic cold water

environment (Lower Arenigian. Motitagne Noire. France). Sedi-

tnenlary Geology. 136: 207-215.

Nt^ffkc.

N..

2003.

Epibenlhic cyanobacterial conitnunities

in the

conte.xt

of

sedimentary processes within siliciclastic depositional

systems (present

and

past).

In

Patterson.

D..

Zavarzin,

G., and

Krumbein.

W.E.

(eds.). Biojilms Through Spaee

and

Time. Kluwer

Academic Publishers

(in

press).

Noffke,

N.. and

Krumbein.

W.E.. 1999. A

quantitative approaeh

to

sedimentary surface structures contoured

by the

interplay

of

tnicrobial colonization

and

physical dynamies. Sedimentology.

46:

4!7

426.

NofllL-.

N..

Gerdes.

G..

Klenke.

Th.. and

Krumbein,

W.E.. 1997. A

microscopic sedimentary sueeession indicating

the

presetice

of

microbiai mats

in

silieielastic tidal fiats. Sedimentary Geology.

110:

16.

Noffke,

N.,

Gerdes,

G.,

Klenke.

Th.. and

Krumbein.

W.E.. 2001.

Mierobially indueed sedimentary strnciurcs—a

new

category

within

the

classification

of

primary sedimentary struetures. .(our-

iuili>l

.Sedimentary Research. 71: 649-656.

Paterson.

D.M.. 1994.

Microbiological mediation

of

sediment struc-

ture

and

behaviour,

hi

Slal.

L.J.. and

Caumette.

P.

(eds.). Micro-

hial Mats, Springer-Verlag.

pp.

97-109.

Paterson.

D.M.. 1997.

Biological tiiedialion

of

sediment erodiability:

ecological

and

physical dynamics.

In

Biirt.

N.,

Parker,

R.. and

Watts.

J.

(eds.). Cohesive Sediments. Wiley,

pp.

215-229.

Peuijohn.

E.J.. and

Potter,

P.E,, 1964.

Atlas

and

Glossary

of

Primary

Sedimentary Structures. Springer-Veriag.

Pfiueger.

F.,

1999. Maturound struetures

and

redox facies. Palaios.

14:

25

.19.

Stal,

L.J.. and

Caumette.

P.. 1994.

Microbiaf mats. Strueture,

development

and

environmental significance. NATO

AS/

Series

Ecological Seiences,

35,

Berlin, Heidelberg,

New

York: Springer

Verlag. 462pp.

Slol/:,

.I.F..

2000. Structure

of

mierobial mats

and

biofilms.

In

Riding.

R.. and

Awramik,

S.M.

(eds.). Microhial Sediments.

Springer Verlag.

pp. I 8.

Whitton.^B.A..

and

Potts.

M..

2000.

The

Ecology

of

Cyanohaeteria.

Their Diversity

in

Time

and

Spaee. Kltiwer Academie Publishers.

669p.

Cross-references

Algal

and

Baeterial Carbonate Sediments

Bacteria

in

Seditnents

Bedding

and

IiUeinal Structures

Biogenie Sedimentary Slruelures

Surface Forms

MILANKOVITCH CYCLES

441

MILANKOVITCH CYCLES

Variations

in the

Farth's orbital parameters eause quasi-

periodic.

10 -lO''

year scale changes

to

occur

in ihe

incoming

solar radiation,

or

insolation. These insolation changes

are

commonly known

as

Milattkoviieh cvcles. after

the

Yugoslav

malhenialician

who

first described

the

cycles (Milankovitch,

IWl).

Milankovitch cycles have been linked

to

large-scale

climate cycles

and, in

turn,

to

climate-mediated sedimentary

cycles (e.g.. Berger tV///..

1^84;

Einsele (7<//.. 1991; Shackleton

ctai. 1999).

Earth's orbital parameters

The Earth's rotating axis

of

figure

is

tilted with respect

to the

Sun. Moon

and the

other planets. Consequently,

the

axis

precesses mainly

in

response

to the

luni-solar gravitational

attraction

on the

Earth's equatorial bulge,

at a

rate governed

primarily

by the

Earth's shape, rotation rate,

and

Earth Moon

distance.

In

addition,

the

axial precession experiences gravita-

liona! perturbations from

the

motions

of the

other planets

acting

on the

Earth's orbit (e.g.. Laskar

19H8.

Berger

and

Loulre. 1990). Some perturbations modulate

the

distance

and

timing

of the

Earth's closest annual approach

to the Sun

(orbital eccentricity

and

longitude

of

perihelion), which

together affect

the

year-to-year duration

and

intensity

of

seasonal insolation,

or

clit)iaticprecession. alsoealled preeession

parameter, precession index,

or

precession eccentricity

syn-

drome. Variations

in the

Earth's orbitaleccetitrieity. generated

by interactions among these perturbations, give rise

to

small

changes

in the

Earth's total annual insolation. Other

perturbations cause

the

Earth's orbital plane

to tip and

precess

(orbital inclination

and

longitude

of the

ascending node),

thereby modulating

the

Earth's axial tilt angle,

or

ohliquity.

relative

to the Sun. and

consequently,

the

Earth's laiiludinal

distribution

of

insolation.

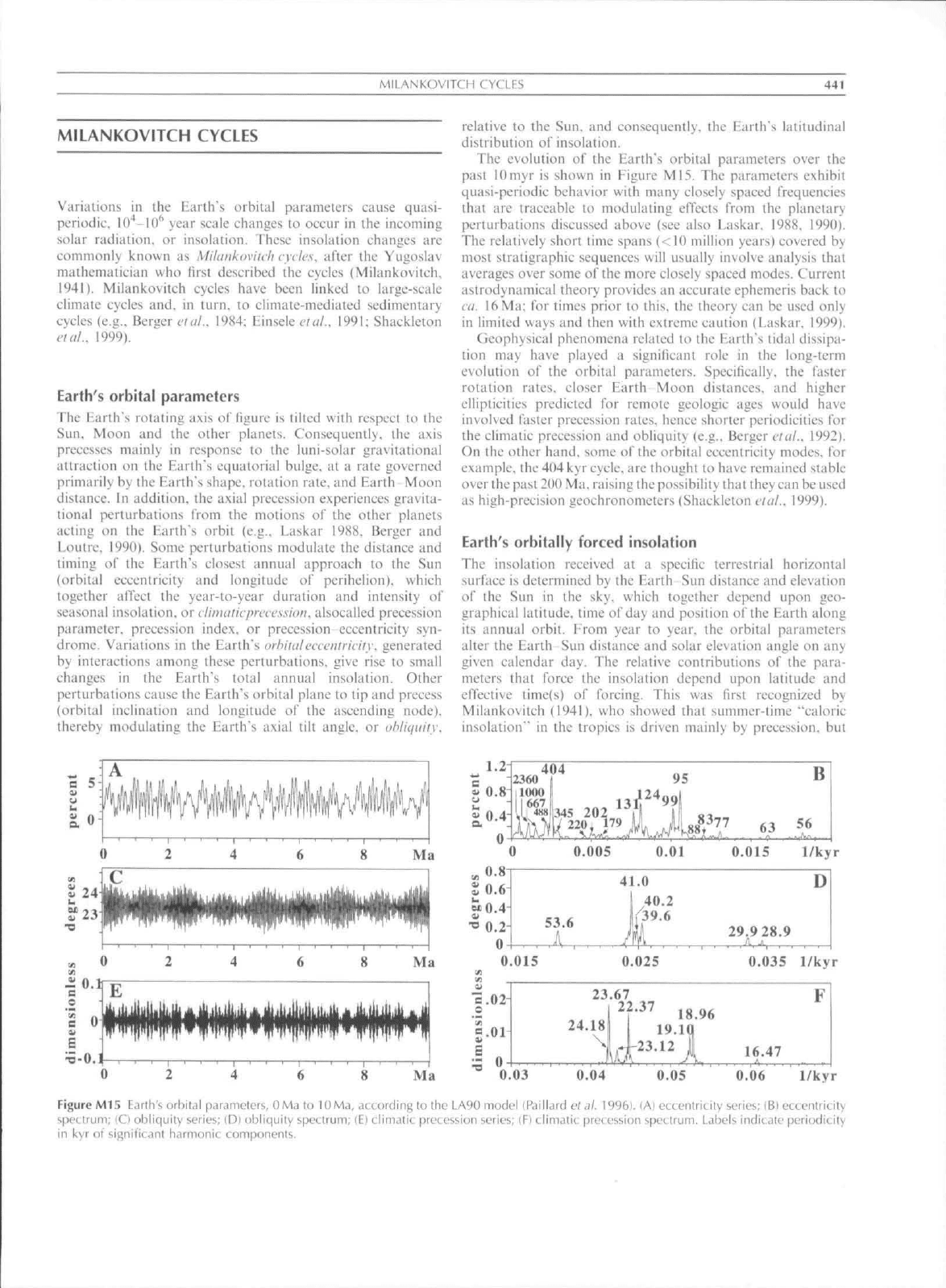

The evolution

of the

Earth's orbital parameters over

the

past lOmyr

is

shown

in

Figure

MI5. The

parameters exhibit

quasi-periodic behavior with many closely spaced frequencies

that

are

traceable

to

modulating effects from

the

planetary

perturbations discussed above

(see

also Laskar,

1988.

1990).

The relatively short time spans

(<10

million years) covered

by

most stratigraphic seqtienccs will usually involve analysis that

averages over some

of

the more closely spaced modes. Current

astrodynamical theory provides

an

accurate ephemeris back

to

cu.

16 Ma;

for

times prior

to

this,

the

theory

can be

used only

in limited ways

and

then with extreme caution (Laskar, 1999).

Geophysical phenomena related

to the

Earth's tidal dissipa-

tion

may

have played

a

significant role

in the

long-term

evolution

of the

orbital parameters. Specifically,

the

faster

rotation rates, closer Earth Moon distances,

and

higher

ellipticities predicted

for

remote geologic ages would have

involved faster preeession rates, hence shorter periodicities

for

the climatit: precession

and

obliquity (e.g., Berger ctai.. 1992).

On

the

other hand, some

of

the orbital eccentricity modes,

for

example, the 404 kyr cycle,

are

thought

to

have remained stable

over the past 200 Ma. raising the possibility that they can be used

as high-precision geochronometers (Shackleton etal.. 1999).

Earth's orbitally forced insolation

The insolation received

at a

specific terrestrial horizontal

surface

is

determined

by the

Earth

Sun

distance

and

elevation

of

the Sun in the sky.

which together depend upon

geo-

graphical latitude, time

of

day

and

position

of

the Earth along

its annual orbit. From year

to

year,

the

orbital parameters

alter

the

Earth

Sun

distanee

and

solar elevation angle

on any

given calendar

day. The

relative eontributions

of the

para-

meters that force

the

insolation depend upon latitude

and

effective time(s)

of

forcing. This

was

first recognized

by

Milankovitch (1941).

who

showed that summer-time "caloric

insolation"

in the

tropics

is

driven tnainly

by

preeession.

but

6

8 Ma

0.015

0.025

l/kyr

0.035

l/kyr

02-

01

0

24.

23

IS

\

.67

22

•4

.37

23

19

12

IS

10

1

.96

16

,47

F

0.03 0.04

0.05 0.06 l/kyr

Figure

Ml5

Earth's orbital |),ir,jn)elt'rs, ()M.3

to

10Ma, attofdinji

to the

LA90 model (Paillard

cl JI.

19961.

(A)

eccenlricity stTios;

(Bl

eccentricity

spci irum;

(Ci

obliquity series:

ID)

oblic]uity spectrum;

lEl

climatic prt'ct'ssion series;

(F)

tlimatit" precession spectrum. Labels inciicate periodicity

in

kyr ot

significant harmonic components.

442

MILANKOVITCH CYCLES

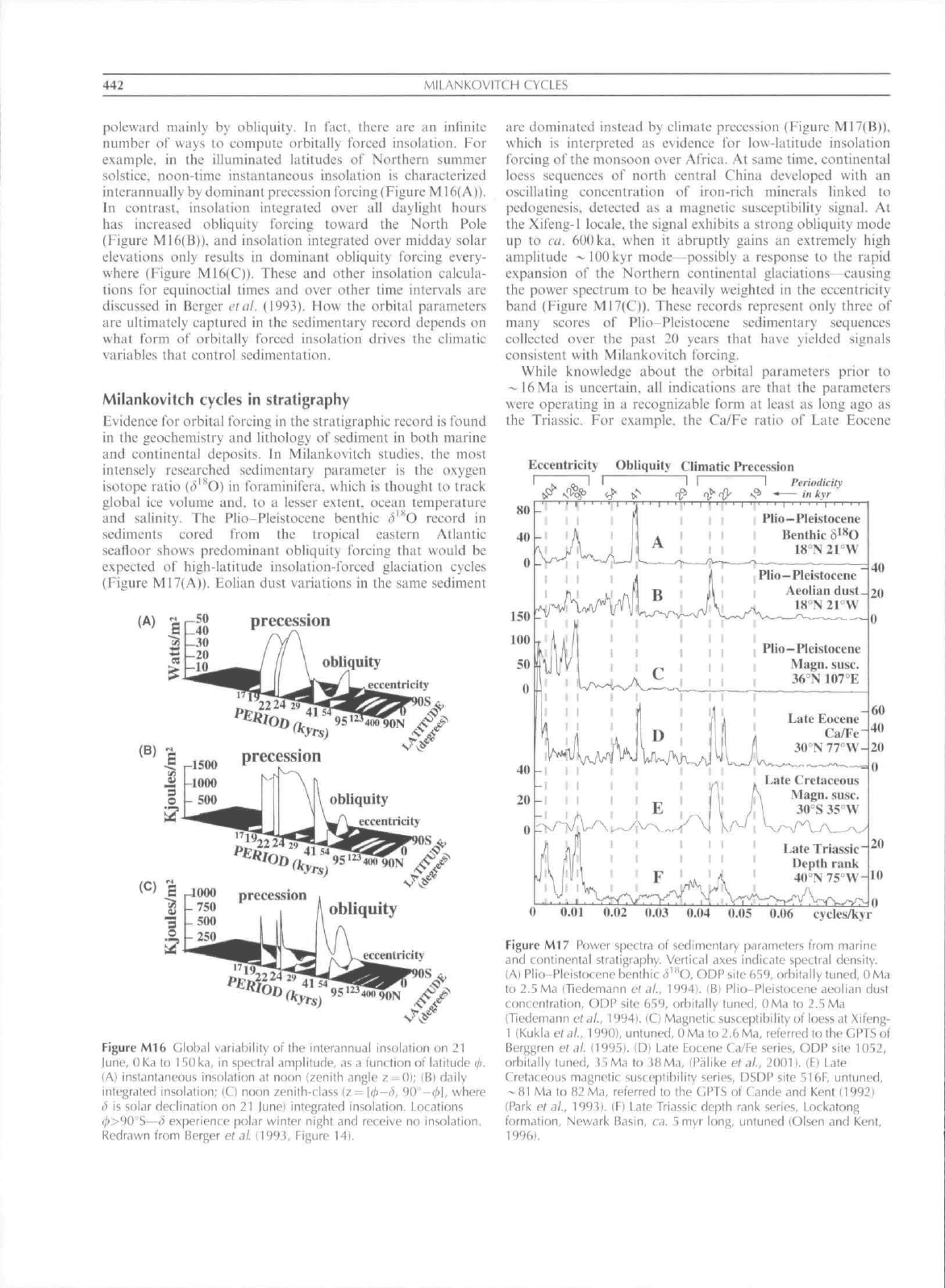

poleward mainly by obliquity. In fact, there are an infinite

number of ways to compute orbitally forced insolation. For

example, in the illuminated latitudes of Northern summer

solstice, noon-time instantaneous insolation is characterized

intcrannually by dominant precession forcing (Figure MI6(A)).

In contrast, insolation integrated over all daylight hours

has increased obliquity forcing toward the North Pole

(Figure M16(B)), and insolation Integrated over rnidday solar

elevations only results in dominant obliquity forcing every-

where (Figure M16(C)). These and other insolation calcula-

tions for equinoctial times and over other time intervals are

discussed in Berger eral, (1993). How the orbital parameters

are ultimately captured in the sedimentary record depends on

what form of orbitatly forced insolation drives the climatic

variables that control sedimentation.

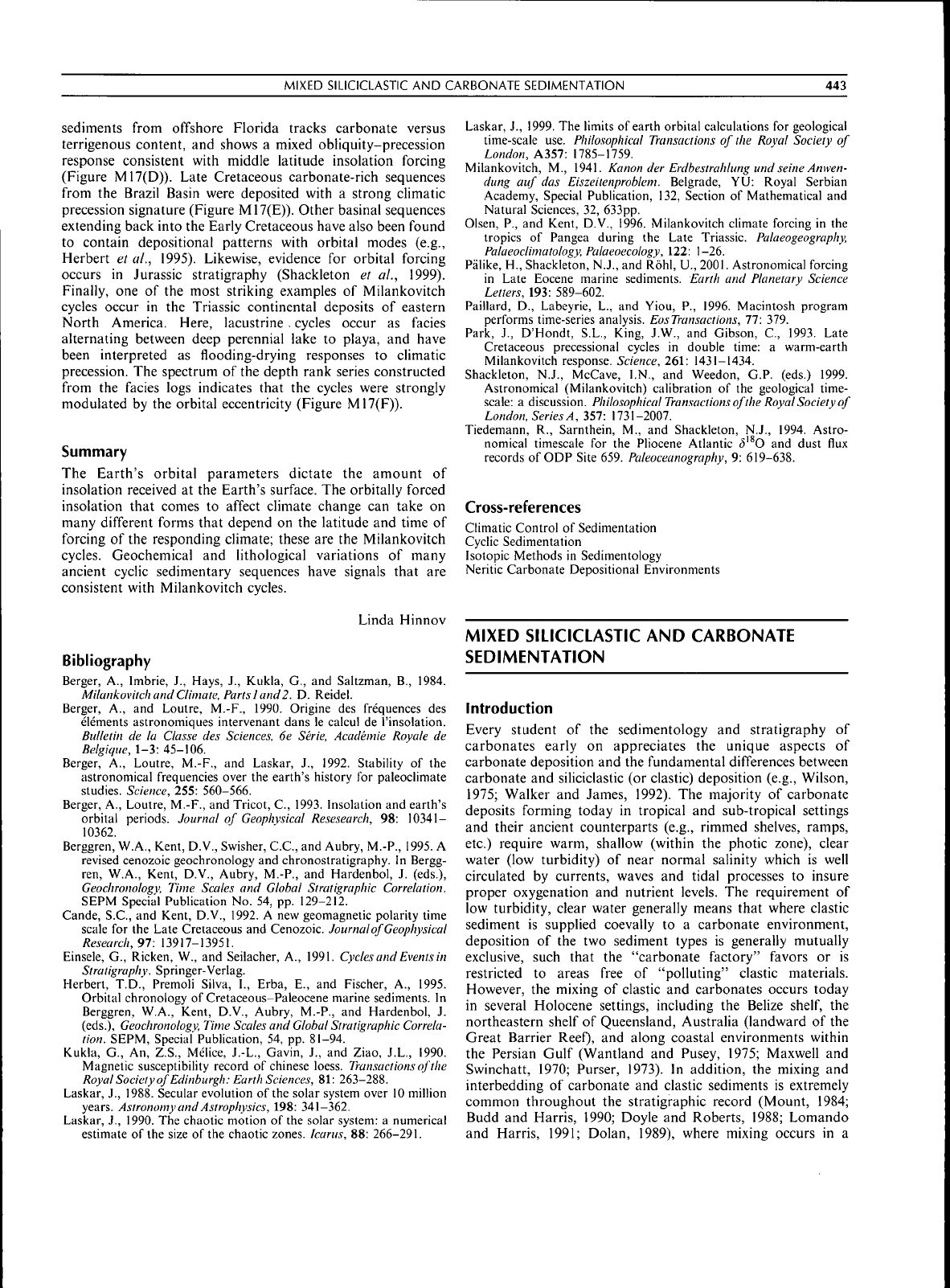

Milankovitch cycles in stratigraphy

Evidence for orbital forcing in the stratigraphic record is found

in the geochemistry and lithology of sediment in both marine

and continental deposits, in Milankovitch studies, the most

intensely researched sedimentary parameter is Ihe oxygen

isotope ratio (i:>"*O) in foraminifera. which is thought to track

global ice volume and. to a lesser extent, ocean temperature

and salinity. The Plio-Pleistocene benthic ()"^O record in

sediments cored from the tropical eastern Atlantic

seafloor shows predominant obliquity forcing that would be

expected of high-latitude insolation-forced glaeiation eyeles

(Fiiiure MI7(A)). Eolian dust variations in the satne sediment

(A) ^r^o

precession

S |-4000 precessiou

750 1\

obliquity

Figure M16 Global varitibility of the interannual insolation on 21

[line,

(1

Ka to

1

50

ka,

in spectral amplitude, as a function of latitude i/i.

(A) instantaneous insolation at noon (zenith angle z =

()l;

(Bl d.iily

integrated insolation; (Cl noon zenith-class (z ~

\4)-i>.

90' -(p], where

(5 is 5olar declintition on 2J |une) integrated insolation. Locations

0>9O'

S—(i experience pular winter night and receive no insolation.

Redrawn from Berger ef

JI.

(199.i, Figure 14).

are dominated instead by climate precession (Figure MI7(B)).

which is interpreted as evidence for low-latttude insolation

forcing of the monsoon over Africa. At same time, continental

loess sequences of north central China developed with an

oscillating concentration of iron-rich minerals linked to

pedogenesis, detected as a tnagnetic susceptibility signal. At

the Xifeng-1 locale, the signal exhibits a strong obliquity mode

up to ca. 600 ka, when it abruptly gains an extremely high

amplitude -- 100 kyr mode—possibly a response to the rapid

expansion of the Northern continental glaciations causing

the power spectrum to be heavily weighted in the eccentricity

band (Figure MI7(C)). These records represent only three of

many scores of Plio-Pleistocene sedimentary sequences

colleeted over the past 20 years that have yielded signals

consistent with Milankovitch forcing.

While knowledge about the orbital parameters prior to

-l6Ma is uncertain, all indications are that the parameters

were operating in a recognizable form at least as long ago as

the Triassic. For example, the Ca/Fe ratio of Late Eocene

Eccentricity Obliquity Climatic Precession

1 Periodicity

in kvr

, Plio-Pleistocene

I Benthic

6'**0

! 18"N

Plio-Pleistocene

I Aeolian dust

Pho-Pleistocene

I Magn. susc.

Late Cretaceous

I (

Magn. .sust.

JO

0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 cvcles/kvr

Figure MM Power spectra of sedimentary [i,ir<imeters frcim marine

and continental stratigraphy. Vertical axes indicate spectral density.

(Al Plio-Plcistt)cene benthic d'"O, ODP site 659, orbitally tuned, 0 Ma

to 2.5 Ma (Tiedemann et ai., 1994|. IB) Piio-Pleistocene aeolian dust

concentration, ODP site 659, orbitally tuned, OMa to 2.5 Ma

(Tiedemann cl

sL,

19941.

IC) Magnetic susceptibility of loess at Xifeng-

1 (Kuklaef.3/., 1990), untuned, OMa to 2.6Ma, referred lo the GPTS of

Berggren et dl,

119951.

(D) Late Eocene Ca/Fe series. ODP site 1052,

orbitally tuned, 35 Ma to 38

Ma,

(Palike el ni, 2001). (E) Late

Cretaceous magnetic susceptibility series, DSDP site 516F, untuned,

-81 Ma lo82Ma, referred to the GPTS of Cande and Kent (19921

(Park et ai,

19931.

(Fl Late Triassic depth rank series, Lockatong

formation,

Newark Basin, ca.

.5

myr

long,

untuned (Olsen and Kent,

19961.

MIXED SILICICLASTIC AND CARBONATE SEDIMENTATION 443

sediments from offshore Florida tracks carbonate versus

terrigenous content, and shiows a mixed obliquity-precession

response consistent witti middle latitude insolation forcing

(Figure M17(D)). Late Cretaceous carbonate-rich sequences

from the Brazil Basin were deposited with a strong climatic

precession signature (Figure Mt7(E)). Other basinat sequences

extending back into the Early Cretaceous have also been found

to contain depositional patterns with orbital modes (e.g.,

Herbert et al., 1995). Likewise, evidence for orbital forcing

occurs in Jurassic stratigraphy (Shackteton et al., 1999).

Finally, one of the most striking examples of Milankovitch

cycles occur in the Triassic continental deposits of eastern

North America. t4ere, lacustrine, cycles occur as facies

alternating between deep perennial lake to ptaya, and have

been interpreted as flooding-drying responses to climatic

precession. The spectrum of the depth rank series constructed

from the facies logs indicates that the cycles were strongly

modulated by the orbital eccentricity (Figure Mt7(F)).

Summary

The Earth's orbital parameters dictate the amount of

insolation received at the Earth's surface. The orbitally forced

insolation that comes to affect climate change can take on

many different forms that depend on the latitude and time of

forcing of the responding climate; these are the Milankovitch

cycles. Geochemical and lithotogical variations of many

ancient cyclic sedimentary sequences have signals that are

consistent with Milankovitch cycles.

Linda Hinnov

Bibliography

Berger, A., tmbrie, J., Hays, J., Kukla, G., and Saltzman, B., 1984.

Milankovitch and

Climate,

Parts

land

2.

D. Reidel.

Berger, A., and Loulre, M.-F., 1990. Origine des frequences des

elements astronomiques intervenant dans le caleul de j'insolation.

Bulletin de la Classe des Seienees, 6e Serie, Aeademie Royate de

Belgique, 1-3: 45-106.

Berger, A., Loutre, M.-F., and Laskar, J., 1992. Stability of the

astronomical frequencies over the earth's history for paleoclimate

studies. Seienee, 255: 560-566.

Berger, A., Loutre, M.-F., and Tricot, C, 1993. Insolation and earth's

orbital periods. Journal of Geophysieal Reseseareh, 98:

10341-

10362.

Berggren, W.A., Kent, D.V., Swisher, C.C, and Aubry, M.-P., 1995. A

revised cenozoic geochronology and chronostratigraphy. In Bergg-

ren, W.A., Kent, D.V., Aubry, M.-P., and Hardenbol, J. (eds.),

Geoehronology, Time Seales and Global Stratigraphie Correlation,

SEPM Special Publication No. 54, pp. 129-212.

Cande, S.C, and Kent, D.V., 1992. A new geomagnetic polarity time

scale for the Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic. Journalof Geophysieal

Researeh, 97: 13917-13951.

Einsele, G., Ricken, W., and Seilacher, A., 1991.

Cyeles

and Events in

Stratigraphy, Springer-Verlag.

Herbert, T.D., Premoli Silva, t., Erba, E., and Fischer, A., 1995.

Orbital chronology of Cretaceous-Paleocene marine sediments. In

Berggren, W.A., Kent, D.V., Aubry, M.-P., and Hardenbol, J.

(eds.),

Geochronology,

Time Seales and Global Stratigraphie Correla-

tion.

SEPM, Special Publication, 54, pp. 81-94.

Kukla, G., An, Z.S., Meliee, J.-L., Gavin, J., and Ziao, J.L., 1990.

Magnetic susceptibility record of Chinese loess.

Transactions

of the

Royal Soeiety of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 81: 263-288.

Laskar, J., 1988. Secular evolution of the solar system over 10 million

years.

Astrotmtny and Astrophysics, 198: 341-362.

Laskar, J., 1990. The chaotic motion of the solar system: a numerical

estimate of the size of the chaotic zones. Iearus, 88:

266-291.

Laskar, J., 1999. The limits of earth orbital calculations for geological

time-scale use. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of

London, A357: 1785-1759.

Milankovitch, M., 1941. Kanon der Erdbestrahlung und seine Anwen-

dung auf das Eiszeitenproblem. Belgrade, YU: Royal Serbian

Academy, Special Publication, 132, Section of Mathematical and

Natural Sciences, 32, 633pp.

Olsen, P., and Kent, D.V., 1996. Milankovitch climate forcing in the

tropics of Pangea during the Late Triassic. Palaeogeography,

Palaeoelimatology, Palaeoeeology, 122: 1-26.

Palike, H., Shackleton, N.J., and Rdhl, U., 2001. Astronomical forcing

in Late Eocene marine sediments. Earth and Planetary Seienee

Letters, 193: 589-602.

Paillard, D., Labeyrie, L., and Yiou, P., 1996. Macintosh program

performs time-series analysis. EosTransaetions, 11: 379.

Park, J., D'Hondt, S.L., King, J.W., and Gibson, C, 1993. Late

Cretaceous precessional cycles in double time: a warm-earth

Milankovitch response. Seienee, 261: 1431-1434.

Shackleton, N.J., McCave, I.N., and Weedon, G.P. (eds.) 1999.

Astronomical (Milankovitch) calibration of the geological time-

scale: a discussion. Phiiosophieal

Transactions

of the Royal Society of

Londotj, Series A, 357: 1731-2007.

Tiedemann, R., Sarnthein, M., and Shackleton, N.J., 1994. Astro-

nomical timescale for the Pliocene Atlantic ^'^0 and dust flux

records of ODP Site 659. Paleoeeanography, 9: 619-638.

Cross-references

Climatic Control of Sedimentation

Cyclic Sedimentation

Isotopic Methods in Sedimentology

Neritie Carbonate Depositional Environments

MIXED SILICICLASTIC AND CARBONATE

SEDIMENTATION

Introduction

Every student of the sedimentology and stratigraphy of

carbonates early on appreciates the unique aspects of

carbonate deposition and the fundamental differences between

carbonate and siliciclastic (or clastic) deposition (e.g., Wilson,

1975;

Watker and James, 1992). The majority of carbonate

deposits forming today in tropical and sub-tropical settings

and their ancient counterparts (e.g., rimmed shelves, ramps,

etc.) require warm, shallow (within the photic zone), clear

water (low turbidity) of near normal salinity which is well

circulated by currents, waves and tidal processes to insure

proper oxygenation and nutrient levels. The requirement of

iow turbidity, clear water generally means that where clastic

sediment is supplied coevally to a carbonate environment,

deposition of the two sediment types is generally mutually

exclusive, such that the "carbonate factory" favors or is

restricted to areas free of "polluting" ciastic materials.

However, the mixing of clastic and carbonates occurs today

in several Holocene settings, including the Belize

shelf,

the

northeastern shelf of Queensland, Australia (landward of the

Great Barrier Reef), and along coastal environments within

the Persian Gulf (Wantland and Pusey, 1975; Maxwell and

Swinchatt, 1970; Purser, 1973). tn addition, the mixing and

interbedding of carbonate and clastic sediments is extremely

common throughout the stratigraphic record (Mount, 1984;

Budd and Harris, 1990; Doyle and Roberts, 1988; Lomando

and Harris, 1991; Dolan, 1989), where mixing occurs in a

444 MIXED SILICICLASTIC AND CARBONATE SEDIMENTATION

variety of environments: coastat and inner

shelf;

middle and

outer shelf (reef); slope to basin environments. Mixed deposits

occur in temperate as well as tropical shelf environments.

Late Paleozoic mixed clastic-carbonate successions have

probably received the most study of all mixed deposits. For

example Carboniferous "cyclothems" of the Midcontinent and

southwestern USA and Europe (e.g., Weller, 1930; Duff etal.,

1967;

Wilson, 1967; Rankey, 1999) provide the underpinnings

of models for cyclic stratigraphy at all scales. From these and

additional studies of mixed clastic-carbonate strata of the

Permian Basin in the New Mexico and Texas, the concept of

"cyclic and reciprocal sedimentation" (Van Siclen, t958;

Wilson, 1967; Silver and Todd, 1969; Meissner, t972) was

introduced to explain the origin of mixed clastic-carbonate

shelf-to-basin cyclic deposits. This critical concept has evolved

to provide the foundation upon which present-day "sequence

stratigraphy" is predicated (e.g., Sarg, 1988). From an

economic viewpoint, mixed deposits are significant reservoirs

of oil and gas (e.g., the Permian Basin, USA), and studies of

the high-resolution stratigraphic architecture of mixed clastic-

carbonate sequences has lead to the discipline of reservoir

characterization (e.g., Kerans and Tinker, 1997).

An insightfut approach to the problem of mixed deposits

has been set forth by Budd and Harris (1990) who recognize

basically two types of mixed deposition: (1) mixtures due to

spatial variability, where mixing occurs principally by lateral

facies mixing of coeval sedimentary environments (see also

Mount, 1984); and (2) mixtures due to temporat evolution in

sedimentation, induced by sea-level changes and/or variations

in sediment supply, causing a vertical variation in the

stratigraphic succession. Mixing can occur through a wide

range of scales, from millimeters to kilometers, respond to a

wide range of processes, and can be influenced by all orders of

eyclicity. Trends of mixing can vary along both depositional

strike and dip, ranging from coastal environments to deep

basinal settings.

Important factors that influence mixing include: (i) climate:

humid (fiuvial-deltaic clastic input onto a carbonate

shelf;

e.g.,

the Belize shelf) versus arid (eolian influx; e.g., the Persian

Gulf);

(ii) sediment supply of clastic material and source

terrain (proximal clastic marine shelf with a linear source

versus distal tectonically active, uplifted source terrain with a

fluvial, point-sourced input); (iii) transport mode (episodic

storm mixing versus lowstand-induced sediment by-pass of a

carbonate shelf); (iv) shelf width and paleobathymetry

(carbonate ramp, distally-steepened carbonate ramp, reefal

rimmed high-relief platform, etc.) (v) oceanographic factors

such as prevailing wind- and storm-driven currents, tidal

range, etc.; (vi) relative changes in sea-level which will act to

either trap clastic sediments updip on the shelf during relative

highstands or promote clastic influx onto and across a

carbonate shelf during relative lowstands (Van Siclen, 1958).

The rates and magnitudes and of such relative sea-level

changes will determine the amount and style of mixing, such

that mixed clastic-carbonate cycles and sequences will vary

markedly from "ice-house" periods in geologic history to

"greenhouse" periods.

Styles of clastic and carbonate mixing

Depositional mixing and stratigraphic partitioning occurs

at all scales and to all degrees. For instance, such mixing

may occur: (t) within a single bed whereby minor amounts of

clastic material are dispersed within a carbonate bed with

a low degree of "lithologic separation" (e.g., Cambro-

Ordovician peritidal facies of North America, Read and

Goldhammer, 1988; Goldhammer el al., 1993); (2a) within a

single heterolithic bed ("ribbon rocks") whereby carbonate

material (ooids, peloids, etc.) comprises coarser-grained

planar and ripple lamination which alternates with fine-

grained clastic material (shale; e.g.. Cowan and James, 1993,

1996);

(2b) within a single heterolithic bed ("ribbon rocks")

whereby clastic material (mature quartz sand) comprises

coarser-grained planar laminations and ripple lamination

which alternates with thin intercalations of finer-grained

carbonate mud (e.g., Demicco and Hardie, 1994); (3a) between

vertically juxtaposed beds within high-frequency cycles

(meter-scale; "fifth"- and "fourth"-order) with a high-degree

of lithologic separation (e.g., Pennsylvanian "cyclothems";

Wilson, 1975; Driese and Dott, 1984; Atchley and Loope,

1993;

Yang, 1996; Rankey etal., 1999); (3b) between vertically

juxtaposed bedsets within tow-frequency sequences (deca-

meter-scale, "third-order") with a high-degree of lithologic

separation (e.g., basinal portions of "composite sequences" of

the Permian of west Texas; Silver and Todd, 1969; Meissner,

1972;

Tinker, 1998); (4a) between vertically juxtaposed beds

within high-frequency cycles (meter-scale; "fifth"- and

"fourth"-order) with a low degree of lithologic separation,

such that vertical contacts between elastics (typically) shale

and carbonates are gradational within a cycle (e.g., Grotzinger,

1986;

Osleger, 1991; Cowan and James, 1993); (4b) between

vertically juxtaposed beds within low-frequency sequences

(decameter-scale, "third-order") with a low degree of lithologic

separation, such that vertical, as well as lateral contacts

between elastics (typically shale) and carbonates are grada-

tional within a cycle (e.g., Grotzinger, 1986; Chow and James,

1987;

Sonnenfeld and Cross, 1993); (5) laterally within a single

bed as time-equivalent facies changes (spatial mixing; Houlik,

1973;

Shinn, 1973; Mount, 1984; Brett and Baird, 1985;

Grotzinger, 1986; Calvet and Tucker, 1988; Adams and

Grotzinger, 1996; Cowan and James, 1996); and (6) as

regionally extensive km-scale depositional systems that can

replace one another in time and space (Aitken, 1978; Byers and

Dott, 1981).

Models of clastic and carbonate mixing

Spatial variations in coeval environments

In his summary of mixed clastic-carbonate systems. Mount

(1984) highlighted four types of mixing of spatially separated

carbonate and clastic environments for shallow Holocene shelf

settings: (i) punctuated mixing—where sporadic storms and

other extreme, high-intensity periodic events transfer sediment

across highly contrasting environmental boundaries separating

elastics from carbonates; (ii) facies mixing—where sediments

are mixed along diffuse borders between contrasting facies, for

example nearshore clastic belts and offshore carbonate reefs or

ooid shoals; (iii) in situ mixing—where the carbonate fraction

consists of the authochthonous death assemblages of calcar-

eous organisms that accumulated on or within clastic

substrates, for example foram-mollusc assemblages within a

subtidal clastic

shelf;

and (iv) source mixing—where admix-

tures of carbonates into a clastic-dominated setting are

generated in response to uplift and erosion of proximal

carbonate terrains.