Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MATURATION, ORGANIC

425

Wetting inereases bulk weight

and

hence shear stress, while

changing effective stress

as the

groundwater table rises above

the level

of

the potential slip plane. Such concomitant changes

in stresses

may

occur within

a few

hours, explaining why many

slope failures occur during major storms (Selby, 1993),

On

a

longer timescale, slope undercutting

by

rivers

and

glaciers causes slope steepening

and

hence shear stress

increase. This induces slow creep movements within

a

slope,

causing

a

progressive reduction

in

both cohesion

and

frictional

resistance over time

and

hence long-term material fatigue.

Seismic shock often provides

the

final trigger

for

many

catastrophic slope failures

in a

wide range

of

materials,

ranging from hard, jointed rock

to

unconsolidated clays.

Types

of

mass movement

A common failure type

is the

translational slide, involving

a

slab-shaped detachment along

a

well-defined rupture surface.

In rock slopes, rock slides typically follow discontinuities such

as bedding, Joints, foliation

and

faults. Sliding

is

feasible only

where

the dip of the

discontinuity

is

less than

the

slope angle,

allowing

the

critical plane

to

crop

out on a

slope (Hoek

and

Bray, 1981), Large rock slides (20 Mm^

to

200 Mm')

are

often

seismically triggered

and

produce rock avalanches, since total

disintegration

of the

mass allows

Oow to

occur, Entrainment

of saturated valley-floor material provides

a

liquefied base

for

the

avalanche, allowing velocities

of

10

m

per

second

to

30 m

per

second. Exceptionally large liquefied failures, termed

lahars, result from collapse

of

stratovolcanoes (Vallance

and

Scott, 1997),

The

largest lahar deposits approach lO'm^, cover

tens

of km , and

rank

as the

largest landslides

on

Earth, High

mobility

of

lahars

is

caused

by

saturation

by

melting

of

ice

and

snow, drainage

of

volcanic crater lakes,

and

entrainment

of

saturated alluvial material.

On soil

and

debris covered slopes, translational debrisslides

occur along

the

soil-bedrock interface since soil shear strength

is lower than that

of

rock. Debris slides

are

typically

lO^m to

10^

m^

and are

triggered mainly

by

rainstorms. Scour

of

saturated material along

a

stream channel transforms many

debris slides into debris flows (Iverson

et al.,

1997), Debris

flows occur

in

every climatic zone, attaining velocities

of

5

m

per second

to 10m per

second

and

typical volumes

of

10"^m''

to

10^

ml

On slopes

cut

into thick clay

or

shale, deep-seated slumps

are common, involving

a

roughly cylindrical-arc slip surface

oblique

to the

stratification witii backward rotation

of the

landslide mass. Slumping creates

a

steep, debuttressed head-

scarp prone

to

further slumping,

a

process termed retro-

gression. Prolonged retrogression

may

produce

an

elongated

earth flow,

up to

several kilometers

in

length, moving

at

1

ma~' to

5ma~', with

a

total volume exceeding

lO^m , In

low density saturated silts

and

clays, liquefaction

may

occur

at

depth

as the

deposit collapses under shear loads, Frictional

strength declines notably

as

pore pressure rises, allowing

rapid acceleration

as a

quick clay flow-slide (Turner

and

Schuster, 1996), Flow-slide retrogression

may

occur

at

meters

per minute, with flow velocity attaining

1

m per

second

to

5

m per

second.

In permafrost areas, seasonal thaw

of

ice-rich soil produces

a 0,5 m

to LOm

thick water-saturated active layer above

permafrost material, Solifluction involves movement

of the

active layer

at

10~^ma~'

to

10~'

ma~' on

slopes

as low as 2°,

Movement

on

slopes well below

the

theoretical lowest angle

predicted

by

Mohr-Coulomb theory occurs

by a

combination

of frost

creep

and

gelifluction (Harris, 1987), Frost creep

is

soil

movement

by

alternating cycles

of

frost heave

and

thaw-

settlement

in

soils subjected

to ice

segregation, GeliHuction

is a

type

of

soil flow, occurring during seasonal thaw,

in

which

high water pressures develop during melting

of low

density,

ice-rich soil. Overburden pressure

is

largely borne

by the

pore-

water, allowing

low

effective stress

to

develop,

A

transient

phase

of

negligible frictional strength occurs, allowing soil

to

move

on

slopes substantially flatter than possible

in

saturated,

consolidated soils.

On

steeper slopes

in

permafrost areas, skin

flows involve rapid downslope detachment

of the

entire active

layer. Retrogressive thaw slumps

are

triggered

by

river under-

cutting

of

slopes

and

exposure

of

ice-rich sediments. Thaw

slumps

are the

largest slope failures found

in

permafrost areas,

Michael

J,

Bovis

Bibliography

Craig,

R,F,, 1997,

SoilMechanies.

6th edn,,

London: Spon Press,

Harris,

C, 1987,

Mechanisms

of

mass movement

in

periglacial areas,

tn Anderson,

M,G,, and

Richards (eds,). Slope Stability.

J,

Wiley

& Sons,

pp,

531-559,

Hoek,

E,, and

Bray,

J,W,, 1981,

Roek Slope Engineering.

3rd edn,,

London: Institution

of

Mining

and

Metallurgy,

tverson,

R,M,,

Reid,

M,E,, and

LaHusen,

R,G,, 1997,

Debris flow

mobilization from landslides. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary

Sciences,

25:

85-138,

Kenney,

T,C,, 1984,

Properties

and

behaviours

of

soils relevant

to

slope stability,

tn

Brunsden,

D,, and

Prior,

D,B,

(eds,). Slope

Instability. John Witey

&

Sons,

pp,

27-66,

Selby,

M,J,, 1993,

Hillslope Materials

and

Proeesses.

2nd edn,

Oxford

University Press,

Sidte,

R,C,,

Pearee,

A,J,, and

O'Loughhn,

C,L,,

1985, Hillslope Stabi-

lity and Land

Use.

American Geophysical Union,

Turner, A,K,,

and

Schuster,

R,L,

(eds,), 1996, Landslides:Investigation

and Mitigation. Washington,

DC:

National Academy Press,

pp,

585-606,

Vallance,

J,W,, and

Scott,

K,M,, 1997, The

Osceola Mudflow from

Mount Rainier; sedimentology

and

hazard implications

of a

huge

clay-rich debris flow, Geologieal Soeiety

of

Ameriea Bulletin,

109:

143-163,

Cross-references

Atterberg Limits

Avalanche

and

Rock Fall

Bentonites

and

Tonsteins

Debris Flow

Earth Flows

Grain Flow

Gravity-Driven Mass Flows

Liquefaction

and

Fluidization

Mudrocks

Slide

and

Stump Structures

Slurry

MATURATION, ORGANIC

Organic maturation refers

to the

progressive

and

mainly

irreversible transformation

of

organic matter (OM)

in

response

initially

to

biological

and

later

to

thermal energy. Organic

426

MATURATION, ORGANIC

maturation is also referred to as organic diagenesis, organic

metamorphism, and as coalification when referring to coal.

Organic matter is a minor component in most sedimentary

rocks,

however its importance by far outweighs its abundance.

Organic matter comprises the fossil fuel resources petroleum

and coal. The products of OM diagenesis govern many mineral

reactions and are important in the transport and deposition of

many ore minerals. Studies of organic maturation have mainly

been pursued form two separate avenues: organic geochemists

have investigated the chemical reactions and products of

organic maturation particularly from the perspective of

petroleum whereas coal petrologists have studied organic

maturation of coal mainly microscopically.

Introduction

Diagenesis of OM has been considered in terms of three or

four stages by various authors (e,g,, Tissot etal., 1974; Bustin,

1989;

Diessel, 1992), Eogenesis has been used in reference to

biological, physical and chemical changes in OM that occur at

low temperatures where reactions are mainly biologically

mediated, Diagenesis, at higher temperatures normally asso-

ciated with greater depths of burial, is successively referred to

as catagenesis and metagenesis. Diagenetic reactions of OM

due to contact with free oxygen or meteoric water has been

refereed to as telogenesis. The bouridary between different

diagenetic stages is gradational as a result of the heterogeneity

of the OM and biological processes. The different coal ranks

from peat to lignite, subbituminous, high-, medium-, and low-

volatile bituminous coal, semi-anthracite and anthracite, are

names sequentially assigned to successively more carbon-rich

and volatile-poor coals that form in response to progressive

diagenesis.

Substantial research exists on the kinetics of organic

diagenesis because of the importance of predicting the timing

and volume of hydrocarbon generation from the diagenesis of

kerogens. As well, sophisticated numerical models have been

proposed that attempt to predict organic maturation based on

the thermal history of the strata and the activation energy of

various kerogen types. Because many of the products of

organic diagenesis are metastable and rocks are open to

migration of products (hydrocarbons), thermodynamic equili-

brium is rarely ever established,

Eogenesis

Eogenesis refers to low temperature diagenesis of OM, where

reactions are at least in part biochemical resulting from

metabolic processes of organisms, and the effects of tempera-

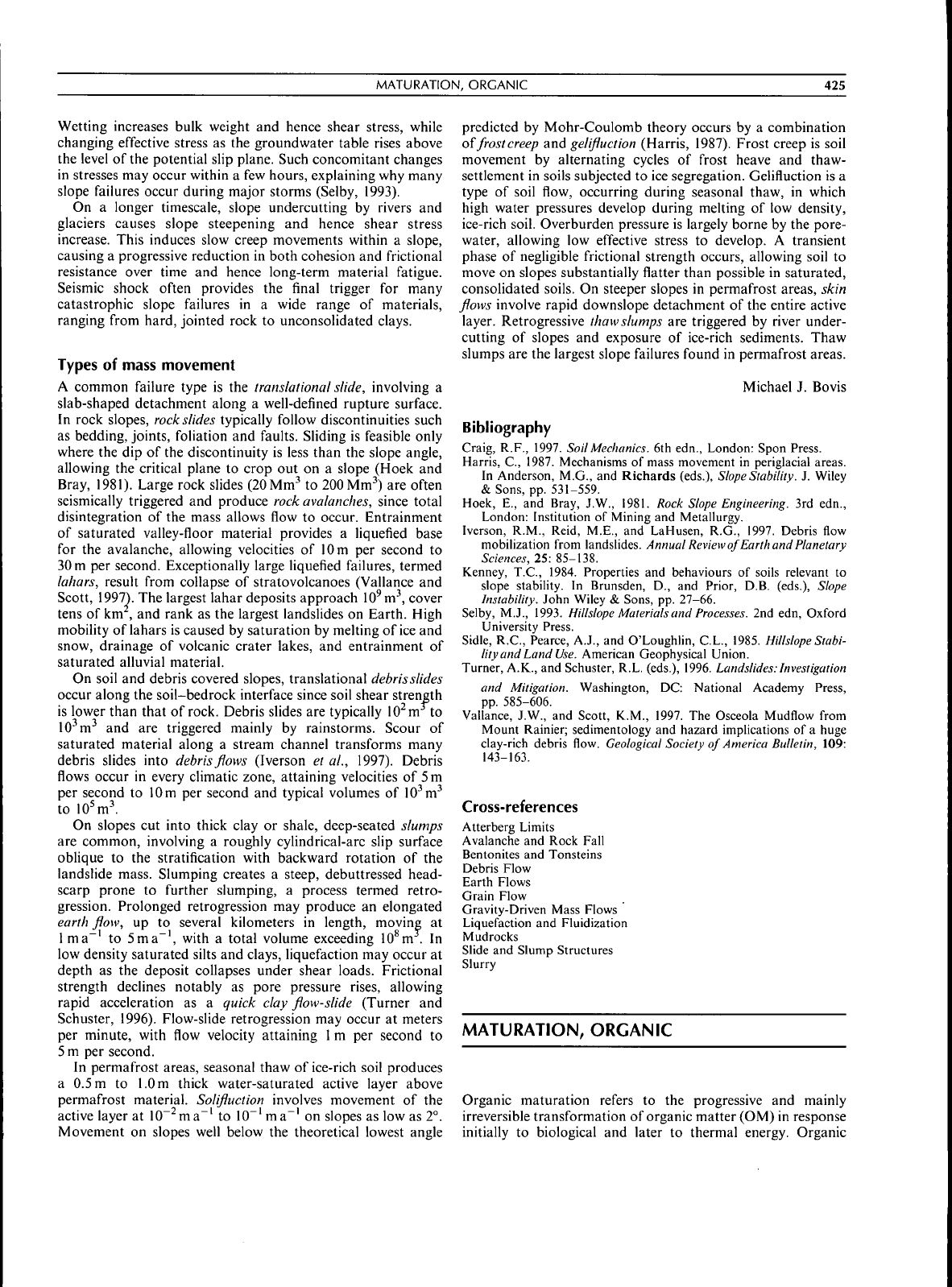

ture and pressure are subordinate (Figure M7), Due to the

diversity of mierobial processes and organic substrates,

reactions during eogenesis are complicated and poorly under-

stood. Different depositional settings give rise to different

diagenetic processes and sources of OM, which in turn

influence the type and rate of degradation of the OM mainly

by bacteria, actinomyces and fungi. For OM to be preserved at

all to further undergo diagenesis requires rather specific

depositional conditions. It is clear that in subaerial environ-

ments chemical oxidation and aerobic mierobial decomposi-

tion invariable leads to complete decomposition of the OM,

Anaerobic mierobial processes are generally slower and hence

eogenetie reactions are commonly retarded sueh that there is

greater potential for a portion of the OM to be preserved. For

Biogenic

poiymers

Monomers

03

m

z

CO2,

H2O,

CH4

NO3,

NH4+

SO4-,

S-,

HS-

Ro-0,5

Geochemicai fossiis

free iHCs and reiated

compounds

en

CO

z

LU

Low to

med,

MWHCs

High

MW

HCs

" Ro-2,0

eking

-^J

Methane, iight HCs condensates

Methane (dry gas)

Oii

Gas&

METAGENESIS

Graphite, iarge

condensed aromatics

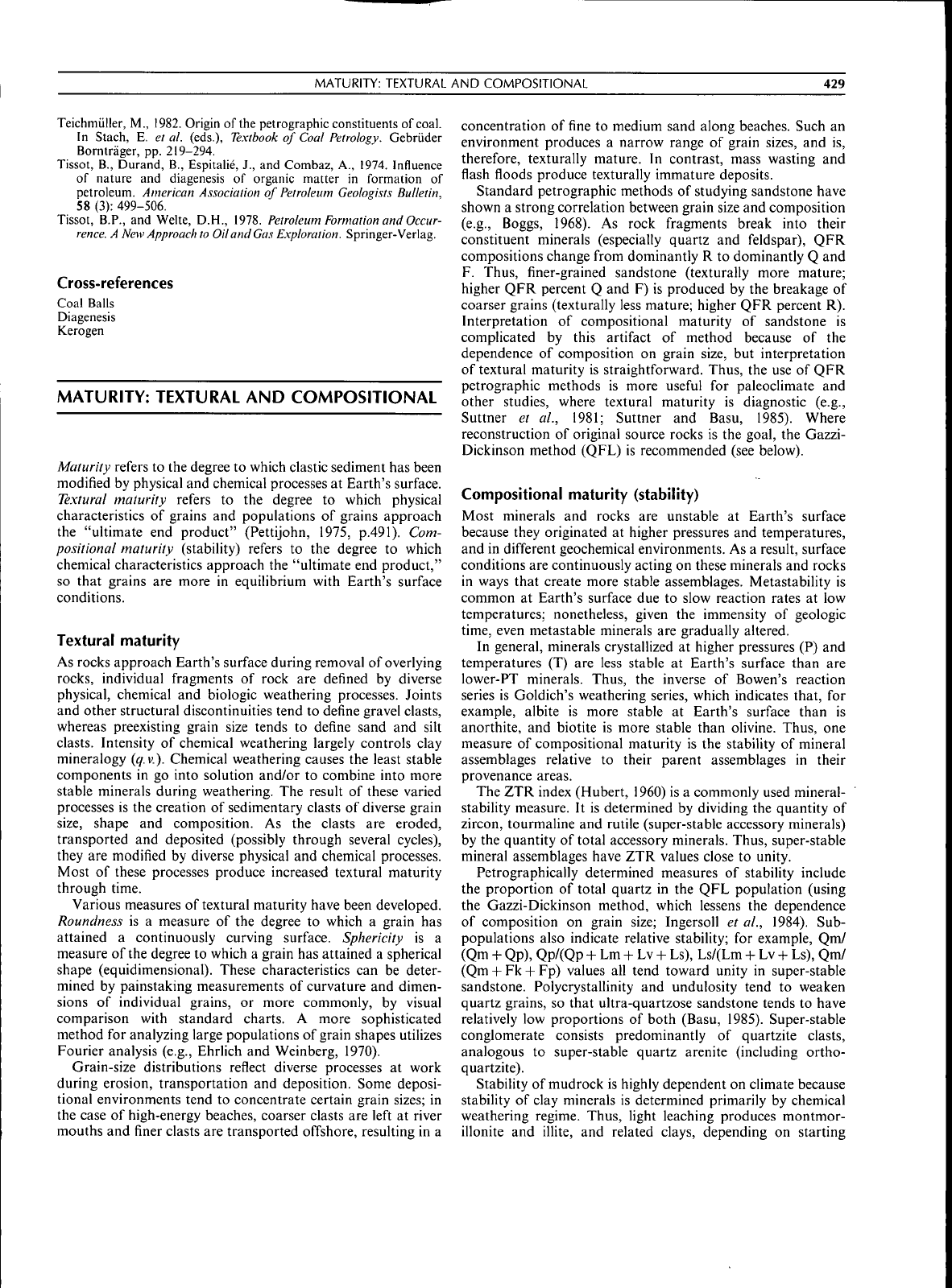

Figure M7 Schematic diagenetic pathway of organic matter in

sediments. Modified after Barnes et al. (1990),

OM to survive eogenesis and to move on to catagenesis, it

must be rapidly removed from oxic conditions. Proteins,

carbohydrates (^sugars, cellulose, and chitin), lipids (fats,

waxes, and steryl esters) and lignins are the main biopolymers

contributed by organisms to the sediment, Biopolymers are

variously depolymerized during eogenesis forming what is

colloquially referred to geopolymers, which are essentially

fulvic and humic acids, humins and kerogens (Bustin, 1999),

Geopolymers are detined on their solubility, their molecular

weight and, because they form by random recombination,

their structures, Geopolymers vary depending on available

monomers and diagenetic conditions. With increasing cross-

linkage and loss of acidic functional groups (carboxyl and

phenolic hydroxyl groups), the humic and fulvic acids lose

their base solubility and form an insoluble humin/kerogen

residue. The term humin is used for base insoluble fraction of

the OM in soils, whereas kerogen refers to the organic fraction

in rocks, which is insoluble in organic solvents. The details of

diagenetic reactions leading to kerogen formation remain

poorly understood. Some kerogen forms through loss of

functional groups and cross-linkage formation early in

diagenesis, but others later during catagenesis and still other

kerogen appears to arise directly from monomers without an

intervening humic stage particularly under anoxic conditions.

The lipid-rich components are particularly resistant to

biochemical processes and unless degradation is particularly

intense, these components survive eogenesis. An important

product of eogenesis is the formation of mainly methane (up to

99 percent), carbon dioxide (0 percent to 8 percent) and minor

MATURATION, ORGANIC

427

heavier gases by fermentation reactions. This biogenic gas may

source significant economic accumulations both in the coal

(coalbed methane) and conventional reservoirs. Carbon

dioxide generated together with organic degradation products

influences the Eh, pH, and ionic composition of pore waters

and thus plays a role in diagenesis of minerals.

The end of eogenesis generally occurs when the microscopic

reflectance of coal maceral vitrinite is about 0.5 percent, which

also corresponds to the boundary between subbituminous

coal and high-volatile bituminous coal. At this stage

base-soluble compounds are usually negligible and thermal

energy is required for further diagenesis.

Catagenesis

Diagenesis beyond the eogenetic stage is in response to thermal

exposure (temperature and time), generally accompanying

burial in a sedimentary basin or high heat flow adjacent

intrusive or extrusive bodies (Figure M7). The rate of organic

diagenesis is exponential with temperature and linear with

time.

Confining pressure has little effect during organic

diagenesis apart from compaction during the peat and lignite

stages and some experiments suggest high confining pressure

retard catagenetic and metagenetic reactions. Catagenetic

reactions take place at temperatures of around 40°C to

150°C and moderate pressures (30-150 MPa), often producing

significant amounts of petroleum, methane and carbon

dioxide. The amount and type of liquid hydrocarbons

generated varies with the type of" kerogens present. Generally

most coals are considered to have little liquid hydrocarbon

potential whereas algal-rich, fine-grained rocks are excellent

liquid hydrocarbon source rocks. During catagenesis coal rank

progressively increases from subbituminous to anthracite and

kerogen increases in carbon content, decreases in volatiles,

aliphatic chains are cleaved and the size of aromatic clusters

grows through condensation and development of ordering.

Coincident with the generation of gas, the surface area of the

kerogen increases such that significant quantities of the

generated gas are adsorbed in the matrix (up to about 30 mV

tonne for coal) giving rise to coalbed methane. Coalbed

methane (and gas shale), is an important energy resource,

however, it is also a potential explosive hazard during coal

mining. The exact level of catagenesis for liquid hydrocarbon

generation (oil birth line) varies with the chemical composition

of the kerogen. The catagenetic level at which liquid

hydrocarbons begin to crack is referred to as the oil death

line.

The zone of catagenesis between the birth and death

"lines"

is referred to as the oil window or oil kitchen

(Figure M7).

Organic matter undergoes noticeable transformations that

are observable microscopically even at the beginning of the

eogenetic stage. The fraction of the OM derived from higher

plants, mainly cellulose and lignin, give rise to the micro-

scopically defined maceral huminite (at low maturation levels)

and later vitrinite. The reflectivity of huminite/vitrinite

progressively increases, as observed microscopically in re-

flected light through diagenesis. This degree of reflectance can

be measured with a specially designed microscope and is

referred to as vitrinite reflectance. Vitrinite reflectance is the

most widely used method for determining the degree of

diagenesis of coals and OM in rocks. During catagenesis

vitrinite reflectance progressively increases from about 0.5

percent to 2.0 percent (Figure M7). Liptinite components

change little until the oil birth line which corresponds to a

vitrinite reflectance of about 0.5 percent and then it become

progressively brighter and merge in brightness with vitrinite at

a reflectance of about 1.4 percent (the death line of oil). The

fraction of the OM rich in lipids is microscopically darker

than vitrinite and is referred to as liptinite. The liptinite

macerals change little with diagenesis until the onset of the oil

window at which time there is a "jump" in diagenesis as HCs

are generated (Figure M7). That microscopically defined

fraction of the OM that is semi charred or charred at the site

of deposition (charcoal) is referred to respectively as semi-

fusinite and inertinite. These materials being variously pre-

coalified undergo little change during diagenesis.

Metagenesis

Metagenesis refers to the level of diagenesis of the OM at

which crystalline ordering of the OM begins (Figure M7).

Aromatic clusters increase in size and C-C bonds are broken

generating additional methane. Any remnant aliphatic mole-

cules and any previously formed heavier hydrocarbons are

cracked to methane. The remaining kerogen becomes further

enriched in carbon with loss of volatiles. Microscopically the

reflectance of vitrinite progressively increases from about

2.0 percent to 10 percent or more and the liptinite component

and lower reflecting inertinite components become visually

indistinct from vitrinite. Early studies argued that graphite is

the end point of coal diagenesis however field and experimental

evidence now suggest that the activation energy for formation

of graphite is so high that it is unlikely that it will form in

nature by thermal exposure alone (Figure M7).

Telogenesis

Organic matter diagenesis is progressive and for the most part

irreversible. Organic matter at all stages of diagenesis is

reduced and subsurface environments are typically anaerobic.

Where, however, OM is uplifted to the surface or comes in

contact with oxygenated meteoric water, it is subjected to

oxidation. Oxidative processes are collectively refereed to as

teleogenesis and result in marked changes in the OM. During

oxidation nonaromatic groups are selectively removed and

acidic functional groups such as carboxyl, carbonyl and

phenolic hydroxyl are formed leading to production of humic

acids.

The oxidative diagenetic processes have a deleterious

effect on coal quality: coking coals loose their ability to form

coke,

thermal coals decline in calorific value and coal particles

loose their hydrophobicity and thus are difficult to separate

from mineral matter during coal processing (Copard et al.,

2002;

Teichmiiller, 1982). If oxidation is intense it may be

microscopically evident by distinctive darkish halo along

boundaries of organic particles. With pooled hydrocarbons

two distinct telogenesis processes occur: (1) water washing

which results in selective removal of lighter hydrocarbons by

groundwater; and (2) bacterial degradation which can lead to

loss of normal alkanes and isoprenoids leaving a heavier oil

residue enriched in cycloalkanes and aromatics. These two

processes are considered responsible for formation of the

heavy oil deposits.

428 MATURATION, ORGANIC

METAGENESIS CATAGENESIS

EOGENESIS

0)

Anthracite

emi-

thra

-< 1-

3

•

^

Medium

volatile

bituminous

A |B| C

Higfi vol. bituminous^

JSub-bitum.

Lignite Peat

10 20 30

40

50 60 70

kJ/kg

36,000 36,000

29,000 23,000

17,000

2.5 5.5 10

25

%H

35

% H2O

dry gas

wet

gas

oil

and gas

early gas

1.51.35

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.4

0.3 0.15

no fluorescence

-500 Sporinite

"600 fluorescence

•700 (rnax.)

no fluorescence

black dark dark-brown

brown-black

4.0 3.8 3.7 3.5

red-

orange- yellow-

brown brown orange

1.0

black black very dark

grey brown dark brown

brown to very pale brown pale yellow

1.5

£.3

o-O

485°C 47O''C

450°C

435°C

425°C

based on:

(C25-C33)]

kerogen type I and II

DIAGENETIC LEVEL

Coal rank

Volatile matter

Coal (daf)

Calorific value

Moisture (ash free)

Hydrogen (daf)

HC generation

Vitrinite reflectance

(Rpmax %)

1 Sporinite

1

Fluorescence

Spectral-

quotient

Spore colour

and

TAI

Conodont colour

and alteration

index(CAI)

Atomic

ratio

Pyrolysis (S2)

^ Carbon

-1.4 Preference

Q Index (CPI)

I

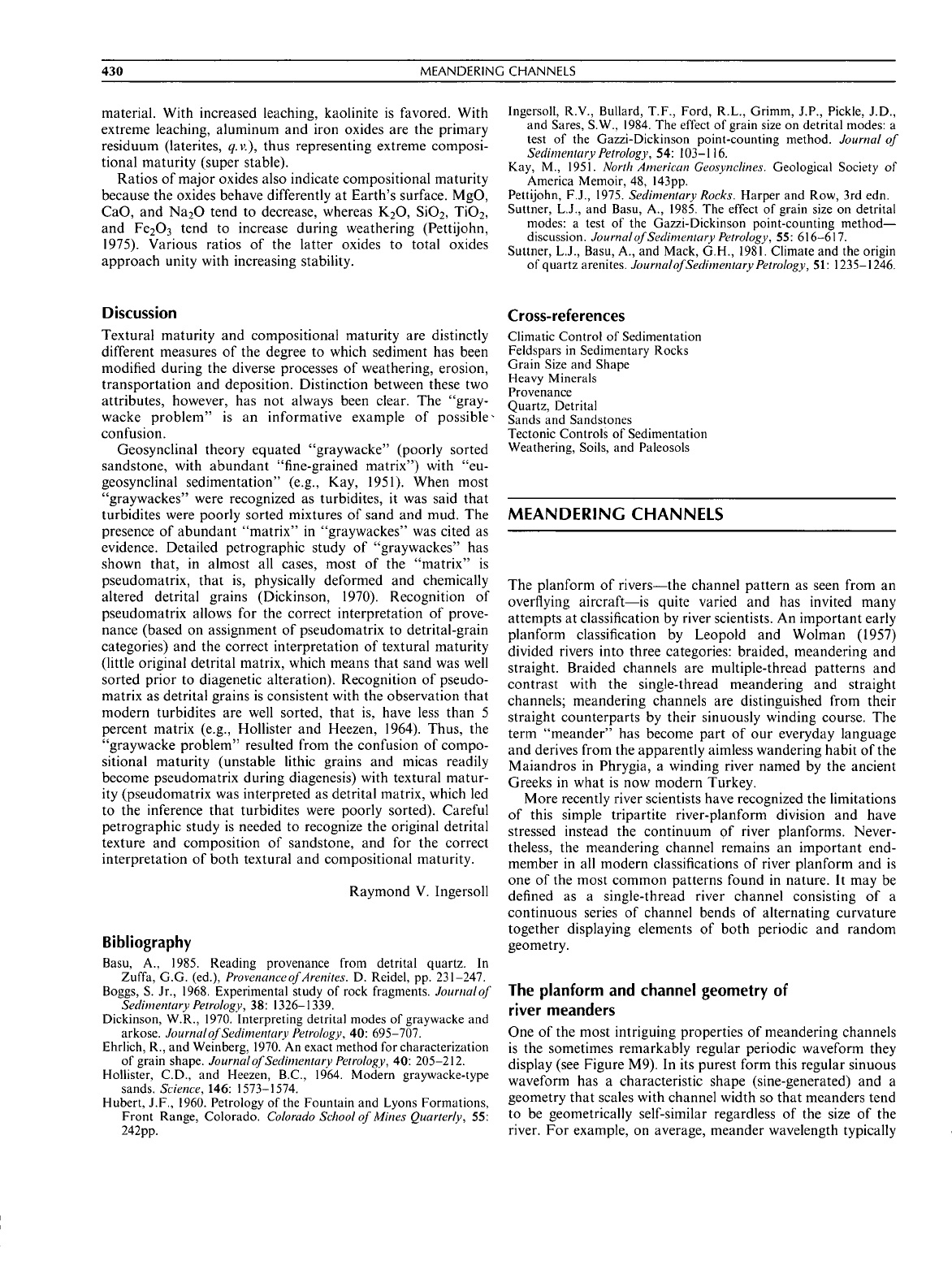

Figure M8 Correlation of major organic maturation indices. The correlation shown is based on virtinite reflectance. Modified after

Bustin et al. (1990).

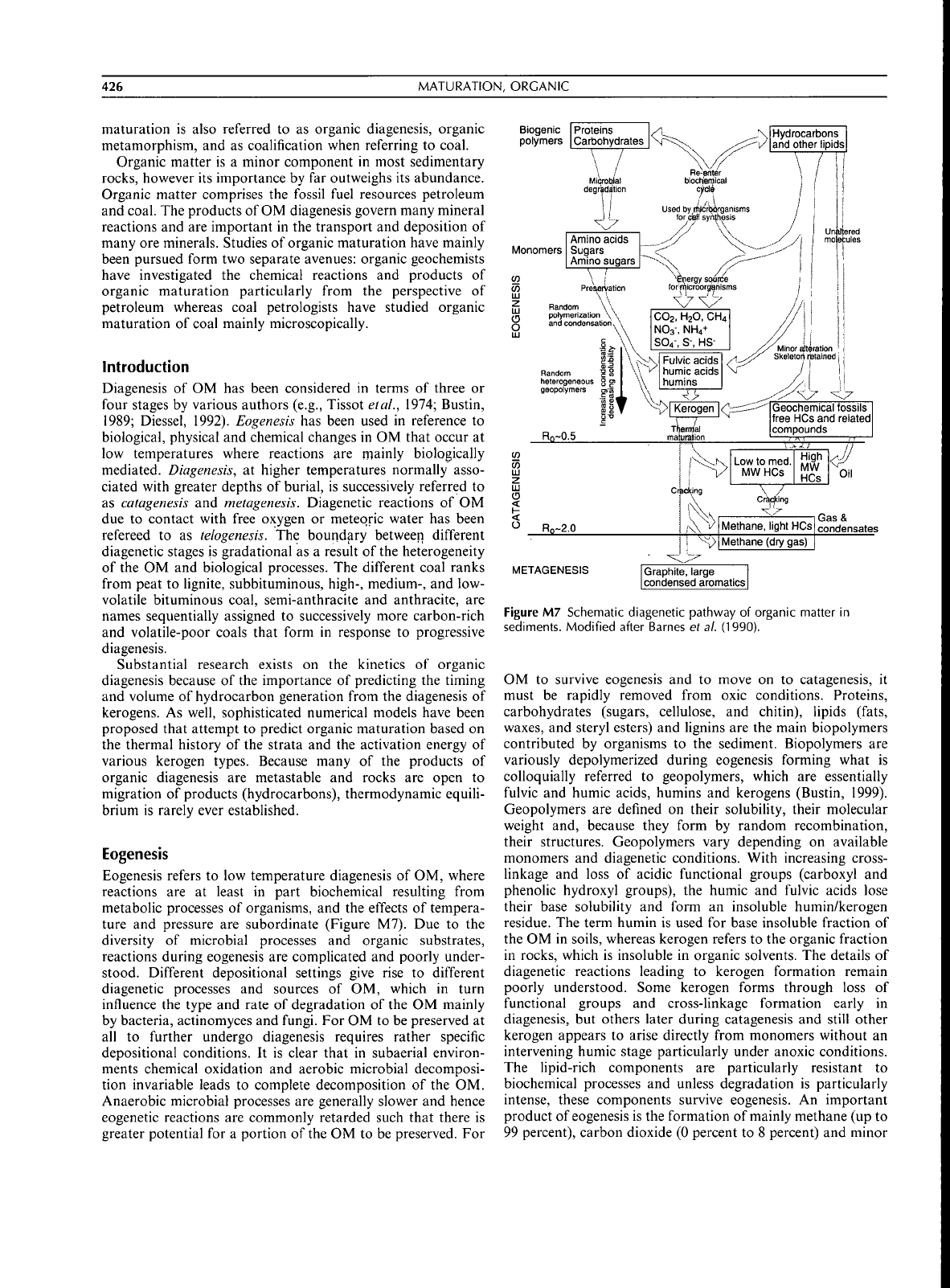

Quantifying organic diagenesis

Both the kerogens and bitumen fraction of the OM have been

used to quantify diagenesis by chemical, physical and

microscopic methods (Bustin etal., 1990; Tissot and Welte,

1978).

In Figure M8, the correlation between the major

different diagenesis indices is provided. A few of the more

common techniques are summarized below. The reflectance of

vitrinite, and its precursor huminite is the most widely

accepted method of quantifying organic diagenesis and the

method to which all others are compared. Vitrinite reflectance

is measured microscopically using a highly polished specific

and a specialized microscope equipped with a photometer.

With increasing levels of diagenesis the reflectivity of vitrinite

increases in a predictable fashion. Characteristics of coal have

often been used as diagenetic indicators. The volatile matter,

moisture, and hydrogen content of coal decrease with

increasing diagenesis and the carbon content and calorific

value increase in a predictable manner (Figure M8). The

chemistry of kerogens has also been found to be useful

indicator. For example the hydrogen to carbon ratio and

pyrolysis yield of kerogens decrease with increasing diagenesis.

The carbon preference index (ratio of odd to even n-alkanes)

also progressively decreases with diagenesis from values

greater than 1 (due to initial organic selectively) to values

approaching one as diagenesis progresses.

The fluorescence of liptinite macerals has been utilized in

some studies. With increasing levels of diagenesis the intensity

of fluorescence decreases and the wavelength of maximum

fluorescence progressively increase. Such measurements re-

quire a microscope equipped with a scanning monochromatic

filter and sensitive photometer.

Kerogen coloration in transmitted light including pollen,

spores and eonodonts has been successively used to quantify

maturation. As with toast, the OM darkens with increases with

degree of thermal exposure and specialists attribute the colors

to various numerical schemes based on visual examination.

The color of kerogens has been referred to as the Thermal

Alteration Index, whereas the color of eonodonts is referred

to the Conodont Alteration Index (CAI) (Figure M8).

R. Marc Bustin and Raphael A.J. Wust

Bibliography

Barnes, M.A., Barnes, W.C, and Bustin, R.M., 1990. Chemistry and

diagenesis of organic matter in sediments and fossil fuels. In

Mcllreath, I.A., and Morrow, D.W. (eds.), Diagenesis. Geological

Association of Canada, pp. 189-204.

Bustin, R.M., 1989. Diagenesis of kerogen. In Hutcheon, I.E. (ed.),

BuriaiDiagenesis. GAC/MAC Short Course Handbook. Montreal,

Quebec: Mineralogical Association of Canada, pp. 1-38.

Bustin, R.M., 1999. Coal: origin and diagenesis. In Marshall, C.P., and

Fairbridge, R.W. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Geochemistry. Kluwer

Academic, pp. 90-92.

Bustin, R.M., Barnes, M.A., and Barnes, W.C, 1990. Determining

levels of organic diagenesis in sediments and fossil fuels. In

Mcllreath, I.A., and Morrow, D.W. (eds.), Diagenesis. Geological

Association of Canada, pp. 205-226.

Copard, Y., Disnar,

J.-R.,

and Becq-Giraudon, J.F., 2002. Erroneous

maturity assessment given by Tmax and HI Rock-Eval parameters

on highly mature weathered coals. Internalionai Journal of Coal

Geology, 49 (1): 57-65.

Diessel, C.F.K., 1992. Coal-bearing Deposilional Systems. Springer-

Verlag.

MATURITY: TEXTURAL AND COMPOSITIONAL

429

Teichmiiller, M., 1982. Origin of the petrographic constituents of coal.

In Stach, E. et at. (eds.), Textbook of Coal Petrology. Gebriider

Borntrager, pp. 219-294.

Tissot, B., Durand, B., Espitalie, J., and Combaz, A., 1974. Influence

of nature and diagenesis of organic matter in formation of

petroleum. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin,

58 (3): 499-506.

Tissot, B.P., and Welte, D.H., 1978. Petroleum Formation and Occur-

rence. A New Approach

to

Oil and

Gas

Exploration. Springer-Verlag.

Cross-references

Coal Balls

Diagenesis

Kerogen

MATURITY: TEXTURAL AND COMPOSITIONAL

Maturity refers to the degree to which clastic sediment has been

modified by physical and chemical processes at Earth's surface.

Textural maturity refers to the degree to which physical

characteristics of grains and populations of grains approach

the "ultimate end product" (Pettijohn, 1975, p.491). Com-

positional maturity (stability) refers to the degree to which

chemical characteristics approach the "ultimate end product,"

so that grains are more in equilibrium with Earth's surface

conditions.

Textural maturity

As rocks approach Earth's surface during removal of overlying

rocks,

individual fragments of rock are defined by diverse

physical, chemical and biologic weathering processes. Joints

and other structural discontinuities tend to define gravel clasts,

whereas preexisting grain size tends to define sand and silt

clasts.

Intensity of chemical weathering largely controls clay

mineralogy

{q.v.).

Chemical weathering causes the least stable

components in go into solution and/or to combine into more

stable minerals during weathering. The result of these varied

processes is the creation of sedimentary clasts of diverse grain

size,

shape and composition. As the clasts are eroded,

transported and deposited (possibly through several cycles),

they are modified by diverse physical and chemical processes.

Most of these processes produce increased textural maturity

through time.

Various measures of textural maturity have been developed.

Roundness is a measure of the degree to which a grain has

attained a continuously curving surface. Sphericity is a

measure of the degree to which a grain has attained a spherical

shape (equidimensional). These characteristics can be deter-

mined by painstaking measurements of curvature and dimen-

sions of individual grains, or more commonly, by visual

comparison with standard charts. A more sophisticated

method for analyzing large populations of grain shapes utilizes

Fourier analysis (e.g., Ehrlich and Weinberg, 1970).

Grain-size distributions reflect diverse processes at work

during erosion, transportation and deposition. Some deposi-

tional environments tend to concentrate certain grain sizes; in

the case of high-energy beaches, coarser clasts are left at river

mouths and finer clasts are transported offshore, resulting in a

concentration of fine to medium sand along beaches. Such an

environment produces a narrow range of grain sizes, and is,

therefore, texturally mature. In contrast, mass wasting and

flash floods produce texturally immature deposits.

Standard petrographic methods of studying sandstone have

shown a strong correlation between grain size and composition

(e.g., Boggs, 1968). As rock fragments break into their

constituent minerals (especially quartz and feldspar), QFR

compositions change from dominantly R to dominantly Q and

F.

Thus, finer-grained sandstone (texturally more mature;

higher QFR percent Q and F) is produced by the breakage of

coarser grains (texturally less mature; higher QFR percent R).

Interpretation of compositional maturity of sandstone is

complicated by this artifact of method because of the

dependence of composition on grain size, but interpretation

of textural maturity is straightforward. Thus, the use of QFR

petrographic methods is more useful for paleoclimate and

other studies, where textural maturity is diagnostic (e.g.,

Suttner et al., 1981; Suttner and Basu, 1985). Where

reconstruction of original source rocks is the goal, the Gazzi-

Dickinson method (QFL) is recommended (see below).

Compositional maturity (stability)

Most minerals and rocks are unstable at Earth's surface

because they originated at higher pressures and temperatures,

and in different geochemical environments. As a result, surface

conditions are continuously acting on these minerals and rocks

in ways that create more stable assemblages. Metastability is

common at Earth's surface due to slow reaction rates at low

temperatures; nonetheless, given the immensity of geologic

time,

even metastable minerals are gradually altered.

In general, minerals crystallized at higher pressures (P) and

temperatures (T) are less stable at Earth's surface than are

lower-PT minerals. Thus, the inverse of Bowen's reaction

series is Goldich's weathering series, which indicates that, for

example, albite is more stable at Earth's surface than is

anorthite, and biotite is more stable than olivine. Thus, one

measure of compositional maturity is the stability of mineral

assemblages relative to their parent assemblages in their

provenance areas.

The ZTR index (Hubert, 1960) is a commonly used mineral-

stability measure. It is determined by dividing the quantity of

zircon, tourmaline and rutile (super-stable accessory minerals)

by the quantity of total accessory minerals. Thus, super-stable

mineral assemblages have ZTR values close to unity.

Petrographically determined measures of stability include

the proportion of total quartz in the QFL population (using

the Gazzi-Dickinson method, which lessens the dependence

of composition on grain size; lngersoll et al., 1984). Sub-

populations also indicate relative stability; for example, Qm/

(Qm + Qp), Qp/(Qp + Lm + Lv + Ls), Ls/(Lm + Lv -f Ls), Qm/

(Qm

4-

Fk -h Fp) values all tend toward unity in super-stable

sandstone. Polycrystallinity and undulosity tend to weaken

quartz grains, so that ultra-quartzose sandstone tends to have

relatively low proportions of both (Basu, 1985). Super-stable

conglomerate consists predominantly of quartzite clasts,

analogous to super-stable quartz arenite (including ortho-

quartzite).

Stability of mudrock is highly dependent on climate because

stability of clay minerals is determined primarily by chemical

weathering regime. Thus, light leaching produces montmor-

illonite and illite, and related clays, depending on starting

430 MEANDERING CHANNELS

material. With increased leaching, kaolinite

is

favored. With

extreme leaching, aluminum

and

iron oxides

are the

primary

residuum (laterites,

q.v.),

thus representing extreme composi-

tional maturity (super stable).

Ratios

of

major oxides also indicate compositional maturity

because

the

oxides behave differently

at

Earth's surface.

MgO,

CaO,

and

Na20 tend

to

decrease, whereas

K2O,

SiO2, TiO2,

and Fe2O3 tend

to

increase during weathering (Pettijohn,

1975).

Various ratios

of the

latter oxides

to

total oxides

approach unity with increasing stability.

lngersoll,

R.V.,

BuUard,

T.F.,

Ford,

R.L.,

Grimm,

J.P.,

Pickle,

J.D.,

and Sares,

S.W.,

1984.

The

effect

of

grain size

on

detrital modes:

a

test

of the

Gazzi-Dickinson point-counting method. Journal

of

Sedimentary

Petrology,

54:

103-116.

Kay,

M., 1951.

North American Geosynclines. Geological Society

of

America Memoir,

48,

143pp.

Pettijohn,

F.J.,

1975. Sedimentary Rocks. Harper

and Row, 3rd edn.

Suttner,

L.J., and

Basu,

A.,

1985.

The

effect

of

grain size

on

detrital

modes:

a

test

of the

Gazzi-Dickinson point-counting method—

discussion. Journalof Sedimentary Petrology,

55:

616-617.

Suttner,

L.J.,

Basu,

A., and

Mack,

G.H.,

1981. Climate

and the

origin

of quartz arenites. Journalof Sedimentary

Petrology,

51: 1235-1246.

Discussion

Textural maturity

and

compositional maturity

are

distinctly

different measures

of the

degree

to

which sediment

has

been

modified during

the

diverse processes

of

weathering, erosion,

transportation

and

deposition. Distinction between these

two

attributes, however,

has not

always been clear.

The

"gray-

wacke problem"

is an

informative example

of

possible'

confusion.

Geosynclinal theory equated "graywacke" (poorly sorted

sandstone, with abundant "fine-grained matrix") with

"eu-

geosynclinal sedimentation" (e.g.,

Kay,

1951). When most

"graywackes" were recognized

as

turbidites,

it was

said that

turbidites were poorly sorted mixtures

of

sand

and mud. The

presence

of

abundant "matrix"

in

"graywackes"

was

cited

as

evidence. Detailed petrographic study

of

"graywackes"

has

shown that,

in

almost

all

cases, most

of the

"matrix"

is

pseudomatrix, that

is,

physically deformed

and

chemically

altered detrital grains (Dickinson, 1970). Recognition

of

pseudomatrix allows

for the

correct interpretation

of

prove-

nance (based

on

assignment

of

pseudomatrix

to

detrital-grain

categories)

and the

correct interpretation

of

textural maturity

(little original detrital matrix, which means that sand

was

well

sorted prior

to

diagenetic alteration). Recognition

of

pseudo-

matrix

as

detrital grains

is

consistent with

the

observation that

modern turbidites

are

well sorted, that

is,

have less than

5

percent matrix (e.g., Hollister

and

Heezen, 1964). Thus,

the

"graywacke problem" resulted from

the

confusion

of

compo-

sitional maturity (unstable lithic grains

and

micas readily

become pseudomatrix during diagenesis) with textural matur-

ity (pseudomatrix

was

interpreted

as

detrital matrix, which

led

to

the

inference that turbidites were poorly sorted). Careful

petrographic study

is

needed

to

recognize

the

original detrital

texture

and

composition

of

sandstone,

and for the

correct

interpretation

of

both textural

and

compositional maturity.

Raymond

V.

lngersoll

Bibliography

Basu,

A., 1985.

Reading provenance from detrital quartz.

In

Zuffa,

G.G.

(ed.).

Provenance

of Arenites.

D.

Reidel,

pp.

231-247.

Boggs,

S. Jr., 1968.

Experimental study

of

rock fragments. Journalof

Sedimentary

Petrology,

38:

1326-1339.

Dickinson,

W.R.,

1970. Interpreting detrital modes

of

graywacke

and

arkose. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology,

40:

695-707.

Ehrlich,

R., and

Weinberg, 1970.

An

exact method

for

characterization

of grain shape. Journalof Sedimentary

Petrology,

40:

205-212.

Hollister,

CD., and

Heezen,

B.C., 1964.

Modern graywacke-type

sands.

Science, 146: 1573-1574.

Hubert, J.F., 1960. Petrology

of

the Fountain

and

Lyons Formations,

Front Range, Colorado. Colorado School

of

Mines Quarterly,

55:

242pp.

Cross-references

Climatic Control

of

Sedimentation

Feldspars

in

Sedimentary Rocks

Grain Size

and

Shape

Heavy Minerals

Provenance

Quartz, Detrital

Sands

and

Sandstones

Tectonic Controls

of

Sedimentation

Weathering, Soils,

and

Paleosols

MEANDERING CHANNELS

The planform

of

rivers—the channel pattern

as

seen from

an

overflying aircraft—is quite varied

and has

invited many

attempts

at

classification

by

river scientists.

An

important early

planform classification

by

Leopold

and

Wolman (1957)

divided rivers into three categories: braided, meandering

and

straight. Braided channels

are

multiple-thread patterns

and

contrast with

the

single-thread meandering

and

straight

channels; meandering channels

are

distinguished from their

straight counterparts

by

their sinuously winding course.

The

term "meander"

has

become part

of our

everyday language

and derives from

the

apparently aimless wandering habit

of

the

Maiandros

in

Phrygia,

a

winding river named

by the

ancient

Greeks

in

what

is now

modern Turkey.

More recently river scientists have recognized

the

limitations

of this simple tripartite river-planform division

and

have

stressed instead

the

continuum

of

river planforms. Never-

theless,

the

meandering channel remains

an

important

end-

member

in all

modern classifications

of

river planform

and is

one

of the

most common patterns found

in

nature.

It may be

defined

as a

single-thread river channel consisting

of a

continuous series

of

channel bends

of

alternating curvature

together displaying elements

of

both periodic

and

random

geometry.

The planform

and

channel geometry

of

river meanders

One

of the

most intriguing properties

of

meandering channels

is

the

sometimes remarkably regular periodic waveform they

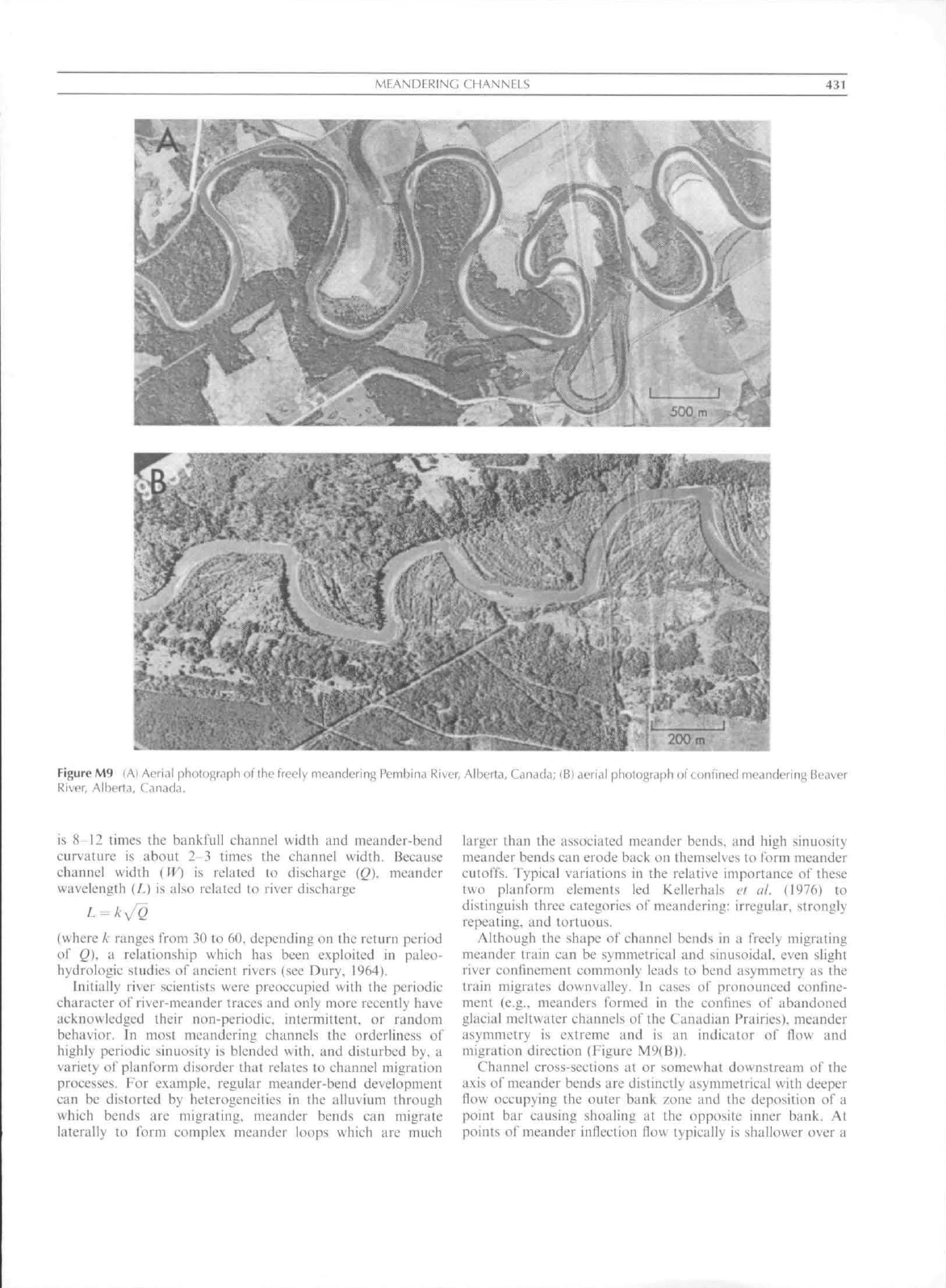

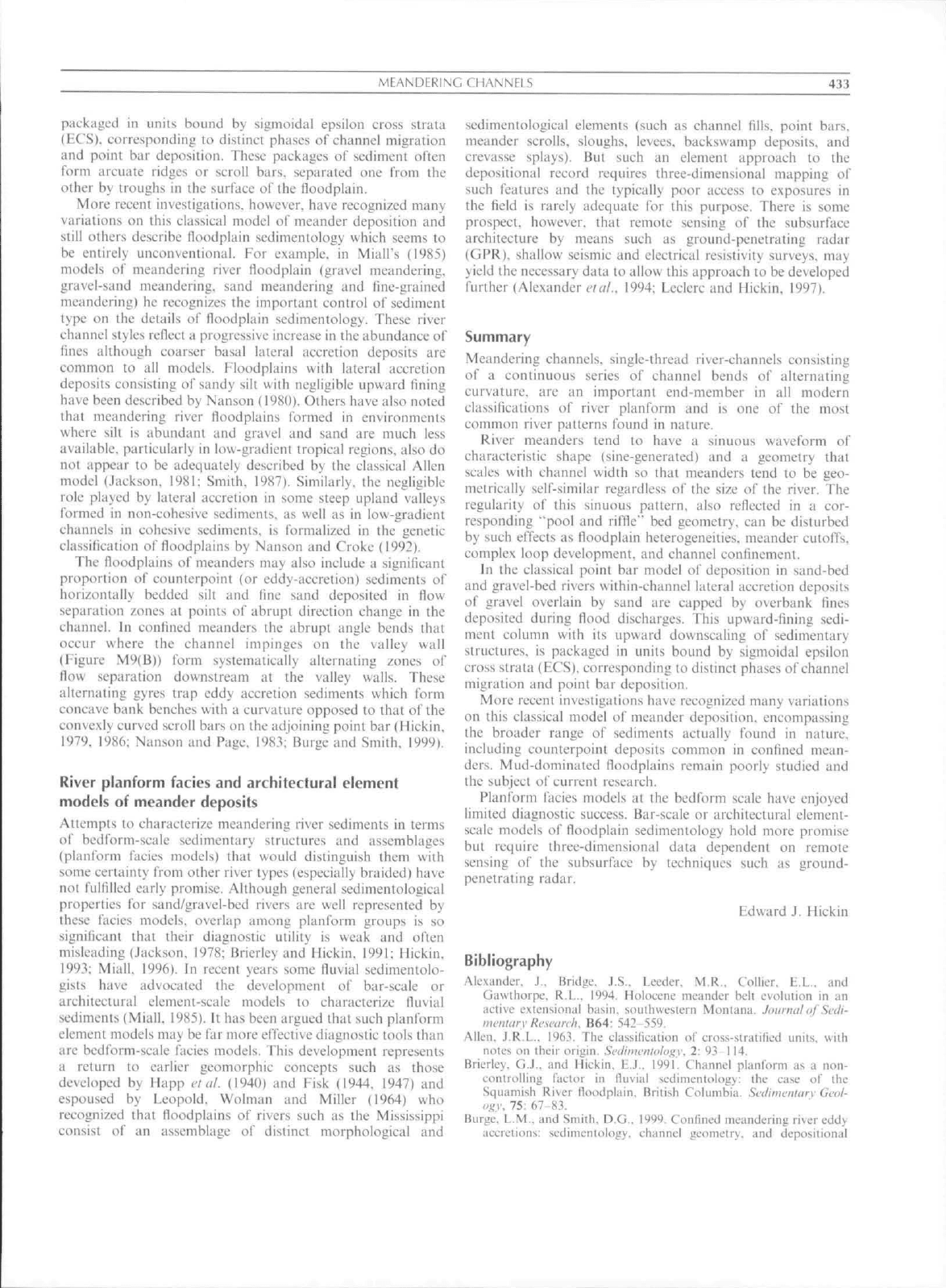

display (see Figure M9).

In its

purest form this regular sinuous

waveform

has a

characteristic shape (sine-generated)

and a

geometry that scales with channel width

so

that meanders tend

to

be

geometrically self-similar regardless

of the

size

of the

river.

For

example,

on

average, meander wavelength typically

MEANDERING CHANNEI

S

431

2CX)m

Figure M9 (A) Aeri.il photofiraph of the freely meandering Pemliina River, Alberta, Canada; iB) aerial photograph afcunlined meandering Beaver

River, Alhert.i, Canada.

is 8-12 times the biinkfiill channel width and meander-bend

curvature Is about 2-3 times the channel width. Because

channel width (WO is related to discharge IQ). meander

wavelength (L) is also related to river diseharge

(where k ranges from 30 to 60. depending on the return period

ol"

Q), a relationship whieh has been exploited in paleo-

hydrologic studies of aneient rivers (see Dury. 1964).

Initially river scientists were preoeeupied with the periodie

character of river-nieaiider traces and only more recently have

acknowledged their non-periodie. inlermiitcnt, or random

beha\ior. In most meandering channels the orderliness of

highly periodic sinuosity is blended with, and disturbed by, a

variety of planform disorder ihat relates lo ehannel migration

processes. Kor example, regular meander-bend development

can be distorted by heterogeneities in the alluvium through

whieh bends are migrating, meander bends can migrate

laterally to forin complex meander loops whieh are mueh

larger than the associated meander bends, and high sinuosity

meander bends can erode back on themselves to form meander

cutotTs. Typical variations in the relative importance of these

two planform elements led Kellerhals ef al. (1976) to

distinguish three eategories of meandering: irregular, strongly

repeating, and tortuous.

Although the shape of channel bends in a freely migrating

meander train can be syiiimetrical and sinusoidal, even slight

river confinement eommonly leads to bend asymmetry as the

train migrates downvalley. In eases of pronounced confine-

ment (e.g., meanders formed in the confines of abandoned

glaeial meltwater channels of the Canadian Prairies), meander

asymmetry is extreme and is an indicator of flou and

migration direction (Figure M9(BK.

Channel cross-sections at or somewhat dounstream of the

axis of meander bends arc distinctly asymmetrical with deeper

flow oeeupying the outer bank /one and the deposition of a

point bar eausing shoaling at the opposite inner bank. At

points of meander infleetion flow typically is shallower over a

432 MEANDERING CHANNELS

ehannel-wide bar ealled a riffle. This "pool and riffle" sequence

is a distinctive morphological characteristic of all meandering

channels.

Flow in meandering channels

Although much debated, there is no generally aecepted

universal explanation for why meanders form in rivers (see

reviews by Callander. 1978 and Knighton, 1998). Whatever the

eause of meandering, however, the general pattern of flow

through the alternating channel bends of meanders is

well-

known and understood. In the absence of secondary flow,

bend flow seeks to conserve angular momentum so that it

tends to conform to that of

a

fi'ee vortex with high velocity at

the smaller radius of the inner bank and lower velocity al the

outer bank where radial acceleration is lower. But secondary

flow redistributes momentum in the bend to achieve a reversal

of this relationship in the zone of fully developed bend flow.

Near the water surface where velocity is highest, secondary

flow is dominated by eentrifugal "forces" and flow moves

toward the outer bank. Near the bed. where veloeity and thus

the eentrifugal effects are lowest, the balance of forces is

dominated by the inward hydraulic gradient of the super-

elevated water surface and secondary flow moves toward the

inner bank. The three-dimensional expression of

these

forces is

helical flow which has an alternating sense through successive

meander bends. One of the important consequenees of helical

flow in meanders is that .sediment eroded from the outside ofa

meander bend tends to be moved to the inner bank or point

bar of the next downstream bend.

The process of meander formation and maintenance

Meander planform geometry is controlled by the process of

lateral migration. Meandering channels erode the outer banks

of channel bends and maintain a eonstant channel width by

achieving a matching rate of deposition on the point bar

forming the inner bank. Rates of migration may be exceed-

ingly slow (a small fraction of channel width/year) or very

rapid (several channel widths/year) depending on the ratio

stream power/bank strength, and on the degree of bend

curvature (Hlekin. 1974; Hiekin and Nanson. 1975. 1984).

Depending on the particular pattern of bend erosion and

deposition,

meanders ean exhibit a variety of

evolution.

Simple

bends can increase in amplitude by extension until decreasing

bend curvature deflects or constrains the direction and rate of

motion.

Phase differences in the flow and bend alignment can

lead to bend rotation, lobing and compound meander loops.

Where confinement consti'ains meander development, bend

motion is mainly restricted to downvalley translation. These

motions are further modified by the formation of gooseneck

and chute cutoffs which short-circuit the meandering channel

path,

sometimes forming ox-bow lakes.

The deposits of meanders: meander floodplains

The nature of sediments deposited to form the floodplains of

most meandering rivers is intimately related to the sediment

available for point bar deposition and to the process of lateral

migration.

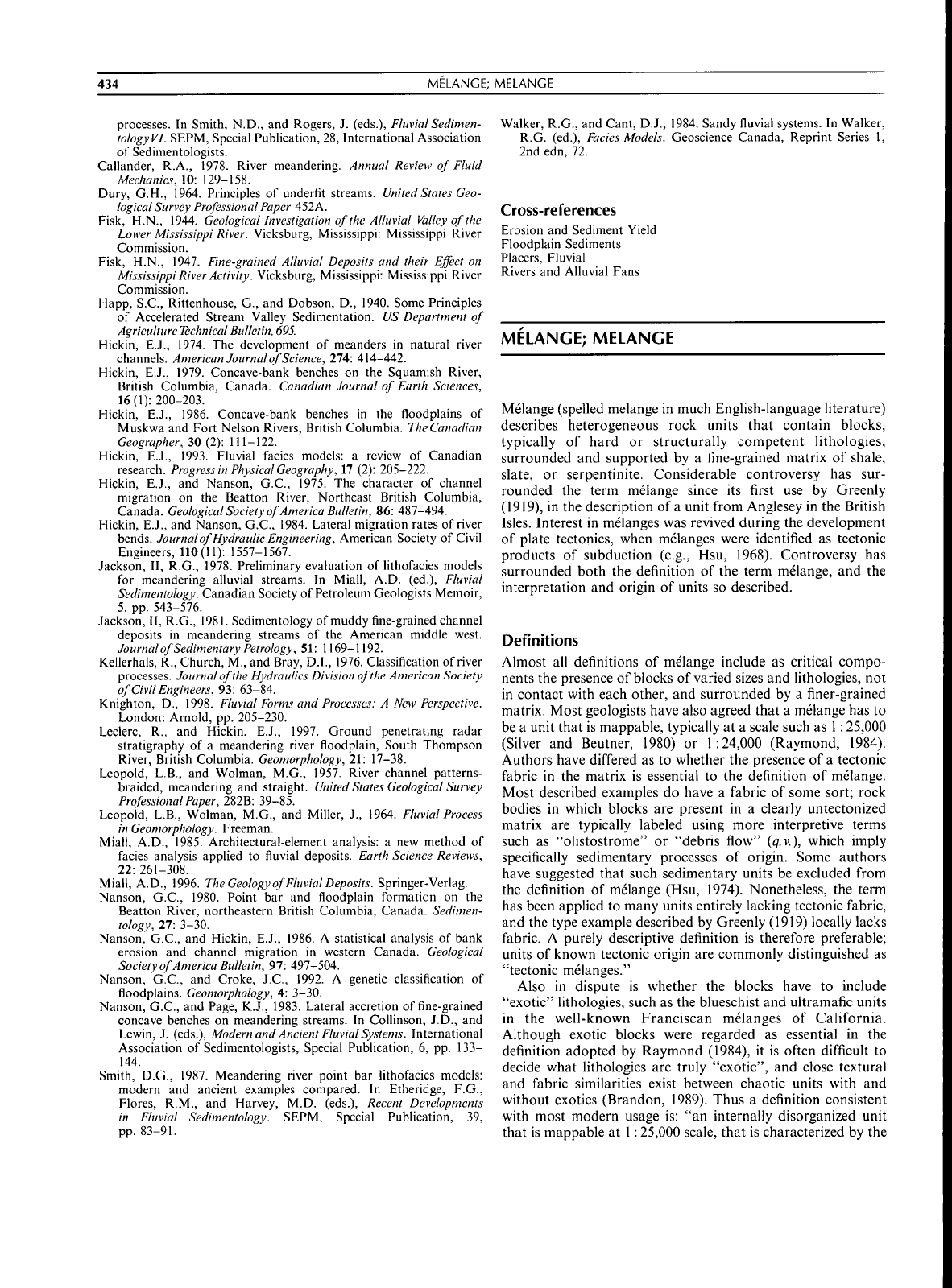

The classical point bar model of deposition in sand-

and gravel-bed rivers, originating primarily from the work of

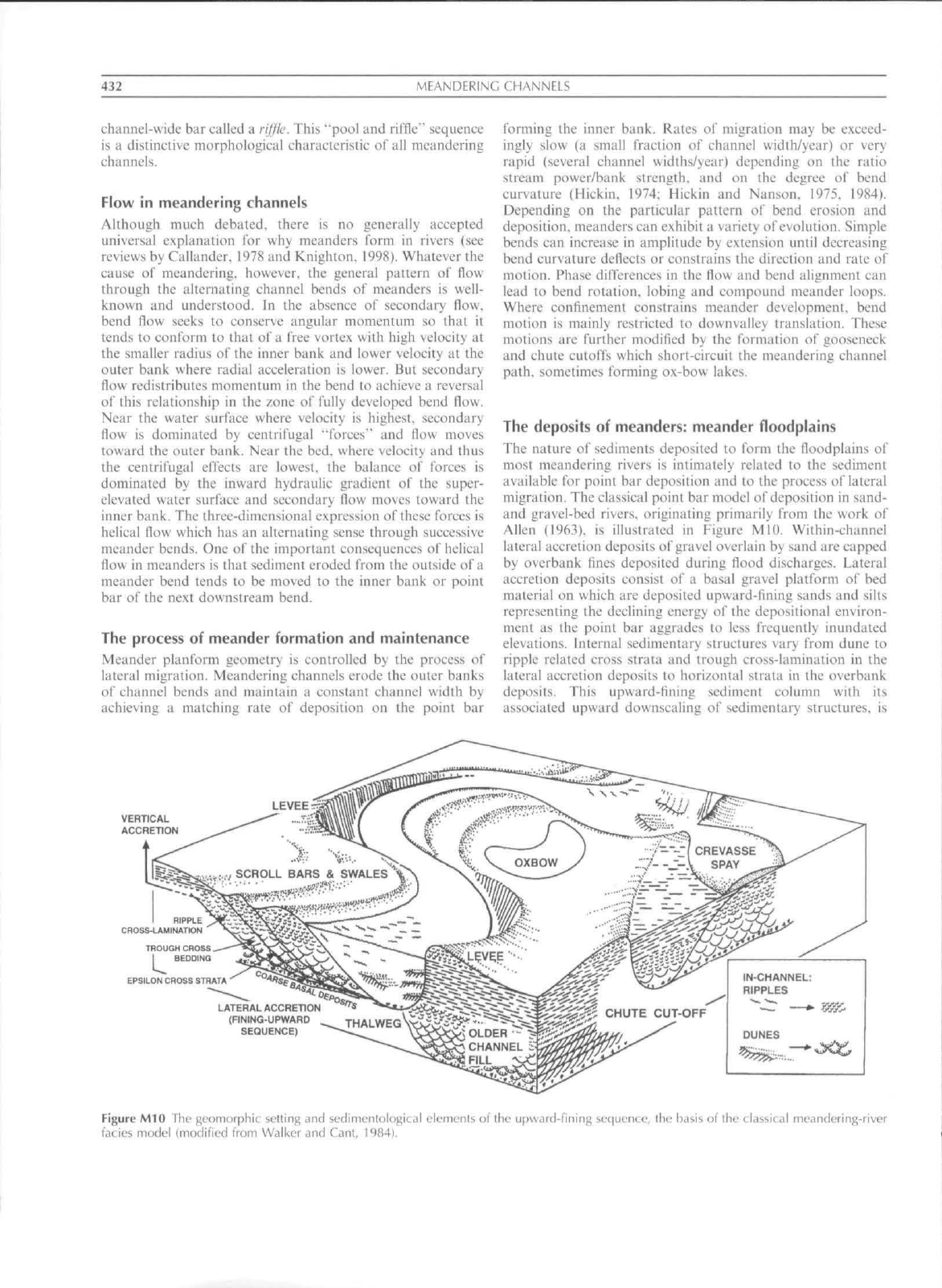

Allen (1963). is illustrated in Figure MIO. Within-ehannel

lateral accretion deposits of gravel overlain by sand arc capped

by overbank fines deposited during flood discharges. Lateral

accretion deposits consist of a basal gravel platform of bed

material on which are deposited upward-flning sands and silts

representing the declining energy of the depositional environ-

ment as the point bar aggrades to less frequently inundated

elevations. Internal sedimentary structures vary from dune to

ripple related cross strata and trough cross-lamination in the

lateral accretion deposits to horizontal strata in the overbank

deposits. This upward-lining sediment column with its

assoeiated upward downsealing of sedimentary structures, is

%::••.•

SCROLL BARS & SWALES

LATERAL ACCRETION

(FINING-UPWARD THAI WFri\v-f

^t'^??'-.

SEQUENCE) --^^r^LWEG

^J^^i^

y: QLDER

•

- ^

CHANNEL

i FILL yjC

s^-Jp CHUTE CUT-OFF

DUNES

Figure MIO The geomorphic setting and sedimentological elements ot ihe upward-fining sequence, the basis of the classical meandering-river

facies model (modified tVom Walker and Cant, 1984|.

MEANDEKINC; CHANNFIS

packaged in units bound by signioidal epsilon ceoss strata

(ECS),

corresponding to distinct phases of channel migration

and point bar deposition. These packages of sediment often

form arcuate ridges or scroll bars, separated one from the

other by troughs in the surface of the floodplain.

More recent investigations, however, have recognized many

variations on this elassieal model of meander deposition and

still others describe no{idplain sedimentology which seems to

be entirely unconventional. For example, in MialFs (1985)

models of meandering river floodplain (gravel meandering,

gravel-sand meandering, sand meandering and Jine-grained

meandering) he recognizes the important control of sediment

type on the details of floodplain sedimentology. These river

channel styles reflect a progressive increase in the abundance of

fines although coarser basal lateral accretion deposits are

common to all models. Floodplains with lateral accretion

deposits consisting of sandy silt with negligible upward fining

liave been described by Nanson (1980). Others have also noted

that meandering river floodplains formed in environments

where silt is abundant and gravel and sand are mueh less

available, particularly in low-gradient tropieal regions, also do

not appear to be adequately described by the elassical Allen

model (Jackson. 1981: Smith, 1987). Sitn'ilarly, the negligible

role played by lateral aeeretion in some steep upland valleys

formed in non-cohesive sediments, as well as in low-gradient

channels in cohesive sediments, is formalized in the genetic

classification of lloodplains by Nanson and Croke (1992).

The floodplains of meanders may also include a signilicani

proportion of counterpoint (or eddy-accretion) sediments of

horizontally bedded silt and fine sand deposited in flow

separation zones at points of abrupt direction change in the

channel. In confined meanders the abrupt angle bends that

occur where the channel impinges on (he valley wall

(Figure M9(B)) form systematically alternating zones of

flow separation downstream at the valley walls. These

alternating gyres Irap eddy accretion sediments whieh form

concave bank benches with a eurvature opposed to that of the

convexly curved scroll bars on the adjoining point bar (Hiekin.

1979.

1986; Nanson and Page. 1983; Burge and Smith. 1999).

River planform facies and architectural element

models of meander deposits

Attempts to characterize meandering river sediments in terms

of bedform-scale sedimentary struetures and assemblages

(planform tacies models) that would distinguish them with

some certainty frotn other river types (especially braided) have

not fulfilled early promise. Although general sedimentological

properties for sand/gravel-bed rivers are well represented by

these faeies models, overlap among planform groups is so

significant that their diagnostic utility is weak and olten

misleading (Jackson, 1978; Brierley and'Hickm. 1991; Hiekin,

199.V Miall, 1996). In recent years some tluvial sedimentolo-

gists have advocated the development of bar-seale or

arehitectural element-scale models to charaeterize fluvial

sediments (Miall, 1985). It has been argued that such planform

element models may be iar more effective diagnostic toots than

are bedform-scale facies models. This development represents

a return to earlier geomorphic concepts sueh as those

developed by Happ etal. (1940) and Fisk (1944, 1947) and

espoused by Leopold. Wolman and Miller (1964) who

recognized that floodplains of rivers sueh as the Mississippi

consist of an assemblage of distinct morphological and

sedimentological elements (such as channel fills, point bars.

meander scrolls, sloughs, levees, baekswamp deposits, and

crevasse splays). But such an element approach to the

depositional reeord requires three-dimensional mapping of

sueh features and the typically poor access to exposures in

the field is rarely adequate for this purpose. There is some

prospect, however, that remote sensing of the subsurfaee

architecture by means such as ground-penetrating radar

(GPR).

shallow seismic and electrical resistivity surveys, may

yield the necessary data to allow this approach to be developed

further (Alexander

(•/a/..

1994; Leclerc and Hiekin, 1997).

Summary

Meandering channels, single-thread river-ehannels consisting

of a continuous series of ehannel bends of alternating

curvature, are an important end-member in all modern

classifications of river planform and is one of the most

common river patterns found in nature.

River meanders tend to have a sinuous waveform of

eharacleristic shape (sine-generated) and a geometry that

scales with channel width so that meanders tend to be geo-

metrically sell-similar regardless ol' the size of the river. The

regularity of this sinuous pattern, also reflected in a eor-

responding "'pool and riffle" bed geometry, can be disturbed

by such effeets as tloodplain heterogeneities, meander cutotTs.

complex loop development, and ehannel confinement.

In ihe classieal point bar model of deposition in sand-bed

and gravel-bed ri\ers within-ehannel lateral accretion deposits

of gravel overlain by sand are capped by overbank fines

deposited during flood discharges. This upward-fining sedi-

ment column with its upward downsealing of sedimentary

structures, is packaged in units bound by sigmoidal epsilon

cross strata (ECS), corresponding to distinct phases of channel

migration and point bar deposition.

More recent investigations have recognized many variations

on this classical model of meander deposition, encompassing

Ihe broader range of sediments aetually found in nature,

including counterpoint deposits common in confined mean-

ders.

Mud-dominated floodplains remain poorly studied and

the subject of current researeh.

Planlbrm facies models at the bedform scale have enjoyed

limited diagnostic success. Bar-scale or architectural element-

seale models of Hoodplain sedimentology hold more promise

but require three-dimensional data dependent on remote

sensing of the stibsurface by techniques such as ground-

penetrating radar.

Edward J. Hiekin

Bibliography

Alexander. J.. Hndgc. J.S.. Leeder. M.R.. Collier. E.L., and

Gawthorpc. R.L.. 1994, Holocene meander boll cvolulion in an

active extensional basin, southwestern Montana.

Jtiia-iial

"I

.Si'tti-

nieniarv

Re.search.

B64! 542-559.

Allen, J.R.I.., [963. The elassilication of cross-siratified units, wilh

nolL's on their origin.

Svilii>ieiitolagy.

2: ')3 114.

Brierley. G.J.. and Hiekin. E.J., 1991, Channel planlbrm as a non-

con

I

rolling faetor in tiiivial scdimonuilogv: the case of the

Squiunish River Hoodplain, British Columhia. Seiliiiientarv Gi'ul-

<'}•):

75:

67-83.

Burge, L.M., and Smith. D.G.. 1999. Confined meandering river eddy

accretions: sedinieniology. ehiiniiel geomeirv. and depositional

434

MELANGE; MELANGE

processes.

In

Smith, N.D.,

and

Rogers,

J.

(eds.), Fluvial Sedimen-

tologyVI.

SEPM, Special Publication, 28, International Association

of Sedimentologists.

Callander,

R.A., 1978.

River meandering. Annual Review

of

Fluid

Meehanies,

10:

129-158.

Dury,

G.H., 1964.

Principles

of

underfit streams. United States Geo-

logieal Survey Professional

Paper

452A.

Fisk,

H.N., 1944.

Geological Investigation

of

the

Alluvial

Valley

of

the

Lower Mississippi River. Vicksburg, Mississippi: Mississippi River

Commission.

Fisk,

H.N., 1947.

Fine-grained Alluvial Deposits

and

their Effeet

on

Mississippi River Aetivity. Vicksburg, Mississippi: Mississippi River

Commission.

Happ,

S.C,

Rittenhouse,

G., and

Dobson,

D.,

1940. Some Principles

of Accelerated Stream Valley Sedimentation.

US

Department

of

Agrieulture

Teelmieal

Bulletin,

695.

Hiekin,

E.J., 1974. The

development

of

meanders

in

natural river

channels. American Journal of Seienee, 274: 414-442.

Hiekin,

E.J., 1979.

Concave-bank benches

on the

Squamish River,

British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal

of

Earth Sciences,

16(1):

200-203.

Hiekin,

E.J., 1986.

Concave-bank benches

in the

floodplains

of

Muskwa

and

Fort Nelson Rivers, British Columbia. The Canadian

Geographer,

30

(2): 111-122.

Hiekin,

E.J., 1993.

Fluvial facies models:

a

review

of

Canadian

research.

Progress in

Physical

Geography,

17

(2): 205-222.

Hiekin,

E.J., and

Nanson,

G.C., 1975. The

character

of

channel

migration

on the

Beatton River, Northeast British Columbia,

Canada.

Geological

Soeiety of America Bulletin,

86:

487-494.

Hiekin, E.J.,

and

Nanson, G.C., 1984. Lateral migration rates

of

river

bends.

Journalof Hydraulie Engineering, American Society

of

Civil

Engineers, 110(11): 1557-1567.

Jackson,

II, R.G.,

1978. Preliminary evaluation

of

lithofacies models

for meandering alluvial streams.

In

Miall,

A.D.

(ed.). Fluvial

Sedimentology. Canadian Society

of

Petroleum Geologists Memoir,

5,

pp.

543-576.

Jackson,

II,

R.G., 1981. Sedimentology

of

muddy fine-grained channel

deposits

in

meandering streams

of the

American middle west.

Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology,

51: 1169-1192.

Kellerhals,

R.,

Church, M.,

and

Bray, D.I., 1976. Classification

of

river

processes. Journalof the

HydrauUes

Division of the American Soeiety

of

Civil

Engineers, 93: 63-84.

Knighton,

D., 1998.

Fluvial Forms

and

Proeesses:

A

New Perspective.

London: Arnold,

pp.

205-230.

Leelerc,

R., and

Hiekin,

E.J., 1997.

Ground penetrating radar

stratigraphy

of a

meandering river floodplain. South Thompson

River, British Columbia. Geomorphology, 21: 17-38.

Leopold,

L.B., and

Wolman,

M.G., 1957.

River ehannel patterns-

braided, meandering

and

straight. United States Geologieal Survey

Professional

Paper,

282B: 39-85.

Leopold,

L.B.,

Wolman,

M.G., and

Miller,

J., 1964.

Fluvial Proeess

in Geomorphology. Freeman.

Miall,

A.D.,

1985. Architectural-element analysis:

a new

method

of

facies analysis applied

to

fluvial deposits. Earth Scienee Reviews,

22:

261-308.

Miall, A.D., 1996. The

Geology

of Fluvial Deposits. Springer-Verlag.

Nanson,

G.C., 1980.

Point

bar and

floodplain formation

on the

Beatton River, northeastern British Columbia, Canada. Sedimen-

tology,

27: 3-30.

Nanson,

G.C., and

Hiekin,

E.J.,

1986.

A

statistical analysis

of

bank

erosion

and

channel migration

in

western Canada. Geological

Soeiety of Ameriea Bulletin,

97:

497-504.

Nanson,

G.C., and

Croke,

J.C, 1992. A

genetic classification

of

floodplains. Geomorphology,

4: 3-30.

Nanson, G.C.,

and

Page,

K.J.,

1983. Lateral accretion

of

flne-grained

concave benches

on

meandering streams.

In

Collinson,

J.D., and

Lewin,

J.

(eds.). Modern and Aneient Fluvial Systems. International

Association

of

Sedimentologists, Special Publication,

6, pp. 133-

144.

Smith,

D.G., 1987.

Meandering river point

bar

lithofacies models:

modern

and

ancient examples compared.

In

Etheridge,

F.G.,

Flores,

R.M., and

Harvey,

M.D.

(eds.), Reeent Developments

in Fluvial Sedimentology. SEPM, Special Publication,

39,

pp.

83-91.

Walker, R.G.,

and

Cant, D.J., 1984. Sandy fluvial systems.

In

Walker,

R.G. (ed.), Faeies Models. Geoscience Canada, Reprint Series

1,

2nd edn,

72.

Cross-references

Erosion

and

Sediment Yield

Floodplain Sediments

Placers, Fluvial

Rivers

and

Alluvial Fans

MELANGE; MELANGE

Melange (spelled melange in much English-language literature)

describes heterogeneous rock units that contain blocks,

typically of hard or structurally competent lithologies,

surrounded and supported by a fine-grained matrix of shale,

slate, or serpentinite. Considerable controversy has sur-

rounded the term melange since its first use by Greenly

(1919), in the description ofa unit from Anglesey in the British

Isles.

Interest in meianges was revived during the development

of plate tectonics, when melanges were identified as tectonic

products of subduction (e.g., Hsu, 1968). Controversy has

surrounded both the definition of the term melange, and the

interpretation and origin of units so described.

Definitions

Almost all definitions of melange include as critical compo-

nents the presence of blocks of varied sizes and lithologies, not

in contact with each other, and surrounded by a finer-grained

matrix. Most geologists have also agreed that a melange has to

be a unit that is mappable, typically at a scale such as

1:25,000

(Silver and Beutner, 1980) or

1:24,000

(Raymond, 1984).

Authors have differed as to whether the presence of a tectonic

fabric in the matrix is essential to the definition of melange.

Most described examples do have a fabric of some sort; rock

bodies in which blocks are present in a clearly untectonized

matrix are typically labeled using more interpretive terms

such as "olistostrome" or "debris flow"

{q.v.),

which imply

specifically sedimentary processes of origin. Some authors

have suggested that such sedimentary units be excluded from

the definition of melange (Hsu, 1974). Nonetheless, the term

has been applied to many units entirely lacking tectonic fabric,

and the type example described by Greenly (1919) locally lacks

fabric. A purely descriptive definition is therefore preferable;

units of known tectonic origin are commonly distinguished as

"tectonic melanges."

Also in dispute is whether the blocks have to include

"exotic" lithologies, such as the blueschist and ultramafic units

in the well-known Franciscan melanges of California.

Although exotic blocks were regarded as essential in the

definition adopted by Raymond (1984), it is often difficult to

decide what lithologies are truly "exotic", and close textural

and fabric similarities exist between chaotic units with and

without exotics (Brandon, 1989). Thus a definition consistent

with most modern usage is: "an internally disorganized unit

that is mappable at

1:25,000

scale, that is characterized by the