Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MUDROCKS 455

cross-lamination provides useful insights to the paleocurrent

pattern of ancient shaly basins, which ean also be estimated

from oriented wood, graptolites, ostracodes, and some

elongate foraminifers. It is always good to remember that

bottotn currents exist in both oxygenated and poorly

oxygenated basins, although in mudroeks. thin sections, and

polished sections may be needed to sec micro cross-lamination

and flutes best. Current systems in ancient muddy basins have

also,

in a few instances, been inferred from their pattern of silt

deposition (Jones and Blatt, 1984),

In sum, little is more important in the study of mudroeks

than their sedimentary structures, especially when combined

with examination of body and trace fossils. Sedimentary

structures help us identify types of bottom currents such as

distal turbidity currents, contour currents or hemipelagic rains

of fine terrigenous debris. Relatitig abrupt vertical changes in

the sequence of structures in a mudrock with the presenee of

weak discontinuities, changes in fossil assemblages, pyrite, or

phosphate, clay content and color is the basis for recognizing

the basin-center equivalents of major stratigraphie breaks that

are eommon along basin margins.

Oxygen

The presence or absence of dissolved oxygen in bottom waters

and in the first lew decimeters of muddy bottoms is all

important for the color, degree of bioturbation and abundance

of oxygen sensitive minerals such as pyrite and siderite and

organic matter (kerogen). The concept of stratification of the

water colutnn is needed here. The water of a lake or sea is

described as

.\iralificil.

uhen not uniformly mixed. This may be

the result ol' temperature, density, or oxygen differences.

Mudroeks are the best indicators of stratification of the water

column in ancient basins.

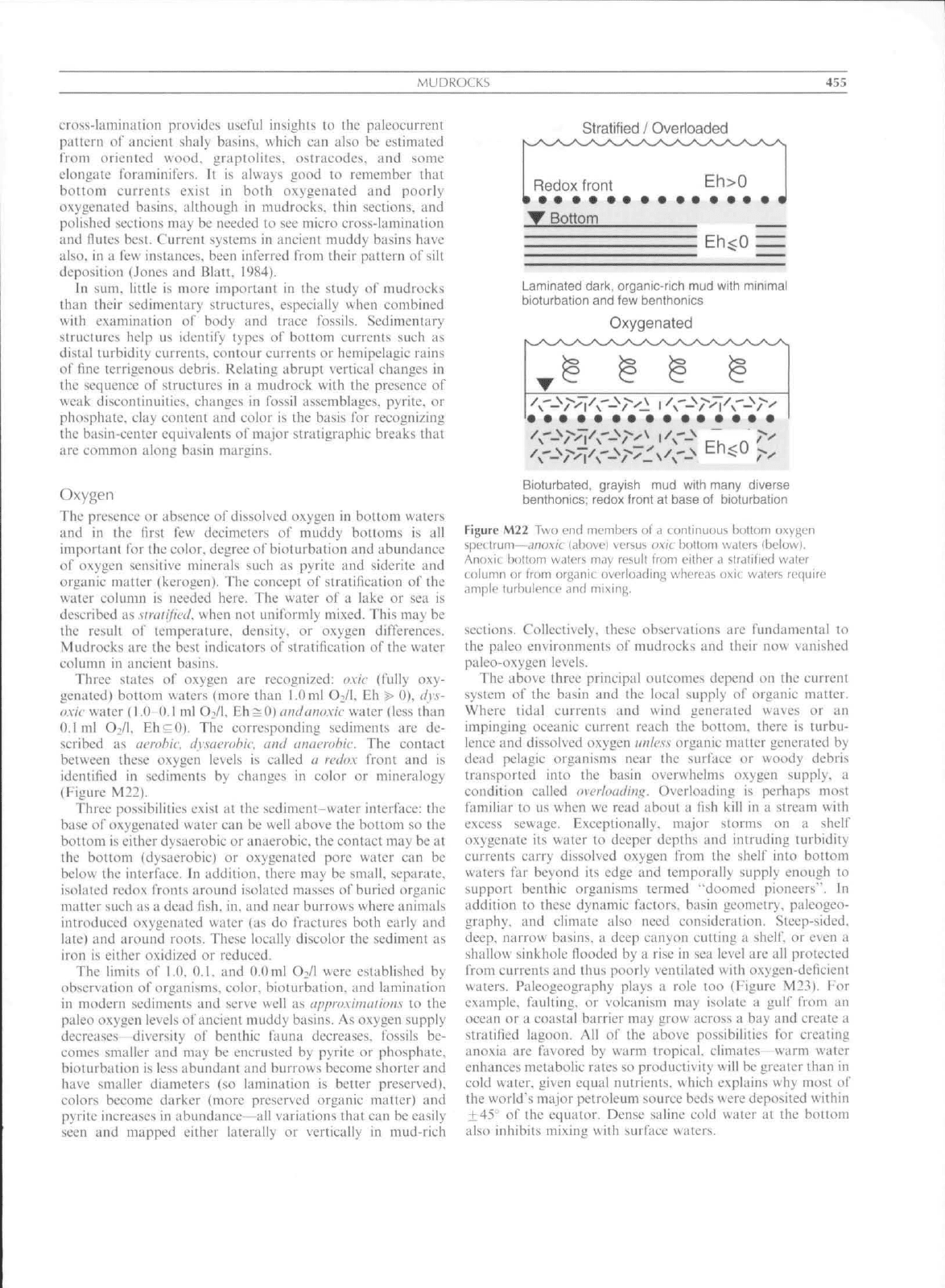

Three states of oxygen are recognized: oxic (fully oxy-

genated) bottom waters (more than 1.0 ml Oi/I. Eh

t>

0), </v,v-

oxic water (1.0-0.1 ml O^/l. Eh^O) amiauoxic water (less than

0,1 tnl O2/I. Eh^O). The eorresponding sediments are de-

scribed as aerobic, tlysacrohic. ami anaerobic. The contact

betueen these oxygen levels is called a rvdox front and is

identified in sediments by changes in color or mineralogy

(Figure M22).

Three possibilities exist at the scdimcnt-water interface: the

base of oxygenated water can be well above the bottom so the

bottom is either dysaerobic or anaerobic, the contact may be at

the bottom (dysaerobic) or oxygenated pore water can be

below the interface. In addition, there may be small, separate,

isolated redox fronts around isolated masses of buried organie

tnatter such as a dead fish, in. and near burrows where animals

introduced oxygenated water (as do fractures both early and

late) and around roots. These locally discolor the sediment as

iron is either oxidized or reduced.

The limits of 1.0. 0,1. and 0.0 ml OVl were established by

observation of organisms, color, bioturbation. and lamination

in modern sediments and serve well as approxiiuaiion.s lo the

paleo oxygen levels of ancient muddy basins. As oxygen supply

decreases diversity o\' benthic faunit decreases, fossils be-

comes smaller and may be enerusted by pyrite tir phosphate,

bioturbation is less abundant and burrows beeome shorter and

have smaller diameters (so lamination is better preserved),

colors become darker (more preserved organic matter) and

pyrite increases in abundance—all variations that ean be easily

seen and mitpped either laterally or vertically in mud-rich

Stratified / Overloaded

Redox front

Eh>0

Bottom

Eh<0

Laminated dark, organic-rich mud with minimal

bioturbation and few benthonics

Oxygenated

Bioturbated, grayisb mud with many diverse

benthonics; redox front at base of bioturbation

Figure M22 Two end members of a continuous bottom oxygen

spt'( trum—cinoxic (abovei versus oxic bottom waters (below].

Anoxic bnltom waters may result Irom either

,1

stratified water

column or from organic overbading whereas oxic waters require

ample turbulence and

seetions. Collectively, these observations are fundamental to

the paleo environtnents of mitdrocks and iheir now vanished

paleo-oxygen levels.

The above three principal outcomes depend on the current

system of the basin and the local supply of organic matter.

Where tidal currents and wind generated waves or an

impinging oceanic current reach the bottom, there is turbu-

lence and dissolved oxygen

unlcs.s

organic matter generated by

dead pelagic organisms near the surface or woody debris

transported into the basin overwhelms oxygen supply, a

condition ealled tivcrhnuiini^. Overloading is perhaps most

familiar to us when we read about a lish kill in a stream with

excess sewage. Exceptionally, major storms on a shelf

oxygenate its water to deeper depths and intruding turbidity

currents carry dissolved oxygen from the shelf into bottom

waters far beyond its edge and temporiilly supply enough to

support benthic organisms termed "doomed pioneers". In

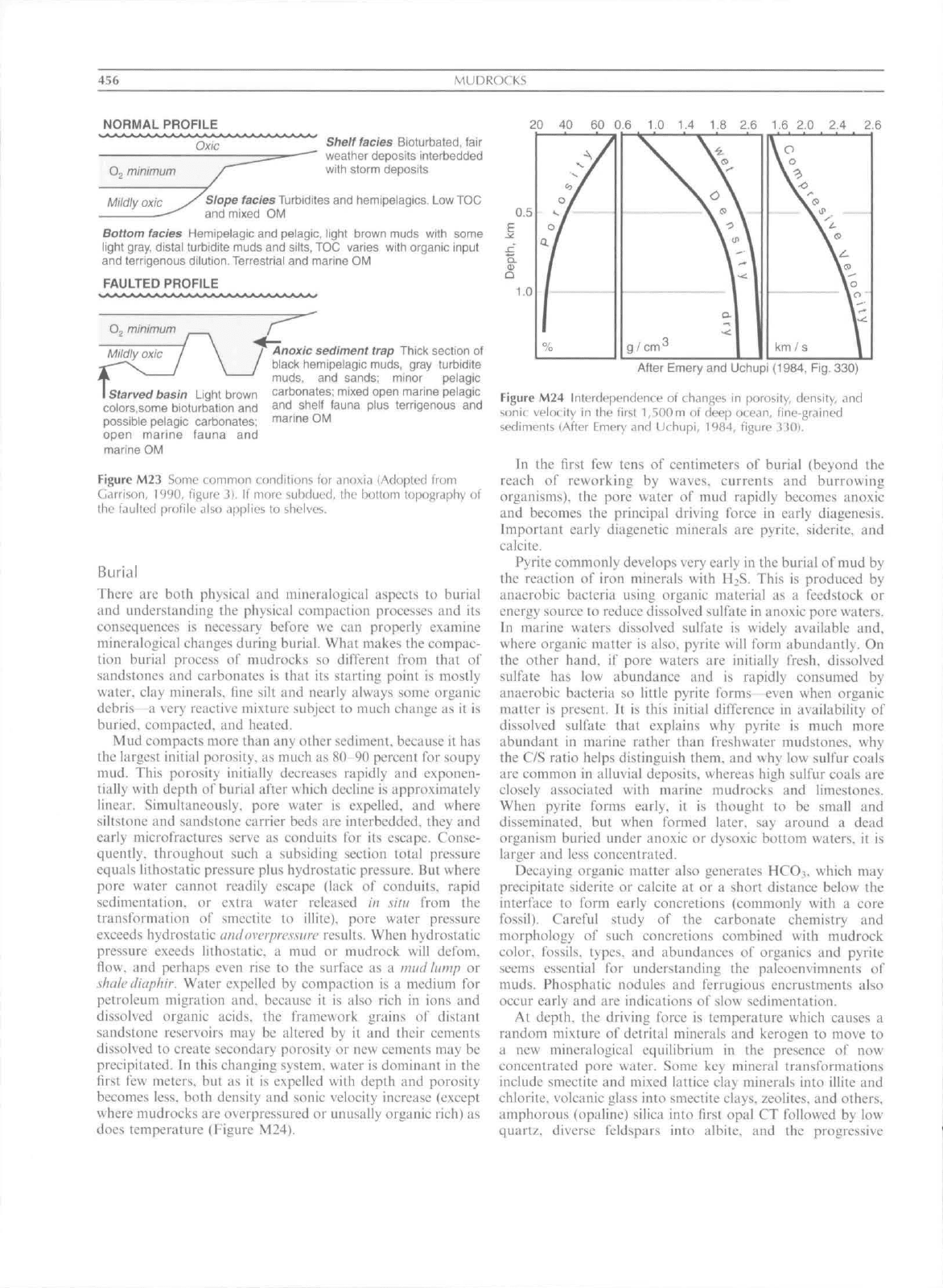

addition to these dynatnic factors, basin geometry, paleogeo-

graphy, and climate also need consideration. Steep-sided,

deep,

narrow basins, a deep canyon cutting a

shelf,

or even a

shallow sinkhole flooded by a rise in sea level are all protected

from currents and thus poorly ventilated with oxygen-deficient

waters. Paleogeography plays a role too (Figure M23), For

example, faulting, or voleanism may isolate a guif from an

ocean or a coastal barrier may grow across a bay and create a

stratified lagoon. All o\ the above possibilities for creating

anoxia are favored by warm tropical, climates warm water

enhances metabolic rates so produetivity will be greater than in

cold water, given equal nutrients, which explains v\hy most o\'

the world's major petroleum source beds were deposited within

+

45"

of the equator. Dense saline cold water at the bottom

also inhibits mixing with surface waters.

456

MUDROCKS

NORMAL PROFILE

Oxic

20 40 60 0.6 1.0 1.4 1 2.6 1.6 2-0 2.4 2.6

O,

minimum

Shelf facies

Bioturbated. fair

weather deposits interbedded

with storm deposits

Mildly oxic

y^

Slope facies

Turbidites and hemipeiagics. Low TOC

— and mixed OM

Bottom facies

Hemipelagic and pelagic, light brown muds with some

light gray, distal turijidite muds and silts, TOC varies with organic input

and terrigenous

dilution.

Terrestrial and marine OM

FAULTED PROFILE

O,

minimum

I

Starved basin

Light brown

colors.some bioturbation and

possible pelagic carbonates;

open marine fauna and

marine OM

Anoxic sediment trap

Thick section of

black hemipeiagic muds, gray turbidite

muds,

and sands; minor peiagic

carbonates; mixed open marine pelagic

and shelf fauna plus terrigenous and

marine OM

Figure M23 Some common conditions for anoxia (Adopted from

Cirrison,

1990, figure 3). If more subtlued, the bottom topography of

the faulted profile also applies to shelves.

Burial

There arc both physical and mineralogical aspects to burial

and understanding the physical compaction proccs.ses and its

consequences is necessary bclbrc we can properly examine

mineralogical changes during burial. What makes the compac-

tion burial process of mudrocks so different from that of

sandstones and carbonates is that its starting point is mostly

water, elay minerals, tine silt and nearly always some organic

debris—a very reactive mixture subject to much change as it is

buried, compacted, and heated.

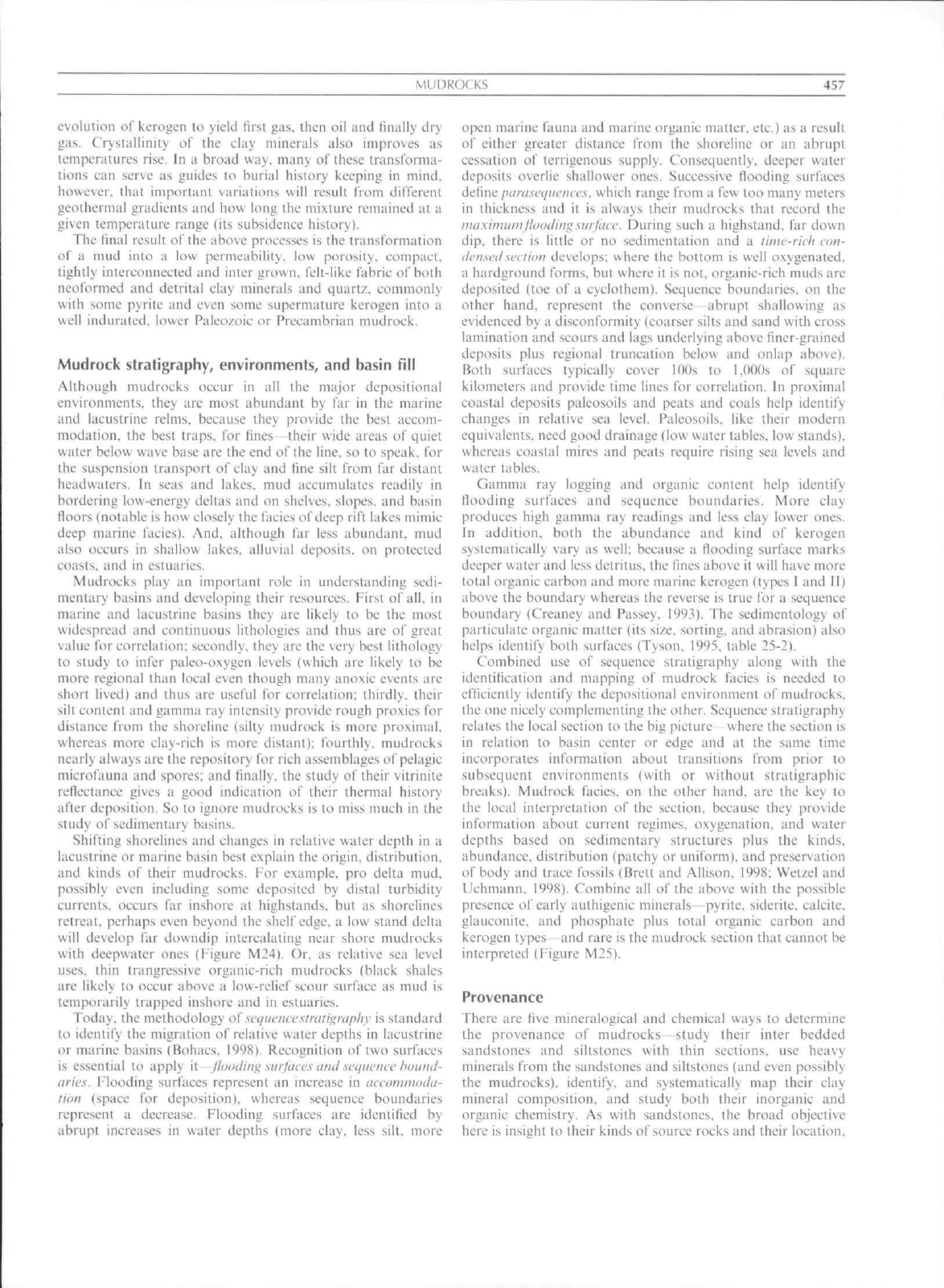

Mud compacts tnore than any other sediment, because it has

the largest initial porosity, as much as 80 90 percent t^or soupy

mud. This porosity initially deereases rapidly and exponen-

tially with depth of burial after which decline is approximately

linear. Simultaneously, pore water is expelled, and where

siltsione and sandstone carrier beds are interbedded, they and

early micro fractures serve as conduits for its escape. Conse-

quently, throughout such a subsiding section total pressure

equals lithostatic pressure plus hydrostatic pressure. But where

pore water cannot readily escape (lack of conduits, rapid

sedimentation, or extra water released In silii from the

transformation of smeetite to illite), pore water pressure

exceeds hydrostatic anilovcrprcssiin' results. When hydrostatic

pressure exeeds lithostatic a mud or mudrock will defom.

flow, and perhaps even rise to the surfaee as a mud lump or

shale diaphir. Water expelled by compaetion is a medium for

petroleum migration and. beeause it is also rich in ions and

dissolved organie acids, the framework grains of distant

sandstone reservoirs may be altered by it and their cements

dissolved to create seeondary porosity or new cements may be

precipitated. In this changing system, walei" is dominant in the

first few meters, but as it is expelled with depth and porosity

becomes less, both density and sonic velocity increase {except

where mudroeks are overpressured or unusaliy organic rich) as

does temperature (Figure M24).

0.5

1.0

o /

g/cm^

1 1

Vo

km/s 1

After Emery and Uehupi (1984, Fig. 330)

Figure M24 Interdependence of changes in porosity, density, and

sonit. velocity in the first l,5()0m of deep ocean, fine-grained

sediments (After Emery and Uthupi, 1984. figure .330).

In the first few tens of centimeters of burial (beyond the

reaeh of reworking by waves, currents and burrowing

organisms), the pore water of mud rapidly becomes anoxic

and becomes the principal driving force in early diagenesis.

Important early diagenetic minerals are pyrite, siderite, and

calcite.

Pyrite commonly develops very early in the burial of mud by

the reaction of iron minerals with H2S. This is produced by

anaerobie bacteria using organic material as a feedstock or

energy source to reduce dissolved sulfate in anoxic pore waters.

In marine waters dissolved sulfate is widely available and.

where organie matter is also, pyrite will form abundantly. On

the other hand, if pore waters are initially tVesh. dissolved

sulfate has low abundance and is rapidly consumed by

anaerobic bacteria so little pyrite forms even when organic

matter is present. It is this initial difference in availability of

dissolved sulfate that explains why pyrite is much more

abundant in marine rather than freshwater mudstones, why

the C/S ratio helps distinguish them, and why low sulfur eoals

are common in alluvial deposits, whereas high sulfur coals are

closely associated with marine mudrocks and limestones.

When pyrite forms early, it is thought to be small and

disseminated, but when formed later, say around a dead

organism buried under anoxic or dysoxic bottom waters, it is

larger and less concentrated.

Decaying organic matter also generates HCO3, which may

precipitate siderite or calcite at or a short distance below the

interface to form early eoncretions (commonly with a core

fossil).

Careful study of the earbonate chemistry and

morphology of such eoncretions combined with mudrock

color, fossils, types, and abundances of organics and pyrite

seems essential for understanding the palcoenvimnents of

muds.

Phosphatie nodules and ferrugious encrustments also

oeeur early and are indications of slow sedimentation.

Af depth, the driving force is temperature which causes a

random mixture of detrital minerals and kcrogen to move to

a new mineralogical equilibrium in the presenee of now

concentrated pore water. Some key mineral transformations

include smectite and mixed lattiee clay minerals into illite and

chlorite, volcanic glass into smeetite elays. zeolites, and others,

amphorous (opaline) silica into first opal CT followed by low

quartz, diverse feldspars into albite. and the progressive

MUDROCKS

457

evolution of kerogen to yield first gas. then oil and finally dry

gas.

Crystallinily of the clay minerals also improves as

temperatures rise. In a broad way. many of these transforma-

tions can serve as guides to burial history keeping in

mind,

however, that important variations will result iVom dilTcrcnt

geolhermal gradients and how long the mixture remained at a

gi\en temperature range (its subsidence history).

The final result of the above processes is the transformation

oi a mud into a low permeability, low porosity, compact.

tightl> interconnected and inter grown, felt-like fabric of both

neoformed and detrital clay minerals and quartz, commonly

with some pyrite and even some supermature kerogen into a

uell indurated, lower Paleozoic or PreeanibrJan mudrock.

Mudrock

stratigraphy,

environments,

and

basin fill

Although mudrocks occur in all the major depositional

environments, they are most abundant by far in the marine

and lacustrine reims, because they provide the best accom-

modaiion,

the best traps, for fines—their wide areas of quiet

uater below wave base are the end of the line, so to speak, for

the suspension transport of elay and fine silt from far distant

headwaters. In seas and lakes, mud accumulates readily in

bordering low-energy deltas and on shelves, slopes, and basin

floors (notable is how closely the facies of

deep

rift lakes mimic

deep marine facies). And. although far less abundant, mud

also occurs in shallow lakes, alluvial deposits, on protected

coasts,

and in estuaries.

Mudrocks play an important role in understanding

sedi-

mentary basins and developing their resourees. First of all. in

marine and laeustrine basins they are likely to be the most

widespread and continuous lilhologies and thus are of great

value for correlation: secondly, they are the very best tithology

to sUidy lo infer paleo-oxygen levels (which are likely to be

more regional than local even though many anoxic events are

short lived) and thus are useful for correlation: thirdly, their

silt content and gamma ray intensity provide rough proxies for

distance from the shoreline (silty mudroek is more proximal.

uhereas more elay-rieh is more distant): fourthly, mudrocks

nearly always are the repository for rich assemblages of pelagic

mierofauna and spores: and finally, the study of their vitrinite

reflectance gives a good indication of their thermal history

after deposition. So lo ignore mudroeks is to miss much in the

study of sedimentary basins.

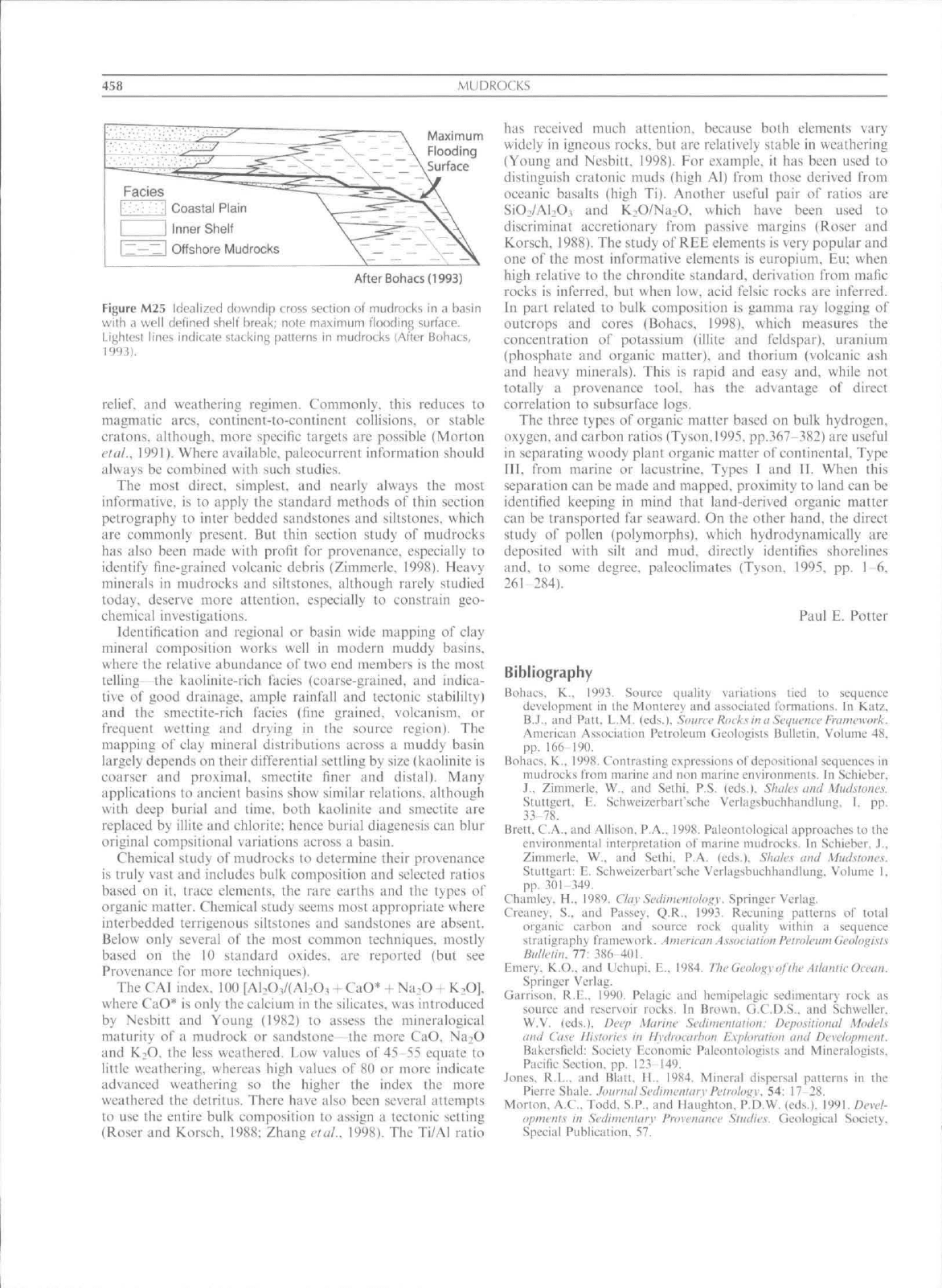

Shifting shorelines and changes in relative water depth in a

laeustrine or marine basin best explain the origin, distribution,

and kinds ol' their mudrocks. For example, pro delta mud.

possibly even including some deposited by distal turbidity

currents, occurs far inshore at highstands. but as shorelines

retreat, perhaps even beyond Ihe shelf edge, a low stand delta

will develop far downdip intercalating near shore mudrocks

with deepwater ones {Figure M24). Or. as relative sea level

uses,

thin trangressive organic-rich mudrocks (black shales

are likely to oeeur above a low-relief scour surfaee as mud is

temporarily trapped inshore and in estuaries.

Today, the methodology o{seiiiicnccsu-ali^raphy is standard

to identify the migration of relative water depths in lacustrine

or marine basins (Bohacs. 1998). Recognition of two surfaces

is essential to apply it

jlondiuf^

siirfdce.s

uial seiiiicncc houiul-

aric.s. Flooding surfaces represent an increase in

accoinnuHUi-

lioii (space for deposition), whereas sequenee boundaries

represent a decrease. Flooding surfaces are identified by

abrupt inereases in water depths (more clay, less silt, more

open marine fauna and marine organic matter, etc.) as a result

of either greater distance from the shoreline or an abrupt

cessation of terrigenous supply. Consequently, deeper water

deposits overlie shallower ones. Successive flooding surfaces

dcf\nc piiruscijiu'iiccs. which range from a few too many meters

in thickness and it is always their mudroeks that record the

maxinuimthxHliitg.surface. During such a highstand, far down

dip.

there is little or no sedimentation and a rinw-ricli ain-

ik'nsed section

develops; where the bottom is well oxygenated,

a hardground forms, bul where il is not, organic-rich muds are

deposited (toe of a cyclothem). Sequence boundaries, on the

other

hand,

represent the converse abrupt shallowing as

e\idenced by a disconformity (coarser silts and sand with cross

lammation and scours and lags underlying above finer-grained

deposits plus regional truncation below and onlap above).

Both surfaces typically cover

I OOs

to

I .UUOs

o'i square

kilometers and provide time lines for correlation. In proximal

coastal deposits paleosoils and peats and coals help identify

changes in relative sea

level.

Paieosoils, like their modem

equivalents, need good drainage (tow water tables, low stands),

whereas eoastal mires and peats require rising sea levels and

water tables.

Gamma ray logging and organie content help identify

Hooding surfaces and sequence boundaries. More clay

produces high gamma ray readings and less clay lower ones.

In addition, both the abundance and kind of kerogen

systematically vary as

well:

because a fiooding surface marks

deeper water and less detritus, the fines above it will have more

total organie carbon and more marine kerogen (types

1

and II)

above the boundary whereas the reverse is true for a sequence

boundary (Creaney and Passey. 199.'^). The sedimenlology of

particulate organic matter (its size, sorting, and abrasion) also

helps identify both surfaces (Tyson. 1995, table 25-2).

Combined use of sequence stratigraphy along with the

identification and mapping of mudroek facies is needed to

efficiently identify the depositional environment of mudrocks,

the one nicely complementing the other. Sequence stratigraphy

relates the local section to the big picture where the section is

in relation to basin center or edge and at the same time

incorporates information about transitions from piior to

subsequent environments (with or without stratigraphic

breaks). Mudrock facies. on the other

hand,

are the key to

the local interpretation of the section, because they provide

information about current regimes, oxygenation, and water

depths based on sedimentary struetures plus the kinds,

abundance, distribution (patchy or uniform), and preservation

of body and trace fossils (Brett and Allison. 1998; Wetzel and

Uchmann.

199S). Combine all

o\~

ihe above with the possible

presence of early authigenic minerals pyrite. siderite. caleite.

glauconite. and phosphate plus total organie carbon and

kerogen types and rare is the mudroek section that cannot be

interpreted (Figure M25).

Provenance

There are live mineralogical and chemical ways to determine

the provenance of mudrocks—study their inter bedded

sandstones and siltstones with thin sections, use heavy

minerals from ihe sandstones and sillstones (and even possibly

the mudrocks), identify, and systematically map their clay

mineral composition, and .study both their inorganic and

organic chemistry. As with sandstones, the broad objective

here is insitzht to their kinds of source rocks and their location.

458

MLiDKOCKS

Maximum

_ Flooding

— -\ Surface

Facies

' Coastal Plain

Inner Shelf

Z—~ I Offshore Mudrocks

After Bohacs (1993)

Figure M25 Idealized downdip truss section of mudrocks in <i basin

with a well defined shelf break; nole maximum flooding surface.

Lighlest lines indicate stacking patterns in mudrocks (After Bohacs,

1993).

relief,

and weathering regimen. Commonly, this reduces to

magmatic arcs, continent-to-continent collisions, or stable

cratons. although, more specific targets are possible (Morton

elal.. 1991). Where available, paleocurrent information should

always be combined with such studies.

The most direct, simplest, and nearly always the most

informative, is to apply the standard methods of thin section

petrography to inter bedded sandstones and siltstones. which

are commonly present. But thin section study of mudrocks

has also been made with profit for provenance, especially to

identify fine-grained volcanic debris (Zimmerle. 1998). Heavy

minerals in mudrocks and siltstones. although rarely studied

today, deserve more attention, espeeially to constrain geo-

chemical investigations.

Identification and regional or basin wide mapping of elay

mineral composition works well in modern muddy basins,

where the relative abundance of two end members is the most

telling—the kaolinite-rich facies (coarse-grained, and indica-

tive of good drainage, ample rainfall and tectonic stabililty)

and the smectite-rich facies (fine grained, volcanism. or

frequent wetting and drying in the source region). The

mapping of clay mineral distributions across a muddy basin

largely depends on their differential settling by size (kaolinite is

coarser and proximal, smectite finer and distal). Many

applications to ancient basins show similar relations, although

with deep burial and time, both kaolinite and smectite are

replaced by illite and chlorite: hence burial diagenesis can blur

original eompsitional variations across a basin.

Chemical study of mudrocks to determine their provenance

is truly vast and includes bulk composition and selected ratios

based on it. trace elements, the rare earths and the types of

organie matter. Chemical study seems most appropriate where

interbedded terrigenous siltstones and sandstones are absent.

Below only several of the most common techniques, mostly

based on the 10 standard oxides, are reported (but see

Provenance for more techniques).

The CAI index, 100 [AI:OV(A1.O, + CaO* + Na.O + K^OJ.

where CaO* is only the calcium in the silicates, was introduced

by Nesbitt and Young (1982) to assess the mineralogical

maturity of a mudrock or sandstone the more CaO. Na2O

and K^O. the less weathered. Low values of 45 55 equate to

little weathering, whereas high values of 80 or more indicate

advanced weathering so the higher the index the more

weathered the detritus. There have also been several attempts

to use the entire bulk composition to assign a tectonic setting

(Roser and Korsch. 1988; Zhang elal.. 1998). The Ti/AI ratio

has received much attention, because both elements vary

widely in igneous rocks, but are relatively stable in weathering

(Young and Nesbitt. 1998). For example, it has been used to

distinguish eratonic muds (high Al) from those derived from

oceanic basalts (high Ti). Another useful pair of ratios are

SiO./AI.O, and K.O/Na.O. which have been used to

discriminal accretionary from passive margins (Roser and

Korsch, 1988). The study of REE elements is very popular and

one of the most informative elements is europium, Eu; when

high relative to the ehrondite standard, derivation from mafie

rocks is inferred, but when low, acid felsic rocks arc inferred.

In part related to bulk composition is gamma ray logging of

outcrops and cores (Bohacs, 1998). which measures the

concentration of potassium (illite and feldspar), uranium

(phosphate and organic matter), and thorium (volcanic ash

and heavy minerals). This is rapid and easy and, while not

totally a provenance tool, has the advantage of direet

correlation to subsurface logs.

The three types of organic matter based on bulk hydrogen,

oxygen, and carbon ratios (Tyson,1995. pp.367-382) are useful

in separafing woody plant organic matter of continental. Type

III,

from marine or lacustrine. Types I and II. When this

separation can be made and mapped, proximity to land can be

identified keeping in mind that land-derived organic matter

can be transported far seaward. On the other hand, the direct

study of pollen (polymorphs). which hydrodynamically are

deposited with silt and mud. directly identifies shorelines

and, to some degree, paleoclimates (Tyson, 1995, pp. i 6,

261 284).

Paul E. Potter

Bibliography

Boliiics. K., \9'-)y. Source qiialiiy variations lied lo suqucnue

dcvclopmunl in ihc Monieri;y and asiocialcd tormalions. In K;Uz.

B.J.. and Pat!. L.M. (eds.). Soiuri'Rmksina Sequcmf hcttnnyork.

American Association Petroleum Geoiogisis Bulleiin. Volumi: 48.

PP-

16f) 190.

Boliiics. K.. 1998. Conirasting expressions of deposilional sequenees in

mudrocks lioni marine and non marine environments. In Scliieber.

J.. Zimmerlc. W.. and Sethi. P.S. (eds.). Sluilcs and Muclsioncs.

SluUgerl. E. Scliweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuclihandlung. I. pp.

33-78.

Brett. C.A.. and Allison. P.A.. 1998. Paleontoiogieal approaches to ifie

cnvironmenlal inlerpretation of marine mudrocks. In Sehieber. J..

Zimmerle. W.. and Sethi. P.A. (eds.). Shales ami Mudsloiies.

StuUgarl: E. Schweizcrbart'scfic Verlagsbuchhandlung. Volume I.

pp.

301-349.

Chamley. H.. 1989. Clay

Sctliniciiiulcf^y.

Springer Verlag.

Creuncy. S., and Passey. Q.R,. 1993. Recuning patterns of tolal

organie earbon and source rock quality within a sequence

siraticrapliy trameuork. American Assovialion

PelroteiimGeiilo^i.'ils

Hiil/e'iin.

77: 386 401.

Emery. K.O.. and Llchupi. E., 1984. TlwGcoh^yofdiL' Ailtiiilu Ocemi.

Springer Verlag.

Garrison. R.E.. i99(). Pelagic and hemipelagie sedimentary rock as

source and reservoir rocks. In Brown. G.C.D.S.. and Sfhweller.

W.V. (eds.). Deep Marine Scdiniculaliim: Depo.siliomil Models

anil Case Hisioiies in Hydroearhon Kxphnuioij and Develapmeiil.

Bakersfield: Society Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists,

Pacific Section, pp- l2.Vi49.

Jones.

R.L.. and Blatt. H.. 1984. Mineral dispersal patlems in the

Pierre Shale, .hnivnal Sedimeniaiv feiniim^w 54: 17-28.

Morton, A.C.. Todd, S.P-. and Haughton. P.D.W. (eds.). 1991. flcrc/-

opnietiis in Sedinienitiiy Pruvcnance Sliidiex. Geological Society.

Special Publication. 57.

MUDROCKS

459

Ncsbilt. H.W.. and Young. G.M.. 1982. tarly Proterozoie climates

ant! plale molions inferred from maior element chemistry of lulites.

Niilia-c.

299: 715-717.

O'Brien. N.R., and Slatt. Roger. M.. 1990. Arf^iliarcoiis Rack Alias.

Springer Verlag.

Polter. P.E.. Maynard. Barry.

.1..

and Pryor. W.A.. I98II. Si-Jinieii/nl-

ii^yofShale. Springer Verlag.

Roser. B.P.. and Korsch, R.J.. 1988. Provenance signatures v\'

sandstone -mudstone suiies determined using discriminant function

analysis of major elements. Clieniiinl Geohiiv. 67: 119-139.

Schieber,

.1.,

Zimmerle. W.. and Stehi. S. (eds.)'.'l998. Shales ami Mml-

slones. 1 and II: Sluggart: E. Schweizerbart'sche Veilagsbuchhan-

dlutig. 384 and 2'-Xipp.

Stow. D.A.V.. 1981. Fine-grained sediments: terminology. Qitarei-naiv

Journal En\^iiieciin^(iealo^y. 14: 243 244.

Shepiird, P.P.. 1954. Nomenelalure based on sand-silt-day ratios.

.JournalSi'diniL'nlaiy Petrology. 24: 151-158.

Tyson. R.V.. 1995. Seilimenlary Organic Matter. London: Cbapman

and

Hall.

Weaver, C.E.. 1989.

Ckiy.s.

Mmls. ami Shales. Clsevier.

Wetzel. .A., and Uchmann, A.. 1998. Biogenic structures in tniidslones.

In Sehieber. J.. Zimmerle, W.. and Sethi. P.A. (eds.). Slutlcsami

.\tiidsiiiues. I. Stuggart: Schwei/erbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

pp.

351-369.

Young. G., and Nesbitt, H.W.. 1998. Proeesses controlling the

distribution of Ti and Al in weathering profiles, siliclaslic sediments

and sedimentary rocks. Journal Sedintenlnrv Reseairh. 68: 448-

455.

Zhang, .I.L.. Sun. M.. Wang. S.. and Yu. X., 1998. The composition of

shales frotn the Ordos Basin. China: effects of source weatbering

and diagenesis. Seiliiiieniary

Genlo^^y,

116: 129 141.

Zimmerle, W.. 199S. Petrography of the Boom Clay from the Rupelian

type locality, northern Belgium. In Sehieber. J.. ZImmerie. W.. and

Sethi. P.S. (eds.). Shales and Mudsuines. I: Stuggart: Scbweizer-

bart'sche Verlagsbtichhandlung. pp.

13-3.3.

Cross-references

Blaek Shales

Clay Mineralogy

Colloidal Properties o\ Sediments

Colors of Sedirnentary Roeks

Compaction (Consolidation) of Sediments

Deposilional Fabric of Mudrocks

Flocculation

Oceanic Sediments

N

NEOMORPHISM AND RECRYSTALLIZATION

Recrystallizatioti atid neomorphism arc processes that

transfonrt tninerals in situ into diffcrctit tbrms of themselves,

or a polymorph. Cotifusion exists with the term recrystalliza-

lion becatisc it is sotiietitnes restricted to striiin induced

triitisformatioii (BLtthiirst. 1958) but at other times it is used iti

a general way for any change in form without a change o\'

mineral species. The term replacement is sometimes used for

any mineral transformation, including recrystallization and

neomorphism. Replaeement, however, is often restricted to

transformations that involve changes in bulk eomposition

(synonymous wiih metasomatism) such as dolomitization or

silicification of limestotie. Neomorphism and recrystallization

are thought to occur by simultaneous transformation across a

thin iluid film and are to be distitiguished from cementation

{mineral crystallization in fluid filled cavities). Neomorphistrt.

recrystallization and eementation all involve dissolution and

precipitation, but eement crystallizes in visible (scale of light

microscope) cavities and does not involve simultaneous

dissolution and precipitation at sites separated by a few

mierons or less.

Folk introduced the term neomorphism in 1965 to include

all transformations of older crystals that are gradually

consutncd. and their place simultaneously occupied by new

erystals of the same mineral or a polymorph. Folk pointed out

that recrystallization. used loosely, is synonymous with

neomorphism but that recrystallization sensu stricto excludes

inversion. As such, considerable overlap exists between

neomorphistn and recrystallization, and to avoid eonfusion it

must be clear whether recrystallization is being used in a strict

or loose sense. Folk added texturai riders to the term

neomorphistn to indicate an inerease (aggrading) or decrease

(degrading) in erystal size and whether an increase in size

occurred by growth frotn a few isolated crystals (porphyroid)

or every adjacent crystal (coaleseive).

The transformation of aragonite lo calcite. with or without

interstitial liquid films (Folk. 1965, p.21) has been ealled

inversion but Bathurst (1975. p.234) specifically excluded

water from the process and defined inversion as a dry, solid-

state reaetion. Folk (1965) considered dry inversion of

aragonite to calcite as a special type of neomorphism. The

dry inversion of aragonite to calcite. however, does occur

naturally in blue.schist metamorphic facies (Carlson and

Rosenfeld. 1981). The reaction path and textures produced

in this reaetion are different frotn those found in water-

saturated sediments. Consequently inversion and neomorph-

ism are both polymorphic transformation process, the former

is dry and the latter is wet and their reaction products are

readily distinguishable.

Since 1965 neomorphism has been applied most commonly

to the aragonite to calcite transformation. Investigation has

concentrated on tnollusc shells (Sandberg and Hudson, 1983:

Hendry etal., 1995; and Maliva. 1998). scleractinian corals

(Pingitore, 1976; Martin etal.. 1986). ooids (Wilkinson.

(-/(//..

1984) and botryoidal cements (Sandberg. 1985).

The overlap between recryslallization and neomorphism

and the variable number of transformation processes encom-

passed by these terms has caused confusion. This led Mache!

(1997) to reeommend the abandontnent of the term neomorph-

ism. The term can, however, be usefully applied to the wet

aragonite to calcite transformation for which it has been used

overwheltningly since 1965. Neomorphism would then become

restricted to a common and important type of polymorphic

transformation. Recrystallization, on the other hand, applies

to transformation without change in mineral speeies. Folk

(1965) used neomorphism for transformations where the

mineralogy of the precursor mineral is unknown but recrys-

tallization would be just as apt and the genera! tenn

transformation is recommended here to avoid confusion.

Calcitization is the transformation of any mineral to calcite

and as such can be a type of recrystallization (calcite to

calcite). replacement (e.g., anhydrite to calcite) or neomorph-

ism (aragonite to calcile).

Neomorphism

Neomorphic transformation of a mass of aragonite crystals

usually starts from tnany points within and at the margin of

NFOMORPHISM AND RECKYSTAt.LIZATION

461

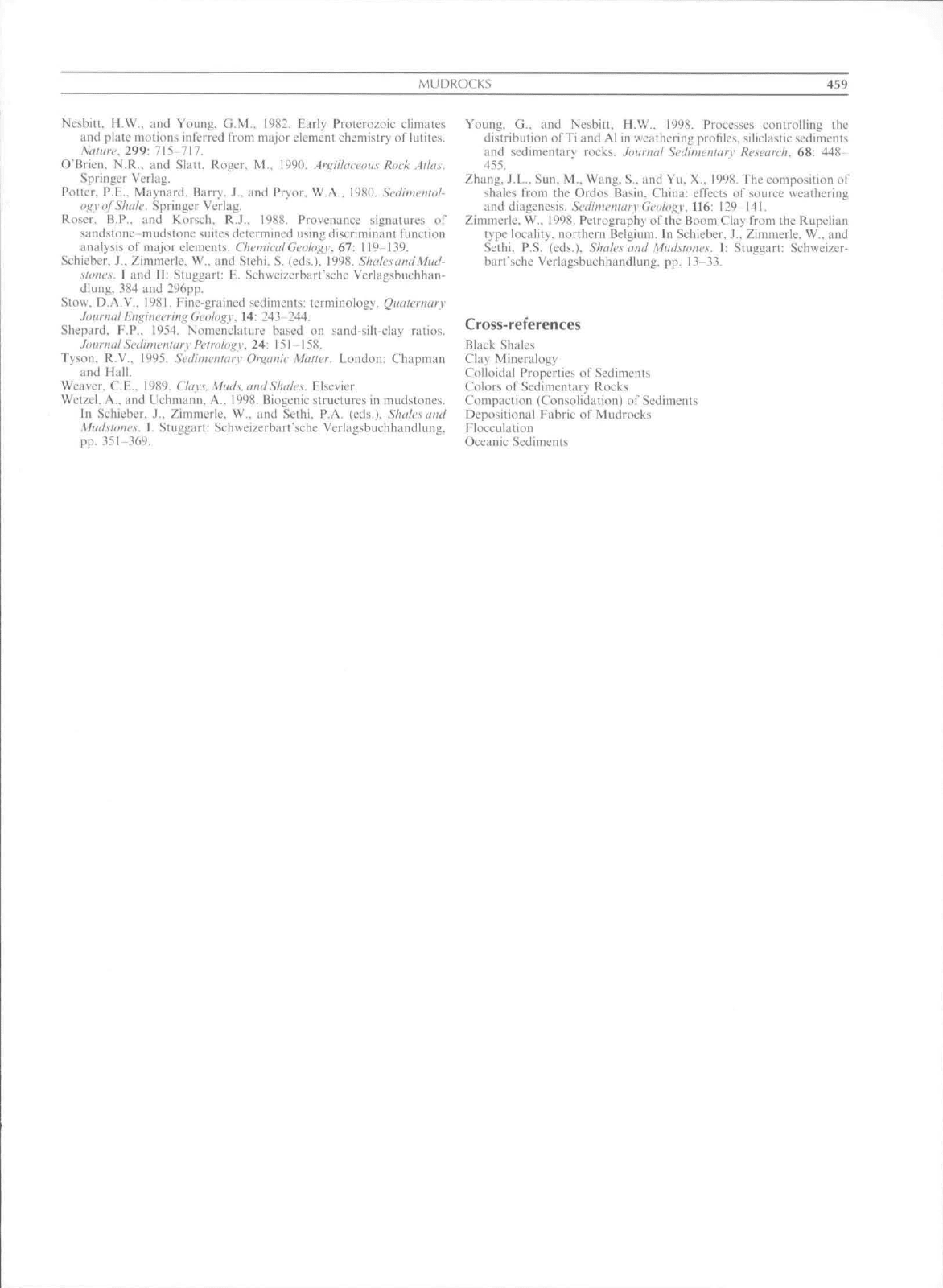

that mass. The fluid that e.xists at each initiation point tnoves

cetitriftigally away from that point as a thin liltn until it stops

against a seam of organic matter; meets another fluid film, or

the transformation stops (Wardlaw etal... 1978; Martin elal..

1986).

The number of initiation points and the manner in

which these films move controls the resulting mosaie of

comparatively few neomorphic (sometimes a single) calcite

crystals. These are optically and texturally largely unrelated to

the preeursor aragonite (Figure Nl). Mineralogical transfor-

mation across such a film is often incomplete, with aragotiite

relics being found encased in the neomorphic calcite. These

relics retain their original orientation and indicate the strueture

of the transfortned grain. Palimpsest structures can also be

preserved in neomorphie calcite by trapped original organic

matter that can give rise to a pale to dark brown pseudopleo-

chroism that is distitictive of some neotnorphic calcites

(Hudson, 1962; Sandberg and Hudson, 1983). In some cases

neomorphism occurs in two stages separated by a long

(10''year) time interval (Hendry eia!.. 1995).

Transformation within the confines of a thin film (although

one has never been directly observed; Wardlaw elal.. 1978)

allows chemical information to be transferred from aragonite

to neomorphic calcite. Many neomorphic calcites contain

- i.OOOpptn Sr (tabulated in Maliva, 1998. p.l8!) a concen-

tration ahove that recorded for most calcite cements

(--300 ppm Sr) and often used to diagtiose Eransfortned

aragonite (Sandberg and Hudson. 1983). Some neomorphie

calcites. however, have Sr eoncentrations that are similar to

adjacent cements (Maliva and Dickson, 1992) and the Sr

content of neomorphic calcite is often overestimated due to

analytical problems (see discussion Pingitore. 1994 and reply

Moshierand Kirkland. 1994).

Work in the 1960s and 1970s eoneentrated on neomorphic

calcite that formed in tneteoric waters; some neomorphic

calcites described IVom vadose and phreatic environments have

different properties (Pingitore. 1976). Neotnorphic ealcite can

also form in modified marine waters (Maliva, 1995) and from

evolved isolated connate waters (Kendall, 1975; Bathursl.

1983).

In all these cases the neomorphie products are similar

and are undiagnostic of the transformation fluid.

Recrystallization

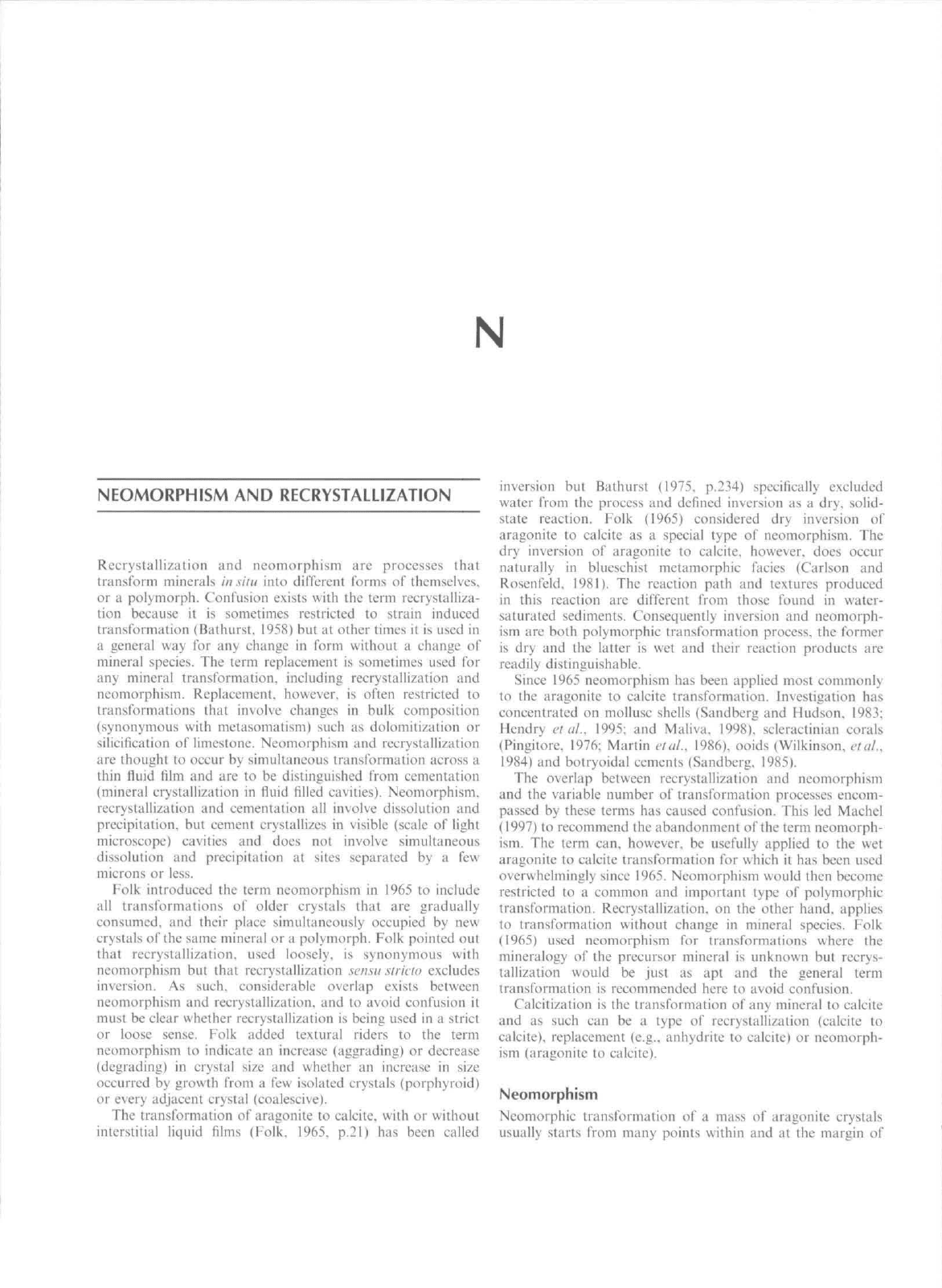

The case for recrystallization is often made for the matrix of

aneient carbonate rocks that are composed of calcite micro-

spar. Modern marine, tropical lime mud the likely precitrsor

to calcite microspar is composed predominantly of meta-

stabic aragonite and Mg ealcite. Lasemi and Sandberg (1984)

have differentiated calcitic microspar into that originally

dominated by aragonite (that has neomorphosed) and that

originally dominated by Mg calcite (that has recrystallized).

Some workers (Steinen, 1982; Munnecke elal., 1997). however.

doubt that the aragonite mud neomorphosed but some

aragonite was trapped in calcite cement that filled the mud's

pore system. Microi^par commonly has an irregular crystal size

distribution, is composed of turbid crystals and contains

impurities concentrated along crystal boundaries (Figure N2).

Such calcite tnicrospar is thought to arise by recrystallization

(Folk. 1965) caused by the metastability of original Mg calcite

but physical processes such as Ostwald Ripening may also

provide the driving force for finely crystalline calcite (Kile

etal.. 2000).

Figure Nl l-'hotomicrof!r.iph (plane polnrized light) of thin section of

Unio Red, Purheck Beds, Lulworth Cove, Dorset, England. Uniovalves

are set in a micrjtic matrix. The original shell structure is preserved in

coarsely crystalline calcite that neomorphosed the orifiinal aragonite

shell.

The mottled appearance of the neomorphic ciltite

\s

caused by

pseudopieothroism, an eflect that causes a color change from

colorless to hrown as the microscope stage is rotated.

Figure N2 Photomicrograph (plane polarized lightl of ihin section of

the Purbeck Beds, DurUton Bay, Dorset, England. Skeletal grains ate

separated by recrystallized lime mud. This sample shows an erratic

crystal size variation and impurities along the intert rystalline

boundaries of the calcite crystals. Original mineralogy unknown.

Conclusions

Recrystallization is a change in mineral fortn (crystal size and/

or shape) without a change in tnineral species or bulk

composition. The term iieomorphism as coined in 1965 is

confusing due to overlap in meaning with reerystallization. but

if restricted to wet polymorphic transformation serves a useful

purpose. Inversion is a dry, solid-state polymorphie transfor-

tnation that is unlikely to occur in water-saturated sediments.

No specific term is available for a mitieral that is interpreted to

have changed form tVom an unidentified preeursor. as is

thought to occur when sotne lime muds are tratisformed to

calcite microspar: here the general tet"m transformation can

be used.

J,A,D. Dickson

462

NEPHELOID LAYER, SEDIMENT

Bibliography

Biithuisl. R.G.C.

1958.

Diagcnctit; fabrics

in

some Britisli Diiiantian

limestones.

The

Liverpool

and

Munche.sh'r

Geoloi;ii'ijl

.lotirmtl,

2:

!1-36,

Bitthiirsl. R.G.C.

197?.

Carhomilc Sedimenis

ami

Their Diagenesis.

DcveiopmeiUs

in

Sedimenlokigy. Volume

12,

Elsevier,

Bathurst. R.G.C.

19S3.

Neomorphic spar versus cement

in

some

Jurussic ^rainstoncs: significance

tor

evaluation

of

porosity

evoiutioti atid compaction. Journal

ol the

Geological Society

of

London.

140:

229-137,

Carlson.

W.D.. and

Rosenfeld.

J.L.. 1981.

Optical detertnination

of

topotactic aragonite-calcite growth kinetics: metamorphic implica-

tions.

Journalof Geology,

89:

615-638.

Folk.

R.L.. 1965.

Sotne aspects

of

recrystallization

in

aticient

limestones.

In

Dolomitization

and

Limestone Diagenesis. SEPM

(Society

tor

SedimetUary Geology). Special Publication.

13. pp,

14-48.

Hendry.

J,P,.

Ditchfield,

P,W,, and

Marshall.

J.D.. 1995.

Two-stage

neomorphism

of

Jurassic aragonitic bivalves: implications

tor

early

diajicncsis. .lourmdofSedimemary Research,

A65:

214-224.

Hudson.

J,D,. 1962.

Pseudo-pleocliroic calcite

in

recrystallized shell

limestones.

Geological

Afat^aiine.

99: 492 500.

Kendall.

A.C.. 1975.

Post-compaclional calciti,^ation

of

molluscan

aragonite

in a

Jurassic litnestonc Irom Saskatchewan. Canada.

Journal of Si'dimenUnv

Pelrolof^v.

45: 399 404,

Kile.

D.F,,. Fbcrl.

DD.^

Hoch.

A,R,. and

Reddy.

M,M..

2000.

An

assessment

of

calcite crystal growth mechanisms based

on

crystal

size distributions. Geochimica

et

Cosmochimica Acta.

64:

2937

2950,

Lasemi.

Z,. and

Sandberg.

P.A.. 1984.

Transformation

of

aragonite-

dominaled lime mtids

to

mierocrystalline limestones. Geology.

12:

420-423.

Machel.

H.G.. 1997.

Recrystallization versus neomorphism.

and the

concept

of

"significant recrystallization"'

in

dolomite research.

Sedimentary Geology.

113: 161- I6K.

Maliva.

R.G.. 1995.

Recurrent neotnorphic

and

cement microtextures

from different diagenetic environments. Quaternary

to

Late

Neogene carbonates. Great Bahatna Bank. Sedimentary Geologv.

97:

17.

Maliva.

R.G.. 1998,

Skeletal aragonite neomorphistn quantitative

modelling

of a

two-water diagenetic system. Sedimentary Geologv.

121:

179-190,

Maliva,

R.G,. and

Dickson. J,A,D,. 1992.

The

mechanism

of

skeletal

aragonite neomorphism: evidence from neomorphosed molluscs

from

the

upper Purbeek P'ormation (Late Jurassic Early Cretac-

eous),

southern Enijland, Sedimentary

Geologv.

76: 221 232,

Martin.

G,D,.

Wilkinson. B,H,,

and

Lohiiiann. k',C,. 1986,

The

role

of

skeletal porosity

in

aragonite neomorphism Slroiiibus

and Mon-

uistrea from

the

Pleistocene

key

Largo Limestone. Florida.

Journal

1)/

Sedimentary Petrology.

56:

194-203.

Moshier.

S,0,. and

Kirkland.

B,L,, 1994,

Ideiilitication

and

diagenesis

of

a

phylloid alga: .Archaeoliihophyllum trom

ihe

Pennsylvimian

Providenee Limestone. Western Kentucky reply. Journal

id

Sedimentary Petrology.

64:

925-928.

Munnecke.

A,.

Weslphal,

H,.

Reijmer. J.J,G,.

and

Samtleben.

C.

1997,

Microspar development during early marine burial diagen-

esis:

a

comparison

of

Pliocene carbonates from

the

Bahamas with

Silurian limestones frotn Gotland (Sweden), Sedimcntologv.

44:

977

990,

Pingilore.

N.F.. 1976.

Vadose

and

phrealie diagenesis: processes,

products

and

their recognition

in

corals, Jimrnal

of

Seetimemary

Pelroiogy.

46\

985-1006,

Pingitore.

N,E.. 1994,

Identification

and

diagenesis

of a

pliylloid alga:

Archaeolitliophyllum from

the

Pennsylvanian Providence Litne-

stone. Western Kentucky—ciiscussion. Journal

of

.Sedimentary

Rf.'fearch.

64:

923-924,

Sandberg.

P,A,. 1985,

Aragonite cements

and

their occurrence

in

ancient limestones.

In

Carbonate Cements. SFPM (Society

for

Seditnentary Geology). Special Publication.

36. pp,

33-57.

Sandberg.

P,A,. and

Hudson.

J,D,, 1983,

Aragonite relic preservation

in Jurassic calcite-rcplaced bivalves, Sedimentology.

30: 879 K92,

Sicinen.

R,P,. 1982, SEM

observations

on the

replacement

of

Bahanian aragonitic

mud by

calcite. Geology.

10: 471 475,

Wardlaw.

N..

Oldershaw.

A., and

Stout.

M,.

I97S. Transformation

of

arai>onite

to

ealcite

in a

marine gastropod, Canadian Journal

of

Earih Sciences.

15:

1861 -1866,

Wilkinson.

B.H..

Btiezynski.

C. and

Owen.

R.M.. 1984,

Chemieal

control

of

carbonate phases: implications from tapper Pennsylva-

nian calcite-aragonite ooids

of

southeastern Kansas, Journalof

Sectimemary Petrology.

54: 932 947,

Cross-references

Cements

and

Cementation

Di agenesis

Micritization

Sedimentologists

NEPHELOID LAYER, SEDIMENT

Introduction

The lower water colutnii

in

most parts

of the

ocean, both shelf

waters

and the

deep

sea.

shows

a

large inerease

in

light

scattering

and

attenuation eonlerred

by the

presence

of

increased amotints

ol"

fine-grained parlicitlate material. This

has been eonfirmed

by

size nieasuretnents

and

filtration

of

seawater with gravimetric analysis. This part

of the

water

column

is

termed

the

bottom nepheloid layer

(BNL)

(Figure

N3),

Optical work shows that

the BNL is up to

1000

2000

3000

SNL

KNORR-51 STA.698

ROCKALL TROUGH

54°

23,1

N 15-

18.7'W

(a)

v\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\V

•

NEPHELS, ARBITRARY SCALE

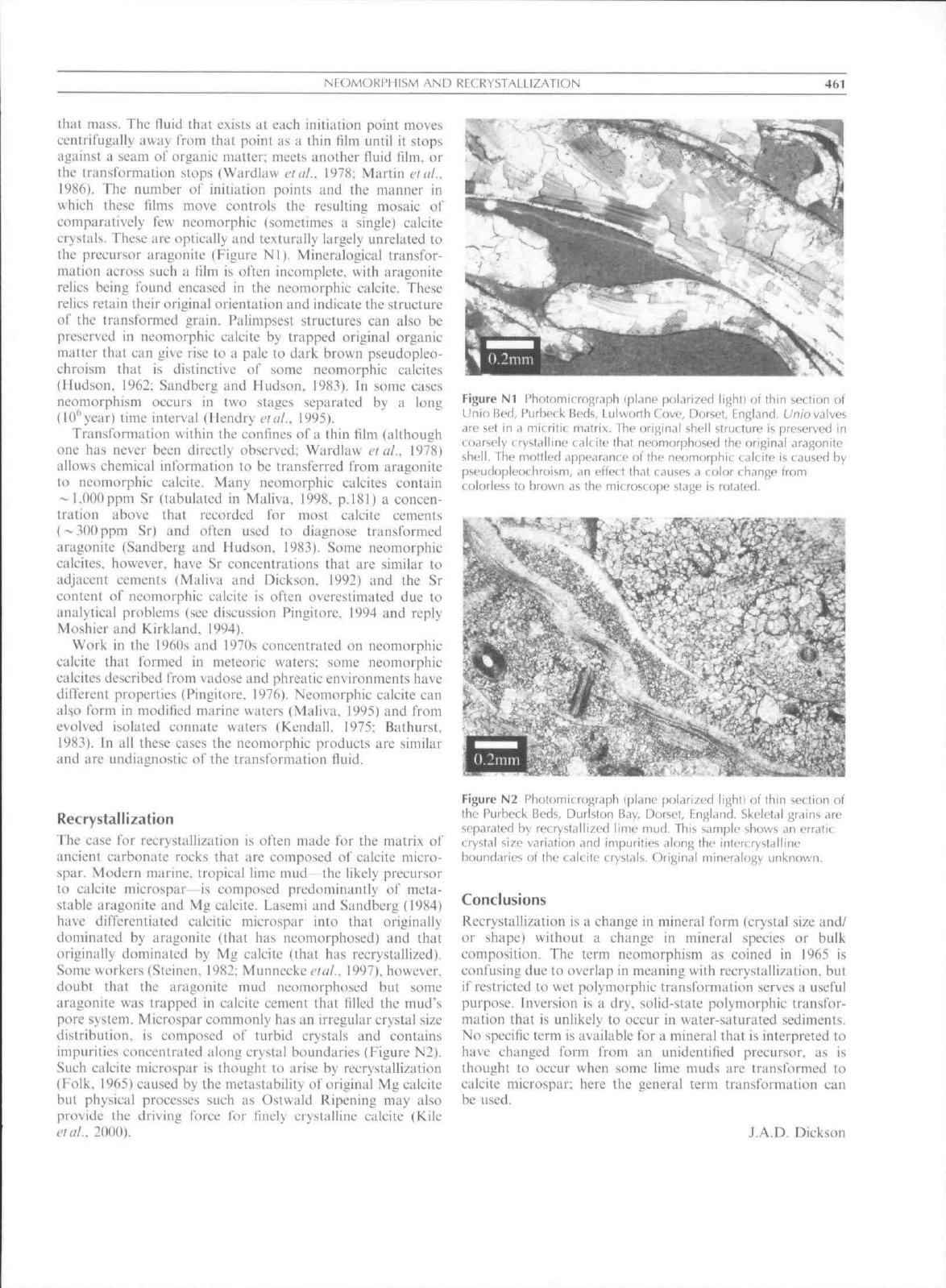

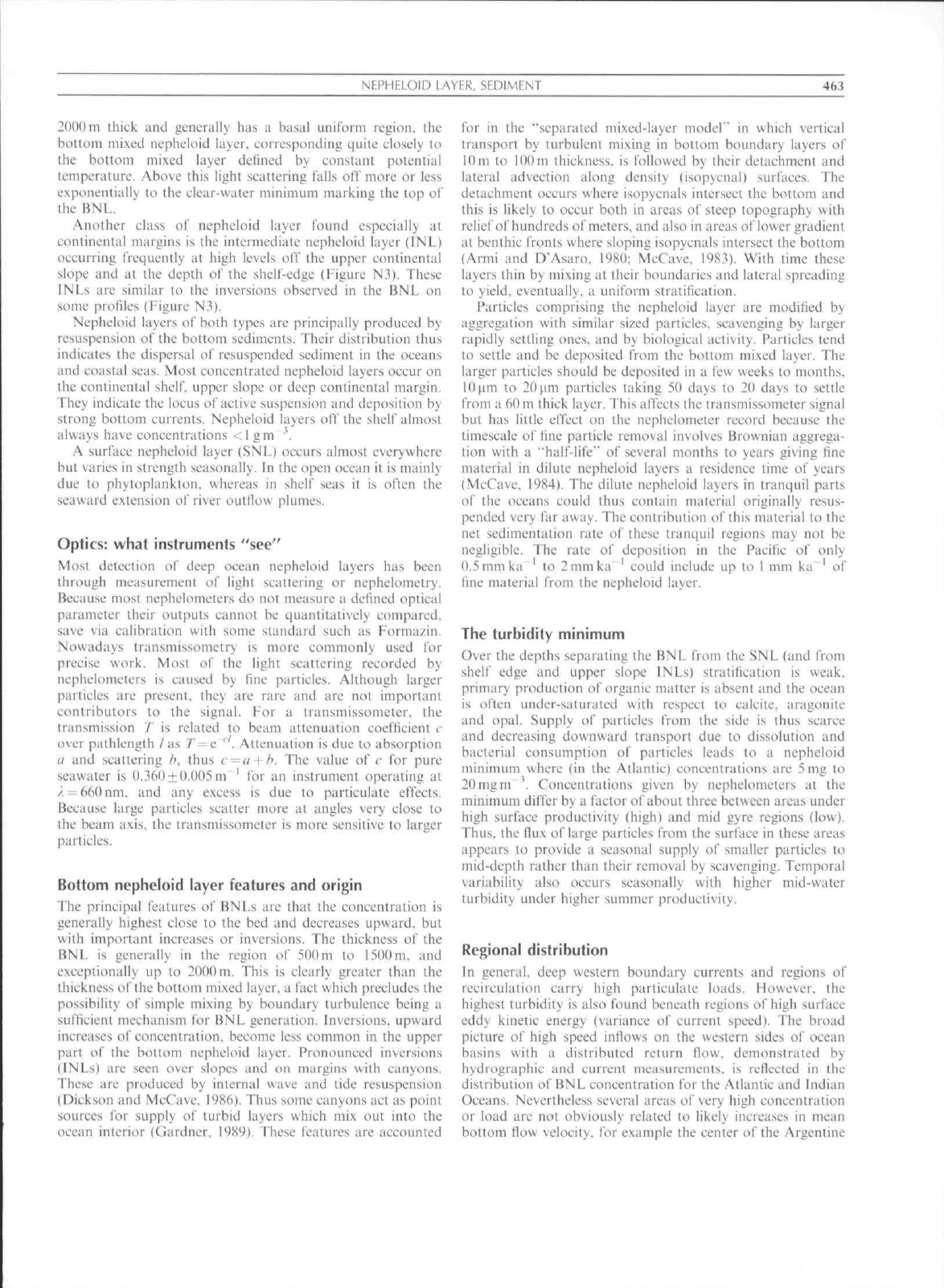

Figure N3 Full depth nephulomuter [jrolile in thf RockdII Trough,

Bottom,

intermediate and surface nepheloid layers and the clear waier

minimum are apparent as well as two large inversions (after McCavo,

19861.

The instrument is uncalibratcd bul in this area the maximum

concentration is probably of order 500 mgm

'

NFPHFI.OID lAYER, SEDIMENT

463

2000 m thick and gener:illy has a basal uniform region, the

bolloni mixed nepheloid layer, corresponding quite closely to

the bottom mixed layer defined by constant potential

temperature. Above this light scattering falls olT more or less

exponentially to the clear-water minimum marking the top of

the BNL,

Another class of nepheloid layer found especially at

continental margins is the intermediate nepheloid layer (INL)

occurring frequently at high levels off the upper continental

slope and al the depth of the shelt^-edge (Figure N3). These

INLs are similar to the inversions observed in the BNL on

some profiles (Figure N3).

Nepheloid layers of both types arc principally produced by

resuspeiision of the bottom sediments. Their distribution thus

indicates the dispersal of resuspended sediment in the oceans

and coastal seas. Most concentrated nepheloid layers occur on

the continental

shelf,

upper slope or deep continental margin.

They indicate the locus of active suspension and deposition by

strong bottom currents. Nepheloid layers off the shelf almost

always have concentrations <1 gm ".

A surface nepheloid layer (SNL) occurs almost everywhere

but varies in strength seasonally. In the open ocean il is mainly

due to phytoplankton. whereas in shelf seas it is often the

seaward extension of river oulllow plumes.

Optics: what instruments "see"

Mosl deteclion of deep ocean nephetoid layers has been

through measurement of light scattering or nephelomelry.

Because most nephelometers do not measure a defined optical

parameter iheir outputs cannot be quantitatively compared,

save via calibration with some standard such as Formazin,

Nowadays transmissometry is more commonly used for

precise work. Most of the light scattering recorded b>

nephelometers is caused by fine particles. Although larger

particles are present, they are rare and are not important

contributors to the signal. For a transmissometer. the

transmission T is related to beam attenuation coefficient c

o\cr pathlength /as T=Q ' . Attenuation is due to absorption

a and scattering h. thus c=^a + b. The value of c for pure

seawater is 0,36()±0.0()5m ' for an instrument operating at

/.-660nm, and any excess is due to particulate effects.

Because large particles scatter more at angles very close to

the beam axis, the transmissometer is more sensitive to larger

particles.

Bottom nepheloid layer features and origin

The principal features of BNLs are that the concentration is

generally highest close to the bed and decreases upward, but

with important increases or inversions. The thickness of the

BNL is generally in the region of 500m to 1500m, and

exceptionally up to 2000 m, This is clearly greater than the

thickness of the bottom mi,\ed layer, a fact which precludes the

possibility of simple mixing by boundary turbulence being a

sufficient mechanism for BNL generation. Inversions, upward

increases of concentration, become less common in the upper

part of the bottom nepheloid layer. Pronounced inversions

(INLs) are seen over slopes and on margins wiih canyons.

These are produced by internal wave and tide resuspension

(Dickson and McCave. 1986). Thus some canyons act as point

sources for supply of turbid layers which mix out into the

ocean interior (Gardner. 198'J). These features are accounted

for in the "separated mixed-layer model" in which vertical

transport by turbulent mixing in bottom boundary layers of

lOm to 100m thickness, is followed by their detachment and

lateral advection along density (isopycnal) surfaces. The

detachment occurs where isopycnals intersect ihe bottom and

this is likely to occur both in areas of steep topography with

reliel'of hundreds of meters, and also in areasof lower gradient

at benthic fronts where sloping isopycnals intersect the bottom

(Armi and D'Asaro. 1980: McCave. 1983), With time these

layers thin by mixing at their boundaries and lateral spreading

to yield, eventually, a uniform stratification.

Particles comprising the nepheloid layer arc modified by

aggregation with similar sized particles, scavenging by larger

rapidly settling ones, and by biologieal activity. Particles tend

to settle and be deposited from the bottom mixed layer. The

larger particles should be deposited in a few weeks to months.

iOnm to 20nm particles taking 50 days to 20 days to settle

from a 60 m thick layer. This affects the iransmissometer signal

but has little effect on the nephelometer record because the

timescale of fine particle removal involves Brownian aggrega-

tion with a "half-life" of several months to years giving fine

material in dilute nepheloid layers a residence time of years

{McCave. 1984). The dilute nepheloid layers in tranquil parts

of the oceans could thus contain material originally resus-

pended very far away. The contribution of ihis material to the

net sedimentation rate of these tranquil regions may not be

negligible. The rate of deposition in the Pacific of only

0.5nimka ' to 2mmka ' could include up to

1

mm ka~' of

fine material from the nepheloid layer.

The turbidity minimum

Over ihe depths separating the BNL from the SNL (and from

shelf edge and upper slope INLs) stratification is weak,

primary production of organic matter is absent and ihe ocean

is often under-saturated with respect to calcite. aragonite

and opal. Supply of particles from the side is thus scarce

and decreasing downward transport due to dissolution and

bacterial consumption of particles leads to a nepheloid

minimum where (in the Atlantic) eoncentrations are

5

mg to

20mgm , Concentrations given by nephelometers at the

minimum differ by a factor of about three between areas under

high surface productivity (high) and mid gyre regions (low).

Thus,

the flux of large particles f>om the surface in these areas

appears to provide a seasonal supply of smaller particles to

mid-depth rather than their removal by scavenging. Temporal

variability also occurs seasonally with higher mid-water

turbidity under higher summer productivity.

Regional distribution

In general, deep western boundary currents and regions of

recirculation carry high particulate loads. However, the

highest turbidity is also found beneath regions of high surface

eddy kinetic energy (variance of current speed)- The broad

picture of high speed inflows on the western sides of ocean

basins with a distributed return tlow. demonslrated by

hydrographic and current measurements, is reflected in the

distribution of BNL concentration for the Atlantic and Indian

Oceans. Nevertheless several areas of very high concentration

or load are not obviously related to likely increases in mean

bottom fiow velocity, for example the center of the Argentine

4 (.4

NERITIC CARBONATE DEPOSITIONAL ENVIRONMENTS

Basin (Biscaye

and

Eiltreim. 1977). These turbidity highs

may

be caused

by

intermittently high velocities.

The fact that there

is

more suspended materiai

at

ocean

depths greater than about 4000

m

partly refiects

the

fact that

waters

at

those depths

are in

contact with

a

much greater

potential source area

of

seabed

in

proportion

to

their volume

than

the

shallower parts

of

the oceans.

For

4 km

lo ? km

depth

the value

is

0.83 km"/km

.

whereas

for

2 km

to

3

km it is

0.11 km"/km"\ Deeper waters feel more

bed.

L Nicholas McCave

Bibliography

Armi.

L,.

iind D"Asaro,

E,.

1980, Flow structures

of

the benthic oceiin.

Journal of Geophysical Research.

85: 469 4S4.

Biscaye.

P.F,. and

EiUreim.

S,L,.

1*^77,

Stispendcd partiLiilalc loads

and Iransporls

in

liie nephcloid layer

of

the abyssal Atlantic Oceiui.

Marine

Geology.

23: 155 172.

Dickson.

R.R,. and

McCave,

LN,. 1986,

Nepheloid layers

on the

continental slope west

of

Poreupine Bank, Dvep Sea Research.

33:

791

818,

Gardner.

W,D,. 1989,

Periodic resiispcnsion

in

Baltimore Canyon

by

Ibcusinu

of

intcrna! waves. Journal

af

Geophysical Research.

94:

I8I85-I8I94,

McCave.

LN,.

1983. Particulate size spectra. heliii\iour arui origin

of

nepheloid layers over

the

Nova Scotian Continental Rise, Journal

of

Geophysical

Research.

88:

7647-7666.

MeCave.

I,N,. 1984,

Size-spectra

and

aggregation

of

suspended

particles

in the

deep oceiin, Deep-Sca Research. 31: 329-352,

McC;ive.

LN,.

1986. Local

und

global aspects

of

the boltom nepheloid

layers

in ihe

world ocean, Netherlands Joiaiialot Sea Research.

20:

167-181.

Cross-references

Continenlal Rise

and

Slope

FloccLilation

NERITIC CARBONATE DEPOSITIONAL

ENVIRONMENTS

Introduction

Marine carbonate sedimentation (Bathurst.

1975;

Scholle

etal.,

1983:

Tucker

and

Wright.

1990;

James

and

Kendall.

1992;

Wright

and

Burchette.

1996)

takes plaee

in two

environments,

the

benlhic, neritic realm

and the

pelagic

deep-sea realm

(see

Oceanic Sediments). Neritic carbonate

sediments

are

"born"

as

precipitates

or

skeletons within

the

depositional environment. This attribute

has

profound

con-

sequences:

(I)

large structures such

as

platforms

are

produced

entirely

by

sediments formed

in

place, they

are

self-generating

and self-sustaining;

(2) the

temporal

and

spatial style

of

accumulation depends upon

the

nature

of the

sediments

themselves;

(3)

sediment production

can

fill accommodation

space

and

thus create shallowing-upward. autoslraligraphic

patterns;

(4)

grain size variations need

not

signal changes

in

hydraulic regime;

and (5)

sediment composition

is

fundamen-

tal

in

characterizing

the

depositional environment.

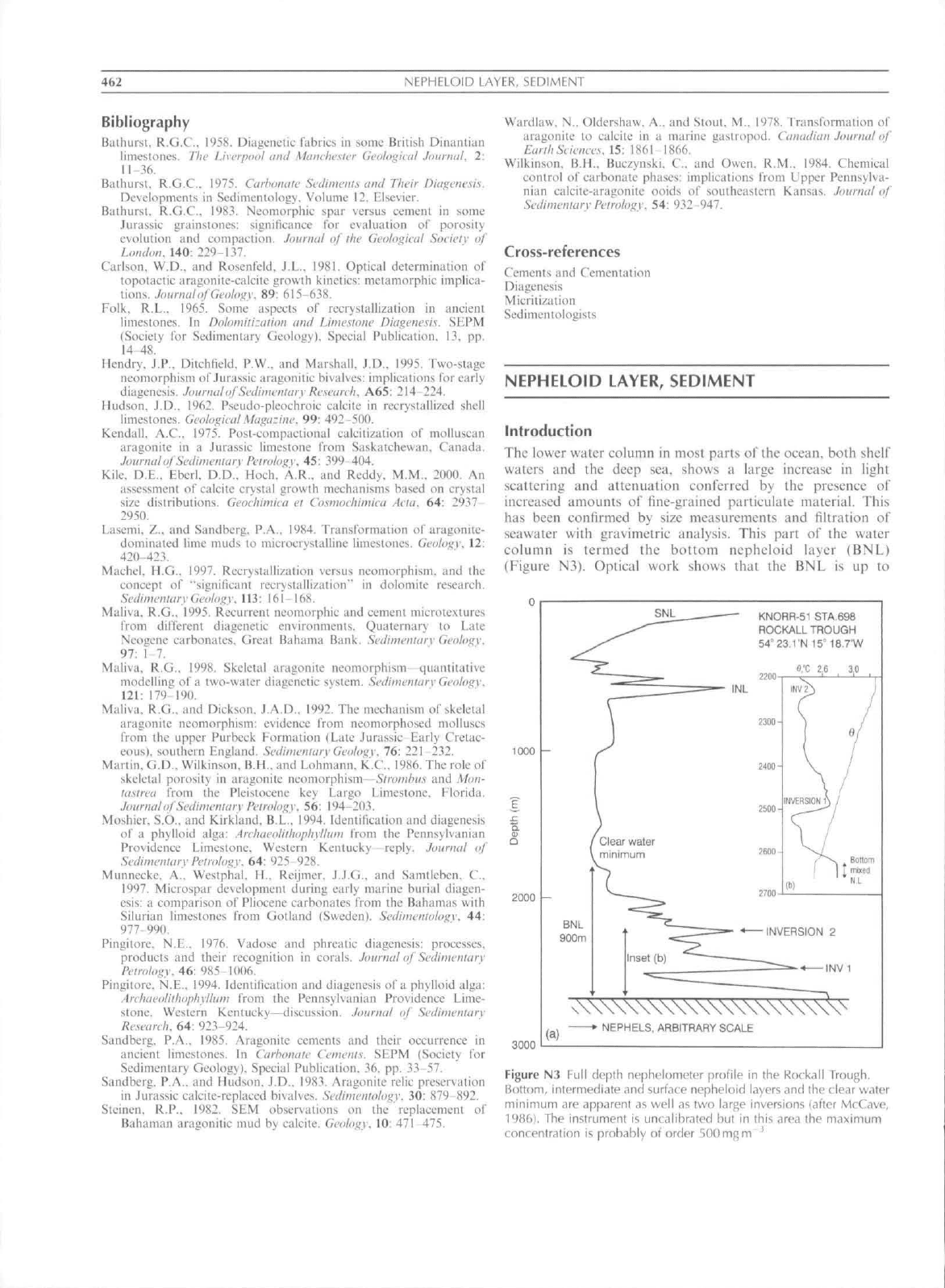

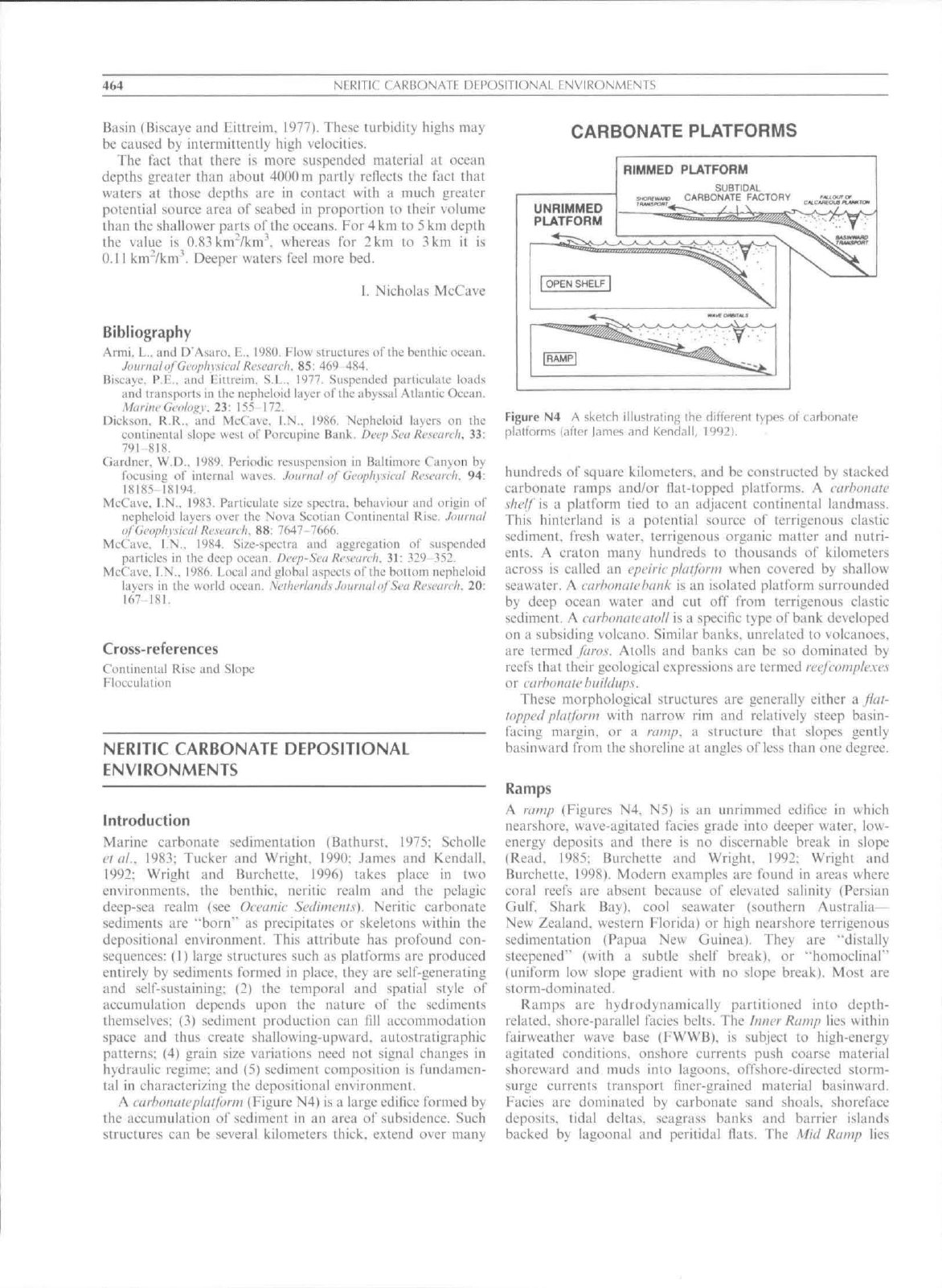

A carhotuiteplatfortn {Figure

N4) is a

large edifice formed

by

the accumulation

of

sediment

in an

area

of

subsidence. Such

structures

can be

several kilometers thick, extend over many

CARBONATE PLATFORMS

Figure

N4 A

sketch illustrafing

Ihe

different types

of

carbon^ate

platforms (after lames and Kendall, 1992).

hundreds

of

square kilometers,

and be

constructed

by

stacked

carbonate ramps and/or flat-topped platforms.

A

cat-hoiiatc

\/?('//

is a

platform tied

to an

adjacent continental landmass.

This hinterland

is a

potential source

of

terrigenous clastic

sediment, fresh vi'ater. terrigenous organic matter

and

nutri-

ents,

A

craton many hundreds

to

thousands

of

kilometers

across

is

called

an

epeiric plaiforni when covered

by

shallow

seawater.

A

carhotuitehattk

is an

isolated plattbrm surrounded

by deep ocean water

and cut off

from terrigenous clastic

sediment,

A

cufhonateatol!

is a

specific lype

of

bank developed

on

a

subsiding volcano. Similar banks, unrelated

to

volcanoes,

are termed faros. Atolls

and

banks

can be so

dominated

by

reefs that their geological expressions

are

termed fcefcomple.xes

or cufbonali'buildups.

These morphological structures

are

generally either

-d

fiat-

lopped platform with narrow

rim and

relatively steep basin-

tacing margin,

or a

ramp,

a

structure that slopes gently

basinward from

the

shoreline

at

angles

of

less than

one

degree.

Ramps

A ratnp (Figures

N4. N5) is an

unrimmed edifice

in

which

nearshore, wave-agitated facies grade into deeper water,

low-

energy deposits

and

there

is no

discernable break

in

slope

(Read.

1985;

Burchette

and

Wright.

1992:

Wright

and

Burchette, 1998), Modern examples

are

found

in

areas where

coral reefs

are

absent because

of

elevated salinity (Persian

Gulf.

Shark

Bay),

cool seawater (southern Australia—

New Zealand, western Florida)

or

high nearshore terrigenous

sedimentation (Papua

New

Guinea), They

are

"distally

steepened" (with

a

subtle shelf break),

or

"homociinal"

(uniform

low

slope gradient with

no

slope break). Most

are

storm-dominated-

Ramps

are

hydrodynamically partitioned into depth-

related, shore-parallel facies belts.

The

Ititier Ramp lies within

fairwcathcr wave base (FWWB),

is

subject

to

high-energy

agitated conditions, onshore currents push coarse material

shoreward

and

muds into lagoons, offshore-directed storm-

surge currents transport finer-grained material basinward.

Facies

are

dominated

by

carbonate sand shoals, shoreface

deposits, tidal deltas, seagrass banks

and

barrier islands

backed

by

lagoonal

and

peritidal flats.

The Mid

Ramp lies