Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

NUMERICAL MODFLS AND SIMULATION OF SEDIMENT TRANSPORT AND DEPOSITION 475

Nelson.

C.S.

(ed.l.

1988. (\)ol water carbonate sediments. Si'diinciilary

Geology.

60: 367pp.

Pralt. B.R.. .lames. N.P.. and Cowan. C.A.. I9')2. Perilidal earbonates.

In Walker. R.G., and James. N.P. (eds.),

FuciesModels

Response

lo

Sea

Level

Chiint;e.

Geologieal Assoeiation of Canada, pp. 303

.322,

Purser. B.H. (ed.).

!97.'l.

Ihe

Persian

Gidf:

Holocene Cartionaie

Scdi-

inciitaiioii and

Diiijicne.sis

in a

Shallow Epiconlinenlal

Sea.

Springer-

Verlag.

Read.

J.F.. 1985, Carbonate platform facies modeLs.

American

As.so-

ciationof PclrolcuniCicologi.sis. Bulletin. 69: 121.

Schlager. W,. |y8l. The paradox of drowned reefs and carbotiate

platforms.

Geological Sodeiy

of

America

Bulleiin. 92:

197-211.

Scliolle. P,A,. Bebout. D.G.. and Moore. C.H. (eds.). 1983.

Carhomae

Deposilional Enviroiinienis. American .Association of Petroleum

Geologists. Memoir 33. 708pp.

Stanley. G,D, Jr.. and Fagcrstrom. J,A, (eds,). 1988, Ancient reef

ecosystems issue.

Pataios.

3: 110 250,

Toomcy, D.F. (ed.). 1981.

Earopean Fo.ssil

Reef

Models.

Soeiety of

Eeonomie Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Special Publication

30.

546pp.

Tucker. M.E.. and Wright. V.P,. 1990,

Carbonate

Sedimentohigy.

Blackwell Scientilic Publications.

Wilson.

J.L.. 1975.

Carbonate

Fades in

Geologic

History. Springer-

Verlag.

Wood.

R.. 2000.

Reel

Evolution.

Oxtord L'niversity Presy

Wright. P.V.. and Buichette. T,P., 1996. Shallow-water carbonate

environtnenls. In Reading. H. (ed.). Sedinieniarv

F.nvironments,

Blackwell Science, pp,

.''25""

?94.

Wright. V.P., and Binehetlc. T.P.. 199S,

Carbonate

Ramps.

Geologieal

Soeiety Speeial Ptiblication. 149. 465pp,

Cross-references

Algal and Bacterial Carbonaie Sediments

Ueach

rock

Bioelasts

Bioerosion

Caleile Compensation Depth

Carbonate Diagenesis and Microfacies

Carbonate Mineralogy and Geochctnistry

Carboitate Mud Mounds

Cements and Cementation

Classification of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Diagenesis

Dolomites and Dolomitization

Fncriniles

Micritizalion

Mixed Silieielastic and Carbonate Sedimentation

Seawaler: Temporal Changes in the Major Solutes

Sedimentologists

Stromatolites

NUMERICAL MODELS AND SIMULATION OF

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT AND DEPOSITION

A numerical model sitniilaling sediment transport and

deposition is an equation set describitig the spatial and

temporal evolution of a fluid flow carrying sediment over,

and inieriicting

with,

an adjacent mobile particulatc bed.

Althottgli liicrally scores

Q\'

such models exist, each starting

from quite dilTcrent assumptions and incorporating quilc

dil't'erenl sedimentary proccsse.s, the most common and the

locus of this entry are process-based models constructed with

ihe mutual goals of prediction and understanding. Given water

and .sediment mass fluxes delivered to a geomorphic system

lhr(iugh time, these numerical models are expected to

accurately prediet the total mass flux and character ol"

sediment passing each point in the system at time and space

scales appropriate for the applieation. To do so, each model

must capture how changes in state variables ofthe fluid flow.

the sediment transport, and the deforming bed induence one

another ihrough feedback loops. Each also must embody the

physical processes thought to be relevant and consequently

each is a conjecture about the dynatnical behavior oi the

geomorphic system. Thus, for e.xarnple. if the geotnorphic

system is a river channel reach of a given initial hydraulic

geometry and sediment characteristics with a given sediment

and water feed at the upstream end. the model in question

should predict accurately the temporally evolving flux of water

and sediment along the reach and ihe amount of bed erosion

or deposition through time using conservation and rate laws

that describe all the processes and their interactions. This etitry

describes the character, use, and limitations of this general

class of sediment transport model. Channelized flows are

emphasized, although much of the discussion also applies to

sediment transport models of lakes and coastal oceans. Aiso.

the emphasis here is on non-cohesive sediment transport

because tnost models, if they address eohesive sediment at all.

are still quite primitive in its treatment. Table NI hst some

popular examples.

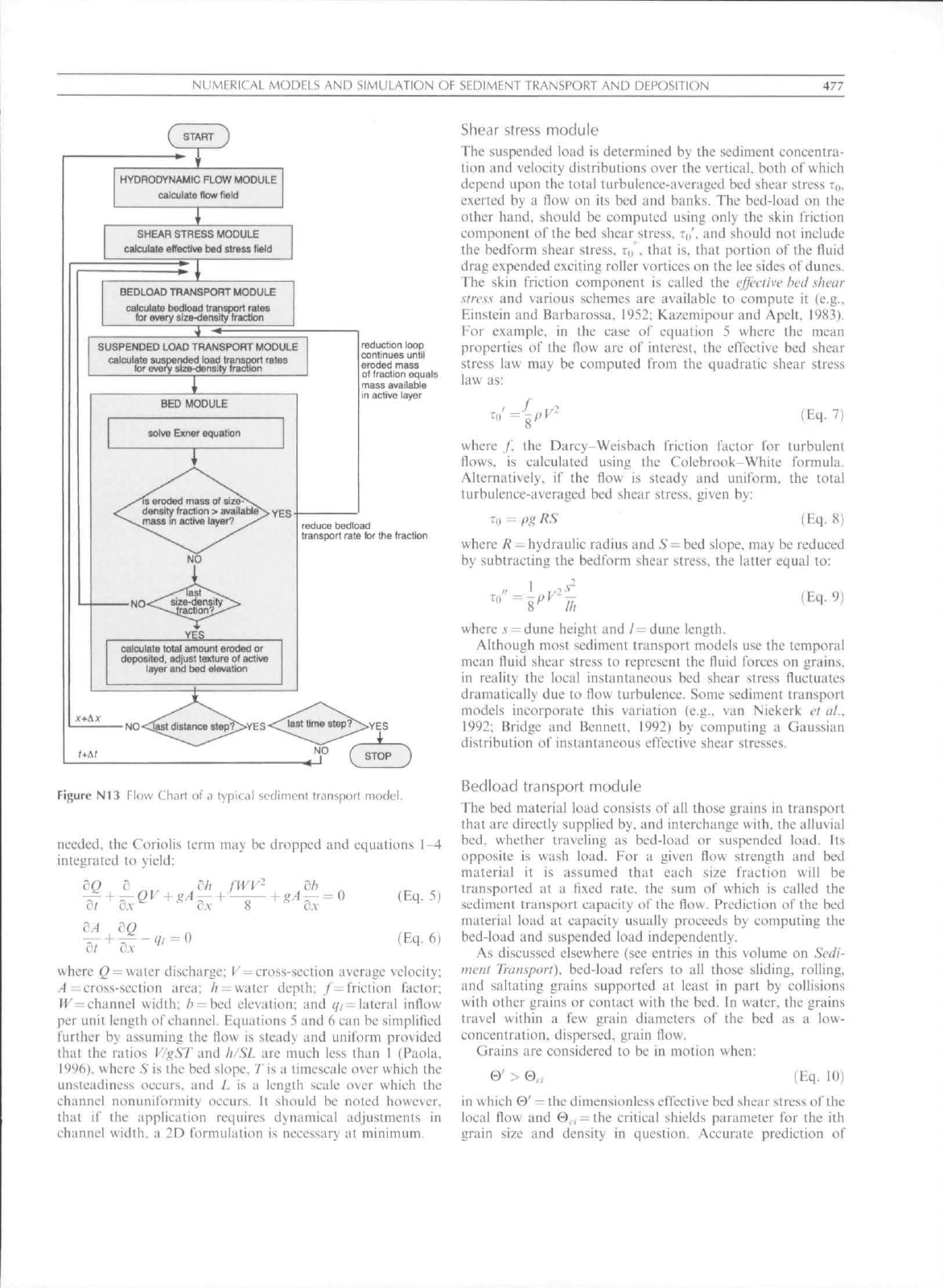

Model components

There are five components or computation modules in a

sediment transport model: (1) a hydrodynamic module to

compute the flow

field:

(2) a shear stress module to calculate

the stress effective in transporting sediment as the bed

roughness evolves and in some models, lo calculate the shear

stress distribution arising from turbulent fluctuations; O) a

bed-load transport module: (4) a suspended load transport

module: and (5) a bed module that keeps track of

bed

erosion.

deposition,

and the evolving bed texture. The computation

modules are organized into a soltttion algorithm, the structure

of

which

depends upon whether the equation set is to be solved

simultaneously or in series. Figure N13 gives a typical

organization o\' the computation modtiles for a series solution

of a 1-D. unsteady, nonutiilorm application. Becattse contin-

uous solutions to the eqtialion set are not known, the set is

always solved by either finite-difference or ftnite element

techniques at discrete nodes in the model space, .v=lA.v,

2A.V,.. ..rtA.v, y=

I

A)'....

/ = IA/.... and so on.

Each of the five components is described below. For the

purposes of illustration, a right-handed Cartesian coordinate

system is assumed iti which v deflnes the primary horizontal

flow

direction,

v the transverse direction, and z is positive

upward.

Hydrodynamic module

An accurate description ol" the fluid flow field is a necessary

condition for predicting sediment transport and deposition.

Without sigtiilieant loss of generality most geomorphic

hydraulic rnodels assume that the fluid is incompressible, the

fluid density is everywhere equal, the pressure distribution in

the fluid is hydrostatic, and the eddy viscosity approach can be

used to describe the role of turbulence in momentum transfer

(see Lane, 1998 for a review). Whether further simplifications

are justified depends upon the application. In the most

demanding applications the flow field is unsteady and

476

Table

Mode

NI

1

Some popular

NUMERICAL MODELS

AND

numerical sediment transport

Authors

SIML'IATION

models

OF

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT

Comments

AND

DFPOSITION

HEC-6 4,1

TABS-SED2D 4.5

MIKE 11

CH3D-SED

MIDAS

FFDC

ECOM-SED

US Army Corps of

Engineers

US Army Coips of

Engineers

DHI Water atid

Environment. Iric,

Gessler <•/(//,. 1999

van Niekerk

et(d.,

1992

Tetratech

HydroQual. Int:. &

Dclfl Hvtliiiulics

I

D. movable bed, open channel flow model simulating

scour and deposition from steady flows; FEMA^

approved

SED2D computes sediment loadings and bed elevation

changes when supplied with a flow tield from TABS or

RMA2:

treats clay beds; FEMA approved

ID,

commercial movable bed open channel flow model

simulating cohesive and non-cohesive sediment trans-

port and deposition; FEMA approved

3D model of unsteady flows in estuaries and rivers,

including vertical mixing and surface heal exchange;

suspended sediment transport modeled hy 3-D

advection-diffusioii equation

freely-available. ID. open channel, tutcoupled unsteady,

gradually-varied flow and sediment model

freely-available, curvilinear orthogonal coordinate,

coupled hydrodynamic and sediment model for coastal

oceans

3D.

cotnmcrical hvdrodvnamic and sediment model

" US Federal Emergency Management Aguncy

noniiniform and significant secondary circulation exists.

Consequently, the hydraulic module must compute the

instantaneous, turbulence-average fiow veloeities ti. y. and u'

at all nodes in the model space, as well as the water surface

elevation, h at all surlace nodes. Four dependent variables

require four equations for their solution. The equations are the

X- and v-direirted general laws of motion, the hydrostatic

pressure distribution in the vertical, and conservation of mass

equation:

accounts for fluid pressure gradients arising from gradients in

the water surface elevation; Term 5 accounts tor shearing

forces per unit mass due to velocity gradients in the horizontal

and Term 6 accounts for shearing forces per unit mass due to

velocity gradients in the vertical.

Before the equation set can be solved for the dependent

variables, the turbulent diffusion coefficients must be specified.

Numerous approaches exist {ef. Nezu and Nakagawa. 1993)

ranging from "zero-equation" turbulence models that specify

•du

0/ '

Or

dl '

(i)

dp

du'

d

O.Y

6v

0 dy-

O.Y"'

"^ Sv

(2)

'Or*^

0

'Or'

(3)

10/7

pdx

10/7

p ^y

(4)

'' ( i

dx^^

1 ^ i

ex \

du\ 0 /

//. +. '

dxJ vy

V

' dv\ 0

. "<^-V Ov

(5)

(A ^''\

a

/

ar

V

d

'

a_-

(

^")

1^

dv\

(6)

(Eq. 1)

(Eq. 2)

(Eq. 3)

du

6v dw

(Eq. 4)

where u, v,

w

—velocity components in the .v. v. z-directions;

/ = time;

/^

—Coriolis parameter;

/>

= local fluid density, ac-

counting for temperature, salinity, and sediment concentra-

tion; p = pressure; A,,"^ horizontal turbulent diffusion

coefficient;

v4(,-

—vertical turbulent diffusion coefficient; and

^ = gravitational acceleration. Term 1 above accounts for

unsteadiness of flow; Term 2 accounts for nonuniformity of

fiow; Term 3 accounts for Coriolis accelerations; Term 4

constant coefficients to "two-equation"" models that equate Af

to the square o\' the turbulence energy per unit mass and lo the

inverse of its rate of dissipation. Turbulence production and

dissipation in turn are computed at all nodes using transport

equations for the turbulence.

In selected applications the above equation set can be

considerably simplified. For example, if only a cross-sectional

average description of the flow in a rectangular channel is

NUMERICAL

MODnS AND SIMULATION OF SEDIMENT TRANSPORT AND DEPOSITION

477

HYORODYNAMIC

FLOW MODULE

caiculate

flow field

SHEAR

STRESS MODULE

calculate

etfective bed stress field

BEOLOAD

TRANSPORT MODULE

calculate

bed

load

transport rates

for

every size-density fraction

SUSPENDED LOAD TRANSPORT MODULE

calculate

suspended load Iranspori rales

lor

every size-density fraction

BED

MODULE

solve

Exner equation

IS

eroded mass of size

density

fraction > available

5

m active I

•NO

YES

calculate

total amount eroded or

deposited,

adjust texture of active

layer

and bed elevation

reduction

loop

continues

until

eroded

mass

of

fraction equals

mass

available

in

active layer

reduce

bedload

transpOft

rate for the (raction

NO<&st distance stepr>YES

<C

last time 3tep

Figure

N13 Flow Chart oi a lypital sediment transport

model.

needed, the Coriolis tenii may be dropped and equations

integrated to yield:

1-4

dh db

dA

(Eq.6|

where ^ = water discharge;

^'

= cross-section average velocity;

/)= cross-section area; /f —water depth; /'—friction factor;

W^

= channcl width; /i = bed elevation; and i//-lateral inflow

per unit length of channel. Equations 5 and 6 can be simplified

ftirther by assuming the flow is steady and uniform provided

that the ratios I'X'.STand h/SL arc much less than 1 (Paola,

lyyt)),

where

.V

is the bed slope, Tis a timeseale over which the

unsteadiness occurs, and L is a length scale over which the

channel nonuniformity oecurs. It should be noted however,

(hat if the application requires dynamical adjustments in

channel width, a 2D formulation is necessarv at tninimutii.

Shear

stress module

The suspended load is determined by the sediment concentra-

tion and velocity distributions over the vertical, both of which

depend upon the total turbulence-averaged bed shear stress To,

exerted by a flow on its bed and banks. The bed-load on the

other hand, should be computed using oniy the skin friction

component ofthe bed shear stress, r,,'. and should not include

the bedform shear stress. lo". that is, that portion of the fluid

drag expended exciting roller vortices on the lee sides of dunes.

The skin ft-iction cotnponent is called the elective bed shear

stress and various schemes arc available to compute it (e.g..

Einstein and Barbarossa, 1952; Kazemipour and Apelt. 1983).

For example, in the case of equation 5 where the mean

properties of the flow are of interest, the effective bed shear

stress law may be computed from the quadratic shear stress

law as:

Xo'=-^-pV'' (Eq. 7)

where /'. the Darey-Weisbach friction factor for turbulent

flows, is calculated using the Colebrook-White formula.

Alternatively, if the flow is steady and uniform, the total

turbulence-averaged bed shear stress, given by:

To

- pg RS

(Eq. 8)

where R = hydraulic radius and

.S"

= bed slope, may be reduced

by subtracting the bedform shear stress, the latter equal to:

to'

(Eq. 9)

where

.«

= dune height and / = dune length.

Although most sediment transport models use the temporal

mean fluid shear stress to represent the fluid forces on grains,

in reality the local instantaneous bed shear stress fluctuates

dramatically due to flow turbulence. Some sediment transport

models incorporate this variation (e.g., van Niekerk et al.,

1992;

Bridge and Bennett. 1992) by computing a Gaussian

distribution of instantaneous effective shear stresses.

Bedload

transport module

The bed material load consists of all those grains in transport

that are directly supplied by, and interchange with, the alluvial

bed, whether traveling as bed-load or suspended load. Its

opposite is wash load. For a given flow strength and bed

material it is assumed that each size fraction will be

transported at a fixed rate, the sutn of which is called the

scdirtient transport capacity ofthe flow. Predietion ofthe bed

material load at capacity usually proceeds by computing the

bed-load and suspended load independently.

As discussed elsewhere (see entries in this volume on Sedi-

ment Transport), bed-load refers to all those sliding, rolling,

and saltating grains supported at least in part by collisions

with other grains or contact with the bed. In water, the grains

travel within a few grain diameters of the bed as a low-

concentration, dispersed, grain flow.

Grains are considered to be in motion when:

0' > 0,, (Eq. 10)

in

w

hich 0' = the dimensionless effective bed shear stress ofthe

local flow and 0,.;=the critical shields parameter for the ith

grain size and density in question. Accurate prediction of

478

NtJMERICAL MODTLS AND SIMULATION OF SFDIMFNT TRANSPORT AND DEPOSITION

bed-load fluxes depends strongly Lipon knowing these critical

shear stresses.

Research over the last two decades ((/ Koniar. 1996) shows

that:

0,,=0,.,r^

(Eq. 11

where 0c5o —the critical shields parameter of

D^o.

the median

size in the bed size distribution, /), = the grain size in question,

and m ^ 0.65 for beds coarser than sand.

Once grains are entrained, they may pass directly into the

suspended load. Grain.s are moving as bed-load when:

VI'

> Bu^' (Eq. 12]

where ir = the grain fall velocity (see entry in this volume on

grain fall veloeity), S = 0.8. and /v*' = the loeal efTective shettr

velocity.

The weight or volume transport rate of bed fractions

meeting the criteria ol' equittions 11 and 12 may be calculated

using one of many formulas (see reviews by Gomez and

Chureh. 1989: Yang and Wan. 1991). Most can be shown to

reduce to a function of the form:

e -0,,:

(Eq. 13)

where //,,= bed-load transport rate per unit width o\' the ith

fraction at capacity: a is roughly a constant, /*, = volumetric

proportion of the ith fraction in the bed, and l<b<2. Note

that as ihe various size fractions are ditlerentially entrained,

the bed size distribution evolves, thereby modifying the bed-

load transport rates (hrough (he coefficient /*,.

Suspended load transport module

The suspended load eonsists of all those grains borne alot't in

the flow by an upward-directed turbtilence momenttini flux.

Operationally. Uie suspended load consists of all moving grains

for which equation 12 is untrue. Here too, the researcher can

choo.se atnong numerous formula (see entries in this volume on

sedimenl transport). The most basic conception assumes that if

the vertical profiles of both sediment concentration C(r), and

forward velocity u{z). are known, the volumetric discharge of

suspended grains passing through a cross section of unit area

at height z is given by C{z)u{z). Integration of this quantity

over the depth yields the suspended load transport rate:

,, = / Q{z)u{z)dz

(Eq. 14]

where

/,-;

= volumetric suspended load transport rate per unit

width ofthe ilh fraction tnoving in the v-direction, and a = the

height off the bed al which a reference concentration is known.

The concentration function is defined by the Roascec/aation:

C,{z) _ Ua){h - z)

Q{a) \{z){,h-a)

[Eq. 15)

or more recently, by the van Rijn equation (van Rijn, 1984).

where ^ = the Rouse Number. In cither case, a reference

concentration C,(o). is needed for the integration. Some

researchers (e.g., van Niekerk etai, 1992) take the reference

height as the top of the rnoving bed layer and the reference

concentration as the concentration of the ith fraction in the

subjacent bed-load as defined by a fiinetion of the form given

by equation 13. Others, such as van Rijn, point out that in the

presence of bedforms another approach is needed. Van Rijn

takes the reference height as one-half the dune height or ihe

equivalent roughness height if bedform dimeitsions arc nol

known and computes the concentration at that height as a

function of excess effeelive shear stress.

The velocity profile traditionally is defined by the law of the

wall for hydraulic rough How conditions:

(Eq. 16)

where:

w*

= f]ow shear velocity;

K

= von Karinan"s constant:

and

To

= 33 percent of the equivalent roughness height of

Nikuradse.

Predictions of suspended load flux by equation 14 are

suitably accurate provided ihe concentrations do not increase

to values that dampen turbulence.

Bed module

The core of a sediment transport model is its bed module. The

bed is both a source and sink of the various size fractions in

transport and it dynamically responds lo and modifies Ihe

overlying flow field by changing its elevation and roughness.

These roles can be described by an equation accounting for the

mass fluxes of grains to and from the bed. It is a simple

statement of conservation of mass ofthe bed. often called the

Exnerequutioii.

(Eq. 17)

where: r= width of the active bed. usually assumed to be

channel width: bi= bed elevation attributable to the ith

size-density fraction:/) = bed porosity: ;*' —immersed specific

gravity of grains: (//,, + /v,) —the immersed weight lranspt)rt

rates per unit uidth of the bed-load and suspended loads:

^z,

= volumetric lateral sediment inflow per unit along-stream

distance; and it is asstimed for simplicity that the application is

ID.

Equation 17 expresses how spatial gradients in transport

rates ofthe various size fractions give rise to temporal changes

in bed elevation. If the changes in bed elevation are nonuni-

fbrtn, bed slopes and cross sectional areas evolve, thereby

changing the flow field. Note that per unit area, the relative

proportions of the b, represent the proportions of the

various size fractions in the static bed. thereby allowing

computation of a new bed grain size distribution and hydraulic

roughness.

In practice, equation 17 is applied to an upper layer of the

alluvium called the activelayer. in recognition ofthe fact that

over timcscales of minutes to hours there is a finite thickness of

alluvium exposed to the flow. The active layer may be

conceived as a layer of mixing between the traction carpet

and the static bed. The thickness ofthe active layer has been

taken variously as the height of dunes present on the bed, the

thiekness of the armor layer (and hence some multiple of a

characteristic grain size of the bed), or a function of excess

shear stress. As grains are removed from the active layer on its

upper surface, grains are added from below in proportion to

their concentrations in the subjacent layer. During deposition.

NUMERICAL MODH.S AND SIMULATION OF SFDIMENT TRANSPORT AND DEPOSITION

479

grains pass out ofthe bottom ofthe active layer in proportion

their concentrations in the layer.

Solution of equation set

The computational modules described above require initial

and boundary conditions to form a closed set of equations. In

addition, if the application involves channelized flow, either

the alongstream channel widths tnust be specified or an

additional function added to relate width to the state variables.

Initial conditions include the geometry and bed textures ofthe

geomorphic dotnain oi' interest and flow velocities and

sediment transport rates everywhere in the domain (both

usually taken to be zero for lack of better information). To

avoid errors arising frotn bogus initial conditions, it is

common practice to "spin-up" a model before interpreting

the results. Boundary conditions include tetnporally evolving

water and sediment hydrographs along upstream open

boundaries and (typically) water surface elevations along

dtiwnstream open boundaries. Lateral inflows of sediment

and water along closed boundaries also must be speeifled.

Because the equation set is analytically unsolvable. the time-

space domain is subdivided into a finite number of nodes or

elements, and solutions are obtained at discrete points in space

and discrete times. The flow chart of MIDAS (van Niekerk

elaf.

1992). provides a typical example of computational flow

Ibr a ID case (Figure Nl.^). After the user has specified the

initial and boundary information, ihe flow field at time / + St

is computed across the whole domain by some combination of

equations 1 through 6. The efTective shear stresses are

calculated next from equations 7 through 9. Starting at ihe

upstream end ofthe domain, the bed-load transport rates are

computed from equations 10 through 13. thereby providing

the reference concentrations for the suspended load computa-

tion using equations 14 through 16. After the bed material load

at node I has been computed, equation 17 is solved for ehanges

in bed elevation at that tiode arising from erosion or

deposition of each size fraction. If the tnass of any size

fraction to be eroded is greater than is available in the active

layer, then that fraction's bed-load transport rate (and

consequently its suspended load transport rate) are incremen-

tally redticed until mass is conserved. Computation proceeds

through the domain, after which the time step is incremented,

the flow field is recomputed taking into account the updated

water depths and hydraulic roughnesses, and the sedimenl

transports arc recomputed in light ofthe new flow field.

This algorithm is not the only possible comptitation method.

.Although this tmcoupled approach is the mosl common, a few

models such as CH3D-SFD (Gessler et al.. 1999) siniuha-

neously solve for all dependent variables in a fully coupled

solution. The advantage of a coupled solution is that

uncoupled models are restricted to short time steps so that

the hydrodynamic solution scheme adjusts to small changes in

the bed.

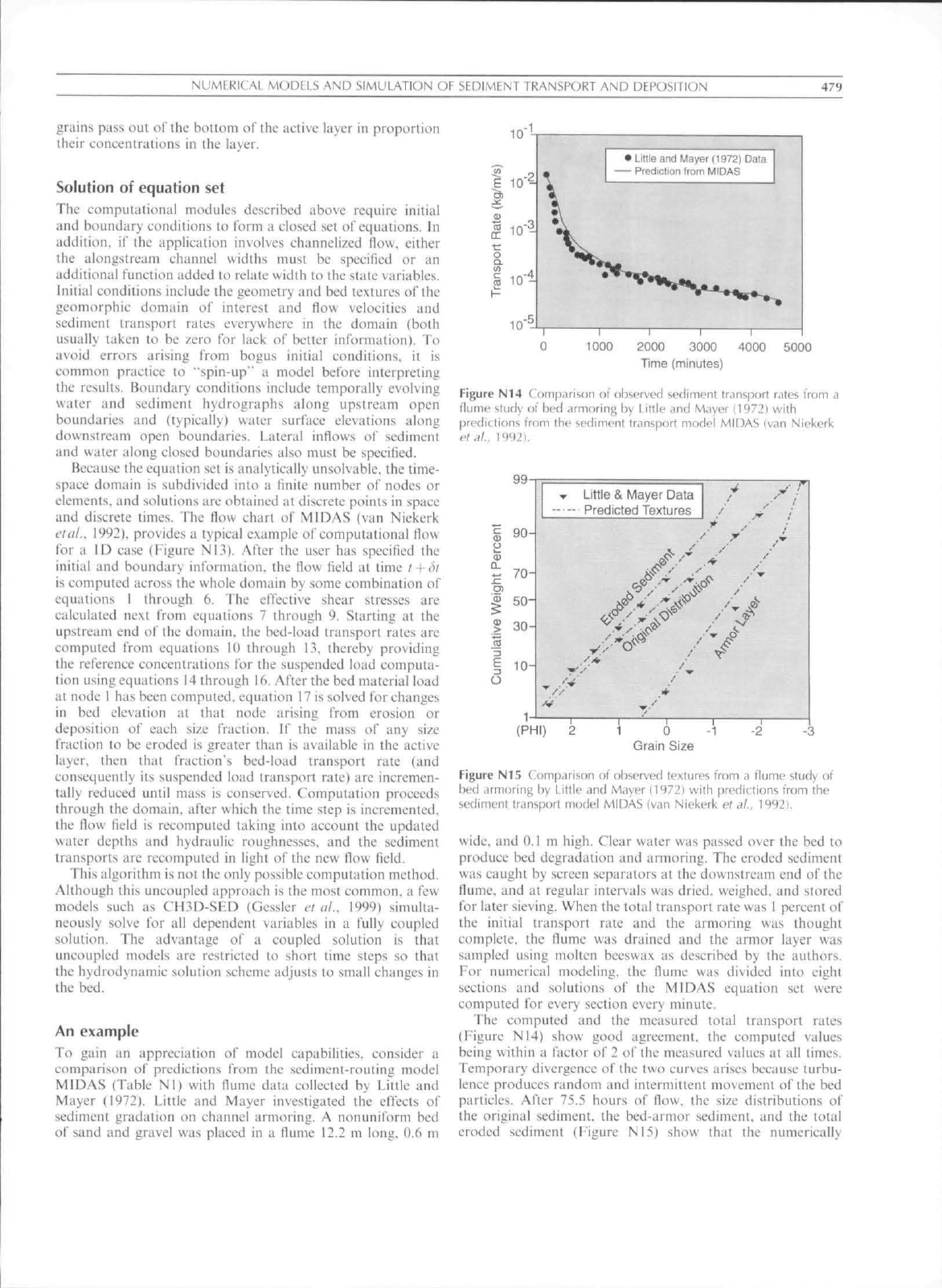

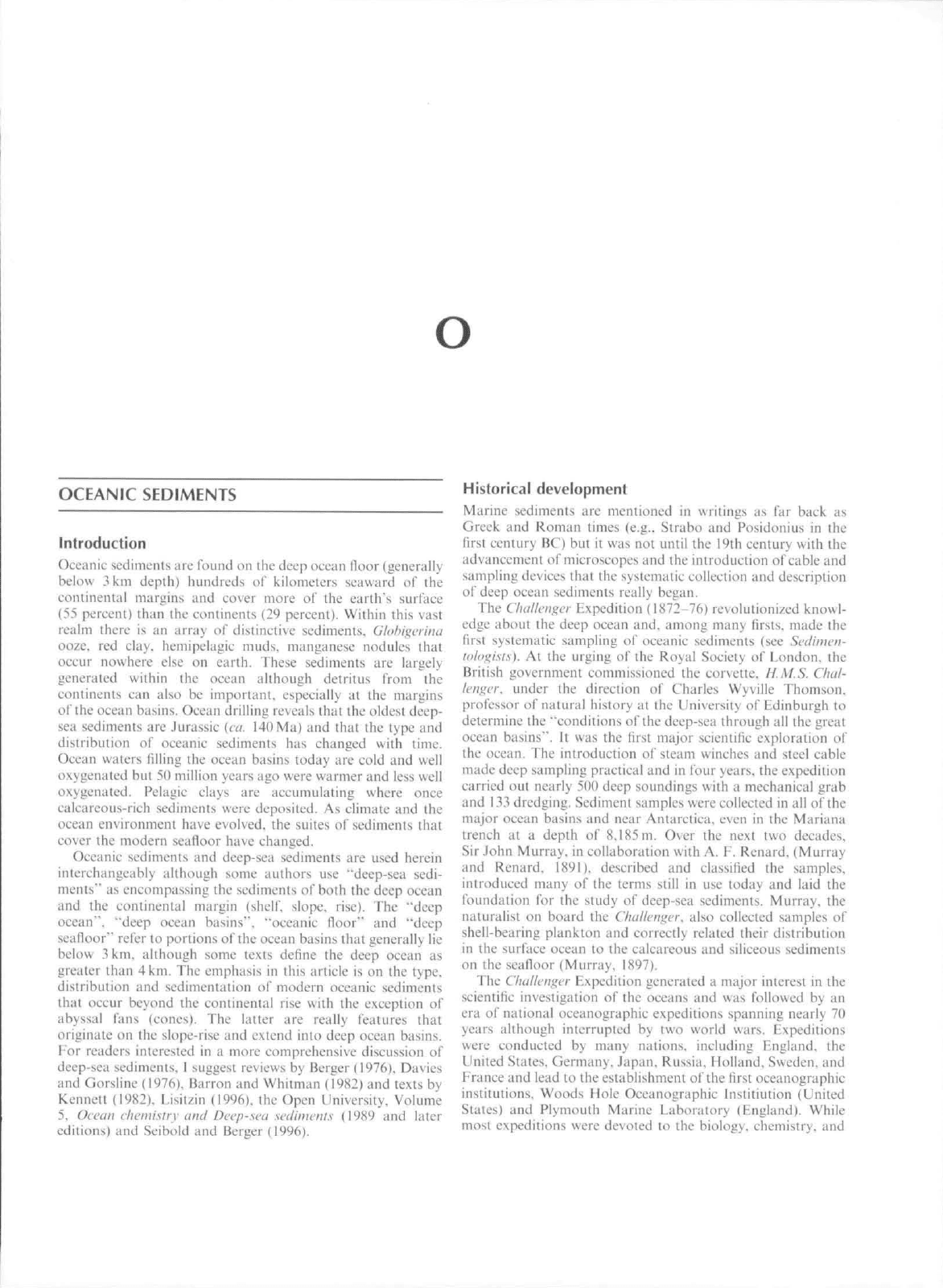

An example

To gain an appreciation of model capabilities, consider a

cotnparison of predictions from the sediment-routing model

MIDAS (Table Ni) with flume data collected by Little and

Mayer (1972). Little and Mayer investigated the effects of

sediment gradation on channel armoring. A nonuniform bed

of sand and gravel was placed in a flimie 12.2 m long. 0.6 tn

• Littie and Mayet (1972) Data

—- Prediction trom MIDAS

1000

2000 3000

Time (minutes)

4000 5000

Figure N14 Comparison of observed sediment Ifansport rates from a

flume study of bed armoring by Little antl

M,iyer

(1972) with

predictions from the sediment transport model MIDAS (van Niekerk

ct .it.. 1<)'}2I.

99-

90-

70-

^ 50-

10-

, Little & Mayer Data

Predicted Textures

'•/

(PHI)

0 -1

Grain Size

-2

-3

Figure NI5 Comparison uf observed textures from a flume study of

tied .irmoring by Little and Mayer (1972) with preHittions from the

sediment transport model MIDAS Ivan Niekerk et t)/., 1992).

wide, and 0.1 m high. Clear water was passed over the bed to

produce bed degradation and artnoring. The eroded sediment

was caught by screen separators at the downstream end ofthe

flume, and at regular intervals was dried, weighed, and stored

for later sieving. When the total transport rate was I percent of

the initial transport rate and the armoring was thought

complete, the flume was drained and the armor layer was

sampled using molten beeswax as described by the authors.

For numerical modeling, the flume was divided into eight

sections and solutions of the MIDAS equation set were

computed for every section every minule.

The computed and the measured total transport rates

(Figure N14) show good agreement, the computed values

being within a factor of 2 of the measured values at all times.

Temporary divergence o\' the two curves arises because turbu-

lence produces random and intermittent movement ofthe bed

particles. After 75.5 hours of flow, the size distributions of

the original sediment, the bed-armor sediment, and the total

eroded sediment (Figure N15) show that the numerieally

48U NUMERICAL MODELS AND SIMULATION OF SEDIMENT TRANSPORT AND DEPOSITION

simulated armor layer is slightly finer than observed, although

the difference in mean grain sizes is only 2.7 mm versus

3

mm.

The numerically simulated and physically observed grain-size

distributions of the transported sediment almost coincide.

unverified reliability". Let us hope our faith in numerical

models of sediment transport and deposition is justified.

Rudy L. Slingerland

Unresolved problems

Although mueh progress has been made in sediment transport

models, the accuracy of predictions in many applications is still

regrettable. Bedload functions are still prone to order of

magnitude errors (ef Gomez and Church, 1989; Yang and

Wan, 199!), and present formulations need to be tested in

extreme events when mueh of the sediment transport occurs in

many geomorphic systems. These errors are compounded

when computing sedimenl lltix divergenees in equation 17.

Also,

suspended load formulations break down at hyper-

concentrations such as seen in many rivers draining loess

provinces and do not yet account for the wash load. There is

also a pressing need to treat channel pattern changes and

dynamic adjustments in channel hydraulic geometries.

Seeondary Hows are commonly assumed to be negligible, yet

in natural channels, and particularly during overbank flows,

lateral gradients of fiow depth and friction factor induce

significant lateral velocity gradients. Although nol much as

been said about coastal ocean sediment transport models, a

better understanding of the basie physics of combined

oscillatory and unidirectional fiows is needed and the processes

of sediment aggregation, flocculation, and disaggregation in

marine waters must be better understood.

A final thought

Given the work yet to be done, it is sobering to realize that the

most severe test yet of numerical sediment transport modeling

is being carried out right now on the Yangtze River in China.

Construction ofthe Three Gorges Dam began iti 1994 and is

scheduled to take 20 years. It will be the largest hydroelectric

dam in the world, stretching nearly a mile across and towering

575 feet above the world's third longest river. Its reservoir will

stretch over 350 miles upstream and force the displacement of

1.2 million people. The role that nutnerical sediment transport

modeling has played in the dam's conception, feasibility

studies, and design is unprecedented and the predictions are

controversial. Physical and in particular, mathematical model-

ing of sedimentation was conducted by the Yangtze Valley

Planning Office (China) and reviewed by the Yangtze Joint

Venture {Canadian International Development Agency).

Dr Luna Leopold, a respected elder statesman of fiuvial

engineering in the United States has written, "The sedimenta-

tion conditions at various times during the first 100 years of

operation have been forecast by use of mathematical models

and physical analogues that involve many assumptions of

Bibliography

Bridge, J.S., and Bennett. S.J.. 1992. A tnode! of the entrainmenl and

transport of sediment grains of mixed sizes, shapes, and densities.

Water Resources Research. 28 (2): 3.17 363.

Einstein, H.A., and Barbarossa. N.L.. i952. River chatinel rotighness.

Transaciions

.American

Soeiety of Civil Engineers. 117: 1121 i 146.

Gessler. D.. Hall. D., Spasojevje. M., Holly. F.. Poiirtaheri. H., and

R;iphclt. N., 1999. Application of 3D mobile bed. hydrodynamic

model. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering. 125: 737 749.

Gomez. B.. iind Church, M., 1989. An iissessment ol'bed loud sediment

transport formulae for uravel bed rivers.

Water

Resources Researeh.

25:

1161-1186.

Kazemipour, A.K., and Apelt. C.J., 1983. ElTects of irregularity of

form on energy losses in open channel flow, Au.slndian CivilEngi-

neeringTransaciions. CE25: 294 299.

Komar, P.D.. 1996. Entniinmeni of sediments from deposits of tnixed

grain sizes and densities. In Carting, P.A., and Dawson, M.R.

(eds.),

.Advances

in Fluvial Dynamics and

Stratii^raphv.

New York:

John Wiley & Sons, pp. 127' IJ<I.

Lane, S.N.. 1998. Hydraulic trtodelliiig in hydrology and geomorphol-

ogy: a review of high resoltition approaches. Hydrological Pro-

cesses, 12: ll31-n5U.

Little, W.C., and Mayer, P.G., 1972. The rote of sediment gradation

on channel armoring. Puhlicaiion S'o. ERC-0672. School of Civil

Engineering in Cooperation with Environmental Research Center.

Georgia Inslitiile of Technology, Atlanta. GA. pp. I 11)4.

Nezu. !.. and Nakagawa, H., 1993.

Tiirhidence

in Open-channel Flows.

lAHR Monograph. Series A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam. 281pp.

van Niekerk, A., Vogel. K.R., Siiiigerhittd. R.l... and Bridge, J.S.,

1992.

Routing of heterogeneous size-dcnsily seditttcnts over a

moviible stream bed: model development. Journal of Hydraidie

En^-inceriiiK.

US (2): 246-262.

Paola. C, 1996. Incoherent structtire: Itirbtilence as a metaphor tor

stream braiding. In Ashworth, P.J., Bennett. S.J., Best, J.L., and

McLelland, S.J. (eds.). Coherent Flow Strucluivsin Open Channels.

Jolin Wiley & Sons. pp. 705 723.

van Rijn, L.C, 1984. Sediment transport. Part H: Stisponded load

transport. Journat ot Hydraulic En^inevrimi. 110 (11): 1613 1641.

Vogel. K.R,, v;m Niekerk.^A. Slingerland. R.L.. iind Bridge. J.S.. 1992.

Routing of heterogeneous size-density sediments over a mo\able

stream bed: model verification and testing. Journat of Ilydrauiic

Engineering. 118 (2): 263-279.

Yang, C.T., and Wan, S., 1991. Comparison of selected bed-maierial

formulas, Journal of Hydraulic Engineering. 117: 973-989.

Cross-references

DitTvision, Turbuleni

Rivers and Alluvial Fans

Sediment Flu.\es and Rates of Sedimentation

Sediment Transport by Unidirectional Water Klows

o

OCEANIC SEDIMENTS

Inlroduction

Oceanic sedimetUs are found on the deep ocean floor {generally

below 3 krn depth) htttidreds of kilometers seaward of the

conlinentitl niLtrgins itnd cover more of the earth's surface

(55 percent) than the eoiitincnts (29 percent). Within this vast

realm there is an array of distinctive sediments, Globigerina

ooze,

red elay. hcmipelagie mtids. manganese nodules that

oeeur nowhere else on earth. These sediments are largely

generated within the oeean although detritus from the

eontinents can also be important, espeeially at the margins

ofthe oeean basins. Ocean drilling reveals that the oldest deep-

sea sediments are Jurassie {ea. 140 Ma) and that the type and

distribution of oceanie sediments has changed with time.

Oeean waters tilling the ocean basins today are cold and well

oxygenated but 50 million years ago were warmer and less well

oxygenated. Pelagie clays are accumulating where once

calcareous-rich sediments were deposited. As climate and the

ocean environment have evolved, the suites of sediments that

cover the modern seafioor have changed.

Oceanic sediments and deep-sea sediments are used herein

interchangeably although some authors use "deep-sea sedi-

ments" as encompassing the sediments of both the deep ocean

and the eontinental margin

(shelf,

slope, rise). The "deep

oeean". "deep ocean basins", "oeeanie lloor" and '"deep

seafloor" refer to portions ofthe ocean basins that generally lie

below 3 km. although some texts define the deep ocean as

greater than 4 km. The emphasis in this article is on the type,

distribution and sedimentation of modern oceanie sediments

that oeenr beyond the continental rise with the e.\ception of

abyssal fans (cones). The latter are really teatures that

originate on the slope-rise and extend into deep oeean basins.

For readers interested in a more comprehensive diseussion of

deep-sea sediments.

1

suggest reviews by Bcrger (1976). Davies

and Gorsline (1976), Barron and Whitman (19S2) and texts by

Kennett (1982). Lisitzin (19%). the Open University, Volume

5.

Oeean chemistry and Deep-sea si'dimetits (1989 and later

editions) and Seibold and Berger (1996).

Historical development

Marine sediments are mentioned in writings as far baek as

Greek and Roman times (e.g.. Strabo and Posidonius in the

first century BC) but it was not until the 19th century with the

advancement of microscopes and the introduction of cable and

sampling devices that the systematic collection and description

of deep ocean sediments really began.

The Challenger Expedition (1872-76) revolutionized knowl-

edge about the deep oeean and, among many firsts, made the

first systematic sampling of oecanic sediments (see .Sedlmen-

tologi.sts).

At the urging of the Royal Soeiety of London, the

British government commissioned the corvette. H.M.S. Chal-

lenger, under the direction of Charles Wyville Thomson,

professor of natural history at the University of Edinburgh to

determine the "conditions ofthe deep-sea through all the great

oeean basins". It was the first major scientific exploration of

the oeean. The introduetion of steam winches and steel cable

made deep sampling praetical and in four years, the expedition

carried out nearly 5(H) deep soundings with a meehanieal grab

and 133 dredging. Sediment samples were collected in all ofthe

major ocean basins and near Antarctica, even in the Mariana

trench at a depth of 8,185 m. Over the next two decades.

Sir John Murray. In collaboration with A. F. Renard, (Murray

and Renard. 1891), described and classified the samples,

introduced many of the terms still in use today and laid the

foundation for the study of deep-sea sediments. Murray, the

naturalist on board the Challenger, also eollected samples of

shell-bearing plankton and eorrectly related their distribution

in the surface oeean to the calcareous and silieeous seditnents

on the seafioor (Murray. 1897).

The Challenger Expedition generated a major interest in the

seientific investigation of the oeeans and was followed by an

era of national oceanographic expeditions spanning nearly 70

years although interrupted by two world wars. Expeditions

were conducted by many nations, ineludiiig England, the

United States. Germany, Japan, Russia, Holland, Sweden, and

France and lead to theesiablishnient ofthe first oeeanographic

institutions. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institiution (United

States) and Ptytnouth Marine Laboratory (Hngland). While

most expeditions were devoted to the biology, chemistry, and

482

OCEANIC SEDIMENTS

physics of the oceans, some important advances occurred in

the study of ocean sediments. It was during the German

Southern Polar Expedition (1901-03) that the gravity corer

was invented and the first sediment eores were recovered.

By the I93()s. electronic depth sounders replaced wire

soundings to measure ocean depths and reveal the complex

bathytnetry ofthe deep ocean. This technology was first used

during the German Meteor Expeditions in the Atlantic. In

1935,

Schott (1935) in a pioneering study based on gravity

cores eollected by the Meteor, devised a means for correlating

between cores, calculating reliable rates of sedimentation and

studied the effects of the Ice Ages in the Atlantic Ocean.

One of the last major national expeditions was the Swedish

Deep Sea Expedition (1947 49) to the equatorial Pacific

Ocean. It employed the newly developed Kullcnberg piston

corer that could reeover sediment cores tens of tneters in length

and made possible the study of Pleistoeene ocean history. In

these cores, Arrenhius (1952) discovered distinct Pleistoeene

cycles in ealeiutn carbonate eontent which he related to glacial

to interglaeial variations in productivity and preservation. He

proposed that the higher earbonate content was dtie to

increased surlace productivity during glacial times, initiating

a debate about the processes which control biogenic sedimen-

tation, a debate that eontinues today (see Berger, 1992).

In 1968, the Deep Sea Drilling Projeet (DSDP) was

launehed to test the theory of continental drift by determining

the age and evolution of the oeean basins. Prior to ocean

drilling, information about deep-sea sediments was limited to

the surfaee layer penetrated by a piston eorer. a few tens of

meters. The entire inventory of pre-Quaternary deep-sea

sediments was fewer than 100 cores. In the past 34 years,

DSDP (and its successors, the Ocean Drilling Project (ODP)

and International Decade of Ocean Drilling (IDOP)) have

coileeted a vast array of information from all of the ocean

basins except the Arctic Oeean, including long cores of

sediments extending baek to the early Jurassic. These data

have significantly expanded our understanding of the oeean

basins, their origins, the sediments that fill them, life that

existed in the past and the dynamics of the interplay between

tectonics, climate and the oceans.

Classification and major types

Sediments of the deep ocean basins are termed pelagic

ipelagios = ofthi'.sea) if they originate in the ocean or heniipe-

lagie when mixed with terrigenous material derived from the

eontinent. Pelagic sedimentation involves two processes: the

packaging of biologically produced debris in the water column

and dust that falls into the ocean and its transfer to the

seafioor. Pelagic particles "rain" down from the surface. These

processes occur everywhere within the ocean.

Sedimentation ofthe terrigenous eomponent in hemipelagic

sediments involves resuspcnsion and turbidite and suspension

flows.

These proeesses move mud (silt and clay) that was

originally deposited on the continental slope into the deep

ocean where it becomes mixed with pelagic debris. While the

distinction between pelagic and hemipelagic seems obvious, in

practice it ean be difficult to determine the origins of sediment

particles because the terrigenous component in both types of

deposits is derived from the eontinents and the mineralogy and

grain size may be very similar. Determining the relative

proportion of particles that are pelagic in hemipelagic

sediments can be difficult.

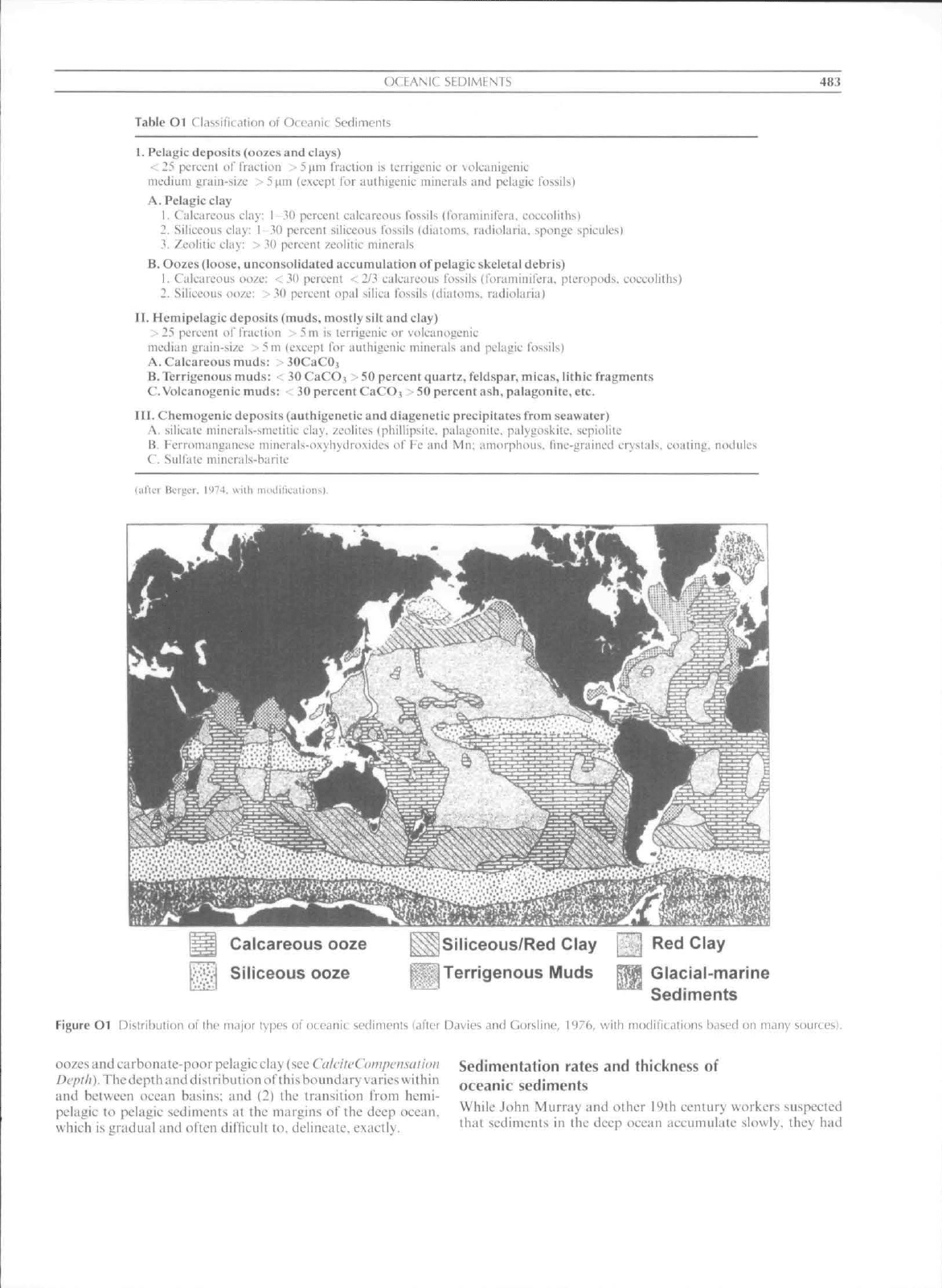

There is no single widely agreed upon classification of

oceanie sediments and different authors even use some of the

common terms differently. Two broad approaehes have been

used to classify marine sediments: descriptive, based on grain

size and composition or genetic, based on origins, or a

combination of the two. Murray and Renard (1891). for

example, used a descriptive-genetie approaeh when they coined

the terms "red clay"" and "Glohigerlna ooze"' tor common

deep-sea deposits and this approaeh is followed here in a

seheme modified from Berger (1974) (Table Ol). A useful

discussion on the philosophy of sediment classifications is

given in Davies and Gorsline (1976).

There are three kinds of sediments in the deep-sea: Terrige-

nous (or Lithogenous): detrital or elastic particles produced by

the weathering, erosion and transport of pre-existing roeks,

primarily from the eontinents and voleanie eruptions; bioge-

neoa.s: biologically produced shells or skeletons of calcium

carbonate, siliceous or ealeium phosphate, either in the water

column or on the seafioor; and, chemogenle (or hydrogenous);

primary (authigenetie) or diagenetic chemieal preeipitates

from seawater or interstitat waters, sometimes mediated by

bacteria.

Aerially and volumetrically two types of sediments dom-

inate in the deep oeean; biogenic oozes, especially ealeareous

oozes and pelagic clay (abyssal "red"" elay). Ooze is the loose,

unconsolidated aeeumulation of biogenie debris (shells of

foraminifera. diatoms, radiolaria or eoccolilhs) tisually mixed

with some elay. In the modern ocean, roughly 50 percent ofthe

seafioor is covered by foraniinit>ral-rich calcareous ooze. 37

percent by pelagic clay and 12 pereent by silieeous-rieh

sediments (Berger, 1976). All others sedimenl types equal

< I pereent (Figure Ol).

Volcanogenie materials are common in the deep sea but the

coarser-grained materials are limited to the souree area.

Voleanie ash ean be transported hundreds of kilometers from

its souree and is widely distributed in the oeean. Within the

sediments it is an important souree of silica in the formation of

zeolite and elay minerals. There arc several rare but distinet

deposits that occur in modern and ancient sediments. One of

them is cosmic dust (microtektites) partieles that survive the

trip through the atmosphere and fall into the ocean. They are

found in pelagie red clay, mostly in the southern hemisphere.

Another is laminated, diatom-rich mud that occurs in Plioeene

and Miocene deposits in the eastern equatorial Pacific (Pearee

('/ al.. 1996). Typieally such deposits are associated with

organic carbon-rich hemipelagic sediments beneath upwelling

areas in continental margins atid not the deep ocean.

Data from the ocean drilling indicate that the relative

abundance and distribution of major sediment types has

ehanged with time under the intluenee of different climate and

oceanie environments and that biogenie sediments were even

more widely distributed in the early Tertiary and Cretaceous.

The reeord of deep-sea sediments provides one of the most

important sources of information about the history of global

wind patterns, ocean fertility, ocean geochemistry and biotic

evolution.

The distribution of major sediment types in the deep ocean

can be related to three faetors: (1) distance from the continents;

(2) water depth, which infiuenees the preservation of biogenic

sediments; and (3) ocean fertility, whieh controls surfaee

productivity. There are two major sediment boundaries in the

deep ocean: (1) The Calcium Carbonate Compensation Depth

(ealcite compensation depth) that separates carbonate-rieh

(KTAMC SEDIMENTS

483

Table Ol ("l<ihsilii.tilion ot Ot eank Sedifiients

I. Pelagit; deposits (oozes and clays)

•'-

25 percent of Iractioii

•

.'i jim Irnclion is tcrrigenic or \olc;tnigciiic

nicclium graiii-si/c >

5

pm (except Ibr aLithiueiiiL' minerals and pelatiic Ibssils)

A. Pelagic clay

1.

Calcareous clay: 1-30 percent calcareous fossils (foratniitifera. coecoliihs)

2.

Siliceous chiy:

\-?iO

percent siliceous fossils (dintoms, radiolaria. sponge spieules)

3.

Zcolitic clay: > 30 pereeni zeolitic minerals

B.

Oozes (loose, unconsolidated accumulation of pelagic skeletal debris)

1.

Calcareous oo/c: <

M)

percent '. 2/3 ealcaieous fossils (foraminifera. pteropods. coeeolilh.s)

2.

Siliceous oo/e:

>

30 percent opal silica fossils (diatoms, radiolaria)

II.

Hemipelagic deposits (muds, mostly silt and clay)

> 25 pereeni ol iVaction >5m is lerrigenle or voleanogenie

median grain-si/L'

^

>m (L'xcept for aiilliigenic minerals and pelaaie fossils)

A. Calcareous muds: JOCaCOt

B.

Terrigenous muds: 30 CaCOi 50 percent quartz, feldspar, micas, lithic fragments

C.Volcanoyenic muds: • 30 percent CaCO? 50 percent ash, palagonite,etc.

III.

Chemogenic deposits (authigenetie and diagenetic precipitates from seawater)

A. silicate niiiierals-smetitic cl;!\. zeolites (phillipsile. palagonlte. puKgoskite. scpiolito

B.

ferromanganese minerals-o\yliytiro\ides of Fe and Mn: Limoiplious. fine-grained crystals, coating, nodules

C. Sulfate tnincrals-harite

(lifter

Berger.

197-1.

with

nwdificLiliiins).

••.••'•*.••

Calcareous ooze

Siliceous ooze

Siliceous/Red Clay

Terrigenous Muds

Red Clay

Glacial-marine

Sediments

Figure Ol Disiribiilion iil ihc major lypes of oceanic seclimenls uitter Davies and Corsline, T,)76, with modilications based on miiny S

oozes and citrbtJiiiitc-poor pelagic cliiy (sec CaleileCoiiipeti.salioti

Depth).

The dcpt hand distribution of tit

is

boundary varies within

and between ocean basins; atid (2) the Iransition from lietni-

pclitgic to pelagic sediments at the margins ofthe deep ocean.

v\hich is gradual and often difficult to. delineate, exactly.

Sedimentation rates

and

thickness

of

oceanic sediments

While .lohn Murray

and

other

19th

century workers suspected

that sediments

in the

deep oceitn accutmilale

slowly,

they

had

484 OCEANIC SEDIMENTS

no means by which lo access rates of sedimentation and it

remained for Schott (1935) to provide the tirst quantitative

estimates by using the oecurrence of a distinctive tropical

foraminifer. GloborufaliamenanlH. During glacial periods, this

species is absent in cores in the central Atlantic Ocean and its

first appearance coincides with the base of the Holocene. Using

the age of the biise of tlic Holocene (determined on land) as a

datum, ho calcuhitcd thai the calcareous oozes in the Atlantic

had accumulated at rates ol" several centimeters per thousand

years.

Today a variety of dating techniques (radiocarbon.

Uranium series, etc.) are available to determine the rates of

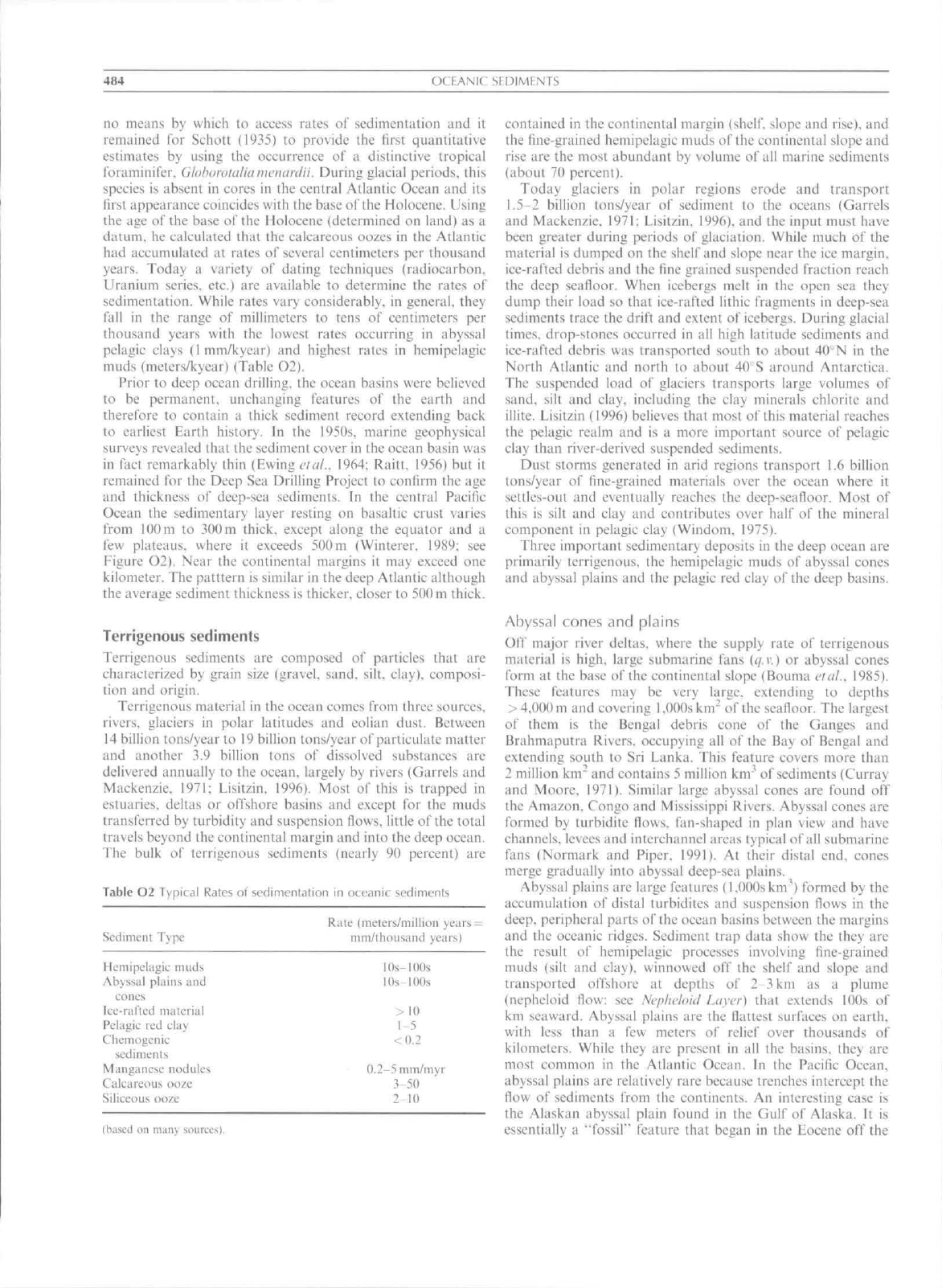

sedimentation. While rates vary considerably, in general, they

fall in the range of millimeters to tens of centimeters per

thousand years with the lowest rates occurring in abyssal

pelagic clays (lmm/kyear) and highest rates in hemipelagic

muds (meters/kyear) (Table 02).

Prior to deep ocean drilling, the ocean basins were believed

to be permanent, unchanging features of the earth and

therefore to contain a thick sediment record extending back

to earliest Earth history. In the l95Us, marine geophysical

surveys revealed that the sediment cover in the ocean basin was

in fact remarkably thin (Ewing cm/.. 1964: Raitl. 1956) but it

remained for the Deep Sea Drilling Project to confirm the age

and thickness of deep-sea sediments. In Ihe central Pacific

Ocean the sedimentary layer resting on basaltic crust varies

from lOOm to 300m thick, except along the equator and a

few plateaus, where it exceeds 5()()m (Winterer, 19S9; see

Figure O2). Near the continental margins it may exceed one

kilometer. The patttern is similar in the deep Atlantic although

the average sediment thickness is thicker, closer to 500 m thick.

Terrigenous sediments

Terrigenous sediments are composed of particles that are

characterized by grain size (gravel, sand, silt, clay), composi-

tion and origin.

Terrigenous material in the ocean comes from three sources.

rivers,

glaciers in polar latitudes and eolian dust. Between

14 billion tons/year lo 19 hillion tons/year of particulate matter

and another 3.9 billion tons of dissolved substances are

delivered annually to the ocean, largely by rivers (Garrels and

Mackenzie. 1971; Lisitzin. 1996). Most of this is trapped in

estuaries, deltas or offshore basins and except I'or the muds

transferred hy turbidity and suspension flows, little of the total

travels beyond the continental margin and into the deep ocean.

The bulk of terrigenous sediments (nearly 90 percent) are

Table O2 TypJc.il Rales of sfdimenlalion in ocwnic sediments

Sedimetil Type

Rate (ineicrs/millioii years

mm/thousand years)

Ilumipelagic muds

Abyssiil plains and

cones

Ice-rafled malerial

Pelagic red clay

Chemogenic

sedlmenls

Manganese nodules

Calcareous ooze

Siliceous ooze

lIls-KIOs

lOs 100s

1-5

<0.2

0.2-5 mni/myr

3-50

2-10

(based on manv SI

contained in the continental margin

(shelf,

slope and rise), and

the fine-grained hemipelagic muds of the continental slope and

rise are the most abundant by volume of all marine sediments

(about 70 percent).

Today glaciers in polar regions erode and transport

1.5 2 billion tons/year of sediment lo the oceans (Garrels

and Mackenzie. 1971; Lisitzin, I99fi), and the input must have

been greater during periods of glaciation. While much ol" the

material is dumped on the shelf and slope near the ice margin,

ice-rafted debris and the fine grained suspended fraction reach

the deep seafloor. When icebergs melt in the open sea they

dump their load so that ice-rafted lithic fragments in deep-sea

sediments trace the drift and extent of icebergs. During glacial

times,

drop-stones occurred in ail high latitude sediments and

iee-rafted debris was transported south to about 40' N in the

North Atlantic and north to about 40 S around Antarctica.

The suspended load of glaciers transports large volumes of

sand, silt and clay, including the clay minerals chlorite and

illite.

Lisitzin (1996) believes that most of this material reaches

the pelagic realm and is a more important source of pelagic

clay than river-derived suspended sediments.

Dust storms generated in arid regions transport 1.6 billion

lons/ycar of fine-grained materials over the ocean where it

settles-out and eventually reaches the decp-seafloor. Most of

this is silt and clay and contributes over half of the mineral

component in pelagic clay (Wiiidom. 1975).

Three important sedimentary deposits in the deep ocean are

primarily terrigenous, the hemipelagic muds of abyssal cones

and abyssal plains and the pelagic red clay of the deep basins.

Abyssal cones and plains

Ofl'

major river deltas, where the supply rate of terrigenous

material is high, large submarine fans

((/.

r.) or abyssal cones

form at the base of the continental slope (Bouma clul.. 1985).

These features may be very large, extending to depths

> 4,000 m and covering

1,0()0s

km' of the seafioor. The largest

of them is the Bengal debris cone of the Ganges and

Brahmaputra Rivers, occupying all of the Bay of Bengal and

extending south lo Sri Lanka. This feature covers more ihan

2 million km" and contains 5 million km of sediments (Curray

and Moore, 1971). Similar large abyssal cones arc found olT

the Amazon. Congo and Mississippi Rivers. Abyssal cones are

t\-)rmed by turbidiie Hows, fan-shaped in plan view and have

channels, levees and interchannel areas typical of all submarine

fans (Normark and Piper. 1991). At their distal end, cones

merge gradually into abyssal deep-sea plains.

Abyssal plains are large features (LOOOskm"*) formed by the

accumulation of distal turbidites and suspension Hows in the

deep,

peripheral parts of the ocean basins between the margins

and the oceanic ridges. Sediment trap data show the they are

the result of hemipelagic processes involving fine-grained

muds (silt and clay), winnowed off the shelf and slope and

transported offshore at depths of 2

3

km as a plume

(nephcloid flow: see Ncphehml Layer) that extends I(10s of

km seaward. Abyssal plains are the flattest surfaces on earth,

with less than a few meters of relief over thousands of

kilometers. While the\ are present in all the basins, they are

most common in the Atlantic Ocean. In the Pacific Ocean,

abyssal plains are relatively rare because trenches intercept the

flow of sediments from the continents. An interesting case is

the Alaskan abyssal plain found in the Gulf of Alaska. It is

essentially a "fossil"' feature that began in the Eocene off the