Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MIXED SILICICLASTIC AND CARBONATE SEDIMENTATION

445

Punctuated and facies mixing are the most prevalent, and

both will lead to the lateral mixing of coeval juxtaposed

environments, producing lateral interfingering of elastics and

carbonates. Spatial mixing invokes local autocyelic processes,

and thus occurs along a timeline in an ancient deposit. Spatial

mixing requires no changes in relative sea-level.

Holocene examples that are affected by spatial mixing

include: (a) humid fluvio-deltaic systems proximal to a

carbonate

shelf,

such as the nearshore clastic belt and offshore

barrier reef of the Belize shelf (Wantland and Pusey, 1975),

and the northeastern Australian shelf and offshore Great

Barrier Reef (Maxwell and Swinchatt, 1970; Flood and Orme,

1988);

(b) Arid eolian dunes proximal to carbonate ramp

system, such as along the leeward southeast coast of the Qatar

Peninsula in the Persian Gulf (Shinn, 1973); (c) the deep axial

trough of Persian

Gulf,

where fine-grained elastics (clays and

silts) from the Tigris-Euphrates delta accumulate adjacent to

fine-grained carbonates of the Persian Gulf carbonate ramp

system (Purser, 1973). Ancient examples include Cambrian

ramp-to-deeper shale shelf transitions in the Upper Cambrian

intra-shelf basin of the Virginia Appalachians (Markeilo and

Read, 1981), and the Upper Musehelkalk (Triassic) outer ramp

deposits of the Catalan Basin (Spain; Calvet and Tucker,

1988),

among others (Houlik, 1973; Mount, 1984; Brett and

Baird, 1985; Grotzinger, 1986; Sonnenfeld and Cross, 1993;

Adams and Grotzinger, 1996; Cowan and James, 1996).

Temporal variations in environments or

evolution in sedimentation

Over geologic time, mixtures may occur as a result of relative

sea-level change and/or variations in sediment supply, which

causes vertical variations in the stratigraphic succession of

facies.

The concept of "cyclic and reciprocal sedimentation"

(Van Siclen, 1958; Wilson, 1967; Silver and Todd, 1969;

Meissner, 1972) which invokes changes in relative sea level was

developed to explain the origin of mixed clastic-carbonate

shelf-to-basin cyclic deposits. This model suggests that

carbonate sedimentation dominates during relative sea-level

highstands and rises in sea-level, when elastics are trapped

updip in flooded fluvial valleys and narrow clastic shelves while

the carbonate factory is fully operational. Additionally, during

such highstands, rates of carbonate sedimentation (between

20 cm to

30

cm/1000 years in lagoons to greater than

1

m/1000

years in reefs and shoals) are sufficient to keep pace with

typical background subsidence rates such that the subtidal

factory outeompetes any clastic influx. Shelfal carbonate

deposits are typically thick and the coeval carbonate basin is

starved and only thin carbonate deposits are preserved.

Clastic sedimentation dominates during lowstands when

carbonate shelves are subaerially exposed and thus largely shut

down. During a relative fall in sea-level, widespread braided

fluvial systems, shallow deltas or nearshore stiallow marine

elastics may migrate across the shelf completely and ultimately

source deep-water clastic deposits (Van Siclen, 1958; Wilson,

1969;

Meissner, 1972; Rankey etal., 1999), or elastics may

migrate laterally by longshore prcesses. During true lowstands,

fluvial-deltaic systems may incise the antecedent shelf (e.g., the

Pleistocene of Belize, Choi and Ginsburg, 1982) and funnel

clastic sediments to point-sourced submarine canyons into the

basin in humid climates, or in arid climates, eolian dunes may

migrate across subaerially deflated carbonate shelves, often

truncating older carbonate features (Goldhammer etal., 1991;

Borer and Harris, 1991; Atchley and Loope, 1993). During

such lowstands, the subaerially exposed carbonate shelf may

be karstified and often completely by-passed such that clastic

material is deposited on adjacent slopes and basinal areas as

onlapping sheets, wedges and fans that terminate against the

defunct carbonate slope, for example the Upper Permian

Capitan depositional system of west Texas and New Mexico

(Bebout and Kerans, 1993; Tinker, 1998). Such basinal

deposits may be then subject to reworking by contour-hugging

bottom currents. The cyclic and reciprocal model further

suggests that lowstand shelfal elastics will be thin and coeval

basinal elastics (submarine fans, turbidites) will be much

thicker. However, the height and steepness of the underlying

carbonate slope is an important consideration in determining

the character of any lowstand clastic sand body. Alternatively,

if an updip clastic source is limited, basinal settings may

receive little or no clastic material and only record the

shutdown of the carbonate platform in the form of submarine

diastems (e.g., mineralized, cemented hardgrounds).

The character of the lowstand clastic sediments reflects

both proximity to the source area and depth of deposition.

For example in the late Devonian of the Canning Basin

(western Australia), Southgate etal. (1993) record tiie evol-

ution of several Frasnian-Fammenian "third-order" deposi-

tional sequences whereby the shelfal carbonates are completety

bypassed. Within the basin, however, there exist several

sequences of lowstand elastics each composed of basin-floor

fans,

slope fans, and prograding complexes, which overall

form a fining-upward trend from basal coarse elastics to fine-

grained mudstone and shales vertically within a particular

lowstand. This grain-size trend is interpreted to depict initial

stream rejuvenation upon initial subaerial shutdown of the

carbonate

shelf,

followed by subsequent waning of coarse

proximal sediment supply as renewed transgression of the shelf

occurred.

An unequivocal and detailed example of mixed clastic-

carbonate sedimentation driven by sea-level changes is

provided by the Quaternary reefs in the southernmost Belize

iagoon (Choi and Ginsburg, 1982). During the last glacial

maxima, eustatic sea-level was about

120

m beneath its present

day level, exposing and karstifying much of the Belize

carbonate

shelf.

As coastal rivers advanced seaward onto the

shelf,

they created morphological features including fluvial and

submarine channels, fluvial channel bars, levess and deltaic

lobes.

Subsequently, when eustatic sea-level rose, such clastic

features with positive morphologic relief served as nueleation

sites and nodes for the initial development of Holocene reefs

and other biogenic carbonates. Another example, provided

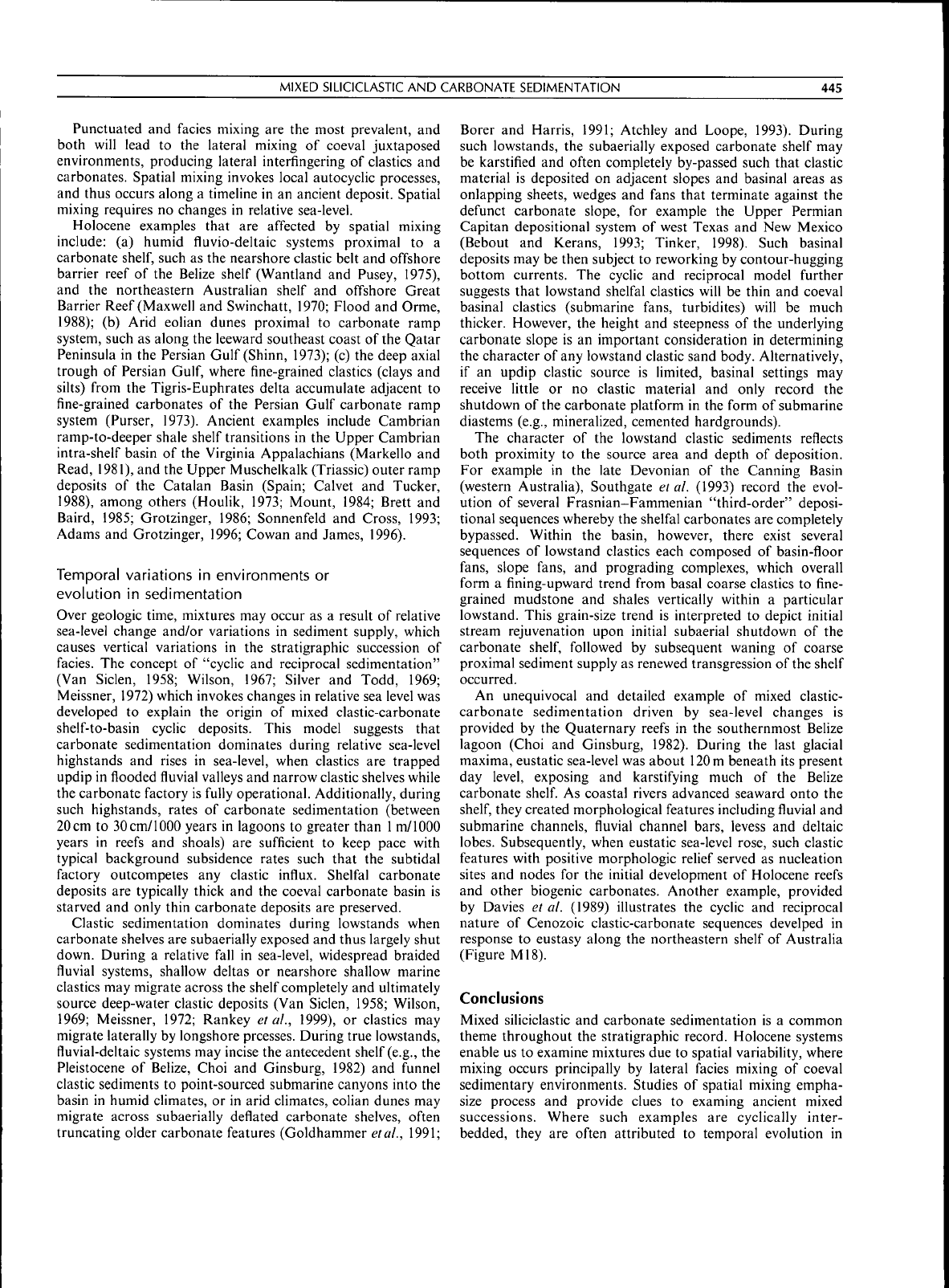

by Davies et al. (1989) illustrates the cyclic and reciprocal

nature of Cenozoic clastic-carbonate sequences develped in

response to eustasy along the northeastern shelf of Australia

(Figure Ml8).

Conclusions

Mixed siliciclastic and carbonate sedimentation is a common

theme throughout the stratigraphic record. Holocene systems

enable us to examine mixtures due to spatial variability, where

mixing occurs principally by lateral facies mixing of coeval

sedimentary environments. Studies of spatial mixing empha-

size process and provide clues to examing ancient mixed

successions. Where such examples are cyclically inter-

bedded, they are often attributed to temporal evolution in

446

MIXED SILICICLASTIC AND CARBONATE SEDIMENTATION

(A) High Sea Level Stage

Sea

Level

Lagoonai Carbonates

Clastic Dominated

Carbonate Dominated

Slope

Facies

(B) Low Sea Level Stage

Subaeriaiiy-Exposed

Fioodplain Deposits

Reef...,

SheifEdge

Fan Deita

Sea Level

Clastic Dominated

Figure M18 Schematic sections showing high (A) and low (B) sea-level control on the stratigraphic evolution and sedimentary geonnetry of

shelf facies in the central Great Barrier Reef province. Note the predominance of siliciclastic facies in the lowstand. Modified from Davies et al.

(1989).

sedimentation, induced by sea-tevel changes arid/qi- variations

in sediment supply, causing a vertical variatior) in \hp

stratigraphic succession. Many, if not most, ancient mixed

successions can be interpreted as examples of cyclic and

reciprocal sedimentation, controlled by cyclic variations in

relative sea-level.

Robert K. Goldhammer

Bibliography

Adams, R.D., and Grotzinger, J.P., 1996. Lateral continuity of facies

and parasequences in Middle Cambrian platform carbonates,

Carrara formation, Southeastern California, USA. Journal of

Sedimentary Researeh, 66: 1079-1090.

Aitken, J.D., 1978. Revised models for depositional grand cycles,

Cambrian of the southern Rocky Mountains, Canada. Bulletin of

Canadian Petroleum Geology, 26: 515-542.

Atchley, S.C, and Loope, D.B., 1993. Low-stand aeolian influence on

stratigraphic completeness: upper member''of "'ihe Hermosa

Formation (latest Carboniferous), southeastern Utah, USA; In

Pye,

K., and Lancaster, N. (eds.), Aeolian Sediments, Aneient and

Modern. International Association of Sedimentologists, Special

Publication, 16, pp. 127-149.

Bebout, D.G., and Kerans, C, 1993. Guide

to the

Permian Reef Geology

Trail,

MeKittriek Canyon, Guadalupe Mountains National

Park,

West

Texas. Texas Bureau of Economic Geology, Guidebook 26.

Borer, J.M., and Harris, P.M., 1991. Lithofacies and cyelicity of the

Yates Formation, Permian Basin: implications for reservoir

heterogeneity.

A^merican

Association of Petroleum

Geologists

Bulletin,

I5:126-n'9. ' '

Brett,' C.E., and Baird, G.C, 1985. Carbonate-shale cycles in the

Middle Devonian of New York: an evaluation of models for the

origin of limestones in terrigenous shelf sequences. Geology, 13,

324-327.

Budd, D.A., and Harris, P.M. (eds.), 1990. Carbonate-Silieielastic

Mixtures. SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology), Reprint

Series Number 14.

Byers,

C.W., and Dott, R.H. Jr., 1981. SEPM research conference on

modern shelf and ancient cratonic sedimentation—the orthoquart-

zite-carbonate suite revisited. Journal of Seditnentary Petrology, 51:

329-346.

Calvet, F., and Tucker, M.E., 1988. Outer ramp cycles in the Upper

Musehelkalk of the Catalan Basin, northeast Spain. Sedimentary

Geology, 57: 185-198.

Choi, D.R., and Ginsburg, R.N., 1982. Siliciclastic foundations

of quaternary reefs in the southernmost Belize lagoon,

British Honduras. Geological Society of Ameriea Bulletin, 93:

116-126.

Chow, N., and James, N.P., 1987. Cambrian grand cycles: a northern

Appalehian perspective.

Geologieal

Soeiety of Atnerica Bulletin, 98:

418-429.

Cowan, C.A., and James, N.P., 1993. The interactions of sea-level

change, terrigenous-sediment influx, and carbonate productivity as

controls on the Upper Cambrian grand cycles of western New-

foundland, Canada. Geologieal Soeiety of Ameriea Bulletin, 105:

1576-1590.

Cowan, CA., and James, N.P., 1996. Autogenic dynamics in

carbonate sedimentation: meter-scale, shallowing-upwards cycles.

Upper Cambrian, western Newfoundland, Canada. Ameriean

Journal of Seienee, 296: 1175-1207.

MIXED-LAYER CLAYS

447

Davies,

P.J.,

Symonds, D.A., Feary, D.A.,

and

Pigram,

C.J.,

1989.

The

evolution

of the

carbonate platforms

of

northeast Australia.

In

Crevello,

P.D.,

Wilson,

J.L.,

Sarg,

J.F., and

Read,

J.F.

(eds.).

Controls

on

Carbonate Platform

and

Basin Development, SEPM

(Society

for

Sedimentary Geology), Special Publication,

44,

pp.

233-258.

Demicco,

R.V., and

Hardie,

L.H., 1994.

Sedimentary structures

and

early diagenetic features

of

shallow marine carbonate deposits.

Controls

on

Carbonate Platform

and

Basin Development. SEPM

(Society

for

Sedimentary Geology), Atlas Series

No. 1.

Dolan,

J.F., 1989.

Eustatic

and

tectonic controls

on

deposition

of

hybrid siliclastic/carbonate basinal cycles: discussion with exam-

ples.

Atnerican A.'isociation

of

Petroleum Geologists Buttetin.

73:

1233-1246.

Doyle,

L.J., and

Roberts,

H.H.

(eds.),

1988.

Carbonate-Clastic;

Transitions. Developments

in

Sedimentology 42. Elsevier.

Driese,

S.G., and

Dott,

R.H., 1984.

Model

for

sandstone-

carbonate "cyclothems" based

on

upper member

of

Morgan

Formation (Middle Pennsylvanian)

of

northern Utah

and

Color-

ado.

Ameriean Assoeiation

of

Petroleum Geologists Bulletin,

68:

574-597.

Duff,

P.Mcl.D., Hallam,

A., and

Walton,

E.K.,

1967. Cyelie Sedimen-

tation. Developments

in

Sedimentology

10.

Elsevier.

Flood,

P.G., and

Orme,

G.R., 1988.

Mixed siliciclastic/carbonate

sediments

of the

Northern Great Barrier Reef Province,

In

Doyle,

L.J., and

Roberts,

H. H.

(eds.),

1988,

Carbonate-Ckmie

Transitions. Developments

in

Sedimentology

42.

Elsevier.

pp.

175-206.

Goldhammer,

R.K.,

Oswald,

E.J., and

Dunn,

P.A., 1991. The

hierarchy

of

stratigraphic forcing:

an

example from Middle

Pennsylvanian shelf carbonates

of the

Paradox Basin.

In

Franseen,

E.K.,

Watney,

W.L.,

Kendall,

St,

G.C.C., Ross,

W.

(eds.).

Sedimentary Modelitig: Computer Sitnulations

and

Methods

for Itnproved Paratneter Definition. Kansas Geological Survey,

Special Publication, 233,

pp.

361-413.

Goldhammer,

R.K.,

Lehmann,

P.J., and

Dunn, P.A., 1993.

The

origin

of high frequency platform carbonate cycles

and

third-order

sequences (Lower Ordovician

El

Paso Group, West Texas);

constraints from outcrop data

and

stratigraphic modeling. Journal

of Sedimentary Researeh, 63: 318-359.

Grotzinger,

J.P., 1986.

Cyelicity

and

paleoenvironmental dynamics,

Rocknest platform, northwest Canada. Geologieal Soeietv

of'

America Bulletin,

97:

1208-1231.

Houlik,

C.W., 1973.

Interpretation

of

carbonate-detrital silicate

transitions

in the

Carboniferous

of

western Wyoming. Ameriean

A.'isoeiation

of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin,

57:

498-509.

Kerans,

C, and

Tinker,

S.W.,

1997. Sequenee stratigraphy and charac-

terization of carbonate reservoirs. SEPM (Society

for

Sedimentary

Geology), Short Course Notes

No. 35,

130pp.

Lomando,

A.J., and

Harris,P.M. (eds.), 1991. Mixed Carbonate—Sili-

eiclastie Sequenees. SEPM (Society

for

Sedimentary Geology),

Core Workshop

15,

568pp.

Markeilo,

J.R., and

Read, J.F., 1981. Carbonate ramp-to-deeper shale

shelf transitions

of an

Upper Cambrian intrashelf basin, Noli-

chucky Formation, southwest Virginai Appalachians. Sedimentol-

ogy,

28:

573-598.

Maxwell, W.G.H.,

and

Swinchatt,

J.P., 1970.

Great Barrier

Reef-

regional variation

in a

terrigenous-carbonate province. Geologieal

Soeiety of Ameriea Bulletin, 81: 691-724.

Meissner, F.F., 1972. Cyclic sedimentation

in

Middle Permian strata

of

the Permian Basin.

In

Elam,

S.G., and

Chuber,

S.

(eds.), Cyelie

Sedimentation

in the

Permian Basin.

2nd

edn. West Texas Geological

Society, Publication, 72-60,

pp.

203-232.

Mount,

J.M.,

1984. Mixing

of

siliciclastic

and

carbonate sediments

in

shallow shelf environments. Geology, 12: 432-435.

Osleger,

D.A., 1991.

Subtidal carbonate cycles: implications

for

allocyclic versus autocyelic controls. Geology, 19: 917-920.

Purser,

B.H.

(ed.), 1973. The Persian Gulf Springer Verlag.

Rankey,

E.C.,

Bachtel,

S.L., and

Kaufman,

J., 1999.

Controls

on

stratigraphic architecture

of

icehouse mixed carbonate-siliciclastic:

a case study from

the

Holder Formation (Pennsylvanian,

Virgilian), Sacramento Mountains,

New

Mexico.

In

Harris,

P.M.,

Sailer,

A.H., and

Simo, J.A.T. (eds.). Advances

in

Carbonate

Sequenee Stratigraphy: Applieation

to

Reservoirs, Outerops,

and

Models. SEPM (Society

for

Sedimentary Geology), Special

Pub-

lication, 63,

pp.

127-150.

Read,

J.F., and

Goldhammer,

R.K., 1988. Use of

Fischer plots

to

define third-order sea-level curves

in

Ordovician peritidal cyclic

carbonates, Appalachians. Geology,

16:

895-899.

Sarg,

J.F., 1988.

Carbonate sequence stratigraphy.

In

Wilgus,

S.,

Hastings

B.S.,

Kendall

St, G.C,

Posamentier,

H.W.,

Ross,

C.A.,

and

Van

Wagoner,

J.C.

(eds.).

Sea

Level Changes—An Integrated

Approaeh. SEPM (Society

for

Sedimentary Geology), Special

Publication,

43, pp.

155-181.

Shinn,

E.A.,

1973. Sedimentary accretion along

the

leeward,

SE

coast

of Oatar Peninsula, Persian

Gulf.

In

Purser,

B.H.,

(ed.). The Per-

sian Gulf Springer Verlag,

pp.

199-210.

Silver,

B.A., and

Todd,

R.G., 1969.

Permian cyclic strata, northern

Midland

and

Delaware basins, west Texas

and

southeastern

New

Mexico. American Assoeiation of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin,

53:

2223-2251.

Sonnenfeld, M.D.,

and

Cross, T.A., 1993. Volumetric partitioning

and

facies differentiation within

the

Permian Upper

San

Andres

Formation

of

Last Chanee Canyon, Guadalupe Mountains,

New

Mexico.

In

Loucks,

R.G., and

Sarg,

J.F.

(eds.). Carbonate

Sequenee Stratigraphy: Reeent Developments

and

Applieations.

American Association

of

Petroleum Geologists Memoir,

57,

pp.

435-474.

Southgate,

P.N.,

Kennard,

J.M.,

Jackson,

M.J.,

O'Brien,

P.E., and

Sexton,

M.J., 1993.

Reciprocal lowstand clastic

and

highstand

carbonate sedimentation, subsurface Devonian Reef Complex,

Canning Basin, Western Australia.

In

Loucks, R.G.,

and

Sarg,

J.F.

(eds.).

Carbonate Sequenee Stratigraphy: Reeent Developments

and

Applieations, American Association

of

Petroleum Geologists

Memoir,

57, pp.

157-179.

Tinker,

S.W., 1998.

Shelf-to-basin facies distribution

and

sequence

stratigraphy

ofa

steep-rimmed carbonate margin: Capitan deposi-

tional system. MeKittriek Canyon,

New

Mexico

and

Texas.

Journal of Sedimentary Research,

68:

1146-1175.

Van Siclen,

D.C., 1958.

Depositional topography—examples

and

theory. Atnerican Association

of

Petroleum Geologists Bulletin,

42:

1897-1913.

Walker, R.G.,

and

James, N.P. (eds.), 1992. Eacies Models: Response to

Sea Level Change, Geological Association

of

Canada.

Wantland,

K.F., and

Pusey,

W.C. Ill

(eds.),

1975.

Belize

shelf-

Carbonate Sediment.'!, Clastie Sediments,

and

Ecology. American

Association

of

Petroleum Geologists Studies

in

Geology

2,

312pp.

Weller, J.M., 1930. Cyclical sedimentation

of

the Pennsylvanian period

and

its

significance. Journalof Geotogy.

38:

97-135.

Wilson,

J.L., 1967.

Cyclic

and

reciprocal sedimentation

in

Virgilian

strata

of

southern

New

Mexico.

Geologic

Society of Ameriea Bulle-

tin,

78:

805-818.

Wilson,

J.L., 1975.

Carbonate Eacies

in

Geologic History, Springer-

Verlag.

Yang,

W., 1996.

Cycle symmetry

and its

causes, Cisco Group

(Virgilian

and

Wolfcampian), Texas. Journal

of

Sedimentary

Researeh,

66:

1102-1121.

Cross-references

Facies Models

Neritie Carbonate Depositional Environments

Sands

and

Sandstones

MIXED-LAYER CLAYS

Clay mineral crystals contain from

a few to few

hundred

silicate layers

(1:1 or

2:1, dioctahedral

or

trioctahedral,

see

figure

I in

Illite Group

Minerals), spread over tens

to

thousands

448

MIXED-LAYER CLAYS

of nm in the a* and b* crystallographic directions and stacked

parallel in the c* direction. Layers are either electrically neutral

or they have a negative charge, resulting from isomorphous

substitutions within the tetrahedral and/or octahedral sheet.

The charged layers are bounded by interlayer cations or sheets

of interlayer hydroxide. If the interlayer cations are hydrated,

the interiayer (smectite or vermiculite type) has swelling

properties (i.e., it may change thickness and accept organic

molecules). Clay crystals may contain non-identical layers and/

or interlayers, that is, be mixed-layered (interstratified).

Mixed-layering is defined as random and characterized by

the ordering parameter (Reichweite) RO if there is no preferred

sequence in stacking of layers (or interlayers) A and B. tf some

sequences are privileged, such mixed-layering is called ordered

(Rl if ABAB..., R2 if AABAAB... etc.; details in Moore and

Reynolds, 1997). If only one type of sequence is present, the

mineral is called regular. Such minerals (only of RI type) exist

in nature; they are given separate names, and their origin is

explained by different mechanisms. Other names of mixed-

layer clays are combinations of the components' names, for

example, illite-smectite.

Mixed-layering is identified and quantified by means of

X-ray diffraction (XRD), supplemented by chemical analysis

and electron microscopy. OOI XRD reflections of mixed-layer

minerals appear between positions of corresponding reflec-

tions of pure components. The nature of layers and swelling

interlayers is revealed by XRD of specimens heated or

treated with different exchange cations or organic solvents.

Computer modeling of such diffraction effects is used to

measure layer ratios and ordering (Moore and Reynolds,

1997).

tf the imaging conditions are properly selected, and a

distinctive and stable under vacuum spacing of the swelling

interlayer achieved, the nature of layers can be identified in

transmission electron microscope by measuring the layer

spacings and obtaining AEM chemical analyzes of the bulk

crystal.

Mixed-layer clays with smectitic interlayers can be separated

in dilute suspensions, by infinite osmotic swelling along these

interlayers, into individual layers or blocks of layers bounded

by stable interlayers (fundamental particles, see figure 1 in

Illite Group

Minerals). When such separation is stabilized in the

solid state, the mixed-layering diffraction effect is destroyed

and such blocks of layers (individual layers do not diffract

coherently) can be studied by XRD, as if they were pure end

member clays (Ebert etal., t998).

Mixed-tayer clay minerals are most often intermediate

products of reactions altering pure end-member clays.

Mixed-layer minerals occur in natural environments ranging

from surface to low-grade metamorphic and hydrothermal

conditions (see review by Srodoti, 1999). The majority of

mixed-layer clays have been synthesized in the laboratory.

Most often, the mixed-layering is 2-component, but more

complicated interstratifications have also been documented.

Mixed-layer clays are either di or trioctahedral; di/trioctahe-

dral interstratifications are very rare. Most mixed-layer clays

contain swelling interlayers of smectite type (typical of

diagenetic alteration) or vermiculite type (typical of weathering

alteration). In general, the weathering reactions producing

mixed layering are reversals of the corresponding high

temperature reactions, but the reaction paths are quite

different. Solid-state transformation and dissolution/crystal-

lization are the two mechanisms responsible for the formation

of different mixed-layer clays.

Dioctahedral mixed-layer clays

Kaolinite-Smectite (K-S)

K-S is known from Recent soils developed on acidic to alkaline

parent rocks and from the corresponding paleosols (Hughes

etal., 1993). If present in sedimentary rocks, K-S is most often

a detrital component, which survives burial temperatures of at

least 100°C. Its further evolution has not been traced. Most

probably, the abundance of K-S is underestimated, because it

is difficult to detect and also can be misidentified by XRD as

halloysite.

K-S is typically very fine-grained, randomly interstratified,

and it always evolves from smectite (origin from kaolinite has

not been reported). The reaction has been reproduced in

laboratory and is promoted by a high supply of Al.

lllite-Smectite (I-S)

I-S is the most abundant, most ubiquitous and the most

studied mixed-layer clay. 1-S can be detected by XRD in the

<0.2 \im fraction of almost every sample of sedimentary rock.

Smectite or recycled I-S is stable in sedimentary environments

and starts to react toward more illitic composition at about

70°C.

This reaction has been originally interpreted as fixation

of potassium in smectitic (swelling) interlayers plus solid-state

transformation of layers, but currently it is explained as

dissolution of smectite layers and simultaneous nueleation of

2 nm illite particles in the swelling interlayers and subsequent

growth of these particles (see Illite Group Minerals).

Evolution of I-S is continuous, always from RO (decreasing

to ca. 45 percent smectite), through R1 (^down to 20 percent S),

to R>1, and finally to illite. Regular 1:1 interstratification (K-

rectorite) is rare, known mostly from hydrothermal environ-

ments. Chemical evolution involves enrichment of

I-S in K (and in some cases NH4) and Al, a decrease in

cation exchange capacity, and liberation of Ca, Mg, Fe, and

Si,

which contribute to quartz and carbonate cementation.

I-S crystals have a lognormal distribution of thickness with

the mean of 5-6 layers/crystal, which increases below

20 percent S.

The percent S in I-S is an indicator of diagenetic grade,

analogous to organic indicators (see Maturation, Organic), and

can be used for evaluation of maximum paleotemperatures

and their K-Ar dating (see Illite Group Minerals). Because of

its abundance and swelling layers, I-S controls mechanical,

electrical and exchange properties of most shales.

Weathering of illite or I-S is not a simple reversal of

diagenetie reaction and is not well understood. Smectite can be

produced directly by dissolution-precipitation (Sucha et al.,

2001) or by transformation via ordered illite-vermiculite and

vermiculite (Wilson and Nadeau, 1985).

Glauconite-Smectite (G-S)

^

Minerals in monomineral glauconite pellets are iron-rich

analogues of 1-S. Glauconitization (see Glaucony and

Verdine)

proceeds at the sediment/water interface, through the same

steps of random and ordered interstratifications as illitization.

Regular interstratification has not been observed. Anomalous

chemical characteristics of some samples may result from

interlayering with berthierine (iron serpentine). Data are

lacking on the evolution of G-S during burial diagenesis.

MIXED-LAYER CLAYS

449

Na-illite-smectite (rectorite)

This mineral is reported only as a regular variety, called

rectorite (allevardite in older literature), and its geological

occurrence is restricted to hydrothermal alteration zones and

low-grade metamorphic rocJcs. In both cases, it is associated

with pyrophyllite and occasionally with cookeite, which

indicates crystallization tempearatures of ca. 280°C. Some-

times,

Ca may prevail over Na, which is expressed by the

presence of margarite-like layers. Rectorite crystals are always

very thick, as is evident from their very sharp diffraction peaJcs

and electron microscope images.

Chlorite-smectite (tosudite)

This clay is known only as a regular interstratification (named

tosudite) of beidellite (Al-smectite) and di-dioctahedral chlor-

ite (donbassite), or di-trioctahedral chlorite (sudoite, Mg-rich;

or cookeite, Li-rich). Likewise, only regular interstratification

was produced in hydrothermal experiments. Tosudite is known

from hydrothermal, pneumatolytic, or low-temperature meta-

morphic alteration zones, in association with dioctahedral

chlorite, serpentine, rectorite, and pyrophyllite. This associa-

tion suggests that tosudite forms during acid hydrothermal

alteration, at temperatures well below 35O°C.

Mica (Illite)-Vermiculite (I-V)

I-V is a product of potassium removal during weathering of

micas and illite. It occurs as thick crystals, with tri-dimensional

order, frequently with almost regular interstratification. The

vermiculitic layer may evolve toward smectite, giving rectorite-

like clay (Wilson and Nadeau, 1985). Partial chloritization of

vermiculitic interlayer is, however, more common. Clays of

this type are called soil vermiculites, soil chlorites, chlorite

intergrades, or swelling chlorites (Barnhisel and Bertsch, 1989).

Formation of soil vermiculites is a massive phenomenon in

temperate climates and this material has been identified in

fresti sediments. Its further evolution during diagenesis

remains obscure.

chloritization at elevated temperatures (commonly during

burial diagenesis). The process is not fully analogous to

illitization of smectite and is not fully understood. Instead of

a continuous process, overlapping succession of three phases

is observed: C-S with <20 percent C, corrensite (regular

interstratification), and C-S > 85 percent C. Diagenetic

corrensite appears in sedimentary rocks at 60°C to 160°C. A

decrease of Si and interlayer exchangeable cations, and an

increase of tetrahedral Al accompanies chloritization.

Weathering of chlorite commonly produces corrensite as

an intermediate phase. Distinct from diagenetic corrensite,

this mineral is characterized as chlorite-vermiculite, that is,

high-charge corrensite. The final product is vermiculite (^. v.),

which may evolve latter into smectite. The process involves

loss of Fe and Mg to such extent that the end member

vermiculite is strictly dioctahedral (Proust etal., 1986).

Mica-Chlorite (M-C)

M-C is typically close to regular interlayering and the mica

component is almost exclusively biotite. All M-C minerals

occur as big crystals producing excellent quality electron

microscope images. The majority of described occurrences are

from hydrothermally altered rocks or the products of low to

medium-grade regional metamorphism of granite, gneiss,

basalt, or pelites. M-C may form both by alteration of biotite

and chlorite.

Talc-Smectite (T-S)

T-S clays are known from saline lake and hot-spring deposits,

weathered ophiolites and dolomites. They are frequently

associated with sepiolite. Full range of interstratification was

reported (Wiewiora et al., 1982), including regular aliettite.

The temperature of formation (hot springs) and solution

chemistry are probably the factors responsible for the variation

in expandability. It remains unclear whether the reaction

proceeds from smectite to talc, or vice versa, or in both

directions.

Trioctahedral mixed-layer clays

Serpentine-Chlorite (Sp-C)

Sp-C is exclusively Fe-rich clay (berthierine-chamosite). It is

known to form in Recent "verdine facies" sediments in very

shallow tropical seas (see Glaucony and Verdine), often as

sandstone grain coatings. Either both layers crystallize

simultaneously, or chloritization starts at the sea bottom.

During burial, the berthierine content decreases and disap-

pears completely at the transition zone between shales and

slates.

Sp:C ratio can be now quantified precisely by XRD

(Moore and Reynolds, 1997). Regularly interstratified Sp-C is

called dozyite. Sp-C interstratification is accompanied by

interstratification of polytypes.

Chlorite-Smectite (vermiculite) (C-S)

C-S is the second most common mixed-layer mineral in

sedimentary rocks, often occurring together with I-S, and is

characteristic of hypersaline facies, volcanoclastic rocks and

graywackes (Reynolds, 1988). Unknown from Recent

sedimentary environments, C-S is a product of smectite

MIca-Vermiculite (M-V)

M-V is a common product of K-removal during weathering of

biotite. The reaction is easily reproducible in laboratory. The

complete compositional range is known (Pozzuoli etal., 1992),

including a regular variety (hydrobiotite). Little is known

about the behavior of M-V at the subsequent stages of the

rock cycle.

Jan Srodori

Bibliography

Barnhisel, R.I., and Bertsch, P.M., 1989. Chlorites and hydroxy-

interlayered vermiculite and smectite. In Dixon, J.B., and Weed,

S.B. (eds.). Minerals in Soil Environments. Soil Science Society of

America, pp. 729-788.

Eberl, D.D., Nuesch, R., Sucha, V., and Tsipursky, S., 1998.

Measurement of fundamental particle thicknesses by X-ray

diffraction using PVP-10 intercalation. Clavs atid Clay Minerals,

46:

89-97.

Hughes, R.E, Moore, D.M., and Reynolds, R.C. Jr., 1993. The

nature, detection, occurrence, and origin of kaolinite/smectite. In

Kaolin Genesis and Utilization. The Clay Minerals Society, Special

Publication, 1, pp. 291-323.

450

MIXING MODELS

Moore, D., and Reynolds, R.C, t997. X-Ray Diffiaction and the Iden-

tification and Anaiysisof Clay Minerals. Oxford University Press.

Pozzuoli, A., Vila, E., Franco, E., Ruiz-Amil, A., and de la Calle, C,

1992.

Weathering of biotite to vermiculite in Quaternary lahars

frotn Monti Ernici, central Italy. Clay Minerals, 11: 175-184.

Proust, D., Eymery, J.P., and Beaufort, D., 1986. Supergene

vermiculitization of a magnesian chlorite: iron and magnesium

removal process. Clays and Clay Minerals, 34: 572-580.

Reynolds, R.C. Jr., 1988. Mixed layer chlorite minerals, tn

Hydrous Phyllosilicates (exelusive of

tnieas),

Mineralogical Society

of America, Reviews in Mineralogy, 19, pp. 601-629.

Srodoii, J., 1999. Nature of mixed-layer clays and mechanisms of their

formation and alteration. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary

Seienees, 27:

19-53.

Sucha, V., Srodori, J., Clauer, N., Elsass, F., Eberl, D.D., Kraus, t.,

and Madejova, J., 2001. Weathering of smectite and illite-smectite

in Central-European temperate climatic conditions. Clay Minerals,

36:

403-419.

Wiewiora, A., Dubiriska, E., and twasiriska, I., 1982. Mixed-layering

in Ni-containing talc-like minerals from Szklary, Lower Silesia,

Poland. In Proeeedings of tlie International Clay Conference, ttaly:

Bologna-Pavia, pp. 111-125.

Wilson, M.J., and Nadeau, P.H., 1985. Interstratified clay minerals

and weathering processes. In Drever, J.I. (ed.). The Chemistry of

Weathering, D. Reidel, pp. 97-118.

Cross-references

Bentonites and Tonsteins

Berthierine

Chlorite in Sediments

Clay Mineralogy

Diagenesis

Glaucony and Verdine

Illite Group Clay Minerals

Kaolin Group Minerals

Mudrocks

Smectite Group

Vermiculite

Weathering, Soils, and Paleosols

principle of mass/chemical species conservation, and their

mathematical forms depend on the particular assumptions

made about the nature of the mixing. For example, mixing due

to the random movement of small infauna, the feeding of

head-down (conveyor belt) species, the infilling of vacated

burrows, and the resuspension of sediment by clams or waves

all generate different types of sediment motions and, in

principle, these differences are ret!ected in different mathema-

tical forms for the appropriate mixing model (Boudreau,

1997).

However, in practice, workers in this field tend to use a

simple array of models, that is, well-mixed models, diffusive

models, and nonlocal models. In addition, these models can be

distinguished further on the basis of the nature of the inputs

they require and outputs they produce. Thus, models can be

either of forward type, where the user inputs all parameter

values and expects a prediction of the distribution of a

sediment component with space and/or time, or they can be of

backward type, where parameters or the input history are

calculated from the observed depth profile of a sediment

property.

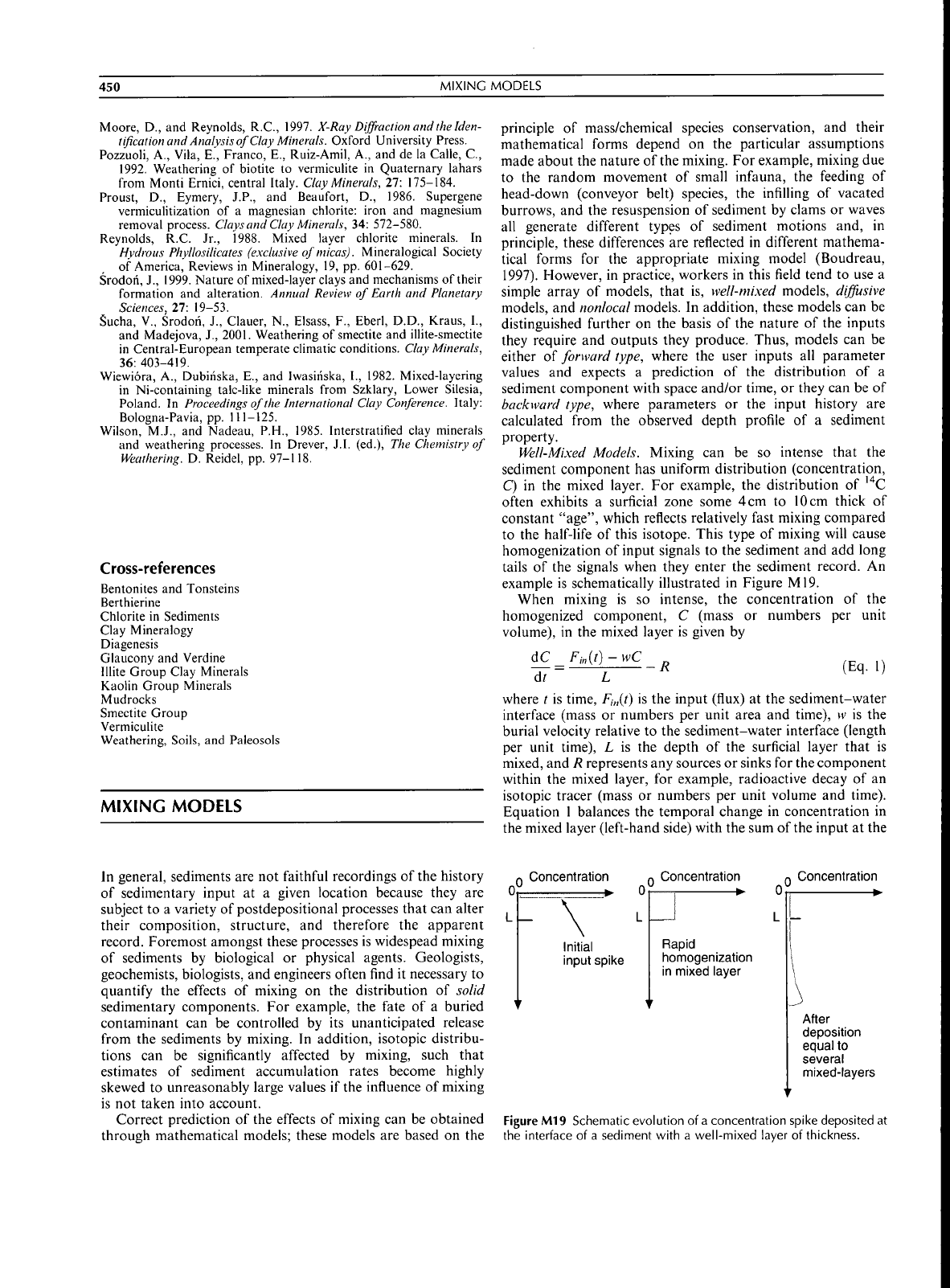

Well-Mixed Models. Mixing can be so intense that the

sediment component has uniform distribution (concentration,

C) in the mixed tayer. For example, the distribution of '^C

often exhibits a surficial zone some 4 cm to

10

cm thick of

constant "age", which retlects relatively fast mixing compared

to the half-life of this isotope. This type of mixing will cause

homogenization of input signals to the sediment and add long

tails of the signals when they enter the sediment record. An

example is schematically illustrated in Figure M19.

When mixing is so intense, the concentration of the

homogenized component, C (mass or numbers per unit

volume), in the mixed layer is given by

dC

dt

•-R

(Eq. 1)

MIXING MODELS

where t is time, Fjjf) is the input (flux) at the sediment-water

interface (mass or numbers per unit area and time), w is the

burial velocity relative to the sediment-water interface (length

per unit time), L is the depth of the surticial layer that is

mixed, and R represents any sources or sinks for the component

within the mixed layer, for example, radioactive decay of an

isotopic tracer (mass or numbers per unit volume and time).

Equation 1 balances the temporal change in concentration in

the mixed layer (left-hand side) with the sum of the input at the

In general, sediments are not faithful recordings of the history

of sedimentary input at a given location because they are

subject to a variety of postdepositional processes that can alter

their eomposition, structure, and therefore the apparent

record. Foremost amongst these processes is widespead mixing

of sediments by biological or physical agents. Geologists,

geochemists, biologists, and engineers often find it necessary to

quantify the effects of mixing on the distribution of solid

sedimentary components. For example, the fate of a buried

contaminant can be controlled by its unanticipated release

from the sediments by mixing. In addition, isotopic distribu-

tions can be significantly affected by mixing, such that

estimates of sediment accumulation rates become highly

skewed to unreasonably large values if the intluence of mixing

is not taken into account.

Correct prediction of the effects of mixing can be obtained

through mathematical models; these models are based on the

Concentration

Concentration Concentration

Initial

input spike

Rapid

homogenization

in mixed layer

After

deposition

equal to

several

mixed-layers

Figure M19 Schematic evolution ofa concentration spike deposited at

the interface of a sediment with a well-mixed layer of thickness.

MUDKtK.KS

451

itiferface. the output (bitrial) at the base of the mixed layer,

and the net ptoduction (consumption) by sources and sinks on

the right-hand side.

Diffusion Modets. Mixing is often not strong enough to

homogenize the active layer, and in this case the concentration

of the sediment component will also be a function of space, as

well as time. The most popular model in this case likens the

effects of mixing to those of diffusion (see ChemicalDiffiision).

whereby mixing imparts small random motions to the

sediment particles. The mathematical form of this model is.

at constant porosity,

(Eq. 2)

where. ,v is depth in the sediment. Ds is the tnixini! coeftieient.

analogous to the molecular/ionic diffusion coefficient (length

squared per unit titne), and the other terms are as in equatioti

(1).

Here the temporal change at a given depth (left) is the

result ofa balance (right) between the effects of mixing, burial

and reaction.

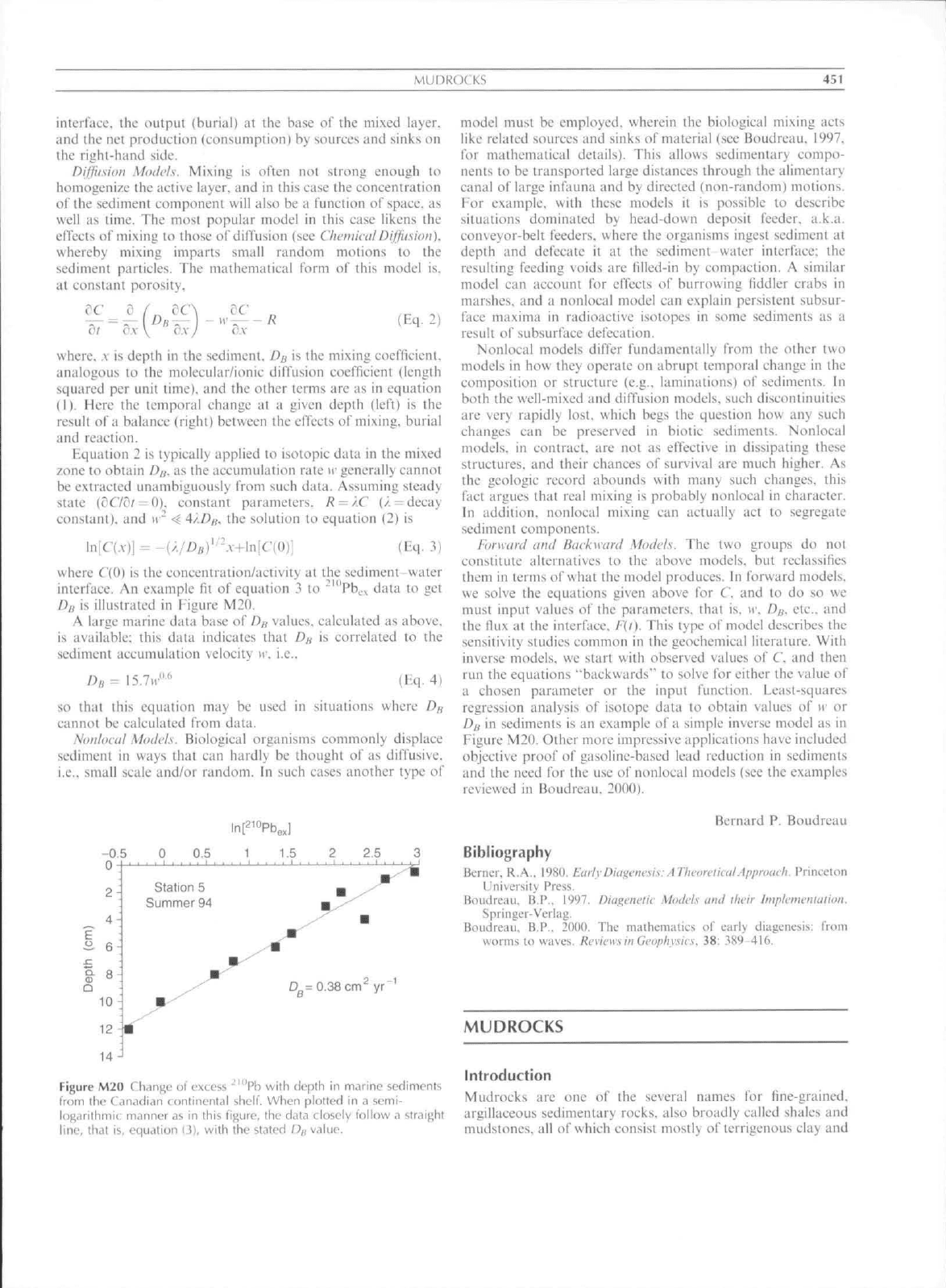

Fquation 2 is typically applied to isotopic data in the tnixed

zone to obtain Du. as the accumulation rate ir generally cannot

be extracted unatnbiguously from such data. AssutnJng steady

state {cCldt = 0). constant paratneters. R-/.C (A = decay

constant), and ir" <| 4/.Ds. the solution to equation (2) is

ln\C(.x)] = -(

fEq. 3)

where C\0) is the concentration/aetivity at the sediment-water

interface. An example fit of equation ? to ^'"Pb^.^ data to get

D/i

is iilustntted in Figure M20.

A large marine data base of Dg values, calculated as above,

is available; this data indicates that Df) is correlated to the

sediment accumulation velocity w. i.e..

= l.S.7ir

(Eq. 4)

so that ihis eqttation may be used in situations where D/j

cannot be calculated from data.

Nonlocal Models. Biological organisms commonly displace

sediment in ways that can hardly be thought of as diffusive,

i.e.. stnall scale and/or random. In such cases another type of

Figure M20 Chtinge oi excess ''"'Pb with depth in marine seditnents

from tlu' C\in.idi.in continenlai shelf. When plotted in a semi-

logarithmit manner js in ihis figure, the data closely follow a str<5ight

line,

that is, equation

L3).

with the stated D,, value.

model must be employed, wherein the biological mixing acts

like related sources and sinks of material (see Boudreau. 1997.

for mathematical details). This allows sedimentary compo-

nents to be transported large distances through the alimentary

canal of large infauna and by directed (non-random) motions.

For example, with these models it is possible to describe

situations dominated by head-down deposit feeder, a.k.a.

conveyor-belt feeders, where the organisms ingest sediment at

depth and defecate it at the sediment water interface: the

resulting feeding voids are ftlled-in by eotnpaction. A sitnilar

model can account for effects of burrowing fiddler crabs in

marshes, and a nonlocal model can explain persistent subsur-

face maxitna in radioactive isotopes in some seditnents as a

result of subsurface defecation.

Nonlocal tnodels differ fundamentally from the other two

models in how they operate on abrupt tetnporal change in the

cotnposition or structure (e.g.. latninations) of seditnents. In

both the well-tnixed and diffusion models, such discontinuities

are very rapidly lost, which begs the question how any such

changes can be preserved in biotic sedimenls. Nonlocal

models, in contract, are not as effective in dissipating these

structures, and their chances of survival are much higher. As

the geologic record abounds with many such changes, this

faet argues that real mixing is probably nonlocal in character.

In addition, nonlocal tnixing can actually act to .segregate

sediment components.

Forward and Backward Models. The two groups do not

constitute alternatives to the above models, but reclassifies

them in terms of what the model produces. In forward models,

we solve the equations given above for C. and to do so we

must input values of the parameters, that is. w. Dg. etc.. and

the tlux at the interface, F{t), This type of model describes the

sensitivity studies cotnmon in the geochetnical literature. With

inverse models, we start with observed values of C. and then

run the equations "backwards" to solve for either the value of

a chosen parameter or the input function. Least-squares

regression analysis of isotope data to obtain values of

H'

or

Du in seditnents is an example of a simple inverse model as in

Figure M20. Other more impressive applications have ineluded

objective proof of gasoline-bttsed lead reduction in sediments

and the need for the use of nonlocal models (see the examples

reviewed in Boudreau. 2000).

Bernard P. Boudreau

Bibliography

BerntT, R.A . 1980. Early

Diagenesis:

ATheoretieat Approach, Princeton

University Press.

Boudreau. B.P.. 1997. Diagenetic Models und their Implementation,

Springer-Verlag.

Boudreau. B.P.. 2()()(). The mathematics of early diagenesis: Irotn

worms to waves. Reviews in

Geophysics,

38: 389 416.

MUDROCKS

Introduction

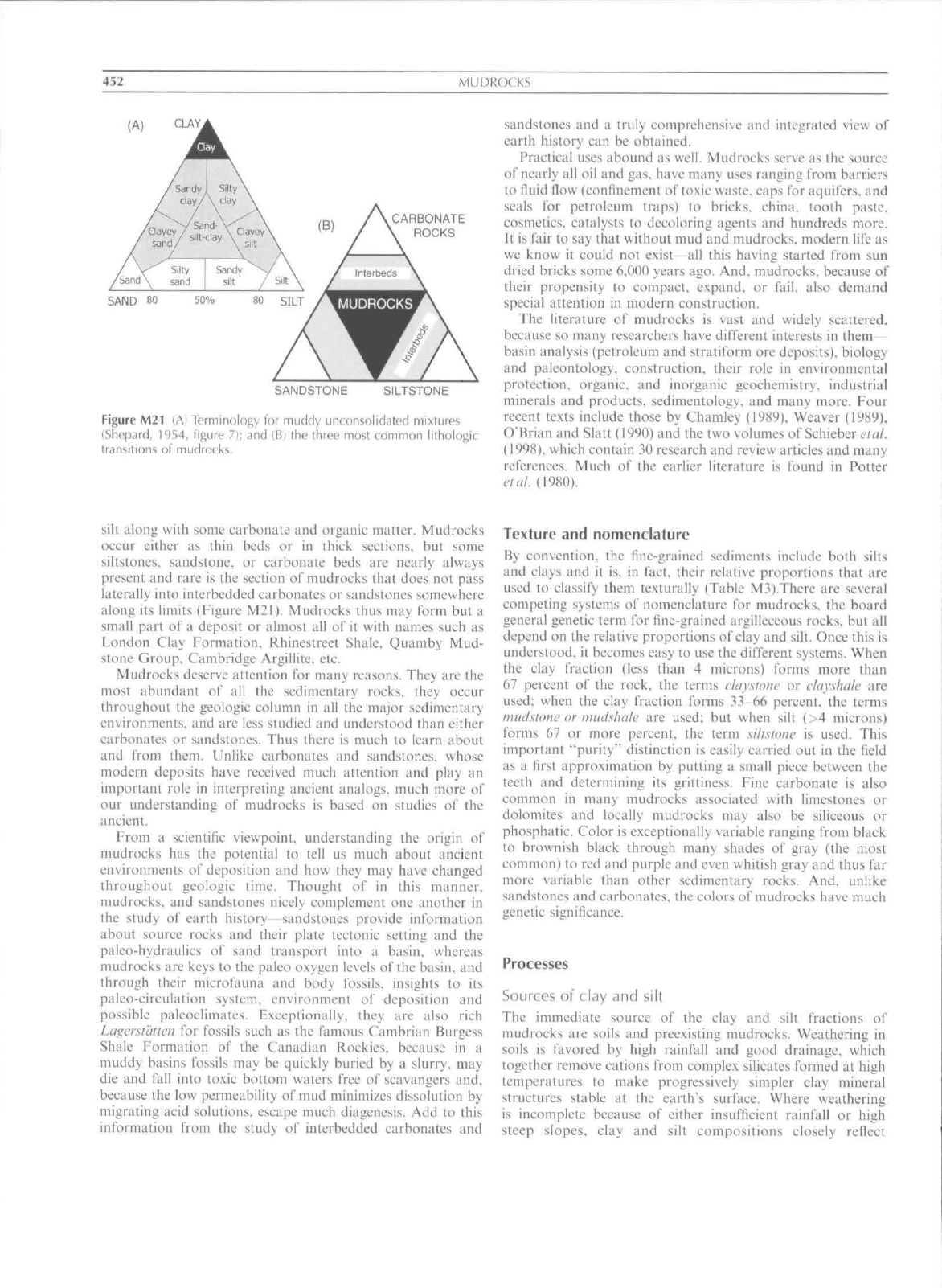

Mudrocks are one of the several names for fine-grained,

argillaceous sedimentary roeks. also broadly called shales and

mudstones, all of which consist mostly of terrigenous clay and

452

MUDROCKS

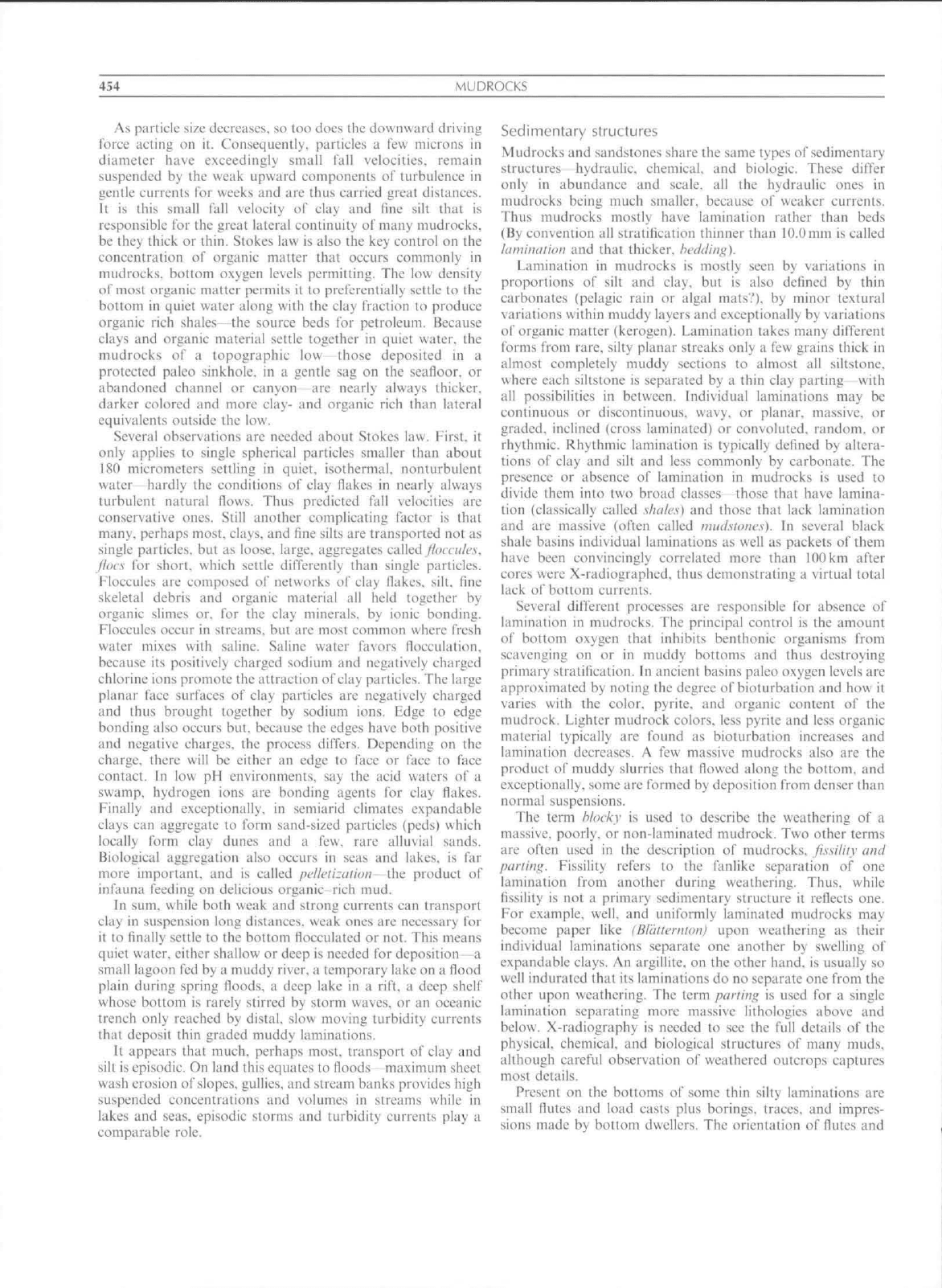

(A)

CLAY

CARBONATE

ROCKS

SANDSTONE

SILT3T0NE

Figure M21 (A) Terminology for muddy unconsolidated mixtures

{Shepartl,

1954, figure 71; and (B) Ihp three most common lithologic

transitions of mudrocks.

sandstones and it truly cotnprehensive and integrated view of

earth history can be obtained.

Practical uses abound as well. Mudrocks serve as the source

of nearly all oil and gas, have many uses ranging from barriers

to lluid flow (eonfinement of loxic waste, caps for aquifers, and

seals for petroleum Iraps) to bricks, china, tooth paste,

cosmetics, catalysts to decoloring agents and hundreds more.

It is fair to say that without tnud and mudrocks, modern life as

we know it could not exist all this having started from sun

dried bricks some 6.000 years ago. And. mudroeks, because of

their propensity to compact, expand, or fail, also detnand

special attention in modern construction.

The literature of mudroeks is vast and widely scattered,

because so many researchers have difTerenl interests in them -

basin analysis (petroleum and stratiform ore deposits), biology

and paleontology, construction, their role in environmental

protection, organie, and inorganic geochetnistry, industrial

minerals and products, sedimentology, and many more. Four

recent texts include those by Chamley (1989). Weaver (1989).

O"Brian and Slatt (1990) and the two volumes of Schieber ctai.

(1998).

which contain 30 research and review articles and many

references. Much of the earlier literature is foutid in Potter

ctai. (1980).

silt along with sotne carbonate and organic matter. Mudrocks

occur either as thin beds or in thick sections, but some

siltstones. sandstone, or carbonate beds are nearly always

present and rare is the section of mudroeks that does not pass

laterally into interbedded carbonates or sandstones somevv-here

along its limits (Figure M21). Mudrocks thus may form but a

stnall part of a deposit or almost all of it with names sueh as

London Clay Formation, Rhinestreet Shale. Quamby Mud-

stone Group. Cambridge Argillite. ete.

Mudrocks deserve attention for many reasons. They are the

most abundant of all the sedimentary rocks, they occur

throughout the geologic colutnn in all the major sedimentary

environtnents. and are less studied and understood than either

carbonates or sandstones. Thus there is much to learn about

and from them. Unlike carbonates and sandstones, whose

modern deposits have recei\ed much attention and play

AW

itnportant role in interpreting ancient analogs, much more of

our understanding of mudrocks is based on studies of the

ancient.

From a scientific viewpoint, understanding the origin of

mudrocks has the potential to tell us much about ancient

environments of deposition and how they may have changed

throughout geologic time. Thought of in this manner,

mudrocks. and satidstones nicely cotnpletnetit one another in

the study of earth history—sandstones provide information

about source rocks atid their plate tectonic setting and the

paleo-hydraulics of sand transport into a basin, whereas

mudrocks are keys to the paleo oxygen levels of the basin, and

through their tnicrofauna and body fossils, insights to its

paleo-circulation system, environment of deposition and

possible paleoclimates. Exeeptionally. they are also rich

La^cr.stdttcit for fossils such as the famous Cambrian Burgess

Shale Formation of the Canadian Rockies, because in a

muddy basins fossils may be quiekly buried by a slurry, may

die and fall into loxic bottotn waters free of scavangers and.

because the low pcrtneability of tnud tninimi/es dissolution by

migrating aeid solutions, escape much diagenesis. Add to this

information frotn the study of interbedded carbonates and

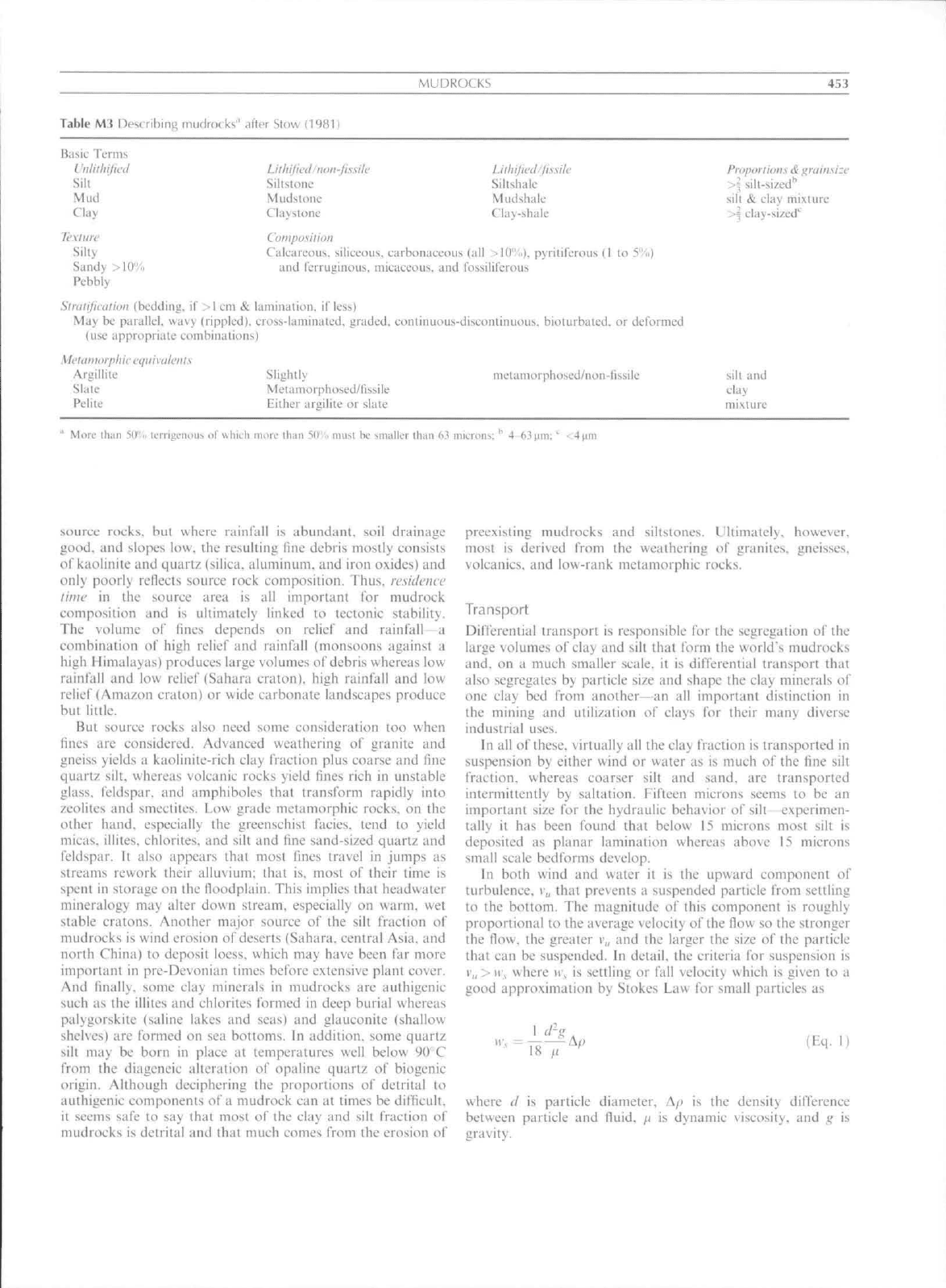

Texture and nomenclature

By convention, the ftne-grained sediments inelude both silts

and clays and it is. in fact, their relative proportions that are

used to classify them texturally (Table M3).There are several

competing systems of nomenclature for mudrocks. the board

general genetic term for fine-grained argilleceous rocks, but all

depend on the relative proportions of clay and silt. Once this is

understood, it becomes easy to use the different systetns. When

the clay fraction (less than 4 microns) forms more than

67 percent of the rock, the terms claystone or ctayshale are

used: when the clay fraction tbrms .'^.3 66 pereent. the tertns

miulstone or ntudshalc are used; but when silt (>4 mierons)

forms 67 or tnore percent, the term sittstoiw is used. This

important "purity" distinction is easily carried out in the field

as a first approximation by putting a small pieee between the

teeth and determining its grittiness. Fine carbonate is also

comtnon in tnany mudrocks associated with limestones or

dolomites and locally mudrocks tnay also be silieeous or

phosphatic. Color is exceptionally variable ranging from black

to brownish black through many shades of gray (the tnost

comtnon) to red and purple and even whitish gray and thus far

more variable than other seditnentary rocks. And, unlike

sandstones and earbonates, the colors of mudrocks have tnuch

genetic significance.

Processes

Sources of clay and silt

The immediate source of the clay and silt fractions of

mudrocks are soils and preexisting tnudrocks. Weathering in

soils is favored by high rainfall and good drainage, which

together remove cations frotn complex silicates formed at high

tetnperatures to tnake progressively sitnpler clay mineral

structures stable at the earth's surfaee. Where weathering

is incomplete because of either insufficient rainfall or high

steep slopes, elay and silt compositions closely reflect

MUDROCKS

Table

M:1

Dest rihins; mtiflriK ks' after Stow

(1981:

Biisic Terms

Unlit hij ted

Silt

Mud

Clay

Texture

Silly

Sandy >10"/.

Pebbly

Lithified'lion -ji.'isite

Siiistonc

Miidstotie

Claystone

Lithified/fissile

Sillshalc

Mudshiile

Clav-sliale

Composition

Calcareous, siliceous, carbonaceous (all •>!()"'..), pyritiferous (I to 57")

atid lerritiiitiotis. niicaccoiis. and fossilifcroiis

Stratijieation (bedding, if >

1

cm & iamination. if less}

May be parallel, wavy (rippled), ctoss-laininated. graded, continiious-disconiiiuiou.s. bioturbated. or defortned

(iisi;

appropriate cotiibinatioti.s)

Metamorphie

eijuiv(denis

Argillite

Slale

Peltte

Sliglitly

Mciamorpfiosed/fissite

liither ;iri;ilite or slale

Proptirtions &

grainsize

>\ silt-sized''

silt & clay mixture

>^ clay-sized''

silt and

c-lay

mixture

'' More ttian

511"

<i

ti;rn>iL'iiou> ul

i^liiLh

mint' \\r.m >H'.. must be smaller than (i.' micron^: '' 4 63fm!. ' - 4nni

source rocks, but where rainfall is abundant, soil drainage

good, and slopes low. the resulting fine debris mostly eonsists

of kaolinite and quartz (silica, iiluminuni, and iron oxides) and

only poorly reflects source rock composition. Thus, rcmlenci'

titne in the source area is all important for mudrock

composition and is ultimately linked to tectonic stability.

The volume of fines depends on relief and rainfall u

eotnbination of high relief and rainfall (monsoons against a

high Htmalayas) produces large volutnes of debris whereas low

rainfall and low relief (Sahara craton). high rainfall and low

relief (Aniai^on craton) or wide carbonate landscapes produce

but little.

But source rocks also need sotne consideration too when

fines are considered. Advanced weathering of granite and

gneiss yields a kaolinitc-ricli clay fraction plus coarse and fine

quartz silt, whereas volcanic rocks yield lines rich in unstable

glass,

tl'ldspar. and amphiboles that transform rapidly into

/eolttes and stnectites. Low grade tnetamorphic rocks, on the

other hand, especially the greenschist facies, tend to yield

micas,

illites, chlorites. and silt and fine sand-sized quartz and

feldspar. It also appears that most fines travel in jumps as

streams rework their alluvium; that is. most of their time is

spent in storage on the lloodpKiin. This implies that headwater

mineralogy may alter down stream, especially on wartn. wet

stable cratons. Another major source of the silt fraction of

mudrocks is wind erosion of deserts (Sahara, central Asia, and

north China) to deposit loess, whtch tnay have been far tnore

important in pre-Devonian times before extensive plant cover.

And finally, some clay minerals in mudrocks are authigenic

such as the illiles and chlorites formed in deep burial whereas

palygorskite (saline lakes and seits) and glauconite (shallow

shcKes) itre fortned on sea bottoms. In addition, some quartz

silt may be born in place at tempertitures well below 90 C

trom the diageneic alteration of opaline quart/ of biogenic

origin. Although deciphering the proportions of detrital to

authigenic components ofa tnudrock can at times be difficult.

it seems safe to say that most of the clay and silt fraetion of

mudrocks is detrital and that mitch cotnes frotn the erosion of

preexisting tnudrocks and siltstones. Ultitnately, however,

most is derived IVom the weathering of granites, gneisses,

volcanics. and low-rank metamorphic rocks.

Tratisport

Differential transport is responsible for the segregation of the

large volumes of clay and silt that form the world's mudrticks

and, on a tnuch stnaller scale, it is differential transport that

also segregates by particle size and shape the clay minerals of

one clay bed from another—an all important distinction in

the tnining and utilization of clays for their many diverse

industt"iul uses.

In ail of these, virtually all the clay fraction is transported in

suspension by either wind or water as is tnuch of the line silt

fraction, whereas coarser silt and sand, are transported

intertnittently by saltation. Fifieen microns seems to be an

important size for the hydraulie behavior of silt experimen-

tally it has been found that below 15 microns most silt is

deposited as planar lamination whereas above 15 mierons

small scale bedforms develop.

In both wind and water it is the upward cotnponent of

turbulence, r,, that prevents a suspended particle tVotn settling

to the bottom. The tnagnitude of this component is roughly

proportional to the average veloeity of the flow so the stronger

the flow, the greater i,, and the larger the size of the particle

that can be suspended. In detail, the criteria for suspension is

V,,

> vt', where n', is settling or fall velocity which is given to a

good approximation by Stokes Law for stnall particles as

(Eq. I)

where d is particle diatneter. A/J is the density difference

between particle and fluid, fi is dynamic viscosity, and t,' is

gravity.

454 MUDROCKS

As particle size decreases, so too does the downward driving

force acting on it. Consequently, particles a few microns in

diameter have exceedingly small fall velocities, remain

suspended by the weak upward components of turbulence in

gentle currents for weeks and are thus carried great distances.

It is this small fall velocity of elay and tine silt that is

responsible for the great lateral continuity of many mudroeks,

be they thick or thin. Stokes law is also the key control on the

concentration of organic matter that occurs commonly in

mudrocks. bottom oxygen levels permitting. The low density

of most organic matter permits it to preferentially settle to the

bottom in quiet water along with the clay fraction to produce

organic rich shales—the source beds for petroleum. Becatise

clays and organic material settle together in quiet water, the

mudrocks of a topographic low those deposited in a

protected paleo sinkhole, in a gentle sag on the seafloor. or

abandoned channel or eanyon are nearly always thieker,

darker colored and more clay- and organic rich ihan lateral

equivalents outside the low.

Several observations are needed about Stokes law. First, it

only applies to single spherieal partieles smaller than about

180 micrometers settling in quiet, isothermal, nonturbulent

water hardly the conditions of clay flakes in nearly always

turbulent natural flows. Thus predicted fall velocities are

conservative ones. Still another complicating factor is that

many, perhaps most, clays, and fine silts are transported not as

single particles, but as loose, large, aggregates called floccules,

Jiocs for short, which settle differently than single partieles.

Floccules are composed of networks of clay flakes, silt, fine

skeletal debris and organic material all held together by

organic slimes or. for the clay minerals, by ionic bonding.

Floccules occur in streams, but are most eommon where (resh

water mixes with saline. Saline water favors (locculation,

because its positively charged sodium and negatively charged

chlorine ions promote the attraction of elay partieles. The large

planar face surfaces of clay particles are negatively eharged

and thus brought together by sodium ions. Edge to edge

bonding also occurs but. because the edges have both positive

and negative charges, the process differs. Depending on the

charge, there will be either an edge to face or face to face

contact. In low pH environments, say the acid waters of a

swamp, hydrogen ions are bonding agents for clay flakes.

Finally and exceptionally, in .semiarid climates expandable

clays can aggregate to form sand-sized partieles (peds) whieh

locally form clay dunes and a few, rare alluvial sands.

Biological aggregation also oecurs in seas and lakes, is far

more important, and is called peUelizalion the product of

infauna feeding on delicious organic rich mud.

In sum. while both weak and strong currents can transport

clay in suspension long distances, weak ones are necessary for

it to Iinally settle to the bottom flocculated or not. This means

quiet water, either shallow or deep is needed for deposition—a

small lagoon fed by a muddy river, a temporary lake on a flood

plain during spring Hoods, a deep lake in a rift, a deep shelf

whose bottom is rarely stirred by storm waves, or an oceanic

trench only reached by distal, slow moving turbidity eurrents

that deposit thin graded muddy laminations.

It appears that much, perhaps most, transport of clay and

silt is episodic. On land this equates to floods- maximum sheet

wash erosion of

slopes,

gullies, and stream banks provides high

suspended eoneentrations and volumes in streams while in

lakes and seas, episodic storms and turbidity currents play a

comparable role.

Sedimentary structures

Mudrocks and sandstones share the same types of sedimentary

structures—hydraulic, chemical, and biologic. These differ

only in abundanee and scale, all the hydraulic ones in

mudrocks being much smaller, because of weaker currents.

Thus mudrocks mostly have lamination rather than beds

{By convention all stratiflcation thinner than lO.Omm is called

laminalion and that thieker, heddjiig).

Lamination in mudrocks is mostly seen by variations in

proportions of silt and clay, bul is also deiined by thin

carbonates (pelagic rain or algal mats'), b> minor textural

variations within muddy layers and exceptionally by variations

of organic matter (kerogcn). Lamination takes many different

forms from rare, silty planar streaks only a few grains thick in

almost completely muddy sections to almost all siltstone,

where each siltstone is .separated by a thin elay parting with

all possibilities in between. Individual laminations may be

continuous or discontinuous, wavy, or planar, massive, or

graded, inclined (cross laminated) or convoluted, random, or

rhythmic. Rhythmic lamination is typically defined by altera-

tions of clay and silt and less commonly by carbonate. The

presence or absenee of lamination in mudrocks is used to

divide them into two broad classes—those that have lamina-

tion (classically called shale.s) and those that lack lamination

and are massive (often called mutlstoncs). In several black

shale basins individual laminations as well as packets of them

have been convincingly correlated more than 100 km after

cores were X-radiographed, thus demonstrating a virtual total

laek of bottom currents.

Several dilTerent processes are responsible for absence of

lamination in mudrocks. The principal control is the amount

ol"

bottom oxygen that inhibits benthonic organisms from

scavenging on or in muddy bottoms and thus destroying

primary stratification. In ancient basins paleo oxygen levels arc

approximated by noting the degree of bioturbation and how it

varies with the color, pyrite, and organic content of the

mudroek. Lighter mudrock colors, less pyrite and less organic

material typically are found as bioturbation increases and

lamination decreases. A few massive mudrocks also are the

product of muddy slurries that flowed along the bottom, and

exeeptionally, some are formed by deposition from denser than

normal suspensions.

The term hlocky is used to describe the weathering of a

massive, poorly, or non-laminated mudrock. Two other terms

are often used in the description of mudrocks. fissility and

purling. Fissility refers to the fanlike separation of one

lamination from another during weathering. Thus, while

fissility is not a primary sedimentary strueture it reflects one.

For example, well, and uniformly laminated mudroeks may

become paper like (Blaitcrnion) upon weathering as their

individual laminations separate one another by swelling oi

expandable clays. An argillitc. on the other hand, is usually so

well indurated that its laminations do no separate one from the

other upon weathering. The term parting is used for a single

lamination separating more massive lithologies above and

below. X-radiography is needed to see the full details of the

physical, chemical, and biological structures of many muds,

although careful observation of weathered outcrops captures

most details.

Present on the bottoms of some thin silty laminations are

small flutes and load casts plus borings, traces, and impres-

sions made by botlom dwellers. The orientation of flutes and