Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

LUNAR SEDIMENTS

415

LUNAR SEDIMENTS

Introduction

The surface and surficial deposits on the Moon are radically

different from Earth's, The Moon is completely dry and does

not have an atmosphere; it is devoid of an internally driven

magnetic field and plate tectonics is absent; large and small

impacts through time have produced a thick regolith, and

sediments so produced are transported ballistically, Regolith

may be shock-indurated by fresh impacts, or may be buried

under fresh ejecta that may be hot and may sinter unconso-

lidated grains together, to produce regolith breccias. All lunar

samples are from the regolith; and, all remote sensing signals

(albedo, UV-Vis-IR reflectance [of sunlight], natural

y-ray,

and

X-ray

fluorescence [by solar X-rays] spectra) of the Moon are

from its regolith. Most of the signals come from the uppermost

0,5 |im layer, that is, almost entirely from the dusty veneer of

the Moon, Because the composition of the finest fractions of

lunar soils is different from the bulk composition of any lunar

soil, it is essential that all calibration be corrected back to the

compositions of bulk soils. The remote sensing techniques and

their lunar calibrations are used to explore all atmosphere-free

rocky bodies in the solar system; hence the extreme importance

of precise and accurate characterization of lunar soils in

planetary exploration.

In the initial days of lunar sample return by Apollo

missions, the sub-centimeter fraction of the samples was

informally termed "fines" and then "lunar soil" came in

vogue. In lunar science literature and in the community, "soil"

is now entrenched with an informal size connotation; the word

has no significance vis a vis its use for Earth materials in

agricultural, engineering, geological, and hydrological

sciences. In general, lunar soils are gray in color and consist

of angular and irregularly shaped grains with a mean size of

about 60|im, Grains cemented with fresh glass produced by

micrometeorite impacts on lunar soils produce a type of

constructional particle called agglutinate (a term adapted

from terrestrial pyroclastic vocabulary). Except for a minor

(<2 percent) meteoritic component, lunar soil composition

varies between anorthositic and basaltic, McKay etal. (1991)

summarize lunar soil data gathered up to about 1990,

Petrographic composition

Two principal terrains configure the lunar surface. One is a

high mountainous terrain (highlands) consisting of light

colored anorthositic rocks that are 4,4 billion years or older

in age. Flat lowlands, essentially impact basins (mare) filled

with dark Fe-rich basalt flows ranging in age from about 3

billion years to 4 billion years in age, comprise the other.

Impacts have mechanically disintegrated these rocks and have

also indurated some of the clasts together. The regolith on the

surfaces of these units generally reflects the composition and

the color of the rock units below although there has been some

mixing of distant impact ejecta in all local soils. The majority of

lunar soils consist of five major grain types: mineral fragments

(10-40 percent), igneous and metamorphic rock fragments

(5-20 percent), breccias with various degrees of coherence

(10-40 percent), and agglutinates (20-50 percent). Glass

spherules of either impact or volcanic fire fountain origin

make up a minor component (usually <5 percent) except in a

few unusual soils and in some restricted size ranges. Genetic-

ally, lunar soil components may also be classified into two

groups: bedrock derived and regolith derived. Agglutinates,

regolith breccias, and glass spherules are regolith-derived

components.

Orange soil

An orange layer in the regolith near the Shorty Crater in Mare

Tranqullitatis consists of more than 90 percent high-titanium

(up to 16 percent TiO2) glass beads ranging in color from

orange and red to black in hand specimen. At the bottom of a

nearby drill core the soils consist of nearly 100 percent black

beads in which skeletal crystals of olivine and ilmenite abound.

These beads are products of volcanic fire fountaining with

remnants of condensed volcanic gases on their surface. Beads

of high magnesium iron-poor green volcanic glass are also

found in significant amounts a few soils from the Apennine

Mountains but not in layers.

Chemical composition

Chemical compositions of lunar soils also range from basaltic

to anorthositic. Mixing of mare and highland components in

different proportions give rise to diverse soil compositions.

Differential comminution and differential agglutination of

lunar soils have rendered different size fractions to be

compositionally different from each other. The extent of mare

ejecta mixing with highland soils and vice versa can be

estimated better from the chemical compositions of soils than

from modal compositions, partly because a few minor and

trace element concentrations are characteristic of certain

pristine igneous rocks. Average compositions (wt percent) of

a few typical mare and highland soils are given below.

SiO2

TiO2

AI2O3

Cr2O3

FeO

MnO

MgO

CaO

Na20

K,0

Mare

40,6

8,4

12,0

0,45

16,7

0,23

9,9

10,9

0,16

0,14

Highland

45,0

0,54

27,3

0,33

5,1

0,30

5,7

15,7

0,46

0,17

Crustal composition of the moon

With no bedrock sampled so far, direct evidence of rock types

in the crust of the Moon comes from regolith samples. Rock

fragments from boulder sizes to sand sizes have been analyzed

for chemical and mineralogic compositions, crystal chemistry,

isotopic systematics, radiometric age dating, experimental

petrology, and nuclear and ferromagnetic resonance measure-

ments, to name a few. It is a tale of incredible provenance

sleuthing. The crust of the Moon is inferred to be made mostly

of ferroan and gabbroic anorthosites, norites enriched in K,

REE, P, U, and Th, various kinds of Fe-rich (~20 percent

FeO) basalts that have large ranges of K2O (0,06-0,36 percent)

and TiO2 (0,4-13,0 percent), and a low-Fe basalt (~10 percent

416 LUNAR SEDIMENTS

FeO) with higher concentrations of K2O (~0,5 percent or

more),

P (~2500ng/g), and REE,

Grain size

Lunar regolith samples are not plentiful, NASA allocated

approximately 0,5 g or 0,25 g of the submillimeter fraction of

lunar soils for determining their grain size distribution. Sieving

with minimal loss required more than 20 hours spanned in

about 4 to 5 workdays per sample. The results were then

combined with those of the subcentimeter fraction of the

rather hastily sieved lunar regolith at NASA's curatorial

facilities

(Graf,

1993), The mean grain size (Mz) of lunar soils

range between

34>

and 4(^ (125-62,5 fim) and their inclusive

graphic sorting

((TIG)

generally vary between

2(j>

and

3.0(j>,

that

is,

they are poorly sorted by terrestrial standards. Many soils

are coarsely skewed; much of the fine dust is locked up in

agglutinates.

Vertical profile

Several trenches, drive tubes, and drill cores have penetrated

and sampled the lunar regolith up to a depth of about

3

m.

Understandably none has reached bedrock. Each section of the

regolith shows evidence of layering, by way of color (shades of

gray),

grain size, chemical and mineralogical composition, and

maturity. However, layers in closely spaced drill cores and in

adjacent trenches (within a few meters) do not correlate

indicating that impacts have moved the regolith considerably.

Nearly all vertical profiles of soils show that the topmost layer

is more mature (see below for the concept) than those below.

equal. In this steady state, continued exposure of lunar soils at

the surface increases the abundance of agglutinates but does

not reduce the mean grain size any more. However, slightly

larger impacts excavate material from below, which may not

be as mature, and mix the two together. Such events disturb

the steady state. Most lunar soils presumably are not in a

steady state but may be close to one.

Because the Moon does not have any magnetosphere or

any atmosphere, energetic particles of the solar wind freely

bombard the lunar surface and implant solar wind elements

(SWE), especially hydrogen ions, in the outer rinds (~150nm)

of exposed soil grains. Abundance of SWE in lunar soils

increases with maturity. Apart from melting a small fraction of

lunar soil grains, micrometeoritic impacts also vaporize a part

of the target and much of

itself.

Elemental dissociation takes

place in the high temperature vapor from which nanophase

Fe° metal condenses and is deposited on surfaces of soil grains.

Additionally, the melt itself may undergo reduction reactions

with implanted hydrogen and produce nanophase Fe" globules

that are strewn in agglutinitic glass. The two processes not

only darken lunar soils but also increase the abundance of

nanophase Fe" with increasing maturity (Hapke, 2001; McKay

etal., 1991),

A robust correlation between the abundance of agglutinates,

SWE, nanophase Fe" (measured by ferromagnetic resonance),

inverse grain size, and to some extent with soil color strongly

supports the inferred processes of lunar soil evolution,

Abhijit Basu

Origin and evolution

Large meteorite impacts up to about 1 b,y, ago have produced

most of the regolith of the Moon, Impacts by micrometeorites

(<1 mm) have continuously comminuted the regolith and are

largely responsible for the production of lunar soils, Micro-

meteoritic impacts on lunar soils melt a miniscule amount,

mostly the finest dust, at the point of impact. The melt

incorporates soil grains as clasts and quenches quickly to

produce agglutinates, that is, glass bonded aggregates, Micro-

meteoritic impacts affect only the topmost millimeters of the

lunar regolith. With continued exposure, that is, increasing

maturity, the soil in this layer becomes finer and finer

simultaneously producing agglutinates that are larger. Over

time the rate of comminution and agglutination becomes

Bibliography

Graf,

J,C,, 1993,

Lunar

soils

grain

size

catalog,

NASA Reference

Pub-

lication

1265.

Houston:

NASA,

406pp,

Hapke,

B,, 2001,

Space

weathering

from

Mercury

to the

asteroid

belt.

Journal

of

Geophysieal

Research-Planets,

106: 10039-10073,

McKay,

D,S,,

Heiken,

G,H,,

Basu,

A,,

Blanford,

G,,

Simon,

S,,

Reedy,

R,,

French,

B,M,, and

Papike,

J,J,, 1991, The

lunar

regolith.

In

Heiken,

G,H,,

Vaniman,

D,, and

French,

B,M, (eds,).

Lunar

Soureebook.

Cambridge

University

Press, pp,

285-356,

Cross-reference

Sediments

Produced

by

Impact

M

MAGADIITE

Magadiite is a hydrous sodium silicate mineral that was

discovered by Hans Eugstcr (1967) in late Pleistocene lake

sediments at Lake Mttgadi iti the southern Kenya Rifl Valley,

Although rare, magadiite is a well-knoun precursor of non-

niariiic chert. Qiiartzose "Magadi-lype cherts"", which have

fortncd by the diagenetic alteration of tnagadiite. have been

reported frotii rocks of Precambrian to Holocene

age,

Magadi-

type chert is generally considered diagnostic of

saline,

alkaline

lacustrine environments.

Magadiite [NaSi7Oi,(OH)v4H:O] and the telated sodium

silicates, kenyaitc Na^Sin.OjitOHls •6HO]. tnakalitc [Na^.

Si4O^,(OHb 4H.O]. and kancmite [NallSi.OiOHb 2H2O].

form mainly in hypersaline. sodiutn carbonate-rich brines

that have u pH > 9 atid consequently have high concentrations

of dissolved silica (up to 2,71)0 ppm). Sodiutn silicate tninerals

arc present at Lakes Magadi and Bogoria in Kenya. Lake

Chad,

and in some alkaline lakes in California and Oregon.

When fresh, magadiite is white, soft, putlylike. and easily

deformable. but it dehydrates rapidly on exposure to air. and

hardctis irreversibly to (brm a tine chalky aggregate. At high

magtiification. magadiite typically displays minute aggregates

of thin platy monoclinic crystals (<l()|,im) that may be equant

or have a sphcrulitic habit (Icole and Peritict. 1984; Scbag

etal..

2001),

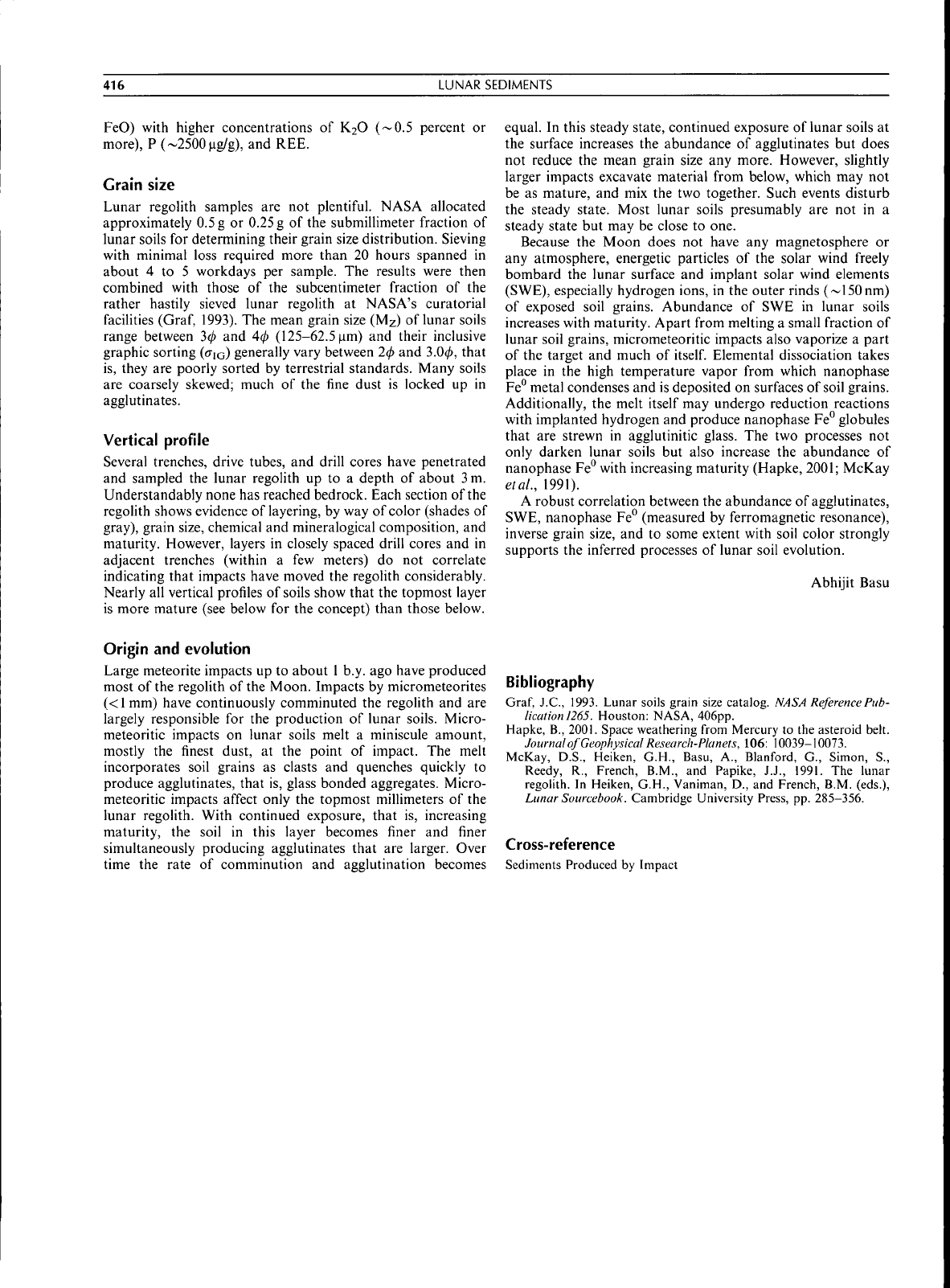

At Lake Magadi, magadiite tbrni beds a few decimeters

thick, lenses, and concretions with irregular protrusions, and

veins that Iratiscct bedding in zeolitic lacustrine silts

(Figure Ml), Hlsewhcrc. magadiite also tills cracks iu large

(tnctcr-scale) polygotis

(e.g,.

Alkali Lake, Oregon), or replaces

plants (Sebag(7<//.. 2001),

Formation of magadiite

Two geticral pathways have been proposed to explain the

formation of magadiite in silica-rich NaCO^ brines: a de-

crease in pH and evaporative concentration. At Magadi.

subhorizontal beds have been explained by seasotial precipita-

tion in a stratified saline, alkaline lake. Magadiite has been

inferred to precipitate when dilute inflow waters flow across a

dense,

sodium carbonate brine rich in dissolved silica and

lower the pH at the fluid interface (chemociine). At Lake Chad

and in some Americati examples, magadiite may have

precipitated by eviipotative concetitration or by capillary

evaporation of saline, alkaline brines ul a shallow subsurface

water table. Other inferred mechanisms include subsurface

mixitig of dilute and saline, alkaline groundwalers, a reduction

in pH of

an

alkaline brine resulting from an influx of biogenic

or geothermally sourced CO;, and precipitation from inter-

stitial brines. Different sodium silicate tninerals may fonn

according to the concentrations of Na and SiO- in the brine.

Conversion to chert

At Magadi, beds of tnagadiite pass laterally into quartzose

cherts confirming their genetic relationship, Magadi-type

cherts form beds, plates, and lobate nodules, commonly with

features indicating soft-sediment deformation upon compac-

tion.

Reticulate line eracks, salt crystal pscudomorphs or

molds, and relict spherulites are also cotnmon.

The conversion of magadiite to quartz is rapid and involves

a loss of sodium, water, and volume. Leaching by percolating

meteoric water, dehydration, and spontaneous reerystalliza-

tion due to sorption of silica by clays, have been proposed.

Intermediate diagenetic products, including kcnyaite. amor-

phous silica and tnoganite. may form during the transforma-

tion (kole and Perinet, 1984: Sheppard and Gudc. 1986). Both

magadiite and the associated cherts have a distinctive trace

element signature unlike other cherts.

Although the genetic models are well established and

magadiite is easily synthesized in the laboratory, few natural

examples of modern precipitation have been documented.

Recently Behr (2002) has shown that many of the cherts at

Lake Magadi may have been precipitated as amorphous silica

by bacteria and may not have had a sodium silicate precursor.

Similarly, many ancient continental cherts resemble Magadi-

type cherts in morphology and fabric, but are utilikely to have

had a magadiite precursor. The discovery of magadiite in

418

MAGNETIC PROPERTIES OE SEDIMENTS

Figure

Ml In

situ nuij^adiilc

iii

ilic

I

li^li Maj;Lidi Beds

Jl ihe

southern

end

of

Lake Mdgadi, Kenya. Soft while mtisses and thin streaky lenses

of m.igadiite Arc present

in

darker lacustrine silts that were deposited

when Lake Magadi

was

a deeper, fresher, and probably stratified lake.

cavities

in

volcanic rocks

in

Namibia

and

Quebec,

and in hot

springs deposits

at

Lake Bogoria

in

Kenya, shows that

it is not

restricted

to

lacustrine environments. Much remains

to be

learned about natural sodium silicates

and

their diagenesis,

Robin

W.

Renaut

Bibliography

Bell!', H,J,. 2002, Magadiiieand Magadi-chcrt:

a

critical analysis oflhe

silica sediments

in the

Lake Magadi basin. Kenya,

In

Rcnaiil.

R,W,.

and

Ashley.

G,M.

(eds,), Sedinictitaticn

in

Continental

Rifts. SEPM. Society

for

ScdimciiUiry Geology, Special Publica-

tion, 7,1,

(In

Press),

Eugster,

H.P.. 1967,

Hydrnus sodium ?,ilicalL's from L;ike Magadi,

Kenya; precursors

of

bedded chert, Scienee.

157: 1177 1180,

lcolc,

M,, and

Perinet,

G,, 1984, Les

silieates .sodiqucs

et les

milieux

cvLiporitiques carbonates bicarbotiates sodiques:

une

revue, Reyiic

de

Gi'alogie

Dynamiqueet dc Geographic

Physiquf.

25;

I f>7

176.

Sebag.

D,,

Verreecliia. F.,P,. Seong-Joo,

L,. and

Durand.

A,,

2(101,

The

natural hydrous sodium silicates from

the

northern bimk

of

Lake

Chad: occuirence. petrology

and

genesis. Sedimentary Geology.

139:

15 31,

Sbeppttrd,

R,A,. and

Gude,

A,J,,

I9S6, Magadi-type cherl

a

distinctive diagenetic variety from lacusirine deposits.

In

Mumpton.

F,A.

(ed.). Studies

in

Diagenesis,

US

Geological Survey

Bulletin, 1578,

pp,

335-345,

Cross-references

Lactistrine SedimentiUioii

Siliceous Sedimenls

MAGNETIC PROPERTIES

OF

SEDIMENTS

back

to the

tiiagnetic properties

of

their mineralogical

constituents which obviously tnay vary with sediment type,

provenance area,

and

depositional setting. Magnetic properties

ot"

any

material

are

directly related

to its

electronic structure,

notably

the

presence

or

absence

of

uncompensated electron

spins,

and the

presence

or

absence

of

collective spin behavior.

Any tnovitig electric charge creates

a

magnetic field: thus aiso

electrons that orbit atotnic nuclei

and

spin around their

own

axes,

are

microscopic tnajznets.

The

magnetic tnotncnt

of an

individual electron spin

is

termed

the

Bohr magneton.

The basic classes

of

magnetistn

are

diamagnetism. pata-

magnetism

and

ferroniagnetism.

If

there

are no

uncompen-

sated electron spins,

a

material

is

ilianmgnetic. This

situation occurs

for

example

in

calcite (CaCOi), dolomite

(CaMgiCO;,):). quartz (SiO.),

or

fbrsteritc (MgSiO.,)-

The

susecptibility

is the

magnetic moment

ofa

substance measured

in

an

applied tiiagnetic lield divided

by the

applied field,

Diamagnetic tninerals have

a

stnall

and

negati\e susceptibility

(Table

Ml),

that

is. the

direction

of the

sample's magnetic

moments opposes that

of the

applied field. Diamagnetism

is

independent

of

temperature.

If there

are

uncompensated electron spins

in a

crystal

structure that behave independently

of

each other,

the

material

is paramagnetic. This occurs

for

example

in

silicates

and

carbonates that contain iron

or

manganese

(or

sotne other

transition elements), Biotite

and

clay minerals like illite often

contaiti

at

least some

Fe. and are

therefore paramagnetic

(Table

Ml).

Also ankerite Ca(Mg, FejCOi)^.

is

paramagnetic

because

the

magnetic motnent

of

uncompensated electron

spins

is

much larger than

the

diamagnetic moment

due to the

orbit

of the

electrons around (heir tespective atomic nuclei.

Paramagnetic tninerals have

a

stnall

and

positive susceptibility

because magtietic moments tend

to

align

to an

applied field.

The susceptibility

of

paramagncts

is

stnall because thermal

jostling randomizes

the

electron spins. Paramagnetism

is

inversely proportional

to

(absolute) temperature.

Forromagtu'lism "sensu lato"

and

pertiianent

or

retnancnt

magnetization

are

restricted

to

minerals that have collective

spin behavior.

In

certain crystallitie solids that contain

tratisitional eletnents

in

large amounts,

the

atomic nuclei

arc

sufficiently close

to

each other

to

have

the

orbits

of the

outet"most electrons overlapping with each other.

In

this

situation,

the

uncotnpensated spins tnay line

up and

their

individual magnetic moments ean

be

added

to get

macroscopic

magnetism. This situation

can

occur

in

metals, oxides

and

sullidcs. The corresponding minerals are referred to as magnetic

minerals.

In

nature,

the

transition element

of

most interest

is

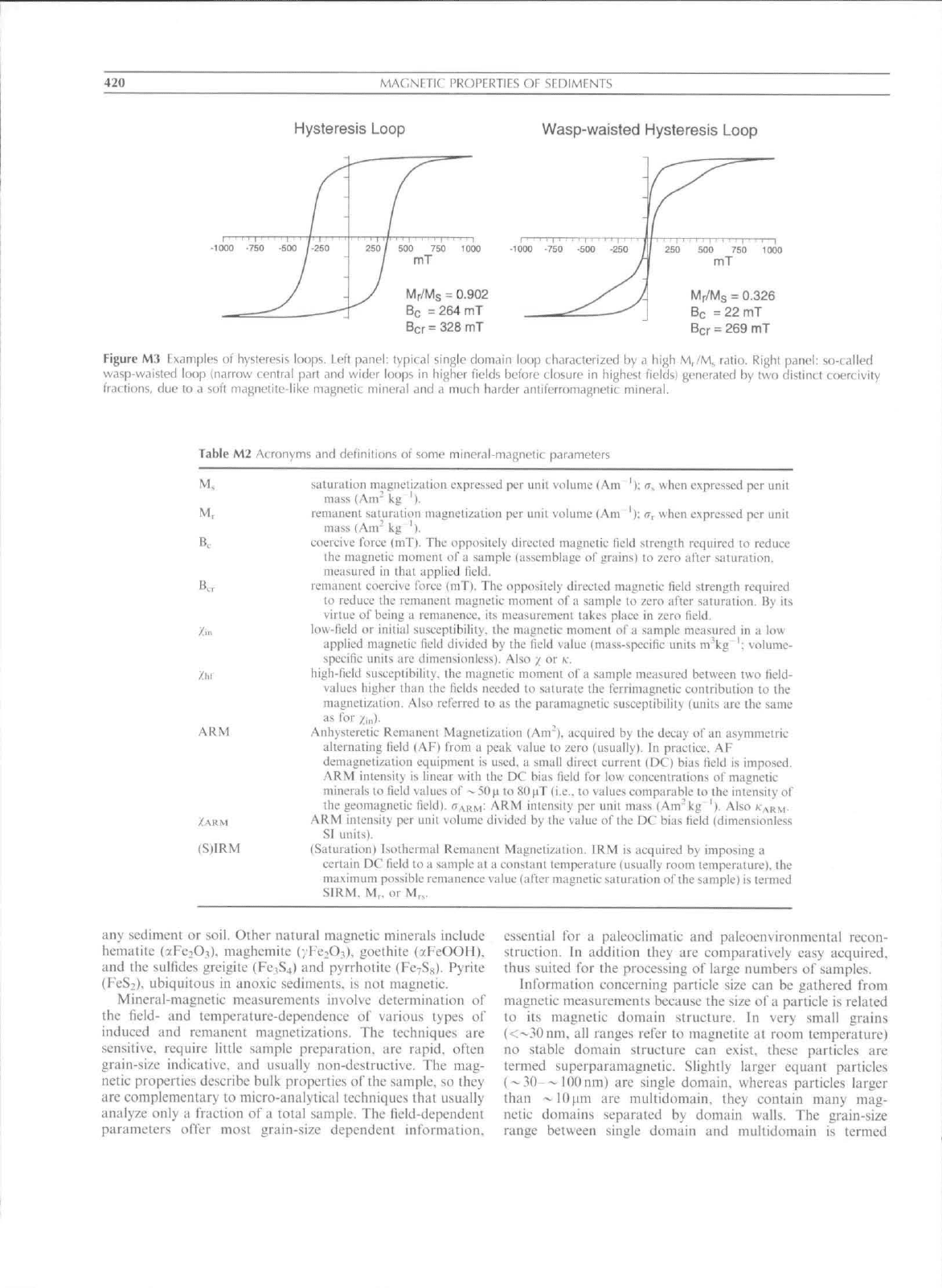

iron. Various types of collective spin behavior are distinguished

(Figure

M2),

Ferro-

and

ferrimagnetic material have

a

very

high susceptibility while antiferrotnagnets have

a

susceptibility

cotnparable

to

paratnagnets

(cf.

Table

Ml), The

field

and

temperature dependence

of (he

susceptibility

is

complex.

At a

certain temperature—natned

the

Curie temperature, character-

istic

of the

material —thermal jostling becotnes stronger than

the collective spin interaction changing

the

ferromagtietic

structure into

a

paramagnetic structure.

On

cooling through

the Curie temperature,

the

ferromagnetic structure

is

restored.

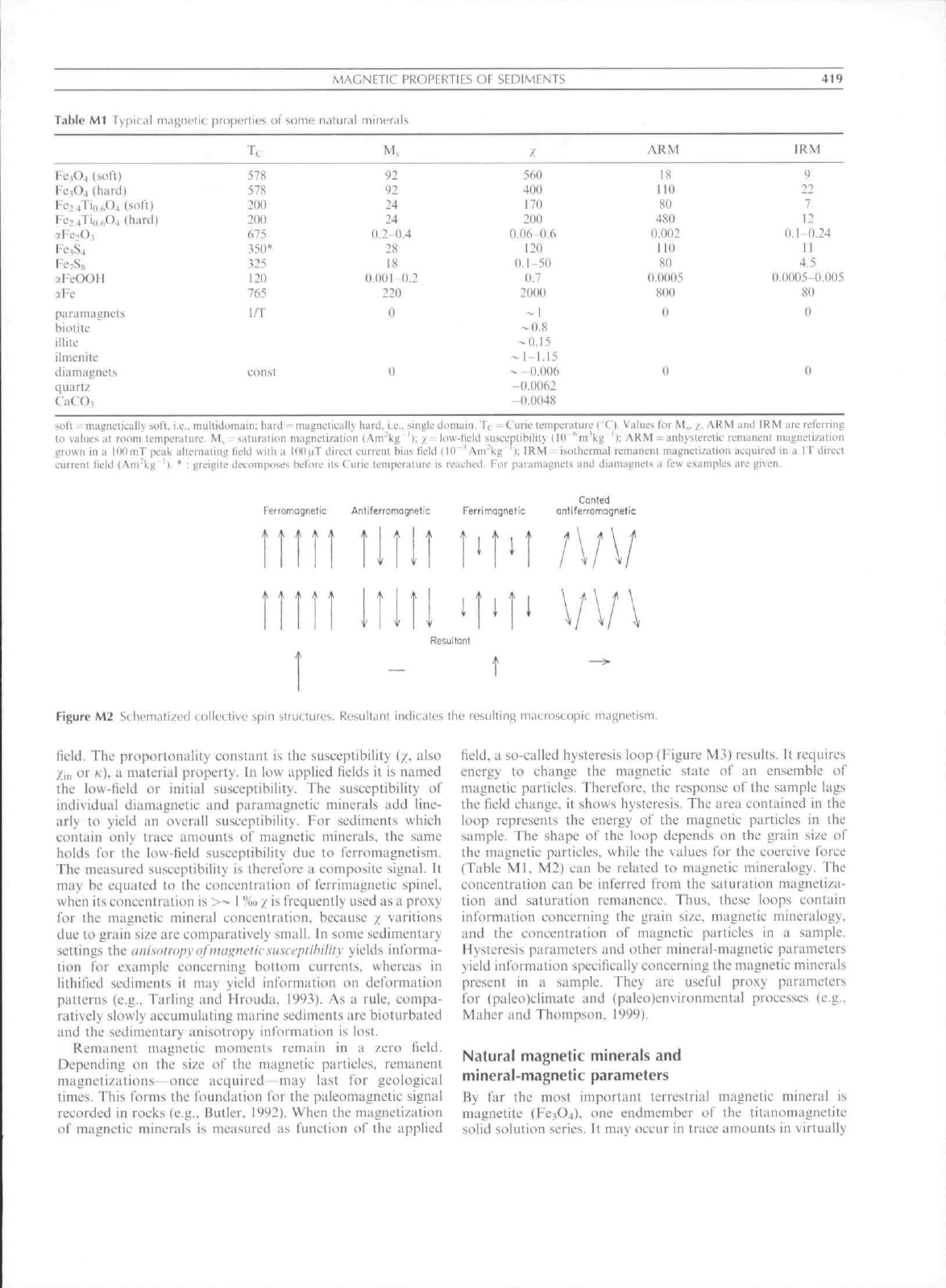

Introduction—classes of magnetism

Seditnents

are

aggregates

of

minerals, including silicates,

carbonates

and

trace amounts

of

various oxides

and

sulfides.

The tnagnetic properties

of

seditnents

can

therefore

be

traced

Induced

and

remanent magnetization

Diamagnetic

and

paratnagnetic moments

are

"induced"

magnetic moments: they only exist

in an

applied magnetic

field.

The

magnetic moment

is

proportional

to the

applied

Table Ml Tv|ilic.il magnetic

MAGNETIC

pruficrties of some natural niinfra

Tt M,

PROPERTIES OF SEDIMENTS

/

ARM

419

IRM

Fc,04 (solt)

Fi;,04 (hard)

Fc:^4Ti,,hO4 (soft)

Fc:4Ti,i.,,O4 (hard)

3:Fe-.O,

Fc,S4

FciSs

JY-COOU

>Fc

pa Til magnets

biotite

illite

ilincnitc

tlia magnets

quartz

CaCO,

soil mai;ni.'iiL.allv ^o^l,

578

578

200

200

675

350

325

120

765

I/T

eon

i.e,. mullidoniaiii: h

92

92

24

24

0,2 0,4

28

18

0,00! 0,2

220

0

0

560

400

170

200

0,06-0,6

120

0.1-50

0,7

2000

-"

1

-0.8

-0.15

-1-1,15

- -O.(X)6

-0,0062

-0.0048

18

110

80

480

0.002

110

80

0,0005

800

0

0

9

22

7

12

0,1-0,24

11

4,5

0.0005-0.005

80

0

0

, mullidoniaiii: hard = magnetically hard, i,e,, single domain, T, - Cune lempeniturc t C). Values tor M,, /;, AKM and

I

KM are referring

til values :it room temix-raturc, M, ^Liturjtioii magnetization (Anrkg '): / = liiw-rn;ld susueptibility (IU "m'kg 'l: ARM = anhystcrctic remanent magnetization

jiroxvn in a ItlOmT peak alternating lield wiih a lOO^iT direct current bias tield 110 ' Am"kg ): IRM = isothermal rananent magnetization acquired in a IT direct

current tield

(,'\m"ka

' I, * ; grcigitc dfco in poses hefore its Curie temperature is reached. For paramagncts and diamagneis a (ew examples are given.

Ferfomagnetic

Antiferromagnetic

Ferrimagnelic

Conted

•ntiferromagnetic

Re

sul

to

ni

Figure M2 S( hem.ilized tollective spin structures, KosulLint inrlicates thf resulting macroscopic magnetism.

(icld.

The proporionality constant is the susceptibility (/, also

/jn or

K).

a material property. In low applied lields it is named

the low-field or initial stisceptibility. The susceptibility of

itidividual diatnagnetie and paratnagnetie minerals add line-

arly to yield an overall sitseeptibility. For sedimetits which

contain only trace amounts of magnetic minerals, the same

holds lor the low-field susceptibility due to ferrotnagnetisni.

The tneasured susceptibility is therefore a cotnposite signal. It

may be equated to the concentration of ferrimagnetic spinel,

when its concentration is >-•

1 %o /_

is frequently used

as a

proxy

for the magnetic mineral concentration, because y varitions

due lo grain size are comparatively stnall- In some sedimentary

settings the

attisotropy

of

ma^itwticsusceptibility

yields infortiia-

tion for example concerning bottom currents, whereas in

lithified sediments it may yield infonnation on deformation

patterns

le.g,,

Tarling and Hrotida, 1993). As a rule, conipa-

raiively slowly accumulating marine sediments are bioturbated

and the seditnenlary anisotropy infonnation is lost,

Retnanent tnagnetie moments remain in a zero

fteld.

Depending on the size of the magnetic partieles, remanent

magnetizations onee acquired may last for geological

times.

This forms the foundation for the paleomagnetie signal

recorded in rocks

(e,g,,

Butler, 1992), When the magnetization

of tiiagnetic minerals is measured as function of the applied

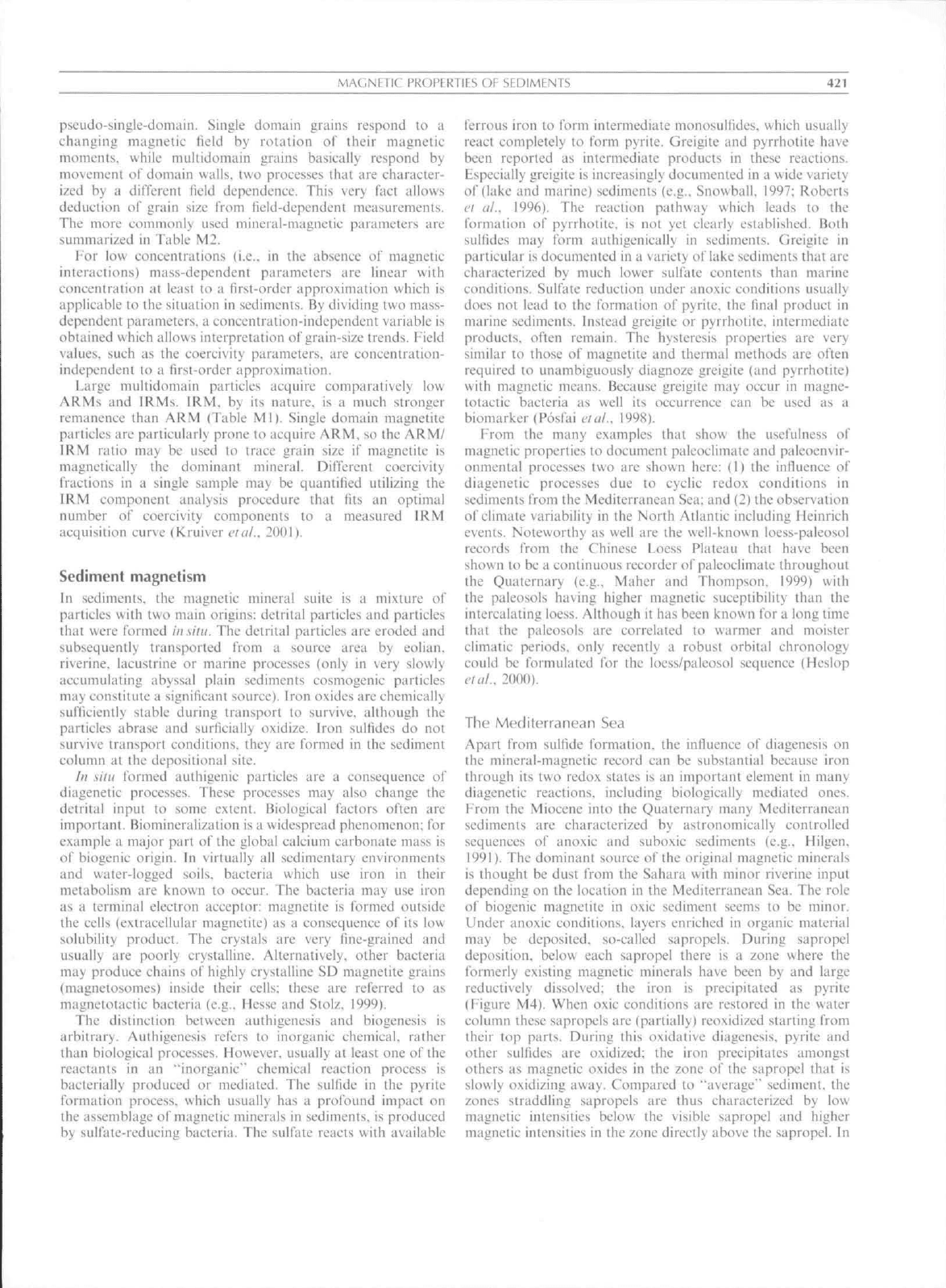

tield,

a so-called hysteresis loop (Figure M3) results. It requires

energy to change the magnetic state of an ensemble of

magnetic particles. Therefore, the response of the sample lags

the fteld ehange. it shows hysteresis, T"he area contained in the

loop represents the energy ol' the magnetic particles in the

sample. The shape of the loop depends on the grain size of

the tnagnetie particles, while Ihe values for the coercive force

(Table Ml. M2) can be related to magnetic tnineralogy. The

concentration can be inferred from the saturation magnetiza-

tion and saturation retnanence. Thus, these loops contain

infotmation concerning the grain size, magnetic mineralogy,

and the concentration of magnetic particles in a sample.

Hysteresis paratneters and other tnineral-magnetic parameters

yield information specifically concerning the magnetic minerals

present in a sample. They are usel'ul proxy parameters

for (paleo)cliinate and (palco)cnviromnental processes

(e.g..

Maher and Thompson, 1999).

Natural magnetic minerals and

mineral-magnetic parameters

By tar the nn)st itnportant terrestrial tnagnetic mineral is

tnagtietite (FeiO4). one endtnetnber of the titanotnagnetite

solid solution series. It may occur in trace amounts in virtually

420

MAGNFTIC

PROPERTIES

Or

SEDIMENTS

Hysteresis Loop

Wasp-waisted Hysteresis Loop

r/Ms = 0.902

e = 264 mT

cr

=

328 mT

Mr/Ms = 0.326

Be =22mT

Ber = 269 mT

Figure M3 Examples of hysteresis loops. Left panel: typical single domain loop characterized by a high M,/M^ ratio. Right panel: so-called

wasp-waisted loop (narrow central part and wider loops in higher fields before closure in highest fields) generated by two distincl coercivity

fractions, due to a soft magnetite-like magnetic mineral and a much harder antiferromagnetic mineral.

Table M2 Acronyms and definitions of some mineral-magnetic parameters

M^ sattiration tnagnctization expressed per unit volume (Am '):

n..

when expressed per unit

mass (Am~ kg ').

Mr remanenl saturation magnetization per unit volume (Am '); n, when expressed per unit

mass (Am" kg '),

Be

coercive foree (mT), The oppositely directed magnetic field sirenjith required to icditec

the

magnctie moment of a sample (assemblage of grains) to zero after

saturation,

measured

iti ihat applied

field,

Bcr

remanetit eocreive force

fniT),

The oppositely directed magnctie lield strength required

to

reduce the remanent magnetic tnomcnt of ;i sample to /ero after

saturation,

B\ its

virtue

of being ;i remanence. its measurement takes place in zero

field,

Xm

low-iidd or initial susceptibility, the magnetic moment ofa sample trteasurcd in a low

applied

magnetic field divided by the field vaiue (niiiss-specific units m'kg ': vo!ume-

specific

units are dimeiisionlcss). Also

/_

or K.

XM

high-fteld susceptibility, the magtietic tiiometit ofa sample measured between two

iield-

values

higher than the fields needed to saturate the ferritiiagnetic contribution to the

magnetizalion.

Also relerted to as the paramagnetic susceptibility (units are the same

as

for

•/,„).

ARM Anhysteretie Remanent Magnetization (Am'), acquired b> ihe decay of an asymttietrie

alternating lield (AF) from a peak value to zero (usually). In praeliec, AF

demagnetization equipment is used, a small direct current (DC) bias lield is imposed,

ARM intensity is linear v\ith ihe DG bias iieid for low concentrations o)'tnagnetie

minerals to fteld values of ^50fi to 80|,iT(i,e,. to values comparable to the intensity of

the geomagnetic lieid),

RARM:

ARM inlensily per unit mus.s (Am"kg '). Also

KARM-

ZARM

ARM

intensity per unit volume divided by the value of the DC bias iieici (dimensionless

Si units),

(S)IRM (Saturation) Isothermal Remanent Magnetization, IRM is acquired by imposing a

certain DC tield to a sample at a constant temperature (usually room temperature), the

maximum possible remanenee value (after magnetic saturation of

the

sample) is lermcd

.SiRM.

M,. or M,,,

any sediment or

soil.

Other nalural magnetic tiiitierals include

hetnatite (3:Fe2O3), maghetnite (•/Fe^Oi), goethite (aFeOOH).

and the sulfides greigite (Fe.^S4) and pyrrhotitc (FeySw). Pyrite

(FeS:). ubiquitous in anoxic sediments, is not magnetic.

Mineral-magnetic measurements involve determination of

the tield- and temperature-dependence of various types of

induced and remanent tnagnetizations. The techniques are

sensitive, require little sample preparation, are rapid, often

grain-size indicative, and usually non-destructive. The mag-

netic properties describe bulk properties of the satnple, so they

arc cotnplementary to micro-analytical techniques that itsually

analyze only a Traction of a total sample. The fteld-dependcnt

parameters oiTer most grain-size dependent inlbrination.

essential for a paleoclimatie and paleoenvironmental recon-

struction.

In addition they are comparatively easy acquired,

thus suited for the processing of large numbers of satnples.

Information concerning particle size can be gathered from

magnetic measurements because the size ofa particle is related

to its magnetic domain structure. In very small grains

{<--30nm,

all ranges refer to magnetite al room tetnperature)

no stable domain structure can exist, these particles are

termed superparamagnetic. Slightly larger equant particles

( - 30-"-lOOnm) are single domain, whereas particles larger

than -• l()|,tm are multidomain, they contain many mag-

netic domains separated by domain walls. The grain-size

range between single domain and multidomain is tenned

MAGNETIC PROPERTIES OF SEDIMENTS

421

pseudo-single-domain. Single dotnain grains respond to a

changing magnetic field by rotation of iheir magnetic

motnents. while muitidomain grains basically respond by

tnovement of domain walls, iwo processes that are character-

ized by a difTerent field dependence. This very fact allows

deduction of grain size from Held-dependent measurements.

The tnore comtnonly used mineral-magnetic paratnelers are

sutnmarized in Table M2.

For low concentrations

(i.e..

in the absence of magnetic

interactions) mass-dependent parameters are linear with

concentration at least to a first-order approximation which is

applicable to the situation in sediments. By dividing two mass-

depetident paratneters. a concentration-independent variable is

obtained uhich allows interpretation ol'grain-size trends. Field

values, such as the coercivity paratneters. are concentration-

independent lo a tirsi-order approxitnation.

Large tnultidotnain particles acquire comparatively low

ARMs and IRMs. IRM, by its nature, is a tnuch stronger

remanence than ARM (Table Ml), Single domain magnetite

particles are particularly prone to aequire ARM, so ihe ARM/

IRM ratio may be used to irace grain size if magnetite is

magnetically the dominant mineral. Different coercivity

fracliotis in a single sample may be quantified utilizing ihe

IRM cotnponent analysis proccditre that fits an optimal

number of coercivity components to a measured IRM

acquisition curve (Kruiver

etal...

2001),

Sediment magnetism

In sediments, the magnetic mineral suite is a tnixture of

particles with two main origins: detrilal particles and particles

that were formed ittsitii. The detrital particles are eroded and

subsequently transported from a source area by eolian.

riverine, lacustritie or marine processes (only in very slowly

accumulating abyssal plain sediments eosmogenic particles

may constitute a significant source). Iron oxides are ehemiealiy

sufficiently stable during transport to survive, although the

panicles abrase and surficially oxidize. Iron sultides do not

survive transport cotiditions, they arc fortned in the sediment

eoiumti at ihe deposilional site.

In situ fortned attthigenic particles are a consequence of

diagenetic processes. These processes may also change the

detrital input to some extent. Biological factors often are

important. Bioniineraiization is a widespread phenomenon; for

exatnple a tnajor part of the global calcium carbonate mass is

of bi{)genic origin. In virtually all sedimentary environments

and water-logged soils, bacteria whieh use iron in their

tnelabolism are known to occtir. The bacteria may use iron

as a tertninal electton acceptor: magnetite is (brnied outside

the cells (extraeellular magnetite) as a consequence of its low

solubility product. The crystals are very fine-grained and

usually are poorly crystalline. Alternatively, other bacteria

may produce chains of highly crystalline SD magnetite grains

(magnetosomes) inside their cells; these are referred to as

magnctotaclic bacteria

(e.g..

Hesse and Stolz, 1999).

The distinction betweeii authigencsis and biogenesis is

arbitrary. Authigenesis refers to inorganic chemical, rather

thati biological processes. However, usually at least one of the

reactants in an "inorganic" chemical reaction process is

bactcrially produced or tnediated. The sulfide in the pyrite

fot-malion process, which usually has a profound impact on

the assemblage of magnetic minerals in sediments, is produced

bv sulfate-reduciniz bacteria. The sull'ate reacts with available

ferrous iron to

i'orm

intermediate monosullides. which usually

read completely to form pyrite, Greigite and pyrrhotite have

been reported as intertnediate products in these reactions.

Fspecially greigite is increasingly docutnented in a wide variety

of (lake and tnarine) sediments

(e.g..

Snowball, 1997; Roberts

el al.., 1996). The reactioti pathway which leads to the

formation of pyrrhotite, is nol yel clearly established. Both

sulfides may fortn authigenically in sediments. Greigile in

particular is documetited in a variety of lake sediments that are

characterized by much lower sulfate contents than marine

conditions, Sulfate reduction under anoxie conditions usually

does not lead to the formation of pyrite. the final product in

marine sediments. Instead greigite or pyrrhotite. intermediate

products, often retnain. The hysteresis properties are very

similar to those of tnagnetite and thermal methods are often

required to unambigitously diagnoze greigite (and pyrrhotite)

with magnetic means. Because greigite may occur in magne-

lotactic bacteria as well its occurrence can be used as a

biomarker (Posfai

etal..

1998).

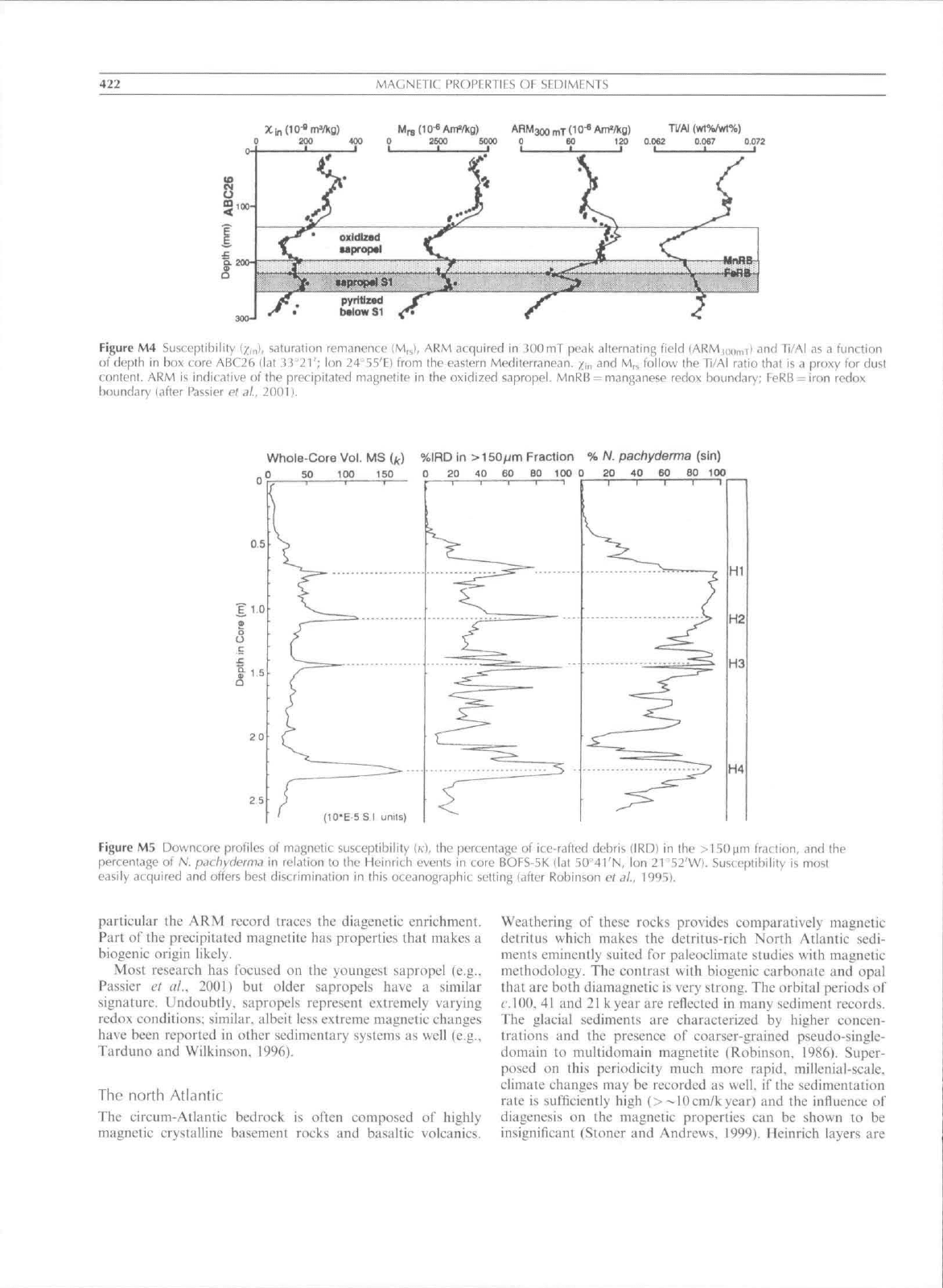

From the many examples that show the usefulness of

magnetic properties to document paleoclimate and paleoenvir-

onmental processes two are shown here: (1) ihe influence of

diageneiic processes due to cyclic redox conditions in

seditnenls from the Mediterranean Sea; and (2) the observation

of climate variability in the North Atlantic including Heinrich

evenis. Noteworthy as well are the well-known loess-paleosol

records from the Chinese Loess Plateau that have been

shown to be a continuous recorder of paleoclimate throughout

the Quaternary

(e.g,,

Maher and Thotnpson, 1999) with

the paleosols having higher magnetic sucepiibility than the

intercalating loess. Although il has been known for a long time

that the paleosols are correlated to wartner and moister

climatic periods, only recently a robust orbital chronology

could be formulated for the loess/paleosol sequence (Hcsiop

etal..

2000).

The Mediterranean Sea

Apart iVom sulfide formation, ihe influence of diagenesis on

the mineral-tnagnetic record can be substantial beeausc iron

through its two redox states is an important element in many

diagenetic reactions, iticluding biologically mediated ones.

Frotn the Miocene into the Quaternary many Meditcrratiean

sediments are characterized by astronomically controlled

sequences of anoxic and suboxic sediments

(e.g.,

Hilgen.

1991). The dominant source of the original magnetic minerals

is thought be dust from the Sahara wilh tninor riverine input

depending on the location in the Mediterranean Sea. The role

of biogenic magnetite in oxic sediment seems to be tninor.

Under anoxic conditions, layers etiriehed in organic material

may be deposited, so-called sapropels. During sapropel

deposition,

below each sapropel there is a zone where the

formerly existing magnetic minerals have been by and large

reductively dissolved; the iron is precipitated as pyrite

(Figure M4). When oxic conditions are restored in the water

column these sapropels are (partially) reoxidized starling Irom

their top parts. During this oxidative diagenesis. pyrite and

other sulfides are oxidized; the iron precipitates amongsl

others as magnetic oxides in the zone of the sapropel thai is

slowly oxidizing away. Compared to "aveiagc" sediment, the

zones straddling sapropels are thus characterized by low

magnetic intensities below the visible sapropel and higher

magnetic intensities in the zone directly above the sapropel. In

422

MAGNETIC PROPERTIES OF SEDIMENTS

Ti/AI (wt%/¥rt%)

Figure M4 Susceptibility

(/;,„),

saturation remanence (M,^), ARM acquired in JOOmT peak alternating field (ARMi,,,,,,,!) and Ti/Al as a function

of depth in box core ABC26 (!at J.i

'21';

Ion 24^55'E) from the eastern Mediterranean. /„, and M,., follow the Ti/Al ratio that is a proxy for dust

content, ARM is indicative of (he precipitated majinetite in the oxidized sapropel, MnRB = manganese redox boundary; FeRB = iron redox

boundary (after Passier e( ^/., 2001).

Whole-Core Vol. MS (if)

,0 50 100 150

25

%IRD in >150|jm Fraction % N.

pachyderma

(sin)

0 30 40 60 eo 100 0 20 40 60 60 100

H4

Figure M5 Downcore profiles of magnetic susceptibility

IK),

the percentage of ice-rafted debris (IRD) in the >150Mm fraction, and the

percentage of N. pachyderma in relation lo the Heinrirh events in core BOES-5K (lat 50MrN, Ion 21 52'W). Susceptibility is most

easily acquired and offers best discriminaticin in this oceanographic setting (after Kobinsoti ef JI

particular the ARM record traces the diagenetic enrichment.

Part of the precipitated magnetite has properties that makes a

biogenic origin likely.

Most research has focused on the youngest sapropel (e,g..

Passier et it!,, 2001) but older sapropels have a similar

signature. Undoubtly. sapropels represent extremely varying

redox conditions; similar, albeit less extreme magnetic changes

have been reported in other sedimentary systems as well (e.g..

Tarduno and Wilkinson. 1996).

The north Atlantic

The circum-Atlantic bedrock is often composed of highly

magnetie crystalline basement rocks and basaltic volcanics.

Weathering of these rocks provides comparatively magnetic

detritus which makes the detritus-rich North Atlantic sedi-

ments eminently suited for paleoclimate studies with magnetic

methodology. The contrast with biogenic carbonate and opal

that are both diamagnetic is very strong. The orbital periods of

(,1(K), 41 and 21 kyear are refleeted in many sediment records.

The glacial sediments are eharaelerized by higher concen-

trations and the presence of coarser-grained pseudo-single-

domain to multidotnain tnagnetite (Robinson. 1986). Super-

posed on this periodicity mueh more rapid, milleniat-scalc.

climate changes may be recorded as well, if the sedimentation

rale is sufficiently high (>-IOcm/kyear) and the influence of

diagenesis on the magnetic properties can be shown to be

insigtiificanl (Stoner and Andrews. 1999). Heinrich layers are

MAGNFTir PROPERTIES

OE

SEDIMENTS 423

k(SI)

D.OOI

0.002

SIRM (A/m)

IS

20 2S

30

0

0.005

0.01

O.OIS

200

300

a.

600

700

800

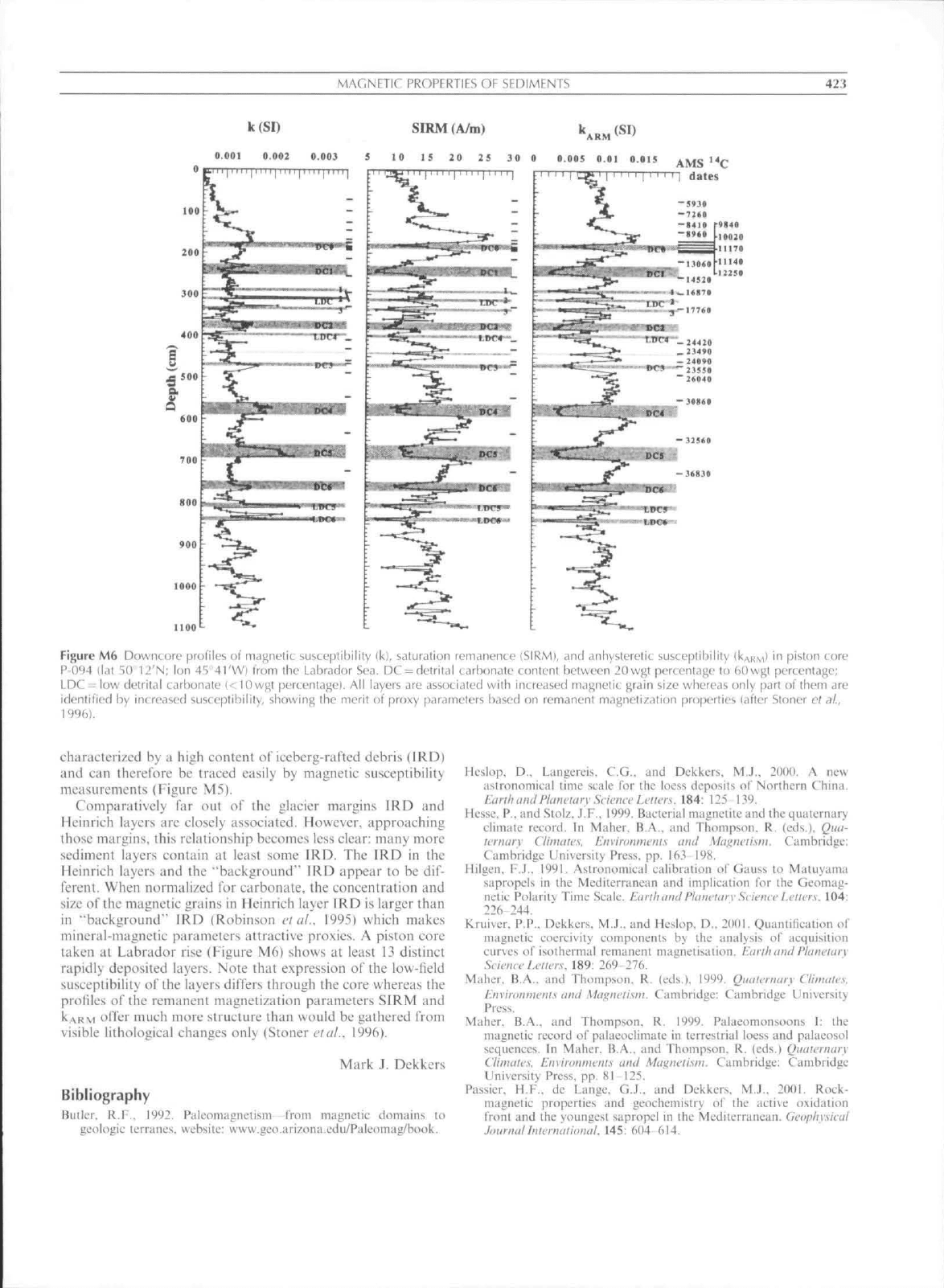

Figure

M6

Uowncore profiles

of

magnetic susceptibility (k), Stituration remanence (SIRM), and anhysterelic susceptibility

(k^^M'

in

piston core

P-094

ildt

50

12'N;

Ion 43

41'W) from

the

Labrador Sea, DC

=

detrital Larbonate content between 20w^t percentage

to

(>t)wgt percentage;

LDC

- low

detrital carbonate

(<;1G

wj;!

pfrcentagei.

All

layers are associated wilh increased magnetic grain size whereas only part

of

them

are

identified

by

increased susceptibility, showing

the

merit

of

proxy parameters based

on

remanent magnetization properties (after Sioner et

^^1.,

i;har;it:tcri/i:d by ;t high cotitcnt of" iccbcrg-raftcd debris (IRD)

;ttid

c;tti

ihererorc be traced easily by magtietic susceptibility

measitrctiictils (Figure M5).

ConiparLitivcly far out of the glacier margins IRD atid

Heitirich layers are closely associated. However, approaching

those margins, this relatiotiship becomes less clear: many more

sediment layers contain at least some IRD. The IRD in the

Heinrich layers atid the "background" IRD appear to be dif-

ferenl. When normalized for carbonate, the concentralion and

si/e of the magnetic grains in Heinrich layer IRD is larger than

in "background" IRD (Robinson etal.. 1995) which makes

mineral-tnagnctic paratneters attractive proxies. A piston core

taken at Labrador rise (higiire M6) shows at least 13 distinct

rapidly deposited layers. Note that expression of the low-field

susceptibility of the layers differs through the core whereas the

profiles of the remanent tnagnetization paratneters SIRM and

l^AKM offer tnuch more structure than would be gathered from

visible lithological changes only (Stoner et al.. 1996).

Mark J, Dekkers

Bibliography

Huller.

R.F,. 1992,

Paleoniagnetistn—from magnetic domiiins

to

geologic terranes. website: wu'\v,geo,ari7ona,cdu/Pa!eomag/book.

Hoslop,

D,.

Langereis,

C,G,, and

Dekkers.

M,J,,

2000.

A new

iistronomical time scale

for the

loess deposits

of

Northern

C

hina.

Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 184:

125 139.

Hosse. P,.

and

Stolz, J,F.. 1999, Bacterial mugnetite

and

the quaternary

climate record.

In

Maher.

B,A,. and

Thompson,

R,

(eds,).

Qua-

ternary Climates. Enyironnu-nts

and

Magnetism. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press,

pp, 163 198,

Hilgen.

h,J,.

1991, Astronomical calibration

of

Gauss

to

Matiiyama

sapropels

in the

MedUerraiiOLiii

and

implication

for the

Geomag-

netic Polarity Titne Scale. Earth ami

I'linu-tary

Science Letters.

104:

226-244.

Kruiver. P,P.. Dckkcrs.

MJ.. and

Hcsiop.

D..

2111)1.

Oi'antitication

oi

magnetic coereivity components

by Ihe

analysis

of

acqtiisition

curves

of

isothermal remanent magnetisation. Earth and Phmctary

Science Letters. 189:

2(i9 276,

Maher.

B,A,, and

Thompson.

R,

(eds,),

1999,

Quaternary Climates.

Enyironments

and

.Magnetism, Cambridge: Cambridge liniversity

Press,

Maher.

B.A,. and

Thompson.

R, 1999.

Palaeomonsoons

I: the

magnetic record

of

palaeoclimatc

in

terrestrial loess

and

palaeosol

sequences.

In

Maher. B,A,.

and

Thompson.

R,

(eds,) Quaternary

Climates. Environments

and

.Magnetism. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press,

pp,

81-125,

Passier.

H.F.. de

Unge,

G.J,, and

Dekkers.

M.J,, 2001.

Rock-

magnetic properties

and

geochemistry

of the

aclive oxidatioti

front

and the

youngest sapropel

in the

Mediterranean, Geophysical

JournalInlcrnational. 145:

604 614,

424 MASS MOVEMENT

Posfai,

M,,

Buseck,

P,R,,

Bazylinski,

D.A., and

Franket,

R.B.,

t998.

Reaction sequences

of

iron sultide minerals

in

bacteria

and

their

use

as

biomarkers. Scienee, 280: 880-883.

Roberts, A,P,, Reynolds,

R,L,,

Verosub, K,L,,

and

Adam, D,P,,

1996,

Environmental magnetic implications

of

greigite (Fe3S4) formation

in

a

3 million years lake sediment record from Butte Valley,

northern California.

Geophysieal

Researeh Letters, 23: 2859-2862.

Robinson,

S.G,, 1986, The

late Pleistocene palaeoclimate record

of

North Atlantic deep-sea sediments revealed

by

mineral-magnetic

measurements, Physiesofthe Earthand Planetary Interiors, 42: 22-47,

Robinson,

S,G,,

Maslin,

M.A., and

McCave,

N., 1995.

Magnetic

susceptibility variations

in

upper Pleistocene deep-sea sediments

of

the N.E. Atlantic: implications

for ice

rafting

and

palaeocirculation

at

the

Last Glacial Maximum. Paleoeeanography,

10:

221-250,

Snowball,

t.F.,

1997. Gyroremanent magnetization

and the

magnetic

properties

of

greigite-bearing clays

in

Southern Sweden. Geophysi-

eal Journal International, 129: 624-636.

Stoner,

J,S,, and

Andrews,

J.T., 1999, The

North Atlantic

as a

Quaternary magnetic archive,

tn

Maher,

B.A,, and

Thompson,

R,

(eds.) Quaternary Climates, Environments

and

Magnetism.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

pp.

49-80.

Stoner,

J.S,,

Channell, J.E.T.,

and

Hillaire-Marcd,

C, 1996, The

magnetic signature

of

rapidly deposited detrital layers from

the

deep Labrador

Sea:

relationship

to

North Atlantic Heinrich

Layers, Paleoeeanography, 11: 309-325.

Tarduno,

J,A,, and

Wilkinson,

S.L.,

1996. Non-steady state magnetic

mineral reduction, chemical lock-in,

and

delayed remanence

acquisition

in

pelagic sediments. Earth

and

Planetary Science

Letters, 144: 315-326,

Tarling, D.t-t.,

and

Hrouda,

F.,

1993, Magnetic Anisotropy. Cambridge:

Cambridge University t'ress.

Cross-references

Authigenesis

Bacteria

in

Sediments

Bedding

and

Internal Structures

Biogenic Sedimentary Structures

Carbonate Mineralogy

and

Geochemistry

Cyclic Sedimentation

Diagenesis

Diagenetic Structures

Eolian Transport

and

Deposition

Fabric, Porosity,

and

Permeability

Geophysical Properties

of

Sediments

Flydroxides

and

Oxyhydroxide Minerals

Iron-Manganese Nodules

Milankovitch Cycles

Neritie Carbonate Depositional Environments

Paleoeurrent Analysis

Red Beds

Sapropel

Sulfide Minerals

in

Sediments

Weathering, Soils,

and

Paleosols

MASS MOVEMENT

Introduction

Mass movemetit refers

to

processes

by

which soil

and

rock

materials move downslope under their

own

weight (Selby,

1993;

Turner

and

Schuster, 1996),

The six

principal movement

mechanisms

are

creep, sliding, flow, toppling, free-fall,

and

rolling. Given

the

spectrum

of

possible processes, mass

movement deposits exhibit

a

wide range

of

sedimentological

features

and

surface morphology. Most deposits

are

typically

poorly sorted, unstratified clastic aggregates (i,e,, diamictons)

with predominantly angular clasts

of

local provenance.

Deposits associated with rapidly flowing events, such

as

debris tlows

and

rock avalanches, often exhibit crude

stratification

and

inverse grading.

The

typical morphologies

of mass movement deposits

are

colluvial cones

and

fans,

planar colluvial blankets, linear ridges

and

lobes,

and com-

plex hummocky forms.

The

latter have often been confused

with glacial drift deposits. Given

the

shear strength

of

many

landslide materials, some

are

emplaced

at

relatively steep

angles (5°-l5°)

and

therefore violate

the

Principle

of

Original

Horizontality, Such deposits require cautious structural inter-

pretation when encountered

in

ancient lithitied assemblages.

Strength

of

hillslope materials

Detachment

of

material from

a

slope

as a

slide

or

fall requires

that shear stress,

due to the

downslope component

of

the bulk

weight

of the

material, equals shear strength along

a

plane

of

detachment,

as

described

by the

Mohr-Coulomb equation:

s

= c'

-\-

{(7

— u)tan (

(Eq,

1)

where

s is

shear strength,

c' is

cohesion,

a is

total normal

stress,

u is

pore water pressure,

and

cj)'

the

angle

of

shearing

resistance. Term (a—u)

= a' is

effective normal stress (Craig,

1997),

Cohesion

is

associated with either clay

or

cementing

material. Clay cohesion

is a

function

of the

load history

of a

material, being relatively

low (<

10

kPa)

in

recently deposited

muddy deposits,

and

relatively high (>100kPa)

in

over-

consoiidated clay-shale formations (Selby,

1993;

Craig,

1997),

Angle

of

shearing resistance,

(/>',

controls

the

steepest

stable slope

for a dry

frictional material,

and

depends

on

particle angularity, mineralogy,

and

packing density.

It is

highest

in

dense deposits

of

angular quartz-feldspathic grains

(35°-45°),

and

lowest

in

low-density deposits

of

clay (5°-15°)

(Kenney, 1984), Clay mineral species also controls frictional

strength, being highest

in

kaolinite, intermediate

in

illite,

and

lowest

in

montmorillonite. Shear strength also depends

on

material displacement history. First-time failures

in

soil

and

rock mobilize peak strength, comprising in situ cohesion

and

friction

due to

maximum grain

or

rock-joint interlocking

(Craig, 1997), Small shear displacements,

of the

order 0,1

m,

cause substantial loss

of

cohesion

and a

reduction

of

frictional

resistance

due to

shear dilatancy

and the

development

of

preferred grain alignments.

The

resultant ultimate

or

residual

strength

is

appreciably lower than

the

original peak value

(Craig, 1997), This means that surfaces which have experi-

enced past movements

are

predisposed

to

continued move-

ment. Similar reduced strength commonly occurs along

tectonically sheared rock surfaces.

On slopes where soil

is

significantly reinforced

by

tree roots,

a third strength component termed root reinforcement,

c'r,

exists.

It is

significant

on

slopes with relatively thin

(<2m)

mantles

of

colluvial material

or

weathered glacial drift. Since

most mountain soils

are

relatively thin, landslide events,

and

hence regional sediment tlux

to

depositional areas,

are

strongly

regulated

by

plant cover

and its

degree

of

anthropogenic

disturbance (Sidle etal., 1985),

Causes

of

mass movement events

Slope failure

as a

landslide

may be

induced

by an

increase

in

shear stress,

a

decrease

in

shear strength

or

both. Shear stress

increase, coupled with shear strength decrease, typically occur

when materials

are

water saturated

by

rainfall

or

snowmelt.