Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PEAT

515

conductivity, and be devoid of aerobic microfauna and

bacteria. A lower layer or catotelm will develop with

characteristics quite distinct from the acrotelm layer on the

surface (Ingram, 1978). Decay processes are generally fast

immediately following death of the plant and slow down

considerably as the peat enters and continues to reside in the

catotelm. The acrotelm is the primary peat-forming layer

where decay processes predominate compared to the catotelm.

Decay continues in the catotelm but at rates several orders of

magnitude less than in the acrotelm. Peat that makes it into the

catotelm is preserved for several hundreds and thousands of

years following death of the plants.

Waterlogging, therefore, is the key ingredient leading to peat

accumulation. Because the diffusion of oxygen is many orders

of magnitude slower in water than in air, the low oxygen

regime brought about by waterlogging, leads to accumulation.

If waterlogging is interrupted in any one year, no peat will

make it into the catotelm and no net accumulation will occur.

If dry conditions persist over several years, it is possible that

catotelm peat may become re-exposed to oxygen, and the

peatland will degrade.

Peat landforms with acrotelm and catotelm layers, and

hence, actively forming and accumulating peat are referred to

as mires. Such two-layered mires are diplotelmic (Ingram,

1978).

The term peatland originates from the early writings

where peatland was used to describe any land area covered by

peat (Gorham, 1953). It is also probably a shortened version

for "peat landform" in geomorphology that refers to the biotic

landforms formed of peat. In North America mire is generally

not recognized, and instead, peatlatid is used in the broadest

sense to denote any peat landform irrespective of whether it is

diplotelmic or not and whether it is actively forming and

accumulating peat or not. In Europe and Russia, there is a

tendency to differentiate actively peat-accumulating mires

from the more generic peatland term, which applies to all

peatiands regardless of actively peat-accumulating or not.

The term haplotelmic is used when only the catotelm

remains (Ingram, 1978). Erosion or human alteration are the

primary forces responsible for eliminating the acrotelm.

Whether natural aging of the peat-accumulating system can

also contribute to disappearance of the acrotelm is less clear,

such as polygon peatiands in Arctic Canada (Vardy and

Warner, 2002).

A maximum depth for peatiands is unbounded. Average

depth globally has been estimated to be

1.3-1.4

m (Lappalainen,

1996) and a maximum of

15

m is rarely exceeded (Clymo, 1983).

At the other end of the spectrum, it has been customary to

take an arbitrary minimum depth of 30, 40, or 50cm. In

diplotelmic systems, the catotelm is the thicker being several

meters compared to the thinner acrotelm, which usually is not

much more than 0.5-0.75 m.

Attributes of peat

It is possible to define peat in two ways. The first, and most

common, is to define peat as a substance derived from

peatiands and/or mires that is composed of the partially

decomposed remains of plants with over 65 percent organic

matter (dry weight basis) and less than 20-35 percent

inorganic content (Clymo, 1983; Heathwaite etal. 1993). It is

also possible to define peat in its intact or natural state (i.e., in

the mire or peat land) as 88-97 percent water, 2-10 percent

dry matter and 1 percent to 7 percent gas (Heathwaite etal..

1993).

Botanical composition and state of decomposition

are generally agreed upon as the two most important

characteristics.

Botanical composition

It is the plant communities that will dictate the litter source for

the formation of the peat under them. This has led to first-

order classifications that differentiate peat into four

broad categories; moss, herbaeeous, wood and detrital or

hwnifiedpeat. Moss is often subdivided into Sphagnutn (i.e.,

Sphagnaceae—the peat mosses) and brown mosses (i.e.,

Amblystegiaceae) because both groups are common peat

formers. Sphagnum is the single most important moss genus.

Few other moss groups, except for members of the Poly-

trichaceae are important peat-formers, for example, in the

southern hemisphere (Clymo, 1983). Identification ofthe moss

remains to family and genus is often possible in the field with a

hand lens, and where preservation is good, it is possible to

identify to species level with the aid of a microscope (e.g.,

Janssens, 1983). The same is true for flower and seed parts,

leaves, stems and roots of sedge (i.e., Cyperaceae), grass (i.e.,

Poaceae) and rush (i.e., Juncaceae) remains, which are

probably, the most important groups comprising herbaceous

peats.

It is easy to differentiate, Carex, Eriophorum, Phrag-

mites, Cladium, Juncus peats, and in the case of the Andes in

South America, for example, Oxychloe peats (Earle et al.,

2003).

Woody peats are common in forested and shrub-dominated

peatiands. Wood, if there were trees or tall and dwarf shrubs,

is commonly encountered in peat. Much of it is identifiable

depending upon the state of preservation. Stumps, logs or

large branches can be sectioned and identified using standard

wood identification techniques. Seeds, nuts, samaras, strobili,

cones,

leaves, needles, buds and bud scales, and bark can also

be identified, almost certainly to family, often to genus and

even species.

The last major category refers to peat where the plant

remains are so disarticulated (i.e., detrital peat) or decomposed

(i.e.,

humified peat) that the bulk of the plant is no longer

recognizable and identifiable. Where macroscopic remains are

no longer recognizable, it is possible to use paleoecological

techniques such as pollen and spores analyzes to infer plant

origins of the peat. Other plant groups including lichens, such

as Siphula or Cladina communities in western Canada, and

algae may leave distinctive thin horizons in moss or herbac-

eous-rich peats, but not usually in accumulations of any

significance.

State of decomposition

This character, usually called the state of humifieation, is

partly assessed by the extent to which plant structure is visible,

and partly by color. Field assessment is usually made using the

H scale (Von Post and Granlund, 1926). The scale is a

subjective description by a numerical scale of 1-10 based on

the color of the water squeezed in the hand. Numerous other

more sophisticated techniques to assess density of color of

water or chemical extractants also exists (Tolonen and

Saarenmaa, 1979), but comparisons of techniques show

reasonable agreement, so the simplest H scale technique, is

the one most often used.

516

PETROPHYSICS OF SAND AND SANDSTONE

Other characteristics

Other important characteristics that can be measured to

further characterize peats are inorganic matter content,

inorganic solutes (i.e., calcium, potassium), cation exchange

capacity, microorganism activity, bulk density (dry matter

mass/volume), water content, gas content, water-retaining

capacity, proportion of fibre (i.e., as size elass), structure, heat

of combustion, color, and age (Clymo, 1983).

Occurrence and distribution of peatlands

Peatlands develop where geological stability and physiography

allow water to collect on the land surface long enough in a

growing season to support peat-forming plant commutiities. A

positive or balanced hydroperiod is, therefore, required in

order to maintain waterlogging and to sustain the peat-

forming plants and peatland.

Peatlands are cosmopolitan in distribution. About 95

percent of the worlds peatlands occur in North America, Asia

and Europe (Lappalainen, 1996). Canada has the largest area

of peatlands in the world with 1.1 x 10^km^ (Tarnocai etal.,

2000).

Most of the peat in the world lies in the Boreal and

Temperate Biomes of the northern hemisphere where geolo-

gical history, cool and moist climate and productive

plant communities have given rise to widespread peatland

formation. These are regions where water is especially

abundant, waterlogging is widespread, thus favoring peat-

forming plants and peatlands.

Barry G. Warner

Bibliography

Clymo, R.S., 1983. Peat. In Gore, A.J.P. (ed.). Mires: Swamp. Bog. Fen

and

Moor.

General

Studies. Elsevier Science, pp. 159-224.

Clymo, R.S., 1984. The limits to peat bog growth. Philosophical

Transactions

of the Royal Society of London, Series B, 303: 605-654.

Earle, L.R., Warner, B.G., and Aravena, R.,

2003.

Rapid development

of an unusual peat-accumulating ecosystem in the Chilean

Altiplano. Quaternary Research (In press).

Fuehsman, C.H., 1980. Peat: Industrial Chemistry and Technology.

Academic Press.

Gorham, E., 1953. Some early ideas concerning the nature, origin and

development of peat lands. Journalof Ecology, 41: 257-274.

Heathwaite, A.L., Gottlich, K., Burmeister, E.G., Kaule, G., and

Grospietsch, Th., 1993. Mires: definitions and form. In

A.L. Heathwaite (ed.). Mires: Process, Exploitation and Conserva-

tion.

J. Wiley and Sons, pp. 1-75.

Ingram, H.A.P., 1978. Soil layers in mires: function and terminology.

Journal of Soil Science, 29: 224-227.

Janssens, J.A., 1983. A quantitative method for stratigraphical analysis

of bryophytes in Holocene peat. Journal of Ecology, 71: 189-196.

Lappalainen, E., 1996. General review on world peatland and peat

resources. In Lappalainen, E. (ed.). Global Peat Resources.

Geological Survey of Finland, pp. 53-56.

Overbeck, F., 1975. Botanisch-Geologische Moorkunde. Neumunster:

Waehholtz.

Tarnocai, C, Kettles, I.M., and Lacelle, B., 2000. Peatlands of Canada.

Geological Survey of Canada, Open File Report 3834.

Tolonen, K., and Saarenmaa, L., 1979. The relationship of bulk

density to three different measures of the degree of peat

humifieation. Proceedings. International Symposium On Classifica-

tion of Peat and Peatlands. Hyytiala, Finland: International Peat

Society, pp. 227-238.

Vardy, S.R., and Warner, B.G., 2002. Holocene ecosystem variability

of polygon fens in central Nunavut, Canada. Canadian Journal of

Earth Sciences.

Von Bulow, K., 1929. Ailgemeine Moorgeologie. Berlin: Verlag von

Gebriider Borntraeger.

Von Post, L., and Granlund, E., 1926. Sodre Sveriges torvtillgangar I.

Sveriges

Geologische

Undersolgelse, C335:

1-127.

Cross-references

Humic Substances in Sediments

Kerogen

Maturation, Organic

PETROPHYSICS OF SAND AND SANDSTONE

Introduction

Porosity in sand is the only component that forms during the

sedimentation process. During most of its existence porosity

does not represent a simple void but the presence of a fluid or

gas.

Many of the physical properties of sand and sandstone

(hereafter referred to as "sandstone") are functions of the

details of the porous part of sandstone. Porosity differs from

other eonstituents of sandstone in that it forms a physieally

continuous three-dimensional web-like complex. The intimate

properties of this complex strongly affect such properties as

permeability (Ehrlich et al., 1991b) and fracture toughness

(Ferm etal., 1990).

Models for porous microstructure prior to

image analysis

For most of the 20th Century sandstone porosity was the

domain of physicists and engineers. They deduced structure

consistent with physical measurements, especially permeabil-

ity. Darcy's permeability carries with it no intrinsic informa-

tion concerning the microstructure. Darcy's Law relates flow

(caused by a differential between input and outlet pressure) in

a cylinder containing a porous medium to the geometry of the

cylinder. Taking the geometry into account, the rate of flow

through each cylinder is proportional to the difference between

input and output pressures. However the constant of

proportionality (commonly called the "permeability") varies

from sample to sample. Permeability thus involves the nature

of the porous medium. However an infinite number of

significantly different porous microstructures can yield the

same value of permeability. Permeability would reach a

maximum if the cylinder were simply an empty tube. Hence

one way to form a geometric model of the microstructure is to

assume a homogeneous (or "homogeneously heterogeneous")

medium where the micro flow paths are longer than the length

of the sample cylinder; that the flow "sees" a greater length

than the length of the sample cylinder. This added length was

postulated to be due to the tortuous flow paths through the

medium. Although the concept of "tortuosity" was very

effectively demolished by Scheidegger, (1974) on theoretical

grounds, and by Ehrlich etal. (1991b) on empirical (quanti-

tative petrographic) grounds, the concept of tortuosity is very

popular with probabilistic modelers (Dullien, 1979). As

discussed below, the permeability (holding grain size constant)

is due to the presence of hyper efficient flow paths along

packing flaws.

PETROPHYSICS OF SAND AND SANDSTONE

517

Pores and pore throats

The porosity complex consists of two major parts: pores and

pore throats (Berg, 1975; Dullien, 1979). Pores account for all

of the volume of porosity and tend to occupy the interstices

between grains thus providing a cuspate shape bearing concave

facets each representing the boundary between a pore and an

adjacent sand grain. Adjacent pores communicate at the cusps,

the cross sectional area of minimum volume of a plane cutting

through a cusp is termed a "pore throat" (Scheidegger, 1974).

Pore throats, then, are the bottlenecks that affect transmissiv-

ity of fluids, pressures, diffusion, and other transport proper-

ties.

Pore throats are important mediators of the rate of

diagenesis (Prince and Ehrlich, 2000) and are extremely

important in hydrocarbon reservoirs. Pores, on the other

hand, represent the capacity of the sandstone but are seldom

important in fluid transport.

Analysis of the porous microstructure

A functional description of sandstone porosity should produce

output that consistent with subjecdve porosity classification

but also quantitadve and precise in order to describe physical

properties that are continuous variables. This calls for the

application of digital data acquisition and an image processing

capability. Such capabilities only became commonly available

after 1975, so the preexisting subjective classification (inter-

granular pore, intra-granular pores and moldic pores) was

really most valuable in tracking diagenetic processes than

relating thin section data to physical response.

Imaging

Commonly sandstones are studied by imaging a planar section

via a light microscope, a scanning electron microscope or an

electron luminescenee apparatus. The plane of section interacts

with the three-dimensional sample by (given simple assump-

tions) such that the ratio of the total area of each constituent

to the others approximates the volume of the ratios of the

components.

Pore types and throat sizes

Information concerning the size and shape of grains or pores is

hazy in that the plane of section can penetrate a grain

anywhere between the "equator" and the "pole" such that a

wide size range of two-dimensional representatives represents

each grain size class. Pore throats are seldom encountered by

the plane of section as shown by the abundance of "isolated"

intergranular pores in most sandstones, (the pore throat lying

above or below the plane of section). Even when throats are

encountered, their true size is impossible for estimate from

section. Accordingly additional ways to observe sandstone

must be used to supplement two-dimensional images. These

include permeameters, mercury injection apparatus, and

measurement of electrical properties of saturated media (Etris

et al., 1989; Ehrlich et al., I991a,b). By building a model

consistent with all of these, we can deduce the values of the

critical parameters that control the porous complex.

Petrographic image analysis

"Petrographic Image Analysis" ("PIA") (Ehrlich etal., 1984,

1991a,b) is a generic term associated with the move from

subjective totally visual microscopic analysis to acquisition

and processing of digital imagery. Areas containing the entire

plane of section can be imaged and the collection of image may

form a seamless mosaic before the porous complex is analyzed.

Having stated that only throats direct influence on transport

properties, one might infer that analysis of pores in section

would be fruitless. For instance the relationship between

porosity and permeability is commonly very weak. However it

can be demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between

pore type and throat size (McCreesh etal., 1991b). For this to

occur and be relevant to transport properties, some types of

pores must form condnuous networks that are relatively

efficient with respect to transport. Quantitative determination

of pore types can only be aecomplished by deducing the three

dimensional sizes and shapes of pores from their two

dimensional seetions. We define the porosity objects exposed

in section

as

porels

(Porosity

Elements) (Ehrlich etal., 1991a). A

porel is defined as a patch of porosity that is internally

continuous with all of its parts. In a loose packed sand for

instance, the porosity may represent a lacelike filigree in

section and so the image might contain only two or three really

extensive porels. As porosity declines as a consequence of

diagenesis, porels systematically evolve into small isolated

patches of porosity when viewed in section. One form of PIA

involves the use of a variant of a common image analysis

algorithm termed "erosion/diladon differencing" (Ehrlich

elal., 1991a) that produces porosity size and shape spectra

that can be analyzed by a spectral unmixing algorithm,

Polytopic Vector Analysis, an offshoot of factor analysis,

(Johnson etal., 2001) into an objective classification of pore

types,

including their sizes, shape, and volumetric proportions.

This provides a link to earlier subjective pore type classifica-

tions as well as to physics. The output of this procedure can be

related to the physical measurements on order to construct a

plausible three-dimensional model of the porosity consistent

with all methods of measurement.

Mercury injection—determination of throat size

Mercury injection porosimetry is the prime physical test,

followed by permeability (Ehrlich etal., 1991b) and electrical

conducdvity / resistivity (Etris etal., 1989). Mercury injection

involves placing a sample (commonly a core plug about 2 cm in

diameter) into a sealed pressure vessel connected to a supply of

mercury. Mercury is a strongly nonwetting phase and will not

imbibe into the sample spontaneously. Pressure is progres-

sively increased until mercury is forced into the sample. At the

lowest pressure of injecdon only a fraction of the porosity is

invade. The relationship between injected volume and pressure

is recorded. The volume of porosity invaded in a pressure

increment represents the amount of porosity that can be

accessed by pore throats of a given size range through the

Laplace equation (Scheidegger, 1974; Dullien, 1979). Thus

mercury porosimetry earries strong throat size information

and poor pore type information, the inverse of imaging in that

regard. At a high enough pressure, almost all porosity is filled

except for isolated inclusions within grains. The injection data

can be precisely related to the pore type information obtained

by image analysis via multiple regression with care taken that

the imagery is taken from a section at the end of a sample

cylinder before injection. The results consistently show a

strong relationship between pore type and throat size

(McCreesh etal., 1991). For this to occur pores of like type

518

PETROPHYSICS OF SAND AND SANDSTONE

must be mutually connected into circuits characterized by a

common size range.

Relationship between microstrucure and physics

The results of this combination of image analysis and mercury

injection data are sufficient to successfully estimate perme-

ability and electrical properties such as conductivity of the

sample when saturated with fluids.

Microcircuits and packing flaws

The concept of hyper efficient microcircuits (those associated

with the largest throats) dominating transport was directly

verified by another image analytical procedure involving

analysis of the Fourier transform of the binary image

(porosity 1.0, matrix 0.0) (Prince etal., 1995). Filtering the

transform produces images where the circuits are prominently

displayed. The Fourier transform is exactly equivalent to an

X-ray diffraction pattern and so the numerical tools used in

the analysis are much the same. Both the optical transform

of sandstones and the X-ray transforms of crystals, share

common characteristics in tfiat in neither are the particle/

atoms perfectly arrayed. Instead packing flaws separate closely

packed domains. Graton and Fraser (1935) demonstrated via a

series of experiments with monolayers of equal size spheres the

nature of the flaws and their inevitability just about the same

dme as crystal chemists were using bead packs to illustrate

packing flaws in ionic crystals. Unfortunately the work of

Graton and Fraser has largely been ignored due to its prolixity

and length.

Origin of packing flaws: the Graton and Fraser model

According to Graton and Fraser (1935) the packing flaws are a

consequence of sedimentadon. A depositional episode com-

monly occurs as the sedimentation of a collection of suspended

grains that accumulate in a layer that is many grains thick

under the influence of gravity. Closest packing is the

arrangement of lowest potential energy and so nearby grains

tend to cluster in this fashion. Such clusters form sponta-

neously throughout the sedimenting mass but there is no

proeess that will force the clusters into a common orientadon.

As the accreting closely packed clusters grow, the eventually

interfere with one another producing bounding compromise

zone (packing flaws) characterized by large pores connected by

large throats—the permeability circuits. In theory and

observadon, once generated, packing flaws propagate without

limit, ending only when intersecting another set of flaws. This

provides the continuity that ensures agreement between two-

dimensional images and the volumetrically based physical

measurements such as mercury injection porosimetry.

Graton and Fraser (1935) also came up with the basis of a

natural history of packing flaws. As mentioned above, sand is

commonly deposited episodically producing a sand accumula-

tion consisting of a large number of sand on sand beds. The

trivial unconformities defined by bed boundaries represents a

sand water interface of reladvely long duration resuldng in a

sort of annealing (densification) of the sand exposed to the

moving water. The impulse of the next episode of sedimenta-

tion results in a major oriented mismatch between that

interface and the newly deposited sand. Thus packing flaws

are more densely spaced just above bedding planes. Outcrop

observation verifies that many outcrops "weep" from a small

interval (few cm thick) from the base of an overlying bed. As

discussed below, this effect is also observed in pardally oil-

saturated core, where the dark oil decorates the bases of beds

and may be absent in the middle and upper parts of a bed.

Multiphase flow

The porous microstructure is critically important in the case of

multiphase flow such as oil and water. In this case two

mutually immiscible fluids are competing for the pore space.

Commonly but not always water is a "wetting" phase and so

can spontaneously imbibe into the sandstone via capillary

forces (Berg, 1975). Oil is commonly a "nonwetting" phase

and must be forced into the sandstone by pressure just as

mercury (another extremely nonwetting phase) is forced into a

sandstone sample. Thus water will tend to segregate and be

held in parts of microporosity containing small throats and the

nonwetdng phase will initially be forced into the porous

circuits connected by the largest throats. The wetting phase

will also coat all mineral surfaces and so be somewhat of a thin

barrier between the oil and the pore walls. "Relative

permeability" tests measure the degree of mobility of either

phase as a function of saturation. Such are in agreement with

the microstructural model described above (Prince and

Ehrlich, 2000). The nonwetting phase is loosely held in pores

with large throats (packing flaws) and the wetting phase is

tightly held in pore complexes connected by small throats.

Presumably water completely fills the pores of sandstone

before migration of petroleum. The buoyant force of the oil

column provides the pressure needed for to displace this initial

water with oil. The longer the oil column, the greater the

pressure gradient from the oil water content to the seal (Berg,

1975).

Thus oil near the top of a reservoir displaces more water

than rock near the oil water contact. However changes in grain

size (which also affects throat sizes) as well as disordered zones

near bed boundaries will ensure various values of water

saturation for a given height above the oil water contact.

Summary and conclusions

The petrography of sandstones and other porous media can

best be determined by a combination of image analysis and

physical measurement. The two dimensional information

taken from plane of thin section can be turned into a three

dimensional microstructural complex by convolving that data

with physical properdes that arise from the three dimensional

volume. The common availability of high quality relatively

inexpensive digital image capability along with a wealth of

image processing algorithms allow such analysis to be under-

taken at almost any level. The nuances gained have shown

their worth in the petroleum industry and also as a way to

quantify the nature and extent of diagenesis. This field is still

very young and many opportunities exist for new findings. A

caveat is that the practitioner must have intermediate-level

competence in muldvariate analysis.

Robert Ehrlich

Bibliography

Berg, R.R., 1975. Capillary pressures in stratigraphic traps. American

As.sociation

of Petroleum

Geologists

Bulletin, 59

(6):

939-956.

PHOSPHORITES

519

Dullien, F.A.L., 1979. Porous Media: Fhdd Transport and

Pore

Struc-

ture, 2nd edn, Academie Press.

Ehrlieh, R., Crabtree, S.J., Kennedy, S.K., and Cannon, R.L., 1984.

Petrographic image analysis I—analysis of reservoir pore com-

plexes. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 54 (4): 1365-1376.

Ehrlich, R., Horkowitz, K.O., Horkowitz, J.P., and Crabtree, S.J.,

1991a. Petrography and reservoir physies 1: objective elassification

of reservoir porosity. American Association of Petroleum Geologists

Bulletin, 75 (10): 1547-1562.

Ehrlich, R., Etris, E.L., Brumfield, D., and Yuan, L.P., 1991b.

Petrography and reservoir physies III: physical models for

permeability and formation factor. American Association of

Petro-

leum Geologists Bulletin, 75 (10): 1579-1592.

Etris,

E.L., Brumfield, D.S., and Egrlich, R., 1989. Petrographic

insights into the relevance of Archie's Equation: formation factor

without "M" and "A". SPWLA Journal Thirtieth Annual Logging

Symposium, June, 1989, I (F): pp. 1-18.

Ferm, J.B., Ehrlich, R., Kranz, R.L., and Park, W.C., 1990. The

relationship between petrographie image analysis data and fracture

toughness. Association of Engineering Geologists Bulletin, 27 (3):

327-339.

Graton, L.C., and Fraser, H.J., 1935. Systematic packing of spheres

with particular relation to porosity and permeability. Journal of

Geology, 43: 785-909.

Johnson, G.W., Ehrlich, R., and Full, W., 2001. Prineipal component

and receptor models. In Murphy, and Morrison (eds.). Introduc-

tion to Environmental

Eorensics.

Academic Press, Chapter 12 pp

46i-51fi.

MeCreesh, C.A., Ehrlich, R., and Crabtree, S.J., 1991. Petrography

and reservoir physics II: relating thin section porosity to capillary

pressure: the association between pore types and throat size.

American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 75 (10)-

1563-1578.

Prince, C.R., Ehrlich, R., and Anguy, Y., 1995. Analysis of spatial

order in sandstones II: grain clusters, packing flaws, and the small-

scale structure of sandstones. Journal of Sedimentary Research,

A65:

13-2^8.

Prince, CM., and Ehriich, R., 2000. A test of hypotheses regarding

quartz cementation in sandstones: a quantitative image analysis

approach. In Worden, R. (ed.). Quartz Cementation in Sandstones,

IAS Special Publication, 29.

Seheidegger, A.E., 1974. The Physics of FlowThrough

Porous

Media, 3rd

edn. University of Toronto Press, 353pp.

Cross-references

Fabric, Porosity, and Permeability

Sands, Gravels and their Lithifled Equivalents

PHOSPHORITES

Introduction

Phosphorites are rocks enriched in phosphorus relative to

average erustal abundances, an enhancement usually expressed

in terms of P2O5 concentrations. Whereas the average P2O5

content of condnental crustal rocks is esdmated as 0.23

percent (Ronov and Yaroshevsky, 1969) and sedimentary

rocks average 0.03-0.16 percent (McKelvey, 1973), rocks

typically designated as phosphorites have 15-37 percent P2O5

(Bentor, 1980). Phosphorites thus have phosphate contents

that are 60 to 160 times greater than the crustal average and

on the order of 100 to over 1,000 times greater than the

averages for common sedimentary rocks. The most conten-

tious issues concerning phosphorites center on the mechanism

or mechanisms by which this enrichment has taken place in

the geologic past and whether formation of phosphorites

represents a significant perturbation of the biogeochemical

cycle for phosphorus, questions discussed below.

The element phosphorus averages about 70 ppb

(~ 2.3 umol/L) in seawater, is a limiting nutrient to biological

productivity on geological dmescales, and regulates the global

carbon cycle and climate. Because of its low abundance and

because it is closely tied to short-lived biological-chemical

cycles of growth and decay, phosphorus has a relatively brief

residence time in the ocean, estimated for the surface ocean by

Mackenzie etal. (1993) as 0.07 years based on phytoplankton

uptake. The overall oceanic residence time for phosphorus is

estimated to range between ca. 10,000 years and 40,000 years

(Delaney, 1998; Colman and Holland, 2000; Guidry et al.,

2000).

Initial interest in phosphorites stemmed from their impor-

tance as a raw material for the production of fertilizer

phosphate. Along with potassium and nitrogen, phosphorus

is critical for plant growth; but, whereas K and N are readily

available from several sources (seawater, evaporite deposits,

the atmosphere), phosphorus can only be obtained in large

quantities from phosphorite deposits. Following the discovery

in the mid-19th Century of the role of mineral nutrition in

plant metabolism by the German chemist Justus von Liebig,

phosphorite deposits began to be exploited after more readily

available P sources such as guano, manure, and crushed bones

became inadequate to support expanding agricultural systems.

Phosphorites are now the main source of fertilizer P, and

mining of phosphorites is a world-wide enterprise, with major

eenters of production in the USA, Morocco, and several

countries in the Middle East. Excluding China, global

production in 2000 was close to 92,200 thousand metric tons

(IFA, 2001).

The main mineral in phosphorites is carbonate fluorapatite

(CFA) or francolite, which according to Slansky (1986) has the

simplified general formula Caio[(P04)6_x(C03)JF2+x, with

numerous substitutions of both cations and anions (Nathan,

1984;

Jarvis etal., 1994). The most important ancient deposits

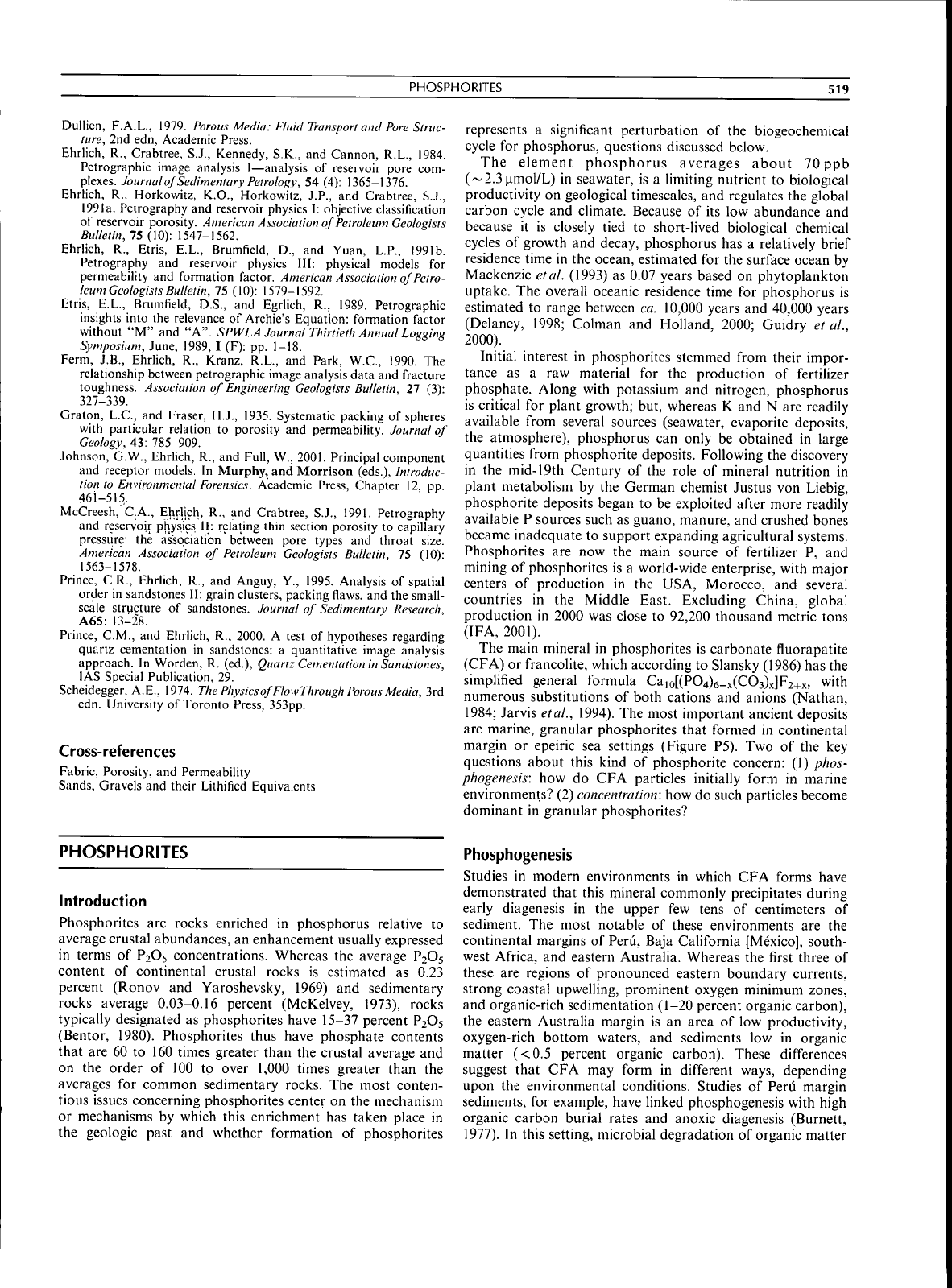

are marine, granular phosphorites that formed in continental

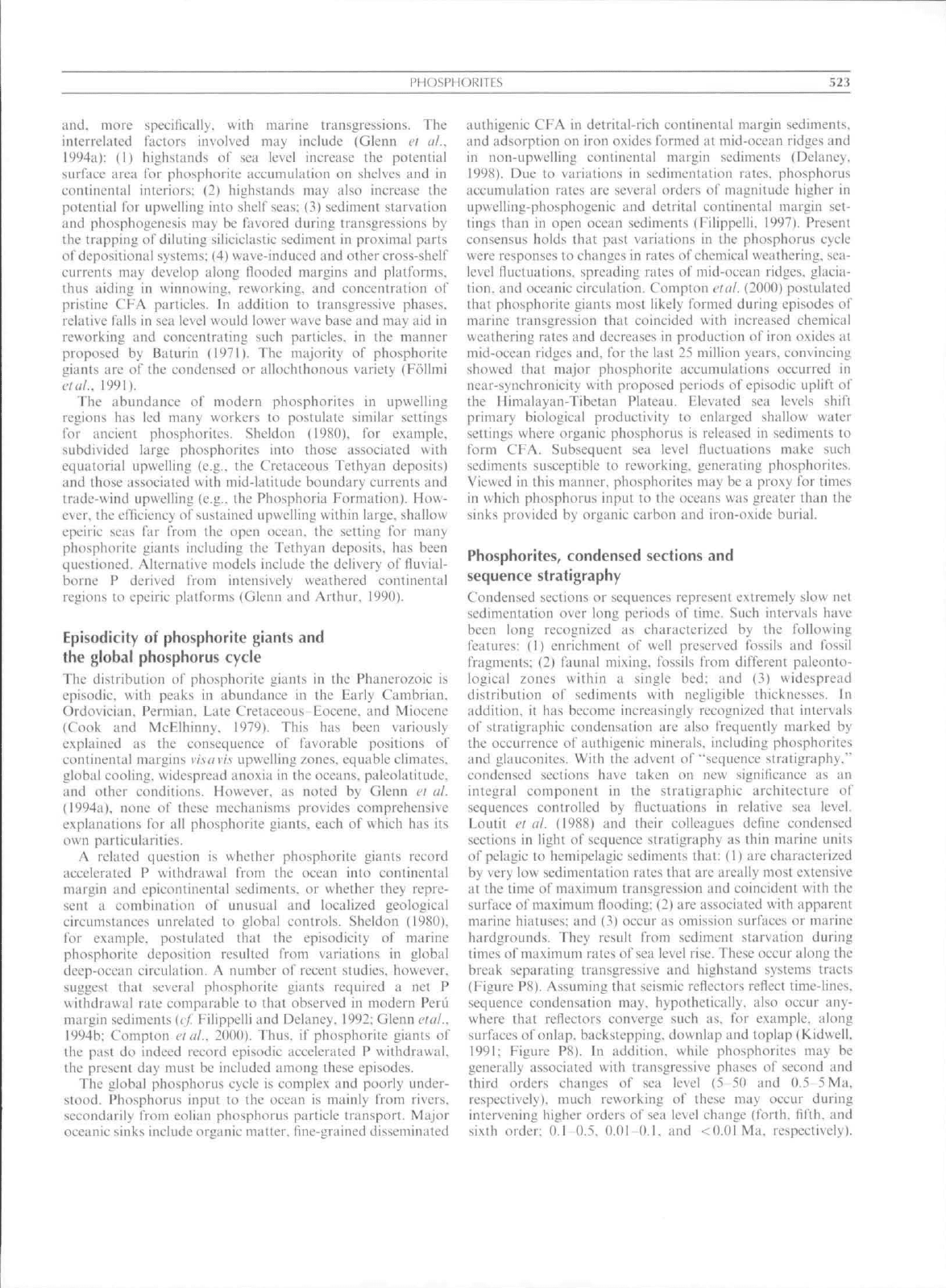

margin or epeiric sea settings (Figure P5). Two of the key

questions about this kind of phosphorite concern: (1) phos-

phogenesis: how do CFA particles initially form in marine

environments? (2) concentration: how do such particles become

dominant in granular phosphorites?

Phosphogenesis

Studies in modern environments in which CFA forms have

demonstrated that this rnineral commonly precipitates during

early diagenesis in the upper few tens of centimeters of

sediment. The most notable of these environments are the

continental margins of Peru, Baja California [Mexico], south-

west Africa, and eastern Australia. Whereas the first three of

these are regions of pronounced eastern boundary currents,

strong coastal upwelling, prominent oxygen minimum zones,

and organic-rich sedimentation (1-20 percent organic carbon),

the eastern Australia margin is an area of low productivity,

oxygen-rich bottom waters, and sediments low in organic

matter (<0.5 percent organic carbon). These differences

suggest that CFA may form in different ways, depending

upon the environmental conditions. Studies of Peru margin

sediments, for example, have linked phosphogenesis with high

organic carbon burial rates and anoxie diagenesis (Burnett,

1977).

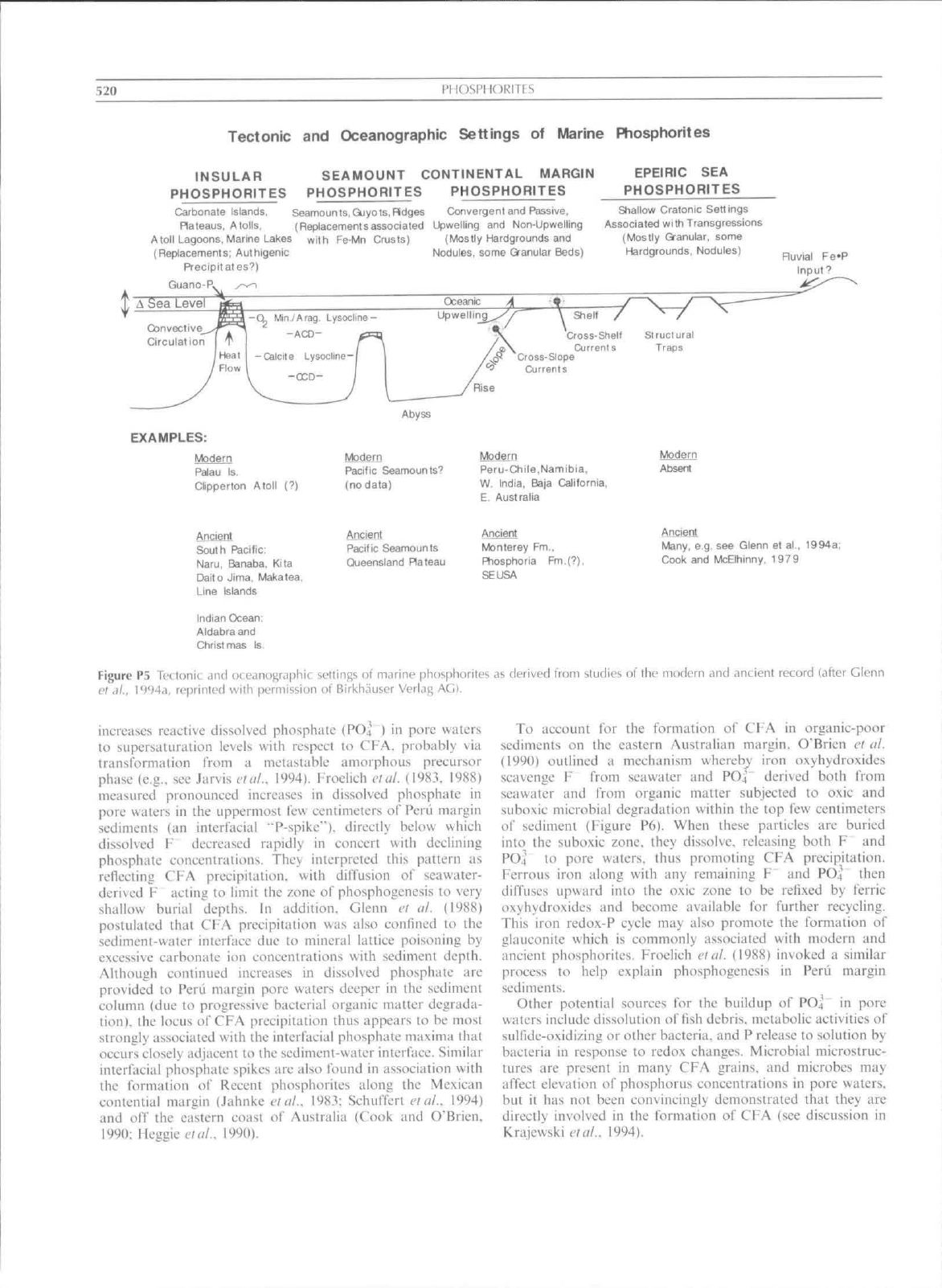

In this setting, microbial degradation of organic matter

520

PHOSPHORITES

Tectonic

and

Oceanographic Settings

of

Marine Phosphorites

INSULAR

PHOSPHORITES

SEAMOUNT CONTINENTAL MARGIN

PHOSPHORITES PHOSPHORITES

Carbonate Islands, Seamounts.Qjyots,Pldges Convergent and Passive,

Rateaus, Atolls, (Replacementsassociated Upwelling

and

Non-Upwelling

Atoll Lagoons, Marine Lakes with Fe-Mn Crusts) (Mostly Hardgrounds

and

(Repiacemenls; Authigenic Nodules, some Granular Beds)

Precipitates?)

Guano-P.

EPEIRIC

SEA

PHOSPHORITES

Shallow Cratonic Settings

Associated with Transgressions

(Mostly Granular, some

Hardgrounds, Nodules)

Ruvial

Fe-P

Input?

Oceanic

-CL Min./Arag, Lysocline-

-ACD-

Upwelling Shell

Cross-Shelf

Currents

Cross-Slope

Currents

Structural

Traps

Rise

Abyss

EXAMPLES:

Modern

Palau

Is.

Oipperton Atoll

(?)

Ancieni

South Pacific:

Naru,

Banaba, Kita

Daito Jima, Makatea,

Line Islands

Indian Ocean:

Aldabraand

yofilern

Pacific Seamounts''

(no data)

Ancient

Pacific Seamounts

Queensland Plateau

Modern

Peru-Chile,Namibia,

W, India, Baja California,

E Australia

Ancient

Monterey

Fm.,

Ftiosphoria Fm.(?),

SEUSA

Modern

Absent

Ancient

Many, e.g. see Glenn

et

al., 1994a

Cook

and

McElhinny,

1979

Figure P5 Teclonit: .^ncl occLinographic settings

of

marine phosphorites as derived frnm studies

of ihc

modern .ind ancient record (after Cienn

et«)/.,

1994a. reprinted with permission

ot

Birl<h<iuser Veriag AGl.

increases reactive dissoived phosphiite (PO4

) in

pore waters

to supersaturation levels with respect

to CFA.

probably

via

transformation from

a

metastable amorphous precursor

phase (e.g..

see

Jarvis

elaf.

1994). FrocHch elaf (19S3.

1988)

measured pronounced increases

in

dissolved phosphate

in

pore waters

in the

uppermost

few

centimeters

of

Perii margin

sediments

(an

interfacial '"P-spike*"), directly below which

dissolved

F

decreased rapidly

in

concert with declining

phosphate eoticentrations. They interpreted this pattern

as

reflecting

CFA

precipilation. with diffusion

of

seawater-

derived

F

acting

to

limit

the /one of

phosphogenesis

to

very

shallow burial depths.

In

addition, Glenn

et af

(1988)

postulated that

CFA

precipitation

was

also confined

to the

sediment-water interface

due to

mineral lattice poisoning

by

excessive carbonate

ion

concentrations with sediment depth.

Although continued increases

in

dissolved phosphate

are

provided

to

Perii margin pore waters deeper

in the

seditnent

column

(due to

progressive bacterial organic matter degrada-

tion),

the

locus

of

CFA precipitation thus appears

to be

mosl

strongly associated with the interfaeial phosphate maxima that

occurs closely adjacent

to

the seditnent-watcr interlace. Similar

interfaeial phosphate spikes

arc

also found

in

association with

the formation

of

Recent phosphorites along

the

Mexican

contential margin (Jahnke

etaf.

1983; Schuffert

elaf. 1994)

and

olT the

eastern coast

of

Australia (Cook

and

O'Brien,

1990:

HeggiciVi//,. 1990).

To account

for the

fortnation

of CFA in

organic-poor

sediments

on the

eastern Australian margin. O'Brien

et af

(1990) outlined

a

mechanism whereby iron oxyhydroxides

seavenge

F

from seawater

and PO4

derived both from

seawaler

and

from organie matter subjected

to

oxic

and

suboxic microbiai degradation within

the top few

centimeters

of sediment (Figure

P6).

When these particles

are

buried

into

the

suboxic zone, they dissolve, releasing both

F and

PO4

to

pore waters, thus promoting

CFA

precipitation.

Ferrous iron along with

any

retnaining

F and POJ

Ihen

diffuses upward into

the

oxic zone

to be

refixed

by

ferric

oxyhydroxides

and

become available

for

further recycling.

This iron redox-P cycle tnay also promote

the

formation

of

glauconite which

is

commonly associated with modern

and

ancient phosphorites. Froeiich etaf (1988) invoked

a

similar

process

to

help explain phosphogenesis

in

Perii margin

sediments.

Other potential sources

for the

buildup

of

PO.;"

in

pore

waters include dissolution offish debris, metabolic activities

of

suifidc-oxidizing

or

other bacteria,

and P

release

to

solution

by

bacteria

in

response

to

redox ehanges. Microbiai microstruc-

Uires

are

present

in

many

CFA

grains,

and

tnicrobcs

may

affect elevation

of

phosphorus concentrations

in

pore waters,

but

it has not

been convincingly demonstrated that they

are

directly involved

in the

formation

of

CFA

(see

discussion

in

Krajcwski

etaf.

1994),

PHC;)SPHORITFS

521

Seawater

SOI-

-*•

HS

Sediment

Oxic

Suboxic

Anoxic

Figure Pfa St hfm.itu nt

(.

\-A

prctifjiLiliun in surlit iai marine sediments

illuslrjiing phtisphorus derived trom either the Fe-redox cycle or

directly from the microbial breakdown ot Organic matter. Light stippled

areas represent solid phases, bLick arrows are solid-phase fluxes.

White-outlined black arrows indicate reactions, white arrows are

diffusion pathways. Phosphorus for CFA precipitation may be derived

from either or both of direct microbial decomposition of organic matter

iCorgl or from a redox-coupled iron oxyhy(froxide-|jh()sphorus

pumping mechanism Irighl side (if illustrationi. During burial and

mixing,

microbial cJecomposition of organic matter utilises a sequence

of electron acceptors in order of decreasing thermodynamic advantage.

Oxygen is used first, followed by nitrate (and nitrite}, manganese- and

iron-oxyhydroxides and sulfate, in thai order (Froelich t'! JL,

H79I.

Degradation of organic matter liberates PO.,' (o solution, and

dissolution of TeOOH liberates Fe"^ ' , PO4 , and F" causing elevated

concentr-itions of these ions in porewaters. If sufficient levels are

attained,

POi reacts with Ca' ', Mg-' ' , SOjf and F ions diffusing

into the sediment from seawater, and COj derived from the oxidation

of organic matter, lo precipitate a precursor phosphate mineral which

subsequently recrystalli^es to CFA (francolite; see text). Fxcess PO.i

may also diffuse upward toward the sediment-water interface where it

is resorbed by ferric iron oxyhydroxides. iron m.iy diffuse both

downward to be fixed as glaueonite

(e.g.,

C^lenn, 19901 under suboxic

conditions, or as FeS under anoxic conditions, and upwards to the oxic

layer where it is reprecipilated as FeOOH. In this later case, ihe Fe-

redox cycle provides an effective means of trapping POJ" in the

sediment and promotes precipitation of CFA. especially in more

org.mic-lean sediments ici. O'Brien et dl.. 1990).Mo{Jifiefl after Jarvis

ef

.1/.,

1994, reprinted with permission of Birkhausec Verlag.

Types of phosphate particles and

concentration processes

The precipitation o\' CFA may produce a variety of particle

types,

including peioids. coated grains, laminae, and small

nodules dispersed in muds. In this type of seditnent. termed

"pristine"' phosphate by I-ollmi elal. (1991), the primary

phosphate particles appear to be

In

situ, with no reworking by

niechaiiical or biological processes. For the most part,

howe\cr, these dispersed forms h:i\e whole rock P^O^

concLMitraiions well below those of economic phosphorites.

Baturin (1971) accounted for this disparity by proposing a

tnodel of sea level "highstand" phosphogenesis altcrnuting

with "lowstand" reworking by eurrents to produee winnowed

phosphorite layers in Quaternary deposits from ihc continental

shelf of southwest Africa.

Marine phosphorites in the stratigraphic record commonly

have two attributes: (I) they are grain-supported, granular

concent rat i Otis of silt-, sand-, and pcbblc-size phosphatie

grains; and (2) they occur as stratified sediment bodies that

display evidence for tratisport atid redeposition by bottom

currents. The most common grains are structureless peioids.

which are probahly mostly authigenic rather than phospha-

tized biogenic fecal pellets. Other grain types may include

concentrieally coated grains, phosphatie intraclasts and

tiodules, primary phosphatie bioelasts (inarticulate brachio-

pods.

vertebrate boties, teeth, fish scales), atid phosphatized

carbonate skeletal grains. The richest phosphorites have CFA

cements, but granular phosphorites may also be cemented by

carbonate or silica tninerals.

Sotne stratified phosphorites have traction current struc-

tures such as cross-bedding (Glenn and Arthur. 1990). others

have characteristic of turbidites and indicate deposition from

gravity flows (Gritnm and Follmi. 1994), siiil others appear to

be tempestite beds (Trappe. 1992). Many phosphorites occur in

condensed intervals that eontain evidence for multiple episodes

of primary phosphogenesis. shallow burial, exhumation, and

hydraulic reworking (FoHmi. 1989, 1990: Glenn and Arthur.

1990).

Phosphatie hardgrounds are cotntnon in such con-

densed sections. Depositional and biological amalgamation

may lead to the formation of thick (tneter scale) phosphorite

beds,

and it appears that post-depositional burrowing may

commonly destroy current induced structures in many massive

phosphorite beds.

The characteristics above lead most workers to accept

Baturin's (1971) notion of a two-stage tnechani.sm (i.e.,

primary phosphogenesis followed by reworking) for the

formation of targe, granular phosphorite deposits. However,

nontransported phosphorites such as hardgrounds are asso-

ciated with some granular phosphorites, and only in a lew

cases are the primary phosphatie tnudrocks, the supposed

parental sediment for the redeposited phosphatie grains,

clearly identifiable in the aeeompanying seditnent layers.

Moreover, the dotninant types of Proterozoic phosphorites

are primary phosphorite tnudrocks and strotnatolitic phos-

phorites which were clearly not transported (see papers in

Cook and Shergold, 19f:i6a)"

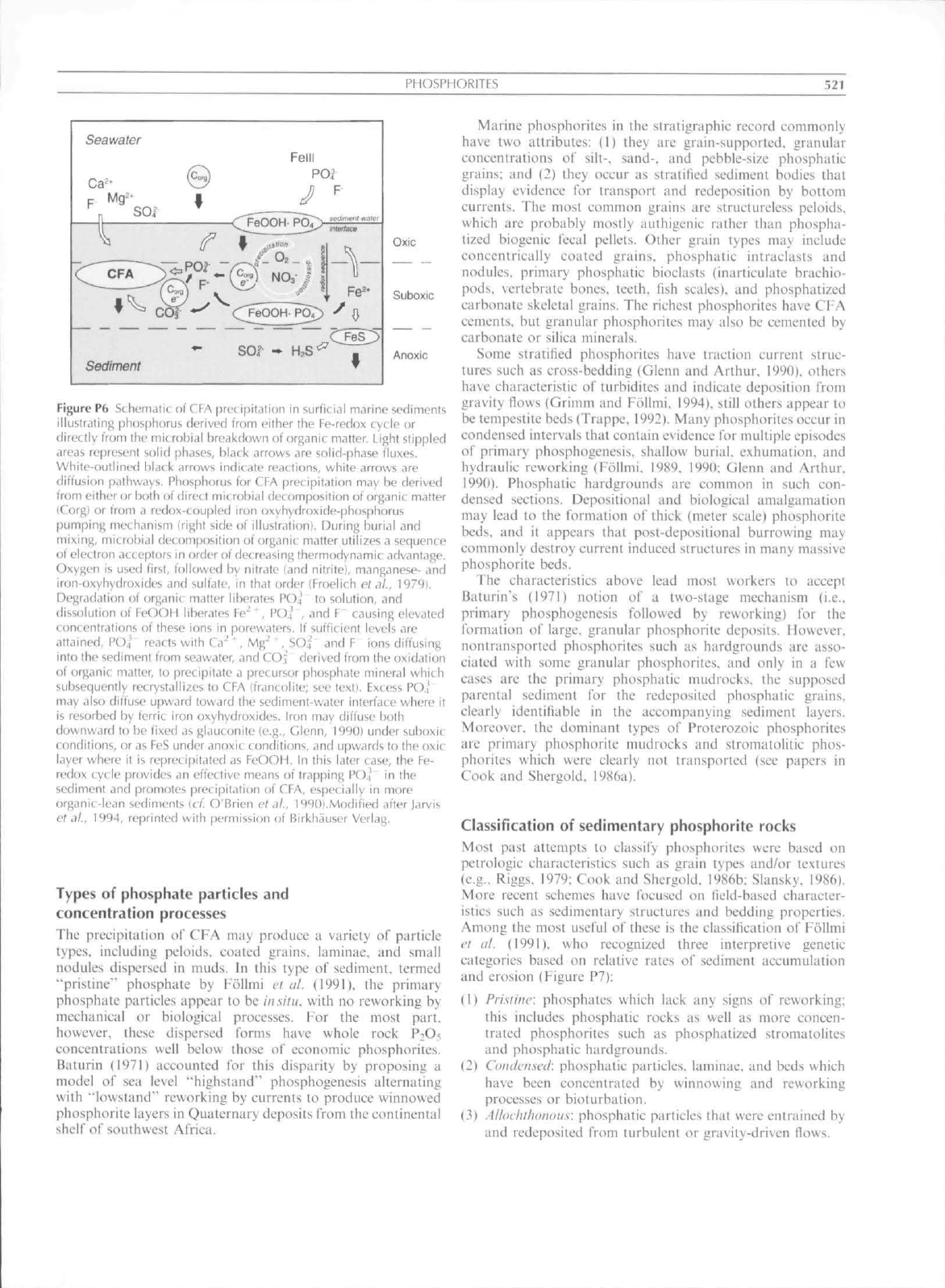

Classification of sedimentary phosphorite rocks

Most past attempts to classify phosphorites were based on

petrologic characteristies sueh as grain types and/or textures

(e.g.. Riggs. 1979: Cook and Shergold. 1986b: Slansky. 1986).

More recent schemes have focused on field-based character-

istics such as sedimentary structures and bedding properties.

Among the most useful of these is the classifieation of Follmi

L'l

al. (1991). who recognized three interpretive genetic

categories based on relative rates of seditnent accumulation

and erosion (Figure P7):

1I) Prislinc: phosphates which lack any signs of reworking;

this includes phosphatie rocks as well as more concen-

trated phosphorites sueh as phosphati/ed stromatolites

and phosphalic hardgrounds.

(2) Coiulciiscd: phosphaiic particles, laminae, and beds which

have been concentrated by winnowing and reworking

processes or bioturbation.

(3)

.4Uochtlumou.s:

phosphatie particles that were entrained by

and redeposited from turbulent or gravity-driven flows.

522

PHOSPMORITFS

Stratification

Stratification in phosphatie sediments

as a function of time and energy

Phospjipgenesis

Insitu phosphatiediaciasts

Accumulation rates > Erosion rates

"PRISTINE"

c

D

In situ phosphatie lamina

Accumulation rales - Erosion rates

"CONDENSED''

Figure P7 Genetic classification o! stratification types (from Follmi ct

Springer Verlag.

Accumulation rales < Erosion rates

"ALLQCHTHONOUS"

.. 1991 and Glenn et ,il.. l<)94di. Reprinted with the permission of

Hybrids oi" these categories are common. One example is

that pristine phosphatie grains may experience redeposition

followed by multiple episodes of burial, renewed phosphogen-

esis and phosphatie cetnentation. and subsequent erosional

exhumation, resulting in a complex and laterally variable

phosphorite condensed bed.

The formation of "phosphorite giants"

Very large phosph{iriLes deposits (typically with reserves

greater than 10'* metric tons of P:>Oi) have been termed

"phosphorite giants'" by Glenn and Arthur (1990) and account

Ibr a substantial proportion of world phosphate production.

Examples include the Cretaceous-Eoeene Tcthyan deposits

and the Permian Phosphoria Formation oi" western North

America.

Kazakov (1937) made one of the first attetiipts to explain

such deposits by invoking upweliing and inorganic precipita-

tion o\' apatile from seawater in coastal regions, an idea

subsequently modified to include the role of organie degrada-

tion in shallowly buried sediments, as outlined above. Most

phosphorite giants were deposited beneath relatively shallow

waters of marginal seas and epeiric platfortns (Figure P5), and

most seem to correlate in a general way with elevated sea levels

PHOSPHORITES

and. more specifically, with marine transgressions. The

interrelated faetors involved may include (Glenn el al..

1994a): (1) highstands of sea level increase the potential

surface area f"or phosphorite accumulation on shelves and in

eontinental interiors: (2) highstands may also increase the

potential for upwelling inlo shelf seas: (3) seditnent starvation

and phosphogenesis may be i"avored during transgressions by

the trapping of diluting silieiclastie sediment in proxitnal parts

ofdepositional systems; (4) wave-indueed and other cross-shelf

currents may develop along flooded margins and platfortns,

thus aiding in winnowing, reworking, and concentration of

pristine CFA partieles. In addition to transgressive phases,

relative i"alls in sea level would lower wave base and may aid in

reworking and concentrating sueh particles, in the manner

proposed by Baturin (1971). The majority of phosphorite

uiaiits are o\' the condensed or allochthonous variety (Follmi

claf,

1991).

The abundanee of modern phosphorites in upwelling

regions has led many workers to postulate similar settings

for ancient phosphorites. Sheldon (1980), for example,

subdivided large phosphorites into those associated with

equatorial upwelling (e.g.. the Cretaceous Tethyan deposits)

and those associated with mid-latitude boundary currents and

trade-wind upwelling (e.g.. the Phosphoria Forniation). How-

e\er, the efficiency ol"sustained upwelling within large, shallow

epeiric seas far frotn the open ocean, the setting for many

phosphorite giants including the Tethyan deposits, has been

questioned. Alternative models include the delivery of fluvial-

borne P derived from intensively weathered eontinental

regions to epeiric platforms (Glenn and Arthur. 1990).

Episodicity of phosphorite giants and

the glohal phosphorus cycle

The distribution o\' phosphorite giants in the Phanerozoic is

episodic, with peaks in abundance in the Early Cambrian.

Ordovician. Pennian, Eate Cretaceous Eocene, and Miocene

(Cook and MeElhinny, 1979), This has been variously

explained as the consequence of favorable positions of

continental margins

yi.\(ivi.\

upwelling /ones, equable climates,

global cooling, widespread atioxia in the oceans, paleolatitude.

and other conditions. However, as noted by Glenn ct al.

(i994a). none oi' these mechanisms provides eomprehensive

explanations for all phosphorite giants, eaeh of whieh has its

own particularities.

A related question is whether phosphorite giants reeord

accelerated P withdrawal from the oeean into eontinental

tnargin and epicontinental sediments, or whether they repre-

sent a combination of unusual and localized geological

circutnstances unrelated to global controls. Sheldon (1980).

for example, postulated that the episodicify of marine

phosphorite deposition resulted from variations in global

deep-ocean circulation. A lumiber of recent studies, however,

suggest that several phosphorite giants required a net P

withdrawal rate eotnparable to that observed in modern Peril

margin sediments (t;/.' Filippelli and Delaney, 1992: Glenn elal.,

1994b: Cotnplon cial.. 2000). Thus, if phosphorite giants of

the past do indeed record episodic accelerated P withdrawal,

the present day must be included among these episodes.

The global phosphorus eycle is eomplex and poorly under-

stood. Phosphorus input to the ocean is mainly from rivers.

secondarily from eolian phosphorus particle transport. Major

oceanic sinks include organic matter, (ine-crained disseminated

authigenic CFA in deti"ital-rich continental margin sediments,

and adsorption on iron oxides formed at mid-ocean ridges and

in non-upwelling continental margin sediments (Delaney.

1998).

Due to variations in sedimentation rates, phosphorus

accumulation rates are several orders of magnitude higher in

upwelling-phosphogenic and detrital continental margin set-

tings than in open ocean sediments (Filippelli, 1997). Present

consensus holds that past variations in the phosphorus cycle

were responses to ehanges in rates of chemical weathering, sea-

level fluetuations. spreading rates of mid-ocean ridges, glacia-

tion. and oceanie circulation. Compton elal. (2000) postulated

that phosphorite giants mosf likely formed during episodes of

marine transgression that coincided with increased chemical

weathering rates and decreases in production of iron oxides at

mid-ocean ridges and. for the last 25 million years, convincing

showed that major phosphorite accumulations occurred in

near-synehronicity uith proposed periods of episodic uplift of

the Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau. Elevated sea levels shii"t

primary biological productivity to enlarged shallow water

settings where organic phosphorus is released in sediments to

form CFA. Subsequent sea level fluetuations make such

sediments susceptible to reworking, generating phosphorites.

Viewed in this manner, phosphorites may be a proxy for times

in which phosphorus input to the oceans was greater than the

sinks provided by organic carbon and iron-oxide burial.

Phosphorites, condensed sections and

sequence stratigraphy

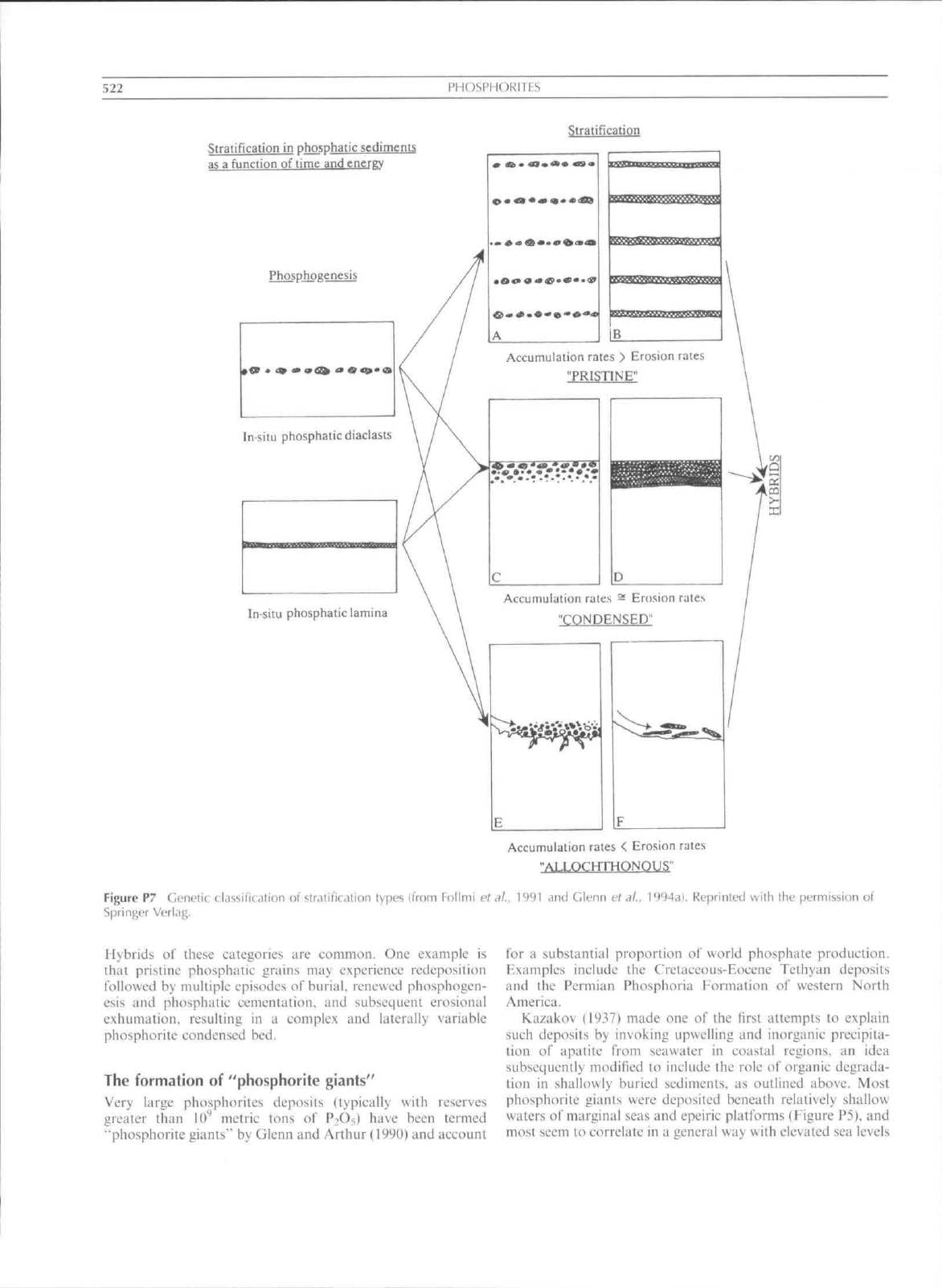

Condensed sections or sequences represent extremely slow net

seditnentation over long periods of time. Sueh intervals have

been long recognized as characterized by the f"ollowing

features: (1) enrichment o!" well preserved fossils and fossil

fragments; (2) I'aiuial mixing, fossils from different paleonto-

logieal zones within a single bed: and (3) widespread

distribution of sediments with negligible thieknesses. In

addition, it has beeome increasingly recognized that intervals

of stratigraphie condensation are also frequently marked by

the oeeurretice of authigenie minerals, including phosphorites

and glauconites. With the advent of "sequence stratigraphy.'"

condensed seelions have taken on neu significance as an

integral component in the stratigraphie architecture ol'

sequences controlled by fluctuations in relative sea level.

Loutit elal. (1988) and their colleagues define condensed

sections in light of sequence stratigraphy as thin marine units

of pelagic to hemipelagic seditnents thai: (I) are characterized

by very low seditnentation rates that are areally most extensive

at the titne of maximum transgression and coincident with the

surface of maximum flooding; (2) are associated with apparent

marine hiatuses; and (3) oeeur as omission surfaces or marine

hardgrounds. They result from sediment star\'ation during

times of maximum rales of sea level rise. These occur along the

break separating transgressive and highstand systems tracts

(Figure P8). Assuming that seistnic reflectors reflect time-lines,

sequence eondensalion may. hypothetically. also occur any-

where that reflectors converge such as. for example, along

surfaces of onlap. baekstepping, downlap and toplap (Kidwell.

1991:

Figure P8). In addition, while phosphorites may be

generally associated with transgressive phases ol' second and

third orders changes of sea level (5 50 and 0.5 5 Ma,

respectively), tnueh reworking of these may occur during

intervening higher orders of sea level change (forth, fifth, and

sixth orde7: (i^l 0.5. O.Oi-O.i. and <0.01Ma. respectively).

524 PHOSPHORITFS

However,

its

noted above, tiiost major episodes

of

phosphorite

genesis

do

appear

to be

related

lo

U'ansgressive phases,

although

the

occurrence

of

reworked deposits wilhin

the

upper portions

of

highsland systems tracts

may

also rellect

episodes

of

condensation

and

bypassing that occur

in

association with

the

convergence

of

loplapping seisrnic

reflectors (Figure

P8), In sum, the

actual distribution

of

condensed deposits within seismic sequences

is

probably more

complex than depicted

by

recent models.

Olher types of phosphorite deposits

In addition

to

phosphorites formed

in

continental margin

or

epeiric

sea

environments (Figure

P5).

lesser qttantities

of

phosphorites occur

in

three other settings:

(1) Island or insular

ptw.sphoriles

are

commonly composed

of

guano

and the

replacement products

of

reactions between

bird droppings

and the

underlying host rock;

the

latter

is

commonly

a

carbonate,

and

these types

of

phosphorites

are important economic resources

on

Qtiaternary carbo-

nate islands

in the

Pacilic

and

Indian Oceans,

The

largest

deposits

of

this kind occur

on the

island ol" Nauru

in the

western equatorial Pacific (Piper etal.. 1990),

As

noted

by

Glenn

et at.

(1994a),

not all

island phosphorites

are

associated with guano,

and

some

may

have precipitated

in insular marine lakes

or

other settings.

(2) Seamouni

and

Gttyot

pho.sphoriie.s

and

phosphatized lime-

stones, many associated with iron-manganese encrusta-

tions,

are

common

on

elevated portions

of

the seafloor

in

all

the

world's oeeans. Although

a few are

submerged

insular deposits, most appear

to be of

marine origin

and

formed

in

areas

of

slow seditnenlation

and a

pronounced

oxygen minimutn zone, Burnett etal. (1987) suggested they

formed preferentially

at low

latitudes, possibly

in

equator-

ial upwelling regions

of

high productivity. They linked

the

assoeiation

of

iron-manganese crusts

to the

enhanced

concentration

of

phosphate

and

metals wilhin

an

oxygen

minitrtutn zone that bathes

the

upper parts

of

seamounts,

(3) Igneous rock.s such

as

carbonatites

and

other alkaline

igneous intrusive complexes which

are

enriched

in

fluor-

apatite. Caiii(PO4)f,F2 (Slansky. 1986). Itnportant. econom-

ic deposits

of

this kind occur

in

northern Russia, Brazil.

and eastern

and

southern Africa (Cook. 1984).

Environmental issues connected

to

phosphorites

Along with rises

in

world populations

and

living standards,

exploitation

of

phosphorites

as a

source

of

fertilizers will

inevitably also increase. This

may be

accompanied

by

several

(A) POTENTtAL CONDENSED

PHOSPHORITE

:^:'-••;,V.V,'.- Prograding siliciclastics, bioclasts.

and reworked authigenic minerats

SEQUENCE

BOUNDARY

Highsland

Systems Tract

SEQUENCE

BOUNDARY DOWNLAP

Retrograde

and

downtapped

in-situ authigenic minerats,

"flood bioclasts",

and

detrital quartz

DOWNLAP SURFACE

(B)

SB

HST

MFS

TST

SB^S

APPARENT TRUNCATION

(=

BACKLAP)

Transgressive Systems Tract

^ Highstand Authigenic Grams

Reworked Seaward

Transgressive Authigenic Grains

In Situ

or

Locally Reworked

Figure

P8

Potential relationships between sequence slratigrdphy, c:ondensed sections

and

phosphorites.

(A)

Possible positions

of

sequence

condensation within

an

ide.ilized depositional sequence (stipples), (after Kidwell, 19'M).

(Bl

Schemalic illustration

of the

pUicenienI

of non-

reworked prisline duthigenit phosphorite {and/or glauconitel

and

reworked phosphorite (and/or glautonilei. Pristine phosphates

may

form within

transgressive syslems tracts

and at the

maximum flooding surface, whereas later phases

are

reworked seaward within highstand systems tracts,

IC) The timing

of

systems tracts development with respect

to one

cycle

of

sea level change,

LST

iowstand systems tract,

TST

transgressive systems

tract,

HST

highstand systems

tracl,

TS

transgressive surface,

MFS

maximum flooding surface,

SB

sequence boundary. Dots

on the

sea level curve

represent locations

of

maximum phosphorite emplacement, {After Glenn

ef

<?/„ 1994a, reprinted with p<-rmission

of

Birkhauser Verlag

AG},