Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

h'LANAR AND PARALLEL LAMINATION

535

U.';^;:---^.*Vfss:^->;&ft^SMiia'^

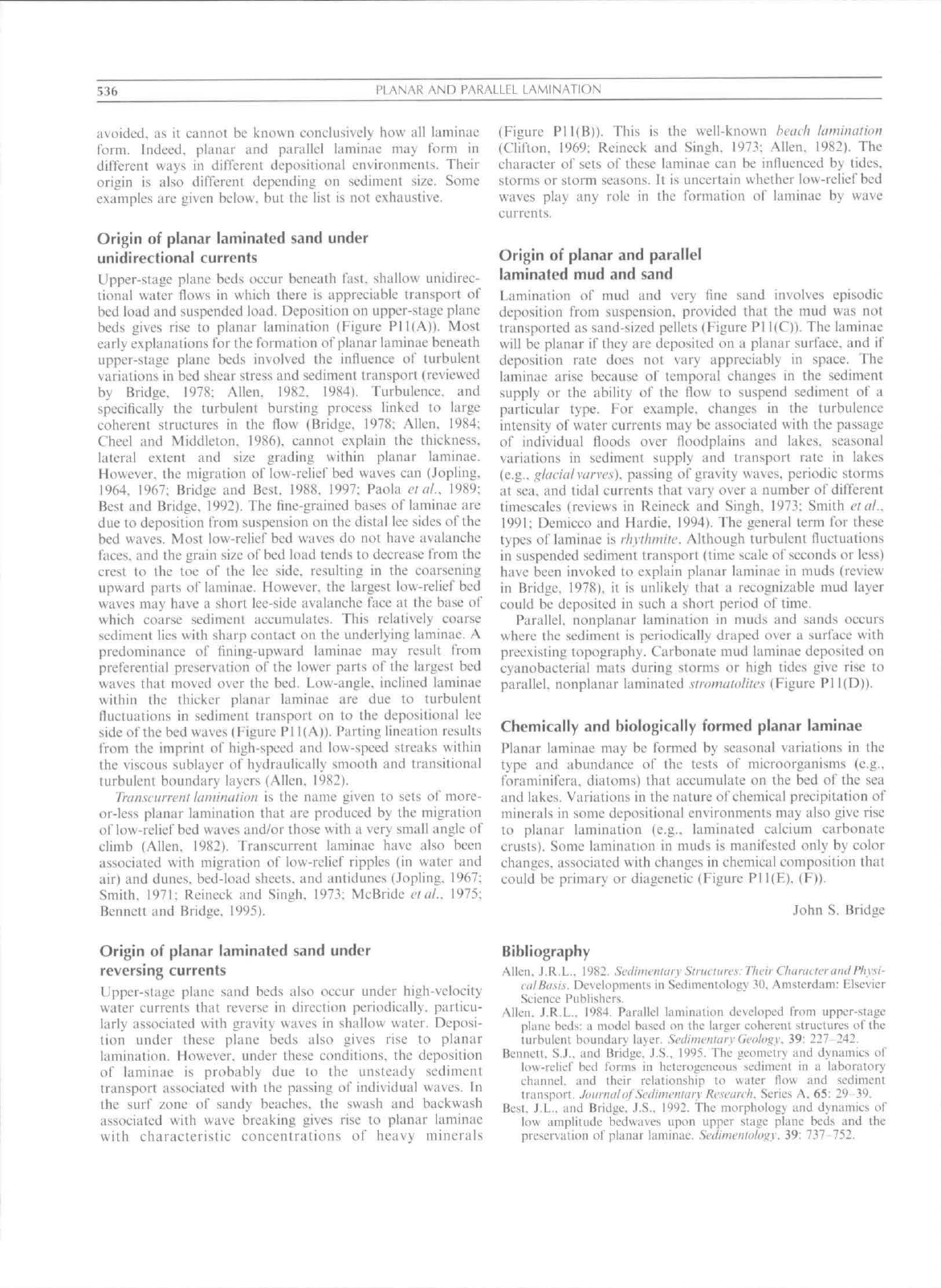

Figure Pll (A) Planar laminae thought to have formed on an upper slage plane bed. Permo-Triassic St Bees Sandstone, UK, Ltiw-angle laminae

labeled c. Sh.irp Iwses to relatively Ihitk laminae labeled d. Discontinuous (Iruncatedl laminae labeled e ilrom Besl and Bridge, 1992).

i.Hi Modern beach laminae from Virginia, tJSA, IC) Planar laminae composed of very line grainstone (lighl) and mudstone idarki. Middle

Ordovician St.

P,iul

Group, Maryland, USA (photo courtesy

ol"

Robert Demiccol, (Di Wavy and crinkled

p.ir,illel

laminae istroma(olite) composed

of firainstone idarki and dolomilic limeslone (light), Upper Cambrian Conococheague Limestone, Maryland, USA (photo courtesy of Robert

Demicco), (E) Planar, parallel laminae in dolomitlc mudstone. Lower Proterozoit Wittenoom Dolomite, Western Ausiralia Iphoto courtesy of

Robert Demicto), (F) Parallel laminated calcium carbonaie crusts on Pleistocene limestone, Florida Keys, USA (pholo tourtesy of Robert

Demicco),

boundaries, referred to as primary

citrrenl liticctlion

or

lineation. The ridges are a tew grains high and have a spacing

of about

1

cm.

Laminae commonly occur in sets

(Uiiuina.sci.s)

that are

recognizable because of changes in texture, composition, or

orientation of laminae (Figure PI I). Sets of planar and parallel

laminae normally have bounding surfaces that are morc-or-less

parallel to the laminae within them. If the anyte between the

laminae and the laminasct boundary exceeds a few degrees, the

sedimentary structure is referred to as cniss laminalion or

inclined

lamitiarion.

However, some sets of planar lamination

do contain low-angle inclined laminae in plaees.

The term lamina has been used to denote a thin sediment

layer produced by momentary fluctuations in current velocity

and sediment transport rate (Otto. 193S, and many others).

Such genetic implications for the term lamina should be

536

PLANAR AND PARALLEL LAMINATION

avoided,

as it cannot be known eonckisively how all laminae

fonn.

Indeed, planar and parallel laminae may form in

different ways in dilTerent depositiona! environments. Their

origin is also different depending on sediment size. Some

examples are given beiow, but the list is not exhaustive.

Origin of planar laminated sand under

unidirectional currents

Upper-stage plane beds occur beneath fast, shallow unidirec-

tional water flows in which there is appreciable transport of

bed load and suspended

load.

Deposition on upper-stage plane

beds gi\es rise to planar lamination (ligure Pll(A)). Most

early explanations for the formation of planar laminae beneath

upper-stage plane beds involved the influence of turbulent

variations in bed shear stress and sediment transport (reviewed

by Bridge. 1978: Allen, 1982. 1984). Turbulence, and

specifically the turbulent bursting process linked to large

coherent structures in the flow (Bridge. I97,S: Allen. 1984:

Cheel and Middleton. 1986). cannot explain the thickness,

lateral extent and size grading within planar laminae.

However, the migration of low-relief bed waves can (Jopling,

1964.

1967; Bridge and Best. 1988. 1997; Paola

elal..

1989;

Best and Bridge, 1992). The tine-grained bases of laminae are

due to deposition from suspension on the distal lee sides ofthe

bed waves. Most low-relief bed waves do not have avalanche

faces,

and the grain size of

bed

load tends to decrease from the

erest to the toe of the lee side, resulting in the coarsening

upward parts of laminae. However, the largest low-relief bed

waves may have a short lee-side avalanche face at the base of

which coarse sediment accumulates. This relatively eoarse

sediment lies with sharp contact on the underlying laminae. A

predominance of fining-upward laminae may result from

preferential preservation of the lower parts of the largest bed

waves that moved over the bed. Low-angle, inclined laminae

within the thicker planar laminae are due to turbulent

fluctuations in sediment transport on to the depositional Ice

side ofthe bed waves (Figure PI I(A)). Parting lineation results

from the imprint of high-speed and low-speed streaks within

the viscous sublayer of hydraulically smooth and transitional

turbulent boundary layers (Allen, 1982).

Transcurrt'nl lamination

is the name given to sets of more-

or-less planar lamination that are produced by the migration

of low-relief

bed

waves and/or those with a very small angle of

climb (Allen. 1982). Transeurrent laminae have also been

associated with migration oi" low-relief ripples (in water and

air) and dunes, bed-load sheets, and antidunes (.lopling. 1967;

Smith,

1971; Relneck and Singh, 1973; McBride

ciaf.

1975;

Bennett and Bridge, 1995).

(Fitzure Pll(B)), This is the well-known

becicli

laminalion

(Cntton,

1969; Reineck and Singh, 1973; Allen. 1982), The

character of sets of these laminae can be influenced by tides,

storms or storm seasons. It is uncertain whether low-relief bed

waves play any role in the formation of laminae by wave

currents.

Origin of planar and parallel

laminated mud and sand

Lamination of mud and very fine sand involves episodic

deposition from suspension, provided that the mud was not

transported as sand-sized pellets (Figure PI 1(C)). The laminae

will be planar if they are deposited on a planar surfaee, and if

deposition rate does not vary appreciably in space. The

laminae arise because of temporal ehanges in the sediment

supply or the ability of the flow to suspend sediment of a

particular type, I-or example, changes in the turbulence

intensity of water currents may be associated with the passage

of individual floods over floodplains and lakes, seasonal

variations in sediment supply and transport rate in lakes

(e.g.,

glacial

varves).

passing of gravity waves, periodic storms

at sea. and tidal currents that vary over a number of different

titneseales (reviews in Reineek and Singh, 1973; Smith

elal.,

1991;

Demicco and Hardie. 1994). The general term for these

types of laminae is rhyiltmiie. Although turbuleni fluctuations

in suspended sediment transport (time scale of seeonds or less)

have been Invoked to explain planar laminae in muds (review

in Bridge. 1978). it is unlikely that a recogni/able mud layer

could be deposited in such a short period of time.

Parallel,

nonplanar lamination in muds and sands occurs

where the sediment is periodieally draped over a surface with

preexisting topography. Carbonate mud laminae deposited on

cyanobacterial mats during storms or high tides give rise to

parallel,

nonplanar laminated

.stromalatitcs

(Figure PI 1(D)).

Chemically and biologrcally formed planar laminae

Planar laminae may be formed by seasonal variations in the

type and abundance of the tests of microorganisms

(e.g..

foraminifera, diatoms) that accumulate on the bed of the sea

and lakes. Variations in the nature of

ehemical

precipitation of

minerals in some depositional environments may also give rise

to planar lamination

(c.g,.

laminated calcium carbonate

crusts). Some lamination in muds is manifested only by color

changes, associated with changes in chemical composition that

could be primary or diagenetic (Figure PI 1(E), (F)).

John S. Bridge

Origin of planar laminated sand under

reversing currents

LJppcr-stage plane sand beds also occur under high-velocity

water currents that reverse in direction periodically, particu-

larly associated with gravity waves in shallow water. Deposi-

tion under these plane beds also gives rise to planar

lamination.

However, under these eonditions, the deposition

of laminae is probably due to the unsteady sediment

transport associated with the passing of individual waves. In

the surf zone of sandy beaches, the swash and backwash

associated with wave breaking gives rise to planar laminae

with characteristic concentrations of heavy minerals

Bibliography

Allen.

J,R,L,. 1982,

SeJinienttiry

Striicturi.'.'i:

Their

Character and

Physi-

cal

Basis.

Developments in Sedimentology 30. Amsterdam: Elsevier

Science Publishers,

Allen.

J.R.L,. 1984, Parallel l;tmin:ition developed from upper-stage

pkme beds; a modi:l based on the larger coheretu slruetures of the

turbulent boundary layer,

SeitinieniaryGeoloi^y.

39: 227-242,

Bennett, S,J,, and Bridge.

.I.S..

1995, The geometry and dynamics of

low-relief bed forms in heterogeneous sediment in a laboratory

channel,

and their relationship lo water flow and sediment

transport,

J<nirnal(if.Sedinicnlary

Re.\eareh.

Series A, 65: 29 39,

Best,

J.l.,.

and Bridge, LS,.. 1992, Tlie morphology and dynamics of

low ampliliidc bedvvaves upon upper stage plane beds and the

preservation of planar laminae,

.Scdimenlolo)>y.

39: 737 752,

POREWATERS IN SEDIMENTS

537

Bridge, J.S,, 1978. Origin of horizontal lamination under turbulent

boundary layers. Sedimentary Geology, 20: 1-16.

Bridge, J.S,, and Best, J.L,, 1988. Flow, sediment transport and

bedform dynamics over the transition from upper-stage plane beds:

implications for the formation of planar laminae. Sedimentology,

35:

753-763.

Bridge, J.S,, and Best, J,L,, 1997, Preservation of planar laminae

arising from low-relief bed waves migrating over aggrading plane

beds:

comparison of experimental data with theory. Sedimentology,

44:

253-262.

Cheel, R.J., and Middleton, G.V., 1986. Horizontal lamination formed

under upper flow regime plane bed conditions. Journal of Geology,

94:

489-504.

Clifton, H.E., 1969. Beach lamination: nature and origin. Marine

Geology, 7: 553-559.

Demicco, R.V,, and Hardie, L.A., 1994, Sedimentary Structures and

Earty Diagenetic Features of Shallow Marine Carhonate Deposits.

SEPM Atlas Series No.I, 265pp.

Jopling, A.V., 1964. Interpreting the concept ofthe sedimentation unit.

Journalof Sedimentary Petrology, 34: 165—172.

Jopling, A.V., 1967, Origin of laminae deposited by the movement of

ripples along a streambed: a laboratory study. Journal of Geology,

75:

287-305.

McBride, E.F,, Shepherd, R.G,, and Crawley, R.A., 1975. Origin of

parallel near-horizontal laminae by migration of bed forms in a

small flume. Journal of Seditnentary Petrology, 45: 132-139.

McKee, E.D., and Weir, G.W., 1953. Terminology for stratification

and cross-stratification in sedimentary rocks. Bulletin ofthe Geolo-

gical Soeiety of America. 64: 381-390.

Otto,

G.H,, 1938, The sedimentation unit and its use in field sampling.

Journal of Geology, 46: 569-582.

Paola, C, Wiele, S.M., and Reinhart, M.A., 1989. Upper-regime

parallel lamination as the result of turbulent sediment transport

and low-amplitude bedforms. Sedimentotogy, 36: 47-60.

Reineck, H.E., and Singh, I.B., 1973. Depositional Sedimentary Envir-

onments. Springer.

Smith, D.G., Reinson, G.E., Zaitlin, B.A,, and Rahmani, R.A. (eds.),

1991,

ClasticTidalSeditnentology. Canadian Society of Petroleum

Geologists Memoir, 16: pp. 29-39.

Smith, N.D., 1971. Pseudo-planar stratification produced by very

low amplitude sand waves. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 41:

624-634.

Cross-references

Bedding and Internal Structures

Bedset and Laminaset

Biogenic Sedimentary Structures

Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures

Parting Lineations and Current Crescents

Stromatolites

Surface Forms

Swash and Backwash, Swash Marks

Tidal Flats

Tides and Tidal Rhythmites

Varves

POREWATERS IN SEDIMENTS

Approximately 20 percent by volume of the sedimentary

portion of the earth's crust consists of water that occupies

most of the matrix and fracture porosity of sediments and

sedimentary rocks. These porewaters are variously called

groundwater in freshwater aquifer systems, interstitial

water

in

marine sediments, and formationwater or basinal brines in deep

sedimentary basins, Porewaters as a group range widely in

chemical and isotopic composition and in their physical

properties. There has been considerable interest in the origin

and migration of porewaters because of the role these fluids

play in the geological, geochemical, and economic resource

evolution of sediments and sedimentary basins. The presence

of porewaters under pressure facilitates or may even induce

tectonic deformation of sedimentary basins and continental

margins, Porewaters serve as transport agents for heat and

reactive solutes in sediments, and variations in the composition

of porewaters in space and time yield important information

on mechanisms and rates of solute transport and diagenetic

reaction. The study of porewaters thus complements the study

of diagenesis obtained by the sedimentological, mineralogical,

and geochemical study of the solid phases present in a

sediment.

Historical development and outline

The origin of waters in the earth's crust has been speculated

upon since ancient times (Hanor, 1988), Prior to the 1600s,

there was a general belief that fresh groundwaters were formed

by the subsurface distillation of seawater which had infiltrated

deep into the earth. These freshwaters get discharged at the

surface to form rivers and streams, Seawater salt was left

behind in the form of subsurface brines. Beginning with the

publication of Perrault's mass balance studies in 1674, it was

eventually recognized that rivers, streams, and fresh ground-

waters are meteoric in origin. Debate on the origin of

subsurface brines in sediments, however, has continued up

until the present time. With the advent of modern geochemical

techniques in the last half of the past century, much has been

learned about the chemical and isotopic composition of

porewaters in sediments and their origin. Chief sources of

information have been the analysis of produced waters from

oil and gas fields, the analysis of potable groundwaters, and

the extensive body of analyzes of waters in deep sea sediments

generated as part of the JOIDES and ODP drilling projects.

This article reviews the types of solutes found in sedimen-

tary porewaters and the general types of processes which

control or influence porewater compositions. This background

information is then applied to three major types of sedimen-

tary pore waters: (1) shallow continental waters; (2) marine

interstitial waters in continental shelf and deep sea sediments;

and (3) waters in deep sedimentary basins. The focus is

primarily on the geochemistry of porefluids, but it should be

recognized that many important physical properties of pore-

waters and bulk sediments, such as density, viscosity, thermal

and electrical conductivity, and sonic transit time, are directly

dependent on fiuid temperature, pressure, and chemical

composition.

General composition of porewaters

Concentration units

A wide variety of units have been used to describe the

concentration of solutes in sedimentary porewaters. Concen-

trations are typically expressed in terms of mass, moles, or

equivalents of solute per liter of solution, kilogram of solution,

or kilogram of H2O, Many groundwater analyzes are

presented in mg/L or g/L, units which are convenient because

of the volumetric methods used in most analytical techniques.

Many in the marine geochemistry community, however, use

538

POREWATERS IN SEDIMENTS

mass or moles per kg of solution, which are pressure and

temperature independent concentration units. The concentra-

tion unit molality, mol/kg H2O, is used in thermodynamic

calculations of saturation state. One final unit is the equivalent

(eq),

where the number of equivalents of a solute is equal to the

number of moles of solute times absolute charge of the solute.

The units eq/L or meq/L are widely used in making charge

balance calculations from water analyzes and in defining

hydrochemieal facies, as described below.

Salinity and major solutes

The polar nature of the H2O molecule makes water an

excellent solvent for charged ions and other polar molecules.

The salinity or total dissolved solute (TDS) concentrations of

porewaters varies greatly, even within individual sedimentary

units.

Salinities of a few hundred mg/L or less are typical of

sediments fiushed by meteoric waters. The average salinity of

seawater is approximately 35,000 mg/L, and the porewaters in

many marine sediments have similar salinities. The salinities of

waters in the deeper parts of sedimentary basins, however, can

reach levels of 350,000 mg/L or more.

Although a wide range of dissolved species exist in natural

waters, the greatest proportion of TDS is contributed by a

relatively few species, typically Na+, K+, Mg^+, Ca^+, Cl",

HCOs", and SO4 , Several factors determine the major solute

concentration of a porewater. These include relative abun-

dance of the potential solute, the ease of accommodating the

solute into liquid water, and reaction rates and solubility

constraints imposed by coexisting mineral phases and reactive

mineral and organic surfaces. Cation accommodation in water

is determined in part by ionic potential, the ratio of cation

charge to ionic radius in Angstroms, Cations of small ionic

potential, roughly 3 or less, are readily accommodated in

aqueous solution as hydrated cations. These include most of

the group IA and IIA cations, including Li"*", Na"*", and K"*",

and Mg^+, Ca^+, Sr^+, and Ba^*, Small, highly charged

cations having an ionic radius of 12 or greater form soluble

charged anionic complexes with oxygen. Common examples

include the anionic complexes ofthe oxidized forms of C, N, P,

and S, which include HCO3" and CO3", NO3", PO4" , and

SO4",

Cations of intermediate ionic potential, however, are

accommodated in aqueous solution with much greater

difficulty. These include the abundant rock-forming cations

Al''"'",

Fe^"*", and Mn'*"'", which tend to react with water to form

insoluble hydroxides or to remain bound in silicate or oxide

mineral lattices. Silica forms the sparingly soluble complex,

silicic acid, H4SiO4, Valence state plays a key role in the

relative solubility and mobility of a cation. The reduced forms

of iron and manganese, Fe^"*" and Mn^""", are far more soluble

than the oxidized forms Fe^^ and Mn''"'", Halogen elements

form soluble, hydrated anions: F~, CP, Br~, I~,

Minor inorganic species

Sedimentary porewaters as a group contain measurable

concentrations of virtually every naturally occurring element

in the periodic chart. Some elements, such as Pb, Zn, and Cu,

sometimes occur in sufficient concentration to make the

porewater in question, generally a basinal brine of high

salinity, a potential ore-forming fluid. Others, such as Br, are

useful in tracing the origin of high salinity in porewaters. Some

minor and trace elements, such as Ba, Ra, and As, pose

potential health problems when they are present in drinking-

water supplies.

Gases and dissolved organics

Most gases and nonpolar organic molecules are only sparingly

soluble in aqueous solution, but their presence can be of

importance in driving diagenetic reactions and in deducing the

origin of porewater. The microbial consumption of dissolved

oxygen and production of dissolved CO2 are two important

subsurface reactions which influence the dissolved gas compo-

sition of natural porewaters (Chapelle, 1993), Groundwaters

derived from rainwater typically contain atmospherically

derived noble gases, whose concentration can be used to

estimate the temperature of the water at the time of recharge.

Waters in the deeper parts of sedimentary basins can contain

primordial helium, '^He, thought to be derived from the mantle

or deep crust. Very shallow groundwaters typically contain

minor concentrations of fulvic and humic acids derived from

the breakdown of organic matter (Drever, 1997), and basinal

waters often contain a variety of low molecular weight organic

compounds produced by the thermal maturation of organic

matter,

pH and redox state

The pH is defined as minus the log of the activity of the

hydrogen ion, —log a(H''') and is routinely determined on

porewater samples as a measure of acid-base conditions. The

pH of natural porewaters varies from over 9 for some shallow

groundwaters to less than 4 for some subsurface brines.

Several conventions are in use to describe the redox state of

natural waters: Eh, or electrode potential; pe, minus the log of

the activity of the electron; and foe, the fugacity of oxygen.

Sediments and fiuids in close proximity to the atmosphere or

to oxygenated seawater are typically oxidized because of the

availability of dissolved O2, In organic-rich sediments, how-

ever, conditions generally become progressively reducing with

depth or distance from recharge area,

Isotopic composition

Several major isotopic systems have been utilized to deduce the

origin of solutes and of H2O in different types of porewater.

Hydrogen-oxygen systematics have been used to distinguish

between H2O derived from meteoric precipitation and H2O left

behind in residual brines during the evaporation of seawater

(Hanor, 1988), Chlorine and t isotopic systematics have been

used to help constrain the apparent age of groundwaters.

Carbon and Sr, and more recently Li and B, isotopic

systematics have been used to deduce the sources of these

solutes and type and extent of diagenetic reaction between

fluids and mineral phases.

Graphical representation of porewater compositions

and hydrochemieal facies

The composition of shallow fresh groundwaters varies

considerably in terms of the relative proportion of major

cations and anions, more so than either marine-derived

interstitial waters or waters in deep sedimentary basins. It

has been a challenge to develop simple graphic approaches

to portray the spatial and temporal variations in typical

POREWATERS IN SEDIMENTS

539

groundwater composition (Domenieo and Schwartz, 1990), A

useful convention is the concept of hydrochemieal facies

(Back, 1961), where the composition of porewater is described

in terms of those few cations and anions which contribute the

bulk of the ionic charge in equivalents (eq/L) or milliequiva-

lents (meq/L), A Ca-HC03 porewater, for example, is one

dominated in terms of equivalents of charge by Ca^^ and

HCO3",

although lesser amounts of many other solutes may be

present. Prefixes such a F", B", S", and HS", representing

i"resh, brackish, saline, and hypersaline, may be added so that

some qualitative information on TDS is conveyed as well.

General physical and chemical controls on the

composition of porewaters

The general types of chemical reactions and physical processes

which control porewater compositions are general to each of

the three end-member types of pore waters discussed here. The

physical processes include advection, which is the bulk

transport of solutes through the pore spaces of a sediment

by the fluid flow, and fluid mixing which occurs as a result of

molecular diffusion and hydrodynamic dispersion around

mineral grains, Advection can be induced by sediment

compaction, by differences in topographic elevation, by

differences in fluid density, and by fluid pressures in excess

of hydrostatic (Domenieo and Schwartz, 1990),

The types of chemical reactions which influence porewater

composition include; hydrolysis or dissolution-precipitation

reactions involving porewater and bulk mineral phases, many

of which involve hydrogen ion and are thus acid-base

reactions; redox reactions in which there is a transfer of

electrons, usually between C, N, Fe, Mn, and S-bearing solutes

and solids; and mineral and organic surface reactions involving

adsorption and ion exchange. Many reactions involving

porewaters and ambient mineral phases occur nearly simulta-

neously. For example, the production of

H"*"

by the oxidation

of a sulfide mineral may induce the hydrolysis or dissolution of

a silicate mineral. Some of the cations released in the process

may be adsorbed onto the surface of newly formed clay

minerals produced by the destruction of the silicate precursor.

The combined effects of advection, dispersion, and chemical

reaction on the changes in spatial and temporal concentration

of a solute with time (dC/7d/) along a one-dimensional flow

path can be described by the following mass balance equation:

1-1)

where / is time,

v

is advective fluid velocity,

(/>

is porosity, and .v

is distance, O, is the coefficient of hydrodynamic dispersion for

solute /, and Rij is the net source-sink term for solute / for

chemical reaction y (Liehtner

e;a/,,

1996),

The first term on the right accounts for the net increase or

decrease in C, as the result of the advection or bulk flow of

fluid of varying C, through the sediment. The second term

describes the mass balance resulting from mixing due to

molecular or Fickian diffusion and dispersion. The final term

is the net sum of the rate of the chemical reactions involving

other phases and solute /, Variants on this mass balance

equation in one, two, and three dimensions are at the heart of

mathematical computations designed to couple the physical

and chemical processes which control porewater compositions.

These calculations are also used to quantify the mass transfer

which occurs between mineral and fiuid phases during

diagenesis. In one-dimensional systems, it is sometimes

possible to solve the equation analytically (Berner, 1980), but

in complex heterogeneous systems numerical techniques are

required (Liehtner etal., 1996),

Continental groundwaters

Topographically-driven meteoric groundwater systems

The sources of porewaters found in shallow freshwater

aquifers and interbedded aquicludes are meteoric precipitation

and recharge by lakes and streams during high surface water

levels.

That portion of rain or snow melt which does not form

runoff infiltrates downward into the unsaturated zone, where it

may be returned to the atmosphere via evapotransporation

and/or migrate further downward to recharge an underlying

aquifer. The groundwater within an aquifer will then typically

migrate both downward and laterally along preferred flow

paths and eventually discharge into either another continental

surface environment, such as a spring, lake, or stream, or into

the offshore submarine environment. Most meteoric ground-

water flow is driven by differences in topographic elevation

between areas of recharge and discharge (Domenieo and

Schwartz, 1990),

Rainwater typically contains several mg/L or more of

dissolved salts, Diagenetic alteration of meteoric water

compositions, however, occurs immediately within the soil

environment (Drever, 1997), The carbonic acid and organic

acids produced by soil bacteria are important weathering

agents, and the consequent dissolution of carbonate and

silicate minerals results in the leaching of the more soluble

cations, such as Na"*",

K."*",

Mg^"*", and Ca^""^, from the soil.

Although there is some complexing of Al and Fe by organics,

the less soluble cations, such as AP"^, Si"*"^, and Fe "*" are

preferentially left behind in residual mineral phases. Oxidation

of sulfide minerals produces hydrogen ions, which can induce

further weathering, and dissolved sulfate. Cation exchange on

newly formed clay minerals favors retention of the divalent

cations Mg^""" and Ca^"*" in freshwater environments. High

rates of evapotranspiration relative to rainfall in arid climates

can serve to increase the TDS of soil waters.

Mineral-fluid and organic reactions continue as ground-

water migrates along flow paths within the saturated zone,

flow paths which are determined by spatial variations in

permeability and hydraulic head. The local presence of

evaporite minerals such as halite, anhydrite, and gypsum can

add Na, CI, Ca, and SO4 to the groundwater. As the

groundwater flows down gradient from recharge areas it may

encounter progressively reducing conditions as dissolved

oxygen is depleted by aerobic respiration. Nitrate, manganese,

amino acids, iron, and organic carbon are the typical

succession of electron acceptors microbes then use to oxidize

organic carbon as subsurface conditions pass progressively

from oxidizing to reducing (Chapelle, 1993), When conditions

become sufficiently reducing, the reduction and dissolution of

Fe and Mn minerals commonly gives rise to significant

concentrations of these metals in shallow groundwaters. With

a further decrease in redox state, however, sulfate is reduced to

sulfide, and Fe may be precipitated out as an Fe-sulfide,

In carbonate aquifers, it is not surprising to find ground-

waters dominated by Ca-HCO3 or Ca-Mg-HCO3 as the

principal solutes, A well-studied example is the Floridian

540

POREWATERS IN SEDIMENTS

Aquifer in central Florida (Sprinkle, 1989), tn silieielastic

aquifers, however, there is typically a progression from Ca-Na-

HCO3 waters in shallow recharge areas to Na-Ca-HCO3 and

then Na-HCO3 waters further down dip. Examples include the

US,

Atlantic and Gulf coastal plain aquifers, where bicarbo-

nate concentrations increase down flow paths from initial

values of less than 50 mg/L to over 500 mg/L (Chapelle, 1993),

The probable source of CO2 is bacterially oxidized organic

material present in the aquifers and/or the interbedded

aquicludes. The origin of high Na-HC03 groundwaters in

silieielastic aquifers has been a matter of some debate. One

school of thought holds that the removal of Ca is predomi-

nantly by ion exchange, the other that Ca is removed as

CaCO3 by the introduction of HCO3,

Continental brines

In arid continental climates where potential evapotranspira-

tion far exceeds rainfall, circumstances can exist which give rise

to the formation of brine lakes. Well-known examples include

Lake Magadi, Kenya; Lake Tyrrell, Murray Basin, Australia;

and Great Salt Lake, Utah, The composition of the brines

produced depends critically on the relative proportions of Ca,

HCO3,

SO4, and Mg in the fluid being evaporated. Documen-

ted brine types include Na-Ca-Mg-Cl, Na-Mg-SO4-Cl, and

Na-CO3-SO4-Cl saline waters (Eugster and Hardie, 1978),

These brines recharge into underlying sediments as a result of

density-driven flow, where dissolved Mg is removed by the

formation of Mg-rich smectite, sepiolite, Mg-calcite, and/or

dolomite, and sulfate can be reduced by reduction to sulfide. In

contrast to freshwater conditions where ion exchange favors

the adsorption of divalent cations, monovalent cations,

particularly K, are preferentially adsorbed on clays in saline

conditions and removed from solution.

Porewaters in marine sediments

Fluid flow and solute transport in many marine sediments,

particularly in deep sea pelagic and hemipelagic sediments are

dominated by compaction-driven advection and molecular

diffusion (Berner, 1980), More dynamic fluid environments are

found on continental shelves, where topographically driven

meteoric fluids can mix with marine porewaters; in accre-

tionary prisms, where there is well-documented seaward

expulsion of fluids; and along mid-ocean rises and ridges and

other submarine volcanic settings, where thermal convection

operates (Hesse, 1990),

Seawater is a Na-Ci dominated fluid with SO4, Mg, Ca, and

K as the other major species. The relative proportion of these

solutes is nearly constant throughout the world's oceans, with

the exception of S04-depleted, anoxic bottom waters in closed

submarine basins. Much of the water trapped in pelagic and

hemipelagic sediments at the time of deposition is seawater.

This water, however, undergoes continuous chemical diagen-

esis and a change in composition with time and depth of burial

(Hesse, 1990; Schuiz and Zabel, 2000), There is typically a

systematic increase in Ca and systematic decreases in Mg and

K with depth. The variations in Ca and Mg are generally

thought to be the result of hydrolysis of silicate minerals in

underlying oceanic basement basalts. The downward decrease

in dissolved K may be related to the formation of the

potassium-bearing zeolite, phillipsite, and adsorption by ion

exchange on clays. There is often a distinct downward decrease

in 5'*0 values of marine interstitial waters, commonly

interpreted as resulting from preferential removal of heavy

oxygen by the formation of phyllosilicates in altered igneous

rocks and volcaniclastic sediments. Increases in 5'^0 increases,

however, have been noted in gas-hydrate bearing sections of

DSDP cores. Elevated temperatures and enhanced reaction

rates associated with submarine hydrothermal activity, such as

in the Guyamas Basin, methase release of Ca and uptake of

Mg by hydrothermally altered basalts and volcaniclastic

sediments. There are also documented increases in dissolved

Li,

K, and Rb in these areas.

Silica concentrations are typically highly variable with depth

and are dependent on lithology. Elevated silica concentrations,

for example, are found in siliceous oozes, Recrystallization of"

biogenic pelagic carbonates releases substantial amounts of Sr

but does not seem to have a significant effect on Ca

concentration gradients.

With the exception of dissolution of evaporite minerals,

chloride does not participate in mineral-fluid reactions in the

subsurface. Its behavior is thus said to be conservative. As a

conservative species chloride often does not display vertical

concentration gradients in marine sediments. The ciianges in

chloride which have been observed in evaporite-free sections

result from mixing with freshwater released from gas hydrates,

loss of water in hydration reactions, and possibly slight changes

in seawater chlorinity during glacial-interglacial cycles. There

is typically a reduction in porewater chloride and salinity in

decoilments and faults in accretionary wedges as a result of

dehydration reactions and large-scale fluid expulsion.

In more organic-rich hemipelagic sediments redox condi-

tions become progressively reducing with depth. As a result of

a progression of redox reactions similar to those which

characterize continental groundwaters, dissolved ammonia,

phosphate, and alkalinity typically increase in the upper part

of the sediment column, and dissolved sulfate is reduced

(Berner, 1980),

Saline waters in deep sedimentary basins

The hydrogeology of deep sedimentary basins is less well-known

quantitatively than that of shallow groundwater systems, but

deep basin circulation plays a key role in controlling the salinity

and composition of basinal fluids through advection and

dispersive mixing of fluids of varying salinity. The deep pore

fluids in many sedimentary basins are overpressured, i,e,, they

exhibit fluid pressures in excess of hydrostatic pressures. There

has been considerable debate on the origin of overpressuring

(Hanor, 1988), but rapid deposition of fine-grained sediment of

low permeability is one likely mechanism. There is evidence

from variations in salinity and fluid composition that over-

pressured fluids can be episodically expelled upward into

overlying hydropressured sediments (Roberts and Nunn,

1995),

The presence of bedded and diapiric evaporites provide

other mechanisms for inducing fluid flow. The dissolution of

halite produces dense brines which can eonvect downward.

Salt, however, is also an excellent conductor of heat, and there

have been documented examples of upward fluid flow along the

flanks of warm salt domes (Hanor, 1994),

Sources of chloride and controls on salinity

Pore waters in the deeper parts of sedimentary basins,

including basins now part of the continental crust, and basins

POREWATERS IN SEDIMENTS

541

containing tectonically deformed sedimentary sequences, are

typically saline. The salinities are commonly higher than that

of seawater (35,000 mg/L) and can range from 100,000 mg/L to

150,000 mg/L in basins with salt domes to over 350,000 mg/L

in basins with bedded basal evaporites. In some sedimentary

basins, such as the Illinois, Alberta, and Michigan basins, there

is a progressive increase in salinity with depth. In other

sedimentary basins, such as the Gulf of Mexico basins there

can be reversals in salinity with depth (Hanor, 1988), In the

mid-20th century, much discussion was given to the origin of

high salinity by the process of membrane filtration or

reverse osmosis. In this process overpressuring forces un-

charged water molecules through clay membranes, but the

negative charge on the clay particles repels charged ions and

produces high concentrations of solutes on the influent side of

the membranes. Most workers today, however, consider the

chloride in basinal brines to have been introduced by some

combination of the subsurface dissolution of halite (Land,

1997) and the infiltration of subaerially evaporated marine

waters (Carpenter, 1978), During the evaporation of seawater,

Br preferentially remains in solution while CI is precipitated

out, first as halite and then as K and Mg salts (McCaffrey

et al., 1987), Brines formed by dissolution of halite thus

typically have low Br/Cl ratios, which reflect the low Br/Cl

ratio of the parent halite. Brines formed by the subaerial

evaporation of seawater, in contrast, typically have elevated

Br/Cl ratios.

Major solutes

Most basinal brines of moderate salinity are dominated by

dissolved Na and CI. As salinity increases, however, there is a

progression from Na-Cl to Na-Ca-Cl to Ca-Cl brines. The

controls on the composition of basinal brines have been

discussed and debated for a century and a half (Hanor, 1988),

In the mid-1800s it was proposed that the high Ca concentra-

tions were connate or syngenetic in origin and reflected high

Ca/Na ratios of ancient seawater, a hypothesis which is no

longer accepted. Although most of the chloride in basinal

brines is derived from halite dissolution or from marine and

evaporated marine waters, basinal brines have neither the

composition of a NaCI solution or of evaporated marine

waters. Instead, there are systematic increases in Na, K, Mg,

Ca, and Sr with increasing salinity. The 1:1 slope of the

monovalent cations and 2:1 slope of the divalent cations on

log-log plots is consistent with the buffering of brine

compositions by multi-phase silicate and carbonate mineral

assemblages (Hanor, 1994), The phases involved most likely

include minerals such as quartz, K-feldspar, albite, illite,

smectite, chlorite, calcite, and dolomite. The general decrease

in pH and carbonate alkalinity with increasing salinity is also

consistent with rock-buffering of fluid compositions, Sulfate

concentrations, in contrast to the other major solutes, do not

show any systematic variations with salinity, Sulfate con-

centrations instead are controlled by anhydrite dissolution and

the reduction of sulfate to sulfide, Basinal brines and gases

in iron-poor sediments can contain significant concentrations

of H2S,

Organic and tieavy metals

Volatile fatty acids (VFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and

butyrate, are found in concentrations exceeding 100 or even

1000 mg/L in some basinal waters. These waters tend to be of

low salinity and may reflect water released from hydrocarbon

source rocks during maturation of organic matter. Under

conditions of high fluid pressure, concentrations of dissolved

methane exceeding several thousand mg/L can be forced into

solution,

Basinal brines have long been considered the fluids involved

in the formation of some sediment-hosted ore deposits,

including Mississippi Valley Type (MVT) and sedimentary-

exhalative (SEDEX) deposits. Although much consideration

has been given to the role of organic complexing agents, such

as acetate, in solubilizing heavy metals such as Pb and Zn,

more recent work has shown that chloride is the key

complexing agent (Hanor, 1997), At chloride levels in excess

of

100

g/L, the PbCll" and ZnCl^" complexes become effective

solubilizing agents for Pb and Zn, Barite (BaSO4) is also a

common mineral phase in MVT and SEDEX deposits. High

concentrations of Ba are found in those basinal brines that

have low sulfate concentrations.

Isotopic composition

The isotopic composition of basinal brines is significantly

influenced by diagenetic reactions. Exchange of oxygen with

silicate minerals can increase the <5'*0 values of basinal

waters and the introduction of H from maturation of organic

matter can lower 5^H values. Other changes include the

introduction of radiogenic *'Sr and changes in the Li and B

isotopic compositions from the diagenesis of silieielastic

sediments.

Summary

Even though the salinity and composition of porewaters in

sediments and sedimentary rocks varies widely, many of these

variations are systematic and can be explained in terms of

basic principles of solute transport and chemical reaction.

In terms of major solutes, redox reactions involving organic

matter are important in influencing the concentrations of SO4

and HCO3 in all porewaters. Reactions involving sili-

cates,

carbonates, and evaporites, however, are the ultimate

controls on the addition and removal of Na, K, Mg, Ca,

and CI,

As a group, meteoric groundwaters have the highest

variation in proportions of major solutes, which reflect highly

dynamic flow systems and local lithologic control on water

compositions. Many interstitial marine waters still retain a

strong seawater signature despite on-going organic and

mineral diagenesis, Diffusional exchange with overlying sea-

water and within the sediment column is one factor contribut-

ing to the buffering of fluid compositions in these sediments.

Saline waters in deep sedimentary basins show systematic

changes in the concentrations and relative proportions of most

major solutes, reflecting rock buffering involving multiple

sediment lithologies.

Much work remains to be done in quantifying our under-

standing of the controls on the properties of pore fluids,

including establishing the driving forces and rates of solute

transport and the kinetics of the diagenetic reactions which

cause mass transfer to occur between porefluids and their

sedimentary matrix,

Jeffrey S, Hanor

542

PRESSURE SOLUTION

Bibliography

Appelo, C,A,J,, and Postma, D,, 1993,

Geochemistry,

Groundwater,

and

Pollution. Rotterdam: A,A, Balkema,

Back, W,, 1961, Techniques for mapping hydrochemieal facies, US

Geological

Survey Professional

Paper,

424 (D): 380-382,

Berner, R,A,,

\9%Q.

Early

Diagenesis:

ATheoretical Approach. Princeton

University Press,

Carpenter, A,B,, 1978, Origin and chemical evolution of sedimentary

brines in sedimentary basins. Oklahoma Geological Survey Circular,

79:

60-77,

Chapelle, F,H,, 1993, Ground-Water Mierohiology and Geochemistry.

Wiley,

Domenieo, P,A,, and Schwartz, F,W,, 1990, Physical and Chemical

Hydrogeology. New York: Wiley,

Drever, J,I,, 1997, The Geochemistry of Natural Waters, Surface and

Groundwater Environments, 3rd edn, Prentiee-Hall,

Eugster, H,P,, and Hardie, L,A,, 1978, Saline Lakes, In Lerman, A,

(ed.).

Lakes—Geochemistry,

Geology,

Physics. New York: Springer-

Verlag, pp. 237-293,

Hanor, J,S,, 1988, Origin and Migration of Suhsurface Sedimentary

Brines, SEPM Short Course No. 21, Tulsa: Society of Economic

Paleontologist and Mineralogists.

Hanor, J.S,, 1994. Physical and chemieal eontrols on the composition

of waters in sedimentary basins. Marine and

Petroleum

Geology,

11:

31-45,

Hanor, J,S,, 1997. Controls on the solubilization of dissolved lead and

zinc in basinal brines. In Sangster, D,F, (ed.), Carhonate-Hosted

Lead-Zinc Deposits, Littleton: Society of Economic Geologists,

Special Publication, 4, pp. 483-500.

Hesse, R,, 1990, Early diagenetic porewater/sediment interaction:

modern offshore basins. In Mcllreath, LA., and Morrow, D.W.,

(eds.),

Diagenesis, Geoscience Canada Reprint Series

4,

pp, 277-316.

Land, L,S,, 1997. Mass transfer during burial diagenesis in the Gulf of

Mexico Sedimentary Basin: an overview. In Montanez, L, Gregg,

J,M,, and Shelton, K,S, (eds,), Basinwide Fluid Elow and Assoeiated

Diagenetic Patterns, Tulsa: (SEPM) Society for Sedimentary

Geology, Special Publication, 56, pp, 29-40.

Liehtner, P.C., Steefel, C.L, and Oelkers, E,H, (eds.), 1996, Reactive

Transport

in Porous Media, Reviews in Mineraiogy 34. Mineralogieal

Society of America,

McCaffrey, M,A., Lazar, B,, and Holland, H.D,, 1987, The evapora-

tion path of seawater and the eopreeipitation of Br~ and K+ with

halite, Journai of Sedimentary

Petrology,

57: 928-937,

Roberts, S,T,, and Nunn, J,A,, 1995. Episodic fluid expulsion from geo-

pressured sediments. Marine and

Petroleum

Geology, 12: 195-204.

Schuiz, H,D,, and Zabel, M, (eds,), 2000, Marine Geoehemistry.

Springer-Verlag,

Sprinkle, C.L., 1989, Geoehemistry ofthe Floridian aquifer system in

Florida and in parts of Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama,

U.S.

Geological

Survey Professional

Paper,

1403-1,

Cross-references

Diagenesis

Diffusion, Chemical

Evaporites

Fabric, Porosity, and Permeability

Hydrocarbons in Sediments

Isotopic Methods in Sedimentology

Oceanic Sediments

Weathering, Soils, and Paleosols

PRESSURE SOLUTION

A grain-scale mechanism of ductile and

water-assisted deformation

The transition from loose sediments to hard rocks arises

through physico-chemical processes at the grain scale. Pressure

solution, in addition to cataclasis, grain sliding, and plastic

deformation, is one of these processes. Pressure solution takes

place when some aqueous fluid coating is present around the

grains. It is a water-assisted diffusional mass transfer normally

occurring in the top few kilometers of sedimentary basins and

in other geological environments such as fault gouges and low-

grade metamorphie rocks. This slow mechanism of deforma-

tion can induce large amounts of ductile strain over geological

times when stress and temperature are not high enough to

promote brittle or plastic deformation.

The classical pressure solution structures have been de-

scribed since the last century, for example by Sorby in 1863,

They include grain and pebble indentations, stylolites, partly

dissolved voids, dissolution seams, and crenulation cleavage.

Since, extensive field evidence has accumulated which confirms

the prevalence of this mechanism in nature.

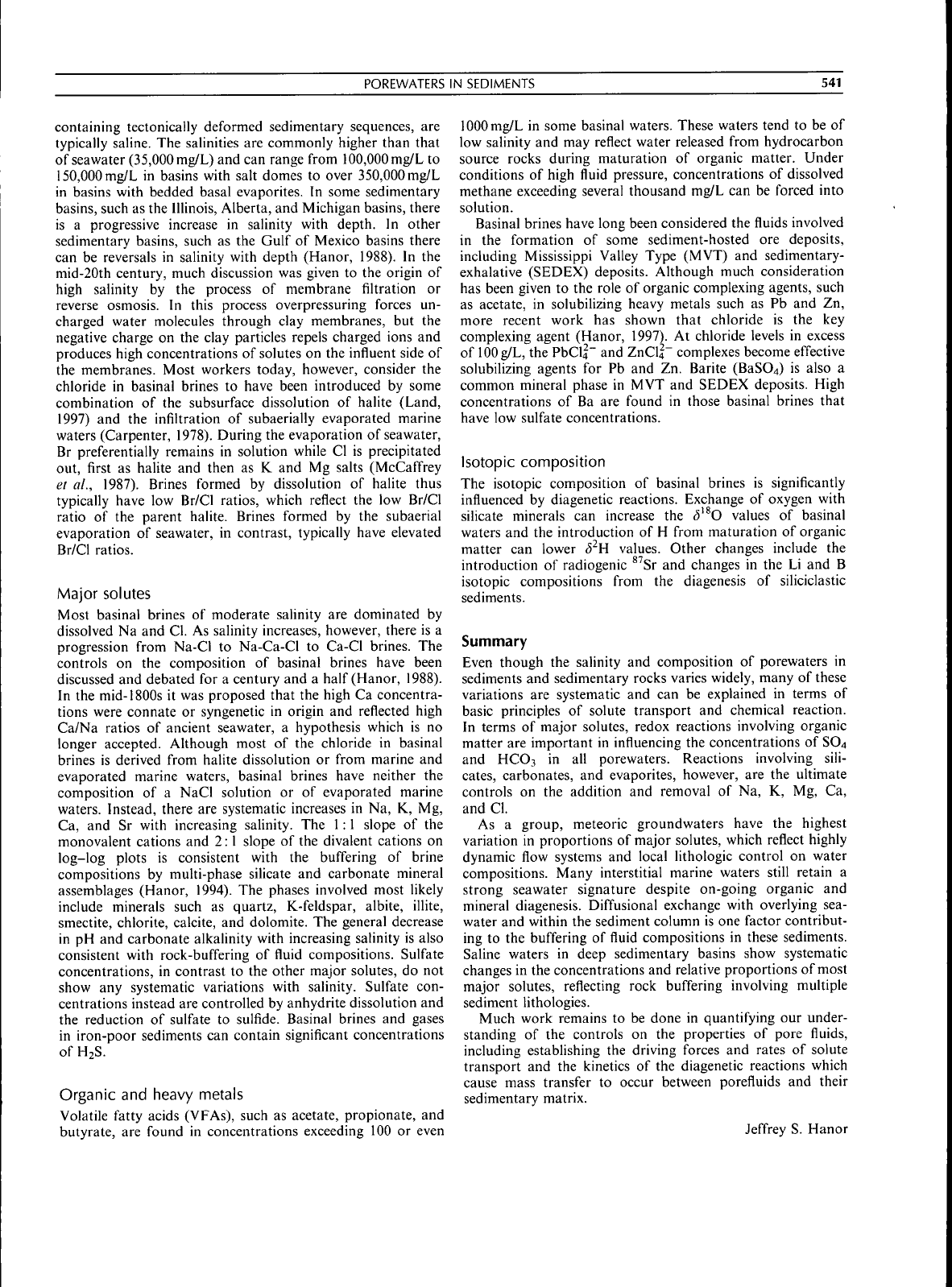

Following Sorby's pioneering observations, Weyl (1959)

performed the first quantitative interpretation of pressure

solution and proposed that the driving force for the deforma-

tion be related to stress concentration at grain or pebble

contacts. From natural observations such as those of

Figure PI2, he deduced that deformation by pressure solution

involves several successive steps: dissolution at the grain

contacts, transport of the dissolved solutes toward the open

pore,

precipitation in the pore or transport to other pores. This

results in an indentation of the grains into each other and a

decrease of rock porosity resulting in a ductile compaction,

Mechano-chemical processes

A crucial parameter for pressure solution is the presence of

water in the pores, which acts as a medium of reaction and

transport with the minerals. If a porous medium is not

saturated with respect to water, pressure solution will be

localized in the pores where water is present. This effect can

create compacted regions in the sediment whereas the porosity

of other regions will not be modified.

At the grain scale, pressure solution deformation occurs

through three serial steps, the whole process being driven by

stress gradients along the grain surface. First, minerals dissolve

at grain contacts because of a concentration of stress. The

stress variation between the grain contact and the pore surface

can be related to the cliemical potential of the dissolving

mineral (Paterson, 1973), The result is that the coriceritratipn

in aqueous species is greater in the contact film and induces a

gradient of concentration between the contact film and the

pore.

The second step involves solutes in the contact film

diffusing along the grain boundaries. The nature of the

interface between two grains is crucial because it is a medium

of dissolution and diffusion of matter. It is assumed that some

water is trapped inside this interface. And the third and last

step is precipitation on the free face of the grains. Note that

solutes can be transported by diffusion in the pore fluid and

precipitate at some distance from the dissolution area. This

provides an explanation of mass transfer at centimeter scale in

sedimentary environments under local gradients of stress.

If one of these three steps is slower than the two others, it

will control the kinetics of the overall deformation. For

example, diffusion within grain contact films controls the

compaction of salt aggregates at room temperature. In

sedimentary basins, compaction of quartz-rich sediments is

limited by the step of quartz precipitation between 3 km and

5 km and by the diffusion at the grain contact below

5

km,

PRESSURE SOLUTION

543

Figure

P12

Pressure soluliun

,Tt

grain scale:

(A)

Indentation

ol two

L.irbon.ile

lossiU

in a

limestone, Mons, Belgium;

(B)

Indonlation

of a

grain

of

quartz

by a

mica flake

in a

sandstone trom

ihe

Norwegian

shell.

Above

3

km, pressure soltition remains so slow that its rate can

be neuleeted.

Experimental insights

Attempts to reproduce the mechanism and to obtain quanti-

tative infortnation in the laboratory have proved diftieult

however, owing to incomplete analysis of samples" geometry

used in L'\perimenta! study and to the confounding influence of

other deformation meehanisms that ean operate concurrently

in the experiments. The experiments can be divided in two

categories: single contact (Hickman and Evans. 1991) and

aggregate compaetion (Rutter. 1976; Gratier and Guiguet.

19S6) experiments. The fortner experiments give insights on the

meehanism of deformation itself on a single grain whereas the

results ofthe latter are average creep laws. Recent experiments

on rock salt, gypsum and quartz aggregates have shown that

pressure solution rate increases

when;

(1) temperature inereases

(with an activation energy between

15

kJ/mole and

SO

kJ/mole);

(2) effective stress inereases; (3) grain size deereases.

Such experiments indicate that geometrical parameters

control the pressure solution rate sueh as grain size and the

geometry of the grain-grain interface. Knowledge of the

geometry permits the estimation of the path length for

diffusion of the solutes from the eontacts to the pore space.

Physico-chemical variables of importance inelude temperature,

stress, chemistry ofthe pore water, mineralogy ol the rock, and

transport properties of the grain contacts.

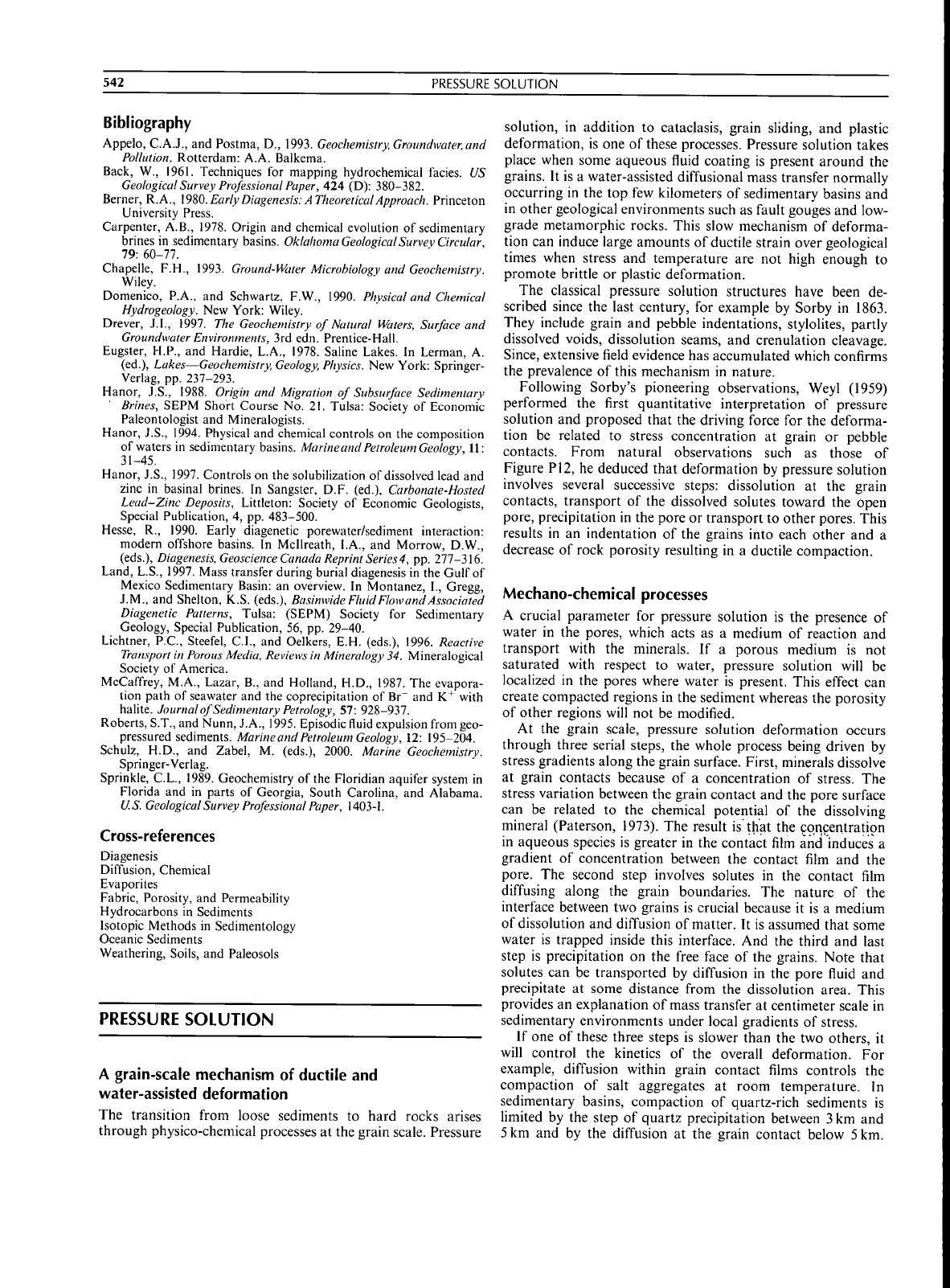

Ductility of the upper crust

Pressure solution, as a time-dependent process, is responsible

for a slow ductile creep of the rocks. Modeling pressure

solution requires taking into account the evolution of Ihe roek

texture and grain geometry (Figure P13) during deformation

as the contact area and the pore surface vary during

deformation. Sueh models allow investigating the sensitivity

to the main input parameters: transport properties at grain

contacts, grain size, temperature, and stress, Typieal results of

these models eoneern the viscosity of compaetion of sedimen-

tary rocks and the time-scale relevant to eompaetion pro-

cesses, }-\ir example, preliminary results indieate that the

viscosity of eompaetion of silico-clastic sedimentary rocks

ranges between lO''* and lO'"' Pa

s

depending on temperature,

grain size, stress, and mineralogy; values which are similar to

what can be deduced from field-based observations.

g compaction-

Figure

PI

3

A

cross-section view

ot a

cubic pocked network

of

truncated spheres used

to

model pressure solulion.

The

grain shapes

evolve

due to

pressure solution:

the

grain radius

i,

increases while

ihe

grain flattens

it^

decreases! resulting

in the

porosity

and Ihe

pore

surface decrease. Such models

can he

applied

in

sedimentary basin

conditions

to

model compaction.

Still unresolved questions associated with the basie under-

standing of the process of pressure solution remain. For

example, the dominating driving foree and meehanism of

dissolution, the geometry ofthe grain boundaries, the structure

and transport properties of the aqueous fluid in thai grain

boundary, and the infiuenee of pore fluid compositions

represent challenging issues for aetual research.

In the upper erust pressure solution results in a slow proeess

of dissipation of stress energy stored during sedimentation and

burial or by teetonic forces. Field observations indieate that

pressure solution is intimately assoeiated with brittle processes

of deformation, for example on active faults where earth-

quakes are eharaeteristic of

a

brittle behavior whereas pressure

solution retiiains the main mechanism of deformation during

the interseismic period.

Frant;ois Renard and Dag Dysthe

Bibliography

Gralier,

J.P., and

Giiigtiet,

R,,

I98(S, ExpcrimetUal pressure solulion-

depositioti

on

qaariz grains:

the

crucial etlect

of the

naltirc

of ihe

fluid,

.fournalof Struetund

Geology.

8: S45 S56,

Hiekman,

S,H,,

and

Hvans,

R,,

19'JI,

F_\perimem;il presstirc solulion

in

halite:

the

effect

of

grain/interphasc boundary siructure, .foarnalof

ilic

Geological .Society

of London,

148: 549 560.

Paterson,

M,S,,

197."^, Nonhydrostatic thermodynamies

and its

geologic appliciUions,

Reviens

of

Geophysics

ami

.Space

Physics.

11:

355-.189,

Rutier,

E,H., 1976. The

kinelics

of

rock dclormaiion

by

pressure

solulion.

Phihi.sophical

Trim,sad ions

of

the Royal Society

of

London.

283:

203 219.

Sorby,

H,C.. 1863, On the

direct correlation

of

mechanical

and

chemical forces.

Proeeedim^s

of

the

Royal Society

of

London.

12:

53S-.S.SO.

Weyl.

P.K., 1959,

Prcssure-solulion

and the

force

of

crystallization

a

phenomenologiciil theory. Journal

of

Geophrxieal Researeh.

64:

2001-2025,

Cross-references

Cements iind Cementaiion

Compaction (Consolidation)

of

Sediments

Delormalion

oi'

Sediments

Diagenesis

Diagenetic Struetures

Grain Size

and

Shape

Stylolites

544

PROVENANCF

PROVENANCE

Introduction

On Eiirtli. sedimentation is diivcn principally by tectonic

forces, subordinately by climatic iind eustatic forces, and to a

minor extent in response to impact processes. Detrital

sediments retain a record of eroded crustal material. Knowl-

edge of crusts ofthe past is gleaned from provenance studies.

Tracking the immediate and ultimate sources and origins of

sediments, principally of silieielastic sedimeiils. is the domain

of" provenance studies. In addition, estimating amounts,

proportions, and rates of supply of sediments from multiple

sources is also within the purview of provenance studies.

Contemporary investigations, therefore, focus not only on

types,

identification, and tectonic settings of source rocks, or

the climatic conditions in source areas, or paleogeographie

localities of source areas, but also on quantitative distributions

of source material and the kinematics of source area tectonics.

Approaches, i.e,, methodologies of investigations, depend

generally on the purpose ofthe investigators and (he scientific

questions address by them, but are largely multidisciplinary

and diverse (Zuffa, 19S5; Morton etal.. 1991; Johnsson and

Basu, 1993; Bahlbourg and Floyd, 1999; DeCelles elal.. 19yS).

No parent rock or parent roek-assemblage is ever fully

preserved in any sediment, Beeause post-derivation weath-

ering, transport, and depositional, and espeeially diagenetic

processes determine the preservation potential of original

detrital signatures and lead to disproportionate representation

of parent material in sediment, methodologies have to be

appropriately adapted in specific cases. We discuss some of the

methods before deseribing the results and the kinds of

inferences made in a few recent studies.

The detective work to infer provenance is thus equivalent lo

restoring a jigsaw puzzle with many missing and damaged

pieces.

Historical

Provenance studies have prompted and progressed with newer

instrumentation to determine sediment properties. More than

50 years ago color and shapes of heavy minerals were guides to

parent rocks; some 25 years ago detrital zircons were separated

on the basis of color and shape to obtain U-Pb age-dates to

identify sources in the igneous basement of the Potsdam

Sandstone; currently, age-dating of and oxygen isotope

systematics in single crystals of detrital zircon provides

iiifonnation on the genesis and recycling of crustal roeks.

Similarly, optical microscopic observations are now supple-

mented by backseattercd eleetron image analyzes; ehemical

compositions of sediments extend beyond major element to

trace and rare earth element distribution; and, chemical and

isotopic compositions of single detrital grains are dclermined

by using electron and ion mieroprobes.

Approaches

Methodologies of provenance determination are broadly

divisible into three types: petrographie, ehemical, and isotopic.

Ail three types are increasingly used in provenance interpreta-

tion. Except for the uncommon occurrence of some index

mineral (e.g., glaucophane to indicate a blueschist-type souree

rock) or an index fossil (e.g.. coeval taxa from a disintegrating

bank into a deep sea turbidite). most eontemporary data are

quantitative in nature. Statistical principles of point-counting

methods are applied in most measurements.

Petrographic

Mineralogic compositions and elassification of sandstones

have been linked to source rocks for a long time. For example,

arkosic sandstones and conglomerates, many with granitic

rock-fragments, have been linked to continental shields, and,

lithic graywacke sandstones, many with volcanic and schistose

rock fragments, have been linked to orogenic sources. Relative

concentrations of detrital quartz (Q), feldspar (F), and rock

fragments (R) define sandstone classification. Because the

proportion of roek fragments increases with the increasing

grain size of sediments, and. because quartz and feldspars also

oeeur in rock fragments, estimating the proportions of QFR is

difficult. Results of QFR determination differ depending on

the methodology used especially in treating the grain-size

effect. Some investigators restrict the grain size range of

samples, for example, to medium sand si/e (0.25 0.50mm) for

sandstones. Others point-count quartz and feldspars in coarse-

grained roek fragments as mineral fragments, and restrict

the eounts of rock fragments, designated as lithics (L), to very

fine-grained sedimentary, schistose, and voleanie grains.

Composition fields in QFL space (triangular diagrams) are

sensitive to detritus from different tectonic regimes (Dickinson,

1985),

This is especially true if very fine-grained aggregates of

quartz ( polycrystalline quartz; chert) are assigned to the L-

polc leaving the Q-pole reserved for monocrystalline quartz

only. This converts the QFL diagram to a Q,,,FL, diagram.

Although the fields in OFL/Q,,,I-X, diagrams are intended to

be guides, many sandstone petrologists tend to use a

classificatory approach lo infer tectonic provenance. The

diagram was modified later to erase definitive eompositional

fields emphasizing the essence of the relationship between

sandstone composition and teetonic provenance (Dickinson,

1988;

Figure PI4).

The QFL approach has two limitations. First, errors

associated with the boundaries of compositional fields are

large. Seeond, it ignores the information contained in rock

fragments; especially that carbonate grains may be inlrabasinal

and coeval with the hosl sediment or extrabasinal and

oldcj-

detritus. Both are useful as provenance indiealors. Never-

theless, point counting by the Gazzi Dickinson method, using

QFL/Q||,FL,, is the preferred mode for inferring tectonic

provenance from petrographie analysis of bulk sediments.

Climate profoundly affects mineralogical and ehemical

compositions of sediments. Under wann and wet conditions

relative to cold and dry eonditions. rock-fragments break

down to their constituent minerals more rapidly; they become

depleted in a sediment while quartz, being the most durable

mineral at Earth's stirtace, is enriehed relative to other

minerals. Duration of weathering, be it at roek-outerops or

while a body of sediments is parked temporarily (e,g,, river

valleys, deltas, coastal plains, beaches), contribute to the

degree of quartz enrichment. Common upper erustal meta-

morphie roeks are generally enriched in quartz and are finer

grained than eommon igneous roeks (feldspar-rich and eoarser

grained). Therefore, il is possible to differentiate between

sediments derived principally from metamorphie and igneous

rocks under similar climatic conditions: and, to assess relative