Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

R

RED BEDS

"Red Beds" is the term applied to sedimentary sequences

which are predominantly red in color but usually associated

with variable proportions of interdigitated drab strata,

typically grey, grey-green, brown, or black. They comprise a

wide range of facies representing the whole spectrum of non-

marine depositional environments from alluvial fans, river

floodplains, deserts, lakes, and deltas, and range in age from

Early Proterozoic to Cenozoic. Red beds are economically

significant; they host a large number of oil and gas reservoirs

and are associated with tabular copper and uranium-

vanadium deposits (Rose, 1976; Hansley and Spirakis, 1992).

Oxidation-reduction reactions play a key role in the formation

of red beds in both the depositional and post-depositional

settings. The nature and abundance of organic material is thus

a key factor in determining the particular characteristics of a

red bed sequence.

Red beds are colored by finely disseminated ferric oxides,

usually in the form of hematite (oc-Fe203) and generally

have a color between 5R and IOR of the rock color chart

(Goddard, 1951). Oxidation-reduction (Eh) and pH control

hematite formation and the observed minor color variations

seen in red beds. In general, the color variations relate to

changes in pore water chemistry resulting from fluctuations in

depositional or early diagenetic environment. In particular,

intercalated marine units are normally non-red because of the

reducing conditions generated below the sediment-water

interface and such color changes can be a sensitive indicator

of base level shifts in marginal marine sequences. The

occurrence of ferric oxides in red beds indicates that they

formed under oxidizing conditions and that the Earth's

atmosphere was oxidizing. In this context they hold great

significance for the evolution of life and much of the key

evidence for the evolution of terrestrial faunas and floras

including amphibians, reptiles (including dinosaurs) and

mammals is found in red bed sequences. However, although

it is clear, no particular paleocJimatic significance can be

attached to them, since they are known to form in both arid

and moist tropical climates.

In the past the actual mechanisms of red bed formation have

been widely debated and we now know that red beds are

polygenetic in origin. The conditions for red bed formation

necessarily coincide with those that are needed for hematite

fonnation since this mineral causes the red coloration. These

include positive Eh and neutral to alkaline pH, conditions

which, at the surface at least, are met in hot, continental low

latitude areas. Marine red beds are rare because of the

abundance of organic material in the marine environment.

They do, however, constitute a distinct group of red beds and

are included in the classification here. Three principle

mechanisms have been proposed to explain the origin of the

red color in continental red beds, each relating to a different

stage in the depositional and diagenetic history. Four groups

of red beds are recognized as follows:

(1) Primary red beds. Deposition and early diagenesis from the

erosion of lateritic soils in wet uplands and the aging of

ferric hydroxides, especially in the pedogenic environment;

(2) Diagenetic red beds. Burial diagenesis and the intrastratal

solution of ferromagnesian silicates;

(3) Secondary red beds. Weathering and ferruginization of

non-red strata after uplift;

(4) Marine red beds. Very low organic productivity and slow

sedimentation rates resulting in oxic conditions below the

sediment-water interface.

Primary red beds

Krynine (1950) suggested that red beds were formed primarily

by the erosion and redeposition of red soils or older red beds.

A fundamental problem with this hypothesis is the relative

scarcity of recent red colored alluvium, and Van Houten

(1961) developed the idea to include the in situ (early

diagenetic) reddening of the sediment by the dehydration of

brown or drab colored ferric hydroxides. These ferric

hydroxides commonly include goethite (oc-FeOOH) and

socalled "amorphous ferric hydroxides" or limonite. In fact,

much of this material may be the mineral ferrihydrite which

has a composition near 2.5 Fe2O3

•

4.5 H2O. This dehydration

556

RED BEDS

or "aging" process is now known to be intimately asso-

ciated with pedogenesis in alluvial floodplains and desert

environments.

Berner (1969) showed that ferric hydroxide (goethite) is

nonnally unstable relative to hematite and in the absence of

water or at elevated temperature will readily dehydrate

according to the reaction:

2 oc-FeOOH (goethite)

ematite) + H2O

(Eq. 1)

The Gibbs free energy (AGr) for this reaction at 25°C is

-2.76kJ/mol and Langmuir (1971) showed that AGr becomes

increasingly negative with smaller particle size. Thus detrital

ferric hydroxides including goethite and ferrihydrite will

spontaneously transform into red colored hematite pigment

with time. This process not only accounts for the progressive

reddening of alluvium but also the fact that older desert dune

sands are more intensely reddened than their younger

equivalents. Folk (1976) sliowed that the red color of dune

sands in the Simpson Desert of Australia was formed during

an older period of lateritization and subsequent dehydration of

the ferric hydroxides. This paper formed a good model for the

reddening process in ancient eolian dune sequences.

Diagenetic red beds

The formation of red beds during burial diagenesis was clearly

described by Walker (1967) and Walker etal. (1978). The key

to this mechanism is the intrastratal alteration of ferromagne-

sian silicates by oxygenated groundwaters during burial.

Walker's studies show that the hydrolysis of hornblende and

other iron-bearing detritus follows Goldich's stability series.

This is controlled by the Gibbs free energy (AGr) of the

particular reaction. For example, the most easily altered

material would be olivine:

FeSiO4(fayalite)-f 0.502^ a:-Fe2O3

SiO2(quartz) (Eq. 2)

with AGr= -27.53 kJ/mol

A key feature of this process, and exemplified by the

reaction, is the production of a suite of by-products which are

precipitated as authigenic phases. These include mixed layer

clays (illite-montmorillonite), quartz, potash feldspars, and

carbonates as well as the pigmentary ferric oxides. Reddening

progresses as the diagenetic alteration becomes more advanced

and is thus a time-dependent mechanism. The other implica-

tion is that reddening of this type is not specific to a particular

depositional environment. However, the favorable conditions

for diagenetic red bed formation, i.e., positive Eh and neutral-

alkaline pH are most commonly found in hot, semi-arid areas,

and this is why red beds are traditionally associated with such

climates.

Secondary red beds

Secondary red beds are characterized by irregular color

zonation, often related to sub-unconformity weathering

profiles. The color boundaries may cross-cut lithological

contacts and show more intense reddening adjacent to

unconformities. Johnson etal. (1997) have also showed how

secondary reddening phases might be superimposed on earlier

formed primary red beds in the Carboniferous of the southern

North Sea. The general conditions leading to post-diagenetic

alteration have been described by Mucke (1994). Important

reactions include pyrite oxidation:

3O2 +4FeS2

and siderite oxidation:

ematite) + 85"°AGr = -789kJmor'

(Eq. 3)

r= - 346kJmor'

(Eq.

4)

Secondary red beds formed in this way are an excellent

example of telodiagenesis. They are linked to the uplift,

erosion, and surface weathering of previously deposited

sediments and require conditions similar to Primary and

Diagenetic red beds for their formation.

Marine red beds

The scarcity of marine red beds is due to the fact that in the

marine environment there is abundant organic material and

reducing conditions prevail below the sediment-water inter-

face and the stable iron-bearing phase is pyrite (FeS2). This is a

consequence of bacterial activity which results in marine

sulfate reduction and the destruction of detrital iron oxides.

The process may be summarized using the following equations

in which organic material is given the general formula CH2O.

Initially sulfate reduction results in the formation of bicarbo-

nate and hydrogen sulfide:

2CH2O +

2HCO7 +

+

(Eq. 5)

This followed by the reduction of iron (Fe'"''-»Fe^"'") and

the combination of ferrous ion, initially as an intermediate

phase such as mackinawite (FeSo.9) or greigite (Fe3S4) and

subsequently as pyrite as shown in the reaction:

FeOOH + 2HS- -^ FeS2 + H2O

(Eq. 6)

When organic productivity is very low or the rate of

sedimentation is very slow the organic material may be

completely destroyed and oxidizing conditions (the Eh fence)

migrates downward through the sediment column. Under

these conditions detrital iron oxides remain stable and further

hematite may be produced byequation 1. This is the

mechanism by which deep marine red clays and other pelagic

red beds form (Froelich etai, 1979; see Oceanic Sediments).

Paleomagnetism of red beds

Red beds have long been a source of paleomagnetic data since

they have a very stable natural remanent magnetization

(NRM). The magnetization is carried by hematite due to its

intrinsic spin-canted antiferromagnetism. In some red beds the

ferrimagnetic magnetite Fe3O4 is also present but typically

this is only found in younger (Mesozoic and Tertiary)

sections. There has been much debate regarding the validity

of paleomagnetic data from red beds; clearly for detailed

paleomagnetic analysis the remanenee must have been

acquired at, or shortly after, deposition. This mechanism is

REEFS

557

called depositional (DRM) or post-depositional remanent

magnetization (PDRM) and appears to be important in fine

grained sediments where magnetic oxides are small enough to

rotate into the ambient magnetic field prior to compaction.

Magnetizations of this type enable red beds to accurately

record the geomagnetic field and there have been many

magnetostratigraphic applications, particularly in dating, and

correlation of paleontologically-barren sequences (e.g., Baag

and Helsley, 1974; Johnson etal., 1982)

The growth of authigenic hematite in red beds results in the

formation of chemical remanent magnetization (CRM) and

frequently because of the protracted nature of mesodiagenesis

sucti magnetizations are multicomponent and complex (see

Turner, 1980 for a detailed discussion). In the future,

paleomagnetism will prove to be a valuable technique in

dating diagenetic events in red beds and will help resolve the

difficulties of distinguishing between different types of red bed

sequences.

Peter Turner

Walker, T.R., 1967, Formation of red beds in modern and ancient

deserts. Bulletin of the

Geologieal

Society of America, 78: 353-368.

Walker, T.R., Waugh, B., and Crone, A.J., 1978. Diagenesis in first

cycle desert alluvium of Cenozoic age, southwestern United States

and northwestern Mexico. Bulletin of the Geological Society of

America, 89: 19-32.

Cross-references

Colors of Sedimentary Rocks

Desert Sedimentary Environments

Diagenesis

Magnetic Properties of Sediments

Maturation, Organic

Oceanic Sediments

Rivers and Alluvial Fans

Sands, Gravels, and their Lithified Equivalents

Weathering, Soils, and Paleosols

REEFS

Bibliography

Baag, C., and Helsley, C.E., 1974. Evidence for penecontemporeneous

magnetization ofthe Moenkopi formation. Journal of Geophysieal

Research, 79: 3308-3320.

Berner, R.A., 1969. Goethite stability and origin of red beds. Geochi-

micaet Cosmochimica Acta, 35: 267-273.

Folk, R.L., 1976. Reddening of desert sands: Simpson Desert, NT.,

Australia. Journalof Sedimentary Petrology, 46: 604-615.

Froelich, P.N. etal., 1979. Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic

sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: suboxic diagenesis.

Geochimicaet Cosmochimica Acta, 43: 1075-1090.

Goddard, E.N., 1951. Rock Color Chart. Geological Society of

America.

Johnson, S.A., Glover, B.W., and Turner, P., 1997. Multiphase

reddening and weathering events in Upper Carboniferous red beds

from the English West Midlands. Journal ofthe Geological Society of

London, t54: 735-745.

Johnson, N., Opdyke, N.D., Johnson, G.D., Lindsay, E.H., and

Tahirkheli, R.A.K., 1982. The paleomagnetism of the Middle

Siwalik formations of Northern Pakistan.

Paleogeography,

Paleocti-

matology Paleoecology, 37: 43-62.

Hansley, P.L., and Spirakis, C.S., 1992. Organic-matter diagenesis as

the key to a unifying theory for the genesis of tabular Uranium-

Vanadium deposits in the Morrison formation—Colorado Plateau.

Bulletin of the Society of Economic Geologists, 87: 352-365.

Krynine, P.D., 1950. Petrology, stratigraphy, and origin of the Triassic

sedimentary rocks of Connecticut. Bulletin ofthe Conneeticut Geol-

ogy and Natural History Survey, 73: 239p.

Langmuir, D., 1971. Particle size effect on the reaction Goe-

thite = Hematite + Water. Ameriean Journal of Science, 27t: 147-

156.

Mlicke, A., 1994. Part I. Postdiagenetic ferruginization of sedimentary

rocks (sandstones, oolitic ironstones, kaolins and bauxites)—

including a comparative study of the reddening of red beds. pp.

361-395,

In

Wolf,

K.H., and Chilingarian, G.V. (eds.), Diagenesis.

IV. Developments in Sedimentology, 51, Elsevier.

Rose, A.W., 1976. The effect of cuprous chloride complexes in the

origin of red-bed copper and related deposits. Economic Geology,

71:

1036-1048.

Sehwertmann, U., and Taylor, R.M., 1989. Iron oxides, pp. 379-438.

In Dixon, J.B., and Weed, S.B. (eds.). Minerals in Soil Environ-

ments. Soil Science Society of America.

Turner, P., 1980. Continental Red Beds. Elsevier.

Van Houten, F.B., 1961. Climatic significance of red beds, ln Nairn,

A.E. M. (ed.) Descriptive Paleoclimatology. Interscience Publishers

pp.

89-139.

Van Houten, F.B., 1973. Origin of red beds: a review—1961-1972.

Annual Review Earth and Planetary Seiences, t:

39-61.

Definitions and classifications

While originally defined by mariners as any shallow and hard

submarine structure potentially hazardous to vessels, the term

reef is restricted in earth sciences to mean laterally confined

carbonate bodies built by sessile benthic aquatic organisms. This

definition is wide enough to include reef structures of all ages,

yet precise enough to identify reefs as a recurring biological

phenomenon.

Another common definition restricts reefs to rigid, wave-

resistant biogenic structures with a significant syndepositional

relief and composed mainly of in-situ framework builders.

These attributes are often difficult to demonstrate in the fossil

record and should not be included in a geologic reef definition.

Moreover, even Holocene coral reefs often are internally

composed of reworked framework and bioclastic debris

(Hubbard et al., 1998) rather than consisting of an in-situ

framework.

Reefs are unique sedimentary systems because they sig-

nificantly modify the environment and structure their own

habitat. Shallow water reefs are protectors of tropical coasts

and stabilize platform margins. Reefs and their sand- to

boulder-sized debris form important hydrocarbon reservoirs.

The most widely used reef classifications focus on environ-

ment, geometry, and composition. For modern coral reefs,

Charles Darwin (1842) recognized fringing reefs, barrier reefs,

and atolls. He identified these environmental reef types as

belonging to a genetic sequence linked to subsidence history. A

fringing reef grows along the shore. With subsidence and

continued reef growth, lagoonal sediments fill the space

between the former shore and the reef becomes a barrier

reef.

If all preexisting land is submerged and only the reef and

lagoonal sediments remain, the reef will eventually form an

atoll. Barrier reefs and atolls exhibit a pronounced facies

zonation including (from lagoon to open ocean): back

reef,

reef flat, reef crest, reef front, and fore

reef.

Darwin's model,

although still valid today and often applicable to the fossil

record, must be broadened to include other environmental reef

types with or without modern counterparts. Patch reefs

(equivalent to platform reefs) were common throughout the

geological record. They are isolated reef structures mostly in

558 RLEIS

lagoonai settings, on carbonate platforms, or in epeiric

seaways. Reefs growing on submarine ramps and slopes are

rare today but were common in the past.

Geologists traditionally emphasize geometrical reef attri-

butes subdividing bioherms and biostromcs. A bioherm is a

mound-shaped structure, while a biostromc is a roughly

tabular structure without a significant syndepositional

relief.

The term bioherm is roughly equivalent to ecologic reef or

buildup, and

hio.s!rome

roughly agrees with a stratigraphic reef

(Dunham, 1970). Other common geometrical terms in reef

classification include banks (tabular structures similar to

biostromes but mostly micritic in composition) and pinnacle

reefs (nearly cylindrical isolated structures often surrounded

by basina! sediments). Terms such as ball, dish, haystack,

kalyptra. mamelon. spread-eagle, and spruce describe the

length/width ratio and overall shape of reef bodies in more

detail.

A eompositiona! classification of reefs is usually based on

three principal cotiiponents: skeletons, carbonate matrix, and

carbonate cement. Framework reefs, reef mounds, and mud

mounds are identified. A framework reef consists of skeletal

organisEiis in mutual contact. Skeletal organisms range fVom

calcified microbes to complex metazoans and framework.

Reef tnoutids consist of approximately equal proportions of

skeletal organisms and a matrix of earbonate mud and

marine cement; they appear to be matrix-supported. A mud

mound is dominated by earbonate mud and marine cement,

whereas skeletal framework is almost absent. The origin of

micritc and marine cement in reet~s is continuously disputed

and should therefore not be included in the reef dethiition. If

microbes are identified in micrite-rich mounds the term

microbial mound can be applied. Evidence for the both active

and passive microbial participation in micrite production is

increasing, even \u mounds without obvious stromatolitie or

thrombolitic structures (Riding, 2000). Common features of

many ancient reefs are large volumes of marine cement often in

the form of Stromatactis

(q.

v.).

Additional compositional

attributes used to classify reefs include the dominant biota

{e.g.. coral reef or sponge reef), the growth forms and

constructional role of reef builders, and the density of

framework.

Complex reef classifications combining constructional,

compositional, and genetic attributes have been published

(Insalaco. 1998). but their utilization is limited because genetic

interpretations, often changing with scientific views, are

intrinsic to the classification. Descriptive geometrical and

compositional classifications should be preferred in the study

of ancient reefs.

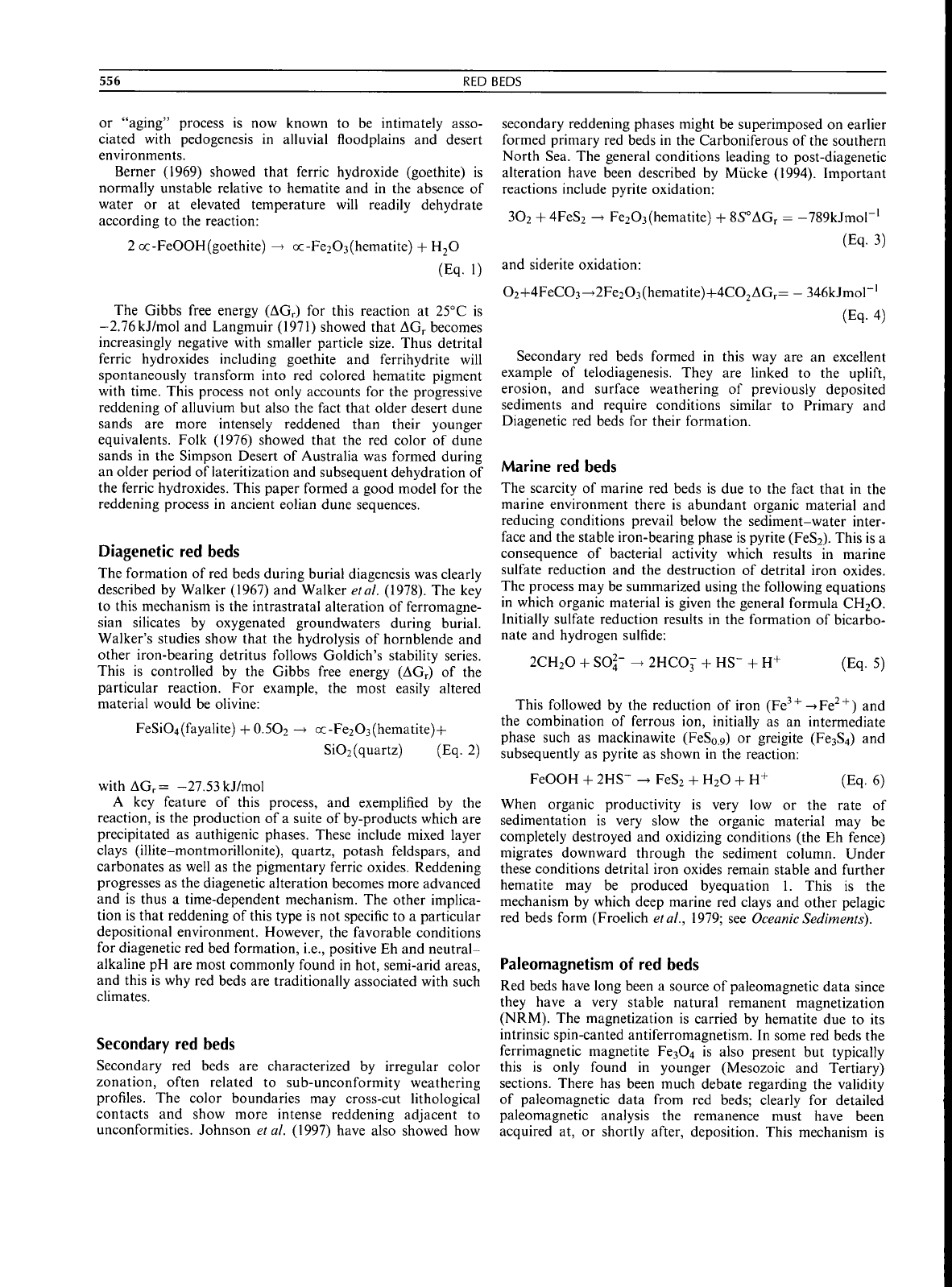

Reef builders

Reef builders are organisms that contribute to reef growth

either directly by the accumulation of their skeletal material or

by their metabolic activity. Cyanobacteria and other bacteria,

microalgae. and fungi represent the microbial consortium that

played a substantial role in reef-building throughout the

Proterozoic and Phanerozoic. The functional role of microbes

in reef-building is to trap and bind sediment, and to induce

carbonate precipitation (Reitner and Ncuweitcr, 1995). Micro-

bial crusts are often important to provide physical strength to

a reef and if possessing external calcified walls microbes could

play a substantial role in framework construction. Calcareous

algae have been notable reef builders throughout the

Phanerozoic and became especially important when global

climate was deteriorating (Kiessling, 2001).

The most important sessile invertebrate animals aeting as

reef builders are sponges and corals. Although coralline

sponges almost exclusively live in reef caves today, where they

are reef dwellers rather than builders, various sponge groups

such as archacocyaths, stromatoporoids. pharetronids, chae-

tetids.

and lithistids were very important reef builders in

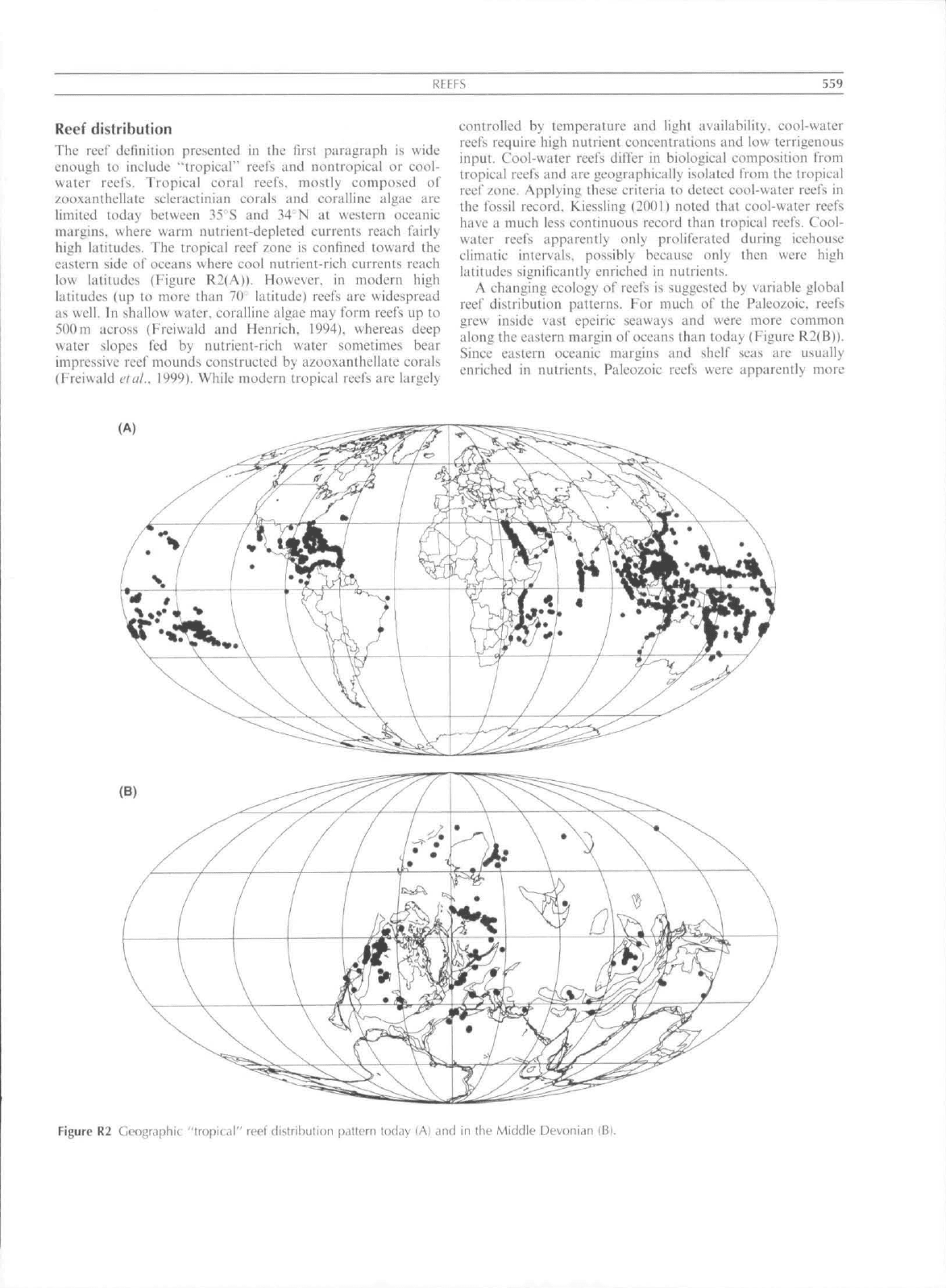

particular Phanerozoic periods (Figure RI). The great

dominance of coral reefs in modern tropical seas has led to

an almost synonymous treatment of coral reefs and reefs in

general. Yet although corals -Tabulata and Rugosa in the

Paleozoic. Scleractinia in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic were

important reef builders f>om the Upper Ordovician until

today, it is only in the Mesozoic that coral reefs became

predominant (Figure Rl). Even in the Mesozoie. bivalves as

reef builders, most notably the rudists in the Cretaceous,

occasionally outnumbered eorals. The great success of

scleractinian corals in reef-building is related to the efficient

symbiosis with unicellular algae (zooxanthellae). which permit

corals to grow rapidly in nutrient-depleted waters. Other

Phanerozoic reef builders were bryozoans and occasionally

brachiopods, pelmatozoans, and worms.

Time

,Ma)

1 O

Ng

J _

T_

c

—

_ • Microbial reefs

P • Algal reefs

•

Tubiphytes

reefs

ffl Coralline sponge reefs

£3 Siliceoussponge reefs

D Coralreefs

B Bivalve reefs

[3 Bryozoan reefs

B Worm reefs

• Others

Number of reefs

Figure Rl Relative anri absolute abundance of Phanerozoic biolic reef

types.

Time slices represent siipersequences as defined in Kiessling

L

Rrrrs

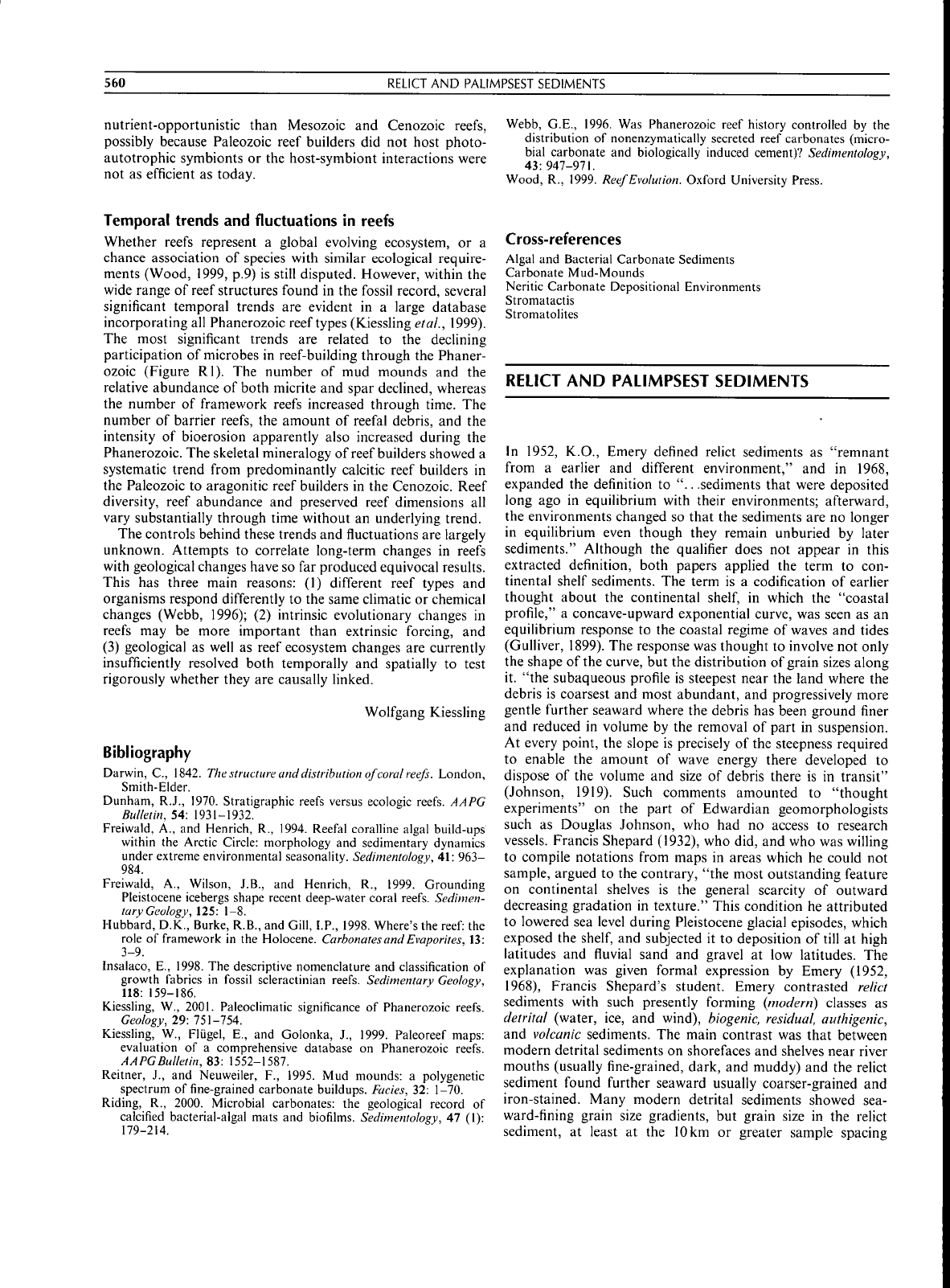

Reef distribution

The reef definition presented in the first paragraph is wide

enough to include "tropical" reefs and nontropical or

cool-

water reefs. Tropical coral reefs, mostly composed of

zooxanthellate scleractinian corals and coralline algae are

limited today between 35"S and 34' N at western oceanic

margins, where warm nutrient-depleted eurrents reach fairly

high latitudes. The tropical reef zone is confined toward the

eastern side of oceans where cool nutrient-rich currents reach

low latitudes (Figure R2(A)). However, in modern high

latitudes (tip to more than 70 latitude) reefs arc widespread

as

well.

In shallow water, coralline algae may form reefs up to

500m across {Frciwald and Henrich, 1994), whereas deep

water slopes fed by nutrient-rich water sometimes bear

impressive reef mounds constructed by azooxanthellate corals

(Freiwaid

craf.

1999). While modern tropical reefs are largely

controlled by temperature and light availability, cool-water

reefs require high nutrient concentrations and low terrigenous

input. Cool-water reefs dilTcr in biological cotnposition from

tropical reefs and are geographically isolated from the tropical

reef

zone.

Applying these criteria to deteet cool-water reefs in

the fossil record, Kiessling (2001) noted that cool-water reefs

have a tnuch less continuous record than tropical reefs. Cool-

water reefs apparently only proliferated during icehotise

climatic intervals, possibly beeause only then were high

latitudes significantly enriched in nutrients.

A changing ecology of reefs is suggested by variable global

reef distribution patterns. For much of the Paleozoic, reefs

grew inside vast epeiric seaways and were more eommon

along the eastern margin of oceans than today (Figure R2(B)).

Since eastern oceanic margins and shelf .seas are usually

enriched in nutrients. Paleozoic reefs were apparently more

Figure R2 Geographic "tropical" reef distribution pattern today lA) and in the Middle Devonian (B).

560

RELICT AND PALIMPSEST SEDIMENTS

nutrient-opportunistic than Mesozoic and Cenozoic reefs,

possibly because Paleozoic reef builders did not host photo-

autotrophic symbionts or the host-symbiont interactions were

not as efficient as today.

Webb, G.E., 1996. Was Phanerozoic reef history controlled by the

distribution of nonenzymatically secreted reef carbonates (micro-

bial carbonate and biologically induced cement)? Sedimentology,

43:

947-971.

Wood, R., 1999. Reef Evolution. Oxford University Press.

Temporal trends and fluctuations in reefs

Whether reefs represent a global evolving ecosystem, or a

chance association of species with simitar ecotogicat require-

ments (Wood, 1999, p.9) is still disputed. However, within the

wide range of reef structures found in the fossil record, several

significant temporal trends are evident in a large database

incorporating all Phanerozoic reef types (Kiessling etal., 1999).

The most significant trends are related to the declining

participation of microbes in reef-building through the Phaner-

ozoic (Figure Rl). The number of mud mounds and the

relative abundance of both micrite and spar declined, whereas

the number of framework reefs increased through time. The

number of barrier reefs, the amount of reefal debris, and the

intensity of bioerosion apparently also increased during the

Phanerozoic. The skeletal mineralogy of reef builders showed a

systematic trend from predominantly calcitic reef builders in

the Paleozoic to aragonitic reef builders in the Cenozoic. Reef

diversity, reef abundance and preserved reef dimensions all

vary substantially through time without an underlying trend.

The controls behind these trends and fluctuations are largely

unknown. Attempts to correlate long-term changes in reefs

with geological changes have so far produced equivocal results.

This has three main reasons: (1) different reef types and

organisms respond differently to the same climatic or chemical

changes (Webb, 1996); (2) intrinsic evolutionary changes in

reefs may be more important than extrinsic forcing, and

(3) geological as well as reef ecosystem changes are currently

insufficiently resolved both temporally and spatially to test

rigorously whether they are causally linked.

Wolfgang Kiessling

Bibliography

Darwin, C, 1842. The strueture and distribution of

coral

reefs.

London,

Smith-Elder.

Dunham, R.J., 1970. Stratigraphic reefs versus ecologic reefs. AAPG

Bulletin, 54: 1931-1932.

Freiwaid, A., and Henrich, R., 1994. Reefal coralline algal build-ups

within the Arctic Circle: morphology and sedimentary dynamics

under extreme environmental seasonality. Sedimentology, 41: 963-

984.

Freiwaid, A., Wilson, J.B., and Henrieh, R., 1999. Grounding

Pleistocene icebergs shape recent deep-water coral reefs. Sedimen-

tary

Geology,

125: 1-8.

Hubbard, D.K., Burke, R.B., and Gill, I.P., 1998. Where's the

reef:

the

role of framework in the Holocene. Carbonates and

Evaporites,

13:

3-9.

Insalaco, E., 1998. The descriptive nomenclature and classification of

growth fabrics in fossil scleractinian reefs. Sedimentary Geology,

118:

159-186.

Kiessling, W., 2001. Paleoclimatic significance of Phanerozoic reefs.

Geology, 29: 751-754.

Kiessling, W., Flugel, E., and Golonka, J., 1999. Paleoreef maps:

evaluation of a comprehensive database on Phanerozoic reefs.

AAPG Bulletin, 83: 1552-1587.

Reitner, J., and Neuweiler, F., 1995. Mud mounds: a polygenetic

spectrum of fine-grained carbonate buildups. Facies, 32: 1-70.

Riding, R., 2000. Microbial carbonates: the geological record of

calcified bacterial-algal mats and biofilms. Sedimentology, 47 (I):

179-214,

Cross-references

Algal and Bacterial Carbonate Sediments

Carbonate Mud-Mounds

Neritic Carbonate Depositional Environments

Stromatactis

Stromatolites

RELICT AND PALIMPSEST SEDIMENTS

In 1952, K.O., Emery defined relict sediments as "remnant

from a earlier and different environment," and in 1968,

expanded the definition to ".. .sediments that were deposited

long ago in equilibrium with their environments; afterward,

the environments changed so that the sediments are no longer

in equilibrium even though they remain unburied by later

sediments." Although the qualifier does not appear in this

extracted definition, both papers applied the term to con-

tinental shelf sediments. The term is a codification of earlier

thought about the continental

shelf,

in which the "coastal

profile," a concave-upward exponential curve, was seen as an

equilibrium response to the coastal regime of waves and tides

(Gulliver, 1899). The response was thought to involve not only

the shape ofthe curve, but the distribution of grain sizes along

it. "the subaqueous profile is steepest near the land where the

debris is coarsest and most abundant, and progressively more

gentle further seaward where the debris has been ground finer

and reduced in volume by the removal of part in suspension.

At every point, the slope is precisely of the steepness required

to enable the amount of wave energy there developed to

dispose of the volume and size of debris there is in transit"

(Johnson, 1919). Such comments amounted to "thought

experiments" on the part of Edwardian geomorphologists

such as Douglas Johnson, who had no access to research

vessels. Francis Shepard (1932), who did, and who was willing

to compile notations from maps in areas which he could not

sample, argued to the contrary, "the most outstanding feature

on continental shelves is the general scarcity of outward

decreasing gradation in texture." This condition he attributed

to lowered sea level during Pleistocene glacial episodes, which

exposed the

shelf,

and subjected it to deposition of till at high

latitudes and fluvial sand and gravel at low latitudes. The

explanation was given formal expression by Emery (1952,

1968),

Francis Shepard's student. Emery contrasted relict

sediments with such presently forming {modern) classes as

detritai (water, ice, and wind), biogenic, residual, authigenic,

and volcanic sediments. The main contrast was that between

modern detrital sediments on shorefaces and shelves near river

mouths (usually fine-grained, dark, and muddy) and the relict

sediment found further seaward usually coarser-grained and

iron-stained. Many modern detrital sediments showed sea-

ward-fining grain size gradients, but grain size in the relict

sediment, at least at the

10

km or greater sample spacing

RELIEF PEELS

561

characteristic of the early surveys, seemed to vary in a random

manner.

During the period of rapid geological exploration of

continental shelves in the 1970s and 1980, the concepts of

modern, detrital, and relict sediment filled a need, and relict

sediments were described from many of the world's shelves

(Slatt and Lew, 1973; Herzer, 1981; Barrie etal., 1984; Shen,

1985).

More thought was given to the issue. Swift etal. (1971)

described a palimpsest sediment as "one which exhibits

petrographic attributes of an earlier depositional environment

and in addition of a later [modern] environment." McManus

(1975) distinguished between in situ relict and palimpsest

deposits on one hand, and freshly sedimented materials which

might be comptetely derived from reworking of the bottom

{proteric sediments), partially so derived {amphoterie sedi-

ments),

or might be entirely new to the environment {neoteric

sediments). At the same time, advances in automating textural

analysis (Ehrlich and Weinberg, 1970) lead to quantitative

criteria for applying these terms (Brown etal., 1980; Mazzullo

etal., 1983).

A persistent problem in the application of "relict" and

related terms to the interpretation of shelf sediment has been

the lack of quantitative and analytical understanding of the

equilibrium from which the relict sediment is supposed to be a

departure. While Ehrlich and Weinberg (1970) and their co-

workers achieved considerable success in distinguishing among

sources and agents of sediment input on continental shelves

by means of grain shape analysis, the progression of the

sediment toward textural maturity defined by it is not an

equilibrium concept. The equilibrium parameter implicit in the

early discussions (Emery, 1952, 1958) is grain size. Grain size

frequency distributions have long been seen as equilibrium

responses to the hydraulic regime (e.g., Johnson, 1919)

however, the problem is a complex one, encompassing

aggregate behavior at a range of spatial scales. Not only must

grain size frequency distributions of individual bottom samples

be understood in terms of boundary layer fluid dynamics (e.g.,

Sengupta etal., 1991), but regional patterns of grain size must

be understood in terms of advective-diffusive grain transport

(Clarke etal., 1983; Swift etal., 1986).

Donald J.P. Swift

Gulliver, F., 1899. Shoreline topography. Ameriean Academy of Arts

and Scienees

Proceedings.

34: 151-258.

Herzer, R.H., 1981. Late Quaternary Stratigraphy and Sedimentation of

the Canterbury Continental Shelf New Zealand. New Zealand

Oceanographic Institute Memoir, 899.

Johnson, D.W., 1919. Shore Processes and Shoreline Development.

Columbia University Press (Hafner Facsimile edition, 1952).

Mazullo, J., Ehrlich, R., and Hemming, M.A., 1983. Provenance and

areal distribution of Late Pleistocene and Holocene quartz sand on

the southern New England continental

shelf.

Journal of Sedimen-

tary Petrology, SA: 1135-1348.

McManus, D.A., 1975. Modern versus relict sediment on the

continental

shelf.

Geological Society of Ameriea Bulletin, 86:

1154-1160.

Sengupta, S., Ghosh, J.K., and Mazumder, B.S., 1991. Experimental-

theoretical approaeh to the interpretation of grain size frequency

distributions. In Syvitski, P.M. (ed.). Principles, Methods, and

Application of

Particle

Size Analysis. Cambridge University Press,

pp,

264-280.

Shepard, F.P,, 1932. Sediments ofthe continental shelves. Geological

Societyof America Bulletin, 43: 1017-1040.

Shen Huati, 1985. Age and genetic model of relict sediments on the

East China Sea shelf Haiyang Xuebao (Acta Oceanologica Sinica),

7:

67-77.

Slatt, R., and Lew, A.B., 1973. Provenance of Quaternary sediments

on the Labrador continental shelf and slope. Journal of Sedimen-

tary Petrology, Ai: 1054-1060.

Swift, D.J.P., Stanley, D.J, and Curray, J.R., 1971. Relict sediments of

continental shelves: a reconsideration. Journal of Geology, 16:

221-250.

Swift, D.J.P., Thorne, J.A., and Oertel, G.F., 1986. Fluid process and

sea floor response on a storm dominated

shelf:

Middle Atlantie

shelf of North Ameriea. Part II: response of the shelf floor. In

Knight, R.J., and Me Lean, J.R. (eds.). Shelf Sands And Sandstone

Reservoirs. Canadian Soeiety of Petroleum Geologists Memoir,

Volume 11, pp.

191-211.

Cross-references

Diffusion, Turbulent

Grain Size and Shape

Offshore Sands

RELIEF PEELS

Bibliography

Barrie, J.V., Lewis, C.F.M., Fader, G.B., and King, L.H., 1984.

Seabed processes on the northeastern Grand Banks of Newfound-

land: modern reworking of relict sediments. Marine Geology, 57:

209-227.

Brown, P.J., Ehrlich, R., and Colquehoun, D., 1980. Origin of pattern

of quartz sand types on the southeastern United States continental

shelf and implications on contemporary shelf sedimentation:

Fourier grain shape analysis. Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology,

50:

1095-1100.

Clarke, T.L., Swift, D.J.P., and Young, R.A., 1983. A stoehastie

modeling approach to the fine sediment budget of the New York

Bight. Journal

Geophysical

Research, 88: 9653-9660.

Ehrlich, R., and Weinberg, B., 1970. An exact method for the

eharaeterization of grain shape. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology,

40:

205-212.

Emery, K.O., 1952. Continental shelf sediments off southern

California.

Geological

Society of America, 63: 1105-11108.

Emery, K.O., 1968. Relict sediments on continental shelves of the

world. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 52:

445-464.

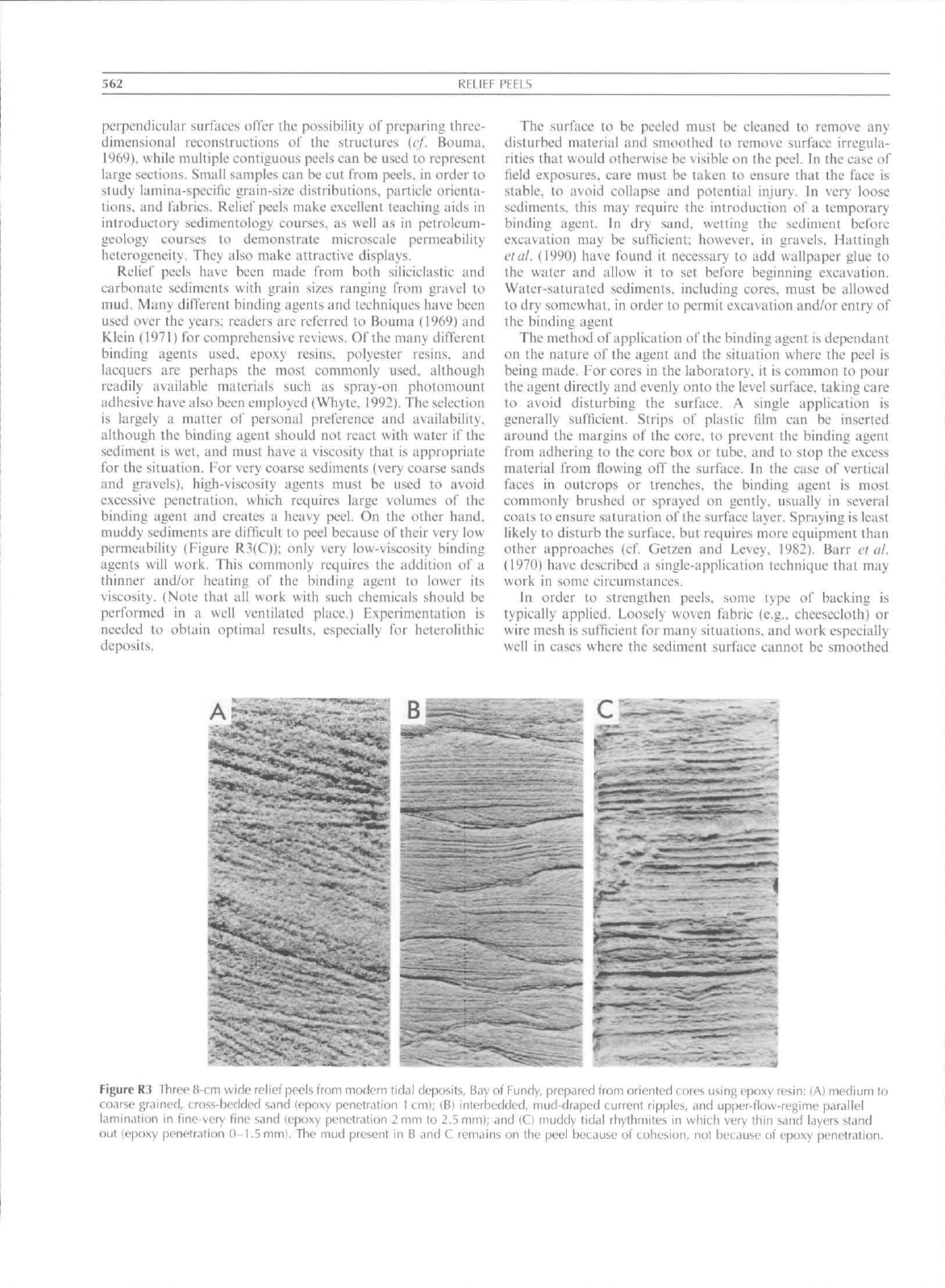

Relief peels are produced by impregnating a thin, surficial

layer of unconsolidated, granular sediment. Because of spatial

differences in the porosity and permeability, the binding agent

penetrates to different depths, producing relief on the peel's

surface (Figure R3). The differences in porosity and perme-

ability are themselves determined by subtle differences in grain

size,

sorting, and packing that are created during deposition of

the sediment and/or during any post-depositional bioturba-

tion, deformation, or incipient diagenesis. Such peels have

been used extensively since the early 1950s to study the

physical and biogenic structures present in modern deposits

and unconsolidated older sediments. Commonly, the impreg-

nation process yields a more detailed record of those structures

than can be seen in the original core or exposure. The

permanence of the peel allows for more thorougii study than

would be possible otherwise, and photography can be done

under controlled lighting conditions, providing better doc-

umentation of the structures than might be possible in the

field. Relief peels obtained from two or more, mutually

562

RELIEF PEELS

perpendicular surfaces offer the possibility of preparing three-

dimensional reconstructions of the structures {ef Bouma,

1969).

while multiple contiguous peels can be used to represent

large sections. Small samples can be cut from peels, in order to

study tamina-spccihc grain-size distributions, particle orienta-

tions,

and fabrics. Relief peels make exeellent teaching aids in

introductory sedimentology courses, as well as in petroleum-

geology courses to demonstrate microscale permeability

heterogeneity. They also make attractive displays.

Relief peels have been made from both silicielastic and

carbonate sediments with grain sizes ranging from gravel to

mud. Many different binding agents and techniques have been

used over the years; readers arc referred to Bouma (1969) and

Klein (1971) for comprehensive reviews. Ofthe many different

binding agents used, cpoxy resins, polyester resins, and

lacquers are perhaps the most commonly used, although

readily available materials such as spray-on photoniount

adhesive have also been employed (Whyte. 1992). The selection

is largely a matter of personal preference and availability,

although the binding agent should not react with water if the

sediment is wet. and must have a viscosity that is appropriate

for the situation, f-or very eoarse sediments (very coarse sands

and gravels), high-viscosity agents must be used to avoid

e.xcessive penetration, which requires large volumes of the

binding agent and creates a heavy peel. On the other hand,

muddy sediments are difficult to peel because of their very low

permeability (Figure R3(C)); only very low-viscosity binding

agents will work. This commonly requires the addition of a

thinner and/or heating of the binding agent to lower its

viscosity. (Note that all work with such chemicals should be

performed in a well ventilated place.) E.xperimentation is

needed to obtain optimal results, especially for heterolithic

deposits.

The surface to be peeled must be cleaned to remove any

disturbed material and smoothed to remove surface irregula-

rities that would otherwise be visible on the peel. In the case of

field exposures, eare must be taken to ensure that the face is

stable, lo avoid collapse and potential injury. In very loose

sediments, this may require the introduction of a temporary

binding agent. In dry sand, wetting the sedinient before

excavation may be sufficient; however, in gravels. Hattingh

elal. (1990) have found it necessary to add wallpaper glue to

the water and allow it to set before beginning excavation.

Water-saturated sediments, including cores, must be allowed

to dry somewhat, in order to permit excavation and/or entry of

the binding agent

The method of application of the binding agent is dependant

on the nature ofthe agent and the situation where the peel is

being made. For cores in the laboratory, it is coninion to pour

the agent directly and evenly onto the level surface, taking care

to avoid disturbing the surface. A single application is

generally sufficient. Strips of plastic film can be inserted

around the margins of the core, to prevent the binding agent

from adhering to the core box or tube, and to stop the excess

material from flowing off the surface. In the case of vertical

faces in outcrops or trenches, the binding agent is most

commonly brushed or sprayed on gently, usually in several

coats to ensure saturation ofthe surface layer. Spraying is least

likely to disturb the surface, but requires more equipment than

other approaches (cf. Getzen and Levey. 1982). Barr e! al.

(1970) have described a single-application technique that may

work in some circumstances.

In order to strengthen peels, some type of backing is

typically applied. Loosely woven labric (e.g.. cheesecloth) or

wire mesh is sufficient for many situations, and work especially

well in cases where the sediment surface cannot be smoothed

Figure R3 Three 8-cm wide

relJet^

peels from modern tidal deposits, Bay of Eundy, prep.ired from oriented cores using epoxy resin: lA) medium to

coarse grained, cross-bedded sand (epoxy penetralion

1

cm); (Bl interbedded, mud-draped current ripples, and uf^per-flovv-regime parallel

lamination in fine-very fine sand (epoxy penetration 2 mm (o 2.5 mm); and (Ci muddy tidal rhylhmites in which very thin sand layers stand

out {epoxy penetration 0-1.5 mm). The mud present in B .md C remains on the peel because of cohesion, nol because of epoxy penetration.

AND AMBER IN SFDIMFNTS

563

completely (e.g.. in the case of gravels). More rigid backings

such as masonite, plexiglass, or stiff card are also used. They

tnay be applied during the peel-making process, or after the

peel has been removed. Any backing should be carefully

labeled with all relevant sample information, including any

orientation data.

i he peel must be left in place until the binding agent has set

sufficiently that the peel and the surface relief are eapable of

retaining their integrity. This may take several tens of minutes

to tnany hours depending on the binding agent used and the

temperature: heat lamps can be used, with caution, to speed

drying. Complete curing may take severai days. During this

time,

it may be necessary to weigh the peel down to prevent

warping. Once the binding agent has set completely, loose

sediment can be removed by brtishing and/or washing (unless

the binding agenl is soluble in water). A thin, transparent

coating may then be applied to protect the surface, if desired.

The peel is then ready for study; additional mounting may be

required for display purposes.

Robert W. Dalrymple

Bibliography

Biirr. J.L., Dinkchnaii, M.G., and Sandtisky. C.L.. 1970. Large epoxy

pcL'Is.

.hnirnalof Seditnetttary Petrology. 40: 445-449,

Bouma, A.H., 1469. Methods for the Study oj Seditnentary Structures.

New York: Wilcy-lntcrscicncc.

Cict/cn. R.T., and Levey, R.A.. 1982, Rigid-pccI technique of

preserving strticttircs in coarse-grained .sediments. Journal oj

Sediniettlary Pctrokigy. 52: 652-654.

H.ittingh, J.. Rust, I.C., and Reddering. J.S.V., 1990. A technique for

preserving structures in iiticonsolidated gravels in relief peels.

Journal of Sedimetitary

Petrology.

60: 626 627.

Klein. (ideV., 1971. Peels and inipicssions. In Carver, R.F, (cd.).

Procedures in Sedimetitary Petrologw Wiley-lnterscience, pp, 217

250.

Whyte. M,A,, 1992. The use of'"pliotoniouni" adhesive as a meditim

tor peels of unconsolidaled sediments. Jmirtutl of Sedittietitary

Petrology. 62: 741-742.

Cross-references

Bedding and Internal Structures

Biogenic Sedimentary Structures

I abric. Porosity, and PL-nticahilit\

(irain Si/e and Shape

Mudroeks

Weathering, Soils, and Paleosols

RESIN AND AMBER IN SEDIMENTS

Many plants produce resinous exudates in response to injury

or stress. These exudates. which serve to seal injuries and

discourage predators, are organic materials, often composed of

mixtures of semi-volatile and volatile organic compounds

know as tcrpenes. After exudation, these mixtures typically

harden into solid masses, either by evaporation of volatile

components and/or by polymerization. These masses are often

highly resistant to biological attack, and hence, tend to resist

degradation processes which break down other plant tissues.

For this reason, these materials often accumulate in developing

sediments and become part of the sedimentary record.

Resins are fairly common constituents of sediments derived

from terrestrial systems. They do not usually occur as massive

deposits, although in some eases signilicant concentrations are

known. The most famous of these is the very well-known

Eocene "Blue Earth" found in and around the Baltic region,

which is the source strata for Baltic ambers, which have been

known and eollected tor millennia. So-called "gem" quality

ambers, those that are clear and are most suitable for us in

ornamentations or artistic applications arc usually less

eommon than opaque samples, but in many instances opaque

samples are overlooked or discarded by prospectors and

collectors and hence these are not as common in collections as

they probably are in sediments. Not surprisingly, resinous

materials are commonly found in association with coals and

coatly shales, although in many of these settings resins may

exist only as finely dispersed particles which are identified by

microscopy on the basis of their optical properties.

Distribution

Resin-derived materials are both geographically and chron-

ologically widely distributed in the seditnentary record. The

oldest confirmed terpenoid ambers have been reported in

Triassic sediments, but optically-defined resinites are com-

monly reported in Carboniferous and Permian coals. The vast

majority of well-known ambers are found in sediments of

Cretaceous age or younger.

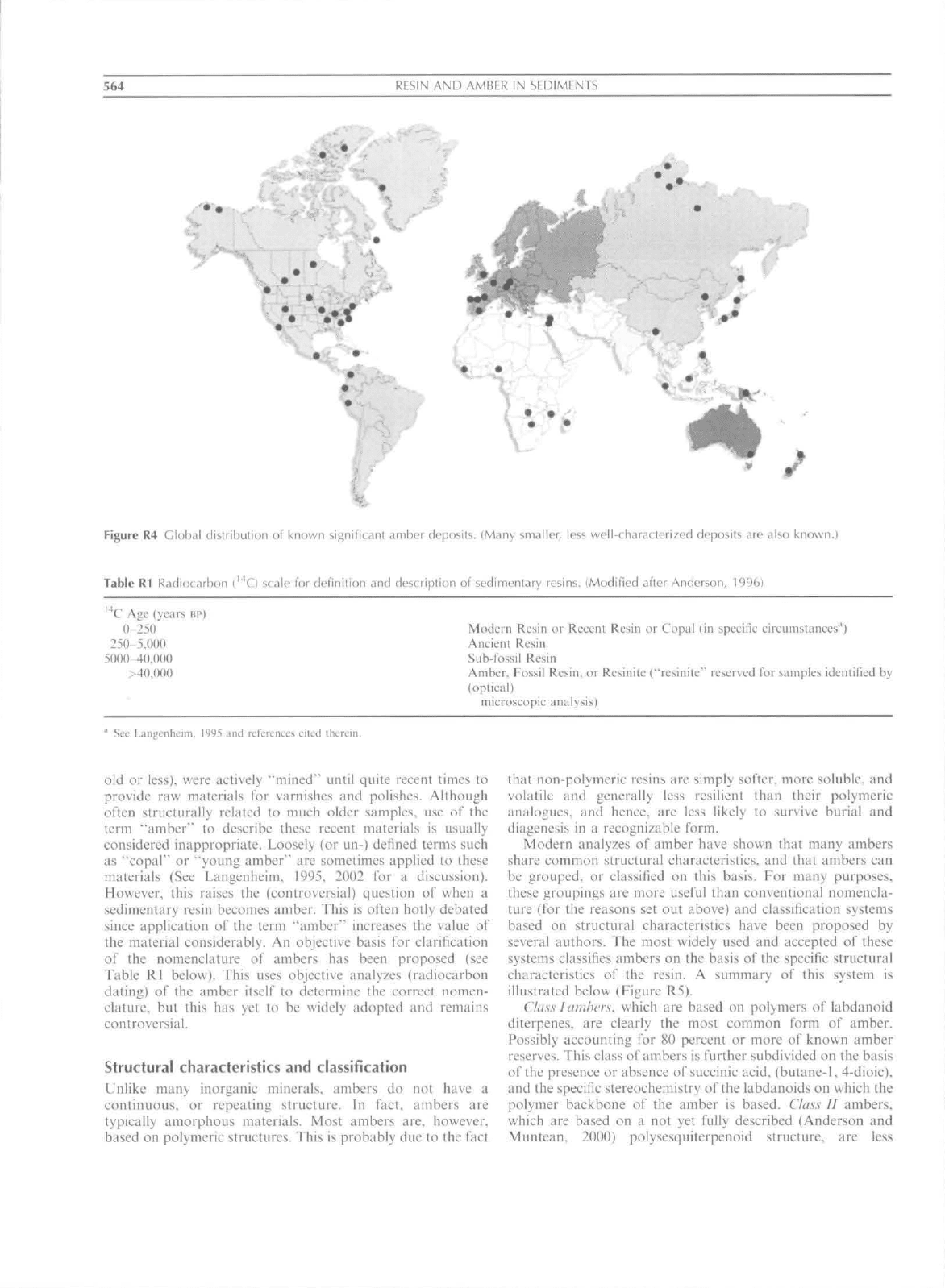

Ambers are known from every continent except Antarctica

tand probably exist there but have nol been observed). The

best known deposits are located in Europe and western Asia,

but extensive deposits are also known from the Caribbean

Basin (especially the Dominican Republic), South East Asia

and North America (Figure R4). Ambers are also known in

Africa and South America, but fewer deposits have been

described for these locales. This probably does not reflect a

greater absence of ambers in these regions, but rather the

political realities in many of the.se regions which tend to

discourage prospecting.

Terminology and nomenclature

The nomenclature of ambers is a mess. Historically, because

the appearance and to some extent ihe physical properties of

ambers vary significantly, many have been given informal

names based on the geographic origins or on the name of the

individual who first reported the existence of a particular

deposit. Hence, the literature is full of references to bumiite.

rumanite. beckeritc. glcssite. etc. ln reality, most of these

names are not particularly useful since they are not based on

any useful objective characteristic ofthe amber which would

allow a user to determine the relationship of samples from

different deposits. An exception to this is "succinite," the term

generally applied lo ambers from the Baltic region. This term

derives from the characteristic presence of succinic acid (also

sometimes known as amber acid) in ambers from this region.

Adding (o this eonfusion. use of the term "amber" can itself

be controversial when the age ofthe sample is in question or is

known to be modest. Because resins are continuously being

produced and deposited, recent, and modern deposits are well-

known. In fact in some places, these recent deposits, (which

often contain materials on the order of a few thousand years

564

RESIN AND AMBER IN SFDIMFNTS

Figure R4 Glnb,:il dislribulion of known signit'itdnl amber deposits. (Many sm.iller,

lesE.

well-tharatterized deposits are also known.)

Table Rl Radiocarixin {'"'O scale inr detinirinn <ind description of sedimenLiry resins. (Modified afler Anderson, 19961

'"*C Age (years

BP)

0 250 Modern Resin or Recent Rosin or Copal (in spccitic eireumsriinces'')

250

5,000

Ancieni Resin

50(K) 40.000 Sub-lossil Resin

>4().(K)n Amber. Fossil Resin, or Resinite ("resinile" reserved for samples identified by

(opliciil)

microscopic analysis)

•' Sec Langciihcim.

1995

anil rcfcrtnufs filtti therein.

old or less), were actively "mined" until quite recent times ro

provide raw materials Ibr varnishes and polishes. Although

often structurally related to much older samples, use of the

term "amber'" to describe these recent mitteriiils is usually

considered inappropriate. Loosely (or un-J defined lerms sueh

as "copal" or "young amber" arc sometimes applied to these

materials (See Langenheim. 1995, 2002 for a discussion).

However, this raises the (controversial) question of when a

sedimentary resin becomes amber. This is often hotly debated

since application of the term "amber" increases the value of

the material considerably. An objective basis tbr clarilication

of the nomenclature of ambers has been proposed (see

Table Rl below). This uses objective analyzes (radiocarbon

dating) of the amber itself to determine the eorrecl nomen-

clature, but this has yet to he widely adopted and remains

controversial.

Structural characteristics and classification

Unlike many inorganic minerals, ambers do not have a

continuous, or repealing structure. In fact, ambers are

typically amorphous materials. Most ambers are. however,

based on polymeric struetures. This is probably due to the fact

that non-polymeric resins arc simply softer, more soluble, and

volatile and generally less resilient than their polymeric

analogues, and hence, are less likely to survive burial and

diagenesis in a recognizable fbrm.

Modern analyzes of amber have shown that many ambers

share eommon structural characteristics, and that ambers ean

be grouped, or classified on this basis. For many purposes,

these groupings are more useful than eonventioniii nomencla-

ture (Ibr the reasons set out above) and classitication systems

based on structural characteristics have been proposed by

several authors. The most widely used and accepted of these

systems classifies ambers on the basis of the specific structural

characteristics of the resin. A summary of rhis sysrem is

illustrated below (Figure R5).

Class I ambers, which are based on polymers of labdanoJd

diterpenes. are clearly ihe most common fbrm of amber.

Possibly accounting tbr 80 percent or more of known amber

reserves. This class of ambers is further subdivided on the basis

of rhe presence or absence of succinic acid, (butane-1, 4-dioic),

and the specific stereochemistry of the labdanoids on which the

polymer backbone of the amber is based.

Cla.ss

II ambers,

which are based on a not yet fully described (Anderson and

Muntean. 2000) polysesquiterpenoid structure, are less