Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

KIVEKS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

575

both spatially, and temporally, and is therefore extremely

diClicuh to measure accurately, espeeially in large rivers. Bed-

load is mostly (but certainly not entirely) a function of the

highly variable shear stresses acting on the bed, and is often

estimated from average flow and sediment characteristics.

Beeause bed load is the eoarsest fraction and moves mostly

short distances during relatively int>equcnt, high magnitude

flows,

it is commonly the smallest proportion of transported

sediment (often <IO percent of the total load). It is therefore

sometimes ignored, however, this overlooks the importance of

bed-load in determining river form, as well as its contribution

to the stratigraphic record—in laterally migrating and accret-

ing systems sediment deposited within channels has an

especially high probability of being preserved. The eapaeiiy

ofa river to transport bed-load is usually limited, but few flows

reach their limit for transport of suspended

load,

the concen-

tration of which is largely controlled by the rate of supply.

Reliable relationships have been determined between

sedimentary structures, sediment size, and flow velocity (or

shear stress)

(see

Surface

Forms:

Sediment Flu.xe.s

and

Rales

(>/

Sedimenlaiion). Bed roughness ehanges in a complex but

predictable fashion with increasing velocity and sediment

transptjrt. It reaches a maximum with dune formation under

lower regime flow and antidune formation under upper

regime flow.

Sediment character has a profound influence on river style.

As a consequenee. Schumm (1960) developed a classification of

rivers based on bed

load,

mixed load and suspended load

systems, with width:depth ratios of >40. 10-40, and <10.

respectively. His approach has influenced later classifications

of rivers, floodplains, and stratigraphic sequenees.

Sediment deposition

Alluvium results from fluvial sedimentation. This takes place

for suspended or saltating sediment when the flow velocity

drops below that of the settling velocity (the velocity of a

parlicle falling through a eolumn of still water), and t\-)r bed

load when (low velocity drops below that maintaining sliding

or rolling of particles over the bed. When velocity wanes or

deereases locally within the channel or on the floodplain

surface, the coarsest fraetions are deposited first. As a result,

sediment sizes are sorted vertically, and laterally within the

total alluvial system. On laterally migrating meandering rivers,

upward fining successions within point bar and floodplain

deposits result from flow velocities that decline from near the

deepest part of channel (the thalweg) and adjacent point bar

(depositing gravel or eoarse sand), to the upper point bar,

convex bank, and floodplain surface (depositing fine sand and

mud).

In braided rivers, coarse braid bars characterize the

lowermost deposits, and with braid-channel, and braid-bar

migration or abandonment, overbank fines, and channel fills

characterize the uppermost deposits. Adjacent to laterally

stable channels, or on floodplains away from the zone of active

channels, floodplain strata broadly flue upward as each

sueeessive stratum makes the surface higher and less accessible

to overbank flooding. However, in detail sueh upward fining

successions are usually complex, exhibiting numerous size

variations, and reversals resulting from temporal and spatial

variations in llow conditions within individual floods and

between successive floods. Secondary currents are known to

play a major role in producing the broad spatial variations in

sedimentation in bends, bars, and floodplain scrolls, as well as

in innumerable smaller flow structures.

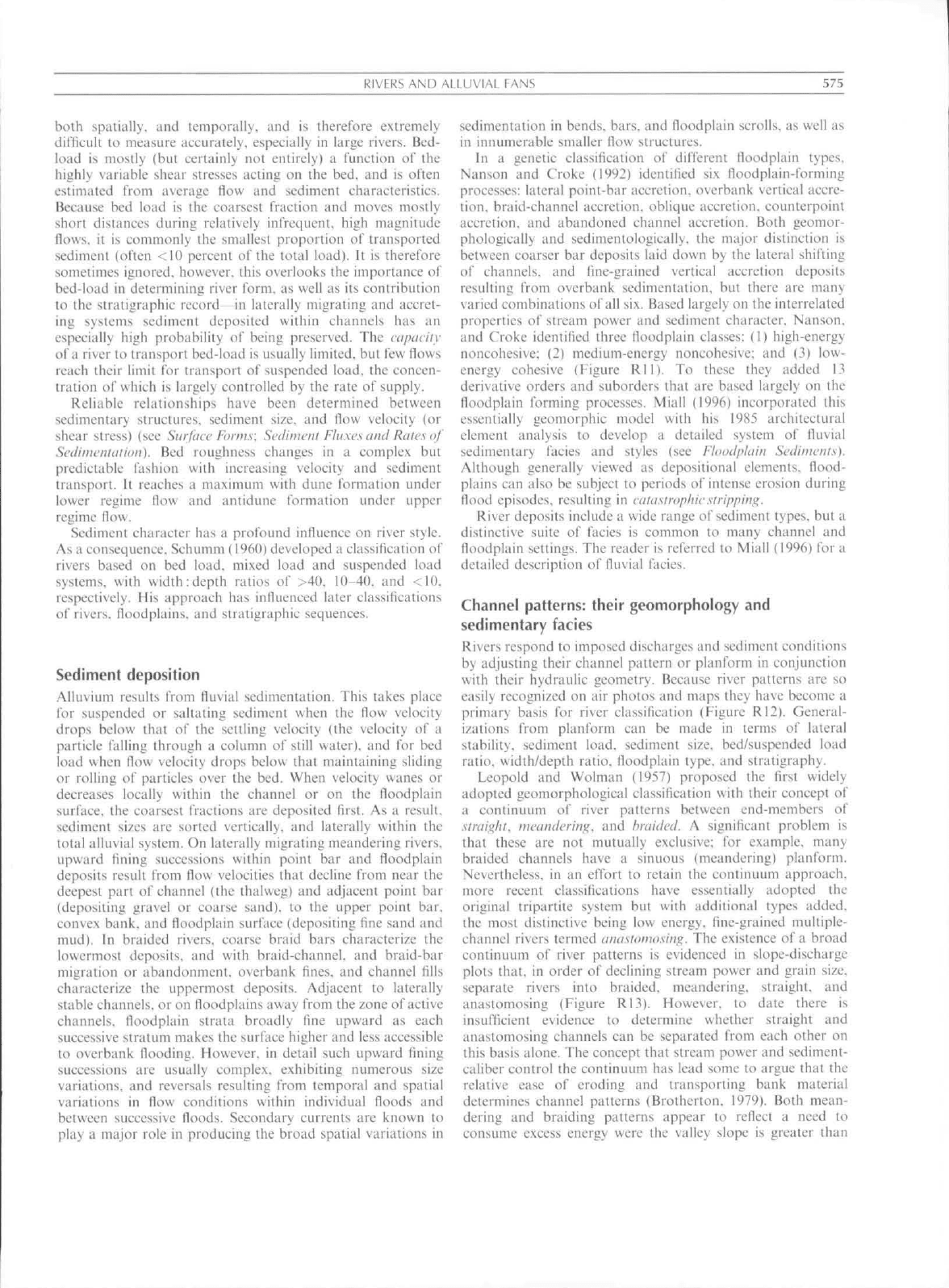

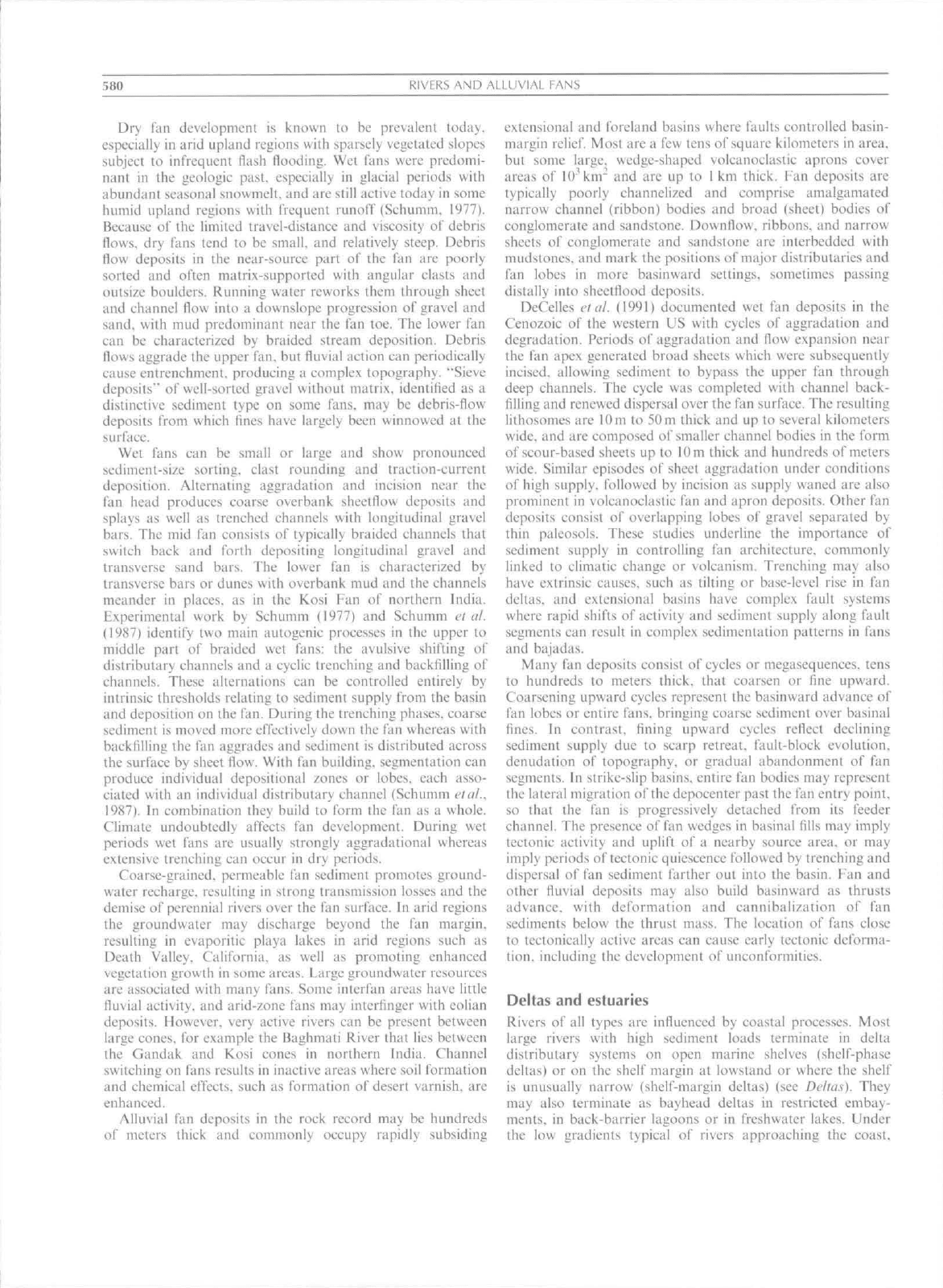

ln a genetic classiflcation of different Hoodplain types,

Nanson and Croke (1992) identified six floodplain-forming

processes: lateral point-bar aeeretion, overbank vertical accre-

tion,

braid-channel accretion, oblique accretion, counterpoint

accretion,

and abandoned channel accretion. Both geomor-

phologically and sedinientologicaily, the major distinction is

between coarser bar deposits laid down by the lateral shifting

of channels, and flnc-grained vertical aeeretion deposits

resulting from overbank sedimentation, but there are many

varied combinations of all six. Based largely on the interrelated

properties of stream power and sediment character, Nanson.

and Croke identified Uiree floodplain classes; (1) high-energy

noneohesive; (2) medium-energy noncohesive; and (3) low-

energy cohesive (Figure Rll). To these they added 13

deri\ative orders and suborders that are based largely on the

floodplain forming processes. Miall (1996) incorporated this

essentially geomorphie model with his 1985 architectural

element analysis to develop a detailed system of fluvial

sedimentary faeies and styles (see Floodplain Sediments).

Although generally viewed as depositional elements,

flood-

plains ean also be subject to periods of intense erosion during

flood episodes, resulting in iuiasirophicsiiippiitg.

River deposits include a wide range of sediment types, but a

distinctive suite of facies is common to many channel and

floodplain settings. The reader is referred to Miall (1996) tbr a

detailed deseription of fluvial facies.

Channel

pattems:

their geomorphology

and

sedimentary facies

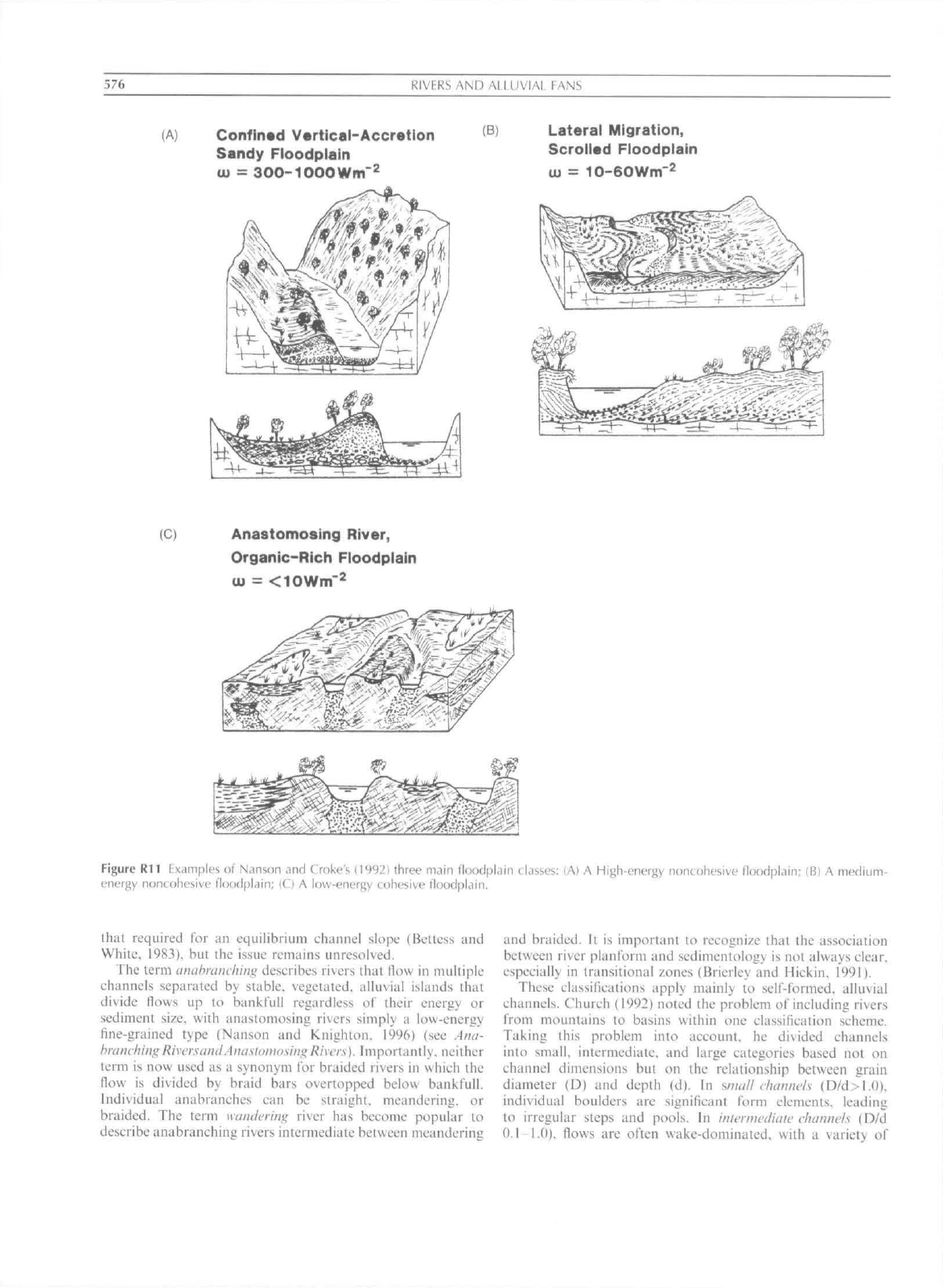

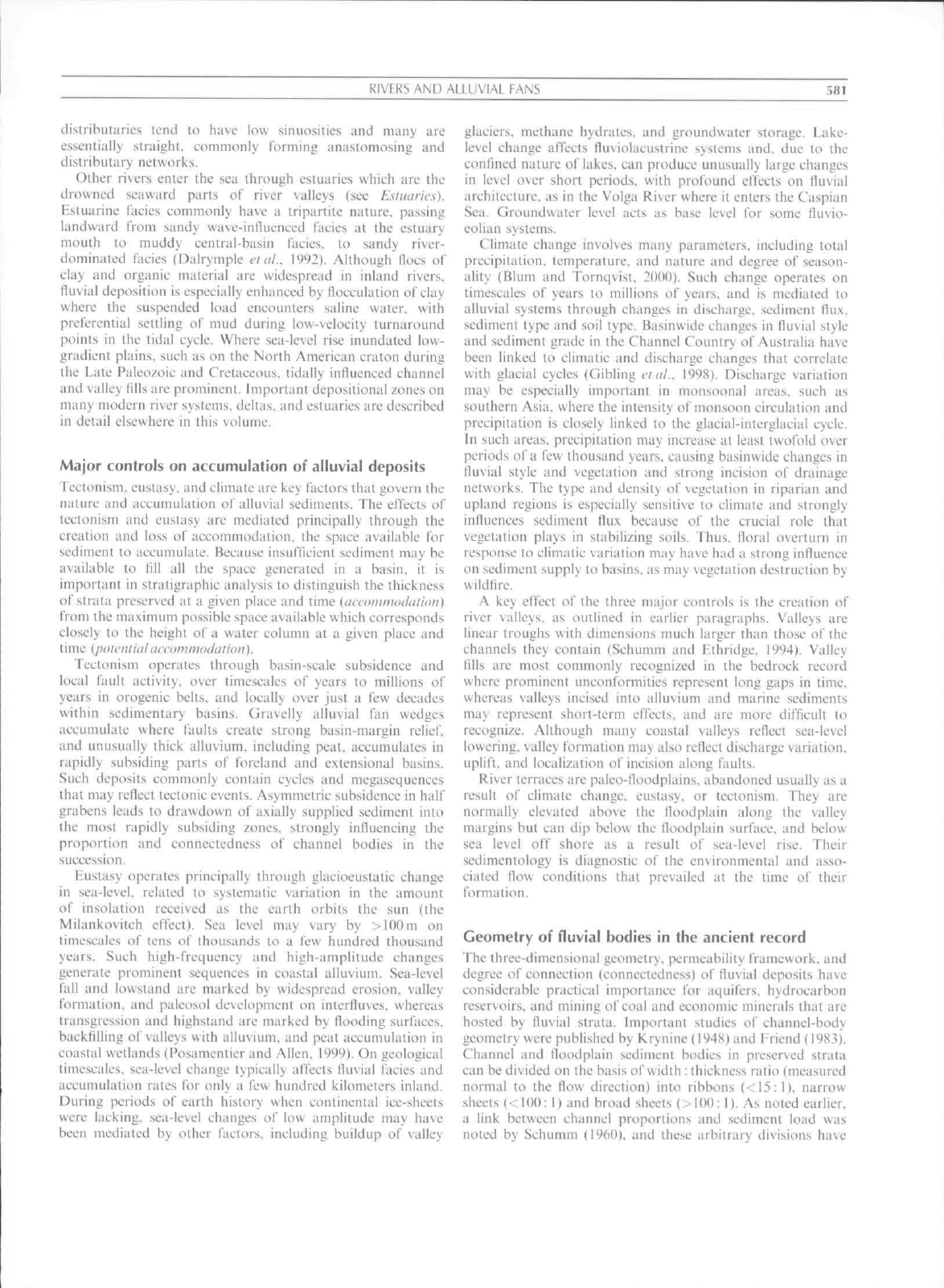

Rivers respond to imposed discharges and sediment conditions

by adjusting their channel pattern or planform In conjunction

with their hydraulic geometry. Because river patterns are so

easily recognized on air photos and maps they have beeome a

primary basis for river classiflcation (Figure Rt2). General-

izations IVom planform can be made in terms of lateral

stability, sediment

load,

sediment size, bed/suspended load

ratio,

uidth/depth ratio, Hoodplain type, and stratigraphy.

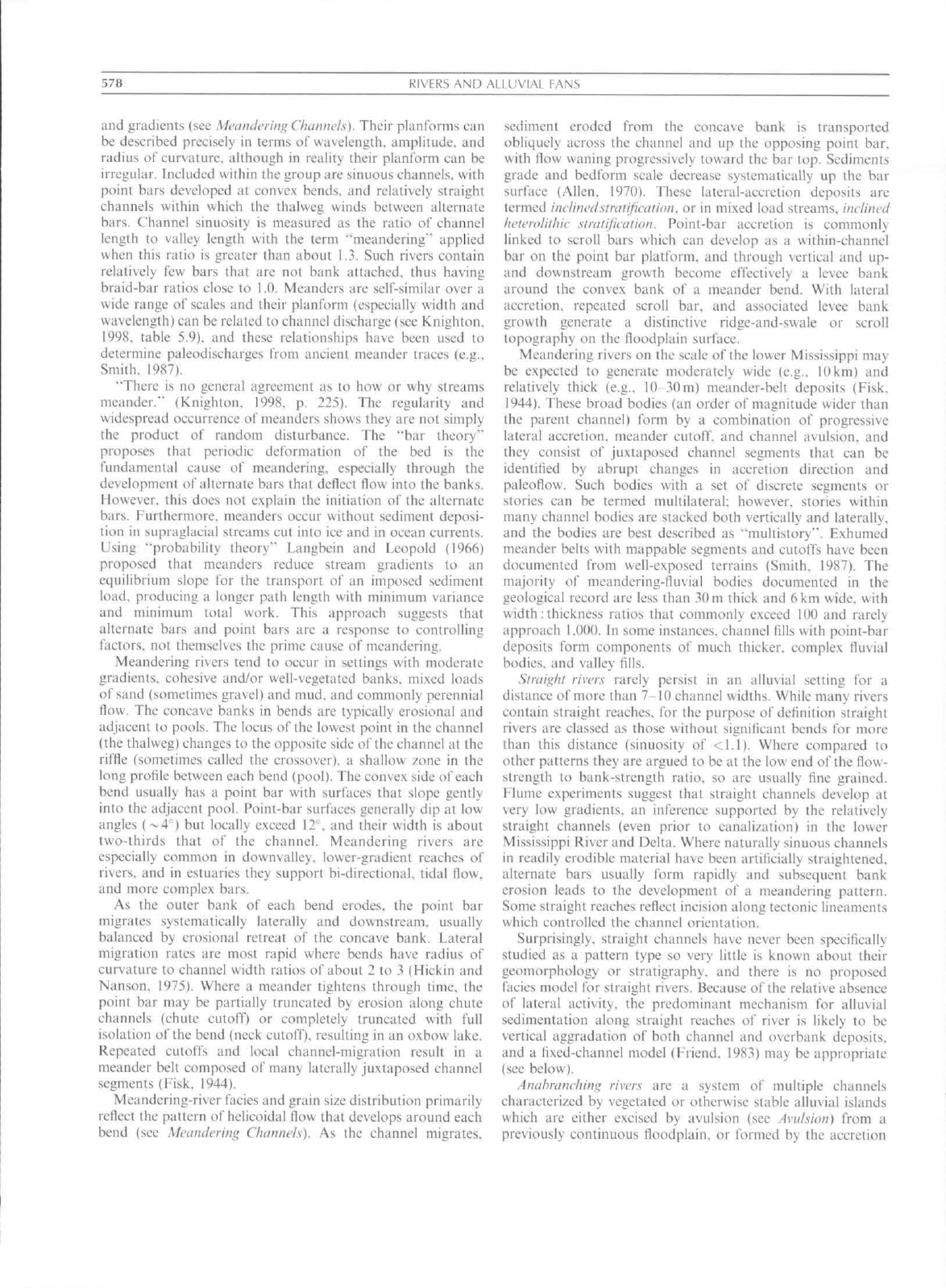

Leopold and Wolman (1957) proposed ihe flrst widely

adopted geomorphological classification with their concept of

a continuum of river patterns between end-members of

.straight, meandering, and braided. A significant problem is

that these are not mutually exelusive; for example, many

braided channels have a sinuous (meandering) planform.

Nevertheless, in an effort to retain the continuum approach,

more recent classifications have essentially adopted the

original tripartite system bul with additional types added.

the most distinctive being low energy, tine-grained multiple-

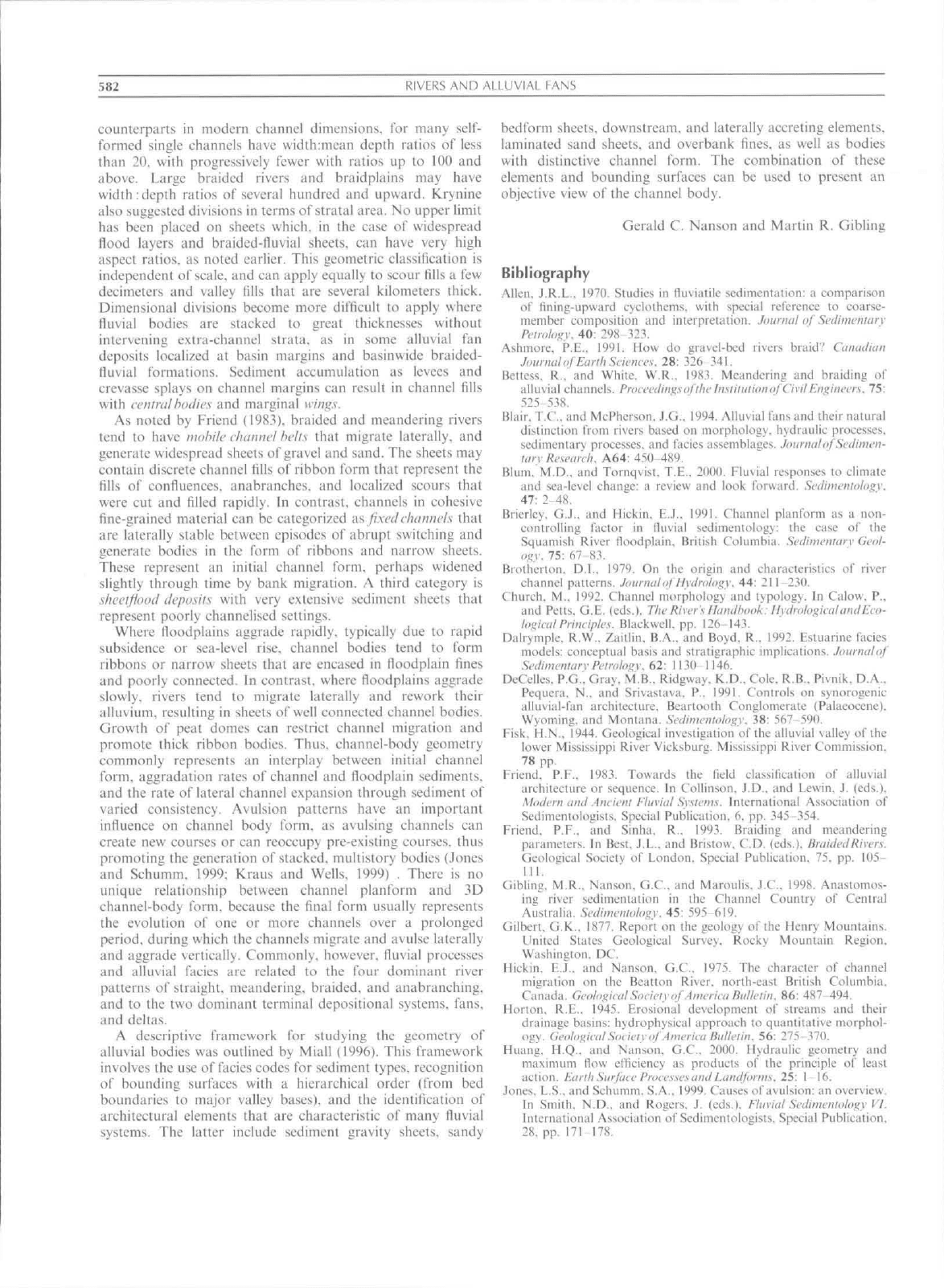

channel rivers termed anastomosing. The existence ofa broad

continuum of river patterns is evidenced in slope-discharge

plots that, in order of declining stream power and grain size,

separate rivers into braided, meandering, straight, and

anastomosing (Figure Rl.^). However, to date there is

insufficient evidenee to determine whether straight and

anastomosing channels ean be separated from eaeh other on

this basis alone. The concept that stream power and sediment-

caliber control the continuum has lead some to argue that the

relative ease of eroding and transporting bank material

determines channel patterns (Brotherton. 1979). Both mean-

dering and braiding patterns appear to reflect a need to

consume excess energy were the valley slope is greater than

576 RIVFRS AND ALLUVIAI TANS

(A) Confined Vertical-Accretion

Sandy Floodplain

tju = 300-1000 Wm"2

(B) Lateral Migration,

Scrolled Floodplain

10

=

10-60Wm~2

(C) Anastomosing

River,

Organic-Rich Floodplain

u)

=

<10Wm"2

Figure Rll Examples of Nanson and Croke's i1992) three main tloorlpUin classes: (A) A High-energy noncohesive floodpldin; (Bl A medium-

energy noncohesive lloodplain; (C) A low-energy cohesive floodpl.iin.

that required for an equilibrium ehannel slope (Bcttess and

While. 1983). but the issue remains unresolved.

The term anabranclting describes rivers that llow in multiple

channels separated by stable, vegetated, alluvial islands that

divide flows up lo bankfuil regardless of their energy or

sediment size, with anastomosing rivers simply a low-energy

fine-grained type (Nanson and Knighton. 1996) (see Ana-

hranihing Rivcrsand Anastomosing

Rivera).

Importantly, neither

term is now used as a synonym for braided rivers in which the

flow is divided by braid bars overtopped below bankfull.

Individual anabranches can be straight, meandering, or

braided.

The term wandering river has become popular to

describe anabranehing rivers intermediate between meandering

and braided. It is important to recognize that the association

between river plantbrm and sedimentology is not always clear,

espeeially in transitional zones (Brierley and Hiekin. 1991).

"Hiesc classifications apply mainly lo self-formed, alluvial

channels.

Church (1992) noted the problem of including rivers

from mountains to basins within one classification scheme.

Taking this problem into aecount. he divided channels

into small, imermediate. and large categories based not on

channel dimensions but on the relationship between grain

diameter (D) and depth (d). In ^mall ehannels (D/d>!.0),

individual boulders are significant form elements, leading

to irregular steps and pools. In intermediate ehannels (D/d

O.I 1.0). flows are often wake-dominated, with a variety of

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

577

Single-

. .

Channel Anabranehing

Rivers

island-foim

ts straight

c

stable-

sinuous

•^ meandering

braided

•D

loa

dime

•V

VI

ra

c

'^n

c^

ere

cal

"c

dime

VI

c

in

ra

ere

c

ro

•in

Iteral

JO

ra

c

[D

ta

0

0)

••

Figure R12 The tommon range of river p<itterns in sinj;lt.'-(_hannfl and

an.ihrani hing rivers. There is a trend of increasing gradient and

sediment (.alilire tincl load from lalerally inactive, to meandering, to

l)rai{lL'(i (muclificd Irom Nanson and Knighton, 1996).

10"

10"'

r

• braided - gravel

A braided-sand 1 4 16 e^i ^5e

^ anastomosing Djograin size (mm)

10"

10' 10^ 10^ lO'' 105

Bankfull Diseharge or Median Annual Flood, rrP s'

Figure R13 Ciravel braided, sand braided, and anastomosing channels

diffcrenti.itfd on slope-dist harge, with median grain size ID-^o) (aflor

Knightnn,

1')*)8}.

pools,

riffles, rapids, and bars, as well as steps, and jams

caused by logs and branches.

Large ehannels

(D/d<U.l) are

dominated by the water-flow regime, and exhibit deep shear

llow. and a well-dctincd \elocitv profile, wilh bedforms that

dissipate energy. The channel types described in the previous

paragraphs are typically large channels following this schetne.

and their fills predotniiiate in the tliivia! record. Small and

intermediate channel fllls arc probably important in the rock

record where linconforiiiitics include bedrock valleys with very

coarse sediment.

Braided Rivers

are relatively high-energy systems with large

width-depih ratios and at low stage have multiple channels

that divide and rejoin around alluvial bars (sec Braided

Channel.s).

They tend to occur in settings with steep gradients.

weakly cohesive banks, abundant coarse sediment, and

variable discharge (Leopold and Wolman. 1957: Knighton.

1998). Sediments are typically dominated by gravel and sand,

but silt-dominated systems arc also known. Braided rivers are

prominent near mountam and glacial fronts, range trom

humid to arid regions, and commonly change downvalley into

flner

grained,

single-channel systems, although some feed

directly into oceans, and lakes as

hraiddelta.s.

The Brahmapu-

tra River, one of the world's largest braided systems, has a

channel-belt width of up to 20

km.

with individual channels

several kilometers wide and maximum scour depths of up to

50

m.

however, braiding can also occur in small streams

crossing a sandy beach.

While processes and relationships between variables can be

described,

a widely accepted rational explanation Ibr braiding

has been elusive. Leopold and Wolman (1957) argued that

braiding is an equilibrium adjustment to erodible banks and a

debris load excessive for a single channel. Some workers have

differentiated between braiding caused by the above, and that

designed to consume energy in less-efflcient multiple channels

as a result of excessively steep valley gradients. Ibllowing

observations that degree of braiding may increase as slope

steepens (Bcttess and White. 19S3).

ln a detailed flume study. Ashmore (1991) found that

braiding can develop in four ways: (I) growth of

a

central bar

without avalanche laces, commonly linked to stalling ofcoarse

bed-load in the channel center (Leopold and Wolman. 1957);

(2) scour at pools leading to deposition ofa downchannel lobe,

wilh stalling of bed-load sheets on the lobe top and subsequent

development of a mid-channe! bar with avalanche faces;

(3) chute cut-off of mid-channel and point (bank-attached)

bars,

with the formation of a new, discrete ehannel; and

(4) dissection of lobate bars by multiple channels. Others cile

avulsion within the channel belt as a bar-forming process

(Kraus and Wells. 1999). Repetition of these dynamic

processes along the river produces a comple.\ array of

interacting channels and bars. In difTerent environtnents.

channels can be aggradational. vertically stable, and incisional

but all situations are eharacterized by frequent shifts in

channel position. Many changes in braided

rivei"

morphology

occur episodically, even at constant discharge, as a result of

short-term fluctuations in the transport rate related in

particular lo bed-load pulses.

Friend and Sinha (1993) defined the intensity of braiding

using a hraid-dninnelratio. B. which measures the tendency of

a ehannel reach to develop mukiple channels. B= L^-i,,i/L^.,,,,,^.

where L^.un is the sum of the mid-channel lengths of all primary

channel segments in a reach, and

L^.,,,:,\

i^ the mid-channel

length of the widest channel in the reach.

Braided river deposits in the rock record are typically

composed of

suites

of channel fllls or stories thai are stacked to

form complex (multistory) bodies dominated by sandstone and

conglomerate. Bar deposits are identifled as large-scale sets of

inclined strata that tend to dip downstream and oblique to

flow, although lateral accretion is common. The channel

bodies range from a few meters to hundreds of meters thick,

with some especially thick occurrences exceeding I km of

coarse-grained strata, and they vary from small bodies

embedded in floodplain mudstones to extensive, basin-scale

sheets.

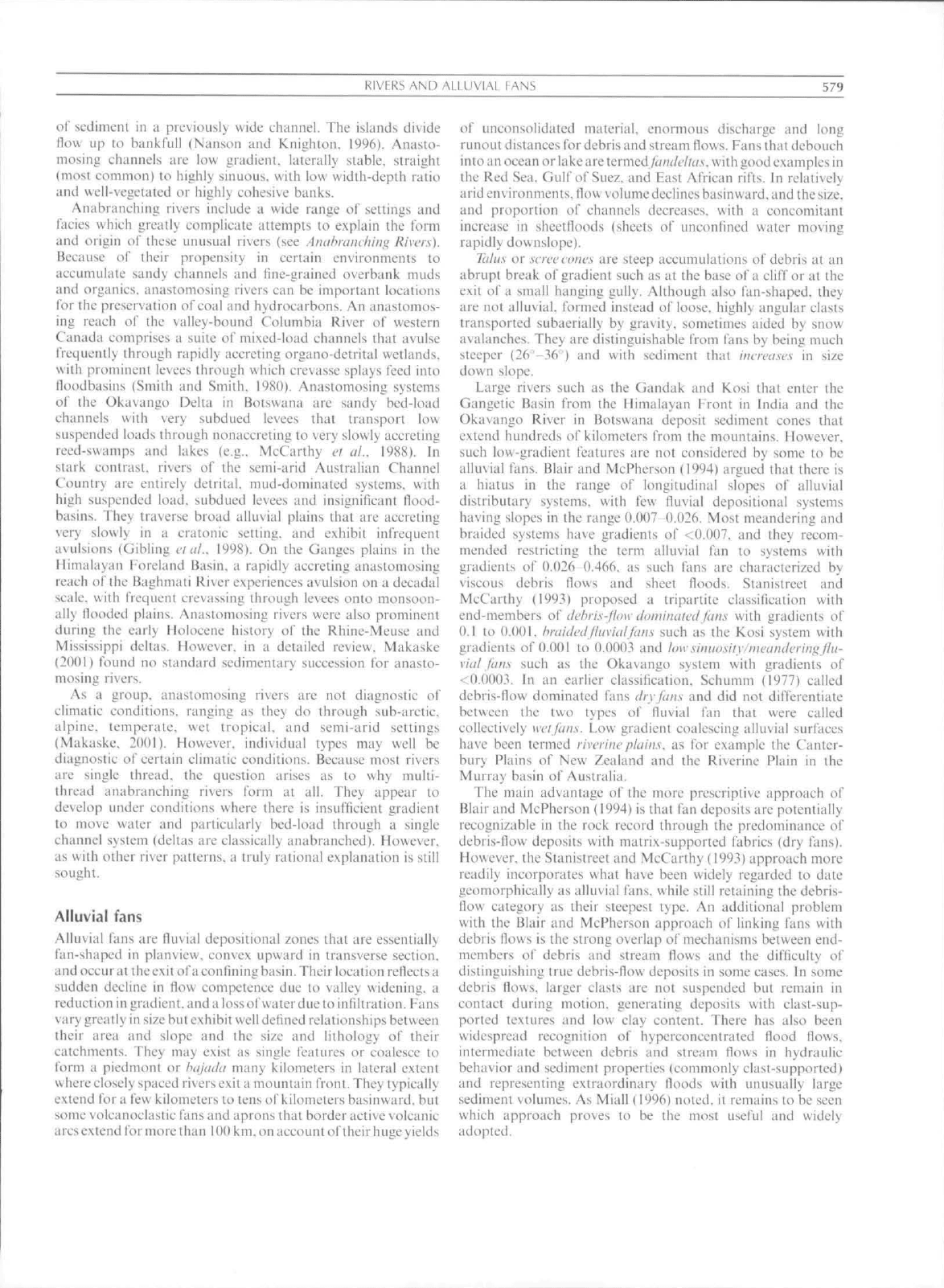

Meandering Rivers are usually moderate-energy, single-

chanclcd.

and sinuous rivers with moderate width-depth ratios

578 KIVFRS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

and gradients (see Meandering Channels). Their planforms can

be described precisely in terms of wavelength, amplitude, and

radius of curvature, although in reality their planform can be

irregular. Included within the group are sinuous channels, with

point bars developed at convex bends, and relatively straight

channels within which the thalweg winds between alternate

bars.

Channel sinuosity is measured as the ratio of channel

length to valley length with the term "meandering" applied

when this ratio is greater than about 1.3. Such rivers contain

relatively few bars that are not bank attached, thus having

braid-bar ratios close to 1.0. Meanders are self-similar over a

wide range of scales and their planlbrm (especially width and

wavelength) can be related to channel discharge (see Knighton,

1998.

table 5.9). and these relationships have been used to

determine paieodischarges from ancient meander traces (e.g.,

Smith. 1987).

"There is no general agreement as to how or why streams

meander." (Knighton, 1998, p. 225). The regularity and

widespread occurrence of meanders shows they are not simply

the product of random disturbance. The "bar theory"

proposes that periodic deformation of the bed is the

fundamental cause of meandering, especially Ihrough the

development of alternate bars that deflect tlow into the banks.

However, this does not explain the initiation of the alternate

bars.

Furthermore, meanders occur without sediment deposi-

tion in supraglacial streams cut into ice and in ocean currents.

Using "probability theory" Langbein and Leopold (1966)

proposed that meanders reduce stream gradients to an

equilibrium siope for the transport of an imposed sediment

load, producing a longer path length with minimum variance

and minimum total work. This approach suggests that

alternate bars and point bars are a response to controlling

factors, not themselves the prime cause of meandering.

Meandering rivers tend to occur in settings with moderate

gradients, cohesive and/or well-vegetated banks, mi.xed loads

of sand (sometimes gravel) and mud, and commonly perennial

flow. The concave banks in bends are typically erosional and

adjacent to pools. The locus of the lowest point in the channel

(the thalweg) changes to the opposite side of the channel at the

riffle (sometimes called the crossover), a shallow zone in the

long profile between each bend (pool). The convex side of eaeh

bend usually has a point bar with surfaces that slope gently

into the adjacent pool. Point-bar surfaces generally dip at low

angles

(-^4°)

but locally exceed 12', and their width is about

two-thirds that of the ehannel. Meandering rivers are

especially common in downvailey. lower-gradient reaches of

rivers,

and in estuaries they support bi-directional, tidal flow.

and more complex bars.

As the outer bank of each bend erodes, the point bar

migrates systematically laterally and downstream, usually

balanced by erosional retreat of the concave bank. Lateral

migration rates are most rapid where bends have radius of

curvature to channel width ratios of about 2 to 3 (Hiekin and

Nanson, 1975). Where a meander tightens through time, the

point bar may be partially truncated by erosion along chute

channels (chute cutoff) or completely truncated with full

isolation oi'the bend (neck cutofQ. resulting in an oxbow lake.

Repeated cutoffs and local ehannel-migration result in a

meander belt composed of many laterally juxtaposed channel

segments (Fisk. 1944).

Meandering-river facies and grain size distribution primarily

reflect the pattern of helicoidal flow that develops around each

bend (see Meandering Channels). As the channel migrates.

sediment eroded from the concave bank is transported

obliquely across the channel and up the opposing point bar.

with flow waning progressively toward the bar top. Sediments

grade and bedform scale decrease systematically up the bar

surface (Allen. 1970). These lateral-accretion deposits are

termed inclined stratification, ox in mixed load streams, inclined

heterolithic

.•itratification.

Point-bar accretion is commonly

linked to scroll bars which ean develop as a within-ehannel

bar on the point bar platform, and through vertical and up-

and downstream growth become effectively a levee bank

around the convex bank of a meander bend. With lateral

accretion, repeated scroll bar. and associated levee bank

growth generate a distinctive ridge-and-swale or scroll

topography on the tloodplain surface.

Meandering rivers on the seale of the lower Mississippi may

be expected to generate moderately wide (e.g., iOkm) and

relatively thick (e.g.. 10- 30m) meander-belt deposits (Fisk,

1944).

These broad bodies (an order of magnitude wider than

the parent ehannel) form by a combination of progressive

lateral accretion, meander

cutoff,

and channel avulsion, and

they consist of juxtaposed channel segments that can be

identified by abrupt changes in accretion direction and

paleoflow. Such bodies with a set of discrete segments or

stories can be termed multilateral: however, stories within

many channel bodies are stacked both vertically and laterally,

and the bodies are besi described as "multistory". Exhumed

meander belts with mappable segments and cutoffs have been

documented from well-exposed terrains (Smith, 1987). The

majority of meandering-fluvial bodies documented in the

geological record are less than 30 m thick and 6 km wide, with

width; thickness ratios that commonly exceed 100 and rarely

approach

1.000.

In some instances, channel fills with point-bar

deposits form components of much thicker, complex iluvial

bodies, and valley tills.

Straight rivers rarely persist in an alluvial setting tbr a

distance of more than 7-10 channel widths. While many rivers

contain straight reaches, for the purpose of definition straight

rivers are classed as those without signilicant bends for more

than this distance (sinuosity of <l.l). Where compared to

other patterns they are argued to be at the low- end of the flow-

strength to bank-strength ratio, so are usually fine grained.

Flume experiments suggest that straight channels develop at

very low gradients, an inference supported by the relatively

straight channels {even prior to canalization) in the lower

Mississippi River and Delta. Where naturally sinuous channels

in readily erodible material have been artificially straightened,

alternate bars usually form rapidly and subsequent bank

erosion leads lo the development of a meandering pattern.

Some straight reaches reflect incision along tectonic lineaments

whieh controlled the channel orientation.

Surprisingly, straight ehannels have never been specifically

studied as a pattern type so very little is known about their

geomorphology or stratigraphy, and there is no proposed

facies model fbr straight rivers. Becatise of the relative absence

of lateral activity, the predominant mechanism for alluvial

sedimentation along straight reaches of river is likely to be

vertical aggradation of both channel and overbank deposits,

and a fixed-channel mode! (Friend, 1983) may be appropriate

(see below).

Anahranching river.s are a system of multiple channels

eharacterized by vegetated or otherwise stable alluvial islands

which are either excised by avulsion (see Avulsion) from a

previously continuous floodplain. or formed by the accretion

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL hANS

579

of sediment in a previously wide channel. The islands divide

flow up to bankfull (Nanson and Knighton, 1996). Anasto-

mosing channels are low gradient, laterally stable, straight

(most common) to highly sinuous, with low width-depth ratio

and well-\egetated or highly cohcsi\e banks.

Anabranehing rivers include a wide range of settings and

facies which greatly complicate attempts to explain the form

and origin of these unusual rivers (see Anahranching Rivers).

Because of their propensity in certain environments to

accumulate sandy channels and line-grained overbank muds

and organics, anastomosing rivers can be important locations

fbr the preservation of coal and hydrocarbons. An anastomos-

ing reach of the valley-bound Columbia River of western

Canada comprises a suite of mixed-load channels that avulse

frequently through rapidly accreting organo-detrital wetlands,

with prominent levees through which erevasse splays feed into

floodbasins (Smith and Stnith. 1980). Anastomosing systems

of the Okavango Delta in Botswana are sandy bed-load

channels with very subdued levees that transport lou

suspended loads through nonaccreting to very slowly accreting

reed-swamps and lakes (e.g., McCarthy et al., 1988). In

stark contrast, rivers of the semi-arid Australian Channel

Country are entirely detritai. mud-dominated systems, uith

high suspended load, subdued levees and insignificant flood-

basins. They traverse broad alluvial plains that are accreting

very slowly in a cratonic setting, and exhibit infrequent

avulsions (Gibling etal.. 1998). On the Ganges plains in the

Himalayan Foreland Basin, a rapidly accreting anastomosing

reach of the Baghmali River experiences avulsion on a decadal

scale, with frequent crevassing through levees onto monsoon-

ally flooded plains. Anastonnising rivers were also prominent

during the early Holocene history of the Rhine-Meuse and

Mississippi deltas. However, in a detailed review, Makaske

(2001) fbund no standard sedimentary succession for anasto-

mosing rivers.

As a group, anastomosing rivers are not diagnostic of

climatic conditions, ranging as they do through sub-arctic,

alpine, temperate, wet tropical, and semi-arid settings

(Makaske. 2001). However, individual types may well be

diagnostic of certain climatic conditions. Beeause most rivers

are single thread, the question arises as to why multi-

ihread anabranehing rivers fbrm at ail. They appear to

develop under eonditions where there is insufficient gradient

to move water and particularly bed-ioad through a single

channel system (deltas are classicaliy anabranched). However,

as with other river patterns, a truly rational explanation is still

sought.

Alluvial fans

Alluvial fans are fluvial depositional zones that are essentially

fan-shaped in planview. convex upward in transverse section,

and occur ai the exit of

a

confining basin. Their location reflects a

sudden decline in flow competence due to valley widening, a

reduction in gradient, and a loss of water due tiiinfilt ration. Fans

vary greatly in si7e but exhibit well defined relationships between

their area and slope and the si.^e and lithology of their

catchments. They may exist as single features or coalesce to

form a piedmont or hajada many kilometers in laterai extent

where closely spaced rivers exit a mountain fVont. They typically

extend for a few kilometers to tens of kilometers basinward. but

some volcanoclastic fans and aprons that border active volcanic

arcs extend fbr more than 100 km. on account of their huge yields

of unconsolidated material., enormous discharge and long

runout distances fbr debris and stream flows. Fans that debouch

into an ocean or lake are termed/(//i(/c//(/.v. with good examples in

the Red Sea, Gulf of Suez, and East African rifts. In relaiively

arid etivironmenls. flow volume declines basinward, and the size,

and proportion of channels decreases, wilh a concomitant

increase in sheelfloods (sheets of unconfined water moving

rapidly downslope).

Talus or

seree cones

are steep accumulations of debris at an

abrupt break of gradient such as at the base ofa eliff or at the

exit ofa small hanging gully. Although also fun-shaped, they

are not alluvial, formed instead of loose, highly angular clasts

transported subaerially by gravity, sometimes aided by snow

avalanches. They are distinguishable from fans by being mueh

steeper (26-36 ) and with sediment that inereases in size

down slope.

Large rivers such as the Gandak and Kosi that enter the

Gangetic Basin from the Himaiayan Front in India and the

Okavango River in Botswana deposit sediment cones that

extend hundreds of kilometers from the mountains. However,

such lou-gradient features are not considered by some to be

allu\ial fans. Blair and McPherson (1994) argued that there is

a hiatus in the range of longitudinal slopes of alluviai

distributary systems, with few fluvial depositional systems

having slopes in the range 0.007 0.026. Most meandering and

braided systems have gradients of <0.007, and they recom-

mended restricting the term ailuvial fan to systems with

gradients of 0.026 0.466. as such fans are characterized by

viscous debris flous and sheet floods. Stanistreet and

McCarthy (1993) proposed a tripartite classification with

end-members of debris-flow dominated

fan.s

with gradients of

O.I to

0.001,

braided fluvial fans such as the Kosi system with

gradients of O.OOi to 0.0003 and

low

sinuosity/meandering fiu-

vial fans such as the Okavango system with gradients of

<0.0003.

In an earlier classification, Sehumm (1977) calied

debris-flow dominated fans dry fans and did not differentiate

betueen the two types of fiuvial fan that were called

collectively

wet

fans, l.ow gradient coalescing alluvial surfaces

have been termed riverine plains, as fbr example the Canter-

burv Plains of New Zealand and the Riverine Plain in the

Murray basin of Australia.

The main advantage of the more prescriptive approach of

Blair and MePherson (i994) is that fan deposits are potentiaily

recognizable in the rock record through the predominance of

debris-flow deposits with matrix-supported fabrics (dry fans).

Houever, the Stanistreet and McCarthy (1993) approaeh more

readily incorporates wiiat have been widely regarded to date

geomorphically as alluvial fans, while stiti retaining the debris-

flow category as their steepest type. An additional problem

with the Blair and McPiierson approach of linking fans with

debris flows is the strong overlap of mechanisms between end-

members of debris and stream flows and the difficulty of

distinguishing true debris-flow deposits in some cases. In some

debris flows, larger clasts are not suspended but remain in

contact during motion, generating deposits with clast-sup-

ported textures and iow elay eontent. There has also been

widespread recognition of hyperconcentrated flood flows,

intermediate between debris and stream flows in hydraulic

behavior and sediment properties (commonly clast-supported)

and representing extraordinary floods witii unusually iarge

sediment volumes. As Miall (1996) noted, it remains to be seen

which approach proves to be the most useful and widely

adopted.

580

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

Dry fan development is known to be prevalent today,

especially in arid upland regions with sparsely vegetated slopes

subject to infrequent flash flooding. Wet fans were predomi-

nant in the geologie past, especially in glacial periods with

abundant seasonal snowmelt. and are still active today in some

humid upland regions with frequent runoff (Schumm. 1977).

Because of the limited travel-distanee and viscosity of debris

flows, dry fans tend to be small, and relatively steep. Debris

flow deposits in the near-source part of the fan are poorly

sorted and often matrix-supported with angular clasts and

outsize boulders. Running water reworks them through sheet

and channel flow into a downslope progression of gravel and

sand, with mud predominant near the fan toe. The lower fan

can be characterized by braided stream deposition. Debris

Bows aggrade the upper fan, but fluvial action can periodically

cause entrenchment, producing a complex topography. "Sieve

deposits" of well-sorted gravel without matrix, identified as a

distinctive sediment type on some fans, may be debris-flow

deposits from which fines have largely been winnowed at the

surface.

Wet fans can be small or large and show pronounced

sediment-size sorting, clast rounding and traction-current

deposition. Alternating aggradation and incision near the

fan head produces coarse overbank sheetflow deposits and

splays as well as trenched ehannels with longitudinal gravel

bars.

The mid fan consists of typically braided channels that

switch baek and forth depositing longitudinal gravel and

transverse sand bars. The lower fan is characterized by

transverse bars or dunes with overbank mud and the channels

meander in places, as in the Kosi Fan of northern India.

Experimental work by Schumm (1977) and Schumm etal.

(1987) identify two main autogenic processes in the upper to

middle part of braided wef fans: the avulsive shifting of

distributary channels and a cyclic trenching and backfilling of

channels. These alternations can be controlled entirely by

intrinsic thresholds relating to sediment supply from the basin

and deposition on the fan. During the trenching phases, coarse

sediment is moved more effectively down the fan whereas with

backfilling the fan aggrades and sediment is distributed across

the surface by sheet flow. With fan building, segmentation ean

produce individual depositional zones or lobes, each asso-

ciated with an individual distributary channel (Schumm elal..

1987).

In combination they build to form the fan as a whole.

Climate undoubtedly affeets fan development. During wet

periods wet fans are usually strongly aggradational whereas

extensive trenching can occur in dry periods.

Coarse-grained, permeable fan sediment promotes ground-

water recharge, resulting in strong transmission losses and the

demise of perennial rivers over the fan surface. In arid regions

the groundwater may discharge beyond the fan margin,

resulting in evaporitic playa lakes in arid regions such as

Death Valley. California, as well as promoting enhanced

vegetation growth in some areas. Large groundwater resources

are associated with many fans. Some interfan areas have little

fluvial activity, and arid-zone fans may interfinger with eolian

deposits. However, very active rivers ean be present between

large cones, fbr example the Baghmati River that lies between

the Gandak and Kosi cones in northern India. Channel

switching on fans results in inactive areas where soil fbrmation

and ehemieal effects, such as fbrmation of desert varnish, are

enhanced.

Alluviai fan deposits in the rock record may be hundreds

of meters thick and commoniy occupy rapidly subsiding

exfensional and fbreland basins where faults controlled basin-

margin

relief.

Most are a few tens of square kilometers in area,

but some large, wedge-shaped volcanoclastic aprons cover

areas of lO'^km"^ and are up to I km thick. Fan deposits are

typically poorly channelized and comprise amalgamated

narrow channel (ribbon) bodies and broad (sheet) bodies of

conglomerate and sandstone, i^ownllow. ribbons, and narrow

sheets of conglomerate and sandstone are interbedded with

mudstones, and mark the positions of major distributaries and

fan lobes in more basinward settings, sometimes passing

distally into sheetflood deposits.

DeCelles etal. (1991) documented wet fan deposits in the

Cenozoic of the western US with cycles of aggradation and

degradation. Periods of aggradation and flow expansion near

the fan apex generated broad sheets which were subsequently

incised, allowing sediment to bypass the upper fan through

deep channels. The cycie was completed with channel back-

fiiling and renewed dispersal over the fan surface. The resulting

lithosomes are 10m to 50m thick and up to several kilometers

wide, and are composed of smaller channel bodies in the fbrm

of scour-based sheets up to lOm thick and hundreds of meters

wide. Similar episodes of sheet aggradation under conditions

of high suppiy. followed by incision as supply waned are also

prominent in volcanoclastic fan and apron deposits. Other f^an

deposits consist of overlapping lobes of gravel separated by

thin paleosols. These studies underline the importanee of

sediment supply in eontrolling fan architecture, commonly

linked to climatic change or voleanism. Trenching may also

have extrinsic causes, such as tilting or base-level rise in fan

deltas,

and extensional basins have complex fault systems

where rapid shifts of activity and sediment supply along fault

segments can result in complex sedimentation patterns in

f\ins

and bajadas.

Many fan deposits consist of cycles or megasequences, tens

to hundreds to mefers thick, that coarsen or fine upward.

Coarsening upward cycles represent the basinward advance of

fan lobes or entire fans, bringing coarse sediment over basinal

fines. In contrast, fining upward cycles reflect declining

sediment supply due to scarp retreat, fault-block evolution,

denudation of topography, or gradual abandonment of fan

segments. In strike-slip basins, entire fan bodies may represent

the lateral migration of the depocenter past the fan entry point,

so that the fan is progressively detached from its feeder

channei. The presence of fan wedges in basina! fills may imply

tectonic activity and uplift of a nearby source area, or may

imply periods of tectonic quiescence followed by trenching and

dispersal of fan .sediment farther out into the basin. Fan and

other fluvial deposits may also build basinward as thrusts

advanee, with deformation and cannibalization of fan

sediments below the thrust mass. The location of f^ans close

to tectonically active areas can cause early tectonic deforma-

tion, including the development of unconformities.

Deltas and estuaries

Rivers of all types arc influenced by coastal processes. Most

large rivers with high sediment loads terminate in delta

distributary systems on open marine shelves (shelf-phase

deltas) or on the shelf margin at iowstand or where the shelf

is unusually narrow (shelf-margin deltas) (see Deltas). They

may also terminate as bayhead deltas in restricted embay-

ments. in back-barrier lagoons or in fVeshwater lakes. Linder

the low gradients typical of rivers approaching the coast.

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

distributaries tend to have tow sinuosities and many arc

essentially straight, commonly forming anastomosing and

distributary networks.

Other rivers enter the sea through estuaries which are the

drowned seaward parts of river valleys (see Estuaries).

Fstuarine facies commonly have a tripartite nature, passing

landward from sandy wave-influenced facies at the estuary

mouth to muddy central-basin facies. to sandy river-

dominated facies (Dalrymple etal.. 1992). Although floes of

clay and organic material are widespread in inland rivers,

fluvial deposition is espeeially enhanced by floceulation of clay

where the suspended load encounters saline water, with

preferential settling of mud during low-velocity turnaround

points in the tidal c\cle. Where sea-level rise inundated low-

gradient plains, such as on the North American craton during

the Late Paleozoic and Cretaceous, tidally influenced channel

and vailey fills are prominent. Important depositional /ones on

many modern river systems, deltas, and estuaries are described

in detail elsewhere in this volume.

Major controls on accumulation of alluvial deposits

Tectonism, eustasy. and climate are key factors that govern the

nature and accumulation of alluvial sediments. The effects of

tectonism and eustasy are mediated principally through the

creation and loss of accommodation, the space available fbr

sediment to accumulate. Because insufficient sediment may be

available to fill all the space generated in a basin, it is

important in stratigraphic analysis to distinguish the thickness

of strata preserved at a given place and time {accommodation)

from the maximum possible space available which corresponds

closely to the height of a water column at a given place and

time (potentialaeconunodation).

Tectonism operates through basin-scale subsidence and

local fault activity, over timescales of years to millions of

years in orogenic belts, and loeally over just a few decades

within sedimentary basins. Gravelly alluvial fan wedges

accLunulate where faults create strong biisin-margin

relief,

and unusualiy thick alluvium, including peat, accumulates in

rapidly subsiding parts of foreland and extensional basins.

Such deposits commonly contain cycles and megasequences

that may reflect tectonic events. Asymmetric subsidence in half

grabens leads to drawdown of axially supplied sediment into

the most rapidly subsiding zones, strongly influencing the

proportion and eonneetedness of channel bodies in the

succession.

Eustasy operates principally through glacioeustatic change

in sea-level, related to systematic variation in the amount

of insolation received as the earth orbits the sun (the

Milankovitch effect). Sea level may vary by >100m on

timescales of tens of thousands to a few hundred thousand

years.

Sueh high-frequency and high-amplitude changes

generate prominent sequences in coastal alluvium. Sea-level

fall and lov\stand are marked by widespread erosion, valley

fbrmation. and paleosol development on interlluves, whereas

li'ansgression and highstand are marked by flooding surfaces,

backfilling of \alleys uith alluvium, and peat accumulation in

coastal wetlands (Posamentier and Allen. 1999). On geological

timescales. sea-level change typically alTeets fluvial facies and

accumulation rates fbr only a fc*w hundred kilometers inland.

During periods of earth history when eontinental ice-sheets

were lacking, sea-level changes of low amplitude may have

been mediated by other factors, including buildup of valley

glaciers, methane hydrates, and groundwater storage. Lakc-

levei change affeets fiuviolacustrine systems and. due to the

confined nature of lakes, can produce unusually large changes

in level over short periods, with profound effects on fluvial

architecture, as in the Volga River where it enters the Caspian

Sea. Groundwater level acts as base level fbr some fluvio-

eolian systems.

Ciiniate change involves many parameters, including total

precipitation, temperature, and nature and degree of season-

aiity (Blum and Tornqvist. 2000). Such change operates on

timescales of years to millions of years, and is mediated to

ailuvial systems through changes in discharge, sediment flux.

sediment type and soil type. Basinwide ehanges in fluvial style

and sediment grade in the Channel Country of Australia have

been linked to elimatic and discharge changes that correlate

with glaeiai cycles (Gibling etal.. 1998). Discharge variation

may be especially important in monsoonal areas, such as

southern Asia, where the intensity of monsoon circulation and

precipitation is closely linked to the glacial-interglacial cycle.

In such areas, precipitation may increase at least twofbid over

periods ofa lew thousand years, causing basinwide changes in

fluvial style and vegetation and strong incision of drainage

networks. The type and density of vegetation in riparian and

upland regions is especially sensitive to climate and strongly

influences sediment flux because of the crucial role that

vegetation plays in stabilizing soils. Thus, floral overturn in

response to climatic variation may have had a strong influence

on sediment supply to basins, as may vegetation destruction by

wildfire.

A key effect of the three major controls is the creation of

river valleys, as outlined in earlier paragraphs. Valleys are

linear troughs with dimensions much larger than those of the

channels they contain (Schumm and Ethridge, 1994). Valley

fills are most commonly recognized in the bedrock record

where prominent unconformities represent long gaps in time,

whereas valleys incised into alluvium and marine sediments

may represent short-term elTects, and are more difficult to

recognize. Although many coastal valleys reflect sea-level

lowering, valley fbrmation may also reflect discharge variation.

uplift, and loealization of incision along fauits.

River terraces are paleo-floodplains, abandoned usually as a

result of ciimate change, eustasy. or tectonism. They are

normally elevated above the floodplain along the valley

margins but can dip below the (loodplain surface, and below

sea level off shore as a result of seii-Ievel rise. Their

sedimentology is diagnostic ol' the environmental and asso-

ciated flow conditions that prevailed at the time of their

fbrmation.

Geometry of fluvial bodies in the ancient record

The three-dimensional geometry, permeability framework, and

degree of connection (connectedness) of fluvial deposits have

considerable practical importance fbr aquifers, hydrocarbon

reservoirs, and mining of coal and economic minerals that arc

hosted by flu\ial strata. Important studies of channel-body

geometry were published by Krynine (194S) and Friend (1983).

Channel and floodplain sediment bodies in preserved strata

ean be divided on the basis of width

:

thiekness ratio (measured

normal to the flow direction) into ribbons (<15:l), narrow

sheets (<l()0: 1) and broad sheets (> 100: I). As noted earlier.

a iink between channel proportions and .sediment load was

noted by Schumm (19(S0). and these arbitrary divisions have

582

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAI. FANS

counterparts in modern channel dimensions, for many

seif-

formed single channels have width:mean depth ratios of less

than 20. with progressively fewer with ratios up to 100 and

above. Large braided rivers and braidplains may have

width;depth ratios of several hundred and upward. Krynine

also suggested divisions in terms of stratal area. No upper limit

has been placed on sheets which, in the case of widespread

flood layers and braided-fluvial sheets, can have very high

aspect ratios, as noted earlier. This geometric classification is

independent of scale, and can apply equally to seour fills a few-

decimeters and valley tills that are several kilometers thick.

Dimensional divisions become more difficult to apply where

fluvial bodies are stacked to great thicknesses without

intervening extra-channel strata, as in some alluvial fan

deposits localized at basin margins and basinwide braided-

fluvial formations. Sediment accumulation as levees and

erevasse splays on channel margins can result in channel fills

with central bodies and marginal

wing.'i.

As noted by Friend (i983), braided and meandering rivers

tend to have tnohile channel belts that migrate laterally, and

generate widespread sheets of gravel and sand. The sheets may

contain discrete channel fills of ribbon form that represent the

fills of confluences, anabranches, and localized scours that

were cut and filled rapidly. In contrast, channels in cohesive

fine-grained material can be categorized

'^s

fixed channels that

are laterally stable between episodes of abrupt switching and

generate bodies in Ihe fbrm of ribbons and narrow sheets.

These represent an initial channel fbrm. perhaps widened

slightly through time by bank migration. A third category is

sheetflood deposits with very extensive sediment sheets that

represent poorly channelised settings.

Where floodplains aggrade rapidly, typically due to rapid

subsidence or sea-level rise, channel bodies tend to form

ribbons or narrow sheets that are encased in floodpiain fines

and poorly connected. In contrast, where floodplains aggrade

slowly, rivers tend to migrate laterally and rework their

alluvium, resulting in sheets of well connected channel bodies.

Growth of peat domes can restrict channel migration and

promote thick ribbon bodies. Thus, channel-body geometry

commonly represents an interplay between initial channel

form, aggradation rates of channel and floodplain sediments,

and the rate of lateral ehannel expansion through sediment of

varied consistency. Avulsion patterns have an important

influence on channel body form, as avulsing ehannels can

ereate new courses or can reoccupy pre-existing courses, thus

promoting the generation of stacked, multistory bodies (Jones

and Schumm, V)99: Kraus and Wells. 1999) . There is no

unique relationship between ehannel planform and 3D

channel-body fbrm. because the f^inal form usually represents

the evolution of one or more ehannels over a prolonged

period, during which the channels migrate and avulse laterally

and aggrade vertically. Commonly, however, fluvial processes

and alluvial faeies are related to the four dominant river

patterns of straight, meandering, braided, and anabranehing,

and to the two dominant terminal depositional systems, fans,

and deltas.

A descriptive framework fbr studying the geometry of

alluvial bodies was outlined by Miall (1996). This framework

involves the use of facies codes fbr sediment types, recognition

of bounding surfaces with a hierarchical order (from bed

boundaries to major valley bases), and the identification of

architectural elements that are characteristic of many fluvial

systems- The latter include sediment gravity sheets, sandy

bedfbrm sheets, downstream, and laterally accreting elements,

laminated sand sheets, and overbank fines, as well as bodies

with distinctive channel fbrm. The combination of these

elements and bounding surfaces can be used to present an

objective view of the channel body.

Gerald C. Nanson and Martin R. Gibling

Bibliography

Allen. J.R.L.. 1970. Studies in fluviatifc sedimentation: a comparison

of fining-upuard cycloihems. with special reference to coarse-

nicinbcr composition iuid interpretation, .hnirmtl of Sedimcittorv

Pcirolo^v. 40: 298-32.\

Aslnnore. P.C. 1991. Hou do gravei-bed rivers braid.' Canadian

Jmmutiof Earth Sciences. 28:

.'126-341.

Bcttess. R.. and White. W.R.. 1983. Meandering and braiding of

alluvitil cliannels. Proceedingsofihe Institution of

Civil

Engineers. 75:

325-538.

Blair. T.C. and McPlicrson. J.G.. 1994. Alluvial Tans and Ilieir natural

disiinction from rivers based on morphology, liydratilic processes,

sedimentary processes, and faeies assembfages. JourntilofSedinicii-

lary Rcmiirli. A64: 450 489.

Blum. M.D., and Tornqvist. T.E.. 2()()t). I-Uivial responses to climate

and sea-level etiange: ii review and look forward. Scilinwiitnlo^v.

47:

2-48.

Brierley. G.J.. and Hiekin. E.J.. 1991. Channel planform as a non-

eoniroHing factor In fluvial sedimentology: tfie case of ihe

Squamisli River floodplain. Brilisli Columbia. Seilinieiitiirv Geol-

ogy. 75: 67 S3.

Brotherion. D.I.. 1979. On the origin and eharacterislics of river

channel patterns, .loiirnatoj llyilrohi^y. 44: 211 -230.

Churefi. M., 1992. Channel morphology and typology. In Calow. P..

and Petts. G.E. (cds.l. The Rivers Haiidhook: Hydrological and

Eco-

higicilPrinciples. Blaekwell. pp. 126-143.

Dalrymple, R.W.. Zaillm, B.A.. and Boyd. R.. 1992. Estuarine faeies

models: eonceptnal basis and straiigraphie implications. Journalof

.Scdiniomirv Petrology. 62: 1130 1146.

DeCelles. P.O.. Gray. M.B.. Ridgway. K.D.. Cole, R.B.. Pivnik, D.A.,

Peqiiera. N.. and Srivaslava. P.. 1991. Controls on syn orogenic

alkivial-fiin archilceture. Bearlooth Conglomerate (Palaeocene).

Wyoming, and Montana. Sedinwritology. 38: 567-590.

Fisk. H.N.. 1944. Geologieal investigation of the ailuvial valley of the

lower Mississippi River Vieksburg. Mississippi River Commission.

78 pp.

Tricnd. P.F.. 1983. Towards the field classitication of alhivial

arehitectiire or seqtienee. In Collinson. J.D.. and Lewin. J. (eds.).

Modern aiul Ancient Elinlal

Sv.\icni.\.

International Association of

Sedimentologists. Special Publication. 6. pp. 345-354.

Friend. P.F.. and Sinha, R., 1993. Braiding and meandering

parameters. In Best. J.L.. and Bri.stow. C.D. (eds.). Braided Rivers.

Geological Society of London. Special Publication. 75. pp. 105-

III.

Gibling. M.R., Nanson, G.C. and Maroulis, J.C, 1998. Anastomos-

ing river sedimentation in the Channel Country of Centra!

Australia. Sedinicntohigy. 45: 595-619.

Gilbert. G.K.. 1877. Report on the geology of the Henry Mountains.

llnited States Geological Survey. Roeky Mountain Region,

Washington. DC

Hiekin. E.J.. and Nanson. G.C. 1975. The character of channel

migration on the Beatton River, north-east British Columbia.

Canada. Gfological Society of Aim-rica Bidletin. 86: 487-494.

Horton. R.E.. 1945. Erosional development of streams and their

drainage basins: hydropliysical approach to quantitative morphol-

ogy. Geological.Society of

.Aincrii

a Bidlfiin. 56: 275 370.

Huang. H.Q.. and Nanson. G.C. 2000. Hydraulic geometry and

maximum How efficiency as producls of the principle of least

action. Earth Sioiace

Processes

and

luiiidform.s.

25: 1- 16.

Jones.

L.S., atid Sehumm. S.A., 1999. Causes of avulsion: an overview.

In Smith. N.D.. and Rogers. J. (eds.). Eluvial Sedimentology \'I.

International Association ofSedimentoloaists. Special Publieation,

28.

pp. 171-178.

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

583

Knighton. D.. 1498. Eiiivial Form and

ProccsM-s:

A New

Per.spcciive.

Arnold. London.

Kraus. M.J.. and Wells. T.M.. 1999. Recognizing avulsion deposits in

the ancient stratigraphie record. In Smith. N.D.. and Rogers, J.

(eds.).

FiiHial .Sedimentology 17. International Association of

Sedimentologists. .Special Publication. 28. pp. 251-268.

Krynine. P.O.. i948. The megascopic study and lield classifiealion ol"

sedimentary rocks. Journalof Cvolof^v. 56: 130 165-

Langbein. W.B.. and Leopold. L.B.. 1966. River meanders- tbeory ol'

minimum variance. L'niiedStatesGfologicalSurvev

Profes.sionaiPa-

per.

422U.

Leopold. L.B.. and Maddock. T.. 1953. The hydranlic geometry of

stream channels and some physiographic implications. United

State.\

Geological .Survey

Professional

Paper.

252.

Leopold. L.B.. and Wolman. M.G.. 1957. River channel patterns-

braided, meandering, and straight. United States

Geoloi>ical .Survev

Profi'.fsiomd

Paper.

Series B. 282. 39 85.

Mackin. J.H.. 1948, Concept of the graded river. GeologicalSocielvof

,-Unerica

Bulletin, 59: 46} 512.

Makaske. B.. 2001. Anastomosing rivers: a review of their classifica-

tion, origin, and seditnentary products. Eartli-Scien<e Reviews. 53:

149 196.

McCarthy. T.S.. Stanistreet. I.G.. Caiiicross. B.. Ellery. W.N., and

Ellcry. K.. 1988. Incremental aggradation on the Okavango Delia-

fan. Botswana. Geoniorphologv. L 267 27K.

Miall. A.D.. 1996. TheGeologyofFimialDeposirs. Springer-Veriag.

Nanson. G.C and Croke. J.C.. 1992. A genetic classification o\'

lloodplains. (iromorpholoiiy. 4: 459-4S6.

Nanson. Ci.C\. and Knighton. A.D.. 1996. Anabranehing rivers: their

cause, character, and elassification. Earlli Siirfaiv Processes and

Landfbrm.s. 21: 217-239.

Posameniicr. H.W.. and Allen. G.P.. 1999. Siliciclastic sequence

stratigraphy-eonecpts and applications. SCPM. Society for

Sedimentary Geology. Concepts in .Sedimentology and Paleonto-

logy. 7.

Richards. K.S.. 1982. Rivers: Form and

Proce.ys

in Alhtvial Channels.

Mcthiien. London.

Schumm. S.A.. 1960. The shape of alluvial channels in relation to

sedimeni type. United Status Geological Survev Professional Paper.

Series B. 352. 17-30.

Scbumm. S.A.. 1973. Geomorpbie thresholds and complex response of

drainage systems. In Morisawa. M. (ed.). FluvialGeomorphologv.

Binghamton. NY: Neu York State University Pnblications in

Geomorphology. pp. 299 309.

Schumm. S.A.. 1977. The FiiivialSystem. Wiley.

Sehumm. S.A.. 1981. Evolution and response to the Iluvial system,

sedimcntologic implications. In Liihridge. F.G.. and Flores. R.M.

(eds.).

Recent and Ancient Nonmarine Environments: Modelsjor i'.v-

ploralion. Society of Eeonomie Paleontologists and Mineralogists.

Special Publication. 31. pp. 19 29.

Schumm. S.A.. and Hthridge. K.G.. 1994. Origin, evolution, and

morphology of tluvial valleys. In Dalrymple. R.W.. Boyd. R.. and

Zaitlin. B.A. (eds.).

Incised-Milley

Sysu-ms:

Orii-in

and.Sedimeniary

Secpiemes. Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists.

Special Publication. 51. pp. II 27.

Schumm.

S..'\..

Mosley. M.P.. and Weaver. W.E-. 1987. Experimental

Fluvial (icomorphology. Wiley.

Smiih. D.G.. and Smith. N.D.. 1980. Sedimentation in anastoitiosed

river systems: examples (Yom alluvial valleys near

Banff.

Alberta.

Journal of Sedimentary Pt'irohi^v. 50: 157 164.

Smith. R.M.H.. 1987. Morphology and depositional history of

c.xbumed Permian point bars in tbe southwestern Karoo. .South

Africa. Journalof Sedimeniarv Petrology. 57: 19 29.

Stanistreet. I.G.. and MeCartby. T.S.. 1993. The Okavango fan and

the classiHeation of subaerial systems. Sedimentary Geology. 85:

115 133.

Wolman. M.G.. and Leopold. L.B.. 1957. River llood plains: some

observations on their tbrmation. United States Geological Survey

Professional

Paper,

^mc^ C. 2^2. pp. HI 109.

Cross-references

Alluvial

I'ans

Anabranehing Rivers

Armor

Attrition (Abrasion). Fluvial

Avulsion

Braided Channels

Debris Flow

Deltas and Estuaries

Erosion and Sediment Yield

I'loodplain Sediments

[•'low

Resistance

Flume

Grain Si/e and Shape

Mass Movement

Meandering Channels

Numerical Models and Simulalion of Sediment Transport and

Deposition

Physics of Sediment Transport: The Contributions o[' R.A. Bagnold

Fluvial Plaeers

Sediment Flu.xes and Rates of Sedimentation

Sediment Transport by Unidirectional Water Flows

Surface Forms

Weathering, Soils, and Paleosois

SABKHA, SALT FLAT, SALINA

The term sahkha (Arabian for salt flat) is used by sedimentol-

ogists to designate an arid, subaerially exposed environment

(typically a salt-encrusted mudflat). The term came into wide

use among sedimentologists following the pioneering studies

of the modern carbonate tidal flat deposits of the arid

Trucial Coast, Persian Gulf (now the Arabian Gulf) by

D.J. Shearman's Imperial College group (Curtis etal., 1963;

Kinsman, 1969; Butler, 1970). The term continentalsabkha has

been used for the arid mudflat of a non-marine closed basin,

better known to students of the closed basins of the western

US as a saline playa (Spanish for "shore" or "beach"). In

South America the term salina is used for a salt-encrusted

mudflat. The factors common to both marine and non-marine

sabkhas are (I) an arid climate, (2) the dominance of subaerial

exposure of the mudflats, punctuated by occasional flooding

(seawater on marine sabkhas and meteoric waters on playas),

and (3) deposition of evaporite minerals (such as gypsum and

halite),

subaqueously in ephemeral "lakes" but in the vadose

zone and as efflorescent surface crusts during periods of

subaerial exposure.

The existing studies of the Holocene Arabian Gulf marine

sabkhas have focused on vadose zone gypsum and anhydrite in

the sabkha environment. Warren (1989, p.38) defines sabkhas

"as marine and continental mudflats where displacive and

replacive evaporite minerals are forming in the capillary zone

above a saline water table". All the spectacularly deformed

layers of nodular anhydrite (enterolithic folds, overthrust and

underthrust ridges, diapiric structures, etc.; see Butler, 1970;

Demicco and Hardie, 1994, figures 160(A-C)) in the Arabian

Gulf are attributed to intrasediment growth of gypsum and

anhydrite (e.g.. Warren, 1989, figure 2.5). While saline

mineralization in the vadose zone is a most significant and

characteristic process in any ephemeral evaporite environment,

the Arabian Gulf sabkha "model", based on vadose processes,

does not include a most important stage in the marginal

marine sabkha depositional cycle, the "gypsum pan" stage.

This pivotal step in evaporite mineral formation in the

"sabkha cycle" is outlined below.

The following description of the formation of bedded

gypsum in a modern marine sabkha environment is based on

observations made on the large (80-100 km^) "ephemeral

gypsum pan" ofthe extensive arid supratidal flat at the south-

west margin of the Colorado River delta, Baja California,

Mexico (Castens-Seidell, 1984; Hardie and Shinn, 1986,

pp.

46-49 and table 1; Demicco and Hardie, 1994,

p.

197).

This active gypsum pan cycles through the following sequence

of stages: a seawater flood stage -> an evaporative concen-

tration stage (ephemeral shallow saline lake) -+ a desiccation

stage (dry gypsum pan) -» a halite pan stage, and back to a

flood stage. The length of each cycle is a function of the

interval between storms (months to a few years). After a major

seawater flooding event the supratidal flat is covered with a

sheet of mud-laden seawater (<l-2m deep). As the flood

finally subsides, most of the seawater drains back to the sea

leaving an isolated sheet of seawater ponded in the shallow

depression (the "evaporating pan") on the supratidal flat.

Deposition begins with a cm-scale layer of silieielastic mud

that settles out over the gypsum bed formed during the last

gypsum pan cycle. This mud layer is soon covered by a

cyanobacterial mat that develops low-amplitude polygonal

undulations as the mat grows. Evaporative concentration

eventually leads to shrinking of the "lake" and the nucleation

of very small aragonite needles and gypsum euhedra at the

brine-air interface, held there by surface tension. As these

surface-nucleated crystals grow, their increasing weight even-

tually leads to their settling to the bottom of the shallow

"lake"

where they act as nuclei for syntaxial bottom growth.

Competitive growth and space constraints favor the vertically-

oriented nuclei, resulting in a subaqueous gypsum layer

composed of an upward radiating array of blade-shaped and

"swallow-tail twin" crystals (e.g., Demicco and Hardie, 1994,

figure

154A).

With progressive evaporative concentration, the

saline lake progressively shrinks, exposing the newly-formed

subaqueous gypsum layer to the hot, dry air. The gypsum of

this subaerially-exposed layer then undergoes diagenetic

modification as evaporative pumping draws brine from the

shallow subsurface brine table (<1 m) up through the vadose