Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SCOUR, SCOUR MARKS

595

they return toward and strike the bed. Particles become

entrained when friction and their immersed weight are

insufflcient to retain them on the bed. Stripping is restricted

to surfaces of soft mud in aqueous environments. It involves

the tearing of clumps of mud from the bed by the direct action

of the current. Depending on the consistency of the bed and

the magnitude of the stress, these clumps range in size from

tenuous wisps a few millimeters across to plumose-marked

plastic lumps measured in decimeters, Corrasion sees the

removal of material from the surface by the action of fluid-

driven debris, which either pounds the bed or chisels fragments

from it, depending on its size and the strength of the bed.

Generally speaking, corrasion affects materials—stiff or dried

muds and rocks—which are too strong to be removed by

stripping. The tools available to currents are various: sand

grains, gravel, shells and even pieces of ice.

From a genetic standpoint, scour marks may for conve-

nience be grouped into two largely distinct classes, termed

current-excited and defect-excited. Current-excitedscourmarks

are those which result when a bed is affected by an imposed,

stationary pattern of eurrents, for example, a seeondary flow,

which create over the bed a corresponding variation in the

value of the shear stress or the concentration plus effectiveness

of any transported tools. There is no requirement for any

significant inhomogeneity in the consistency ofthe bed. Defect-

excited seour marks are those which arise when a eurrent flows

over a bed containing some gross, localized iregularity or

defect. Some defects stand bluff to the eurrent, for example, an

upright plant stem, a pebble or shell, a block of stranded ice,

or a half-emergent concretion. Others are negative features

that reach down from the surface, for example, an open

invertebrate burrow on the sea bed, or shrinkage cracks on a

surface of dried mud awaiting the next river flood. In all of

these cases, the defect creates around itself a pattern of

currents which lead to differential scour. Of course, no real

surface acted on by a current can be perfectly homogeneous,

and it is therefore possible for an unstable interaction between

the surface and the current to arise which, in the long term,

creates a pattern of scour and a corresponding set of

apparently organized forms. Strictly, such scour marks are

defect-excited, but the defects in such cases were never gross

and remain unseen.

Scour marks are a diverse group and have been reported and

discussed from many different environments in a very

considerable literature (Allen, 1982b), The main types are as

follows:

Current-excited scour marks

gutters and gutter casts

ridges-and-furrows (wind)

yardangs

furrows-and-ridges (wave-related)

Defect-excited scour marks

current crescents

flute marks

potholes and pothole casts

Gutters, fossilized as gutter casts, are sets of long, occasionally

branching, flow-parallel furrows, and ridges found where

eroding river and tidal currents drive coarse debris over

surfaces of mud and occasionally gravel or rock. Typically, in

fluvial, intertidal and shallow subtidal depths, their transverse

spacing ranges between a few decimeters and a few meters, and

the sides may overhang. There is evidence that they are

localized by secondary currents (paired corkscrew vortices)

which concentrate the bed-material in transport into flow-

parallel bands, but single gutters could be defect-related,

Depositional events, mainly on the ridges, commonly make a

modest contribution to the relief of the intertidal forms. In

subtidal environments such as the English Channel, where

depths measure tens of meters, the grooves occur in sandy-

shelly gravels. They have a characteristic transverse spacing of

the order of 100 m, and may be many hundreds of meters long,

Entrainment is probably the chief mechanism involved in their

formation.

Sets of flow-parallel ridges-and-furrows occur in deserts,

chiefly the Sahara, where vigorous, sand-laden winds of

roughly constant direction are able to corrade comparatively

level and uniform rock surfaces. They are probably related to

the sets of corkscrew vortices that form in the thick

atmospheric boundary-layer when thermal instability occurs,

Ridges-and-furrows are huge structures found over vast areas.

In depth they range from a few to many meters, lie hundreds of

meters apart parallel with the wind, and take extreme lengths

of tens of kilometers. As their length shortens, ridges-and-

furrows grade into the desert landforms known as yardangs.

These are comparatively short ridges of lemniseate plan, the

bluff end facing the wind, which arise where comparatively

soft materials, such as mudstone, diatomite or friable

sandstone, are subject to corrasion, Erosional forms similar

to yardangs have been shaped by extreme floods, on both the

Earth when ice-dams have broken and, apparently, in the past

on other planetary bodies.

Wave-related furrows-and-ridges are found on muddy

shores in erosional retreat, sueh as some saltmarsh edges,

and on intertidal rock platforms at the feet of cliffs. In the first

of these contexts, where the term mud mound is often applied,

they appear as sets of furrows and commonly overhanging

ridges arranged at right-angles to the shore. Typically, the

sides ofthe ridges are striated, and the tools responsible for the

corrasion, chiefly pebbles and shells, are visible on the floors of

the furrows. The transverse spacing of the structures, ranging

from a decimeter or so to a few meters, appears to increase

with the degree of exposure of the shore to wave aetivity,

supporting the idea that furrows-and-ridges reflect the complex

current patterns due to edge waves. Also oriented at right-

angles to shore are the furrows-and-ridges that can occur at

the feet of cliffs. Less is known about them, but they are

similar to the structures developed in mud and may have the

same origin.

Current crescents are defect-related scour marks that form

because of stripping and/or corrasion around bluff bodies in

fluvial and tidal environments and, occasionally, in deep water

where turbidity currents operate. The body has a number of

effects (Paola etal., 1986), Firstly, it compresses the current

around the sides, enhancing its erosive powers. Secondly, the

flow decelerates ahead of the body, resulting in the separation

of the flow from the bed and the creation of a vigorous, cork-

screwing vortex which curves around the front and sides ofthe

body. Thirdly, on the downstream side a sluggish wake is

formed in which the rate of erosion is much reduced. The

overall result is a U-shaped groove which encircles the front

and sides ofthe body, in the lee of which a dagger-shaped ridge

may be found.

Frequently formed by turbidity currents as they drive over

mud beds, and occasionally fashioned by river floods, flute

596

SEAWATER: TEMPORAL CHANGES IN THE MAJOR SOLUTES

marks are probably the commonest and most widespread of

scour structures. They are horseshoe-shaped depressions

centimeters to decimeters long with arms that open out

downcurrent. Typically, they occur in dense groups and are

preserved as casts on the undersides of sandstone beds.

Experimentally, flute marks are generated most readily by

stripping and/or corrasion at negative defects, such as the tops

of burrows or shrinkage cracks. Flow separation occurs along

the upstream edge of the defect, with the result that enhanced

turbulence is advected to the downstream side, where the flow

reattaches. The erosion rate is greatest here. Consequently, the

defect gradually evolves through differential erosion into a

horseshoe-shaped hollow which is symmetrical about the line

of flow. Each mature flute mark contains a well-established

separated flow, similar to that found in the lee of many sand

ripples and dunes. If a surface is scattered with defects, a field

of intersecting flute marks can quickly become established.

However, a single, isolated flute mark when mature can trigger

the formation of secondary marks.

Potholes have most often been reported from powerful

rock-bound rivers, but are also known from river floodplains

and even intertidal and shallow-marine environments where

mud beds can be affected. Wave-action alone may generate

them in the marine realm. Fossilized as pothole-casts, they

range from shallow hollows to deep, steep-sided shafts drilled

into the substrate by the action of swirling masses of sand and

gravel which corrade the surface. Potholes range in size from

a decimeter or so wide and deep to giants with depths in the

neighborhood of 20 m and widths of about

10

m, They

seem almost invariably to be initiated at defects in the

substrate, such as minor faults, joints or shrinkage cracks.

Potholes in fluvial environments are economically important,

for when being filled with sediment, they act as traps for placer

minerals.

Scour marks record the fact that surfaces affected by

aqueous currents or the wind can experience differential

erosion reflecting either patterns of flow and fluid force

existing in the current or patterns excited in the current by

the presence of some gross irregularity of the bed. Most have

directional properties which can be used to infer ancient

current directions,

John R,L, Allen

Bibliography

Allen, J,R,L,, 1982a, Sedimentary Structures: Their Character and

Physical Basis. Volume 1, Elsevier,

Allen, J,R.L,, 1982b, Sedimentary Structures: Their Character and

Physical Basis, Volume 2, Elsevier,

Paola, C, Gust, G,, and Southard, J,B,, 1986, Skin friction

behind isolated hemispheres and the formation of obstacle marks,

Sedimentology, 33: 279-293,

Cross-references

Bedding and Internal Structures

Paleocurrent Analysis

Parting Lineations and Current Crescents

Surface Forms

SEAWATER: TEMPORAL CHANGES IN THE

MAJOR SOLUTES

Introduction

The exceptional paper by Rubey (1951), entitled "Geologic

history of seawater; an attempt to state the problem",

crystallized thought concerning the factors affecting seawater

composition. After review ofthe available information, Rubey

concluded that the composition of seawater had varied within

narrow limits over much of geological time. The systematic

nature of his approach and the strength of his arguments

resulted in a 50-year consensus that the conclusion was correct.

His arguments did not preclude temporal changes to minor

and trace solute contents and there are numerous recent papers

which indicate that minor and trace element compositions of

seawater varied over time (deRonde etal., 1997; Cicero and

Lohmann, 2001),

The arguments of Rubey were sufflciently persuasive that

only the "more profltable" lines of evidence were pursued and

documented in detail until recently, Canfield et al. (2000)

challenged Rubey's conclusion by presenting evidence that

sulfate was low in Archean seawater and had increased in

abundance since about 2,5 Ga. The conclusion, however, was

most strongly, and convincingly challenged by Lowenstein et

al. (2001) who demonstrated that Mg/Ca ratio varied between

latest Precambrian time and the present, and that the variation

was sufflcient for aragonite rather than calcite to have

precipitated from seawater. These Mg/Ca variations result

primarily from the rates of generation of oeeanic crust through

which seawater circulates via thermally driven convection cells

(near oceanic ridges). The greater the rate of seafloor

generation, the greater the amount of interaction with oceanic

crust and the higher Mg/Ca in seawater.

Generation of oceanic crust and implications concerning

seawater composition were not considered by Rubey, primar-

ily because such concepts awaited elucidation some 30 years

later (Edmond etal., 1979; Sleep etal., 1983; Thompson, 1983),

These ideas coupled with the study of Lowenstein etal. (2001)

and Canfield etal, (2000) demonstrate that the concentrations

of the major solutes of seawater varied through the Proter-

ozoic and Phanerozoic Eons. There is also evidence that its

composition varied appreciably through the Archean Eon,

Following Rubey, "lines of evidence" for continual change to

major solute contents of seawater are developed here.

Unfortunately, the dearth of reliable information (and detailed

study) prevents firm conclusions from being drawn about

seawater compositions during early periods.

Major solute fluxes to the seawater reservoir

Rubey was unaware of the important role that oceanic

crust-seawater interactions had on seawater composition.

Neither was he aware of recent findings concerning the

compositional evolution of the crust because fundamentally

important aspects of its evolution, now apparent, were

unknown 50 years ago. The arguments of Rubey (1951)

concerning seawater composition are reconsidered in light of

recent findings regarding geochemical cycles,

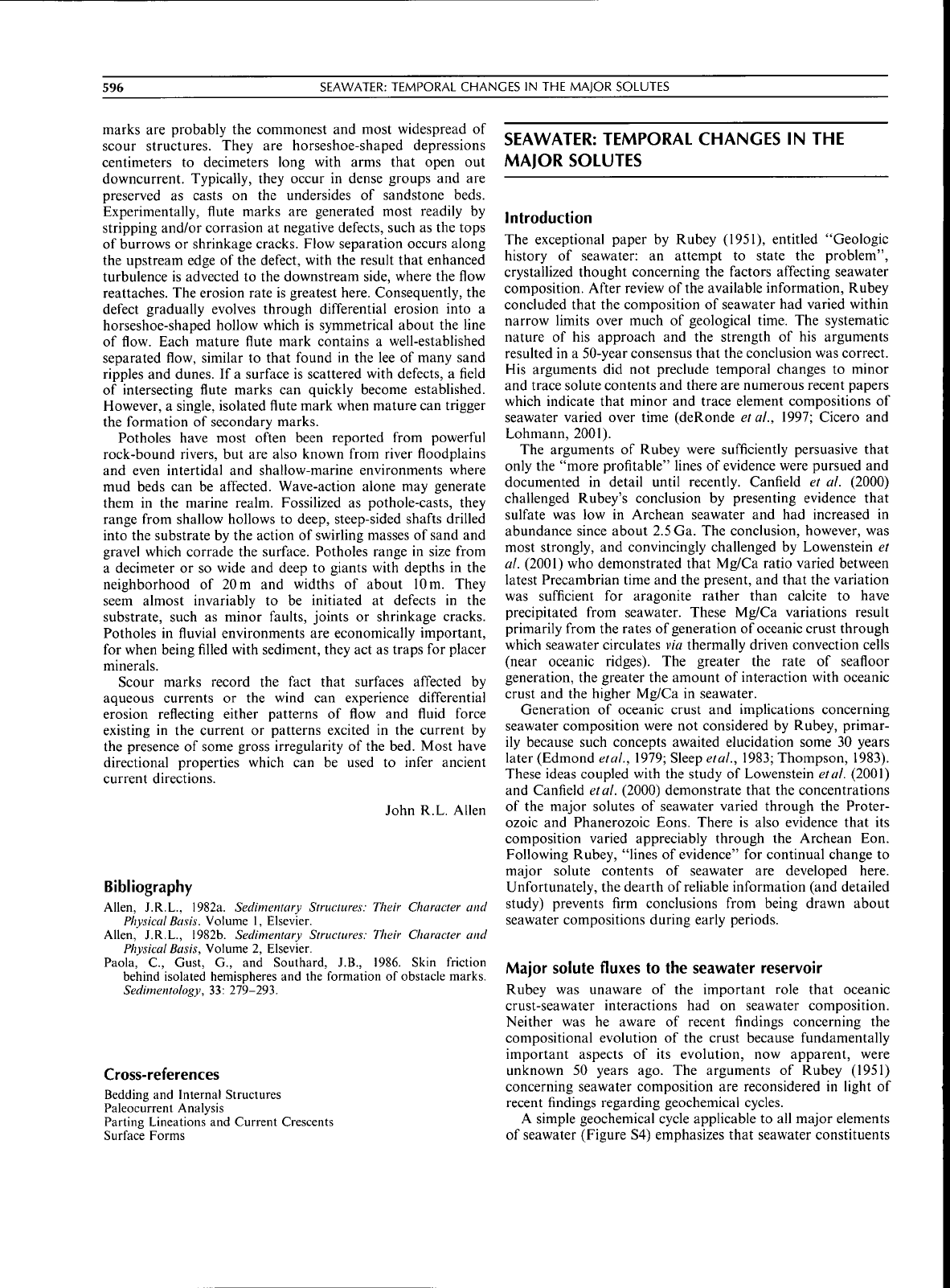

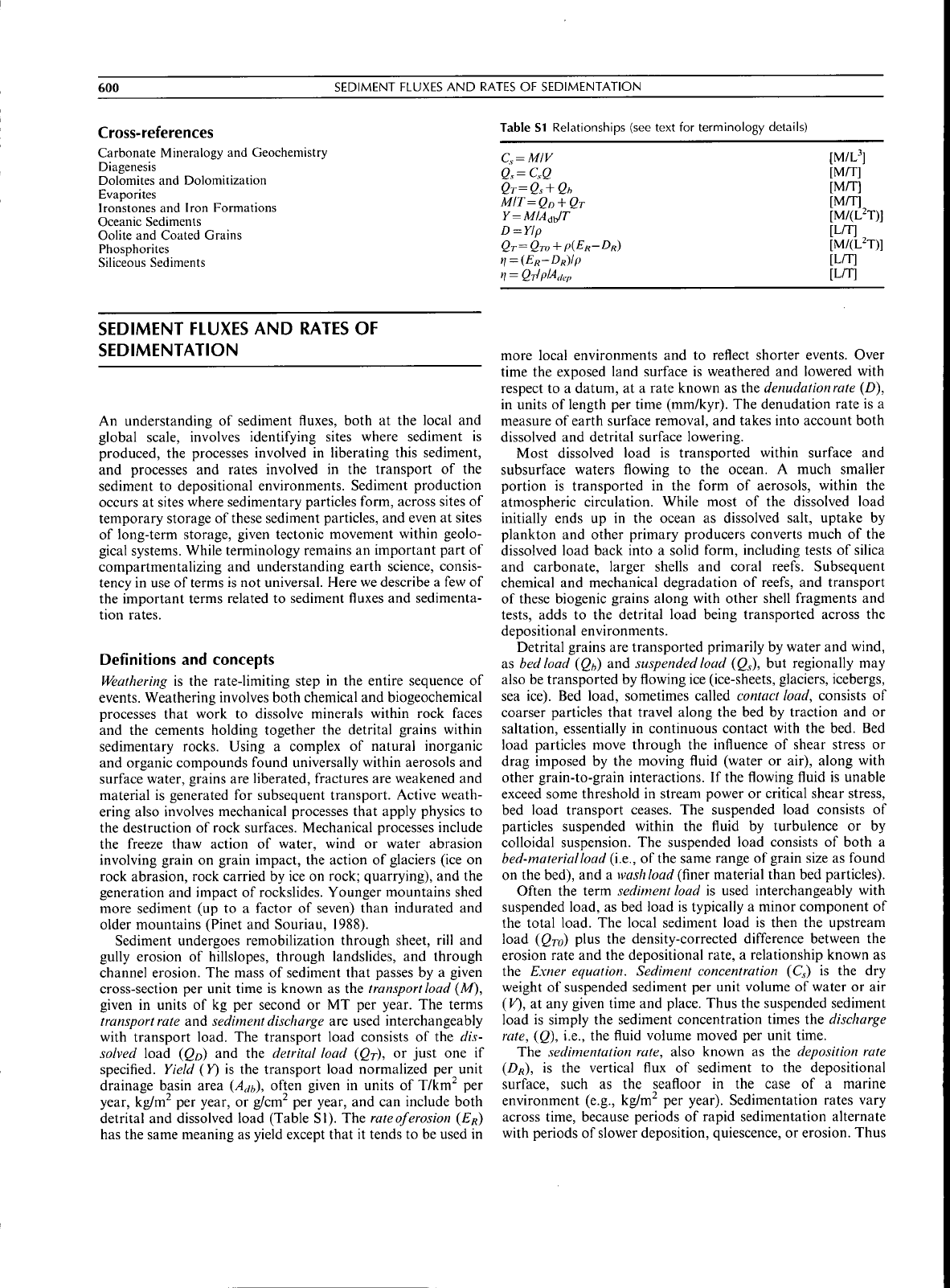

A simple geochemical cycle applicable to all major elements

of seawater (Figure S4) emphasizes that seawater constituents

SFAVVATER: TEMPORAI ("HAN(-ES IN THE MA|ORSOIUTES

.597

Meteorites

&

Comets

Figure S4 tieochemital tycle applicable to the mdjor solutes of

stMw.iter.

F.ieh

box represents a sepdr,ite reservoir and each arrow a

llux (labelled "E"!. The contribution trom each reservoir and the

majjnitude of each flux differs tor each major solute. Tho thicker

arrows indicate fkfxes importtint to major solutes, although this is a

generalization.

are derived tVoni

the

continental crust, cieeanie crusl,

and the

mantle. Details

of the

mantle-

and

oceanic crust-seawater

solute tluxes have been addressed recently (Edmond

et al..

1979:

Sleep etal..

198.1;

Thompson.

]9^?:

Wolcry

and

Sleep.

I98S;

Lowenstein etal.. 2001).

The

eontinental crust

is the

single largest source

tor

solutes today

and

rnay have been

in

the past (Berner

and

Berner. 1996).

and of

these lin.xes (Kigure

S4.

h\. F4. Fs)

river water tluxes

(FO are the

greatest (Berner

and Berner, 1996).

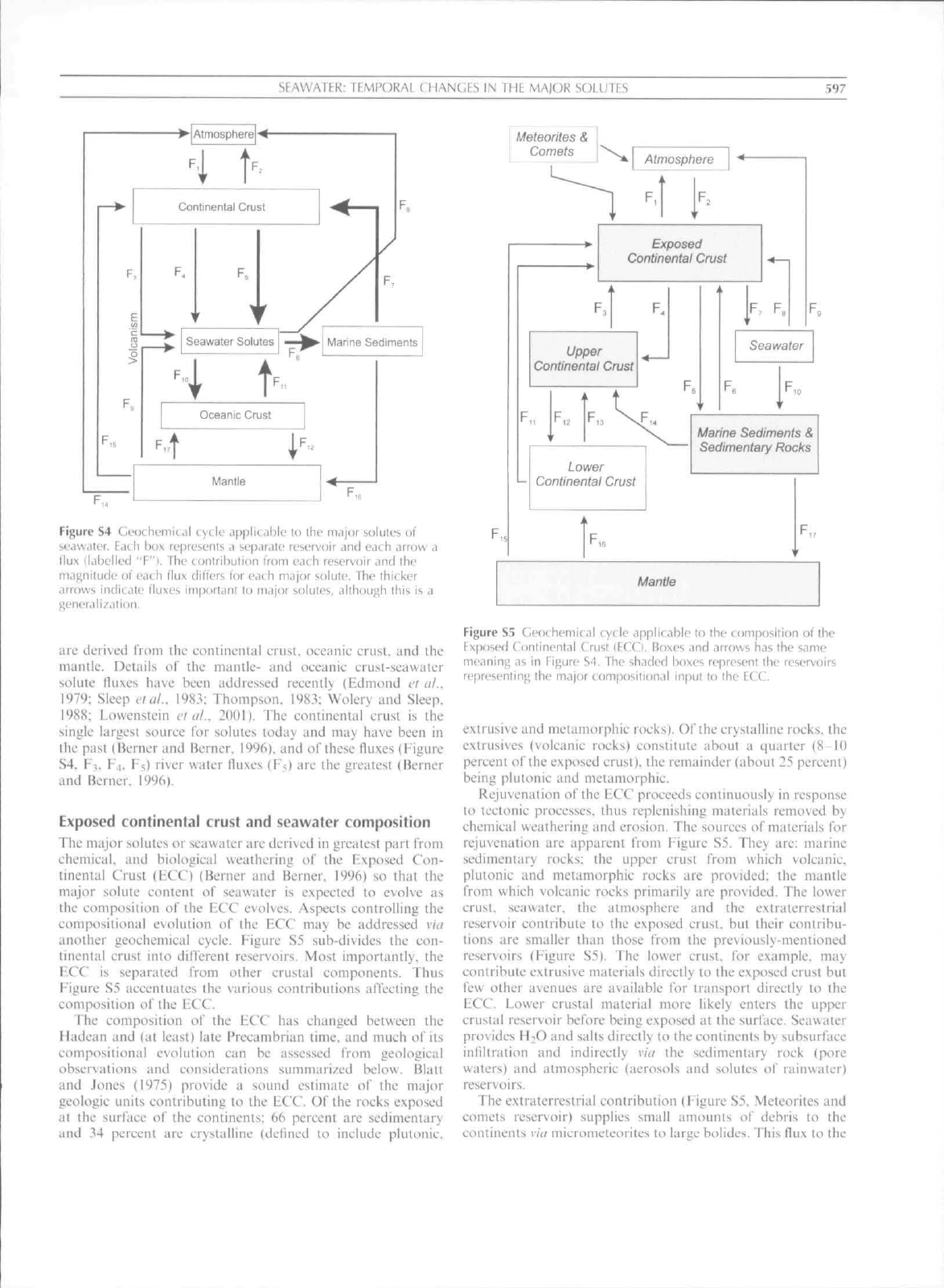

Exposed continental crust

and

seawater composition

The tnajor solutes

or

seawater

are

derived

in

greatest part from

chemical,

and

biological weathering

of the

Fxposed

Con-

tinental Crust

(ECO

(Berner

and

Berner,

1996) so

that

the

major solute eontent

of

seawater

is

expected

to

evolve

as

the composition

of the ECC

evolves. Aspects controlling

the

eompositionat evolution

0!' the ECC may be

addressed

via

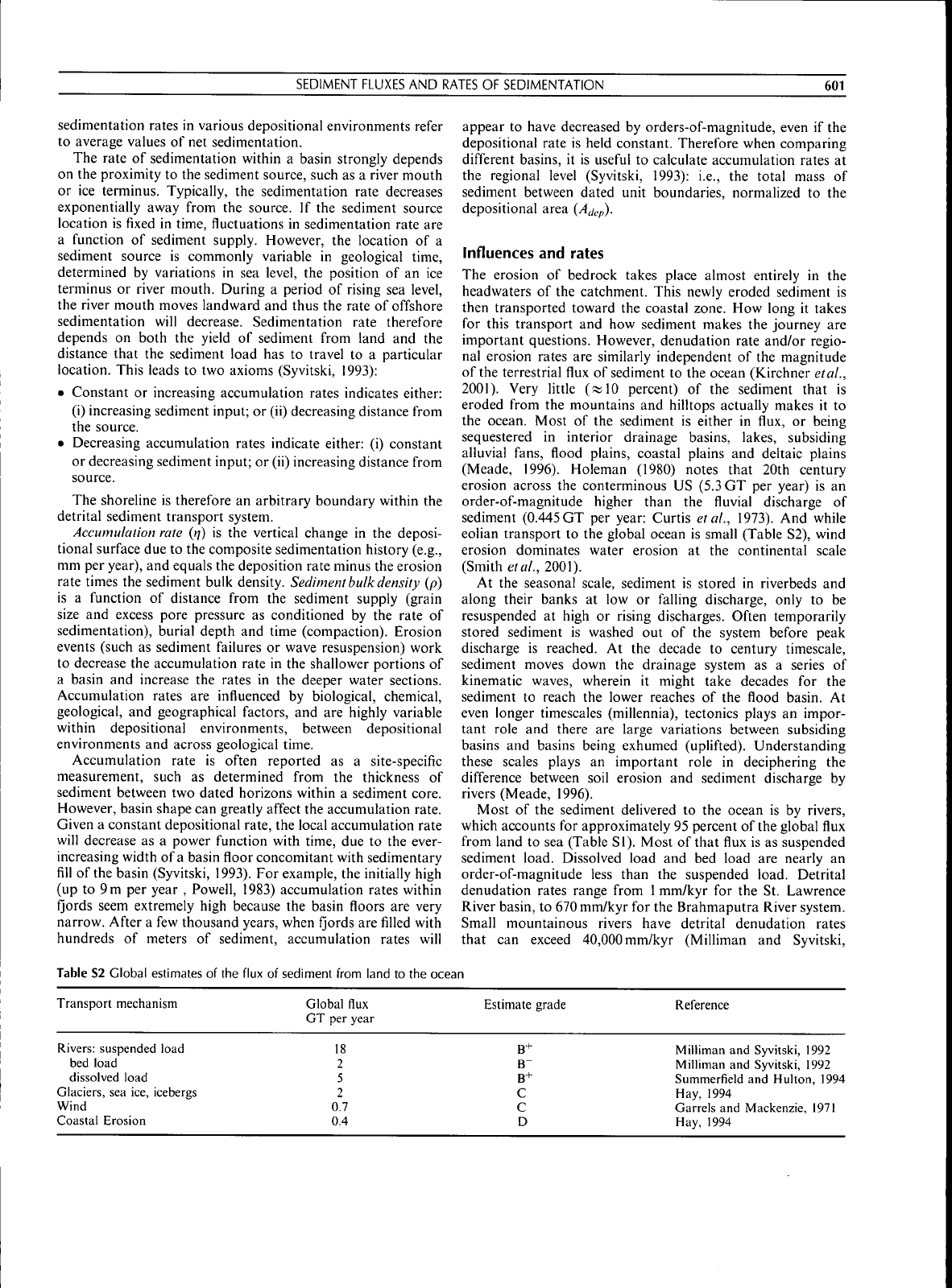

another geoeheniieal cycle. Figure

S5

sub-divides

the eon-

tinental crust into different reservoirs. Mosl importantly,

the

ECC

is

separated from other erustal eomponents. Thus

Figure

S5

accentuates

the

various eonlribnlions iiffeeting

the

eomposition ofthe

ECC.

rhe cotnposition

of the ECC has

changed between

ihe

Hadean

and (at

least) late Precambrian titne,

and

much

of its

eompositional evolution

ean be

assessed from geologieal

observations

and

eonsiderations summarized below. Blatt

and Jones (1975) provide

a

sound estitnate

of the

major

geologic units contributing

to the ECC. Of the

rocks exposed

at

the

surfaee

of the

continents:

66

pereent

are

seditnenlary

and

14

percent

are

erystalline (defined

to

include pUitonie.

Atmosphere

~1

F,

I

F.

Exposed

Continental Crust

Upper

Contirientat Crust

F,,

F.,

Seawater

Lower

Continental Crust

Marine Sediments

&

Sedimentary Rocks

Figure S5 Geo( hemical cycle applicable to the composition ot the

Exposed Continental Crust lECCl. Boxes and arrows has the same

meaning as in Eigure S4. The shaded boxes represent the reservoirs

representing the major compositional input to the ECC.

extrusive

and

metatnorphic rocks).

Of

the crystalline rocks,

the

extrusives (voleanie rocks) constitute about

a

quarter

(H 10

percent ofthe exp(*sed crust),

the

retnaitider (about

25

pereent)

being plutonic

and

metamorphie.

Rejuvenation ofthe

ECC

proceeds eontinuously

in

response

to tectonie proeesses, thus replenishing materials removed

by

ehetnical weathering

and

erosion.

The

sourees

of

materials

for

rejuvenation

are

apparent iVom Figure

S5.

They

are:

marine

sedimentary rocks:

the

upper erust frotn which voieanie,

piutonic

and

tnetamorphie rocks

are

provided:

the

mantle

frotn which volcanic rocks primarily

are

provided.

The

lower

erust, seawater,

the

atmosphere

and the

extraterrestrial

reservoir contribute

to ihe

exposed erust.

but

their contribu-

tions

are

smaller than those from

the

previously-mentioned

reservoirs {Figure

S5). The

lower erust,

for

exarnple. tnay

contribute extrusive materials directly

to the

exposed erusi

but

few other avenues

are

available

for

transport directly

to the

ECC.

Eower erustal malerial tnore likely enters

ihe

upper

erustal reservoir before being exposed

at the

surface. Seawater

provides H^O

and

salts direetly

to the

eontinents

by

subsurfaee

inftltration

and

indirectly

via the

sedimentary roek (pore

waters)

and

attnospherie (aerosols

and

solutes

of

rainwater)

reservoirs.

The extraterrestrial contribution (Figure S5. Meteorites

and

eomets reservoir) supplies small amounts

of

debris

to the

eontinents r/</ mierometcorites

to

larce bolides. This flux

to the

598

SFAVVATFR: TFMPORAl. CHANCES IN THE MAJOR SOLUTES

ECC is now negligible but must have been important during

the first tew hundred Mil ot" Earth history.

Temporal compositional changes to the ECC

The sedimentary rock reservoir includes carbonates, sand-

stones and shales. Their proportions exposed at the surface

likely is similar to their abundance in the rock record,

measurements and estimates of which lead to evaporite: sand-

stonexiirbonale: shale proportions of 3:15:20:(i2 (Garrels

and Mackenzie, 1971. p.2O6. p.247 and p.249). Because they

represent 66 percent ot" the ECC. and because the ECC is the

major contributor to seawater composition, a change in

sedimentary rock proportions likely would be reflected in

seawater composition. There are well recognized temporal

changes to the sedimentary rock reservoir (Vinogradov and

Ronov. 1956: Garrels and Mackenzie. 1971; Veizer, 1979.

1985;

Godderis and Vei/er. 2000) and sympathetic changes to

seawater composition almost certainly have occurred.

Sedimentary rock-ECC fluxes

The devclopmcni of large sedimentary platforms and deposi-

tion of compositionally mature platformal sediments com-

menced at about 3 Ga. the Witswatersrand, Pongola and

Buhwa platforms being examples (Eedo etal.. 1996). Platform

development was diachronous and extended beyond the end of

the Archean (2.5 Ga). The first extensive plattbrmal sequence

associated with the Canadian Shield is the Iluronian sequence

(Young. 1995) with an age no older than 2.3 Ga.

Addition of a mature sedimentary rock platfomial "blan-

ket" to the exposed continents near the end of the Archean

should have changed appreciably the rate of supply of solutes

to streams and to seawater. These changes to rates ol'supply

likely resulted in changes to the major alkali and alkaline earth

solutes of seawater. Mature siliciciastic sediments are depleted

of Na, K, Mg. and Ca relative to the crystalline or volcanic

rocks exposed at the surface. Seawater Na. K. and Mg likely

declined in abundance as these weathered materiais covered al

least half of the previously exposed crystalline rocks (prevent-

ing their weathering).

Mantle-ECC fluxes

The mantie supplies materials to the ECC via volcanism

primarily, producing large volcanic fields and "basaltic

plateaus". Extrusive rocks today represent about 8-10 percent

of the exposed crust but as Blatt and Jones (1975) emphasize,

their eontribution to marine sediments probably is double this

value (contributes 15-20 percent to the sedimentary reservoir).

Cheniical weathering of volcanic materials is rapid and they

should yield solutes to stream and river waters at a rate akin

to the rate of production of detritus from the ECC (at least

15-20 percent of seawater solutes supplied by weathering and

erosion of mantle-derived volcanics).

The nature of mantle volcanic materials supplied to the

ECC has changed over time. Komatiites are tbund in Archean

volcanic sequences but are absent from volcanic sequences of

younger age. With the ehange in mantle input to the ECC,

seawater eomposition likely changed in response. The high Mg

content and the labile nature of the constituents of komatiites

and high Mg-basalts volcanic rocks probably affected Ca. Mg.

and Si contents of seawater, and its salinity may have been

greater during the Archean.

Veizer (1979) noted that the sedimentary rocks arc

considerably more mafic (on average) than average upper

crust. He argues that this was due to an early mafic ultramafic

crustal component being added to. and recycled within the

sedimentary mass. Veizer estimated that aboul 30 percent of

oceanic basalt would have to be added to 70 percent upper

continental crust to generate compositions consistent with the

sedimentary roek eompositions. The fmding attests to the

temporal changes to the ECC resulting from mantlc-ECC

interaction.

Continental crust-ECC fluxes

Theories fov genesis of continental crust can be grouped into

three categories: (1) homogeneous accretion: (2) inhomoge-

neous accretion: (3) terrestrial models (Condie. 1989). Brown

and Mussctt (1981) summarize arguments related to the first

two groups and both imply development of a crust during

accretion (before the first 300 Ma of Earth history). Much

study has been focused on terrestrial models. They consist of

two groups, those based on the assumption that the majority

of the crust evolved very eariy without its volume having

ehange greatly over geological time (Armstrong. 1968: Fyfe.

1978;

Rudniek. 1995; Sylvester etal., 1997) and those based on

the assumption that the early crust was initially of small

volume and that its volume increased over time, perhaps

dramatically at approximately 2.5 Ga (Godderis and Veiser.

2000).

Models of all types have associated ambiguities and

inconsistencies and little can be concluded with certainty. The

moon, however, has an anorthositic crust which formed prior

to,

or early during, the late heavy bombardment (3.8 Ga). If

the moon and Earth are genetically related as commonly

proposed (Taylor, 1997). the Earth almost certainly generated

a crust (perhaps anorthositic.') at the same time as {or before)

the moon. If the initial crust were primarily anorthositic its

weathering would have produced solute contents much

dilTerent from present-day seawater.

Taylor and McLennan (1985) conclude that the Archean

crust was compositionally different from the post-Archean

crust, the dramatic change occurring near 2.5 Ga. although

recognized to be diachronous. The change was from a

dominantly plagioclase. quartz and mafic minerals-dominated

Archean crust to a post-Archean crust which included K-rich

granites.

As pre\ious!y noted, the upper continental crust constitutes

about 25 percent of the ECC but must have been as much as

50 percent of the ECC prior to 2.5 Ga. Development of

sedimentary platforms bordering continents and their sub-

sequent exposure (incorporation into the ECC reservoir),

coupled with the simultaneous decrease in the amount of

exposed crystalline crust, must have had significant effect on

the eomposition of seawater during the period since about

3Ga. Canfield ft al. (2000) corroborate the conclusion; they

demonstrate that sulfate content was low during the Archean

but increased to present levels beginning at about the

Archean Proterozoic transition (about 2.5Ga).

Extraterrestrial-ECC fluxes

The history of the Hadean Eon (4.5Ga to 3.8Ga), although

highly speculative, has been deduced in some detail (Taylor.

SEAWATER: TEMPORAL CHANGES

IN IHt

MA)OR SOLUTES

599

1997). Noble gas ratios and abundances indicate that the

present atmosphere and hydrosphere arc secondary (Cogley

and Henderson-Sellers. 1984; Taylor. 1997), The implication is

thai the hydrosphere developed eilher during accretion (til'ter

separation oflhe Moon) or between aboul 4.2Ga and 3.8Ga.

the period of ""late heavy bombafdmcnf,

I("

ihc crust formed

during accretion ils composition would have been modified by

incorporation of material captured during the late heavy

bombardment. Taylor (1997) summarizes the effects on the

composition ofthe mantle of such capture . By analogy, there

must have been similar or greater compositional effect on the

iippLT crust and on the ECC. These materials probably were

derived from mclcorites of carbonaceous chondritic composi-

tion Ol- from comets (Chyba. 1990: Taylor. 1997). both of

which contain appreciabk- amounts of water (generally greater

than lOwt. perccnl. Brown

etaf.

2000). If ECC composition

were affected by the "late heavy bombardment" then seawater

composition undoubtedly would have been affected by the

extraterrestrial Input. The effects of such contributions await

studv.

Summary

There is compelling evidence thai seawater composition has

changed continuously during the entire history of the Earth.

Compositional change probably was rapid during the transi-

tion from the Hadean Eon through the tate heavy bombard-

ment and into the Precambrian Era. Changes to the

composition of the upper continental crust during the late

Archean likely caused change to the major solute concentra-

tions of seawater. The development of stable platforms during

the laic Archean and Prolerozoic, and the incorporation of

chemically malurc piaUbrmal sedimentary rocks into the

Exposed Continental Crust (ECC) must have resulted in

change to seawater composition. Canfield et al. (2000)

demonstrate that sulfate content has changed during the

Proterozoic Eon and Lowenstein etal. (2001) demonstrate

major solute changes during the Phanerozoic Eon.

Chloride has the longest residence time of any major

element in the oceans (about 100.000 years; Berner and

Berner. 1996), Ba,sed on this residence lime, major constiluents

of seawater may achieve steady state within 100.000-300.000

years. Some trace constituents may take longer to achieve

steady state (e.g.. Br) in part because their crustal abundances

may vary much more. Although seawater has evolved

continuously over geological time, an essentially steady state

composition may have been achieved many times, the steady

stale composition likely being differenl during each steady

state stage.

H, Wayne Nesbitt

Bibliography

Armstrong.

R.L., 1%S. A

model

for Sr and Pb

isoiopc evolution

in :i

dynamic Eiirlh, Reviews in

Geophysies.

6:

175-199,

licriKT.

K,r,.

iiiui Berner,

R,A,. 1996,

Glohal Einironmeiit. PrL-nliue

Hall,

[iliiu.

M.. and

Jones.

R.L,. 1975,

Proportions

of

exposed igneous.

metamorphii:,

and

seditnentary rocks, Eeolo^icalSocietyi>fAmerica

Bulletin. 81:

255 :d2.

Brown. G,C,,

and

Mussctt. A,F.. 1981, The

Inaeces.sihle

Earth, L'nwin

Hyman

Ltd,

Hiowii,

P,G,.

ffildcbrand,

A.R,. and

/oL-nsky,

M,E.

etal.. 2000,

Tlie fall, recovery, orbit

and

composition

of

tlic Tagish Lake

meteorite:

a new

type

of

carbonaceous chondrite. Science.

290:

?20

324,

Canticld. D,E,. Habicht, K,S..

and

Thiimdrup. B,. 2()(H), Tlic Archean

suifur cycle

and the

early hi.story

of

atmospheric oxygen. Science.

288:

658

661,

Chyba. CF,. IWO, Impact delivery

and

erosion

of

planetary oceans

in

the early inner solar system. Nature. 343:

129 \^y.

Cicero. A.D,.

and

Lohmann. K.C. 2<)()L Si7Mg variation during rock-

water inier:iclion: implicalions

for

secular changes

in

t!ic elemental

chemistry

of

ancient seawater, Geochiniica

el

Cosmochimica .Aeta.

65:

741-76L

Cogley. J,G,.

and

Henderson-Sellers.

A,.

1984,

Ihc

origin

and

earliest

state oflhe Earth's hydrosphere. Reviews

of

Geophvsics

and

.Space

Phy,sics.

22: 131 175.

Condie.

K.C 1989,

Plate Teclouics

and

Cruslal Evolution- Oxford:

Pergamon Press,

deRonde. CE.J., Channer. D,M,DeR,, haure,

K,.

Bray,

CL. and

Spooner, E.T.C..

1997,

Eluid chemi.stry

of

Arehcan seaHoor

hydrothermal venls: impliealions

tor the

composition

of

circa

3,2Ga scawaici. Geochiniicacl Cosniochiniica

Ada.

61: 4025-4042.

Edmond, J.M,. Measures.

C.

McDtilT.

R.E,.

Chan. L,H,. Collier.

R..

Grant.

B,.

Gordon,

L.J., and

Corliss.

J,B,, 1979.

Ridge crest

hvdrothermal activity

and [he

balances

of the

major

and

tniiior

elements

in the

ocean:

ihe

Galapagos data.

Ecirih

and

Planetary

.Science Letters.

46: 1-18,

r-edo.

CM,.

Eriksson. K,A,.

and

Krogstad.

E.J,.

1996, Geoehemistry

of shales from

the

Archean (5,0Gii) Buhwa greenstone belt.

Zimbabwe: implicalions

for

provenance

and

source-area weath-

ering, Geoehimicael Cosnioehiniica

.4eia.

60:

1751-1763,

l-yle.

W,S,. 1978. The

evolution ofthe Earth's crust: modern pbte

tectonics

to

ancient

hot

spot tectonics. Chemical Geology.

23:

S9-II4,

Garrels.

R,M,, and

Mackenzie.

F,T,, 1971,

Evoluiion

ii}

Sediineniury

Rocks,

New

York: Norton

& Co.

Goddcris.

Y,, and

Veizer,

.1..

2000, Tectonic control

of

chemical

and

isotopic eomposition

of

ancient oceans:

the

impact

of

continental

growth,

Ameri<

an Journal

('/.Science,

300:434

461,

Lowcnstcin.

T,K,,

Timofectt,

M.N.,

Brennan.

S,T,.

Hardie. L.A..

and

Demicco,

R,V,. 2001,

Oscillations

in

Phanerozoic seawater

chemistry: evidence from fluid inclusions. Science. 294: 1086- lOSX.

McLennan.

S.M,. and

Taylor,

S,R,, 1991,

Sedimentary rocks

and

crustal evolution: tectonic setting

and

secular trends, Jouriutl

of

Geology.

99: 1-21,

Rubey, W,W,. 1951, Geologic history

of

seawater:

an

attempt

to

stale

the problem. Bulletin

o) ihe

Geoloiiical .Society

of

America.

62:

nil

1147,

Rudnick.

R.L.,

1995, Making continental crust, \aiitre. 378: 571-578,

Sleep.

N,H,.

Morton,

J,L,.

Burns.

L,E.. and

Wolcry.

T,J.. 1983.

Geophysical constraints

on the

volume

of

hydrothermal flow

at

ridgf axes.

In

Hydrothermal

Proces.sesal

Seajloor Spreading Centers.

Plenum Press. NATO Conference Series 4,' Volume

12: 53 70.

Sylvester.

P.J..

Campbell.

LIf,. and

Bowyer,

D.A,, 1997,

Niobium/

Uranium evidenee

for

early formation

of the

continental crust.

Science. 115\ 521-523.

Taylor,

S,R,,

1997,

The

origin ofthe Earth, Journalof Ausiraliun Geol-

ogy and

Geophysics,

17:

27 31.

Taylor,

S,R,. and

McLennan.

S,M.. 19K5, The

Cionincnutl Crusi.

Its

Composilion andFvoluiioti. Blackwell Scientific Publishers,

Thompson.

G,, 1983,

Basah-seawater reaction.

In

HydrolhermalPro-

cesses

al

Seafioor Spreading Centers. Plenum Press. NATO

Conference. Series

4.

Volume

12. 225 278.

Veizer.

J,. 1979,

Secular variations

in

chemical composiiion

of

sediments:

a

review.

Physics

and Chemistry of ihe Farlh. 11:

269.

Vei/er.

J,. 1985,

Basement

and

sedimentary recycling,

2.

time

dimension

to

global tectonics, Jintrnali>fGeology. 93:

624 643,

Vinogradov,

A,P,. and

Ronov,

A.B., 1956.

Composition

of the

sedimentary rocks

of the

Russian Ptallorm

in

relation

to the

history

of its

tectonic movements, Geochemislry.

6: 533 559,

Wolery. T,J..

and

Sleep. N.H,, 1988, Interactions

of

geochemical cycles

with

the

mantle.

In

Chemical Cycles

in the

Evohuion

of

ihe

Earth.

John Wiley,

pp. 77 103,

Young,

G,M,. 1995, The

Huronian Supergroup

in the

context

ofa

Paleoproterozoie Wilson cycle

in

the Great Lakes region, Canadian

Minevalogi.si. 33: 921-922,'

600

SEDIMENT FLUXES AND RATES OF SEDIMENTATION

Cross-references

Carbonate Mineralogy and Geochemistry

Diagenesis

Dolomites and Dolomitization

Evaporites

Ironstones and Iron Formations

Oceanic Sediments

Oolite and Coated Grains

Phosphorites

Siliceous Sediments

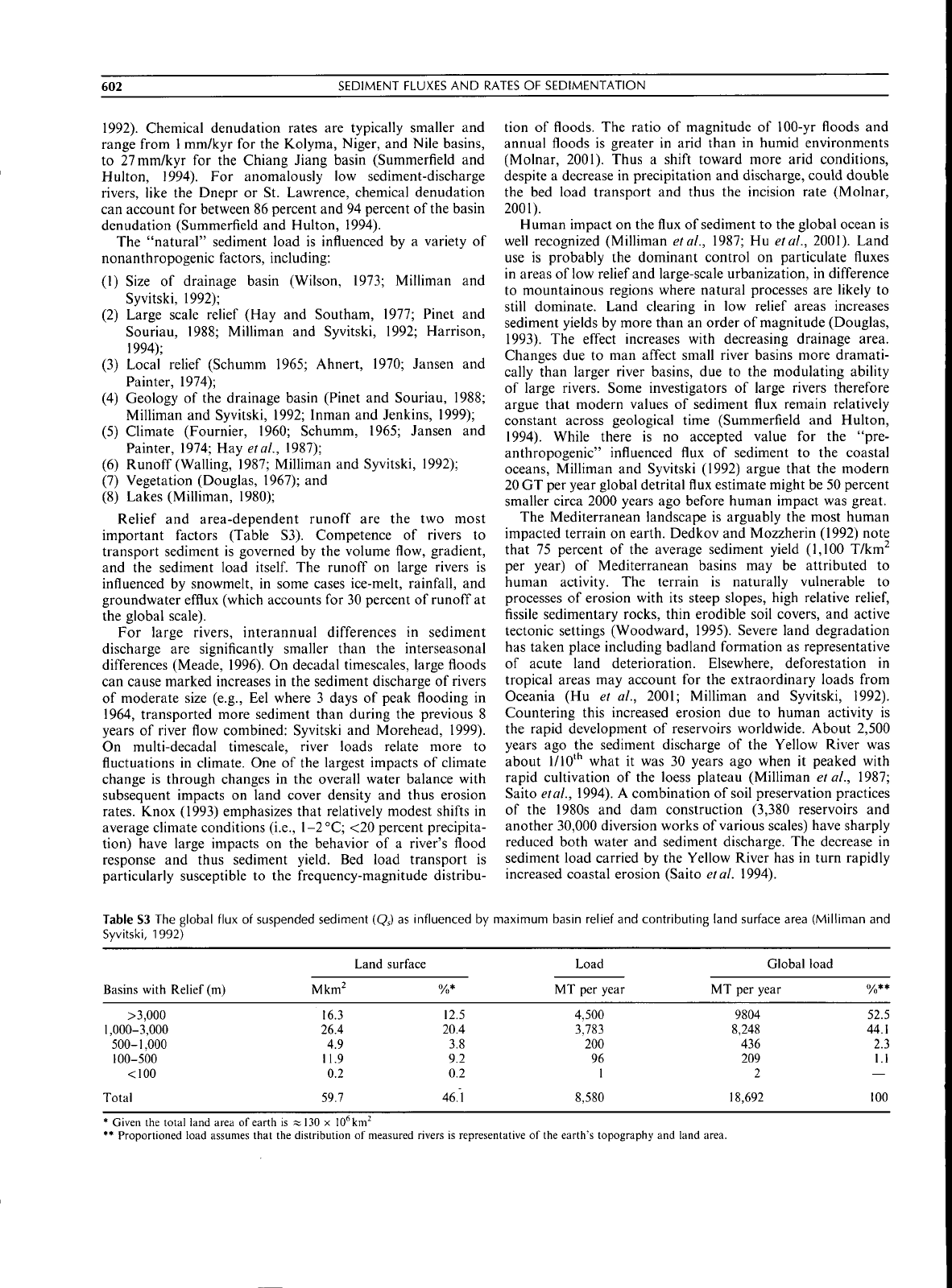

Table SI Relationships (see text for terminology details)

Q,=

C,,Q

QT=Qs +

MIT=QO

[MIL']

[M/T]

[M/T]

[M/T]

[L/T]

[L/T]

[L/T]

SEDIMENT FLUXES AND RATES OF

SEDIMENTATION

An understanding of sediment fluxes, both at the local and

global scale, involves identifying sites where sediment is

produced, the processes involved in liberating this sediment,

and processes and rates involved in the transport of the

sediment to depositional environments. Sediment production

occurs at sites where sedimentary particles form, across sites of

temporary storage of these sediment particles, and even at sites

of long-term storage, given tectonic movement within geolo-

gical systems. While terminology remains an important part of

compartmentalizing and understanding earth science, consis-

tency in use of terms is not universal. Here we describe a few of

the important terms related to sediment fluxes and sedimenta-

tion rates.

Definitions and concepts

Weathering is the rate-limiting step in the entire sequence of

events. Weathering involves both chemical and biogeochemical

processes that work to dissolve minerals within rock faces

and the cements holding together the detrital grains within

sedimentary rocks. Using a complex of natural inorganic

and organic compounds found universally within aerosols and

surface water, grains are liberated, fractures are weakened and

material is generated for subsequent transport. Active weath-

ering also involves mechanical processes that apply physics to

the destruction of rock surfaces. Mechanical processes include

the freeze thaw action of water, wind or water abrasion

involving grain on grain impact, the action of glaciers (ice on

rock abrasion, rock carried by ice on rock; quarrying), and the

generation and impact of rockslides. Younger mountains shed

more sediment (up to a factor of seven) than indurated and

older mountains (Pinet and Souriau, 1988).

Sediment undergoes remobilization through sheet, rill and

gully erosion of hillslopes, through landslides, and through

channel erosion. The mass of sediment that passes by a given

cross-section per unit time is known as the transport load (M),

given in units of kg per second or MT per year. The terms

transport rate and sediment discharge are used interchangeably

with transport load. The transport load consists of the dis-

solved load (Qo) and the detrital load (QT), or just one if

specified. Yield (Y) is the transport load normalized per unit

drainage basin area

(Aj/,),

often given in units of T/km^ per

year, kg/m^ per year, or g/cm^ per year, and can include both

detrital and dissolved load (Table SI). The

rate

of erosion {ER)

has the same meaning as yield except that it tends to be used in

more local environments and to reflect shorter events. Over

time the exposed land surface is weathered and lowered with

respect to a datum, at a rate known as the denudation

rate

{D),

in units of length per time (mm/kyr). The denudation rate is a

measure of earth surface removal, and takes into account both

dissolved and detrital surface lowering.

Most dissolved load is transported within surface and

subsurface waters flowing to the ocean. A much smaller

portion is transported in the form of aerosols, within the

atmospheric circulation. While most of the dissolved load

initially ends up in the ocean as dissolved salt, uptake by

plankton and other primary producers converts much of the

dissolved load back into a solid form, including tests of silica

and carbonate, larger shells and coral reefs. Subsequent

chemical and mechanical degradation of reefs, and transport

of these biogenic grains along with other shell fragments and

tests,

adds to the detrital load being transported across the

depositional environments.

Detrital grains are transported primarily by water and wind,

as bed load (Q/,) and suspended load (Q.,), but regionally may

also be transported by flowing ice (ice-sheets, glaciers, icebergs,

sea ice). Bed load, sometimes called contact

load,

consists of

coarser particles that travel along the bed by traction and or

saltation, essentially in continuous contact with the bed. Bed

load particles move through the influence of shear stress or

drag imposed by the moving fluid (water or air), along with

other grain-to-grain interactions. If the flowing fluid is unable

exceed some threshold in stream power or critical shear stress,

bed load transport ceases. The suspended load consists of

particles suspended within the fluid by turbulence or by

colloidal suspension. The suspended load consists of both a

bed-material load (i.e., ofthe same range of grain size as found

on the bed), and a

wash

load (finer material than bed particles).

Often the term sediment load is used interchangeably with

suspended load, as bed load is typically a minor component of

the total load. The local sediment load is then the upstream

load

{QTO)

plus the density-corrected difference between the

erosion rate and the depositional rate, a relationship known as

the Exner equation. Sediment eoncentration (Q) is the dry

weight of suspended sediment per unit volume of water or air

{V),

at any given time and place. Thus the suspended sediment

load is simply the sediment concentration times the discharge

rate, {Q), i.e., the fluid volume moved per unit time.

The sedimentation rate, also known as the deposition rate

(Dn),

is the vertical flux of sediment to the depositional

surface, such as the seafloor in the case of a marine

environment (e.g., kg/m^ per year). Sedimentation rates vary

across time, because periods of rapid sedimentation alternate

with periods of slower deposition, quiescence, or erosion. Thus

SEDIMENT FLUXES AND RATES OF SEDIMENTATION

601

sedimentation rates in various depositionat environments refer

to average values of net sedimentation.

The rate of sedimentation within a basin strongly depends

on the proximity to the sediment source, such as a river mouth

or ice terminus. Typically, the sedimentation rate decreases

exponentially away from the source. If the sediment source

location is fixed in time, fluctuations in sedimentation rate are

a function of sediment supply. However, the location of a

sediment source is commonty variable in geological time,

determined by variations in sea level, the position of an ice

terminus or river mouth. During a period of rising sea levet,

the river mouth moves landward and thus the rate of offshore

sedimentation will decrease. Sedimentation rate therefore

depends on both the yield of sediment from tand and the

distance that the sediment load has to travel to a particular

location. This leads to two axioms (Syvitski, 1993):

• Constant or increasing accumulation rates indicates either:

(i) increasing sediment input; or (ii) decreasing distance from

the source.

• Decreasing accumulation rates indicate either: (i) constant

or decreasing sediment input; or (ii) increasing distance from

source.

The shoreline is therefore an arbitrary boundary within the

detrital sediment transport system.

Accumulation rate (rj) is the vertical change in the deposi-

tional surface due to the composite sedimentation history (e.g.,

mm per year), and equals the deposition rate minus the erosion

rate times the sediment buttc density. Sediment bulk density (p)

is a function of distance from the sediment supply (grain

size and excess pore pressure as conditioned by the rate of

sedimentation), buriat depth and time (compaction). Erosion

events (such as sediment failures or wave resuspension) work

to decrease the accumulation rate in the shallower portions of

a basin and increase the rates in the deeper water sections.

Accumulation rates are influenced by biological, chemical,

geological, and geographical factors, and are highly variable

within depositional environments, between depositional

environments and across geological time.

Accumulation rate is often reported as a site-specific

measurement, such as determined from the thickness of

sediment between two dated horizons within a sediment core.

However, basin shape can greatly affect the accumulation rate.

Given a constant depositional rate, the local accumulation rate

will decrease as a power function with time, due to the ever-

increasing width of a basin floor concomitant with sedimentary

fill ofthe basin (Syvitski, 1993). For example, the initially higii

(up to 9 m per year , Powell, 1983) accumulation rates within

fjords seem extremely high because the basin floors are very

narrow. After a few tliousand years, when fjords are filled with

hundreds of meters of sediment, accumulation rates will

appear to have decreased by orders-of-magnitude, even if the

depositional rate is held constant. Therefore when comparing

different basins, it is useful to calculate accumulation rates at

the regional level (Syvitski, 1993): i.e., the total mass of

sediment between dated unit boundaries, normalized to the

depositional area

{Aj^.p).

Influences and rates

The erosion of bedrock takes place almost entirely in the

headwaters of the catchment. This newly eroded sediment is

then transported toward the coastal zone. How long it takes

for this transport and how sediment makes the journey are

important questions. However, denudation rate and/or regio-

nal erosion rates are similarly independent of the magnitude

ofthe terrestrial flux of sediment to the ocean (Kirchner etal.,

2001).

Very little (sslO percent) of the sediment that is

eroded from the mountains and hilltops actually makes it to

the ocean. Most of the sediment is either in flux, or being

sequestered in interior drainage basins, lakes, subsiding

alluvial fans, fiood plains, coastal plains and deltaic plains

(Meade, 1996). Holeman (1980) notes that 20th century

erosion across the conterminous US (5.3 GT per year) is an

order-of-magnitude higher than the fluvial discharge of

sediment (0.445GT per year: Curtis etal., 1973). And while

eolian transport to the global ocean is small (Table S2), wind

erosion dominates water erosion at the eontinental scale

(Smith etal., 2001).

At the seasonal scale, sediment is stored in riverbeds and

along their banks at low or falling discharge, only to be

resuspended at high or rising discharges. Often temporarily

stored sediment is washed out of the system before peak

discharge is reached. At the decade to century timeseale,

sediment moves down the drainage system as a series of

kinematic waves, wherein it might take decades for the

sediment to reach the lower reaches of the flood basin. At

even longer timescales (millennia), tectonics plays an impor-

tant role and there are large variations between subsiding

basins and basins being exhumed (uplifted). Understanding

these scales plays an important role in deciphering the

difference between soil erosion and sediment discharge by

rivers (Meade, 1996).

Most of the sediment delivered to the ocean is by rivers,

which accounts for approximately 95 percent ofthe global flux

from land to sea (Table SI). Most of that flux is as suspended

sediment load. Dissolved load and bed load are nearly an

order-of-magnitude less than the suspended load. Detrital

denudation rates range from

1

mm/kyr for the St. Lawrence

River basin, to 670 mm/kyr for the Brahmaputra River system.

Small mountainous rivers have detrital denudation rates

that can exceed 40,000 mm/kyr (Milliman and Syvitski,

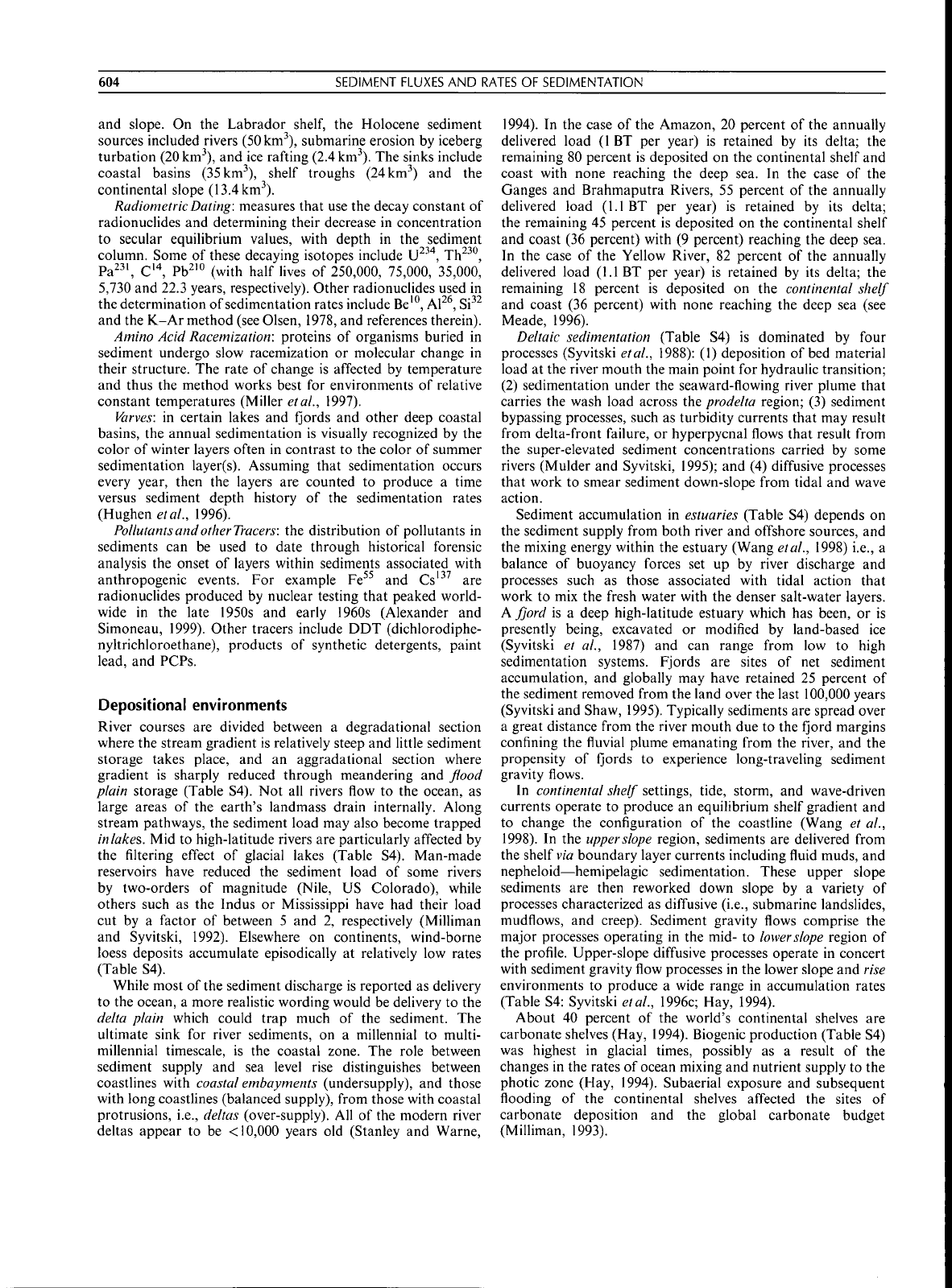

Table S2 Clobal estimates of the flux of sediment from land to the ocean

Transport mechanism

Global flux

GT per year

18

2

5

2

0.7

0.4

Estimate grade

B+

B"

B+

C

C

D

Reference

Milliman and Syvitski, 1992

Milliman and Syvitski, 1992

Summerfield and Hulton, 1994

Hay, 1994

Garrels and Mackenzie, 1971

Hay, 1994

Rivers: suspended load

bed load

dissolved load

Glaciers, sea ice, icebergs

Wind

Coastal Erosion

602

SEDIMENT FLUXES AND RATES OF SEDIMENTATION

1992).

Chemical denudation rates are typically smaller and

range from

1

mm/kyr for the Kolyma, Niger, and Nile basins,

to 27 mm/kyr for the Chiang Jiang basin (Summerfield and

Hulton, 1994). For anomalously low sediment-discharge

rivers,

like the Dnepr or St. Lawrence, chemical denudation

can account for between 86 percent and 94 percent of the basin

denudation (Summerfield and Hulton, 1994).

The "natural" sediment load is influenced by a variety of

nonanthropogenic factors, including:

(1) Size of drainage basin (Wilson, 1973; Milliman and

Syvitski, 1992);

(2) Large scale relief (Hay and Southam, 1977; Pinet and

Souriau, 1988; Milliman and Syvitski, 1992; Harrison,

1994);

(3) Local relief (Schumm 1965; Ahnert, 1970; Jansen and

Painter, 1974);

(4) Geology of the drainage basin (Pinet and Souriau, 1988;

Milliman and Syvitski, 1992; Inman and Jenkins, 1999);

(5) Climate (Fournier, 1960; Schumm, 1965; Jansen and

Painter, 1974; Hay etal., 1987);

(6) Runoff (Walling, 1987; Milliman and Syvitski, 1992);

(7) Vegetation (Douglas, 1967); and

(8) Lakes (Milliman, 1980);

Relief and area-dependent runoff are the two most

important factors (Table S3). Competence of rivers to

transport sediment is governed by the volume flow, gradient,

and the sediment load

itself.

The runoff on large rivers is

influenced by snowmelt, in some cases ice-melt, rainfall, and

groundwater efflux (which accounts for 30 percent of runoff at

the global scale).

For large rivers, interannual differences in sediment

discharge are significantly smaller than the interseasonal

differences (Meade, 1996). On decadal timescales, large floods

can cause marked increases in the sediment discharge of rivers

of moderate size (e.g.. Eel where 3 days of peak flooding in

1964,

transported more sediment than during the previous 8

years of river flow combined: Syvitski and Morehead, 1999).

On multi-decadal timeseale, river loads relate more to

fluctuations in climate. One of the largest impacts of climate

change is through changes in the overall water balance with

subsequent impacts on land cover density and thus erosion

rates.

Knox (1993) emphasizes that relatively modest shifts in

average climate conditions (i.e., 1-2 °C; <20 percent precipita-

tion) have large impacts on the behavior of a river's flood

response and thus sediment yield. Bed load transport is

particularly susceptible to the frequency-magnitude distribu-

tion of floods. The ratio of magnitude of 100-yr floods and

annual floods is greater in arid than in humid environments

(Molnar, 2001). Thus a shift toward more arid conditions,

despite a decrease in precipitation and discharge, could double

the bed load transport and thus the incision rate (Molnar,

2001).

Human impact on the flux of sediment to the global ocean is

well recognized (Milliman etal., 1987; Hu etal., 2001). Land

use is probably the dominant control on particulate fluxes

in areas of low relief and large-scale urbanization, in difference

to mountainous regions where natural processes are likely to

still dominate. Land clearing in low relief areas increases

sediment yields by more than an order of magnitude (Douglas,

1993).

The effect increases with decreasing drainage area.

Changes due to man affect small river basins more dramati-

cally than larger river basins, due to the modulating ability

of large rivers. Some investigators of large rivers therefore

argue that modern values of sediment flux remain relatively

constant across geological time (Summerfield and Hulton,

1994).

While there is no accepted value for the "pre-

anthropogenic" influenced flux of sediment to the coastal

oceans, Milliman and Syvitski (1992) argue that the modern

20 GT per year global detrital flux estimate might be 50 percent

smaller circa 2000 years ago before human impact was great.

The Mediterranean landscape is arguably the most human

impacted terrain on earth. Dedkov and Mozzherin (1992) note

that 75 percent of the average sediment yield (1,100 T/km^

per year) of Mediterranean basins may be attributed to

human activity. The terrain is naturally vulnerable to

processes of erosion with its steep slopes, high relative

relief,

fissile sedimentary rocks, thin erodible soil covers, and active

tectonic settings (Woodward, 1995). Severe land degradation

has taken place including badland formation as representative

of acute land deterioration. Elsewhere, deforestation in

tropical areas may account for the extraordinary loads from

Oceania (Hu et al., 2001; Milliman and Syvitski, 1992).

Countering this increased erosion due to human activity is

the rapid development of reservoirs worldwide. About 2,500

years ago the sediment discharge of the Yellow River was

about l/lO'*' what it was 30 years ago when it peaked with

rapid cultivation of the loess plateau (Milliman etal., 1987;

Saito etal., 1994). A combination of soil preservation practices

of the 1980s and dam construction (3,380 reservoirs and

another 30,000 diversion works of various scales) have sharply

reduced both water and sediment discharge. The decrease in

sediment load carried by the Yellow River has in turn rapidly

increased coastal erosion (Saito etal. 1994).

Table S3 The global flux of suspended sediment

(Q^)

as influenced by maximum basin relief and contributing land surface area (Milliman and

Syvitski,

1992)

Basins with Relief (m)

Land surface Load Global load

Mkm^

16.3

26.4

4.9

11.9

0.2

%*

12.5

20.4

3.8

9.2

0.2

MT per year

4,500

3,783

200

96

1

MT per year

9804

8,248

436

209

2

%**

52.5

44.1

2.3

1.1

>3,000

1,000-3,000

500-1,000

100-500

<100

Total 59.7

46.1

8,580

18,692

100

* Given the total land area of earth is * 130 x 10 km

** Proportioned load assumes that the distribution of measured rivers is representative of the earth's topography and land area.

SEDIMENT FLUXES AND RATES OF SEDIMENTATION

603

Global sediment fluxes are known to ehange aeross broad

geologie time. Hay (t994) notes that Hotoeene fluxes to

marginal seas are typically 1.5 to 4 times higher than that for

similar periods during the Pleistocene. Quaternary sediment

was deposited at globally averaged aeeumulation rates of 4 g/

em^ per year, whieh is 54 pereent higher than the Pliocene and

3 times higher than the Mioeene rates (Hay, 1994). Carbonate

sediment accounts for 18.4 percent of the total Quaternary

sediments in the ocean basins, whereas it accounts for 40 to 50

percent of Miocene and earlier sediments. Peizhen etal. (2001)

show that global sediment aeeumulation rates inereased by

2-10 times beginning 2-4 Myr ago, when climate switched

from a long period of elimate stability, to a time of frequent

abrupt ehanges in temperature, preeipitation, and vegetation.

The result was that during the Quaternary, the landseaped

moved away from equilibrium configurations to periods of

high sediment produetion from landscapes out of equilibrium.

Ice sheets and glaciers ereate sediment through abrasion,

quarrying, and ehannelized and nonehannelized fluid flow at

their base. Estimates ofthe global flux of glacial detritus range

from 1.5 GT per year to

50

GT per year with the lower value

probable (Table S2). The higher estimates do not effeetively

take into aeeount the reeyeling of glaeimarine sediment baek

into the iee mass (R. Powell, Pers. eomm., 2001). The sediment

delivery rate from iee sheets and glaciers to the oeean depends

on a variety of processes. Their marine termini melt at a rate

dependent on the temperature of the ocean water and the

strength of the eurrents flowing aeross the termini (Syvitski,

1989).

The sediment delivery rate will thus depend on the melt

rate and the concentration of sediment (supraglaeial, englaeial

and subglacial) within the glacier. Sediment is also transported

at the base of a glaeier as basal till, through a variety of

subglacial processes (Andrews and Syvitski, 1994). Fast

flowing ice streams are more able to transport till compared

with eold-based or slow flowing ice sheets (Syvitski, 1993).

Meltwater flowing within and beneath the iee mass is able to

carry large volumes of sediment, and this is particularly true

for Alasican glaciers. Sediment delivery from the melt of

drifting icebergs is perhaps the greatest sediment-dispersal

mechanisms as icebergs are able to transit hundreds to

thousands of kilometers (Syvitski etal., 1996a,b).

The wind borne flux of sediment to the oeean is in the order

of 0.5 GT per year to 0.9 GT per year (Table S2), but greatly

varies with time (Garrels and Maekenzie, 1971). While river

diseharge is the largest global contributor of sediment

(Table S2), eolian transport is of equal magnitude to that of

river flux for the continent of Africa {cf Prospero, 1981;

and Milliman and Syvitski, 1992). While eolian transport is

important today, fluvial transport dominated the supply of

sediment to the Arabian Sea during the last glacial period.

Coastal erosion is not well-known but global estimates vary

from 0.2 GT per year to 0.9 GT per year (Hay, 1994), with

anthropogenic effects of significance at the regional level. Sea

ice,

where ubiquitous, is also able to earry large volumes of

coastal sediment into the deeper ocean, ineluding sediment

that was initially transported to the eoast by wind or streams

(Gilbert, 1983).

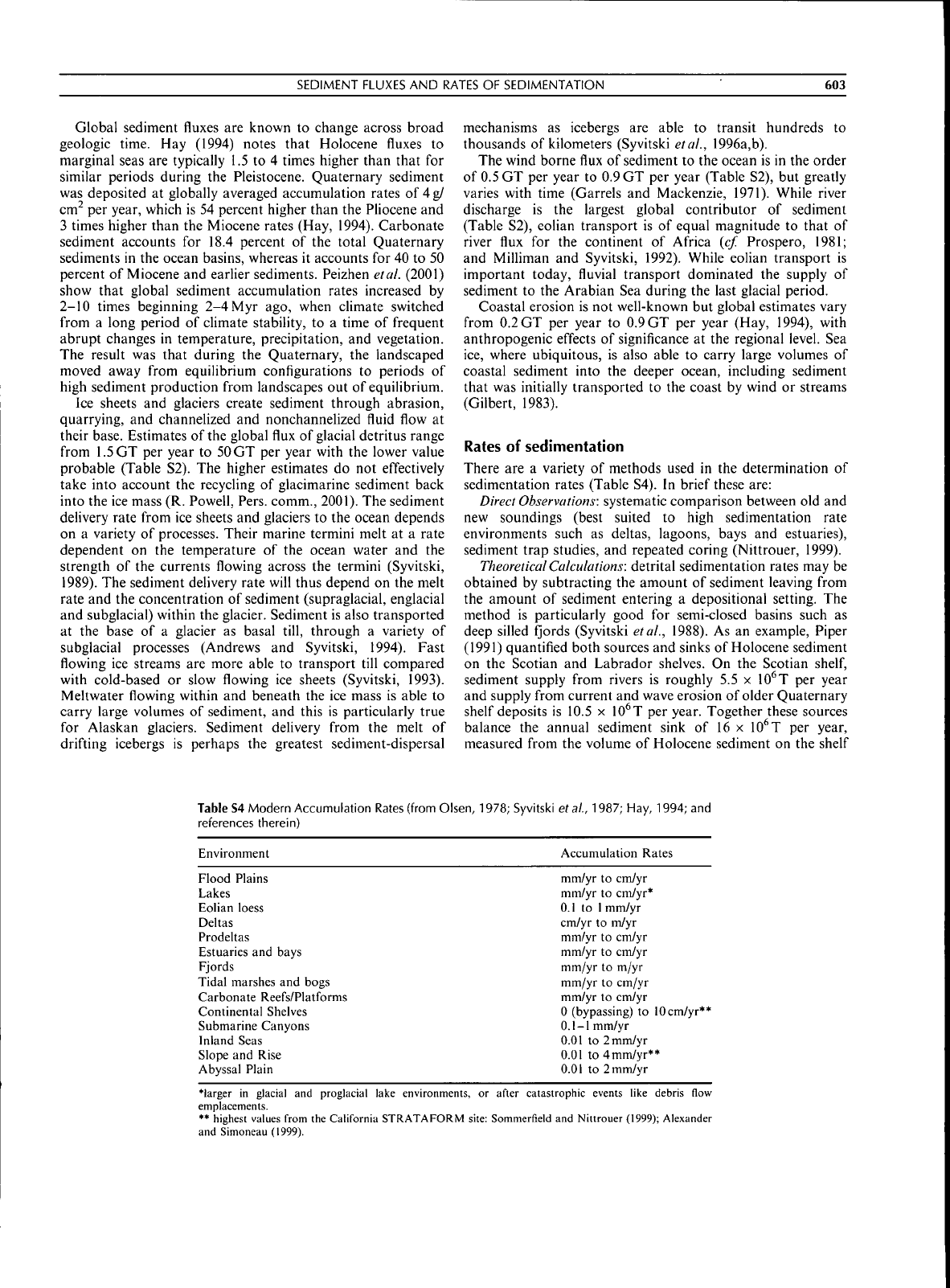

Rates of sedimentation

There are a variety of methods used in the determination of

sedimentation rates (Table S4). tn brief these are:

Direct

Observations:

systematic comparison between old and

new soundings (best suited to high sedimentation rate

environments sueh as deltas, lagoons, bays and estuaries),

sediment trap studies, and repeated coring (Nittrouer, 1999).

Theoretical

Calculations:

detrital sedimentation rates may be

obtained by subtracting the amount of sediment leaving from

the amount of sediment entering a depositional setting. The

method is partieularly good for semi-closed basins such as

deep silled fjords (Syvitski etal., 1988). As an example. Piper

(1991) quantifled both sources and sinks of Holoeene sediment

on the Seotian and Labrador shelves. On the Seotian

shelf,

sediment supply from rivers is roughly 5.5 x lO^T per year

and supply from eurrent and wave erosion of older Quaternary

shelf deposits is 10.5 x 10*T per year. Together these sourees

balance the annual sediment sink of 16 x 10*T per year,

measured from the volume of Holocene sediment on the shelf

Table S4 Modern Accumulation Rates (from Olsen, 1978; Syvitski ef

al.,

1987; Hay, 1994; and

references therein)

Environment

Accumulation Rates

Flood Plains

Lakes

Eolian loess

Deltas

Prodeltas

Estuaries and bays

Fjords

Tidal marshes and bogs

Carbonate Reefs/Platforms

Continental Shelves

Submarine Canyons

Inland Seas

Slope and Rise

Abyssal Plain

mm/yr to cm/yr

mm/yr to cm/yr*

0.1 to I mm/yr

cm/yr to m/yr

mm/yr to cm/yr

mm/yr to cm/yr

mm/yr to m/yr

mm/yr to cm/yr

mm/yr to cm/yr

0 (bypassing) to

10

cm/yr*

0.1-1 mm/yr

0.01 to 2 mm/yr

0.01 to4mm/yr**

0.01 to 2 mm/yr

*larger in glacial and proglacial lake environments, or after catastrophic events like debris flow

emplacements.

** highest values from the California STRATAFORM site: Sommerfield and Nittrouer (1999); Alexander

and Simoneau (1999).

604 SEDIMENT FLUXES AND RATES OF SEDIMENTATION

and slope. On the Labrador

shelf,

the Holocene sediment

sources included rivers (50 km^), submarine erosion by iceberg

turbation (20 km^), and ice rafting (2.4

km'').

The sinks include

coastal basins (35 km'), shelf troughs (24 km') and the

continental slope (13.4 km'').

Radiometric

Dating:

measures that use the decay constant of

radionuclides and determining their decrease in concentration

to secular equilibrium values, with depth in the sediment

column. Some of these decaying isotopes include U^''', Th^'*',

Pa^", C'", Pb^'° (with half lives of 250,000, 75,000, 35,000,

5,730

and 22.3 years, respectively). Other radionuclides used in

the determination of sedimentation rates include Be'", Al^^, Si'^

and the K-Ar method (see Olsen, 1978, and references therein).

Amitto Acid Racenuzation; proteins of organisms buried in

sediment undergo slow racemization or molecular change in

their structure. The rate of change is affected by temperature

and thus the method works best for environments of relative

constant temperatures (Miller etal., 1997).

Varves: in certain lakes and fjords and other deep coastal

basins, the annual sedimentation is visually recognized by the

color of winter layers often in contrast to the color of summer

sedimentation layer(s). Assuming that sedimentation occurs

every year, then the layers are counted to produce a time

versus sediment depth history of the sedimentation rates

(Hughen etal., 1996).

Pollutants and otherTracers: the distribution of pollutants in

sediments can be used to date through historical forensic

analysis the onset of layers within sediments associated with

anthropogenic events. For example Fe^^ and Cs"' are

radionuclides produced by nuclear testing that peaked world-

wide in the late 1950s and early 1960s (Alexander and

Simoneau, 1999). Other tracers include DDT (dichlorodiphe-

nyltrichloroethane), products of synthetic detergents, paint

lead, and PCPs.

Oepositional environments

River courses are divided between a degradational section

where the stream gradient is relatively steep and little sediment

storage takes place, and an aggradational section where

gradient is sharply reduced through meandering and flood

plain storage (Table S4). Not all rivers flow to the ocean, as

large areas of the earth's landmass drain internally. Along

stream pathways, the sediment load may also become trapped

intakes. Mid to high-latitude rivers are particularly affected by

the filtering effect of glacial lakes (Table S4). Man-made

reservoirs have reduced the sediment load of some rivers

by two-orders of magnitude (Nile, US Colorado), while

others such as the Indus or Mississippi have had their load

cut by a factor of between 5 and 2, respectively (Milliman

and Syvitski, 1992). Elsewhere on continents, wind-borne

loess deposits accumulate episodically at relatively low rates

(Table S4).

While most of the sediment discharge is reported as delivery

to the ocean, a more realistic wording would be delivery to the

delta plain which could trap much of the sediment. The

ultimate sink for river sediments, on a millennial to multi-

millennial timeseale, is the coastal zone. The role between

sediment supply and sea level rise distinguishes between

coastlines with coastal embayments (undersupply), and those

with long coastlines (balanced supply), from those with coastal

protrusions, i.e., deltas (over-supply). All of the modern river

deltas appear to be < 10,000 years old (Stanley and Warne,

1994).

tn the case of the Amazon, 20 percent of the annually

delivered load (1 BT per year) is retained by its delta; the

remaining 80 percent is deposited on the continental shelf and

coast with none reaching the deep sea. In the case of the

Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers, 55 percent of the annually

delivered load (1.1 BT per year) is retained by its delta;

the remaining 45 percent is deposited on the continental shelf

and coast (36 percent) with (9 percent) reaching the deep sea.

In the case of the Yellow River, 82 percent of the annually

delivered load (1.1 BT per year) is retained by its delta; the

remaining 18 percent is deposited on the continental shelf

and coast (36 percent) with none reaching the deep sea (see

Meade, 1996).

Deltaic seditnentation (Table S4) is dominated by four

processes (Syvitski etal., 1988): (1) deposition of bed material

load at the river mouth the main point for hydraulic transition;

(2) sedimentation under the seaward-flowing river plume that

carries the wash load across the prodelta region; (3) sediment

bypassing processes, such as turbidity currents that may result

from delta-front failure, or hyperpycnal flows that result from

the super-elevated sediment concentrations carried by some

rivers (Mulder and Syvitski, 1995); and (4) diffusive processes

that work to smear sediment down-slope from tidal and wave

action.

Sediment accumulation in estuaries (Table S4) depends on

the sediment supply from both river and offshore sources, and

the mixing energy within the estuary (Wang etal., 1998) i.e., a

balance of buoyancy forces set up by river discharge and

processes such as those associated with tidal action that

work to mix the fresh water with the denser salt-water layers.

A fjord is a deep high-latitude estuary which has been, or is

presently being, excavated or modified by land-based ice

(Syvitski et al., 1987) and can range from low to high

sedimentation systems. Fjords are sites of net sediment

accumulation, and globally may have retained 25 percent of

the sediment removed from the land over the last 100,000 years

(Syvitski and Shaw, 1995). Typically sediments are spread over

a great distance from the river mouth due to the fjord margins

confining the fluvial plume emanating from the river, and the

propensity of fjords to experience long-traveling sediment

gravity flows.

In continental shelf settings, tide, storm, and wave-driven

currents operate to produce an equilibrium shelf gradient and

to change the configuration of the coastline (Wang et al.,

1998).

In the

upper slope

region, sediments are delivered from

the shelf

via

boundary layer currents including fluid muds, and

nepheloid—hemipelagic sedimentation. These upper slope

sediments are then reworked down slope by a variety of

processes characterized as diffusive (i.e., submarine landslides,

mudflows, and creep). Sediment gravity flows comprise the

major processes operating in the mid- to lower slope region of

the profile. Upper-slope diffusive processes operate in concert

with sediment gravity flow processes in the lower slope and rise

environments to produce a wide range in accumulation rates

(Table S4: Syvitski etal, 1996c; Hay, 1994).

About 40 percent of the world's continental shelves are

carbonate shelves (Hay, 1994). Biogenic production (Table S4)

was highest in glacial times, possibly as a result of the

changes in the rates of ocean mixing and nutrient supply to the

photic zone (Hay, 1994). Subaerial exposure and subsequent

flooding of the continental shelves affected the sites of

carbonate deposition and the global carbonate budget

(Milliman, 1993).