Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SEDIMENT FLUXES

AND

RATES

OF

SEDIMENTATION 605

Summary

(1) Weathering is the rate-limiting step in the entire sequence

of events determining global sediment fluxes and rates of

sedimentation.

(2) Sedimentation rates vary across time, because periods of

rapid sedimentation alternate with periods of slower

deposition, quiescence, or erosion. Sedimentation rates in

various depositional environments are therefore average

values of net sedimentation.

(3) The rate of sedimentation within a basin strongly depends

on the proximity to the sediment source, such as a river

mouth or ice terminus.

(4) Very little («10 percent) of the sediment eroded from

mountains and hilltops actually makes it to the ocean.

Most of the sediment is either in flux, or being sequestered

in interior drainage basins, lakes, subsiding alluvial fans,

flood plains, coastal plains and deltaic plains.

(5) Sediment delivery via rivers accounts for approximately

95 percent ofthe global flux from land to sea. Most of that

flux is as suspended sediment load. Dissolved load and bed

load are almost an order-of-magnitude less than the

suspended load, with important regional exceptions.

(6) Drainage basin area and relief are the most important

"geological" factors in controlling the sediment load of

rivers. However, modern rivers are greatly impacted by

human activity, either through increases in soil erosion, or

through sediment load reduction from reservoir flltration.

(7) While contributing less to the modern global flux of

sediment, sediment transport by ice, wind and waves,

remains important in regions dominated by these pro-

cesses, and achieve more global signiflcance at earlier times

in the Quaternary.

James P.M. Syvitski

Bibliography

Ahnert,

F.,

1970, Functional relationships between denudation,

relief,

and uplift

in

large mid-latitude drainage basins. American Journal

of Science, 268: 243-263.

Alexander,

CR,, and

Simoneau,

A,M,, 1999,

Spatial variability

in

sedimentary processes

on the Eel

continental slope. Marine Geol-

ogy, 154: 243-254,

Andrews, J,T,,

and

Syvitski, J,P,M,, 1994, Sediment fluxes along high

latitude glaciated continental margins: Northeast Canada

and

Eastern Greenland,

In Hay, W,

(ed,), Glohal Sedimentary

Geofluxes. Washington: National Academy

of

Sciences Press,

pp,

99-115,

Clague,

J,J,, and

Evans,

S,G,,

2000,

A

review

of

catastrophic drainage

of moraine-dammed lakes

in

British Columbia, Quaternary Science

Reviews,

19:

1763-1783,

Curtis, W,F,, Culbertson,

K,, and

Chase, E,B,, 1973, Fluvial-sediment

discharge

to the

oceans from

the

conterminous United States,

US

Geological

Survey Circular, 670:

1-17,

Dedkov, A,P,,

and

Mozzherin, V,I,, 1992, Erosion

and

sediment yield

in mountain regions ofthe world.

In

Walling,

D,E,,

Davies,

T,R,,

and Hasholt,

B,

(eds,). Erosion, Debris Elows

and

Environment

in

Mountain Regions. Proceedings

of the

Chengdu Symposium, July

1992),

IAHS Publication,

209, pp,

29-36,

Douglas,

I,, 1993,

Sediment transfer

and

siltation.

In

Turner,

B,L,,

Clark,

W,C,,

Kates,

R,W,,

Richards,

J,F,,

Mathews,

J,T,, and

Meyer,

W,B,

(eds,).

The

Earth

as

Transformed

by

Human Action.

Cambridge University Press,

pp,

215-234,

Douglas,

J,, 1967, Man,

vegetation

and the

sediment yield

of

rivers.

Nature, 215: 925-928,

Fournier,

F,, 1960,

Climatet Erosion. Paris: Presses Universitaires

de

France,

Garrels,

R,M,, and

Mackenzie,

F,T,,

1971, Evolution

of

Sedimentary

Rocks. Norton,

Gilbert,

R,, 1983,

Sedimentary processes

of

Canadian arctic Ijords,

Sedimentary Geology,

36:

147-175,

Harrison,

C,G,, 1994,

Rates

of

continental erosion

and

mountain

building, Geologische Runschau, 83: 431-447,

Hay,

W,H,, 1994,

Pleistocene-Holoeene fluxes

are not the

earth's

norm.

In Hay, W,

(ed,), Global Sedimentary Geofluxes. National

Academy

of

Sciences Press,

pp,

15-27,

Hay,

W,W,, and

Southam,

J,R,, 1977,

Modulation

of

marine

sedimentation

by the

continental shelves.

In

Andersen, N,R,,

and

Malahoff,

A,

(eds,). TheFateofEossilEuelCO2 intheOcean. Plenum

Press,

pp,

569-604,

Hay,

W,W,,

Rosol,

M,J,,

Jory,

D,E,, and

Sloan,

J.L, II, 1987,

Tectonic control

of

global patterns

and

detritai

and

carbonate

sedimentation.

In

Doyle, L,J,,

and

Roberts, H,H, (eds,). Carbonate

Clastic Transitions: Developments

in

Sedimentology. Elsevier,

pp,

1-34,

Holeman,

J,N,, 1980,

Erosion rates

in the US

estimated from

the

soil

conservation services inventory,

EOS,

61:

954,

Hu,

D,,

Saito,

Y,, and

Kempe,

S,, 2001,

Sediment

and

nutrient

transport

to the

coastal zone.

In

Galloway, J,N,,

and

Melillo,

J,M,

(eds,),

Asian Change

in

the Context of Global Climate Change: Impact

of Natural and Anthropogenic Changes

in

Asia on

Global

Biogeochem-

ical Cycles. Cambridge University Press, IGBP Publication, Series

3,

pp,

245-270,

Huglien,

K,A,,

Overpeck, J,T,, Anderson, R,F,,

and

Williams,

K,M,,

1996,

The

potential

for

paleoclimate records from varved Arctic

lake sediments: Baffin Island, eastern Canadian Arctic,

In

Kemp,

A,E,S,

(ed,), Paleoclimatology

and

Paleoceanography from

Laminated Sediments. Geological Society Special Publication,

116,

pp,

57-71,

lnman,

D,L,, and

Jenkins,

S,A,, 1999,

Climate ehange

and the

episodicity

of

sediment flux

of

small California rivers, Journat of

Geology, 107: 251-270,

Jansen, J,M,,

and

Painter, R,B,, 1974, Predicting sediment yield from

climate

and

topography, Journalof Hydrology, 21: 371-380,

Kirehner,

J,W,,

Finkel,

R,C,,

Riebe,

CS,,

Granger,

D,E,,

Clayton,

J,L,, K^ing, J,G,,

and

Megahan, W,F,, 2001, Mountain erosion over

lOyr, IOk,yr,,

and

10m,yr, time scales. Geology,

29:

591-594,

Knox,

J,C, 1993,

Large increase

in

flood magnitude

in

response

to

modest changes

in

climate. Nature, 361: 430-432,

Meade,

R,H,, 1996,

River-sediment inputs

to

major deltas.

In

Milliman,

J,D,, and Haq, B,U,

(eds,), Sea-Level Rise

and

Coastal

Subsidence. Kluwer Academic Publishers,

pp,

63-85,

Miller, G,H,, Magee, J,W,,

and

Jull, A,J,T,, 1997, Low-latitude glacial

cooling

in the

Southern Hemisphere, from amino-acid racemiza-

tion

in emu

eggshells. Nature, 385: 241-244,

Milliman,

J,D,, and

Syvitski, J,P,M,,

1992,

Geomorphie/teetonic

control

of

sediment discharge

to the

ocean:

the

importance

of

small mountainous rivers, Journalof Geology, 100: 525-544,

Milliman,

J,D,,

1980, Transfer

of

river-borne particulate material

to

the oceans.

In

Martin,

J,,

Burton, J,D,,

and

Eisma,

D,

(eds,). River

Inputs to Ocean Systems. Rome, SCOR/UNEP/UNESCO Review

and Workshop, FAO,

pp, 5-12,

Milliman,

J,D,, 1993,

Production

and

accumulation

of

calcium

carbonate

in the

ocean: budget

ofa

nonsteady state. Global Bio-

chemical

Cycles,

1:

927-957,

Milliman, J,D,, Qin, Y,S,,

and

Ren, M,E,Y,, 1987, Man's influenee

on

the erosion

and

transport

of

sediment

by

Asian rivers:

the

Yellow

River (Huanghe) example. Journal of Geology, 95: 751-762,

Molnar,

P,,

2001, Climate change, flooding

in

arid environments,

and

erosion rates. Geology,

29:

1071-1074,

Mulder,

T,, and

Syvitski, J,P,M,, 1995, Turbidity currents generated

at

river mouths during exceptional discharge

to the

world oceans.

Journal of Geotogy, 103: 285-298,

Nittrouer,

CA,, 1999,

STRATAFORM: overview

of its

design

and

synthesis

of

its results. Marine Geology, 154:

3-12,

Nordin,

CF,, 1978,

Fluvial sediment transport.

In

Fairbridge,

R,W,,

and Bourgeois,

J,

(eds,). Encyclopedia of Sedimentology. Dowden,

Hutchison

&

Ross,

pp,

339-343,

Olsen,

CR,, 1978,

Sedimentation rates.

In

Fairbridge,

R,W,, and

Bourgeois,

J,

(eds,). Encyclopedia

of

Sedimentology. Dowden,

Hutchison

&

Ross,

pp,

687-692,

606

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT

BY

TIDES

Peizhen,

Z,,

Molnar,

P,, and

Downs,

W,R,, 2001,

Increased

sedimentation rates

and

grain sizes 2m,yr,

to

4m,yr,

ago due to

the influence

of

climate change

on

erosion rates. Nature, 410: 891-

897,

Pinet,

P,, and

Souriau,

M,,

1988, Continental erosion

and

large-scale

relief.

Tectonics,

7:

563-582,

Piper, D,J,W,,

1991,

Seabed geology

of the

Canadian eastern

continental

shelf.

Continental Shelf Research, 11: 1013-1035,

Powell,

R,D,, 1983,

Glacial-marine sedimentation proeesses

and

lithofaeies

of

temperate glaciers. Glacier

Bay,

Alaska,

In

Molnia,

B,F,

(ed,). Glacial-marine Sedimentation. Plenum Press,

pp, 185-

232

Prospero, J,M,, 1981, Eolian transport

to

the world ocean.

In

Emiliani,

C, (ed,), The Sea,

Volume

7,

The Oceanic Lithosphere. John Wiley

&

Sons,

801-874,

Saito,

Y,,

Ikehara,

K,,

Katayama,

H,,

Matsumoto,

E,, and

Yang,

Z,,

1994,

Course shift

and

sediment discharge changes ofthe Huanghe

recorded

in

sediments

of

the East China Sea, Chishitsu News,

476:

8-16,

Schumm,

S,A,,

1965, Quaternary paieohydrology.

In

Wright, H,E,

Jr,,

and Frey, D,G, (eds,). The Quaternary ofthe United States. Princeton

LJniversity Press,

pp,

783-794,

Smith,

S,V,,

Renwick, W,H,, Buddemeier, R,W,,

and

Crossland,

CJ,,

2001,

Budgets

of

soil erosion

and

deposition

for

sediment

and

sedimentary organic carbon across the conterminous tJnited States,

Global Biogeochemical

Cycles,

15: 697-707,

Sommerfield,

C,K,, and

Nittrouer,

CA,,

1999, Modern accumulation

rates

and a

sediment budget

for the Eel

shelf:

a

flood-dominated

depositional environment. Marine

Geology,

154:

227-241,

Stanley,

D,J,, and

Warne,

A,G,, 1994,

Worldwide initiation

of

Holocene marine deltas

by

deceleration

of

sea-level rise. Science,

265:228-231,

Summerfield, M,A,,

and

Hulton, N,J,, 1994, Natural controls

of

fluvial

denudation rates

in

major world drainage basins, Journalof

Geo-

physical Research,

99:

13871-13883,

Syvitski,

J,,

Field,

M,,

Alexander,

C,

Orange,

D,, and

Gardner,

J,,

1996c, Continental-slope sedimentation. Oceanography,

9: 163-

167,

Syvitski,

J,P,, and

Morehead,

M,D,,

1999, Estimating river-sediment

discharge

to the

ocean: applieation

to the Eel

margin, northern

California, Marine

Geology,

154: 13-28,

Syvitski, J,P,M,, 1989,

On the

deposition

of

sediment within glacier-

influenced fjords: oceanographic controls. Marine Geology,

85:

301-329,

Syvitski, J,P,M,,

1993,

Glaeimarine environments

in

Canada:

an

overview, Canadian Journat of Earth Sciences,

30:

354-371,

Syvitski, J,P,M,,

and

Shaw,

J,,

1995, Sedimentology

and

geomorphol-

ogy

of

fjords.

In

Perillo, G,M,E, (ed,), Geomorphology

and

Sedi-

mentology of Estuaries. Elsevier,

pp,

113-178,

Syvitski, J,P,M,, Lewis, C,F,M,,

and

Piper, D,J,W,, 1996a, Paleocea-

nographic information derived from acoustic surveys

of

glaciated

continental margins: examples from eastern Canada,

In

Andrews,

J,T,, Austin, W,E,N,, Bergsten,

H,, and

Jennings, A,E, (eds,). Late

Quaternary Palaeoceanography

of the

North Atlantic Margins.

Geological Society, Special Publication, 111,

pp,

51-76,

Syvitski, J,P,M,, Andrews,

J,T,, and

Dowdeswell,

J,A,,

1996b,

Sediment deposition

in an

iceberg-dominated glaeimarine environ-

ment. East Greenland: basin fill implications. Global and Planetary

Change, 12: 251-270,

Syvitski, J,P,M,, Burrell, D,C,,

and

Skei, J,M,, 1987,

Fjords:

Proeesses

and

Products.

Springer-Verlag,

Syvitski, J,P,M,, Smith, J,N,, Boudreau, B,,

and

Calabrese, E,A,, 1988,

Basin sedimentation

and the

growth

of

prograding deitas. Journal

of

Geophysical

Research, 93: 6895-6908,

Syvitski, J,P,M,,

in

press. Supply

and

flux

of

sediment along

hydrological pathways: research

for the 21st

century. Global and

Planetary Change.

Walling, D,E,, 1987, Rainfall,

runoff,

and

erosion ofthe land:

a

global

view.

In

Gregory,

K,J,

(ed,). Energetics

of

Physical Environment.

Wiley,

pp,

89-117,

Wang,

Y,, Ren,

M,-E,,

and

Syvitski, J,P,M,, 1998, Sediment transport

and terrigenous fluxes.

In

Brink, K,H,,

and

Robinson,

A,R,

(eds,).

The Sea:

Volume

10—The Global Coastal

Ocean:

Processes

and

Meth-

ods.

John Wiley

&

Sons, 253-292,

Wilson,

L,, 1973,

Variations

in

mean annual sediment yield

as a

function

of

mean annual preeipitation, American Journalof Science,

lli\ 335-349,

Woodward,

J,C,, 1995,

Patterns

of

erosion

and

suspended sediment

yield

in

Mediterranean river basins.

In

Foster, I,D,L,, Gurnell,

A,M,,

and

Webb,

B,W,

(eds,). Sediment and

Water

Quality in River

Catchments. John Wiley

&

Sons,,

pp,

365-389,

Cross-references

Climatie Control

of

Sedimentation

Compaction (Consolidation)

of

Sediments

Erosion

and

Sediment Yield

Numerical Models

and

Simulation

of

Sediment Transport

and

Deposition

Sediment Transport

by

Unidirectional Water Flows

Tectonic Controls

of

Sedimentation

Weathering, Soils

and

Paleosols

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT

BY

TIDES

Tidal currents

Tidal currents are unique among the processes responsible for

sediment transport and deposition because of their regularity,

with the speed and direction varying with thie frequency of

the governing astronomical period (see Tides and Tidal Rhyth-

mites).

tn coastal settings where the shorelines constrain

the flow, the landward- (flood) and seaward-directed (ebb)

currents typically have directions 180° apart, in a pattern that

is termed rectilinear, A period of little or no current (i,e,, slack-

water) varying in length from a few to several tens of minutes

generally accompanies each flow reversal. As a result, sediment

transport is intermittent, with episodes of sand transport (ifthe

currents are sufficiently strong) alternating with periods of

mud deposition during the slack-water intervals (Figure S6). In

open-shelf settings removed from the confining influence of

coastlines, tidal currents are rotary because of the influence of

the Coriolis force (Allen, 1997), with the direction changing

progressively through 360° over one complete tidal period. In

such situations, there is no slack-water period, although the

currents transverse to the primary flow directions generally are

slower than the main ebb and flood currents. As a result, mud

deposition is inhibited. Typically, the highest maximum speeds

are found in constricted, inshore areas, where they may be as

high as 1-2 m/s. As a result, the transport and deposition of

sediment by tides is most important in coastal zones, with tidal

currents dominating sedimentation inside the sheltered con-

fines of estuaries, lagoons, and deltaic distributary channels

where wave action is minimal (see Neritic Carbonate Deposi-

tional; Environments Deltas and Estuaries).

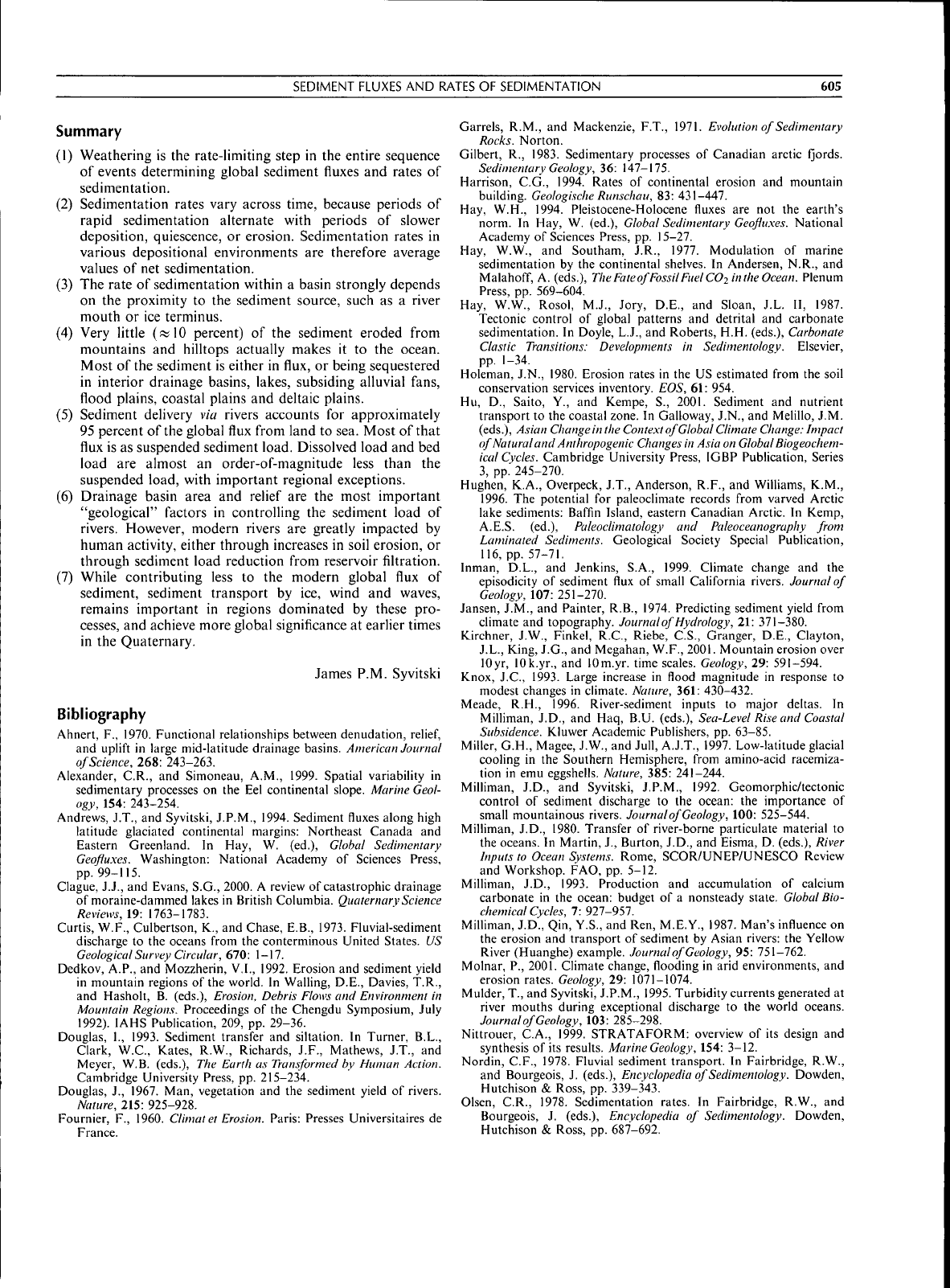

In the ideal case, tidal-current speeds vary sinusoidally

over an individual ebb or flood period, with equal durations

and speeds in the opposing directions. In this case, there is

no net (residual) sediment transport (Figure S6(A)), In reality,

however, various factors cause deviations from the ideal;

producing a time-velocity asymmetry that causes an inequality

in the amount of sediment transported in the two directions

(Figure S6(B)),

Tidal-wave deformation: in the shallow water ofthe coastal

zone, the crest of the tidal wave travels faster than the trough

because the latter experiences greater frictional retardation.

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT BY TIDES 607

Convergence ofthe shoreline, creating a landward decrease in

the cross-seetional area, eompounds this distortion. As a

result, the flood tide typieally has a shorter duration and

higher maximum speed than the ebb tide (Dyer. 1995).

Hypsoiiiciric

inffitenccs:

because the arca-elcvation distribu-

tion (the hyp.somctry) of coastal areas is generally not linear.

the volume of water passing through any channel will vary in

response to temporal changes in si/c ofthe area being flooded

or drained (Boon and Byrne. 1981). Thus, the maximum

eurrent speeds will tend to occur when the largest area is being

flotided or drained rather than at tnid-tide. Such hypsometric

inlluences can also cause inequalities between the maximtim

ebb and flood ctn'rents (Friedriehs attd Aubrey. 1988).

Figure S6 Tr^insport of bedload sediment by: (A) an idealized,

'.ymmf^rital Itrlal current; and (Hi a lidal current with a pronounced

lime-vetocily asymmetry. The bedload discharge Istippled area) is

approximated as: ty, /. \U,-U^,\', for

U,>U,,

(the cross-hatched

areas), wht're U, is ihe (k^plh-aver.iged lidal-current speed and (_/,r

>^

thf threshold ol bedload movement, in (A) the bedlojd discharges in

the opposite directions are equal, suth that there in no net transport. In

iBl the short-duration high speeds on one half of the tide generate

more transport than the slower, longer-duration flow in the opposile

direction,

yielding a residual Iranspori in the direclion of the faster

currents. The black rectangles at the limes of near-zero current speeds

represent tbe periods when mud can be deposited.

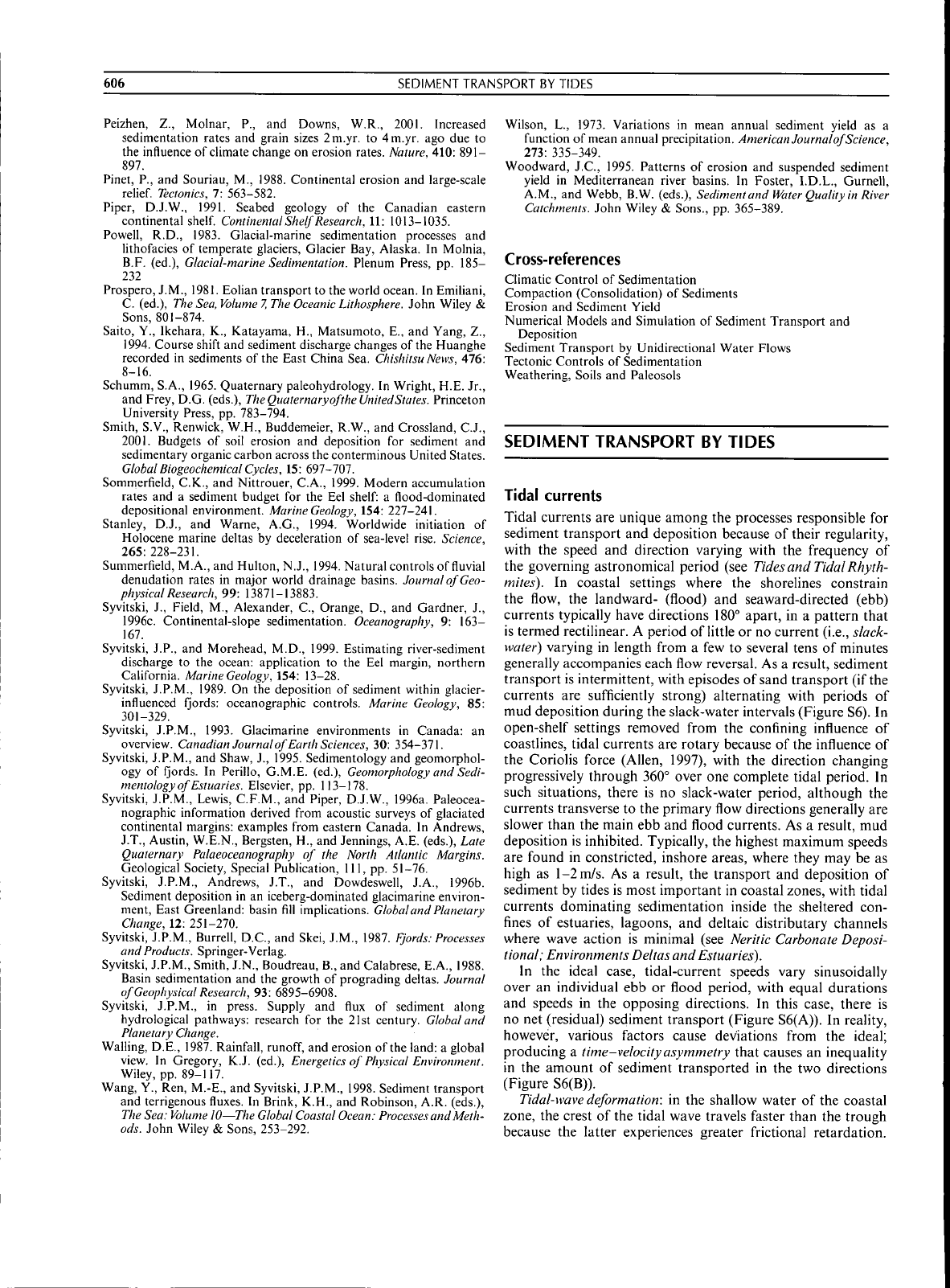

Residual, estuarine eireidation: at tidally influenced river

mouths, fresh water rides above denser seawater (Figure S7).

This generates a net seaward Bow in the upper layer and a

residual landward flow in the near-bed salt wedge (Nichols and

Biggs, 1985: Dyer. 1995), This so-called estuarine circulation,

which occurs in estuaries and delta distributary channels,

becomes progressively less important as the tidal range

increases, because strong tidal currents and intense turbulence

destroy the salinity stratification.

Superimposed currents: wind forcing and oceanic circulation

are responsible for slow water movement on timescales ranging

from hours to years, Sueh currents may not be suflieient by

themselves to initiate sediment movement, but may lead to

residual transport when they are superimposed on the stronger

tidal flows.

Bathymetric influenee: local bathymetric irregularities, in-

cluding bedrock promontories and current-generated sea-bed

topography (e.g., tidal bars), cause spatial variability tn the

bed shear stress, with areas faeing into the current experiencing

stronger eurrents than areas sheltered from the main flow.

Beeause of tidal flow reversals, these areas of exposure and

sheltering alternate positions on each ebb and Hood tide. This

in turn produces inequalities between the ebb and Hood

currents at most locations.

Bedload transport

The transport of sand-sized bed-load sediment by tidal

currents is generally deseribable using the concepts developed

for unidirectional flow (see .Sediment Transport hy Unidirec-

tional

Flows).

The unsteadiness assoeiated with flow aecelera-

tion and deceleration over each tidal cycle has relatively little

affect, because sand-sized sediment responses rapidly to

changes in bed shear stress (Van Rijn, 1993). Consequently.

bed-load-transport equations developed for unidirectional

flows ean be integrated over a complete tidal eyele. using the

instantaneously measured mean current speeds and water

depths, to obtain the residual bed-load discharge, provided

salinity stratification is not pronounced. Because the discharge

of bed-load is a power funetion of [he current speed, the

direetion of residual sand transport can commonly be

determined by comparing only the maximum speeds in the

ebb and flood directions, with lesser regard for the durations of

weaker currents (Figure S6(B)), Thus, the factors that

determine the residual transport of sand are those that most

strongly influenee the inequality ofthe peak speeds,

Bathymetric and hypsometric influences, coupled with any

tluvial discharge, ereate systems oiniutually evasive ehannels:

ehannels that open in a seaward direction tend to be flood

—• Residual circutation

? Suspen&on fallout

Lew

Sea

SSC

High

Figure S7 Formation of a salt wedge, as shown by the inclined salinity contours (dashed lines), in the zone of mixing between fresh water

arid seawater. The resulting, residual estuarine circulation loutward flow irt the surface layer; landward flow near the bed) traps line-grained

material and develops a zone of elevated suspended-sediment toncentrations (SSCsl called the lurbiclily m.iximum.

608

SLDIMENT TKANSP(JRT BY TIDCS

dominant, whereas channels that connect directly to a river

tend to be ebb dominant. Elongate tidal bars separate such

ehannels and have opposite direetions of net sand transport on

either side of their crest (Dalrymple and Rhodes. 1995).

Erosional hed-load partings are produced at locations where

the directions of residual transport diverge (i.e.. there are

opposing directions of net transport

1

on either side of" the

parting: Harris etal,. 1995). Conversely, net deposition occurs

in areas where the residual transport converges, Sueh a hed-

had convergence appears to be present within all estuaries

and in the mouth-bar area of tidally influenced or dominated

deltas:

sand can be moved landward from the shelf because of

the general Hood dominance caused by the shallow-water

distortion oflhe tidal wave, whereas the seaward movement of

river-supplied sediment is slowed hy the periodle eurrent

reversals. On tide-dominated eontinental shelves, bed-load

partings and eonvergences are separated by areas with a

consistent direetion of net sand transport. These seditiiem-

transportpathways may be tens to hundreds of kilometers long

and display a predictable succession of bedform^ (Belderson

et al,. 1982: see also Surface Forms).

Suspended-load transport

Compared to bed-load, the transport of suspended material is

more strongly influenced by flow unsteadiness and weak

residual currents, beeause fine-grained material eontinues to

move for some time after currents have dropped below the

threshold for bed-load movement. Thus, the transport of fine-

grained sediment may be strongly influenced by weak, residual

eurrents. and the net transport of bed-load and suspended-

load sediment may be in different, even opposing, directions.

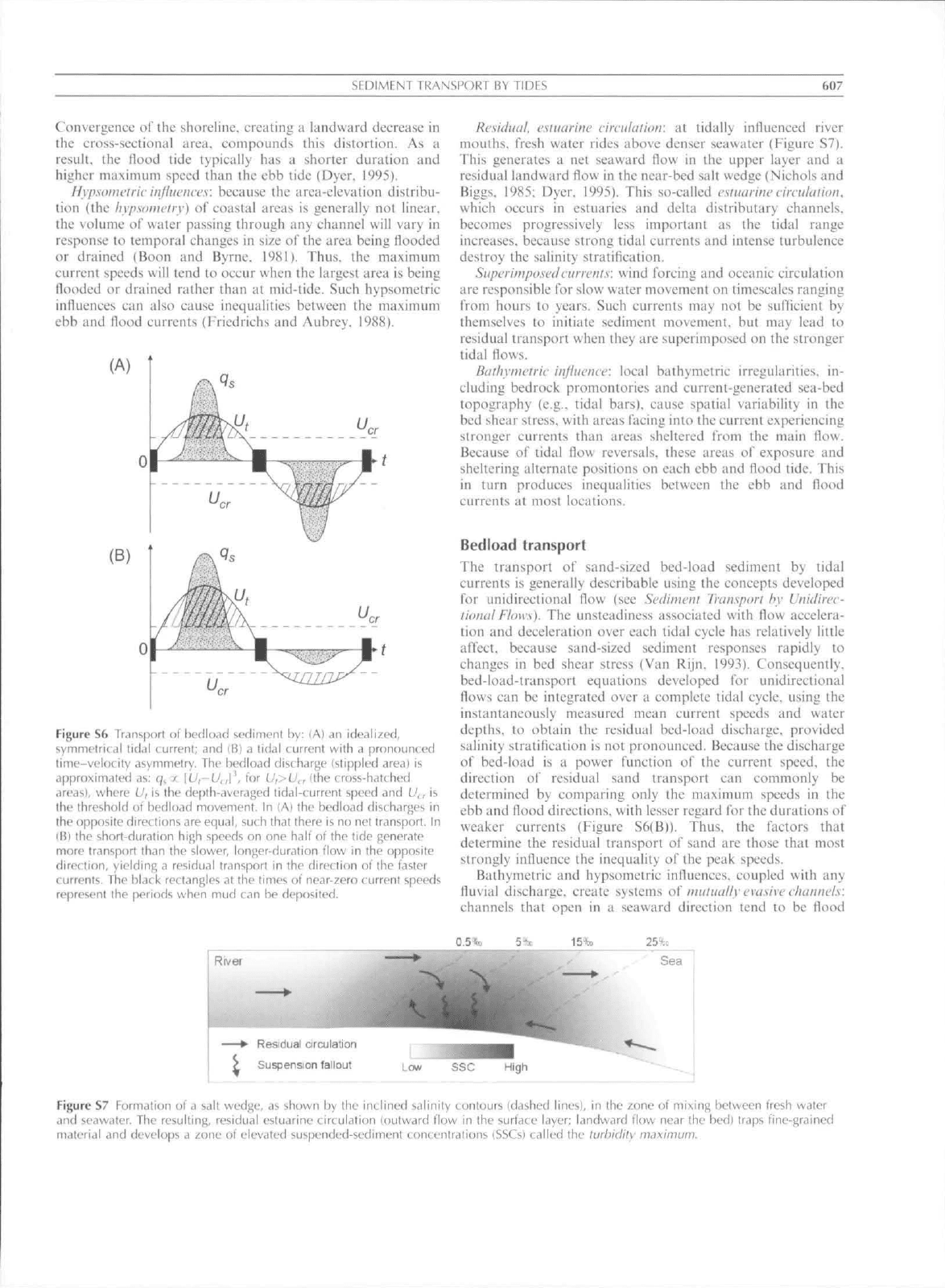

In detail, the movement of suspended sediment lags behind

the water movement, both during deposition from a deeelerat-

ing current and during erosion by an accelerating current. Van

Straatenand Kuenen (1958; c/,'Nichols and Biggs, 1985: Dyer,

1995) developed a simplified, yet elegant, model to aeeount for

the more important affects (Figure S8). In this model, the tide

is assumed to be symmetrical and to show a linear, landward

decrease in the maximum current speed. Two lags are

considered: .settling lag—ihc distance (and time) taken for

suspended sediment to settle to the bed as the current speed

decreases toward slack water (Figure S8(A)): and .scoiirlag a

delay in resuspension from the bed because the current speed

needed to erode fine-grained seditnent is greater than the

eurrent speed at whieh deposition oeeurs (Figure S8(B)), These

two lags operate at both the landward and seaward ends ofa

sediment-particle's excursion over a half tidal cyele. However,

beeause the distance-velocity distributions are asymmetrieal

(even though speeds at any point are sinusoidal), the lags

are longer at the landward end. Furthermore, the water

and particle excursion distances decrease toward the land (i.e.,

E-E' is shorter than F F': Figure S8), Thus, there is a net

landward migration ofthe partiele and a resulting tendency for

fine-grained sediment to aeeumulate near the landward margin

of tidal flats and at the head of estuaries.

The foregoing illustrates that the transport and deposition of

fine-grained sediment is strongly influenced by the faetors

governing the erosion threshold. Unlike noncohesive satid for

which the threshold-of-motion is essentially constant for a give

grain size, the erosion threshold for mud is not constant and

inereases as the degree of consolidation increases (Parchure and

Mehtii, 1986), Thus, the longer slack-water period that

(A) Settling lag only

F 1 E'7

Distance offshore

4 F' E

Und

(B) Settling

/

/

+ scour lag

6

.^ Landward migration of particle

after

one

tidal cycle

"^x~~~--^,^

Erosion Ihreshold

3^, ^^s. DeposTtioo threshold

E'7

Distance offshore

4 F'

Land

Figure S8 Transport history of suspended sedimenl in <i tidal

environment, based on Van Straaten and Kuenen (19,5!!), in a situation

where ihe maximum curreni speeds decrease toward the Itind (dashed

diagonal line in (Ai and IB)I. The presence of a single upper bound for

both ihe flood and ebb current speeds implies ihat Ihe waier

movement is symmeirical, wifh no net water distharge. In (A) only the

effect of settling lag is examined. Water originating^ al

poin!

F

on the

tlood tide enlrains .i particle al locralion

1

when the speed exceeds tbe

ihreshtild velocity

(21,

The particle then travels landward wilh the

current, eventually beinj; deposited at 4, which is located some

distance landward of point i where ihe current speed lalls helow the

ihreshold for continued movement. The distance utnd corresponding

lime inlerval) between ^ and 4 is termed ihe settling l,ig. On the

ensuing ebb tide, water originating at F' retraces the F-F' trajectory, but

is nol able to re-entrain the particle because the speed has not reached

the threshold hy the time Ihe water reaches location 4, Instead, water

origin.iting at

F

re-entrains the particle, carries it seaward along the

trajectory F-E', and deposits il at 7, The distance ol travel between 6

and 7 is also a result of the settling lag. However, because of the

distance-velocity asymmetry and ihe shorter excursion on the ebl) tide,

the particle experiences

a

net landward dis[)lacement

{^

->7). Note that

a particle coming to rest landward of point X in (A) cannot be re-

entrained by the tidal currenis shown because the maximum current

speed is olwtiys below the threshold. (Bi shows a similar transport

history but introduces separate erosiun and deposition thresholds,

which is more realislic than the situation shown in (A). As a result of

the higher erosion threshold, poini

E

is located further landward than

in IAI. This causes an increased dc^lay in the fe-entrainment of the

particle whic:h Van Straaten and Kuenen (1958) termed the scour Lig.

(Note that the definition of stour lag given by Nichols and Biggs (1985)

and Dyer (1995) is not precisely the same as the original definitionl.

Because of the scour lag, tbe particle does nol travel as far seaward and

experiences a greater, net landward displacement than in (A). (A) and

(B) after Figures S7 and 4, respectively, of Van Siraaten and Kuenen

(19581.

characterizes more landward locations promotes higher erosion

thresholds, longer seour lags, and prefc'rential mud deposition.

Exposure to ihe atmosphere, especially at times of high

evaporation potential, and the growth of microbial coatings

are particularly effective at produeing cohesion (see Tidal

Flats),

The residual estuarine circulation discussed above is also

significant with regard to the trapping of suspended sediment

in coastal settings. The suspended sediment introduced by the

river moves seaward in the surficial layer, but then settles into

the landward-moving lower layer (Figure S7). a process that is

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT BY UN1DIRF(T1ONAL WATER ELOWS 609

by (he flocculation o'i line-grained sediment thai occurs

in thi.s region (Nichols and Biggs, 1985: Burban

etaf.

1989:

Dyer. 1995). This circulation leads to the increase of

suspended-sediment concentrations (SSCs) near the limit of

salt-water intrusion (Nichols and Biggs. 1985: Dyer. 1995),

The higher transport capacity that characterizes the flood tide

in many eases, beeause of the shallow-water deformation o\'

the tidal uave (see above), also contributes to the trapping ol'

line-grained sediment near the landward limit oC tidal

influence. The combined influence of these factors produces a

ttirhiditytna.ximuni in which SSCs are elevated relative to areas

further landward or seaward (Figure S7), SSCs in the turbidity

maximum tend to increase as the tidal energy increases, and

thus tend to be highest in maerotidal areas and at spring tides,

because of greater restispension ot" mud. Near-bed SSCs ean

exceed lOgl ' producing mobile sediment bodies that are

called fluid mud {Vans, 1991). These dense suspensions occupy

ehaiincl-bottom locations where they can form anomalously

thick mud deposits. The high SSCs promote this deposition b\

decreasing the bed shear stress (Li and Gust. 2000) during the

ensuing tidal current. As a result, higher mean eurrent speeds

are needed to resuspend the sediment than would be the ease in

the absence of the high SSCs.

Summary

The transport of sediment by tidal currents is complex because

ol' the pronouneed temporal and spatial variability of flow

strength and direction. Sediment particles of ditTerent sizes

respond to the flow unsteadiness with different amounts of lag,

sueh that bed-load and suspended load can display different

directions of residual transport: bed-load tends to move in the

direetion o\' the current with the higher peak speed, whereas

the suspended load commonly moves in the direction of the

residual water movement. Bathymetric and hypsometric

influences produce spatial inequalities in the strengths of the

flood and ebb currents, creating complex transport pathway^.

characterized in coastal areas by mutually evasive channels.

The common development of a flood dominance because

of the distortion of the tidal wave in shallow water, coupled

with the presence of a density-driven estuarine circulation,

leads to the trapping of both bed-load and suspended-load

material within estuaries and/or at the mouth of deltaic

distributaries. Fluid mud is commonly formed beneath the

turbidity maximum ihat forms as a result of this trapping.

Robert W. Dalrymple and Kyuiigsik Choi

Bibliography

AlL-n. I',A,. IW7, Eurih Sitrlmc

Processes.

Blackwell Scienec,

IkldLTsoii. R,H,. Johnson. M.A,. and Kciiyon. N.H., 1982. Bedlorms.

hi Stride. A,H, (cd,).

Offshore'Eidal

Saiuls:

Proeesses

and Deposits.

New York: Chapman and Hall, pp, 27 .^7,

Boon, J.D,. and Byrne, R.J., lysi. On basin hypsoniotry and ihc

morphodynamic response oTcoiistal iiiloi syslems, Murinc Geologv.

40:

27 48.

Biirban.

P,-Y.,

Lick, W,, and Lick. J,. 1^89, The lloccLilalion of fine-

iirained sedimcnls in estuarine wiuers. Journal of Geophvsieul

''Research.

94: 832.1 83.10.

Dalrymple. R,W,. and Rliodes. R.N,. 1995, Lstuarinc dunes and

bartorms. In Perillo. G,M,E. (ed,|. GeomorphologyunilSedimenlol-

ogv of Esiiiarii's. Elsevier. Developments in Sedimentology 53,

pp,

359-422-

Dyer. K.R.. 1995, Sediment iranspori processes in eslu^ries. In Perillo.

G.M.E. (ed,). Geomorphology and Sedimentology «l EsUiavifs.

Amsterdam: Elsevier. Developments in Sedimentology 53, pp.

423-449,

Eaas.

R.W., 1991. Rhcological boundaries ol' mud: vvlieii,' are ihe

limils,'

Geo-Mariiie Eeilcrs. II: 143-146,

Friedriehs, G,T., and Aubrey. D,G,. 19XK, Non-linear tidal disloriion

in shallow well mixed estiiaries: a synihesis, Estuarine. Coastal and

Shelf Science. 27: 521 546.

Harris, PT.. Pattiaratehi. C.B,, Collins. M.B,. and Dalrymple, R,W,,

1995.

Whai is a bedload parling,' In Flemming. B.W,, and

Barloloma, A, (eds,), Tidal Signuttnes in Modern itnd

.Aneicni

Sedi-

menis. Inlcrnalional Association ol' Sedimentologists. Special

Publication. 24. pp. 2 10,

Li,

M.Z,. and Gust. G,, 2000, Boundary layer dynamics and drag

rcduelion in Hows of high eohesive sediment suspensions. Sedi-

menlologv. 47: 71 86,

Nicho)s.M.M,,andBi{;{;s.R,B.. 1985, Esiuarie.s, In Davis. R.A. Jr. (ed.).

CoastalScdimcniaiyEnvironments. Springer-Verlag. pp. 77-186.

Parehuie. T.M,, and Mehla. A.J,, 19S6, Erosion of soft cohesive sedi-

ment deposits. Journal<>f Hydraulic Engineering. llL 1308 1326,

Van Rijn, L.C, 1993. Principles of Sediment Iransptirt in River.s. Estu-

aries, and

CoastuI

Scus. Amsterdam: Aqua Publications.

Van Straaten. L.M,J,U,. and Kuenen. Ph.H,. 1958, Tidal action us a

cause of elay accumulation. Joiirnulof Sedimeiiturv Peirology. 28:

406 413,

Cross-references

Deltas and Estuaries

Floceulation

Nerilie Carbonate Deposilional Environments

Surface Forms

Tidal Flals

Tides and Tidal Rhvthmiles

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT BY UNIDIRECTIONAL

WATER ELOWS

Sediment properties

Description of sediment movement involves terms sueh as

grain size, shape and density, settling velocity, and sediment

transport rate. F^or the range of grain size, shape and density of

sediment available lor transport see Grain Size and Shape.

Methods of measuring and analyzing these grain properties are

described also in Carver (1971) and McManus (198S). A

sediment grain immersed in water experiences a hydrostatic

pressure that is greater on its base than on its top: an upward

directed buoyancy force equal to the weight of water displaeed

by the grain. If the weight of the grain exceeds the buoyancy

foree, the grain will sink. The immersed

weight

of the grain is

the gravity force minus the buoyancy foree, given by

Vg ((7-p), where V is grain volume, ,^' is gravitational

acceleration, a is sediment density, and p is fluid density.

Drag on sediment grains

A fluid moving relative to a solid boundary, sueh as water

flowing over a bed of sediment or a sedimenl grain settling in

water, experiences resistance to motion due to the action of

various types of frietional forees (e.g., viscous shear siress,

dynamic pressure). This resistanee to motion is called drai^.

Drag due to viscous shear is called surface drag or skin-frietion

drag, whereas drag due to fluid pressure is ealled form drag. In

turbulent (lows, form drag is normally much more important

than surface drag.

610 SEiDIMFNT TRANSPORT BY UNIDIRECTIONAL WATER FLOWS

A general equation for the drag force is: linear function of drag. As

(Eq. I)

where C), is n drag coefficient, a is the cross-sectional area

exposed to the drag, and

V,.

is the relative velocity of the solid

and fluid. The term in braekets is actually the dynamie pres,sure

on the area of the solid that faces the fluid tlow, but this term

also accounts for the pressures on the lee-side of the solid

associated with flow separation, and for viscous forees. Flow

separation produces a pressure against the flow (form drag).

The drag eocfflcicnt takes into account whether or not flow

separation occurs behind a solid body, and the nature of such

flow separation, ineltiding the size ofthe separation eddies. The

drag coefficient therelbre depends on the geotnetry ofthe solid

body, and speeifieally how streamlined it is. The drag coefficient

is also dependent on an appropriate Reynolds number, as this

determines the relative importiince of viscous drag and form

drag. The drag equation is used in two important eases: (1) the

settling of grains in fluids (See Grain

Threshold.

Grain Settling):

and. (2) fluid moving over beds of sediment.

Drag and lift on bed grains

The mean drag force acting on bed grains is commonly

resolved into components parallel to the bed (drag) and

normal to the bed (lift). The mean drag on a sediment grain

can be expressed as:

= Cp

a(pu-/2)

(Eq, 2)

where u is the mean velocity ofthe fluid at the level of effeetive

mean drag. This velocity is proportional to the square root of

the bed shear stress, z,,. The level of effective drag depends on

the shape of the grain and its position in the bed. The drag

coefficient for single grains resting on the bed is similar to that

for settling grains. The area exposed to drag depends on the

shape ofthe grain, and how it is packed in the sediment bed.

This area will be proportional to the square of grain size. Thus,

it ean be shown that

FflXT.D- (Eq.3)

where the constant of proportionality depends on the grain

shape and orientation, its relative protrusion above the mean

bed level, and the grain Reynolds number.

Both turbulent and nonturbulent fluid lift forces can act on

bed grains (summary in Bridge and Dominic. 1984). Non-

turbulent lift forees are pressures caused by asymmetrical ilow

around near-bed grains. As turbulenee originates very elose to

the bed of a stream, bed grains are undoubtedly alTected by

turbulent lift, and this is most likely to be dominant over non-

turbulent lift (outside the viseous sublayer). Fluid lift is

commonly expressed in a similar way to drag, but using a lift

coefficient instead ofa drag coefficient.

The threshold of transport of cohesionless sediment

(sand and gravel)

If fluid drag and lift forces exceed the forces keeping sediment

grains in place on the bed (gravity and cohesive forces

associated with vegetation, microbial coatings, eementation,

and clay minerals), the grains will be entrained by the flow. In

the case of cohesionless grains, the threshold of entrainmenf

depends on the balance between the drag and gravity forces.

Fii and Fl, respectively, as long as fluid lift is assumed to be a

and

Fu

x(a-

the threshold of entrainment should depend on

(Eq. 4)

fEq. 5)

(Eq. 6)

where 0 is referred to as the dimensionless hed

,shear

stress

(a measure of sediment mobility) and D is a grain size

representative of all grains in the bed. Values of dimensionless

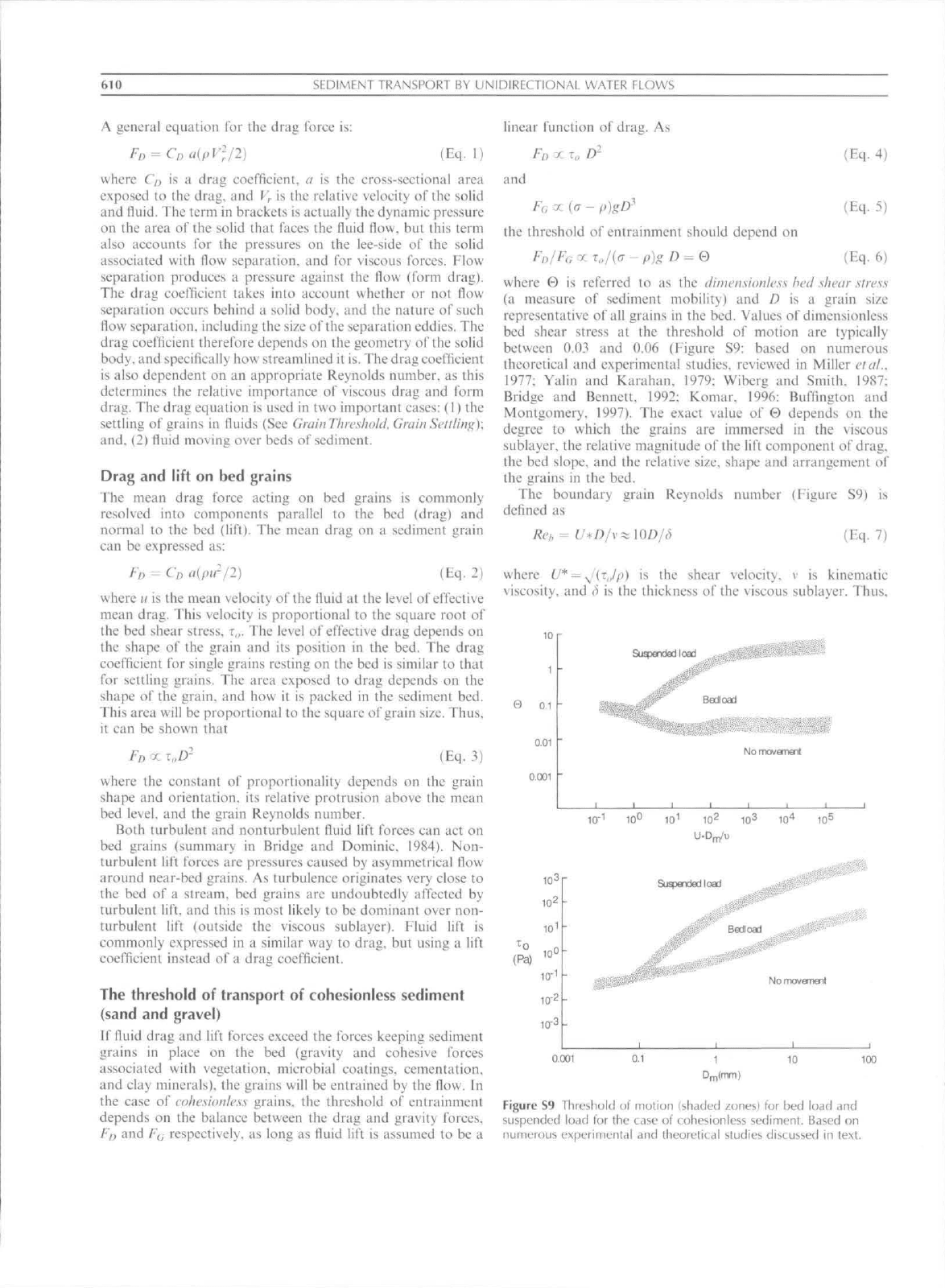

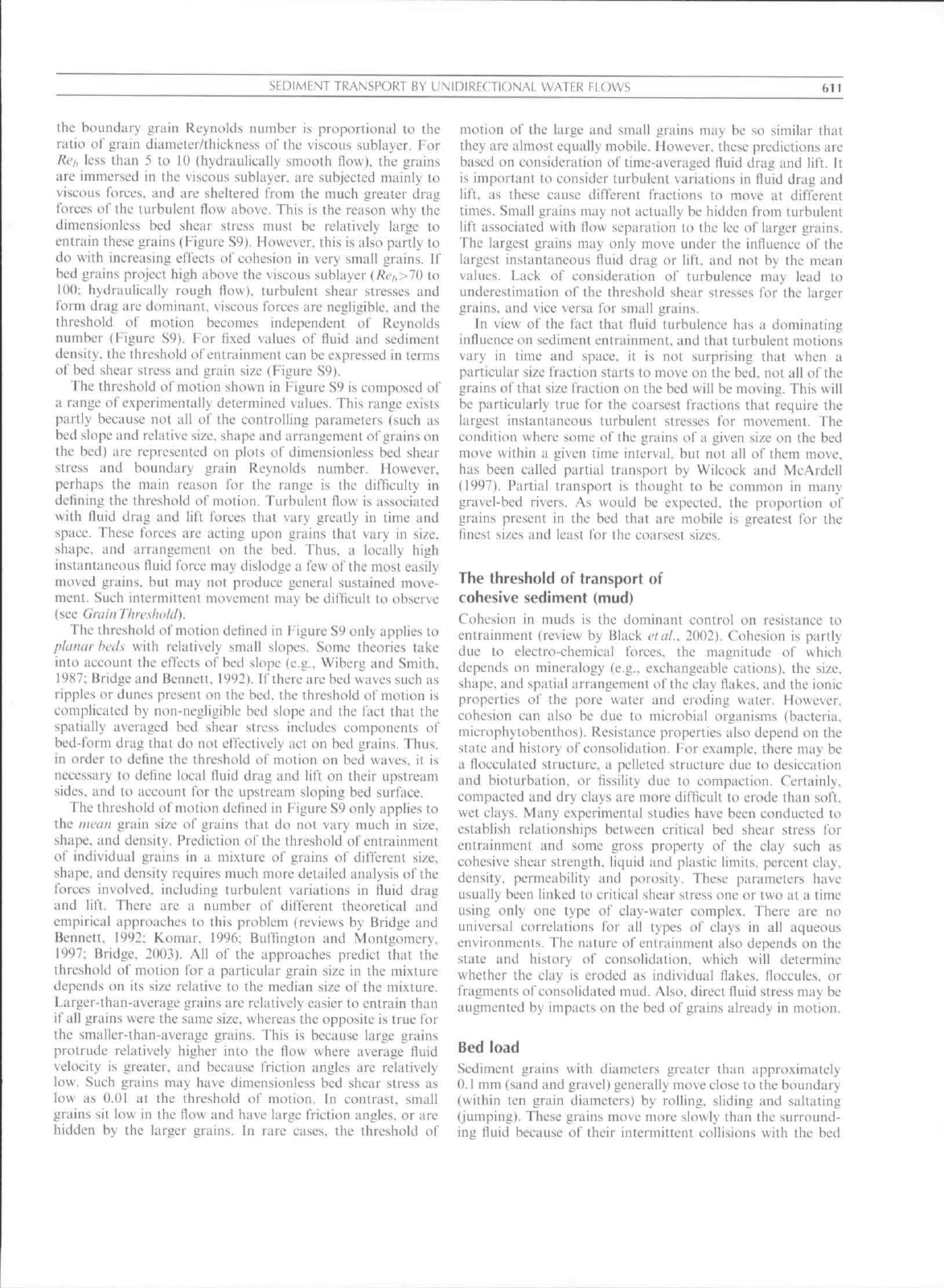

bed shear stress at the threshold of motion are typieally

between 0,03 and 0,06 (Figure S9: based on numerous

theoretical and experimental studies, reviewed in Miller efal,.

1977;

Yalin and Karahan, 1979; Wiberg and Smith. 1987:

Bridge and Bennett, 1992: Komar, 1996: Buttington and

Montgomery. 1997). The exact value of 0 depends on the

degree to which the grains are immersed in the viscous

sublayer, the relative magnitude ofthe lift eomponent of drag.

the bed slope, and the relative size, shape and arrangement of

the grains in the bed.

The boundary grain Reynolds number (Figure S9) is

defined as

Re,, = U*

where (/* = ^

viscosity, and

10

1

01

0,001

(Eq. 7)

TJP)

is the shear velocity, v is kinematic

is the thickness of the viscous sublaver. Thus,

Suspmded loEd

10-

(Pa)

Suspended IcaJ

No movement

0,001 0,1

10

100

Figure S9 Threshold of motion (shaded zonesi for bed load .ind

suspended load for the case of cohesionless sediment. Bawd on

numerous experimental dnd [heorelicdl studies discussed in text.

StDIMfNT TRANSPORT BY UNIDIRFC TIONAL WATl-.R nCAVS

611

the boundary grain Reynolds number is proportional to the

ratio of grain diameter/thickness ol'the viscous sublayer. For

Reh less than 5 to 10 (hydratilieally smooth flow), the grains

are immersed in the viscous sublayer, are subjected mainty to

viscous forces, and are sheltered frotn the much greater drag

forces of the turbulent flow above. This is the reason why the

dimensionless bed shear stress must be relatively large to

entrain these grains (Figure S^). However, this is also partly to

do with inereasing effects of cohesion in very small grains. If

bed grains project high above the viscous sublayer {Reh>10 to

100:

hydrauliealiy rough flow), turbulent shear stresses and

form drag are dominant, viseous forces are negligible, and the

threshold of motion beeotnes independent of Reynolds

number (Figure S9). For fixed values of fluid and sediment

density, the threshold ol entrainment can be expressed in terms

of bed shear stress and graiu si/e (Figure S91,

The threshold

oi"

motion shown in Figure S9 is eoniposed of

il range of experimentally determined values. This range exists

partly because not all of the controlling parameters {sueh as

bed slope and relative size, shape and arrangement of grains on

the bed) are represented on plots of dimensionless bed shear

stress ;iiid boundary grain Reynolds number. However,

perhaps the main reason for the range is the difficulty in

defining the threshold of motion. Turbulent flow is assoeiated

wilh fluid drag and lift forces that vary greatly in titne and

space. These forces are acting upon grains that vary in size,

shape, and arrangement on the bed. Thus, a locally high

instantaneous fluid foree may dislodge a few ofthe most easily

nuned grains, but may not produce general sustained move-

ment. Such intermittent movement may be difflciilt to observe

(sec Grain Threshold).

The threshold of motion detined in Figure S9 only applies to

planar beds with relatively small slopes. Some theories take

mto account the effeets of bed slope (e.g., Wiberg and Smith.

19S7;

Bridge and Bennett. 1992). If there are bed waves such as

ripples or dunes present on the bed, the threshold of motion is

complicated by non-negligible bed slope and the faet that the

spatially ;i\eraged bed shear stress includes components of

bed-form drag thai do not effectively act on bed grains. Thus,

ill order to define the threshold of motion tin bed waves, it is

necessary to define loeal fluid drag and lift on their upstream

sides,

and lo aeeount for the upstream sloping bed surfaee.

The threshold of motion delincd in t igure S9 only applies to

the mean grain size of grains that do not vary much in size,

shape, and density. Prediction ofthe threshold of entrainment

of individual grains in a mixture of grains of different si/e.

shape, and density requires much more detailed analysis of the

forees involved, ineluding turbulent variations in fluid drag

and lift. There are a number of dilTerent theoretical and

empirical approaches to this problem (reviews by Bridge and

Bennett, 1992: Komar, 1996; Buffington and Montgomery.

1997;

Bridge. 2003). All ofthe approaehes predict that the

threshold of motion for a particular grain size in the mixture

depends on its size relative to the median size ofthe mixture.

Larger-than-average grains are relatively easier to entrain than

il ali grains were the same size, whereas the opposite is true lor

the smaller-than-avcrage grains. This is because large grains

protrude relatively higher into the llou where average fluid

velocity is greater, and because friction angles are relatively

lou. Such grains may have dimensionless bed shear stress as

low as 0,01 at the threshold of motion. In contrast, small

grains sit low in the flow and have large friction angles, or are

hidden by the larger grains. In rare cases, the threshold of

motion of the large and small grains may be so similar that

they are almost equally mobile. However, these predictions are

based on consideration of timc-avcraged fluid drag and lift, lt

is important to consider turhulettt variations in fluid drag and

lift, as these cause different fractions to move at different

times.

Small grains may not actually be hidden from turbulent

lift associated with flow separation to the lee of larger grains.

The largest grains may only move under the influence of the

largest instantaneous fluid drag or lift, and not by the mean

values. Lack of consideration of turbulenee may lead to

underestimation ofthe threshold shear stresses for the larger

grains, and vice versa for small grains.

In view of the fact that fluid turbulence has a dominating

influence on sediment entrainment, and that turbulent motions

vary in time and spaee. it is not surprising that when a

particular size fraction starts to move on the bed. not all ofthe

grains of that size fraetion on the bed will be moving. This will

be particularly true for the coarsest fractions that require the

largest instantaneous turbulent stresses for movement. The

condition where some ofthe grains ofa given size on the bed

move wilhin a given time interval, but not all of them move,

has been called partial transport by Wilcock and McArdell

(1997),

Partial transport is thought to be common in many

gravel-bed rivers. As would be expected, the proportion of

grains present in the bed that are mobile is greatest for the

finest sizes and least for the coarsest sizes.

The threshold of transport of

cohesive sediment (mud)

Cohesion in muds is the dominant eontrol on resistanee to

entrainment (review by Black

etaf,.

2002). Cohesion is partly

due to eleetro-chemical forces, the magnitude of which

depends on mineralogy (e.g.. exchangeable cations), the size,

shape, and spatial arrangement of the elay flakes, and ihe ionic

properties of the pore water and eroding water. However,

cohesion can also be due to microbial organistns (bacteria,

microphytobenthos). Resistanee properties also depend on the

state and history of et>nsolidation. For example, there may be

a flocculated structure, a pelleted structure due to desiccation

and bioturbation, or fissility due to compaction. Certainly,

eompacted and dry clays are more difficult to erode than soft,

wet clays. Many experimental studies have been eonductcd to

establish relationships between critical bed shear stress for

entrainment and some gross property of the clay sueh as

eohesive shear strength, liquid and plastic limits, percent elay,

density, permeability and porosity. These parameters have

usually been linked to critical shear stress one or two at a time

using only one type of clay-water complex. There are no

universal correlations for all types of clays in all aqueous

environments. The nature of entrainment also depends on the

state and history of eonsolidation. which will determine

whether the clay is eroded as individual flakes, floccules, or

fragments of consolidated mud. Also, direet fluid stress may be

augmented by impacts on the bed of grains already in motion.

Bed load

Sediment grains with diameters greater thau approximately

0.1 mm (sand and gravel) generally move close to the boundary

(within ten grain diameters) by rolling, sliding and saltating

(jumping). These grains move more slowly than the surround-

ing fluid because of their intermittent collisions with the bed

SEDIMFNT TRANSI'ORT BY UNIDIRECTIONAI WATFR MOWS

and eaeh other. These grains form the bedload. The continuing

movement of bed-load grains requires the existence of an

upward dispersive force (Bagnold. 1966. 1973) that must be

exactly balanced by the immersed weight ofthe moving grains

for steady bed-load transport. The two ways of dispersing

grains normal to the flow boundary are by collisions between

the grains and bed. and by fluid lift.

Saltation is the dominant mode of bed-load transport, with

rolling and sliding only occurring near the threshold of

entrainment and between individual jumps (summary in

Bridge and Dominie, 1984). As the downstream veloeity of

rolling and sliding grains inereases over an irregular bed. the

grains are frequently launehed upward as they are forced over

protruding immobile grains, thus initiating saltations. At low

transport rates, saltation trajectories arc unlikely to be

interrupted by collisions with other moving grains. However,

at higher sediment transport rates (greater concentration of

bed-load grains), saltations will be more interrupted by

collisions between moving grains, and these collisions will

contribute to the upward dispersive stress.

Both turbulent and non-turbulent fluid lift forces can act on

bed-load grains (sumtiiary in Bridge and Dominic. 1984). Non-

turbulent lift forces are pressures arising from a net relative

velocity between grains and surrounding fluid. They are caused

by asymmetrical flow around near-bed grains, the redticed

grain velocity relative to the velocity gradient in the surround-

ing fluid (shear drift), and the cfTeets of grain rotation (Magnus

lift).

It is very diffieult to specify their individual contribution to

net lift, particularly when complex grain collisions occur within

the bed load, and when turbulent lift fbrccs are dominant.

As turbulence originates very close to the bed of a stream,

bed-load grains are undoubtedly affected by turbulent lift as

well as by drag. As near-bed turbulent fluctuations increase

with bed shear stress (or shear velocity), grain saltations are

modified more and more by turbulence as bed shear stress and

sediment transport rate increase. Turbulence affects differenl

sized grains in different ways, depending on immersed weight

of grains and the direction and magnitude of ttirbulent fluid

motions (review by Bridge, 2003),

The mean height ofthe bed-load (saltation) zone eontrols the

effective roughness ofthe bed. and must be known to calculate

bed-load transport rate. Many approaches to determining the

mean height of the bed-load zone are theoretical-empirical,

predicting that saltation height increases with sediment size and

some measure of sediment transport rate (reviews by Bridge

and Dominie. I9H4; Bridge and Bennett, 1992; Bridge. 2003). In

general, saltation height is proportional to grain diameter.

Theoretical models of saltation trajeetories of individual grains

have also been used to determine saltation height. However, it

is very difficult to model the influenee on saltating grains of

turbulent fluid motions, and the effects on grain trajectories of

impacts among grains are not considered.

Suspended load

Grains of clay, silt and very fine sand generally travel within

the flow, supported by upward-directed fluid turbulence. The.se

grains, the suspended

load,

travel at approximately the same

speed as the surrounding fluid beeause they are not decelerated

by intermittent eollisions with the bed. Maintenance of a

suspended-sediment load requires the existence of a net

upward-directed (luid stress to balanee the immersed weight

of the suspended grains. This can only arise if Ihe vertical

component of turbulence is anisotropie (Bagnold. 1966), This

anisotropy can be associated with the turbulent bursting

phenomenon, whereby sediment is suspended mainly in

vigorous upward ejections of fluid, and then returns to the

bed under the influence of gravity and downward-directed

turbulent motions. This idea is supported by experimental

observations of discrete clouds of suspended sediment

associated with turbulent ejeetions, and the wavy trajectories

of suspended grains (review in Bridge, 2003). However,

sediment is also suspended in vortices generated by eddy

shedding lYom the separated boundary layer in the trough

regions of ripples and dunes. With dunes, these vortiees can

reach the water surface as boils or kolks. Provided that a grain

experiences more upward directed turbulent motions than the

combination of downward directed turbulent motions and

gravitational settling, it will remain in suspension.

Two criteria for the suspension of sediment are:

rms v+ > f^^ (Eq. 8)

rms v'l - ;7);.vv' > V^ (Eq. 9)

where rms v' is the root mean square of the vertical turbulent

fluctuations ofthe flow, the subscripts refer to upward motions

(

+

)

or downward motions (-), and

V^.

is the mean terminal

settling veloeity of the sediment. The first criterion indieates

that, as long as time-averaged upward-dirceted turbuleni

velocities are in excess of l'\,. sediment ean be moved upward

within the flow, even ifthe sediment eventually returns to the

bed. The second eriterion indicates that for a grain to remain

in suspension the time-averaged upward-direeted turbulent

velocity experienced by the grain must exeeed the downward-

direeted veloeity plus the settling velocity ofthe grain. There is

an empirical relationship between the time-averaged upward

and downward directed velocities and the overall rms v' near

the bed. sueh that the two suspension criteria above beeome

armsy >

where (/ is 1,2 to 1,5

hrmsv' > l'^ where h is 0.4 to 0,9

(Eq. 10)

(Eq, 11)

Furthermore.

rmsv'IU*

^ I near the bed. so that ihe suspension

criteria for near-bed conditions are

aU* >

V^.

and hU* > V^

(Eq, 12)

Also,

as the shear veloeity aud the settling velocity can be

related to the dimensionless bed shear stress and the grain

Reynolds number, the threshold of suspension can be

represented on the threshold of enlrainment diagrams

(Figure S9). As the bed shear stress varies in time and space,

sediment with a particular settling veloeity (or grain size)

may travel as both bed load and sediment load. This is

particularly true ofthe sand sizes coarser than about O.I mm.

This is called intermittentlysiispeiulcdload.

The i\'ashh)adis eommonly distinguished from suspendedhcd-

materialload. Wash load is very finegrained and suspended even

at low flow velocity. Furthermore, the volume eoneentration of

wash load does not vary much with distance from the bed.

whereas the volume concentration of suspended bed-material

load decreases markedly with distance from the bed. Whereas the

suspended bed-material load originates from the bed. the wash

load can come from bank erosion and overland flow. Perhaps, the

iwo different suspension criteria effectively distinguish wash load

from suspended bed-material load.

SFDIMENT TkANSK)KT BY UNIDIRECTIONAl WATER FLOWS

61 ;

Effect of sediment transport on flow characteristics

In uniform, uirbulent boundary layers over planar beds with

sedimenl transport, it is generally recognized that the moving

sediment modifies flow charaeteristies. Many seientists in the

1940s to 1960s (reviewed in ASCE. 1975) suggested that the

presenee of sediment in the flow caused a reduction in

turbulent eddy sizes and in the degree of turbulent mixing.

The main effeei of sediment on turbulence was expeeted to be

near the bed where sediment coneentration is highest. These

conclusions have been substantially eonfirmed by reeent

studies (review by Bridge. 2003). The nature ofthe interaction

between sediment grains and Iluid ttirbulenee aetually depends

on the relative veloeity of the grains and the turbulent fluid

(which depends on grain weight), and the relative size of the

grains and the turbulent eddies. Ifthe relative velocity ofthe

grains ;md iluid is large (i.e.. large, heavy grains), turbulence

intensily (partieularly ofthe smallest eddies) is increased as a

result of vortex shedding or inertial effects. If the relative

velocity is small (i,e., small grains), turbulence intensity is

decreased as the turbulent energy is transferred to the grains.

More reeently it has been suggested that turbulent mixing is

suppressed because ofthe density stratification hrought about

by an upward deerease in suspended sediment concentration,

as represented by a flux Richardson mimhcv. However, this idea

is not well supported by natural data (Bennett daf. 1998). In

natural Hows, bed forms have an overwhelming effect on

turbulence intensities and eddy sizes.

Sediment transport rate (bed load)

The sediment

tran.sport

rate is the amount (weight, mass, or

volume) of sediment that can be moved past a given width of

flow in a given time. The sediment transport rate controls the

development of bed forms such as ripples and dunes, the

nature of

crav/V)/;

and deposition, and the dispersal of physically

transported pollutants. There is a vast and eomplicated

literature on the subject (reviews in

Graf.

1971; ASCFi, 1975;

Yalin. 1977; Van Rijn. 1984a,b,c: Chang. 1988: and many

others) and only the basies will be presented here.

Bed-load transport rate can be expressed as

/. =

WuH

(Eq, 13)

where //, is the bed-load transport rate as immersed weight

passed per unit width, H'is the immersed weight of bed-load

grains over unit bed area, and ti,, is the mean bed-load grain

veliK'ity. The contacts beiween bed-load grains and the bed

result in resistance to forward motion. Therefore, the fluid

must exert a mean downstream force on the grains to maintain

their steady motion. For bed-load transport on a bed of slope

angle fi. the force balance parallel to the bed can he expressed

T,, + M^'sin fi = T

(Eq, 14)

where r,, is ihe bed shear stress applied to the moving grains

and immobile bed (but excluding form dtag due to bed forms

and banks), IVsin fi is the down-slope weight component of

the tiioving grains per unif bed area (with sin/J positive ifthe

bed slopes down flow), T is the shear resistance due lo the

moving bed load, and T, is the residual shear stress carried by

the immobile bed. Bed-load shear resistance can be expressed

where /•'/ is the net lltiid lifl on bed-load grains per unit bed

area, taken as resulting dominantly from anisotropie turbu-

lenee. and given by

Fl =

W{hU*/V^f

(Eq. 16)

and tan y is the dynamic friction coefficient, l-rom experiments

on shearing of grains in dry grain (lows and eoaxial drums,

where volumetric grain eoneentralions are approximately 0.5,

tan

X

eommoniy lies between 0,4 and 0,75 (review in Bridge

and Dominic. 1984; Bridge and Bennett. 1992). The residual

fluid stress r,, equals the bed shear stress at the ihreshold of

motion r,. according to Bagnold (1956. 1966). Thus, once the

applied fluid stress exceeds the value neeessary for entrain-

ment, grains will be entrained until the bed-load resistance

caused hy their motion reduces the applied fluid stress to the

threshold value of r,,. Therefore, the immersed weight of grains

moving per unit bed area is given, from equations 14 to 16, as

r,,

—

r,

tan

X

cos

fi

-

-sin/f

(Eq. 17)

As the threshold of suspension is reaehed. the term in square

brackets approaehes zero, indicating that the weight of bed-

load grains approaches infinity. In reality, this situation eould

not arise because high grain concentrations in the bed load

layer would occlude fhe bed from fluid drag and lift, thus

limiting the weight of bed-load grains (e.g., Bagnoid. 1966),

Furthermore, high concentrations of near-bed grains modify

turbulenee characteristics above the bed. In many natural

flows, the bed-slope is small enough such that sin/f tends to

zero,

and the term in square brackets tends to I. so that

(Eq. 18)

tana

The mean velocity of ihe average bed-load grain is given by

Uh

=

Un

-iiK (Eq. 19)

where ti/, is the time-averaged Row velocity at the level of

effeetive drag on the grain, and i/« is the relative velocity ofthe

fluid and the grain. The relative velocity is that at which the

fluid drag plus down-slope weight component on the grain is in

equilibrium with the bed-load shear resistanee:

Fn -^

/"V,

sin/i

—

F(,

tan x(cos/( - (hiU/ Vg)') (Eq, 20)

Using the general drag equation for Fp. and the fact that F^ is

equal to the fluid drag at a grain's terminal settling velocity,

results in

"« = KL.(tana(cosp - (nO'*/!^^)") - sin/i) " (Eq.21)

Finally, as ui)fU*=a. the mean velocity of hed-load grains is

given by

(Eq.22)

(Eq, 23}

Furthertnore. as the grain velocity must be zero at the

threshold of grain rnotion, this equation may also be written as

or approximately as

J,/, = aV* -

-

(H'cos/f-

(Eq. 15)

x/tan

y.,

(Eq.24)

614

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT HY UNIDIRFCTIONAL WATER ELOWS

Determination of the value of a requires knowledge of the

height above the bed levet ofthe effective drag on the grains

(that varies with the saltation height) and details of the

near-bed velocity profile. There have heen numerous attempts

to relate saltation height to some measure of flow stage (review

in Bridge and Bennett. 1992). The flow velocity at the height of

effective drag depends on whether the flow is hydraulically

smooth, transitional or rough. For transitional and rough

flows, a is ahout 8-12 (Bridge and Dominic. 1984). Also, at the

threshold of suspension, the grain velocity approximately

equals the fluid velocity and

Uh

= aU'. which is another

suspension criterion.

Thus,

the final approximate hed-load transport equation

can he written as

a

tan 1

(Eq, 25)

Equations of this form have heen developed, using similar

principles, hy a number of workers (details in Bridge and

Dominic, 1984), This equation agrees very well with experi-

mental dafa for flows over plane heds. For low sediment

transport rates (lower-stage plane beds), alXany. is approxi-

mately 10. but is approximately 17 for high sediment transport

rates (upper-stage plane beds). For beds covered with bed

forins such as ripples and dunes, the bed-load transport

equation can be applied by determining the average bed shear

stress over a number of bed forms, and to remove the part of

the total average stress that is due to form drag in the lee ofthe

bed forms, because it is ineffective in moving bed-load grains

(e.g., Engelund and Hansen. 1972: Engelund and Fredsoe,

1982;

Nelson and Smith. 1989), However, bed-load transport

rates associated with ripples and dunes can also be calculated

from knowledge of their mean height and downstream

migration rate.

The bed-load transport theory developed above is for mean

flow and sediment characteristics, but it can he adapted for use

with heterogeneous sediment and with temporal variations in

bed shear stress (e.g.. Bridge and Bennett. 1992), In this case, it

is necessary to specify the proportion of the different grain

fraetions available in the bed for transport, and the thresholds

of entrainment and suspension for eaeh ofthe grain fractions.

It is also necessary to speeify the proportion of time that a

particular bed shear stress acts upon the hed-load. requiring a

frequency distribution of hed shear stress. Bridge and

Bennett's (1992) bed-load transport model for heterogeneous

sediment agrees well with natural data. Models such as this

(e.g., Wiberg and Smith, 1989; Parker, 1990) are essential for

quantitative understanding of sediment sorting during erosion,

transport and deposition.

Sediment transport rate (suspended load)

Suspended-sediment transport rate at a point in the flow is

commonly expressed as

/, =u.C (Eq, 26)

where »,. is the average speed ofthe sediment (approximately

the same as the fluid velocity), and C is the volume

concentration of suspended sediment. The units of /\ are

therefore volume of sediment transported per unit cross-

sectional area normal to the tlow direetion per unit time. The

vertical variation of the velocity of suspended sediment and

fluid can be calculated using an appropriate velocity profile

law (e.g.. the law of the wall). Calculation of the vertical

variation of C in steady, uniform water Hows is traditionally

based on the balance of downward settling of grains and fheir

upward diffusion in turbulent eddies, i.e.,

V^C + i:,iiC/dy =

O

(Eq, 27)

where the first term is the rate of settling ofa particular volume

of grains per unit volume of fluid, the second term is rate of

turbulent difTusion of sediment per unit volume, and (, is the

diffusivity of suspended sedimenl (equivalent to a kinematic

eddy viscosity. 0- This balance ean also be written for

individual grain fractions. In order to determine C at any

height above the bed, v. it is necessary to calculate the vertical

variation in (,. Assuming that

(„.

= fii, where/i is close to 1, and

that the law of the wall extends throughout the flow depth,

results in the well-known Rouseci/uation

C_

d-y

(I-a

(Eq.

28}

where C,, is the value of Cat i' = (/. This equation predicts that

C decreases continuously and smoothly with distance from the

bed. as would be expected in view of the fad that turbulenee

intensity also decreases with disfanee from the bed. The

distribution of suspended sediment beeomes more uniform

throughout the flow depth as exponent r decreases, fhat is as

settling velocity (grain size) decreases and/or as shear velocity

(near-bed turbulence intensity) increases (Figure SlO). For

example, a decrease in water temperature causes an increase in

fluid viscosity, which may in turn cause a deerease in settling

velocity and an increase in suspended sediment coneentration.

The Rouse equation has been shown to agree with measured

suspended-sediment concentrations in the lower part of stream

flows but eoneentrations tend to be overestimated in the upper

parts (figure S2). This discrepancy is addressed helow.

Some of the assumptions used in developing the Rouse

equation have heen criticized: mainly the choice of velocity

proflle (law of the wall), and the fact that the interaetion

between suspended sediment, fluid properties and turbulence is

not considered. Perhaps the most serious concern with the

Rouse equation is that the sediment diffusivity has rarely been

calculated directly using quantitative observations of the

motion of sediment in turbulent eddies. Thus, there is doubt

about the vertical variation of <^ and /J (e.g.. ASCE. 1975;

Coleman, 1970; Van Rijn. 1984b). Bennett etal. (1998) have

measured turbulent motions of suspended sediment and

concluded that fi is indeed close to 1. However, suspended

sediment concentration in the upper half of the flow depth in

natural flows is eommonly larger than predicted by the Rouse

equation. One reason for this discrepancy eould be that

sediment grains that are suspended to the higher levels in the

flow are not associated with mean turbulence characteristics as

specified in fhe Rouse equation, but with turbulent eddies with

the greatest turbulenee intensities and mixing lengths (Bennett

ei af. 1998). Thus, the Rouse equation, based on average

turbulenee characteristics, may only be strictly applicable for

the lower parts of the flow.

Application of the Rouse equation in praetiee requires

ealeulation of C',, and a. and there are various methods for

doing this (review by Bridge, 2003), Nornialfy. C^ is calculated

at a position within or at the top of the hed-load layer. If bed

waves are present, a can he taken as half bed-wave height or

equivalent roughness height (Van Rijn, 1984c). The mean

volume concentration of grains in the bed-load layer, C,,. is the