Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SABKHA, SALT FLAT, SALINA

585

zone.

This brine pumping process promotes the precipitation

of gypsum in the intercrystalline cavities in the gypsum bed

as vadose cement, which in turn causes the bed to expand

laterally. This generates small-scale buckles in the gypsum

crust and leads to the formation of larger antiform polygonal

ridges (several cms. in height) spaced approximately

2

m

apart ("tepees", see Demicco and Hardie, 1994, figure 161).

Ultimately, the continued lateral expansion of the gypsum

layer gives rise to fracturing at the polygon boundaries and

the development of overthrusting and underthrusting at the

ridges. In turn, these thrust fracture zones act as localized

high permeability conduits for enhanced evaporative pumping

of brine up through the vadose zone. When these brines

emerge at the surface, they evaporate rapidly to dryness and

deposit finely crystalline gypsum beneath the fractured

ridges, adding to their volume and height, a process that

produces diapir-like masses of gypsum beneath the ridges. This

tepee-forming process is only halted by the next flooding

event when a new gypsum pan cycle begins. The cycle starts

again as seawater, undersaturated with respect to gypsum,

floods over the dry gypsum pan partially dissolving the

buckled gypsum surface layer, enlarging existing intercrystal-

line cavities and rounding the margins of exposed euhedral

gypsum crystals. This dissolution phase soon results in the

floodwaters becoming almost saturated with respect to

gypsum. This allows erosion, transportation and redeposition

on the pan of loose gypsum crystals and cleavage fragments

as sand and gravel sheets. Isolated patches of gypsum sands

may be sculptured into classic unidirectional bedforms and

wave ripples. Ultimately, as the flood waters subside, seawater

left ponded on the gypsum pan evaporates to the point of

gypsum saturation and a new gypsum bed is formed. During

this stage of this new gypsum precipitation cycle, the

dissolution features of the underlying gypsum bed are

"repaired" by syntaxial overgrowth (Demicco and Hardie,

1994,

flgure 154C) and by cementation on the walls of

intercrystalline cavities.

Most signiflcantly, the layered gypsum of the Baja

California supratidal flats

Itas

not been converted

to

nodutar an-

tiydrite, yet it has all the basic morphological features found

in the Persian Gulf layered nodular anhydrite, that is, cm-

scale layers of detrital sediment alternating with cm-scale

layers of gypsum displaying enterolithic folding, diapiric

structures, and polygonal tepees with overthust and under-

thrust "faults" located at the buckled tepee ridges. At the

landward margin of the sabkha, gypsum crystals are in the

eariy stages of dehydration to anhydrite (Castens-Seidell,

1984).

It is easy to imagine that with time, as the Baja

California tidal flats continue to prograde seaward, complete

conversion of these gypsum layers to anhydrite will mimic the

spectacular evaporite features observed in trenches cut into

the landward regions of the Persian Gulf sabkha. By analogy,

then, ttie Persian Gutf layered nodutar aniiydrtte woutd have

been formed by detiydration of tayered gypsum ttiat crystattized

subaqueousty in .stiattow ephemerai gypsum pans, inheriting

the principal deformation structures from the parent

gypsum bed. The Persian Gulf "gypsum pan" deposits,

converted completely to anhydrite, are now defunct. They

have been eroded by deflation and covered by windblown

sands as the tidal flats have prograded seaward over the past

5000 years. This same model could apply to other, more

ancient, layered nodular anhydrite deposits in the geological

record.

For each flood event, as evaporative concentration proceeds

and the shallow saline "lake" shrinks, the surface brine body

may reach saturation with respect to halite, forming an

eptiemerat hatite pan at the center (the "buUseye") of the

gypsum pan. All the essential characteristics outlined above for

ephemeral gypsum pan deposition have been documented

and described by Lowenstein and Hardie (1985) for bedded

halite in the ephemeral salt pan that lies in the center of the

Baja California gypsum pan (see also pioneering study of

Shearman, 1970). Significantly, however, the halite of the salt

pan on this arid tidal flat is short-lived because, typically, the

subaerially-exposed, highly soluble halite crusts of the salt

pan are completely dissolved by large inundations of sea-

water driven onshore by strong storms. When the onshore

winds subside, most of the floodwaters drain off the tidal

flats carrying dissolved NaCl back to the sea, leaving the

relatively insoluble gypsum crusts essentially intact. This

observation suggests that we should not expect to flnd thick

accumulations of salt pan halite capping arid tidal flat cycles.

Instead, such depositional cycles would be capped by

ephemeral gypsum pan deposits (see Anhydrite and Gypsum,

flgure

A8).

Analogous processes and products can occur in nonmarine

closed basins on ephemeral playas. The main difference would

be that the floodwaters would be relatively dilute meteoric

waters with a much greater potential for widespread dis-

solution during the initial flooding stage. In addition, for

gypsum to be a signiflcant precipitate, the inflow waters must

be of the "neutral" Na-K-Ca-Mg-S04-Cl chemical group (see

Evaporites), In modern ephemeral playa settings in arid

closed basins, halite pans are far more abundant than gypsum

pans because in such basins there are no outlets that would

allow flushing away of the halite formed in the "bullseye" of

the pan, as occurs on marine supratidal flats as described

above for the Baja California sabkha.

Lawrence A. Hardie

Bibliography

Butler, G.P., 1970. Holocene gypsum and anhydrite of the Abu Dhabi

sabkha: an alternative explanation of origin. In Rau, J.L., and

Dellwig, L.F. (eds.). Proceedings of ttie Ttiird Satt Symposium,

Cleveland: Northern Ohio Geological Society, pp. 120-152.

Castens-Seidell, B., 1984. Ttie Anatomy of a Modern Marine Siticietastic

Sahtctia in a Rift Vattey Setting: Norttiwest Gutf of

Catifornia,

Baja

Catifornia, LInpublished PhD dissertation, Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University, 386pp.

Curtis, R., Evans, G., Kinsman, D.J.J., and Shearman, D.J., 1963.

Association of dolomite and anhydrite in the recent sediments of

the Persian

Gulf.

Nature, 197: 679-680.

Demicco, R.V., and Hardie, L.A., 1994. Sedimentary Struetures and

Earty Diagenetic Features of Stiattow Marine Carbonate Deposits.

SEPM Atlas Series Number 1, 265pp.

Hardie, L.A., and Shinn, E.A., 1986. Carbonate depositional environ-

ments modern and ancient, part 3: tidal flats. Cotorado Schoot of

Mines Quarterty, 81: 1-74.

Kinsman, D.J.J., 1969. Modes of formation, sedimentary associa-

tions and diagnostic features of shallow water and supratidal

evaporites. Ameriean As.iociation of Petroteum Geotogists Buttetin,

53:

830-840.

Lowenstein, T.K., and Hardie, L.A., 1985. Criteria for the recognition

of salt pan evaporites. Sedimentotogy, 32: 627-644.

Shearman, D.J., 1970. Recent halite rock, Baja California, Mexico.

Institute of Mining and

Metatturgy,

Transactions, B79: 155-162.

Warren, J.K., 1989. Evaporite Sedimentotogy, Prentice Hall.

586

SALT MARSHES

Cross-references

Anhydrite and Gypsum

Desert Sedimentary Environments

Evaporites

SALT MARSHES

Marshes are wetland environments dominated by herbaceous

plants. Sea-coast tidal salt marshes are a specific type found in

sheltered back-barrier, estuarine and deltaic settings where

they form important environments and ecosystems. They

contain halophytic (salt tolerant) grasses, rushes, sedges and

forbes that are able to survive in intertidal and fringing

environments hostile to upland vegetation. Mature marshes

are dominated by living plants and are usually constructed on

peats,

the partially preserved remnants of former rnarsh plants.

Marshes usually stand higher than flats, from mid-tide to

highest spring tides, and are often best developed as a broac}

flat within a few decimeters of mean high water (MHW).

Marsh sediments have been used as tools for stratigraphic

reconstruction of coastal evolution (Kraft, 1971) and bases for

interpretation of Holocene sea-level change (Redfield and

Rubin, 1962; Kraft and Belknap, 1977; van de Plaasche, 1986;

Gehrels etal., 1996) using radiocarbon dating of peats built

from plants that grow near mean high sea level.

Morphology

The morphology of salt marshes depends on tidal range, slope

of substrate, and geometry of the enclosing embayment (Kelley

et al., 1988). The simplest salt marsh, often an early or

ephemeral phase, is created through the colonization of tidal

flats with halophytes. Later successional phases create more

complex morphology, to a large degree controlled by the

ecology of the vegetation. Fringing marshes occur adjacent to

uplands. They may occupy relatively steep margins in tidal

rivers and estuaries, particularly in rocky or paraglacial

regions such as New England. More widespread are those on

the landward edge of lagoons, on low-angle coasts. Estuarine

and Fluvial salt marshes are elongated in a marginal fringe

parallel to the channel and the upland. They may vary from

fringing to broad types. Back-barrier marshes are broad and

may fill the majority of backbarrier systems (South Carolina

tide-dominated mesotidal barrier systems, many New England

marshes), or may occur as a relatively narrow band on the

lagoon side of wave-dominated microtidal barriers (Long

Island, New Jersey, Delaware). Broad, well-developed marshes

are generally flat, graded to near mean high water

(

+

30

cm or

less),

with the majority of their area in the high marsh zone.

Fringing marshes are steeper, because they compress all the

marsh zones, controlled by frequency of flooding, into a

narrower band.

Ecosystems

Within a marsh there are commonly: (1) a low marsh,

colonizing zone; (2) a broad high marsh; (3) tidal creeks; (4)

creek levees or margins; (5) salt pannes; (6) higher-high marsh;

and (7) upland fringe. Marshes are generally zoned by the

ecology of the plants (Niering and Warren, 1980). Primarily

tolerance of the halophytes is to frequency of tidal inundation.

Some plants have specialized structures in subsurface rhizomes

and roots for gas transport, and glands for excreting excess

salt. In some fringing marshes with high tidal ranges, the

zonation can be very sharp. In broad marshes or in lower tidal

ranges, the zonation tends to be more mosaic in nature, and

controlled by proximity to tidal creeks.

Low salt marsh has a very restricted diversity, dominated by

salt marsh cord grass Spartina alterniftora in much of North

America and other areas. Low salt marsh occurs from Mean

Sea Level (MSL) to MHW, and is flooded by most tides. High

salt marsh is more diverse, generally from MHW to SHW,

flooded every fortnight. High salt marsh is more diverse, and

varies by climate zone. In New England high marsh is

dominated by Spartina patens grass, in the mid-Atlantic by

S. patens and Distichlisspicata, in Georgia and Florida by the

rush Juncus roemarianus. On the Pacific coast of the US, it is

dominated by Salicornia pacifica, while Pucinellia maritima is

corninon in the British Isles.

Higher high marsh is flooded a few times per month,

occurring above MHW to Spring High Water. The ecology

also yaries by latitude. In Maine the dominant plant is

generally Juncus gerardii, while the Mid-Atlantic is less

distinct, with Distichlis spicata and shrubs Ivafructescens and

Baccharushalimifolia important.

Upland Fringe is primarily a freshwater system, flooded

only during storms or astronomical highest tides, several times

per year. Cattails (Typha angustifolia) predominate in the

Upland Fringe in Maine, while in the mid-Atlantic Fhragmites

australis is dominant.

F.

australis is an aggressive colonizer of

disturbed lands, and in the last few decades has expanded

greatly in mid-Atlantic marshes, on dredge spoil islands, and is

being carried to marshes in northern New England, particu-

larly near major roads.

Marshes may also grade from primarily saline systems, as

described above, to more brackish and freshwater systems

along an estuary. Many species of sedges such as Scirpus and

Carex characterize these transitional brackish marshes. Salt

pannes are flooded low areas in high marsh, with variable

salinities that vary from fresh to hypersaline. Their origins are

controversial, but usually ascribed to "rotten spots" or ice

plucking. They are dominated by cyanobacterial mats, and

fringed by Salicornia spp., and are a critical ecosystem for

larval and juvenile fish.

Processes

Marshes grow through

in

situ primary production, from roots,

rhizomes, and stems of living plants, but also build up through

accumulation of organic detritus. Most salt marshes are

composed not of pure organic peat, but have a majority of

inorganic sediment that is carried into the marsh in suspension

(or by ice rafting). "Peat" is a field term for fibrous organic

rich sediments found in marshes, but its true definition (>50

dry weight percent organic carbon) is found mainly in

freshwater bogs. Highly fibrous New England marsh peats

often contain less than 10 percent organics by dry weight

(although 90 percent water and organics by volume). New

England marshes are very firm and fibrous, Georgia and

Florida marshes are muddy or sandy, while mid-Atlantic

marshes are intermediate in composition.

SALT MARSHES

587

Tidal currents predominate in ctiannets. Flow is progres-

sively channelized during late ebb through early flood tides,

whereas sluggish sheet flow predominates at high water over

broad marshes. Blocks constantly slump from margins of

creeks, particularly in New England type marshes (due to high

tidal range ice effects). However, rapid growth and sediment

accumulation in the low marsh environment builds up and

heals the slump, resulting in only slow channel migration.

Clastic sediments in fringing or narrow marshes often fine

seaward, with lesser influence of runoff from upland sources.

This inorganic sediment is extracted from suspension by:

(1) direct settling from suspension—enhanced by a quiet water

baffling effect, increased boundary layer thickness caused by

the plants; (2) peiletization by organisms (mollusks, decapods,

worms) and trapping in organic films; (3) adhering to grass

stems,

washed off by rain or accumulated as the plant dies; and

(4) ice rafting in colder climates.

Broad marshes receive sediment from tidal creeks and may

have coarser-grained levees, fining toward their interiors.

Sedimentation rates in high marshes are an order of magnitude

higher at the creek margin than the interior, due to supply.

Sedimentation rates on low marsh are another order of

magnitude higher (e.g.. Wood et at, (1989) found sediment

accumulation rates up to

8

cm per year in low marsh-tidal

fiat colonization zone, 0.5 cm per year in fringing marshes, and

2mm/yr or less in broad marshes). Thus, broad marsh

accumulates in equilibrium with sea-level rise and local

compaction of marsh, while low marsh can colonize and

accumulate much more rapidly.

Autoeompaction occurs as a marsh compresses under the

weight of accumulating sediment and through decay. Organic

structures rot to some degree, but cellulose is preserved in

saturated, anoxic, and lowered pH conditions. Kaye and

Barghoorn (1964) demonstrated autoeompaction to 40 percent

of original cross-sections in predominantly freshwater marsh

sediments, while Belknap and Kraft (1977) showed compac-

tion-displacement of stratigraphic surfaces related to overall

thickness of peats in paleovalleys.

Subfossil plant remains (roots, rhizomes, seeds) are com-

monly preserved well enough to identify species (Kraft etat,,

1979).

Insect parts, diatoms, and pollen are also preserved and

identifiable. Calcareous shells are not commonly preserved,

because of the acidic conditions. Agglutinated foraminifera

fossils are often well preserved, and have become critical tools

in identification of marsh paieoenvironments and as sea-level

indicators (Scott and Medioli, 1978; Gehrels et at., 1996),

providing more precise levels than the plants can.

Environmental evolution and stratigraphy

Frey and Basan (1985) suggest that marshes pass through

stages. They identify: (1) a Youthful stage with mostly S. at-

terniftora, extensive lagoons, and a high accumulation rate;

(2) a Mature stage with approximately equal proportions of

high marsh and low marsh, less lagoon area, and the overall

accumulation rate decreasing; and (3) Old Age, which consists

of almost all high marsh, with poor drainage, and essentially

no lagoon.

Salt marsh stratigraphic evolution depends on creation of

new accommodation space for peat accumulation through

autoeompaction and sea-level rise. Rising sea level also allows

transgression of the marsh's leading edge over upland surfaces.

In a classic model of development of New England-type

marshes Mudge (1858) considered upbuilding and encroach-

ment on the land (transgressive stratigraphy) in an environ-

ment of subsidence. Conversely, Shaler (1885) emphasized the

progradation of marshes through colonization of flats and

lagoons (regressive stratigraphy). Redfield (1972) investigated

Barnstable marsh, behind the Sandy Neck spit on Cape Cod,

Massachusetts, and found stratigraphy supporting both the

Shaler and Mudge models, in a setting of relative sea-level rise,

with expansion over mudflat and encroachment onto the

upland. Recent work supports this conclusion, but it is clear

that there are more complex relationships to rates of sea-level

change and sediment introduction in New England salt

marshes (Gehrels etat., 1996).

Conclusions

Present knowledge of marsh environments provides a solid

basis for facies models in estuarine, deltaic, and barrier

settings. Sea-level change analysis is firmly established for

general trends. Current research is focused on extracting the

most details and establishing the greatest accuracy possible for

addressing climate change on the millennial to decadal scale.

Debates continue over limits of accuracy and precision of

plant, foraminiferal and other indicators (Kelley etai., 2001;

van de Plassche, 2001), but it is clear that salt marshes contain

a rich record of climate proxies.

Daniel F. Belknap

Bibliography

Belknap, D.F., and Kraft, J.C, 1977. Holocene relative sea-level

changes and coastal stratigraphic units on the northwest flank of

the Baltimore Canyon Trough geosyncline. Journat of Sedimentary

Petrotogy, 47: 610-629.

Gehrels, W.R., Belknap, D.F., and Kelley, J.T., 1996. Integrated high-

precision analyses of holocene relative sea-level changes: lessons

from the coast of Maine. Geotogieat Society of Ameriea Buttetin,

tO8:

1073-1088.

Kelley, J.T., Belknap, D.F., and Daly, J.F., 2001. Comment on "North

Atlantic Climate-Ocean variations and sea level in Long Island

Sound, Connecticut, since 500cal yr A.D.". Quaternary Researcti,

55:

105-107.

Kelley, J.T., Belknap, D.F., Jaeobson, G.L. Jr., and Jacobson, H.A.,

1988.

The morphology and origin of salt marshes along the

glaciated coastline of Maine, USA. Journatof Coastat

Researcti,

4:

649-665.

Kraft, J.C, 1971. Sedimentary facies patterns and geologic history of

a

Holocene marine transgression.

Geotogieat

Society of Ameriea Butte-

tin,

82: 2131-2158.

Kraft, J.C, Allen, E.A., Belknap, D.F., John, C.J., and Maurmeyer,

E.M., 1979. Processes and morphologic evolution of an estuarine

and coastal barrier system. In Leatherman, S.P. (ed.). Barrier

Istands, New York: Academic Press, pp. 149-183.

Mudge, B.F., 1858. The salt marsh formations of Lynn. Proeeedingsof

Essex Institute, 2: 117-119.

Niering, W.A., and Warren, R.S., 1980. Vegetation patterns and

processes in New England salt marshes. Bioscienee, 30: 301-307.

van de Plascche, O., 1986. Sea-tevet Researeti: a Manuat for ttie Cot-

teetion and Evatuation of Data, Norwich, England: Geo Books,

618pp.

van de Plassche, O., 1991. Late Holocene sea-level fluctuations on the

shore of Connecticut inferred from transgressive and regressive

overlap boundaries in salt-marsh deposits: origin of the paleovalley

system underlying Hammock River Marsh, Clinton, Connecticut.

Journatof Coastat

Researeti,

Special Issue, tl: 159-179.

van de Plassche, O., 2001. Reply (to Kelley et at.). Quaternary

Researeti, 55:

108-111.

588

SANDS, GRAVELS, AND THEIR LITHIFIED EQUIVALENTS

Redfield, A.C, 1972. Development of a New England salt marsh.

EeotogicatMonograptis, 42: 201-237.

Redfield, A.C, and Rubin, M., 1962. The age of salt marsh peat and

its relation to recent changes in sea level at Barnstable,

Massachusetts. Proceedings of ttie Nationat Acadamy of Sciences,

48:

1728-1735.

Scott, D.B., and Medioli, F.S., 1978. Vertical zonations of marsh

foraminifera as accurate indicators of former sea levels. Nature,

272: 528-531.

Shaler, N.S., 1885. Preliminary report on sea-coast swamps of the

Eastern Llnited States. US' Geotogieat Survey 6tti Annuat

Report,

1886, pp. 353-398.

Wood, M.E., Kelley, J.T., and Belknap, D.F., 1989. Pattern of

sediment accumulation in the tidal marshes of Maine. Estuaries,

12:

237-246.

Cross-references

Barrier Islands

Deltas and Estuaries

Sediment Transport by Tides

Tidal Flats

Tidal Inlets and Deltas

SANDS, GRAVELS, AND THEIR LITHIFIED

EQUIVALENTS

Introduction

Sand is defined petrographically as detrital particles between'

1/16th

and 2 mm in diameter. Geologically, sand and its

lithified equivalent, sandstone, are defined as deposits consist-

ing of 75 percent or more of sand particles, the remainder

typically being silt or mud. Gravel is the general term applied

to detrital particles larger than 2 mm, with such terms as

pebbles, cobbles and boulders defined by specific size limits

(see below). A lithified gravel is termed a breccia if the gravel

fragments are angular, and conglomerate if they have been

rounded by attrition. Very few sandstones and conglomerates

consist entirely of sand- or gravel-sized particles, respectively.

Most conglomerates include a matrix of sand and finer

particles, and many sandstones are, to a greater or lesser

degree, muddy, silty, or conglomeratic. The third component

in many sandstones and conglomerates comprises one or more

cements of silica, calcium carbonate or other, less common

minerals. In most sandstones and conglomerates there are

remaining pore spaces (up to 40 percent but typically <25

percent by volume) that are filled with pore fiuids.

Sandstones and conglomerates typically preserve consider-

able internal evidence of their origins. The mineralogical

composition of the detrital particles reflects their lithologic

source, and may be studied to yield evidence of sedimentary

provenance and unroofing history of uplifted areas surround-

ing a sedimentary basin. Textures and structures of a deposit

provide evidence of the sedimentary processes involved in its

transport and deposition.

Sands and gravels constitute about 25 percent of sedimen-

tary rocks, by volume. They have economic importance as

hosts for about one third of the world's conventional oil and

gas and most of the heavy oil, plus several important economic

minerals mined for such commodities as copper and uranium.

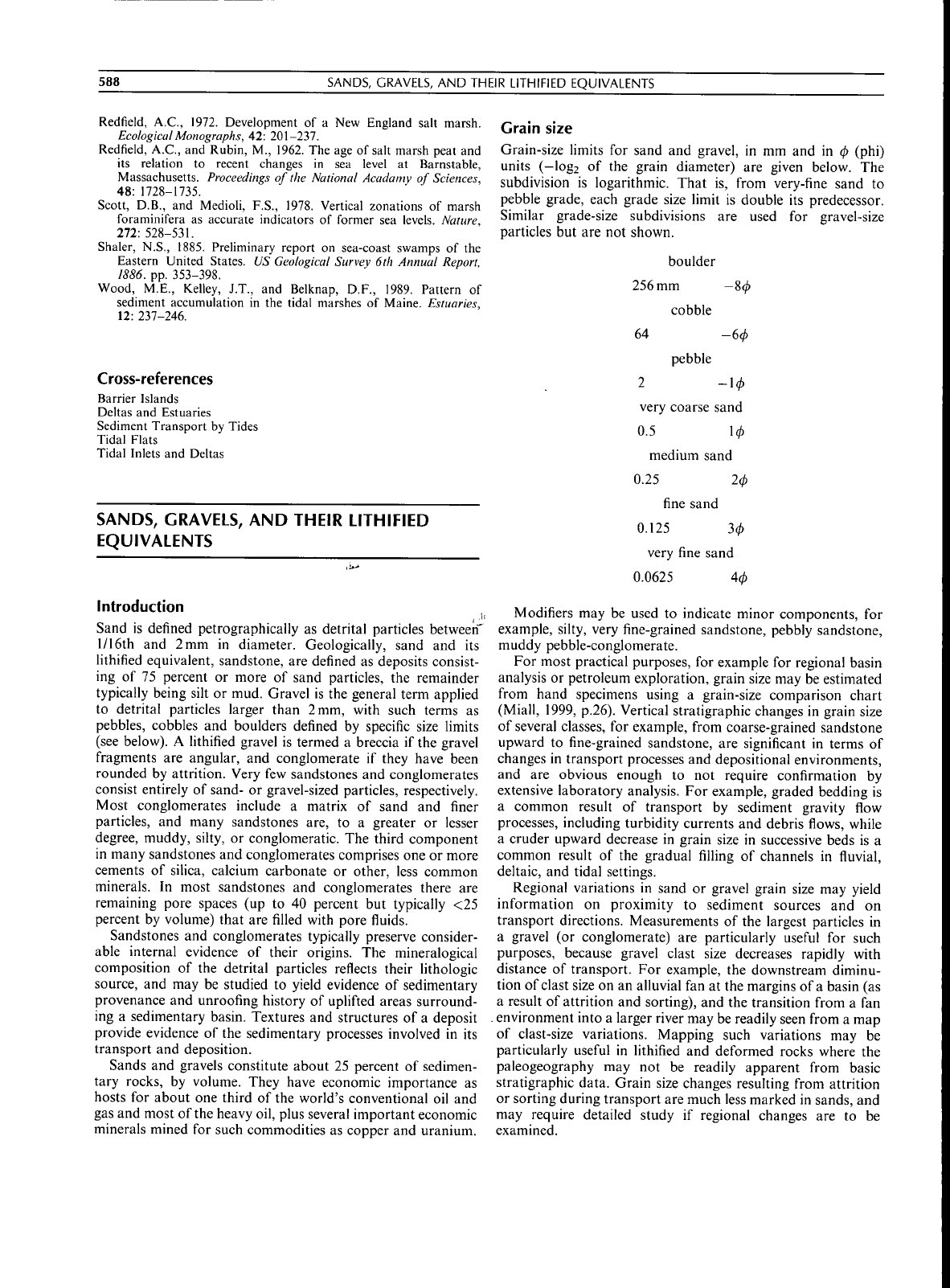

Grain size

Grain-size limits for sand and gravel, in mm and in

cj)

(phi)

units (—Iog2 of the grain diameter) are given below. The

subdivision is logarithmic. That is, from very-fine sand to

pebble grade, each grade size limit is double its predecessor.

Similar grade-size subdivisions are used for gravel-size

particles but are not shown.

boulder

256 mm -8(^

cobble

64 -6(1)

pebble

2 -1(^

very coarse sand

0.5 10

medium sand

0.25 24>

fine sand

0.125 34)

very fine sand

0.0625 4(1)

Modifiers may be used to indicate minor components, for

example, silty, very fine-grained sandstone, pebbly sandstone,

muddy pebble-conglomerate.

For most practical purposes, for example for regional basin

analysis or petroleum exploration, grain size may

b^e

estimated

from hand specimens using a grain-size comparison chart

(Miall, 1999, p.26). Vertical stratigraphic changes in grain size

of several classes, for example, from coarse-grained sandstone

upward to fine-grained sandstone, are significant in terms of

changes in transport processes and depositional environments,

and are obvious enough to not require confirmation by

extensive laboratory analysis. For example, graded bedding is

a common result of transport by sediment gravity flow

processes, including turbidity currents and debris fiows, while

a cruder upward decrease in grain size in successive beds is a

common result of the gradual filling of channels in fiuvial,

deltaic, and tidal settings.

Regional variations in sand or gravel grain size may yield

information on proximity to sediment sources and on

transport directions. Measurements of the largest particles in

a gravel (or conglomerate) are particularly useful for such

purposes, because gravel clast size decreases rapidly with

distance of transport. For example, the downstream diminu-

tion of clast size on an alluvial fan at the margins of a basin (as

a result of attrition and sorting), and the transition from a fan

. environment into a larger river may be readily seen from a map

of clast-size variations. Mapping such variations may be

particularly useful in lithified and deformed rocks where the

paleogeography may not be readily apparent from basic

stratigraphic data. Grain size changes resulting from attrition

or sorting during transport are much less marked in sands, and

may require detailed study if regional changes are to be

examined.

SANDS,

GRAVELS, AND THEIR LITHIFIED EQUIVALENTS 589

For more detailed work, laboratory procedures and

statistical data analysis methods are available. Use of these

methods has declined in recent years because they do not yield

additional information that is signilicant in most basin analysis

applications. However, studies of sediment transport and

bedform generation may require more precise and detailed

informalioit.

The grain size of loose sand may be meastired b\ the use of

sieves, settling tubes or electronic grain counting methods.

Lithilied sandstones may be analyzed in thin section, using a

moveabic stage to count a set number of grains (typically

several hundred). When logarithinic grain-size classes are used,

as in the table above, size distributions approximate that of the

normal (Gaussian) curve. Cumulative distribtitions, plotted on

a probability ordinale. approximate a straight line. The

steepness of the line (the narrowness of the peak about the

mean in a histogram) indicates the degree ol'"sorting'" of the

sand. Wind transport and wave sorting tend to generate well-

sorted sands, that is. sand with the greater bulk of the sand

concentrated over a limited size range, while fluvial transport

generates more poorly sorted sands. Many attempts have been

made to tisc various statistical measures of the grain-size

distribtttion to identify sediment transport processes, in order

to facilitate sedimentological work on very small samples, such

as drill cuttings. However, none of these methods is very

reliable, especially in lithified sediments, for a variety of

reasons. For example, grain-size distribution may be affected

by the size distribution of grains in the source rock, and may

be modified by diagenesis. Facies analysis methods are quicker

to apply and tnore reliable.

Grain shape

Shape may be defined in terms of three different parameters,

roundness, sphericity, and form. Roundness may be measured

following a detailed laboratory procedure, but is more

commonly estimated by comparison with sets of images of

known roundness. These show variations from very angular,

ihrough angular, sub-angular, sub-rounded, rotinded to well

rounded. Fragments are typically angular immediately follow-

ing breakage from a parent rock, and acquire roundness

through attrition during transportation. High degrees of

roundness usually are displayed only by particles that have

undergone intense wind abrasion, or are multicycle grains.

Sphericity may be defined as the ratio between the diameter

o\'

the sphere with the same volume as the particle, and the

diameler of the sphere circumscribed around the grain. A

more significant measure in terms of its hydraulic significance

is the "maximum projection sphericity", which depends on the

maximtun projection area, and is a better indicator of the fluid

resistance of the particle.

Detrital particles may be characterized as three-dimensional

ellipsoids with three measurable axes, a short axis, an

intennediate axis, and a long axis. Form is defined by the

use of two shape indices, the ratio of the intermediate to long

axis and the raiio of the short to intermediate axis. The

relationships between these two indiees define four form

classes: oblate (flattened sphere), bladed, prolate (rod-shaped)

and equant (round disk).

Studies of these three parameters have some limited

usefulness in investigations of sediment transport. Roundness

and sphericity increase with distance of transport, while form

affects efficiency o\' transport. Rod-shaped particles are more

easily transported in rivers; disks arc more common on wave-

formed beaches.

Grain orientation

Traction-current transport tends to align sand and gravel

grains such that elongate (rod-shaped) particles eommonly

aligti themselves cither parallel or perpetidicular to the

direction of movement. Flat, disk-shaped clasts tend to assume

a position on the bed with their maximum projection plane

dipping toward the direction of flow upstream in fluvial

environments, facing the sea in wave-formed beaches. This is

referred to as an imbricated fabric. Particles transported by

sediment gravity flow may also assume preferred orientations.

In debris (lows, clasts tnay be rotated by internal shear

immediately prior to the cessation of (lou, with imbricated, flat

(bedding-planc-parallel) or vertical orientations common.

Observation and measurement of these fabries may provide

useful information on paleoflow directions (Martini. 1971;

Schaefer and Teysen. 1987).

Composition

Sand and gravel represent the detrital products of weathering.

Most detrital particles are generated by mechanical weath-

ering, with subsequent fragmentation and rounding of grains

laking place by attrition during downslope movement and

during movement by wind and water. Chemical weathering

typically removes much of the source materiais in solution, but

tnay leave sand- and gravel-sized particles as a residue.

rhe composition of sand and gravel deposits reflects that of

the source materials, as modified by weathering and transpor-

tation (Blatt. 1992). Some types of detrital partiele are mueh

more resistant to weathering and erosion than others. Quartz,

an abundant mineral in igneous and metamorphic sources, is

highly resistant to mechanical and chemical weathering

processes, and is by far the most common detrital sand

particle. Minerals such as zircon, rutile, tourmaline and garnet,

which occur as accessories in igneous and metamorphic

sources, are also resistant and cotistitute minor components

of many sandstones. Grains of this resistant group may be

recycled through more than one episode of sandstone

formation and erosion, preserving evidenee of their lengthy

history as detrital particles in the form of well-rounded shapes,

and remnants of earlier grain outlines preserved beneath

fragments of cement.

After quartz, the next most common detrital particles are

feldspars, although ihese tend to weather readily. After this

come a wide range of rock fragments. Most types of igneous,

metamorphic and sedimentary rocks oeeur as fragments in

sand and gravel deposits. The smaller, sand-sized particles

tnay consist of single mineral erystals of the source rock, such

as rounded fragments of quartz or feldspar, or more or less

homogeneous pieces of fine-grained roeks such as shale or

slate.

Larger fragments, including many gravel particles, may

consist of recognizable roek types, such as rounded pieces of

an earlier sandstone, or a cobble of a eoarse-grained

plutonic rock.

Sands and gravels derived by erosion of older rocks, as

deseribed in the previous paragraphs, are classified, together

with mudroeks and silts, as siliciclaslic sediments, indicating

the predominance of silica-rich detrital particles in their

eomposition.

590

SANnS,

GRAVELS, AND THCIR LITHIFIED EQUIVALENTS

By contrast, in temperate to tropical marine settings, sands

composed entirely of calcium carbonate may accumulate in

shelf and shoreline environments from the fragments of

carbonate-secreting organisms such as invertebrate shells and

corals. The seawater in such places is commonly saturated with

the caleium and carbonate ions, and lime precipitation is

common. A particularly distinctive carbonate sand is one

composed of ooliths. which are particles consisting of

concentric laminae oflimc crystallized around a small nucleus.

such as a tiny shell fragment or a wind-blown quartz particle.

In contrast to siliciclastic sediments, carbonate sands are rarely

transported far. typically being confined to the shoreline or

shelf environment in which they are ibrmed.

In rare instancx's sands may he composed of evaporite

particles. Evaporite deposits, such as halite and gypsum, may

form by evaporation of water bodies in hot. enclosed basins.

Erosion and resedimentation of this material may take place

during flash flood events, during which evaporite bodies

may be fragmented, and the clasts redistributed as a form

of sand.

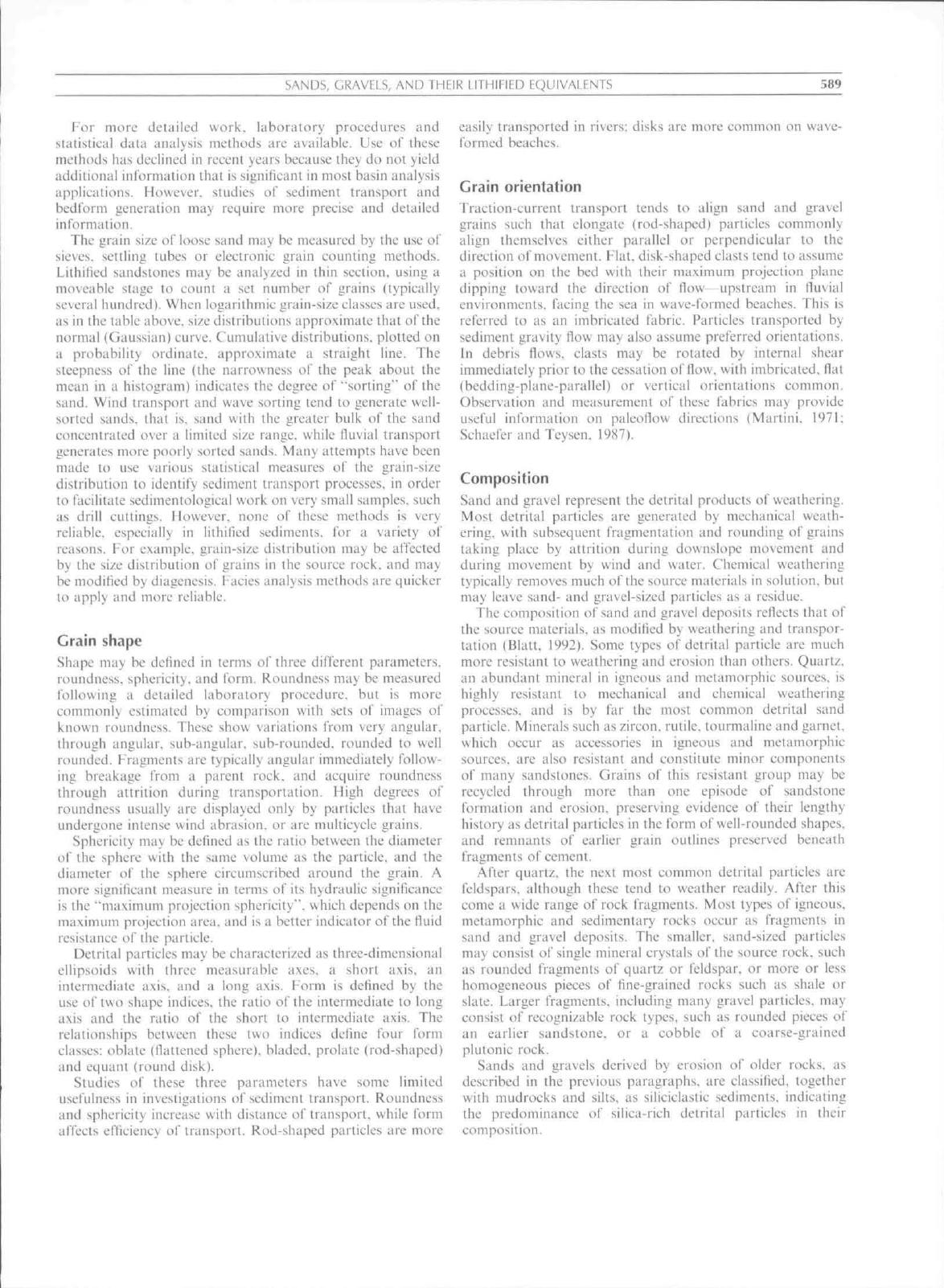

Siliciclastic sandstones may be classified according to their

detrital composition. Many different classification schemes

have been devised. That shown in Figure SI is one of the more

popular, ln most sandstones, each detrital particle is composed

ofa single mineral species, such as a crystal or crystal cluster of

quartz, feldspar, caleium carbonate, etc. Arenites are distin-

guished from wackes by the proportion of detrital matrix

(grains <30 mierons in diameter). Arenites are defined as

sandstones containing less than 15 percent matrix, wackes as

those with 15 75 percent matrix, while rocks consisting of

more than 75 percent fine-grained particles are termed

mudrocks. Particles larger than 30 microns are grouped into

three categories that deline the corners of the triangular

classification. Sandstones are classified according to the

proportions of the various detrital partieles, summed to 100

pereent. Determinations of these proportions are typically

carried out by thin-section analysis using a movable stage.

Except in cases of unusually pure (monomineralic) sands,

counts of 300 400 grains are typically required to obtain

reliable (stable) compositional data.

Sand-sized quartz grains, consisting of a few intergrown

crystals of siliea, are derived from eoarse-grained granitic

igneous or metamorphic rocks. Sand-sized quartz grains

eonsisting of numerous small intergrown crystals may have

been derived from finer grained igneous or metamorphic

sources. A metamorphic origin is commonly revealed by a

"strained" erystal fabric individual crystals go into extinc-

tion under eross polarizers under lightly different positions

as the microscope stage is rotated, indicating slight distortions

of the crystals lattice. Silica grains of sedimentary origin may

also be present in the form of chert, which oeeurs as mosaics of

tiny interlocking grains, eommonly preserving replaced fossil

structures. Chert is normally eounted as a roek fragment for

the purpose of sandstone classification. Feldspathic sandstones

typically are derived from granites or granite gneisses. Lithic

sandstones may eome from a variety of sources, and are

quartz

arenite

sub-feldspathic

arenite

Figure SI Cbssificalion of sand jnd sandstone according lo composition. Sand is classified according to the rcldlive proportion of three

major classes of delrilal tomposilion. St'paralion of the three triangles is on ihe basis of ihe proportion of detrital malrix (modified

from Dott,

19641.

SANDS.

GRAVELS, AND THFIR LITHIEIED EQUIVALENTS

591

characterized by the predominance of recognizable roek

fragments. For example, modern "blaek-sand beaches"" in

Hawaii are composed of basalt fVagments derived from wave

erosion of fresh lava flows. Green beaches are composed

largely of olivine grains, accumulated by selective wave sorting

from the same voleanie sourees. Sands with sueh unusual

compositions are rare in the rock reeord because of the

chemical and mechanical instability of basalt grains under

normal weathering conditions. Quart/ arenites typically

represent recycled deposits from which other minerals have

been removed by mechanical or ehemieal destruetion. It is

likely that many pure quartz arenites contain grains that were

originally derived from a primary igneous or metamorphic

souree lumdreds of millions of years before ending up in the

rock in which they are found today. Some roek fragments may

o\idi7e or otherwise decompose in plaee. and may be

represented by clots of elay. that can be mistaken for detrital

matrix. This has been ealled "pseudomatrix.""

Figure SI includes two old petrographic terms that are not

recommended, but are still in use. "Arkose"" is an old term for

feldspathic arenites, and "greywaeke"' is an old term for lithie

wackes.

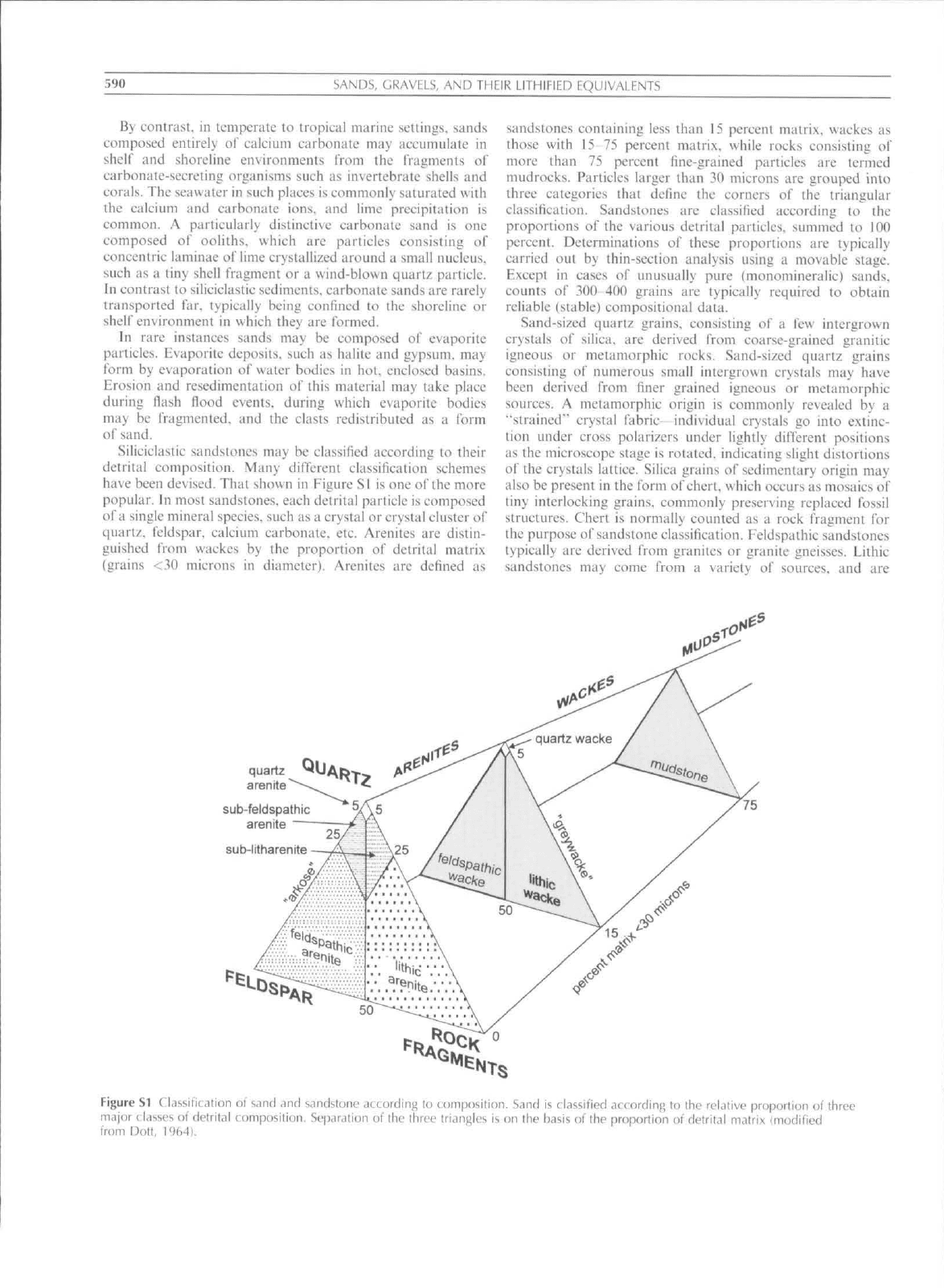

Variations in detrital composition areally aeross a basin or

vertically, through a stratigraphic section, can yield mueh

useful information about the paleogeography of a basin and

the uplift history of surrounding source terranes. espeeially if

such studies are carried out in concert with analysis of grain-

size variations, as noted in the previous section. Given the

varying resistanee of detrital speeies to destruetion by the

proeesses of transportation, areal variations in composition

may yield inf\irmation about the location of speeifie sediment

sources, and distances of sediment transport away from them.

Certain components, particularly distinctive rock fragments,

may be capable of being traced back to specific source rocks

exposed in a source terrane. Direction and distance of

transport may be indicated qualitatively by a decrease in the

proportion and grain size of sueh distinetive components, with

a concomitant increase in the proportion of stable grains,

particularly quartz. For example, a localized carbonate reef

deposit or a small igneous intrusion may yield floods of

cobbles or boulders ofa distinctive composition to an alluvial

fan deposit banked against the adjacent basin margin, with

the size and abundanee of such grains decreasing toward the

basin center as the partieles are destroyed by attrition and

4 2

Figure S2 Three successive cross-sections illustrating the erosional unroofing of an uplifted faull block. Detritus from successive

slratigraphic units 1, 2, .3, and 4 appear in inverse order in the sand delritus transported to the basin at right, as shown in the pie

diagrams (after Graham et ai,

14861.

592 SAPROPCL

Quartz

Conlinenlal (crartonic)

sources

Recycled orogen sources

including subdudion zone rocks,

detorrred oceanic rocks,

orogenic metasediments)

Feldspar

Magmatic arc sources

(indudtng volcanic detnlua)

Lithic

fragments

Figure S3 An example {)f a detrital sand composition plot showing

the fields representing derivation from three broad classes uf

plate-tectonic setting (after Dickinson and Suczek, 1979).

weathering and are diluled by intermingling with other species

from other sediment sources.

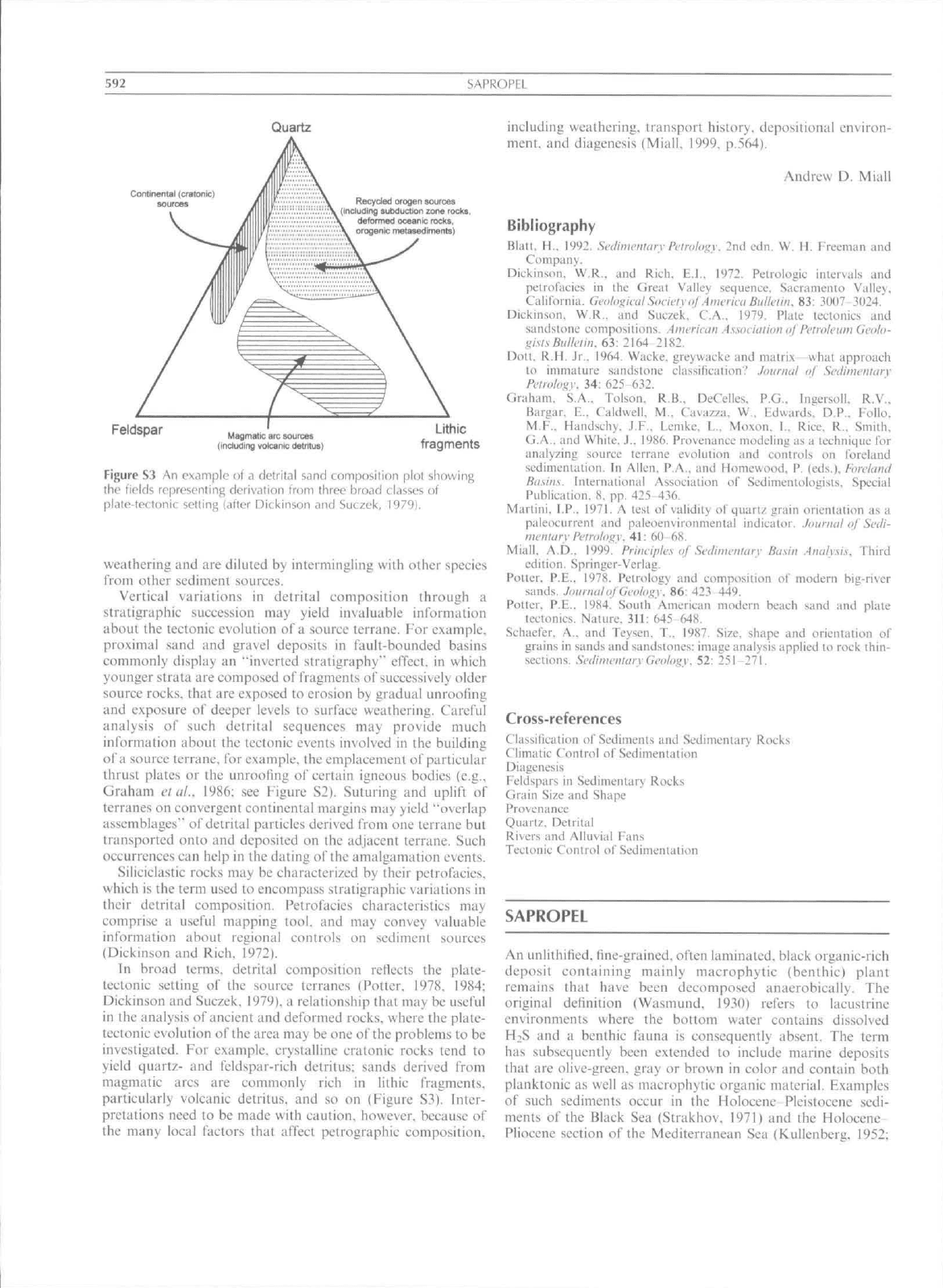

Vertical variations in detrital composition through a

stratigraphic succession may yield invaluable information

aboul the tectonic evolution of a source tcrrane. For example,

proximal sand and gravel deposits in fault-hounded basins

commonly display an ""inverted stratigraphy"' elTcct, in which

younger strata are composed of fragments of successively older

source rocks, thai are exposed to erosion by gradual unroofing

and exposure of deeper levels to surface weathering. Careful

analysis of sueh detrital sequences may provide much

information about the tectonic events involved in the building

of

a

source terrane, for example, the emplacement of particular

thrust plates or the unroofing ol'certain igneous bodies (e.g..

Graham el aL. 1986: see Figure S2). Suturing and uplift of

terranes on convergent continentai margins may yield "overlap

assemblages" of detrital partieles derived from one terrane but

transported onto and deposited on the adjacent terrane. Sueh

occurrences can help in the dating of the amalgamation events.

Silieielastic rocks may be characterized by their petrofacies,

whieh is the term used to encompass stratigraphic variations in

their detrital composition, Petrofacics characteristics may

eomprise a useful mapping tool, and may convey valuable

iriformalion about regional controls on sediment sources

(Dickinson and Rich. 1972),

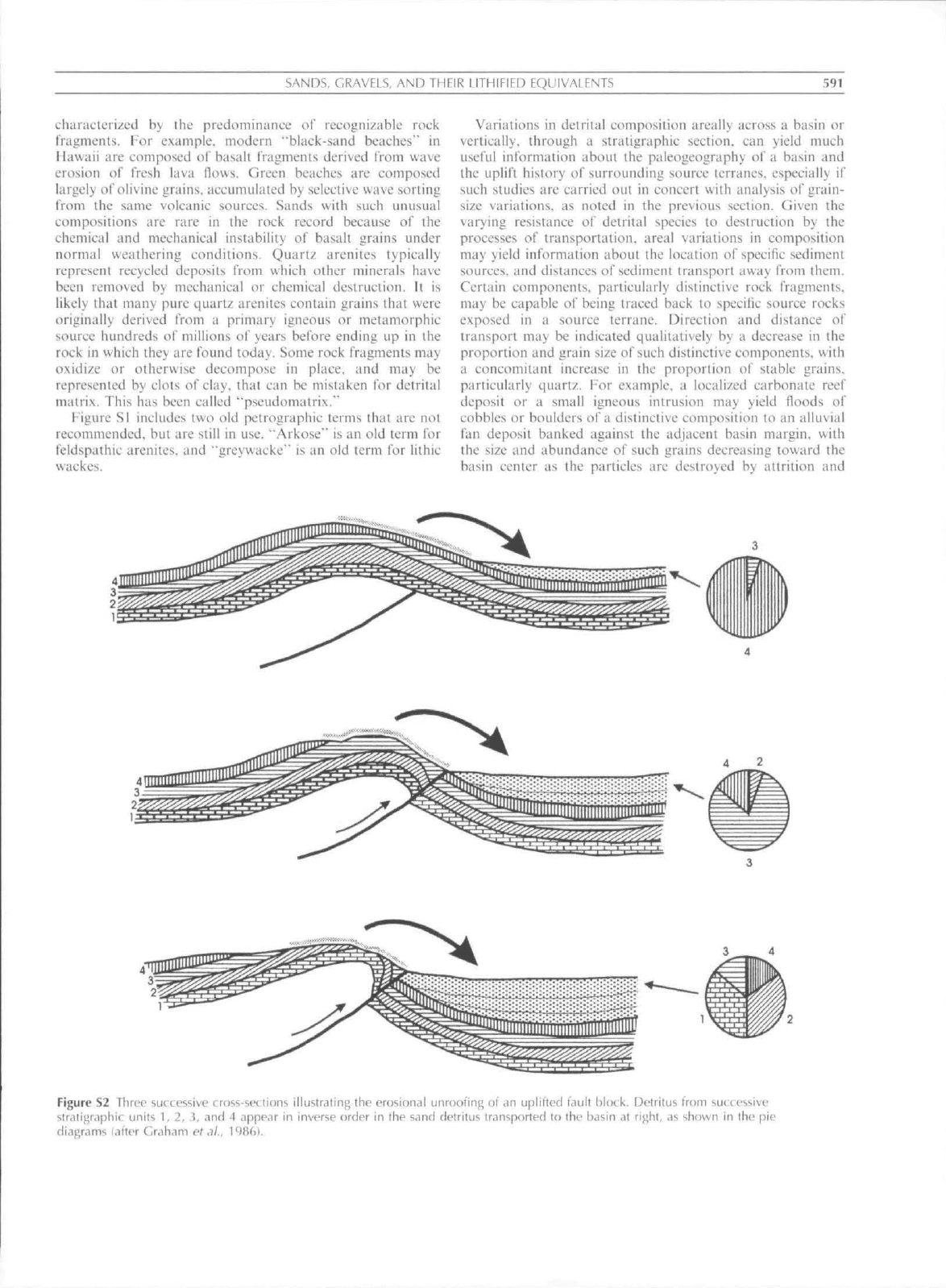

In broad terms, detrital composition reflects the plate-

tectonic setting of the souree terranes (Potter. 1978. 1984:

Dickinson and Suczek. 1979). a relationship (hat may be useful

in the analysis of ancient and deformed rocks, where the plate-

tectonic evolution ofthe area may be one of the problems to be

investigated. For example, crystalline cralonic rocks tend to

yield quartz- and feldspar-rich detritus: sands derived from

magmatic ares are eommonly rich in lithic fragments,

partieularly volcanic detritus, and so on (Figure S3). Inter-

pretations need to be made with caution,, however, because of

the many local faetors that affect petrographic eomposition.

including weathering, transport history, depositional environ-

ment, and diagenesis (Miall. 1999, p.564).

Andrew D, Miall

Bibliography

BlaU, H,. 1992, Scdmu'niary I'vimhgy. 2nd edn, W, H, Freeman and

Company.

Dickinson. W.R,, and Rich, E.I,, 1972. Petrologic iniervals and

peUofacies in the Great Valley sequence. Sacramento Valley.

California, (k'ologimlSovk-iyof .Ameriai Bullclw. 83: 3007 3024,'

Dickinson. W.R,. and Suczek. CA.. 1979, Plate tectonics and

sandstone Lompositiuns, Aim-rUan

A.s,wcliilitiii

af

Petroleum

Geolo-

^i.MsB!illc!li!.6i: 2164 2182,

Dott. R.H, Jr,. 1964, Wacke. greywacke and matri,\—what approach

to immature sandstone classilicalionV Jounuil nf Scdimciilciry

Pciroh^v. 34: 625-632,

Grahatn. S,A,. Tolson. R.B,. DeCdIes. P.O.. Ingcrsoll. R.V,,

Bargar. E,. Caldwell, M,. Cavazza. W,. Edwards. D,P,. Folio.

M,F,.

Haiidscliy, J,F,, Lemke. L.. Moxon. 1,, Rice. R,. Sniiih.

G.A.. and White. J,. 1986, Provenance modeling as a technique for

analyzing source terrane evolution and controls on foreland

sedimentation. In Allen, P,A,, and Homewood. P, (eds,). thrcland

Basins. International Association of Sedimenlologisls. Special

Publicaiion. 8. pp. 425 436.

Mariini. I.P,. 1971, A tesi of validity ol'quart? grain orientation as a

paleocurrent and paleocnvironmcnta! indicator, .launnil oJ Scdi-

nwiUury Pelnihgy. 41: 60 68.

Mial!. A,D,. 1999, Principles of

SediDieitUivy

Busiii

.Amdy.^is.

Third

edition. Springer-Verlag,

Potter. P,E,. 1978, Petrology and composition of modern big-river

sands,

.loiirmilof(Jcolof;y'S6: 423 449,

Potter. P.E,, I9S4. South American modern beach sand and plate

tectonics. Nature. 311: 645 MH,

Schaefer. A,, and Teyscn. T.. 1987. Size, shape and orientation of

grains in sands and sandstones: image analysis applied to rock thin-

sections, Sedimeniiiry Geology. 52:

251-271,

Cross-references

Classification of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Climatic Control of Sedimentation

Diagenesis

Feldspars in Sedimentary Rocks

Grain Size and Shape

Provenance

Quart/. Detrital

Rivers and Alkiviai F-aiis

Tectonic Control of Sedimentation

SAPROPEL

An unlithilied, fine-grained, often laminated, blaek organic-rich

deposit containing mainly macrophytic (benthie) plant

retrains that have been decomposed anaerobieally. The

original definition (Wasmund. 1930) refers to lacustrine

environments where the bottom water contains dissolved

H^S and a benthic fauna is consequently absent. The term

has subsequently been extended to include marine deposits

that are olive-green, gray or brown in color and contain both

planktonic as well as macrophytic organic material. Exatnples

of such sediments occur in the Holocene Pleistocene sedi-

ments ofthe Blaek Sea (Strakhov, 1971) and the Holocene

Plioeene section ofthe Mediterranean Sea (Kullenberg, 1952:

SAf'KOPEL

593

Kidd

('/ al..

197S).

iiK'ludini;

poorly-iilhilicd rocks

tnil-

cropping

in the

northern borderlands

of ihe

Mediterranean

(van

O^etai.

19^4).

Composition

According to the definition of Kidd etal. (1978), sapropels

contain more than 2 wt. percent organic carbon and are at least

I cm thick: sapropelic sediments are similarly defined but

contain 0.5-2 wi. percent earbon. Organic carbon contents in

Black Sea and Mediterranean sapropels can range up to I6wt.

percent and 30wt. percent, respectively. The sapropels of

the Black Sea contain both terrestrial and marine organic

material (Wakehani ctai.. 1991). whereas in ihe Mediterranean

e.\amplcs ihe organic fraction is overwhelmingly marine

(ten Haven et at.. 1987). Sapropels also contain variable

amounts of biogenous carbonate and silica together with tine-

grained aluminosilicates. In eommon with other organic-rich

marine sediments, sapropels have high concentrations of

pyrite and a suite of minor and trace metals that often include

Ba. Cu, Mo, Ni, U, V. and Zn (Calvert, 1983).

Black Sea sapropels

A black, very line-grained sapropel has accumulated in the

deep basin of the Black Sea over the last 7,500 years (Degens

and Ross, 1972; Jones and Gagnon, 1994). The lower part of

this deposit is especially organic rich (up to 20 wt. percent

organic C). whereas the modern section contains 5wt. percent

organic C. A benthic fauna is absent in this permanently

anoxic basin. The black coloration is caused by the presence of

iron monosullide. which readily oxidizes when it is exposed to

the atmosphere, causing the color of ihe sediment to fade to

dark grey (Berner, 1974). Sapropel formalicm began when

saline Mediterranean waters entered the Blaek Sea basin via

the Bosphorus Strait as a result of post-glacial sea level rise.

This changed the Pleistocene Black Lake into the modern

brackish (salinity IT), anoxic basin (Middelburg ctai... 1991).

The accumulation rate of organic material increased markedly

at this transition, and the accumulation rate of coccolith calcite

increased about 2.700 years ago (Jones and Gagnon. 1994).

thereby diluting the organic flux and initiating the (brmation

of the modern laminated calcareous marls (Calverl et al..

1991).

Sapropels are aiso known to occur in the Pleistocene

section of the deep Black Sea (Calvert, 1983).

Mediterranean sapropels

Multiple horizons of discrete centimeter- to decimeter-thick

olive green to brown sapropels are found intercalated in the

normal nanofossil marls of the Mediterranean Sea. They were

discovered in the eastern basin during the Swedish Deep-Sea

Expedition in 1947 (Kullenberg, 1952) contirming a prediction

of Bradley (1938) thai laminated, organic-rich glacial sedi-

ments should have formed when lowered sea level caused

stagnation of the partially restricted eastern basin. Drilling in

the Mediterranean over the last 25 years has extended the

occurrence of these deposits throughout the eastern and

western basins baek to the Early Plioeene (Murat. 1999; Emeis

etal.. 2000). The sapropels (>2 percent Corgunic) ^re up to

70em thick and contain up to 30wt. pereent organic carbon.

They may be faintly laminated, and either contain an

impoverished benthie mierofauna or are barren (Jorissen.

1999).

They contain relatively high concentrations of pyrite

but only trace amounts of iron monosultide (Passier

etaf.,

1997):

consequently their eolor does not change on exposure to

the atmosphere. They are restricted to periods of climatic

amelioration in the Mediterranean when the monsoon-driven

freshwater balance changed drastically, and bottom water

oxygen levels decreased leading to dysoxic or anoxic condi-

tions on the seafloor.

Formation of sapropels

Sapropets are considered to form by one or a combination of

the following processes: (I) increased preservation of organic

matter in the bottom sediments: (2) high rales of supply of

organic matter to the seiifloor: (3) decreased dilution of the

organic fraction by other sediment comptinents. The preser\a-

tion hypothesis focuses on the lower rate of decomposition of

deposited organic matter under anoxic or dysoxic conditions

because of the lower energy yield of mierobially-driven

degradation of organic matter using oxidants other than

oxygen (nitrate, Mn and Ee oxides and sulfate). Thus, the

factors that promote the establishment of bottom water anoxia

(or dysoxia) regardless of organic matter supply ultimaiely

drive sapropel formation (Ryan and Cita, 1977). An alter-

native view centers on situations where the supply of organic

matter relative to that of other sediment components increases,

either by higher planktonic production in the overlying waters

or by higher rates of supply of terrestrial organic matter

(Calvert, 1987). Under these circumstances, lower bottom

water oxygen levels are due to the eonsumption of dissolved

oxygen by the degradation of settling organic matter and not

necessarily by basin restriction, sea level change, etc.; anoxia is

a consequence of higher produetion. Decreased dilution of the

organic fraction of a sediment would amplify the effects of

anoxia or organic supply emphasized in the other two

mechanisms of sapropel formation.

The balance of evidence suggests that the Black Sea sapropel

began to form when anoxic eonditions were established in

the basin following the influx of saline waters from the

Mediterranean when sea level reached the Bosphorus sill

(Degens and Ross, 1974). Whether the anoxic conditions

promoted ihe preferential preservation of organic matter or

production in the basin increased markedly following the

transformation of the basin from the lake to the modern

marine phase are still matters of dispute. Nevertheless, the

bulk accumulation rate of organie matter in the modern faeies

is similar to rates determined in oxygenated settings at similar

water depths and sedimentation rates in the open ocean

(Calvert etal., 1991). In the Mediterranean, detailed studies of

the geochemistry and micropalaontology of the sapropels and

associated sediments (Wehausen and Brumsack. 1999; Calvert

and Kontugne. 2001: Mercone etal.. 2001) show that bottom

waters ranged between full anoxia and dysoxia, reflected in the

high redox-sensitive trace metal (Cu. Mo, Ni, U, V) contents,

and that planktonic production was significantly higher (high

Ba) during their formation. They formed during periods of

higher fresh water input to the eastern basin, driven by more

intense monsoonal rainfall over northern Africa and the

northern Mediterranean borderlands at the precessional

frequeney (Rossignol-Strick ctai.. 1982; Rohling, 1994), which

probably led to increased stratification and more restricted

vertical circulation. The evidence for higher production

requires that nutrient supply was higher, and this has been

594

SCOUR, SCOUR MARKS

ascribed to a reversal in circulation (Berger, 1976) such that an

estuarine circulation regime (surface water outflow and

subsurface water inflow) replaced the modern anti-estuarine

circulation (deep water outflow and surface water inflow).

Summary

Sapropel is an organic-rich sediment or sedimentary rock that

may be finely laminated; it lacks, or has a depauperate, benthic

fauna and high concentrations of redox-sensitive trace metals,

Holocene and Pleistocene examples of this facies evidently

formed by high organic matter supply and/or preferential

preservation of deposited organic matter under anoxic/dysoxic

bottom water or sediment conditions in partially restricted

environments,

Stephen E, Calvert

Bibliography

Berger,

W,H,, 1976,

Biogenous deep-sea sediments: production,

peservation

and

interpretation.

In

Riley,

J,P,, and

Chester,

R,

(eds,).

Chemical Oceanography. Academic Press,

pp,

265-388,

Berner,

R,A,, 1974,

Iron sulfides

in

Pleistocene deep Black

Sea

sediments

and

their paleo-oceanographic significance.

In

Degens,

E.T., and

Ross,

D,A,

(eds.).

The

Black Sea—Geology,

Chemistry

and

Biology. American Association

of

Petroleum

Geologists Memoir,

pp,

524-531,

Bradley,

W,H,, 1938,

Mediterranean sediments

and

Pleistocene

sea

levels.

Science, 88: 376-379,

Calvert,

S,E,, 1983,

Geochemistry

of

Pleistocene sapropels

and

associated sediments from

the

eastern Mediterranean, Oceanologi-

caActa,

6:

255-267,

Calvert,

S,E,,

1987, Oceanographic controls

on the

accumulation

of

organic matter

in

marine sediments.

In

Brooks,

J,, and

Fleet,

A,J.

(eds,).

Marine Petroleum Source Rocks. Geological Society

of

London,

pp,

137-151,

Calvert,

S,E,, and

Fontugne,

M,R,,

2001,

On the

Late Pleistocene-

Holocene sapropel record

of

climatic and oceanographic variability

in

the

eastern Mediterranean, Paleoceanography, 16: 78-94.

Calvert,

S,E,,

Karlin,

R,E,,

Toolin,

L.J,,

Donahue,

D,J,,

Southon,

J,R,,

and

Vogel, J,S,, 1991, Low organic carbon accumulation rates

in Black

Sea

sediments. Nature, 350: 692-694.

Degens, E.T.,

and

Ross, D,A,, 1972. Chronology ofthe Black Sea over

the last 25,000 years. Chemical

Geology,

10: 1-16.

Degens,

E.T., and

Ross,

D,A,, 1974,

Recent sediments

of the

Black

Sea,

In

Degens,

E,T,, and

Ross,

D.A,

(eds,).

The

Black

Sea-

Geology ChemistryanclBiology. American Association

of

Petroleum

Geologists Memoir 20,

pp,

183-199,

Emeis, K,-C,, Sakamoto,

T.,

Wehausen,

R,, and

Brumsack, H,-J.,

2000,

The

sapropel record

of the

eastern Mediterranean Sea—

results

of

Ocean Drilling Program

Leg 160,

Palaeogeography

Palaeoclimatology

Palaeoecology,

158: 371-395,

Jones,

G,A,, and

Gagnon,

A.R,,

i994. Radiocarbon chronology

of

Black

Sea

sediments. Deep-Sea Research, 41: 531-557,

Jorissen,

F,J., 1999,

Benthic foraminiferal successions across late

Quaternary Mediterranean sapropels. Marine Geologv,

153: 91-

101.

Jorissen,

F.J,,

Barmawidjaja,

D.M.,

Puskaric,

S,, and van der

Zwaan,

G.J,, 1992,

Vertical distribution

of

benthic foraminifera

in

the

northern Adriatic

Sea: the

relation with

the

organic flux.

Marine Micropaleontology, 19: 131-146,

Kidd,

R.B,,

Cita,

M,B., and

Ryan, W.B.F.,

1978.

Stratigraphy

of

eastern Mediterranean sapropel sequences recovered during

Leg

42A

and

their paleoenvironmental significance.

In Hsu, K.J., and

Montadert,

L.

(eds.). Initial Reports ofthe Deep-Sea Drilling Project.

LI.S.

Government Printing Office,

pp,

421-443.

Kullenberg,

B,,

1952,

On the

salinity ofthe water contained

in

marine

sediments. Gotehorgs Kungl. Vetenskaps. Vitt-Samhal. Handlingar,

6B:

3-37,

Mercone,

D.,

Thomson,

J,, and

Troelstra,

S.R.,

2001. High-resolution

geochemical

and

micropalaeontological profiling ofthe most recent

eastern Mediterranean sapropel. Marine

Geology,

177: 25-44.

Middelburg,

J,J,,

Calvert,

S,E,, and

Karlin,

R,E,,

1991. Organic-rich

transitional facies

in

silled basins: response

to

sea-level change.

Geology, 19: 679-682,

Murat,

A,, 1999,

Pliocene-Pleistocene occurrence

of

sapropels

in

the western Mediterranean

Sea and

their relation

to

eastern

Mediterranean sapropels.

In

Zahn,

R.,

Comas,

M.C, and

Klaus,

A. (eds.). Proceedings ofthe Ocean Drilling Program Scientific

Re-

sults. Volume 161,

pp,

519-528,

Passier,

H,E.,

Middleburg,

J,J., De

Lange,

J.J,, and

Bottcher,

M,E,,

1997,

Pyrite contents, microtextures,

and

sulfur isotopes

in

relation

to

the

formation

of

the youngest eastern Mediterranean sapropel.

Geology, 25: 519-522,

Rohling, E.L., 1994, Review and new aspects concerning the formation

of eastern Mediterranean sapropels. Marine

Geology,

122:

1-28.

Rossignol-Strick,

M,,

Nesteroff,

W,,

Olive,

P., and

Vergnaud-

Grazzini,

C, 1982,

After

the

deluge: Mediterranean stagnation

and sapropel formation. Nature, 295: 105-110.

Ryan, W,B,F,,

and

Cita, M.B., 1977, Ignorance concerning episodes

of

ocean-wide stagnation. Marine Geology, 23: 193-215.

Strakhov, N.M., 1971, Geochemical evolution ofthe Black

Sea in the

Holocene. Lithology and Mineral Resources,

3:

263-274,

ten Haven,

H,L,,

Baas,

M,, de

Leeuw,

J,W,,

Schenck,

P,A,, and

Brinkhuis,

H,,

1987, Late Quaternary Mediterranean sapropels,

II,

Organic geochemistry

and

palynology

of S]

sapropels

and

associated sediments. Chemical

Geology,

64:

149-167.

van

Os,

B.J.H., Lourens,

L,J,,

Hilgen,

F.J,, de

Lange,

G.J., and

Beaufort,

L., 1994. The

formation

of

Pliocene sapropels

and

carbonate cycles

in the

Mediterranean: diagenesis, dilution

and

productivity, Paleoceanography,

9:

601-617,

Wakeham,

S.G.,

Beier, J,A,,

and

Clifford, C.H,, 1991, Organic matter

sources

in the

Black

Sea as

inferred from hydrocarbon distribu-

tions.

In

Izdar,

E,, and

Murray,

J,W,

(eds,). Black Sea Oceanogra-

phy. Kluwer Academic Publishers,

pp,

319-341.

Wasmund,

E.,

1930. Bitumen, Sapropel,

und

Gyttja. Geologiska

Fore-

nigens Forhandlingar,

52:

315-350,

Wehausen,

R,, and

Brumsack, H,-J,,

1999,

Cyclic variations

in the

chemical composition

of

eastern Mediterranean Pliocene sedi-

ments:

a key for

understanding sapropel formation. Marine

Geology, 153: 161-176,

Cross-references

Black Shales

Oceanic Sediments

SCOUR, SCOUR MARKS

Scour is a general sedimentary process which brings about the

sustained lowering of a surface by the direct or indirect action

upon it of a current of water or air. The process normally acts

differentially, resulting in a range of distinctive forms, called

scour or erosional marks. Differential solution, as of limestone

surfaces or beds of halite or gypsum, gives rise to structures

resembling some kinds of scour mark, but the concept of scour

excludes this particular mechanism. Scour has been much

studied by engineers in connection with the stability of bridge

piers and the control of drifting snow along highways.

The mechanisms of scour (Allen, 1982a) are: (1) entrain-

ment; (2) stripping; and (3) corrasion, Entrainment affects

surfaces composed of sand or gravel, and sees particles

removed one by one as the result of the direet action of the

shear and pressure forces exerted by the moving fluid, to which

may be added impacts due to particles already in transport as