Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

RIPPLE,

RIPPLE MARK, RIPPLE STRUCTURE

565

'olymer

Class

la:

R

=

COjH, CHjOH,

0-Succlnyl,

CHj

Others

(?)

Class

Ib:

R

=

COjH, CHjOH,

CHj Others

(?)

No Succinic Acid

Class

Ic:

R-COjH. CHjOH,

CH3 Others

(?)

No Succinic Acid

Class

II

Polycadinene

Class

IV

Cedrane

sesquiterpenoid

Class

III

Polystyrene

Class V

., Abietane/Pimarane

*'^2"

Diterpenoids.

(Labdanoids nonnally

absent)

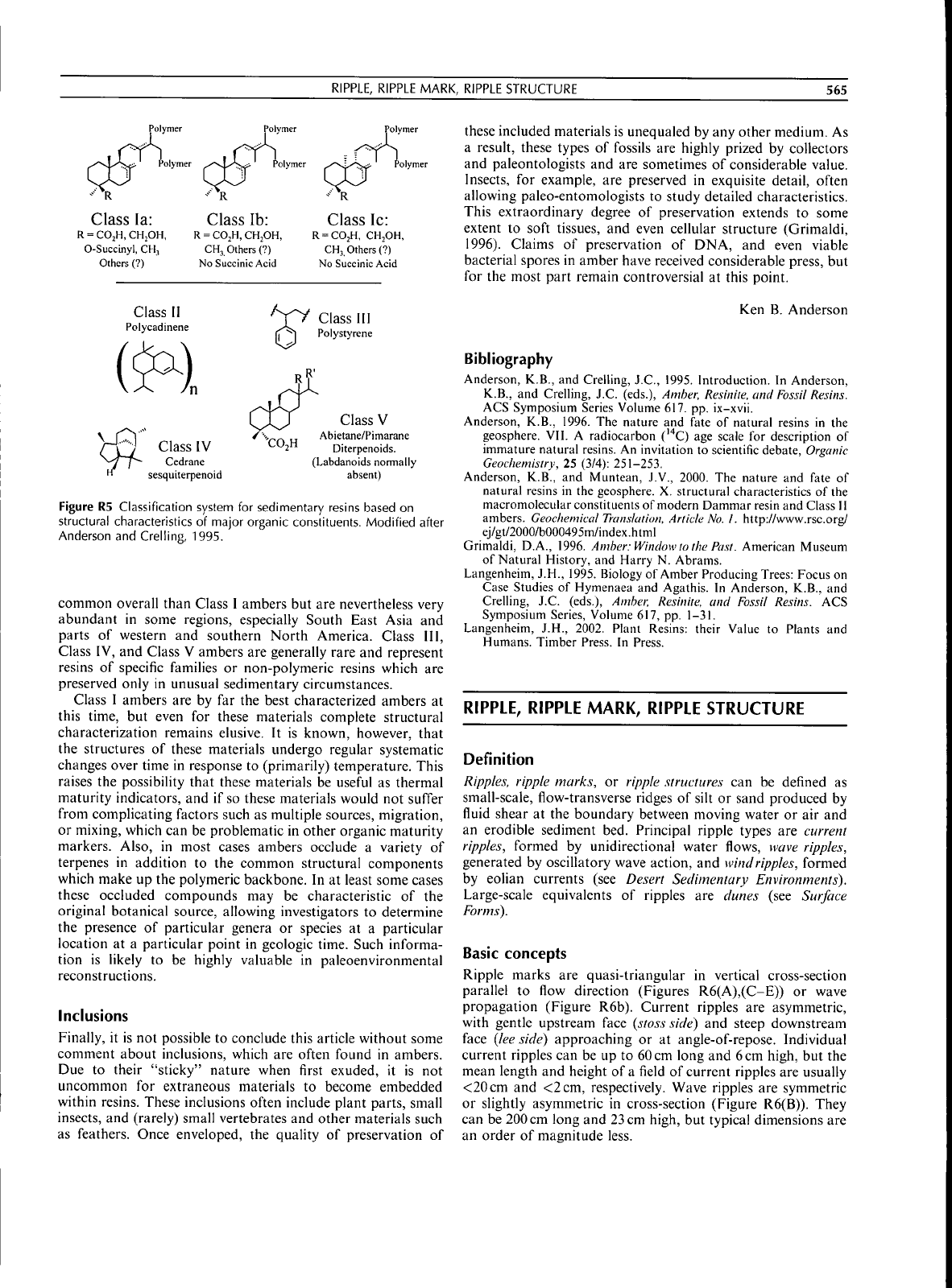

Figure

R5

Classification system

for

sedimentary resins based

on

structural characteristics

of

major organic constituents. Modified after

Anderson

and

Crelling,

1995.

common overall than Class

1

ambers

but are

nevertheless very

abundant

in

some regions, especially South East Asia

and

parts

of

western

and

southern North America. Class

III,

Class

IV, and

Class

V

ambers

are

generally rare

and

represent

resins

of

specific families

or

non-polymeric resins which

are

preserved only

in

unusual sedimentary circumstances.

Class

I

ambers

are by far the

best characterized ambers

at

this time,

but

even

for

these materials complete structural

characterization remains elusive.

It is

known, however, that

the structures

of

these materials undergo regular systematic

changes over time

in

response

to

(primarily) temperature. This

raises

the

possibility that these materials

be

useful

as

thermal

maturity indicators,

and if so

these materials would

not

suffer

from complicating factors such

as

multiple sources, migration,

or mixing, which

can be

problematic

in

other organic maturity

markers. Also,

in

most cases ambers occlude

a

variety

of

terpenes

in

addition

to the

common structural components

which make

up the

polymeric backbone.

In at

least some cases

these occluded compounds

may be

characteristic

of the

original botanical source, allowing investigators

to

determine

the presence

of

particular genera

or

species

at a

particular

location

at a

particular point

in

geologic time. Such informa-

tion

is

likely

to be

highly valuable

in

paleoenvironmental

reconstructions.

Inclusions

Finally,

it is not

possible

to

conclude this article without some

comment about inclusions, which

are

often found

in

ambers.

Due

to

their "sticky" nature when first exuded,

it is not

uncommon

for

extraneous materials

to

become embedded

within resins. These inclusions often include plant parts, small

insects,

and

(rarely) small vertebrates

and

other materials such

as feathers. Once enveloped,

the

quality

of

preservation

of

these included materials

is

unequaled

by any

other medium.

As

a result, these types

of

fossils

are

highly prized

by

collectors

and paleontologists

and are

sometimes

of

considerable value.

Insects,

for

example,

are

preserved

in

exquisite detail, often

allowing paleo-entomologists

to

study detailed characteristics.

This extraordinary degree

of

preservation extends

to

some

extent

to

soft tissues,

and

even cellular structure (Grimaldi,

1996).

Claims

of

preservation

of DNA, and

even viable

bacterial spores

in

amber have received considerable press,

but

for

the

most part remain controversial

at

this point.

Ken

B.

Anderson

Bibliography

Anderson, K.B.,

and

Crelling,

J.C,

1995. Introduction.

In

Anderson,

K.B.,

and

Crelling,

J.C.

(eds.). Amber, Resinite,

and

Eossil Resins.

ACS Symposium Series Volume 617.

pp.

ix-xvii.

Anderson,

K.B., 1996. The

nature

and

fate

of

natural resins

in the

geosphere.

VII. A

radiocarbon

('''C)

age

scale

for

description

of

immature natural resins.

An

invitation

to

scientific debate. Organic

Geochemistry,

25

(3/4): 251-253.

Andersoti,

K.B., and

Muntean,

J.V.,

2000.

The

nature

and

fate

of

natural resins

in the

geosphere.

X.

structural characteristics

of the

macromolecular constituents

of

modern Dammar resin

and

Class

II

ambers. Geochemical Translation. Article

No.

I.

http://www.rsc.org/

ej/gt/2000/b000495m/index.html

Grimaldi,

D.A., 1996.

Amber: Window to the Past. American Museum

of Natural History,

and

Harry

N.

Abrams.

Langenheim,

J.H.,

1995. Biology

of

Amber Producing Trees: Focus

on

Case Studies

of

Hymenaea

and

Agathis.

In

Anderson,

K.B., and

Crelling,

J.C.

(eds.). Amber, Resinite.

and

Eossil Resins.

ACS

Symposium Series, Volume 617,

pp. 1-31.

Langenheim,

J.H.,

2002. Plant Resins: their Value

to

Plants

and

Humans. Timber Press.

In

Press.

RIPPLE, RIPPLE MARK, RIPPLE STRUCTURE

Definition

Ripples, ripple marks,

or

ripple structures

can be

defined

as

small-scale, flow-transverse ridges

of

silt

or

sand produced

by

fluid shear

at the

boundary between moving water

or air and

an erodible sediment

bed.

Principal ripple types

are

current

ripples, formed

by

unidirectional water flows, wave ripples,

generated

by

oscillatory wave action,

and

wind ripples, formed

by eolian currents

(see

Desert Sedimentary Environments).

Large-scale equivalents

of

ripples

are

dunes

(see

Surface

Forms).

Basic concepts

Ripple marks

are

quasi-triangular

in

vertical cross-section

parallel

to

flow direction (Figures R6(A),(C-E))

or

wave

propagation (Figure

R6b).

Current ripples

are

asymmetric,

with gentle upstream face {stoss side)

and

steep downstream

face

{lee

side) approaching

or at

angle-of-repose. Individual

current ripples

can be up to

60 cm long

and

6

cm high,

but the

mean length

and

height

of a

field

of

current ripples

are

usually

<20cm

and

<2cm, respectively. Wave ripples

are

symmetric

or slightly asymmetric

in

cross-section (Figure R6(B)). They

can

be

200 cm long

and

23

cm high,

but

typical dimensions

are

an order

of

magnitude less.

566

RIPPLE,

RIPPLE MARK, RIPPLE STRUCTURE

suspension

settling

avalanching /,

(C)

BEDFORMS IN DEVELOPMENT

EQUILIBRIUM BEDFORMS

Figure

R6 (A)

Ripple

marks

in

vertical

profile

parallel

to

flow.

Terminology

is

based

on

Allen (1968)

and

Reineck

and

Singh

(1980).

Note

that

avalanching

and

suspension

settling

generate

cross-lamination depicted

in

(C)-(E).

vel. =

flow

velocity.

Water

depth

note

to scale. (B)

Plan

form

and

internal

structure

of

symmetrical

wave

ripples

with

rounded

crests.

Wave

ripple

crests

can

also

be pointed.

Wave

propagation

direction

is

perpendicular

to

crest

lines.

Note bundle-wise arrangement

of

cross-laminae.

(C)

Straight-crested,

(D)

Sinuous-crested,

and (E)

Linguoid

current

ripples,

with

characteristic

cross-lamination.

Flow

is

from

left

to

right.

Note

that

current

ripples

evolve

from

straight-crested

via

sinuous-crested

to

linguoid,

independent

of

flow

velocity.

Ripples

in (C) and (D) are

therefore

developing, and (E)

shows

equilibrium

forms.

Figures

(B)-(E)

after

Reineck

and

Singh

(1980).

Copyright

© 1980 by

Springer-Verlag.

All

rights

reserved.

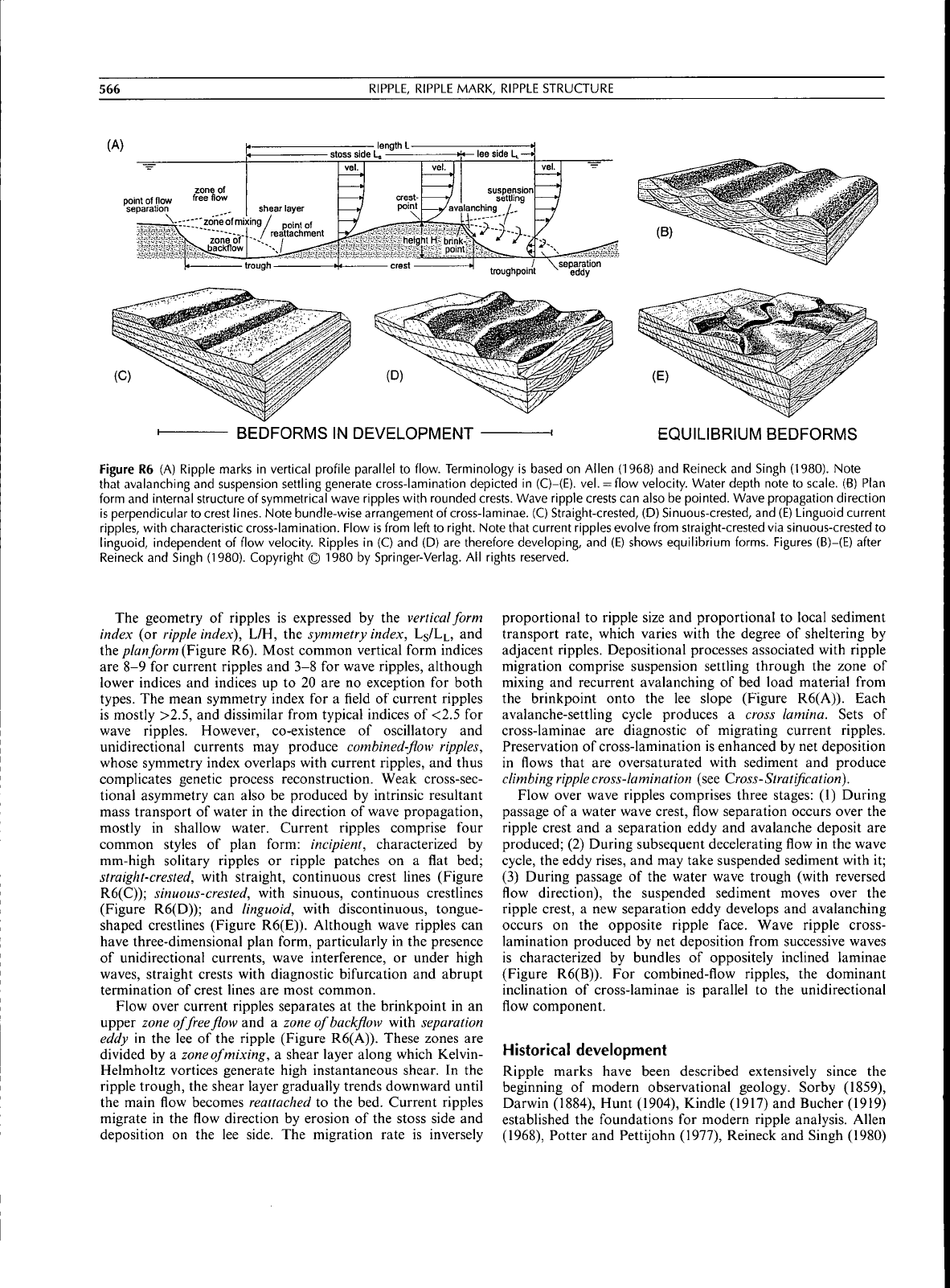

The geometry of ripples is expressed by the vertical form

index (or ripple index), L/H, the symmetry index,

LJ/LL,

and

the pianform (Figure R6). Most common vertical form indices

are 8-9 for current ripples and 3-8 for wave ripples, although

lower indices and indices up to 20 are no exception for both

types.

The mean symmetry index for a field of current ripples

is mostly >2.5, and dissimilar from typical indices of <2.5 for

wave ripples. However, co-existence of oscillatory and

unidirectional currents may produce combined-flow ripples,

whose symmetry index overlaps with current ripples, and thus

complicates genetic process reconstruction. Weak cross-sec-

tional asymmetry can also be produced by intrinsic resultant

mass transport of water in the direction of wave propagation,

mostly in shallow water. Current ripples comprise four

common styles of plan form: incipient, characterized by

mm-high solitary ripples or ripple patches on a flat bed;

straight-crested, with straight, continuous crest lines (Figure

R6(C)); sinuous-crested, with sinuous, continuous crestlines

(Figure R6(D)); and linguoid, with discontinuous, tongue-

shaped crestlines (Figure R6(E)). Although wave ripples can

have three-dimensional plan form, particularly in the presence

of unidirectional currents, wave interference, or under high

waves, straight crests with diagnostic bifurcation and abrupt

termination of crest lines are most common.

Flow over current ripples separates at the brinkpoint in an

upper zone of free flow and a zone of baekflow with separation

eddy in the lee of the ripple (Figure R6(A)). These zones are

divided by a zone of mixing, a shear layer along which Kelvin-

Helmholtz vortices generate high instantaneous shear. In the

ripple trough, the shear layer gradually trends downward until

the main flow becomes reattached to the bed. Current ripples

migrate in the flow direction by erosion of the stoss side and

deposition on the lee side. The migration rate is inversely

proportional to ripple size and proportional to local sediment

transport rate, which varies with the degree of sheltering by

adjacent ripples. Depositional processes associated with ripple

migration comprise suspension settling through the zone of

mixing and recurrent avalanching of bed load material from

the brinkpoint onto the lee slope (Figure R6(A)). Each

avalanche-settling cycle produces a cross lamina. Sets of

cross-laminae are diagnostic of migrating current ripples.

Preservation of cross-lamination is enhanced by net deposition

in flows that are oversaturated with sediment and produce

dimbing

ripple

cross-lamination (see Cross-Stratiflcation).

Flow over wave ripples comprises three stages: (1) During

passage of a water wave crest, flow separation occurs over the

ripple crest and a separation eddy and avalanche deposit are

produced; (2) During subsequent decelerating flow in the wave

cycle, the eddy rises, and may take suspended sediment with it;

(3) During passage of the water wave trough (with reversed

flow direction), the suspended sediment moves over the

ripple crest, a new separation eddy develops and avalanching

occurs on the opposite ripple face. Wave ripple cross-

lamination produced by net deposition from successive waves

is characterized by bundles of oppositely inclined laminae

(Figure R6(B)). For combined-flow ripples, the dominant

inclination of cross-laminae is parallel to the unidirectional

flow component.

Historical development

Ripple marks have been described extensively since the

beginning of modern observational geology. Sorby (1859),

Darwin (1884), Hunt (1904), Kindle (1917) and Bucher (1919)

established the foundations for modern ripple analysis. Allen

(1968),

Potter and Pettijohn (1977), Reineck and Singh (1980)

RIPPLE,

RIPPLE MARK, RIPPLE STRUCTURE

567

and Allen (1984) summarized further benchmark papers,

which include studies on ripples in recent and ancient

sediments, ripples in experimental flumes, and the theory of

ripple formation and stability. In the last two decades, ripple

marks have been used primarily in facies analysis. Yet,

innovative work continued in experimental flumes and

through mathematical modeling (e.g.. Miller and Komar,

1980;

Diem, 1985; Arnott and Southard, 1990; Gyr and

Schmid, 1989; Nelson and Smith, 1989; Best, 1992; Baas, 1994,

1999;

Werner and Kocurek, 1999; Baas et al., 2000). Best

(1996) and Raudkivi (1997) presented excellent reviews of

recent current-ripple literature.

Applications

Ripples and cross-lamination have been used as indicators of

stratigraphic younging and to reconstruct (paleo)flow direction

or (paleo)wave crest orientation. Moreover, ripples can be

used as estimators of local flow properties, notably flow type,

flow strength and sediment accumulation rate. Flow strength

can be constrained from bedform stability diagrams (see Surface

Forms).

Current ripples form at relatively low flow velocities

between the threshold for sediment movement and upper-stage

plane bed (for particles <~ 0.12 mm) or dunes (for particles

~0.12-0.7 mm). They do not form in cohesive clay and in

sand coarser than ~ 0.7 mm. Wave ripples exist in all silt- and

sand-grades, and between maximum oscillatory velocities for

the threshold of sediment movement and upper-stage

plane bed.

Unidirectional flows occur in many depositional settings,

which renders current ripples of limited use in paleoenviron-

mental reconstruction. Nevertheless, hydraulic conditions are

most favorable in sandy rivers, on intertidal flats, and in

turbidites. Wave ripples require relatively weak near-bed

oscillatory flow, such as on lake beaches, intertidal flats and

the marine shoreface. They are therefore better suited for

paleoenvironmental analysis than current ripples. Combined-

flow ripples have been found on intertidal flats and in other

shallow marine and coastal environments.

Ripple marks provide the sediment bed with form rough-

ness.

Form roughness is essential for calculating flow

resistance, bed shear stress and velocity distribution in

sediment transport analysis.

lit 1 • .

Current investigations and gaps in knowledge

Reflnement of existing models and development of new ideas

continually improve our knowledge of ripples. Present-day

work on current ripples concentrates on the mechanisms

controlling their formation (Best, 1992; Raudkivi, 1963;

Williams and Kemp, 1971), their rate of development toward

equilibrium morphology (Baas, 1999) and the feedback

relationships between ripple geometry and flow conditions

(e.g., based on "wave instability" theory by Richards, 1980).

A fleld of current ripples can be generated from a single,

artificial, or flow-induced, bed defect if the height of the defect

is large enough to induce flow separation at its lee side.

Baas (1994, 1999) demonstrated that current ripples

developing on flne- and very fine sand-grade flat beds evolve

from incipient, via straight-crested and sinuous-crested, to

linguoid equilibrium plan form with constant mean height and

length. Contrary to earlier work (e.g., Allen, 1968), the

equilibrium dimensions were found to be independent of flow

velocity. Velocity governs merely the time needed to reach

equilibrium geometry, which may range from several minutes

to hundreds of hours. Baas (1993) proposed relationships

between sediment size, D, and equilibrium current ripple

height, //,., and length, L^ {cf. Raudkivi, 1997):

3.41ogZ)-f 18

75.4 log Z)+197

mmm

(Eq. I)

Although the above model has been applied successfully to

current ripple dynamics in tidal environments (Oost and Baas,

1994) and used to reconstruct sedimentation rates in turbidites

(Baas etal., 2000), several gaps in our knowledge remain. First,

the role of turbulence in the growth rate of current ripples has

never been assessed in detail. Second, aggradation promotes

current ripple preservation, but no comprehensive study of its

influence on ripple dynamics exists, particularly under condi-

tions of turbulence modulation. This knowledge would

strengthen the use of current ripples in (paleo)hydraulic

recqnstructions, and in the determination of drag coefficients

in sediment transport calculations.

The latest studies on wave-induced bedforms concentrate on

the sediment entrainment under oscillatory and combined

flows, and the dynamics of such flows over wave and

combined-flow ripples (e.g., Traykovski etal., 1999; Paphitis

etal., 2001). This work will remain important, considering the

complexity of the feedback relationships between flows and

bedforms. A better process-based distinction between com-

bined-flow and current ripples is needed, as the use of indices is

unsatisfactory. This could be achieved by exploring potential

differences in grain shape fabric of current, wave, and

combined-flow ripples.

Jaco H. Baas

Bibliography

Allen, J.R.L., 1968. Current

ripples:

their

relation

to patterns of water and

sediment motion. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Com-

pany.

Allen, J.R.L., 1984. Sedimentary struetures: their

character

and physical

basis. Elsevier.

Arnott, R.W., and Southard, J.B., 1990. Exploratory flow-duct

experiments on combined-flow bed configurations, and some

implications for interpreting storm-event stratification. Journalof

Sedimentary Petrology, 60:211-219.

Baas,

J.H., 1993. Dimensional analysis of current ripples in recent and

ancient depositional environments. Geologica Ultraieetina, 106:

199pp.

Baas,

J.H., 1994. A flume study on the development and equilibrium

morphology of small-scale bedforms in very fine sand. Sedimentol-

ogy, 41: 185-209.

Baas,

J.H., 1999. An empirical model for the development and

equilibrium morphology of current ripples in fine sand. Sedimen-

tology, A6: 123-138.

Baas,

J.H., Van Dam, R.L., and Storms, J.E.A., 2000. Duration of

deposition from decelerating high-density turbidity currents. Sedi-

mentary Geology, 136: 71-88.

Best, J.L., 1992. On the entrainment of sediment and initiation of bed

defects: insights from recent developments within turbulent

boundary layer research. Sedimentology, 39:

797-811.

Best, J.L., 1996. The fluid dynamics of small-scale alluvial bedforms.

In Carling, P.A., and Dawson, M.R. (eds.), Advanees in Eluvial

DynamiesandStratigraphy. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 67-125.

Bucher, W.H., t919. On ripples and related sedimentary surface forms

and their paleogeographic interpretations. American Journal of

Science, 47: 149-210, 241-269.

568

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

Darwin. G.H,, 1884. On the formation of ripple-mark. Proeeedingsof

the Royal Soeiety of London, 36,

18-43.

Diem, B., 1985. Analytical method for estimating palaeovvave climate

and water depth from wave ripple marks. Sedimentologv, 32: 705-

720.

Gyr, A., and Schmid, 1989. The different ripple formation mechanism.

Journatof Hydraulic Research, 27: 61-74.

Hunt, A.R., 1904. The descriptive nomenclature of ripple-mark. Geo-

logical Magazine, 1: 410-418.

Kindle, E.M., t917. Recent andEossit Ripple-Marks. Museum Bulletin

ofthe Geological Survey of Canada, Volume 25,

pp.121.

Miller, M.C., and Komar, P.D., 1980. Oscillation sand ripples

generated by laboratory apparatus. Journal of Sedimentary

Petrol-

ogy, 50: 173-182.

Nelson, J.M., and Smith, J.D., 1989. Mechanics of flow over ripples

and dunes. Journal of

Geophysical

Research, C, Oceans, 94: 8146-

8162.

Oost, A.P., and Baas, J.H., 1994. The development of small-scale

bedforms in tidal environments: an empirical model and its

applications. Sedimentologv, 41: 883-903.

Paphitis, D., Velegrakis, A.F.,'Collins, M.B., and Muirhead, A., 2001.

Laboratory investigations into the threshold of movement of

natural sand-sized sediments under unidirectional, oscillatory and

combined flows. Sedimentotogy, 48: 645-659.

Potter, P.E., and Pettijohn, F.J., 1977.

Paleocurrents

and Basin Analy-

sis.

Second, corrected, and updated edition. Springer-Verlag.

Raudkivi, A.J., 1963. Study of sediment ripple formation, Journalof

the Hydraulics

Division,

Proeeedingsof ASCE, 89:

15-33.

Raudkivi, A.J., 1997. Ripples on stream bed. Journal of Hydraulic En-

gineering, 123: 58-64.

Reineck, Fi.E., and Singh, I.B., 1980. Depositionat Sedimentary Envir-

onments, with Reference

to Terrigenous

Clasties. Second, revised and

updated edition. Springer-Verlag.

Richards, K.J., 1980. The formation of ripples and dunes on an

erodible bed. Journal of Eluid Meehanics, 99: 597-618.

Sorby, Pl.C, 1859. On the structures produced by the currents present

during the deposition of stratified rock. The

Geologist,

2: 137-147.

Traykovski, P., Hay, A.E., Irish, J.D., and Lynch, J.F., 1999.

Geometry, migration, and evolution of wave orbital ripples at

LEO-15.

Journal of

Geophvsical

Research, C, Oceans, 104: 1505-

1524.

Werner, B.T., and Kocurek, G., 1999. Bedform spacing from defect

dynamics. Geology, 27: lH-l'iQ.

Williams, P.B., and Kemp, P.H., 1971. tnitiation of ripples on flat

sediment beds. Journal of the Hydraulics Division, Proceedings of

ASCE, 97: 505-522.

Cross-references

Angle of Repose

Bedding and tnternal Structures

Bedset and Laminaset

Cross-Stratification

Desert Sedimentary Environments

Flow Resistance

Flume

Paleocurrent Analysis

Sediment Transport by Tides

Sediment Transport by Unidirectional Water Flows

Sediment Transport by Waves

Sedimentologists

Surface Forms

Turbidites

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

Introduction

A river is a natural stream of water that under the influence of

gravity flows regularly or intermittently in a channel or

channels toward a receiving basin, commonly an ocean or

lake.

Rivers are open systems in which energy and matter are

exchanged with the external environment (Knighton, 1998).

They are supplied with water almost entirely from precipita-

tion (meteoric water) routed to the channel via overland flow,

groundwater, swamps, lakes, snowfields, and glaciers, and they

acquire most of their sediment load by dissecting uplands or by

reworking unconsolidated debris from previous erosional

events. Sediment deposited by rivers in subaerial settings is

called alluvium. Consequently, rivers are divisible into bedrock

reaches with rigid boundaries, and alluvial

reaches

that have a

mobile boundary of relatively unconsolidated material, often

with vegetation assisting channel stabilization. Rivers drain

catchments (drainage basins or watersheds), are organized into

complex patterns of trunk, tributary, and distributary chan-

nels,

and commonly support adjacent floodplains that are

inundated when the channels exceed bankfull capacity. Their

headwaters are principally in upland areas and they may flow

throughout the year (perennial) or cease for part of each year

(intermittent if flow is seasonal and ephemeral if flow is

irregular). Due largely to tributary contributions, river systems

generally increase in discharge and channel dimensions down-

stream, however, in areas of permeable sediment or aridity,

percolation, and evaporation may cause channels to reduce or

disappear.

While only about 0.005 percent of continental water is

stored in rivers at any one time (Knighton, 1998), rivers

transport to depositional sinks the great majority of sub-

aerially weathered and eroded sediment as well as dissolved

material. River drainage networks occupy about 69 percent of

the land area, transporting an estimated 19 billion tonnes of

material annually, about 20 percent of which is in solution.

Denudation rates and river load reflect primarily the effects of

climate,

relief,

and tectonic uplift, as well as rock, and soil

type,

catchment size, vegetation cover, and human influence.

Upland rivers are commonly bedrock systems that form a

sediment source zone (Schumm, 1981). They are typically

erosional with very limited sediment storage. Intermediate

reaches usually form a transfer zone with disjunct areas of

bedrock erosion and temporary deposition. Lowland rivers are

dominantly alluvial. They lose competence to form a sinkzone,

depositing their load in floodplains, alluvial fans, lakes, desert

basins (internal sinks), or in marine deltas, estuaries, lagoons,

continental shelves, and ocean basins (external sinks). Many

rivers have responded to sea-level fluctuations by cutting and

filling their lowermost valleys.

Fluvial strata constitute about 10-20 percent of the

Phanerozoic rock record, with many predominantly alluvial

deposits in excess of

10

km thick. The oldest known fluvial

deposits are in the Archean of southern Africa, where they

date back to more than 3.5 Ga and reflect the emergence of

continental crust and establishment of subaerial weathering.

Alluvial detritus is formed principally of silicate gravel, sand,

and mud, with volcanic, carbonate, and evaporite grains, and

particles of gold, tin-bearing minerals, and other economic

materials (see Placers, Fluvial). Some deposits contain huge

boulders derived from rock falls and catastrophic floods in

steeplands. Rivers that traverse peatlands and densely vege-

tated regions transport large amounts of plant material and

dissolved and colloidal organic matter, and these blackwater

streams contribute significantly to the carbon content of

sediments in sink zones. Alluviai strata include a wide range of

sedimentary structures mostly generated by unidirectional

RIVERS

AND

ALLUVIAL FANS

569

flow. Floodplain deposits

are

usually associated with soil

formation

and

consequently,

in

combination, alluvial strati-

graphy

can

reveal

a

detailed story

of

variable flow eonditions

and changing terrestrial en\ironmenls over spaec

and

time.

Historical developments

The importance

of

river erosion

and

landscape formation

was

elearly recognized

in

classical times. Whereas Thales

of

Miletus

(/».

-624 BC)

thought that deltas building into

the sea

were

evidenee that water could change into sediment. Herodotus {b.

484

BC)

identified seditnentation

and

de.seribed

the

alluvial

plains

of

Egypt

as the

"'gift"

of the

Nile. Plato

(/>. 428 BC)

clearly reeognized fluvial erosion

and

transportation. Aristotle

(/'.

3S4

BC)

was the

first seholar known

to

have eoncepttialized

the modern hydrologieal cycle

and he

also identified river

erosional

and

depositional proeesses, partieularly those

on the

Nile

and the

silting

up of

river channels entering

the

Black

Sea.

Strabo

(^.

64/63

BC)

described floodplains

as

having been

formed

of

sediment from their adjacent rivers. However,

between Roman times

and the

Renaissanee

a

long scientific

interregnum prevailed

in

Europe, with

a

widespread belief that

ihe Earth's surface

had

been shaped

by

eatastrophie proeesses

associated with

the

biblical Great Flood

(the

Diluyialist

iheory).

After

the

geologieal importance

of

hydraulies

and

river

proeesses

was

rediseovered

by

Leonardo

da

Vinci. Agrieola,

Bernard Palissy, George Bauer

and

others

in the

i5th

and 16th

Centuries,

the

importance

of

fluvial processes through

geological time

was

questioned again

in the 18th

Century

due

to a

group lead

by a

German .scholar, Abraham Werner.

Known

as the

Nepiunisis. ihey proposed that

the

tock record

represented itepositicm

in

deep oceans where powerful currents

had earved valleys

and

ridges, restricting alluvial influence

to

modern rivers

and

their sediments. James Hutton

in the 18th

Century

was the

first post-elassieal seholar

to

elearly reeognize

and articulate

the

importance

of

modern-day processes

to

explain features visible

in

ancient roeks,

the

basis

of his

principle

of

Unilbrmitarianism.

He saw

that long-term fluvial

erosion

was the

erosive mechanism active

in the

repetitive

cycles

of

landscape denudation: No trace of a

hegittnittg,

ttopro-

speetofanend.

He

argued that fluvially eroded debris from

the

land created most

of the

detritus appearing

in

ancient

sedimentary strata,

and

henee

he and his

followers becatiie

known

as the

Fluyialist.s. Hiitton's concepts were clearly

espoused

by

Charles Lyell

in the

many editions

of

his seminal

book

Tbe

Principles of Geology

(1830

'|833).

ll

was not

until

the

lale

19th and

early 20th Centuries that

modern

and

ancient river deposits

and

fluvially eroded

landscapes received widespread

and

detailed investigation,

espeeially from North Amerieans stich

as J.W.

Powell during

exploration

and

settlement

of

that continent.

G.K.

Gilbert

(1877) was

the

first

to

apply

the

concept

of

dynamieequdibriiitn

to rivers,

and W.M.

Davis

in the

late 1890s proposed

the

normal

or

fluvial cyele

of

erosion

and

landscape change that,

although

now not

wholly aeeepted. fostered

a

widespread

interest

in

modern geology

and

geotiiorphology. Davis

was

probably

the

first person

to

recogni/c braiding

as a

river

pattern distinctly different from meandering.

In 1925. J.

Barrell demonstrated that seditnentary strata, hitherto widely

ihought

to be

deposited

in

marine environments, were

in

many

eases terrestrial ineluding fluvial.

The

outstanding study ofthe

Mississippi Ri\er

by H.

Fisk (1944) deseribed

the

fluvial

geomorphology. sedimentology.

and

stratigraphy

of a

very

large river system. Miall (1996) regarditig this work

as the

first

major advance

in

modern fluvial sedimentology.

Post-war fluvial faeies analysis, strongly linked

to

drilling

and exploitation

of

hydrocarbon reservoirs,

led in the

I96()s

lo

J.R.L. Allen's eomprehensive model

for

meandering-river

deposits,

the

first

fbr any

environmental setting. Undoubtedly

the most significant modern advanees

in

understanding river

form

and

process originated from research

by L.B.

Leopold.

M.G. Wolman.

S.A.

Sehumtn.

J. M.

Miller

and

their assoeiates

in

the

1950s

and

1960s.

R.A.

Bagnold

(see

Fliysies of Sediment

FransportiThe Coniributiotisof

R.

A.

Hagttold) greatly advanced

seditnent transport theory,

and A.

Sundborg described

in

detail tneandering ri\er processes

and

floodplain sedimentol-

ogy. providing important Kuropean conlribuliotis. .Sediment

dynamic e.vperiments. following studies

in the 19th

Century

by

H.C. Sorby. allowed detailed faeies interpretation

in

hydro-

dynamie ternis

(see

Flumes: Sediment Transport

by

Unidiree-

tionat

Flows).

With

the

development

of

radioearbon dating

in

the late l'-)40s

and

luminescence dating

in the

1970s,

the

means

of dating Quaternary alluvium became available, allowing

fluvial sediments

and

paleoflow rcgitnes

to be

related more

precisely

to

wider controls, principally tectonic aetivity,

eustasy.

and

clitnate ehange.

Theoretical underpinnings

II

has

been tecognized since

the 18th

Century that quantitative

analysis

in

fluvial studies

has

been

of

necessity

a

compromise

between theory (based

on

"ideal nonviscous fluids")

and

etnpiricism (based

on

real viseous lluids).

a

problem known

as

the d"Aietnbert paradox. Despite major advances,

the

devel-

opment

of

unifying theories

in

fluid mechanics

and

sediment

transport remain elusive. Empirical research into stoehastie

relationships

has

shown that,

as

flows vary, rivers construct

highly predictable channel forms

and

sedimentary structures.

However,

a

truly rational

or

deterministic explanation

for

such

consistency

has not

been possible

due to a

lack

of

mathema-

tical closure,

for

while there

are

four flow \ariabies (width,

deplh. veloeity,

and

slope) fhere

are

only ihree detertnining

eq tuitions (eotitiiniity, resistance,

and

sediment transport).

Solutions have been sought

by

adopting extremalbypothe.se.i.

If

fluvial and thermodynamic systems

are

compared, rivers

may

be visualized

as

adopting

a

most probable state

by

minimizing

both

the

variance

of the

system's

How

components

and the

total work done. More strongly physically-based extremal

hypotheses have been proposed

by

imposing assumed eondi-

tions sueh

as

maximum sediment transport rate

or

minimum

stream power.

In a

reeent reassessment

of

sotne

of

these

approaehes. Huang

and

Nanson (2000) have demonstrated

mathematically that straight reaehes

of

alluvial rivers appear

to operate

at

maximum efficiency

and

illustrate

the

basic

physical Frineiple

of

Lea.it Aetion. However, such theoretieal

analyzes remain contentious.

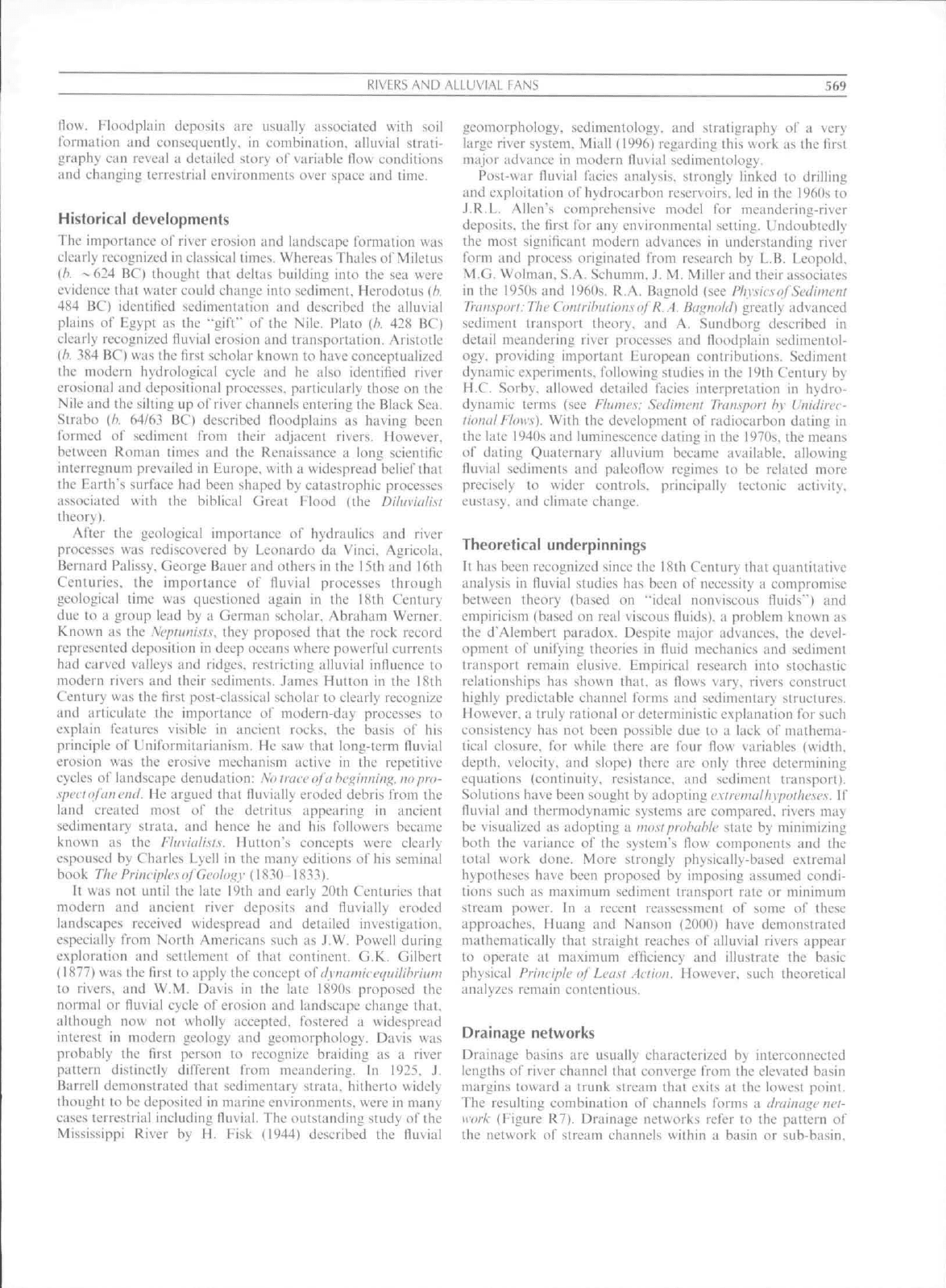

Drainage networks

Drainage basins

are

usually characterized

by

interconnected

lengths

of

river ehannel that converge frotn

the

elevated basin

margins toward

a

trunk stream that exits

at the

lowest point.

The resulting eombination

of

ehannels forms

a

drainage net-

work (Figure

R7).

Drainage networks refer

to the

pattern

of

the network

of

stream ehannels wilhin

a

basin

or

sub-basin.

570

kiVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

Order - Formative streams

Order - Excess Streams

- - ' Exterior links

• --' Interiof links

Figure R7 Drain.ige-basin s!ream networks with stream ordering: (A) as

by Horton (194'j) (modified by Slr<ihler); (B) channel links nrdered by

magnitude (atter Knighton, f 998).

and should not be confused with .siteatnpatterns that refer to

the planform appearanee of individual reaehes of river (e.g.,

tneandering and braiding, see below). They are usually

erosional features and have been mapped in the strafigraphic

reeord where unconformable surfaces separate bedroek from

overlying alluvium. Headwater streams are normally relatively

small, steep, often bedrock controlled with uneven gradients,

and the bases of the hillslopes are eonneeted direetly to the

stream ehannels such that rates of ehannel incision and

sediment removal relate closely to slope proeesses. Down-

stream, the basin channels are of lower and tnore uniform

gradient, and are cotnmonly self-forttted. being shaped within

their own alluvium. Although in places they may connect with

the hillslope. it is more eommon that alluvial terraces and

floodplains act as a temporal and spatial buffer between

channel and slope proeesses. Channel links are a length of

channel from the source to the first tributary {externallink) or

between two suecessive tributaries (iniernal

link).

In

f945.

Horton developed a system of ordering chainiel links within

drainage networks in a downstream direction (Figure R7(A)).

This provides a useful classification of the position of streams

within a network, although link order is not a reliable

indicator of channel size or discharge. To determine link mag-

nitude, eaeh link is assigned the value of the sum of all the

external links supplying it, providing a useful surrogate to link

discharge (Figure R7(B)).

In terrain of homogeneous or alternatively highly complex

geological structure, drainage networks tend to take on a

strongly irregular dendritic pattern. However, where well-

defined and relatively simple geologieal struetures are present

(faults, folds, domes, volcanic cones, rectangular joints etc.).

visually distinctive and sotiiewhat regular drainage patterns

can form. Drainage networks are highly amenable to

numerical analysis and in consequence they have been studied

in great detail in attempts to interpret their controlling

variables, internal relationships, sediment yields and their

relationship to both catchment and overall landscape evolu-

tion. However, because most networks are dendritic, their

essentially irregular pattern means that few physically defini-

tive relationships have been identified, except perhaps those

from topofogieal studies that have pointed out the spatially

nonrandom elements present.

The most widely used and probably useful statistic derived

from drainage network analysis is that of drainagedensity (the

total length of ehannels per unit area ofthe basin). It expresses

the degree of basin disseetion and sediment produetion and

transport by surfaee streams, and is influenced by sueh

variables as elimate, roek, and soil type, vegetation density,

and landuse. Highly impermeable, soft, and poorly vegetated

roeks can produce high drainage densities and sediment yields

(e.g.. badlands). Drainage density is also broadly eorrelated

with preeipitation. It is low in very arid areas, greatest in semi-

arid areas where there is suftieient rainfall to eause erosion but

insufficient vegetation to itnpede it, and lower again in more

humid areas with denser vegetation. It appears to partially rise

again in very wet areas where the stabilizing effeets of even

dense vegetation are overeome.

Stream gradients

Stream gradients are the result of two broad eauses. An

independent gradient is imposed on the stream by the gross

valley form, the produci of geologieal and drainage history.

However, an adjustable and therefote dependent eomponent

of gradient develops frotn the interactton of st rea tn dtseharge,

width, depth, velocity, seditncnl size, sediment load, boundary

roughness, and path sinuosity. Mackin (1948) stated that a

gradedtirequilibrium stream (see below) is one in which, over a

period of years, slope is delicately adjusted to provide, with

available discharge and prevailing channel characteristics, just

the veloeity required for the transportation of the seditnent

supplied from upstream. Confined upland streams are

generally not equilibrium alluvial systems beeause their

gradients are largely imposed by a bedroek valley that is the

produet of ancient stream erosion or forces such as glaciation

and teetonism. It is in the middle or lower reaehes where the

valley is wider that the stream can more readily adjust its

gradient by altering its sinuosity and hence its path length in

response to contetnporary eonditions. Change in ehannel slope

accounts for only part of the adjusttnent of alluvial rivers to

their controlling factors and, more realistically, the ehatinefs

variotis morphological and hydraulic parameters tend to show

mutual adjustment.

Over their full distance, the longitudinal profiles of natural

rivers show a strong tendency to become concave upward. This

eoncavity is assoeiated with at least three possible causes,

although the direetions of cause and effeet are difficult to

resolve. F'irstly. there is a tendency iti most rivers fbr discharge

to increase downstream but for velocity to remain fairly

constant. Discharge (a volume) increases as a cubic function

whereas the resisting boundary of the channef (the area of the

bed and banks) inereases only as a squared function. If the

gradient did not deeline substantially an imbalance between

impelling and resisting forces would result and the Mow would

accelerate rapidly downstream. Profiles tend to be most

concave where discharges increase downstream most rapidly.

Secondly, grain size cotntnonly declines downstream due to

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

571

elast abrasion (see .Attrition, Fluvial) and size sorting, so the

gradients required for sediment entrainment and transport will

decline downstream. Stream profiles are more concave where

eiast sizes deeline in size downstream tnost rapidly and show

little concavity where grain size is constant or increases. Slope

decreases tnost rapidly with a deeltne tn gravel stze and least

wilh a decline in sand size. Because ofthe production of finer

clasis.

streams over shale tend to have gentler gradients than

those over sandstone or limestone, although concavity depends

on the eotnbined effeets of grain size and discharge. A third

possible reason for profile coneavity is that antecedent relief

and potential energy conditions along a river from headwaters

to mouth eause random-walk models to develop concavity as

the tnostprt>b(tNe profile. In relation to this proposal it has

been Ibund that shorter streams tend to have less eoncave

profiles and streams with greater relief exhibit greater

eoncavity.

Marked ehanges in river gradient are termed knickpoints.

and may refleet the presence of more resistant bedrock.

changes in sediment load (fbr example, from tributary

streams), tectonie activity, or base-level changes in the past.

Fustatic or other base level ehanges tend nol to be propagated

over long distances upstream unless the stream is eonfined

and ean nol readily adjust other parameters such as

sinuosity.

Biota and soils

Prior to the tnid Paleozoic, subaerial erosion was dominantly

physical and prodticed abundant coarse material, with river

forms probably reminiscent of today's active glacioiluvial or

volcanic landscapes. In the late Silurian and Devonian the

evolution of terrestrial plant eotnnutnities and associated soils

greatly enhanced chetnical weathering and the production of

clays.

The development of cohesive stream banks and

stabilizing root systems must have ehanged rivers dramatically

in the late Paleozoic, promoting the accumulation of

substantial argillaceous and organie deposits in terrestrial

environments and strongly affeeting global patterns of earbon

producf ion and storage. The development of terrestrial

vegetation also redueed runoff and allowed the diversifieation

of a complex array of lloodplains and associated soil types in

environments ranging from rainforests to grasslands (af\er the

mid Cenozoic) and deserts. The first peats (precursors to coal)

were deposited in the Devonian and peat has subsequently

been an important component of fluvial strata. The rapid

succession of plant communities in response to climate ehange.

termed lltnvl overturn, should have exerted an itnportant

influence on sedinient flttx to depositional basins.

There is now appreciation ofthe importanee and eomplexity

of river-vegetation interactions. Particular attention has been

given to the efTeet of vegetation growing within channels on

flow resistanee, of bankline vegetation and debris dams on

bank strength and ehannel tnorphology, and of riparian

\egetation generally on floodpfain and ehannel seditnentation

atid erosion. Wildfires destroy vegetation and protnote land-

scape degradation, greatly increasing sediment yield and

adding ehareoal to the fossil record.

!-loodplain soils ean be diagnostic of particular environ-

ments, eontaining evidetice in the form of poifeii and spores,

invertebrate remains, burrows, rhizotnorphs, evaporites, and

desiccation cracks (see Weathering, Soils, and

Paleo.sols).

For

this reason and beeause soils develop through close interaction

with the atmosphere and the groundwater prism, they are

important repositories of information about past climates.

Large animals, including hippopotamus, beaver, and perhaps

dinosaurs, have affeeted rivers by trampling sediments,

damming ehannels, and ereating paths aeross banks that can

lead to avulsion.

River hydraulics and sediment entrainment

Flow m open channels is subject to tuo roughly opposing

prineipal forces. Acceleration due to gravity {g) acts to move

water and seditnent downslope with its effectiveness modilied

by stream gradient [S). while flow resistanee (channef rough-

ness) (see Fhny Resistanee) opposes this downslope motion.

The interaction of these two forees ultimately determines the

ability of flowing water to erode and transport sediment, and

thereby generate fandforms. Flow in rivers is almost always

turbulent. The flow boundaries including the water surface are

deformable. thereby changing the shape, roughness, and

energy conditions in the ehannel as the flow changes.

Frictional losses are the product of boundary roughness,

internal distortion, and changing flow phases (super- fo sub-

eritieal). All these factors make fluid tneehanies much more

complicated than solid mechanies, however, relatively simple

empirieal formulas have been developed to obtain approx-

imate relationships suitable fbr most straightforward analy-

tieal procedures.

River discharge (Q)\

Q = wdy

(Eq.

where tt= ehannel width; (/=mcan depth;

v

= mean velocity.

This is known as the

flow

continuity eqttatiott.

Mean boundary shear stress (r):

z^/RS

(Eq.2)

where 7 = speeifie weight of water; /? = hydraulie radius ^d.

{•;

=

!>

g, where /) is water density). This is known as the Du

Boys

equation.

Channel roughness or How resistanee is commonly obtained

from one of two equations;

Manning equatkni:

n=\/vR-''S^^' (Eq. 3)

Darey

IVeisbaeli

eqtiatiott:

f = SgRS/v- (Eq. 41

The work done by a river ean be expressed in terms of stream

power in two fbrms:

Power per unit length ofthe channel:

Q^VQS (Eq. 5)

Power per area of the bed:

ff.! = ,' QS/w (Eq. 6)

While suspended and dissolved sedimetit load can be relatively

easily measured the more eomplex problem of determining bed

load is usually attempted using one of many available

transport equations, none of whieh are reliable over a wide

range of conditions (see Nutverical Models and Simulation of

Sediment

Transport

and

Depositloti;

Seditnent

Flu.xes

attd Rates

ofSeditventation). These equations ean

be

classified info three

S72 RIVERS AND ALLUVIAf FANS

basie types (Knighton. 1998):

Excess shear stress

(r,,-r,~,):

a

h

= X' r (r - r 1

Excess discharge

Iq-q,-,)'-

q^H

=

X".s'[q

- q,,)

Excess stream power

((»-<

Du Buys type

Schoklitsch type

(Fq. 7)

(Fq. 8)

q,i,

^ ivj -

oj,,)-^'-

d-^ /?-'•'= Bagnold type (Fq. 9)

In the above, ty^/, is bed load per unit channel width. X' and X"

are sediment coefficients. D is grain size, q is How discharge per

unit width of channel and the subscript "CT" denotes the

eritieal eondition fbr sediment motion.

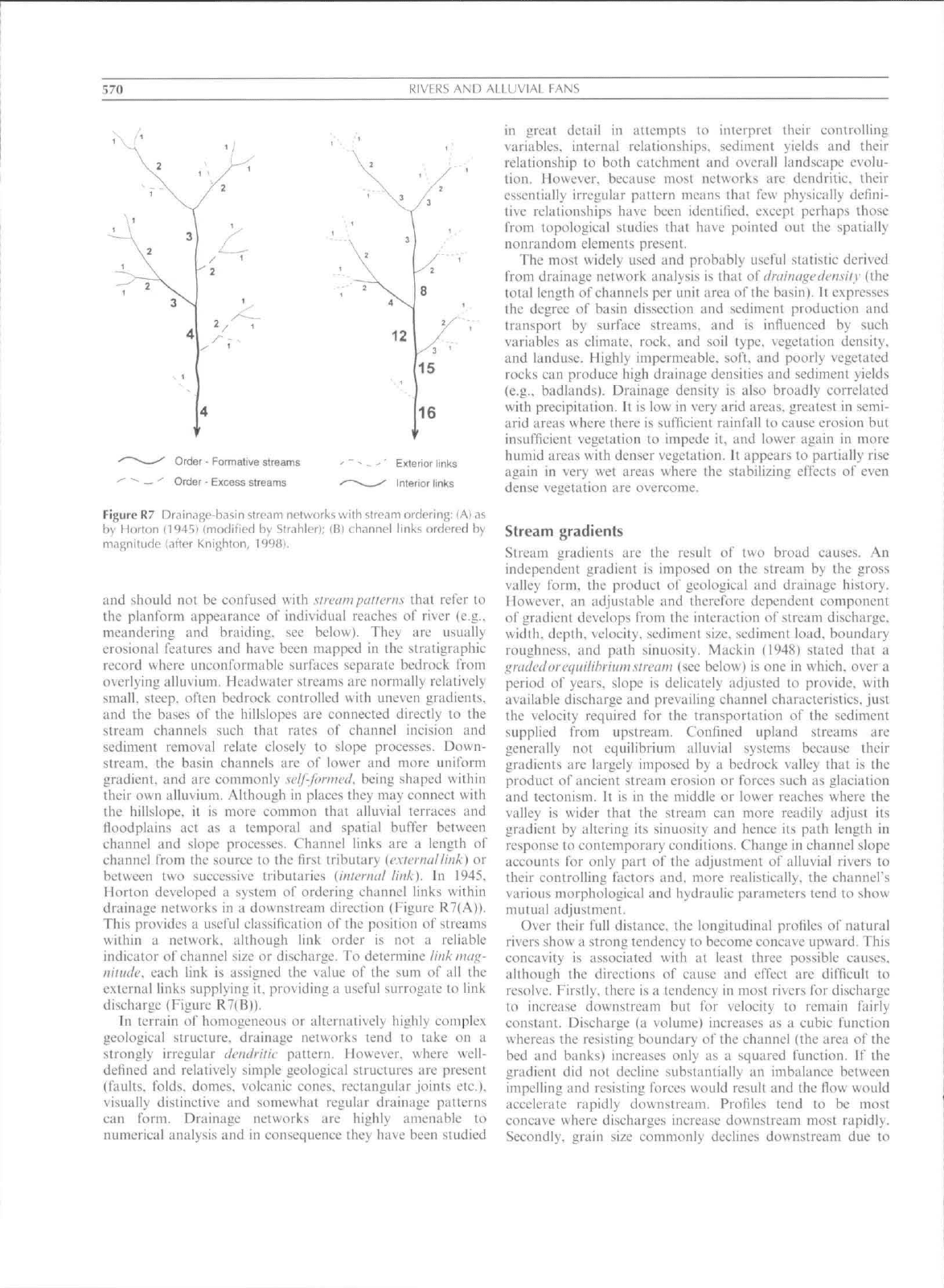

In a straight river eross section, the flow velocity is usually

fastest at or just below the surface near the eenter of the

channel and declines toward the bed and banks, the How field

def\>rniing through river bends (Figure R8). A narrow deep

ehannel usually directs a relatively gentle veloeity gradient to a

fine-grained bed that requires low shear stresses for transport.

and directs relatively steep gradients to banks that are often

cohesive, well vegetated, and erosion resistant. Wide shallow

ehannels tend to exhibit erodible banks and coarse and/or

abundant bed load that requires high shear stress for

transport, braided rivers being a classic type.

The erosion of cohesive material such as bedrock or

partially indurated alluvium occurs in three ways. Corrosion

is the chemical dissolution of roek in water and ean be

important where rocks are readily soluble (e.g.. limestone) or

where water is chemically active. Corrasion occurs when rock

is mechanically braided by water armed with partieies cither in

transport or stationary but vibrating on the roek surfaee. Ca-

vitation results from the produetion of shock waves due to the

formation and implosion of vapor bubbles on rock surfaces at

very high velocities. This is a rare proeess in tnost subaerial

streams but can be common in subglacial or underground

streams where flow is eonfined.

The entrainment of noncohesive sediment from the bound-

ary is a eomplex process but largely a function of flow velocity

and grain size. In the ease of gravels, the sorting, and packing

arrangements ofthe elasts on the bed are also important, for

an armored or itnbrieated bed can be diffictilt to entrain (see

Arnu>r).

As flow veloeity increases two dominant fbrees act to

entrain individual clasts. A drag force caused by friction

between the flow and the surfaee of the particle causes it to

(B)

Figure R8 Velocity fields in cross sections ot; (A) a wide shallow

channel (note tho steep velocity gradient to the bed): (B) a narrow deep

channel bend viewed downstream and curving to the left (note ihe

steep velocity gradient against the outer

move downstream and to slide or roil (or pivot) over

any obstructing particle. However, as velocity increases a

pressure gradient develops between the top and bottom of the

grain setting up a lift force that acts to lift tbe partiele out of its

recess on the bed. The lift force decreases rapidly away from

the bed but once the partiele is elevated it is far rnore

suseeptible to the drag foree and to turbulent eddying within

the body ofthe flow that acts to keep partieies in motion. The

entrainment of sediment on the boundary ean be expressed in

terms of mean flow velocity and mean grain size, but the

problem is to define the threshold velocity for motion on an

imbricated or armored bed, or whete grain size is highly

variable.

The competence of historic or prehistoric flows is commonly

judged from the size of the largest partiele in the resulting

deposit, although such estimates may suffer from the limited

availability of coarse sediment. Fine-grained, eohesive deposits

require mueh higher flow velocity for entrainment and

transport than the size of individual grains would suggest.

Sueh materials inelude bed and bank tnaterial. sand-sized mud

aggregates reworked from soils, and floes of aggregated elay.

organistns. and detrital organie material in rivers and estuaries

(e.g.. Gibling eial.. 1998). Beeause aggregates and lines are

comtnonly destroyed by eompaetion during burial, flow

competence tnay be diffieult to assess fbr some fine-grained

material, whieh may have originated as sand-sized bed-load

rather than from settling of suspended flakes.

Equilibrium and threshold theories

Because alluvial rivers are open systems with mobile and

deformable boundaries, they have the ability to self regulate, lf

perturbed, they will often return to something like their

original eondition (homeostasis). or they will adopt a new form

but one that minimizes the effects of the original change. This

reflects dynamie equilibrium, a eondition first described for

rivers by Gilbert (1877) and applied widely in seienee.

especially ehemistry (Le Chatelier's Principle). Because rivers

are relatively slow to adjust and beeause their morphologieal

parameters adjust al different rates, it ean be difficult to

determine if a partieufar reach is in an equilibrium or balaneed

eondition. Nevertheless, the recognition that alluviai rivers

adjust toward equilibrium eonditions has becotne a basie tenet.

almost a paradigm of modern fluvial research. Richards (1982)

has suggested that equilibrium conditions in rivers can be

identified on the basis of four criteria: (1) essentially stable

relationships between form and process; (2) continuity of

sediment transport in a reach over time and space: (3) strong

correlations between systetn variables: (4) an adjustment to

maximum operational efficiency. In tnany studies roughly

balanced eonditions have been shown to exist over short

periods between erosion and deposition in a single reach, or

between width, depth, and velocity, tf one variable is altered,

the others adjust in a way that minimizes the overall change

and maintains a balaneed condition. Beeause flow conditions

and sedimentary bedforms are usually in dynamic equilibritim.

ancient flow structures permit an accurate interpretation of

paleoflow conditions.

Most ehanges in rivers are the result of external factors such

as changes in base level, clitnate. vegetation, or sediment

supply, and occur gradually. Rivers in dynamie equilibrium

generally resist change, however, Sehumm (1973) has shown

that an extrlttsie thresbold can be reached when a progressive

RIVERS AND ALLUVIAL TANS

573

change in an external variable triggers a sudden change in Ihe

system's response. At an imposed critical ehange of slope or

sediment load, a meandering channel can change abruptly to a

braided channel. Similarly, a gradual and progressive increase

in the llow velocity will suddenly achieve the threshold tor

sediment enlrainmeiit. after whieh the whole streambed

becomes mobile. There are numerous thresholds above critical

enlraiiiment when bedforms change from a motionless bed. to

ripples, lo dunes, to traitsitional. and to super-critical flow

bedfonns (see Surface Forma). Schumm (1973) also showed

that changes may be initiated intrinsically when, with no

external change, one of ihe variables reaches a eritieal

condition (an iiurinsic thrcslmld). While operating wilhin its

normal range

ot"

waler discharge and sediment load variation,

a river may reach a point of incipieni instability when a

threshold is crossed and a sudden internal ehange is initiated.

A meander eutofl" is an example where gradual, ongoing

adjustments to equilibrium eonditions prevail until a threshold

is reached, with breaching of the meander neck and a dramatic

chanye in loeal sinuosifv and gradient (Kiitiihton. iy9S).

Crossing an intrinsic threshold will normally produce only a

localized change recognizable in the stratigraphic record as. for

example, an avtilsion ehannel or erevasse splay.

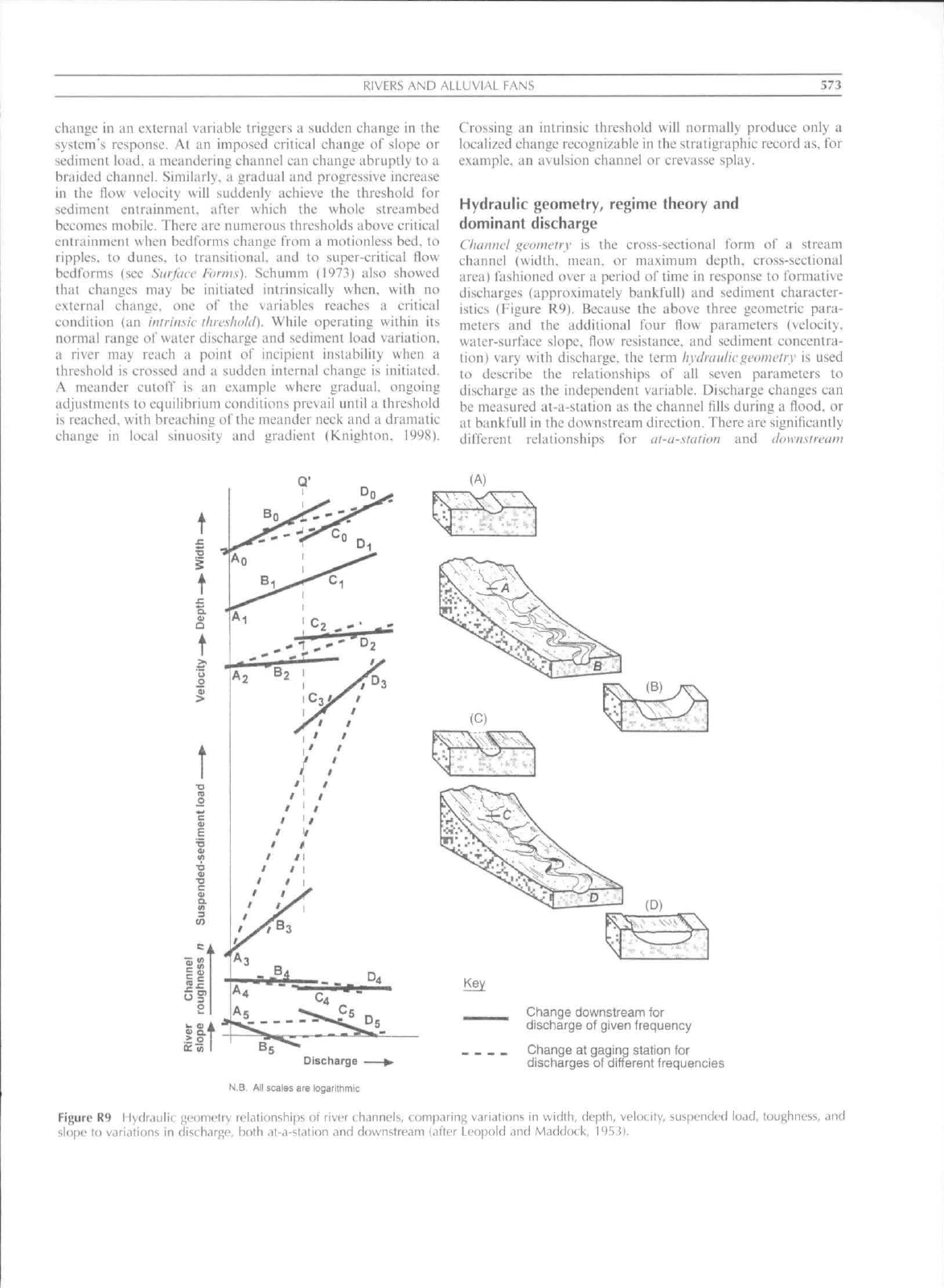

Hydraulic geometry, regime theory and

dominant discharge

Chiinnel geomcliv is the eross-sectional form of a stream

channel {width, mean, or maximum depth, cross-sectional

area) lashioned over a period of time in response to formative

diseharges (approximately bankfull) and sediment character-

istics (Figure R9). Beeause the abo\e three geometric para-

meters and the additional four flow parameters (velocity,

water-surface slope, tlow resistance, and sediment concentra-

tion) vary with diseharge. the term hyilraulicficomtiry is used

to describe the relationships of all seven parameters lo

discharge as the independent variable. Discharge changes can

be measured at-a-station as the channel fills during a flood, or

at bankfull in the downstream direction. There are significantly

different relationships for til-a-sldlioii and

Discharge

N.6.

AN

scales are logarithmic

Change downstteam for

discharge of given frequency

_ Change at gagitig station fot

discharges of different frequencies

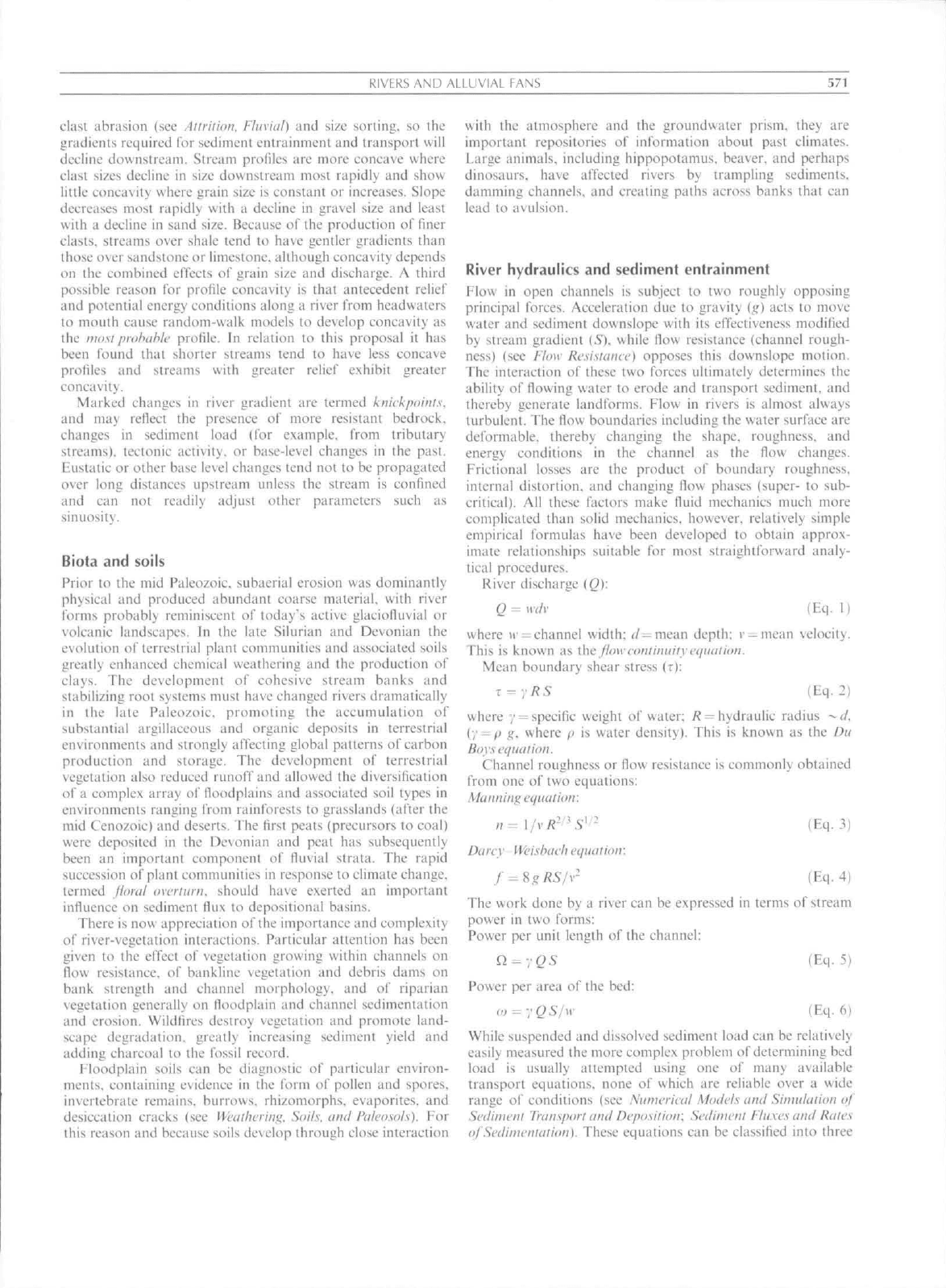

Figure R9 I Ivdr.iulic geometry relationships ol river (han nek, compjrinp variations in width, depth, velocity, suspended

load,

tnughness, and

sidpc lo varijlions in discharge, Ixilh <it-<i-station and downslretim (alter Leopold and Maddock, lO'i^).

574

RIVFRS AND ALLUVIAL FANS

hydraulic geometry (Figure R9). Holding diseharge constant,

at-a-station hydraulic geometry is largely conlrolled by

variations in bank, strength and available sediment

load.

Streams with low sediment loads and cohesive or

well-

vegetaled banks lend to be relatively narrow and deep whereas

those with abundant loads and weak banks tend to be wide

and shallow. However, beeause bank strength has only a

moderate range but river discharges vary by many orders of

magnitude, hydraulie geometry is remarkably eonsistent aeross

the full range of river discharges (Figure R9). Beeause channel

depth is greatly restrieted by limited bank strengths, rivers

increase in width relative to their depth as their size and

discharge inereases—a prominent downstream tendency

(Chureh.

1992).

Research during the construction and maintenance of

irrigation canals with near-constant diseharge in India and

Pakistan in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries indepen-

dently determined very similar hydraulic geometry relation-

ships to those in natural rivers, engineering findings that have

been termed reginwiheory. Consequently, stable alluvial rivers

exhibiting consistent and predictable hydraulic geometries are

said to be in eiiuilihriiini or in regime.

Hydraulic geometry shows that river ehannel dimensions are

closely adjtisted to water discharge. However, discharge varies

from perhaps no flow in droughts through to catastrophic

tlood events: so which discharge(s) define the channel's

characteristics? Woiman and Leopold (1957) showed that in

the USA, bankfull flows oecur with the surprising regularity of

about once every I 2 years aeross a diverse range of rivers,

something that would be an extraordinary coincidence if

bankfull flows did not in themselves play a large part in

determining channel dimensions. It has also been shown that

with increasing at-a-station discharge, flow velocity tends to

increase until near bankfull llow conditions and then stabilizes

at higher discharges because ofa marked increase in roughness

near the bank crests and over the floodplains. In other words.

most flows beyond bankfull are not notably more effective in

altering the ehannel and transporting sediment than is bankfull

flow. Furthermore, while in some cases exceptional floods may

undertake signilicant work in the form of sediment transport

and channel reconstruction, they are sufficiently rare that on

an average annual basis, they usually achieve far less than do

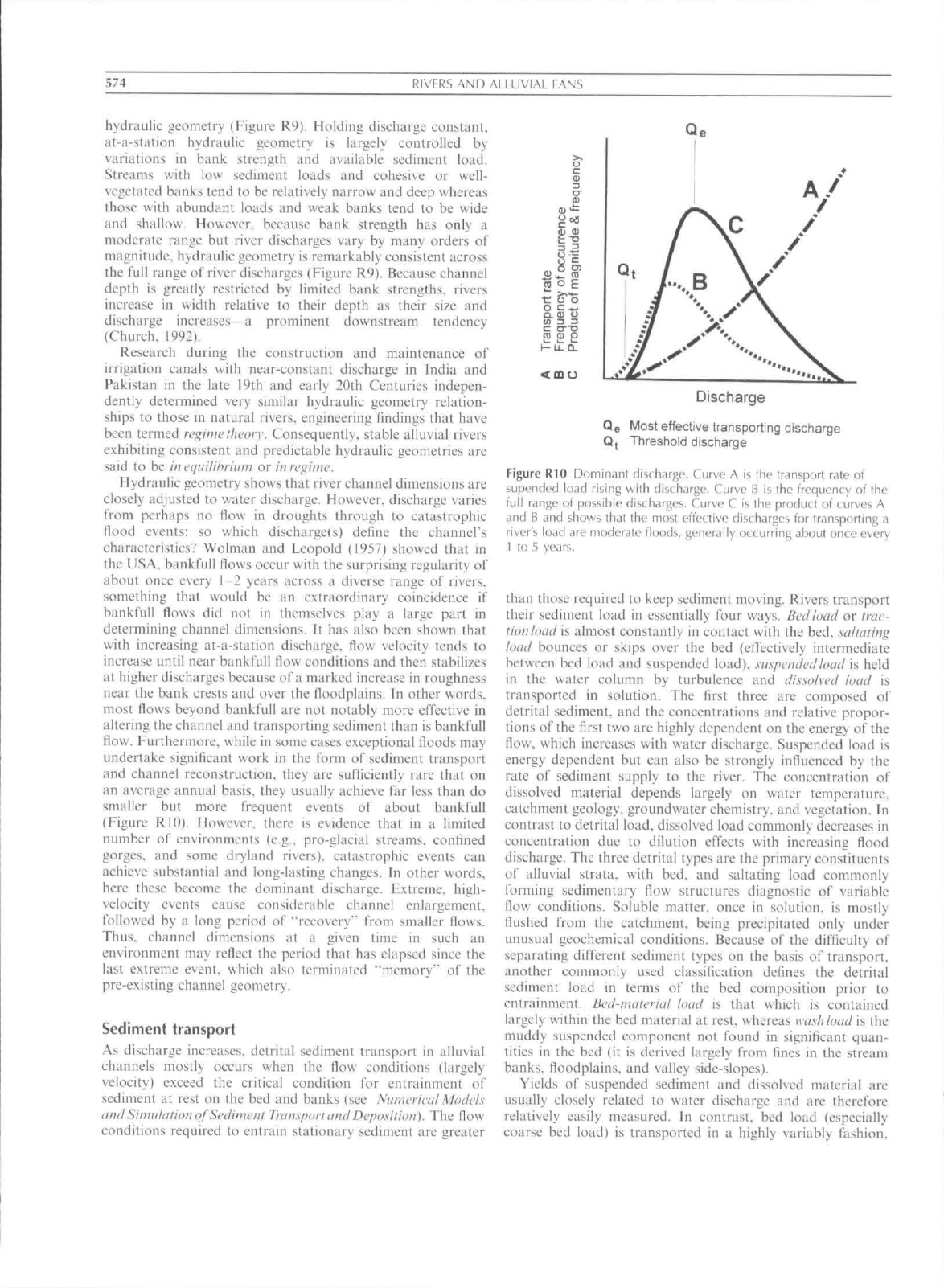

smaller but more frequent events of about bankfull

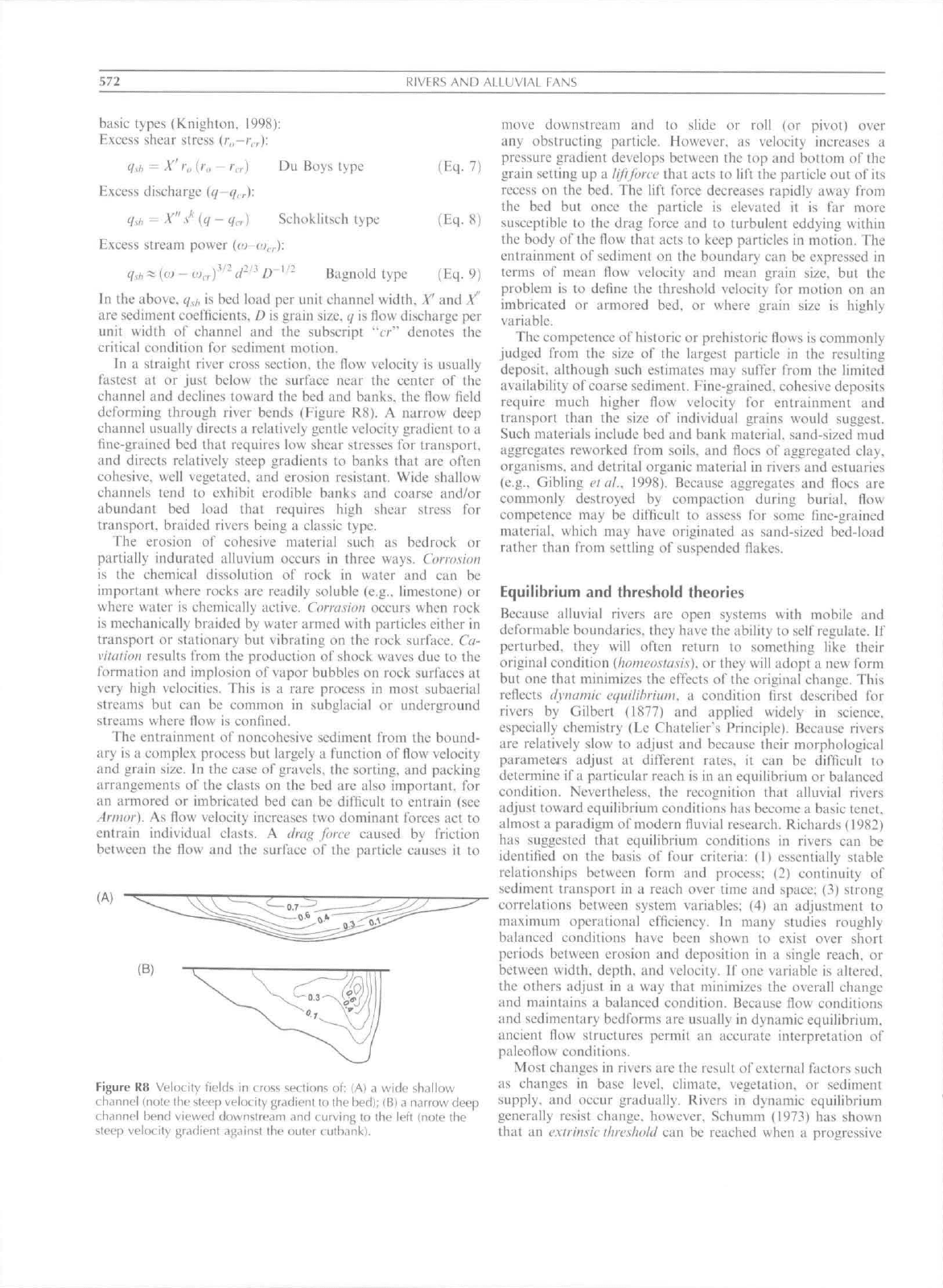

(Figure RIO). However, there is evidence thai in a limited

number of environments

(e.g..

pro-glacial streams, confined

gorges, and some dryland rivers), catastrophic events ean

achieve substantial and long-lasting changes. In other words,

here these become the dominant diseharge. Extreme, high-

veloeity events cause eonsiderable channel enlargement,

followed by a long period of "recovery" from smaller flows.

Thus, channel dimensions at a given time in such an

environment may reflect the period that has elapsed since the

last extreme event, whieh also terminated '"memory" of the

pre-existing channel geometry.

Sediment transport

As discharge increases, detrital sediment transport in alluvial

channels mostly occurs when the flow conditions (iargeiy

velocity) exceed the critical condition for entrainment of

sediment at rest on the bed and banks (see Numcrleal Models

andSimulalionof Sedimcnl TrunsporlandDepo.silion). The flow

conditions required to entrain stationary sediment are greater

t "O

3 .3

-.,

O CD

ro

o

E

t o o

O

C .„

D.

dJ

O

(0

=1

=)

c

crX)

m

IU £

H ul D.

Discharge

Qe Most effective transporting discharge

Qt Threshold discharge

Figure

RIO

Dominant

discharge.

Curve

A is the

Iransport rate

of

supenrleH load rising with

discharge-

Curve B

is the

frequency

of (he

tuli range

of

possible

discharges.

Curve

C is the

product

of

curves

A

and

B and

shows thai

the

most effective discharges

tor

transporting

a

river's load

are

moderate

floods,

generally occurring aboul once every

1

to 5

years.

than those required to keep sediment moving. Rivers transport

their sediment load in essentially four ways.

Bed

load or uac-

rionload']^ almost constantly in contact with the bed. saluiiing

load bounces or skips over the bed (effeetively intermediate

between bed load and suspended load),

.suspendedload

is held

in the water column by turbulence and dissolved load is

transported in solution. The first three are composed of

detrital sediment, and the eoncentrations and relative propor-

tions of the first two are highly dependent on the energy of the

flow, whieh inereases with water diseharge. Suspended load is

energy dependent but can also be strongly influeneed by the

rate of sediment supply to the river. The concentration of

dissolved material depends largely on water temperature,

catchment geology, groundwater chemistry, and vegetation. In

contrast to detrital

load,

dissolved load commonly decreases in

concentration due to dilution elTects with increasing flood

discharge. The three detrital types are the primary constituents

of alluvial strata, with bed. and saltating load commonly

forming sedimentary flow structures diagnostic of variable

flow conditions. Soluble matter, once in solution, is mostly

flushed from the catchment, being precipitated only under

unusual geochemical conditions. Because of the difficulty of

separating dilTerent sediment types on the basis of transport,

another eommonly used classification defines the detrital

sediment load in terms of the bed composition prior to

entrainment. Bed-uunerial load is that which is contained

largely within the bed material at rest, whereas

xva.shload

is the

muddy suspended component not found in significant quan-

tities in the bed (it is derived largely t>oni fines in the stream

banks, floodplains, and valley side-slopes).

Yields of suspended sediment and dissolved material are

usually closely related to water discharge and are therefore

relatively easily measured. In contrast, bed load (especially

coarse bed load) is transported in a highly variably t^ashion.