Mattingly J.D., Heiser W.H., Pratt D.T. Aircraft Engine Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

356 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

and mass (molecules) may be transported laterally as well. If the two streams have

different molecular identities, the shear layer is also a mixing layer. By analogy

with the definition of boundary layer thickness, the mixing layer thickness

~m

is

defined as the region within which the mole fractions of mixant gases differ by 1%

or more from their respective values in the unmixed streams.

The velocity ratio r =

U2/U1

and the velocity difference AU = U1 - U2 are

related to the mean convective velocity U¢ = ( U1 -+- U2)/2 by

1-r

For very small A U the shear layer may be laminar and time steady. As the

velocity difference A U between the two streams is increased, the laminar shear

layer becomes unstable, and large vortices are periodically formed between the

two streams, just as in the case for round jets, as shown schematically in Fig. 9.18.

The cross-hatched area shown in the third vortex structure in Fig. 9.18 represents

the fully micromixed region. Of course, molecular diffusion occurs continuously at

the fuel-air interface immediately after the splitter plate, and the fully micromixed

end state is simply the cumulative result of interfacial diffusion.

The time-mean growth rate of a turbulent shear layer is given approximately

by 19

~ 3B 2 1 - r (9.53)

---

X

where ~ is the local shear layer width at a distance x downstream of the splitter

plate, and where B is the ratio of the Prandtl mixing length ~m to the shear layer

width, B =

f.m/&

The ratio B is an empirical constant and can only be determined

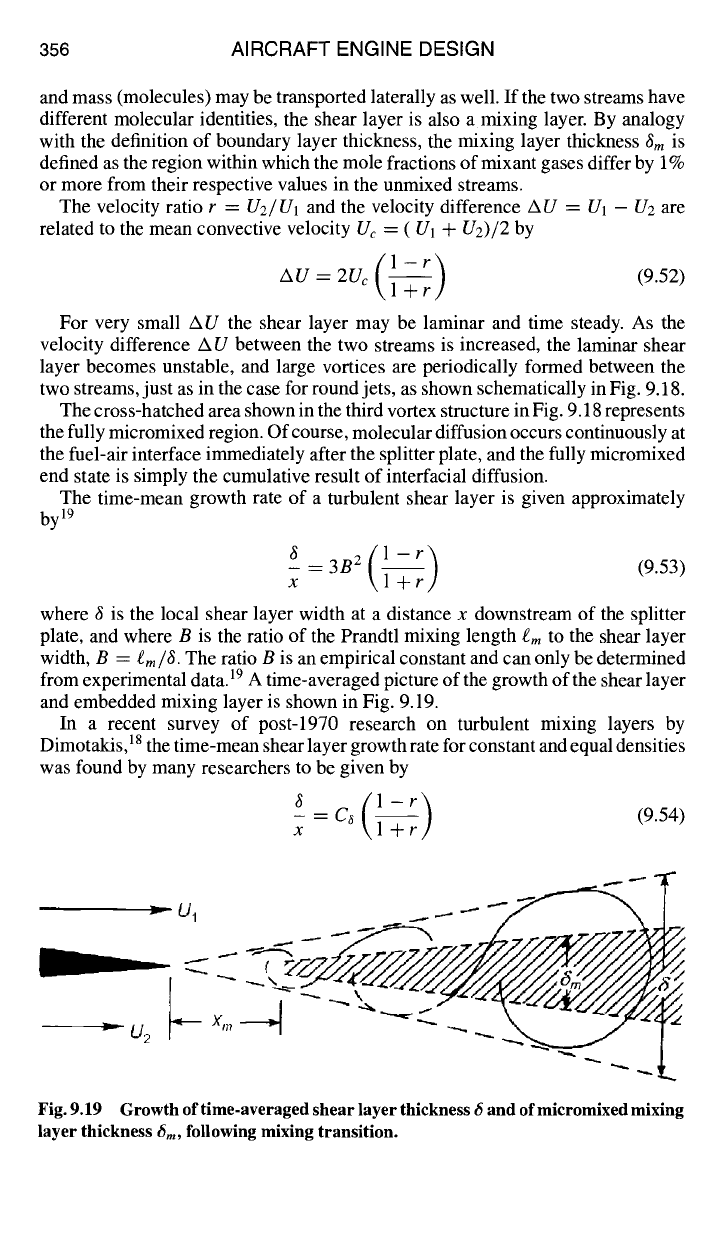

from experimental data. 19 A time-averaged picture of the growth of the shear layer

and embedded mixing layer is shown in Fig. 9.19.

In a recent survey of post-1970 research on turbulent mixing layers by

Dimotakis, 18 the time-mean shear layer growth rate for constant and equal densities

was found by many researchers to be given by

1-r

X

/

"3

/

Fig. 9.19 Growth of time-averaged shear layer thickness 6 and ofmicromixed mixing

layer thickness

6m,

following mixing transition.

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS 357

where C~ was reported as varying from 0.25 to 0.45. Note that Eqs. (9.54) and (9.53)

are of the same form and differ only in the representation of the proportionality

constant.

When the mass densities in the two streams are different, the convective velocity

Uc

is given by 18

U 1 -~- Sl/2U2

Uc -- 1 + s72

(9.55)

where s =

P2/Pl.

The corresponding growth rate of the shear layer is also consid-

erably more complex than Eq. (9.54):

C,s( 1-r ) (~) { (1--s1/2)/(l+slh) }

x = 1 + s'/2r

1 - 1 + 1.29(1 +

r)/(1 - r)

(9.56)

Note that Eq. (9.56) reduces to Eq. (9.54) when s = 1.

By inspection of Fig. 9.18, it is apparent that, at any axial station, micromixing

(indicated by dashed lines) is not complete throughout the shear layer. In fact,

for the first one or two vortices sketched in Fig. 9.18, it may be seen that com-

paratively little micromixing has yet occurred. The distance downstream of the

splitter plate at which significant amount of mixed fluid is first present is called the

mixing transition point. The mixing transition occurs approximately at the point

where

(UI -- U2)~ ~

10 (9.57)

P

where v is a representative average value of the molecular kinematic viscosity

within the shear layer. Following the mixing transition, the time-averaged mi-

cromixing layer is observed to grow approximately as a constant fraction of the

shear layer,

~m

--

~ 0.49 (9.58)

as illustrated in Fig. 9.19.

The composition of the gases within the mixing layer is characterized by the

volumetric entrainment ratio Ev, defined as the volume ratio of high-speed fluid

to low-speed fluid entrained within each vortex structure, that is, "wrapped up"

into each vortex or "jelly-roll" structure as shown in Fig. 9.18. The volumetric

entrainment ratio is observed to depend on both the density ratio and velocity

ratio ~s as

1-r

The corresponding mass-basis and mole-basis entrainment ratios

Em and En are

given by

Em=--Ev

and E.=

M2Em

(9.60)

s M~

358 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

where M1 and M2 are the mean or apparent molecular weights of the gases in

streams 1 and 2, respectively.

TM

9.1.5 Total Pressure Loss

The main burner or combustor is the engine component immediately down-

stream of the high-pressure compressor. For reasons to be shown presently, the

main burner requires an inlet velocity which is much lower than that leaving

the high-pressure compressor, so that the flow velocity must be greatly reduced

between these two components. As the required flow diffuser inserted into the

flowpath is a passive device, adding neither mechanical nor thermal energy to the

flow, it is not clear from a strictly logical point of view where design responsibility

for this component should lie. Historically, it has been regarded as a part of the

main burner, and so it is included here.

In this section it will first be shown how to estimate the main burner diffuser total

pressure loss. Next, the principal source of total pressure loss in the main burner

liner (see Fig. 9.1) namely, stirring and mixing with jets, will be considered. Finally,

the total pressure loss in the afterburner (see Fig. 9.2) will be analyzed.

A number of assumptions will be made in common for all of the derivations

to follow. They are as follows: 1) flow is quasi-one dimensional, 2) mass density

varies with temperature, but not with pressure, n 3) combustion in the main burner

is at constant pressure, and 4) the mass flow rate of fuel is neglected compared to

that of air.

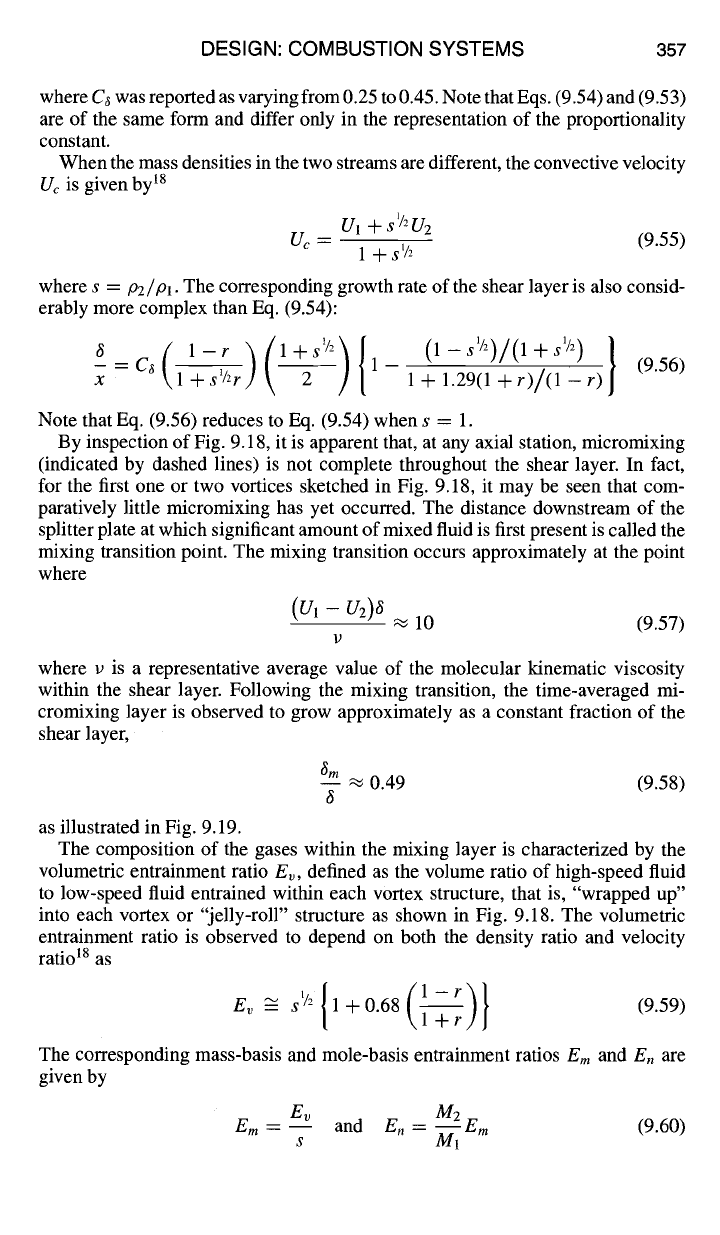

9. 1.5.1 Flat-wall diffuser.

Although the purpose of a flow diffuser is to

reduce axial velocity in order to gain static pressure, this must be accomplished

in a very short axial distance and with a minimal loss of total pressure. As with

the diffusing flow in compressor blade passages, this is not easily accomplished

without flow separation. The geometry and nomenclature of a generic fiat wall

diffuser with flow-straightening section are shown in Fig. 9.20. The entry and exit

stations of Fig. 9.20 correspond to compressor outlet, station 3.1, and burner inlet,

station 3.2, respectively, in Fig. 9.1. Typically, an area ratio

AR = A2/A1

of 3 to 5

is required to diffuse the flow, although an area ratio as great as 10 or even 20 may

be required for some engine designs. A "tailpipe" of length

La

can be added for

improved performance.

\

L tan8

+ 2/_/--~

H 2

Fig. 9.20 Geometry of a flat-wall diffuser with tailpipe. 2°m

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS 359

Strictly speaking, both the main burner and afterbumer diffusers are annular

diffusers, rather than the planar diffuser pictured in Fig. 9.20. Because an annular

flow passage has inner and outer radii

ri and ro,

respectively, the geometrical

variables that define the shape of an annular (quasi-flat-wall) diffuser are given by

AR -- A2 -- H2rm2 -- 1 + 2rmz L tanO

A1 H1 rml rml HI

or

L t/rml"~ (AR-

1)

H-~ =

I Ikrm21

2tanO

(9.61)

where H is the radial height H =

(ro - ri) and rm

is the mean radius, r,, --

(ro +ri)/2.

Note that when the inlet and exit mean radii are equal Eq. (9.61) reduces to the

geometrical relationship for a planar flat-wall diffuser given on Fig. 9.20.

There are a number of measures used to characterize the performance of a

diffuser. The pressure recovery coefficient Ce is defined by 2°'21

P2 - P1

C p _4_

(9.62)

ql

In the case of isentropic flow, that is, flow with neither wall friction nor flow

separation, and with the assumptions listed at the beginning of this section, con-

servation of mass leads immediately to the ideal pressure recovery coefficient

Cpid:

(/°2 --

el)ise n ql - qZisen 1

Cpi d

----" --

-- 1 - -- (9.63)

ql ql AR 2

The ratio of actual-to-ideal pressure recovery is a logical measure of diffuser

performance and is called the diffuser effectiveness or diffusion efficiency r/D,

Ce

OD -- (9.64)

Cpid

It is interesting to note that ~/D defined by Eq. (9.64) is identical to the isentropic

diffuser efficiency 0D defined by the ratio of ideal-to-actual enthalpy change, 22

h2s - hi

OD ---- (9.65)

h2 - hi

The total pressure loss coefficient is defined by

( ~ ( 1 )

APt _ Ptl-Pt2 =Cmd-Cp

= 1-~-~ (1--~n) (9.66)

\ ql ID ql

and the related total pressure ratio ~o is

t)t2 (APt/ql)D

(1 -

1/AR2)(1 - riD )

7"/" 0 ~" --

1 -- 1 - (9.67)

Ptl 1 + 2/vM 2 1 + 2/vM21

All of the preceding figures of merit are useful, depending on the perspective

or interest of the designer. If the primary design goal of the diffuser is maximum

360 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

20

Fig. 9.21

100 °

, ,

,,

Jet flow (Dump)

7o

d ~.~_~~~ steady~~stall \~

40

/~tall "" -,...

20 ~1~ -- "" -- Maximum

10 °

7

4

2

,o

2 4 7 10 20 40 100

L/H I

Operating regimes

of a flat-wall diffuser without tailpipe. 2°'21

static pressure recovery, then both

Cp

and OD are of interest. If a design goal is

to minimize adiabatic irreversibility (entropy rise or, equivalently, total pressure

loss), then

rlD, (APt /

qr)D,

and

no are

all of interest.

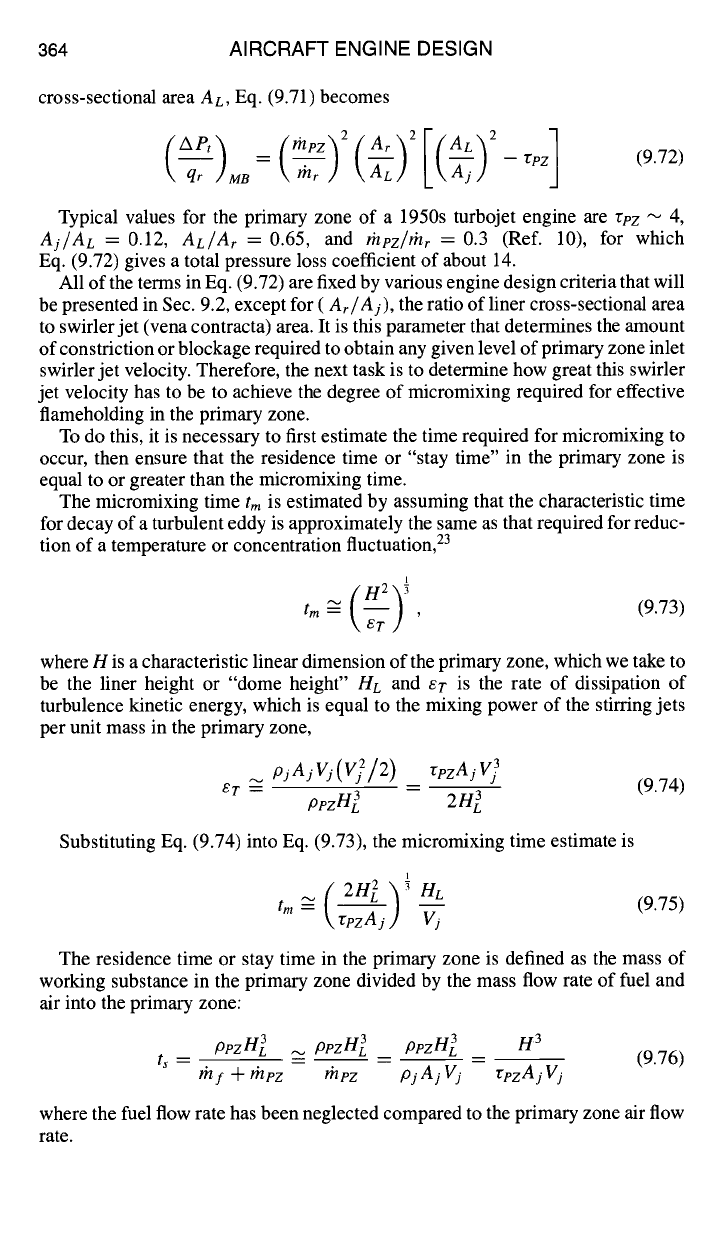

The operating regimes of a flat-wall diffuser without tailpipe are shown in

Figs. 9.21 and 9.22. It can be seen from Fig. 9.21 that the possible operating

regimes for a flat-wall diffuser are a veritable snake's nest of flow phenomena.

In the "no stall" region below curve

a-a,

flow remains attached to the walls, but

performance is suboptimal because of excessive friction resulting from very long

walls. The best performance occurs in the "some stall" region, bounded by

a-a

and

b-b,

even though the flow in this regime is in mild transitory stall, that is,

alternately separating and reattaching to the walls. In the "large transitory stall"

region bounded by

b-b

and

c-c,

the flow is oscillating so vigorously from wall to

wall that the flow patterns are highly unstable, and total pressure loss is conse-

quently excessive. In the "bistable steady stall" region bounded by

c-c

and

d-d,

the flow separates completely from one wall and attaches to the opposite wall.

Finally, above

d-d,

the flow is separated from both walls and enters the diffuser

as a core jet flow, which eventually reattaches to the downstream walls, if there

is sufficient axial length to do so, as for example a tailpipe of some length

Ld

as

shown in Fig. 9.20. When operating in the jet flow regime, the diffuser is called a

"dump" diffuser.

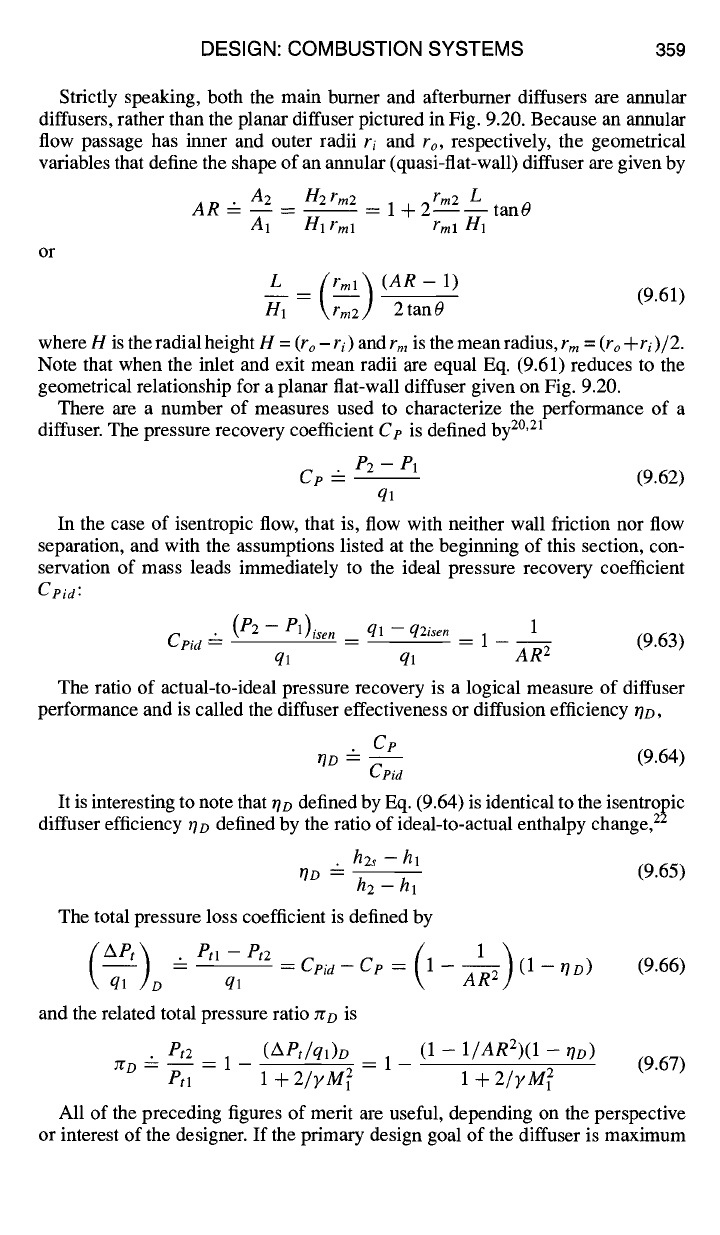

There is a "sweet spot" in the operating map, represented by the "bullseye"

in Figs. 9.21 and 9.22. For this particular geometry, namely, 20 --~ 9deg and

L/H1 "~

18, both the maximum achievable

Cp

and a near-maximum diffusion

efficiency r/D are realized. This optimal value of diffusion efficiency can be

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS 361

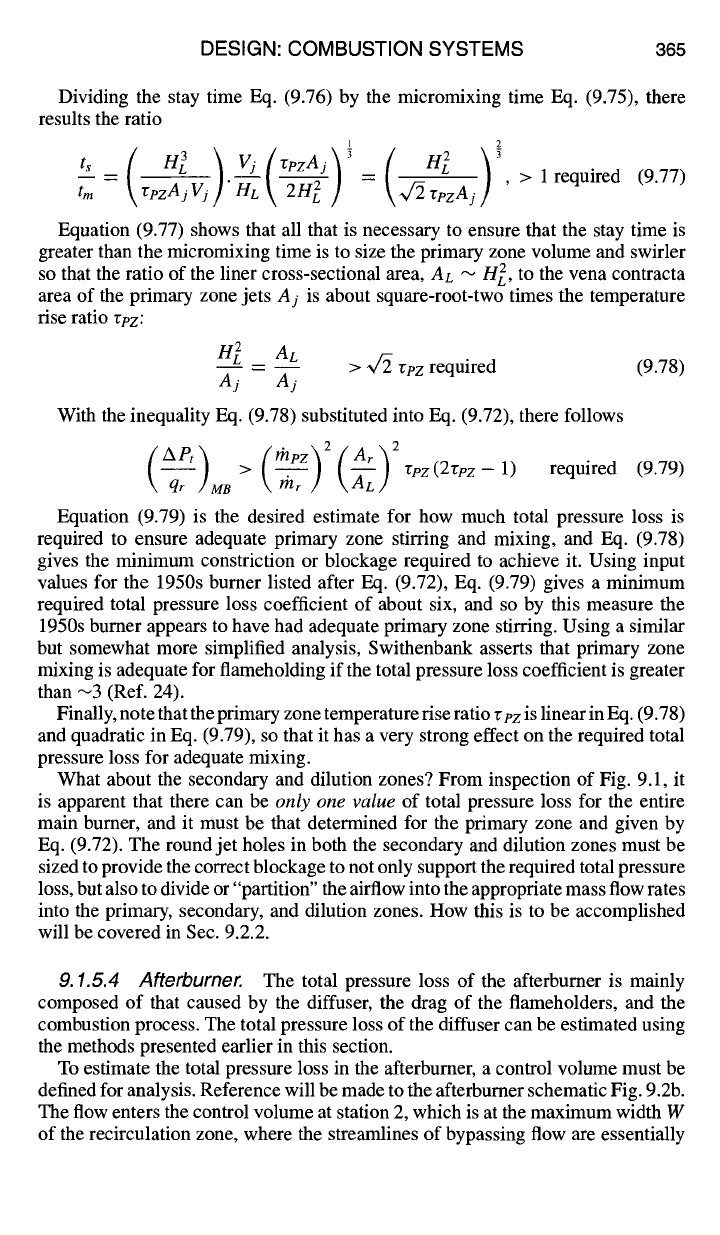

10

8-

6-

A2

5-

4-

A1

"3=

2.5,

2-

1.4

I I I I I I I I I I I I i ,I ,

d c

/

J

// I /

Jet flow (dump) ~" i r]

-

70% 875% b

Bistable steady . z" /~ f .~Z-.Y" ...--~ / / /

Large ~rans~ory .~'/-j" _..~-'-~;, ~ /- /"

Some stall ~ ~ ~ ~ " ~20"= 9~ //87.5°/°

.o sty".

....

% /

.....

I i [ I [ | [I I I I I 1 I i |

1.5 2 3 4 5 6 8 10 15 20 30 40

L/H 1

Fig. 9.22 Contours of diffuser effectiveness on performance map of flat-wall diffuser

without tailpipe and with thin inlet boundary layers,

Bt ~

0.018.

represented approximately by an empirical relation, 2°

/7D9 ~ 0.965 -- 2.72Bt 0.01

<

B t

< 0.12 (9.68)

where Bt is the thickness of the turbulent boundary layer at diffuser entry. Note on

Fig. 9.22 that the diffuser efficiency ~o is very nearly constant with varying

L/H1

for a constant wall angle 20 = 9 deg for values of

L/H1

between "-- 4 and --- 20.

The corresponding range of area ratios, determined from the geometrical relations

of Eq. (9.61) and shown on Fig. 9.20, is 1.5 <

AR < 4.

Combining Eqs. (9.63), (9.66), and (9.68), the total pressure loss coefficient for

a fiat-wall diffuser with divergence angle 20 = 9 deg can be shown to be

= Cpid(l --

/'/D9 o) = --

(1

-- 0D9O), 1.5 <

AR

< 4

(9.69)

\ ql /D9 o

However, there are problems. The "sweet spot" diffuser length

L/H1

~ 18 is

unacceptable because it excessively increases the length of the engine core. In

addition, the sweet spot area ratio

AR

= 3.83 is not likely to fit any specific engine

design requirement, and area ratios AR greater than about four push the operating

point into the region of large transitory stall, between

b-b

and

c-c

on Figs. 9.21

and 9.22. Finally, because the flow exiting the high-pressure compressor has been

"sliced and diced" by the last row of rotor blades and straightening vanes, the

boundary layers entering the diffuser are very thick, so that the optimal diffusion

efficiency given by Eq. (9.68) may be as low as --~ 0.64. This is so low that

consideration must be given to the alternative of abandoning the 9-deg angle,

straight-wall diffuser design entirely, and simply "dumping" the flow into the

required area at combustor entry, station 3.2.

362 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

9.1.5.2 Dump diffuser. At first glance, it may seem that the dump diffuser,

operating in the "jet flow" region above line d-d in Figs. 9.21 and 9.22, is the

worst possible case for flow diffusion, but, in fact, the bistable stall and large

transitory stall regions bounded by b-b and d-d in Figs. 9.21 and 9.22 are much

worse. 2°,21 Worst of all, in the large transitory stall region the flow separates and

then momentarily reattaches to only one of the downstream walls. This in turn

causes another, subsequent sudden expansion as the bifurcated flow tries to reattach

and fill the duct. The separated flow acts as a bistable oscillator, jumping from

wall to wall in a periodic Coanda effect, presenting randomly varying, nonuniform

velocity profiles to downstream components and causing an excessive loss of total

pressure, which can be 10-40% greater than a dump diffuser! Thus, a dump diffuser

is the "best worst" case for a flat-wall diffuser.

Consider the classic case of head loss or total pressure loss caused by a sudden

expansion in a duct. 21 Figure 9.20, with 20 = 180 deg and La ~ H2, is the control

volume for this analysis. (The tailpipe length La has to be sufficiently long for

the jet core flow at entry to reattach to both walls.) By applying the equations

of conservation of mass and linear momentum to this control volume, together

with the assumptions listed in the introduction to this section, the reader may (and

should) verify that the pressure recovery coefficient, total pressure loss coefficient,

and diffuser efficiency for the dump diffuser are given by

(AR-I

F ]

(1),

_-,-

ana

[CP]d,mp = 2 I~ AR 2 ]' k ql Jd,mp ~ '

2

[qD]dump =

1 + AR (9.70)

For the "sweet spot" diffuser area ratio AR = 3.83, Eq. (9.70c) predicts a dump

diffuser efficiency of only 0.414, which is considerably less than the absolutely

best value of qD = 0.91 obtainable by a thin-boundary layer, 2 0 = 9 deg flat-wall

diffuser of area ratio AR = 3.83 and length-to-entry height ratio L/H1 = 18. Ways

to overcome this perplexing problem will be presented in Sec. 9.2.3.

9.1.5.3 Main burner. In the early day of turbojet engine development, the

total pressure loss of the combustor was regarded as just another parasitic loss, in

addition to those of the diffuser, compressor and turbine, all of which reduced the

marginal engine performance achievable at the time. Consequently, main burner

designers were under great pressure to minimize total pressure loss, or at least

to justify the excessive amounts they claimed were necessary to achieve ade-

quate combustion stability and efficiency. As engine designs evolved, increasing

compression ratios and turbine inlet temperatures created a demand for increased

compressor bleed airflow for turbine blade cooling. Moreover, because the bleed

air itself was becoming increasingly hot, even greater flow rates were needed

to adequately protect the turbine blades. Consequently, the main burner is today

viewed not only as the source of thermal energy required by the propulsion cycle,

but also as a necessary flow constriction or circuit resistance, which must provide

adequate flow area blockage to maintain the required static pressure drop between

compressor bleed outlet and turbine inlet. This is especially critical if the turbine

first stage stator vanes depend on film cooling to protect their leading edges. If

~>~

~.=~

~ga

~'~ ~

~ .

~N

i

~

I. ~.

I

II

N

I I

b~

I

I t°l

".-.1

0

o'0

t~

~>

II

+

I

+

II

I

~.~X.~.~=~ ~.~ ~. ~ --~ ~ ~ o~ = =~ = ~q ~. ~ = ~ .~.~

o-o=~ ~

•

~.~o~=~.~ ...~

o~ ~- ~-~~ ~ ~: ~ .~ ..... o~

ii~ ~ ~ "'~ ~

o ~ ~'=.n'= ~ -~

- ~ ~,,..=o~ ~ ~ =,, ~ o ~

0 ~'0 0" ~'0

~" ~] ~

~. ~ ~ ~" ~ C~ ~ . ~ ~ "" 0 ~ 0 ~'"

~I ~ ~ 0 ~. ~ ' ~

"

' 0

~o" I ~1 ~

~-~ ~0 ~ i::r0~ In ~ ¢~ ~ 0 ~'

~ .~ ~" - ~

.

"0 0 ~ ~ ~ I~

o

ITI

¢aO

0

z

0

0

DD

C

O0

0

Z

O0

-<

O0

--I

m

oo

¢...0

O)

¢aO

364 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

cross-sectional area AL, Eq. (9.71) becomes

qr ]MB \

lhr / \AL/ L\'-~j] -- rpz

(9.72)

Typical values for the primary zone of a 1950s turbojet engine are fez ~ 4,

Aj/AL

= 0.12,

AL/Ar

= 0.65, and

rhpz/rhr

= 0.3 (Ref. 10), for which

Eq. (9.72) gives a total pressure loss coefficient of about 14.

All of the terms in Eq. (9.72) are fixed by various engine design criteria that will

be presented in Sec. 9.2, except for (Ar/Aj), the ratio of liner cross-sectional area

to swifter jet (vena contracta) area. It is this parameter that determines the amount

of constriction or blockage required to obtain any given level of primary zone inlet

swirler jet velocity. Therefore, the next task is to determine how great this swirler

jet velocity has to be to achieve the degree of micromixing required for effective

flameholding in the primary zone.

To do this, it is necessary to first estimate the time required for micromixing to

occur, then ensure that the residence time or "stay time" in the primary zone is

equal to or greater than the micromixing time.

The micromixing time

tm

is estimated by assuming that the characteristic time

for decay of a turbulent eddy is approximately the same as that required for reduc-

tion of a temperature or concentration fluctuation, 23

2 !

tm ~

(9.73)

where H is a characteristic linear dimension of the primary zone, which we take to

be the liner height or "dome height" Hc and er is the rate of dissipation of

turbulence kinetic energy, which is equal to the mixing power of the stirring jets

per unit mass in the primary zone,

pjAjVj(V2/2) rpzAjV]

er = ppzH~ 2H 3

(9.74)

Substituting Eq. (9.74) into Eq. (9.73), the micromixing time estimate is

1

= --

tm \ ~pzAj /I

(9.75)

The residence time or stay time in the primary zone is defined as the mass of

working substance in the primary zone divided by the mass flow rate of fuel and

air into the primary zone:

- . "~ -- -- (9.76)

mf -+-rhpz rhpz pjAjVj rpzAjVj

where the fuel flow rate has been neglected compared to the primary zone air flow

rate.

It)

r/?

LLI

>-

Of)

Z

0

h-

Or)

rn

0

0

CO

U)

ILl

o

t~

~ 0

e~

A

,

I1

N ~

~1 ~

I1

~.~

~ "~_~

~ N

-~c,~

0 0

*~ "~,~ 0"~

~ .~ ~

.,-~

~N

~-~

o~ ¢~

"~: ~ ~ "~ o

~'~

~o

~.~

N

#

A

Ox

t~

N

N

C~

~-~ A

©

~c~ ~ i:i ~ ~ N ~ ,'~ ~

• ~ ~ ~ ,~ ~ ~

~..~ ~.~ ~ ~,.~ o~ ~ ~ ~ ~ =~

= ~ ~ 5 ~_ ~o ~ ~

~ ~.~ ~.~ ~ .~ o ~ ¢~ ~: ~ ~ ~::~ I::l ~,

~ ~'~ E ~ ~ "N~O ~,~

~,_--= ~''~

o 0~.---,-0 ~ c~,~ .~ ~ ~ ~= •

~ ~- o~ S ~ ~R.~

~ 0 r~ ~ ,,-~ ~ I:~"~ 0

~'~.~-~.,~ r~,.o ~ c~ ~ ~ 0"~...~ ~ 0.~ 0 ~:l ~

c~ or.~

°.- _ o...

o~ ~"o '~ ~

~=--

~ ~ ~ 0 ~: ~:~ ~ .~ Ox ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ o ~ c~ .

,-~ 0 ,-~ "~ "~ ~ ~ O~ ~ ,~ ' t~ 0 •

•

¢~ "~

" ~ ~ ~,-~ ~ ~ ~ 09

~-~ ~ ~ OX ~.-~ ~l c~ ~t-,C:l ~,.1= '~ ~=:~ ~ ~ :,.~ ~.~

"~ © ,~,'~ © ~"~ 0 "~ ~'> 0 ~

@ o ~ ,~ :~ ~ .~ o~ -~ ~ • o ~'~ >

0"~.~ ~ © ~ ~ .,.~ .~ 0 "~ ~

~.. ~ ~',~,~

~ ~ .a t~'No.~

• 0