Mattingly J.D., Heiser W.H., Pratt D.T. Aircraft Engine Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

326 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

Of the three principal components of a gas turbine engine--the compressor,

combustor, and turbine--the combustor is usually perceived to be the least under-

stood, perhaps even a "black art," component, and the same can be said of the fourth

component of some engines, the afterburner. This is because most propulsion-

oriented students and engineers have not had the opportunity to study all of the

engineering subjects that are required to understand, analyze, and design combus-

tors and afterburners.

Because there are no rotating parts in the combustor and afterburner to transfer

external work to or from the gas stream, the only work and power relations required

are those which determine how much mechanical power must be dissipated in order

to cause the vigorous mixing required by the combustion process. Consequently,

students who are familiar with the analysis and design of rotating machinery will

be reasonably comfortable dealing with the processes of velocity diffusion, liner

wall cooling, jet mixing, total pressure loss, and air partitioning in the combustor.

However, in order to understand the equally essential processes of heat re-

lease, flameholding, and pollutant formation and control, students must have some

background in three additional engineering subjects, namely, 1) chemical thermo-

dynamics of ideal gases, 2) gas-phase chemical kinetics, and 3) chemical reactor

theory. Essential concepts from these three topics are presented in summary form

in this chapter. Supporting design and analysis computer programs are included in

AEDsys, the suite of software tools that accompanies this textbook.

Unlike the study of rotating machinery, there are surprisingly few resources in

the open literature that deal with the design of main burners and afterburners in

airbreathing propulsion systems. For more in-depth information two recommended

sources are Arthur Lefebvre's

Gas Turbine Combustion 2

for the main burner and

Edward E. Zukoski's "Afterburners. ''3

9.1.1 Combustion Systems Components

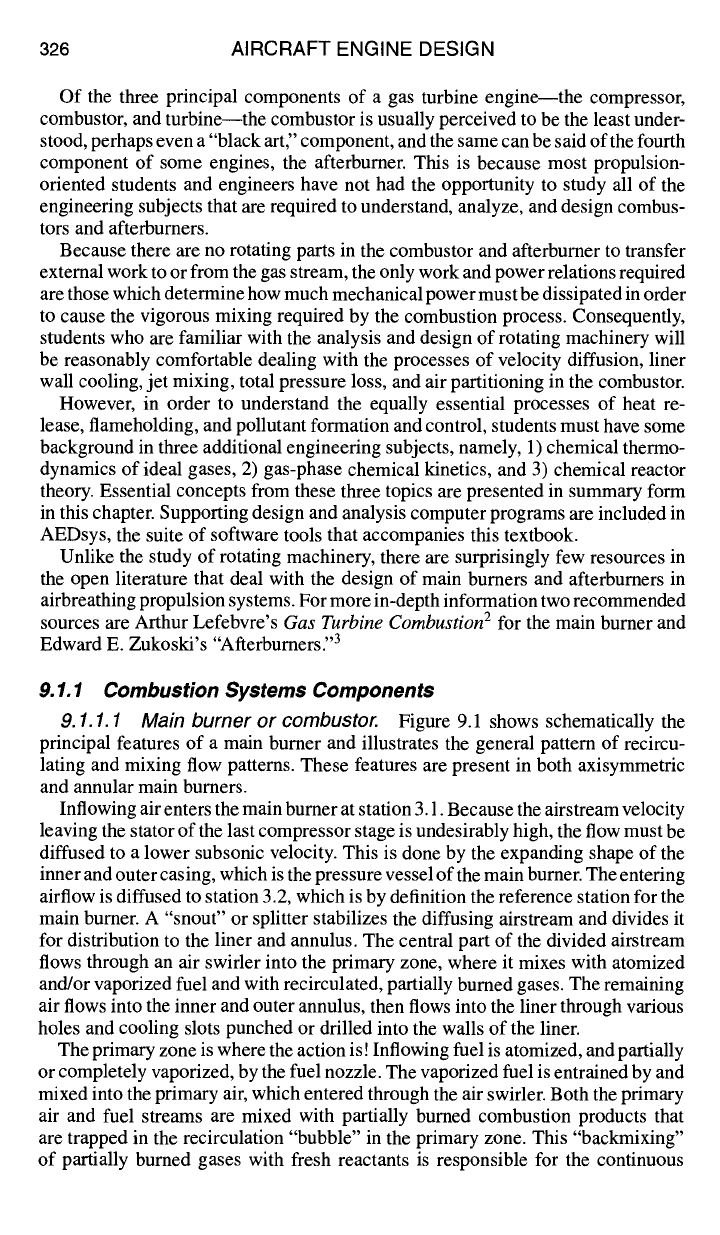

9.1.1.1 Main burner or combustor. Figure 9.1 shows schematically the

principal features of a main burner and illustrates the general pattern of recircu-

lating and mixing flow patterns. These features are present in both axisymmetric

and annular main burners.

Inflowing air enters the main burner at station 3.1. Because the airstream velocity

leaving the stator of the last compressor stage is undesirably high, the flow must be

diffused to a lower subsonic velocity. This is done by the expanding shape of the

inner and outer casing, which is the pressure vessel of the main burner. The entering

airflow is diffused to station 3.2, which is by definition the reference station for the

main burner. A "snout" or splitter stabilizes the diffusing airstream and divides it

for distribution to the liner and annulus. The central part of the divided airstream

flows through an air swirler into the primary zone, where it mixes with atomized

and/or vaporized fuel and with recirculated, partially burned gases. The remaining

air flows into the inner and outer annulus, then flows into the liner through various

holes and cooling slots punched or drilled into the walls of the liner.

The primary zone is where the action is! Inflowing fuel is atomized, and partially

or completely vaporized, by the fuel nozzle. The vaporized fuel is entrained by and

mixed into the primary air, which entered through the air swirler. Both the primary

air and fuel streams are mixed with partially burned combustion products that

are trapped in the recirculation "bubble" in the primary zone. This "backmixing"

of partially burned gases with fresh reactants is responsible for the continuous

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS 327

Outer casing

/

1

Jl

Dilution hole

Transition duct

Air

swider Liner

\Dome

Fuel nozzle ~ ~ /

Cooling slot

10utarinnu'us L,,

.~..,~¢~ Secondary hole

Diffuser ~ Primary zone

I

Secondary or

Intermediate

zone I

J ~.,,

Inner annulus

station 3.1 station 3.2 Inner

casing

a) Principal features

statiJ~n 3.9

I Dilution

zone

station

4

micromixed I~

I I /reaction zone --7 --~ annulus flow

[

dilution

"111

I primary

"~ '/-//-if/J/ ~'~'"

airflow •

\airflow

I I I air flow

/. "

" - - ~ "

-- \~ ', "~"

--

i t....-.=...--= , ~ , recirculati,~,, J \

~1_ fuel flow ( (7low ,~r /' ; ......

I~A

~, \'-

~ , ~

/

linerflow

- \y, >

--.

cooli'n;:irflow ~~( J 1/

b) Flow patterns

Fig. 9.1 Main features and flow patterns of the main burner/combustor: a) Principal

features; b) Flow patterns.

self-ignition process called flameholding, so that an external source of ignition,

such as a spark plug, is not required. (However, an external ignition source is

required for starting the ftameholding process.) Chemical reaction occurs primarily

in the micromixed reaction zone, within which reactants have been mixed to near-

molecular homogeneity.

From the primary zone the mixture of partially mixed, actively burning, and

incompletely burned gases flows downstream into the secondary or intermediate

zone, where they continue to bum towards completion while mixing with inflow-

ing air from the secondary holes. Two processes must occur in parallel in the

secondary/intermediate zone: 1) the primary zone effluent gases must continue to

burn out, and 2) the in-mixing secondary air must "lean out" (reduce the fuel-air

ratio of) the liner gas stream. These two processes must be balanced in such a way

that the temperature rise which would otherwise occur from continued burnout is

offset by a temperature decrease which would otherwise occur as a result of the de-

crease in fuel-air ratio. Consequently, the liner gases flow through the intermediate

328 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

zone at essentially constant temperature, and combustion should be complete when

the liner gas reaches the downstream end of the intermediate zone.

The dilution zone process, by comparison with the complex chemical and phys-

ical processes occuring in the primary and intermediate zones, is a "no-brainer."

All that is required of the dilution zone is that any remaining annulus airflow be

dumped through the dilution holes into the liner hot gas stream, with just sufficient

stirring to avoid hot spots forming on the first-stage high-pressure turbine stators

(nozzles).

After the hot gases exit the combustor liner at station 3.9, they are accelerated

through a converging transition duct until they are choked at the throat of the first

stage high-pressure turbine nozzles downstream of station 4.

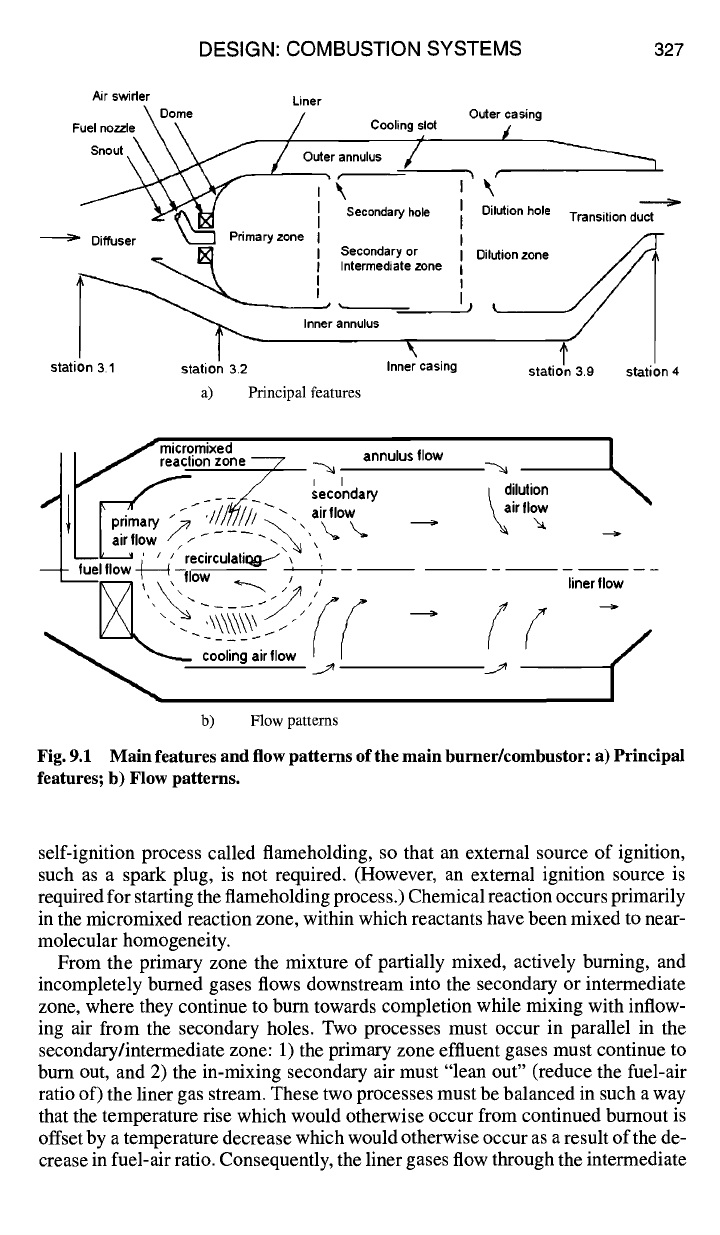

9.1.1.2 Afterburner or augmenter.

Figure 9.2a shows schematically the

principal features of an afterburner, and Fig. 9.2b illustrates the general pattern of

recirculating and mixing flow patterns. The geometry in Fig. 9.2a is axisymmetric

about the engine axis, but Fig. 9.2b is planar.

As shown in Fig. 9.2a, the core gas and bypass air enter the mixer at station 6

and station 16, respectively. The core gas is composed of combustion products.

Although the core gases have given up a considerable amount of thermal energy to

work extraction in the turbine, they still contain a considerable amount of thermal

energy and excess oxygen. Mixing the bypass air with the core gas increases the

tool fraction of oxygen available for reburning, and the hotter core gas warms up

the cooler bypass air as well. The two gas streams are mixed adiabatically and

slightly diffused by station 6A.

While the (core gas + bypass air) mixture is being slowed in the diffuser, fuel

is injected and atomized by the spray rings. The flow rate of fuel is designed to

produce the highest possible temperature at the afterburner exit. By the time the

(fuel ÷ core gas ÷ bypass air) mixture enters the afterburner flameholding region

at station 6.1, it is well-mixed to near-molecular level, so that combustion can take

place.

As shown in Fig. 9.2b, after the combustible gas mixture passes over the down-

stream edge of the vee-gutter flame holders, it then entrains fully burned, hot

combustion products from the recirculation zone in a shear-driven mixing layer.

At some point sufficiently far downstream, a standing flame front is established.

Just downstream of the standing flame front, the shear-driven mixing layer disen-

trains a portion of the burning gases. The disentrained gases then reverse direction

and flow upstream inside the bubble of the recirculation zone, where there is suf-

ficient residence time for them to burn to near completion. The remaining, outer

portion of the burning gases behind the standing flame front propagates a turbulent

flame front outward through the bypassing gas stream.

As the flame front propagates outward, the flow into which it is propagating is

closing in behind the vee-gutter wake, which initially draws the flame front inward

and away from the walls, following which its outward progress continues. As a

result, it is often the case that the outward-propagating turbulent flame front fails

to reach the walls before exiting the afterburner at station 7. When this happens,

a visible, burning external plume extends well downstream from the exit of the

thrust nozzle.

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS 329

bypass air

core gas

station 6

i

Mixer

O

Diffuser

0

Spray ring

After burner casing

Cooling and screech line~

<

Variable-area exit nozzle

Flameholder

station 16 station 6A

1 I

station 6.1 station 7

a) Principal features

n

U~.~_ / ~ mixing l~=r~~~ ~ ~.

.~__~I- / ~.~S-~'~"~~ front ~~

_~ • ® --~

H

Fig. 9.2

b) Flow patterns in the vicinity of a vee-gutter flameholder.

b) Flow patterns in the vicinity of a vee-gutter flameholder

Principal features and flow patterns of the afterburner: a) Principal features;

330 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

At first glance the mechanism of flameholding in the afterburner appears to be

very similar to that of the main burner (Fig. 9.1). However, there are subtle but

important differences between the two. In the main burner primary zone the recir-

culation bubble is fueled from the inside and is confined by the combustor dome

and liner walls so that all primary zone combustion is forced to take place within the

confines of the recirculation bubble. Consequently, there is no discernable flame

front, and spatially homogeneous combustion occurs within the micromixed re-

action zone. In the afterburner, however, the recirculation zone is fueled from the

outside, so that a discrete, standing turbulent flame front is established in the shear-

driven mixing layer at the outer edge of the recirculation bubble. The chemical

reactions responsible for flameholding occur in a very small micromixed reaction

zone immediately behind the upstream-propagating flame front. By the time the

burning gases, which are disentrained into the recirculation bubble, flow back up-

stream to be reentrained in the mixing layer, combustion is nearly complete. There

is negligible chemical reaction within the hot recirculation zone, as it is composed

of almost completely bumed products. The hot recirculated gases that are mixed

in with the extemal flow merely help to stabilize the axial location of the standing

turbulent flame front.

9.1.2 The Combustion Process

9.1.2.1 Stoichiometry.

The stoichiometric or "ideal" fuel/air mixture ratio

fst

is of interest because that is the fuel/air ratio which usually results in the greatest

liberation of sensible energy from the breaking of molecular bonds. Although there

exist general rules of stoichiometry for combustion of arbitrary reactants, attention

will be restricted to hydrocarbon fuels in current use for the propulsion of aircraft.

The only oxidizer of interest is air, which will be assumed to be 21% oxygen (02)

and 79% nitrogen (N2) by volume.

The maximum combustion temperature occurs when hydrocarbon fuel mole-

cules are mixed with just enough air so that all of the oxygen atoms are consumed,

all of the hydrogen atoms form water vapor H20, and all of the carbon atoms form

carbon dioxide CO2. This ideal mixture of fuel and air is represented by a gen-

eral atom-balance equation for "complete combustion" called the stoichiometric

equation, given by

[ 79N] 79(x Y

CxHy]-(xq4)

O2"~ "

2J ''+XCO2"~-yH20"~-2 ~-~ +~)N2 (9.1)

Note that in Eq. (9.1) the nitrogen (N2) acts merely as an inert diluent, absorbing

some of the sensible thermal energy released by combustion by virtue of its specific

heat capacity.

The stoichiometric fuel-air ratio can be determined readily from the ratio of

molar coefficients of the reactants appearing on the left-hand side of Eq. (9.1). The

stoichiometric fuel/air ratio expressed as a volume or mol ratio is

1 84

f"= (x+~)Y [l+~i-

791-- lO0(4x+y) lbm°lsF/lbm°lA

where F stands for fuel and A for air.

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS 331

The stoichiometric mass-basis fuel-air ratio is given by

36x + 3y

fst --

Ibm F/Ibm A (9.2)

103 (4x + y)

A representative or generic molecule representing jet fuels is C12H23. Solving

Eq. (9.2) for x = 12 and y = 23 gives fst = 0.0685 Ibm C12H23/lbm A. Because

the fuel-air ratio in use f is always less than

fst

and

fst

is much less than unity,

it is often convenient to neglect the mass flow rate of fuel compared to the mass

flow rate of air in performance calculations.

When considering off-stoichiometric mixtures of fuel and air, it is conventional

to speak of "fuel-rich" and "fuel-lean" mixtures. To quantify this, the fuel/air

equivalence ratio, or simply the equivalence ratio, is defined as the ratio of the

actual fuel/air ratio to the stoichiometric fuel/air ratio:

4~'= -- f (9.3)

f,t

The utility of the equivalence ratio ~b is that it permits representation of either

fuel-rich or fuel-lean mixtures by multiplying the fuel term in the atom-balance

equation by ~b:

( y)[ 79 ]

epCxHy + x + -~

O2 + ~i-N2 ~ products (9.4)

The "complete combustion" assumption behind Eq. (9.1) does not imply that, in

actual practice, a stoichiometric mixture of fuel and air will yield only COz and HzO

as combustion products. In reality, the CO2 and H20 molecules will dissociate into

other molecular fragments at elevated temperature, just as happens with air alone at

high temperature. Further, for reasons to be shown in Sec. 9.1.3, it is desireable to

have very incomplete combustion occur in the turbojet combustor primary zone, so

that the actual gases leaving the primary zone will be a mixture of reactants (fuel

plus air), reaction intermediate species, dissociated products, and incompletely

oxidized fuel molecules. In addition, at elevated temperatures a very small fraction

of the atmospheric nitrogen is in fact oxidized, forming the air pollutant gases

nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N20), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). The oxidized

nitrogen species NO and

NO2 are

collectively referred to as NOx.

Finally, off-stoichiometric fuel/air ratios, as characterized by the equivalence

ratio 4~ 5 ~ 1, affect the type and distribution of combustion products, as well as the

temperature. As a practical guideline, equivalence ratios must be in the range 0.2

to 2 for combustion to occur, and equivalence ratios near or greater than unity are

of little or no interest for airbreathing aircraft propulsion applications.

For off-stoichiometric mixtures, and also for possibly incomplete combustion,

the atom-balance equation can be generalized as

79 N ]

~gfxHy--~-(x--~- Y)

O2-q- ~-- i-

2j ---+ nco2fO2-~-ncofO-~-l'lH20n20--[-...

• .. + no202 +

noO q- nNOzNO2 -k- nN2oN20 + ""

etc. (9.5)

where etc. indicates that the list of possible product gases may be as many combi-

nations of O, H, C, and N atoms as exist in nature.

IfNS

is used to denote the total

332 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

number of product species that may appear on the right-hand side of Eq. (9.5), the

messy right-hand side of Eq. (9.5) can be represented with the notation

79 N

q

NS

fbfxny

Jr"

(\x + Y]..~. 02 + ~-~

2J -->

~_niAi

(9.6)

i=1

where

A i

represents the chemical formula of the ith gas molecule appearing

in the

NS

product gases. Methods for finding the actual composition of the

post-combustion product gases, as represented by the set of mole numbers

{ni

}

in

Eq. (9.6), by assuming either chemical equilibrium or finite-rate chemistry (chem-

ical kinetics), are provided in the AEDsys software programs EQL and KINETX,

respectively.

9.1.2.2 Heat of reaction and adiabatic flame temperature.

With the

initial composition and state of the fuel/air mixture given or known, as well as at

what pressure burning will occur, it is desired to find what the temperature will be

after combustion. Assuming that combustion occurs at constant pressure, without

either heat or work transfer with the surroundings, then the total enthalpy of the

(final) products will be the same as the (initial) reactants, and that value is known.

When molecular collisions result in the exchange of atoms between molecules,

the number of molecules of each kind changes. Exothermic reactions result in the

release of chemical bonding energy, which appears in the gas mixture as sensible

thermal energy. These two kinds of energy associated with each molecule are

represented in the static enthalpy for each species,

T

= (Ah~k)536 -+- j

Cp,~

dT'

(9.7)

h 0

536

where the first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (9.7) is the enthalpy of formation

of the kth gas, which is the sum of the molecular bond energy and the sensible

enthalpy at 536°R (or 298 K), and the other term in Eq. (9.7) is the sensible

enthalpy above 536°R. Enthalpies of formation for many of the gases of interest

in combustion are given in Table 9.1.

The static enthalpy of a mixture of gases is given by

NS

= ~_~ nkh~

(9.8) H

k=l

and for the particular mixtures representing the reactants (fuel plus air) and prod-

ucts, that is, those gases appearing on the left-hand side and on the right-hand side

of Eq. (9.6), respectively,

NS NS

HR = Z(nk)lchk

and Hp = Z(nk)ph~

(9.9)

k=l k=l

If the reactants are ignited and allowed to burn to the final equilibrium state

without heat being added or removed during the process, the final equilibrium

temperature is called the adiabatic flame temperature (AFT). For example, con-

sider a case where the reactants are initially at 536°R. Because combustion occurs

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS

333

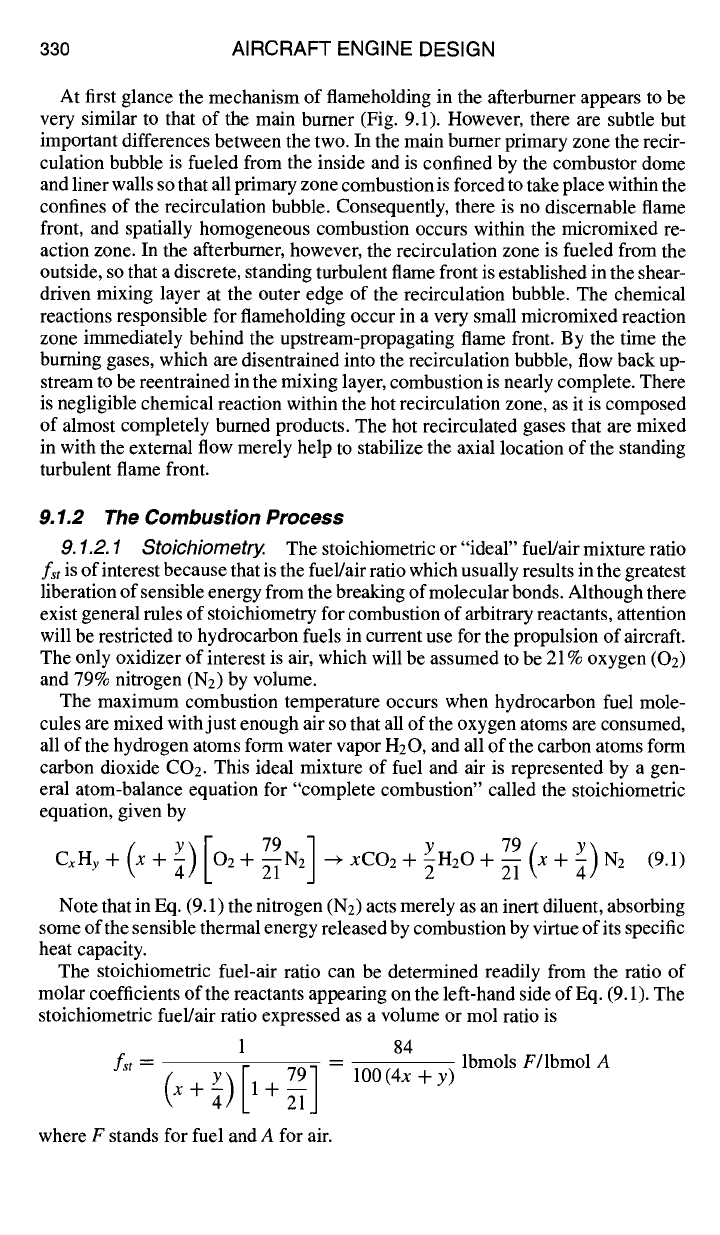

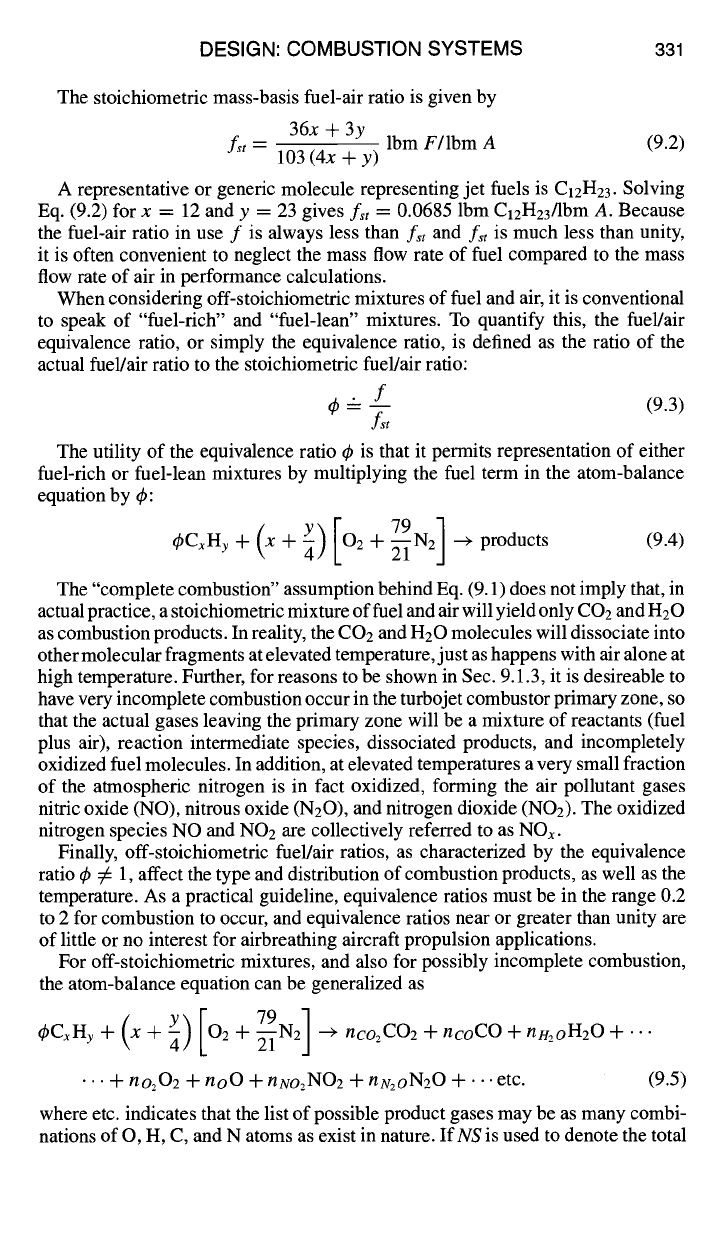

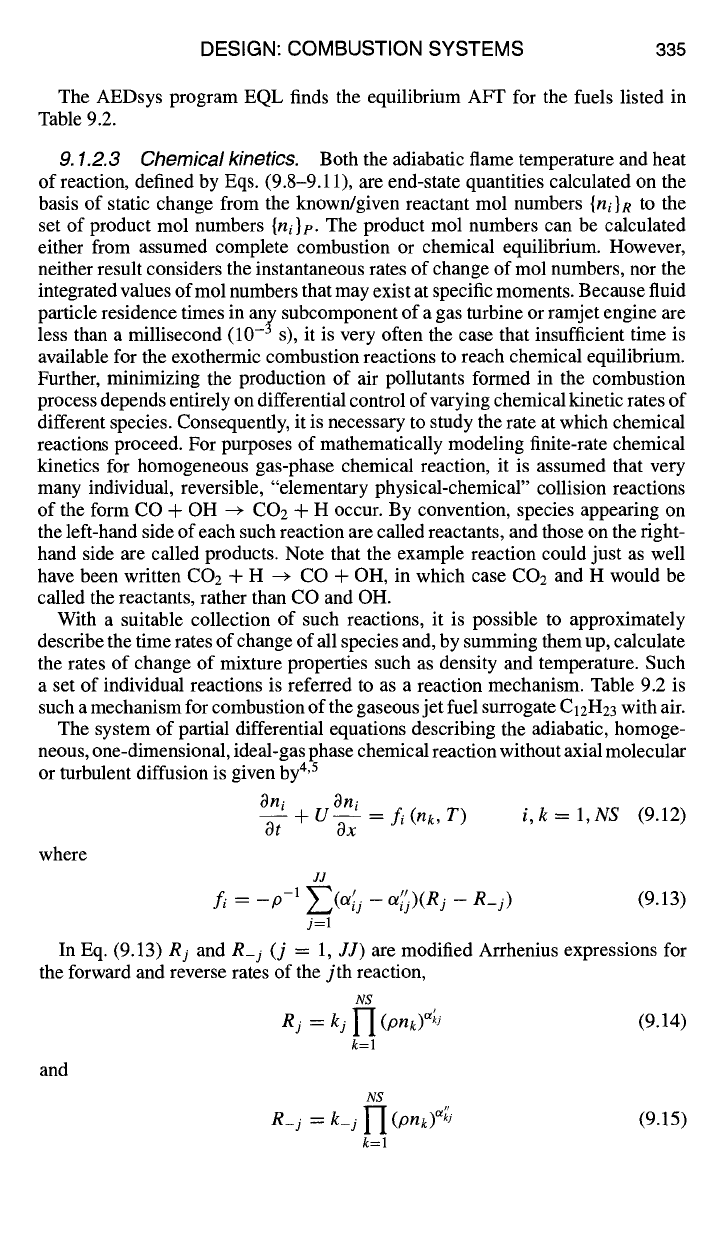

Table 9.1 Enthalpy

of formation

(Ah~k)536 for

some reactant and product gases

Gas BTUllbmol

Methane, CH4 -

32,192

Ethane, C2H6

-36,413

Hexane, C6H14

-71,784

Octane, C8H18 -89,600

Jet-A, ClzH23 - 152,981 ~

Carbon monoxide, CO -47,520

Carbon dioxide, CO2 - 169,181

Atomic hydrogen, H 93,717

Hydrogen, H2 0

Water vapor, H20 - 103,966

Atomic oxygen, O 10%139

Oxygen, 02 0

Hydroxyl, OH 16,967

Atomic nitrogen, N 203,200

Nitrogen, N2 0

Nitrous oxide, N20 35,275

Nitric oxide, NO 38,817

Nitrogen dioxide, NO2 14,228

aFor heating value h pR = 18,400 BTU/lbrn.

adiabatically, releasing sensible thermal energy, and neglecting the difference be-

tween the kinetic energy of the reactants and products, the AFT is found by solving

the algebraically implicit equation

lip = HR

(9.10)

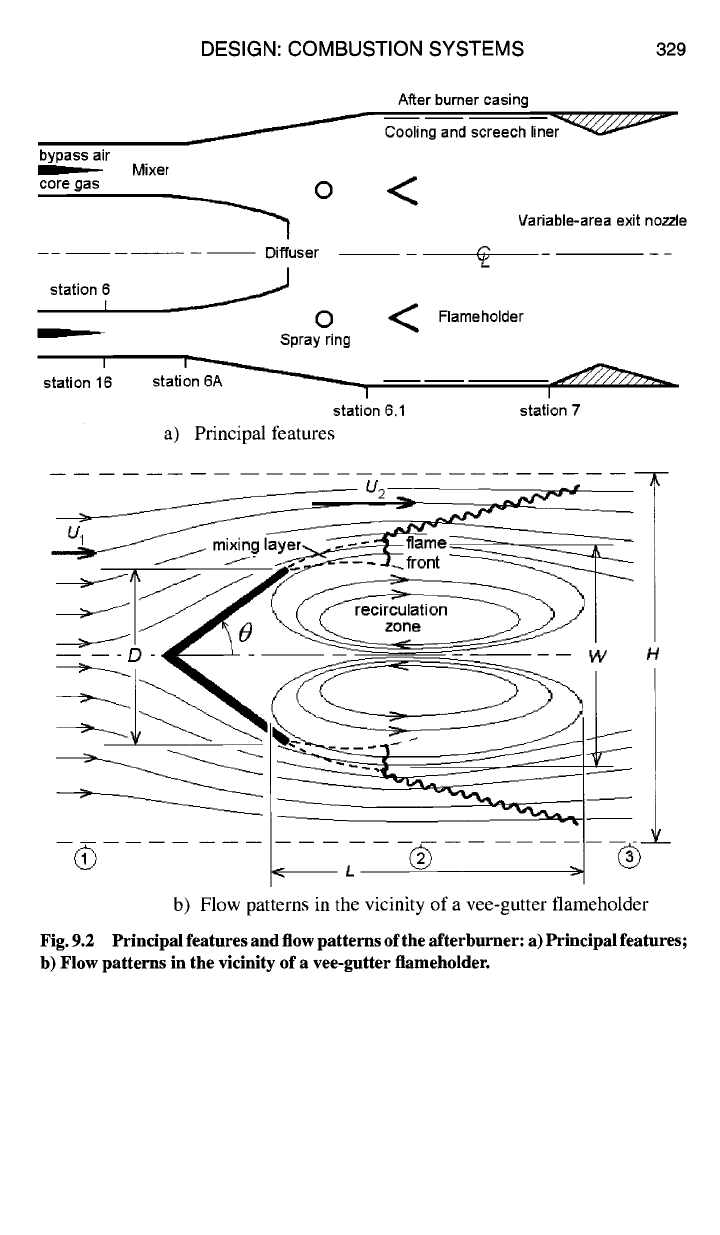

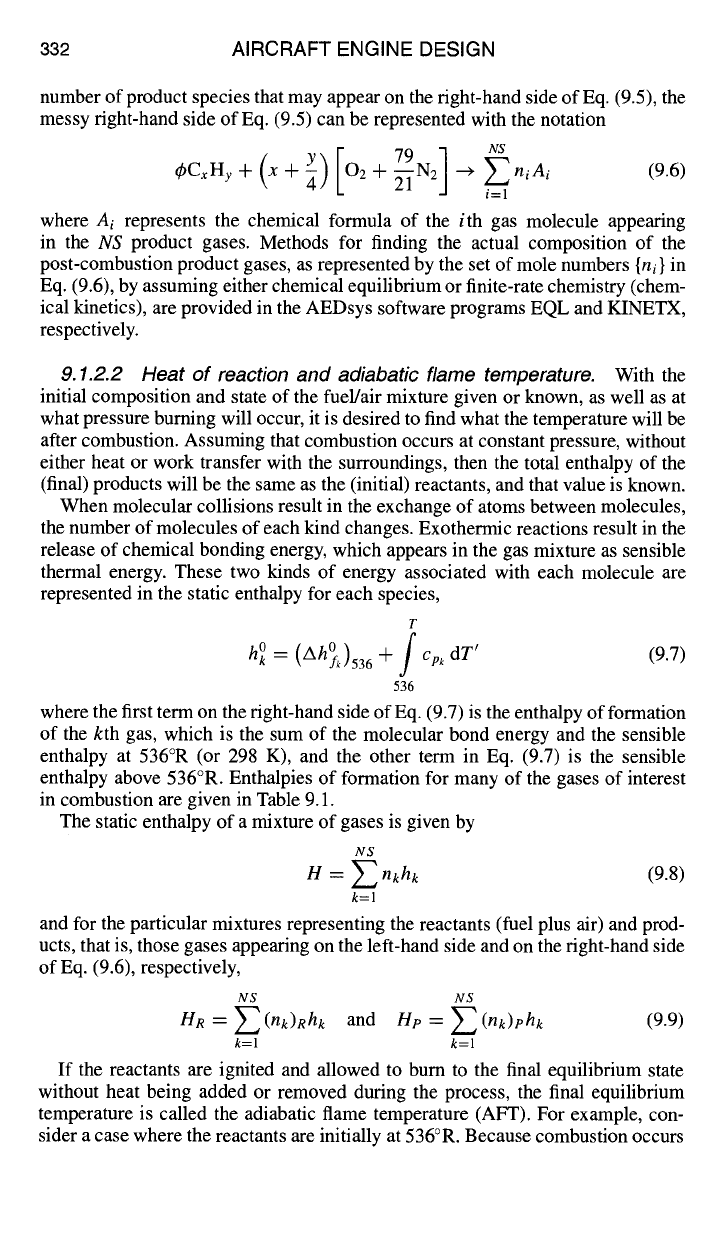

Figure 9.3 illustrates the solution of Eqs. (9.9) and (9.10). At the initial tem-

perature, assumed here to be 536°R,

Hp

is less than HR. This is because the

principal product molecules have larger negative values of enthalpy of formation

than reactant molecules, as can be seen from Table 9.1.

If the fuel/air reactant mixture temperature is initially 536°R, as illustrated in

Fig. 9.3, and if the fuel and air are in stoichiometric proportion, so that ~b = 1 in

Eq. (9.6), then the stoichiometric AFT is found from the solution of Eq. (9.10).

If the products are subsequently cooled at constant composition and pressure

until the product mixture temperature is brought back to 536°R, then the amount

of heat removed is called the heating value or heat of reaction hpR. Because the end

states of the overall process (adiabatic burning followed by cooling) are both at the

reference temperature 536°R, the relationship between the enthalpies of formation

of each species and the heating value of the fuel is determined from an energy

balance for the overall process:

NS NS

hpR = (HR)536 --(Hp)536 = ~ (ni) R (Ah~i)536 - ~ (hi) P

(Ah~i)536 (9.11)

i=1 i=1

334

AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

H

R////"

/

F.

#, )

/" i

i

A

I

j

#

J

> - _ _

-<

f

.,/

t"

/,,-"

.,,/

I /I "4,"

I ,,//

I

i/"~

///"11

:F" I

.I

536 AFT

T

Fig. 9.3 Enthalpy-temperature diagram illustrating relationship between enthalpies

of reactants

HR

and products He and between initial reactants temperature (example

shown as 536°R) and the equilibrium AFT.

If the fuel and air are initially at a temperature greater than 536°R, the solution

of Eq. (9.10) will give a proportionately greater AFT, and Eq. (9.11) will give a

value for her that differs slightly from the standard value defined at 536°R.

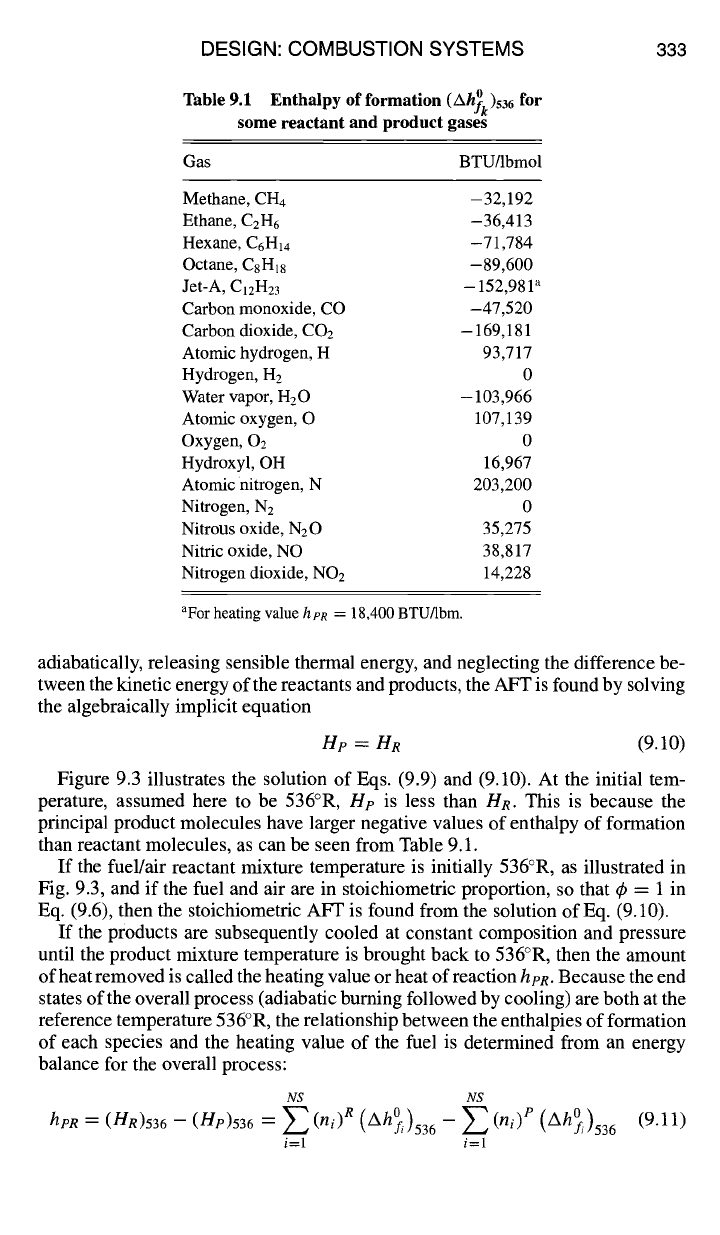

Using the enthalpies of formation listed in Table 9.1, Eq.(9.11) can be used to

calculate the heating values of fuels listed in Table 9.1. The results are presented

in Table 9.2.

Sometimes,

h?R

is called the lower heating value (LHV). This is done to dis-

tinguish it from the higher heating value (HHV), which would be realized if, in

addition to cooling the product gases to 536°R, the latent heat of vaporization were

extracted by condensing all of the water vapor in the product gases. The HHV is

not relevant for propulsion applications, as combustion products are never cooled

to ambient temperatures while inside the engine. The water condensation streams

or "contrails" that mark the sky occur outside the nozzle and thus have no effect

on engine thrust or performance.

Table 9.2 Molecular weights and heating values

her

for gaseous

fuels in Table 9.1

Gas lbrn/lbmol BTU/lbmol BTU/lbm

Methane, CH4 16 334,921 21,558

Ethane, C2H6 30 613,847 20,462

Hexane, C6H14 86 1,671,063 19,431

Octane, C8H18 114 2,199,516 19,294

Jet-A, C12H23 167 3,072,800 18,400

Carbon monoxide, CO 28 121,660 4,345

Hydrogen, H2 2 103,966 51,983

DESIGN: COMBUSTION SYSTEMS 335

The AEDsys program EQL finds the equilibrium AFT for the fuels listed in

Table 9.2.

9.1.2.3 Chemical kinetics. Both the adiabatic flame temperature and heat

of reaction, defined by Eqs. (9.8-9.11), are end-state quantities calculated on the

basis of static change from the known/given reactant mol numbers

{ni}R

to the

set of product mol numbers

{ni}p.

The product mol numbers can be calculated

either from assumed complete combustion or chemical equilibrium. However,

neither result considers the instantaneous rates of change of mol numbers, nor the

integrated values ofmol numbers that may exist at specific moments. Because fluid

particle residence times in any subcomponent of a gas turbine or ramjet engine are

less than a millisecond (10 -3 s), it is very often the case that insufficient time is

available for the exothermic combustion reactions to reach chemical equilibrium.

Further, minimizing the production of air pollutants formed in the combustion

process depends entirely on differential control of varying chemical kinetic rates of

different species. Consequently, it is necessary to study the rate at which chemical

reactions proceed. For purposes of mathematically modeling finite-rate chemical

kinetics for homogeneous gas-phase chemical reaction, it is assumed that very

many individual, reversible, "elementary physical-chemical" collision reactions

of the form CO + OH -* CO: + H occur. By convention, species appearing on

the left-hand side of each such reaction are called reactants, and those on the right-

hand side are called products. Note that the example reaction could just as well

have been written CO: + H --~ CO + OH, in which case CO2 and H would be

called the reactants, rather than CO and OH.

With a suitable collection of such reactions, it is possible to approximately

describe the time rates of change of all species and, by summing them up, calculate

the rates of change of mixture properties such as density and temperature. Such

a set of individual reactions is referred to as a reaction mechanism. Table 9.2 is

such a mechanism for combustion of the gaseous jet fuel surrogate

C12H23

with air.

The system of partial differential equations describing the adiabatic, homoge-

neous, one-dimensional, ideal-gas phase chemical reaction without axial molecular

or turbulent diffusion is given by 4'5

Oni Oni

O--f +U-~x = fi(nk, T) i,k= l,NS

(9.12)

where

JJ

fi = _p-1 ~-'~(Ol~j -- Ol~)(Rj -- R_j)

(9.13)

j=l

In Eq. (9.13) Rj and R_j (j = 1,

JJ) are

modified Arrhenius expressions for

the forward and reverse rates of the jth reaction,

NS

Rj = kj I-I (pnk)u'k2

(9.14)

k=l

and

NS

R_j = k_j 1-I (Pnk)%

k=l

(9.15)