Kelter P., Mosher M., Scott A. Chemistry. The Practical Science

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ratio, by mass. This is called the law of definite composition. This law is true for all

compounds, irrespective of the source of the compound. We can illustrate the law

of definite composition using a compound containing the elements iron and sul-

fur, called iron(II) sulfide. If we analyze the composition of two different samples

of iron(II) sulfide, we find that their mass ratios are identical.

Result from Analysis of Two Samples of Iron(II) Sulfide

Sample A: Compound mass = 42.0 g

Sample B: Compound mass = 100.0 g

Mass Ratios

Sample A: 26.7 g Fe/15.3 g S = 1.74:1.00 = ratio of g Fe to g S

Sample B: 63.5 g Fe/36.5 g S = 1.74:1.00 = ratio of g Fe to g S

We can also think of this law in the reverse fashion. Suppose we were inter-

ested in making an 80.0-g glass of water from its elements, hydrogen and oxygen.

Given that the mass ratio of oxygen to hydrogen in water is 7.99:1.00, we would

need to chemically combine 1.00 g of hydrogen for every 7.99 g of oxygen to

make the water. In our specific example, then, we would need 8.90 g of hydrogen

and 71.1 g of oxygen to make 80.0 g of water. Water is water; it is never made up

of a different mass ratio of its components.

Preparation of Water (H

2

O)

Hydrogen 8.90 g

Oxygen 71.1 g

Water 80.0 g

Mass Ratio

Water: 71.1 g oxygen/8.90 g hydrogen = 7.99:1.00 g oxygen to g hydrogen

EXERCISE 2.1 Investigating the Law of Definite Composition

Suppose that you collected two samples of pure bottled water.

a. If you separated the water into hydrogen and oxygen and obtained the

following results, what would you report as the ratio of the mass of oxygen to

that of hydrogen in each sample?

Sample 1: 37.3 g of oxygen; 4.67 g of hydrogen

Sample 2: 69.3 g of oxygen; 8.67 g of hydrogen

b. Do these data support the law of definite composition?

c. If you obtained another sample of water and found it to contain 17.0 g of

oxygen, how many grams of hydrogen would you expect to obtain?

Solution

a. The ratios of oxygen to hydrogen in these two samples are

Sample 1:

37.3goxygen

4.67 g hydrogen

=

7.99 g oxygen

1.00 g hydrogen

Sample 2:

69.3goxygen

8.67 g hydrogen

=

7.99 g oxygen

1.00 g hydrogen

b. Yes, the ratios are the same for different masses of the same compound, so

these data support the law of definite composition.

48 Chapter 2 Atoms: A Quest for Understanding

FeS (iron pyrite).

c. Because the ratio of oxygen to hydrogen is constant in the compound called

water, we would expect to have a ratio of 7.99 g of oxygen to 1.00 g of

hydrogen. Using words, we say, “7.99 grams of oxygen is to 1.00 gram of

hydrogen as 17.0 grams of oxygen is to how many grams of hydrogen?” Using

equations, we can write

7.99 g oxygen

1.00 g hydrogen

=

17.0goxygen

?ghydrogen

Rearranging yields

17.0goxygen×1.00 g hydrogen

7.99 g oxygen

=?ghydrogen

=

2.13 g hydrogen

PRACTICE 2.1

Given the information in Exercise 2.1, determine how many grams of oxygen will

combine with 24.5 g of hydrogen to make water. How many grams of water will be

made?

See Problems 9 and 10.

The law of conservation of mass and the law of definite composition provide

two fundamental descriptions of the behavior of chemical processes. When they

were discovered, there was no satisfactory explanation for them.After all, they are

just chemical laws that describe observations of the natural world. Many scien-

tists searched for explanations of these two laws. One of these was the English

scientist John Dalton (1766–1844; see Figure 2.5).

2.2 Dalton’s Atomic Theory and Beyond

John Dalton performed experiments on compounds in which two elements

made more than one type of compound. This is not unusual. There are many ex-

amples of compounds that contain the same elements but in different ratios. For

example, we can combine oxygen and nitrogen to make many different com-

pounds, three of which are shown in Table 2.1. Note how each has a different

mass of oxygen that combines with a given mass of nitrogen.

The results demonstrate a general law formulated by Dalton: When the same

elements can produce more than one compound, the ratio of the masses of this

element that combine with a fixed mass of another element is a small whole number.

This is known as the

law of multiple proportions. Using the information in

Table 2.1, we see that in nitric oxide, 14.0 g of nitrogen combines with 16.0 g of

2.2 Dalton’s Atomic Theory and Beyond 49

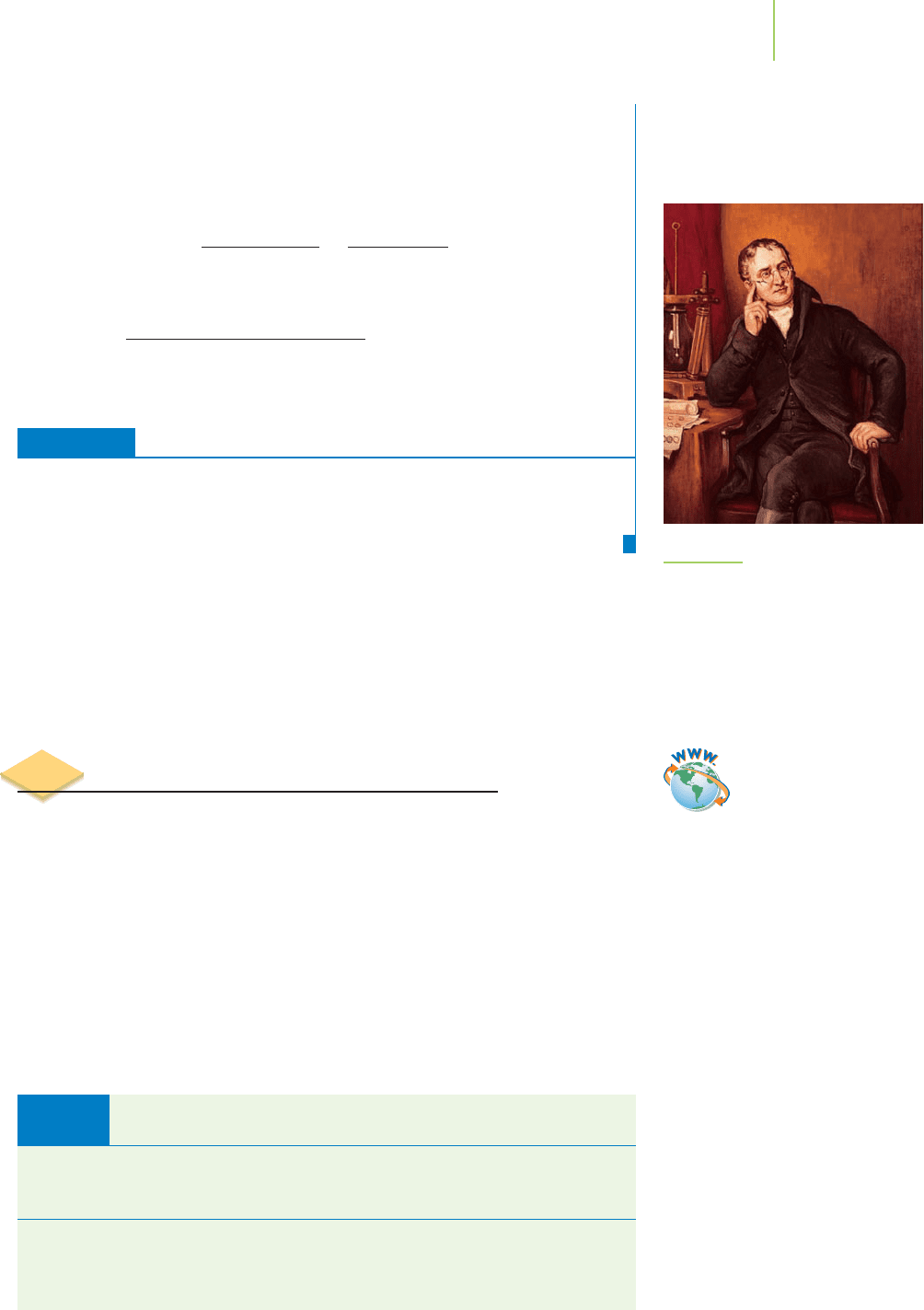

FIGURE 2.5

John Dalton, a poor Quaker school-

teacher and brilliant amateur meteorolo-

gist, developed the basic points of the

atomic theory. He showed early signs of

brilliance and even began teaching others

in his small English hometown when he

was only ten years old.

Compounds Containing Nitrogen and Oxygen:

Comparing Oxygen to Oxygen

Ratio of Mass of Oxygen

Fixed Mass Mass of in Compound to Mass

Common Name of Nitrogen Oxygen of Oxygen in Nitric Oxide

Nitric oxide 14 g 16 g 1:1

Nitrogen dioxide 14 g 32 g 2:1

Nitric anhydride 14 g 40 g 5:2

TABLE 2.1

Video Lesson: Early Discoveries

and the Atom

oxygen. A different compound of these same two elements exists in which 14.0 g

of nitrogen combines with 32.0 g of oxygen. The ratio of the masses of oxygen

that combine with the same mass of nitrogen (14.0 g, in this case), is 32.0 g/16.0 g,

or 2:1, a small whole number. The same ratio in nitric anhydride is 40.0 g/16.0 g,

or 2.5:1. This is 5:2 in small whole numbers.

Why is the ratio of the components in such compounds based on small whole

numbers?

The implication of these results is illustrated in Figure 2.6. Dalton won-

dered whether these results could be explained by the existence, for each element,

of some basic particle with a specific mass that would be the smallest part of every

element. Moreover, his experiments were giving results that were entirely consis-

tent with this idea. In 1803 he presented the results of his experiments before the

Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. His ideas, which came to be

known as

Dalton’s atomic theory, are summarized in Table 2.2.

Dalton’s atomic theory was a keystone in the foundation of chemistry, but as

we shall see, not all of it is correct. However, his theory teaches us something very

important about the scientific method: Ideas don’t need to be completely correct

to be very useful and influential. Dalton was limited by the measurements he was

able to make at the turn of the nineteenth century. Our ability to know the mass

of objects is orders of magnitude better now than in Dalton’s time, and our un-

derstanding is therefore significantly better. Still, we view Dalton’s atomic theory

as a great step forward in chemistry, because it focused attention on the valid idea

that compounds are made from little bits—atoms—combining in fixed propor-

tions and that chemical reactions are rearrangements of these atoms.

The Law of Combining Volumes

One example of the refinement of ideas in the light of new information is pro-

vided by the work of the French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778–1850;

see Figure 2.7). Gay-Lussac carefully measured the changes in volume when gases

reacted to produce other gases. His results are summarized in what became

known as the

law of combining volumes, which states that when gases combine, they

do so in small whole-number ratios, such as 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, and 3:2, provided that all

the gases are at the same temperature and pressure. One example is illustrated in

Figure 2.8.

50 Chapter 2 Atoms: A Quest for Understanding

Dalton’s Atomic Theory

• Every substance is made of atoms.

• Atoms are indestructible and indivisible.

• Atoms of any one element are identical.

• Atoms of different elements differ in their masses.

• Chemical changes involve rearranging the attachments between atoms.

TABLE 2.2

N: 14 g

O: 16 g

N: 14 g

O: 32 g

NO

2

NO

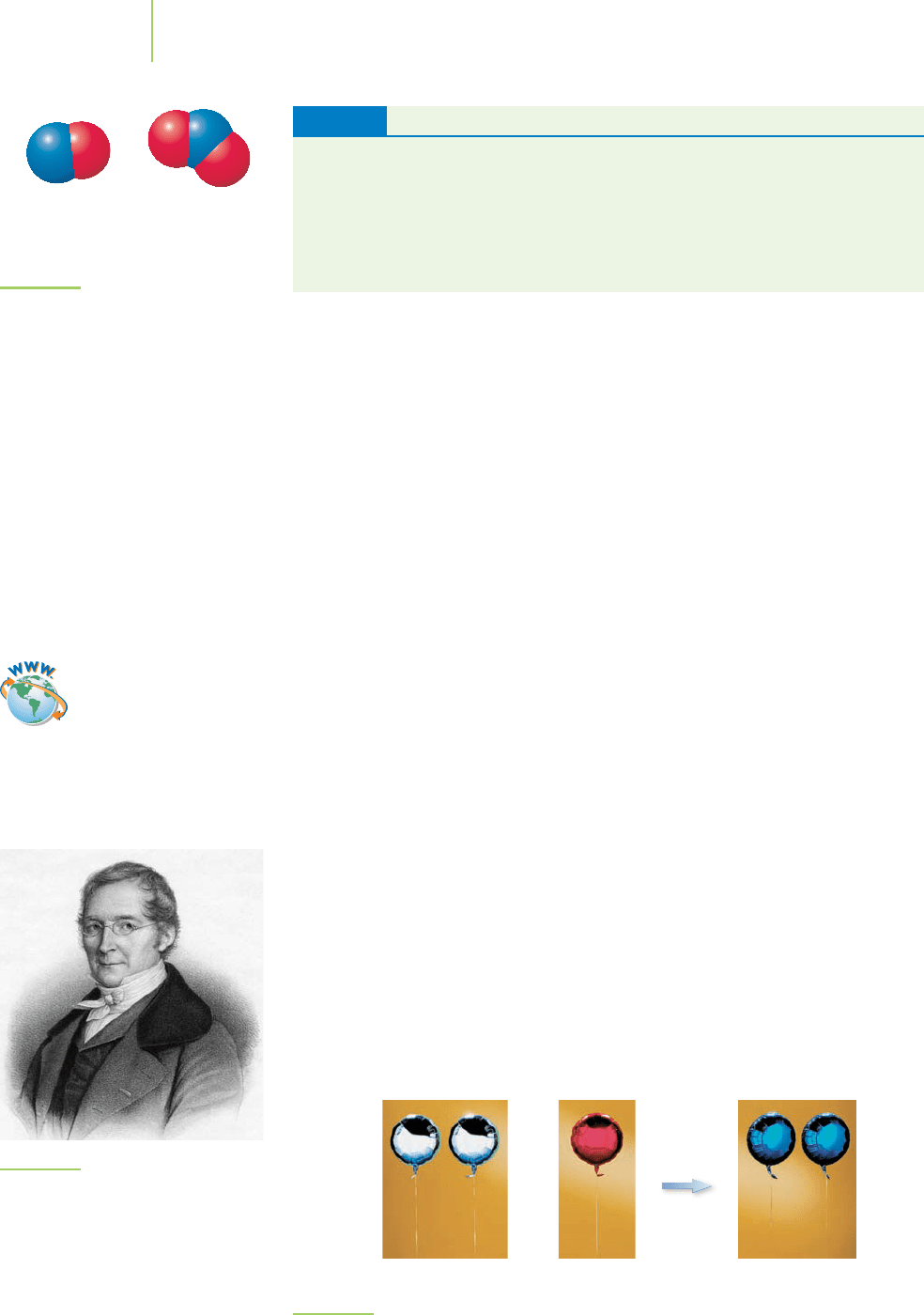

FIGURE 2.6

The ratio of the mass of oxygen in

NO

2

to its mass in NO is a simple

whole number.

FIGURE 2.7

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778–1850)

was the eldest of five children. His col-

leagues considered him a careful, elegant

experimentalist. He introduced the terms

pipette and burette and was the first to

isolate the element boron. He is most

noted for publishing Charles’s law (see

Chapter 10) and formulating the law of

combining volumes.

2 balloons of H

2

+

1 balloon of O

2

2 balloons of H

2

O

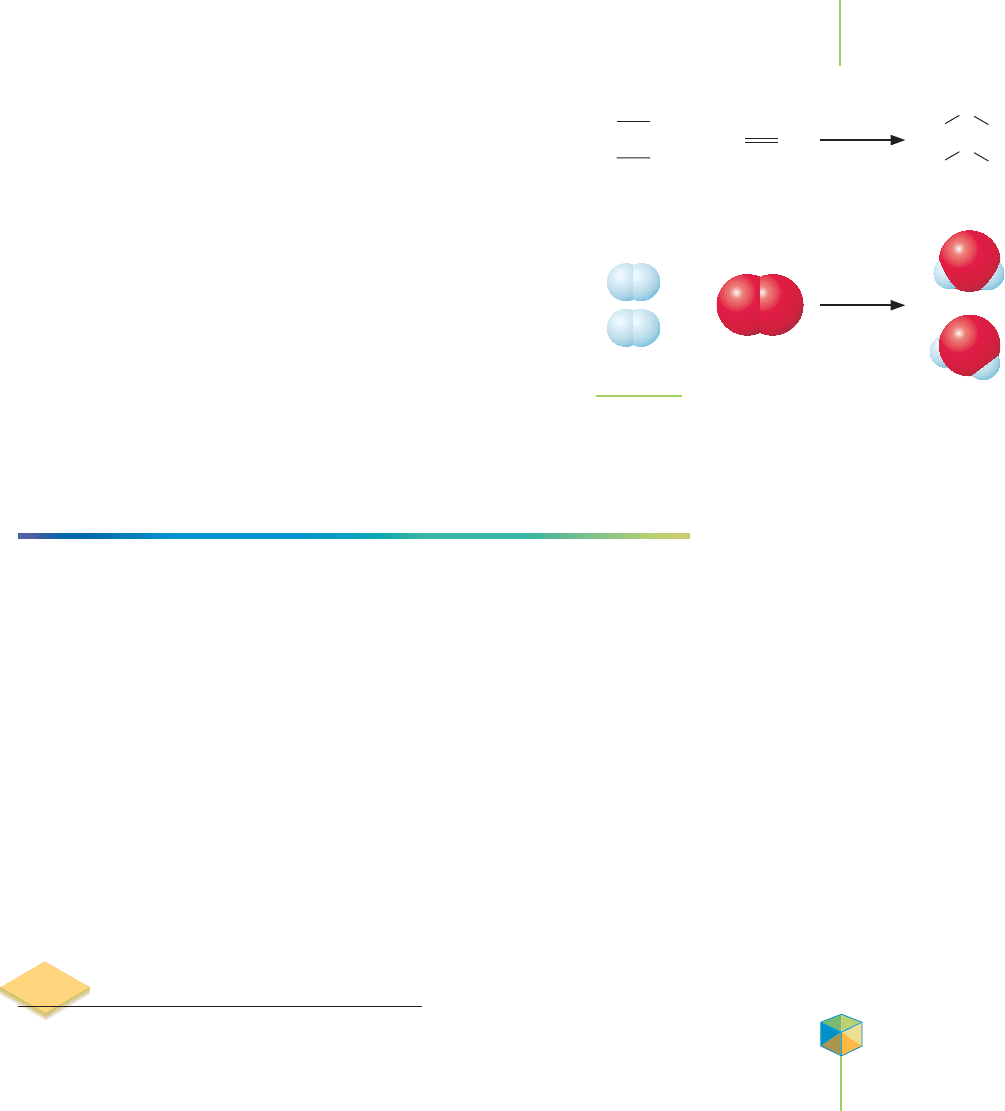

FIGURE 2.8

Oxygen and hydrogen combine to form water vapor. According to the law of combining volumes,

two volumes of hydrogen react with one volume of oxygen to make two volumes of water vapor.

Visualization: Oxygen,

Hydrogen, Soap Bubbles,

and Balloons

Dalton could not accept the results in that example because it

contradicted his understanding of what would have to happen at

the level of individual particles. To fit with Gay-Lussac’s law, it

seemed to Dalton that one oxygen atom would have to split in two

in order to react with two hydrogen atoms and produce two parti-

cles of water. Dalton’s atomic theory said that atoms could not be

split in two, so he presumed that either Gay-Lussac’s results or his

reasoning must be flawed. The apparent difficulty disappears,

however, when we realize that oxygen gas consists of oxygen mol-

ecules (O

2

), each composed of two oxygen atoms bonded to-

gether. We also now know that hydrogen gas is composed of H

2

molecules and that each water molecule contains two hydrogen

atoms and one oxygen atom (H

2

O). One molecule of oxygen can

combine with two molecules of hydrogen to create two molecules

of water as shown in Figure 2.9.

HERE’S WHAT WE KNOW SO FAR

The information gleaned by applying the scientific method to investigate the

makeup of matter has provided us with a basic look at the nature of chemistry.

Specifically, we know that

■

Matter can be neither created nor destroyed in a chemical reaction.

■

Matter is composed of small indestructible particles called atoms.

■

Compounds are made by combining atoms in whole-number ratios.

■

The components of a compound are always present in the same ratio, by mass.

■

A chemical reaction rearranges the attachments that hold atoms together in a

compound.

These points illustrate the scientific laws identified by Gay-Lussac, Lavoisier,

Proust, and Dalton. In addition, Dalton’s atomic theory helps to solidify our un-

derstanding of these laws and of the nature of the atom. In the next sections of

this chapter, we will begin to examine the makeup of the atom.

2.3 The Structure of the Atom

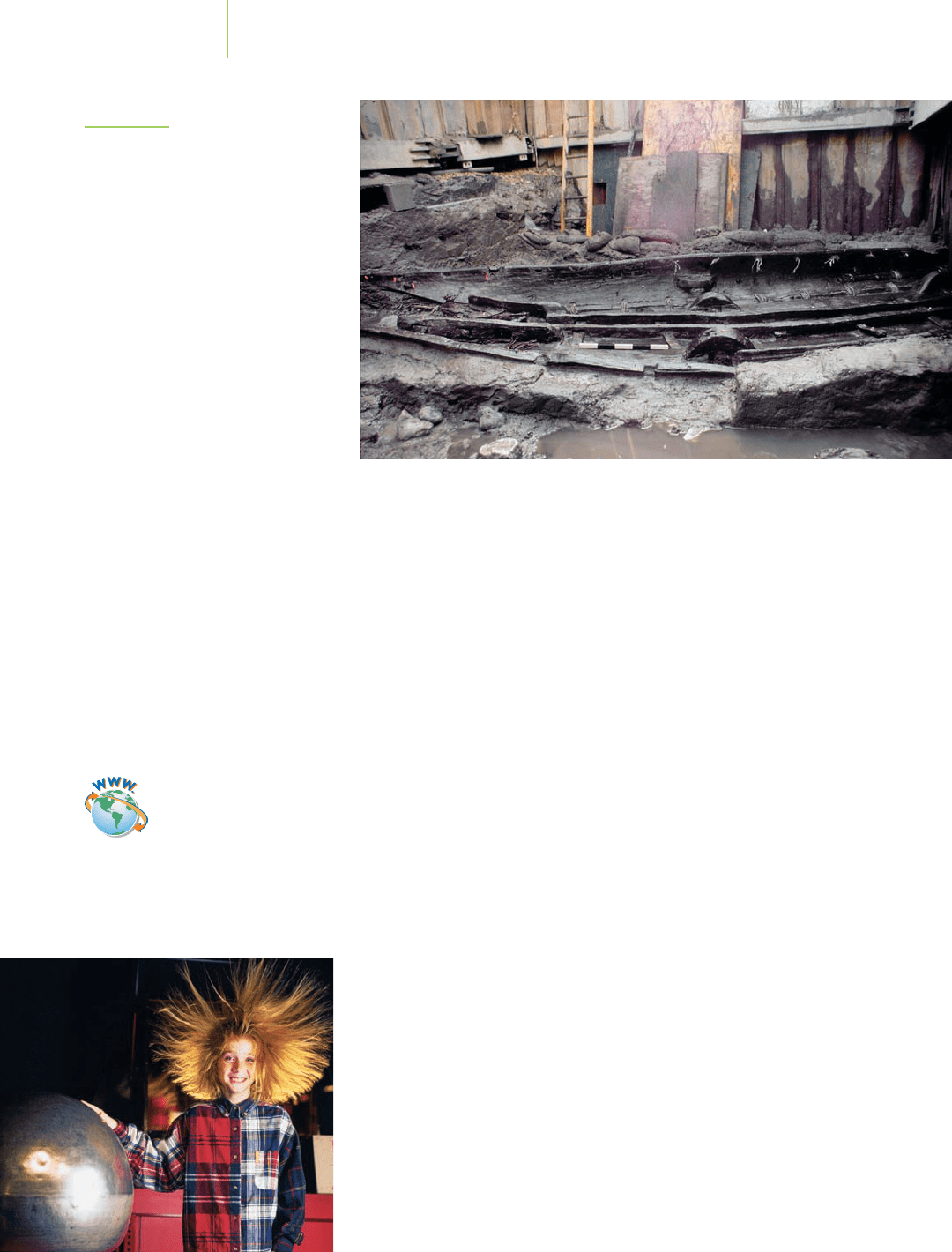

Archaeology, the study of past human activities, often requires scientists to be able

to assign ages to artifacts that have been unearthed. In some cases, such relics can

be dated because they are buried underneath objects for which an age is known. In

other cases, the archaeologists must perform laboratory experiments to estimate

the age of the artifact. One exciting discovery that helped provide a wealth of

information about ancient boat construction was found buried under 6 feet of

earth in Dover, England. The “Dover Boat,” as it has become known, was discov-

ered underneath the footings of an ancient city wall (Figure 2.10).

Archaeologists knew the date that the wall was constructed from historical

records and, judging from its location, surmised that the boat was probably older

than the wall under which it was buried. To get an accurate age of the boat,

though, they needed to perform “radiocarbon dating” on small pieces of wood

from the boat.

What is the basis of this process, and what can it teach us about

atomic structure?

Some of the carbon atoms in living things emit certain particles and energy

(radioactivity) that allows the atoms to become more energetically stable (see

Chapter 21). It has been observed that the amount of radioactive carbon remains

relatively constant while the organism is alive, as life’s processes allow the

2.3 The Structure of the Atom 51

HH

H

O

H

H

O

WaterOxygenHydrogen

H

HH

OO

+

+

FIGURE 2.9

It is because the elemental forms of hydrogen and oxygen

exist as diatomic substances that the law of combining

volumes makes sense at the molecular level.

Application

C

HEMICAL ENCOUNTERS:

The Dover Boat and

Radiocarbon Dating

52 Chapter 2 Atoms: A Quest for Understanding

FIGURE 2.10

The hull of the Dover Boat is partially ex-

cavated in this figure. Note the construc-

tion of the rails running down the center

of the boat. These rails were used to

fasten the two halves of the boat

together.

exchange of atoms between, for example, a tree and its environment. Once death

occurs, however, the radioactive carbon in the tree begins to diminish. If you

can measure the amount of radioactive carbon remaining in a piece of wood,

you can estimate the year in which the tree died. The results of radiocarbon dat-

ing on the Dover Boat indicated that it was constructed around 1550

B.C.

The previous discussion implies that some carbon atoms (those that are ra-

dioactive) are different from other carbon atoms (those that are not radioactive.)

Dalton’s claim that all atoms of any one element are identical is not correct.

What

is it about the structure of the atom that gives rise to more than one type of the

same element?

A brief look back in time will help us answer this question.

Electrons, Protons, and Neutrons

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, scientists were able to make measurements that

changed our fundamental understanding of the structure of the atom. In

the 1880s, Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish researcher working at the Academy of

Sciences in Stockholm, found that some solutions contained large numbers of

“electrically charged atoms.” Arrhenius found, for example, that when copper

chloride was placed in water and the positive and negative terminals of a power

supply were immersed in the solution, copper collected at one electrode and

chlorine collected at the other. He concluded that some atoms were themselves

negatively charged and others positively charged, causing each to be attracted to

the electrode carrying the opposite charge. This work provided some of the ear-

liest evidence for the existence of what we now call ions.

In 1891, the English scientist G. Johnstone Stoney examined the physical

properties of electricity. To represent a distinct unit of electricity, he proposed

the name

electron, from the Greek word elecktron (meaning “amber”), because

rubbing a rod of amber on wool gives rise to what we now call static electricity.

Were electrons small, charged pieces of atoms? If so, then atoms could no longer

be thought of as small, indestructible or indivisible units of matter!

Many scientists noted that the discovery of the electron suggested that

Dalton’s atomic theory was inadequate. One such scientist, Joseph John (“J. J.”)

Thomson (1856–1940; see Figure 2.11), reasoned that if Dalton’s ideas about the

indestructibility of an atom were true, how could negatively charged parts of

atoms (the electrons) be released from the atom? Furthermore, if negative parti-

cles were present, wouldn’t positively charged pieces of atoms also exist? It makes

sense that an atom with negatively charged particles inside must, in order to be

Static electricity.

Video Lesson: Understanding

Electrons

electrically neutral overall, have a balancing positive charge associated with it.

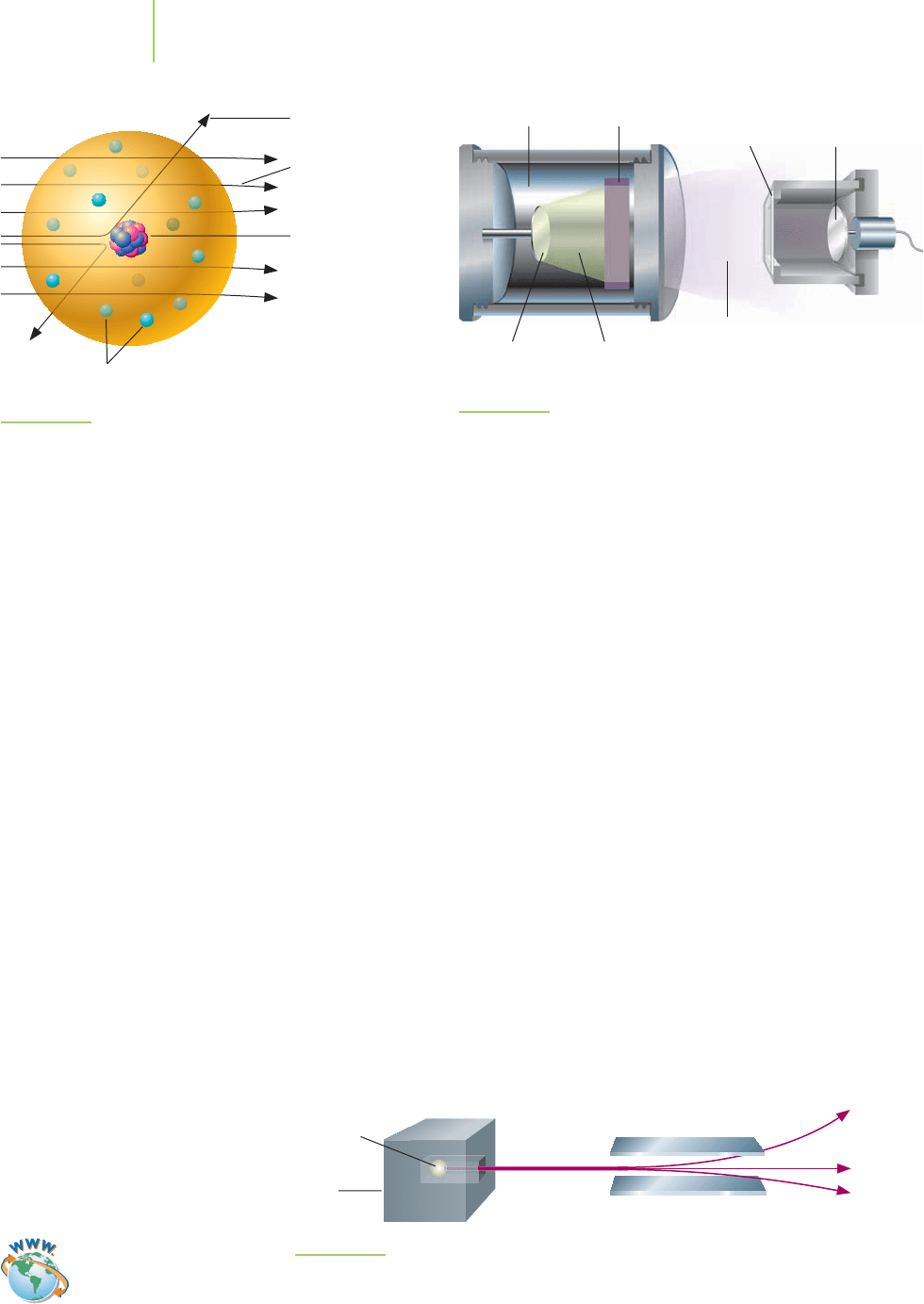

Thomson envisioned such an atom. In 1904, he wrote that “the atoms of the ele-

ments consist of a number of negatively electrified corpuscles (electrons) en-

closed in a sphere of uniform positive electrification.” His model of the atom

(shown in Figure 2.12) was known as the “plum pudding model.” This model

helped scientists understand what an atom might look like.

Radioactivity and the Structure of the Atom

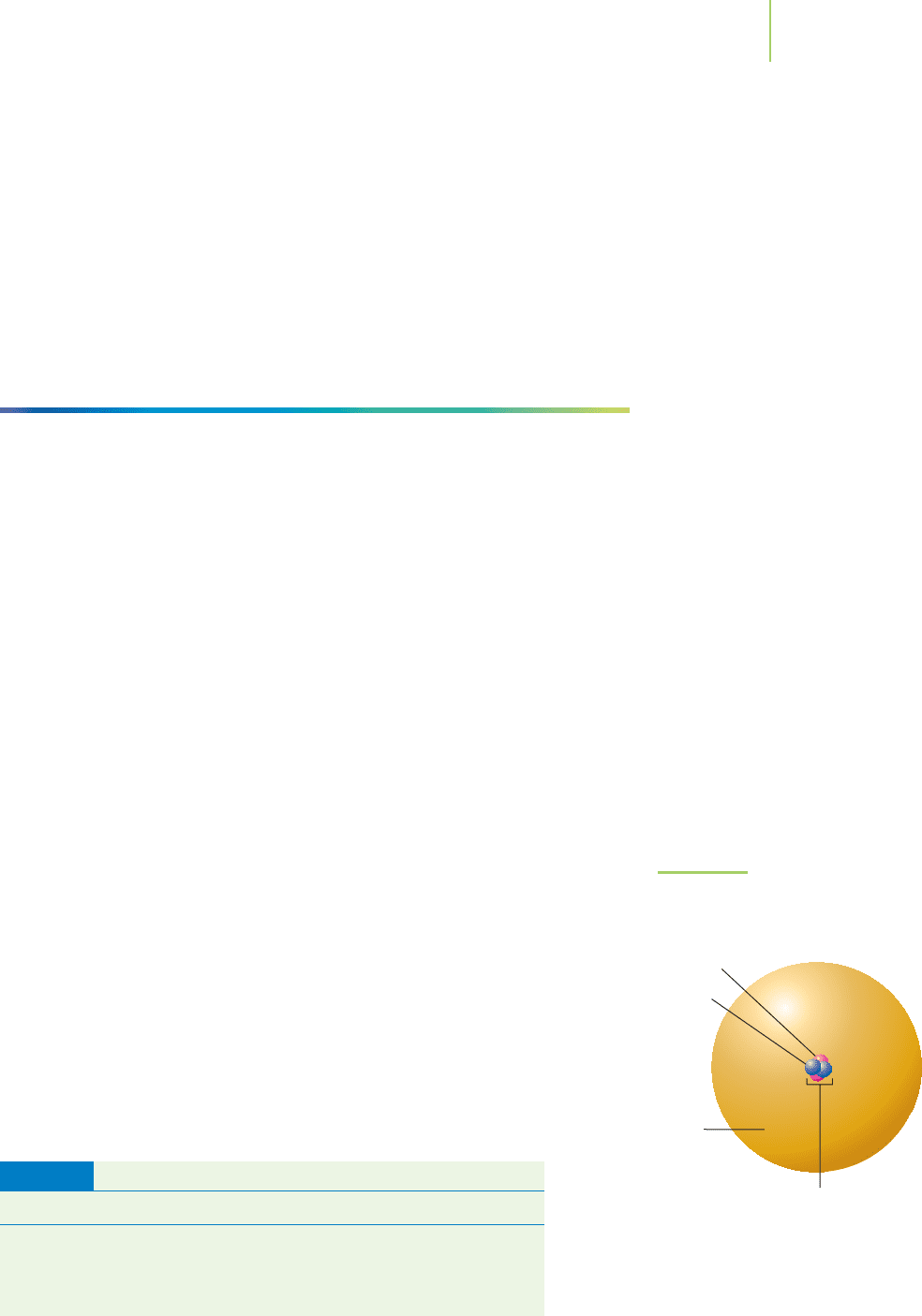

In 1909 Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937; see Figure 2.13), a New Zealand–born

physicist and former student of J. J. Thomson, and his student Ernest Marsden

(1889–1970), performed experiments in which positively charged radiation was

directed toward a thin sheet of gold foil (Figure 2.14). If Thomson’s plum pud-

ding model of the atom were correct, most of the positively charged radiation

would be expected to pass through the foil and undergo slight deflections as

its positive charge interacted with the negatively charged electrons scattered

throughout the atoms. Instead, most of the radiation went straight through the

foil without deflection, some of the radiation was scattered at very wide angles,

and—most amazingly—some was deflected nearly straight back toward its source,

as shown in Figure 2.15. In 1911 Rutherford explained this startling result. His ex-

planation led to a new model of the atom in which a small region of very

concentrated positive charge existed within a large area of mostly empty space

containing negatively charged electrons (see Figure 2.15).

Rutherford used the term

proton (from the Greek protos, meaning “first”) to

describe the nucleus of the hydrogen atom. However, his calculations of the mass

2.3 The Structure of the Atom 53

FIGURE 2.11

Joseph John (“J. J.”) Thomson

(1856–1940) provided the first model

of the structure of the atom, known

as the plum pudding model. 1906, “in

recognition of the great merits of his

theoretical and experimental investi-

gations on the conduction of electric-

ity by gases,” he was awarded the

Nobel Prize in physics.

Electrons

Cloud of

positive charge

FIGURE 2.12

The plum pudding model of the atom.

FIGURE 2.13

Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937) was

born in New Zealand after his family

emigrated there from Scotland in the

mid-1800s. As a student of Thomson

at Cambridge, he developed an in-

strument that could detect electro-

magnetic radiation. Later, while

he worked at McGill University

(Montréal, Canada) and at the Uni-

versity of Manchester (England), he

investigated the actions of alpha

particles. For his discoveries, he was

awarded the Nobel Prize in chem-

istry in 1908.

Radioactive

source

Screen to detect

scattered particles

Gold foil

particle beam

FIGURE 2.14

The Rutherford gold foil experiment. Positively charged radiation is directed toward a small piece

of gold foil. Although most of the radiation passes through the foil, a noticeable percentage is

scattered backward by the foil. This led Rutherford to develop a new model of the atom.

Video Lesson: Understanding

the Nucleus

Visualization: Gold Foil

Experiment

of an atom made from a nucleus of protons didn’t agree with the experimentally

determined mass of the atom. He theorized that some other kind of particle must

be in the nucleus too and suspected that it was probably electrically neutral be-

cause the positive electric charge on the nucleus already balanced the negative

charge of the electrons.

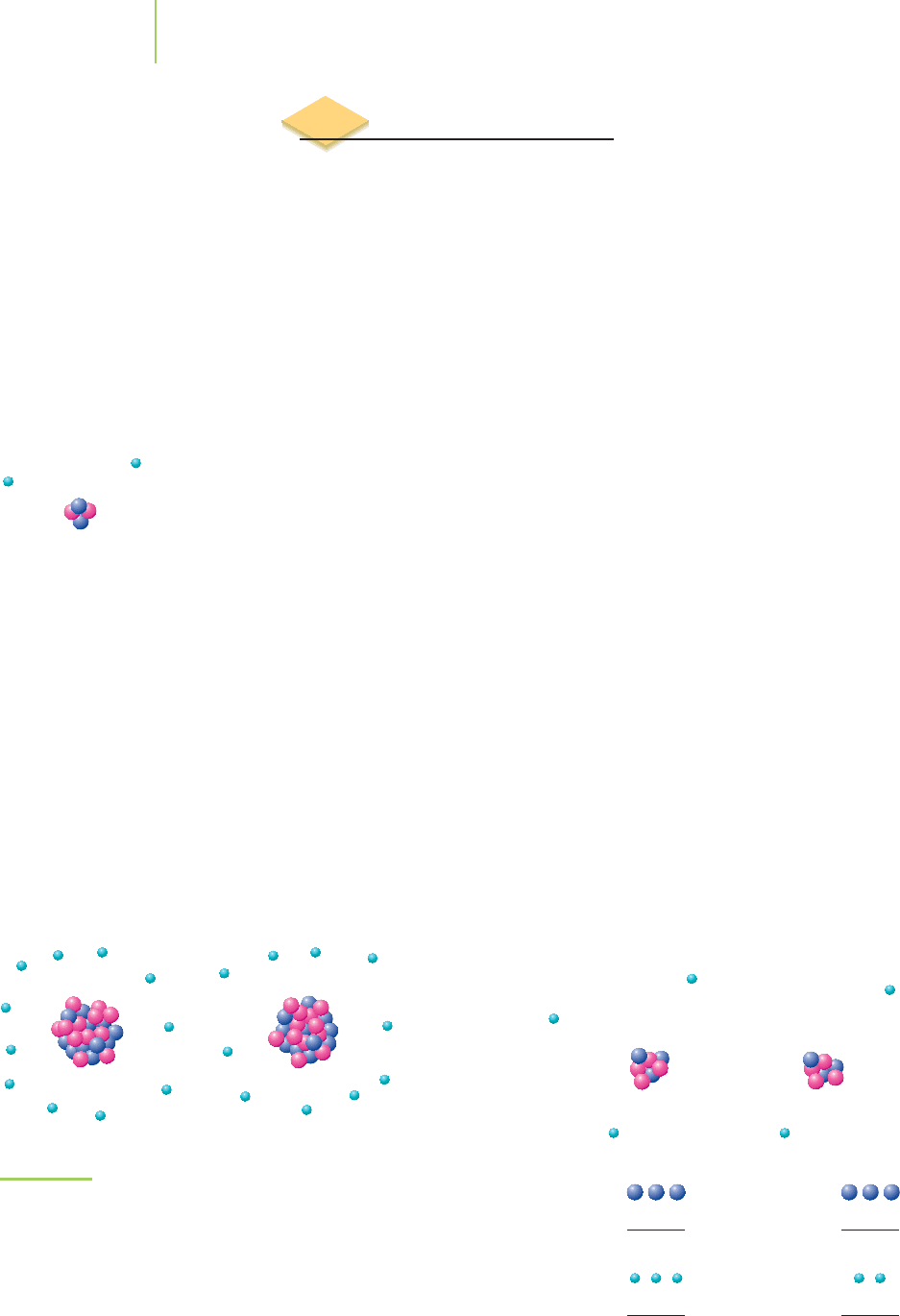

In 1932 James Chadwick (1891–1974) set up an experiment that allowed radi-

ation from beryllium atoms to strike a block of paraffin wax. This resulted in the

loss of protons from the wax. After calculating the force that would be needed to

cause the ejection of the nuclei from the sample of paraffin, Chadwick realized

that the radiation from the beryllium must be electrically neutral and have a mass

approximately equal to that of the proton. Chadwick had discovered the

neutron.

The diagram in Figure 2.16, reproduced from the original article in which he pub-

lished his results, illustrates the process that Chadwick used.

These discoveries also led to understanding of the different forms of radia-

tion. In short, some atoms are unstable and can undergo

radioactive decay

by spontaneously emitting high-energy radiation, sometimes accompanied by

fast-moving particles. Collectively, this phenomenon is known as

radioactivity.

The three most common types of radioactivity are

gamma rays (γ rays), alpha

particles

( particles) and beta particles (β particles) (Figure 2.17).

54 Chapter 2 Atoms: A Quest for Understanding

Electrons

Some α particles

are scattered.

Most α particles

pass straight

through.

Nucleus at the

center with a

positive charge

FIGURE 2.15

Some of the positively charged radiation

interacts with the positive nucleus of the

atom.

Vacuum

Radioactive

particles

Neutrons

Radioactive

source

Beryllium

Thin wax

sheet

Detector

FIGURE 2.16

Chadwick’s experiment directed neutral radiation at a block of paraffin

wax. The energy of the particles that resulted from the collision of the

radiation and the wax led to the discovery of the neutron. The radiation

was generated by placing radioactive polonium near a sheet of beryllium

metal. The wax, shaped into a thin sheet, was placed in front of the

detector.

Radioactive

material

Positively charged plate

Negatively charged plate

(+)

(–)

Lead

block

α particles

β particles

γ rays

FIGURE 2.17

Radiation emitted from a radioactive element placed in a lead block. Alpha particles and beta

particles are deflected by an electric field. Alpha particles are positively charged and therefore

are pulled toward a negatively charged plate. Beta particles are negatively charged and hence are

pulled toward a positively charged plate. Gamma rays are not charged and therefore are not de-

flected by the electric field.

Visualization: Nuclear Particles

Gamma rays are a very energetic form of electromagnetic radiation, with the

same physical nature as visible light but a much higher energy. An alpha particle

is just the nucleus of the helium atom. It is composed of two protons and two

neutrons and carries a total charge of +2. Alpha particles were the type of radia-

tion directed toward the foil in Rutherford’s experiments. Beta particles are fast-

moving electrons released from the nucleus of an atom, each one carrying its

characteristic –1 charge.

The penetrating powers of radioactivity are put to many uses in modern life,

including killing cancer cells, testing the integrity of welds in metal, and looking

for hairline cracks in aircraft airframes. We will discuss the concepts and applica-

tions of radioactivity much more fully in Chapter 21.

HERE’S WHAT WE KNOW SO FAR

■

Atoms can be broken down into smaller parts. Those parts include the proton,

neutron, and electron.

■

The proton and neutron occupy the center of the atom, called the nucleus.

■

The electrons occupy the space around the nucleus.

■

Protons and electrons have opposite charges; protons are positively charged

and electrons are negatively charged.

■

The total mass of the atom is the sum of all of the particles that make up the

atom.

■

Radiation is a result of the decay of atoms. Different decay products exist, such

as the alpha particle, the beta particle, and the gamma ray.

Through the work we’ve just described, along with that done by other scien-

tists of the time, we know that the nucleus of an atom contains the protons and

neutrons. The proton has a tiny positive electrical charge (1.6 × 10

−19

coulombs)

and a similarly minute mass (1.6726 × 10

−27

kg). Neutrons do not carry a charge

and are a tiny bit more massive than the protons (1.6749 × 10

−27

kg). The elec-

trons travel around the remaining space in the atom. Although they are about

2000 times less massive (9.1094 × 10

−31

kg) than the particles in the nucleus,

they occupy the majority of the atomic volume, as shown in Figure 2.18). The

electrons also carry a negative electrical charge, equal in magnitude to, but oppo-

site in sign from, that on the proton. To simplify counting charges, we often re-

port the charge on the proton as +1 and that on the electron as –1 (Table 2.3).

This model of the structure of the atom is sufficiently useful for us to under-

stand the main differences among atoms and the most fundamental principles of

chemical change. However, we must realize that it is just a model. Chemists use

various models, which represent important aspects of reality in useful ways, but

none of their models is likely to be entirely correct. Yet each model has a place in

the toolbox of the chemist. We can use this model of the atom whenever it is most

useful; and we can use more sophisticated models, about which we’ll learn later,

whenever those would be most useful. What model we use depends on what

questions we are trying to answer.

2.3 The Structure of the Atom 55

Proton

Neutron

Nucleus

Space

occupied

by electrons

FIGURE 2.18

The atom is mostly empty space. The

nucleus constitutes about 1/10,000 the

diameter of the atom.

Subatomic Particles

Particle Mass amu* Charge

Electron 9.1094 × 10

−31

kg 5.486 × 10

−4

−1

Proton 1.6726 × 10

−27

kg 1.0073 +1

Neutron 1.6749 × 10

−27

kg 1.0087 0

*The atomic mass unit (amu) is an arbitrary unit used to set the masses reported in the

periodic table. We will discuss it in the next section.

TABLE 2.3

2.4 Atoms and Isotopes

The periodic table of the elements is arguably the single most important practical

outcome in the history of chemistry. Because it is an essential tool for practicing

chemists as well as chemistry students, it is located on the inside front cover of

this book for your easy reference.The periodic table lists the atoms of just over

90 elements that are known to occur naturally, as well as a smaller number of

heavy elements that have been synthesized.

One of the great beauties of the periodic table is that all of the atoms of the el-

ements in the table are constructed of the same building blocks: protons and neu-

trons surrounded by a sea of electrons. Are the numbers and types of particles

important in constructing an atom? The short answer is a definite “yes.” The

numbers of protons, neutrons, and electrons define each individual atom. The

identity of the atom is determined by the quantity of protons in the nucleus,

which is known as the

atomic number (Z). For instance, all hydrogen atoms have

one proton (Z = 1), all helium atoms have two protons (Z = 2), and all iron

atoms have twenty-six protons (Z = 26). Just as your university identification

number uniquely identifies you at your school, the atomic number unequivocally

identifies a specific element in chemistry. Potassium has an atomic number of 19,

and any element with nineteen protons must be potassium.

The number of electrons in an electrically neutral atom is equal to the number

of protons and, therefore, to the atomic number. However, when combined with

atoms of other elements, an atom can gain or lose electrons to form a charged

entity we call an

ion. Although the number of electrons that an atom contains

changes, the atomic number—the number of protons it contains—remains the

same. For example, the sodium ion shown in Figure 2.19 is still sodium, even

though its electron count is no longer the same as that of a neutral sodium atom.

The key question is

How many protons does the atom contain? The number of pro-

tons always identifies the element.

A positive charge indicates that there are more protons than electrons on the

ion. We typically refer to this type of ion as a

cation (pronounced CAT-ion). Con-

versely, a negative charge indicates that there are more electrons than protons.

This type of ion is known as an

anion (pronounced AN-ion). If we know the

charge and the atomic number of an ion, we can determine the number of elec-

trons that make up the ion.

56 Chapter 2 Atoms: A Quest for Understanding

2 electrons

2 protons

2 neutrons

He

Protons

Li

++

+3

+

Electrons

Net charge = +3 – 3 = 0

––

–3

–

Protons

Li

+

++

+3

+

Electrons

Net charge = +3 – 2 = +1

––

–2

Na Na

+

FIGURE 2.19

The sodium atom and the sodium ion. Both of these combina-

tions of electrons, protons, and neutrons are sodium, despite the

difference in the number of electrons.

We call the sum of the number of protons and neutrons the mass number (A)

of the atom. The number of neutrons (n) in a particular atom can be calculated

by subtracting the atomic number from the mass number:

A − Z = n

These basic components of the atoms can be written using the chemist’s

shorthand of

nuclide notation, as shown in Figure 2.20. Nuclide notation lists the

symbol for the element, accompanied by the atomic number and the mass num-

ber of the atom.

Rather than requiring that we write numbers for all of the particles that make

up an atom or ion, nuclide notation provides a quick way to convey the quantity of

subatomic particles to other scientists. An alternative way to quickly write the

number of particles is to write the name of the element, followed by the mass num-

ber of the element. For example, when we wrote “carbon-12” earlier in this chap-

ter, we were indicating an atom containing 6 protons, 6 neutrons, and 6 electrons.

Isotopes

Let’s reexamine the radiocarbon dating of the Dover Boat. From that discussion

we learned that there must be at least two different types of carbon atoms. The

discovery of a biosignature in a rock formation is related to this fact as well. What

is different about the carbon atoms?

All atoms of an element have the same number of protons, but the number of

neutrons that make up the nucleus of an atom can differ. Atoms of the same ele-

ment must have the same atomic number (the same number of protons); other-

wise, they would be different elements. However, if they differ in the number of

neutrons they contain, they are known as

isotopes. There are actually three com-

mon isotopes of carbon, the most abundant (98.93%) of which is carbon-12.

Carbon-13 is another nonradioactive isotope of the element carbon; it makes up

only a small amount (1.07%) of the carbon atoms in the universe. The carbon-14

isotope (2 × 10

−10

% of all carbon atoms) is radioactive and is the element used

to determine the age of ancient artifacts.

2.4 Atoms and Isotopes 57

3

7

A

A – Z = number of neutrons

7 – 3 = 4 neutrons

Z

Li

Z

E

A

Mass

number

Atomic

number

Element

symbol

FIGURE 2.20

Nuclide notation.

The number of neutrons in a particular

atom can be determined by subtracting

the number of protons (Z) from the

atomic mass number (A).

6

C

12

6

C

13

6

C

14

Isotopes of carbon.

Many examples of isotopes exist among the elements of the periodic table. In

fact, it is rare for an element not to have isotopes. Some of the isotopes of hydro-

gen, carbon, and oxygen are shown in Table 2.4 in nuclide notation. Also included

in the table is their relative natural abundance. For example, 99.985% of all hy-

drogen atoms are hydrogen-1, 0.015% are deuterium (the same single proton as

hydrogen, but with one neutron), and only 10

−18

% of them are tritium (one pro-

ton and two neutrons).

Many nuclei that have either too many or too few neutrons to be energetically

stable tend to give off energy and particles to become stable. This is the reason for

the radioactivity of carbon-14.

Video Lesson: Modern Atomic

Structure

Tutorial: Isotopes