Kelter P., Mosher M., Scott A. Chemistry. The Practical Science

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

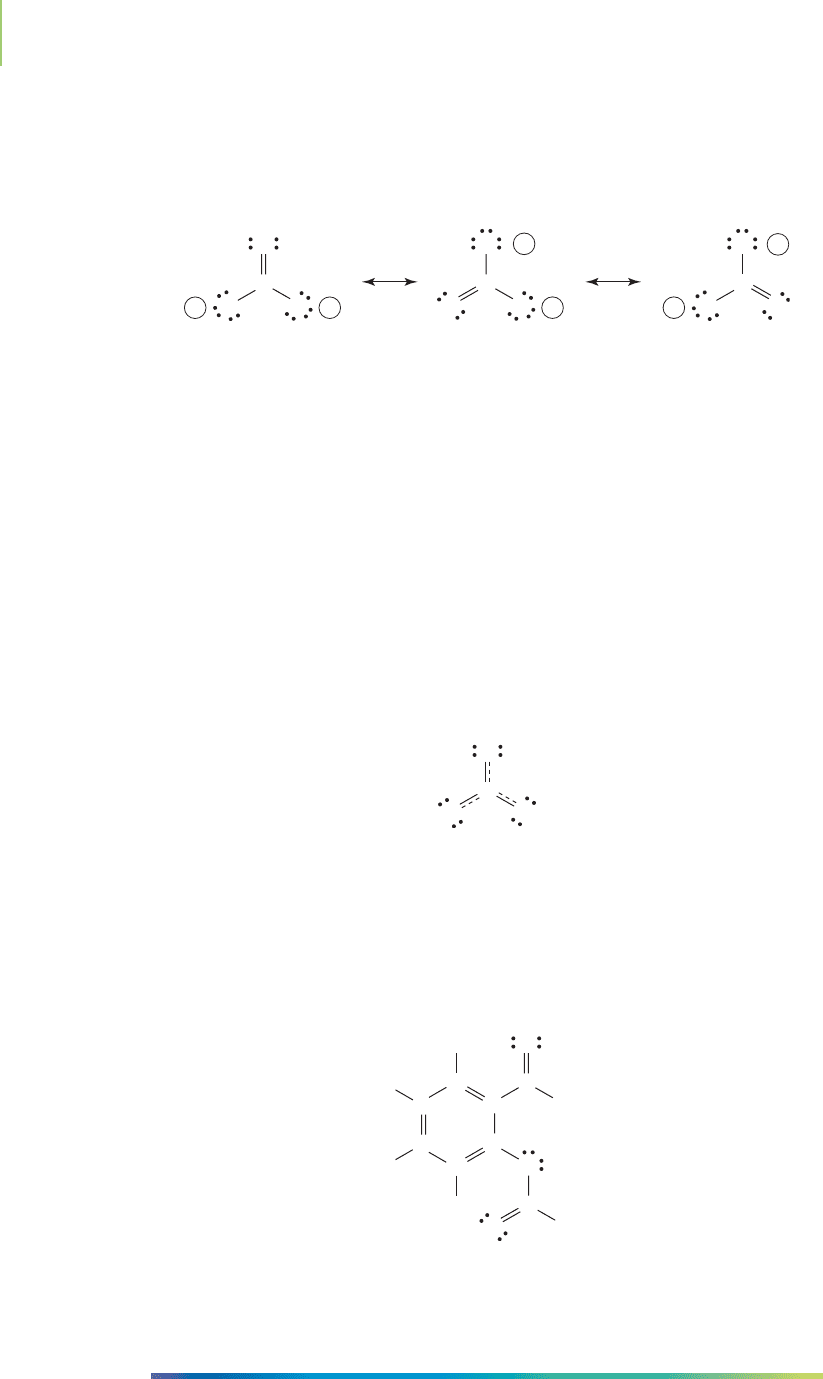

We could have shown the lone pair on one of the other atoms involved with

satisfying the octet rule for carbon. In fact, there are two other structures that also

seem to be satisfactory Lewis dot structures. Turn your textbook from “high

noon” to 4 o’clock (or “120 degrees”) to verify this fact.

Which one is correct?

Each one of the three structures is an equally good representation of the carbon-

ate ion. The only difference among these models is that the positions of the elec-

trons have changed. The relative positions of the atoms did not change.

A

resonance structure is a model of a molecule in which the positions of the

electrons have changed, but the positions of the atoms have remained fixed. All of

the resonance structures for a molecule are correct ways to draw the Lewis dot

structure. We show the relationship among these resonance structures by draw-

ing a double-headed arrow between them. However, we shouldn’t consider a single

resonance structure to be a discrete entity. Because the only difference is the loca-

tion of the electrons, the resonance structures must be considered together as the

model of the molecule. A combination of all of the resonance structures is the best

model. The resulting model is called the

resonance hybrid. The resonance hybrid

is an equal or unequal (based on experimental evidence) combination of all of

the resonance structures for a molecule. For the carbonate ion, the resonance hy-

brid looks like this:

Instead of full charges on two of the oxygen atoms, a partial charge (about

−0.67) exists on each of the oxygen atoms that adds up to the overall −2 charge

for the ion. Partial double bonds (1.33 times as much of a bond as a single bond)

are drawn to show how the three resonance structures combined to make one

resonance hybrid.

We now have a sufficiently complete model to draw the Lewis dot structure

for aspirin, or acetylsalicylic acid (C

9

H

8

O

4

).

We note that all the octets are filled and that the formal charges of all of the atoms

in the structure sum to 0.

HERE’S WHAT WE KNOW SO FAR

■

The energy of an ionic bond is related to the charges on the ions and the dis-

tance separating the ions.

OH

CH

3

C

C

C

C

H

H

H

C

C

H

C

O

C

O

O

C

O

O

O

C

O

O

O

C

O

O

O

C

O

O

O

11

1

1 1

1

328 Chapter 8 Bonding Basics

Application

■

Lewis dot structures can be used to draw a model of a compound. The octet

rule drives our prediction of the best model for a compound. The resulting

model represents the locations of electrons and atoms in a compound.

■

Electrons are shared in covalent bonds.

■

The atoms in a covalent bond are held at a distance that reflects the attraction

for the bonding electrons and the repulsion of the adjacent nuclei.

■

The Pauling electronegativity scale is the most widely used among several that

indicate the polarization of bonding electrons.

■

We can classify covalent bonds as polar and nonpolar, depending on the elec-

tronegativity difference between the atoms in the bond.

■

Formal charges help us to select the most likely structure among viable

alternatives.

■

Resonance structures exist in a molecule when electrons can shift positions

among different atoms while the positions of the atoms remain fixed.

Exceptions to the Octet Rule

In 1954, Robert Borkenstein, a captain in the Indiana State Police, developed a

Breathalyzer like that shown in Figure 8.17. A device similar to this was first used

by police to determine alcohol levels in drunk drivers. The Breathalyzer contains

potassium dichromate and sulfuric acid that converts exhaled ethanol

(CH

3

CH

2

OH) into acetic acid (CH

3

COOH). The conversion causes the chemical

reagent in the Breathalyzer to change color from yellow-orange to blue-green.

The rest of the compounds in the reaction are colorless. After the test is per-

formed, the presence of the blue-green color indicates that the suspect has been

drinking. What is the Lewis dot structure for sulfuric acid?

2K

2

Cr

2

O

7

+ 8H

2

SO

4

+ 3CH

3

CH

2

OH n 2Cr

2

(SO

4

)

3

+ 2K

2

SO

4

+ 3CH

3

COOH + 11H

2

O

hh

Yellow-orange Blue-green

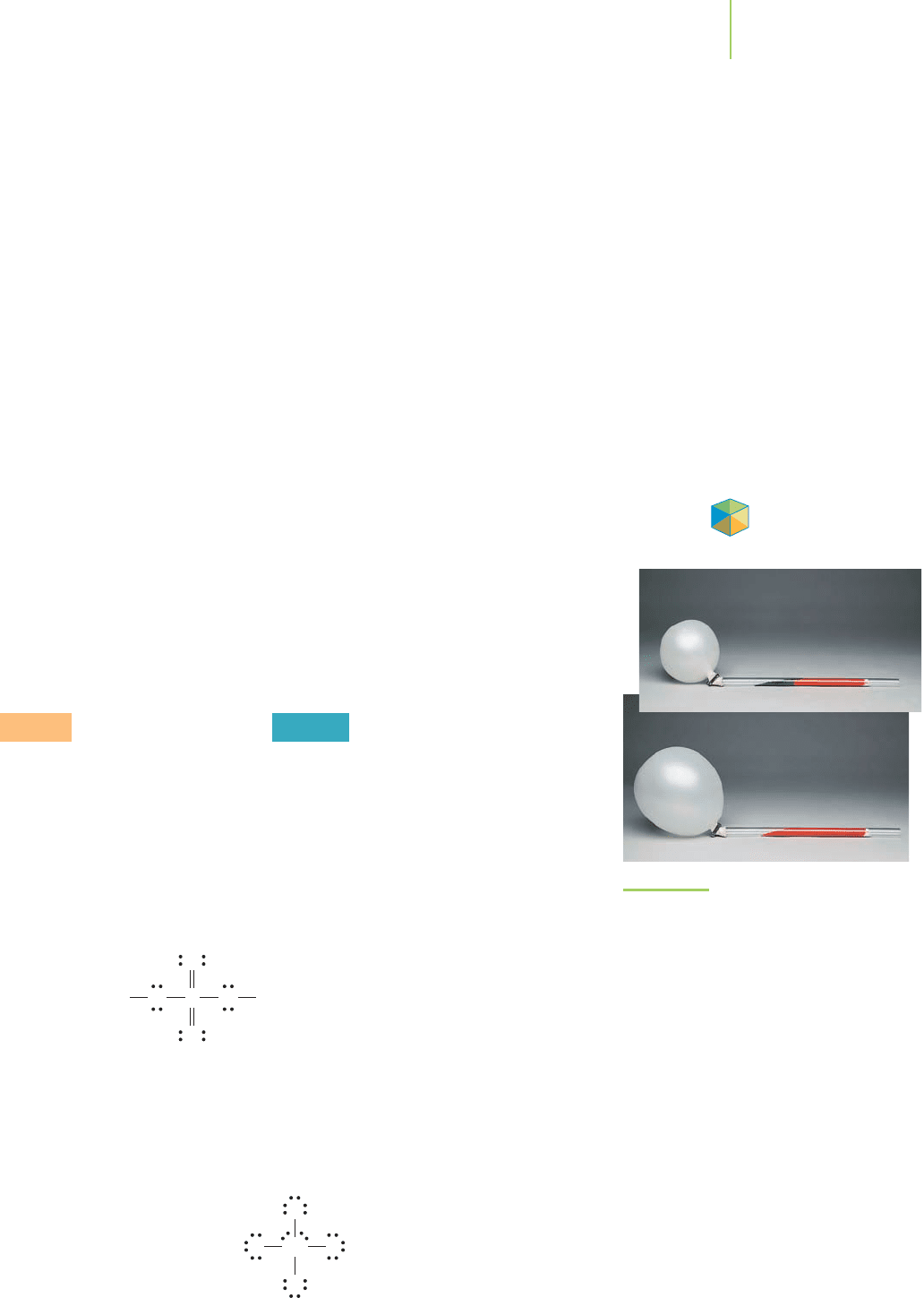

Drawing the structure, we see that the sulfur atom has the smallest formal charge

when there are six bonds from the sulfur to the adjacent atoms. Can this be

correct? There is still debate about the existence of two SPO bonds in sulfuric

acid (rather than single bonds to all atoms, which gives decidedly nonzero formal

charges—can you prove this?) but the structure does seem to fit our

understanding of Lewis dot structures and formal charges. Some exceptions to the

octet rule must be considered if we are to accept this Lewis dot structure model.

In 1962, Neil Bartlett, then at the University of British Columbia, reported the

first inert gas compound (XePtF

6

). This was quickly followed by reports of other

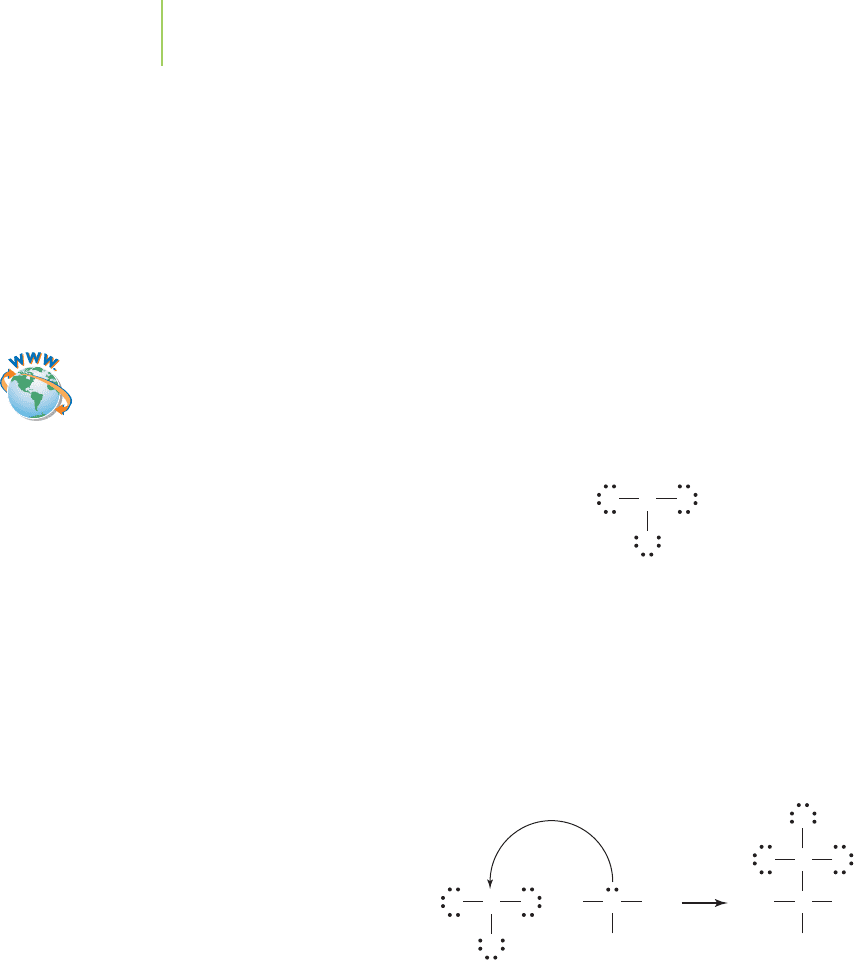

inert gas compounds. For example, researchers at the Argonne Laboratories pre-

pared xenon tetrafluoride (XeF

4

). In the Lewis dot structure of XeF

4

, the xenon

atom has twelve total electrons around it. What are the formal charges on the

atoms in this model?

FF

F

F

Xe

Formal charges

F.C. (S) 6 6 0 0

F.C. (O) 6 2 4 0

SHH

O

O

O O

8.3 Covalent Bonding 329

FIGURE 8.17

The Breathalyzer. This device can be

used to estimate how much alcohol a

person has consumed. Shown here is

a demonstration of the process that

occurs in the instrument.

How can sulfur and xenon have more than eight electrons around them in the

Lewis dot structure? Consider the orbitals that are available to valence electrons.

In the valence shell of oxygen, for example, there are 2s and 2p orbitals. In the

valence shell for sulfur, however, there are 3s,3p, and 3d orbitals. The 3s and 3p

orbitals contain electrons. A higher-energy unfilled set of orbitals (the 3d or-

bitals) can be used if needed to hold extra electrons. This means that the sulfur

atom in sulfuric acid (H

2

SO

4

) can have eight electrons in the 3s and 3p orbitals

and place the extra four electrons in the previously empty 3d orbitals. Xenon, in

XeF

4

, can also accommodate the extra electrons by placing them in the empty

5d orbitals. This is a general rule for atoms of the third row and higher of the pe-

riodic table. Atoms can have

expanded octets. Often this occurs when the valence

electron shell includes unfilled d orbitals.

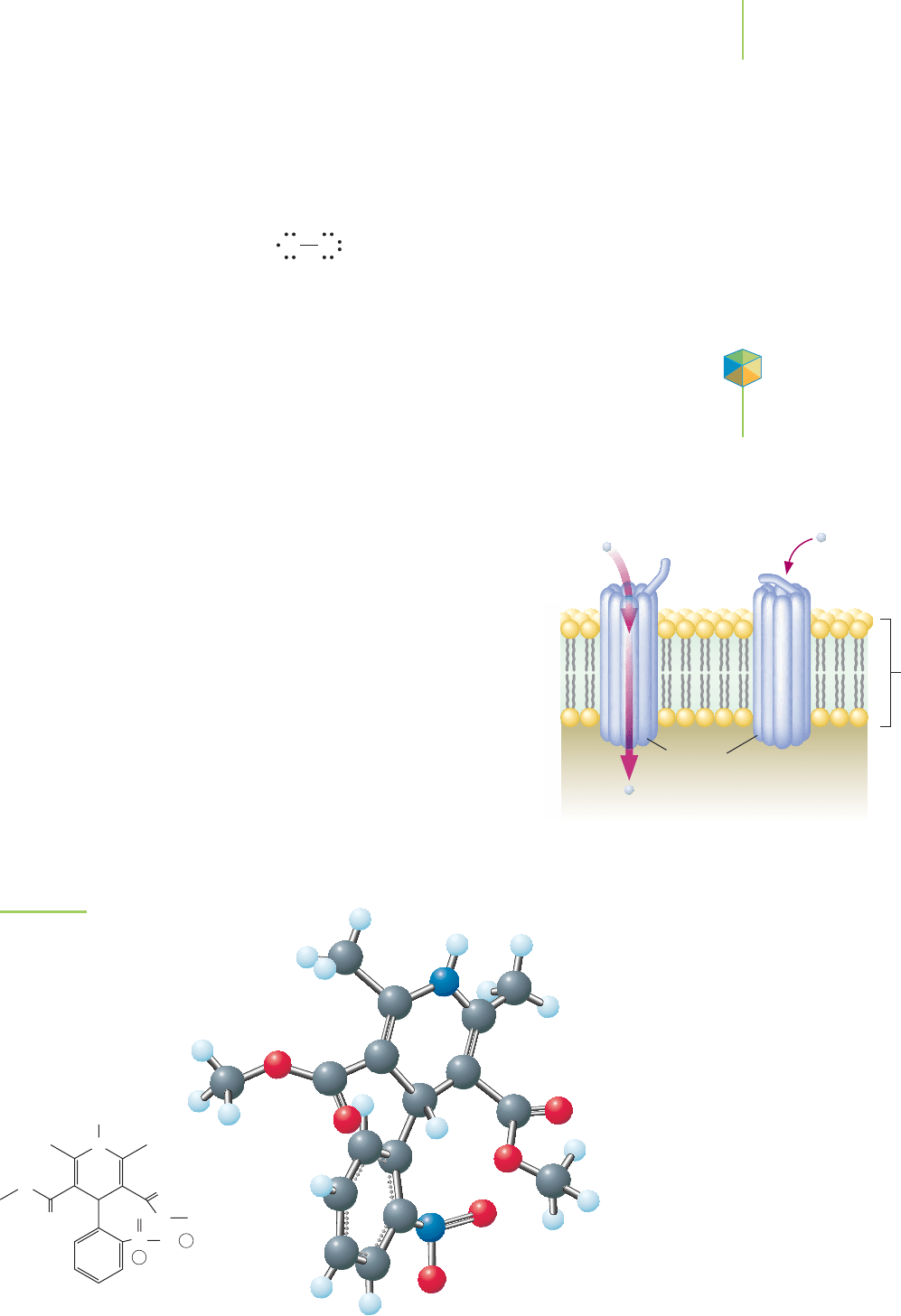

Boron trifluoride (BF

3

) is an example of a compound in which the central

atom has fewer than eight electrons around it. What is the formal charge on the

boron atom in BF

3

?

Even though the formal charges on each atom indicate that the Lewis dot struc-

ture is satisfactory, the boron atom does not satisfy the octet rule. We’d predict

this molecule, then, to be quite reactive with molecules that are electron-rich. In

fact, boron trifluoride reacts quite violently with molecules containing a lone pair

of electrons (such as water and ammonia). The bond that forms is an example of

a

coordinate covalent bond. This bond is special because both electrons that make

the bond were donated from just one of the two atoms involved. However, after

the bond is made, it is indistinguishable from a normal covalent bond.

The coordinate covalent bond is fairly common, particularly in reactions in-

volving acids and bases. For instance, when we write the equation describing the

dissolution of gaseous HCl in water, we describe the formation of a coordinate

covalent bond.

HCl(g) + H

2

O(l) n H

+

(aq) + Cl

−

(aq) + H

2

O(l) n H

3

O

+

(aq) + Cl

−

(aq)

The hydronium ion (H

3

O

+

) contains a coordinate covalent bond between the

oxygen and one of the hydrogen atoms. As the strong hydrochloric acid dissolves

in the water, it ionizes into H

+

and Cl

−

. The hydrogen cation combines with a

pair of electrons from the oxygen of water, and a covalent bond results. In the

end, that bond is indistinguishable from the other OOH bonds in the hydro-

nium ion.

Superoxide (O

2

−

) is an extremely reactive anion that can cause severe damage

to living tissue. To protect itself, the body has evolved an enzyme, superoxide dis-

mutase, that quickly hunts down and destroys superoxide. What is the Lewis dot

structure for superoxide, which is more accurately called the dioxygen (−1) ion?

In drawing the structure, we note the presence of an odd number of total va-

lence electrons. Because bonding electrons and lone-pair electrons are pairs of

FF

F

B

FF

H

B

HHN

H

HHN

F

FF

F

B

330 Chapter 8 Bonding Basics

Video Lesson: Electronegativity,

Formal Charge, and Resonance

electrons, an odd number of total valence electrons in a Lewis dot structure im-

plies that there is a lone unpaired electron (called a

radical). The existence of a rad-

ical electron in a molecule often makes a molecule quite reactive. By placing a

radical electron in a Lewis dot structure, we generate an atom that doesn’t com-

plete an octet. Note the location of the formal charge in superoxide:

Energy of the Covalent Bond

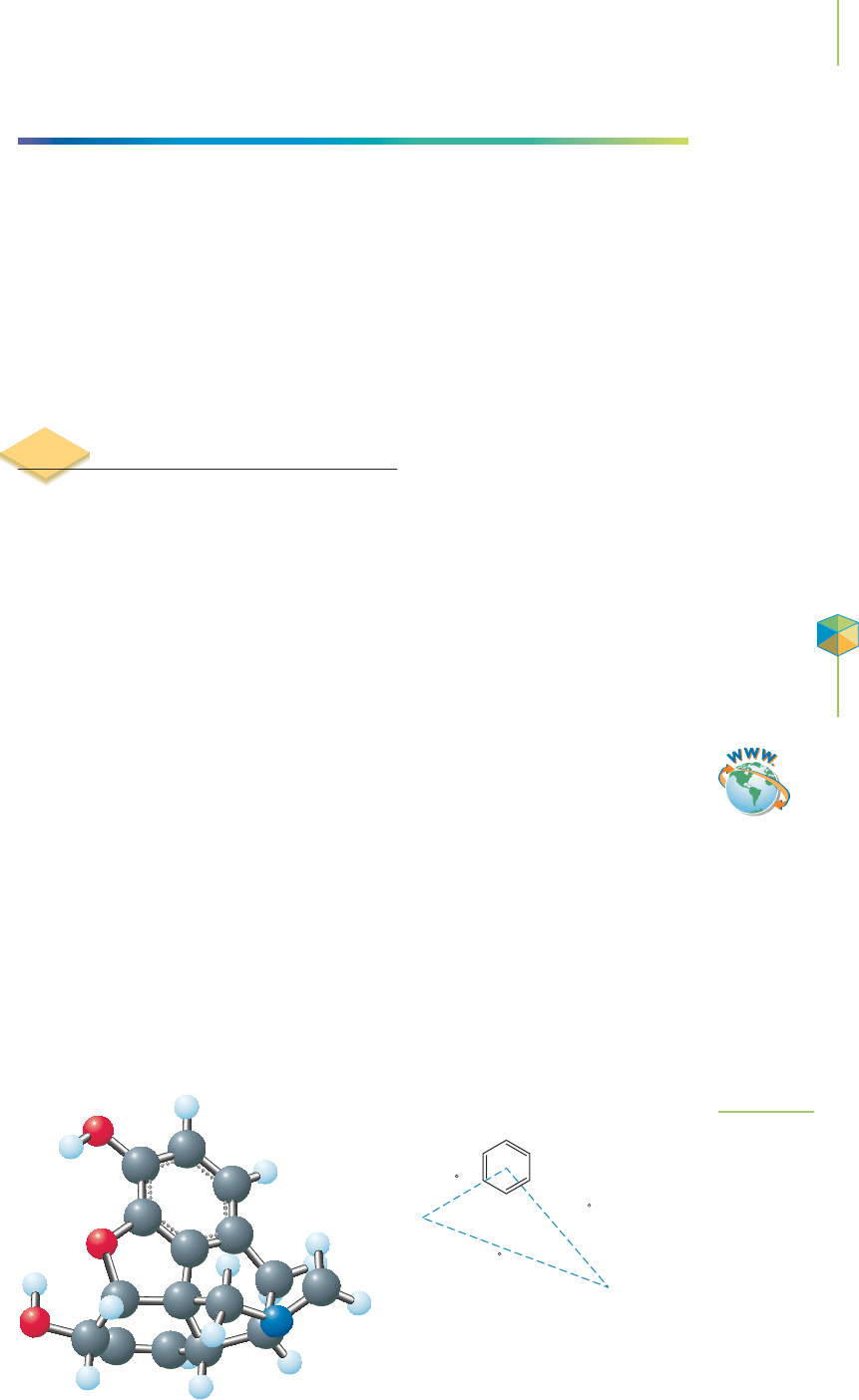

Angina, a sudden pain in the chest, is a symptom of a heart that doesn’t have an

adequate flow of oxygenated blood to work properly. Treatments for this type of

heart disease require administration of drugs that dilate the coronary artery and

increase the flow of blood. Calcium channel blockers are a class of medicines used

to treat this disease. These compounds fit neatly into “pockets” within proteins

that control the flow of calcium ions into muscle cells. As the rate at which cal-

cium ion passes into the heart muscle is greatly reduced, the heart relaxes and its

arteries dilate. The result is a heart that has enough oxygen to function ade-

quately. One problem with calcium channel blockers is that the body

breaks specific bonds in these drugs and makes them into biologi-

cally inactive compounds (i.e., the drugs are rapidly metabolized).

For example, nifedipine, a common calcium channel blocker, persists

in the body for only 4–8 hours (Figure 8.18). Patients must continu-

ously take the drug to prevent heart damage due to lack of oxy-

genated blood.

Medicinal chemists are interested in designing drugs that are sim-

ilar in structure to nifedipine but resistant to metabolism. To do this,

the medicinal chemist must make a compound that fits into the same

pocket in the protein but contains bonds that do not break as easily

as nifedipine. The shape of the new drug, then, must be very similar

to the shape of nifedipine. The shape can be determined by building

a model of the compound.

How do scientists know which bonds are

susceptible to reactions within the body?

Because reactions break

O O

8.3 Covalent Bonding 331

Application

C

HEMICAL ENCOUNTERS:

Calcium Channel

Blockers

Outside of cell

Inside of cell

Cell

wall

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Calcium

channel

Open Closed

H

N

N

O

O

O

O

O

+

–

O

FIGURE 8.18

Nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker

prescribed for some patients with heart

trouble. Carbon atoms are black, oxygen

atoms are red, nitrogen atoms are blue,

and hydrogen atoms are white.

The heart muscle can relax when the flow of

calcium ions to the heart is reduced. Calcium

channel blockers fit into the pockets of proteins

that control calcium intake, reducing the flow of

calcium to the heart.

bonds, the answer to this question is related to the strength of the different bonds

in a compound.

How strong are covalent bonds? Is there a relationship between the type of

bond and the strength of the bond? Is a multiple bond stronger than a single

bond? To answer these questions, we must rely on our ability to estimate the

amount of energy that it takes to dissociate a bond. The

enthalpy of bond dissoci-

ation

(

diss

H), or, simply, the bond dissociation energy, is the energy required to

break 1 mol of bonds in a gaseous species. The equation that describes bond dis-

sociation is shown below.

XOY(g) n X(g) +Y(g)

Bond breakage requires energy, so bond dissociation enthalpies are always en-

dothermic and the values for bond energy will always have a positive sign.

Table 8.6 lists the values for several important bonds. From the values in the table,

we note that single bonds require less energy to break than their corresponding

double or triple bonds. Compare the COC single bond (

diss

H = 347 kJ/mol),

aCPC double bond (

diss

H = 614 kJ/mol), and a CqC triple bond (

diss

H =

839 kJ/mol). Also note from the table that the length of the covalent bond shrinks

as we go from a single to a double to a triple bond for a given element or pair of

elements. For diatomic molecules, the bond dissociation energy can be measured

directly in the laboratory. The process is a little different for atoms that do not

form diatomic molecules. Other atoms close to the bond influence how electrons

are distributed in a bond and affect the energy it takes to break the bond. The data

in Table 8.6, then, are average bond dissociation energies.

The overall enthalpy change of a reaction (

rxn

H) can be estimated using

bond dissociation energies. Because the enthalpy change (a state function, inde-

pendent of path) in a reaction is the sum of all of the energy as heat added to the

system minus the sum of all of the energy as heat removed from the system at

constant pressure, the enthalpy change of a reaction can be determined by mea-

suring the enthalpies of bond breakage and bond formation. Breaking a bond

requires an addition of energy to the system. Forming a bond results in a release

of energy from a system. If we add up all of the enthalpies for the bonds that are

332 Chapter 8 Bonding Basics

Average Bond Dissociation Energies and Bond Lengths for Some Common Covalent Bonds

Energy Length Energy Length Energy Length

Bond (kJ/mol) (pm) Bond (kJ/mol) (pm) Bond (kJ/mol) (pm)

HOH 432 75 NOH 391 101 FOF 154 142

HOF 565 92 NOF 272 136 FOCl 253 165

HOCl 427 127 NOCl 200 175 FOBr 237 176

HOBr 363 141 NOBr 243 189 FOI 273 191

HOI 295 161 NON 160 145 ClOCl 239 199

COH 413 109 NPN 418 125 ClOBr 218 214

COF 485 135 NqN 941 110 ClOI 208 232

COCl 339 177 OOH 467 96 BrOBr 193 228

COBr 276 194 OOF 190 142 BrOI 175 247

COI 240 214 OOCl 203 172 IOI 149 267

COC 347 154 OOI 234 206 SOH 363 134

CPC 614 134 OOO 146 148 SOF 327 156

CqC 839 120 OPO 495 121 SOCl 253 207

CON 305 143 COO 358 143 SOBr 218 216

CP

N 615 138 CPO 745* 120 SOS 226 205

CqN 891 116 CqO 1072 113

*CPO bond energy in CO

2

is 799 kJ/mol.

TABLE 8.6

Video Lesson: Bond Properties

The enthalpy change of the reaction is calculated on the basis of this information.

The enthalpy change for the reaction is negative. When the reaction occurs, heat

is released.

1 mol CPO bonds × 745 kJ/mol =+745 kJ

2 mol COCl bonds × 339 kJ/mol =+678 kJ

2 mol OOH bonds × 467 kJ/mol =+934 kJ

Total bonds broken =+2357 kJ

2 mol HOCl bonds × (−427 kJ/mol) =− 854 kJ

2 mol CPO bonds × (−799 kJ/mol) =−1598 kJ

Total bonds formed =−2452 kJ

Total energy absorbed =+2357 kJ

Total energy released =−2452 kJ

Net energy change (H) =− 95 kJ

8.3 Covalent Bonding 333

broken and subtract all the enthalpies for the bonds that are formed, we can ar-

rive at the enthalpy change of the reaction.

rxn

H = (

diss

H)

breaking bonds

− (

diss

H)

making bonds

To use this equation, we have to know which bonds are broken and which are

formed in a reaction. This is where Lewis dot structure models come in. By ex-

amining the Lewis dot structures of the products and reactants, we can determine

which bonds are broken and which are formed. Then we can tally up the energy

required to break all of the bonds in the reactants, and all of the energy released

when the bonds in the products form. The difference between the two is the en-

thalpy change for the reaction. As we go through this process, we must keep in

mind that using bond enthalpies to calculate the approximate enthalpy change in

a reaction is strictly a mathematical tool; chemical reactions do not actually occur

by breaking bonds into individual atoms and then having the atoms combine in

different configurations. The actual chemistry is much more subtle and is con-

tinuous, consisting of a series of energy changes along the way as bonds are

broken and formed. We will discuss the subtleties of reaction mechanisms in

some detail in Chapter 15.

The reaction of water and phosgene illustrates how we use this handy tool in

the chemist’s toolbox to determine approximate bond enthalpy changes during

reactions:

H

2

O(l) + COCl

2

(g) n CO

2

(g) + 2HCl(aq)

We must draw the reaction and the Lewis dot structure for each compound. In

this reaction we break one CPO bond, two COCl bonds, and two OOH bonds,

and form two CPO bonds and two HOCl bonds (Figure 8.19).

Cl C

C

++Cl

Cl

Cl

HCl

H

H

H

Cl

HO

O

O

H

COCl

2

+ H

2

OCO

2

+ 2HCl

OCO

O

→

FIGURE 8.19

Reaction of phosgene with water. Energy

is added to the system to break all of the

bonds in the reactants. Energy is released

when the bonds in the products are

formed.

Video Lesson: Using Bond

Dissociation Energies

334 Chapter 8 Bonding Basics

The difference between the energy absorbed and the energy released =net energy

change

(H)= − 95 kJ

.

EXERCISE 8.8 Calculating the Enthalpy of Combustion

Calculation of the enthalpy of combustion can be useful in determining whether

a compound could make a good fuel. Calculate the enthalpy of combustion for

methane (found in natural gas) using bond dissociation enthalpies.

CH

4

(g) + 2O

2

(g) n CO

2

(g) + 2H

2

O(g)

First Thoughts

This problem requires that we first draw the Lewis dot structures of all of the com-

pounds in the reaction. After correctly drawing the structures, we can determine the

type of bond that breaks or forms.

What sort of answer do we expect? We know

that the combustion of methane is highly exothermic, supplying heat to countless

homes as natural gas is consumed in heaters.

Solution

4 mol COH bonds × 413 kJ/mol =+1652 kJ

2 mol O

2

bonds × 495 kJ/mol =+990 kJ

Total bonds broken =+2642 kJ

2 mol CPO bonds × (−799 kJ/mol) =−1598 kJ

4 mol OOH bonds × (−467 kJ/mol) =−1868 kJ

Total bonds formed =−3466 kJ

Total energy absorbed =+2642 kJ

Total energy released =−3466 kJ

Net energy change (H) =−824 kJ

The reaction is exothermic. Heat is given off during the combustion of methane, so

our answer makes sense.

Further Insight

Calculations such as this can be used to find a more efficient alternative fuel source.

For example, toluene (C

7

H

8

, a major component of gasoline) releases 3933 kJ/mol,

or 43 kJ/g, during its combustion. Based on this information, methane, releasing

824 kJ/mol, or about 52 kJ/g, gives off nearly 20% more energy as heat than does

toluene on a gram-to-gram basis. The best alternative on a gram-to-gram basis may

well be hydrogen, for which the energy released is about 280 kJ/mol, or 140 kJ/g!

This is one of several reasons why hydrogen is being developed as an alternative to

fossil fuels.

PRACTICE 8.8

Calculate the enthalpy change for the reaction of methanol and hydrogen bromide.

CH

3

OH(aq) + HBr(aq) n CH

3

Br(aq) + H

2

O(l)

See Problems 72–74.

8.4 VSEPR—A Better Model 335

HERE’S WHAT WE KNOW SO FAR

■

Atoms can exceed the octet rule if they have available d orbitals in their valence

shell.

■

The enthalpy of a reaction can be determined from the energy absorbed dur-

ing bond breakage or released during bond formation.

■

We can combine the net changes in energy from bond-breaking and bond for-

mation because bond enthalpy is a state function.

■

Between two particular atoms, breaking multiple bonds requires more energy

than breaking single bonds.

8.4 VSEPR—A Better Model

Knowing the strength of bonds in molecules such as nifedipine is useful for de-

termining information about the biological processes that break down the mole-

cule and render it useless as a pharmaceutical. However, the three-dimensional

structure of molecules is even more important in determining the biological

activity of the compound.

For instance, the opium poppy has long been used for its ability to alleviate

pain. The ancient Sumerians in 3400

B.C. enjoyed its use so much that they

referred to it as the “joy plant.” It wasn’t until 1827 that the active ingredient,

morphine, was isolated from the poppy and produced commercially. The anal-

gesic effects of morphine are one of the reasons why it continues to be used today

to treat postoperative pain. However, morphine has serious side effects, which in-

clude respiratory depression, constipation, muscle rigidity, physical dependence,

and a high potential for abuse. The medicinal chemist, the pharmacognocist, and

the biochemist have been working together to try to prepare compounds that

have beneficial properties similar to those of morphine but lack its harmful side

effects. To develop a compound with a similar mode of action, they must deter-

mine not only the shape of the morphine molecule but also the shape of the

active site on the receptor (the biological molecule to which morphine binds in

the human body). Recent efforts have determined that the shape of the active

site must accommodate a structure with particular dimensions, as shown in Fig-

ure 8.20. Because there are so many different probable locations for the active site,

computers were used to complete most of the work mapping the shape of the

active site on the receptor.

Application

C

HEMICAL

ENCOUNTERS:

Focus on Morphine

(A)

(B)

(C)

N

4.5 A

7.6 A

Hydrophobi

c

region

6.7 A

+

FIGURE 8.20

The structure of morphine and the opioid

receptor binding requirements.

Tutorial: VSEPR Theory

Lewis dot structures would not be very helpful in determining the shape of

the morphine molecule or the active site in a case like this.

What are the limita-

tions of the Lewis dot structure models?

Does a Lewis dot structure tell us anything

about the three-dimensional shape of a molecule? The Lewis dot structure might

lead us to believe that all molecules are flat, planar structures. But people, gerbils,

roses, and guitars all occupy three dimensions, and all of these things are com-

posed of molecules, so it makes sense that molecules occupy three-dimensional

space. Even so, the idea of a “three-dimensional molecule” was fervently debated

when it was first introduced. Many chemists could not believe that molecules

would be anything other than flat.

The orientation of atoms in a molecule plays a major role in determining its

properties. For instance, the Lewis dot structure of water (H

2

O) can be drawn in

two different ways. In one, it is a linear molecule, in the other, it is bent. Which is

the correct way to draw water? If water were a linear molecule, it would have

completely different properties from those we observe. The consequences of this

slight change would have drastic effects in the real world. An ocean of linear water

molecules would dissolve oxygen quite well and probably kill most of the life in

336 Chapter 8 Bonding Basics

In the 1800s, Jacobus Henricus van’t Hoff

(Dutch physical chemist, 1852–1911)

and Achille Le Bel (French chemist, 1847–1930) inde-

pendently came to the conclusion that molecules must

exist as three-dimensional structures. Despite the fact

that established thought on the structure of molecules

asserted that they were flat, these researchers advanced

their theory for public and professional scrutiny. Using

careful theoretical considerations of well-studied mole-

cules (such as tartaric acid), van’t Hoff concluded that

molecules had to occupy a three-dimensional structure.

It was a very compelling argument for some. For others,

it was heresy.

Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe (1818–1884),

one of the prominent German chemists of the time,

vehemently discounted the theory of three-dimensional

molecules. His flat models seemed to provide the best

explanation for the properties that he observed. He took

such an aggressive stance on this issue that he attempted

to discredit van’t Hoff and his colleagues. Without exper-

imenting to determine whether the theory was correct,

he published letters in prominent chemistry journals

just to tarnish the new theory. In one of his published

articles, Kolbe wrote as follows:

I have recently published an article giving as one of the

reasons for the contemporary decline of chemical research

in Germany the lack of well-rounded as well as thorough

chemical education. Many of our chemistry professors

labor with this problem to the great disadvantage of our

science. As a consequence of this, there is an overgrowth

of the weed of the seemingly learned and ingenious but in

reality trivial and stupefying natural philosophy. This nat-

Issues and Controversies

Flat molecules and ethics in science

ural philosophy, which had been put aside by exact sci-

ence, is at present being dragged out by pseudoscientists

from the den which harbors such failings of the human

mind, and is dressed up in modern fashion like a freshly

rouged prostitute whom one tries to smuggle into good

society where she does not belong.

A J. H. van’t Hoff of the Veterinary School in Utrecht

has, as it seems, no taste for exact chemical investigation.

He has thought it more convenient to mount Pegasus

(apparently on loan from the Veterinary School) and to

proclaim in his “La chimie dans l’espace” how, during his

bold flight to the top of the chemical Mount Parnassus,

which he ascended in his daring flight, the atoms appeared

to him to have grouped themselves throughout the

Universe.

Journal für praktische Chemie, 1877

The responsibility of scientists to maintain objectiv-

ity in the methodical practice of science carries over into

the public realm as well. To practice science with less

than complete objectivity results in professional ridicule

and increased public skepticism. Tens of thousands of

chemistry-related articles are published worldwide each

year. Highly regarded journals use the system of prepub-

lication “peer review,” in which knowledgeable scientists

evaluate the validity of the research recounted by the

authors of articles. While not perfect, it is the best system

we know of to keep the scientific process as honest as

possible. The best indication that chemistry is over-

whelmingly done by ethical workers is that there are so

many advances in our discipline every year, and these

advances are based on communicating meaningful re-

sults of chemical research.

8.4 VSEPR—A Better Model 337

the sea. Even the beading of water as it runs down a window would not be possi-

ble if water were a linear molecule. Water is a bent molecule. Can we prove this

with a model—one that will pass the test of properly predicting the shapes of mol-

ecules with which we are unfamiliar? As we continue this discussion, please keep in

mind that models are, by their nature, simplifications that help us predict chemical

behavior. Because they simplify often subtle chemistry, they do not always properly

predict what happens. Yet we use models because the best ones give us insight and

some degree of predictive power. Such is the case with the VSEPR model, which

we describe next.

Description of VSEPR

Ronald J. Gillespie (1924–) and Sir Ronald Nyholm (1917–1971) introduced the

valence shell electron-pair repulsion model (VSEPR; pronounced “VES–per”) in

1957 to facilitate the construction of three-dimensional molecular structures.

This model is based on the repulsion between pairs of valence electrons (which

have similar charges). The key assumption in the

VSEPR model is that bonding

pairs and lone pairs of electrons move away from each other and orient them-

selves in three-dimensional space to give minimum repulsions (lowest energy

configurations.) To assist in visualizing this process, imagine pairs of electrons as

balloons tied together (Figure 8.21). Two balloons tied together orient in such a

way that they are opposite each other. Three balloons tied together orient them-

selves in a triangular shape, and four balloons push themselves to occupy the

corners of a tetrahedron. What happens if you distort the shapes by pushing the

balloons together and then letting go? The balloons push away again to return,

ideally, to the original shape.

VSEPR models determine the shape of a molecule on the basis of the number

of electron groups about the central atom. The resulting model of the molecule

represents the positions of the electron groups in three dimensions (the

electron-

group geometry

). Electron groups include lone pairs and bonding electrons; a

single bond, a double bond, or a triple bond counts as a single electron group.

However, when we determine the experimental shape of a molecule, we actually

find the positions of the different nuclei (the

molecular geometry). The actual

shape of the molecule can be different from the electron-group geometry, but

that doesn’t mean that the molecular geometry is unattainable from the electron-

group geometry. In fact, we can use the VSEPR model’s electron-group geometry

to determine the molecular geometry if we consider the geometry of the atoms to

contain “invisible” lone pairs. The result is the molecular geometry. Let’s consider

some examples of the VSEPR model to illustrate this process. Table 8.7 shows the

shapes of each of the electron-group geometries that we will discuss.

Examples of Three-Dimensional Structures

Using the VSEPR Model

Beryllium chloride (BeCl

2

) is a toxic white solid primarily used to make beryl-

lium metal. The Lewis dot structure of this compound indicates to us that the

beryllium atom is surrounded by two bonding pairs of electrons. By analogy, we

can consider the central atom in BeCl

2

by tying two balloons together. The bal-

loons push apart to occupy opposite orientations, so VSEPR predicts the elec-

tron-group geometry to be linear with a ClOBeOCl bond angle of 180°. The

molecular geometry is also linear because there are no lone-pair electrons around

the central beryllium atom.

This type of geometry is also predicted for carbon dioxide (CO

2

). The Lewis

dot structure of CO

2

indicates that there are only two electron groups in the form

of double bonds that extend from the central carbon atom. Carbon dioxide is a

linear molecule.

Cl Be

180°

Cl

OC

180°

O

Visualization: VSEPR

Video Lesson: Valence Shell

Electron-Pair Repulsion Theory