Jackson M.J. Micro and Nanomanufacturing

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Mechanical Micromachining 241

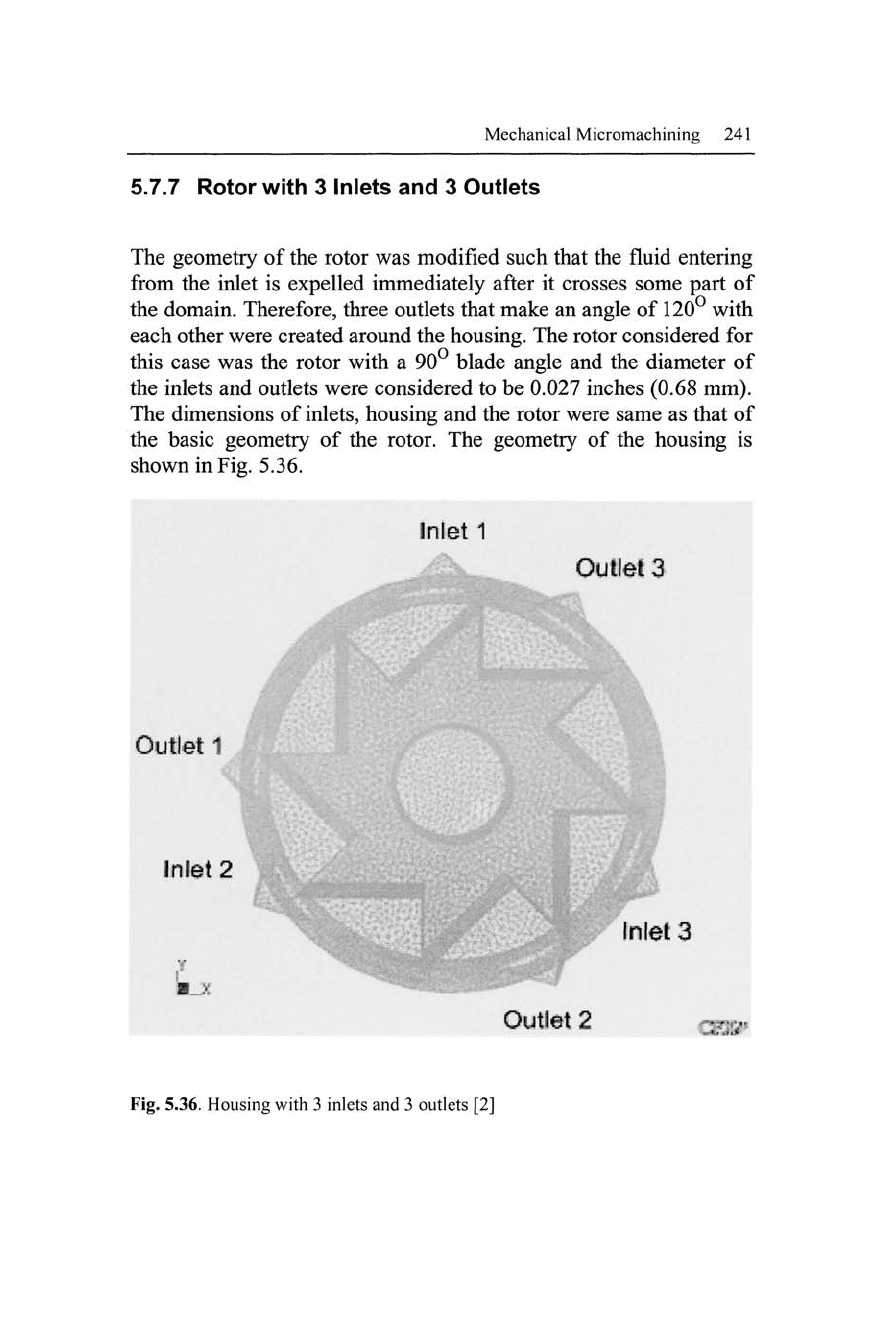

5.7.7 Rotor with 3 Inlets and 3 Outlets

The geometry of the rotor was modified such that the fluid entering

from the inlet is expelled immediately after it crosses some part of

the domain. Therefore, three outlets that make an angle of 120° with

each other were created around the housing. The rotor considered for

this case was the rotor with a 90° blade angle and the diameter of

the inlets and outlets were considered to be 0.027 inches (0.68 mm).

The dimensions of

inlets,

housing and the rotor were same as that of

the basic geometry of the rotor. The geometry of the housing is

shown in Fig. 5.36.

Fig. 5.36. Housing with 3 inlets and 3 outlets [2]

242 Micro- and Nanomanufacturing

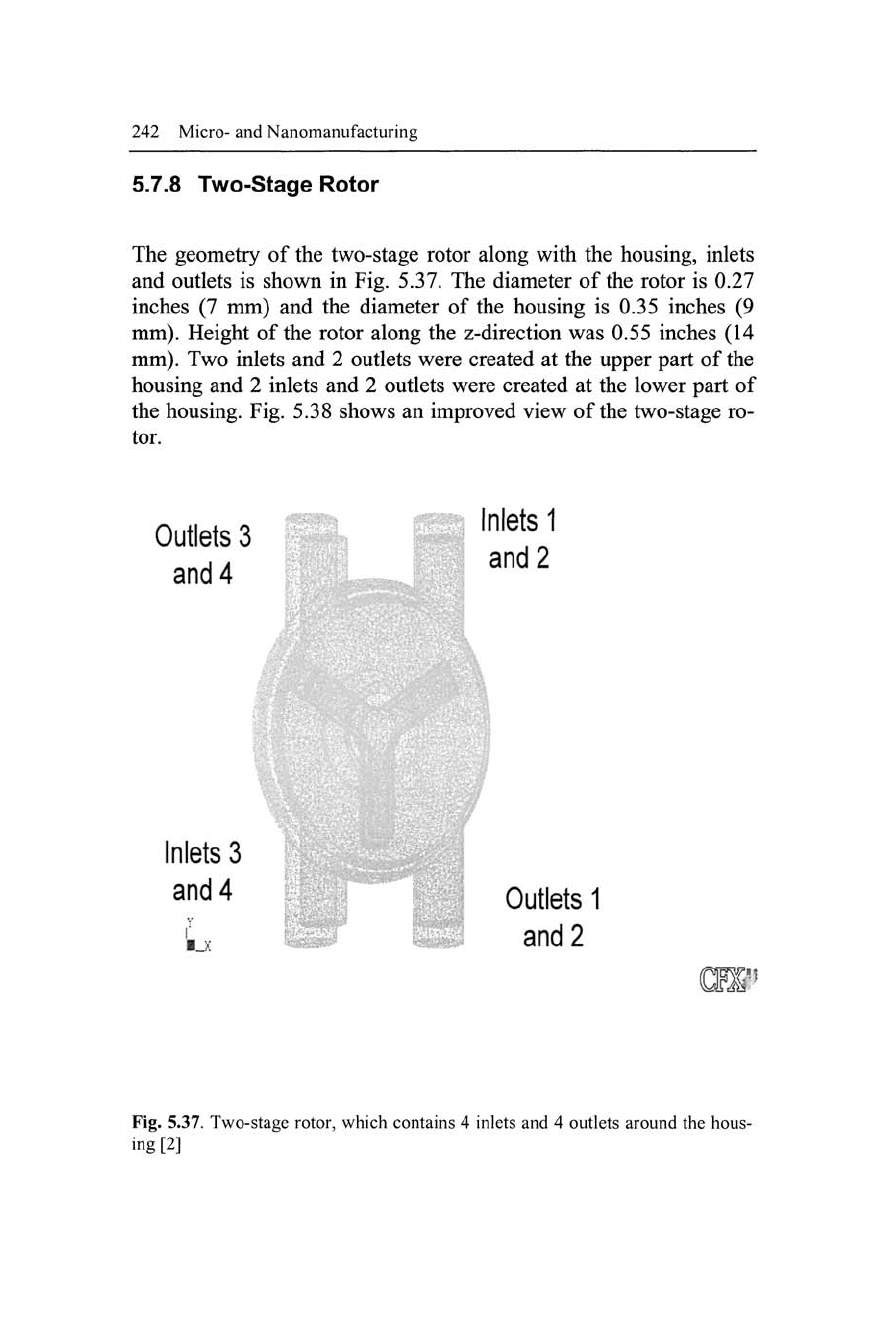

5.7.8 Two-Stage Rotor

The geometry of the two-stage rotor along with the housing, inlets

and outlets is shown in Fig. 5.37. The diameter of the rotor is 0.27

inches (7 mm) and the diameter of the housing is 0.35 inches (9

mm).

Height of the rotor along the z-direction was 0.55 inches (14

mm).

Two inlets and 2 outlets were created at the upper part of the

housing and 2 inlets and 2 outlets were created at the lower part of

the housing. Fig. 5.38 shows an improved view of the two-stage ro-

tor.

Outlets 3

and 4

Inlets 1

and 2

Inlets 3

and 4

L

Outlets 1

and 2

Fig. 5.37. Two-stage rotor, which contains 4 inlets and 4 outlets around the hous-

ing[2]

Mechanical Micromachining 243

\ w v

*

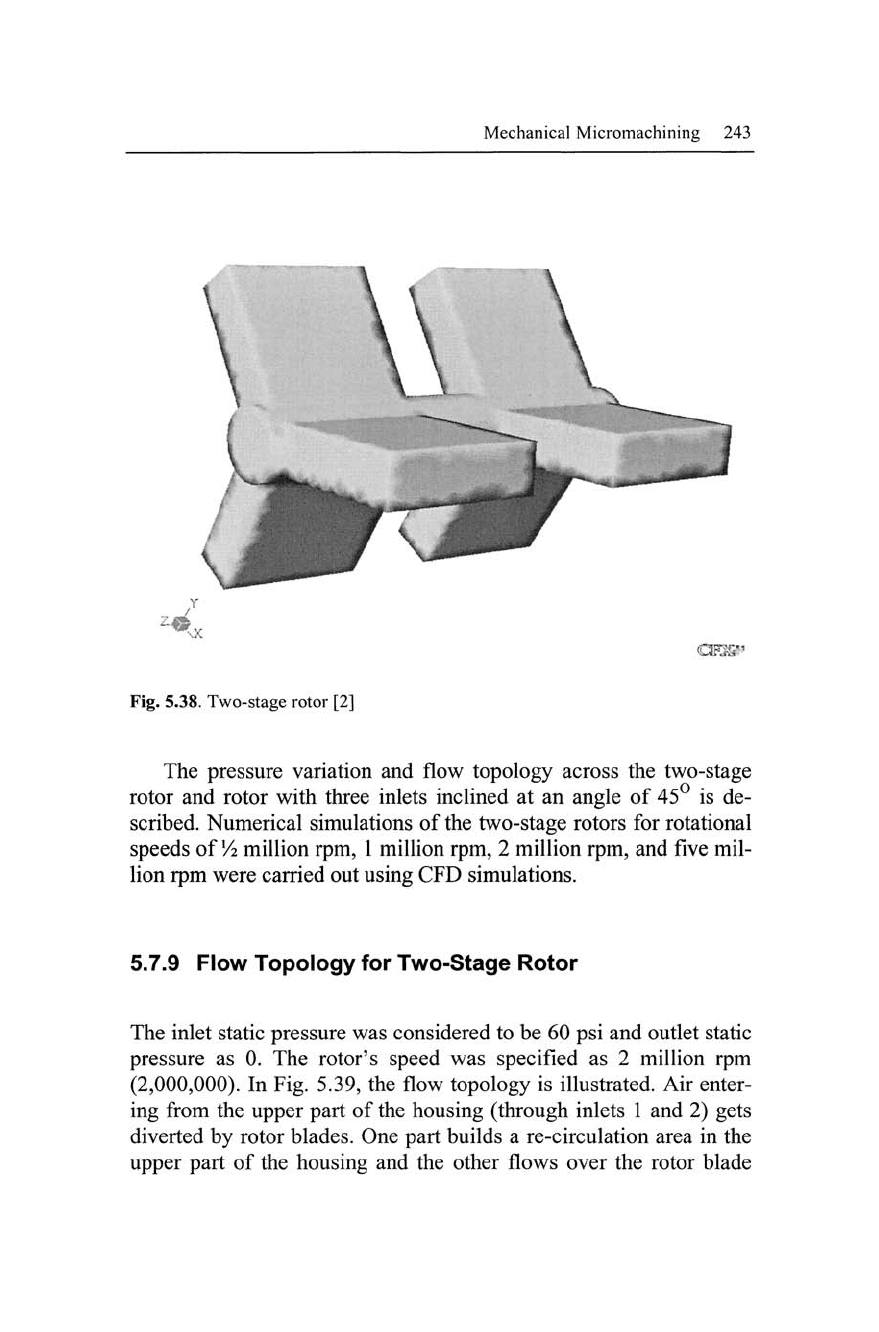

Fig. 5.38. Two-stage rotor [2]

The pressure variation and flow topology across the two-stage

rotor and rotor with three inlets inclined at an angle of 45° is de-

scribed. Numerical simulations of the two-stage rotors for rotational

speeds of

Vi

million rpm, 1 million rpm, 2 million rpm, and five mil-

lion rpm were carried out using CFD simulations.

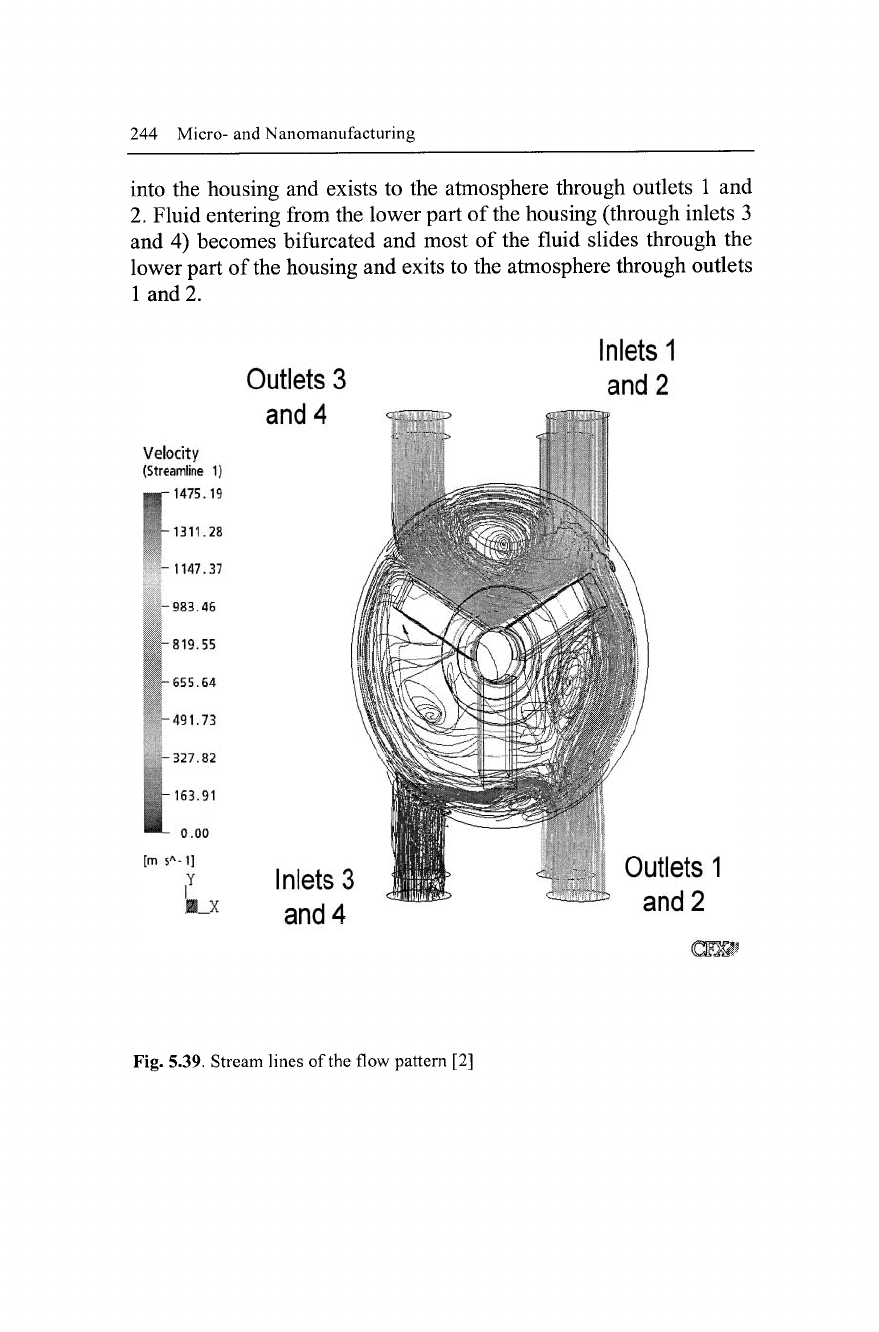

5.7.9 Flow Topology for Two-Stage Rotor

The inlet static pressure was considered to be 60 psi and outlet static

pressure as 0. The rotor's speed was specified as 2 million rpm

(2,000,000). In Fig. 5.39, the flow topology is illustrated. Air enter-

ing from the upper part of the housing (through inlets 1 and 2) gets

diverted by rotor blades. One part builds a re-circulation area in the

upper part of the housing and the other flows over the rotor blade

244 Micro- and Nanomanufacturing

into the housing and exists to the atmosphere through outlets 1 and

2.

Fluid entering from the lower part of the housing (through inlets 3

and 4) becomes bifurcated and most of the fluid slides through the

lower part of

the

housing and exits to the atmosphere through outlets

1 and 2.

Velocity

(Streamline 1)

•p 1475.19

-1311.28

-1147.37

-983.46

-819.55

-655.64

-491.73

-327.82

ill

[m s

A

-1]

i

Y

Outlets

3

and

4

Inlets

1

and

2

.B_X

Inlets

3

and

4

Outlets

1

and

2

Fig. 5.39. Stream lines of the flow pattern [2]

Mechanical Micromachining

245

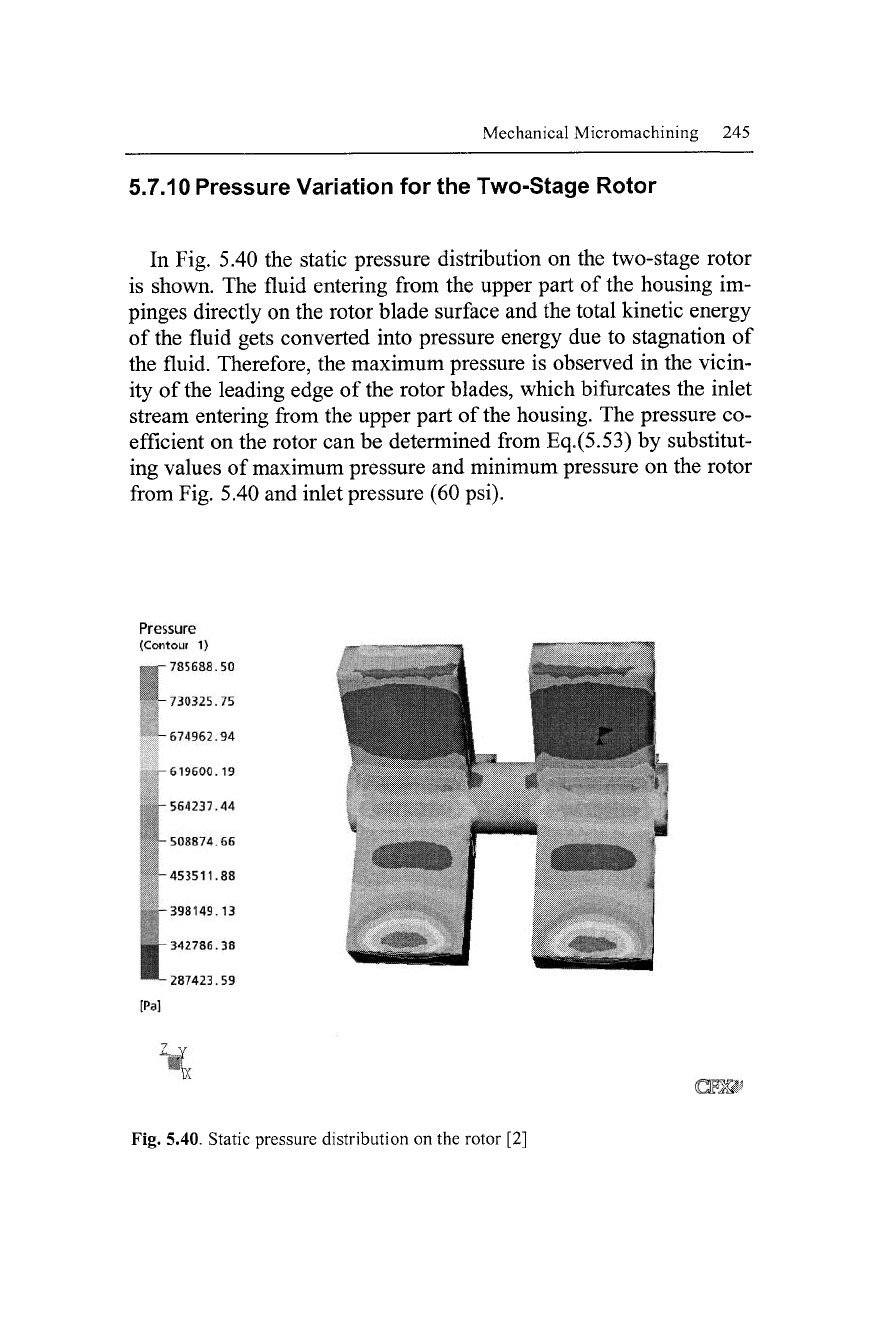

5.7.10 Pressure Variation for the Two-Stage Rotor

In Fig. 5.40 the static pressure distribution

on

the two-stage rotor

is shown. The fluid entering from the upper part

of

the housing im-

pinges directly on the rotor blade surface and the total kinetic energy

of the fluid gets converted into pressure energy due

to

stagnation

of

the fluid. Therefore, the maximum pressure

is

observed

in

the vicin-

ity of the leading edge

of

the rotor blades, which bifurcates the inlet

stream entering from the upper part of the housing. The pressure co-

efficient on the rotor can be determined from Eq.(5.53)

by

substitut-

ing values of maximum pressure and minimum pressure on the rotor

from Fig. 5.40 and inlet pressure (60 psi).

Pressure

(Contour

1)

785688.50

^-730325.75

-674962.94

-619600.19

-564237.44

-508874.66

-453511.88

, -398149.13

1^-342786.38

™-

287423.59

[Pa]

Fig. 5.40. Static pressure distribution on the rotor

[2]

246 Micro- and Nanomanufacturing

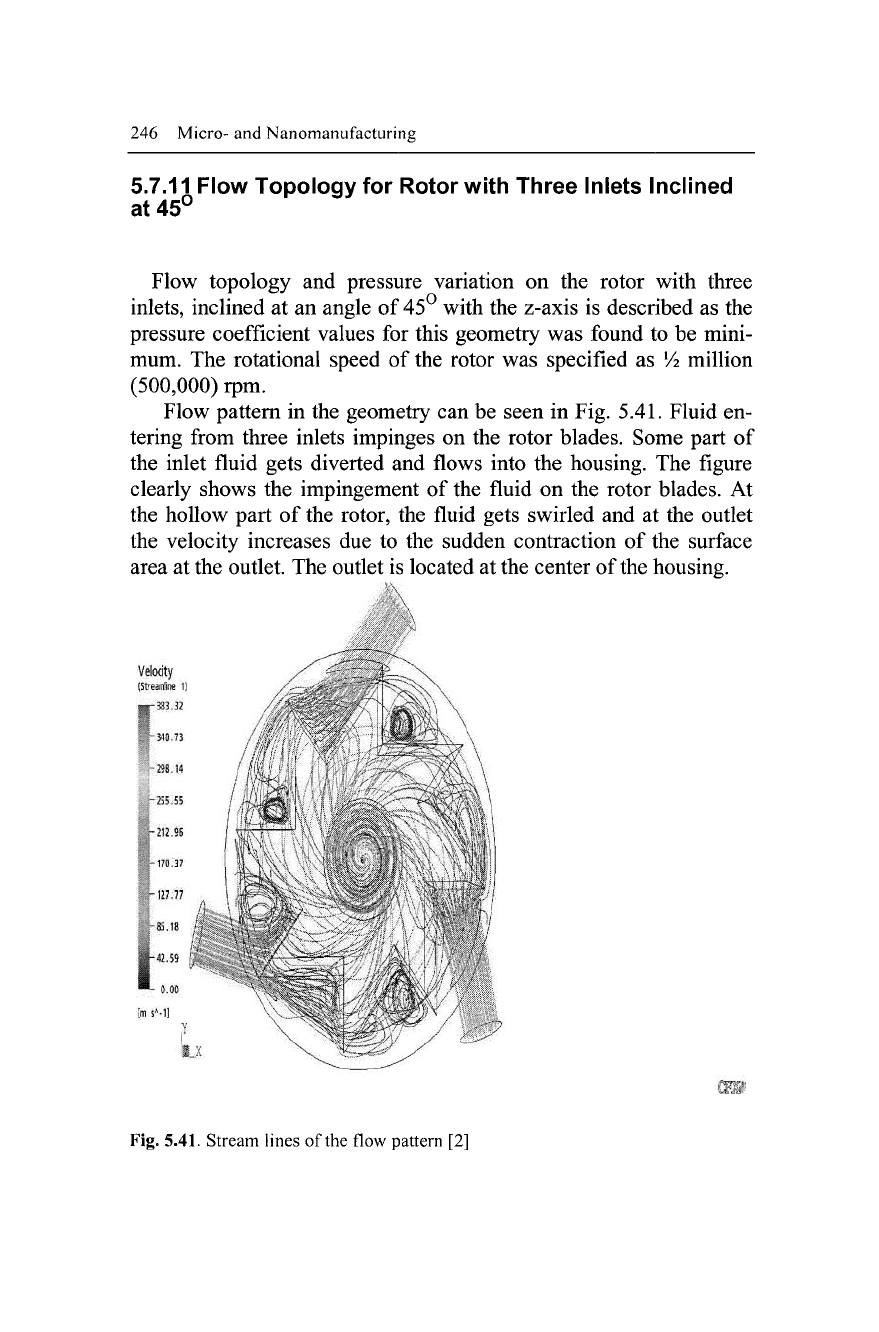

5.7.11 Flow Topology for Rotor with Three Inlets Inclined

at 45°

Flow topology and pressure variation on the rotor with three

inlets,

inclined at an angle of 45° with the z-axis is described as the

pressure coefficient values for this geometry was found to be mini-

mum. The rotational speed of the rotor was specified as Vi million

(500,000) rpm.

Flow pattern in the geometry can be seen in Fig. 5.41. Fluid en-

tering from three inlets impinges on the rotor blades. Some part of

the inlet fluid gets diverted and flows into the housing. The figure

clearly shows the impingement of the fluid on the rotor blades. At

the hollow part of the rotor, the fluid gets swirled and at the outlet

the velocity increases due to the sudden contraction of the surface

area at the outlet. The outlet is located at the center of

the

housing.

Velocity

(Streamline

1)

Fig. 5.41. Stream lines of the flow pattern [2]

Mechanical Micromachining 247

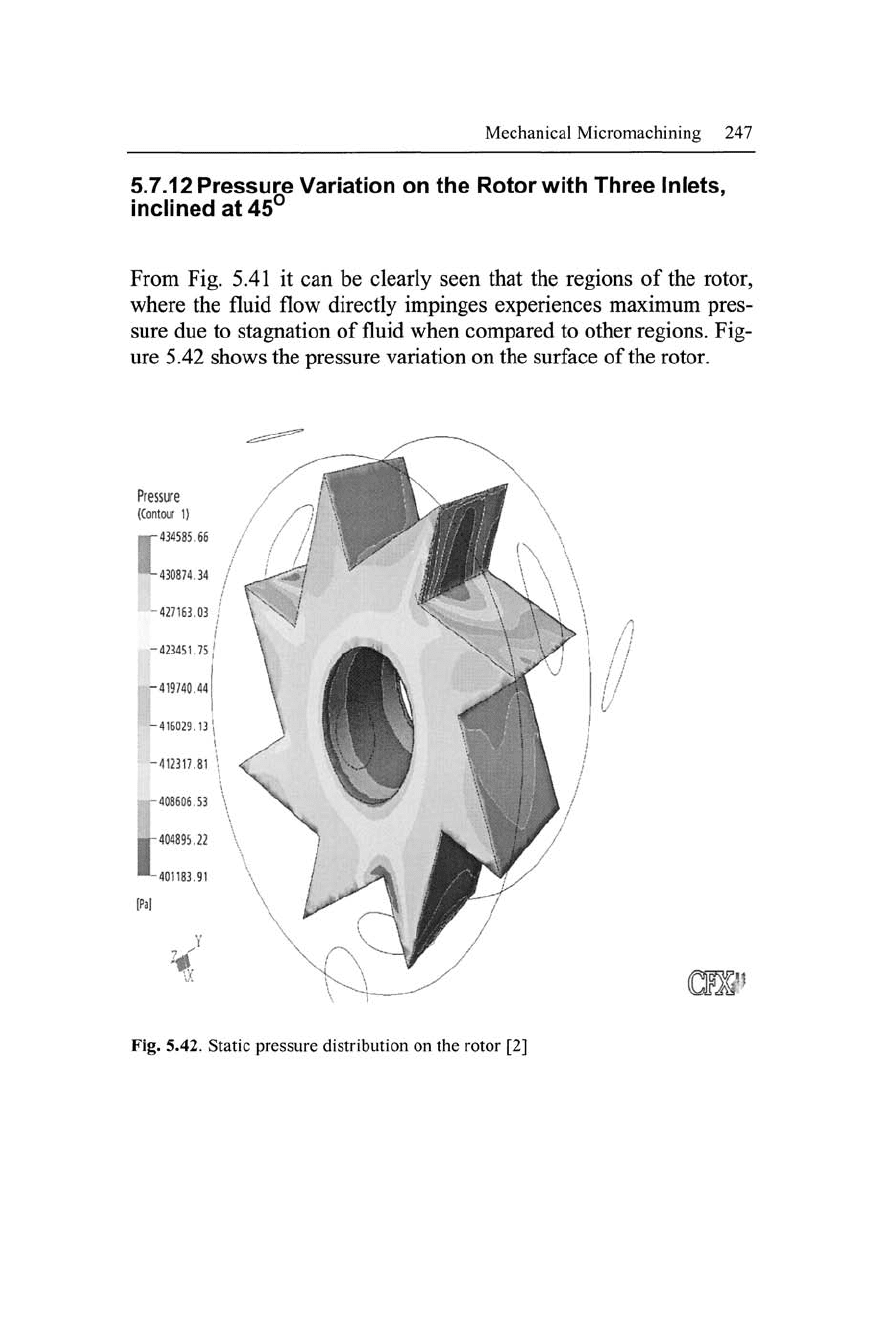

5.7.12 Pressure Variation on the Rotor with Three Inlets,

inclined at 45°

From Fig. 5.41 it can be clearly seen that the regions of the rotor,

where the fluid flow directly impinges experiences maximum pres-

sure due to stagnation of fluid when compared to other

regions.

Fig-

ure 5.42 shows the pressure variation on the surface of the rotor.

Pressure

(Contour

1)

Fig. 5.42. Static pressure distribution on the rotor [2]

248 Micro-

and

Nanomanufacturing

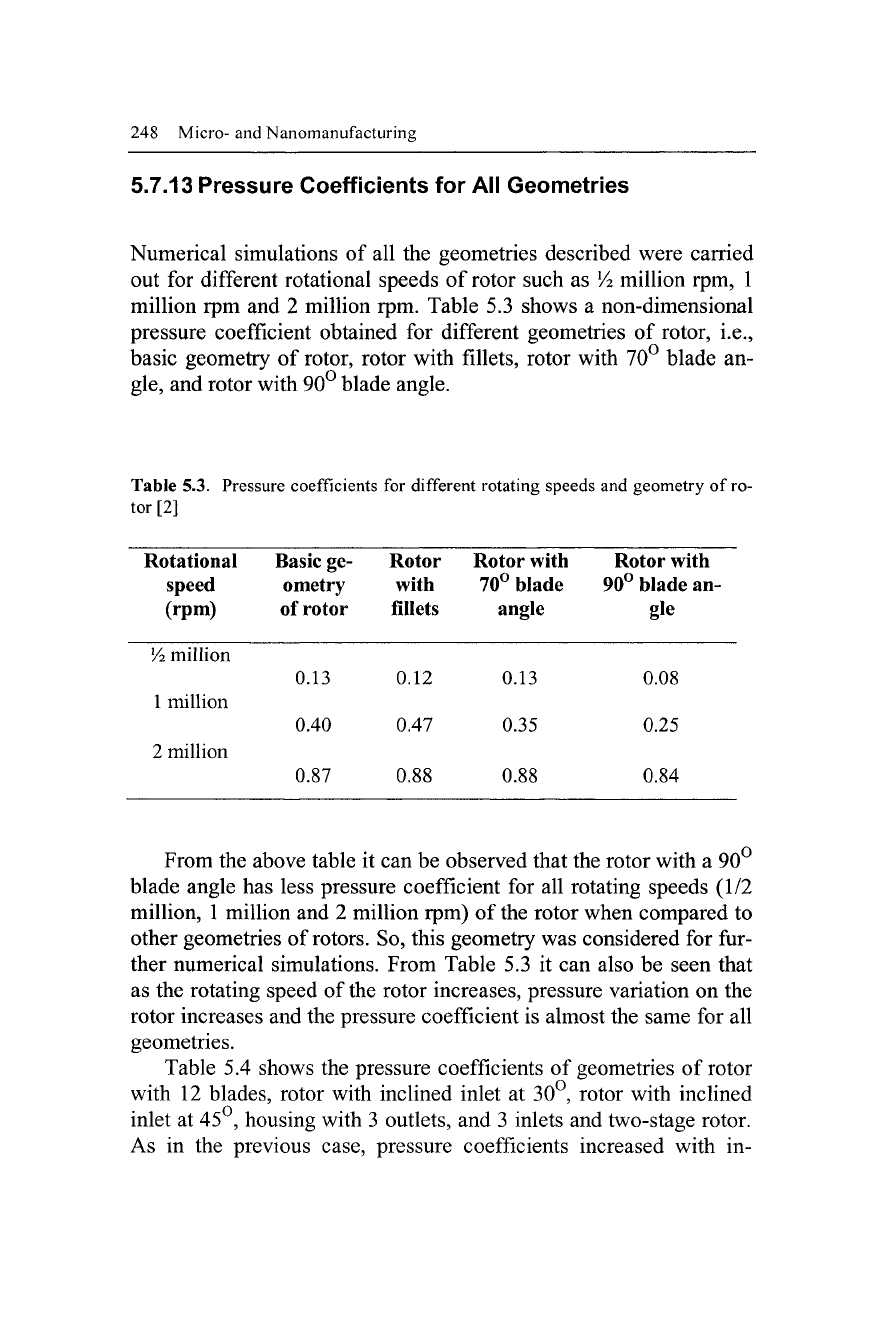

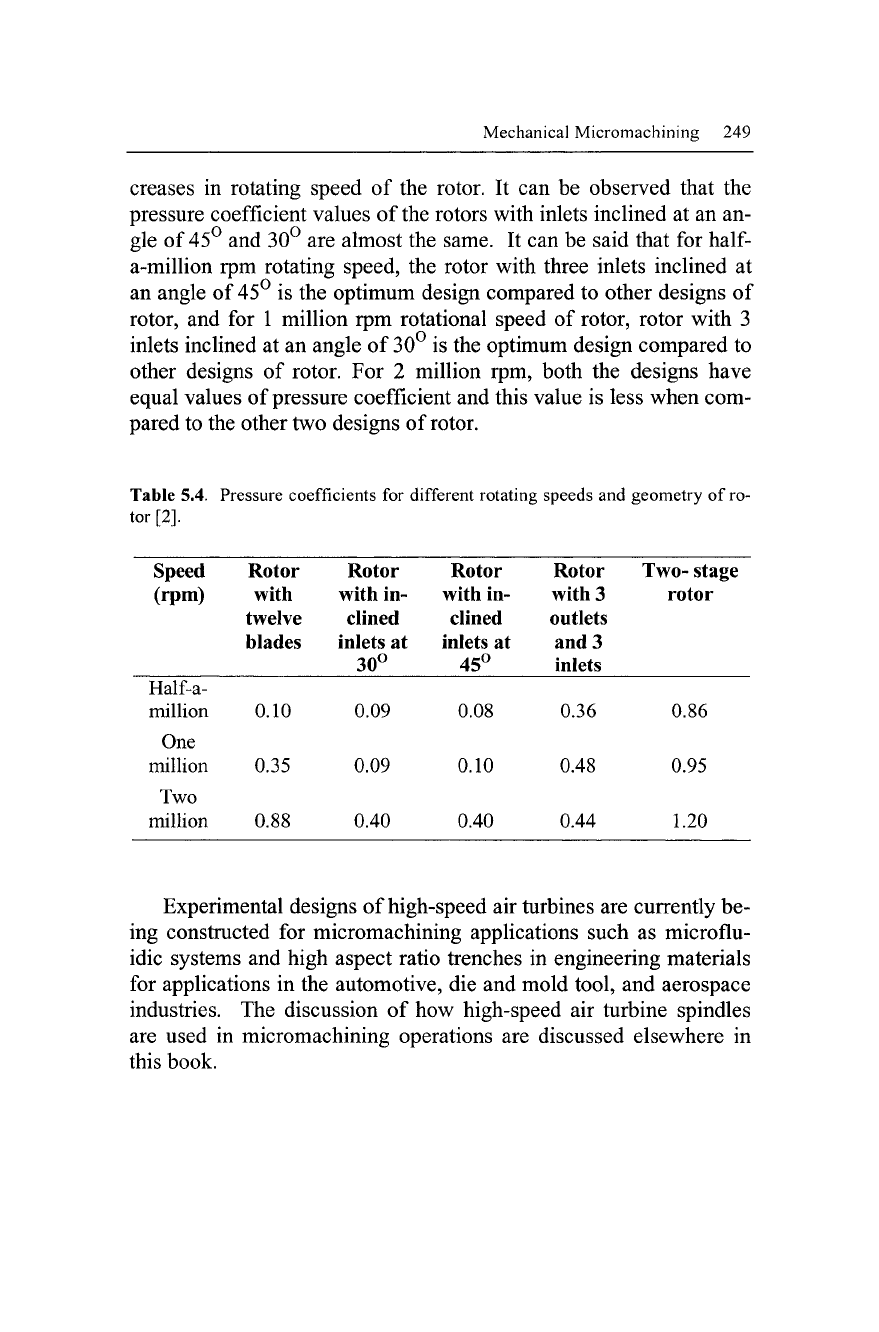

5.7.13 Pressure Coefficients for All Geometries

Numerical simulations of all the geometries described were carried

out for different rotational speeds of rotor such as

Vi

million rpm, 1

million rpm and 2 million rpm. Table 5.3 shows a non-dimensional

pressure coefficient obtained for different geometries of rotor, i.e.,

basic geometry of rotor, rotor with fillets, rotor with 70° blade an-

gle,

and rotor with 90° blade angle.

Table 5.3. Pressure coefficients for different rotating speeds and geometry of

ro-

tor [2]

Rotational Basic ge- Rotor Rotor with Rotor with

speed ometry with 70° blade 90° blade an-

(rpm) of rotor fillets angle gle

Vi

million

0.13 0.12 0.13 0.08

1 million

0.40 0.47 0.35 0.25

2 million

0.87 0.88 0.88 0.84

From the above table it can be observed that the rotor with a 90

blade angle has less pressure coefficient for all rotating speeds (1/2

million, 1 million and 2 million rpm) of the rotor when compared to

other geometries of

rotors.

So, this geometry was considered for fur-

ther numerical simulations. From Table 5.3 it can also be seen that

as the rotating speed of the rotor increases, pressure variation on the

rotor increases and the pressure coefficient is almost the same for all

geometries.

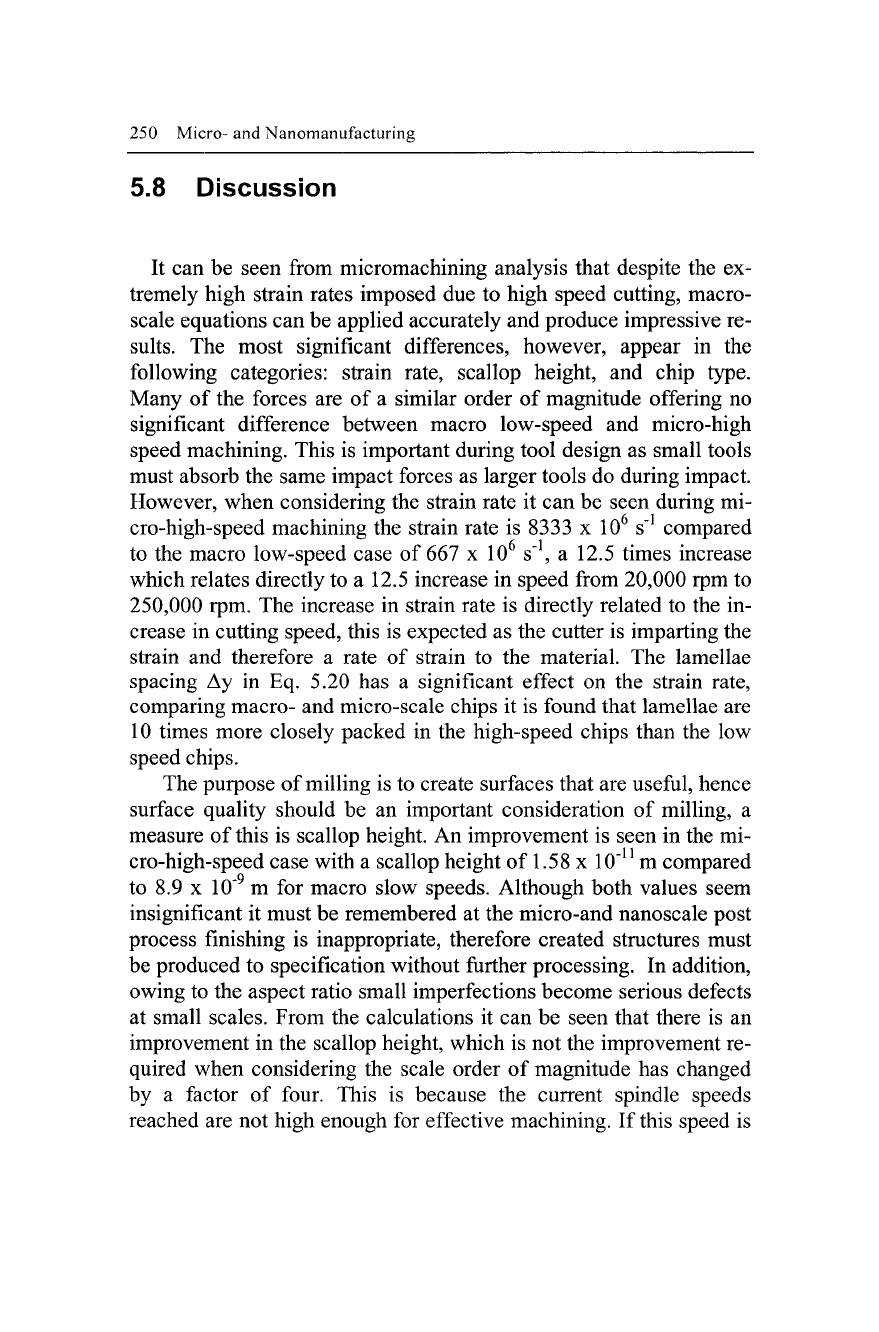

Table 5.4 shows the pressure coefficients of geometries of rotor

with 12 blades, rotor with inclined inlet at 30°, rotor with inclined

inlet at 45°, housing with 3 outlets, and 3 inlets and two-stage rotor.

As in the previous case, pressure coefficients increased with in-

Mechanical Micromachining 249

creases in rotating speed of the rotor. It can be observed that the

pressure coefficient values of the rotors with inlets inclined at an an-

gle of 45° and 30° are almost the same. It can be said that for

half-

a-million rpm rotating speed, the rotor with three inlets inclined at

an angle of 45° is the optimum design compared to other designs of

rotor, and for 1 million rpm rotational speed of rotor, rotor with 3

inlets inclined at an angle of 30° is the optimum design compared to

other designs of rotor. For 2 million rpm, both the designs have

equal values of pressure coefficient and this value is less when com-

pared to the other two designs of rotor.

Table 5.4. Pressure coefficients for different rotating speeds and geometry of ro-

tor [2].

Speed

(rpm)

Half-a-

million

One

million

Two

million

Rotor

with

twelve

blades

0.10

0.35

0.88

Rotor

with in-

clined

inlets at

30°

0.09

0.09

0.40

Rotor

with in-

clined

inlets at

45°

0.08

0.10

0.40

Rotor

with 3

outlets

and 3

inlets

0.36

0.48

0.44

Two-

stage

rotor

0.86

0.95

1.20

Experimental designs of high-speed air turbines are currently be-

ing constructed for micromachining applications such as microflu-

idic systems and high aspect ratio trenches in engineering materials

for applications in the automotive, die and mold tool, and aerospace

industries. The discussion of how high-speed air turbine spindles

are used in micromachining operations are discussed elsewhere in

this book.

250 Micro- and Nanomanufacturing

5.8 Discussion

It can be seen from micromachining analysis that despite the ex-

tremely high strain rates imposed due to high speed cutting, macro-

scale equations can be applied accurately and produce impressive re-

sults.

The most significant differences, however, appear in the

following categories: strain rate, scallop height, and chip type.

Many of the forces are of a similar order of magnitude offering no

significant difference between macro low-speed and micro-high

speed machining. This is important during tool design as small tools

must absorb the same impact forces as larger tools do during impact.

However, when considering the strain rate it can be seen during mi-

cro-high-speed machining the strain rate is 8333 x 10

6

s"

1

compared

to the macro low-speed case of 667 x 10

6

s"

1

, a 12.5 times increase

which relates directly to a 12.5 increase in speed from 20,000 rpm to

250,000 rpm. The increase in strain rate is directly related to the in-

crease in cutting speed, this is expected as the cutter is imparting the

strain and therefore a rate of strain to the material. The lamellae

spacing Ay in Eq. 5.20 has a significant effect on the strain rate,

comparing macro- and micro-scale chips it is found that lamellae are

10 times more closely packed in the high-speed chips than the low

speed chips.

The purpose of milling is to create surfaces that are useful, hence

surface quality should be an important consideration of milling, a

measure of this is scallop height. An improvement is seen in the mi-

cro-high-speed case with a scallop height of 1.58 x

10"

11

m compared

to 8.9 x 10'

9

m for macro slow speeds. Although both values seem

insignificant it must be remembered at the micro-and nanoscale post

process finishing is inappropriate, therefore created structures must

be produced to specification without further processing. In addition,

owing to the aspect ratio small imperfections become serious defects

at small scales. From the calculations it can be seen that there is an

improvement in the scallop height, which is not the improvement re-

quired when considering the scale order of magnitude has changed

by a factor of four. This is because the current spindle speeds

reached are not high enough for effective machining. If this speed is