Higgins R.A. Engineering Metallurgy: Applied Physical Metallurgy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

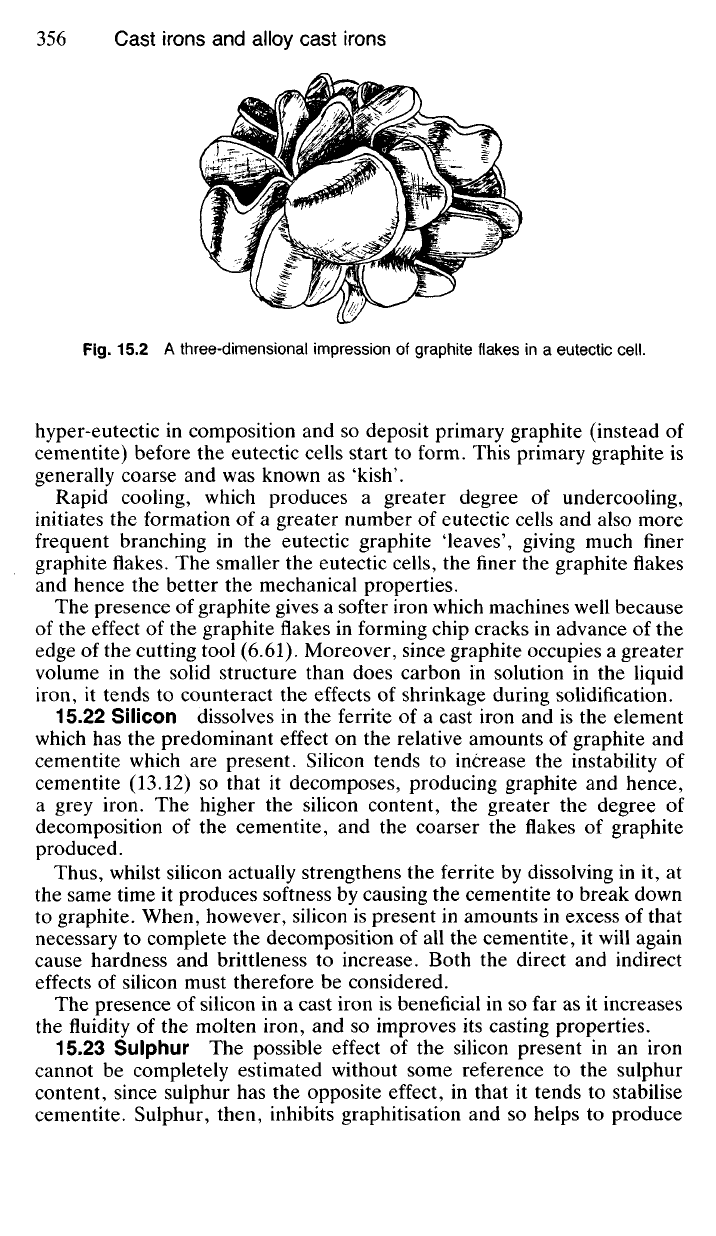

Fig.

15.2 A three-dimensional impression of graphite flakes in a eutectic

cell.

hyper-eutectic in composition and so deposit primary graphite (instead of

cementite) before the eutectic cells start to form. This primary graphite is

generally coarse and was known as 'kish'.

Rapid cooling, which produces a greater degree of undercooling,

initiates the formation of a greater number of eutectic cells and also more

frequent branching in the eutectic graphite 'leaves', giving much finer

graphite flakes. The smaller the eutectic cells, the finer the graphite flakes

and hence the better the mechanical properties.

The presence of graphite gives a softer iron which machines well because

of the effect of the graphite flakes in forming chip cracks in advance of the

edge of the cutting tool (6.61). Moreover, since graphite occupies a greater

volume in the solid structure than does carbon in solution in the liquid

iron, it tends to counteract the effects of shrinkage during solidification.

15.22 Silicon dissolves in the ferrite of a cast iron and is the element

which has the predominant effect on the relative amounts of graphite and

cementite which are present. Silicon tends to increase the instability of

cementite (13.12) so that it decomposes, producing graphite and hence,

a grey iron. The higher the silicon content, the greater the degree of

decomposition of the cementite, and the coarser the flakes of graphite

produced.

Thus,

whilst silicon actually strengthens the ferrite by dissolving in it, at

the same time it produces softness by causing the cementite to break down

to graphite. When, however, silicon is present in amounts in excess of that

necessary to complete the decomposition of all the cementite, it will again

cause hardness and brittleness to increase. Both the direct and indirect

effects of silicon must therefore be considered.

The presence of silicon in a cast iron is beneficial in so far as it increases

the fluidity of the molten iron, and so improves its casting properties.

15.23 Sulphur The possible effect of the silicon present in an iron

cannot be completely estimated without some reference to the sulphur

content, since sulphur has the opposite effect, in that it tends to stabilise

cementite. Sulphur, then, inhibits graphitisation and so helps to produce

a hard, brittle, white iron. Moreover, its presence as the sulphide FeS in

cast iron will also increase the tendency to brittleness.

During the melting of cast iron in the cupola there is a tendency for

some silicon to be oxidised and lost in the slag. At the same time some

sulphur will always be absorbed from the coke in the cupola. Both of these

changes in composition tend to make the iron more 'white' as they are

opposed to the formation of graphite. The foundryman therefore makes

allowances for these changes during melting in the cupola.

15.24 Manganese The effect of sulphur is governed, in turn, by the

amount of manganese present. Manganese combines with sulphur to form

manganese sulphide, MnS, which, unlike iron(II) sulphide, is insoluble in

the molten iron and floats to the top to join the slag. The indirect effect

of manganese, therefore, is to promote graphitisation because of the re-

duction of the sulphur content which it causes. Manganese has a stabilising

effect on carbides, however, so that this offsets the effect of sulphur

reduction in promoting graphitisation. The more direct effects of mangan-

ese include the hardening of the iron, the refinement of grain and an

increase in strength.

15.25 Phosphorus is present in cast iron as the phosphide Fe

3

P, which

forms a eutectic with the ferrite in grey irons, and with ferrite and cementite

in white irons. These eutectics melt at about 950

0

C, so that high-

phosphorus irons have great fluidity. Cast irons containing 1% phosphorus

are,

therefore, very suitable for the production of castings of thin section.

High phosphorus contents should be avoided in heavy sections however,

since Fe

3

P is brittle and lowers strength considerably. Its presence tends

to promote increased shrinkage.

Phosphorus has a negligible effect on the stability of cementite, but its

direct effect is to promote hardness and brittleness due to the large volume

of phosphide eutectic which a comparatively small amount of phosphorus

will produce. Phosphorus must therefore be kept low in castings where

shock-resistance is important.

The Effect of Rate of Cooling on the Structure

of Cast Iron

15.30 A high rate of cooling during solidification tends to favour the

formation of cementite rather than graphite. That is, the higher the rate

of cooling for any given cast-iron composition the 'whiter' and more brittle

the casting is likely to be. This effect is important in connection with the

choice of a suitable iron for the production of castings of thin section.

Supposing an iron which, when cooled slowly, had a fine grey structure

containing small eutectic cells were chosen for such a purpose. In thin

sections it would cool so rapidly that cementite would form in preference

to graphite and a thin section of completely white iron would result. Such

a section would be brittle and useless.

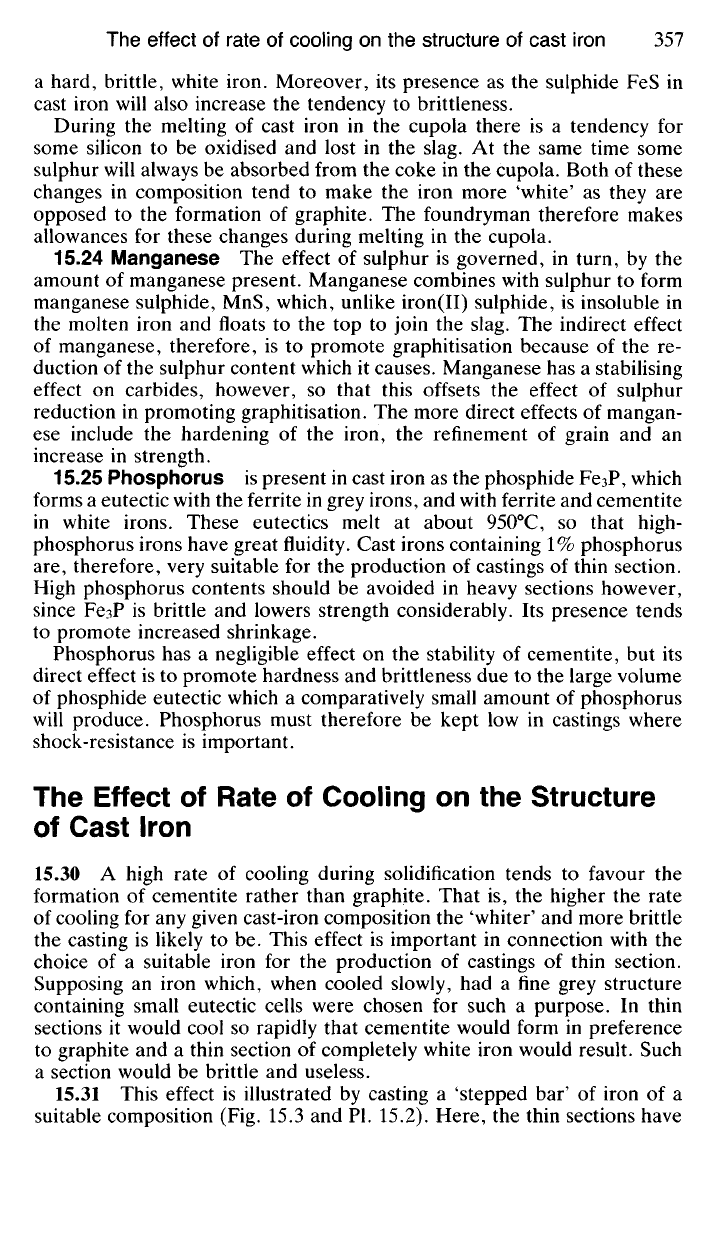

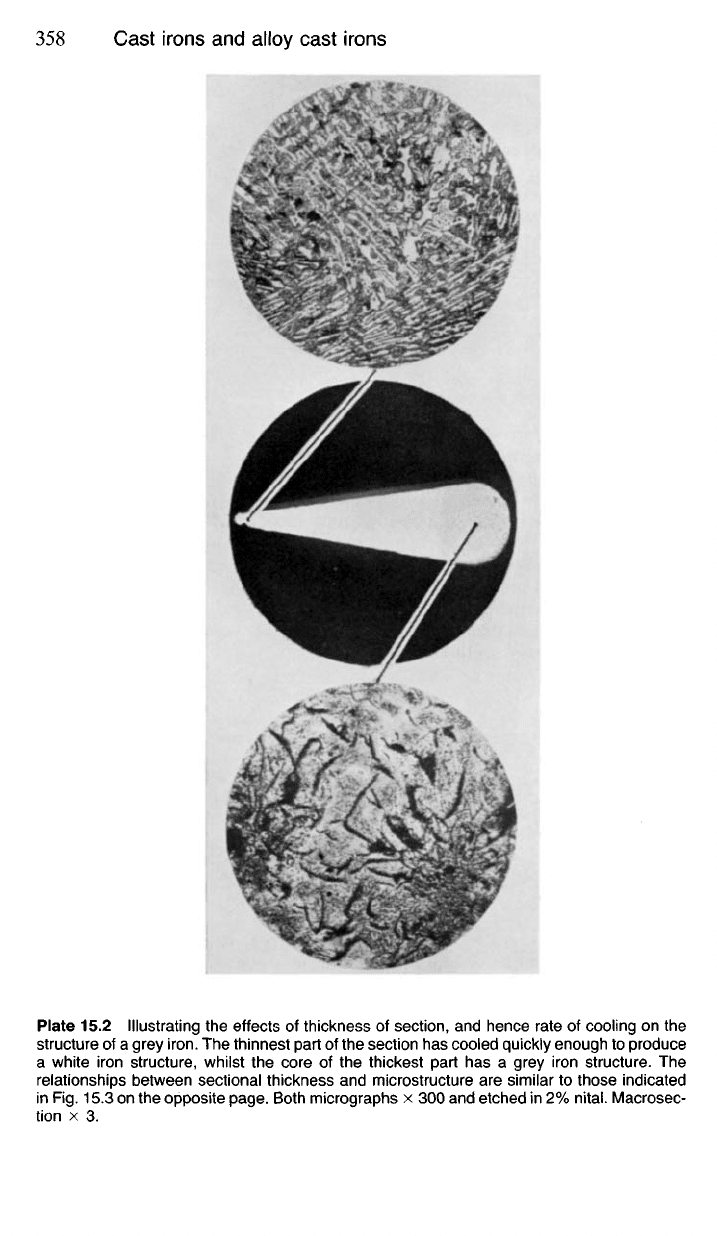

15.31 This effect is illustrated by casting a 'stepped bar' of iron of a

suitable composition (Fig. 15.3 and Pl. 15.2). Here, the thin sections have

Plate 15.2 Illustrating the effects of thickness of section, and hence rate of cooling on the

structure of a grey

iron.

The thinnest part of the section has cooled quickly enough to produce

a white iron structure, whilst the core of the thickest part has a grey iron structure. The

relationships between sectional thickness and microstructure are similar to those indicated

in Rg. 15.3 on the opposite page. Both micrographs x 300 and etched in 2%

nital.

Macrosec-

tion x 3.

Fig.

15.3 The effect of thickness of cross-section on the rate of cooling, and hence upon

the microstructure of a grey cast

iron.

cooled so quickly that solidification of cementite has occurred, as indicated

by the white fracture and high Brinell values. The thicker sections, having

cooled more slowly, are graphitic and consequently softer. Due to the

chilling effect exerted by the mould, most castings have a hard white skin

on the surface. This is often noticeable when taking the first cut in a

machining operation.

In casting thin sections, then, it is necessary to choose an iron of rather

coarser grey fracture than is required in the finished casting. That is, the

iron must have a higher silicon content than that used for the production

of castings of heavy section.

BRINELL

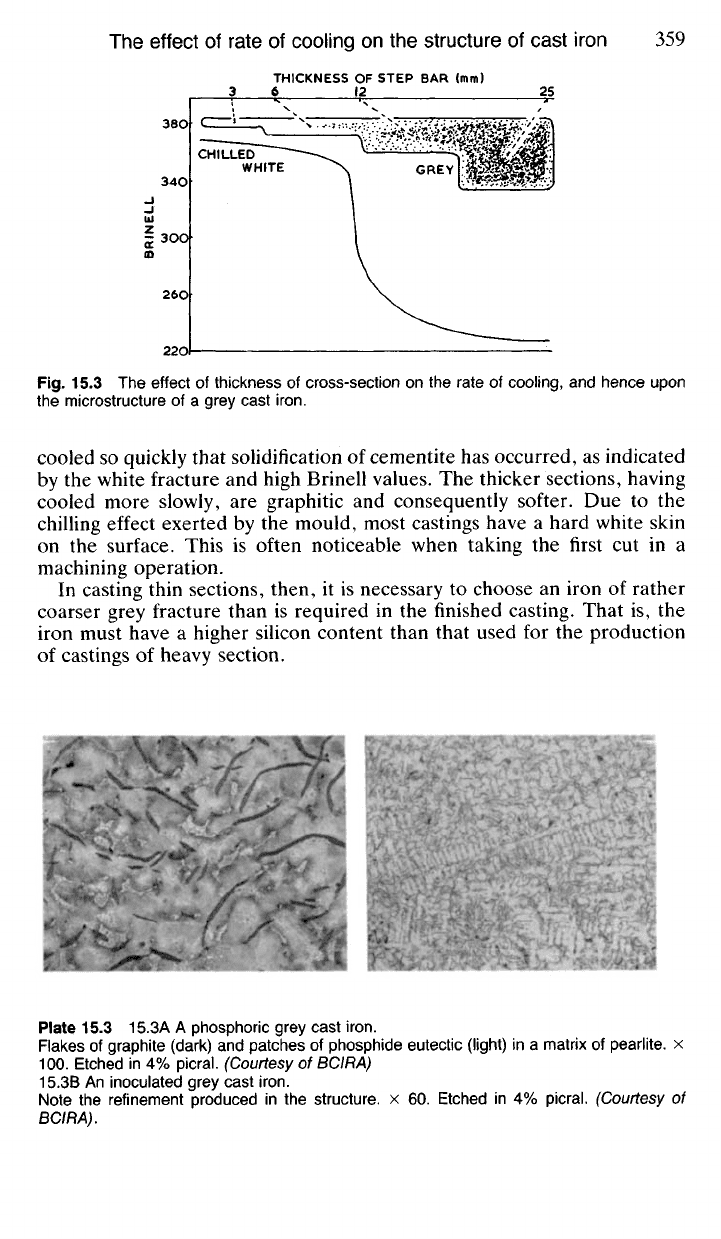

Plate 15.3 15.3A A phosphoric grey cast

iron.

Flakes of graphite (dark) and patches of phosphide eutectic (light) in a matrix of pearlite. x

100.

Etched in 4% picral. (Courtesy of BCIRA)

15.3B An inoculated grey cast

iron.

Note the refinement produced in the structure, x 60. Etched in 4% picral. (Courtesy of

BCIRA).

THICKNESS OF STEP BAR (mm)

GREY

CHILLED

WHITE

The Microstructure of Cast Iron

15.40 Neglecting any patches of phosphide eutectic already mentioned,

the following structures are possible for cast irons of different compositions

and treatments:

(a) Primary Cementite and Pearlite. This structure is typical of the

hard, white, low-silicon (and possibly high-sulphur) irons and is found

also in other types of iron which have been chilled. A cementite-

austenite eutectic forms at 1131°C and as the alloy cools to 723°C the

austenite transforms to pearlite.

(b) Primary Cementite, Graphite and Pearlite. These are 'mottled'

irons of such compositions that localised small changes in either compo-

sition or cooling rate will favour the formation of either cementite or

graphite. The remaining austenite present at 723°C transforms to

pearlite.

(c) Graphite and

Pearlite.

This structure is typical of a high-duty grey

iron which has solidified as a graphite-austenite eutectic and in which

the austenite has then transformed to pearlite at 723°C.

(d) Graphite, Pearlite and

Ferrite.

This will generally be a coarser grey

iron which will be weaker and softer. The silicon content will be high.

Here the graphite-austenite eutectic has cooled slowly enough through

the eutectoid temperature (723°C) for some of the carbon which was

dissolved in the austenite to deposit on to the existing graphite flakes

leaving a matrix of ferrite. Some of the austenite has also transformed

to pearlite.

(e) Graphite and Ferrite. This variety of iron usually has a very high

silicon content. The graphite-austenite eutectic has cooled slowly enough

for the whole of the carbon dissolved in the austenite to diffuse on to

existing graphite flakes leaving a matrix entirely of ferrite. Such a cast

iron is very soft and easily machined. The ferrite present will contain

dissolved silicon and manganese.

In addition to the phases enumerated above, iron phosphide, Fe

3

P, as

previously mentioned, may be present in the microstructure. In white or

mottled iron it will be present as a ternary eutectic with cementite and

ferrite, whilst in coarse grey irons of the type (e) above, a binary eutectic

with ferrite will be formed. This binary eutectic contains only 10% phos-

phorus, so that an overall 1% phosphorus in the iron may produce suf-

ficient phosphide eutectic to account for 10% by volume of the resulting

structure. The embrittling effect of the phosphide eutectic network will

then be evident.

'Growth'

in Cast Irons

15.50 If an engineering cast iron is heated for prolonged periods above

700

0

C the pearlitic cementite tends to break down to give a mixture of

ferrite and graphite. This leads to an increase in volume of the iron. Inevi-

tably some warping will follow and surface cracks will form. As hot gases

penetrate these cracks internal oxidation will occur and lead to the pro-

gressive deterioration of the casting. Cast iron moulds used for the casting

of non-ferrous ingots develop surface cracks in this way, giving a 'crazy

paving' like surface. Trouble will then arise due to dressing oil collecting

in these cracks. Fire bars in ordinary domestic grates often break up due

to the combined action of 'growth' and internal oxidation.

Certain alloy cast irons have been developed to resist 'growth' at high

temperatures. Silal is relatively cheap and contains about 5% silicon with

low carbon. This very high silicon content will favour the formation of

graphite rather than cementite during solidification so that its structure

consists entirely of ferrite and graphite, and no cementite is present which

can cause growth. Unfortunately Silal is rather brittle, so that, where the

higher cost is justified, the alloy Nicrosilal can be used with advantage.

This is an austenitic nickel-chromium cast iron (see Table 15.5).

Varieties

and

Uses

of

Ordinary Cast Iron

15.60 Foundry irons can be classified in the following groups according

to their properties and uses:

15.61 Fluid Irons which can be used where mechanical strength is of

secondary importance, and in which high fluidity is obtained by means of

high silicon (2.5-3.5%) and high phosphorus (up to 1.5%) contents. Both

silicon and phosphorus improve fluidity, and a high silicon content will

further ensure that thin sections will have a reasonably tough grey struc-

ture,

since silicon prevents deep chilling. Such irons were used extensively

at one time for the manufacture of lamp-posts, fireplaces and railings, but

they have now been replaced by ceramic materials for uses such as these.

15.62 Engineering Irons must have mechanical strength and the best

type of microstructure is one with a small eutectic cell size (small graphite

flakes in a pearlite matrix). An iron of this type will possess the best

all-round mechanical properties and also good machinability. The silicon

content will depend on the thickness of section to be cast, but in general

it will not exceed 2.5% for castings of thin section, and may be as low as

1.2% for castings of heavy section.

The phosphorus content must be kept low where a shock-resistant cast-

ing is necessary, though up to 0.8% phosphorus may be present in some

cases in the interests of fluidity. Sulphur must also be kept low (below

0.1%), as it leads to segregation, hard spots and general brittleness.

Irons of this type can have hard, wear-resistant, chilled surfaces intro-

duced at various parts of the casting if desired. This is done by inserting

chilling fillets at appropriate points in the sand mould. These fillets cause

rapid cooling, and hence a layer of white iron on the surface of the casting

at these points. At the same time the core of the casting remains grey and

tough.

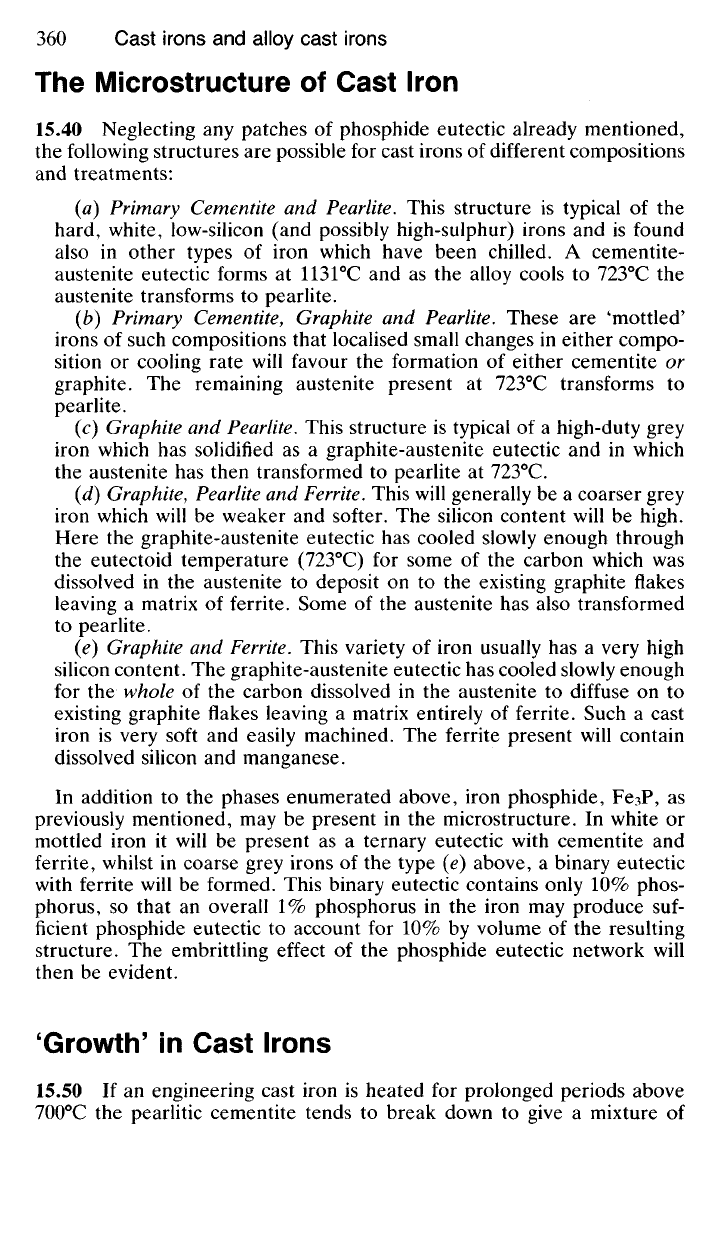

Table 15.1 Compositions and Uses of Some Typical Cast Irons

Composition (%)

C Si Mn S P Uses

3.50 1.15 0.8 0.07 0.10 Ingot moulds and heat-resisting castings

3.30 1.90 0.65 0.08 0.15 Motor brake drums

3.25 2.25 0.65 0.10 0.15 Motor cylinders and pistons

3.25 2.25 0.50 0.10 0.35 Light machine castings

3.25 1.75 0.50 0.10 0.35 Medium machine castings

3.25 1.25 0.50 0.10 0.35 Heavy machine castings

3.60 1.75 0.50 0.10 0.80 Light and medium water pipes

3.40 1.40 0.50 0.10 0.80 Heavy water pipes

3.50 2.75 0.50 0.10 0.90 Ornamental castings requiring low strength—

now obsolete.

15.63 Heavy Castings do not require a high silicon content, as there is

little danger of chilling. Usually, silicon is no higher than 1.5%, with up

to 0.5% phosphorus for such castings as columns and large machine frames.

In castings, such as ingot moulds, which are exposed to high temperatures

a close-grained, non-phosphoric iron should be used.

High-strength Cast Irons

15.70 Over the years a number of modifications of grey cast iron were

made available to give enhanced properties. Thus 'semi steel' was made

by melting a high proportion of steel scrap along with pig iron in the

cupola, whilst Lanz Perlit iron was a fine-grained product made by casting

a low-silicon iron into heated moulds in order to retard the cooling rate.

Various 'trademarked' fine-grained irons were produced by 'inoculating'

a suitable molten iron with materials such as calcium silicide. Modern

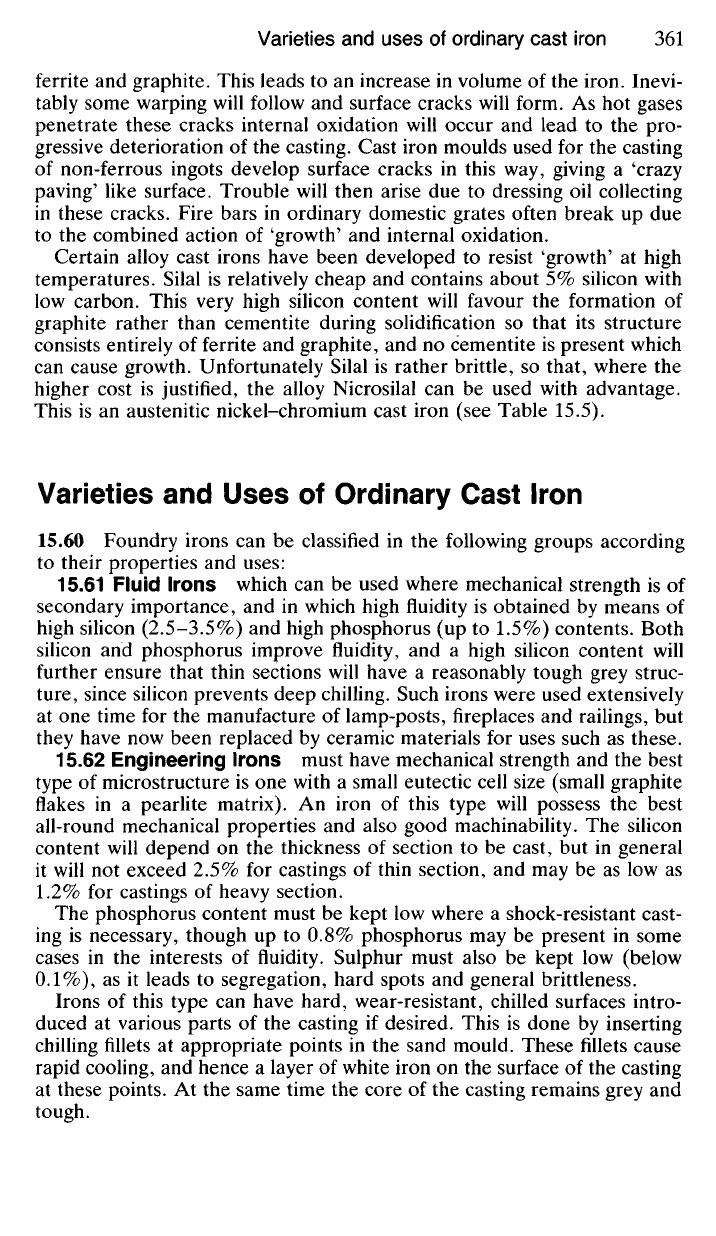

Table 15.2 Typical Mechanical Properties of Engineering Grey Irons (to B.S. 1452)*.

BS 1452: 0.1% proof Tensile strength Total strain at Compressive Fatigue limit

Grade stress (N/mm

2

) (N/mm

2

) failure (%) strength (N/mm

2

) (N/mm

2

)

150 98 150 0.68 600 68

180 117 180 0.60 672 81

220 143 220 0.52 768 99

260 169 260 0.57 864 117

300 195 300 0.50 960 135

350 228 350 0.50 1080 149

400 260 400 0.50 1200 152

*The values are for guidance only—chemical compositions cannot be suggested since these will depend

largely on sectional thickness of castings.

high-strength irons rely almost entirely on treatments which replace the

flake-graphite of ordinary grey iron with graphite in the form of either

spherical particles or 'compacted' flakes.

15.71 Spheroidal-graphite (SG) Cast Iron (also known as Nodular

Iron or Ductile Iron). The production of ordinary cast iron has fallen

considerably in recent years due largely to such influences as the develop-

ment of welding fabrication methods and the use of other materials like

concrete and plastics. Nevertheless the introduction of SG iron in 1946 was

without doubt the most important event during this century in the iron

trade since in SG iron the engineer finds a worthy competitor to cast steel

but often at much lower cost.

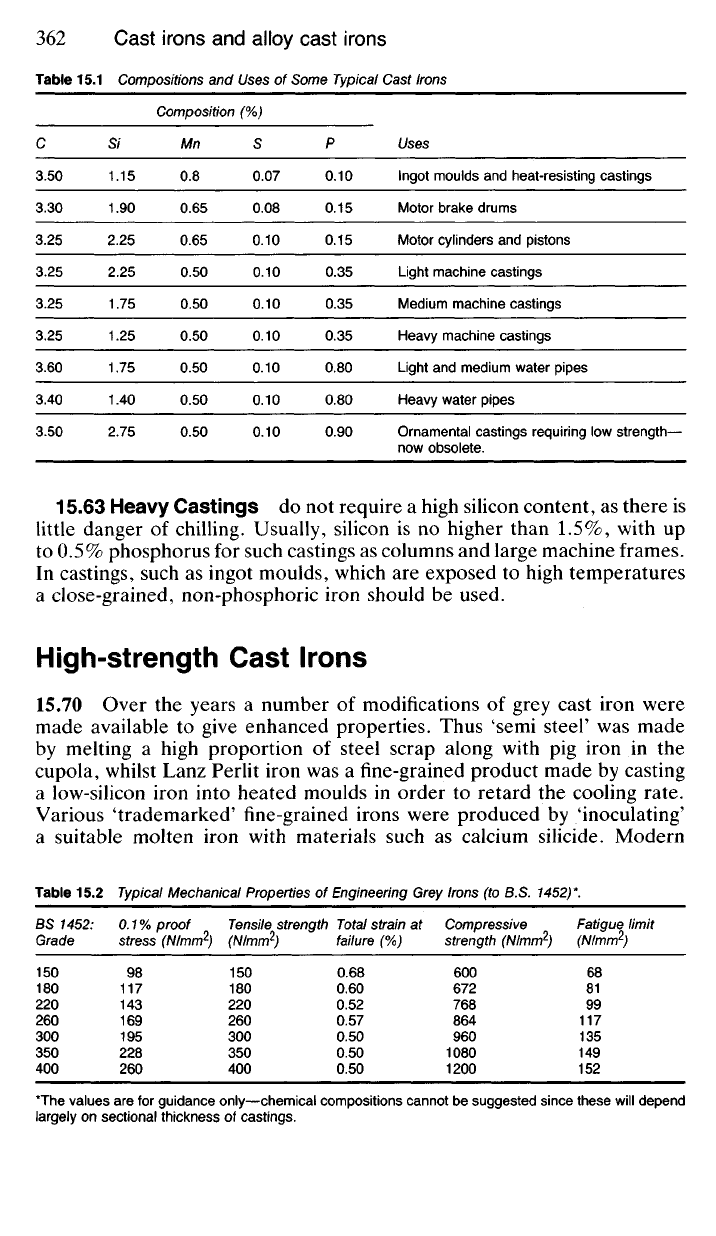

In an ordinary grey cast iron graphite is present as 'flakes' which tend

to have sharp-edged rims. Since these flakes have negligible strength they

act as wide-faced discontinuities in the structure whilst the sharp-edged

rims introduce regions of stress-concentration. In SG cast iron the graphite

flakes are replaced by spherical particles of graphite (Plate 15.4A), SO that

the metallic matrix is much less broken up, and the sharp stress raisers are

eliminated.

The formation of this spheroidal graphite is effected by adding small

amounts of cerium or magnesium to the molten iron just before casting.

Since both of these elements have strong carbide-forming tendencies, the

silicon content of the iron must be high enough (at least 2.5%) in order to

prevent the formation, by chilling, of white iron in thin sections. Mag-

nesium is the more widely used, and is usually added (as a nickel-magnes-

ium alloy) in amounts sufficient to give a residual magnesium content of

0.1%

in the iron. SG cast irons produced by the magnesium process have

tensile strengths of up to 900 N/mm

2

or even higher in some heat-treated

irons.

The term

4

SG iron' really describes a family of cast irons, which

include some alloy irons, but in all cases treatment by inoculants is

Plate

15.4 15.4A A spheroidal-graphite cast

iron.

Here

the graphite has been made to precipitate in nodular form by adding a nickel -

magnesium

alloy, x 100. Etched in 4%

picral.

(Courtesy of BCIRA)

15.4B

A compacted graphite cast

iron.

Unetched

to show the rounded edges of the graphite

flakes,

x 100. (Courtesy of

BCIRA).

*No 'typical compositions' are included since composition, related to the structure in the last column,

will vary with sectional thickness. It will be noted that the 'Grade' designation indicates both tensile

strength and % elongation.

employed to produce spheroidal-graphite particles. Some patents claim the

production of SG iron using the following substances instead of cerium or

magnesium: calcium, calcium carbide, calcium fluoride, lithium, strontium,

barium and argon. In all cases high-quality raw material, as free as possible

from carbide-stabilising elements is required. BS 2789 grades SG irons

according to their mechanical properties and some of these are shown in

Table 15.3.

Those irons consisting of graphite nodules in a ferrite matrix will have

high ductility and toughness whilst those consisting of graphite nodules in

a pearlite matrix will be characterised by high strength. Some of these

irons are heat-treated to give even better mechanical properties. Thus,

sections of the American motor industry harden some of their SG iron

gears by the use of 'interrupted austempering'. This involves austenitising

the gears at 900

0

C for 3.5 h in a nitrogen atmosphere followed by quenching

to 235°C and holding at that temperature for 2 h. Since transformation

from austenite occurs isothermally at 235°C there is little distortion in

shape. It is claimed that SG iron hypoid ring and pinion gears are compar-

able with those of steel in terms of fatigue and also have a greater torsional

strength.

Tensile strengths of the order of 1600 N/mm

2

(with an elongation of. 1%)

can be obtained by austempering SG iron at 250

0

C, following an initial

austenitising at 900

0

C; whilst higher austempering temperatures up to

450

0

C will yield bainitic structures of lower strengths (900-1200 N/mm

2

)

but elongations up to 14%. SG iron crankshafts cast to near final shape

are less expensive and some 10% lighter than equivalent forged com-

ponents. They are heat-treated in a similar way to the gears mentioned

above.

15.72 Malleable Cast Irons are irons which have been cast to shape in

the ordinary way, but in which ductility and malleability have been increased

from almost zero to a considerable amount by subsequent heat-treatment.

The names of the two original malleabilising processes, the Blackheart and

the Whiteheart, refer to the colour of a fractured section after heat-

treatment has been completed. A more recent process for the manufacture

of pearlitic malleable iron aims at the production of castings which, when

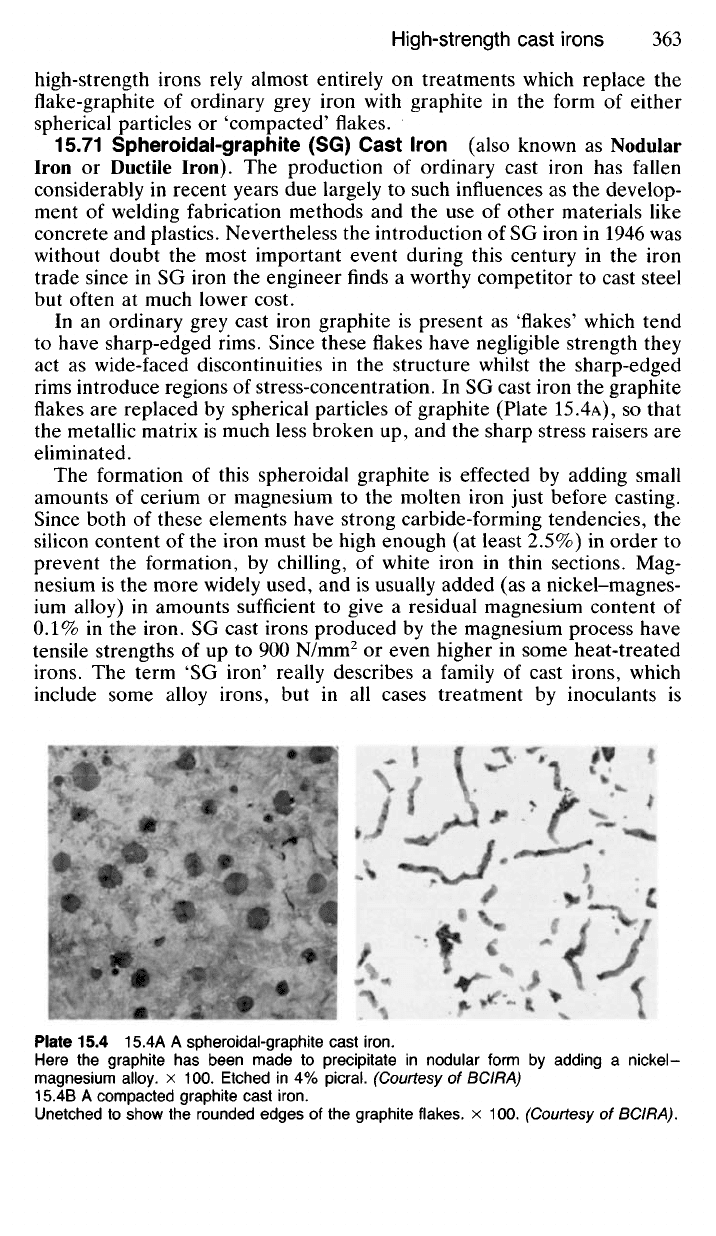

Table 15.3 Grades of Spheroidal-graphite Iron to BS 2789*

Grade

370/17

420/12

500/7

600/3

700/2

800/2

0.2% proof

stress (N/mm

2

)

230

250

310

350

400

460

Tensile strength

(N/mm

2

)

370

420

500

600

700

800

Elongation

(%)

17

12

7

3

2

2

Typical hardness

(Hb)

175

200

205

230

265

300

Structure—spheroidal

graphite in a matrix of:

Ferrite

Ferrite

Ferrite-pearlite

Ferrite-pearlite

Pearlite

Pearlite, or a heat-treated

structure.

suitably treated, will have tensile strengths of up to 775 N/mm

2

. In all three

processes the original casting is of white iron, which will be very brittle

before heat-treatment. This white structure is achieved by keeping the

silicon content low, usually not much more than 1.0%, whilst in the

Whiteheart process some sulphur, too, is permissible, thus increasing still

further the stability of the cementite.

75.72.7.

Blackheart

Malleable

Iron castings are manufactured from white

iron of which the following composition is typical:

Carbon 2.5%

Silicon 1.0%

Manganese 0.4%

Sulphur 0.08%

Phosphorus 0.1%

In the original process the castings were fettled and placed in white-iron

containers along with some non-reactive material, such as gravel or cinders,

to act as a mechanical support. The lids were luted on to exclude air and

the containers loaded into an annealing furnace which was fired by coal,

gas,

fuel oil or pulverised fuel. Treatment temperatures varied between

850 and 950

0

C and were dependent upon the desired quality of product

and the analysis of the original casting. The duration of heat-treatment

was between 50 and 170 hours, again depending upon the type of casting

and the analysis of the iron. The development of modern annealing fur-

naces in which castings need no longer be packed in an insulating material

has resulted in a reduction in heating and cooling-off times, so that mallea-

bilising can now be effected in 48 hours or less. Such furnaces are of the

continuous type in which a moving hearth carries the castings slowly

through a long furnace of small cross-section and in which a controlled

non-oxidising atmosphere is circulated.

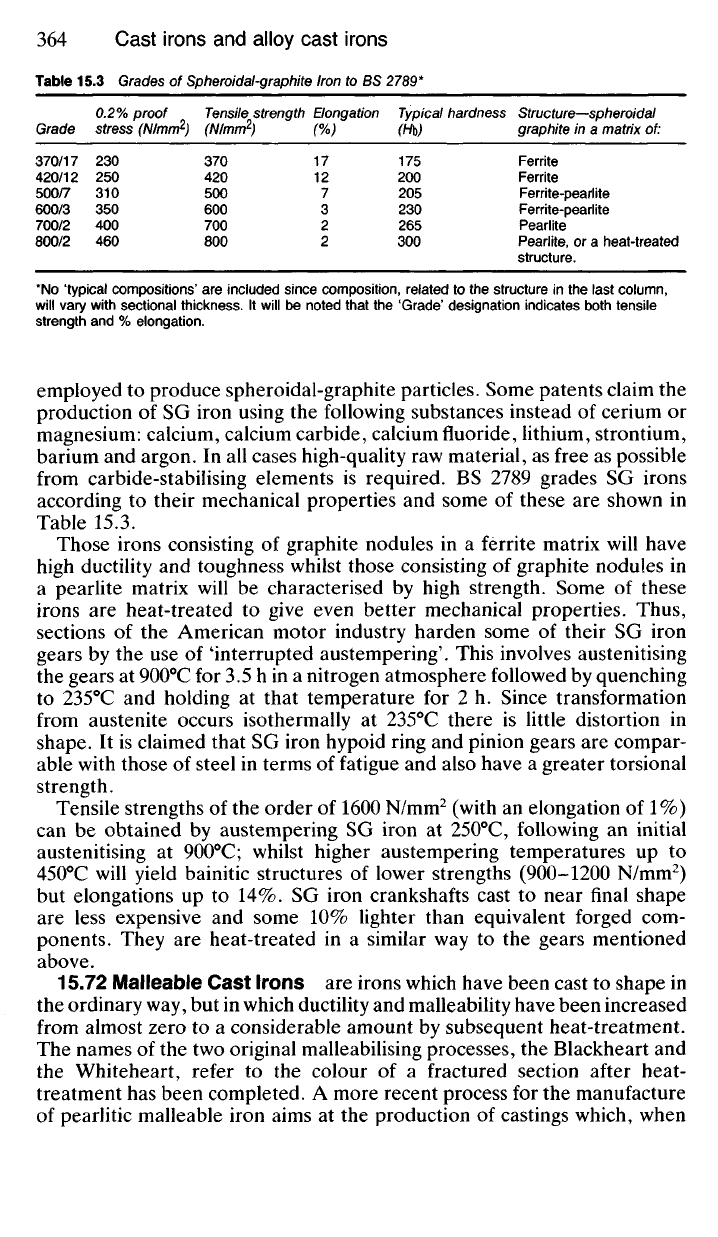

Plate 15.5 15.5A Blackheart malleable cast

iron.

'Rosettes' of temper carbon in a matrix of ferrite. x 60. Etched in 4% picral (Courtesy of

BCIRA)

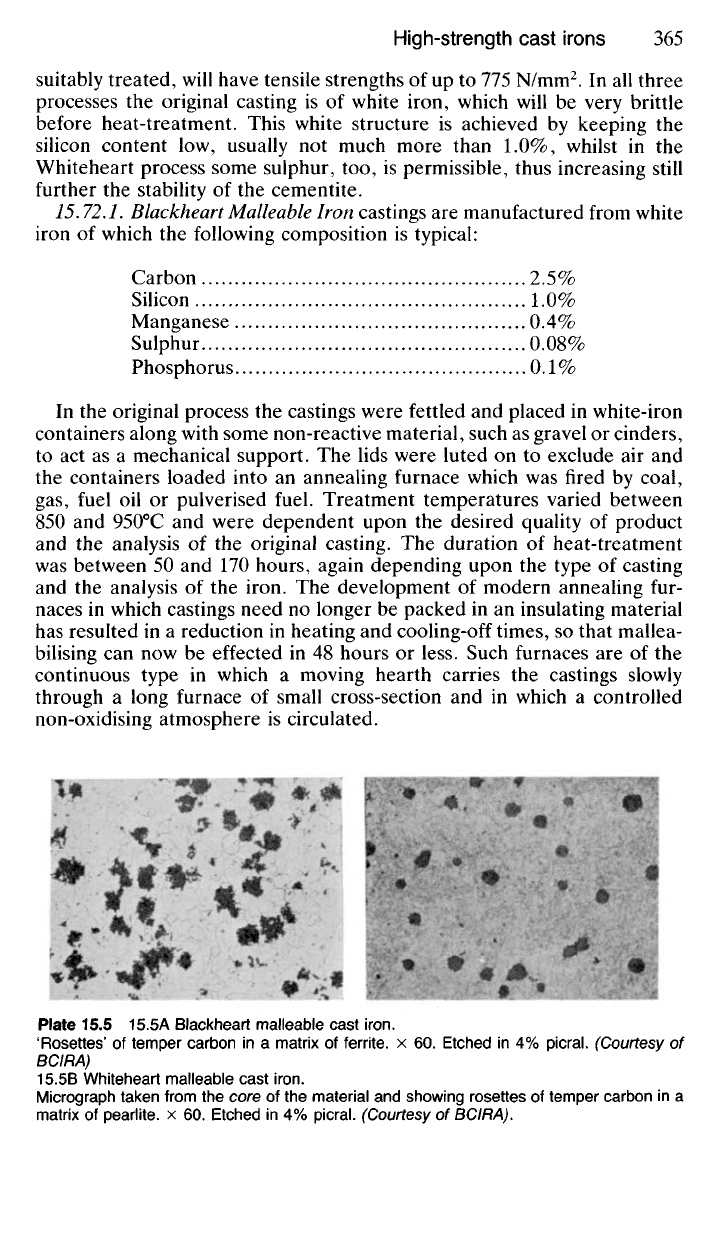

15.5B Whiteheart malleable cast

iron.

Micrograph taken from the core of the material and showing rosettes of temper carbon in a

matrix of pearlite. x 60. Etched in 4% picral. (Courtesy of BCIRA).