Higgins R.A. Engineering Metallurgy: Applied Physical Metallurgy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

xiv Contents

This page has been reformatted by Knovel to provide easier navigation.

9.5 Case IV – Two Metals Mutually Soluble in All

Proportions in the Liquid State But Only Partially

Soluble in the Solid State .............................................. 196

9.6 Case V – a System in Which a Peritectic

Transformation Is Involved ............................................ 200

9.7 Case VI – Systems Containing One or More

Intermediate Phase ....................................................... 202

9.8 Precipitation from a Solid Solution ................................ 206

9.9 Alloys Containing More Than Two Metals .................... 210

9.10 Rapid Solidification Processes (RSP) ........................... 211

9.11 Exercises ....................................................................... 212

9.12 Bibliography ................................................................... 217

10. Practical Metallography ............................................. 218

10.1 The Preparation of Specimens for Microscopical

Examination ................................................................... 219

10.2 The Metallurgical Microscope ........................................ 228

10.3 Macro-examination ........................................................ 234

10.4 Sulphur Printing ............................................................. 237

10.5 Exercises ....................................................................... 237

10.6 Bibliography ................................................................... 238

11. The Heat-treatment of Plain Carbon Steels – (I) ....... 239

11.1 Impurities in Steel .......................................................... 248

11.2 The Heat-treatment of Steel .......................................... 251

11.3 Annealing ....................................................................... 252

11.4 Normalising .................................................................... 257

11.5 Exercises ....................................................................... 257

11.6 Bibliography ................................................................... 258

12. The Heat-treatment of Plain Carbon Steels – (II) ...... 259

12.1 Hardening ...................................................................... 260

12.2 Tempering ...................................................................... 266

Contents xv

This page has been reformatted by Knovel to provide easier navigation.

12.3 Isothermal Transformations ........................................... 270

12.4 Hardenability and Ruling Section .................................. 279

12.5 British Standard Specifications for Carbon

Steels ............................................................................. 281

12.6 Exercises ....................................................................... 283

12.7 Bibliography ................................................................... 284

13. Alloy Steels ................................................................. 285

13.1 Nickel Steels .................................................................. 294

13.2 Chromium Steels ........................................................... 297

13.3 Nickel-Chromium Steels ................................................ 302

13.4 Steels Containing Molybdenum .................................... 309

13.5 Steels Containing Vanadium ......................................... 309

13.6 Heat-resisting Steels ..................................................... 312

13.7 Manganese Steels ......................................................... 317

13.8 Steels Containing Tungsten .......................................... 320

13.9 Steels Containing Cobalt ............................................... 324

13.10 Steels Containing Boron ................................................ 326

13.11 Steels Containing Silicon ............................................... 328

13.12 Steels Containing Copper ............................................. 328

13.13 HSLA and Other 'Micro-alloyed' Steels ......................... 330

13.14 Exercises ....................................................................... 331

13.15 Bibliography ................................................................... 332

14. Complex Ferrous Alloys ............................................ 333

14.1 High-speed Steels ......................................................... 333

14.2 Cemented Carbide and Other 'Cermet' Cutting

Materials ........................................................................ 340

14.3 Magnetic Properties and Materials ................................ 341

14.4 Exercises ....................................................................... 351

14.5 Bibliography ................................................................... 352

xvi Contents

This page has been reformatted by Knovel to provide easier navigation.

15. Cast Irons and Alloy Cast Irons ................................. 353

15.1 The Effects of Composition on the Structure of

Cast Iron ........................................................................ 354

15.2 The Effect of Rate of Cooling on the Structure of

Cast Iron ........................................................................ 357

15.3 The Microstructure of Cast Iron ..................................... 360

15.4 'Growth' in Cast Irons .................................................... 360

15.5 Varieties and Uses of Ordinary Cast Iron ..................... 361

15.6 High-strength Cast Irons ............................................... 362

15.7 Alloy Cast Irons .............................................................. 371

15.8 Exercises ....................................................................... 372

15.9 Bibliography ................................................................... 373

16. Copper and the Copper-base Alloys ......................... 374

16.1 Properties and Uses of Copper ..................................... 375

16.2 The Copper-base Alloys ................................................ 378

16.3 The Brasses ................................................................... 378

16.4 The Tin Bronzes ............................................................ 387

16.5 Aluminium Bronze ......................................................... 392

16.6 Copper-Nickel Alloys ..................................................... 397

16.7 Copper Alloys Which Can Be Precipitation

Hardened ....................................................................... 399

16.8 'Shape Memory' Alloys .................................................. 402

16.9 Exercises ....................................................................... 404

16.10 Bibliography ................................................................... 404

17. Aluminium and Its Alloys ........................................... 406

17.1 Alloys of Aluminium ....................................................... 408

17.2 Wrought Alloys Which Are Not Heat-treated ................ 412

17.3 Cast Alloys Which Are Not Heat-treated ....................... 413

17.4 Wrought Alloys Which Are Heat-treated ....................... 415

17.5 Cast Alloys Which Are Heat-treated .............................. 424

Contents xvii

This page has been reformatted by Knovel to provide easier navigation.

17.6 Exercises ....................................................................... 428

17.7 Bibliography ................................................................... 429

18. Other Non-ferrous Metals and Alloys ....................... 430

18.1 Magnesium-base Alloys ................................................ 430

18.2 Zinc-base Die-casting Alloys ......................................... 431

18.3 Nickel-Chromium High-temperature Alloys ................... 437

18.4 Bearing Metals ............................................................... 441

18.5 Fusible Alloys ................................................................. 447

18.6 Titanium and Its Alloys .................................................. 447

18.7 Uranium ......................................................................... 452

18.8 Some Uncommon Metals .............................................. 455

18.9 Exercises ....................................................................... 460

18.10 Bibliography ................................................................... 461

19. The Surface Hardening of Steels ............................... 462

19.1 Case-hardening ............................................................. 462

19.2 Case-hardening Steels .................................................. 470

19.3 Nitriding .......................................................................... 472

19.4 Surface Hardening by Localised Heat-treatment .......... 477

19.5 Friction Surfacing ........................................................... 478

19.6 Exercises ....................................................................... 479

19.7 Bibliography ................................................................... 480

20. Metallurgical Principles of the Joining of

Metals .......................................................................... 481

20.1 Soldering ........................................................................ 482

20.2 Brazing ........................................................................... 486

20.3 Welding .......................................................................... 488

20.4 Fusion Welding Processes ............................................ 489

20.5 Solid-phase Welding ...................................................... 494

20.6 The Microstructure of Welds ......................................... 496

20.7 The Inspection and Testing of Welds ............................ 497

xviii Contents

This page has been reformatted by Knovel to provide easier navigation.

20.8 The Weldability of Metals and Alloys ............................ 499

20.9 Exercises ....................................................................... 504

20.10 Bibliography ................................................................... 504

21. Metallic Corrosion and Its Prevention ...................... 506

21.1 The Mechanism of Corrosion ........................................ 507

21.2 Electrolytic Action or Wet Corrosion Involving

Mechanical Stress ......................................................... 518

21.3 Electrolytic Action or Wet Corrosion Involving

Electrolytes of Non-uniform Composition ...................... 520

21.4 The Prevention of Corrosion ......................................... 523

21.5 The Use of a Metal or Alloy Which Is Inherently

Corrosion-resistant ........................................................ 524

21.6 Protection by Metallic Coatings ..................................... 525

21.7 Protection by Oxide Coatings ........................................ 530

21.8 Protection by Other Non-metallic Coatings ................... 532

21.9 Cathodic Protection ....................................................... 535

21.10 Exercises ....................................................................... 536

21.11 Bibliography ................................................................... 537

Answers to Numerical Problems ..................................... 538

Index ................................................................................... 541

1

Some Fundamental

Chemistry

1.10 Towards the end of the fifteenth century the technology of shipbuild-

ing was sufficiently advanced in Europe to allow Columbus to sail west

into the unknown in a search for a new route to distant Cathay. Earlier

that century far to the east in Samarkand in the empire of Tamerlane,

the astronomer Ulug Beg was constructing his great sextant—the massive

quadrant of which we can still see to-day—to measure the period of our

terrestrial year. He succeeded in this enterprise with an error of only 58

seconds, a fact which the locals will tell you with pride. Yet at that time

only seven metals were known to man—copper, silver, gold, mercury,

iron, tin and lead; though some of them had been mixed to produce alloys

like bronze (copper and tin), pewter (tin and lead) and steel (iron and

carbon).

By 1800 the number of known metals had risen to 23 and by the begin-

ning of the twentieth century to 65. Now, all 70 naturally occurring metallic

elements are known to science and an extra dozen or so have been created

by man from the naturally occurring radioactive elements by various pro-

cesses of 'nuclear engineering'. Nevertheless metallurgy, though a modern

science, has its roots in the ancient crafts of smelting, shaping and treat-

ment of metals. For several hundreds of years smiths had been hardening

steel using heat-treatment processes established painstakingly by trial and

error, yet it is only during this century that metallurgists discovered how

the hardening process worked. Likewise during the First World War the

author's father, then in the Royal Flying Corps, was working with fighter

aeroplanes the engines of which relied on 'age-hardening' aluminium

alloys; but it was quite late in the author's life before a plausible expla-

nation of age-hardening was forthcoming.

Since the days of the Great Victorians there has been an upsurge in

metallurgical research and development, based on the fundamental

sciences of physics and chemistry. To-day a vast reservoir of metallurgical

knowledge exists and the metallurgist is able to design materials to meet

the ever exacting demands of the engineer. Sometimes these demands are

over optimistic and it is hoped that this book may help the engineer to

appreciate the limitations, as well as the expanding range of properties, of

modern alloys.

1.11 Whilst steel is likely to remain the most important metallurgical

material available to the engineer we must not forget the wide range of

relatively sophisticated alloys which have been developed during this cen-

tury. As a result of such development an almost bewildering list of alloy

compositions confronts the engineer in his search for an alloy which will

be both technically and economically suitable for his needs. Fortunately

most of the useful alloys have been classified and rigid specifications laid

down for them by such official bodies as the British Standards Institution

(BSI) and in the USA, the American Society for Testing Materials

(ASTM). Now that we are in Europe' such bodies as Association Frangaise

de Normalisation (AFNOR) and Deutscher Normenausschuss (DNA) also

become increasingly involved.

Sadly, it may be that like many of our public libraries here in the Midlands,

your local library contains proportionally fewer books on technological mat-

ters than it did fifty years ago, and that meagre funds have been expended

on works dealing with the private life of Gazza—or the purple passion publi-

cations of Mills and Boon. Nevertheless at least one library in your region

should contain, by national agreement, a complete set of British Standards

Institution Specifications. In addition to their obvious use, these are a valu-

able mine of information on the compositions and properties of all of our

commercial alloys and engineering materials. A catalogue of all Specifi-

cation Numbers will be available at the information desk. Hence, forearmed

with the necessary metallurgical knowledge, the engineer is able to select an

alloy suitable to his needs and to quote its relevant specification index when

the time comes to convert design into reality.

Atoms,

Elements and Compounds

1.20 It would be difficult to study metallurgy meaningfully without relat-

ing mechanical properties to the elementary forces acting between the

atoms of which a metal is composed. We shall study the structures of atoms

later in the chapter but it suffices at this stage to regard these atoms as tiny

spheres held close to one another by forces of attraction.

1.21 If in a substance all of these atoms are of the same type then the

substance is a chemical element. Thus the salient property of a chemical

element is that it cannot be split up into simpler substances whether by

mechanical or chemical means. Most of the elements are chemically reac-

tive,

so that we find very few of them in their elemental state in the Earth's

crust—oxygen and nitrogen mixed together in the atmosphere are the most

common, whilst a few metals such as copper, gold and silver, also occur

uncombined. Typical substances occurring naturally contain atoms of two

or more kinds.

1.22

Most of the substances we encounter are either chemical com-

pounds or mixtures. The difference between the two is that a compound

is formed when there is a chemical join at the surfaces of two or more

different atoms, whilst in a mixture only mechanical 'entangling' occurs

between discrete particles of the two substances. For example, the pow-

dered element sulphur can be mixed with iron filings and easily separated

again by means of a magnet, but if the mixture is gently heated a vigorous

chemical reaction proceeds and a compound called iron sulphide is formed.

This is different in appearance from either of the parent elements and its

decomposition into the parent elements, sulphur and iron, is now more

difficult and can be accomplished only be chemical means.

1.23 Chemical elements can be represented by a symbol which is usu-

ally an abbreviation of either the English or Latin name, eg O stands

for oxygen whilst Fe stands for 'ferrum', the Latin equivalent of iron'.

Ordinarily, a symbol written thus refers to a single atom of the element,

whilst two atoms (constituting what in this instance we call a molecule)

would be indicated so: O2.

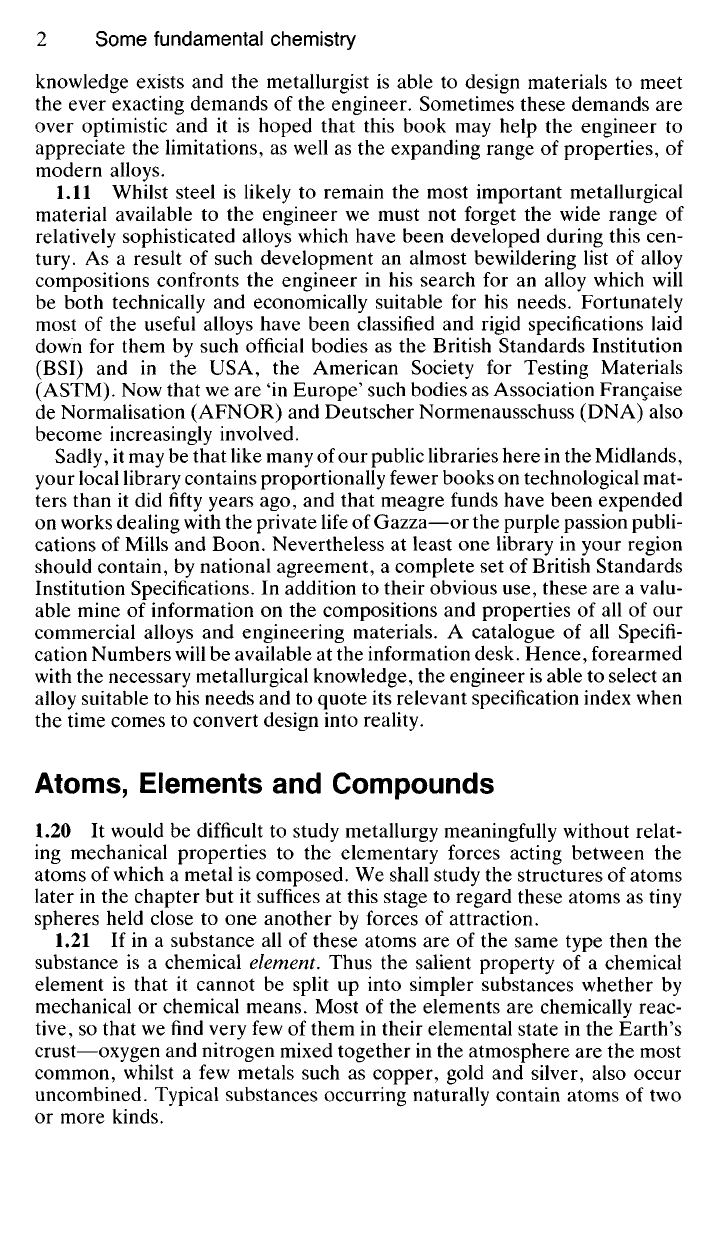

1.24 Table 1.1 includes some of the more important elements we are

likely to encounter in a study of metallurgy. The term 'relative atomic

mass',

(formerly 'atomic weight'), mentioned in this table must not be con-

fused with the relative density of the element. The latter value will depend

upon how closely the atoms, whether small or large, are packed together.

Since atoms are very small particles (the mass of the hydrogen atom is

1.673 x 10~

27

kg), it would be inconvenient to use such small values in

everyday chemical calculations. Consequently, since the hydrogen atom

was known to be the smallest, its relative mass was taken as unity and the

relative masses of the atoms of other elements calculated as multiples of

this.

Thus relative atomic mass became

mass of one atom of the element

mass of one atom of hydrogen

Later it was found more useful to adjust the relative atomic mass of oxygen

(by far the most common element) to exactly 16.0000. On this basis the

relative atomic mass of hydrogen became 1.008 instead of

1.0000.

More

recently chemists and physicists have agreed to relate atomic masses to

that of the carbon isotope (C = 12.0000). (See paragraph

1.90.)

1.25 The most common metallic element in the Earth's crust is alu-

minium (Table 1.2) but as a commercially usable metal it is not the cheap-

est. This is because clay, the most abundant mineral containing aluminium,

is very difficult—and therefore costly—to decompose chemically. There-

fore our aluminium supply comes from the mineral bauxite (originally

mined near the village of Les Baux, in France), which is a relatively scarce

ore.

It will be seen from the table that apart from iron most of the useful

metallic elements account for only a very small proportion of the Earth's

crust. Fortunately they occur in relatively concentrated deposits which

makes their mining and extraction economically possible.

In passing it is interesting to note that in the Universe as a whole hydro-

Table 1.1

Element

Aluminium

Antimony

Argon

Arsenic

Barium

Beryllium

Bismuth

Boron

Cadmium

Calcium

Carbon

Cerium

Chlorine

Chromium

Cobalt

Copper

Dysprosium

Erbium

Symbol

Al

Sb

Ar

As

Ba

Be

Bi

B

Cd

Ca

C

Ce

Cl

Cr

Co

Cu

Dy

Er

Relative

atomic

weight

(C =

12.0000)

26.98

121.75

39.948

74.92

137.34

9.012

208.98

10.811

112.4

40.08

12.011

140.12

35.45

51.996

58.933

63.54

162.5

167.26

Relative

Density

(Specific

Gravity)

2.7

6.6

1.78 x

10~

3

5.7

3.5

1.8

9.8

2.3

8.6

1.5

2.2

6.9

3.2 x

10-

3

7.1

8.9

8.9

8.5

9.1

Melting

point

CC)

659.7

630.5

-189.4

814

850

1285

271.3

2300

320.9

845

640

-103

1890

1495

1083

1412

1529

Properties and Uses

The most widely used of the light metals.

A brittle, crystalline metal which, however, is

used in bearings and type.

An inert gas present in small amounts in the

atmosphere. Used in 'argon-arc' welding.

A black crystalline element—used to harden

copper at elevated temperatures.

Its compounds are useful because of their

fluorescent properties.

A light metal which is used to strengthen

copper. Also used un-alloyed in atomic-energy

plant.

A metal similar to antimony in many ways—

used in the manufacture of fusible

(low-melting-point) alloys.

Known chiefly in the form of its compound,

'borax'.

Used for plating some metals and alloys and

for strengthening copper telephone wires.

A very reactive metal met chiefly in the form

of its oxide, 'quicklime'.

The basis of all fuels and organic substances

and an essential ingredient of steel.

A 'rare-earth' metal. Used as an 'inoculant' in

cast

iron,

and in the manufacture of lighter

flints.

A poisonous reactive gas, used in the

de-gasification of light alloys.

A metal which resists corrosion—hence it is

used for plating and in stainless steels and

other corrosion-resistant alloys.

Used chiefly in permanent magnets and in

high-speed steel.

A metal of high electrical conductivity which is

used widely in the electrical industries and in

alloys such as bronzes and brasses.

Present in the 'rare earths', used in some

magnesium-base alloys.

A silvery-white metal. Present in the 'rare

earths', used in some magnesium alloys and

also used in cancer-therapy generators.

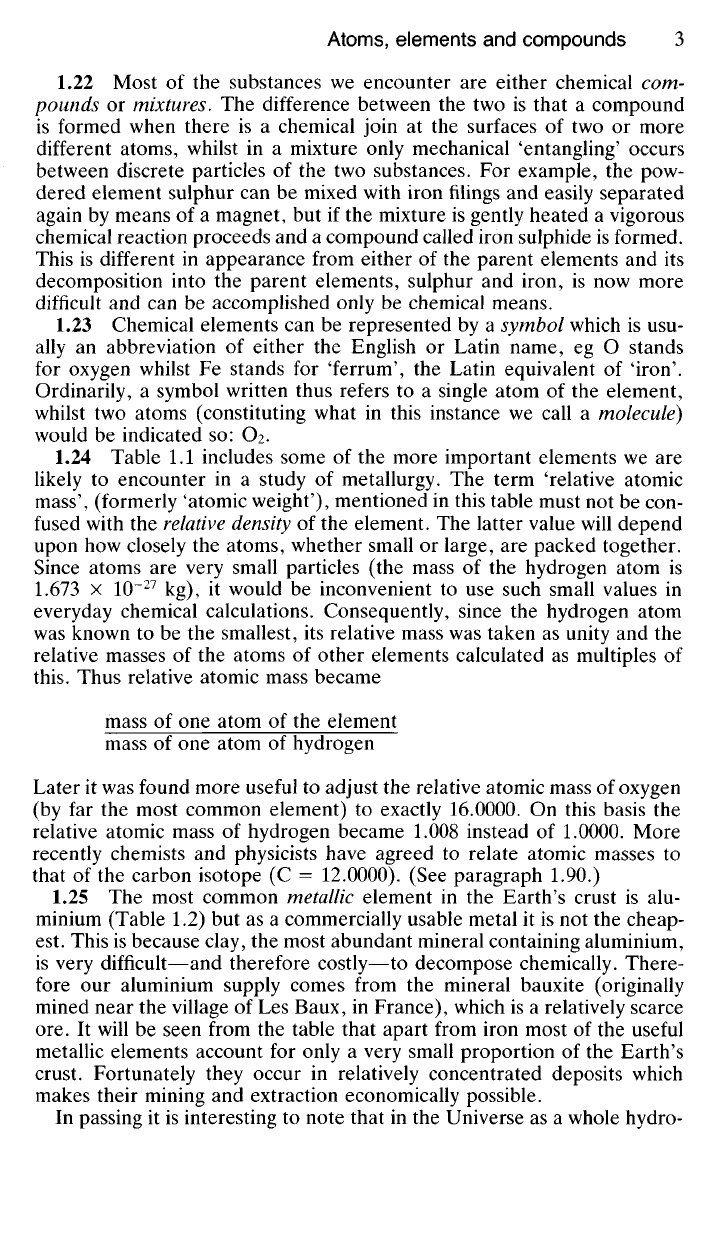

Table 1.1 {continued)

Element

Gadolinium

Gold

Helium

Hydrogen

Indium

lridium

Iron

Lanthanum

Lead

Magnesium

Manganese

Mercury

Molybdenum

Neodymium

Nickel

Niobium

Nitrogen

Osmium

Symbol

Gd

Au

He

H

In

Ir

Fe

La

Pb

Mg

Mn

Hg

Mo

Nd

Ni

Nb

N

Os

Relative

atomic

weight

(C =

12.0000)

157.25

196.967

4.0026

1.00797

114.82

192.2

55.847

138.91

207.69

24.312

54.938

200.59

95.94

144.24

58.71

92.906

14.0067

190.2

Relative

Density

(Specific

Gravity)

7.9

19.3

0.16 x

10~

3

0.09 x

10"

3

7.3

22.4

7.9

6.1

11.3

1.7

7.2

13.6

10.2

7.0

8.9

8.6

1.16 x

10~

3

22.5

Melting

point

CC)

1313

1063

Below

-272

-259

156.6

2454

1535

920

327.4

651

1260

-38.8

2620

1021

1458

1950

-210

2700

Properties and Uses

Used in some modern permanent magnet

alloys. Also present in the 'rare earths' used

in some magnesium-base alloys.

Of little use in engineering, but mainly as a

system of exchange and in jewellery.

A light non-reactive gas present in small

amounts in the atmosphere.

The lightest element and a constituent of most

gaseous fuels.

A very soft greyish metal used as a

corrosion-resistant coating also used in some

low melting point solders, and in

semiconductors.

A heavy precious metal similar to platinum.

A fairly soft white metal when pure, but rarely

used thus in engineering.

Used in some high-temperature alloys.

Not the densest of metals, as the metaphor

'as heavy as

lead'

suggests.

Used along with aluminium in the lightest of

alloys.

Similar in many ways to iron and widely used

in steel as a deoxidant.

The only liquid metal at normal temperatures

—known as 'quicksilver'.

A heavy metal used in alloy steels.

A yellowish-white metal. Used in some

heat-treatable magnesium-base alloys and in

some permanent magnet alloys.

An adaptable metal used in a wide variety of

ferrous and non-ferrous alloys.

Used in steels and, un-alloyed, in

atomic-energy plant. Formerly called

'Columbium' in the United States.

Comprises about 4/5 of the atmosphere. Can

be made to dissolve in the surface of steel

and so harden it.

The densest element and a rare white metal

like platinum.