Higgins R.A. Engineering Metallurgy: Applied Physical Metallurgy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

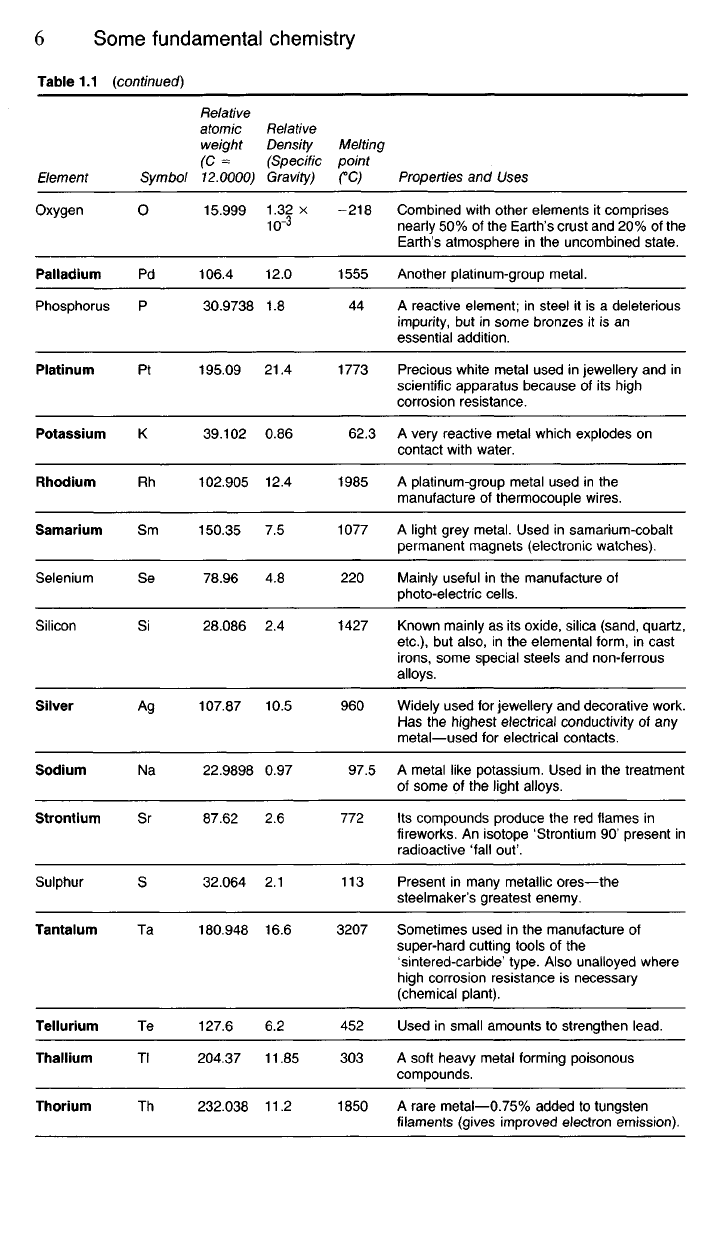

Table 1.1 {continued)

Element

Oxygen

Palladium

Phosphorus

Platinum

Potassium

Rhodium

Samarium

Selenium

Silicon

Silver

Sodium

Strontium

Sulphur

Tantalum

Tellurium

Thallium

Thorium

Symbol

O

Pd

P

Pt

K

Rh

Sm

Se

Si

Ag

Na

Sr

S

Ta

Te

Tl

Th

Relative

atomic

weight

(C =

12.0000)

15.999

106.4

30.9738

195.09

39.102

102.905

150.35

78.96

28.086

107.87

22.9898

87.62

32.064

180.948

127.6

204.37

232.038

Relative

Density

(Specific

Gravity)

1.32 x

10"

3

12.0

1.8

21.4

0.86

12.4

7.5

4.8

2.4

10.5

0.97

2.6

2.1

16.6

6.2

11.85

11.2

Melting

point

CC)

-218

1555

44

1773

62.3

1985

1077

220

1427

960

97.5

772

113

3207

452

303

1850

Properties and Uses

Combined with other elements it comprises

nearly 50% of the Earth's crust and 20% of the

Earth's atmosphere in the uncombined state.

Another platinum-group metal.

A reactive element; in steel it is a deleterious

impurity, but in some bronzes it is an

essential addition.

Precious white metal used in jewellery and in

scientific apparatus because of its high

corrosion resistance.

A very reactive metal which explodes on

contact with

water.

A platinum-group metal used in the

manufacture of thermocouple wires.

A light grey metal. Used in samarium-cobalt

permanent magnets (electronic watches).

Mainly useful in the manufacture of

photo-electric cells.

Known mainly as its oxide, silica (sand, quartz,

etc.),

but also, in the elemental form, in cast

irons,

some special steels and non-ferrous

alloys.

Widely used for jewellery and decorative work.

Has the highest electrical conductivity of any

metal—used for electrical contacts.

A metal like potassium. Used in the treatment

of some of the light alloys.

Its compounds produce the red flames in

fireworks. An isotope 'Strontium 90' present in

radioactive 'fall out'.

Present in many metallic ores—the

steelmaker's greatest enemy.

Sometimes used in the manufacture of

super-hard cutting tools of the

'sintered-carbide' type. Also unalloyed where

high corrosion resistance is necessary

(chemical plant).

Used in small amounts to strengthen

lead.

A soft heavy metal forming poisonous

compounds.

A rare metal—0.75% added to tungsten

filaments (gives improved electron emission).

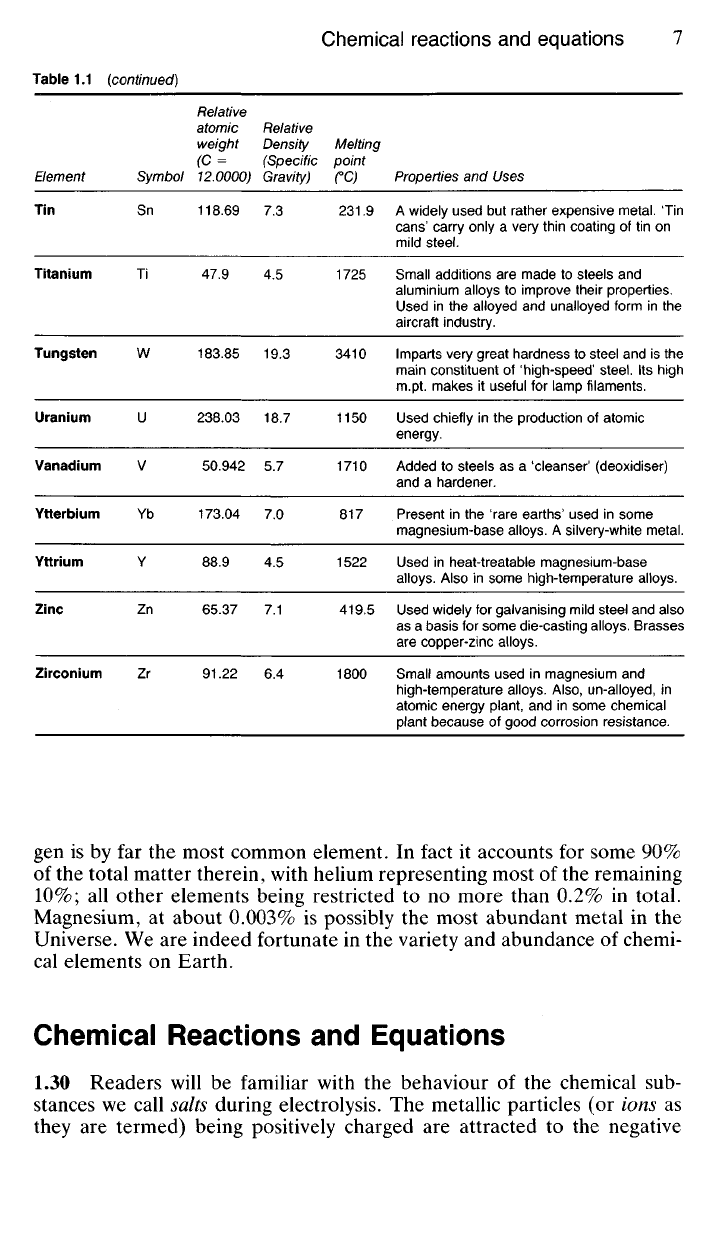

Table 1.1 (continued)

Element

Tin

Titanium

Tungsten

Uranium

Vanadium

Ytterbium

Yttrium

Zinc

Zirconium

Symbol

Sn

Ti

W

U

V

Yb

Y

Zn

Zr

Relative

atomic

weight

(C =

12.0000)

118.69

47.9

183.85

238.03

50.942

173.04

88.9

65.37

91.22

Relative

Density

(Specific

Gravity)

7.3

4.5

19.3

18.7

5.7

7.0

4.5

7.1

6.4

Melting

point

(

0

C)

231.9

1725

3410

1150

1710

817

1522

419.5

1800

Properties and Uses

A widely used but rather expensive metal. Tin

cans'

carry only a very thin coating of tin on

mild steel.

Small additions are made to steels and

aluminium alloys to improve their properties.

Used in the alloyed and unalloyed form in the

aircraft industry.

Imparts very great hardness to steel and is the

main constituent of 'high-speed' steel. Its high

m.pt. makes it useful for lamp filaments.

Used chiefly in the production of atomic

energy.

Added to steels as a 'cleanser' (deoxidiser)

and a hardener.

Present in the 'rare earths' used in some

magnesium-base alloys. A silvery-white metal.

Used in heat-treatable magnesium-base

alloys. Also in some high-temperature alloys.

Used widely for galvanising mild steel and also

as a basis for some die-casting alloys. Brasses

are copper-zinc alloys.

Small amounts used in magnesium and

high-temperature alloys. Also, un-alloyed, in

atomic energy plant, and in some chemical

plant because of good corrosion resistance.

gen is by far the most common element. In fact it accounts for some 90%

of the total matter therein, with helium representing most of the remaining

10%;

all other elements being restricted to no more than 0.2% in total.

Magnesium, at about 0.003% is possibly the most abundant metal in the

Universe. We are indeed fortunate in the variety and abundance of chemi-

cal elements on Earth.

Chemical Reactions and Equations

1.30 Readers will be familiar with the behaviour of the chemical sub-

stances we call salts during electrolysis. The metallic particles (or ions as

they are termed) being positively charged are attracted to the negative

electrode (or cathode), whilst the non-metallic ions being negatively

charged are attracted to the positive electrode (or anode). Because of the

behaviour of their respective ions metals are said to be electropositive and

non-metals electronegative.

In general elements react or combine with each other when they possess

opposite chemical natures. Thus the more electropositive a metal the more

readily will it combine with a non-metal, forming a very stable compound.

If one metal is more strongly electropositive than another the two may

combine forming what is called an intermetallic compound, though usually

they only mix with each other forming what is in effect a 'solid solution'.

This constitutes the basis of most useful alloys.

1.31 Atoms combine with each other in simple fixed proportions. For

example, one atom of the gas chlorine (Cl) will combine with one atom of

the gas hydrogen (H) to form one molecule of the gas hydrogen chloride.

We can write down a formula for hydrogen chloride which expresses at a

glance its molecular constitution, viz. HCl. Since one atom of chlorine will

combine with one atom of hydrogen, its valence is said to be one, the term

valence denoting the number of atoms of hydrogen which will combine

with one atom of the element in question. Again, two atoms of hydrogen

combine with one atom of oxygen to form one molecule of water (H

2

O),

so that the valence of oxygen is two. Similarly, four atoms of hydrogen

will combine with one atom of carbon to form one molecule of methane

(CH

4

).

Hence the valence of carbon in this instance is four. However,

carbon, like several other elements, exhibits a variable valence, since it will

also form the substances ethene (C

2

H

4

), formerly 'ethylene', and ethine

(C

2

H

2

),

formerly acetylene.

1.32 Compounds also react with each other in simple proportions, and

we can express such a reaction in the form of a chemical equation thus:

CaO + 2HCl = CaCl

2

+ H

2

O

Table 1.2 The Approximate Composition of the Earth's Crust (to the Extent of Mining Operations)

Element

Oxygen

Silicon

Aluminium

Iron

Calcium

Sodium

Potassium

Magnesium

Hydrogen

Titanium

Carbon

Chlorine

Phosphorus

Manganese

Sulphur

Barium

Nitrogen

Chromium

% by mass

49.1

26.0

7.4

4.3

3.2

2.4

2.3

2.3

1.0

0.61

0.35

0.20

0.12

0.10

0.10

0.05

0.04

0.03

Element

Nickel

Vanadium

Zinc

Copper

Tin

Boron

Cobalt

Lead

Molybdenum

Tungsten

Cadmium

Beryllium

Uranium

Mercury

Silver

Gold

Platinum

Radium

% by mass

0.02

0.02

0.02

0.01

0.008

0.005

0.002

0.002

0.001

9 x 10"

4

5 x 10"

4

4 x 10"

4

4 x 10"

4

1 x 10"

4

1 x 10~

5

5 x 10"

6

5 x 10"

6

2 x 1O~

10

The above equation tells us that one chemical unit of calcium oxide (CaO

or 'quicklime') will react with two chemical units of hydrogen chloride

(HCl or hydrochloric acid), to produce one chemical unit of calcium chlor-

ide (CaCb) and one chemical unit of water (H2O). Though the total

number of chemical units may change due to the reaction—we began with

three units and ended with two—the total number of atoms remains the

same on either side of the equation. The equation must balance rather like

a financial balance sheet.

1.33 By substituting the appropriate atomic masses (approximated

values from Table 1.1) in the above equation we can obtain further useful

information from it.

Thus,

56 parts by weight of quicklime will react with 73 parts by weight of

hydrogen chloride to produce 111 parts by weight of calcium chloride and

18 parts by weight of water. Naturally, instead of 'parts by weight' we can

use grams, kilograms or tonnes as required.

We will now deal with some chemical reactions relevant to a study of

metallurgy.

Oxidation and Reduction

1.40 Oxidation is one of the most common of chemical processes. It

refers,

in its simplest terms, to the combination between oxygen and any

other element—a phenomenon which is taking place all the time around

us.

In our daily lives we make constant use of oxidation. We inhale

atmospheric oxygen and reject carbon dioxide (CO

2

)—the oxygen we

breathe combines with carbon from our animal tissues, releasing energy in

the process. We then reject the waste carbon dioxide. Similarly, heat

energy can be produced by burning carbonaceous materials, such as coal

or petroleum. Just as without breathing oxygen animals cannot live, so

without an adequate air supply fuel cannot burn. In these reactions carbon

and oxygen have combined to form a gas, carbon dioxide (CO

2

), and at

the same time heat energy has been released—the 'energy potential' of

the carbon having fallen in the process.

1.41 Oxidation, however, is also a phenomenon which works to our

disadvantage, particularly in so far as the metallurgist is concerned, since

a large number of otherwise useful metals show a great affinity for oxygen

and combine with it whenever they are able. This is particularly so at high

temperatures so that the protection of metal surfaces by means of fluxes

is often necessary during melting and welding operations. Although cor-

rosion is generally a more complex phenomenon, oxidation is always

involved and expensive processes such as painting, plating or galvanising

must be used to protect the metallic surface.

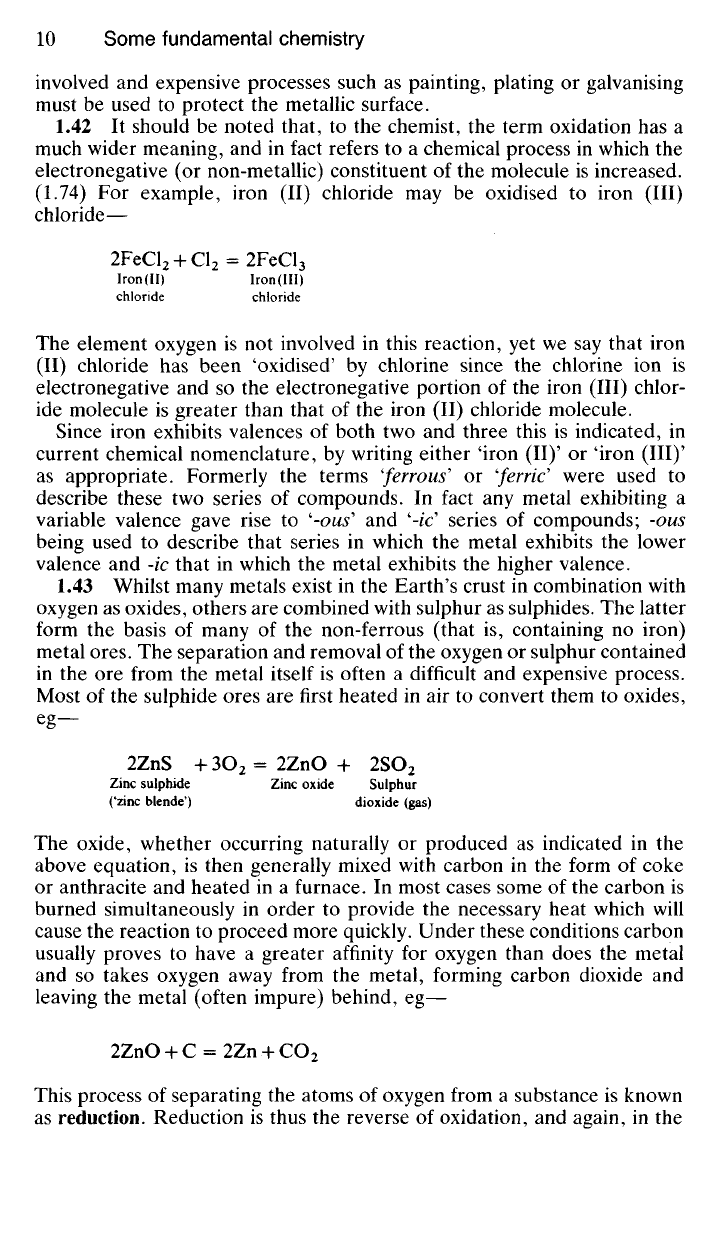

1.42 It should be noted that, to the chemist, the term oxidation has a

much wider meaning, and in fact refers to a chemical process in which the

electronegative (or non-metallic) constituent of the molecule is increased.

(1.74) For example, iron (II) chloride may be oxidised to iron (III)

chloride—

2FeCl

2

+ Cl

2

= 2FeCl

3

Iron(II) Iron(III)

chloride chloride

The element oxygen is not involved in this reaction, yet we say that iron

(II) chloride has been 'oxidised' by chlorine since the chlorine ion is

electronegative and so the electronegative portion of the iron (III) chlor-

ide molecule is greater than that of the iron (II) chloride molecule.

Since iron exhibits valences of both two and three this is indicated, in

current chemical nomenclature, by writing either iron (II)' or 'iron (III)'

as appropriate. Formerly the terms 'ferrous' or 'ferric' were used to

describe these two series of compounds. In fact any metal exhibiting a

variable valence gave rise to '-ous' and '-/c' series of compounds; -ous

being used to describe that series in which the metal exhibits the lower

valence and -ic that in which the metal exhibits the higher valence.

1.43 Whilst many metals exist in the Earth's crust in combination with

oxygen as oxides, others are combined with sulphur as sulphides. The latter

form the basis of many of the non-ferrous (that is, containing no iron)

metal ores. The separation and removal of the oxygen or sulphur contained

in the ore from the metal itself is often a difficult and expensive process.

Most of the sulphide ores are first heated in air to convert them to oxides,

eg—

2ZnS + 3O

2

= 2ZnO + 2SO

2

Zinc sulphide Zinc oxide Sulphur

('zinc blende') dioxide (gas)

The oxide, whether occurring naturally or produced as indicated in the

above equation, is then generally mixed with carbon in the form of coke

or anthracite and heated in a furnace. In most cases some of the carbon is

burned simultaneously in order to provide the necessary heat which will

cause the reaction to proceed more quickly. Under these conditions carbon

usually proves to have a greater affinity for oxygen than does the metal

and so takes oxygen away from the metal, forming carbon dioxide and

leaving the metal (often impure) behind, eg—

2ZnO-HC = 2Zn+ CO

2

This process of separating the atoms of oxygen from a substance is known

as reduction. Reduction is thus the reverse of oxidation, and again, in the

wider chemical sense, it refers to a reaction in which the proportion of the

electronegative constituent of the molecule is decreased.

1.44 Some elements have greater affinities for oxygen than have others.

Their oxides are therefore more difficult to decompose. Aluminium and

magnesium, strongly electropositive metals, have greater affinities for oxy-

gen than has carbon, so that it is impossible to reduce their oxides in the

normal way using coke—electrolysis, a much more expensive process,

must be used. Metals, such as aluminium, magnesium, zinc, iron and lead,

which form stable, tenacious oxides are usually called base metals, whilst

those metals which have little affinity for oxygen are called noble metals.

Such metals include gold, silver and platinum, metals which will not scale

or tarnish to any appreciable extent due to the action of atmospheric

oxygen.

Acids,

Bases and Salts

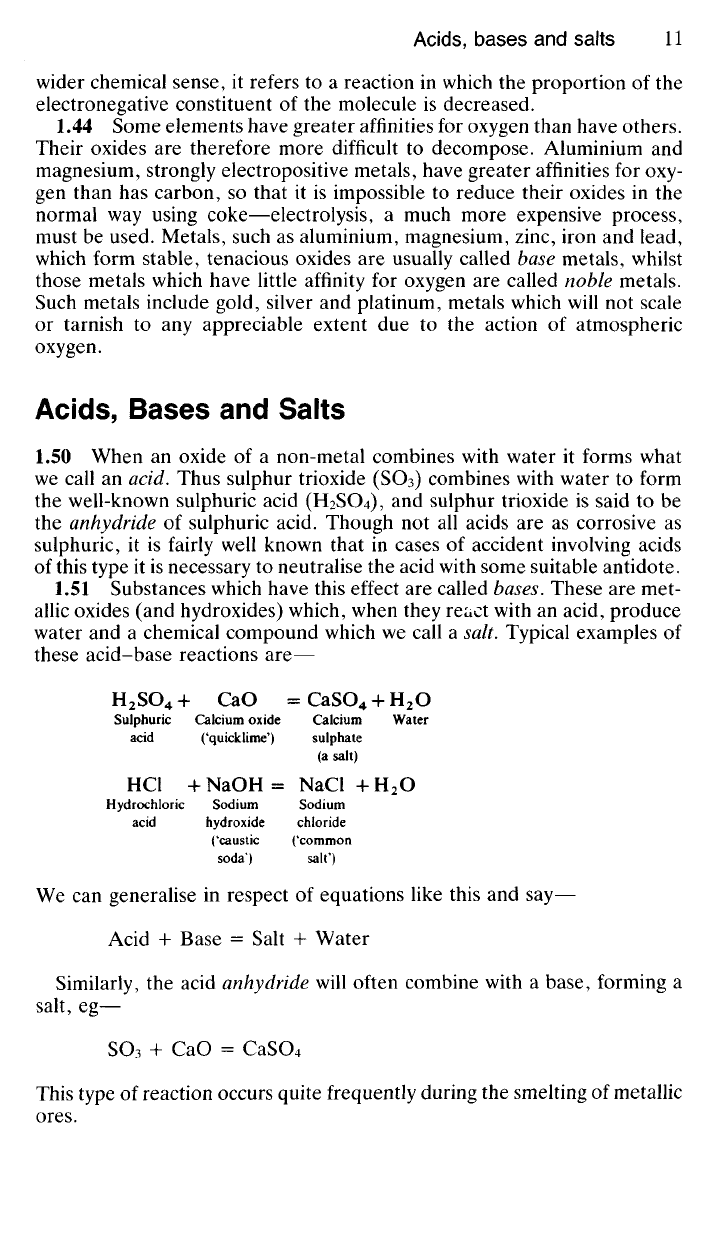

1.50 When an oxide of a non-metal combines with water it forms what

we call an

acid.

Thus sulphur trioxide (SO

3

) combines with water to form

the well-known sulphuric acid (H

2

SO

4

), and sulphur trioxide is said to be

the anhydride of sulphuric acid. Though not all acids are as corrosive as

sulphuric, it is fairly well known that in cases of accident involving acids

of this type it is necessary to neutralise the acid with some suitable antidote.

1.51 Substances which have this effect are called bases. These are met-

allic oxides (and hydroxides) which, when they react with an acid, produce

water and a chemical compound which we call a salt. Typical examples of

these acid-base reactions are—

H

2

SO

4

+ CaO = CaSO

4

+ H

2

O

Sulphuric Calcium oxide Calcium Water

acid ('quicklime') sulphate

(a salt)

HCl +NaOH= NaCl +H

2

O

Hydrochloric Sodium Sodium

acid hydroxide chloride

('caustic ('common

soda') salt')

We can generalise in respect of equations like this and say—

Acid + Base = Salt + Water

Similarly, the acid anhydride will often combine with a base, forming a

salt, eg—

SO

3

+ CaO = CaSO

4

This type of reaction occurs quite frequently during the smelting of metallic

ores.

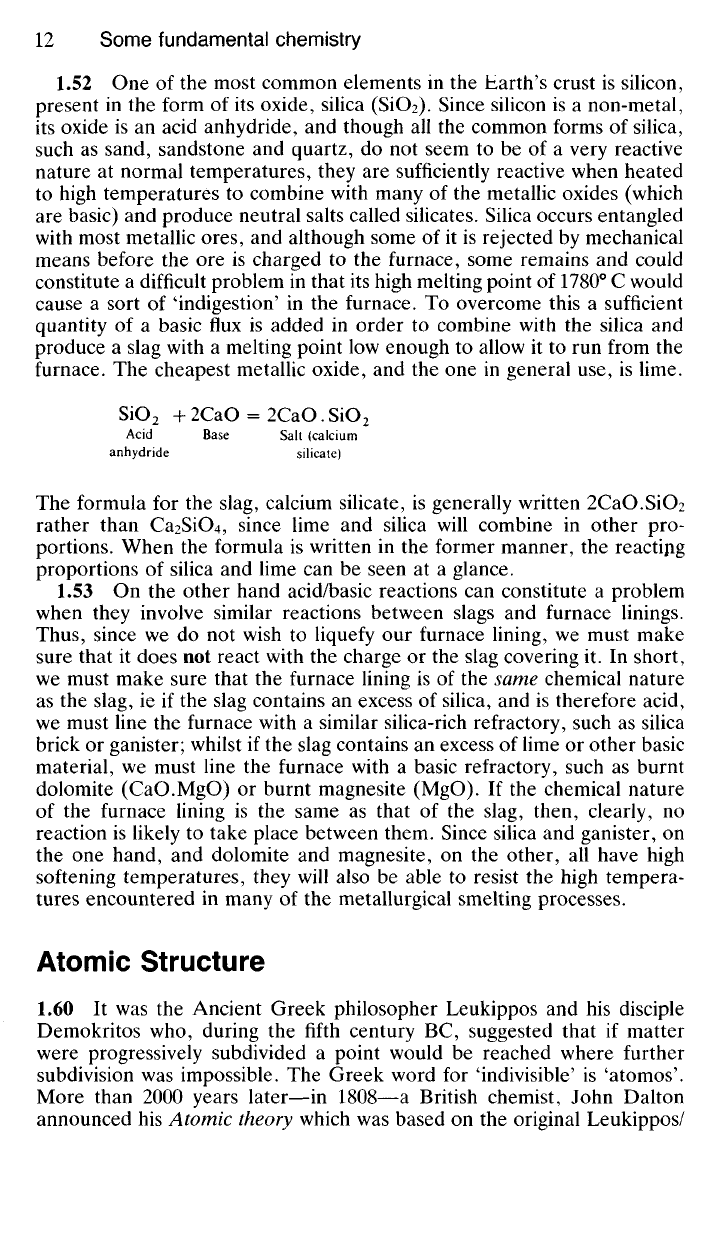

1.52

One of the most common elements in the Earth's crust is silicon,

present in the form of its oxide, silica (SiO

2

). Since silicon is a non-metal,

its oxide is an acid anhydride, and though all the common forms of silica,

such as sand, sandstone and quartz, do not seem to be of a very reactive

nature at normal temperatures, they are sufficiently reactive when heated

to high temperatures to combine with many of the metallic oxides (which

are basic) and produce neutral salts called silicates. Silica occurs entangled

with most metallic ores, and although some of it is rejected by mechanical

means before the ore is charged to the furnace, some remains and could

constitute a difficult problem in that its high melting point of 1780° C would

cause a sort of 'indigestion' in the furnace. To overcome this a sufficient

quantity of a basic flux is added in order to combine with the silica and

produce a slag with a melting point low enough to allow it to run from the

furnace. The cheapest metallic oxide, and the one in general use, is lime.

SiO

2

+2CaO = 2CaO. SiO

2

Acid Base Salt (calcium

anhydride silicate)

The formula for the slag, calcium silicate, is generally written 2CaO.SiO

2

rather than Ca

2

SiO4, since lime and silica will combine in other pro-

portions. When the formula is written in the former manner, the reacting

proportions of silica and lime can be seen at a glance.

1.53 On the other hand acid/basic reactions can constitute a problem

when they involve similar reactions between slags and furnace linings.

Thus,

since we do not wish to liquefy our furnace lining, we must make

sure that it does not react with the charge or the slag covering it. In short,

we must make sure that the furnace lining is of the same chemical nature

as the slag, ie if the slag contains an excess of silica, and is therefore acid,

we must line the furnace with a similar silica-rich refractory, such as silica

brick or ganister; whilst if the slag contains an excess of lime or other basic

material, we must line the furnace with a basic refractory, such as burnt

dolomite (CaO.MgO) or burnt magnesite (MgO). If the chemical nature

of the furnace lining is the same as that of the slag, then, clearly, no

reaction is likely to take place between them. Since silica and ganister, on

the one hand, and dolomite and magnesite, on the other, all have high

softening temperatures, they will also be able to resist the high tempera-

tures encountered in many of the metallurgical smelting processes.

Atomic Structure

1.60 It was the Ancient Greek philosopher Leukippos and his disciple

Demokritos who, during the fifth century BC, suggested that if matter

were progressively subdivided a point would be reached where further

subdivision was impossible. The Greek word for 'indivisible' is 'atomos'.

More than 2000 years later—in 1808—a British chemist, John Dalton

announced his Atomic theory which was based on the original Leukippos/

Demokritos idea. Dalton suggested that chemical reactions could be

explained if it was assumed that each chemical element consisted of

extremely small indivisible particles, which, following the Greek concept,

he called 'atoms'. The Theory was generally accepted but before the end

of the nineteenth century it was discovered that atoms were certainly not

indivisible. Thus the 'atom' is an ill-described particle. But the title became

so firmly established that it is retained to-day, though we usually modify

our description to add that it is 'the smallest stable particle of matter which

can exist'.

1.61 In 1897 the English physicist J. J. Thomson showed that a beam

of 'cathode rays' was in fact a stream of fast-moving negatively charged

particles—they were in fact electrons. Because the electron is negatively

charged it can be deflected from its path by an electrical field and we make

use of this feature in TV tubes where a beam of electrons, deflected by a

system of electro-magnetic fields, builds up a picture by impingement on

a screen which will fluoresce under the impact of electrons. Thomson was

able to make only a rough estimate of the mass of the electron but was

able to show that it was extremely small compared with a hydrogen atom.

Thus Dalton's 'indivisible atom' fell apart.

1.62 Since atoms are electrically neutral—common everyday materials

carry no resultant electrical charge—the discovery of the negatively

charged electron stimulated research to find a positively charged particle.

This was ultimately discovered in the form of the nucleus of the hydrogen

atom, with a mass some 1837 times greater than that of the electron but

with an equal but opposite positive charge. In 1920 the famous New Zea-

land born physicist Ernest Rutherford suggested it be called the proton.

So,

atoms were assumed to be composed of equal numbers of electrons

and protons, the electrons being arranged in 'shells' or 'orbits' around a

bunch of protons which constituted the nucleus of the atom. But there was

a snag: the true atomic weights of the elements, which had been derived

by careful independent experiment over many years, were much greater

than the atomic weights calculated from an assumption of the numbers of

protons and electrons present in the atom of a particular element. Chemists

explained this 'dead weight' in the atomic nucleus by suggesting that there

were extra protons in the nucleus which had been 'neutralised' electrically

by the presence of electrons also lurking there. Thus in the early 1930s

electrons were classed as being either 'planetary' or 'nuclear.'

1.63 At about this time the English physicist Sir James Chadwick dis-

covered the neutron, a particle of roughly the same mass as the proton but

carrying no electrical charge. Its presence in the atomic nucleus made it

easier to explain that part of the atomic mass not attributable to a simple

electron/proton balance. Its electrical neutrality made it a useful particle

in atomic research, since it could be fired into a nucleus without being

repelled by like electrical charges. Chadwick's discovery did in fact alter

the course of history since it made possible the development of the Atomic

Bomb ten years later (18.74).

1.64 Since Chadwick's time the number of elementary particles has

proliferated. These can be classified into three main groups:

1 Baryons (protons and other particles with a mass greater than that of

the proton).

2 Mesons (any of a group of particles with a rest mass between those of

the electron and proton, and with an integral 'spin').

3 Leptons (among which are the electron, positron or 'positive electron'

and the neutrino which possesses neither charge nor mass but only

'spin').

The term 'quark' is used to describe any one of a number of hypothetical

elementary particles with charges of % or -

1

A of the electron charge, and

thought to be fundamental units of all baryons and mesons. It is interesting

to note that the word 'quark' was devised by James Joyce in Finnegan's

Wake. Indeed, to date the existence of more than two hundred different

subatomic particles has been reported. Of these only three—electron, pro-

ton and neutron—appear to have any substantial influence on the distinc-

tive properties of each element. Consequently the rest will receive no

further mention in this book. The essential features of electron, proton

and neutron are summarised in Table 1.3. Since the real mass of these

particles is inconveniently small for calculations their masses relative to

that of the carbon atom (isotope C= 12) are generally used.

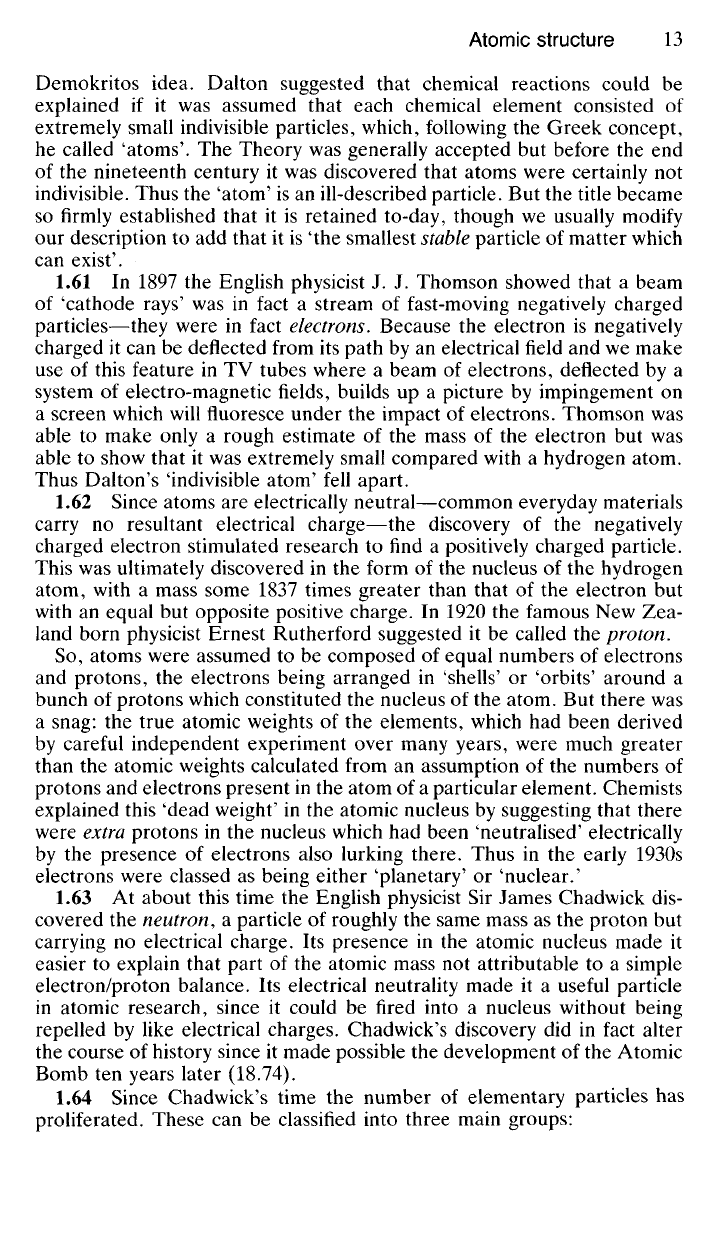

Table 1.3

Relative mass

Particle Actual rest mass (kg) (

12

C= 12) Charge (C)

Electron 9.11 x 10~

31

0.000 548 8 -1.602 x 10~

19

\ Equal but opposite

Proton 1.672 x 10"

27

1.007 263 +1.602 x 10"

19 f

Neutron 1.675 x 1O"

27

1.008 665 0 Zero

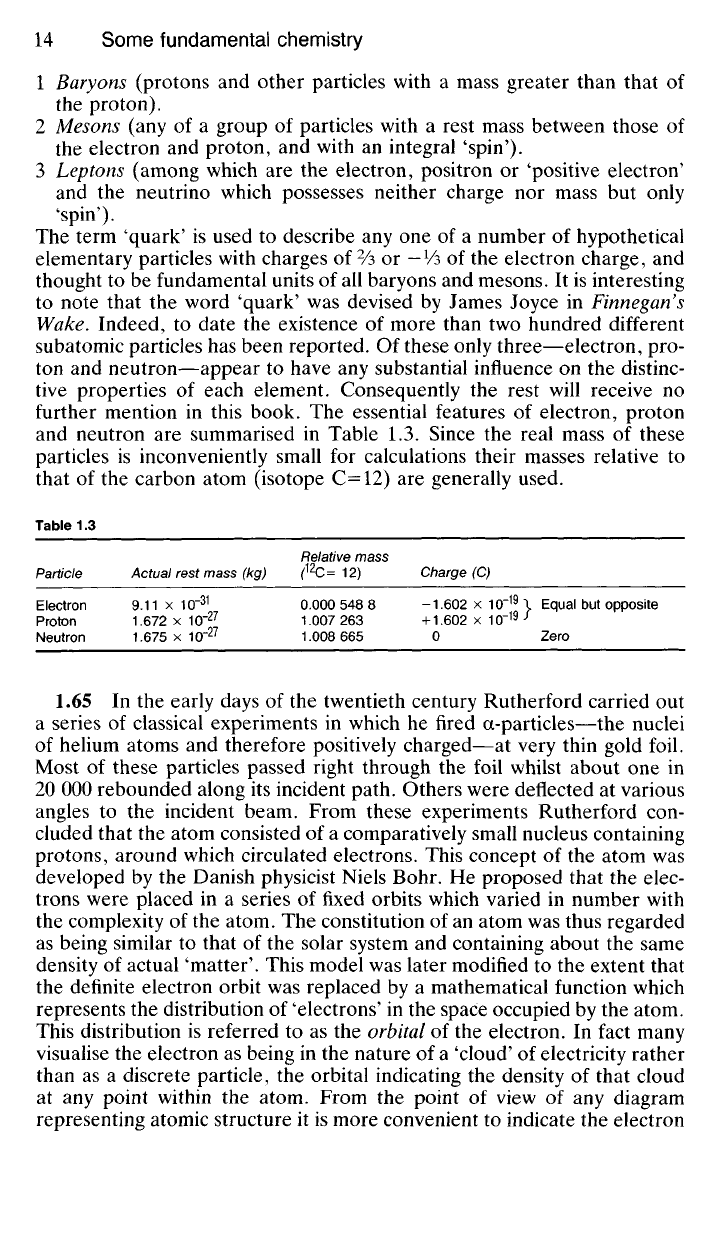

1.65 In the early days of the twentieth century Rutherford carried out

a series of classical experiments in which he fired a-particles—the nuclei

of helium atoms and therefore positively charged—at very thin gold foil.

Most of these particles passed right through the foil whilst about one in

20 000 rebounded along its incident path. Others were deflected at various

angles to the incident beam. From these experiments Rutherford con-

cluded that the atom consisted of a comparatively small nucleus containing

protons, around which circulated electrons. This concept of the atom was

developed by the Danish physicist Niels Bohr. He proposed that the elec-

trons were placed in a series of fixed orbits which varied in number with

the complexity of the atom. The constitution of an atom was thus regarded

as being similar to that of the solar system and containing about the same

density of actual 'matter'. This model was later modified to the extent that

the definite electron orbit was replaced by a mathematical function which

represents the distribution of 'electrons' in the space occupied by the atom.

This distribution is referred to as the orbital of the electron. In fact many

visualise the electron as being in the nature of a 'cloud' of electricity rather

than as a discrete particle, the orbital indicating the density of that cloud

at any point within the atom. From the point of view of any diagram

representing atomic structure it is more convenient to indicate the electron

as being a definite particle travelling in a simple circular orbit round a

nucleus consisting of protons and neutrons, but diagrams such as Fig. 1.1

should be studied with this statement in mind. Fig. 1.1 in no way represents

what atoms 'look like'.

1.66 The most simple of all atoms is that of ordinary hydrogen. It

consists of one proton with one electron in orbital around it. Since the

positive charge of the proton is balanced by the equal but negative charge

of the electron, the resultant atom will be electrically neutral. The mass of

the electron being very small compared with that of the proton, the mass

of the atom will be roughly that of the proton.

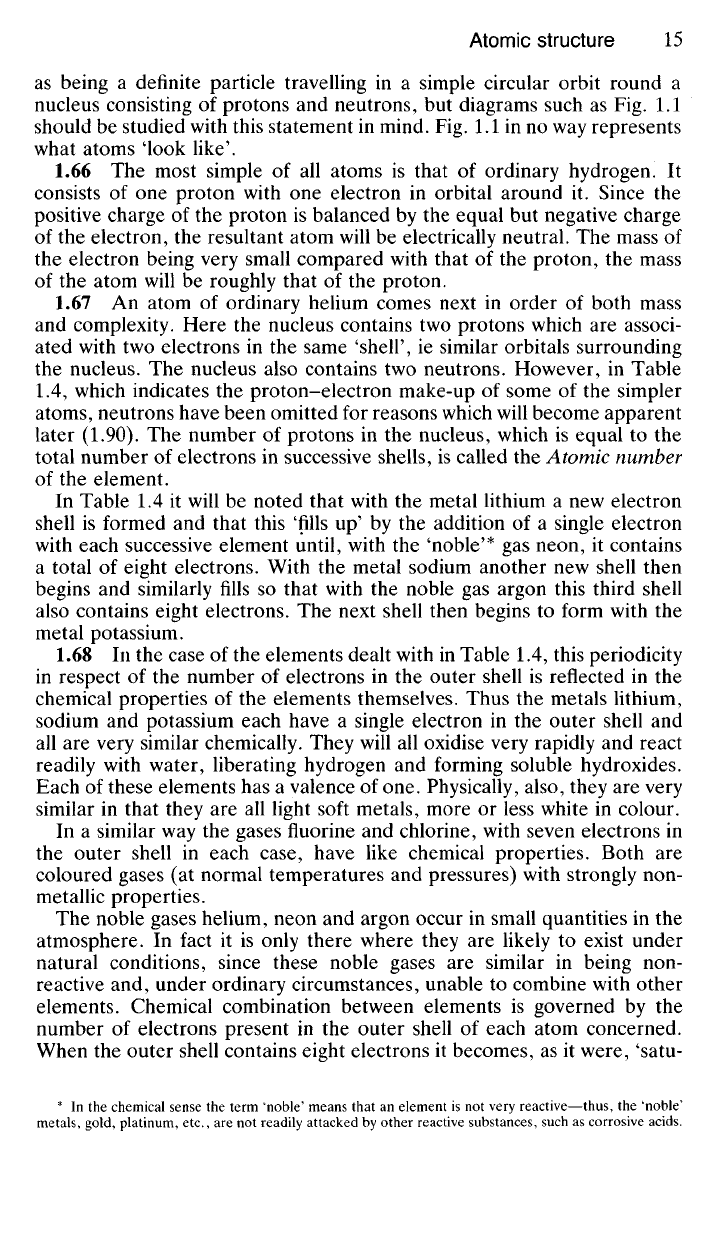

1.67 An atom of ordinary helium comes next in order of both mass

and complexity. Here the nucleus contains two protons which are associ-

ated with two electrons in the same 'shell', ie similar orbitals surrounding

the nucleus. The nucleus also contains two neutrons. However, in Table

1.4, which indicates the proton-electron make-up of some of the simpler

atoms, neutrons have been omitted for reasons which will become apparent

later (1.90). The number of protons in the nucleus, which is equal to the

total number of electrons in successive shells, is called the Atomic number

of the element.

In Table 1.4 it will be noted that with the metal lithium a new electron

shell is formed and that this 'fills up' by the addition of a single electron

with each successive element until, with the 'noble'* gas neon, it contains

a total of eight electrons. With the metal sodium another new shell then

begins and similarly fills so that with the noble gas argon this third shell

also contains eight electrons. The next shell then begins to form with the

metal potassium.

1.68 In the case of the elements dealt with in Table 1.4, this periodicity

in respect of the number of electrons in the outer shell is reflected in the

chemical properties of the elements themselves. Thus the metals lithium,

sodium and potassium each have a single electron in the outer shell and

all are very similar chemically. They will all oxidise very rapidly and react

readily with water, liberating hydrogen and forming soluble hydroxides.

Each of these elements has a valence of one. Physically, also, they are very

similar in that they are all light soft metals, more or less white in colour.

In a similar way the gases fluorine and chlorine, with seven electrons in

the outer shell in each case, have like chemical properties. Both are

coloured gases (at normal temperatures and pressures) with strongly non-

metallic properties.

The noble gases helium, neon and argon occur in small quantities in the

atmosphere. In fact it is only there where they are likely to exist under

natural conditions, since these noble gases are similar in being non-

reactive and, under ordinary circumstances, unable to combine with other

elements. Chemical combination between elements is governed by the

number of electrons present in the outer shell of each atom concerned.

When the outer shell contains eight electrons it becomes, as it were, 'satu-

* In the chemical sense the term 'noble' means that an element is not very reactive—thus, the 'noble'

metals, gold, platinum, etc., are not readily attacked by other reactive substances, such as corrosive acids.