Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

336

Chapter 17

Human occupance and the physical

environment

David Jones

Introduction

The term ‘physical environment’ has traditionally been taken to cover the physical conditions

and influences under which any individual or thing exists: air, water and land at the most

basic level, to which most authors would also add flora and fauna. In the British Isles, the

interrelationship between human societies and their physical surroundings has evolved in

complex ways through time, but never more fundamentally than in recent decades when the

term ‘environment’ has come into everyday usage and taken on new and varied meanings.

Traditional constructions of the physical environment as a vast stage for human activity,

providing both valued attributes (resources) and threats (natural hazards) in an ambivalent

way, have come to be replaced by new constructions that increasingly focus attention on

interdependence, change, threat, loss, uncertainty and concerns for the future. It is important,

therefore, to begin this review with a brief overview of these changes before going on to

examine some dimensions of the present interrelationships between human society and the

physical environment in the UK.

A historic overview

Human occupance of the United Kingdom land area has not been achieved without cost to

society. Early, pre-industrial populations were forced to overcome often severe constraints

imposed by difficult terrain conditions (steep slopes, windswept uplands, swampy floodprone

lowlands), dense forest, unpredictable weather, wild animals and disease (including malaria

which survived in Kent until 1918). Although it can be argued that the constraints imposed

by the physical environment on human activity have been relaxed over time, through the

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

337

application of science and technology, extreme events (natural hazards) continue to impose

costs on society in terms of death, injury and distress, but more significantly as economic

losses resulting from physical damage, loss of production and the general disruption to

‘normal life’. Indeed, it must be recognised that increased technological ability does not

necessarily make society less prone to hazard losses and in certain circumstances can result

in growing vulnerability and escalating loss potentials. This is best illustrated by society’s

ever-increasing dependence on electricity, where any events that result in widespread power-

failure, be they high winds (South East England in October 1987) or ice-storms (northern

Scotland, January 1998), cause massive disruption and huge costs.

But this has not been a one-way process. Ten thousand years of human occupancy

have resulted in profound alterations to the UK environment as have been widely detailed

in the literature. These changes were slow and modest at first but gathered in pace and

severity as the population grew, organisation improved and technology evolved.

Developments in agriculture, industrialisation, urbanisation and the evolution of transport

networks have all contributed, directly and indirectly, to modifications of landforms,

atmospheric composition and behaviour, water movements, vegetation cover and animal

populations, ranging in scale from the subtle to the extreme. Thus, the changes wrought in

the last few decades, conspicuous and dramatic though they may appear, must nevertheless

be viewed in their true perspective as merely representing the most recent phase in a long

history of alteration.

The best-documented human impacts have concerned the effects of increasing human

domination on the floral and faunal components of the ecosystem. This process of

transformation, sometimes referred to as the ‘diminution of nature’, is most obvious in the

widely developed urban environments or ‘townscapes’ where humans increasingly live,

work, travel and recreate in controlled artificial environments set within radically transformed

physical environments. Indeed, to a growing proportion of urban dwellers the concepts of

physical environment, natural environment and nature are increasingly associated with the

rural countryside. But it must be recognised that virtually none of the rural landscape can be

described as ‘natural’, except for limited areas of ‘wildscape’ surviving in the remoter

highlands and islands. The contemporary countryside is largely the product of culture and

bears the imprint of a wide range of human activities; the varied agricultural landscapes that

make up ‘farmscape’ have evolved through drainage of marsh, clearance of forests and the

variable impact of the Enclosure Act. Change continues today, most particularly in the

expansion of housing, industry and commercial activity and the removal of copses, hedges

(until recently destroyed at a rate of 6,400 km per year: see Chapter 20) and heathland to

provide larger, more efficient cultivation units. The ecology has changed as habitats have

been altered. Species diversification carried out through the purposeful introduction of exotic

trees, shrubs, plants, birds and animals (e.g. rabbits in the twelfth century), accidental releases

(coypu, mink, parakeets, wild boar) and through the development of domesticated strains

has, in part, been counteracted over the last few decades by the spread of expansive

monoculture, pollution and the widespread application of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

Although some species have adapted well to these ecosystem changes and prospered (e.g.

the seagull, house sparrow, starling, pigeon, collared dove, rabbit, fox, nettle) or have been

actively encouraged (e.g. conifers in plantations), others have suffered serious decline or

extinction (various raptors, Dartford warbler, smoothsnake, otter and numerous plants,

butterflies and moths). Such examples of indigenous species decline, which are frequently

DAVID JONES

338

highlighted in calls for nature conservation measures and controlled reintroductions (e.g.

capercaille, red kite) to maintain biodiversity (see Chapter 20), thus merely represent some

of the more obvious repercussions of human interaction with the environment.

Anthropogenic environmental change similarly affects all aspects of the abiotic physical

environment: land, air and water. In fact, changes to any one usually result in response in the

other systems. For example, the progressive changes in land use from original forest to the

contemporary agricultural and urban environments have resulted in significant changes in

surface conditions (roughness, water balance, thermal character) and thereby altered the micro-

climate and run-off (drainage) characteristics, the most significant responses being increases

in soil erosion, water pollution (suspended solids), river sedimentation and flooding. Evidence

for anthropogenic induced soil erosion associated with early forest clearance, a process that

would have been assisted by the arrival of the plough in circa 5000 BP, exists in the widespread

occurrence of shallow, immature or truncated soils in upland areas, in the fact that most lowland

floodplains are underlain by thick sequences of fine-grained alluvium laid-down during the

last 9,000 years, and in the sedimentary sequences preserved in lakes which often reveal rapid

increases in deposition at various times between 5,000 and 1,000 years ago.

Similarly, surface changes have collectively altered the thermal, hydrological and

dynamic properties of the overlying air, and the addition of pollutants considerably changed

its composition. The most obvious repercussion of these changes was that growing towns

and cities created distinctive ‘urban climates’ with their characteristic ‘heat islands’, ‘dust

domes’, and generally poor visibility conditions with frequent smoky fogs or smogs. Such

features are of considerable antiquity (the term ‘smog’, i.e. smoke and fog, was coined in

London in 1905). London is known to have grown large enough to modify the local climate

by the mid-thirteenth century, largely due to use of sea-coal, first in forges and then in lime

kilns. John Evelyn remarked in 1661: ‘The weary traveller, at many miles distance, sooner

smells than sees the city to which he repairs’, an observation later supported by Gilbert

White who noted the ‘dingy smoky’ appearance of the air in dry weather as far downwind

as Selborne, Hampshire. The characters in the novels of Charles Dickens were frequently

depicted groping around in the dense yellow fogs—or ‘London particulars’ as they were

known—that plagued the capital, and Byron referred to a ‘huge dun cupola’ over the city.

In fact Victorian London came to be affectionately known as ‘The Smoke’. The Industrial

Revolution led to particularly marked alterations, with widespread and intense air pollution

in the industrialised coalfield areas, such as the Black Country, the Potteries and South

Yorkshire. What has changed during the twentieth century is that the urban areas have

expanded dramatically and altered markedly in form, while at the same time pollution

emissions have changed in composition (see Chapter 18) with a decline in the traditional

constituents (smoke and SO

2

) and their replacement by motor vehicle exhaust gases.

Although the Clean Air Acts of 1956 and 1968 are often given the credit for the

dramatically improved cleanliness of urban atmospheres and the associated improvements

in visibility and recorded sunshine which, together with building cleaning programmes,

urban renewal and pedestrianisation, have helped to make inner-city environments much

more pleasant, in reality it was socio-economic and cultural changes post-1945 that were

the dominant influences: the adoption of central heating, the growth in dependence on

electricity (otherwise known as ‘the electrification of society’), changes in the pattern of

electricity generation, nuclear energy, the increased use of oil, the exploitation of North Sea

gas, the modernisation and contraction of the railways and the progressive collapse of the

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

339

heavy engineering industry. It was these factors that combined progressively to reduce the

demand for coal (see Chapters 3 and 18, and p. 370 in this chapter), while at the same time

causing an increasing proportion of coal burning to take place in large, efficient, high-

temperature furnaces producing limited amounts of smoke which are discharged through

high chimneys (tall stacks) and dispersed by the wind. As a consequence, the traditional

cold weather, unhealthy smoke-fogs (12,000 Londoners are thought to have died prematurely

due to the famous ‘Great Smog’ of 5–9 December 1952, 4,000 during the smog and 8,000

subsequently) that plagued cities during winter months, and occasionally became persistent

and disruptive (i.e. the London smogs of 1873, 1880, 1882, 1891, 1892, 1905, 1948, 1952,

1956 and 1962) have been eradicated, only to be replaced by a new, summer, day-time,

photochemical version first recorded in 1975, which is produced by the conversion of motor

exhaust gases into a range of substances including PAN and ozone (see Chapter 18). Thus,

human activities have continued to modify the atmosphere with the result that urban climates,

in particular, continue to evolve.

While such indirect or accidental changes may be of great significance, the impact of

direct or purposeful changes to the earth’s surface is visually much more impressive. Human-

made landforms of widely differing form and antiquity are ubiquitous. Created for an

enormous variety of purposes, erosional forms range from the innumerable small pits that

pock the landscape (37,000 were once recorded in Norfolk alone) produced through the

removal of a few cubic metres of material and now often preserved as small ponds and

copses, to enormous ‘long-life’ extraction sites where removal is measured in tens of millions

of tonnes (see Chapter 4). Particularly impressive are the Norfolk Broads, a collection of

twenty-five freshwater lakes created by the removal of 25.5 million cubic metres of material

in peat diggings prior to AD 1300. Ancient depositional features range from the thousands

of small prehistoric burial mounds (tumuli) and earthworks, to Silbury Hill, Wiltshire, at 40

metres the tallest prehistoric mound in Europe. Equally impressive are the ridge and furrow

landscapes of the English Midlands which are thought to represent the survival of the medieval

strip-field pattern. A survey of North Buckinghamshire in the late 1950s revealed that this

patterning still covered 343 square kilometres or 28 per cent of the surface, each square

kilometre of disturbance representing the movement of 62,000 cubic metres of earth.

However, such legacies of past sculpturing pale into insignificance when compared with

the products of the Industrial Revolution. The expansion of the railway network in the mid-

and late nineteenth century led to prodigious anthropogeomorphic activity, including the

creation of earthworks of such magnitude that Ruskin was moved to speak of ‘your railway

mounds, vaster than the walls of Babylon’. Even these were to be eclipsed in scale by the

thousands of colliery spoil heaps that grew to dominate the surface of the coalfields. Spoil

production expanded dramatically from the middle nineteenth century as deeper and thinner

coal seams were exploited and mechanical extraction techniques developed, and the

employment of mechanical tipping led to the creation of hundreds of huge conical heaps,

many more than 50 metres high, that characterised coalfield landscapes until remodelled in

the 1970s and 1980s. Now only the gleaming white sand mounds of the china clay industry

—the so-called ‘White Alps of Cornwall’ —survive as significant examples of a once

widespread landform, the towering conical spoil heap (see Chapter 4).

Human impact has not been confined to sculpturing the existing land surface. Coastal

marshes and fens, as well as the lower reaches of most river valleys, were progressively

reclaimed from the sea by the construction of dykes and levees, so that hundreds of square

DAVID JONES

340

kilometres of land could be brought under cultivation. The Somerset Levels and Romney

Marsh are just two examples of a widespread phenomenon which began 800 years ago and

reached its most dramatic scale in the Fens, where 153 square kilometres had been reclaimed

by 1241 and a further 500 added since 1640. Further modifications were achieved through

the excavation of harbour basins and the dredging of channels, much of the material being

used locally to extend the land area.

It is against this background of long-term and extensive environmental modification

that the significance of recent and contemporary changes have to be assessed. Population

growth, technological development and the changing patterns of urbanisation and economic

activity have ensured that human occupance continues to exert evermore varied modifying

influences on the physical environment, as has often been catalogued by geographers.

But one important recent difference has been the growing appreciation of the magnitude

of changes, which has arisen from increased interest in, and monitoring of, the physical

environment. This has stemmed from the dramatic expansion in environmental awareness

which has its roots in the 1930s, although the popular movement has only really flourished

since the late 1960s. The intensity, complexity and spatial extent of human impacts are

now known to have progressively increased with time, as is well illustrated by the example

of atmosphere pollution which has changed from local (e.g. smoke) via the transnational

to the regional scale (e.g. acidification), then to the sub-hemispherical level (e.g.

stratospheric ozone depletion) and finally to the global scale (e.g. global warming). This

knowledge has, in turn, fuelled concerns that the unchecked continuation of processes of

transformation could result in unforeseen consequences severely detrimental to humankind,

possibly even catastrophic as portrayed in popularist doomsday scenarios, thereby resulting

in growing calls for controls on environmental change, the maintenance of biodiversity

and the adoption of sustainable development. Suddenly the interrelationship between

human society and the physical environment in Britain is no longer a parochial matter of

academic interest only but has become a small element of global debates on the future of

the ecosphere as testified by the Rio Earth Summit (1992) and the Kyoto Conference on

Climate Change (1997).

The recognition of global environmental change has resulted in other re-evaluations

of the interrelationship between human societies and the physical environment, most

especially in the perceived ability of the physical environment to act as a benign framework

for human activity and a limitless depository of waste. The progressive change in relationship

stimulated by the Industrial Revolution has been referred to as ‘The Great Climacteric’ and

has seen traditional, relatively simple, local environmental problems replaced by new,

‘complex’, multi-faceted, spatially extensive, ‘first order’ problems (e.g. global warming)

which are sometimes referred to as ‘problematics’, ‘concatenations’ or ‘syndromes’. This

change from easily identifiable localised hazards to complex, uncertain international problems

has also been termed the ‘risk transition’ and features a new class of hazards: diffuse,

cumulative, slowly developing and insidious processes and changes with enormous potential

for harm, known as ‘elusive hazards’.

As the growing scale of human alteration to the physical environment has become

recognised, so have the terms ‘natural environment’ and ‘nature’ come to be progressively replaced

by ‘environment’. While ‘nature’ was seen to be natural (i.e. non-artificial), reliable and ambivalent,

the word ‘environment’ has increasingly come to mean human-modified, questionable and

potentially problematic. The evolution of social constructions of the physical environment has

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

341

resulted in the present situation where environment is increasingly seen to be risk-laden, containing

unseen or invisible or elusive threats that can only be identified, determined and delimited by

scientists. At the close of the millennium, therefore, the physical environment has achieved a

greater than ever importance, in stark contrast to many predictions earlier in the century that

envisaged human activities as becoming progressively divorced from the physical surroundings

as technological ability came to dominate over the natural realm.

Many of the issues raised in this introductory overview are considered at greater

length elsewhere in this book, so the remainder of this chapter will concentrate on human-

induced alterations to the physical environment and the growing importance of environmental

hazards, commencing with the latter.

Environmental hazards and risk

Hazard is an attribute that is definable as the propensity to cause harm, loss or adverse

consequences. It is a human construct attributable to objects, substances, activities, processes

or circumstances that result in harms, losses or costs to humans and what they value. Hazards

are, therefore, defined by humans and not nature. They are cultural constructions and as

human societies evolve and knowledge increases so too do the criteria for determining

hazard and the range of phenomena that receive the label. As a consequence, hazard must

be envisaged as a dynamic concept, in many regards similar to the concept of resource:

indeed, Zimmerman’s famous statement about resources can be adapted to hazard to yield

‘hazards are not, they become’.

Traditionally, three broad groups of hazard have been recognised, ‘social’,

‘technological’ and ‘natural’, with much of the geographical literature focusing on the so-

called ‘natural hazards’ which can be defined as ‘those naturally occurring elements of the

physical environment harmful to humans, human activity and the things that humans value’.

Two broad categories are normally distinguished, geophysical and biological, which are

capable of considerable further subdivision (e.g. atmospheric, geomorphological, floral,

faunal, etc.). Attention on ‘natural hazards’ has been reinforced during the 1990s due to the

United Nations proclaimed International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR),

which has sought to reduce the costs to global society arising from geophysical events (the

so-called ‘natural tax’) by the international pooling of knowledge and expertise on how to

mitigate adverse impacts.

However, the validity of the fundamental threefold division of hazards has also come to

be questioned as research has shown that many hazard events are surprisingly complex in the

sense that they involve combinations of ‘social’, ‘technological’ and ‘natural’ elements. The

basic ‘four phase’ model of hazard—Incubation-Trigger-Primary Hazard-Consequences—

reveals that while the trigger event and primary hazard may be easily categorised into one of

the three main groups (although not necessarily the same group), the incubation process and

the resulting consequences (impacts, further hazards, benefits) often involve complex

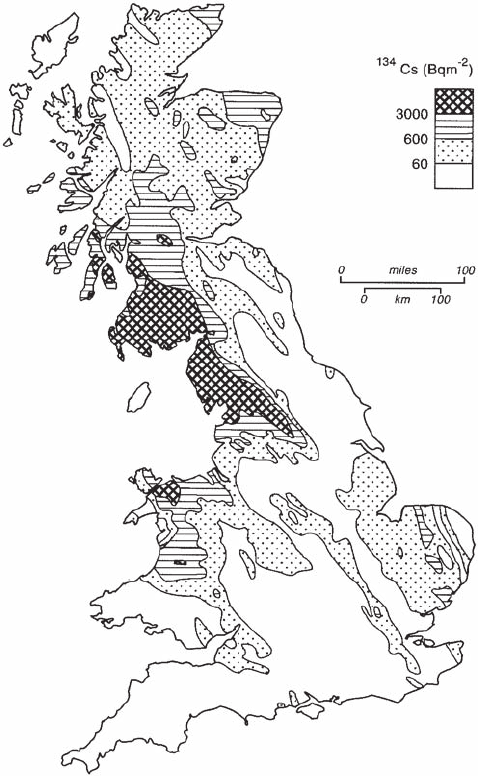

combinations. This is well illustrated by the nuclear fall-out from the Chernobyl nuclear accident

(28 April 1986) which was the result of technological failure due to poor operating practices

(social), with the adverse impacts on the sheep-rearing industry in Britain arising because the

radioactive material had been transported by the wind and deposited by rain so as to produce

a spatially variable pattern of contamination (Figure 17.1). How to classify this event is clearly

problematic and the question has to be asked as to whether the end results would have been

DAVID JONES

342

significantly different had the same magnitude of nuclear accident been achieved by a

terrorist’s bomb, poor maintenance, a design fault, corrosion or an earthquake? The answer

is ‘no’, revealing that different triggers can result in similar primary hazards and adverse

consequences (convergence), thereby indicating that while the classification of hazards on

the basis of the trigger event may be crucial to hazard management, it is of less importance

in risk management (see pp. 343–50).

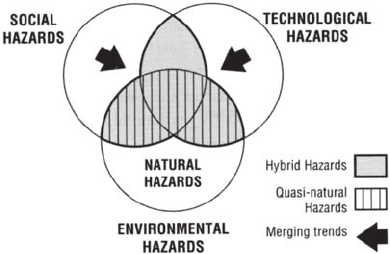

The blurring of the distinctiveness between the three fundamental groups of hazard

has for long been recognised. Human modification of the physical environment has produced

changes in the magnitude, frequency and spatial extent of certain groups of extreme events

(floods, landslides, avalanches, etc.) resulting in the identification of quasi-natural hazards

FIGURE 17.1 Generalised map of fall-out of Chernobyl-derived

134

Cs over Great Britain, April-May

1986

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

343

where naturally occurring phenomena

have been triggered or in other ways

exacerbated by human activity.

Pollution episodes involving naturally

occurring substances are in the same

category: for example, all rainfall is

slightly acid and ‘acid rain’ is merely

where the acidity of rainfall has been

increased as a consequence of human

activity. Where more exotic chemicals

are introduced into the environment due

to war, terrorism, accident,

technological processes, waste disposal

or as chemically synthesised pesticides,

the resulting hazards clearly have social, technological and even natural triggers (e.g. the

presence of concentrations of toxic chemicals due to carelessness, accident or landslide,

flood, etc.), revealing a more complex interrelationship between the three groups. As a

consequence, an increasing proportion of hazards are now interpreted as hybrid in origin

(Figure 17.2), including those traditionally called quasi-natural hazards. Further, the term

‘natural hazard’ has become disputed as more and more geophysical phenomena are seen

to reflect the increasingly profound influence of human activities on physical environmental

systems, and has come to be replaced by ‘environmental hazards’ which can be defined as

‘the threat potential posed to humans and what they value by events and circumstances

originating in, or transmitted by, the physical environment, including the built environment’.

Environmental hazards, therefore, represent a very broad collection of phenomena, including

truly ‘natural hazards’ (earthquakes, tornadoes, radon), ‘quasi-natural hazards’ (landslides,

floods, acidification, erosion) and a wide variety of hybrid hazards operating within the

physical environment such as pesticides, atmospheric pollution, photochemical smogs,

radioactive fall-out, oil-spills and other forms of water pollution, contaminated land, pests

and disease.

Clearly, the multiplicity and diversity of environmental hazards render detailed

consideration of their growing significance in Britain beyond the scope of a single chapter,

so this contribution will concentrate on the ‘natural’ and ‘quasi-natural’ groupings of

geophysical hazards, otherwise known as geohazards, with other aspects addressed in

Chapters 18, 19 and 20. However, before embarking on this review it is necessary to briefly

consider the topic of environmental risk, a subject that has rapidly gained in prominence

over the past decade.

Risk has emerged as one of the most widely used and fashionable concepts of the

1990s, so it is not surprising that the terms ‘hazard’ and ‘risk’ are frequently confused in the

literature. Both are cultural constructions, but whereas hazard is concerned with the actual

and potential causes of loss or harm, risk is concerned with measuring exposure to the

chance of loss or, to put it another way, the likelihood of differing levels of loss resulting

from hazards. Exposure is often, incorrectly, assumed to be simply a function of the

magnitude-frequency characteristics of hazard (i.e. event probability) but, in reality, it is

mainly determined by vulnerability (V

u

), or the propensity of individuals, groups, objects,

systems and organisations to suffer harm, loss or detriment. Vulnerability is therefore the

FIGURE 17.2 The hazard spectrum

Source: After Jones et al. (1993a).

DAVID JONES

344

fundamental link between hazard and risk. It is a complicated concept that focuses on the

value humans place on objects, activities, surroundings and even life, and the proportion of

total value (V) potentially adversely affected by a hazard of specified magnitude (H

s

). Thus

total risk (R) for any context (individual, group, community, organisation, society, area) can

be envisaged as the sum total of all specific risks (R

s

), each of which may be expressed as

R

s

=H

s

*V*V

u

where H

s

is the probability of specified hazard of particular magnitude, or

greater, occurring in a given period of time.

Risk is ubiquitous, for no human activity is risk-free. It is also a complex and abstract

concept, for risk exists for events which have yet to happen or may never happen (e.g. a

meteor impact destroying London), and for hazards that may never exist (e.g. a genetically

engineered organism capable of extinguishing human society). As a consequence, there

are many and varied interpretations of risk, and radically differing perspectives as to its

nature and component parts. Of greatest relevance to this discussion is environmental

risk which is, simply stated, the risk arising from environmental hazards and can be defined

as ‘an amalgam of the probability and scale of exposure to loss arising from hazards

originating in, or transmitted by, the physical or built environment’. Clearly the accurate

establishment of environmental risk for any context is an exceedingly long and complex

process beset with four fundamental problems: lack of information on hazards, scientific

uncertainties, the inability to foresee all possible outcomes, and the difficulty in placing

agreed values on many outcomes. Thus it must be recognised that current pressures to

increase the production of Environmental Risk Assessments (ERAs) for hazardous

operations (e.g. chemical plants) and as an addition to the Environmental Impact

Assessment (EIA) process, are not seeking complete appraisals but merely partial

assessments relating to the probabilities of specific outcomes (e.g. the annual probability

of death from a radiation leak in a specific nuclear power station) as determined by a

process known as Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA). However, the process of

calculating environmental risks is still in its relative infancy and great advances can be

anticipated in the early decades of the new millennium.

The significance of geohazards

The United Kingdom is not an area considered prone to geohazard impacts. There are no

active volcanoes, significant earthquakes are infrequent (the last major one was the Colchester

earthquake of 1884) and small by global standards, tsunami are even rarer, true hurricanes

have yet to reach these islands despite the rhetoric generated by the October 1987 storm,

and there has been no major meteorite impact in historic times. Thus few examples exist of

dramatic, rapid onset, high energy, catastrophic events, thereby leading to notions that the

physical environment is passive and of little relevance to the nation’s economic performance.

Indeed, risk assessments indicate that loss of life/injury is very much more likely to occur

through industrial, transportational or domestic activity than due to so-called ‘natural’ events.

Nevertheless, and despite technological development, geohazards continue to cause

significant and mounting costs to society through destruction, damage, delay and loss of

production. The vast majority of cost-inducing events are either directly or indirectly due to

extremes of the weather: high winds, dense fogs, intense cold, blizzards, drought, landslides

and river and coastal flooding. Often the effects are extensive rather than intensive, with the

costs of impact absorbed by large numbers of individuals and organisations, but most

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

345

especially electricity supply organisations, local authorities and the ‘natural perils’ sector

of the insurance industry.

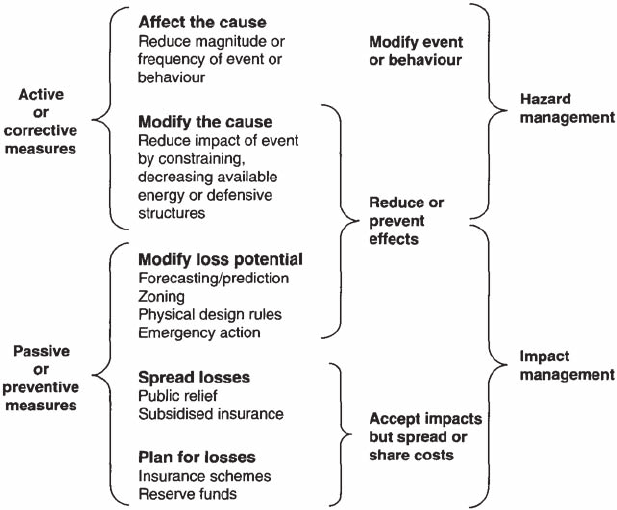

The repeated occurrence of geohazard impacts has resulted in management decisions

ranging from no-action (loss-bearing) due to poor perception of risk, financial constraints

or lack of technical knowledge, through a wide variety of adjustments which seek to limit

the impact of similar events in the future. Such adjustments can be broadly subdivided into

two groups: structural (engineering) solutions which seek to constrain/control the hazard or

to protect the threatened population and infrastructure (dams, levees, flood walls, building

codes, etc.), and non-structural (planning) solutions which seek to reduce hazard impact

potential by means of spatial, temporal or financial adjustments (land-use zonation,

forecasting, warning systems, insurance, disaster relief, etc.) (Figure 17.3). Alternatively, a

distinction may be drawn between attempts to constrain or control hazard (hazard

management), and measures focused on protecting society (vulnerability management),

with both contributing to risk management. Irrespective of terminology, it must be recognised

that the costs of geohazards are not restricted to the actual losses attributable to hazard

impacts but must also include the costs incurred in determining threats, making adjustments

and providing protection.

Chosen responses to geohazards are variable, with choice of adjustments (Figure

17.3) largely dependent on perceptions of risk, itself a complex function of hazard (size and

character), frequency of occurrence and scale of expected losses. Studies have shown that

risk assessments by individuals and groups result in risks being sub-divided into two broad

groups, ‘acceptable’ or ‘tolerable’ risks (road accidents, lung cancer from cigarettes, etc.)

FIGURE 17.3 Adjustment choices