Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

JOE PAINTER

306

The contemporary geography of elected local government

Changing territorial structures

The straightforward two-tier structure of local government established in the 1974

reorganisation lasted until the mid-1980s. In 1986, as part of its attempts to control the

power of radical left-wing local councils, the Thatcher government took the dramatic step

of abolishing the Greater London Council, then led by the populist Labour left-winger, Ken

Livingstone, and the six metropolitan county councils of West Midlands, Merseyside, Greater

Manchester, Tyne and Wear, South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire. This move left London

and the other major English conurbations with only a single tier of elected local government.

In many cases, and particularly in London, the lack of a strategic local authority to provide

city-wide services and consider planning issues over a wide area has been keenly felt. In

many cases the metropolitan district councils are simply too small to provide cost-effective

services such as police and fire. In these cases a confusing pattern of ‘joint boards’ has been

set up. Joint boards are not directly elected but are made up of representatives of the various

district councils in the area covered by the board. Different boards are responsible for different

services such as fire, transport and so on.

Although the imposition of single-tier local government in the big cities has been

widely criticised, there are also problems with the two-tier system with its potential for

waste and duplication. In the early 1990s many commentators from across the political

spectrum were arguing that a universal single-tier system of all-purpose local authorities

(so-called ‘unitary’ authorities) should be introduced. The idea of unitary authorities was

supported particularly by the Conservative government of John Major, and in 1992 the

government began reviewing the structure of local government with a view to moving to a

unitary system. In England, a Local Government Commission was established under the

chairmanship of Sir John Banham. In Scotland and Wales reviews were conducted by the

government itself. Northern Ireland already had a single tier of elected councils.

The Banham Commission was instructed to undertake a review of the structure,

boundaries and electoral arrangements for local government with two criteria in mind: that

local councils should reflect local identities and community interests and that local

government should be ‘effective and convenient’. The initial assumption was that unitary

authorities would be established virtually everywhere, and as Wilson and Game note, the

Commission’s early reports

advocate forcefully the advantages of unitary authorities: their ability to develop a

co-ordinated approach to service delivery; their claimed enhancement of local

accountability; their improved efficiency and effectiveness.

(Wilson and Game 1994:303)

In the event the process of reorganisation turned out to be a much more piecemeal

affair than the vision of a universal single-tier system suggested. The Commission worked

through a process of local consultation (including opinion polling to discover the degree of

public identification with existing and possible alternative units of local government). In

most areas, the Commission recommended that the present two-tier system should be retained,

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GOVERNANCE

307

but it did recommend the creation of forty-six new unitary authorities, mainly in larger

towns and medium-sized cities such as Darlington, York and Bristol. All the new unitary

authorities in England were in operation by April 1998.

In Scotland and Wales, where the process of reorganisation was undertaken by the

government directly, the two-tier system was replaced by a universal system of unitary

authorities in April 1996. In Scotland twenty-nine unitary councils have been established to

replace the fifty-three districts and nine regional authorities. In Wales twenty-two new unitary

councils replaced the eight counties and thirty-seven districts.

The result of the reorganisation process has been to produce a much more complex

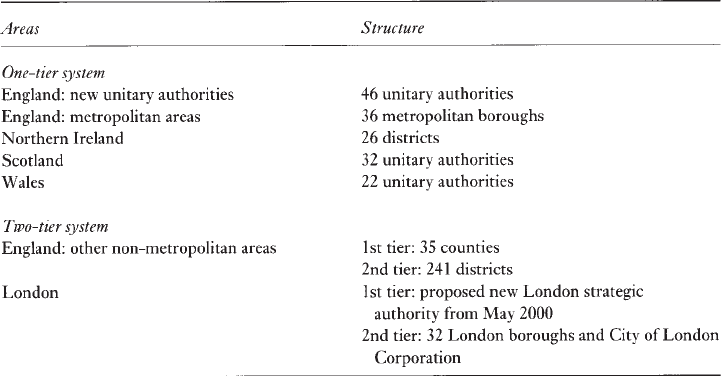

geography of local government structure in the UK. This is summarised in Table 15.3. A

major difficulty with the whole process of reorganisation is identified by Wilson and Game:

The establishment of the Local Government Commission has preceded meaningful

debate about the role, constitutional position and function of local government in a

democratic society. It has been compared to putting up a building without first

determining its use.

(Wilson and Game 1994:300)

The Labour government has recently brought forward new proposals for reviving the

role of local government and is also introducing some further structural changes, notably

the proposed new strategic authority for London, with a directly elected mayor.

Electoral geography

All the discussion and debate about structure, function and finance can obscure the fact that

local government also involves electoral and party politics. Although the political power of

local authorities has been significantly circumscribed since the late 1970s, local elections

TABLE 15.3 The structure of UK elected local government, 1998

JOE PAINTER

308

still provide a degree of democratic accountability for the activities of local authorities and

democratic control over the distribution of resources between different local services.

Moreover, the present Labour government is proposing a range of reforms to the operation

of local government with the aim of reviving local democracy, improving consultation and

participation and bringing local government closer to local people (Department of

Environment, Transport and the Regions 1998).

Local councils are made up of councillors who are elected to represent small

geographical areas (known as wards) for four years at a time. In most areas of the country

the major political parties play a central role in local politics. In some places (mainly remote

rural areas) many councillors serve without formal political affiliations as independents. In

all there are some 25,000 local councillors in the country each representing an average

electorate of 2,200 voters. District councils in England typically have around 35–60

councillors. County councils and metropolitan boroughs are somewhat larger with around

55–100 councillors. Where one political party gains a majority of seats on the council it is

able to control the council and ignore, if it wishes, the views of the minority councillors. In

many councils, however, no party is in a majority and the council is said to have ‘no overall

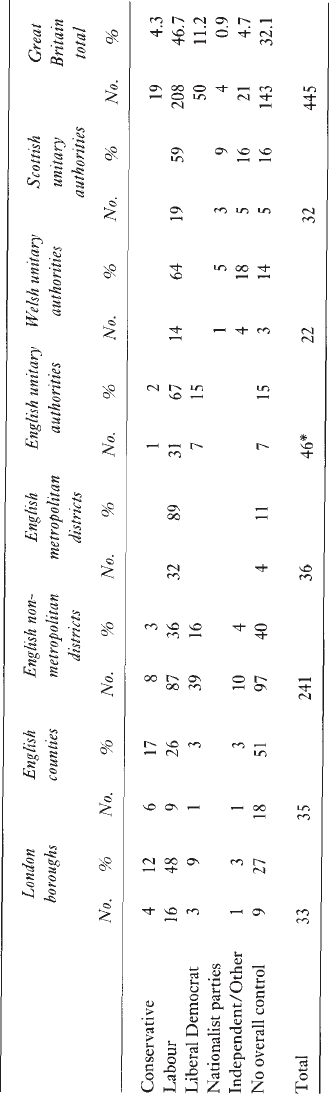

control’. Table15.4 illustrates something of the geography of local government electoral

politics. It shows that in 1997 the Labour Party was the dominant party of local government

controlling 46.7 per cent of all councils in Great Britain. The Liberal Democrats are in

second place with 11.2 per cent of councils and the Conservatives a poor third with just 4.3

per cent. This picture reveals the extent to which the Conservative Party has been eradicated

from swathes of local government in the UK, even in its traditional heartlands, the English

shire counties. Only six of the thirty-five English counties were controlled by the

Conservatives in 1997. Labour is particularly dominant in the cities, shown by its high

levels of control in the English metropolitan districts and the English unitary authorities.

The regional picture adds another dimension. Labour dominates much of local government

in Wales and Scotland, but in the more remote parts independents have strong support. In

addition the nationalist parties, Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party, between them

control four councils. The Liberal Democrats have pockets of electoral strength, especially

in south-west England. In Northern Ireland the structure of local government and the use of

a system of proportional representation ensures that no single party dominates, with most

councils having no overall control.

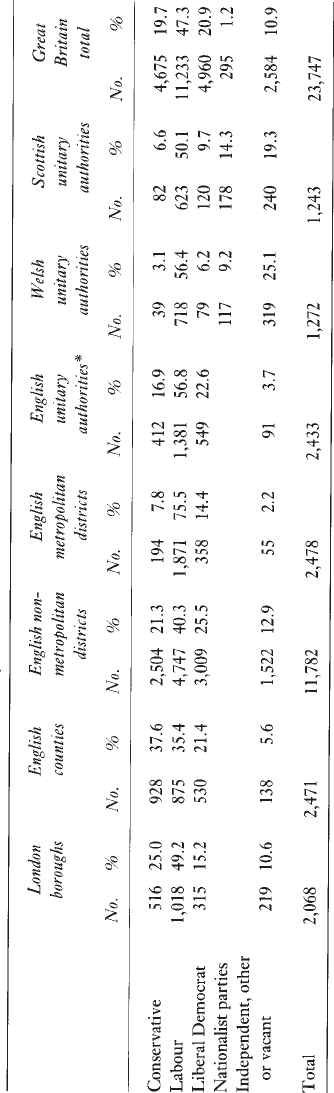

Although the geography of council control is clearly important, the British ‘first past

the post’ electoral system tends to exaggerate the popular appeal of the biggest party (in this

case Labour). A complementary way of examining the electoral strength of the different

parties in different types of council is to look at the numbers of councillors elected for each

(Table 15.5). Table 15.5 confirms the dominance of the Labour Party in local government

nationally. Only in the English counties does another party (the Conservative Party) have

more councillors than Labour. However, there is also a clear geography to party strength,

with Labour being strongest of all in the metropolitan districts (large cities) where it has

three-quarters of all seats. The Liberal Democrats are strongest in rural areas and mediumsized

towns (non-metropolitan districts and English unitary authorities). Table 15.5 also confirms

the importance of Independent councillors in the remoter parts of Wales and Scotland. The

weakness of the Conservative Party is also evident; its present position compares very

unfavourably with its historical position as a strong party of local government in both rural

and urban areas.

TABLE 15.4 Political control of British local government, May 1997

Source: Municipal Yearbook.

Notes: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of founding. ‘No overall control’ means that no party held a majority of seats. It

includes councils where one party had exactly half the seats and governed with effective control using the casting vote of the chair,

as well as councils where minority Conservative groups govern with support from Independents. In Northern Ireland two councils

were controlled by the Ulster Unionist Party, one by the Social Democratic and Labour Party and one by Sinn Fein. The remaining

twenty-two councils had no overall control.

*Figure includes nineteen district councils that did not become unitary authorities until April 1998.

Source: Municipal Yearbook.

Notes: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

*Category includes nineteen district councils that did not become unitary authorities until April 1998.

TABLE 15.5 Party strength by number of councillors, May 1997

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GOVERNANCE

311

Central-local relations

The electoral geography of local government affects the geography of local government

service provision. Different local authorities do provide somewhat different levels

and mixtures of services to local people and these differences reflect in part the political

differences between councils. This seems obvious, since local elections are traditionally

fought on issues of the balance between local taxation and local service provision

and the mix of services to be provided. However, there are other factors at work too.

As Duncan and Goodwin showed in 1988, variations in levels of service provision

are not perfectly correlated with political control. In fact, their research suggested

that the geography of local government activity has more to do with the pattern of

uneven social and economic development in the country than with the party-political

affiliations of local councils. In addition, the thrust of central government policy over

the past twenty years has been to work to even-out such local variations. For example,

central government grants to local councils are calculated using a complicated formula

known as the ‘Standard Spending Assessment’ (SSA). The SSA for each local authority

is calculated as that amount of local expenditure required to provide a standard package

of service to the local population, taking into account demographic and socio-economic

differences between local areas. If councils wanted (for political reasons) to provide

a more generous, or less generous, level of services they would have to raise the

money from local taxation. However, central government has also limited the ability

of local authorities to increase local taxes. This has made it very difficult in practice

for local councils to deviate very significantly from a national pattern of service

provision. Nevertheless, council services and tax rates do vary from place to place—

partly because the Standard Spending Assessment system is far from perfect as a way

of assessing local needs, partly because councils vary in the efficiency with which

they use the resources at their disposal and partly because even within the tight controls

imposed by central government there is still some scope for local discretion in the way

resources are deployed.

The relationship between central and local government, of which the financial system

is one aspect, can be thought of as another key element in the changing geography of

local government. In many countries, local government has much more freedom and

autonomy from central control. In some cases this is guaranteed constitutionally, in others

it is a matter of custom and practice. The United Kingdom is a unitary state, in which

local government is constitutionally subordinate to central government, but it has also

become a highly centralised state in which most of the activities of local government are

closely regulated by the centre. This trend began during the 1970s, but was accelerated

dramatically by the Conservative governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major.

The present Labour government has put forward proposals which will modify this

centralisation to some extent, but there is still a considerable emphasis on national standards

of service provision, quality control, systems of consultation and mechanisms of

governance. Even if the new proposals are implemented in full, the UK will still not have

anything approaching local self-government. Thus local government is both an arena of

political conflict, debate and competition, but also the object of national political debate

and action.

JOE PAINTER

312

Non-elected local government

One of the most important aspect of central-local relations in the UK is the growth of non-

elected local government, mainly as a result of central government action. Elected local

councils remain the most important element when the local government system is considered

overall (they are the main multi-functional service providers, covering the whole country

and spending the largest proportion of locally budgeted resources). However, in particular

fields of local government activity, such as local economic development, and education and

training, a range of new institutions and agencies have grown up with considerable

governmental powers but no direct electoral accountability. Some commentators argue that

such organisations help to ‘get things done’ by bypassing the sometimes cumbersome

processes of local council decision-making. Many others, however, see the growth of non-

elected local government in much more negative terms as removing significant areas of

service provision from democratic control by local communities through their elected

representatives.

The agencies concerned are often referred to as ‘quangos’ (quasi-autonomous non-

governmental organisations), although technically many of them are not quangos in the

strict sense. In official government terminology, quangos are known as ‘non-departmental

public bodies’ (that is, bodies set up by the government, with members appointed by the

government, to undertake certain public functions outside the activities of existing

government departments). Many of these organisations are national in scope and do not

form part of non-elected local government.

At the start of this chapter I defined local governance as the process of the formation

and implementation of public policy at the local level involving both elected and non-elected

organisations. Non-elected organisations are thus central to the overall governance of

localities. The range of non-elected agencies involved is considerable. Two examples will

give a flavour of their importance.

Until the late 1980s, state education until the age of 18 was governed by local councils

acting as local education authorities or LEAs (except in central London, where a single

‘Inner London Education Authority’ covered a number of boroughs). Councils provided

schools, appointed teachers, determined educational policy and funded colleges of further

education. From the late 1980s, parents were given the right to vote to ‘opt-out’ of local

authority control and to see their children’s school funded directly by central government

(this is known as Grant Maintained Status) and governed by its own board of governors,

including some elected from among the parents. Supporters of this scheme argued that it

gave more power to parents to influence their children’s education, increased efficiency

because there were no council overheads, and allowed head teachers to run schools without

interference from councils. Opponents claimed that the system would increase inequalities

between schools (with Grant Maintained Status being adopted by schools in better-off

neighbourhoods and poorer schools that remained with local councils being increasingly

underfunded), remove democratic oversight of education from local communities and result

in greater inefficiency because county-wide economies of scale would be lost.

In the field of local economic development, the Conservative government set up a

series of Urban Development Corporations (UDCs) in the most run-down areas of major

cities, such as Newcastle, Manchester, Merseyside and Leeds. UDCs were given sweeping

powers to initiate and control urban redevelopment, based on the regeneration of the physical

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GOVERNANCE

313

infrastructure in inner-urban areas. Each UDC was governed by a board whose members

were appointed by the government. Although each UDC included representatives of elected

local government, the UDC itself was outside the control of local government and effectively

took over the functions of local government within its development area with respect to

planning and local economic development. In many cases relations between the UDCs and

the elected councils in their areas were frosty, or even hostile. Supporters of UDCs claim

that they have managed to transform the physical environment in their areas, dramatically

improving the cityscape much more quickly and comprehensively than would have been

possible by normal local government means. Critics claim that they are anti-democratic,

with only a limited voice for the local communities in which they work and that their much-

vaunted improvements are mainly cosmetic, and have largely failed to produce employment

and social regeneration to match the regeneration of the landscape.

During the 1990s the emphasis has moved away from single specialist agencies to

partnership forms of local governance. A partnership consists of a number of organisations,

elected local authorities, unelected bodies (such as UDCs, Training and Enterprise Councils

and Health Authorities), private companies and voluntary and community organisations

acting together for a common purpose, often related to community development. The

main potential strength of a partnership is that it brings together expertise and resources

from a number of different sectors which, it is hoped, will add up to more than the sum of

the parts and represent a wider cross-section of local interests than a single agency could.

Critics argue that partnerships are weak, because they can lack overall co-ordination and

have no means of ensuring the participation of unwilling partners. Partnerships too are by

definition unelected and their popularity further increases the size of non-elected local

government.

The geography of non-elected local government is inevitably complex because of the

number and range of agencies involved. Some non-elected agencies, such as Training and

Enterprise Councils (which are based on local labour markets), cover the whole of the

country. Others, such as UDCs, are highly localised and cover small areas of city-centres,

but aim to have much wider effects. The system of Grant Maintained Status for schools is a

national scheme, but its take-up by parents has been very uneven, with schools in more

affluent areas tending to adopt Grant Maintained Status and those in poorer localities staying

with the local authority. In other words there are multiple geographies of non-elected local

government which combine with elected local government in different ways in different

places to produce a highly differentiated and complex map of local governance.

The future of local governance

The system of local governance involving both elected councils and unelected agencies

continues to develop and change. Over the coming years the new pattern of unitary authorities

in Wales, Scotland and some parts of England will be consolidated and a judgement will be

possible about their effectiveness and popularity. The recent growth of non-elected local

government and the parallel decline in public interest in elected local government (reflected

in very low turnout figures for local elections) are causes of concern to many. In its recent

White Paper (Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions 1998), the new Labour

government has brought forward proposals to reform and democratise local government to

make it more responsive to the views of local people. One of the most important initiatives

JOE PAINTER

314

is the option for councils to have a directly elected mayor who would act as a kind of local

president. Proponents of this scheme suggest that a high profile mayoral election would

generate much greater interest in and enthusiasm for local government and politics than is

currently the case. Others suggest that it would place too much power in the hands of one

person and distract attention from the real social and economic problems facing many parts

of the country. Other ways of involving citizens more directly in local decision-making,

such as citizens’ panels and focus groups, are also being tried out in many areas. It remains

to be seem whether such initiatives will succeed or whether a greater degree of devolution

of political power and financial resources will also be required to install genuine local

democracy in the United Kingdom.

References

Byrne, T. (1992) Local Government in Britain (revised 5th edn), London: Penguin.

Central Office of Information (1996) Local Government, London: HMSO.

Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions (1998) Modern Local Government: In Touch

with the People, Cm 4014, London: HMSO.

Duncan, S. and Goodwin, M. (1988) The Local State and Uneven Development, Cambridge: Polity

Press.

Wilson, D. and Game, C. (with Leach, S. and Stoker, G.) (1994) Local Government in the United

Kingdom, London: Macmillan.

Further reading

The best and liveliest introduction to UK local government is provided by D.Wilson and

C.Game. (with S.Leach and G.Stoker) (1994) Local Government in the United Kingdom

(London: Macmillan). Their book covers the whole of the subject in reasonable detail and

in a very accessible way. A less comprehensive, but also lively treatment of the turbulent

period of the 1980s and the early 1990s, is provided in A.Cochrane (1993) Whatever

Happened to Local Government (Buckingham: Open University). A very thorough account

of most aspects of British local government is T.Byrne (1994) Local Government in Britain;

6th edition (London: Penguin). The post-war history is documented in a scholarly overview

by K.Young and N.Rao (1997) Local Government Since 1945 (Oxford: Blackwell). An

important discussion of the issue of local citizenship is provided by D.M.Hill (1994) Citizens

and Cities (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf). Different theoretical approaches to

local governance are covered by the contributions to D.Judge, G.Stoker and H.Wolman

(1995) Theories of Urban Politics (London: Sage). Local elections in Britain are analysed

in detail by the foremost authorities on them in the UK in C.Rallings and M.Thrasher (1997)

Local Elections in Britain (London: Routledge). Finally, three periodicals: the annual

Municipal Yearbook provides an encyclopaedia of UK local government on a service-by-

service and council-by-council basis. Packed with facts, figures, names and addresses, it is

an essential tool for any research project on local government; Local Government Studies

carries a range of scholarly articles on the subject; and the fortnightly Municipal Journal

provides topical coverage of local government news as well as feature articles on current

developments.

315

Chapter 16

A (dis)United Kingdom

Charles Pattie

Introduction

National identity is an act of imagination, a social construct (Anderson 1983). Outside

nationalist ideology, nations are not mono-ethnic, mono-cultural entities. The United

Kingdom, no exception, has always been a multi-ethnic, multinational state which has grown

by the incorporation of smaller nations. Wales was incorporated into England in 1536.

Scotland joined the Union in 1707. Ireland apart (where, despite the 1801 Act of Union,

nationalist sentiments continued, culminating in independence for southern Ireland in 1922),

those living in the constituent parts of the United Kingdom have generally shared a common

sense of ‘Britishness’, over and above loyalties to their own nations. That shared identity,

forged in the eighteenth century from a mix of Protestantism, war and nascent Empire

(Colley 1992), was sufficiently flexible to allow most citizens of the United Kingdom to

hold a sense of dual nationality—both British and Scottish, for instance.

By the mid-twentieth century, regional and ethnic loyalties appeared to have been

replaced by a sense of shared nationhood as economic progress enhanced communications

across the ‘national’ territory (Agnew 1987). National politics were dominated by left-right

ideological debates between the Labour and Conservative parties. Neither the unity nor the

long-term future of the United Kingdom were in question.

At the end of the twentieth century, however, that judgement seems premature. The

1970s and 1980s saw social and political upheaval, as the major parties gradually abandoned

the policy nostrums of the post-war period. After a prolonged period in which Britain had

become a more equal society, the pendulum swung back, and by the end of the century

society was arguably more unequal than at any time since the Second World War.

Meanwhile, Westminster’s authority was increasingly challenged. The factors creating

a sense of Britishness in the eighteenth century had lost their resonance. Nationalist

movements in the Celtic Fringe were increasingly assertive, and legislation establishing