Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

276

Chapter 14

Cultures of difference

Peter Jackson

Introduction

During the 1980s, geography (along with most of the other social sciences) underwent a

‘cultural turn’, involving a widening of its academic horizons and an increasing openness to

a range of intellectual movements including feminism and post-colonial studies. As a result

of the growing dialogue between social geography and cultural theory, the study of cultural

geography was transformed to emphasise a plurality of cultures and the multiple geographies

(landscapes, spaces and places) with which those cultures are asscociated (Jackson 1989).

Rather than approaching culture in narrowly aesthetic terms, cultural geographers embraced

a much wider agenda, exploring the many ways in which people attach meaning to places,

investing the material environment with cultural significance. As meanings and values vary

over time, from place to place, and between groups and individuals, geographers quickly

became immersed in complex issues of cultural politics, whereby dominant ideologies are

negotiated and contested by those in less powerful positions.

This chapter applies these ideas to the changing geography of the United Kingdom

during the 1980s and 1990s. It suggests that these decades have been characterised by a

growing sense of multiculturalism, when what it means to be ‘British’ has been undergoing

rapid change. While some have welcomed these changes, acknowledging a growing tolerance

of cultural difference as a positive feature of contemporary British society, others have seen

them as undermining what they regard as the core values of ‘Britishness’ or as a threat to

older forms of solidarity that appear to be fragmenting into ever more complex and plural

identities. This chapter will argue that cultures cannot be contained within narrowly defined

national boundaries. Notions of ‘Britishness’ are unstable and unbounded, a hybrid blend

of diverse cultural influences that originate from (and extend) well beyond the national

boundaries. An openness to cultural difference therefore implies a shifting sense of national

identity which many find threatening. Some of those who align themselves politically on

CULTURES OF DIFFERENCE

277

the Left have seen the rise of ‘identity politics’ as a threat to the allegedly ‘universal’ appeal

of class-based politics, while many on the Right have sought a return to an apparently more

stable sense of national identity. This chapter aims to chart this dynamic cultural geography

through an exploration of the UK’s increasingly complex ‘cultures of difference’.

The chapter begins with an example of those who would deny or seek to limit the

extent of cultural difference. It goes on to map various forms of multiculturalism that

characterise the UK’s changing geography, exploring the extent to which cultural differences

have been subsumed within the market through the process of commodification. The chapter

ends with a discussion of the limits of tolerance, arguing that ‘living with difference’ will be

a major social and political challenge as we enter the new millennium.

The denial of difference?

According to Lord Tebbit, speaking at a fringe meeting of the Conservative Party conference

in October 1997, multiculturalism is a divisive force in British society. No one, Norman

Tebbit argued, can be loyal to two nations. Immigrants should be taught that the Battle of

Britain is part of their history. The alternative, Tebbit warned, is the kind of ethnic and

cultural division that led to the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. His words recalled earlier

interventions from right-wing politicians, including Enoch Powell’s ‘rivers of blood’ speech

in 1968 which warned of the inevitability of violent conflict if immigration was permitted

to continue unchecked. Lord Tebbit had himself made several earlier speeches on the subject

of multiculturalism, including his infamous ‘cricket test’ speech in 1990 when he argued

that the loyalty of ethnic minorities should be judged by whether they supported the English

cricket team: ‘Which side do they cheer for?’ he asked. ‘Are you still harking back to where

you came from or where you are? I think we’ve got real problems in that regard.’ Suggesting

that many British Asians continued to search for husbands and wives in the family’s native

country, he concluded that ‘you can’t have two homes. Where you have a clash of history,

a clash of religion, a clash or race, then it’s all too easy for there to be an actual clash of

violence’ (The Times, 21 April 1990).

Unlike these earlier speeches, however, Tebbit’s comments at the 1997 Conservative

Party conference received very little public support. The Tory leadership rapidly distanced

itself from his remarks, claiming that Lord Tebbit was out of touch with the mood of the

country, while the Queen spoke out in praise of ethnic minorities. The recognition of cultural

difference is no longer the unique preserve of left-leaning cultural critics. Even the right-

wing press has come to accept a more ‘hybrid’ view of British national identity. While the

Daily Mail printed Tebbit’s speech in full, the Daily Telegraph took a very different tack,

arguing that ‘A child with a Welsh father and a mother from Ulster can eat Indian food,

listen to reggae, and watch Italian football without experiencing cultural confusion and

political alienation’ (9 October 1997). As Stuart Hall argued in a Guardian interview, the

denial of difference is no longer tenable: ‘You can’t go on, generation after generation,

denying immigration’ (11 October 1997).

While it may no longer be a popular public position, Lord Tebbit’s denial of difference

has deep roots within British society. For a nation that prides itself on its tolerance and

sense of fair play, British history is marred with recurrent outbreaks of anti-Semitism, racism

and xenophobia (Holmes 1991). Given this persistent ambivalence about multiculturalism,

defining ‘the nation’ has often been problematic. When T.S.Eliot (himself an American

PETER JACKSON

278

émigré) sought to define the ‘national culture’ shortly after the Second World War, he reeled

off a bizarre list of ingredients: ‘Derby Day, Henley Regatta, Cowes, the twelfth of August,

a cup final, the dog races, the pin table, the dartboard, Wensleydale cheese, boiled cabbage

cut into sections, beetroot in vinegar, nineteenth-century Gothic churches and the music of

Elgar’ (1948:31). This exclusionary vision of Britain was later parodied by Hanif Kureishi,

reflecting Britain’s increasing multiculturalism. For Kureishi, British culture would now

include: ‘yoga exercises, going to Indian restaurants, the music of Bob Marley, the novels

of Salman Rushdie, Zen Buddhism, the Hare Krishna Temple, as well as the films of Sylvester

Stallone, therapy, hamburgers, visits to gay bars, the dole office and the taking of drugs’

(1986:168–9).

It is not simply that ‘British culture’ has been enriched by ‘ethnic diversity’. The

very existence of separate (national or ethnic) cultures is now in doubt. Popular music is

a particularly good instance of this kind of ‘hybridity’ with bhangra frequently cited as a

key example of such intercultural fusion. Performed by artists such as Apache Indian,

bhangra blends a range of sounds from Punjabi folk styles to African-American house

music and is listened to by a variety of audiences from Bombay to Brixton. Acording to

one observer:

Bhangra created an over-arching reference point cutting across cleavages of nationality

(Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and other), religion (Sikh, Muslim and Hindu) and

caste and class…[Its emergence] in the 1980s signalled the development of a self-

conscious and distinctively British Asian youth culture.

(Back 1996:219–20)

Or in the words of one young person from Bradford:

We’ve got bhangra happening. It’s amazing. I love listening to people like Apache

Indian because that’s literature and music and dance all together and it’s a mixture,

it’s all in fusion. He’s saying Urdu, Punjabi, English, everything thrown together.

He’s rapping away…and he’s going on about arranged marriages, and there’s Indian

instruments in the background, there’s western instruments. And when you see him

on TV, there’s Indian dancers and there’s Afro-Caribbean men doing his stuff, Asian

kids doing their stuff, and there’s white kids doing their bit. I just think, ‘Wow!’ I just

think all this fusion will throw up new art forms. New things will come, they’re already

happening and it’ll be really nice to see where we end up in a few years to come.

(Bradford Heritage Recording Unit 1994:164–5)

It is possible, of course, from a position of cultural privilege, to romanticise the blending

of cultures and to champion the emergence of ‘hybrid identities’ with too little concern for

the material conditions that enable a positive fusion of cultures to be achieved. Picking and

mixing is certainly easier for those with sufficient economic and cultural resources. But, at

least in some instances, it seems clear that academic understanding of ‘multiculturalism’ is

being outstripped by people’s everyday practices. Producing and consuming such hybrid

cultural forms transcends established boundaries of taste and nation, compelling social

scientists to coin new terms such as ‘inter-being’ and ‘multiculture’ in an effort to map the

contours of the UK’s changing cultural geography.

CULTURES OF DIFFERENCE

279

As these examples suggest, the United Kingdom is now a thoroughly multicultural

place, though one might question how deeply the tolerance of cultural diversity extends.

Even a cursory reading of the national newspapers shows plenty of evidence of continued

intolerance towards minorities of every kind, underpinned by legal and other forms of

institutional exclusion. Examples include recent debates about lowering the age of consent

for homosexual sex, persistent evidence of sexual and racial harassment in the police and

armed forces, and the orchestration of recurrent ‘moral panics’ against single mothers

(McRobbie 1994). Differences of ‘race’, religion, sexuality and gender still provoke prejudice

and evoke widespread hostility. Mapping the extent of ‘British’ multiculturalism allows us

to reflect on the limits of tolerance as well as on the possibilities of mutual recognition and

understanding.

Mapping multiculturalism

‘Britishness’ can no longer be confined (if it ever could be) within the boundaries of the

nation-state. Britain’s imperial past established a series of transnational connections that

continue to be reproduced through the economic networks of multinational corporations,

amplified by the flow of capital, the migration of labour and the transmission of ideas and

other kinds of information. While some movements are controlled by nationality and

immigration laws, other boundaries are more permeable, such as the relatively free movement

of information and ideas across the Internet. As a result, ‘British culture’ has, for many

years, exceeded the political boundaries of the United Kingdom.

In terms of international migration, for example, Britain has been a net exporter of

labour for most of the post-war years. The single most important source of immigration has

been the Irish Republic. Yet it has been immigration from the New Commonwealth and

Pakistan that has generated the most intense public debate, fuelled by concerns over the

‘assimilation’ of ethnic minorities. As overt racism has become less publicly acceptable it

has been transformed into a more subtle cultural form. A polite concern for cultural difference

may then disguise much more sinister racialised fears. Margaret Thatcher’s comment in

1979 about the country being ‘swamped by people with a different culture’ has often been

interpreted in this light as has the racialised subtext of concerns for the ‘inner city’, for ‘law

and order’ and other apparently ‘non-racial’ subjects (Jackson 1988).

From this perspective, debates about ‘race’ and racism can be seen as central to British

political debate rather than of only marginal concern. This helps explain why public anxiety

about immigration often seems so out of proportion to the actual numbers of ‘immigrants’

(and their descendants) who have settled in the UK. According to the 1991 Census, less

than 5 per cent of Britain’s population were from ‘non-white’ ethnic groups, with the Muslim

population generally estimated at around 2 per cent.

1

The ethnic minority population is,

however, far from evenly distributed across the country, with the heaviest concentrations in

urban areas, particularly in London, the West Midlands and the older industrial cities of the

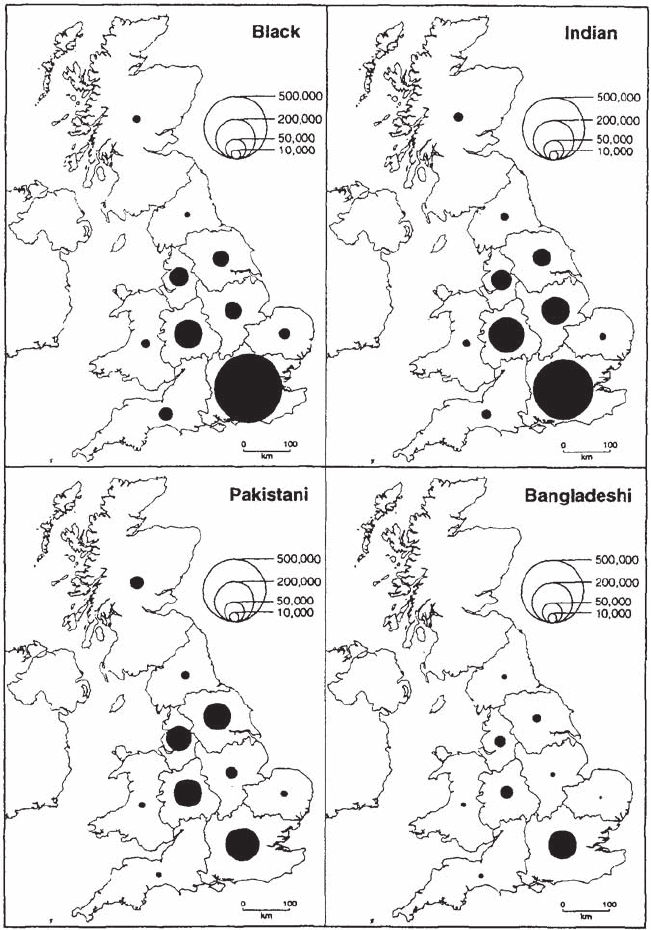

North and North West (see Figure 14.1). Localised concentration in areas of declining

economic opportunity has given rise to the potential for conflict, creating in Lord Scarman’s

analysis of the Brixton riots ‘a predisposition towards violent protest’ (1981:2.38).

The migration of people has also led to a flow of commodities and cultures. British

multiculturalism is often referred to in these terms, with references to ‘samosas and saris’ or

a blending of ‘roast beef and reggae music’ (Sarup 1986; Jeater 1992). This may, however,

PETER JACKSON

280

FIGURE 14.1 Distribution of ethnic groups, 1991

Source: OPCS, Census of Population, 1991.

Note: The Census category ‘Black’ includes Black-Caribbean, Black-African and Black-Other.

CULTURES OF DIFFERENCE

281

involve only a superficial involvement with other cultures as opposed to a more fundamental

acknowledgement of the political rights of minority groups and the provision of equal

economic opportunities. An understanding of the ‘culture of commodities’ allows some

further reflections on the nature and limitations of British multiculturalism.

The tendency to engage with other cultures on a purely superficial level is nowhere

clearer than in relation to culinary culture. Researching the consumption of ‘ethnic’ food in

North London, two geographers provide this wonderful illustration from the listings

magazine, Time Out (16 August 1995):

The world on a plate. From Afghan ashak to Zimbabwean zaza, London offers an

unrivalled selection of foreign flavours and cuisines. Give your tongue a holiday and

treat yourself to the best meals in the world—all without setting foot outside the fair

capital.

(Cook and Crang 1996:131)

But what exactly are we consuming when we indulge our tastes for such ‘exotic’ food and

what other cultural meanings are at stake?

Research in the gentrifying inner-city neighbourhood of Stoke Newington in North

London suggests that food consumption is related to a whole range of social issues, including

the formation of class-based identities. Residents in this study were shown to be using their

economic and cultural capital (money and educational resources) to indulge in ‘a little taste

of something more exotic’, including a preference for ‘exotic’ dishes such as Thai food,

pizza or curry rather than an ‘ordinary sandwich’ (May 1996). But the cultural politics of

food is far more complex than we might at first think. The British taste for curry, for example,

can be traced back through generations of colonial exchange between Britain and India.

Taken from a Tamil word (kari), ‘curry’ originally referred to a range of local masalas,

prepared for consumers ‘back home’ via the British invention of curry powder (Crang and

Jackson in press). Some of the most basic signifiers of British culinary taste, such as the

good old ‘English’ cup of tea, also have more complex cultural roots. As Stuart Hall has

demonstrated, the ‘English cuppa’ may be an accepted symbol of national identity but its

origins are anything but British:

Because they don’t grow it in Lancashire, you know. Not a single tea plantation exists

within the United Kingdom…. Where does it come from? Ceylon-Sri Lanka, India.

That is the outside history that is inside the history of the English. There is no English

history without that other history…. People like me who came to England in the

1950s [from the West Indies] have been there for centuries; symbolically, we have

been there for centuries…. I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea. I am

the sweet tooth, the sugar plantations that rotted generations of English children’s

teeth. There are thousands of others besides me that are…the cup of tea itself.

(Hall 1991:48–9)

The quintessentially ‘English cuppa’ is, then, the product of globally extended commodity

networks. Yet these complex cultural origins are conveniently forgotten in countless daily

acts of domestic consumpton. A similar process of selective forgetfulness applies to the

foreign (immigrant Jewish) origins of high street favourites such as Marks & Spencer, now

PETER JACKSON

282

widely regarded as purely and simply ‘British’. Even the ‘national dish’ of fish and chips

conceals a hybrid cultural history involving French styles of preparing fried potatoes and an

East European Jewish tradition of frying fish (Back 1996:15).

A similar argument can be applied to our understanding of ‘English’ literature,

where even the most revered works, such as Jane Austen’s novels, can be shown to exhibit

complex multicultural geographies. Though now regarded as a staple feature of our national

culture (with film and television adaptations attracting millions of viewers) and as an

outstanding representation of ‘British’ culture abroad (via exports worldwide), the

geography depicted in the novels stretches well beyond the UK. As Edward Said’s work

on Culture and Imperialism (1993) demonstrates, the plot of Jane Austen’s Mansfield

Park (1814) revolves around Sir Thomas Bartram’s absence from Britain, attending to his

plantation in Antigua. His departure allows for a temporary absence of moral restraint

which is only restored by his timely return at the end of the novel. Said charts a complex

cultural geography of overlapping territories and intertwined histories where, even in the

apparently tranquil world of Jane Austen’s novels, events ‘over here’ are crucially

connected to distant events ‘over there’.

The flow of people, information and goods has, of course, increased dramatically

since the nineteenth century with the process of ‘time-space compression’ now characteristic

of our post-modern world (Harvey 1989). In such circumstances of change and instability it

should be no surprise that representing the ‘national culture’ is becoming evermore

problematic. The world of advertising is a particularly good illustration of this tendency,

with its need to boil down complex ideas into brief, concentrated messages. Long-established

symbols of national identity no longer have unambiguously positive meanings. The Union

flag, for example, has been endowed with right-wing associations, including some of the

most virulent forms of exclusionary racism such as those associated with the National Front

and the British National Party (Gilroy 1987). How, then, are more recent appropriations of

the national flag to be interpreted? What does it signify about our ‘national culture’ when

the Spice Girls drape themselves in the Union Jack or when Patsy Kensit and Liam Gallagher

wrap it around themselves on the cover of Vanity Fair? Why, too, have British Airways

dropped the flag from their airline livery in a multi-million pound refit, designed to help

retain its position as ‘the world’s favourite airline’ via a more outward-looking multicultural

image, while the Labour Party included the flag in its New Labour, New Britain, New Vision

electoral campaign in 1997, along with the British bulldog?

Other symbols of ‘national unity’ have also been refigured in recent years. The Royal

Family, for example, no longer evokes an unequivocal sense of national loyalty. Despite the

nationwide outpouring of grief over the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997, revelations

of Prince Charles’s adultery, together with the Queen’s reluctance to pay income tax or to

curb expenditure on ‘luxuries’ such as replacing the royal yacht, have all damaged the

credibility of the Royal Family (though there is as yet no serious discussion within Britain

of an alternative to the monarchy).

Imagining the nation is now much more complex and cannot be represented in

unambiguously ‘heroic’ terms. One response has been the emergence of a nostalgic concern

for ‘national heritage’, accompanied by the proliferation of industrial museums, heritage

sites and commercial ventures such as the Past Times chain of high-street stores—a

romanticisation of the past that is inevitably associated with a sense of national economic

decline (Wright 1985). Another response has been the emergence of more critical ‘visions

CULTURES OF DIFFERENCE

283

of Britain’. In the cinema, for example, such a view can be traced back at least to Steven

Frears’s bleak representation of the inner city in Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987). But it

is now a much more widespread and acceptable way of seeing, with images of urban decline

now a central motif in some of the most popular British films such as Trainspotting, Twin

Town and The Full Monty, set respectively in Edinburgh, Swansea and Sheffield.

The sociologist Anthony Giddens (1991) refers to the weakening of long-established

sources of identity as the advent of ‘post-traditional’ society, characterised by a plurality of

new sources of identification. Traditional class-based identities, for example, rooted in stable

working-class communities, with the expectation of a job-for-life, clear gender divisions

and a relative lack of social and spatial mobility, have been thoroughly disrupted by the

process of industrial restructuring and the move to more flexible modes of capital

accumulation. New sources of identity have emerged, associated with the politics of health

and the body, gender and sexuality, environmentalism, nationalism and a host of other social

movements.

In many cases, these new forms of politics have come to be associated with particular

local geographies or ‘sites of struggle’. Think, for example, of the way that ‘race’ politics in

Britain were shaped by the Brixton riots, or how recent developments within the women’s

movement came to be associated with the protests at Greenham Common. Similarly, the

development of environmental politics using various forms of non-violent direct action

have come to be associated with the protests over live animal exports at Brightlingsea and

with opposition to the construction of the Newbury bypass or the extension of the runway at

Manchester airport.

For some activists on the Left, these multiple forms of ‘identity politics’ are, at best,

a mixed blessing. At worst, they are interpreted as a threat to traditional forms of class-

based solidarity. Writing in the New Left Review, for example, Eric Hobsbawm (1996)

contrasts the particularism of ‘identity politics’ and their appeal to sectional interests of

gender, ethnicity and sexuality, with the alleged universalism of class-based politics. While

it could be argued that class politics in the UK were far from ‘universal’ in their very partial

incorporation of women and ethnic minorities, for example, Hobsbawm warns that identity

politics will never be able to mobilise more than a minority of the population. Others have

taken a more optimistic view of the ‘New Times’ (Hall and Jacques 1989), arguing that new

social movements have the potential to include many of those who were excluded from

traditional forms of labourism.

Commodifying cultural difference

One of the most significant responses to the proliferation of cultural difference has been the

attempt to commodify the process, to exploit its exchange value within the marketplace.

For some observers this is a cynical move within contemporary ‘consumer culture’, designed

to capitalise on difference, using ethnicity, for example, as a kind of ‘spice’ to liven up the

dull dish of mainstream white culture (hooks 1992). From this perspective, the

commodification of difference threatens to undermine the ‘authenticity’ of autonomous

cultural production and dull the radical edge of oppositional cultures. What happens, such

critics ask, when Malcolm X’s political vision is appropriated by Spike Lee and transformed

into a range of merchandise, from tee shirts to baseball caps, designed to promote a major

motion picture? Does it matter that the movie-maker is African-American or that the tee

PETER JACKSON

284

shirts and baseball caps are worn by teenagers across the world, many of whom have only

a limited understanding of Malcolm X’s politics?

It is certainly possible to think of ways in which ‘the united colours of capitalism’

(Mitchell 1993) lead to a diminution of cultural autonomy and involve only the most

superficial commitment to multiculturalism. But notions of ‘authenticity’ are of

questionable significance if we accept the earlier arguments about the increasingly ‘hybrid’

character of contemporary culture. Rather than searching nostalgically for the roots of a

lost ‘authenticity’, geographers are now seeking to explore the routes of different forms

of cultural production and their associated ‘displacements’ (Crang 1996). In the previous

example, this would mean examining the way that Malcolm X’s message was transformed

as it moved through different media, being adopted and deployed in different contexts

and by different groups, all of whom are situated differently in terms of the social relations

of ‘race’, class and gender. A ‘horizontal’ logic of connection and differentiation comes

to replace the ‘vertical’ logic of depth and authenticity that has dogged cultural studies

for so long.

To pursue these ideas, let us examine a couple of examples in more detail: the first

concerning the commodification of ‘youth culture’ in the Manchester club scene during the

1980s; the second concerning the commodification of contemporary masculinities through

the growth of the UK’s men’s magazine market.

The ‘Madchester scene’

Following the post-war decline of manufacturing employment, Manchester (along with

many other northern industrial cities) made a concerted effort to reposition itself to take

advantage of the expansion of job opportunities in the service industries (retailing, financial

services, tourism, etc). Besides the attraction of external economic investment, this has

also involved an attempt to raise the city’s cultural profile through a series of initiatives,

including a bid to host the Olympic Games, the construction of an exhibition centre (the

G-Mex), an arts centre (the Cornerhouse) and a new concert hall (the Bridge water Hall).

Another aspect of this ‘cultural renaissance’ was the development of the ‘Madchester’

club scene, built on the success of local ‘independent’ bands like The Smiths, Inspiral

Carpets, the Stone Roses, the Charlatans and Oasis. Commenting on the distinctiveness

of the city’s independent music scene, Halfacree and Kitchin provide this (highly

contentious) chronology:

First, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was the distinctive post-punk sound

of Joy Division, which mutated into the slightly more cheerful tones of New Order.

Bedsit blues returned in the mid 1980s with The Smiths and James, whilst the tempo

and mood was revived around 1988, in the wake of ‘Acid House’, with the arrival

of the club-and-Ecstasy sounds of ‘Madchester’ led by The Happy Mondays, The

Stone Roses and Oldham’s Inspiral Carpets…Madchester was pronounced ‘dead’

by 1991–2.

(Halfacree and Kitchin 1996:50–3)

As Ian Taylor’s recent study has shown, however, the transformation in Manchester’s cultural

life resulted not only from ‘the raw populism of the music and the creative energy of a series

CULTURES OF DIFFERENCE

285

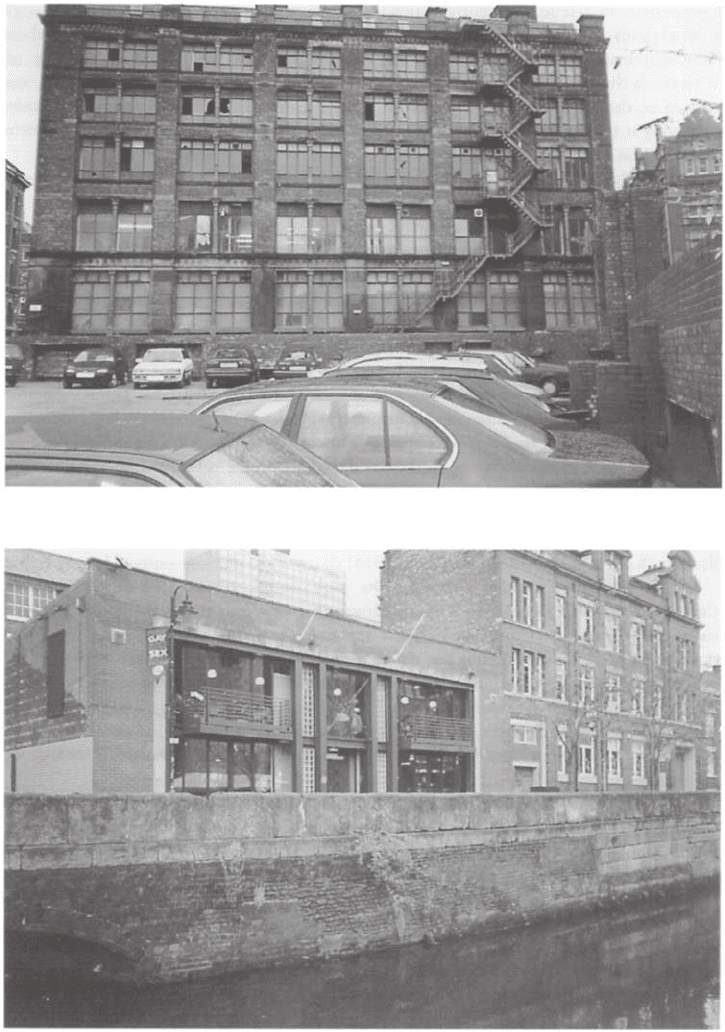

FIGURE 14.2 Canal Street: ‘before’ and ‘after’ reinvestment in Manchester’s Gay Village

Source: Peter Jackson.