Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

296

Chapter 15

Local government and governance

Joe Painter

Introduction

All modern societies are governed and over the past 300 years (and especially since the

nineteenth century) the territorial nation-state has developed as the dominant form of

government to the point where almost the entire land surface of the globe is divided politically

into a mosaic of states. The dominance of the nation-state has recently been challenged by

processes of global economic and political transformation, and some commentators predict

that the conventional nation-state will lose its pre-eminence as the basic building block of

the world political map. Nevertheless, for the time being, the state remains as the most

important structure of government for most purposes. On the other hand, only the tiniest of

nation-states are able to carry out the numerous functions and processes of government

through a single, national, set of institutions. The territories and populations of almost all

countries are large enough to justify, or even to require, one or more additional tiers of

government and administration organised at spatial scales below that of the nation-state.

The form and function of these different tiers and the relationships between them can vary

widely from country to country. In the United Kingdom a more or less uniform two-tier

structure of formal local government was in place from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s.

Since then a much more complex picture has emerged, with a number of places acquiring a

new single-tier system of local government. In addition new devolved regional governments

are being established in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (albeit different in each case),

while the English regions have seen a degree of administrative decentralisation with the

setting-up of government offices for the regions with responsibility for the organisation of

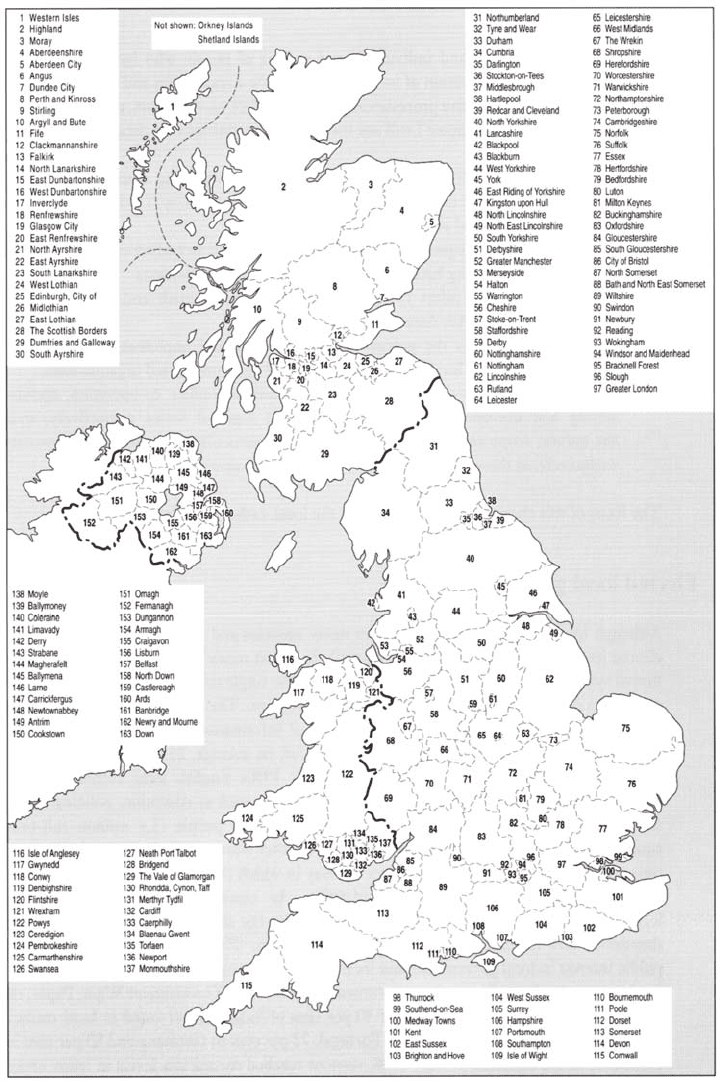

a range of central government services at a regional scale (Figure 15.1).

Further complexity is added if we broaden the focus to consider local governance and

politics as a whole rather than limiting discussion to the system of formal, elected local

councils. Here we need to consider a range of unelected public agencies, voluntary

297

FIGURE 15.1 The ‘top tier’ of local government in the UK from April 1998: counties (including

former metropolitan counties and Greater London) and new unitary authorities

JOE PAINTER

298

organisations, businesses, and individuals and groups of people who have a role in the

formulation and implementation of local policies and the organisation and delivery of local

services, as well as the ongoing processes of political conflict, co-operation, campaigning

and decision-making. In this chapter I will use the following definitions for these various

terms:

¿ Local government refers to elected local councils comprising county and district councils

and the new unitary (single-tier) councils where those exist. Local councils are also

known as local authorities.

¿ Local governance is the process of the formation and implementation of public policy at

the local level involving both elected and non-elected organisations.

¿ Regional government refers to the newly developing Scottish and Northern Irish

governments and Welsh Assembly.

¿ Regional governance is the process of the formation and implementation of public policy

at the regional level involving both elected and non-elected organisations.

¿ Local politics and regional politics refer to processes of conflict, co-operation, agenda-

setting and decision-making at the local and regional scales respectively, over the nature,

scope and content of public policy, particularly, though not necessarily exclusively, as

these affect the locality or region concerned.

The focus of this chapter is on governance at the local, rather than the regional, scale.

Elected local government

Although local governance today involves many agencies and organisations in addition

to elected local councils, and while local councils have lost many of their former powers,

the formal system of elected local government remains the single most important element

in the geography of local governance in the United Kingdom. The scale of the system

can be seen from some simple statistics (Central Office of Information 1996). Between

1984 and 1994, local authorities together were responsible for, on average, 25.39 per

cent of general government expenditure in Britain. In the early 1990s English local

authorities were spending about £45 billion a year on providing services such as

education, policing, social services and transport, and employing almost 2 million people

(1.4 million full-time equivalents) to deliver them. Local government, in other words,

is big business. At the same time, the discretion of local councils over the way in which

their resources are allocated has been significantly eroded since the mid-1970s. An

extensive programme of national legislation has been enacted to regulate and constrain

the ability of councils to decide for themselves how to respond to local needs and

demands. There has also been a decline in public interest in local government and local

elections that may be related to this decline in local autonomy. According to the

government’s recent Local Government White Paper, on average, in recent elections

only about 40 per cent of local electors voted in local council elections compared with

60 per cent in Portugal, 72 per cent in Germany and 80 per cent in Denmark; in the

elections of May 1988, turnout reached record low levels in many areas. New government

proposals in the ‘White Paper’ of July 1998 aim to redress some of these problems

(Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions 1998).

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GOVERNANCE

299

The development of elected local government

A brief history

The origins of local self-government in Britain are ancient. From the twelfth century cities

and certain towns (called boroughs or burghs) were given the right to manage their own

affairs by royal charter. The system failed to keep pace with social change however, and by

the early nineteenth century some ancient boroughs were virtually depopulated but still

retained political privileges, such as the right to elect members of parliament (these became

known as the ‘rotten boroughs’), while other settlements had expanded substantially in the

wake of the Industrial Revolution but did not have the privileges of borough status. The

shire counties are also of ancient origin and provided a framework for military defence and

the justice system. The smallest scale of local government was the parish, which had

responsibility for the relief of poverty (albeit on a very limited scale by modern standards).

The nineteenth century saw a series of major reforms to the local government system

to do away with the ‘rotten boroughs’, to harmonise structures and to introduce new local

services. In 1835 the Municipal Corporations Act established directly elected corporate

boroughs in place of the self-electing medieval ones. A series of new specialist local

boards was established. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 set up Boards of Guardians

to oversee local poor relief. The Public Health Act 1848 established local health boards,

while highways boards and elementary school boards were established by the Highways

Acts of 1835 and 1862 and the Education Act of 1870, respectively. The latter, together

with the Scottish Education Act of 1872, introduced universal elementary education into

Britain for the first time.

Then at the end of the nineteenth century, three Acts introduced a new system of local

government to England and Wales that was to serve for eighty years. The Local Government

Act 1888 set up sixty-two elected County Councils, including the London County Council,

and sixty-one all-purpose County Boroughs. The Local Government Act 1894 revived parish

councils and established a middle tier (between parish and county) of 535 Urban District

Councils, 472 Rural District Councils and 270 non-county Borough Councils. The London

Government Act 1899 set up twenty-eight Metropolitan Borough Councils in London and

the Corporation of London in the tiny City of London itself. A parallel series of reforms in

Scotland produced a similar but not identical system. Following the Local Government

(Scotland) Act 1929 local government consisted of two tiers. The upper tier had thirty-three

county councils and four ‘counties of cities’ (like the English County Boroughs) in Edinburgh,

Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen. The lower tier comprised twenty-one Large Burghs, 176

Small Burghs and, in the rural areas, 196 District Councils. Parish councils were abolished

as civil authorities.

By the 1960s this system too had become unwieldy and was seen as too complex and

inefficient. In 1974 in England and Wales and 1975 in Scotland a new, and somewhat

simplified, system of local government was put in place. Everywhere (with the sole exception

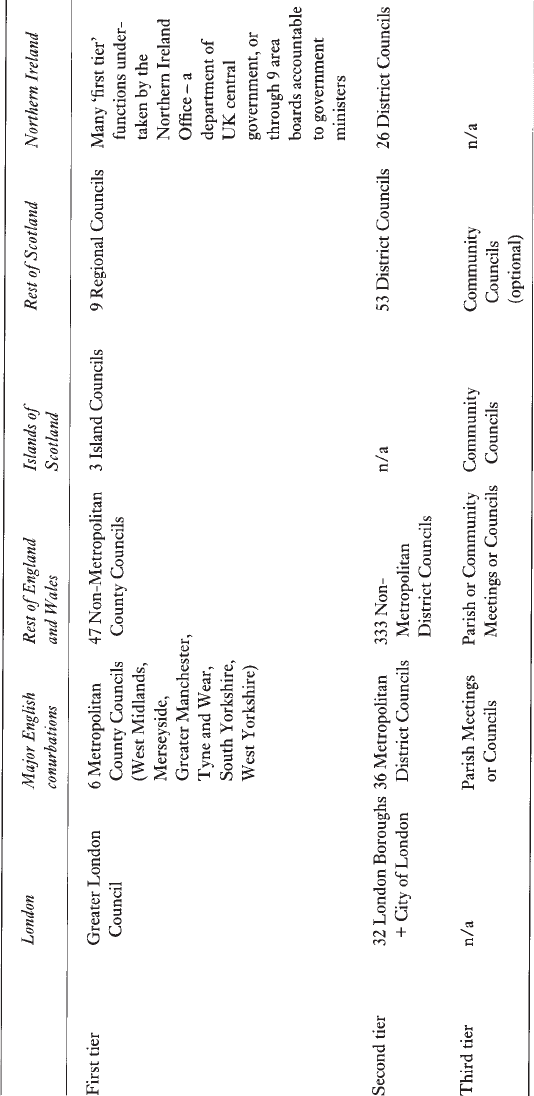

of the Scottish Islands) was now covered by two main tiers. In Scotland, in addition to the

three island councils, there were nine large regional councils subdivided into fifty-three

districts. In England and Wales there were six metropolitan county councils, covering the

major conurbations, divided into thirty-six metropolitan districts; a Greater London Council

(which had been introduced in 1965) and thirty-two London boroughs plus the City of

TABLE 15.1 The structure of UK local government, mid-1970s to mid-1980s

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GOVERNANCE

301

London Corporation in the ‘square mile’; and forty-seven non-metropolitan county councils

divided into 333 non-metropolitan district councils (see Table 15.1).

Current characteristics

Commenting on the key themes of the UK local government system as it stood in the early

1990s, David Wilson and Chris Game (1994) identified seven defining characteristics. First,

it is a system of local government, not local administration. In other words, the system

involves decentralisation of not only administrative authority, but also of political authority:

Local authorities are far more than simply outposts or agents of central government,

delivering services in ways and to standards laid down in detail at national ministerial

level. Their role, as representative bodies elected by their fellow citizens, is to take

such decisions themselves, in accordance with their own policy priorities: to govern

their locality.

(Wilson and Game 1994:20)

Second, and on the other hand, the UK does not have local self-government. In contrast

with community governments in some other countries in Europe (such as Switzerland),

UK local authorities do not possess a ‘power of general competence’; that is, the ability

to act in any way that they feel is necessary to promote local interests or to serve local

populations, unless the action proposed is specifically forbidden. In the UK local councils

can only do those things they are explicitly permitted to do under law. Other actions are

considered ultra vires (beyond the powers). Third, and related to this, UK local government

is wholly subordinate in law to the national government and parliament in London. In so

far as local authorities have any decentralised authority at all, they have it because

parliament has allocated it to them. Local authorities are created by parliament and can

be abolished by it. Fourth, this situation leads Wilson and Game to identify another

characteristic: partial autonomy. Although central government has the theoretical right to

govern all aspects of local authority activity in detail, if it did this in practice the purpose

of the system of local government would have disappeared: it would have become local

administration. The actual history of central-local relations in the UK, therefore, has been

one of a (sometimes uneasy and disputed) balance of powers between local authorities

and the national government, giving rise to a situation of ‘partial autonomy’. Fifth, local

government gains this limited autonomy mainly from the fact that it is directly elected.

Elected councillors are thus accountable to their constituents, and have a degree of

legitimacy not enjoyed by appointed members of health authorities or other local bodies.

Sixth, local councils are multi-service organisations responsible for dozens of local services

from adult education to zebra crossings. Seventh, and finally, local councils are also multi-

functional organisations. Perhaps the best known is ‘direct service provider’ in which the

council undertakes all the activities associated with providing a particular service itself.

Other important roles include:

¿ regulating other organisations and individuals (such as licensing cinemas and taxi drivers);

¿ facilitating activities undertaken by others, such as economic development;

JOE PAINTER

302

¿ contracting with other agencies or private companies to provide services not undertaken

directly by council staff.

In addition to all of these characteristics, Wilson and Game note that local councils

possess one further vital feature: the right to raise taxes. Although this right has been much

reduced, with most local government finance now provided by central government and

local authorities tightly circumscribed by law in their ability to increase local taxes above

centrally set limits, the power to tax remains in principle an important element of the ability

of local government to exercise its partial autonomy and to tailor its activities to local

circumstances.

The functions of elected local government

Elected local government is responsible for an extremely wide range of local public

services. Many of these are mundane (such as refuse collection) but undeniably

essential. Others, such as education, are equally important, but rather more complex

and expensive. Indeed school education is the single biggest element of local

government budgets. Increasingly, elected local authorities are sharing the provision

of services with a range of other private and voluntary sector organisations, using a

number of different contractual and partnership arrangements to try to ensure that

local needs are met. There are a number of different ways of classifying local

government functions. One way is to consider the different services that are provided

by the different tiers of local government. This classification has inevitably become

less clear-cut as the universal two-tier system described above has given way to a

hybrid system in which some areas now have single-tier (‘unitary’) local authorities.

Nevertheless, in the many areas which still have two main tiers there is some logic to

the distribution of functions between them:

Broadly, the functions are allocated between the two main tiers on the basis of

operational efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Thus it is both cheaper and more effective

to have responsibilities such as major planning, police and fire services operated over

fairly large areas. Similarly it was strongly argued by the Redcliffe-Maud Report and

the Wheatley Report [two major 1960s government reports on local government in

England and Scotland respectively] that the education service should be administered

over an area containing at least 200,000–250,000 people in order that such authorities

should have at their disposal ‘the range and calibre of staff, and the technical and

financial resources necessary for effective provision’ of the service. On the other

hand services such as allotments, public health and amenities can be effectively

administered over smaller areas, and are thus the responsibility of district authorities.

(Byrne 1992:59)

In the light of the government reports mentioned by Byrne, with their stress on

economies of scale in the provision of education, it is ironic that one of the major local

government reforms of the 1979–97 Conservative governments was to introduce ‘opted-

out’ schools in which some individual schools were given independence from local

government control (see p. 312). Moreover, the two-tier system was never organised

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GOVERNANCE

303

completely rationally. Factors such as tradition, democratic control and political influence

also affect which services are provided at which scale (Byrne 1992:59).

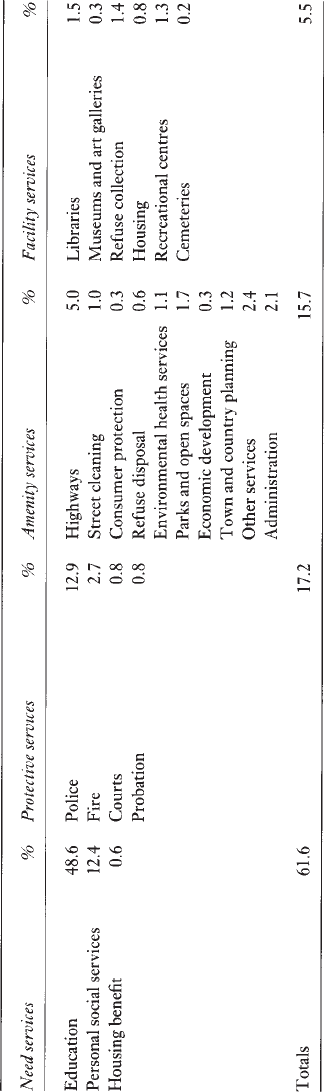

An alternative way of classifying services and functions is to recognise four categories

(Wilson and Game 1994):

1 Need services which are provided for all regardless of the ability to pay. They involve

redistribution of resources within the community.

2 Protective services provided for all to national standards.

3 Amenity services provided to locally determined standards to meet the needs of each

community.

4 Facility services that people can use if they wish.

Table 15.2 shows the various services provided by local government between these

four categories and their relative scale in financial terms for the financial year 1990/1 in

England and Wales. Between them, the three biggest services in financial terms, education,

social services and the police, account for very nearly three-quarters of all local government

expenditure. These services are also among the most controversial and important public

services in the UK, and it is therefore hardly surprising that local government has become

such a political hot potato.

Another key aspect of the political controversy that has surrounded local government

in recent years is its financing. A large proportion of the bill for local government is actually

met by central government. There is considerable logic to this arrangement. The geography

of wealth and income in the UK, as in most other countries, is very uneven. If local councils

had to raise all their resources locally there would be dramatic disparities between the ability

of councils to finance their activities and the demands placed on them by users of council

services. Simply put, wealthier areas are better able to pay for local government than poorer

areas, but poorer areas make much greater demands on local public services. Therefore, to

ensure that local government in poorer areas is able to function effectively a system of

redistribution is required. In the UK this is provided by central government in the form of

grants to local councils financed out of general national taxation. During the 1970s central

government provided 60–65 per cent of the financial resources for local government in the

form of two main types of grant: a general grant called the Rate Support Grant and special

grants for specific activities (Service Specific Grants). The remaining 35–40 per cent of the

cost of local government was met by local taxation.

Until 1989 in Scotland and 1990 in England and Wales, the local element of local

government finance was collected through a local property tax, the rates. Although not

directly related to the ability of people to pay, rates were correlated to some extent with

wealth, in so far as wealth was held in the form of land and property. On the other hand the

rates did have a number of disadvantages (Wilson and Game 1994:164–5) and they were

particularly unpopular with the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher. The Thatcher

government was in the vanguard of a wave of radical right-wing politics that emerged in

Europe and North America in the 1980s. Re-elected in 1979, the Conservatives in the UK

pursued economic policies inspired by the doctrines of monetarism developed by right-

wing economists such as Milton Friedman. One of the central planks of the monetarist

approach was a reduction in the economic and social role of the state in general and the

implementation of tight controls on public expenditure in particular. Greater controls over

Source: Welsh and Game (1994).

TABLE 15.2 Typology of local government services, showing percentage of total net expenditure on all local government services in 1990/1,

England and Wales

LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GOVERNANCE

305

local government finance had been put in place in 1976 by the then Labour government

and these were significantly strengthened by the Conservatives. Central government grants

to local government were constrained to the point where, by the end of the 1980s, they

met only 53 per cent of the costs of local government. Faced by these limits on the

contributions from the centre, many local authorities tried to make up the shortfall by

increasing income from rates on both residential and business properties. Because this

revenue also counted as public expenditure, the Conservative government, still seeking to

control such expenditure overall, began to restrict the rights of councils to raise revenue

through rate increases. Political conflicts over this programme of ‘rate-capping’, as it was

known, were among the bitterest-fought issues in local politics in recent years. However,

worse was to come.

The Conservatives adopted a number of strategies to try to rein in what they saw as

the excesses of local government (especially in councils controlled by the Labour Party). At

the forefront of these was the abolition of the rates system and its replacement with what the

government called the Community Charge, but which everyone else referred to as the ‘poll

tax’. Wilson and Game refer to the poll tax as ‘arguably the British government’s single

biggest policy disaster of the past 50 years’ (1994:132). The poll tax was based on a simple

principle: everyone in a given local area would pay the same, single, flat-rate charge as their

contribution to the cost of providing local services. The Conservatives hoped that this would

encourage voters to support parties (most notably the Conservative Party) that offered to cut

the charge, and thus the cost of local government, and therefore both weaken the Labour

Party’s control over many local councils and reduce public expenditure overall. In the event

the poll tax turned out to be a huge disaster for local government, for the Conservative Party

and for Margaret Thatcher personally, as it was a key factor in her replacement as party

leader and as Prime Minister by John Major.

Although most, if not all, taxes are unpopular, the main problem with the poll

tax was the enormous depth and breadth of its unpopularity. To all intents there was a

popular uprising against the tax, with many people refusing to pay it, national and

local anti-poll tax campaigns being established, many non-payers ending up in court

and even in gaol, and eventually a full-scale riot in central London. The extra cost to

central government in 1991/2 alone amounted to £7.5 billion—or £125 for every

man, woman and child in the country. In addition, the government also decided to

introduce a national business rate for business premises and to increase the proportion

of the cost of local government met by central government from 47 per cent in 1989/

90 to 54 per cent in 1992/3. The effect of these measures was to reduce the locally

determined proportion of local government finance to just 15 per cent, making it yet

more difficult for councils to decide for themselves how much money to raise and

what kinds of services to provide.

In April 1993 the poll tax was scrapped and replaced with a new tax called the council

tax that abandoned the per capita system of taxation on which the poll tax was based and

returned to property as the basis of local revenue generation. Now each household receives

a bill related to the value of the property. The vestige of the poll tax per capita principle that

remains is that single-person households gain a discount of 25 per cent. The amount that

councils can raise through local taxation remains tightly controlled by central government,

although the Labour government under Tony Blair, elected in May 1997, has recently relaxed

the constraints to a limited extent.