Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DAVID JONES

346

and ‘unacceptable’ risks (e.g. radiation from nuclear power stations), a perceptual division

that is made on the basis of freedom of choice (i.e. freely chosen risks are much more

acceptable than imposed risks) and the balance between perceived risks and benefits,

irrespective of the statistical probabilities of harm. The ongoing concerns over the reduction

in strength of the stratospheric ozone shield through the release of fluorocarbons is an

example of this phenomenon, for the postulated increases in ultra-violet ray induced skin

cancer are of a similar order to those resulting from two weeks’ sunbathing on the

Mediterranean coast, a risk which has yet to arouse the passions of a pressure group.

Geohazard impacts generally tend to be placed in the ‘unacceptable’ category by the majority

of UK citizens, because of the prevailing view that the organisational and technological

ability of an advanced society should be sufficient to minimise (control) the impact of

dynamic events in the physical environmental systems. This assessment illustrates the

widespread failure to comprehend that hazard losses are as much the result of society’s

vulnerability as nature’s violence.

Over the last seventy years the UK has suffered a surprising number of costly and

often visually impressive geohazard impacts: severe river flooding, particularly in the English

West Country (1952, 1968), the Scottish Moray area (1956, 1970), and Wales (1987), as

well as along the Rivers Eden, Severn, Thames and Trent; a number of severe droughts

which used to be ranked in terms of agricultural impact (i.e. 1976, 1934, 1944, 1938, 1974,

1964 and 1943) but more recently (1989, 1990, 1991, 1995, 1996) have been marked by

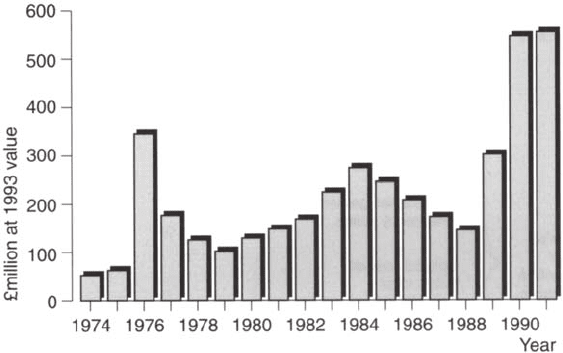

claims on insurance companies for subsidence damage to housing (Figure 17.4) and water-

supply shortages; blizzards and long snow-lie in the winters of 1939/40, 1941/2, 1946/7,

1950/1 (upland areas), 1954/5, 1962/3; 1969/70, 1978/9, 1985/6/7; wind damage, especially

in 1950 (eastern England), 1965 (Yorkshire), 1968 (Scotland, twenty killed), 1987 (southern

England, nineteen killed), 1990 (southern England), 1997 (Wales and Scotland) and 1998

(South West England), and frequent coastal storm damage. However, there have only been

a handful of events of sufficient magnitude to qualify as natural disasters. The eight most

FIGURE 17.4 The cost of insurance claims in respect of building ‘subsidence’ damage in the UK,

1974–91

Source: After Doornkamp (1995).

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

347

conspicuous are the Exmoor storm and resulting Lynmouth flood of 15 August 1952 (thirty-

four killed, total cost £9 million at currently prevailing prices, including damage to ninety

houses and 130 cars); the London smogs of 5–9 December 1952, 3–5 December 1957 and

3–7 December 1962, which caused the premature deaths of 12,000, 1,000 and 750 Londoners

respectively; the East Coast floods of the night of 31 January/ 1 February 1953, which

inundated 850 square kilometres, killing 307 people and causing estimated losses of £40

million, including 24,000 houses damaged; the Aberfan landslide disaster of 21 October

1966, when a spoil heap perched 150 metres above the South Wales colliery village suffered

slope failure, the resultant enormous flowslide consuming several houses and a school,

claiming 144 lives; the drought of 1975–6 which resulted in major losses to agriculture,

584,000 outdoor fires—some of which caused widespread destruction to forest and

heathland—and some £100 million damage to over 20,000 houses and buildings due to

subsidence, often because of extraction of moisture by tree roots; and most recently, the

intense storm of 16 October 1987 when high winds gusting to over 160 kph blew down

power-lines, telephone lines and 15 million trees, thereby virtually paralysing South East

England for 24 hours and causing costs of about £1,000 million at 1987 prices.

These events may appear insignificant when compared with the losses inflicted by

geohazards elsewhere on the globe (e.g. the 1988 Armenian earthquake) or the costs sustained

during wartime, or even with the UK road casualty figures (over 250,000 killed during the

last fifty years). Nevertheless, the scale of local devastation and/or the broader economic

ramifications are more than comparable with those resulting from the most severe

anthropogenic disasters such as the major mining accidents that punctuated the first half of

the century, the explosions at Flixborough (1974) and Platform ‘Piper Alpha’ (1988), the

Zeebrugge ferry tragedy (1988), the Marchioness riverboat disaster (1989), the Clapham

rail crash (1988) and the Lockerbie air disaster (1989), the 1981 inner-city riots, the

Hillsborough Stadium tragedy (1988) or the Docklands and Manchester bombs of 1996

and the Omagh bomb of 1998. Thus, the shock of these ‘natural disasters’, reinforced by

the general view that geohazards pose ‘unacceptable’ risks which should be minimised by

a technologically advanced society, stimulated investigations which resulted in management

decisions of considerable environmental significance. The 1952 smog led to the establishment

of the Beaver Committee whose Report (1954) identified the importance of smoke in

generating toxic and persistent urban fogs and directly resulted in the Clean Air Acts of

1956 and 1968. The East Coast Floods of 1953 led to the Waverley Committee Report

(1954) and investment in a wide variety of coastal protection measures, including the Thames

Barrier Project. The Aberfan disaster (1966) provided a major stimulus for the lowering and

reshaping of colliery spoil heaps, thereby leading to great decreases in visual intrusiveness

and spontaneous combustion. Increasing awareness of the overall importance of flooding

as one of the main cost-inducing hazards has resulted in the widespread implementation of

flood alleviation projects, albeit on a somewhat ad hoc and piecemeal basis.

Finally, the growing recognition of the significance of the climatic factor has resulted

in improvements in the accuracy of weather forecasts and attempts to achieve better ways

of communicating prognostications. The latter have involved developments in the media

(especially the graphics used in TV forecasts), the establishment of local forecasting offices,

and the preparation of forecasts for specific purposes, including such hazards as adverse

road conditions, severe weather, flooding and tidal surges. However, despite significant

advances, forecasting accuracy is still bedevilled by difficulties stemming from the complexity

DAVID JONES

348

of atmospheric processes and dynamics, and the fact that hazardous weather impacts can be

produced by phenomena of vastly differing scale and duration, ranging from a 2,500-

kilometre wide depression with frontal systems, to a small short-lived storm. Thus, the

attainment of the necessary precision with respect to scale, intensity, timing and location

are goals that are extremely difficult to achieve, and even the switch from analogue forecasting

techniques (using past patterns of weather activity as a guide to the future development of

synoptic situations) to quantitative computer-based numerical methods, combined with the

increased employment of satellite imagery and radar, have only recently improved the detail

of short-range (24-hour) and medium-range (1–7 day) forecasts. Despite the Meteorological

Office’s continuing optimism that the acquisition of new and evermore powerful computers,

together with new methods of analysis, will result in dramatic improvements in forecasting

accuracy, the failure to issue adequate warnings of severe events, such as the October 1987

storm, has revealed that many scientific, technical and organisational problems remain to

be resolved. As a consequence, ‘weather-sensitive’ industries such as transport, farming,

and building and construction, continue to suffer heavy costs through production loss, delay

and the inefficient utilisation of resources, while damage, destruction, injury and loss of life

will still be produced by the unexpected or unanticipated occurrence of infrequent high

magnitude events.

Despite technological developments in investigating, monitoring and limiting the

impact of geohazards, there is no evidence that hazard costs have declined over the past

century. In fact, the reverse is probably true, although, as with other advanced nations,

the situation is a complex one requiring information on the temporal changes in the levels

of hazard (i.e. magnitude, frequency and distribution) and the exposure of society to

harm (i.e. variations in the scale of losses likely to result from hazard impact as determined

by wealth and vulnerability). Unfortunately, few reliable data are available to inform

conclusions. Evidence for changing patterns of hazard occurrence over time is mainly

restricted to atmospheric parameters (e.g. wind speed, temperature extremes, rainfall and

drought) and flooding of certain rivers and coastal areas, supplemented by detailed studies

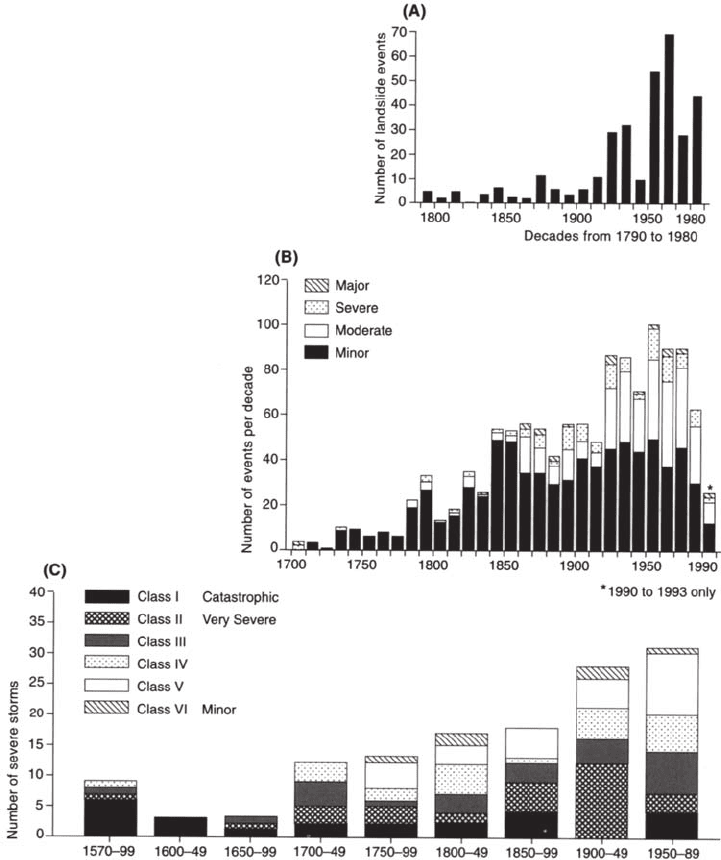

of certain phenomena such as debris slides and coastal landslides (Figure 17.5). In many

cases these do reveal increases in event occurrence through time which can be explained

by natural and quasi-natural changes, most especially the growing influence of human

activity in altering environmental conditions so as to actually increase the frequency and

intensity of certain hazardous events (e.g. landsliding, river floods, coastal inundations

because of sea-level rise due to global warming). However, this simple cause-effect

relationship must be treated with caution as there are also examples where threat is

diminishing due to human actions (e.g. reduced flooding in heavily regulated river systems,

urban smogs). More important still, it must be recognised that while contemporary records

may be relatively accurate, detailed and complete, the quality of past (historical)

information is usually markedly inferior and becomes increasingly patchy and vague

with increasing antiquity. This applies equally in the cases of field evidence and historical

archived data. Thus there is an inevitable in-built bias to the present which results in an

apparent incease in the frequency, and possibly magnitude, of recorded events with time,

thereby sustaining the view that geohazards are increasing in significance and severity

with time.

These features are clearly displayed in two recent surveys of hazard events. Lamb

(1991) investigated the occurrence of storms in north-west Europe over the period 1570–

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

349

FIGURE 17.5 Changing patterns of recorded hazard events over time: (A) the frequency of coastal

landsliding on the Isle of Wight, 1790–1980 (adapted from Brunsden 1995); (B) the frequency of

erosion, deposition and flooding events, 1700–1993 (after DoE 1995); (C) storms of different severity

class, 1570–1989 (after Lamb 1991)

DAVID JONES

350

1989 (Figure 17.5c) and revealed an apparent increase in storminess to the present with

three particularly stormy periods: prior to 1650, 1880–1900 and since 1950. Recorded storms

were divided into six categories on the basis of maximum wind speed, spatial extent and

duration, and the resulting categorisation reveals that the numbers of recorded intermediate

(classes III and IV) and smaller storms (classes V and VI) diminish rapidly with increasing

time before present (Figure 17.5c). Thus it is difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding

variations in the total number of storms over time, while the evidence for severe storms

(classes I and II) suggests fluctuating occurrence rather than a consistent trend.

A second survey of literature sources on erosion, deposition and flooding events

for the period 1700–1993 (DoE 1995) revealed a similar pattern (Figure 17.5b) with

generally increasing recorded occurrences to the 1950s since when they have been

approximately constant. While it is recognised that such reports only represent a sample

of actual events and that no great credence should be placed on the apparent increase

in number of events from 1700 to 1950, it is of interest to note that reports of ‘major

events’ do not appear until 1860 (apart from one report in the first decade of the

eighteenth century), since when they have been recorded in the majority of decades,

averaging one per decade this century. Reports of ‘severe events’ show a similar pattern

but appear earlier (in the 1790s apart from earlier reports in the 1700s and 1730s) and

are recorded more frequently in recent decades, averaging seven per decade this

century. Thus there appears to exist evidence in support of increasing scale of impacts

through time.

Data on the costs of impacts are few and largely restricted to recent decades, when the

increased involvement of the insurance industry in providing cover for natural perils has

resulted in improved hazard-loss accounting. Even so, loss assessments remain vague and

generalised, the true levels of impact remain difficult to estimate because of their complexity,

and many adverse consequences are intangibles which cannot be easily assessed or valued

in monetary terms (anxiety, ill-health, loss of irreplaceable ‘valued’ objects, reductions in

amenity value, etc.). Thus, there is little evidence for the true costs of hazard impacts, let

alone information on changing levels of impact through time.

Nevertheless, the results of the DoE study and analogues from elsewhere suggest

some general trends. A reduction in loss of life due to increased awareness, better forecasting

and warning procedures, well-developed emergency procedures and advances in medical

care, has been offset by rising economic losses, for four main reasons. First, population

growth and redistribution have caused pressure on land and resulted in the siting of an ever-

increasing range of hazard-sensitive activities in hazard-prone zones (e.g. floodplains—see

next section), despite the post-war growth of planning controls, thereby increasing the

likelihood and scale of potential impacts. Second, the growing complexity and

interdependence of commercial and industrial activity has meant that damage and disruption

at one location can have massive repercussions elsewhere. Third, technological development

sometimes leads to increased vulnerability, especially in the transport sector where the

significance of climatic hazards has increased with motorway construction, railway

electrification and air travel. And fourth, the evidence that human activity has increased the

magnitude and frequency of certain hazardous events (see earlier). The main question that

remains to be answered is whether or not the total cost of geohazards is rising faster or

slower than the rate of wealth creation. If it is the former, then geohazards are really a

growing problem.

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

351

River flooding

Despite the efforts of a succession of drainage and river management authorities and

agencies, flooding continues to be a feature of both the summer and winter months.

Prolonged heavy precipitation and/or rapid snowmelt are the main causes of high winter

discharges, often resulting in widespread flooding. Classic examples include the

catastrophic snowmelt floods of March 1947 which seriously affected much of Wales, the

South West, the Midlands and the Thames Valley, and resulted in prolonged inundation of

the Fenlands; the West Country and Welsh floods of 1960 and 1987; the widespread

flooding of 1968; the inundation of Chichester in January 1994; and the severe South

Midlands floods of 9–12 April 1998. Responses to this hazard have ranged across a variety

of structural and non-structural adjustments, including the deepening, widening,

straightening and regrading of channels (e.g. the Avon through Bath); channel maintenance;

the construction of levees and floodwalls along low-lying tidal reaches; the employment

of floodplain zonation so that the areas most liable to repeated inundation have land-uses

with low-loss potentials (e.g. recreation), with more vulnerable land-uses (e.g. housing)

placed on higher ground (i.e. ‘set back’); the construction of large flood-relief channels

to protect those urban areas particularly susceptible to flooding (e.g. Exeter, Spalding,

Walthamstow); the designation of floodable areas (washlands), sometimes in connection

with movable barriers, so as to protect vulnerable urban areas (e.g. Tonbridge), and the

building of reservoirs. While no dams have been constructed purely for flood control

purposes, there are several multi-purpose reservoirs with both water supply and floodwater

storage functions. The impact of these reservoirs on flooding depends on the available

storage capacity at the time of flood generation, and the volume of the flood wave. Research

has shown that the scale of reduction of flood discharges increases with increasing reservoir

size but diminishes with increasing size of floodwave. Thus, dams may reduce the volume

of frequent low-magnitude floods by up to 70 per cent but have little or no effect on

infrequent high-magnitude events. The application of combinations of adjustments to

rivers particularly prone to flooding, such as the Dee, Exe, Severn, Trent and the systems

draining the lowlands around the Wash and Humber, has resulted in considerable

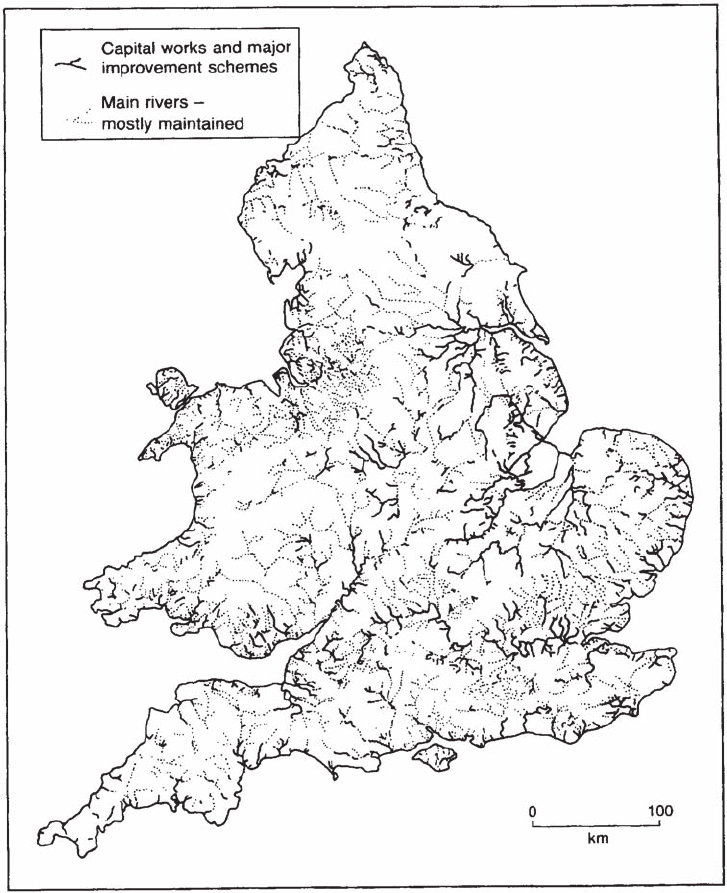

modifications to both their physical and discharge characteristics. Indeed, all main rivers

are regulated to varying degrees and the overwhelming proportion of the drainage network

has been modified due to 8,500 kilometres of capital works and major improvement

schemes, with a further 35,500 kilometres benefiting from periodic dredging and vegetation

control (Figure 17.6; Brookes and Gregory 1988).

Nevertheless, flooding continues to have a significant economic impact despite

investment in flood protection schemes, although the true costs are unknown because they

are spread throughout the economy, and published estimates are considered conservative.

The reasons for this significance are complex. First, structural measures have been unevenly

applied across the country. Second, the cost-effectiveness of protection measures diminishes

with increasing size of flood. Consequently, structures are rarely designed to protect against

discharges with recurrence intervals greater than a hundred years (i.e. flows likely to be

equalled or exceeded on average once in a hundred years). Thus, there will always be

floods whose magnitude exceeds the capacity of the provided protection measures. Third, a

significant proportion of floodplain inhabitants and planners still have poor perception of

flood hazard, with many of the former considering that the provision of any structural

DAVID JONES

352

protection measures guarantees safety (the levee syndrome). Last, and probably most

important, pressures on space have resulted in the continued development of floodplains

due to an estimated 90,000 planning applications a year, many of which are approved despite

the flood threat, so that zonation policies have only been poorly applied. Prime examples of

the consequences are the Trent at Nottingham, where there was severe community disruption

FIGURE 17.6 River channelisation in England and Wales

Source: After Brookes et al. (1983).

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

353

in 1990, and the Thames near Maidenhead which has proved so floodprone as to require an

£80 million defence scheme, equivalent to £14,000 per house protected. All of these factors

have tended to counterbalance the benefits stemming from improved monitoring, better

forecasts and warning systems, and the increasing use of predictive computer-based models.

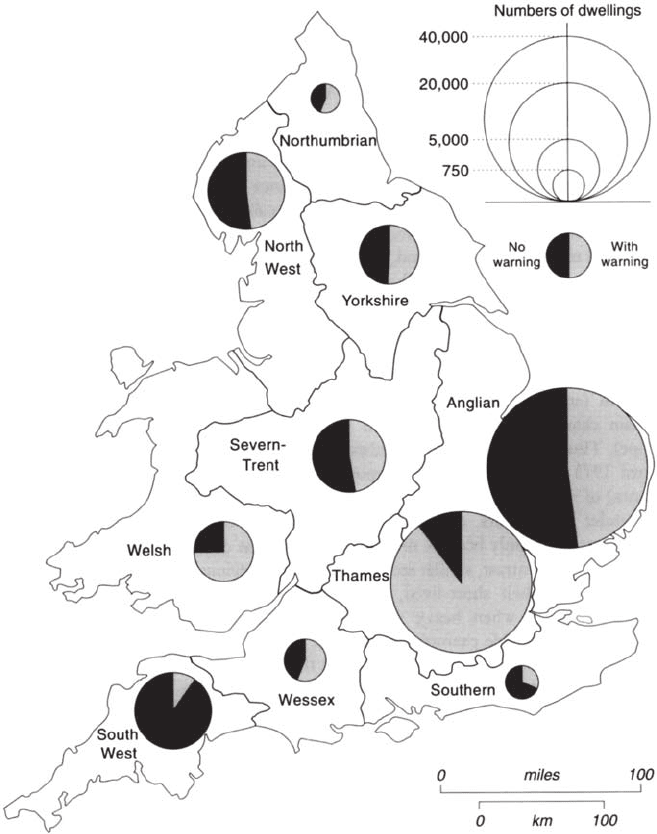

Indeed, up to 450,000 people are thought to live in areas liable to flooding (Figure 17.7)

with a recurrence interval of 50–100 years, many without the benefit of a flood-warning

FIGURE 17.7 The number of dwellings in England and Wales in the mid-1980s within zones affected

by 1:50 to 1:100 year flood levels

Source: Redrawn from Penning-Rowsell and Handmer (1988).

DAVID JONES

354

service. Loss-bearing and dependence on relief funds are still common responses to floods,

although the relatively recent increased use of flood insurance cover has improved the

situation. Uncertainty regarding the magnitude-frequency characteristics of geophysical

events has always caused insurance companies to be reluctant to provide cover for natural

perils— especially flooding, where loss claims can reach catastrophic levels. Thus, while

storm damage cover has been available since 1929, it was only after the widespread 1960

floods that combined pressure from the then Ministry of Housing and Local Government

and the building societies overcame the reluctance of the insurance companies and resulted

in the availability of flood insurance cover. However, uptake remains patchy and many

people still suffer great losses from unexpected events, such as in Chichester in 1994.

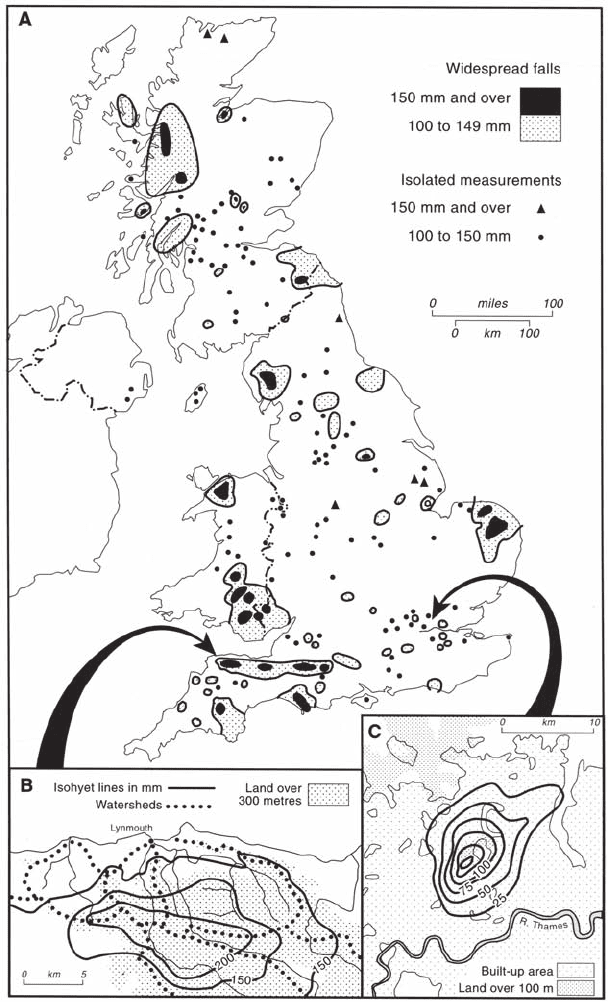

The second main type of river flood, the flash flood, can result from dam failure but

is more characteristic of small, steep catchments where rapid run-off is caused by intense

precipitation, usually during the summer months. In fact, summer storms often result in

over 100 mm of rainfall in a few hours over a localised area (Figure 17.8) and account for

the surprising fact that August has the worst record for catastrophic floods, closely followed

by July. The magnitude of the resultant flooding is dependent on a number of variables

relating to precipitation (area, duration, intensity, total), antecedent moisture conditions,

and drainage basin characteristics (geology, land use, drainage network shape, topography,

channel slope). Thus, the most dramatic rainstorm in recent history, the Hampstead storm

of 14 August 1975 (Figure 17.8) which deposited an estimated 2,000 million gallons (8

million tonnes) of water (up to 170 mm of rain) over an extremely localised area of North

London in under three hours, only caused local problems of surface ponding and the

flooding of basements, mainly because much of the water was quickly transported away

by stormwater sewers. By contrast, similar storms on small impervious clay-floored

catchments can result in severe, albeit short-lived, flooding. However, the most spectacular

and destructive floods occur when heavy rains fall on upland regions with short, steep

catchments. The most notable examples include the Moray (NE Scotland) floods of 1956

and 1970, the Mendip floods of 1931 and 1968, and the Somerset and Devonshire floods

of 1952 and 1968. The last mentioned includes the catastrophic Lynmouth floods of 15–

16 August 1952, when up to 300 mm of rain fell on Exmoor in 24 hours (Figure 17.8),

resulting in such feats of erosion by the diminutive River Lyn that fallen trees and boulders

created temporary dams behind bridges, the breaching of which greatly intensified the

devastating nature of the floods downstream. Such extreme floods are difficult to forecast

because the storms that create them are usually the product of localised topographic or

urban conditions. The short response times of the rivers (basin lag) means that forecasting

is problematic and that warnings either cannot be given in time or fail to reach the entire

population at risk, and emergency services are often hampered by inadequate preparation

time. Planning for such events is also impracticable because their rarity (long recurrence

intervals) means that there are few available comparable records to use as a guide, while

the structural adjustments required to cope with potentially very high magnitude floods

are prohibitively expensive and totally non-cost-effective. For example, the Lynmouth

flood had a calculated recurrence interval of 50,000 years, due to the diminutive River

Lyn having swollen to a size equivalent to the Thames in spate at Teddington and in so

doing moved more than 100,000 tonnes of boulders, some weighing up to 7.5 tonnes.

Such catastrophic events will continue to happen through the chance combination of

factors and, as the past record of intense storms shows (Figure 17.8), could occur virtually

HUMAN OCCUPANCE AND THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

355

FIGURE 17.8 Rainstorm hazard in the UK: (A) distribution of daily rainfalls in excess of 100 mm,

1863–1960; (B) isohyets of Exmoor storm, 15 August 1952; (C) isohyets of Hampstead storm, 14

August 1975