Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

JAMIE PECK AND ADAM TICKELL

156

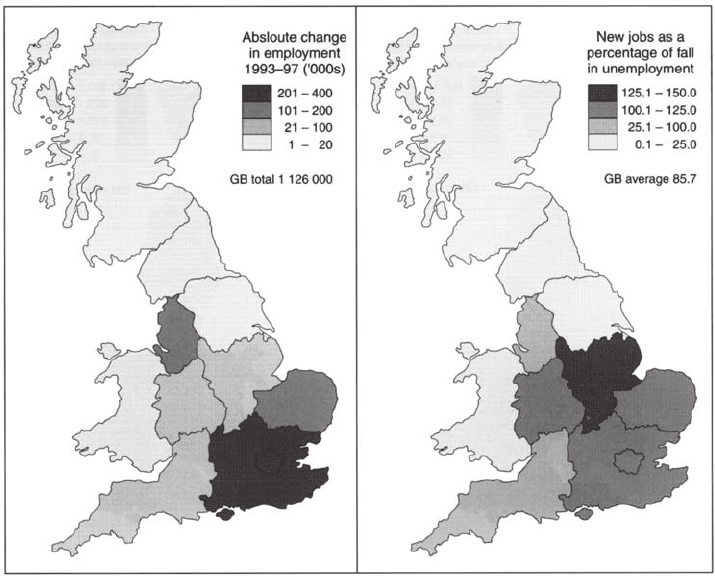

national recovery. First of all, fully 63 per cent of the new jobs created in the UK between

1993 and 1997 were part-time. In Scotland, Wales, the North and Yorkshire and Humberside,

full-time employment continued to contract during a period widely portrayed as a ‘boom’,

so all net new job growth in these regions was part-time. Even in London, 82 per cent of

post-recession employment growth has been in part-time jobs.

Second, recorded unemployment has been falling at a faster rate than job growth.

There is evidence in some regions of a significant ‘job gap’ between the off-flow from

unemployment and the creation of new jobs. While falling unemployment captured the

headlines, job growth in many parts of the country remained sluggish. In Scotland, for

example, less than 4,000 net new jobs were created in the ‘recovery’ period 1993–7—

all of which, as we have seen, were part-time—yet registered unemployment fell by

85,000. This means that, for every 100 people leaving the unemployment register in

Scotland since the early 1990s recession, only 4.5 net new jobs were being created.

This phenomenon is not restricted to Scotland. In fact, Yorkshire and Humberside, Wales,

the North and the North West also exhibit a significant jobs gap, while in contrast, the

‘core’ regions have witnessed employment growth at a faster rate than the dole queues

have been shrinking.

This suggests that regional labour market disparities were, if anything, widening during

the mid-1990s recovery, which has done little to redress the structural weaknesses of the

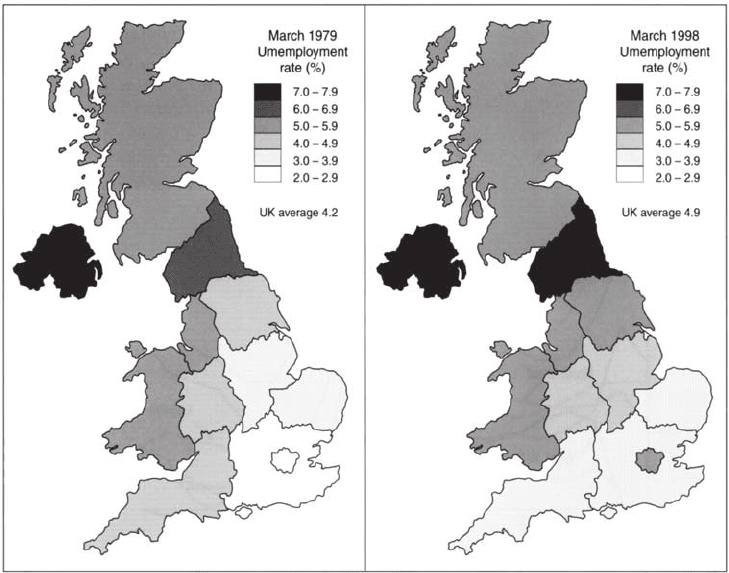

FIGURE 8.4 Unemployment rates by region, 1979 and 1998

Sources: ONS; NOMIS.

LABOUR MARKETS

157

UK’s lagging regional economies. On the contrary, it would seem that the increasingly

strict benefit regime, reinforced by the introduction of the Jobseekers’ Allowance (JSA) in

1996, has been acting to ‘de-register’ unemployed people in depressed regions in the absence

of real employment opportunities (see Peck and Tickell 1997). This underlines the need for

broader measures of the ‘real’ level of unemployment than is suggested by claimant statistics.

These might take account of those on government training and welfare-to-work schemes,

those ‘involuntarily’ working in temporary or part-time jobs, the unregistered unemployed

and others discouraged from seeking work by the non-availability of jobs. More nuanced

analyses of the wider levels of non- and underemployment in regional and local labour

markets suggest that the ‘real’ unemployment rate is significantly higher across the board

than the claimant count, but is substantially higher in precisely those areas which have

suffered deep and persistent problems of economic decline and high registered un-

employment—the northern and western regions in general, and northern cities and coalfield

areas in particular (see Green 1996; Green and Hasluck 1998). This means that official

unemployment statistics—including the revised, broader count adopted in 1998—tend to

understate levels of local and regional labour market inequality in the UK. As Green and

Hasluck (1998:556) comment, ‘there appear to be reinforcing feedbacks between non-

employment, underemployment, insecure employment, and a lack of investment in human

FIGURE 8.5 The geography of economic ‘recovery’, 1993–7

Sources: ONS; NOMIS.

JAMIE PECK AND ADAM TICKELL

158

capital’ which lead to the entrenchment of regional labour market disadvantage and to the

perpetuation of ‘cycles of high unemployment’.

While an expanding labour market may be serving to ‘pull’ people from the

unemployment register in the more buoyant areas of the country, there is no such demand-

side pull in the depressed regions. Here, claimants are experiencing a concerted ‘push’

from unemployment in the context of weak or even negative employment growth,

producing increased flows into economic inactivity, onto long-term sickness benefits,

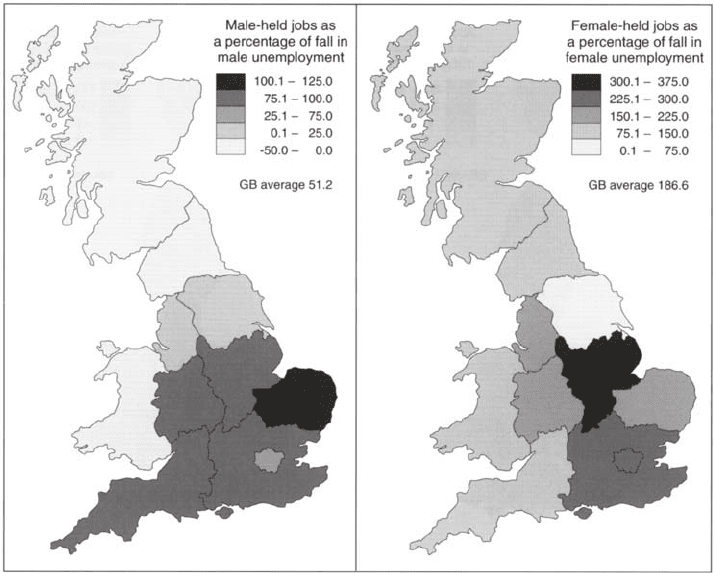

and doubtless also into the cash-and-crime economy. As Figure 8.6 shows, regional job

gaps tend to be much wider for men than for women, reflecting the continued contraction

of traditionally male-dominated employment in manufacturing and the relative buoyancy

of service labour markets. Across the country as a whole, male unemployment fell by

981,000 between 1993 and 1997, but total male employment only rose by 502,000

during the same time period. Meanwhile, female unemployment fell by 334,000, while

women’s employment grew by 624,000. This represents a continuation of trends

established in the 1980s, when 1.3 million male-held, full-time jobs were lost and when

new employment opportunities were mostly part-time (71 per cent) and filled by women

(83 per cent) (Dunford 1997). These developments underline the fact that processes of

labour market restructuring in the UK are both geographically differentiated and strongly

gendered.

FIGURE 8.6 The job gap by gender, 1993–7

Sources: ONS; NOMIS.

LABOUR MARKETS

159

Geographies of labour market ‘deregulation’

Punctuated by two major recessions, the last two decades in the UK labour market have

been characterised by low growth, widening social and regional inequalities, and a fraught

transition from male-dominated manufacturing employment to a strongly services-oriented

economy heavily reliant on part-time and female employment. Even at the peak of the

business cycle, problems of low pay, unemployment, social exclusion and inadequate

investment remain endemic, leading Dunford (1997) and others to suggest that the UK

labour market has shifted to a new, low-employment/low-productivity ‘equilibrium’. Dunford

argues that this offers little long-term job potential or scope for sustainable economic

development, due fundamentally to key weaknesses in the wider regulatory framework in

which the labour market is embedded. In contrast to the Keynesian-welfarist order prevalent

in the UK from the Second World War through to the mid-1970s, under which there was full

male employment, rising incomes and productivity, expansive welfare provision and regional

economic convergence, the low-employment/low-productivity ‘equilibrium’ of the 1980s

and 1990s has been predicated on the deregulation of labour markets, polarising incomes,

persistently high ‘real’ levels of unemployment and regional economic divergence.

While debate continues over whether the current alignment of ‘flexible’ labour markets

and ‘deregulationist’ policies is a sustainable one (see Peck and Tickell 1994), it is clear that

the old order of Keynesian-welfarism has fallen under concerted political attack, and may

indeed be in permanent retreat. According to Jessop (1994), the Keynesian welfare state

served to regulate and underwrite the post-war growth pattern in four ways: first, relative

macro-economic stability was secured though labour market policies, the management of

aggregate demand and the regulation of industrial relations; second, mass production and

mass consumption—which were crucial to maintaining the virtuous cycle of mutually

reinforcing growth in investment, productivity, incomes, demand and profit —were

underpinned by a range of measures, from competition policy to infrastructure development

and housing policies; third, consensus support was constructed around a programme of full

employment and universal welfare; and fourth, social and welfare service needs were met

through an expansive local state. In the British case, Kavanagh (1987) argues that the post-

war political-economic settlement exhibited six key institutional features:

¿ full employment: both Labour and the Conservatives accepted the doctrine of full (male)

employment as a fundamental policy goal; male unemployment rarely exceeded 3 per

cent from the late 1940s to the early 1970s;

¿ the mixed economy: extensive state intervention in the economy garnered bipartisan

support, as nationalised industries (such as steel, coal, gas, electricity and rail) involved

the state directly in the production process and played a key role in underpinning weaker

regional economies;

¿ interventionist government: British governments played an active role in the regulation

of the domestic economy through the Keynesian techniques of demand management

and the pursuit of industrial and labour market policies;

¿ welfare: both major parties accepted the need for extensive welfare provisions— ranging

from unemployment and sickness benefits to state pensions, from the NHS to public

housing—which were however predicated on healthy economic growth and high levels

of male employment;

JAMIE PECK AND ADAM TICKELL

160

¿ corporatism: the trade unions were incorporated into the post-war political settlement,

when along with business representatives they were afforded access to a range of decision-

making and advisory bodies in areas like industrial training and labour market planning;

¿ technocracy: this was an era in which the government knew best—the dominant ethos

underpinning the state’s activist and interventionist approach to the regulation of economic

and social life combined scientific management techniques with bureaucratic rationality

and paternalism.

Geographically, the Keynesian-welfarist pattern of regulation was also distinctive

in a number of ways (Martin and Sunley 1997). First, the domestic or national economy

was privileged as the most important scale of regulation, domestic policies requiring a

degree of ‘insulation’ from international economic forces. Second, the nation-state acted

as the dominant agent of regulation, utilising centralised powers of regulation, control

and intervention to manage the domestic economy; in particular to underpin high levels

of aggregate demand and employment. Third, extensive state intervention and growing

public expenditure led to spatial integration, as a standardised ‘floor’ of social welfare

entitlements and infrastructure provisions was gradually established across all parts of

the country. Fourth, these developments had the effect of countering spatial unevenness

in wealth and welfare, as a range of measures including progressive tax systems, regional

policies and needs-based benefits brought about income transfers from rich to poor

areas.

The Keynesian-welfarist pattern of regulation went into crisis in the 1970s,

following a slowdown in economic growth and an unprecedented rise in both

unemployment and inflation (‘stagflation’). In the UK, where these problems were

especially acute, the rise of Thatcherism in the 1980s heralded a far-reaching shift in

the prevailing political-economic orthodoxy which favoured market forces over state

intervention, individualism over collectivism, privatisation over nationalisation,

decentralised over centralised policies, and entrepreneurial zeal over corporatist

bargaining. This new philosophy represented both a critique of, and a putative alternative

to, the discredited welfare-statist orthodoxy.

[T]he inability of the Keynesian state to resolve supply-side economic rigidities

as evidenced by inflation, unemployment and ‘lame-duck’ industries, its endemic

‘fiscal crisis’ of rising costs of social welfare and public resistance to higher

taxation, and its inability to control the demands of organized labour had

culminated by the end of the 1970s in a crisis both of economic management and

social legitimation. In addition, the very bases of national Keynesian

interventionism have, it is widely argued, been completely undermined by changes

in the international economic context, in particular the collapse of the international

regulatory regime (Bretton Woods) that underpinned financial stability and, more

recently, the ‘globalization’ of economic activities and economic spaces…[A]

political response…epitomized by Thatcherism in the UK and Reaganism in the

USA…has been to roll back national systems of regulation, intervention and

welfare support in an attempt to give national economies the ‘flexibility’ needed

to compete in today’s global markets.

(Martin and Sunley 1997:281)

LABOUR MARKETS

161

In this context, it should come as no surprise that the labour market has been one of the

central terrains of struggle and reform (see Robertson 1986). Mrs Thatcher’s first

Conservative government was determined to reduce the power and influence of the trade

unions, having been elected in the aftermath of the ‘Winter of Discontent’, a wave of strikes

triggered by the breakdown of Labour’s incomes policy. Priorities for the Conservatives

were a package of industrial relations reforms, designed to restore the ‘right to manage’,

and the installation of a stringent regime of macro-economic management—‘monetarism’

— intended to restore the international competitiveness of the British economy.

‘Deregulation’ and ‘flexibility’ would be the new rallying calls. Yet while the Conservatives

spoke of liberating market forces, decentralising power and removing the ‘dead hand’ of

government interference in the marketplace, the irony was that their policy programme

would require new forms of state intervention, typically backed up by the firm hand of

central authority, an approach succinctly summarised by Andrew Gamble’s (1988) phrase,

‘the free economy and the strong state’. So while the Conservatives’ programme of labour

market reforms was far-reaching and in many ways radically transformative, it was also in

some senses fragile and contradictory (see Peck and Jones 1995).

In order to illustrate this point, we comment briefly here on four key policy fields

amongst the barrage of labour market reforms introduced by the Conservatives, highlighting

in each case their associated spatial consequences: macro-economic policy; unemployment

and welfare; training and workplace preparation; and, finally, industrial relations and trade

unions. When the Conservatives were elected in 1979 they adopted a monetarist macro-

economic policy in the belief that one of the UK’s main problems was the persistence of

high inflation which, they believed, was caused by having too much money in circulation.

In order to reduce the money supply, the government raised interest rates. As the impact of

this was to raise the value of sterling, British manufacturers were faced with a situation of

higher borrowing costs and an exchange rate which simultaneously made their exports

more expensive while reducing the cost of imports. The first two years of monetarist policy

saw output fall by 6 per cent—almost exclusively in manufacturing—while the supply of

money actually rose by 60 per cent in the first three years (Cairncross 1994). Although

formally, monetarism was spatially neutral, the heavy concentration of manufacturing

industry in northern and western regions led to disproportionate job loss in those areas.

In 1982 monetarist economics were quietly dropped and, during the 1980s,

Conservative economic policy was more concerned with reducing the government’s role in

economic life through policies of tax cuts and the privatisation of publicly owned companies,

yielding strongly disproportionate benefits to the South East (Hamnett 1997; Tickell 1998).

Consumer spending mushroomed as tax cuts and the proceeds from privatisation share

issues found their way into luxury goods and booming house prices. The impact was, yet

again, spatially uneven: the booming economy of the mid- and late 1980s was almost

exclusively concentrated in the southern regions of England, but the boom was of such a

magnitude that it placed inflationary pressures on the economy as a whole. The government

responded by progressively raising interest rates. While it did succeed in slowing the southern

economy, it did so by precipitating a deep recession for the UK as a whole, destroying the

late and fragile economic recovery of the North and West.

The recovery from the early 1990s recession then followed what had become a

somewhat familiar pattern: growth in the South was fastest and strongest whilst regions

elsewhere were slow to emerge from their structural economic malaise. The election of a

JAMIE PECK AND ADAM TICKELL

162

Labour government in 1997 proved something of a false dawn for those in the peripheral

regions who had felt that Conservative policies had—deliberately or not—disadvantaged

them. The new Labour government handed responsibility for setting interest rates to the

Bank of England, entrusting the Bank with the maintenance of persistently low levels of

inflation—a policy better suited to the inflation-prone South than the deflated North. The

re-emergence of inflationary pressures in the south of England during the late 1990s led the

Bank of England to raise interest rates numerous times from May 1997, such that the

manufacturing sector had again slid in recession by 1998. While there may be a common

perception that the peripheral parts of the UK are a drag on the national economy, an

alternative perspective would highlight the destructive nature of macro-economic policies

which create unsustainable booms in core regions of the country while barely ameliorating

long-run decline elsewhere.

Turning to unemployment and welfare, the Conservatives’ approach was to gradually

tighten the benefits regime so as to create stronger ‘incentives to work’. The real value of

benefits relative to average wages was allowed to fall, while a range of measures were

introduced to restrict eligibility for benefits and to push those deemed ‘employable’ into

work. For example, benefit eligibility for all 16- and 17-year-olds was removed in 1988

(with the effect of making the Youth Training Scheme (YT) effectively compulsory), while

unemployed adults were—under the post-1986 Restart programme—required to take specific

steps to find work (including attending work and social skills courses) or risk losing benefits.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, a series of programmes for school-leavers and unemployed

adults, such as YT, Employment Training and Training for Work, came to assume considerable

importance, providing as they did an ‘institutionalised labour market’ in those depressed

regions and inner-city areas where ‘real’ jobs remained in short supply. But these programmes

differed from the job creation measures of the 1970s in that they were explicitly ‘designed

to work with the grain of the market, so as to encourage more realistic wage levels and more

flexible working patterns’ (Treasury 1984:3). Allowances on all such schemes were set

deliberately below market levels, in order to encourage more ‘realistic’ (i.e. lower) wages at

the bottom end of the labour market. The pressure to enter low-wage work was intensified

with the introduction of the JSA regime in 1996, which renders unemployment benefits

conditional on active jobsearch, thereby compelling the unemployed to move into whatever

jobs may be available locally.

In the final years of John Major’s administration, the Conservatives also began to

experiment with local ‘workfare’ programmes, under which the unemployed are required

to carry out environmental and other work in order to ‘earn’ their benefits. The general

effect of such measures, alongside the stricter benefits regime and the expansion of ‘active’

labour market programmes, was to drive down both the ‘reservation wages’ of the

unemployed (the pay level at which claimants were prepared to accept a job) and the overall

level of registered unemployment. Meanwhile, various forms of ‘hidden’ unemployment—

in the form of inactivity, early retirement, long-term sickness—increased significantly,

especially in depressed areas. One way of evaluating the impact of such labour market

reforms is to look at the changing components of household income. In 1978/9, 72 per cent

of household incomes in the UK came from salaries and wages. After seventeen years of

labour market reform this had fallen to 64 per cent—with falls of similar magnitude in

every region except Northern Ireland. Although part of the explanation for such changes is

that Britain has an ageing population relying on investment incomes and government pensions

LABOUR MARKETS

163

in retirement, people without jobs rely on the social security system to pay for their basic

human needs— and it is no coincidence that the regions with the highest reliance on social

security are also those with the highest levels of visible and hidden unemployment.

A significant feature of Conservative labour market policy, particularly from the late

1980s onwards, was the way in which benefit reforms and provision for the unemployed

were combined together with restructured systems of training and workplace preparation.

The key moment here was the introduction of Training and Enterprise Councils (TECs) in

1988 in the context of a profound deregulation of the system of industrial training. The

TECs are locally based, business-led bodies which operate on contract to central government

under a wide remit embracing increasing the level of training activity, delivering market-

relevant programmes for unemployed people and school-leavers, and stimulating

entrepreneurship and business development in local economies. The network of localised

TECs took over the key functions of the Manpower Services Commission (MSC), a tripartite

body established in the 1970s to involve trade unions and business representatives, together

with government, in the process of strategic labour market planning. Deeply suspicious of

such corporatist organisations, the Conservatives had nevertheless used the MSC during the

early 1980s to deliver large-scale training and ‘make-work’ for the unemployed. In fact, the

MSC became a key agency in the implementation of the government’s programme of

neoliberal labour market reform (Peck and Jones 1995). According to King, the Conservatives

used the TECs to effect

a shift from a national tripartite regime to a local, employer-dominated neoliberal

training regime…[During the 1980s, the British government] ended the legacies of

the postwar Keynesian framework, particularly tripartism, which had informed training

policy, and substituted it with a neoliberal one, dominated by employers’ interests

and measures to counteract labour market disincentives.

(King 1993:214–15)

In fact, while the TECs came to epitomise the Thatcherite approach to labour market reform,

they were also quick to demonstrate its shortcomings and contradictions. Designed in

anticipation of a tightening labour market, the TECs were rolled out into the hostile climate

of the early 1990s recession, and as a result were forced to take on the role of managers of

local programmes for the unemployed. They drove down the costs of such programmes and

tailored them, where possible, to meet local labour market needs, but in the process revealed

that they lacked the means to bring about significant increases in the level of private

investment in training. Prior to the TECs, employers in most key sectors of the economy

had been required by law to support the training of new recruits through a levy-grant system,

administered by a network of Industry Training Boards (ITBs). This system was wound up

on the introduction of TECs, whose remit was to encourage employers voluntarily to invest

in training. In fact, training levels declined under this free-market regime, leaving behind it

only the rump of low-level training programmes for young people and the unemployed,

combined with the patchy and generally inadequate provisions of private employers (see

Jones 1999). No longer underwritten by the levy-grant scheme, which through a regime of

employer contributions and incentives guaranteed minimum levels of training provision,

the British training system has degenerated into an uneven, low-skills, low-investment

equilibrium.

JAMIE PECK AND ADAM TICKELL

164

Finally, perhaps the most far-reaching and controversial of the Conservatives’

labour market reforms have been concerned with industrial relations and trade unions.

The dominant pattern of economic restructuring in the UK had been undermining the

bases of trade union strength for some time: the unions’ organisational strength lay in

manufacturing industry, especially in large plants, and membership was skewed

towards male, full-time workers. This meant that the heartlands of traditional

manufacturing industry were also the heartlands of British trade unionism, and while

union support in these northern and western parts of the country has remained in

many ways resilient, it has undeniably been eroded by the shift towards services and

contingent work (Martin et al. 1996). Equally significant, however, was the frontal

attack on the unions launched by the Conservatives in the early 1980s, when a

legislative programme designed specifically to curb the political and bargaining power

of the unions, coupled with a series of major confrontations with public-sector unions,

served to rewrite the rules of the British industrial relations system. For the unions,

this reached its nadir with the defeat of the miners in the strike of 1984–5, during

which a divide-and-rule strategy had exposed damaging cleavages between the

relatively conservative Nottinghamshire miners and their rather more militant fellow

workers in Yorkshire, Scotland, Wales and elsewhere. The Conservatives’ organised

and uncompromising approach to the strike led to the effective destruction of the

vanguard union, the National Union of Mineworkers (see Sunley 1990), and was to

play a key role in transforming the industrial relations climate across the economy as

a whole. Levels of industrial action fell dramatically, and have remained low, while

single-union and no-strike deals became increasingly commonplace, perhaps most

symbolically in many of the Japanese-owned manufacturing plants which began to

locate in the old union heartlands of Scotland, Wales and the North of England

(Munday et al. 1995; see also Durand and Stewart 1998).

As the extensive policy interventions of the 1980s illustrate, ‘deregulated’ labour

markets are not free from government involvement. It follows that the labour market

trends described earlier in this chapter are not necessarily ‘natural’ or inevitable, but

instead are variously moulded and channelled by government policy. The ‘flexible’ labour

markets of the late 1990s bear the imprint of government policy and regulation in many

ways just as vividly as did their ‘rigid’ predecessors of the early 1970s (see Rubery 1994).

What has changed—and undeniably there has been significant change—is the nature,

goals and premises of policy itself, as quite different political choices are now being

made about appropriate and desirable forms of labour market development. Flexible labour

markets do not just ‘happen’. Rather, they have been actively cultivated by successive

governments intent on extending the scope of managerial prerogative, disorganising the

labour movement, retrenching welfare provisions and individualising employment

relations.

Conclusion: New Labour and the labour market

When Labour came to power in 1997 it inherited a legacy of flexibly deregulated

labour markets, wide social and economic inequalities, and high but falling

unemployment. While Labour criticised some of the more pernicious effects of

Conservative policies, it would soon be clear that the Blair government’s intention

LABOUR MARKETS

165

was to work within, rather than against, the neoliberal regulatory framework

established in the 1980s and 1990s. The Conservatives’ trade union and social security

legislation would not be repealed, the privatisation programme would not be reversed,

market-oriented policies in areas like training would be retained, as would both the

deflationary macro-economic posture and tough stance on public expenditure. The

Labour government is building on the foundations laid by previous Conservative

administrations, but has also strongly advocated more activist and interventionist

policies in a number of areas. Chief amongst these are welfare-to-work, where the £5

billion New Deal programme represents the Blair government’s largest new public-

spending commitment; social protection, where individual workplace and social rights

have been extended; and wage-setting, where a minimum wage has been introduced

for the first time in the nation’s history. As Peter Mandelson explained on the occasion

of the launch of Labour’s Social Exclusion Unit:

flexibility in its own right is not enough to promote economic competitiveness. It is

the job of government to play its part in guaranteeing ‘flexibility plus’ —plus higher

skills and higher standards in our schools and colleges; plus partnership with business

to raise investment in infrastructure, science and research and to back small firms;

plus an imaginative welfare-to-work programme to put the long-term unemployed

back to work; plus minimum standards of fair treatment at the workplace; plus new

leadership in Europe in place of drift and disengagement from our largest markets.

This is the heart of where New Labour differs from both the limitations of new right

economics and the Old Labour agenda of crude state intervention in industry and

indiscriminate ‘tax and spend’.

(Mandelson 1997:17)

It would be inaccurate, however, to portray Labour’s approach to the labour market as

no more than ‘business as usual’. In comparison to the Conservative years, there have

been changes in substance as well as in emphasis. Chancellor Gordon Brown’s early

Budgets were gently but persistently redistributional, while active steps have been

taken—through the reform of taxes and benefits and through the introduction of a

national minimum wage —to ensure that ‘work pays’ for welfare recipients and those

in the lower reaches of the job market. A series of spatially targeted policies, such as

the Employment Zones introduced in 1998, are providing focused help with local

employment initiatives in areas of high unemployment. Couched in the language

of ‘rights and responsibilities’, Labour’s approach to tackling unemployment marries

the carrot with the stick: the unemployed are offered new opportunities for education

and training, subsidised employment and community work but in turn are obliged to

take these up; under strict new rules, those refusing to take up places on the New Deal

programme for the unemployed have their benefits withheld. Labour has proved more

willing than the Conservatives to utilise ‘active’ labour market policies, particularly in

the area of measures to tackle social exclusion. Active policies seek to work with the

grain of the market to bring about higher and more sustainable levels of waged

employment, and to reduce ‘dependency’ on welfare. Their adoption represents a marked

change from the Conservative approach, which privileged narrow, market-based

approaches to labour market policy, with little or no explicit role for progressive social