Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DAVID SADLER

146

BOX 7.2 The competition for large inward investment projects

It is important not to overstate the significance of large inward investment projects.

The bulk of public assistance to inward investors is allocated to smaller projects and

to reinvestment by existing firms. On the other hand the competition for large projects

has become increasingly intense and public, and in such cases it is possible that the

amount of financial assistance made available by one location as opposed to another

could be decisive. In the mid-1990s the UK secured a number of very substantial

projects within the electronics industry involving competition between potential sites

within Europe. Some of the consequences are explored below.

In 1995 the German electronics firm Siemens selected North Tyneside in

north-east England from a shortlist of six locations for a new £1.2 billion

semiconductor plant, which was estimated eventually to create 2,000 jobs. The

following year a semi-public contest between locations within the UK—

particularly Wales and Scotland —culminated in a decision by South Korean

firm LG to establish its £1.7 billion combined semiconductor and consumer

electronics complex at Newport in South Wales. This was hailed as the biggest

inward investment project in Europe, one that would lead eventually to the

creation of 6,000 jobs. Whilst details of the public subsidy were not officially

released, it was believed to be in the order of £200–250 million (the largest ever

offered to an inward investor in the UK), equivalent to about £30–40,000 per

job created. Just months later, another South Korean firm—Hyundai—announced

that it too had favoured the UK, choosing to build its new £1 billion

semiconductor plant at Dunfermline in Scotland. This was expected to create

1,000 jobs, with a possible second phase involving a further investment of £1.4

billion and an additional 1,000 jobs.

5

Amidst the delight at these inward investment successes, there were several

notes of concern. The LG case in particular prompted expressions of dismay

from promotional agencies within England, which argued that they faced unfair

competition from the Scottish and Welsh Development Agencies, with their larger

budgets and greater control of a range of government activities (see p. 145).

The cost-per-job created was high even by comparison with the subsidies awarded

to other large inward investors, let alone those given to smaller firms. The low

local content of existing semiconductor manufacturers in the UK suggested that

the spin-off impacts would be limited. The extent to which the advanced capital

equipment required would be purchased outside the UK was identified as an

indication of weakness within the country’s manufacturing base.

The loss of local control created through inward investment was highlighted

the following year in the wake of the Asian financial crisis. First Hyundai announced

that it was reviewing the time-scale for its whole project, and had not yet begun raising

the finance to purchase capital equipment, as opposed to the buildings (which were

already under construction). This would delay the start-up of the project by twelve

months; the second phase was put on indefinite hold. Then in 1998 LG confirmed

speculation that it had postponed the opening of its semiconductor plant by at least

six months. Later that year both LG and Hyundai warned of still further delays from

the rescheduled start-up dates (mid- and late 1999 respectively), as they sought

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

147

The stress on FDI running through this chapter is deliberate, but the absolute

significance of inward investment should not be overplayed; after all, foreign-owned plants

only account for around a quarter of output in the manufacturing sector. On the other hand,

inward investment has been decisive in transforming the shape of a large part of manufacturing

industry in the UK since the mid-1980s, as demonstrated in the case-study of the automotive

industry. Future prospects for manufacturing in the UK rest upon both foreign-owned and

indigenous firms, which face a number of issues in common, including the continued process

of European integration. At the same time, reform in Eastern Europe is posing new challenges

to inward investment agencies in the UK, as a whole new range of competing locations has

opened up. The future structure of the sector in the UK will thus depend in part on the way

in which the issue of policy co-ordination in the pursuit of inward investment is tackled.

Notes

1 Regional statistics were formerly presented on the basis of Standard Statistical Regions (SSRs).

In 1994, new Government Offices for the Regions (GoRs) were established in England which,

with effect from 1997, became the primary basis for the presentation of regional statistics. This

introduced some discontinuities to data series. The main changes were that Cumbria ceased to be

classified as part of the North (which became the North East GoR) and instead was part of a new

North West GoR (which is here combined with the new Merseyside GoR); and the former South

East and East Anglia SSRs were divided into three GoRs. The former SSR of East Anglia became

the Eastern GoR with the addition of Bedfordshire, Essex and Hertfordshire, whilst a separate

London GoR was established.

2 The ratio between male and female average weekly earnings in manufacturing narrowed slightly

but the differential remained substantial during this period at 1.60 in 1991 and 1.54 in 1996.

3 This pattern is even more evident on a longer-term basis. From 1963 to 1987 the South East’s

share of UK employment in foreign-owned manufacturing establishments declined from 51 to

32 per cent, whilst the North’s share increased from 2 to 6 per cent, that of Wales from 4 to 6 per

cent, of Scotland from 8 to 10 per cent, and that of the South West from 1 to 6 per cent. Over that

period the total volume of employment in foreign-owned manufacturing in the UK grew from

540,000 to 620,000 (see Hill and Munday 1992).

4 It was estimated that regional policy had led to unemployment rates in the Assisted Areas being

1 per cent lower than they would otherwise have been in the period from 1980 to 1988. The cost

of RSA was calculated at £500 to £700 per job from 1985 to 1988, with 0.7–1.0 million job-

years created (75–100,000 jobs over thirteen years). Previous evaluations of regional policy had

extrapolated employment trends from the 1950s (when regional policy was much smaller in

scale); the report concluded that there needed to be much better mechanisms for the evaluation

of the effectiveness of policy.

international partners to enable them to bring their projects to completion. Hyundai

subsequently went so far as to halt all construction work on the site. Just weeks

later, Siemens announced the closure of its two-year-old factory in north-east England

(which had received around £40 million in government aid) with the loss of 1,100

jobs, as it sought to find a buyer for the plant. This blow to the regional economy

was further compounded by Fujitsu’s announcement that it too was closing its £0.4

billion semiconductor plant in north-east England, at Newton Aycliffe, with the

loss of 700 jobs, just seven years after it had opened. These events graphically

illustrated the extent to which an economy built on inward investment depended on

processes and decisions well beyond national borders.

DAVID SADLER

148

5 The other major South Korean electronics project in the UK at this time—and the first to be

established—followed Samsung’s decision in 1994 to build a £450 million semiconductor and

consumer electronics plant on Teesside in north-east England, scheduled eventually to create

3,000 jobs there.

References

Bull, P. (1991) The changing geography of manufacturing activity’, in R.Johnston and V.Gardiner

(eds) The Changing Geography of the United Kingdom (2nd edn), London: Routledge.

Hill, S. and Munday, M. (1992) ‘ The UK regional distribution of foreign direct investment: analysis

and determinants’, Regional Studies 26: 535–44.

Stone, I. (1995) Inward Investment in the North: Patterns, Performance and Policy, NERU Research

Paper 14, Newcastle upon Tyne: NERU.

Trade and Industry Committee (1994) Competitiveness of UK Manufacturing Industry, London: House

of Commons Paper 41, session 1993/4.

Trade and Industry Committee (1995) Regional Policy, London: House of Commons Paper 356, session

1994/5.

Trade and Industry Committee (1997) Co-ordination of Inward Investment, London: House of Commons

Paper 355, session 1997/8.

Further reading

On the performance of manufacturing in the UK over a longer-term period until the mid-

1980s, see D. Massey (1988) ‘What’s happening to UK manufacturing?’, J.Allen and

D.Massey (eds) The Economy in Question (London: Sage). On the North-South divide debate

in the late 1980s see R.Martin (1988) ‘The political economy of Britain’s North-South

divide’, in Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 13: 389–413. For a review

of the different explanations for the collapse of manufacturing as seen from the mid-1980s,

see B.Rowthorn (1986) ‘De-industrialisation in Britain’, in R.Martin and B.Rowthorn (eds)

The Geography of De-industrialisation (London: Macmillan). For an account which examines

the roles of labour productivity and management, see T.Nichols (1986) The British Worker

Question: A New Look at Workers and Productivity m Manufacturing (London: Routledge

and Kegan Paul).

On the extent of FDI in the UK, see I.Stone and F.Peck (1996) ‘The foreign-owned

manufacturing sector in UK peripheral regions, 1978–93 : restructuring and comparative

performance’, Regional Studies 30: 55–68. For the debate surrounding the impacts of FDI

in the UK, see M.Munday, J.Morris and B.Wilkinson (1995) ‘Factories or warehouses? A

Welsh perspective on Japanese transplant manufacturing’, Regional Studies 29: 1–17. On

‘performance’ plants see A.Amin and J.Tomaney (1995) ‘The regional development potential

of inward investment in the less favoured regions of the European Community’, in A.Amin

and J.Tomaney (eds) Behind the Myth of European Union: Prospects for Cohesion (London:

Routledge). The broader issue of the interplay between inward investors and receiving regions

is considered in P.Dicken, M.Forsgren and A.Malmberg (1995) ‘The local embeddedness

of transnational corporations’, in A.Amin and N.Thrift (eds) Globalisation, Institutions and

Regional Development in Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

For a discussion of the role of new forms of labour relations as epitomised by the

Nissan plant at Sunderland see chapters 4 and 5 of D.Sadler (1992) The Global Region:

Production, State Policies and Uneven Development (Oxford: Pergamon). For a critical

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

149

view of the significance of new management practices for trade unions, see R.Hudson (1997)

‘The end of mass production and of the mass collective worker? Experimenting with

production and employment’, in R.Lee and J.Wills (eds) Geographies of Economies (London:

Arnold). On the adaptability of inward investors with respect to component suppliers, see

D.Sadler (1994) ‘The geographies of “Just-in-Time”; Japanese investment and the automotive

components industry in Western Europe’, Economic Geography 70: 41–59.

On the broader debates concerning changing forms of production organisation, see

M.Storper (1995) ‘The resurgence of regional economies, ten years later: the region as a

nexus of untraded interdependencies’, European Urban and Regional Studies 2: 191–221.

For a selection of papers which address different aspects of regional policy in the 1990s, see

R.Harrison and M.Hart (eds) (1993) Spatial Policy in a Divided Nation (London: Jessica

Kingsley); P.Townroe and R.Martin (eds) (1992) Regional Development in the 1990s: the

British Isles in Transition (London: Jessica Kingsley).

The likely structure of EU regional policies after 1999 is considered in a debate between

R.Hall (1998) ‘Agenda 2000 and European cohesion policies’, European Urban and Regional

Studies 5: 176–83 and S.Fothergill (1998) ‘The premature death of EU regional policy?’,

European Urban and Regional Studies 5: 183–8.

One response to the intensified competition between different locations for inward

investment was a policy of ‘targeting’ certain forms of FDI: see S.Young, N.Hood and

A.Wilson (1994) ‘Targeting as a competitive strategy for European inward investment

agencies’, European Urban and Regional Studies 1: 143–59. Another response was to focus

on developing the capacities of existing foreign-owned firms through ‘after-care’ strategies:

see K.Morgan (1997) ‘The learning region: institutions, innovation and regional renewal’,

Regional Studies 31: 491–503. For a critical assessment of the impact of the LG project in

South Wales, see N.Phelps, J.Levering and K.Morgan (1998) ‘Tying the firm to the region

or tying the region to the firm? Early observations on the case of LG in Wales’, European

Urban and Regional Studies 5: 119–37.

150

Chapter 8

Labour markets

Jamie Peck and Adam Tickell

Introduction

It is difficult to exaggerate the extent to which the UK labour market has been restructured

over the period since the 1970s. Unemployment has risen to unprecedented levels and has

stayed high; income inequalities have widened; female participation rates have increased

significantly, such that women now constitute more than half the waged workforce;

‘contingent employment’ in temporary, part-time and contract jobs has continued to expand;

union membership densities and strike rates have both fallen, especially in the private sector;

manufacturing employment has collapsed and now eight out of every ten workers are

employed in ‘service’ industries, such as retailing, tourism and finance. Perhaps the key

change, however, has been the emergence of ‘flexible’ labour markets which are now

celebrated and promoted by politicians of all stripes. The Conservatives came to power in

1979 determined to attack what they saw as labour market ‘rigidities’ —powerful trade

unions, institutionalised employment practices, ‘passive’ benefits regimes, ‘bureaucratic’

training systems, and low levels of labour mobility. Under the banner of ‘deregulation’,

Conservative governments set about restructuring the institutions and remaking the rules of

the UK labour market, as a barrage of legislative and policy changes in every area from

employment rights to benefit entitlements actively facilitated the shift towards the more

flexible labour markets of the 1990s. Although the election of a Labour government in 1997

saw changes in emphasis, as social partnership and welfare-to-work were established as

new priorities, advocacy of flexible labour markets remains a central element of the New

Labour credo. In most areas of labour market policy, Labour would build upon the

Conservatives’ reforms; they would not reverse them.

These interrelated processes of flexibilisation and deregulation had widely diverging

effects in regional and local labour markets across the UK. Labour market restructuring has

been associated with a range of complex shifts in the geographies of employment change,

LABOUR MARKETS

151

in local labour market governance and in regional economic fortunes. Take, for example,

the two major recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s. These events both accelerated

the pace of economic restructuring and consolidated shifts in the prevailing form of labour

market regulation. The recession of the early 1980s was in many ways a ‘traditional’

recession: a massive shake-out of manufacturing jobs took its toll on the northern and

western regional economies of the UK which had traditionally relied disproportionately

on factory employment, adding to the structural problems of joblessness and poverty in

these regions. The recession of the early 1990s, in contrast, was very much a ‘flexible’

recession: with its origins in the overheating regional economy of the South East in the

late 1980s, this downturn began with the financial and business services sectors in the

South East itself, only later spreading to the traditional unemployment ‘problem areas’ of

the North and West. In the process, long-established patterns of regional inequality in the

UK have been disrupted and distorted, though they have not been fundamentally remade.

Regional differentials in unemployment were wider in the booming economy of the mid-

1980s than at any time since the 1930s depression. For a brief time, the early 1990s

recession brought about a perverse form of regional convergence, as the once-buoyant

regions of the South and East experienced sharp rises in unemployment. But the flexible

recession was also as quick to end as it had been to arrive: the South East and adjacent

regions led the way in the subsequent recovery period, quickly re-establishing their

positions at the core of the UK economy.

This chapter explores the geography of labour market restructuring in the UK in two

ways. First, the dimensions of change are established by looking at some of the more

significant spatial patterns and trends in labour market restructuring during the 1980s and

1990s. Second, we explore some of the ways in which the shifting policy and institutional

environment has variously responded to, and contributed to, these developments, in the

wake of the breakdown of the Keynesian-welfarist orthodoxy of full employment during

the 1970s. The chapter concludes with a brief discussion of emergent patterns of spatial

restructuring in the UK labour market under New Labour.

Geographies of labour market ‘flexibility’

The underlying weakness of the UK labour market since the 1970s is revealed in the fact

that while employment growth has tended to be fitful and short-lived, the problems of

unemployment and poverty have remained stubbornly entrenched. The official

unemployment count remained above 2 million in 1998, even as the national economy

reached the top of the business cycle and the Bank of England raised interest rates to slow

down the economy. Meanwhile, the job growth that occurred over the previous two decades

was both fragile and highly uneven in character. Between 1981 and 1997, total employment

rose by 1.18 million. Yet this national picture conceals wide regional disparities. Some 1.07

million new jobs were located in the three ‘core’ regions of the South East, East Anglia, and

the South West (although London actually lost 237,000 jobs). While London and the South

East accounted for a stable share of national employment—containing just over one-third

of the country’s jobs in both 1981 and 1997—the three adjacent regions have clearly been

beneficiaries of job growth ‘spilling over’ from the South East: East Anglia, the South West

and the East Midlands accounted for 17 per cent of national employment in 1981, yet

almost two-thirds of jobs created in the 1980s and 1990s were located in these regions. In

JAMIE PECK AND ADAM TICKELL

152

contrast, the North West and the North experienced an overall shrinkage in their employment

base during this period.

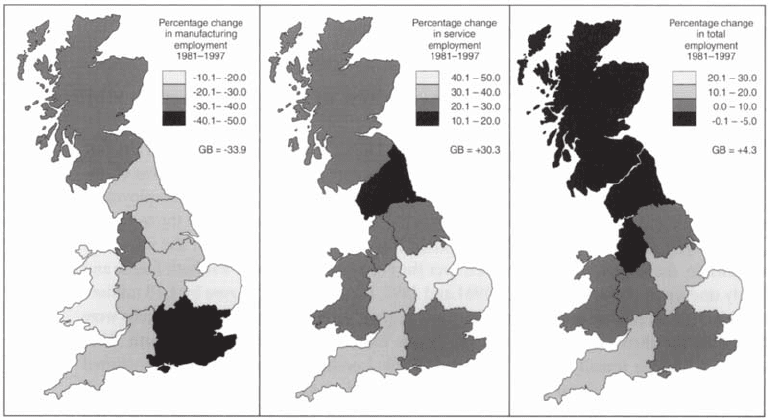

In important respects, these divergent regional economic fortunes can be explained

in terms of the combined effects of (uneven) manufacturing decline and (uneven) service

sector growth (Figure 8.1). Some 2 million manufacturing jobs were shed between 1981

and 1997 (one-third of the nation’s factory employment base), while the service sector

added 4 million new jobs (a growth rate of 30 per cent). Yet the process of labour market

‘conversion’ from manufacturing to services has been highly geographically uneven.

Manufacturing decline (or ‘deindustrialisation’) has primarily disadvantaged the

manufacturing heartlands of the North and West, while service sector growth has

disproportionately benefited the South and East (see Martin and Rowthorn 1986; Marshall

et al. 1988). While the heaviest manufacturing jobs losses occurred in the South East and

the North West, the South East gained 1.2 million new service jobs, more than compensating

for its manufacturing losses, while the North West suffered from a form of ‘non-

compensatory’ restructuring—losing more jobs in factories than it gained in offices and

shops. This said, services now dominate the employment profiles of every region in the

UK—ranging from a low of 69 per cent of total employment in the North to 82 per cent in

the South East—but the nature of service employment remains spatially differentiated.

The South East tends to be home to high-level service jobs, while adjoining regions have

experienced very strong growth in relatively low-productivity, low-wage services (Dunford

1997). The regions of the North and West, meanwhile, are disproportionately dependent

on low-level services, particularly public sector employment.

FIGURE 8.1 Change in employment by sector and region, 1981–97

Sources: Office of National Statistics (ONS); National Online Manpower Information Systems

(NOMIS).

LABOUR MARKETS

153

Clearly, the ‘new service economy’ is a highly differentiated phenomenon, both

sectorally and geographically. A great many service jobs are low-paid, insecure and/or

part-time, but there is also a significant layer of high-level service occupations paying

professional salaries. While the former are quite widely distributed across the UK (in part

reflecting the dispersed demand for personal services), the latter are disproportionately

concentrated in the South East. This is one of the factors behind the persistent patterns in

regional income differentials. For both men and women, in both manual and non-manual

occupations, earnings are higher in the three core southern regions than anywhere else in

the United Kingdom. In 1995/6 men in non-manual jobs in London, for example, had an

average weekly income of £586 (or 127 per cent of the average male non-manual income

in the UK as a whole), whilst their counterparts in the North East had an average income

of £406 (or 88 per cent of the UK average). Furthermore, the gap has widened during the

past two decades for all groups of workers in both absolute and relative terms, but

particularly for women with manual jobs: in 1978/9 no regional average income deviated

from the UK average by more than 5 per cent, by 1995/6 women manual workers in

London earned 125 per cent of the UK average, while their counterparts in Northern

Ireland received 90 per cent of the UK average.

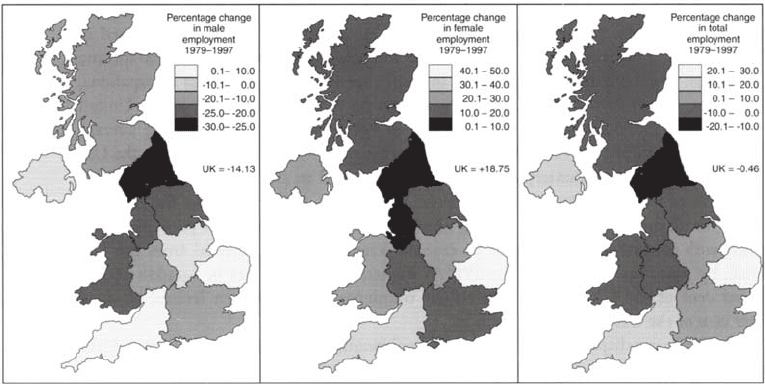

Such income disparities reflect both regional inequality and gendered pay rates. Over

two decades after legislation which abolished differential pay rates for work of ‘equal value’,

women’s wages remain significantly lower than those of men. Although in one sense women

have been the beneficiaries of recent labour market trends (in as far as they tend to be

concentrated in the fastest-growing areas of service employment), in another sense they are

the main ‘losers’ in that these jobs tend to be characterised by low-pay, insecure employment

and limited promotion opportunities. In all regions, women working in both manual and

non-manual jobs have an income of approximately two-thirds that of men in the same

categories—although this represents progress of a sort. In 1978/9 the equivalent figure was

half the male average. Women now represent just over half the national workforce (from 44

per cent in 1981), but tend to be crowded into those segments of the labour market with the

worst employment conditions, such that their experience of ‘flexibility’ is quite different to

that of most men (see McDowell 1991). There is geographical unevenness here too. Dunford’s

(1997) analysis of changing regional employment rates reveals that, during the period 1981–

91, female employment rose by 3.7 per cent while male employment fell by 4.8 per cent.

Increases in male non-employment occurred in every region except ROSE (the rest of the

South East), but were most marked in the North, London, Wales, Yorkshire and Humberside

and the North West. Moreover, female job growth has been weakest in the North, the North

West, Scotland and Yorkshire and Humberside, while it has been strongest in the South

West and East Anglia (Figure 8.2).

Low pay, job insecurity and other exploitative labour conditions are so much more

prevalent in the northern and western regions in large part because these areas have for

many years suffered the effects of structural unemployment and weak economic growth.

Large-scale unemployment tends to act as a drag on pay and conditions because it swells

the ranks of the low-wage labour supply, increases the substitutability of labour and tips

the balance of power in the labour market in favour of employers (Peck 1996).

Consequently, adverse labour market conditions have a tendency to be self-perpetuating,

as regions with a legacy of unemployment and weak labour demand tend to attract mostly

low-paying, contingent jobs which in no sense compensate for the jobs lost. This was the

JAMIE PECK AND ADAM TICKELL

154

situation which confronted many northern and western regions during the 1980s and

1990s. At the start of the early 1990s recession, these regions were still carrying structural

unemployment accumulated during the 1970s. The unemployment rates in the Northern

region and Northern Ireland, for example, were both more than 50 per cent above the

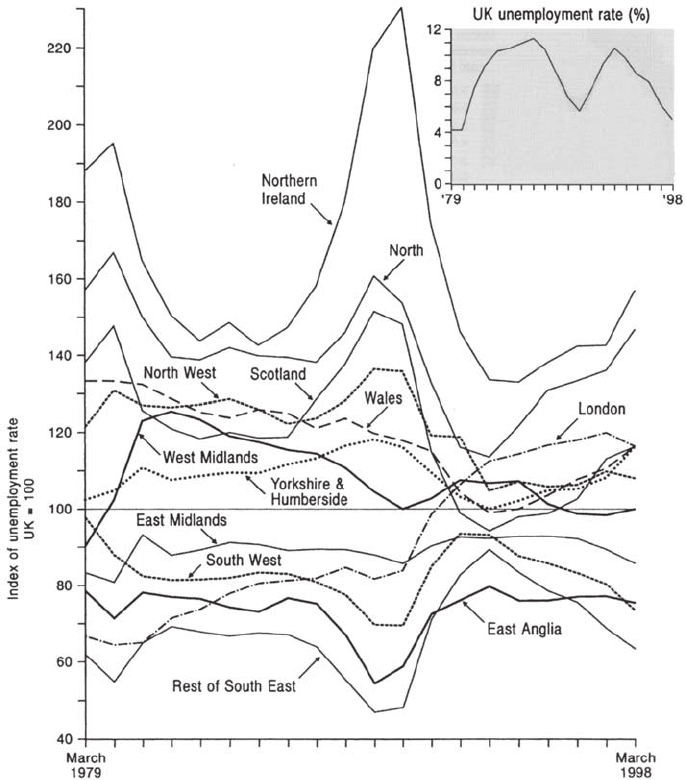

national average in March 1979. As Figure 8.3 shows, this regional bias only deepened

during the 1980s. When national unemployment peaked at over 3 million in 1986, the

jobless rate in ROSE was only two-thirds the UK average, while in the Northern region it

was 40 per cent higher and in Northern Ireland it was 50 per cent higher. So it was the

economically weakest regions which bore the brunt of the job losses during the 1980s.

The early 1980s recession put 2 million additional workers on the dole, 59 per cent of

which were in the northern and western regions. This is not to say that the economic core

in and around the South East was unaffected: unemployment also rose sharply in London

and the East Midlands.

As Figure 8.4 shows, the South East-based recession of the early 1990s disrupted, but

did not overturn, the broad regional pattern in unemployment differentials. In 1998,

unemployment remained highest in Northern Ireland, the North, Scotland, Wales, the North

West and Yorkshire and Humberside. In fact, the pattern of regional unemployment

differentials was almost the same in 1998 as it had been in 1979. While the overall rate of

unemployment was slightly higher in 1998, a trend reflected in most regions, the one

significant change was in London, where the unemployment rate has more than doubled,

from 2.8 per cent in 1979 to 5.7 per cent in 1998. Whereas London ended the 1970s with an

unemployment rate 1.4 percentage points below the national average, following the ravages

of the early 1990s recession its 1998 rate was 0.8 percentage points above the national

average. Given that London also has the highest wage levels of any region, it is worth

recalling Massey’s (1987) comment, made in the context of mounting political-economic

exuberance in the 1980s, that the country’s most economically dynamic region is also its

most socially divided and unequal.

FIGURE 8.2 Change in employment by gender and region, 1981–97

Sources: ONS; NOMIS.

LABOUR MARKETS

155

The recovery period following the early 1990s recession was substantially South East-

centred (Figure 8.5). Nationally, some 1.126 million new jobs were created between 1993

and 1997, but three-quarters of these job gains have been in the core regions of the ‘greater

South East’: the South East and its adjacent regions accounted for 54 per cent of national

employment in 1993 but 74 per cent of subsequent job growth occurred in these regions.

Yet just as the South East experienced a fragile form of growth during the 1980s, predicated

as it was on consumer debt, housing market inflation and the short-term gains of privatisation,

deregulation and middle-class tax cuts (Peck and Tickell 1995; Allen et al. 1998), so also

the recovery appears less than robust in many respects. Indeed, there is a sense in which the

fragile pattern of growth exhibited by the South East has become generalised into a fragile

FIGURE 8.3 Regional unemployment differentials, 1979–98

Sources: ONS consistent unemployment series; NOMIS.