Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

TONY CHAMPION

176

Population distribution

Despite the UK having one of the highest population densities in the world, its population is

very unevenly distributed and only quite a small proportion of its land surface is heavily

settled. The degree of concentration can be measured at a variety of scales. At the broadest

level, exactly half of the UK’s population lives in the four standard regions which comprise

the ‘South’ and make up barely a quarter of national territory. In terms of urban regions

defined in terms of commutersheds around employment centres, just fourteen of the 283

Local Labour Market Areas (LLMAs) contain one-third of Britain’s population, with London

alone accounting for 1 in 7 of all residents and being larger than the next eight largest

LLMAs combined (Champion and Dorling 1994). In terms of physically defined settlements,

in 1991 2,307 ‘urban areas’ (known by the census authorities as ‘localities’ in Scotland)

accounted for almost 90 per cent of Great Britain’s population despite occupying only 6 per

cent of the land area (Denham and White 1998, and see Chapter 10).

This uneven distribution is a legacy of the UK’s pioneering role in the industrial era

and the associated rapid growth of large factory-based settlements at a time when personal

mobility was very restricted. Fifty years of land-use planning policies designed to limit the

outward spread of the largest built-up areas have reinforced this patterning. Even so, recent

decades have seen some important changes in population distribution, in part a reflection of

the changing nature and location of economic activities but also an outcome of changes in

residential preferences and the importance attached to ‘quality of life’. In general, population

has become more concentrated in southern Britain, while at sub-regional and local scales

deconcentration has been the prevailing tendency.

North-South drift

The principal feature of regional population change throughout the twentieth century has

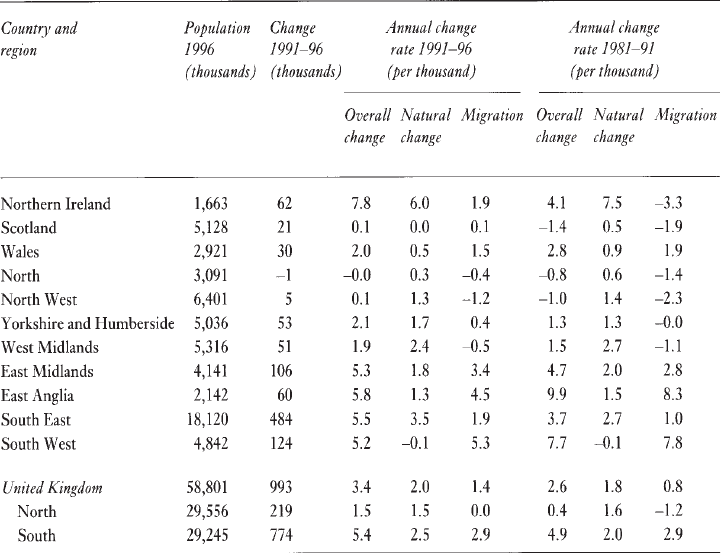

been the drift of population from North to South. As shown in Table 9.3, this tendency

has continued into the 1990s, increasing the degree of population concentration in the

four southernmost regions. The South East, the South West, East Anglia and the East

Midlands combined accounted for over three-quarters of the 1 million national gain in

1991–96. All four regions saw their populations grow at rates of around 5 per 1,000 a

year, well over twice the rate of any northern region apart from Northern Ireland. In

aggregate, the South was growing by 5.4 per cent a year compared to only 1.5 per cent for

the North.

The pace of this southward shift has varied over time, weakening after the first

two decades of the post-war period but accelerating again more recently (Champion

1989). Dorling and Atkins (1995) have neatly summarised this shift in terms of Britain’s

mean centre of population, which moved southwards at a rate of 363 metres a year in

the 1950s, 375 metres in the 1960s, down to 125 metres in the 1970s and back up to 369

metres in the 1980s. In 1991 it was located close to the village of Overseal between

Swadlincote and the Derbyshire/Leicestershire border, some 27 kilometres south of its

position in 1901. The 1990s experience represents a slowdown in this progression, but

not by very much. The overall annual growth rate of the North was 0.4 per 1,000 between

1981 and 1991 and that of the South 4.9, a difference only marginally wider than the

3.9 points of 1991–6. That annual growth rates rose between the 1980s and 1990s in

DEMOGRAPHY

177

most northern regions appears more to do with their paralleling of the shift in the UK’s

growth rate than with redressing the imbalance between the two halves of the country

(Table 9.3).

Table 9.3 shows the separate contributions made to these patterns and trends by natural

change and migration. Natural change has been playing the lesser role, though its significance

increased between the 1980s and the 1990s as the South’s rate rose from 2.0 to 2.5 per

1,000 and that for the rest of the UK fell somewhat, leading to a widening of the South’s

premium from 0.4 to 1.0. Particularly notable in this context is the acceleration in the rate of

natural increase in the South East, which in 1991–6 was responsible for more than half the

UK’s surplus of births over deaths. While Northern Ireland remains distinctive in this respect,

owing to its much higher fertility rate than elsewhere in the UK, this province —along with

most other regions in the northern half of the UK, except Yorkshire and Humberside—has

seen a lowering of the rate of natural change between the two decades, against the UK

trend.

Migration was responsible for the larger proportion of the North-South differential in

the 1990s, though the width of the gap then was narrower than in the previous decade. It can

TABLE 9.3 Population change, by country and region, 1981–96

Source: Data supplied by Office for National Statistics. Crown copyright.

Note: Migration includes adjustments to reconcile population between mid-year estimates

with estimates of natural change and net civilian migration, together with the effects of any

boundary changes. Numbers may not sum because of rounding.

TONY CHAMPION

178

be seen from Table 9.3 that the South’s rate of migratory gain remained unaltered at 2.9 per

1,000, whereas the rate for the rest of the UK rose from -1.2 to a zero net balance. While the

West Midlands, North West and North regions continued to experience net migration loss in

the 1990s, all the northern parts of the UK recorded an upward shift in their migration

balances from the 1980s. Wales showed a slight reduction in its positive migration rate.

Among the four regions of the South, it is notable that, while the South West and East

Anglia registered marked slowdowns from their high migratory growth rates of the 1980s,

the South East and, to a lesser extent, the East Midlands saw their migration gains accelerate

in the first half of the 1990s.

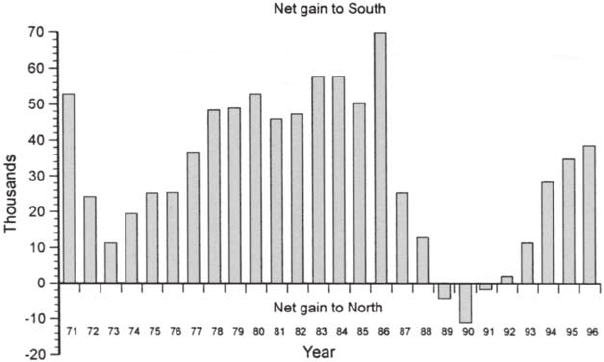

These rather complex changes in regional migration patterns arise from the fact that

at least three different processes have been operating simultaneously and possibly interacting

with each other. In the first place, the late 1980s saw a marked reduction in the drift of

people from North to South within the UK, to the extent that in the three years 1989–91 the

net flow switched in favour of the North (Figure 9.2). Second, around the same time, there

was a cutback in the scale of net exodus from the major cities, notably that from London

into East Anglia and the South West (see the next section). Third, a surge in net immigration

in the late 1980s and early 1990s had a positive impact on the migration balances of most

parts of the UK. However, by far the largest effect was felt within the South East which

absorbed over two-thirds of the UK’s net gains. The first two processes are mainly linked

into changes in the economy, notably the severe recession in the South East towards the end

of the 1980s which reduced its attractiveness as a destination of migrants from more northerly

parts of the UK and brought a marked downturn in housebuilding more generally. It is also

likely, though not as yet clearly proved, that over this period the immigration gains in the

South East reduced the availability of both housing and job opportunities for potential in-

migrants from the rest of the UK.

FIGURE 9.2 Net migration between the South and the rest of the United Kingdom, 1971–96

Source: Calculated from NHSCR data. Crown copyright.

Note: The South comprises the standard regions of South East, South West, East Anglia and

East Midlands.

DEMOGRAPHY

179

Urban-rural shift

Urban decentralisation, in the sense of suburban housebuilding, dates back to the

nineteenth century, but in more recent decades it has been operating on a much broader

geographical canvas. Not only is population moving out from the inner areas of individual

cities but it is also shifting out of the largest urban concentrations to towns and more

rural regions—a process sometimes referred to as ‘counterurbanisation’ and known to

the media as the ‘urban exodus’. As detailed in the second edition of this book (Compton

1991:47), these changes are better studied using specially designed representations of

urban regions and their internal structure as opposed to the standard administrative

areas for which mid-year estimates are available, so the account below focuses on change

between Census years.

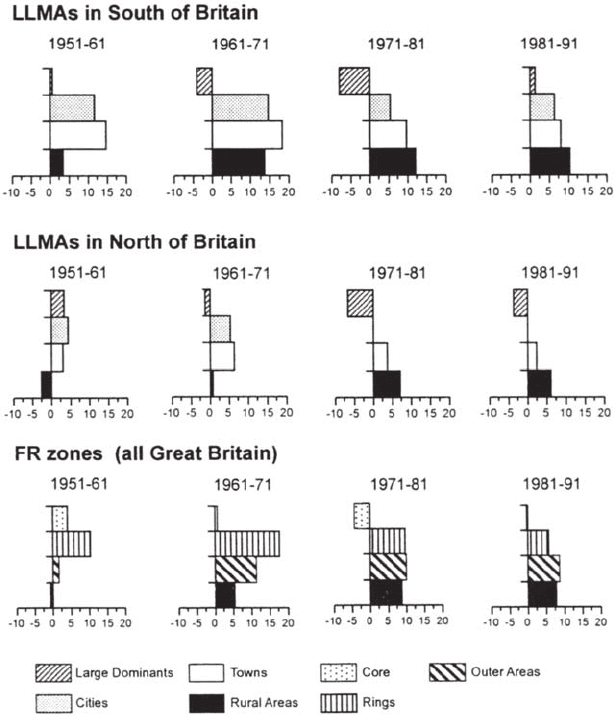

Figure 9.3, based on the Functional Regions framework (Champion and Dorling

1994), clearly illustrates the dual nature of the urban dispersal process, albeit in a highly

summary form. In the latest intercensal period 1981–91, a regular gradient of growth

rate is evident across the four LLMA size groups in both northern and southern halves

of Britain. The ‘large dominants’ at the top of the urban hierarchy register the lowest

growth. At each subsequent level (that is, cities, towns and rural areas) rates in the

South become progressively stronger. The pattern is almost as consistent for the four

types of zone within the Functional Regions, with their main built-up areas (cores)

losing out to their primary commuting areas (rings), and especially to the outer and

rural areas beyond. More detailed analyses (Champion and Dorling 1994) show that

these two dimensions of deconcentration have been occurring side by side, with the

more localised movement of population out of the cores affecting not only the large

dominants but also the cities and towns, which at the same time are gaining people

from the former. Such is the prevalence of these shifts out of heavily built-up areas and

down the settlement hierarchy that the whole urban dispersal process has been dubbed

the ‘counterurbanisation cascade’.

Even so, the pace of deconcentration has not been uniform over time, with the

1980s patterns just described representing a considerable convergence from those of

the previous decade at both scales. Figure 9.3 shows how the large dominants in both

North and South plunged from modest growth to massive decline between the 1950s

and the 1970s, while the rural areas experienced a strong upward shift in growth

rates, but the trend goes into reverse between the 1970s and the 1980s with a

considerable narrowing of the growth gradient. The latter was principally the result

of the recovery of the large dominants, notably in the South where London exerts a

major influence, and a cutback in the growth of rural areas and towns. At the more

localised scale of zone types a similar pattern is evident, with cores weakening through

to the 1970s and then beginning to recover in the 1980s as the growth of the outer and

rural areas fell back.

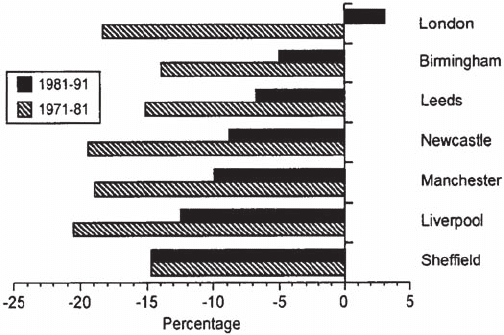

The partial recovery of the largest LLMAs and their main built-up areas in the 1980s

is also reflected at the most detailed spatial scale—that of their inner-city areas. Special

tabulations based on the small-area statistics of the last three Censuses reveal that, for London

and five of the six principal metropolitan cities (Sheffield being the exception), inner areas

saw a marked reduction in their level of population loss between the 1970s and the 1980s.

TONY CHAMPION

180

Most impressively of all, inner London switched from being amongst the greatest losers

into a position of overall gain (Figure 9.4).

In terms of explanation, recent research has focused largely on the slowdown in

deconcentration since the 1970s. Particular attention has been given to the effects of economic

restructuring in the 1980s, notably the exporting to cheap-labour countries of the industries

which led the job decentralisation of the 1970s and the growth of the financial and business

services sectors in the hearts of the largest cities, especially London. The latter, combined

with the ‘baby boomers’ reaching adulthood, is associated with the rise in the ‘yuppy’

phenomenon and the spur to the gentrification of inner-city areas (see Chapter 10). In addition,

the attractiveness of more rural areas fell as increasing pressures led to rising house prices

and traffic congestion, and as the quest for greater efficiencies prompted some withdrawal

FIGURE 9.3 Population change, by Local Labour Market Area types and Functional Region zones,

1951–91, Great Britain

Sources: Calculated from Census, ESRC/JISC data purchase. Crown copyright. See Champion and

Dorling (1994).

DEMOGRAPHY

181

of local shopping, transport and public services from smaller settelements (see Chapter 11).

Even so, in demographic terms, the principal reason for the urban recovery can be found in

the post-1980 surge in net immigration, which has impacted most on the inner areas of

London and certain other cities. Net out-migration from metropolitan England to the rest of

the UK, while fluctuating in the short term, has been averaging 90,000 people a year since

the mid-1970s.

In summary, population redistribution has for decades been dominated by the twin

processes of North-South drift and urban- rural shift, both of which have fluctuated in

pace but look set to continue into the new century. At the same time, it is important to

recognise the diversity of population trends arising from the peculiar circumstances of

individual places and the particular combinations of migration streams that affect them.

Smaller towns can be especially affected by the opening or closure of factories and coal-

mines, while alterations in the migration behaviour of specific groups like students and

retirees can have significant effects even on larger towns and cities. Something of this

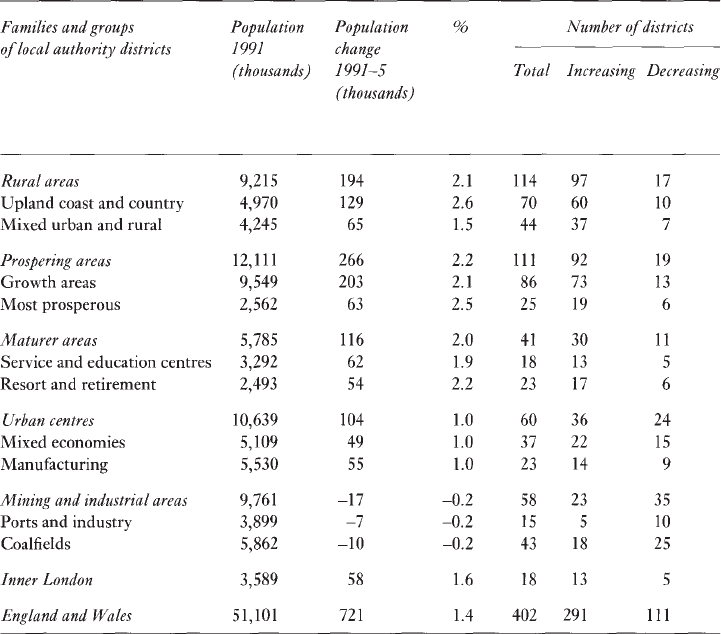

diversity is apparent from Table 9.4, which shows not only the range of growth rates

between different types of local authority districts but also the widespread occurrence of

population losses, even for those types which on average are the most prosperous and

fastest growing.

Population composition

While the UK’s population is growing again in overall size and continuing to redistribute

itself geographically, the most remarkable changes of the past quarter of a century have

been those relating to demographic structure. In particular, the population has been ageing,

it has been getting more diverse in ethnic terms and it has been dividing itself up into

smaller and more varied types of household. These three trends have already had important

implications for many aspects of national life and well-being and they look set to continue

into the future. Moreover, while there is a clear geography of age, ethnicity and household

FIGURE 9.4 Population change for inner areas of London and England’s six Principal

Metropolitan Cities

Source: Calculated from Census, ESRC/JISC data purchase. Crown copyright.

TONY CHAMPION

182

type inherited from earlier decades, most parts of the country have found that the recent

changes in their population profiles are due mainly to their tracking of the national trends.

These and other aspects of socio-demographic restructuring are examined in more detail in

Champion et al. (1996), and some of the consequences for policy at national and local

scales are explored in Champion (1993).

Age structure

The rise in the elderly population has been the most consistent theme of the past

century (Grundy 1996). The proportion of people at or over the current pensionable

age (65 for men, 60 for women) more than tripled from its 1901 level of around 5 per

cent to 18 per cent in 1996. In recent years the most marked change has been in the

numbers of the very elderly, with those 85 and over more than doubling between

TABLE 9.4 Population change by families and groups of local authority districts, England and

Wales, 1991–5

Source: Monitor Population and Health PP1 96/2, 1996, Table C and Table 4 (London: Office for

National Statistics). Data are crown copyright.

Note: Trends after 1995 cannot be studied on this basis because of local government reorganisation.

DEMOGRAPHY

183

1971 and 1996 (up by 120 per cent) and those aged 75–84 increasing by 45 per cent.

This growth derives primarily from the very large birth cohorts of the first years of

this century, which avoided the carnage of the First World War and then lived through

successive periods of improving survival chances. For some years now, this has been

posing a great challenge in terms of health-care and social support, not least because

of the relatively large proportion who do not have children to support them owing to

the low fertility of the inter-war period. Unfortunately, the continuing increases in

life expectancy appear to be providing extra years of disability rather than of healthy

life (Dunnell 1995).

The overall process of population ageing is also greatly affected by trends in fertility,

with the most notable features currently being the low birth rate and the progress of the

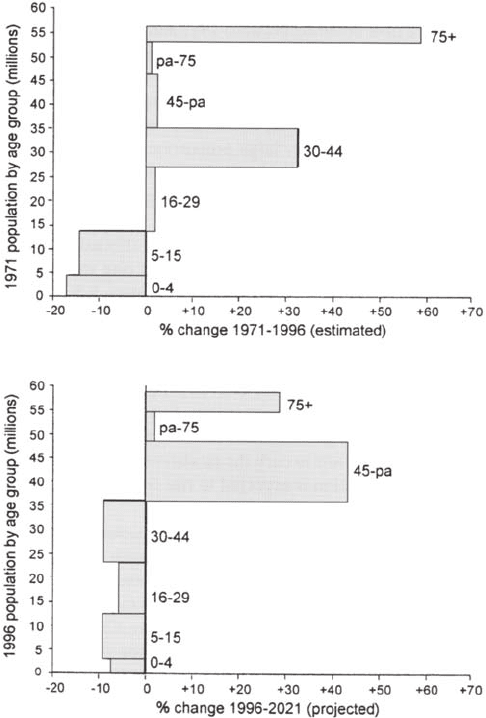

1960s baby boom through the age groups. As shown in Figure 9.5, already in the past

twenty-five years the proportion of under-16-year-olds has fallen by one-sixth and is projected

to reduce further to under 18 per cent by 2021 (see Botting 1996 for further details of the

child population). The passage of the baby boom is reflected in the big increase in 30 to 44-

year-olds between 1971 and 1996 and the even larger projected rise in the proportion of

between 45 and pensionable age over the next twenty-five years. Note, however, that the

latter is inflated by the effects of the government’s decision to raise the official pensionable

age for women from 60 to 65 in its effort to curb the escalation of the pensions bill thereafter.

Overall, the mean age of the population is expected to rise from 38.4 to 41.9 years between

1996 and 2021.

At the same time, there is a marked geography of age structure that means that

certain parts of the UK have already been wrestling for some time with these

challenges. Seaside resorts, spa towns and rural areas have for decades been

characterised by older than average age structures, produced by a combination of

retirement in-migration and the exodus of young adults. The extreme districts at the

1991 Census were Christchurch (Dorset) and Rother (East Sussex), both with

pensioners comprising over one-third of their populations. At the other extreme, with

elderly people making up less than one-eighth of their residents, were new and

expanded towns like Tamworth (Staffordshire) and Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire),

which along with the earlier new towns have already had to cope with sizeable

reductions in school rolls and will find their numbers of older people growing very

rapidly over the next two or three decades.

Ethnic minority populations

While Britain has a long history of immigration and emigration, the growth of its non-

white population is essentially a phenomenon of the last fifty years. It began with the

intensive recruitment of West Indians to combat early post-war labour shortages. Initially

measured in terms of numbers born in the New Commonwealth (see Haskey 1997), the

non-white population is estimated to have risen from around 218,000 in 1951 to 541,000

in 1961 and to 1.15 million in 1971. From then on, unfortunately, this measure has become

increasingly inaccurate, as more children were born to immigrants in the UK and as the

numbers of non-white arrivals from other foreign countries mounted (see p. 175). In

1991, however, for the first time a question on ethnicity was asked in the Census of Great

Britain (but not in Northern Ireland), eliciting a figure of 3.01 million for the non-white

TONY CHAMPION

184

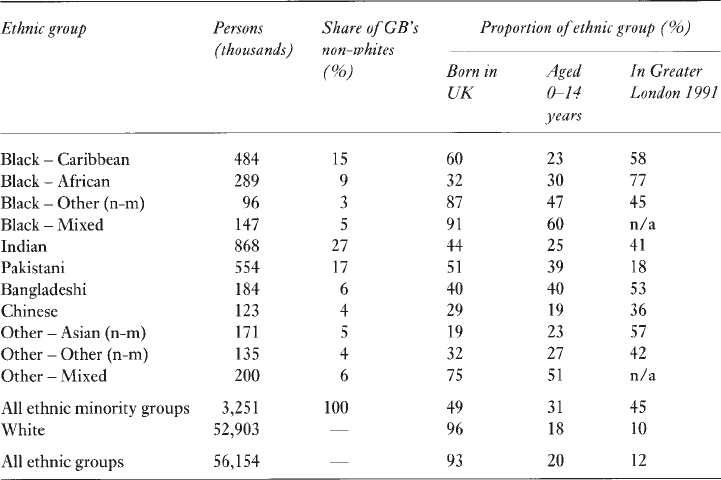

population. The latest estimate, derived from the Labour Force Surveys of 1995/6, is 3.25

million, or 5.8 per cent of Britain’s total population. Of these, almost exactly half (49 per

cent) were UK-born and almost one-third (31 per cent) were aged under 15, a far higher

share than the rest of the population’s 18 per cent. Perhaps most impressively, over the

period 1971–96 the non-white population contributed almost three-quarters of the UK’s

population growth.

At the same time, the non-white population, far from being a homogeneous entity,

is extremely varied in its ethnic background, geographical origins and characteristics,

as shown in Table 9.5. The Black-Caribbean group makes up 15 per cent of Britain’s

non-white population and, being in the vanguard of the post-war surge of immigration,

FIGURE 9.5 Population change by age group, 1971–2021, United Kingdom

Source: Calculated from Annual Abstract of Statistics 134, Table 2.3 (London: The Stationery Office,

1998).

Note: ‘pa’ refers to pensionable age, which in 1971 and 1996 is 65 for men and 60 for women but in

2021 is 65 for both sexes, see text

DEMOGRAPHY

185

contains the highest proportion born in the UK (apart from the mixed-race groups)

and has one of the smallest proportions of children. By contrast, Bangladeshis, as

would be expected of the most recent arrivals among the large national groups, have

a relatively low proportion born in the UK and a youthful age structure. Indians and

Pakistanis form the two largest national groups and have a similar timing of arrival in

the UK, but they differ in terms of their age structure, with Indians having fewer

children.

The ethnic minority groups vary greatly in their geographical distribution, too.

According to the 1991 Census, 45 per cent of all non-whites in Great Britain live in

London, but the proportion ranges from over three-quarters for Black-Africans to under

one-fifth for Pakistanis (Table 9.5). At the district level, there are some notable

concentrations of individual groups. For example, Black groups make up 22 per cent of

Hackney’s population, Indians 22 per cent of Leicester’s, Bangladeshis 23 per cent of

Tower Hamlet’s and Pakistanis 10 per cent of Bradford’s (Champion et al. 1996).

Nevertheless, apart from the Chinese, who are much more evenly distributed around the

country, the New Commonwealth and Pakistani ethnic minority groups have in common

a highly urban lifestyle, living mainly in the inner parts of the larger cities. Moreover,

though they are showing some signs of moving into more suburban areas, their existing

patterns of concentration are being reinforced by natural increase and new arrivals from

overseas (see Chapter 10).

TABLE 9.5 The population of Great Britain 1995/6, by ethnic group

Source: Haskey (1997) Tables 2b, 4, 5 and 8a, calculated from 1995/6 Labour Force Surveys and 1991

Census. Crown copyright.

Notes: n-m = non-mixed; n/a = not applicable, as the 1991 Census did not distinguish Mixed separately