Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DAVID HERBERT

196

Owner-occupancy rates among skilled manual workers changed from 52 per cent in 1981

to 76 per cent in 1996, and among unskilled manual workers from 27 per cent to 43 per

cent. The policies of council house sales and an emphasis upon housing improvement rather

than renewal have underpinned these trends. The private rented sector showed the greatest

decline over the longer period with a fall from 61 per cent in England and Wales in 1947 to

15 per cent in 1970. The advent of housing associations added a dimension to the private

rented sector, but in 1996 the share was still only of the order of 14 per cent. Private landlords

remain important in central parts of major cities, especially London, and the development

of controls to give a wider protected housing market has been a feature. One estimate

suggested that over 90 per cent of British urban housing enjoyed a significant measure of

protection.

The housing market is often cited as a significant factor in understanding the ongoing

process of urban change. As already mentioned, negative equity became a feature during

the early 1990s and marked, if not the end, at least a set-back to the long process of rising

value of residential property. Up to the 1960s, land value was a key consideration with an

index change from 100 in 1939 to 1615 in 1963. After 1974, there was far more stability in

the value of land. Regional variations in property values were marked, with least signs of

improvement and investment in the older industrial cities. Inner-city dereliction signified

the lack of confidence in the urban housing market. By 1994, the United Kingdom had the

lowest annual number of housebuilding completions in the European Union, apart from

Sweden and Denmark, with about 150,000 new dwellings. This compared with over 350,000

per year in the 1960s and 250,000 in the 1970s. Specialised new build for the elderly, the

disabled and the chronically sick formed 38.8 per cent of all new completions in 1981 and

43.5 per cent in 1991, falling back to 27 per cent in 1995. The major shift was the diminished

role of the public sector. In 1981 local authorities built 14,375 new units for these three

groups, but only 2,312 in 1991 and 219 in 1995; between the same dates the private sector

contributions changed from 162 to 1,994 to 445 and Housing Associations from 2,425 to

2,660 to 1,948. In this critical area of housing provision for groups at risk the changing

responsibility from public to private sectors is very clear.

During the 1980s there was an ‘access crisis’ in urban housing with growing numbers

of people qualifying for help under the Homeless Persons legislation. Since 1990, the

DETR has committed over £180 million to the Rough Sleepers Initiative and has built

3,300 new accommodation units for the homeless in London alone. Estimates of the

numbers of homeless people are notoriously difficult to form, but the number is growing

and the problem is becoming more acute. The homeless comprise more variety than the

stereotype single male, and although the root causes may be economic and lack of jobs,

they are exacerbated in major cities by housing shortages and an influx of refugees.

Deinstitutionalisation has forced many mentally ill people out onto the streets and alcohol

problems and drug abuse often exacerbate their condition. Homeless people form an

extreme example of the process of social exclusion, being denied access to the most basic

of human needs. The introduction of an enterprise culture and the market ethic in housing,

as in other areas, has made the plight of the ‘losers’ more visible and extreme. There is

also a more telling human dimension, with research now showing that men living rough

are almost forty times more likely to die young than their contemporaries in secure homes

(Hawkes 1998). As in the United States (Wilson 1987), a ‘truly disadvantaged’ class of

urban dwellers has emerged.

TOWNS AND CITIES

197

The central cities

Commercial functions

City-centre development has been an important facet of urban change in Britain. Initially

stimulated by the legacy of war damage, it has transformed city centres. The continuing

viability of city-centre retailing has led to a sustained flow of investment into shopping

facilities, and between 1965 and 1989 8.9 million square metres of retail floor-space had

been provided in 604 city centres of over 4,650 square metres (the Department of

Environment inspects all developments above this threshold). Between 1984 and 1994, 95

per cent of new retail space had been developed in existing city centres.

Allied with new shopping developments have been positive moves towards traffic

control and management and in-town shopping-centre projects, such as Nottingham’s Victoria

Centre and Broadmarsh and Newcastle upon Tyne’s Eldon Square, which have been designed

to add to or upgrade more traditional retail provision. The perceptible shift to policies with

a stronger commitment to public transport and more constraints on the use of private cars

has been matched by the appointment of some eighty-nine city-centre managers. Funding

remains an issue as the state looks for sponsorship from partners such as Chambers of Trade

and Commerce (representing local retail businesses) and commercial interest groups such

as property investors and developers (which have considerable political influence). Zoning

laws control out-of-town development and it is often argued that there is no other country in

the world which exercises such stringent planning controls over the retail system, particularly

by resisting the market pressures for a greater amount of decentralisation.

Given this support, large department stores continue to invest in the central city and

their presence is essential for the success of in-town schemes. Local authorities have also

improved central-city environments by landscaping and traffic management schemes, and

many office functions that have a high level of direct contact with consumers continue to

locate centrally. For financial and commercial offices, face-to-face contact, especially for

higher-level management, remains important. London, with its large share of the headquarter

offices of the largest UK companies, is dominant and its employment in producer services

increased from 13 per cent in 1971 to 23 per cent in 1989. Large-scale office developments,

especially in London, have been part of the cycles of property speculation and rising land

values that have brought employment and new consumers to the central city.

British inner-city policies have tended to understate the job-creation potential of

retailing despite its labour-intensive nature. The long-term decentralisation of jobs and people

has clearly affected retailing and an intra-urban hierarchy has emerged. In the interwar

years a specialised central-city shopping area extended outwards along main traffic arteries,

with local clusters and individual shops in the surrounding residential areas. With time a

more clear-cut set of shopping areas developed, classified as:

¿ a central area serving a population of at least 150,000;

¿ regional shopping centres which have developed from the smaller central areas in

conurbations;

¿ district centres serving local catchments of around 30,000;

¿ neighbourhood centres selling convenience goods in catchments of 10,000;

¿ local or sub-centres with small clusters of stores serving 500 to 5,000 people.

DAVID HERBERT

198

Much of this framework already existed but was consolidated in the 1950s when

planned shopping centres were added to several levels of the hierarchy. It has been estimated

that in larger cities (over 250,000) 36.8 per cent of retail provision is found outside the

central area; this proportion is inversely related to city size and is 55.3 per cent for cities in

the 40,000 to 49,000 range.

Retail trade has experienced considerable structural change since 1945. There have

been upheavals in the methods and organisation of retailing, a blurring of the retailing/

wholesaling distinction, escalation of multiples, an increase in store size, and greater bulk

buying by consumers. These changes adversely affected small stores and between 1950 and

1966 the number of general stores fell by 56.2 per cent and of grocery retailers by 16.3 per

cent. In part this trend was related to out-migration and the subsequent decline of the ‘corner-

shops’, but it can also be tied to economies of scale and the changing organisation of retailing.

Already by the early 1970s, four organisations together operated nearly 4,500 grocery shops

and accounted for nearly 22 per cent of sales. There is some evidence for a renewed role for

small convenience stores in suburban locations. Large-scale retail organisations have sought

to develop large out-of-town sites, although in the late 1970s only Brent Cross in suburban

north London could be described as ‘out-of-town’.

By the late 1980s, three ‘waves’ of retail decentralisation had been recognised. The

first wave involved the emergence of superstores and hypermarkets during the period 1964

to 1975. A second wave between 1975 and 1985 was composed of retail warehouses, retail

warehouse parks and retail parks; the Enterprise Zones at Swansea and Dudley were typical

of this type of development. The initial sales emphasis was on DIY products, furniture,

carpets and electrical goods but expanded to include clothing, footwear, toys and car

accessories. The third wave dates from 1984 and the proposal by Marks and Spencer to

open out-of-town stores. This type of decentralisation affected the outlets for quality goods

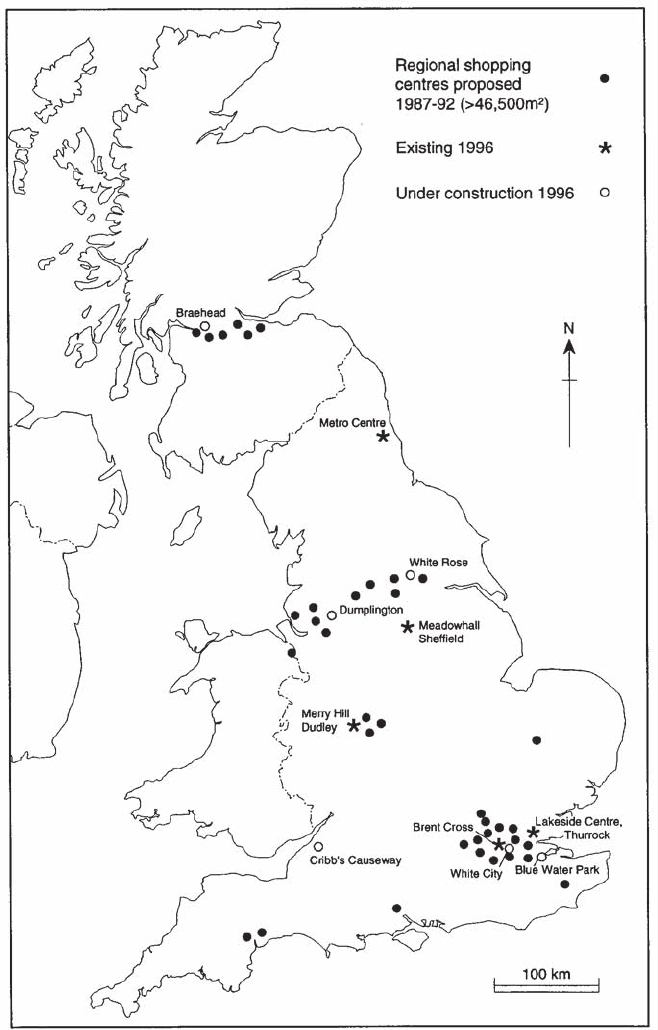

and involved firms such as Habitat, Laura Ashley and World of Leather. Gateshead’s Metro

Centre, opened in an Enterprise Zone in 1986, was the first major example of an integrated

regional shopping and leisure complex. Following Metro Centre with its 136,430 square

metres of floor space, were Merry Hill, Dudley (143,000 square metres), Meadowhall,

Sheffield (116,250 square metres) and the Lakeside Centre at Thurrock (116,250 square

metres), with other planned developments in London, Leeds, Manchester and Glasgow

(Figure 10.3). The idea of a fourth wave in the 1990s focuses on the conflation of retailing

with leisure tourism, with the emergence of outlet malls or shopping villages, such as the

Clarks’ Village at Street in Somerset, the shopping villages at Bicester, Oxford and at

Swindon. Other additions are the informal car-boot sales, new convenience chains, and the

emergence of tele-shopping which may have wider implications for the geography of

retailing. There is now much greater diversity in the provision of retail sales and consumer

choices are changing accordingly.

Objections to out-of-town centres stemmed from fears of their impact on city-centre

trade but the earlier hypermarkets affected smaller branches of multiples rather than

independent corner stores and many retailing firms retained city-centre stores. There is

some force to the concept of the disadvantaged consumer but empirical evidence is equivocal.

Mobility is unevenly available but there has been an expansion of convenience stores, discount

stores and shopping transport, to offset the effects of out-of-town centres.

Overall, retail provision has responded to the two basic needs of redeveloping outworn

parts of the central city and adding new facilities to rapidly growing suburbs. Both of these

TOWNS AND CITIES

199

FIGURE 10.3 Regional shopping centres in the United Kingdom, 1996

Source: After Herbert and Thomas (1997).

DAVID HERBERT

200

have been paralleled by changes in the organisation of retailing, shifts in consumer behaviour

and a fairly consistent planning attitude towards decentralisation. The protected central city

remains a strong and viable location for commercial functions, but there still remains a

need for a comprehensive planning strategy for retail development in and around the city

which reconciles the role of the centre with the continuing pressures for commercial

decentralisation. During the 1990s there are signs that city centres are being adversely

affected.

Jobs and the inner city

The industrial and manufacturing base of the inner cities virtually collapsed in the

second half of the twentieth century with devastating effects on the resident population.

Between 1951 and 1981, inner areas of the conurbations lost 45 per cent of their

employment; over a million manufacturing jobs were lost in the same period; Hall (1985)

cited a figure of 2 million lost factory jobs between 1971 and 1981 in the UK alone.

London, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham all suffered serious losses mainly through

factory closures and the disappearance of traditional employers. The resident populations

were deskilled, and for the new kinds of jobs entering the inner city and London in

particular the demands were for professional skills and IT in keeping with the new

wave of producer services and finance. A continuing expansion of retail trade, office

employment and other services ensured a high demand for women’s employment but

these did little for unemployed industrial or dock workers. Again, there was an impact

on lower-skilled white-collar jobs as banks, for example, displaced their traditional

counter staff and tellers in an age of automated transactions. Commuting flows increased

in importance and resident inner-city populations, apart from those in the new gentrified

areas, had little stake in the restructured employment market. In 1996, inner areas of

cities such as London and Glasgow continued to have unemployment rates of around

15 per cent, which were well above those of surrounding areas. Green (1996) showed

that during the 1980s inner London and parts of other metropolitan areas emerged as

the main losers from the processes of social and economic change. Yet there was evidence

that employment was expanding during the 1990s in places where contraction had

dominated over the past thirty years. Cities with business and electronic networks placed

to act as centres of skill and knowledge could offer milieux favourable to innovation

and change. Large areas of derelict land and pools of labour might be sources of

opportunities rather than of despair (McLennan 1998). The optimism is real but has to

be tempered by the continuing low employment opportunities for black youth and less-

qualified sections of society.

Quality of life

Quality of life, mirrored in indicators such as lack of jobs, substandard housing, educational

disadvantage, crime, vandalism, drugs, and deprivation, has always been a concern for

the inner city. There are pockets of deprivation, and generalisations should not obscure

the considerable diversity which exists. It will be shown that the problem estates in the

outer urban rings can be at least as great a problem as the older parts of the central city.

Matthews (1991) estimated that with 7 per cent of the total population, British inner

TOWNS AND CITIES

201

cities contained 14 per cent of the unskilled workers, twice the average number of

single-parent families, three times the national rate of long-termed unemployed, ten

times those below the ‘poverty’ line, and most of the schools classed as exceptionally

difficult. Although many individual households do not suffer these specific

disadvantages, they are still afflicted by deteriorating environments, vandalism, petty

crime and traffic congestion.

Inner cities also tend to have disproportionate vulnerability to hazards in the urban

environment. The 1992 Earth Summit agreed a policy titled ‘Agenda 21’ aimed at the

improvement of urban environments. This has proved most difficult to implement in the

inner cities where the key challenges of controlling infectious or parasitic disease, reducing

chemical and physical hazards, achieving high-quality environments, minimising transfers

of environment costs, and progressing towards sustainable consumption (Satterthwaite 1997)

can all be easily identified. As Gibbs (1997) noted, cities are the key economic units,

producing 60 per cent of global GNP—and there are inevitable environmental impacts.

Clean production and consumption needs to be accompanied by greater equity and democratic

involvement. There are many working examples. Leeds and Southampton have environmental

strategies; Cardiff, Manchester and Kirklees have environmental programmes set by planning

or environment departments.

Problem residential areas

For much of the nineteenth century, poverty areas were recognisable parts of the British

inner city. They were characterised by high levels of substandard housing and many

indicators of deprivation. The early waves of urban renewal and slum clearance schemes

had a major impact on these areas during the early twentieth century and many thousands

of households were transferred to social housing outside the traditional inner-city terraced

areas. It became clear during the 1970s and 1980s that the problems of the inner city

remained and were once again becoming acute. The pockets of deprivation became highly

visible, with outbreaks of rioting and social disorder, often with racial connotations.

Innercity areas had become repositories of people such as the unskilled, some ethnic

minorities, the elderly and the disadvantaged. Unemployment was high, housing conditions

were often poor, and tensions were high. Social indicators consistently showed wide

disparities between inner-city areas and suburbs, and Green (1996) confirmed the

persistence of these disparities and the poverty areas that still typified the inner city. Such

areas in particular have been adversely affected by the collapse of urban funding and the

withdrawal of inner-city strategies in the 1990s.

Such problem residential areas, however, are not restricted to the inner city. The

problem estate, variously referred to as the difficult-to-let or the sink estate, has become

a feature of public sector housing. Often the products of past policies of ‘dumping’ problem

families in the least-sought-after housing, these estates are typified by high levels of crime,

vandalism, drugs and forms of social disorder. Estates may go through community careers,

with the worst problems evident when demographic cycles endow them with higher

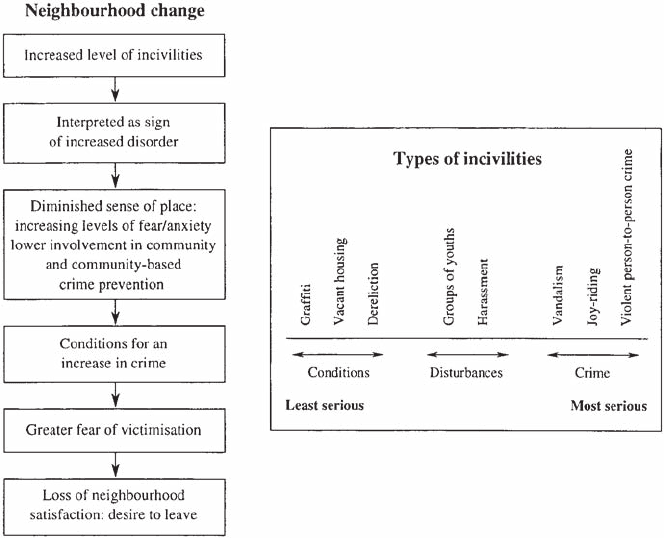

numbers of young people. Studies of incivilities, or signs of disorder in the urban

environment, often pick out estates of this kind at the earlier stages of a downward spiral

(Figure 10.4). Such estates have been described as disgraceful and degrading, adding

poor states of repair and lack of amenities to the high-unemployment and accompanying

DAVID HERBERT

202

social problems. At Meadowell on Tyneside, Barke and Turnbull (1992) documented a

high unemployment estate where a drug culture, endemic crime and a sense of hopelessness

prevailed. The worst estates become characterised by high vacancy rates, and the City of

Swansea in 1998 was reputedly seeking to allocate unlet properties to refugees in an

attempt to generate income from government subsidies. Low demand for housing on a

specific estate is often the starting point for a cycle that leads to pockets of extreme

deprivation (Hall 1997). Hall identified six reasons for the deepening problems of the

worst estates. First, right-to-buy legislation had removed better housing to the private

sector; second, allocations of decreasing stock were made almost exclusively to

marginalised groups such as the homeless and single-parent families; third, gentrification

was displacing poorer tenants to edge estates; fourth, high rents without subsidies were

excluding the working poor; fifth, cut-backs in state spending reduced maintenance; and

sixth, the gap between council tenants and jobs was widening. One of the problems for

the people on problem estates is their relative remoteness from jobs, opportunities and

housing managers.

Gentrification and the return to the central city

The process of gentrification involves the upgrading of specific inner-city districts to

attract higher-income renters or owners. Such districts are often those with Georgian or

Edwardian terraces, most commonly three-storey, capable of modernisation and

FIGURE 10.4 Incivilities and neighbourhood change

TOWNS AND CITIES

203

rehabilitation. Places such as parts of Islington in London have experienced a

considerable transformation as a result of this process. Housing improvement grant

legislation during the late 1960s and 1970s enabled gentrification. One intention was to

improve conditions for sitting tenants, but speculative owners, developers and the housing

market saw the potential to change the whole character and marketability of these areas.

Large numbers of dwellings were improved and sold at much inflated prices and this

had the effect of displacing former low-income tenants. These negative impacts of

gentrification involve displacement, loss of traditional communities, and overcrowding

elsewhere in the city. Positive impacts revolve around the physical and social

revitalisation of older areas at little public cost, new demands for goods and services

and positive spillovers.

The return of investment to the central city gathered impetus in the 1980s with

major redevelopments, funded by a mix of public and private funds, which transformed

old, derelict docklands in many cities into attractive and expensive residential areas.

This maritime quarter boom fuelled an inflow of investment, with the construction of

many new residential properties in imaginative mixes of dwelling types. The

transformation of London’s Docklands has had far-reaching effects linked both with

the expansion of producer services and the attractions of central water-fronted sites.

The Isle of Dogs was designated as an Enterprise Zone in 1982 and land values rose

from £100,000 to £7 million a hectare in five years. The Docklands Light Railway

linked Canary Wharf to the City and this single site could offer direct employment to

40,000 people. There were caveats to this story of growth. First, the new ‘yuppie’

communities were being constructed in close proximity to the residual docklands

communities and presented huge disparities in wealth and quality of life. There were

inevitably social conflict problems. Second, the investment into Docklands was overdone

and a recession was evident in the early 1990s, leading to a loss of confidence and

falling values of property. Some of the major property investors were badly affected

and recovery has been slow.

Urban conservation has been a feature of urban planning in Britain since the

formalisation of the listed building procedures, covering buildings of architectural or historic

interest, in the Town and Country Planning Acts of 1944 and 1947. The conservation area

concept arose most clearly from a court case involving two terraced houses in St James’s

Square, London in 1964. Conservation areas are subjective judgements, but the criteria

include special architectural and/or historical interest and buildings with a character or

appearance worth enhancing or preserving. With the growth of heritage tourism in its various

forms (Herbert 1995), historic cities such as Chester and Bath have become significant

attractions for visitors. Many of the major tourist attractions, including truly historic sites

such as the Tower of London and Edinburgh’s Holyrood Palace, and more recent

constructions such as the Jorvik Centre at York, are located in cities. Many older cities,

faced with a loss of traditional economic activities, have turned to tourism as a panacea and

have striven to make use of whatever heritage, medieval or industrial, old or reconstructed,

that they might possess. For the really historic cities there are pressures from weight of

numbers. There is a ‘local fatigue’ (Strange 1997) arising from numbers of visitors, demands

on local infrastructures and conflicts with resident populations. Such pressures can threaten

the very qualities that make these places attractive and new regulatory mechanisms may be

needed.

DAVID HERBERT

204

Immigrants and ethnic areas

Although the return to the central city of higher-income groups is not an insignificant trend,

the role of the inner city as a destination for immigrants and expanding ethnic minority

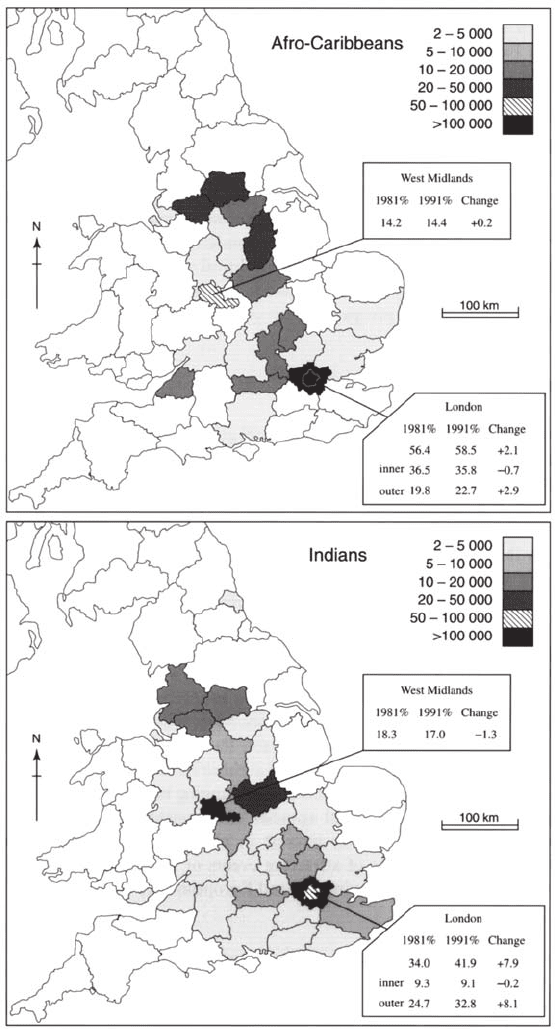

communities has far more telling effects on urban demography. None of the major ethnic

minority groups, Afro-Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi, had less than two-

thirds of their populations in the conurbations in 1991 (Figure 10.5). All these groups had

shown growth in their conurbation populations over the previous decade, ranging from 1.6

per cent for Afro-Caribbean to 5.7 per cent for Bangladeshis. The Greater London and West

Midlands conurbations tend to dominate with, for example, almost two-thirds of all the

Afro-Caribbean and Bangladeshis resident in one or the other. The lesson from the 1991

Census was one of little change; ethnic areas in British cities have emerged and are

consolidating, but conditions do not resemble the ghettos typical of many cities in the United

States (Peach 1996; Robinson 1993). There is variety in ethnic housing and there is some

evidence that Afro-Caribbean households were decentralising from the innermost parts of

London and, to a greater extent than the other groups, had a significant presence in the

public sector of housing. The large majority of South Asians remained rooted to owner-

occupancy, low-cost areas of cities with a limited amount of professional suburbanisation.

Ethnic areas have been features of British cities for many years in areas such as

London’s East End and comparable districts in other major port cities. The modern wave of

immigrants from New Commonwealth countries began in the 1950s stimulated by poverty

and lack of opportunities in their own countries and the promise of better jobs and prospects

in the United Kingdom. In 1963/4 legislation to control the flow of migrants stopped the

main movements, but certain categories such as dependants and those with special skills

have continued to arrive. The earliest migrants were Afro-Caribbean, recruited at a time of

labour shortage by London organisations such as the large teaching hospitals, London

Transport and the Hotels and Restaurants Association. Other Caribbean immigration followed

the expanding car plants and engineering works in the London area and the West Midlands.

Indians followed a similar pattern (Robinson 1993), but Pakistanis moved further afield to

towns in the north of England such as Manchester, Oldham, Blackburn, Leeds and Bradford.

There were later Asian concentrations in the East Midlands (such as at Leicester), amplified

by forced migrations out of East Africa.

Estimates put the total size of the UK ethnic minority population at 2.6 million in

1990, forming 4.8 per cent of the total population, with the largest groups being Indian

(827,000), Afro-Caribbean (496,000) and Pakistani (455,000). Annual rates of increase

peaked with 98,000 in 1981, but were around 55,000 by the early 1990s. There is diversity

within the groups, with divisions by islands of origin among the Afro-Caribbeans and sub-

groups such as Sikhs and Gujeratis within the South Asians. Although the ethnic minorities

tend to occupy the same broad types of housing within cities, there is some evidence for

segregation within these sub-groups. The ‘ethclass’ had emerged, with clear social gradations

reflected in housing areas.

The Race Relations Act of 1976 was a key piece of legislation, but there has been

persistent discrimination in employment and housing markets against non-white immigrants.

The whole thrust of public policy since the 1970s has been to improve employment chances,

but always in difficult situations. There are greater numbers of ethnic minorities progressing

further in the educational system, and Asians in particular have proved very successful in

TOWNS AND CITIES

205

FIGURE 10.5 Numerical distribution in 1991 of (a) Afro-Caribbeans, (b) Indians

Source: After Robinson (1994).