Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MALCOLM MOSELEY

226

chains, Post Office Counters, etc., as well as by those in the local authorities who try to

coordinate transport provision and ‘outlet location’ decisions in a variety of strategic and

local planning exercises.

Indeed a new word is entering the lexicon of those who study the changing rural

scene. It is ‘governance’:

The concept of ‘governance’ is broader than that of ‘government’ because it

encapsulates not just the formal agencies of elected local political institutions, but

also central government, a range of non elected organisations of the state at both

central and local levels, as well as institutional and individual actors from outside the

formal political arena, such as voluntary organisations, private businesses and

corporations, the mass media and increasingly, supra national institutions such as the

European Union.

(Ward and McNicholas 1997:1)

The point is twofold. First, only by trying to untangle how all these agencies interrelate can

we really get a handle on how rural Britain is changing. Second, given that the decision-

making arena is so crowded, attempts are increasingly being made to pull them together at

the local or area level into formal or informal partnership arrangements. Two of this chapter’s

three briefcase-studies of Britain’s rural areas—those of the Scottish Western Isles and of

England’s Forest of Dean—demonstrate examples of local partnerships, or, to put it

differently, attempts at ‘governance’.

One other key development in ‘rural decision-making’ warrants mention, touching as

it does all of the issues raised in this chapter—that of increased ‘local community

involvement’. More and more ordinary people living in our small towns and villages are

demanding a say in the decisions that affect them and often have a role in actually delivering

services at the very local level. Equally striking, local and national government is increasingly

encouraging this trend, troublesome though on occasions it might prove to be.

There are various reasons for this official encouragement of community action. First,

better decision-making: rural people are an increasingly sophisticated source of information

and of ideas for addressing local concerns that it would be folly to ignore. Second, if a local

authority policy—relating, for example, to a school reorganisation programme or to the

designation of land for different kinds of development—can be firmly based upon a local

consensus then it is less likely to be ‘ambushed’ when it comes to implementation. Third,

self-help can obviously save money—especially in those smaller or remoter settlements

where public and private sector agencies are increasingly concerned at the costs of service

delivery. And local people are frequently ready to give freely of their time, expertise and

money, not to mention spare seats in their cars and underused space in their buildings if it is

for the good of their immediate local community. Fourth, involving the community can

enhance what is now called ‘capacity building’, meaning the building up of the human

resource, the social networks and the informal institutions of an area which can all bear fruit

in the longer term.

One increasingly popular way of stimulating community involvement is the ‘village

appraisal’ —over 2,000 of which have been carried out in British parishes, villages and

small towns over the past fifteen years. These are social surveys ‘of the people, by the

people, for the people’, with the words ‘by’ and ‘for’ being the crucial ones. Data amassed

RURAL CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT

227

BOX 11.3 Goring and Streatley: a slice of ‘middle England’

Goring and Streatley lie on the Oxfordshire/Berkshire border, astride the River

Thames, ten miles upstream from Reading, forty miles from London, and well

and truly in the relatively prosperous ‘South’. In 1991 a group of volunteers,

helped by the two parish councils and the local amenity association, decided to

carry out a ‘village appraisal’, delivering a long questionnaire to all 1,700

households and achieving a 70 per cent response. The idea was to ‘provide an

accurate picture of the villages as they are now…for information and interest…and

to help villages and organisations interested in the future’.

The attractive 62-page report that emerged, Goring and Streatley: A Portrait,

is one of a thousand or more produced up and down the country in the last decade

and it is the very ‘ordinariness’ of the picture revealed which is of interest. This is

not a former coal-mining area with run-down colliery villages or a collection of

crofting communities on remote islands 600 miles from London (see Boxes and

11.1 and 11.2). It is a slice of middle class, middle aged, south midland, ‘middle

England’ beloved by millions of semi-rural/semi-urban (does it matter which?)

people spread across broad swathes of our country.

Car ownership in the two villages is high. Even in 1991 43 per cent of

households had one car, 33 per cent had two and 9 per cent had three or

more. By the same token, 15 per cent did not have a car at all. And this is

‘commuter land’, with half of those employed travelling daily to Reading or

London and with most of the rest working in a broad swathe of Oxfordshire,

Berkshire and neighbouring counties. Unemployment hardly gets a mention

in the report, but there is concern that strikingly few adults aged 20–40 live

in the two parishes, and thereby few young children. Housing is expensive

and most lower-income families cannot afford to buy in this part of the

Thames valley.

The concerns expressed by a majority of the households surveyed were

far from being narrowly self-interested. Most households are themselves well

housed and car owning, but a need for affordable housing for rent, and for

better public transport, was widely appreciated. High on the list of concerns

were two almost universal bêtes noires of middle-class, semi-rural, outer-

metropolitan England. First, traffic—congestion, road safety, the long mooted

but still awaited bypass. Second, ‘planning’ —the sense of having to be

constantly vigilant lest ‘the planners’ foist on the community ‘unwanted

development’ —in this case a shopping and office development on a vacant

site in the village centre.

And the responses of the people of Goring and Streatley also neatly exemplify

the widely held sentiments of village and small town communities across the country:

an affection for ‘the village atmosphere and environment’ and a concern for very

local environmental nuisances—in this case traffic intrusion and car parking, a few

eyesores and derelict buildings, litter and dog dirt in the park.

MALCOLM MOSELEY

228

at local level on people’s hopes and fears, likes and dislikes, pulled together by volunteer

teams into reports on ‘our village and where it’s going’ and debated in village hall and

parish council meetings, have proved to be a powerful spur to action. Such action may be by

outside agencies who feel empowered or cajoled into re-routing the bus service or part-

funding a play scheme; and/or by local people themselves who feel encouraged to set up

‘good neighbour schemes’ or community shops, say, by the local mandate for action and

the freshly replenished reservoir of community spirit.

The danger, of course, is that ‘do it yourself’ will come to be seen as the

panacea for the ills of our rural communities. Certainly there was a whiff of this in

the Rural White Paper (DoE and MAFF 1995), which set as a key objective

‘encouraging active communities which are keen to take the initiative to improve

their quality of life’. It would be a tragedy if the growth of community involvement

were to become the state’s mandate to abdicate as far as rural Britain is concerned.

Rather, the fortunes of Britain’s rural communities in the twenty-first century may

better lie in the notion of ‘partnership’ and in ever seeking a judicious balance

between the benefits of orchestrating integrated strategies and programmes at area

or regional level on the one hand, and on the other of fostering grass roots initiative

and entrepreneurship. Certainly the old notion of ‘state decides, state provides’

seems gone for ever.

Conclusion

At the end of the twentieth century, rural Britain continues to undergo rapid social and

economic change, driven by forces emanating largely from outside the rural areas themselves.

The next century will see a further erosion in the economic distinctiveness of rural areas,

although socially they may increasingly be home to the more privileged members of our

society who will strive to preserve, indeed to ‘manicure’, the idyllic character of their

environment even if that imposes hardship on their less fortunate neighbours.

Listing a few overarching concepts provides a convenient way of summarising some

of the challenges that lie ahead:

¿ sustainability—managing the inevitable change so that it minimises the erosion of the

inherited ‘capital’ of rural Britain—the word ‘capital’ embracing the natural and human-

made environment as well as traditional culture and social support mechanisms in the

widest sense;

¿ social balance and social justice—ensuring that we do not drift towards a polarised

society in which our countryside, villages and attractive small towns become just a haven

or playground for the middle classes while the cities deteriorate in quality and social

acceptability;

¿ governance, partnership and community involvement—all terms that imply a need to

galvanise the full range of local people and of relevant agencies, from parish councils to

Regional Development Agencies, in resolving these key issues.

RURAL CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT

229

References

Cloke, P., Milbourne, P. and Thomas, C. (1994) Lifestyles in Rural England, Salisbury: Rural

Development Commission.

Department of Environment and Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1995) Rural England, a

Nation Committed to a Living Countryside (‘The Rural White Paper’), CM3016, London: HMSO.

(Note: Parallel documents were produced simultaneously by the Scottish and Welsh Offices.)

Moseley, M.J. (1997) ‘Parish Appraisals as a tool of rural community development: an assessment of

the British Experience’, Planning, Practice and Research 12(3): 197–212.

Rogers, A. (1993) English Rural Communities: an Assessment and Prospect for the 1990s, Salisbury:

Rural Development Commission.

Rural Development Commission (1995) Rural Economic Activity, Salisbury: Rural Development

Commission.

Rural Development Commission (1998) 1997 Survey of Rural Services, Salisbury: Rural Development

Commission.

Ward, N. and McNicholas, K. (1997) Reconfiguring Rural Development in the UK: Objective 5b and

the New Rural Governance, Newcastle upon Tyne: Centre for Rural Economy, University of

Newcastle upon Tyne.

Further reading

LEADER Magazine (LEADER Observatory AEIDL, Chaussee St Pierre 260, B1040,

Brussels). This tri-annual magazine is available free of charge from the Observatory.

Three excellent ongoing series of reports on aspects of rural development in the UK are

worth noting, namely those by:

1 the Scottish National Rural Partnership on ‘Good Practice in Rural Development’ (contact

the Scottish Office);

2 the Centre for Rural Economy, University of Newcastle upon Tyne;

3 the Rural Development Commission, London and Salisbury (now subsumed into the

Countryside Agency).

230

Chapter 12

Life chances and lifestyles

Daniel Dorling and Mary Shaw

Introduction

This chapter considers some of the most simple of life chances in Britain. It shows how

they are affected by social influences on lifestyle at the individual and geographical level.

People’s chances of dying young in the 1990s are used as an indicator of misfortune.

These are compared with their chances in the 1950s and the two geographies are mapped

for different age groups to show the changing regional patterns of mortality. Normally

medical explanations are made for premature mortality, but this chapter focuses solely on

social and behavioural factors as explanations for mortality rates for particular groups of

people in Britain. The chapter begins by illustrating the changing regional geography of

mortality in Britain through a series of maps for different age groups at two points in

time. We then show how geographical inequalities in mortality can be measured. Since

the 1950s, and particularly during the 1980s, geographical inequalities in mortality and

life chances in general have grown in Britain. The factors which may underlie this rise

are then discussed. The chapter then shows the reader how they can estimate their life

expectancy, or, rather, the life expectancy of someone of their age, sex and

characteristics. The categories of factors considered are basic demographics (age and

sex), social class background (father’s social class, own social class, height and

unemployment), geography (country of birth, region of residence, housing tenure),

behavioural factors (smoking, alcohol, diet, exercise, weight and injecting illegal drug

use) and relationships (sexual activity and marital status). The purpose of this exercise is

to show how life chances in contemporary Britain have both social and spatial

dimensions. The geography of society influences the behaviour and opportunities of its

members which, in turn, alters the geography of the outcomes of their actions—in this

case, death.

LIFE CHANCES AND LIFESTYLES

231

The changing geography of death in Britain

There is a geography to premature death in Britain. This geography is largely the mirror

image of the geography of good health. The concept of health is very difficult to define, and

even more difficult to measure. For example, the World Health Organisation (1948) defined

health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the

absence of disease’. Because good health is so difficult to define and measure, geographers

often use the map of premature death—a much more easily definable and measurable

outcome—as a proxy for a map of ill health. In this chapter we shall introduce you to the

geography of good and poor health and how health can be counted and the factors behind

health measured. We shall show you maps of areas of good and poor health for different

groups of the population and describe how and why these maps have changed over the last

fifty years. We shall also explain how the geography of health in Britain has been changing

over recent decades. These patterns and changes will be illustrated by showing you how

you can estimate your own life expectancy.

We start our description of the geography of mortality in Britain by looking at the

differences in people’s chances of dying fifty years ago. Here, for simplicity, we concentrate

on the ten places for males and females which had the highest and lowest mortality rates for

each of six age groups. Males and females are considered separately because different factors

have differing influences on their lives and they often die from different causes of death.

The obvious differences are biological; for example, no men die giving birth to a child or of

ovarian cancer. More importantly men and women, in general, tend to suffer differently as

a result of the social changes which underlie the geography of health. For instance, when

the shipyards and mines were closed it was almost all men who lost their jobs and who were

subsequently more likely to suffer from ill health. Women are, in general, more likely to

suffer from the effects of insecurity of employment which have been shown to be health

damaging, but are less likely to suffer, for example, from accidents in adolescence as they

are brought up to be more careful than boys. We separate the six different age groups described

here for much the same reasons, both biological and social.

Our data are based on the Registrar General’s Decennial Report on Mortality in England

and Wales for 1950–3 and the Scottish General Registrar Office Reports of Mortality for

these same years. The geographical areas we use are the 292 London Boroughs, Metropolitan

Boroughs and Urban and Rural Remainders of Counties used in these reports. We have also

used a Geographical Information System to produce equivalent statistics for mortality in

the period 1990–2 so that changes in the patterns can be evaluated for these same areas.

This was the most recent period which could be compared with the past as we are reliant

upon the 1991 Census to provide the population estimates to calculate mortality rates for

these areas.

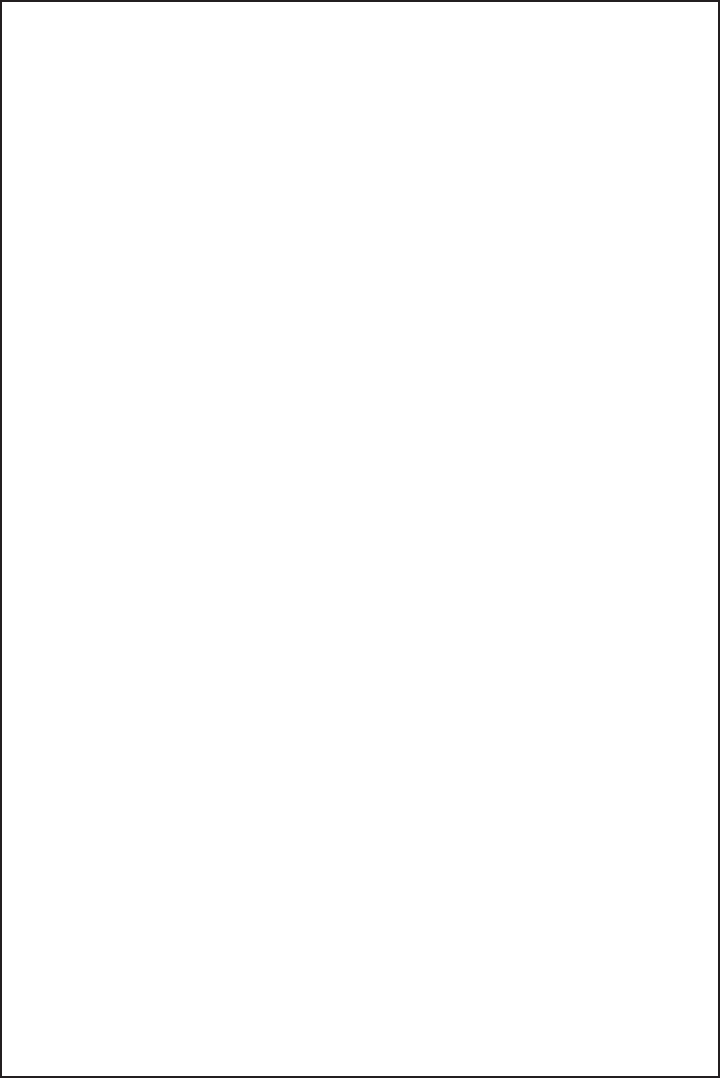

Figure 12.1 shows the geography of infant mortality across Britain between 1950 and

1953 and can be compared with Figure 12.2 which shows the same distribution forty years

later. Figure 12.2 highlights the ten areas with the highest and lowest rates of infant mortality

for both boys and girls. Usually these areas coincide, areas with high rates for boys also

have high rates for girls and in these cases the figure splits the two symbols in half and the

combined symbol is placed over the area being indicated. There was a clear regional divide

in infant mortality in the 1950s with the highest rates found in large cities in the North of

England, Scotland, South Wales and the Potteries while the lowest rates were all south of a

DANIEL DORLING AND MARY SHA

232

line between the Severn and the Wash, with the exception of Edinburgh for infant girls. This

divide reflected the living standards of the parents of infants across Britain at that time, their

levels of nutrition, whether their homes were damp, levels of overcrowding, and so on.

Forty years later, as Figure 12.2 shows, the map has not altered greatly, despite huge

reductions in the national rates of infant mortality and great improvements in general levels

of nutrition, housing conditions and overcrowding. This is because the relative differences

between the standards of living in the North and South have not narrowed. There has been

a concentration of the areas with the highest rates of infant mortality into northern English

cities, and two affluent places in the north (small towns in Cheshire and parts of Rural

Derbyshire) now have some of the lowest rates.

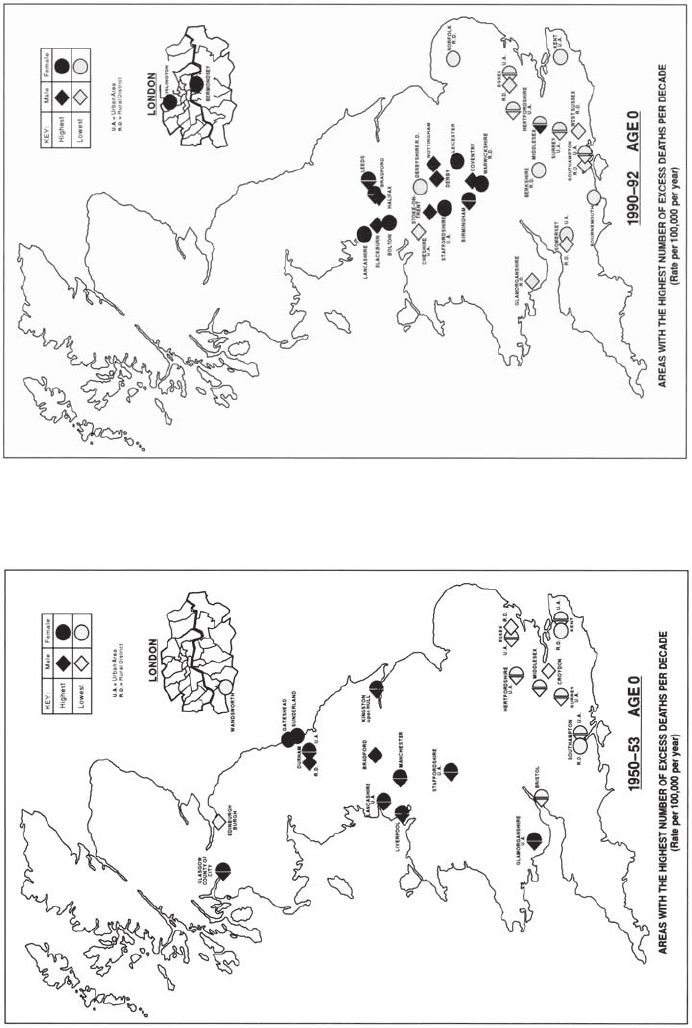

Figure 12.3 shows mortality rates for boys and girls aged 1 to 4 between 1950 and

1953 with Figure 12.4 showing these same rates forty years later. Again the North—South

divide is evident, although slightly less clear cut. Part of the reason for this is that, particularly

in the later period, this is the age group in which mortality is least common and so a few

extra deaths occurring in any one year can alter the overall picture. The congenital conditions

which lead to the majority of infant deaths are no longer so vital for this age group and low

rates can now be seen west of the Penines as well as in the South and in Edinburgh, as

before. However, by 1990–2 rates in two of the poorer London Boroughs come to be within

the top ten areas for boys aged 1 to 4, while in the North rates are generally only low outside

of the larger towns. The relative deterioration of infant health in London will be seen later to

be reflected by a new concentration of ill health for adults in the capital city by 1992.

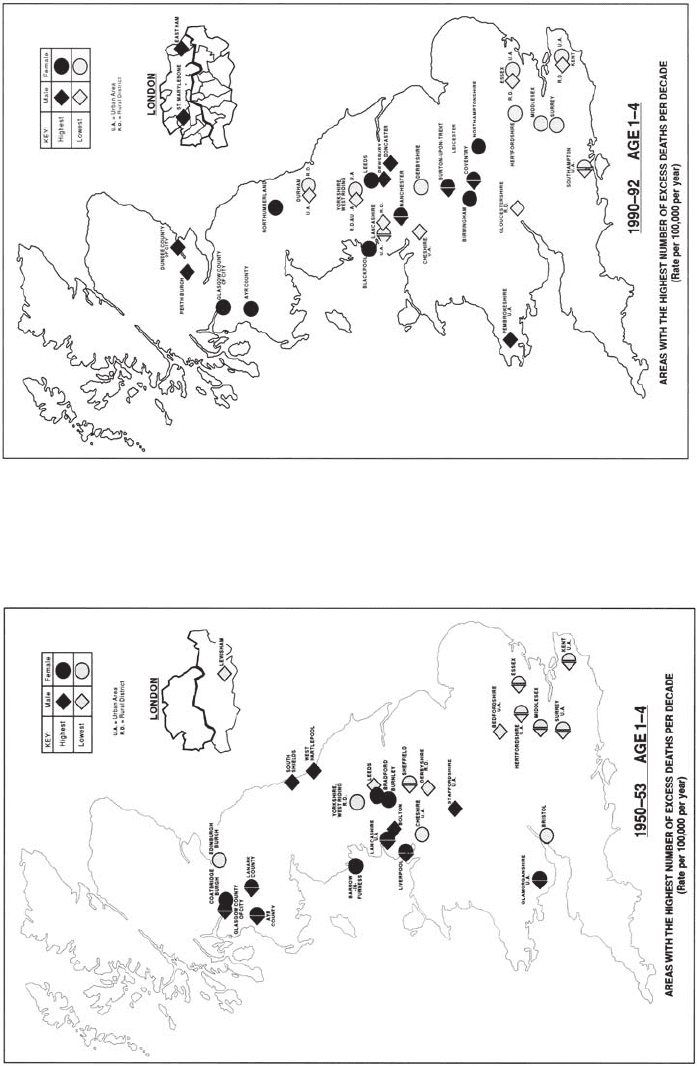

Figures 12.5 and 12.6 show the rates for the next age group of children aged 5 to 14

in 1950–3 and 1990–2. Again the North-South divide is evident, although rates are low in

the 1950s in small towns in Durham, the West Riding, Lancashire and Cheshire. All high

rates are again north of a line between the Severn and the Wash. Fifty years on the pattern is

similar, although rates in the small towns of Wiltshire (principally Swindon) and in the old

London Borough of Deptford are now in the top ten. Accidental death is a major factor for

this age group, often including road traffic accidents. But again this is not a random toll. A

child’s chances of being killed by a car are strongly related to their social advantages and

disadvantages, as we discuss later.

For young adults Figures 12.7 and 12.8 also show an extremely strong North-South

divide for both the 1950s and 1990s. Initially, only in the rural districts of the West Riding

and Lancashire were young adult mortality rates low in the North. Forty years later the

greatest change has been the sudden concentration of areas of high mortality into six London

Boroughs. Of all the age-sex groups we are examining here, men aged 15–44 have seen the

worst improvement in their overall chances in recent years, with their death rates now actually

rising in many areas. This rise has followed the pattern of high unemployment in Britain—

the relatively new concentration of mass unemployment and poverty within London has led

to this geographical concentration.

For older adults aged 45–64 the story is quite different, as Figures 12.9 and 12.10

show. The North-South divide is almost as clear as for infants in the 1950s, with only the

rural districts of the West Riding bucking this trend. However, by the early 1990s this anomaly

has disappeared and the country is clearly divided between northern cities where the old die

young and the generally rural areas of the south where they are more likely to live to healthy

old age. Compare Figures 12.1 and 12.10, infant mortality in the 1950s and older adult

mortality in the early 1990s. Notice any similarities? In general, the children who were least

FIGURE 12.2 Infant mortality rates for males and females, 1990–2

FIGURE 12.1 Infant mortality rates for males and females, 1950–3

FIGURE 12.4 Mortality rates for males and females aged 1–4, 1990–2FIGURE 12.3 Mortality rates for males and females aged 1–4, 1950–3

FIGURE 12.6 Mortality rates for males and females aged 5–14, 1990–2

FIGURE 12.5 Mortality rates for males and females aged 5–14, 1950–3